Abstract

The transmission of malaria across the Arabian Peninsula is governed by the diversity of dominant vectors and extreme aridity. It is likely that where malaria transmission was historically possible it was intense and led to a high disease burden. Here, we review the speed of elimination, approaches taken, define the shrinking map of risk since 1960 and discuss the threats posed to a malaria-free Arabian Peninsula using the archive material, case data and published works. From as early as the 1940s, attempts were made to eliminate malaria on the peninsula but were met with varying degrees of success through to the 1970s; however, these did result in a shrinking of the margins of malaria transmission across the peninsula. Epidemics in the 1990s galvanised national malaria control programmes to reinvigorate control efforts. Before the launch of the recent global ambition for malaria eradication, countries on the Arabian Peninsula launched a collaborative malaria-free initiative in 2005. This initiative led a further shrinking of the malaria risk map and today locally acquired clinical cases of malaria are reported only in Saudi Arabia and Yemen, with the latter contributing to over 98% of the clinical burden.

1. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

The Arabian Peninsula has a diverse malaria epidemiology and an important historical contribution to the understanding of successes and failures of malaria elimination. Writings from travellers to the Arabian Peninsula during the previous two centuries make reference to periodic fevers and deaths from fever at oases and along the inhospitable Tihama region on the western border with the Red Sea (Rogan, 2011). It is thought that during the Prophet Mohammad’s migration from Mecca to Medina in the year 622, an epidemic of ‘Yethrib’ fever attacked his followers; Yethrib was subsequently named Medina and was regarded as a ‘dangerously unhealthy place’ (Farid, 1956, 1996). The presence of the established human red cell polymorphisms, protective against malaria, such as haemoglobin S and Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase deficiency, across the region suggests a long-term selective pressure through a significant malaria burden (Lehman et al., 1963; Gelpi, 1965; El Hamzi et al., 2011). It is likely that malaria occurred across populated areas of most of the present day territories of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, Oman and Yemen at the turn of the last century, where transmission was limited only in its extent by the availability of breeding sites for dominant vectors and the presence of human hosts.

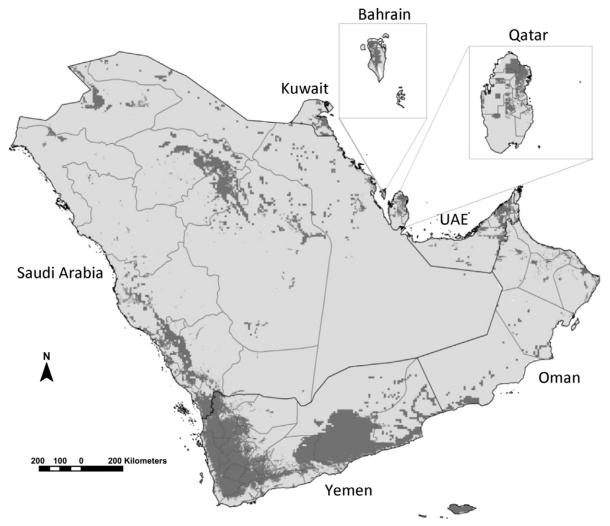

Altitude and deserts have been used to define the absence of malaria transmission in most previous iterations of global malaria maps (Boyd, 1930; Dutta and Dutt, 1978; Lysenko and Semashko, 1968). Ambient temperature determines the likelihood of transmission of human malaria based on its relationship with the duration of sporogony of the parasite in the mosquito. Extreme aridity effects Anopheline development and survival (Shililu et al., 2004). Using recently developed models of temperature suitability based on long-term climate data (Gething et al., 2011) and remotely sensed proxies of extreme aridity (Guerra et al., 2006, 2008), it is possible to distinguish the biological limits of transmission across the peninsula. Low ambient temperatures identify the mountains of Jebel el Nabi Shu’ayb and a spine of high altitude areas around the capitol city of Sana’a in Yemen that probably cannot support transmission of either Plasmodium vivax or Plasmodium falciparum. Aridity limits transmission across the vast deserts of the Rub’ al-Khali or ‘empty quarter’ in Saudi Arabia and bordering territories of UAE and Qatar, the desert coasts of Bahrain, Hadramaut Governorate in the Republic of Yemen and the focal nature of transmission as a result of aridity in northern Oman. The presence of human hosts is important for the continued transmission of the malaria parasite. There are ‘climate-suitable’ areas of the Arabian Peninsula where for decades people have not lived, and these can be identified using long-term human settlement models (Goldewijik et al., 2010). The combined effects of low ambient temperature, aridity and human population density are likely to represent the biologically maximal limits of malaria risk (Fig. 3.1).

