Abstract

The present study applied latent class analysis to a sample of 810 participants residing in southern Mississippi at the time of Hurricane Katrina to determine if people would report distinct, meaningful PTSD symptom classes following a natural disaster. We found a four-class solution that distinguished persons on the basis of PTSD symptom severity/pervasiveness (Severe, Moderate, Mild, and Negligible Classes). Multinomial logistic regression models demonstrated that membership in the Severe and Moderate Classes was associated with potentially traumatic hurricane-specific experiences (e.g., being physically injured, seeing dead bodies), pre-hurricane traumatic events, co-occurring depression symptom severity and suicidal ideation, certain religious beliefs, and post-hurricane stressors (e.g., social support). Collectively, the findings suggest that more severe/pervasive typologies of natural disaster PTSD may be predicted by the frequency and severity of exposure to stressful/traumatic experiences (before, during, and after the disaster), co-occurring psychopathology, and specific internal beliefs.

1. Introduction

1.1. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Following Natural Disasters

As many as one in five individuals are exposed to at least one natural disaster over their lifetime (Briere & Elliott, 2000; Norris, 1992). The population prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been found to range between 4% (Canino, Bravo, Rubio, Stipec, & Woodbury, 1990) and 60% (Madakasira & O’Brien, 1987) within two years of a natural disaster, with the highest rates typically occurring in areas that are most heavily affected by the disaster (e.g., Najarian, Goenjian, Pelcovitz, Mandel, & Najarian, 2001). Over the past several years, multiple studies have documented PTSD in the general population following Hurricane Katrina; for example, the past-month prevalence of PTSD was as high as 30.3% (within nine months of Hurricane Katrina) among persons who were living in the New Orleans metropolitan area at the time of the storm (Galea et al., 2007). Consistent with other natural disaster studies (for a review see Neria, Nandi, & Galea, 2008), being female, less educated, unemployed, living in an area with greater disaster exposure (e.g., New Orleans, Mississippi gulf coast), and experiencing a greater number of hurricane-related stressors (e.g., hurricane-specific traumatic events, post-hurricane crime victimization) have all been associated with greater odds of having probable PTSD after Hurricane Katrina (Galea et al., 2007; Galea, Tracy, Norris, & Coffey, 2008; Kessler et al., 2008). Galea and colleagues (2008) also identified economic and social factors that were significantly associated with having probable DSM-IV PTSD subsequent to Hurricane Katrina, including experiencing financial loss as a result of the storm, having fewer social supports, and experiencing a greater number of pre- and post-disaster PTSD Criterion A traumas. More recent studies have also replicated and expanded on these early findings by examining correlates of PTSD following Hurricane Katrina in more circumscribed samples (e.g., veterans, Davis et al., 2012; Vietnamese Americans, Norris, VanLandingham, & Vu, 2009; children, Pina et al., 2008).

1.2. Latent Classes of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms

Although research has helped establish the foundational epidemiology of PTSD after disasters (see Galea, Nandi, & Vlahov, 2005; Neria et al., 2008), this literature has been limited in its evaluation of the heterogeneous nature of PTSD symptoms. For example, theory has underscored the possibility that individuals may experience varying presentations (i.e., typologies) and severities of PTSD symptoms (i.e., Bonanno, 2004; Layne, Warren, Watson, & Shalev, 2007). Consistent with heterogeneous conceptualizations is the polythetic criteria approach utilized by DSM in making a diagnosis of PTSD. That is, some people may experience all 17 DSM-IV-TR symptoms of PTSD while others may present only with the six symptoms that are required to make a diagnosis (i.e., one re-experiencing, three avoidance/numbing, two hyperarousal). Additionally, attending solely to the dichotomous diagnostic outcome of PTSD (as has been done in most natural disaster studies) fails to account for a group of people that fall one or two symptoms short of receiving a diagnosis (e.g., subsyndromal PTSD following a terrorist disaster, Galea et al., 2003). This group of individuals is of particular relevance given research in non-disaster samples suggesting that subthreshold PTSD results in high levels of interference/distress (Stein et al., 1997; Zlotnick et al., 2002).

In an effort to address these limitations, person-centered statistical approaches (i.e., mixture modeling) have emerged that can be used to identify unobserved groups who share similar PTSD symptom presentations. In particular, PTSD symptoms have been examined in samples of persons exposed to Criterion A traumas using latent class analysis (LCA, e.g., Ayer et al., 2011; Maguen et al., 2013; Steenkamp et al., 2013). LCA offers improvements over older person-centered analytic techniques such as cluster analysis by being less restrictive (e.g., not requiring equal indicator variances across classes) and estimating multiple indices of model fit (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007). LCA also permits the regression of classes onto various covariates in order to evaluate differential predictors of class membership in a single step, as opposed to evaluating predictors of most likely class/cluster membership, which does not account for classification uncertainty (see Clark & Muthén, 2009).

Although studies have started to use LCA to examine the heterogeneity of PTSD symptoms and predictors of class membership, extant studies have heavily relied on veteran samples exposed to combat and community samples exposed to interpersonal violence (e.g., assault). Among veterans, two-class (Naifeh, Richardson, Del Ben, & Elhai, 2010), three-class (Steenkamp et al., 2013), or four-class (Maguen et al. 2013) solutions characterized by varying levels of PTSD symptom severity and pervasiveness have been identified (e.g., classes with low/negligible symptoms, intermediate symptoms, and severe/pervasive symptoms). When evaluating combat-specific predictors of class-membership, these studies have also found that veterans exposed to a greater number of wartime stressors (e.g., killing others, witnessing death) are at increased odds of belonging to a severe/pervasive symptom class (Maguen et al., 2013; Steenkamp et al., 2013). Although LCA studies conducted in community samples have typically derived similar three-class solutions (Ayer et al., 2011; Breslau, Reboussin, Anthony, & Storr, 2005), these studies have been unable to provide insight into classes of PTSD following natural disasters because of low rates of natural disaster exposure relative to other traumatic events (e.g., sexual and physical assaults, sudden death of loved ones). It is plausible that natural disasters, which are collectively experienced and can involve multiple traumatic events (e.g., disaster exposure, physical injury, and witnessing death), may result in different classes of PTSD symptoms compared to traumatic events that are more idiographic in nature.

To date, no studies of which we are aware have used LCA to evaluate if people can be classified on the basis of shared PTSD symptoms presentations following a natural disaster Likewise, the literature has yet to evaluate what factors may be relevant in predicting membership in a particular class of PTSD following a natural disaster. Understanding the presence and predictors of different PTSD classes may be particularly important in identifying factors that are associated with experiencing PTSD symptoms at varying levels of pervasiveness and severity (i.e., identifying who is most likely to experience more PTSD symptoms or more severe PTSD following a natural disaster).

