Abstract

Creation of a colostomy in colorectal (CRC) cancer patients results in a loss of control over bowel evacuation. The only way to re-establish some control is through irrigation, a procedure that involves instilling fluid into the bowel to allow for gas and fecal output. This article reports on irrigation practices of participants in a large, multi-site, multi-investigator study of health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) in long term CRC survivors. Questions about irrigation practices were identified in open-ended questions within a large HR-QOL survey and in focus groups of men and women with high and low HR-QOL. Descriptive data on survivors were combined with content analysis of irrigation knowledge and practices. Patient education and use of irrigation in the United States has decreased over the years, with no clear identification of why this change in practice has occurred. Those respondents who used irrigation had their surgery longer ago, and spent more time in colostomy care than those that did not irrigate. Reasons for the decrease in colostomy irrigation are unreported and present priorities for needed research.

Keywords: Colostomy, colorectal cancer, irrigation, bowel control

In 2012 approximately 40,290 patients will be newly diagnosed with rectal cancer ("American Cancer Society Cancer Facts & Figures," 2012). For some patients, surgery will involve creation of temporary or permanent ostomy, and they will join more than 700,000 people in the United States who have an ostomy ("Colostomy New Patient Guide,") . When the colostomy is located in the sigmoid or descending colon, regulation of fecal output can occur through irrigation, a procedure that involves instilling fluid into the bowel in order to flush out gas and fecal material (Rooney, 2007). When successfully used irrigation can prevent fecal output between irrigations, providing some control over colostomy output. The purpose of this manuscript is to describe participants of a large, multi-site, multi-investigator study of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in long term (>5 years) CRC survivors who answered questions about colostomy irrigation, and explore the reported advantages and disadvantages of this procedure.

Background

A permanent intestinal stoma occurs during surgery for rectal cancer when an anastomosis (re-connection) of the remaining bowel is not an option. Permanent colostomies are most common for low rectal cancers and usually created from the sigmoid or descending colon. The presence of a colostomy has a major impact on the patient’s HRQOL (Altschuler, et al., 2009; Baldwin, et al., 2009; Grant, 1999; R. Krouse, et al., 2007; R. S. Krouse, et al., 2009; McMullen, et al., 2008). A pouch or bag is worn over the colostomy to collect the fecal output. Colostomy care usually involves emptying the pouch daily, multiple times a day, or every other day. The skin surrounding the stoma is cleaned and the wafer is typically changed every 3-7 days. Specific colostomy concerns include odor/gas, leaking, and skin problems (Grant, et al, Quality of Life Research, 2004). Physical challenges involve difficulty sleeping, decreased strength and fatigue (Krouse, Grant, et al, Journal of Surgical Research, 2007). Psychological problems include depression, anxiety, uncertainty, fear of recurrence of cancer, appearance changes, and the need for privacy (Krouse, Grant, et al, Journal of Surgical Research, 2007). Of special concern are social problems, which make it difficult for some patients with colostomies to participate in social events including eating out, traveling, developing new relationships, overcoming embarrassment, and participating in intimate activities (Mitchell, Rawl, et al, JWOCN, 2007; Krouse, Herrinton, Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2009). Spiritual challenges involve changes in the meaning of life, and developing and maintaining a sense of inner peace and hopefulness (Baldwin, Grant, et al, Journal of Holistic Nursing, 2008). Some of these concerns may be related to the uncontrolled output of stool from the ostomy.

Because several kinds of pouches and pouching systems are available, patients learn over time which system works best for them, and how to apply and use the various systems. Trial and error learning is common as patients learn the relationship between food intake and colostomy output. Concerns for a proper fit, prevention of leaks and resulting skin irritation, and regular empting or replacement of the pouch are part of the routine care ("Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society, Overview White Paper,"). However, even with daily care and a proper fitting pouch, sudden fecal output and odors are not uncommon (McMullen, et al., 2008).