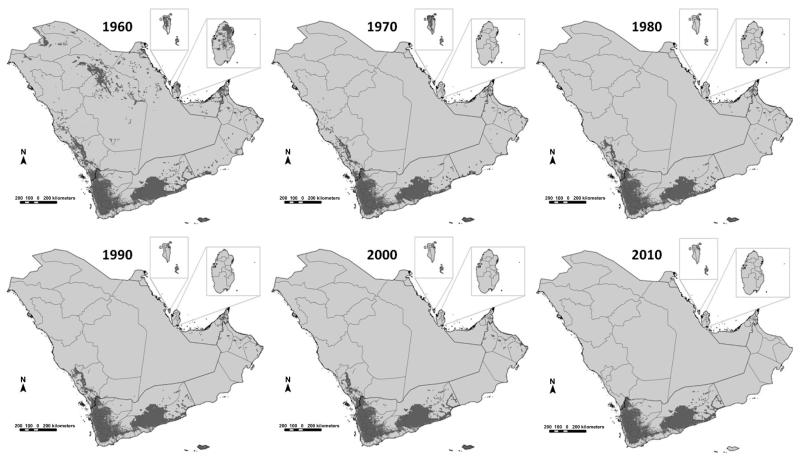

Figure 3.1. Map showing the aridity and temperature masks that do not support malaria transmission (light grey) and areas able to support some degree of stable transmission (dark grey) on the Arabian Peninsula.

Dark lines represent national boundaries; light grey lines represent sub-national provinces or governorates. Areas unsuitable for stable malaria transmission represented in light grey developed from temperature, aridity and population density masks. A temperature suitability index was used to provide a means to exclude the possibilities of transmission based on the average vector’s life-span, monthly ambient temperature and the duration of sporogony (Gething et al., 2011). For extreme aridity, the enhanced vegetation index (EVI) from 12 monthly surfaces has been used in previous global malaria risk maps to classify into areas unlikely to support transmission, areas without two or more consecutive months of an EVI >0.1 (Guerra et al., 2006; Guerra et al., 2008). The history database of the global environment (HYDE) population dataset provides a modelled projection of population distributions and densities at a 9 km × 9 km resolution for every decade (Goldewijik et al., 2010). The HYDE dataset uses national and sub-national population numbers from multiple, time-series sources and every historical source adjusted to match the current sub-national boundaries. Here, we have used a mask to identify those areas in 2000 with population density less than 1 person per 100 km2. These biological receptive limits are adjusted according to temporal information on elimination status, medical intelligence and reported case data for the years 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 and 2010, as shown in Fig. 3.10.

The sub-region encompasses three eco-epidemiological zones of malaria (palaearctic, oriental and afrotropical) lending itself to large variation in vectors and parasite transmissions. The distribution of malaria vectors across the Arabian Peninsula is complex and one of the main drivers of variations in the transmission intensity and the success of control within and between countries (Zahar, 1974; Beljaev, 2002; EMRO, 1990). Some of the earliest descriptions of vector-species distribution across the region come from Buxton (1944), and since then many authors have investigated the presence of Anopheline species across the peninsula as part of detailed epidemiological investigations (Sinka et al., 2010) or as a primary function of control activities (Zahar, 1974). Primary malaria vectors include Anopheles sergentii, Anopheles stephensi, Anopheles arabiensis, Anopheles superpictus and Anopheles culicifacies; less important roles are played by ‘secondary’ vectors including Anopheles claviger, Anopheles d’thali, Anopheles fluviatilis and Anopheles pulcherrimus. Of the dominant vectors An. sergentii is the most ubiquitous across the region and referred to as the ‘desert malaria vector’. It makes use of a range of larval habitats, including streams, oases, date palm groves, irrigation channels, springs, rice fields, and found in moderately brackish habitats. Anopheles stephensi is located on the eastern side of the peninsula along the Gulf of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, UAE and Oman. In Oman and UAE, the secondary vector associated with An. stephensi distributions is mainly An. culicifacies except in two regions of Oman: Dhofar (An. sergentii) and Musandam (An. fluviatilis). Anopheles stephensi breeds in various artificial containers in homes and collections of water associated with construction sites and other industrial developments. In rural areas, An. stephensi larvae utilise fresh water pools, stream margins and stream beds, catch basins, seepage canals, wells and domestic water storage containers. Anopheles arabiensis is located in the west along the Red Sea coast extending from Aden in Yemen to Mecca in Saudi Arabia. Anopheles arabiensis larval habitats are generally small, temporary, sunlit fresh water environments. Anopheles superpictus is found only in the northern territories of Saudi Arabia bordering Iraq and easily adapts to human-influenced habitats making use of irrigation channels and storage tanks and pools formed from their leakage, rice fields, ditches and construction sites; it is generally a zoophilic species but opportunistic in its feeding habits. Anopheles culicifacies is a complex of species within the Funestus group, highly zoophilic and found in Oman, UAE, Yemen and Bahrain. Larval habitats include irrigated canals, stream margins, borrow pits, ponds, domestic wells, tanks and gutters.

Territories across the Arabian Peninsula before the Second World War, despite rich culturally significant civilisations, were some of the economically poorest in the world. Most countries had no functioning road networks, infrastructure or health care system. The discovery of oil transformed the region within a few decades into a region of rapidly growing economies able to change their nations into modern societies with a significant global political influence. By the late 1970s, most countries were able to expand free medical care and education to their predominantly young populations and rapidly develop cities and commercial centres resulting in some of the highest rates of urbanisation worldwide. This economic growth and requirements for labour brought an influx of foreign nationals to meet the needs in the oil and gas industries, construction and support services.