1.3. Present Study

Accordingly, the present study aimed to use a person-centered statistical approach to examine the presence of distinct subgroups of natural disaster-related PTSD symptom presentations after Hurricane Katrina. Consistent with prior studies (with similar aims) conducted in veteran and community samples, PTSD symptoms were evaluated using LCA. It was predicted that either a three- or four-class solution would provide acceptable model fit and be the most conceptually interpretable. Specifically, we expected LCA to identify multiple groups characterized by experiencing PTSD symptoms at various levels of severity and pervasiveness (e.g., “Severe” class characterized by a high probability of nearly all PTSD symptoms, “Moderate” class characterized by high probability of a few PTSD symptoms, “Negligible” class characterized by low probability of nearly all PTSD symptoms).

After identifying the optimal LCA solution, the present study also aimed to evaluate predictors of class membership. In particular, we aimed to extend the findings of studies looking at predictors of a PTSD diagnosis after natural disasters by examining the relevance of demographic information, hurricane-specific experiences, depression, pre-hurricane traumatic events, post-hurricane stress, social support, and religious behaviors/beliefs in predicting class membership. Based on the prior natural disaster PTSD literature (e.g., Ali, Farooq, Bhatti, & Kuroiwa, 2012; Arnberg, Hultman, Michel, & Lundin, 2012; Neria et al., 2008), we predicted that potentially traumatic hurricane specific experiences and pre-hurricane trauma would be associated with increased odds of membership in more severe/pervasive PTSD symptom classes, whereas greater social support and stronger religious beliefs were hypothesized to predict membership in mild/unaffected symptom classes.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 810 adults from 23 counties in southern Mississippi affected by Hurricane Katrina. All participants were living in these counties at the time of the storm. An area probability sampling frame was used to select potential participants from counties with the greatest extent of hurricane damage. More specifically, trained listers were used to enumerate pre-hurricane addresses based on aggregations of 2000 Census blocks, and worked diligently to locate individuals who had lived at the selected addresses prior to Hurricane Katrina (e.g., internet, telephone, archival, and in-person searches). In contrast, potential participants residing in counties with less extensive damage were contacted using a random digit dialing sampling frame. Additional details of the sampling strategy are described in Galea et al. (2008).

2.2. Measures

Trained interviewers used a computer-assisted system to gather the data for the present study. Interviews were conducted over several months in 2007, within two years of Hurricane Katrina. Administration of the interview took, on average, 37 minutes. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan and oral informed consent was obtained for all study participants (either in person or over the telephone).

2.2.1. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms

Symptoms of PTSD experienced since Hurricane Katrina were assessed using a modified version of the PTSD module from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Kessler & Ustun, 2004). This module is based on the 17 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) PTSD criteria (five re-experiencing symptoms, seven avoidance/numbing symptoms, five hyperarousal symptoms). All participants in the present study were assumed to have experienced a Criterion A event given their residence at the time of Hurricane Katrina and the inclusion of disasters “such as a major earthquake, hurricane, flood, or tornado” as traumatic events in DSM. Importantly, feelings of helplessness/terror and PTSD symptoms were assessed specifically in reference to Hurricane Katrina with CIDI questions worded to focus on the storm in order to ascertain symptoms of re-experiencing (e.g., “Did you keep remembering Katrina even when you didn’t want to?”, “Did you sweat or did your heart beat fast or did you tremble when you were reminded of Katrina?”), avoidance/numbing (e.g., “Did you deliberately try not to think or talk about Katrina?”), and hyperarousal (e.g., “After Katrina did you become jumpy or easily startled by ordinary noises or movements?). Interviewers coded each symptom as being either present or absent. The average number of PTSD symptoms endorsed was 5.63 (SD = 4.56, Cronbach’s α = 0.90, range = 0 to 17).

2.2.2. Hurricane Katrina Experiences

Interviewers asked participants a series of yes/no questions pertaining to their experience of various potentially traumatic events that may have occurred during the storm (e.g., being physically injured, knowing someone who was injured or killed, seeing dead bodies). In addition to each type of event being evaluated as a predictor of class membership, we also examined a composite rating of total number of different types of potentially traumatic events specific to Katrina (mean number of events = 1.22; SD = .86; range = 0 to 7).).

2.2.3. Depression/Suicide

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001; Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002) was used to assess the nine symptoms of a major depressive episode according to DSM-IV. Using the PHQ-9, interviewers asked participants to rate how often they had been bothered by each symptom since Hurricane Katrina using a 4-point Likert scale (0 = “not to all” to 3 = “nearly every day”). Two predictors of class membership were evaluated using the PHQ-9: (1) total score, representing depression severity (excluding suicidal ideation, Mean = 5.15; SD = 5.47; range = 0 to 25, Cronbach’s α = 0.88), and (2) item 9, which assessed suicidal ideation/intent (i.e., coded dichotomously to represent suicidal ideation occurring “several days or greater” [6.7% of the sample] or “not occurring” [93.3% of the sample]).

2.2.4. Pre-Hurricane Katrina Trauma

Criterion A events, unrelated to and occurring prior to Hurricane Katrina were assessed using a modified version of the traumatic events section of the CIDI (Kessler & Ustun, 2004). The presence/absence of several types of specific events were assessed (e.g., natural disasters other than Hurricane Katrina, assaults with or without a weapon, unwanted sexual contact). Total number of different types of traumatic events occurring prior to Hurricane Katrina was evaluated as a predictor of class membership (Mean = 3.40; SD = 2.24; range = 0 to 10), as was the experience of at least one type of pre-Katrina traumatic event (92.0% of the sample reported trauma exposure prior to the hurricane, see Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Pre-Katrina Traumatic Events and Katrina-Specific Potentially Traumatic Events (N = 810)

| Pre-Katrina Events | N (%) | Katrina-Specific Events | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Disaster | 519 (64.1%) | Present for Significant Wind/Flooding | 584 (72.1%) |

| Serious Accident | 253 (31.2%) | Physically Injured | 43 (5.3%) |

| Assaulted with Weapon | 120 (14.8%) | Knew Someone Injured | 116 (14.3%) |

| Assaulted without a Weapon | 110 (13.6%) | Knew Someone Killed | 134 (16.5%) |

| Unwanted Sexual Contact | 63 (7.8%) | Family Member Injured | 36 (4.4%) |

| Childhood Physical Abuse/Neglect | 73 (9.0%) | Family Member Killed | 27 (3.3%) |

| Military Combat | 68 (8.4%) | Saw Dead Bodies | 51 (6.3%) |

| Life-Threatening Illness | 126 (15.6%) | ||

| Witnessed Injury/Death | 267 (33.0%) | ||

| Unexpected Death | 471 (58.1%) |

Note. The average number of total pre-Katrina Event types endorsed was 3.40. The average number of total Katrina-specific Event types endorsed was 1.22.