Colostomy irrigation involves instillation of 500 – 1500 ml of tap water into the colon via the stoma to wash out fecal material. This is generally carried out daily or every 2 to 3 days, and results in little or no stool evacuation from the stoma until the next irrigation (Varma, 2009). The procedure takes up to an hour and includes a short (about 6 – 10 minutes) instillation period followed by a evacuation for up to an hour. It is a very old method of continence control, described in 1793 by a French surgeon, Duret, who used the procedure on an infant (reported in O’Bichere, 2000). It was taught and used regularly by those with colostomies (Gabriel, 1927; Gabriel and Lloyd-Davies,1935) until nine colonic perforations and eight deaths related to use of an irrigation cathether were reported (Gabriel, 1945). Equipment improvements in the 1970s and 1980s (use of a cone rather than a straight catheter) have eliminated the occurrence of perforations, but the percentage of colostomists who carry out irrigation remains very low, with reports of 4.7% (Wade, 1989), less than 1% (McCahon , 1999) and less that 2% (O’Bichere, et al, 2000). Eligibility of patients includes regular bowel patterns before surgery, sigmoid or descending colostomy, mentally alert, good dexterity, and a good prognosis (Watt, 1977; Woodhouse, 2005; Rooney, 2007).

Colostomy irrigation has been reported to increase the quality of life of those who use it regularly. Positive effects include no leakage, better sleep, less anxiety, less isolation, increased social comfort, feeling more clean, feeling more confident in intimate situations, and reduced odor (Carlson, 2010, Karadag, et al, 2003, O’Bichere, 2004;Varma, 2009, Gervaz, 2008). Considering how long colostomy irrigation has been used, research on various aspects of the procedure are few. Published studies have focused on bowel activity during and after irrigation (Christiansen, et al, 2002), effects of different solutions (Doran, Hardcastle, 1981, O’Bichere, 2001 and 2004), responses to different amounts of fluid (Gattuso, 1996; Meyhoff, 1990), and positive results from stomatherapy visits or clinics (Karadag, 2003; Terranoma, 1979).

Despite the advantages of colostomy irrigation, health care professionals continue to express concerns about the potential for perforation, mucosal burning, stricture, and loss of bowel tone, even though research on these topics has not been reported (Varma, 2009). No studies were found on the preparation of nurses or generic nursing program content regarding the procedure. Clearly more information is needed on what is included in patient education and rehabilitation regarding colostomy irrigation, when it occurs, and what preparation health care professionals have who provide preoperative and postoperative care for patients who receive permanent colostomies.

Irrigation provides a way to evacuate all or most of the large bowel contents. Following irrigation, it generally takes from 24 – 72 hours before the bowel fills again, and evacuation of fecal material through the stoma occurs. With successful irrigation, it may be possible to use only a cap, mini-pouch, or patch to protect the stoma, making the colostomy less visible through clothing. In addition, leaks and odors are minimized or completely prevented. With this added control over bowel output, the potential for increased independence, decreased work challenges, and increased social activities can again become a part of daily living. Using information gathered from a large population of CRC survivors (>5 years post surgery), this article will describe survivors’ current irrigation use, their characteristics and needs, and the advantages and disadvantages of irrigation as reported by them.

Methods

This large multi-site, multi-investigator study involved a cross-sectional, mailed survey inclusive of demographic data and the modified City of Hope Quality of Life Ostomy (mCOHQOL-O) survey (Mohler, et al., 2008). Reports of the overall study and methods have been published elsewhere (R. S. Krouse, et al., 2009; Mohler, et al., 2008) and will be summarized here. Eligibility for participation included being a current member of the Kaiser Permanente Health Maintenance Organization located in Northern California, Oregon, or Hawaii, 18 years of age or older, diagnosed with CRC at least 5 years prior to the mailing, and history of a major gastrointestinal procedure including major resection of the colon or, rectum, that did (cases) or did not (controls) result in an intestinal stoma. The mCOH-QOL-O consisted of general and ostomy-specific questions. Open-ended optional questions on the mCOH-QOL-O questionnaire related to ostomy equipment problems, irrigation practices, and the greatest challenge encountered in having an ostomy. Only those survey responses among cases related to irrigation are reported here. In one of our sites, information about irrigation practices was collected in telephone interviews. The interview questions are found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Telephone interview questionnaire

In order to obtain more in depth information about challenges associated with living with a colostomy, focus groups were conducted. Participants in the focus groups were eligible if they scored in the top and bottom quartiles on the overall quality of life score on the quantitative survey. Focus groups were divided by gender and by high and low quality of life scores. Gender differences in focus groups analysis have been reported elsewhere (Grant, et al., 2011). Specific information on irrigation practice is reported here.