There were limited efforts to control malaria before the Second World War in the region and largely managed by the colonial medical authorities in southern Yemen and Bahrain. The exploration and extraction of oil in Saudi Arabia in the 1940s highlighted the economic impact on the labour force posed by malaria around oases and signalled the beginnings of aggressive attempts to eliminate malaria. Malaria elimination began in various parts of the peninsula from the 1960s and was met with varying degrees of success over the next 40 years. In 2007, the international community reasserted a commitment to global malaria eradication (BMGF, 2007; RBM, 2008) by iteratively shrinking the malaria map (Feachem et al., 2010a,b). Before the launch of the global business plan for control and elimination, the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office of the World Health Organization (EMRO) introduced the concept of a ‘malaria-free Arabian Peninsula’ in 2005 (EMRO, 2007; Atta and Zamani, 2009), which was endorsed in 2006 at a meeting of Health Ministers of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) States (Atta, 2006; Meleigy, 2007).

Here we present a review of the historical distribution and control of malaria, pre-1960 to the present day. The review provides an insight into the context and challenges of malaria elimination and the future threats posed for the realisation of a malaria-free Arabian Peninsula.

2. KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA

The Kingdom was established in 1932 and until the discovery of oil in 1941 was one of the poorest countries in the world. Oil now accounts for more than 90% of exports and 75% of government revenue that supports a free welfare state for its nationals and immigrant labour force including all funding for domestic malaria control and support for control activities in neighbouring countries.

In 1935, malaria accounted for 45% of all out-patient attendances in Jeddah (Buxton, 1944). It was not until 1947 that attempts were made to document infection prevalence at Qatif and Al-Hassa oases on the Gulf coast and smaller surveys in the interior at Yabrin and Al-Kharj, south of Riyadh (Daggy, 1959). This area supports breeding sites for An. sergentii and An. stephensi and is separated from the Najd interior by the Dahna sand dunes. Oil exploration by the Arabian–American Oil Company began in 1938 and malaria presented a major public health threat to the 13,000 Saudi employees. An estimated clinical attack rate was reported of 160 per 1000 population per year between 1941 and 1947, with almost equivalent contributions of P. vivax and P. falciparum. Malaria was also the cause of approximately 12% of all deaths among the Saudi employee population. The surveys at the Qatif and Al-Hassa oases showed parasite rates among children aged 0–14 years between 14% and 100% (Daggy, 1959). In 1948, aggressive efforts to control malaria were mounted in this area using annual indoor residual spraying (IRS) with dichloro-diphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and continued through to 1955 when deildrin replaced DDT, prompted by a rise in case incidence and suspected DDT resistance. By 1957, cases of clinical malaria among the employee population had declined considerably; from over 2000 clinical cases in 1947 to 54 cases by 1957, 88% of cases being P. vivax. The success of the programme was measured using annualised infant and childhood parasite rates; by 1956, infant parasite rates were zero (Daggy, 1959). The Qatif area became a demonstration area for further malaria control training from 1966.

The success of the Qatif malaria-elimination effort led to the establishment of the Malaria Control Service (MCS) in 1956. In collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO), the MCS launched a pre-eradication programme in 1963 and delineated the country into preparatory, attack, consolidation and preoperational areas (Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 1963). Over the next 10 years, the programme began systematically reducing the foci of risks in the eastern and central regions of the country through IRS using DDT and dieldrin. During the 1960s, locally acquired malaria cases continued to be reported at Qatif; there were 35 cases in 1964, but rose to between 54 and 231 cases between 1965 and 1969 and declined to only 30 and 12 cases in 1970 and 1971 respectively; the last foci being Awwamiyah. There were no autochthonous cases from 1972 at Qatif and none from Al-Hassa from 1973 (Sebai, 1988; Jalal and Lin, 1972). Resistance to both DDT and dieldrin prompted a change in attack methods that increasingly included larval control with Paris Green (copper acetoarsenite) and mass drug administration using chloroquine (Anon, 1984; Amara, 1988) at the other oases and coastal towns of the eastern province. In this region, malaria declined significantly, and transmission was largely interrupted by 1975, despite a continued threat posed by rising numbers of imported cases and the continued presence of the vector (Sebai, 1988; Al Tawfiq, 2006).

There is some reference to parasitological surveys undertaken in the northern provinces during the 1950s, an area where transmission is supported by An. superpictus. Infant parasite surveys at Qurayat (1957) and Al Jouf (1958) showed infection rates of 6 and 12% respectively (Amara, 1988). From 1965, larviciding, first with Paris Green and then temephos, began at Al Jouf, Sikakaand and Qurayat. DDT IRS was introduced later, and by 1971 malaria was reduced significantly through widescale active-case detection and mass-drug administration in all northern regions and areas bordering Jordan and Iraq. The vector was thought to have been eliminated in this region and the parasite reservoir removed. However, in August 1982 An. superpictus reappeared at Doumat Al-Jandal Oasis in the Jouf area but aggressive larviciding and case-detection ensured that no local transmission occurred by 1984 (Anon, 1984).