2.2.5. Post-Katrina Social Support

Social support during the two months that followed Katrina was assessed using the Crisis Support Scale (CSS; Joseph, Williams, & Yule, 1992). The CSS is a six-item questionnaire that asks respondents how often social support was available using a seven-point Likert scale (range = 1 “never” to 7 “always”): (1) “someone willing to listen to you when you needed to talk,” (2) “contact with other people who were in a similar situation,” (3) “able to talk about your thoughts and feelings with others,” (4) “sympathy and support from others,” (5) “practical help from others,” and (6) “let down by others” (reverse coded). CSS total score was evaluated as a predictor of class membership (Mean = 33.00; SD = 7.83; range = 6 to 42, Cronbach’s α = 0.77).

2.2.6. Religious Beliefs

Interviewers assessed religious behaviors and beliefs related to Hurricane Katrina by asking participants to answer two questions using a four-point Likert scale (range = 1 “not at all” to 4 “a great deal”): (1) the extent to which they turned to God for strength, support, and guidance during the aftermath of the hurricane (Mean = 3.75; SD = 0.61), and (2) the extent they felt God had punished them for their sins or lack of spirituality (Mean = 1.25; SD = 0.67). Importantly, 97.6% of the sample reported that they believed in God or a higher power.

2.2.7. Post-Katrina Stressors

Interviewers also assessed for the presence of eight additional stressors that may have occurred in the six months following the storm: experiencing a shortage of food/water, living in unsanitary conditions, fearing the occurrence of crime, difficulty receiving checks from the government, being displaced from home, difficulty finding housing, difficulty finding a contractor, and losing sentimental possessions (e.g., photographs). The total number of post-Hurricane Katrina stressors was evaluated in the present study (Mean = 2.36; SD = 2.07; range = 0 to 8, Cronbach’s α = 0.72).

2.3. Data Analysis

A series of LCAs were conducted in Mplus 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2009) using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. The 17 DSM-IV PTSD symptoms related to Hurricane Katrina were used as the model indicators. Competing solutions were compared on the basis of model fit indices, interpretability, and parsimony. Statistics under consideration included the loglikelihood, Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), Bayes Information Criteria (BIC), sample size adjusted BIC (i.e., adjustment is sometimes recommended because BIC can overestimate the number of classes when sample size is small or number of indicators is large, see Yang, 2006), entropy, and Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR, Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001). Whereas smaller values of loglikelihood, AIC, and BIC (both unadjusted and sample-size adjusted) indicate better fit to the data (i.e., replication more likely), LMR p values < 0.05 indicate significant improvement in model fit relative to the solution with one less class. Prevailing standards are to accept the solution with the largest number of classes while still having significant LMR. Although not an indication of model fit, higher entropy values represent better between-group distinction (Kline, 2005). In the present study, (non-adjusted) BIC and LMR values were prioritized given evidence that they are the most robust parameters of LCA model fit (Nylund et al., 2007).

Once a final solution was identified, predictors of class membership were evaluated by regressing the latent classes onto the variables of interest in a single step. This approach is preferred to exporting data pertaining to most likely class membership, which does not account for degree of classification uncertainty. Using this approach, Mplus provides a series of multinomial logistic regression models that compares relative class membership on the basis of a particular predictor (e.g., ascertaining if a predictor is associated with increased odds of membership in Class X compared to Class Y). Predictors of interest in the present study included and expanded upon those evaluated as predictors of probable PTSD by Galea and colleagues (2008): demographic information, Hurricane Katrina experiences, pre-hurricane trauma, depression symptoms, suicidality, post-disaster stress, post-disaster social support, and religious behaviors/beliefs.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The sample was mostly White (n = 595, 73.5% or Black (n =159, 19.6%), with fewer individuals identifying as Hispanic (n = 16, 2.0%), Asian (n = 7, 0.9%), or Other (n = 24, 3.0%). Participants tended to be married (n =416, 51.4%) rather than divorced (n = 127, 15.7%) or never married (n = 131, 16.2%). Most participants had at least a high school education (i.e., high school diploma or equivalent n =686, 84.7%), with fewer having less than a high school education (n = 121, 14.9%). The sample was predominately female (n = 552, 68.1%) and the average age of participants was 53.67 (SD = 16.07, range = 18 to 99). The majority of the sample endorsed experiencing a single potentially traumatic event related to Katrina (see Method for descriptive statistics), and the most common event endorsed was being present for hurricane force winds and flooding (n = 584, 72.1%, see Table 1). Although the present study used data pertaining to PTSD symptoms occurring since Hurricane Katrina as indicators in the mixture models, 168 persons (20.7%) in the present sample met criteria for a DSM-IV PTSD diagnosis since Hurricane Katrina (defined as feeling “terrified” or “helpless” during the storm [criterion A2], and having at least one month of one or more [criterion E] of re-experiencing symptoms [criterion B], three or more avoidance symptoms [criterion C], and two or more arousal symptoms [criterion D]). A proportion of the sample also exhibited subthreshold levels of PTSD; whereas 214 persons (26.4%) fell one criterion short of a PTSD diagnosis, 148 (18.3%) were two criteria below diagnostic threshold.

3.2. Latent Class Models

LCA solutions ranging from one- to seven-classes were estimated. Larger class mixture models (e.g., eight- or nine-class) were not estimated because these solutions were unsuccessful at replicating the best loglikelihood value despite increasing the number of random starts (likely indicating that too many classes had been extracted). Goodness of fit statistics from the seven mixture models are presented in Table 1. Fit statistics suggested that either the four- or five-class solution provided the best fit to the data. For example, whereas the four-class solution evidenced the lowest BIC (12430.035) and a significant LMR (p-value = 0.016), the five-class solution had the lowest sample-size adjusted BIC (12149.601) and a LMR value that verged on marginal statistical significance (p-value = 0.046). The more parsimonious four-class solution was ultimately determined to be the best fitting model because it was the most conceptually interpretable and consistent with prior LCA studies of PTSD symptoms (i.e., typically arriving at three or four-class models characterized by mild, moderate, and severe classes; Ayer et al., 2011; Maguen et al., 2013; Steenkamp et al. 2012). Moreover, recent simulation studies suggest that the unadjusted BIC is best at identifying the optimal solution (Nylund et al., 2009)