Analysis included descriptive statistics for quantitative data and content analysis of qualitative data. Qualitative data from interviews of participants who answered yes to the question on irrigation in the mCOH-QOL-O questionnaire or who participated in the telephone interviews included information on why they irrigated and how, if at all, it changed their life. Data were transcribed and assigned for review by the investigative team, and categorized using content analysis. At least two of the investigators reviewed and categorized each comment. Results were shared and coding reviewed by the entire team. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved. For the focus group qualitative data, content was transcribed, separating data into the four groups by gender and by high and low quality of life scores on the mCOH-QOL-O. Analysis of the content followed the same format as the questionnaire and interview data.

RESULTS

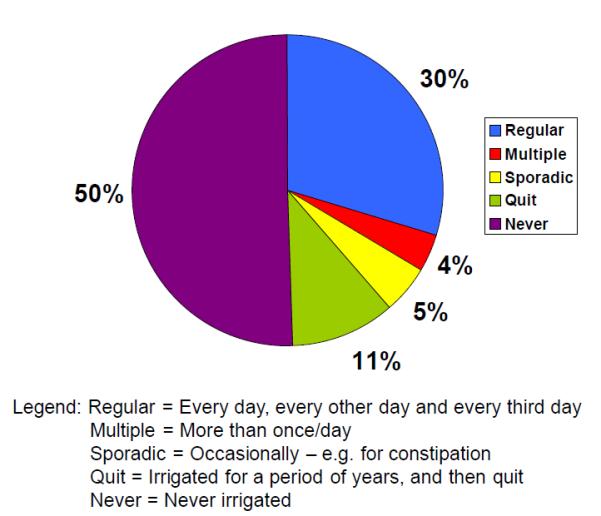

A total of 101 CRC survivors with ostomies completed surveys including questions on irrigation (representing a response rate of 101/173 or 58%). Of these respondents 50% never irrigate, 30% irrigate every 1-3 days, 4% irrigate more than once a day, 5% irrigate sporadically, and 11% were individuals who had irrigated for a period of years, and then quit (Figure 2). For comparison of characteristics by irrigation status, we collapsed irrigations into one group regardless of frequency of irrigation and compared that with former irrigators and those who never irrigated (Table 1). Age was similar in all 3 groups, and ranged from 70.8 years to 76.7 years. Years since surgery were significantly longer in current (p = .002) and former (p < .001) compared to never irrigators. A significantly higher proportion of current irrigators spent more than 60 minutes in daily ostomy care time compared to never irrigators (p < .001) Survey comments from each of these groups illustrate both positive and challenging aspects of irrigation. (Table 2). Positive aspects included controlling output, gas, odor, and being able to function with only a bandaid® over the stoma. Negative aspects all related to the time involved in completing the irrigation procedure. Participants who had irrigated for years, but had subsequently quit, related this change primarily to retiring, moving into assisted living, and/or not having to go to work every day. Participants who said that they had never irrigated, displayed a complete lack of knowledge about irrigation and its purpose. For participants who irrigated, neither gender nor work affected irrigation frequencies. We also found that a trend occurred for older patients to be more likely to irrigate. The longer the time since surgery, the more likely irrigation occurred.

Figure 2.

Irrigation Practice (n=101)

Table 1.

Characteristics by Irrigation Status

| Never N=51 (50%) |

Current N=39 (39%) |

Former N=11 (11%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 70.8 (10.9) | 73.7 (10.2) | 76.7 (11.4) |

| Years since surgery | 8.2 (4.8) | 14.4 (11.5)1 | 20.6 (9.1)2 |

| Male (%) | 58.8 | 66.7 | 54.6 |

| Partnered (%) | 66.7 | 60.5 | 45.5 |

| Charlson score > 2 (%) | 23.5 | 20.5 | 9.1 |

| Ostomy caretime > 30 min (%) | 16.0 | 52.63 | 0.0 |

| Ostomy caretime > 60 min (%) | 6.0 | 21.0 | 0.0 |

| Total QOL | 7.1 (1.6) | 7.0 (1.8) | 7.9 (1.5) |

p =.002 compared to Never

p = .001 compared to Never

p = .003 compared to Former; p,.003 compared to Never

Table 2.

| Comments from mCOH-QOL-O Questionnaire |

|---|

|

|

| POSITIVE APECTS OF IRRIGATION |

|

|

|

| CHALLENGING ASPECTS OF IRRIGATION |

|

|

|

| USED TO IRRIGATE, BUT QUIT |

|

Ten participants commented further on the mCOH-QOL-O open ended question in relation to irrigation. Comments included positive and challenging aspects of irrigation, as well as comments from individuals who did irrigate, but have since stopped (Table 3). Positive comments included control over colostomy output, and maintaining regularity. Challenges related to the time involved in carrying out the procedure.