By the mid-1970s, the principal risk areas remained along the Red Sea coast from the north to the southern borders with Yemen. In these regions, the dominant vectors were An. sergentii in the north and An. arabiensis along the southern Red Sea coastal areas. In the north western region, threats of malaria had always posed a public health risk to pilgrims on the Hajj (Farid, 1956). Between March 1950 and February 1951, the hospital at Medina treated 4876 clinical malaria events and reported 343 deaths from malaria (Farid, 1956). From the 1950s, the control of malaria in Medina and Khayber (1957) followed by Mecca and Jeddah (early 1960s) was mounted to protect the pilgrimage routes travelled by Hajjis. Larviciding in urban areas and IRS with DDT in households located in rural areas gradually increased in the scope and coverage; in 1971, temephos was introduced to replace Paris Green as the larvicide, and DDT was stopped as it had failed to interrupt transmission in Khayber and Medina (Amara, 1988). Malaria control was largely successful in the northern areas of the Red Sea coast and was finally supported with active, epidemiological case surveillance to identify the last foci in the most northerly reaches. However, residual foci persisted and proved harder to control in the lower reaches of the Hijaz Mountains, where An. sergentii maintained transmission and the persistent An. arabiensis foci in the foothills of Mecca (Magzoub, 1980; Sebai, 1988). In 1984–1985, a cross-sectional survey among 3834 children at 18 primary schools in the Mecca region found 2.1% infected with malaria, 90% due to P. falciparum (Hammouda et al., 1986), and throughout the early 1980s, malaria continued to be a cause of severe, life-threatening hospital admissions near Mecca (El Sebai and Makled, 1987).

By the mid-1970s, the Kingdom had successfully eliminated transmission from the oil-rich areas of the east, where competence of dominant vectors for transmission was lowest and the risks from transmission across borders was minimal (north east). Nevertheless in 1974, it was recognised that eradication of malaria across the country was not immediately feasible, largely due to the entrenched active transmission areas of the south western regions bordering Yemen and the Red Sea coast, areas dominated by An. arabiensis (Abdoon and Alshahrani, 2003; Al-Sheikh, 2004; Al Zahrani, 2007). In consultation with the WHO, the national malaria programme changed from a ‘pre-eradication’ to a ‘control’ programme based on clearly defined epidemiological annual targets (Amara, 1988). The first attempts at malaria control in the Asir region began with successful DDT house-spraying at Wadi Najran in 1954 and showed a reduction in infant parasite rates from 43% to 0% by 1955 (Chuang, 1986). The DDT programme extended to Wadi Habouna, Wadi Tathleeth, Wadi Bisha and Wadi Tabala and successfully reduced infant parasite rates by the late 1950s in this low lying valley to below 1% (Chuang, 1986). In 1974, a malaria station was established at Abha covering the eastern and western slopes of the Asir Mountains to support reconnaissance of breeding sites in the low lying areas of this region. Between 1973 and 1976, IRS with DDT began in some areas of Jizan, Al Lith, Mohayil and Bisha; however, lack of human resources meant that coverage was poor (Amara, 1988). The National Malaria Control (NMC) established a malaria station in Qunfudha in 1980 and a national malaria training centre in Jizan in 1981, supporting eight malaria reconnaissance centres along the Tihama straits from 1983. Since the mid-1980s, an optimistic vector control programme was mounted in this region using annual DDT residual house spraying in areas of hyper-endemicity and larviciding with temephos in persistent foci covering 791 villages in Jizan, and approximately 70 villages in Mohayil, Qunfudha, Al Lith and Abha (Malaria Control Service-MoH, 1986). At Shuqayri in Jizan, between 1982 and 1983, combined vector control approaches were found most effective, with infant parasite rates declining from 8%-11% under single rounds of DDT to less than 1% when IRS was combined with weekly temephos larviciding (Anon, 1984). In addition, Ultra-Low Volume (ULV) spraying was undertaken using the pyrethroid Reslin in some selected persistent foci in the mid-1980s (Anon, 1986). In the southern region, DDT resistance, identified in 1986, hampered vector control and was replaced for IRS with fenitrothion in 1987 (Amara, 1988). From the mid-1980s, the main attack tools appear to have been weekly larviciding with temephos and some success was evident with a reduction in P. falciparum prevalence from 36% (1977) to 7% (1987) reported during annual mass blood surveys (Amara, 1988).