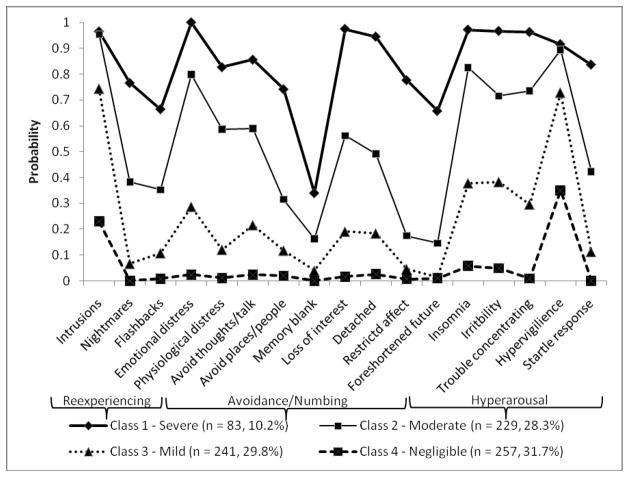

Figure 1 displays the estimated within-class probabilities of the 17 PTSD symptoms for the four-class solutions. Classes were identified as the: (1) “Severe Class” (10.2% of the sample), characterized by a high probability (> 0.70, cf. Maguen et al. 2013) of endorsing 14 PTSD symptoms (four re-experiencing, five avoidance/numbing, five hyperarousal); (2) “Moderate Class” (28.3% of the sample), characterized by a high probability of endorsing six PTSD symptoms (two re-experiencing, four hyperarousal); (3) “Mild Class” (29.8% of the sample), characterized by a high probability of endorsing two PTSD symptoms (one re-experiencing, one hyperarousal); and (4) “Negligible Class” (31.7% of the sample), characterized by a low probability (< 0.30) of endorsing 16 of the PTSD symptoms. In regards to the within-class prevalence of a PTSD diagnosis, 88% of the Severe Class, 40.2% of the Moderate Class, .4% of the Mild Class, and 0% of the Negligible Class met criteria for PTSD since Hurricane Katrina using the definition outlined above. The mean probabilities of class membership from the four-class solution reflected adequate class discrimination: 91.1% for the “Severe” Class, 89.4% for the “Moderate” Class, 87.7% for the “Mild” Class, and 86.3% for the “Negligible” Class. 1

Figure 1.

Plotted Estimated Probabilities of Endorsing Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms for the Four-Class Solution.

3.3. Multinomial Regression Models

Multinomial logistic regression models were used to evaluate predictors of class membership based on the more parsimonious four-class solution (i.e., a separate model was evaluated for each predictor).2 Results of these models may be found in Table 2. Only predictors consistently associated (i.e., compared to at least two reference classes) with increased odds of Severe and Moderate Class membership are presented here. Compared to the Moderate, Mild, and Negligible Classes, membership in the Severe Class was consistently predicted by having less than a high school education (e.g., persons with a high school education were .26 times less likely to be classified by the Severe Class compared to the Moderate Class), experiencing greater severity of depression and the presence of suicidal ideation, having a greater number of types of pre-hurricane traumatic events, having fewer post-hurricane social supports, experiencing a greater number of post-hurricane stressors, and beliefs that the hurricane was a form of punishment from God. Persons also had greater odds of membership in the Severe Class compared to the Mild and Negligible Classes if they belonged to a non-White racial group, were personally injured by or knew others who were injured by the storm (including family), saw dead bodies during or after the storm, or had a greater total number of potentially traumatic Katrina-specific events.

Table 2.

Model Fit of Latent Class Solutions

| Model | Log-likelihood | BIC | Adj. BIC | AIC | Entropy | LMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 class | −7838.821 | 15791.493 | 15737.508 | 15711.643 | n/a | n/a |

| 2 class | −6298.084 | 12830.564 | 12719.419 | 12666.168 | 0.909 | < 0.001 |

| 3 class | −6063.940 | 12482.823 | 12314.517 | 12233.880 | 0.870 | < 0.001 |

| 4 class | −5977.273 | 12430.035 | 12204.568 | 12096.545 | 0.802 | 0.016 |

| 5 class | −5918.096 | 12432.228 | 12149.601 | 12014.192 | 0.809 | 0.046 |

| 6 class | −5887.244 | 12491.071 | 12151.283 | 11988.488 | 0.819 | 0.280 |

| a7 class | −5862.419 | 12561.968 | 12165.020 | 11974.839 | 0.836 | 0.205 |

Note. The bolded solution was determined to be the final model. BIC = Bayesian information criterion; Adj. BIC = Sample size adjusted Bayesian information criterion; AIC = Akaike information criterion; LMR = Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ration test; BLRT = bootstrap likelihood ratio test;

best log-likelihood value could not be replicated despite increasing the number of random starts.

Several of the same predictors were significantly associated with membership in the Moderate Class compared to the Mild and Negligible Classes. Specifically, experiencing more total number of Katrina-specific potentially traumatic events, having greater depression severity and suicidal ideation, and having a greater number of post-hurricane stressors were all associated with increased odds of being classified by the Moderate Class compared to the Mild and Negligible Classes. In addition, compared to the Mild and Negligible Classes, people also had greater odds of Moderate Class membership if they felt helpless or terrified during the storm, were not married, or knew someone who was killed as a result of the storm. 3

4. Discussion

Whereas prior examinations of PTSD following natural disasters have failed to consider the heterogenous nature of PTSD symptom presentations prior LCA studies of PTSD have not included population-based samples exposed to natural disasters. Thus, the present study extends the extant literature by being the first, as far as we are aware, to examine classes of PTSD and predictors of class membership in a large community sample exposed to a single natural disaster (i.e., Hurricane Katrina). Collectively, the results indicate that persons exposed to natural disasters may be classified into meaningful groups on the basis of severity and pervasiveness of PTSD symptoms (i.e., the total number and type of PTSD symptoms), and that class membership is differentially predicted by one’s experiences prior to, during, and after the disaster (e.g., pre-disaster trauma, knowing someone who was killed, post-disaster stress), levels of social support, depression and suicidal ideation, and specific religious beliefs.

The four-class solution determined to provide the best fit to the data is consistent with study hypotheses as well as at least one prior LCA study of PTSD symptoms conducted in a veteran population exposed to combat (Maguen et al., 2013). Although prior research conducted in community and other veteran samples have more frequently derived three-class solutions (Ayer et al., 2011; Breslau et al., 2005; Steenkamp et al., 2013), the four-class solution presented here is still in line with findings from these studies in identifying classes characterized by varying severity and pervasiveness of PTSD symptoms (e.g., low, moderate, and severe/pervasive levels of PTSD symptoms).