Table 3.

| Comments from Telephone Interview Participants |

|---|

|

|

| POSITIVE APECTS OF IRRIGATION |

|

|

|

| CHALLENGING ASPECTS OF IRRIGATION |

|

|

|

| USED TO IRRIGATE, BUT QUIT |

|

|

|

| NEVER IRRIGATED |

|

Focus groups involved 33 CRC survivors with 12 men in the high QOL group, 10 women in the high QOL group, 5 men in the low QOL group, and 6 women in the low QOL group. Selected comments are found in Table 4. Positive qualitative comments related irrigation to controlling for odor and gas, and only needing a bandaid® to cover the stoma between irrigations. Challenges included needing up to two hours to complete the irrigation procedure, and having difficulty carrying out the procedure when out of town and traveling. Some participants who were not irrigating expressed an interest in knowing more about irrigation as something they might implement themselves.

Table 4.

Focus Group Comments on Irrigation

| Group | Comment |

|---|---|

| HQOL Women |

|

| LQOL Women |

|

| HQOL Men |

|

| LQOL Men |

|

DISCUSSION

Our results revealed that many positive aspects of irrigation were described by the participants of the survey and the focus groups. While frequency of irrigation varied across participants, the control of output and the elimination of the pouch were identified as positive aspects of irrigation by all of the participants. For participants who were working, irrigation was used to maintain control during working hours. Participants who irrigated indicated that the routines for irrigation were very stable over many years. These results are similar to other reports of irrigation practice. In a study by Karadag et al (2005) on the use of colostomy irrigation in 25 cases in Turkey, quality of life improved significantly in patients who irrigated versus patients who did not (Karadag, Mentes, Ayaz, (2005). These improvements included achieving fecal continence, and improvements in physical problems, social functioning and emotional problems.

Cancer survivors in our study who irrigated their colostomies had more years since their initial surgery than participants who did not use irrigation. Participants who no longer irrigated had the most years since surgery, indicating that their surgical procedure, and initial teaching about ostomy care occurred an average of 21 years ago (SD 9.1). For participants who used irrigation during their working years, the reason for quitting was related to the time it took for the entire procedure. Results indicate that irrigation can control symptoms of output, gas and odor, and eliminate use of a pouch. Participants who quit irrigating were retired, or no longer working, and thus were in a home setting where fecal output, odor, and gas are more tolerated. Others participants quit irrigation after they got older, had reduced functional ability or moved into a nursing facility. They were no longer able to do irrigation themselves and support for the procedure did not occur in the new setting. None of these who stopped irrigating reported any problems when reverting to natural evacuations.

Results showed that 50% of the 101 participants never irrigated their colostomy. Some of these participants said they never heard of irrigation. Colostomy irrigation is most likely to be taught, if at all, by the ostomy nurse, either in the clinical setting and/or by home care nurse in the patient’s home. Initial post operative teaching may cover this aspect briefly, waiting until a bowel pattern is established post operatively before irrigation is begun. It is also likely that irrigation is no longer being taught.

While demonstrating and implementing irrigation may need to take place in the home it should be introduced prior to hospital discharge. It is not certain if irrigation is included in routine teaching of eligible patients in the United States. Ways to provide this education after discharge from the hospital need to be explored. In this era of decreases in health care support, providing this education may be challenging.

Wound, Ostomy, and Continence (WOC) nurses in Sweden were surveyed by Carlsson, et al, 2010), whose study included 61 WOC nurses, a survey of 39 patients, and interviews with 3 patients who used irrigation. Positive aspects were reported by 97% of the participants and included feeling secure in social settings, having an empty pouch, an increased feeling of freedom, enhanced bowel control, feeling cleaner, feeling confident in intimate situations, and having decreased odor and anxiety. Difficulties associated with colostomy irrigation were identified by the nurses, and included radiation therapy, chemotherapy, irritable bowel syndrome, liquid consistency of stool, slow transit time, age, small toilet size, and emotional distress associated with carrying out the procedure. Also mentioned was peristomal hernia, although there is no evidence that this is associated with irrigation. Only 64% of the WOC nurse responders always informed their patients about irrigation and 23% said they do not regularly teach patients to perform irrigation, while 13% stated they do not practice it at all (Carlsson, et al 2010).