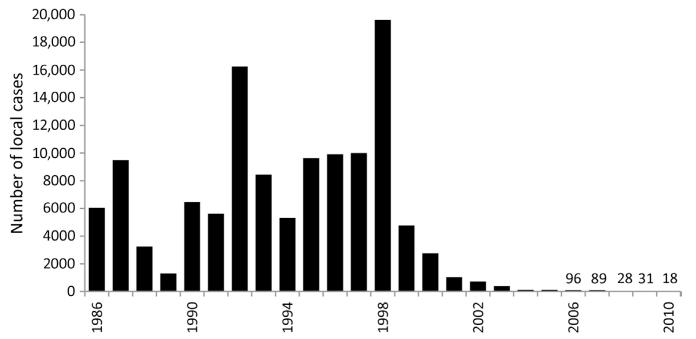

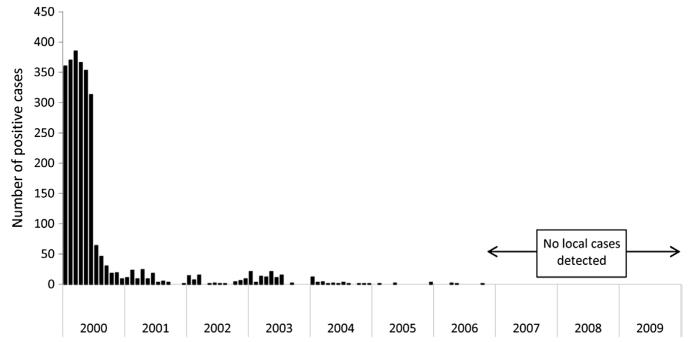

Contrasting the successes in the rest of the country, malaria control efforts in the southern region had never achieved a sustained interruption of transmission. The highest risks between 1980 and the early 1990s have included focal areas in Qunfudha and Al Lith sectors of Mecca Province, Asir in the southern region and the most intense transmission covering much of Jizan Province (Farid, 1992). The 1990s were a period when intervention efficacies were failing, intervention coverage declining and a time of increased domestic threats posed by terrorism. From 1990, malaria control remained a vertical programme under the directorate of the MCS with the aim of maintaining the malaria-free areas safe from local transmission, combat outbreaks early and reduce disease incidence in highly endemic areas. During the 1990s, attempts were made to integrate case management within an expanded Primary Health Care (PHC) scheme. Chloroquine-resistant case reports began to emerge in the early 1990s (Kinsara et al., 1997; Malik et al., 1997) with documented treatment failure rates of 12% in Jizan by 1998 (Ghalib et al., 2001). Overall, the attention given to malaria control waned. Despite earlier successes in reducing case incidence in the south during the early 1980s, malaria began to rise in the 1990s and resulted in a series of epidemic outbreaks in 1992, 1996 and 1998 mainly in Jizan and Asir. Within one area of Al Baha, a serious epidemic led to over 400 P. falciparum cases in a few months in 1996 (Al Abdullalatif et al., 1996). From 1986 to 1998, locally acquired malaria cases began to increase in Jizan Province (Fig. 3.2). The epidemics between 1992 and 1998 affected Jizan, and the epidemiology during these ‘wet years’ changed leading to rising infection risks. The biggest malaria threats in Jizan exist along the border with Yemen, and this was seen in 1994 as a major challenge to the future malaria status of the province given the lack of control activities on the Yemeni side (Anon, 1994). The border was porous; in 1985, more than 15% of detected malaria cases were among the Yemenis and their follow-up and radical treatment was incomplete (Chuang, 1986). In 2003, more than 70% of total national case burden occurred in the southern region (mainly Jizan and Asir), of which about 90% of cases were caused by P. falciparum.

Figure 3.2. Locally acquired, slide-confirmed cases of malaria in Jizan province 1986–2010.

(Data provided in Anon, 1994 and by Dr Ahmed Sahli)

The 1998 epidemic resulted in 31,925 local cases of which 61% were detected in Jizan. This epidemic served to strengthen control efforts and led to the adoption of the Roll Back Malaria (RBM) initiative as part of a regional consultation that included stronger intersectoral collaboration, partnerships and cross-border collaborations. As a result of political commitment, local support and a general development (infrastructure, housing and electricity), the number of malaria cases significantly decreased in the southern provinces. An interesting development was the integration of vector control approaches in 2000 including surveillance and response to Rift Valley Fever, which was contained through the intersectoral collaboration between the Agriculture Department and Malaria Control Programme, and resulted in collateral benefits through an abrupt fall in malaria incidence (Al-Seghayer and Alattas, 2005). In 2003 Saudi Arabia re-expressed its elimination ambitions.

The objectives of the National Malaria Strategy 2004–2007 were laid out to re-establish a pathway to pre-elimination with a concentrated effort in the Southern region and enhanced surveillance in other previously controlled areas to sustain a malaria-free state. The elimination strategy emphasises strengthened case management, including the provision of free artemisinin-based combination therapy to all locally acquired and imported cases; improved, quality-assured laboratory confirmation of all cases, vector control (IRS, insecticide-treated nets and space spraying when required), enhanced geographical information system (GIS) of breeding sites to support larviciding, improved surveillance (with active detection and epidemiological investigation of all cases) and special emphasis on the threats posed by cross border movement from Yemen with biannual meetings to plan and monitor the border coordination activities. Political commitment remains high with the King and important members of the Saudi government involved in promoting the strategy and a provision of US$ 30 million per year to the ambitions laid out in the strategy. The objectives were specifically to prevent reintroduction of local transmission in areas where it had been interrupted (eastern, northern and central regions); reduce the number of indigenous cases by 50% between 2005 and 2007 and subsequently by 100% by 2010; thereafter mount a maintenance phase to ensure that the country remains malaria-free (Kondrachine, 2004). In 2001, the National Malaria Control Programme in Yemen was re-established and a collaborative programme to control cross-border malaria was resurrected and revised since it was first established in 1979. An agreement to support efforts for a malaria-free Arabian Peninsula was signed by Ministers from both countries and a cross-border initiative was launched in 2007 (Meleigy, 2007). Cross-border activities included sharing plans, information, spraying activities within a 10 km range of the border in Yemen, within and establishing 22 border ‘malaria posts’ offering free screening and treatment. It was estimated that these activities would target approximately 3,000 border migrants per day; however, the illegal migrants continue to pose a significant contribution to transmission as they remain undetected and are often semi-immune therefore do not seek treatment.