Several patterns of symptom endorsement probability were found across the four classes. For example, whereas persons in the Severe, Moderate, and Mild Classes all had a high likelihood of experiencing intrusive thoughts and hypervigilance since Hurricane Katrina (i.e., probability ≥ 0.70 across all three classes), only those classified in the Severe Class had a high likelihood of experiencing avoidance/numbing symptoms (i.e., five of the seven avoidance/numbing symptoms had a probability ≥ 0.70 in the Severe Class). As the Severe Class was associated with a high probability of having 14 PTSD symptoms and 88% of the class carried a probable PTSD diagnosis, this may indicate that the presence of avoidance/numbing symptoms are particularly salient in identifying people with the most severe type of PTSD following a natural disaster. Consistent with this hypothesis, prominent cognitive-behavioral conceptual models of PTSD underscore the role of avoidance in the development and maintenance of re-experiencing and hyperarsoual symptoms; that is, avoidance of trauma cues (e.g., doing things to suppress thoughts, images, memories, and their associated negative emotions) can prevent adaptive extinction and emotional processing, and subsequently increase and maintain the symptoms of PTSD via principles of negative reinforcement (see Cahill & Foa, 2007). Alternatively, persons in the Severe Class may have also displayed a high probability of experiencing avoidance/numbing symptoms because of the overlap of these symptoms with other emotional disorders (e.g., depression severity was also associated with membership in the Severe Class, and depression may also be characterized by restricted affect and loss of interest).

By contrast, none of the classes were associated with a high probability of difficultly remembering aspects of the storm (i.e., probability of ≤ 0.40 across all four classes). These findings are consistent with both the natural disaster and latent class PTSD literature that has typically found intrusive thoughts and hypervigilance to be among the most frequently endorsed PTSD symptoms, whereas memory loss is one of the least common (e.g., Breslau et al., 2005; Maguen et al., 2013; McMillen, North, & Smith, 2000; Norris et al., 2009; Steenkamp et al., 2012). The high probability of intrusive thoughts and hypervigilance that was found across classes in the present sample suggests that a majority of people (i.e., 68.3% of the sample were placed in the Severe, Moderate, or Mild) will experience at least a few symptoms of PTSD following exposure to a natural disaster such as Hurricane Katrina.

The Moderate Class was associated with a high probability of endorsing six PTSD symptoms, thus making it unsurprising that only 40.2% of this class carried a probable PTSD diagnosis following Hurricane Katrina. Although at least one re-experiencing, three avoidance/numbing, and two hyperarousal symptoms must be present in order to diagnosis PTSD, it is important to note that the Moderate Class was not associated with a high likelihood of endorsing any avoidance/numbing symptoms. No avoidance/numbing symptoms displayed estimated probabilities ≥ 0.70, and only two symptoms had probabilities ≥ 0.50. This indicates that, following natural disasters, a group of persons may experience several re-experiencing (e.g., intrusive thoughts, emotional distress when exposed to reminders) and hyperarousal (e.g., insomnia, irritability, concentration problems, hypervigilance) symptoms while failing to meet the threshold for a DSM diagnosis of PTSD because of a low likelihood of endorsing avoidance/numbing symptoms. Given data collected in non-disaster samples suggesting that subthreshold PTSD may result in high levels of interference/distress (Stein et al., 1997; Zlotnick et al., 2002) and a plethora of negative outcomes (e.g., increased suicidality; see Marshall et al., 2001), it seems feasible that the 59.8% of those in the Moderate Class who did not meet criteria for a diagnosis may have still experienced impairing and clinically significant PTSD symptoms. Although nearly all of the natural disaster literature has examined the diagnosis of PTSD as the primary outcome of interest, these findings underscore the importance of future research that also examines correlates of subthreshold PTSD symptoms among persons exposed to natural disasters (e.g., is subthreshold PTSD following a natural disaster as impairing and distressing as a full diagnosis?).

Along these lines, the present study expands on prior natural disaster studies that have solely evaluated correlates of a PTSD diagnosis by evaluating predictors of membership in the four PTSD classes. With a few exceptions (e.g., being female was not consistently associated with Severe or Moderate Class membership), several findings from the multinomial logistic regression models were in line with the natural disaster PTSD literature (e.g., Arnberg et al., 2012; Neria et al., 2008; Galea et al., 2007; Galea et al., 2008). For example, exposure to potentially traumatic disaster-specific experiences and post-disaster stressors were all associated with increased odds of Severe and Moderate Class membership (compared to both the Mild and Negligible Classes). The Severe Class was also consistently associated with having lower educational attainment, greater pre-disaster trauma exposure, and less social support (compared to the Moderate, Mild, and Negligible Classes), suggesting that education level, prior trauma exposure, and social support may be particularly salient risk factors in developing more severe/pervasive PTSD symptoms following a natural disaster. In contrast, total number of potentially traumatic Katrina-specific events was not associated with greater odds of membership in the Severe Class compared to the Moderate Class. This indicates that although having traumatic events is associated with greater likelihood of having PTSD symptoms, this predictor does not differentiate persons with more severe PTSD symptoms from those who may fall a few symptoms short of the PTSD diagnostic threshold (i.e., persons placed in the Moderate Class). In other words, number of disaster specific traumatic events does not appear to have an additive effect on the probability of endorsing PTSD symptoms beyond the diagnostic threshold.

Although prior studies have found that stronger religious beliefs may protect people from developing PTSD following natural disasters (e.g., Ali et al., 2012; Wilson & Moran, 1998), “turning to God” for support following Hurricane Katrina was not associated with decreased odds of Severe or Moderate Class membership in the present study. Importantly, this item may have been unable to differentiate class membership because of the overall high prevalence of religious persons in our sample; 97.6% reported believing in God or a higher power, and 91.8% of these persons endorsed turning to God “some” or “a great deal” following the storm (e.g., compared to Ali et al., 2012 where 50% of the sample identified themselves as “religious minded”). Interestingly, endorsing the belief that the disaster was punishment from God was uniquely associated with increased odds of membership in the Severe Class compared to all other classes (i.e., it was not associated with membership in the Moderate Class). This finding is in line with one study that found beliefs in karma (i.e., punishment/retribution for sins) predicted PTSD symptoms following a tsunami (Levy, Slade, & Ranasinghe, 2009) as well as other studies that have found beliefs in a punishing God to predict PTSD symptoms following a broad range of Criterion A trauma (Wortmann, Park, & Edmondson, 2011) and symptoms of depression related to physical health complications (e.g., chronic pain, Parenteau et al., 2011). Overall, these results underscore how the circumscribed content of one’s religious beliefs may be important to consider in the study of PTSD following a natural disaster.

We also found that co-morbid depression severity and the presence of suicidal ideation were consistently associated with differing odds of class membership. This is generally consistent with prior natural disaster research that has found high rates of comorbidity between PTSD and depressive disorders (e.g., Foa, Stein, & McFarlane, 2006; Nillni et al., in press) and that PTSD predicts suicide risk (even when controlling depression; e.g., Tang et al., 2010). However, these findings also add to natural disaster literature focusing solely on a diagnosis of PTSD by showing that depression severity and suicidal ideation are able to differentiate persons who experience the more severe/pervasive PTSD symptoms (i.e., the Severe Class), from persons who have less severe/pervasive symptoms (i.e., the Moderate Class), as well as those who have negligible PTSD symptoms (i.e., the Mild and Negligible Classes). In particular, the presence of suicidal ideation was associated with very strong odds of membership in the Severe Class (ORs range = 4.11 to 142.91 compared to the Moderate, Mild, and Negligible Classes), suggesting that persons with suicidal ideation following a natural disaster are more likely to be experiencing nearly every symptom of PTSD.