Patients interviewed in the Carlsson, et al study (2010), were informed by the WOC nurses about irrigation (95%), with two patients informed by the physician. Directions for irrigation included using this procedure every other day, tap water at 37 degrees centigrade, with instillation lasting 5 to 30 minutes. The total amount used was 500 to 1000 ml over 3 to 10 minutes.

In summary, education and use of irrigation by patients with colostomies has decreased over the years. One of the potential obstacles to the provision of this education is the need to wait until the bowel has recovered and a pattern of evacuation has been established. However, reasons for the decrease in colostomy irrigation remain unexplored. Studies are needed that describe what teaching is provided, when it is provided and by who. Research is also needed to examine concerns by nurses who are reluctant to teach colostomy irrigation. Our results point to the need for additional information regarding teaching colostomy patients about irrigation as a method to control output and its potential to improve the quality of patients’ lives, especially while they are still in the work force.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement: this research was funded by the National Cancer Institute grant (R01-CA106912). Resources and facilities were provided by Southern Arizona Veterans Affair Health Care system and the City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Footnotes

At a Glance:

1. Following creation of a colostomy for colorectal cancer patients, some patients may irrigate their colostomies regularly to gain some bowel control.

2. Results of one large survey included questions about irrigation practices. Cancer survivors who answered these questions were divided into those that did not irrigate, those that did, and those that did irrigate but had stopped.

3. Advantages of irrigation include feeling more in control and safe in public. Challenges of irrigation were concentrated around the amount of time necessary to irrigate daily. Those who had quit, did so after many years, when they retired or moved into assisted living facilities. Some participants had never heard of irrigation, and wanted to know more about it.

4. Findings reveal the need for additional information on what patients with colostomies are taught, how they are taught, and what roles staff nurses and ostomy nurses have in this education.

References

- Altschuler A, Ramirez M, Grant M, Wendel C, Hornbrook MC, Herrinton L, et al. The influence of husbands' or male partners' support on women's psychosocial adjustment to having an ostomy resulting from colorectal cancer. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009;36(3):299–305. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3181a1a1dc. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3181a1a1dc 00152192-200905000-00011 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society Cancer Facts & Figures . American Cancer Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin CM, Grant M, Wendel C, Hornbrook MC, Herrinton LJ, McMullen C, et al. Gender differences in sleep disruption and fatigue on quality of life among persons with ostomies. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(4):335–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin CM, Grant M, Wendel C, Rawl S, Schmidt CM, Ko C, Krouse RS. Influence of intestinal stoma on spiritual quality of life of US veterans. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2008;26(3):185–194. doi: 10.1177/0898010108315185. PubMed PMID: 18664602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson E, Gylin M, Nilsson L, Svensson K, Alverslid I, Persson E. Positive and negative aspects of colostomy irrigation. Journal of Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2010;37(5):511–516. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3181edaf84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen P, Olsen N. Krogh K., Laurberg S. Scintigraphic assessment of colostomy irrigation. Colorectal Disease. 2002;4(5):326–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2002.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colostomy New Patient Guide Retrieved August 7, 2011, from http://www.ostomy.org/ostomy_info/pubs/ColostomyNPG2011.pdf.