Malaria-elimination interventions intensified between 2007 and 2009; over 0.5 million long-lasting insecticide treated nets (ITN) were distributed in the southern region; detailed mapping and reconnaissance of larval breeding sites served to supported temephos larviciding; and passive, active and case investigation formed the basis of treating infected people and their contacts. Following the escalation of falciparum chloroquine resistance (Kinsara et al., 1997; Ghalib et al., 2001), it was replaced as a first-line treatment in 2007 with the ACT artesunate-sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine and artemether-lumefanthrine was reserved for a second-line treatment. Chloroquine plus primaquine continued to be used for radical treatment of P. vivax malaria. During the second phase of the strategy (2007–2010), the specific goal was to “…reduce malaria incidence to the level of less 0.5 per 100 000 people, or about 100–120 indigenous cases annually, reported in the residual active foci only.” A plan was envisaged to develop an “inventory of malaria foci, identification of their epidemiological status, selection and application of measures and evaluation. For monitoring the status of foci, it will be absolutely essential that every case of malaria detected should be epidemiologically classified. The outcome of epidemiological classification of cases will serve as a basis for identification of the type of malaria focus” (Kondrachine, 2004). The Kingdom was then classified by the WHO as a country “with focal transmission and targeting elimination” (EMRO, 2007).

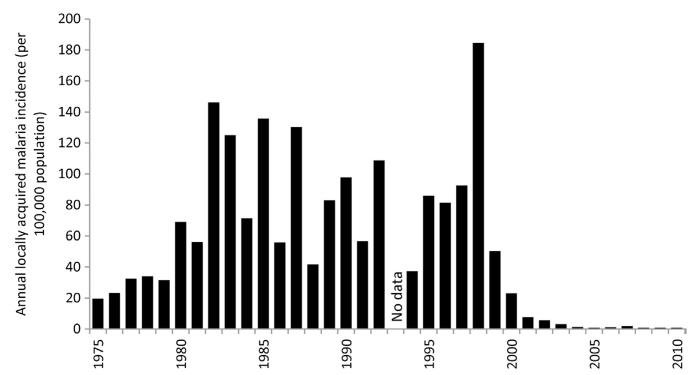

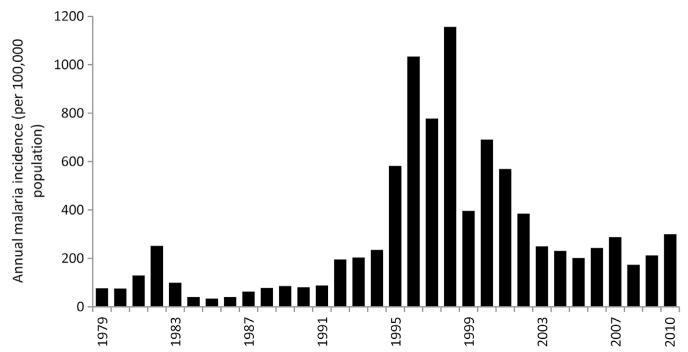

By 2005, there were no reported local cases from Al Baha and Taif regions and only four active transmission foci in Asir resulting in 13 locally acquired cases during that year, four local cases were reported in Qunfudha from three active foci of transmission, local transmission was identified at only two foci at Wadi Al Furra, outside city limits of Medina that resulted in six cases. In 2005, the majority of residual transmission foci (66) were located in Jizan and led to 125 locally acquired cases (Kondrachine, 2006). By 2010, only 29 locally acquired cases were detected in the Kingdom with 11 from Asir and 18 from Jizan (Al Zahrani, 2010). In 2010, there were however 1912 imported cases across the Kingdom, 30% were from Yemen. The changing annual incidence of autochthonous malaria cases in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia between 1970 and 2010 is shown in Fig. 3.3.

Figure 3.3. Annual incidence of slide-confirmed, locally acquired malaria cases between 1979 and 2010 in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia per 100,000 population per annum.

Reports of slide-confirmed, locally acquired cases used for 1975–1979 (Malaria Control Service Ministry of Health, 1980); 1990–2010 EMRO database. Population data have been sourced from several publications: 1992, 2004, 2007 and 2010 (Central Department of Statistics and Information, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2011); 2009 (Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency, 2011). All other years have been estimated using intercensal growth rates.