Despite the strengths of the present study (e.g., assessing PTSD symptoms specifically as a result of Hurricane Katrina; first application of mixture modeling in a large sample exposed to a natural disaster), several limitations must also be acknowledged. Consistent with prior research conducted in natural disaster samples, the present study assessed PTSD symptoms in a dichotomous fashion using a structured assessment designed for lay interviews (i.e., the CIDI). Although the CIDI has been widely used and validated (e.g., Haro et al., 2006; Kessler et al,. 2004), future natural disaster research may wish to evaluate classes (i.e., profiles) of PTSD using clinician-administered dimensional assessments of PTSD that would be less prone to measurement error (e.g., Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale, Blake et al,. 1995). Along these lines, some of the correlates of interest (e.g., suicidal ideation, religious beliefs) may have suffered increased measurement error because they were assessed using single questions rather than multi-item measures (i.e., because of the time constraints associated with telephone survey research). As a consequence, the 95% confidence interval for several of these dichotomous single item predictors was very large (e.g., suicidal ideation), suggesting a degree of uncertainty surrounding these odds ratios. The cross-sectional nature of the PTSD symptom assessment is another limitation; in addition to precluding firm conclusions about the directionality of the predictors of class membership (e.g., does the presence of PTSD symptoms lead to social isolation and reduced social support or vice versa?), the cross-sectional PTSD symptom data did not allow for a replication of the four-class solution over time (see Au, Dickstein, Comer, Salters-Pedneault, & Litz, 2013) or evaluation of the stability of class membership (e.g., do people change classes over time? i.e., latent transition analysis, see Dauber, Paulson, & Leiferman, 2011; Lanza, Patrick, & Maggs, 2010 for examples of using this approach with substance use behaviors).

Although these findings provide promising initial support for the importance of studying PTSD as a heterogeneous construct following natural disasters, future research is needed to continue to validate PTSD classes in natural disaster samples. For example, studies should continue to evaluate the clinical utility of distinguishing people on the basis of class membership (e.g., do people in the Moderate Class have clinically significant but subthreshold PTSD symptoms?) Moreover, longitudinal studies with multiple assessments of PTSD symptoms would allow for evaluations of the stability of class membership over time. For example, it seems feasible that people in the Severe Class may be more likely to experience chronic symptoms of PTSD, whereas people in the Moderate Class may experience a natural remission of their symptoms (e.g., because they are less likely to experiencing avoidance symptoms). Along these lines, growth mixture modeling has been increasingly applied to longitudinal samples of individuals with PTSD (e.g., Armour, Shevlin, Elkit, & Mroczek, 2012; Orcutt, Erickson, & Wolfe, 2004), including at least one recent examination that found three classes of PTSD symptom trajectories following a natural disaster (e.g., resistant to symptoms, chronically elevating symptoms, and delay onset symptoms, Pietrzak, Van Ness, Fried, Galea, & Norris, 2013).

In summary, results from the present study shows that people who are exposed to natural disasters may be differentiated into subgroups on the basis of severity and pervasiveness of PTSD symptoms. Moreover, these classes of natural disaster PTSD may be differentially associated with (i.e., predicted by) educational attainment, individual experiences before, during, and after the disaster, depression severity and suicidal ideation, social support, and the content of specific religious beliefs. Overall, these findings highlight and underscore the presence of empirically-based subtypes of PTSD symptom presentations following a natural disaster, and how we may be able to identify those who may be in the greatest need of mental health care services (i.e., members and predictors of the Severe and Moderate Classes).

Table 3.

Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals from the Multinomial Logistic Regression Models Predicting Class Membership

| C1 vs. C2: Severe vs. Moderate | C1 vs. C3: Severe vs. Mild | C1 vs. C4: Severe vs. Negligible | C2 vs. C3: Moderate vs. Mild | C2 vs. C4: Moderate vs. Negligible | C3 vs. C4: Mild vs. Negligible | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||||

| Female | 0.59 (0.29–1.21) | 0.83 (0.44–1.60) | 1.33 (0.69–.2.58) | 1.42 (0.86–2.36) | 2.26*** (1.45–3.52) | 1.59 (0.97–2.60) |

| Age | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.97** (0.95–0.99) | 0.99 (0.99–1.01) | 0.97** (0.95–0.99) | 0.97** (0.95–0.99) |

| Married | 1.35 (0.73–2.49) | 0.81 (0.46–1.40) | 0.88 (0.50–1.54) | 0.60* (0.38–0.94) | 0.65* (0.43–0.98) | 1.09 (0.68–1.73) |

| Blacka | 1.30 (0.59–2.86) | 1.89 (0.93–3.84) | 3.07** (1.31–7.19) | 1.45 (0.77–2.75) | 2.36* (1.21–4.62) | 1.63 (0.68–3.90) |

| Whitea | 0.86 (0.39–1.87) | 0.50* (0.25–0.99) | 0.40* (0.19–0.84) | 0.59 (0.31–1.09) | 0.46** (0.27–0.79) | 0.79 (0.39–1.61) |

| High School Education | 0.26** (0.11–0.65) | 0.15*** (0.06–0.36) | 0.13*** (0.05–0.33) | 0.57 (0.31–1.07) | 0.51* (0.29–0.91) | 0.89 (0.45–1.76) |

| Katrina Specific Experiences | ||||||

| Felt Helpless or Terrified | 1.26 (0.26–6.14) | 3.13 (0.90–11.01) | 17.50*** (4.79–64.00) | 2.48* (1.06–5.81) | 13.85*** (6.85–28.00) | 5.59*** (3.01–10.40) |

| Wind/Flooding | 1.43 (0.73–2.79) | 1.33 (0.70–2.51) | 1.03 (0.52–2.01) | 0.93 (0.57–1.51) | 0.72 (0.45–1.16) | 0.77 (0.44–1.37) |

| Physically Injured | 2.17 (0.80–5.85) | 7.46** (2.04–27.27) | 7.08** (2.09–23.95) | 3.44 (0.87–13.56) | 3.27* (1.09–9.83) | 0.95 (0.17–5.24) |

| Knew Someone Injured | 1.40 (0.65–3.02) | 2.52* (1.18–5.39) | 4.05** (1.76–9.34) | 1.80 (0.87–3.74) | 2.90** (1.45–5.80) | 1.61 (0.66–3.92) |