- Doran J, Hardcastle JD. A controlled trial of colostomy management by natural evacuation, irrigation and foam enema. Br J Surg. 1981;68(10):731–733. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800681018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel WB. Discussion on colostomy. Proc R Soc Med. 1927;20:1452. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel WB, Lloyd-Davies OV. Colostomy. Br J Surg. 1935;22:520. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel WB. Discussion of the management of the permanent colostomy. Proc R Soc Med. 1945;38:692–694. doi: 10.1177/003591574503801213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattuso JM, Kamm MA, Myers C, Saunders B, Roy A. Effect of different infusion regimens on colonic motility and efficacy of colostomy irrigation. Br J Surg. 1996;83(10):1459–1462. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800831043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervaz P, Bucher P, Konrad B, Morel P, Beyeler S, Lataillade L, Allal A. A Prospective longitudinal evaluation of quality of life after abdominoperineal resection. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97(1):14–19. doi: 10.1002/jso.20910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M, Ferrell B, Dean G, Uman G, Chu D, Krouse R. Revision and psychometric testing of the City of Hope Quality of Life – Ostomy Questionnaire. Quality of Life Research. 2004;13(8):1445–1457. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000040784.65830.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M, McMullen CK, Altschuler A, Mohler MJ, Hornbrook MC, Herrinton LJ, Wendel CS, Baldwin CM, Krouse RS. Gender Differences in Quality of Life Among Long-Term Colorectal Cancer Survivors with Ostomies. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2011;38(5):587–596. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.587-596. PMID: 21875846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karadag A, Mentes BB, Uner A, Irkorucu O, Ayaz S, Ozkan S. Impact of stomatherapy on quality of life in patients with permanent colostomies or ileostomies. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18(3):234–238. doi: 10.1007/s00384-002-0462-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouse R, Grant M, Ferrell B, Dean G, Nelson R, Chu D. Quality of life outcomes in 599 cancer and non-cancer patients with colostomies. J Surg Res. 2007;138(1):79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.04.033. doi: S0022-4804(06)00241-1 [pii] 10.1016/j.jss.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouse RS, Herrinton LJ, Grant M, Wendel CS, Green SB, Mohler MJ, et al. Health-related quality of life among long-term rectal cancer survivors with an ostomy: manifestations by sex. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4664–4670. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9502. doi: JCO.2008.20.9502 [pii] 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Herrinton LJ, Hornbrook MC, Wendel CS, Grant M, Krouse RS. Early and late complications among long-term colorectal cancer survivors with ostomy or anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(2):200–212. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181bdc408. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181bdc408 00003453-201002000-00014 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCahon S. The pre-and postoperative nursing care for patients with a stoma. Br J Surg. 1999;14(6):310–318. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2005.14.6.17799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen CK, Hornbrook MC, Grant M, Baldwin CM, Wendel CS, Mohler MJ, et al. The Greatest Challenges Reported by Long-Term Colorectal Cancer Survivors with Stomas. The Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2008;6(4):175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyhoff HH, Andersen B, Nielsen SL. Colostomy irrigation: a clinical and scintigraphic comparison between three different irrigation volumes. Br J Surg. 1990;77(10):1185–1186. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800771031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KA, Rawl SM, Schmidt CM, Grant M, Ko CY, Baldwin CM, Wendel C, Krouse RS. Demographic, clinical, and quality of life variables related to embarrassment in veterans living with an intestinal stoma. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing. 2007;34(5):524–532. doi: 10.1097/01.WON.0000290732.15947.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler MJ, Coons SJ, Hornbrook MC, Herrinton LJ, Wendel CS, Grant M, et al. The Health-Related Quality of Life in Long-Term Colorectal Cancer Survivors Study: Objectives, Methods and Patient Sample. Current Medical Research and Opinions. 2008;24(7):2059–2070. doi: 10.1185/03007990802118360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Bichere A, Sibbons P, Dore C, Green C, Phillips R.Kl. Experimental study of faecal continence and colostomy irrigation. Br J Surg. 2000;87(7):902–908. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Bichere A, Bossom C, Gangoli S, Green C, Phillips RKS. Chemical colostomy irrigation with glyceryl trinitrate solution. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(9):1324–1327. doi: 10.1007/BF02234792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Bichere A, Green C, Phillips RKS. Randomized cross-over trial of polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution and water for colostomy irrigation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(9):1506–1509. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0621-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney D. Colostomy Irrigation: A personal account of managing a colostomy. The Phoenix. 2007 2007 Jun;:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Terranova O, Sandei F, Rebuffat C, Maruotti R, Bortolozzi E. Irrigation vs. natural evacuation of left colostomy: a comparative study of 340 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1979;22(1):31–34. doi: 10.1007/BF02586753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma S. Issues in irrigation for people with a permanent colostomy: a review. Br J Nurs. 2009;18(4):S15–18. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2009.18.Sup1.39633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade B. A stoma for life: a study of stoma nurses and their patients. Scutari Press; Harrow: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Watt RC. Colostomy irrigation yes or no? American Journal of Nursing. 1977;77(3):442–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse F. Colostomy irrigation: are we offering it enough? Br J Nurs. 2005;14(16):S14–15. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2005.14.Sup4.19737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society Overview White Paper. Retrieved June 28, 2011, 2011, from http://www.wocn.org/pdfs/About_Us/advocacy_and_policy/white_papers.pdf.