3. REPUBLIC OF YEMEN

The boundaries of the present day Republic of Yemen have changed subject to regional power struggles over the last 150 years. In 1937, the city of Aden and its surrounding villages was renamed the Colony of Aden and the remaining areas of South Yemen became the British Aden Protectorate (Gavin, 1975). In 1963, the Colony of Aden and Protectorate joined to form the Federation of South Arabia, and in 1967, became the independent country of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) (Dresch, 2000). In 1918, North Yemen was declared independent of the Ottoman Empire. From 1962, civil war ravaged the region until 1972 when North and South Yemen declared they would take steps towards unification, completed in May 1990 as the Republic of Yemen. Today the country is the poorest and least developed of all its neighbours on the peninsula and continues to face civil unrest and conflict.

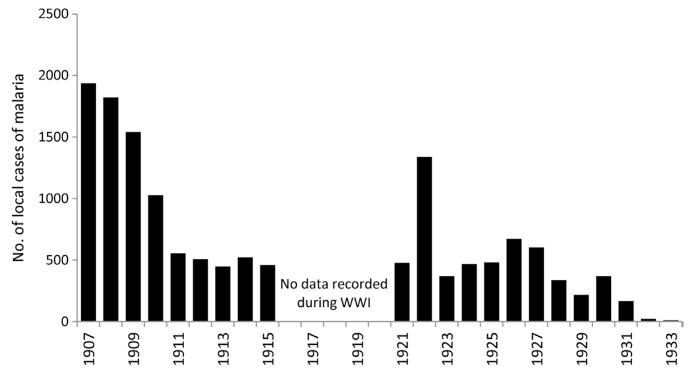

Records of malaria risks are available from the earliest periods following the occupation of Aden by the British. In 1933, Colonel Phipson conducted a medical survey across the Aden Colony and Protectorate discovering that malaria was practically nonexistent around the Aden port and its surrounding villages. Extremely low levels of mosquitoes were detected and the use of bed-nets was thought unnecessary. The few patients that were diagnosed with malaria came from the inland areas of the protectorate and presented with P. falciparum on most occasions (Phipson, 1933; Buxton, 1944). A few kilometres north of the port of Aden at the oasis of Sheikh Othman, malaria was of more serious concern, and cases were regularly documented at the Keith Falconer Mission Hospital (Fig. 3.4). In 1909, Lt. Colonel Wightwick began an antimalarial scheme based on the approaches of environmental management, using kerosene of mapped larval breeding sites advocated by Sir Ronald Ross. There was a protracted period through to the 1940s where water pools in mosques and ponds were sprayed with Gammexane dispersible powder (WHO-Aden, 1956). Malaria re-established itself as a major cause of admission to the renamed Sheikh Othman Hospital in 1943 and spleen rates were recorded among children living at Wadi Milah, Musiemir and Tom el Baha exceeding 75% (Petrie and Seal, 1943). In North Yemen including most of the area from Ta’iz to the Saudi border, some antimalarial measures were implemented prior to 1956; construction of canals, renewal of water in the ponds at mosques, removal of stagnant water, regular aerosol DDT spraying, periodic distribution of quinine at military barracks and schools in Sana’a and Al Hudaydah (WHO-Yemen, 1956).

Figure 3.4. Malaria admissions to Keith Falconer Mission Hospital, Sheikh Othman, Aden 1907–1933 (Phipson, 1933).

At the Mission Hospital, case incidence dropped from over 1900 cases in 1907 to 460 locally acquired cases by 1915 following environmental management and larviciding. During the First World War, the control of malaria was interrupted but resumed in 1922 with increasing success at mapping breeding sites in surrounding villages (including Dar-al-amir, Lahej and Halwan) and cases reported at the mission hospital declined to very low levels by 1933 (Phipson, 1933).

After the Second World War, the Abyan Cotton Board was established to help improve irrigation across the Abyan district in the Aden Protectorate. During the construction period, high levels of morbidity and mortality were recorded due to malaria amongst labourers, which prompted antimalarial measures to be established between 1949 and 1954. Larviciding using 5% DDT occurred across the entire district operated by a health assistant, 8 spray men, 8 labourers and 8 donkeys. As a result of intense larviciding, malaria transmission was reportedly interrupted; however, the entire scheme cost US$ 28,000 a year. To make it more cost-effective, in 1954, the programme changed to residual spraying with the organochloride benzene hexachloride in all houses in the district four times a year. Due to lack of insecticide, spraying was rarely completed by 1961. An increase in malaria cases was observed after the control was stopped (Colbourne and Smith, 1964). At this time, the malaria programme lacked skilled leadership, the highest qualified member of 65 staff was a technician and the WHO-trained medical officer left the country.