| Knew Someone Killed | 0.83 (0.39–1.77) | 1.51 (0.74–3.07) | 3.23** (1.36–7.67) | 1.81* (1.03–3.18) | 3.88*** (2.00–7.52) | 2.15 (0.99–4.68) |

| Family Member Injured | 1.66 (0.55–5.05) | 3.53* (1.07–11.62) | 7.60* (1.52–38.02) | 2.12 (0.68–6.66) | 4.58* (1.03–20.35) | 2.16 (0.34–13.67) |

| Family Member Killed | 1.62 (0.49–5.40) | 2.52 (0.73–8.65) | 5.57* (1.16–26.85) | 1.56 (0.53–4.53) | 3.44 (0.83–14.28) | 2.21 (0.45–10.94) |

| Saw Dead Bodies | 2.12 (0.90–5.01) | 4.07** (1.53–10.83) | 8.49** (2.15–33.62) | 1.92 (0.74–4.98) | 4.01* (1.10–14.63) | 2.09 (0.40–10.84) |

| Number Potential Katrina Traumas | 1.24 (.97–1.58) | 1.70*** (1.32–2.19) | 1.97*** (1.53–2.53) | 1.37*** (1.08–1.75) | 1.60*** (1.29–1.97) | 1.16 (.91–1.48) |

| Depression | ||||||

| PHQ Total | 1.24*** (1.15–1.33) | 1.59*** (1.31–1.78) | 2.13*** (1.81–2.50) | 1.29*** (1.19–1.41) | 1.72*** (1.48–1.99) | 1.38** (1.16–1.55) |

| Suicidal Ideation | 4.11* (1.23–13.77) | 24.22*** (5.93–98.97) | 142.91*** (9.23–2212.44) | 5.89** (1.81–19.21) | 34.76** (2.89–418.41) | 5.90 (0.37–93.94) |

| Pre-Katrina Trauma | ||||||

| Number Different Trauma Events | 1.17* (1.02–1.35) | 1.33*** (1.17–1.52) | 1.33*** (1.17–1.52) | 1.14 (1.00–1.29) | 1.13* (1.03–1.26) | 1.00 (0.88–1.13) |

| Any Traumas | 1.42 (0.32–6.41) | 1.93 (0.54–6.87) | 2.70 (0.74–9.81) | 1.36 (0.47–3.92) | 1.90 (0.84–4.29) | 1.40 (0.62–3.17) |

| Post-Katrina Support/Stress | ||||||

| Total Social Support Score | 0.95** (0.92–0.98) | 0.91*** (0.87–0.94) | 0.94** (0.90–0.97) | 0.96* (0.92–0.99) | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) |

| Number of Stressors | 1.21** (1.06–1.39) | 1.60*** (1.39–1.85) | 2.69*** (2.15–3.35) | 1.33*** (1.17–1.51) | 2.22*** (1.83–2.69) | 1.67*** (1.37–2.05) |

| Religious Beliefs | ||||||

| Strength/Support from God | 0.75 (0.47–1.20) | 0.72 (0.46–1.11) | 0.96 (0.65–1.44) | 0.96 (0.59–1.54) | 1.29 (0.89–1.86) | 1.35 (0.87–2.10) |

| Punishment from God | 1.56* (1.04–2.34) | 1.68** (1.15–2.44) | 1.93** (1.31–2.85) | 1.08 (0.66–1.76) | 1.24 (0.87–1.76) | 1.15 (0.73–1.83) |

Note. Second class is the reference class (e.g., in the Severe vs. Moderate column, the Moderate Class is the reference class). 95% confidence intervals are in parentheses. Except for age, all predictors related to demographics and Katrina experiences were dichotomous in nature (e.g., married versus not married; white versus non-white; black versus non-black).

Other racial and ethnic demographics were not evaluated as predictors of class membership due to low base rates in the present sample (e.g., 97.1% of the sample identified as non-Hispanic White or non-Hispanic Black).

Highlights.

Predictors of natural disaster PTSD latent classes were examined

Four classes of varying PTSD symptom severity/pervasiveness were found

Disaster experiences and stressors predicted membership in more severe/pervasive classes

Prior trauma, comorbid depression, and specific religious beliefs predicted membership in more severe/pervasive classes

Greater social support predicted membership in less severe/pervasive classes

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant MH 078152 (PI: Galea) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Four of the classes identified in the five-class solution were nearly identical to those from the four-class solution: a (1) “Severe” Class (6.5% of the sample), characterized by a high probability of endorsing 15 PTSD symptoms, (2) “Moderate” Class (19.6% of the sample), characterized by a high probability of endorsing five PTSD symptoms, (3) “Mild” Class (29.5% of the sample), characterized by a high probability of endorsing two PTSD symptoms, and (4) “Negligible” Class (32.7% of the sample), characterized by a low probability of endorsing 16 PTSD symptoms. The additional class derived from the five-class solution appeared to reflect a (5) “Withdrawn” Class (11.5% of the sample), characterized by a high probability of endorsing eight PTSD symptoms (including > 0.80 probability of endorsing loss of interest and emotional detachment).

Adding covariates to an LCA model can change both the prevalence and sometimes structure of the classes. Accordingly, as covariates were added our model, the probability coefficients, visual profile, and class prevalences were inspected and compared to the baseline model with no covariates. There were no substantive differences between the baseline and covariate models.

For exploratory purposes, we also evaluated multinomial regression models to specifically evaluate predictors of membership in the Withdrawn Class using the five-class solution. Compared to the Moderate, Mild, and Negligible Classes, membership in the Withdrawn Class was predicted by having knowing someone who was injured because of the storm, having a greater number of disaster-specific potentially traumatic experiences, experiencing increased severity of depression and having suicidal ideation, experiencing a greater number of types of pre-hurricane traumatic events, having fewer post-hurricane social supports, and having a greater number of post-hurricane stressors. Knowing someone who was killed during the storm was also associated with increased odds of Withdrawn Class membership compared to the Mild and Negligible Classes.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ali M, Farooq N, Bhatti MA, Kuroiwa C. Assessment of prevalence and determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of earthquake in Pakistan using Davidson Trauma Scale. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136:238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour C, Shevlin M, Elklit A, Mroczek D. A latent growth mixture modeling approach to PTSD symptoms in rape victims. Traumatology. 2012;18:20–28. doi: 10.1177/1534765610395627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnberg FK, Hultman CM, Michel P, Lundin T. Social support moderates posttraumatic stress and general distress after disaster. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25:721–727. doi: 10.1002/jts.21758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au TM, Dickstein BD, Comer JS, Salters-Pedneault K, Litz BT. Co-occurring posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms after sexual assault: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.026. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayer L, Danielson C, Amstadter AB, Ruggiero K, Saunders B, Kilpatrick D. Latent classes of adolescent posttraumatic stress disorder predict functioning and disorder after 1 year. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:364–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. Loss, Trauma, and Human Resilience: Have We Underestimated the Human Capacity to Thrive After Extremely Aversive Events? American Psychologist. 2004;59:20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Elliott D. Prevalence, characteristics, and long-term sequelae of natural disaster exposure in the general population. Journal of traumatic stress. 2000;13:661–679. doi: 10.1023/A:1007814301369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill SP, Foa EB. Psychological theories of PTSD. In: Friedman M, Keane T, Resick P, editors. Handbook of PTSD: Science and practice. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 55–7. [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Bravo M, Rubio-Stipec M, Woodbury M. The impact of disaster on mental health: prospective and retrospective analyses. International Journal of Mental Health. 1990;19:51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Clark SL, Muthén B. Unpublished Manuscript. 2009. Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Dauber SE, Paulson JF, Leiferman JA. Race-specific transition patterns among alcohol use classes in adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TD, Sullivan G, Vasterling JJ, Tharp A, Han X, Deitch EA, Constans JI. Racial variations in postdisaster PTSD among veteran survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2012;4:447–456. [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Naifeh JA, Forbes D, Ractliffe KC, Tamburrino M. Heterogeneity in clinical presentations of posttraumatic stress disorder among medical patients: Testing factor structure variation using factor mixture modeling. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24:435–443. doi: 10.1002/jts.20653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Stein DJ, McFarlane AC. Symptomatology and psychopathology of mental health problems after disaster. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiological studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17:643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M, Jones RT, King DW, King LA, Kessler RC. Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1427. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2005;27:78–91. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxi003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Tracy M, Norris F, Coffey SF. Financial and social circumstances and the incidence and course of PTSD in Mississippi during the first two years after Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:357–368. doi: 10.1002/jts.20355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Vlahov D, Resnick H, Ahern J, Susser E, Gold J, Kilpatrick D. Trends of probable post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;158:514–524. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, De Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, Kessler RC. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2006;15:167–180. doi: 10.1002/mpr.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S, Williams R, Yule W. Crisis support, attributional style, coping style, and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences. 1992;13:1249–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, Escobar JI, Gibbon M, Guyer ME, Zheng H. Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:122–139. doi: 10.1002/mpr.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Galea S, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Ursano RJ, Wessely S. Trends in mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina. Molecular Psychiatry. 2008;13:374–384. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression and diagnostic severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32:509–521. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Patrick ME, Maggs JL. Latent transition analysis: benefits of a latent variable approach to modeling transitions in substance use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2010;40:93–120. doi: 10.1177/002204261004000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layne CM, Warren JS, Watson PJ, Shalev AY. Risk, vulnerability, resistance, and resilience: Towards an integrative conceptualization of posttraumatic adaptation. In: Friedman M, Keane T, Resick P, editors. Handbook of PTSD: Science and practice. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 497–520. [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Slade MD, Ranasinghe P. Causal thinking after a tsunami wave: Karma beliefs, pessimistic explanatory style and health among Sri Lankan survivors. Journal of Religion and Health. 2009;48:38–45. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madakasira S, O’Brien KF. Acute posttraumatic stress disorder in victims of a natural disaster. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 1987;175:286. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen S, Madden E, Bosch J, Galatzer-Levy I, Knight SJ, Litz BT, McCaslkin SE. Killing and latent classes of PTSD symptoms in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;145:344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall RD, Olfson M, Hellman F, Blanco C, Guardino M, Struening EL. Comorbidity, impairment, and suicidality in subthreshold PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1467–1473. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen JC, North CS, Smith EM. What parts of PTSD are normal: Intrusion, avoidance, or arousal? Data from the Northridge, California, earthquake. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13:57–75. doi: 10.1023/A:1007768830246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus 5.2 [Computer software] Los Angeles: Author; 1998–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Naifeh JA, Richardson JD, Del Ben KS, Elhai JD. Heterogeneity in the latent structure of PTSD symptoms among Canadian veterans. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22:666–674. doi: 10.1037/a0019783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najarian LM, Goenjian AK, Pelcovitz D, Mandel F, Najarian B. The effect of relocation after a natural disaster. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:511–526. doi: 10.1023/A:1011108622795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neria Y, Nandi A, Galea S. Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:467–480. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nillni YI, Nosen E, Williams PA, Tracy M, Coffey SF, Galea S. Unique and related predictors of major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and their comorbidity following Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182a430a0. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH. Epidemiology of trauma: Frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:409–418. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, VanLandingham MJ, Vu L. PTSD in Vietnamese Americans following Hurricane Katrina: Prevalence, patterns, and predictors. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22:91–101. doi: 10.1002/jts.20389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt HK, Erickson DJ, Wolfe J. The course of PTSD symptoms among Gulf War veterans: a growth mixture modeling approach. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:195–202. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029262.42865.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parenteau SC, Hamilton NA, Wu W, Latinis K, Waxenberg LB, Brinkmeyer MY. The mediating role of secular coping strategies in the relationship between religious appraisals and adjustment to chronic pain: The middle road to Damascus. Social Indicators Research. 2011;104:407–425. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Van Ness PH, Fried TR, Galea S, Norris FH. Trajectories of posttraumatic stress symptomatology in older persons affected by a large-magnitude disaster. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2013;47:520–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pina AA, Villalta IK, Ortiz CD, Gottschall AC, Costa NM, Weems CF. Social support, discrimination, and coping as predictors of posttraumatic stress reactions in youth survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:564–574. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp MM, Nickerson A, Maguen S, Dickstein BD, Nash WP, Litz BT. Latent classes of PTSD symptoms in Vietnam veterans. Behavior Modification. 2012;36:857–874. doi: 10.1177/0145445512450908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Walker JR, Hazen AL, Forde DR. Full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from a community survey. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1114–1119. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.8.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang T, Yen C, Cheng C, Yang P, Chen C, Yang R, Yu H. Suicide risk and its correlate in adolescents who experienced typhoon-induced mudslides: A structural equation model. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:1143–1148. doi: 10.1002/da.20748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JP, Moran TA. Psychological trauma: Posttraumatic stress disorder and spirituality. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1998;26:168–178. [Google Scholar]

- Wortmann JH, Park CL, Edmondson D. Trauma and PTSD symptoms: Does spiritual struggle mediate the link? Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, And Policy. 2011;3:442–452. doi: 10.1037/a0021413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CC. Evaluating latent class analysis models in qualitative phenotype identification. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis. 2006;50:1090–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Franklin CL, Zimmerman M. Does “subthreshold” posttraumatic stress disorder have any clinical relevance? Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2002;43:413–419. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.35900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]