Prior to 1941, it was believed that Sana’a was malaria-free and that the majority of cases came from the lowlands of the Tihama plains. During the Second World War, cases of malaria in Sana’a remained low, but in June 1946, a malaria outbreak occurred with a sharp rise in the malaria mortality rate (4.3 per 1000 residents); cases were considered local as the majority of cases lived less than 10 km away from the city of Sana’a (Audisio de Marchi and Audisio, 1952). In 1951, a general medical survey was conducted to assess the health and sanitary conditions in the three western regions of Yemeni Arab Republic (YAR): 289 thick and thin films were examined for malaria parasites as part of the survey revealing positivity rates of 28% at Ta’iz (P. falciparum and P. vivax), 2% at Al Hudaydah (P. falciparum and Plasmodium malariae), and 1.5% at Sana’a (P. vivax only) (Mount, 1953).

From the 1970s, the epidemiology of malaria across Yemen was characterised according to topographical criteria (Thuriaux, 1971; Kouznetzov, 1976; Kravchenko, 1978) and loosely linked to a spleen survey of 35,000 people undertaken in the mid-1970s (Kravchenko, 1978) and other parasite prevalence data (Mount, 1953; Thuriaux, 1971; Kravchenko, 1978). These strata continue to be used today (NMCP Yemen, 2006) to define priority control areas and include: the mesoendemic coastal plains, including Tihama, characterised by low rainfall and extensive wadis; foothill regions between 200 and 2000 m above the sea level of hypo-mesoendemicity; the epidemic prone desert areas including Hadramaut Governorate; the dry, mountainous highland plateau (above 2000 m) where large parts are malaria-free (including Sana’a); and Socotra Island that was meso-hyperendemic and a unique separate ecology. In the 1970s, 95% of all infections were due to P. falciparum, 4% due to P. malariae and less than 1% due to P. vivax (Kravchenko, 1978). Plasmodium ovale was conspicuous by its absence in most reports and the first case of P. ovale was detected at Beni-Hussan village, in Bajil district, Al Hudaydah Governorate in 1998 (Al-Maktari and Bassiouny, 1999).

In collaboration with the WHO, the first national malaria control plan was established in 1969 with the PDYR, with a base at Aden. In 1978, a similar plan was established with the YAR that led to the establishment of the Malaria Control Programme (MCP) at Al Hudaydah to support larval control using temephos and IRS using DDT across the Tihama plains, a project jointly supported by WHO, to serve as a pilot project to expand nationally with time (Shidrawi, 1980a). In 1979, health centres and hospitals were encouraged to routinely collect blood slides from febrile outpatients and report to the MCP but institutionalised more rigorously at nine sentinel centres across Al Hudaydah Governorate. Baseline cross-sectional data showed that the Al Hudaydah Governorate was mesoendemic with higher prevalence rates in the foothills near the Ta’iz Governorate, parasite rates ranging from 28% to 38% (Shidrawi, 1980a). The national malaria control plan proposed the expansion of field sites to include six malaria units, 12 malaria posts and three entomology units, including staff and commodity costs; it was estimated that US$ 400,000 would be necessary to implement the plan from the government and WHO funds (MoPH, 1981). However, lack of administrative support, unsatisfactory organisation of a special budget for malaria, delays in salaries and travel expenses led to a halt in the entire programme by the end of 1980 (Shidrawi, 1980a). Between 1978 and 1988, in both the PDRY and YAR, most control activities focussed on attacking larval and adult forms of the vector using larvivorous fish (Aphanius dispar) in wadis across Abyan Governorate (Amini, 1988) and the use of temephos alone or in combination with DDT IRS in the Thiama plains area and foothill regions (Shidrawi, 1980a; Assabri, 1989). In 1989, 30,000 people were protected by DDT IRS (concentrated at Wadi Rima) and 67,000 people were living in areas where temephos was used in wadis (Moar, Toor, Siham, Sardood, Zabid) (MoH Yemen, 1989). Between 1983 and 1988, overall national fever-tested slide positivity remained unchanged (Anon, 1988; Assabri, 1989), although some reductions were noted at the sentinel sites of Zabid and Al Zohra, attributed to IRS and larval control respectively (MoH Yemen, 1989). Towards the end of the 1980s, as part of the third national health plan, malaria became integrated within a programme of PHC, and 722 village health guides were trained to presumptively treat fevers (Delfini, 1986; Anon, 1988).

By 1992, funding for residual spraying and larval control stopped as a direct result of political unrest during this period (Beljaev, 1997). This coincided with the spread of chloroquine resistance, first detected at Al Makatra, Ta’iz Governorate in 1987 (Berga, 1999; Abdel-Hameed, 2003). By 1997, the Republic of Yemen had the highest malaria case burdens of the entire Arabian Peninsula with over 380,000 reported cases (highest incidences in Al Hudaydah, Abyan, Hajjah and Mahwet Governorates) and endemicity levels comparable to large parts of Africa in some areas (Mashaal et al., 1998). In June 1996, unexpected heavy rains led to flooding in several parts of the country, particularly in traditionally arid areas, that resulted in over 24,000 clinical cases and 475 malaria deaths within a few months (Beljaev, 1997). Two years later, the El Nino 1998 epidemic doubled the national slide positivity from previous years, and it was estimated that approximately 1 million cases might have occurred during this year, with a very rough estimate of between 5000 and 10,000 deaths (Souleimanov, 1999). In November 1998, 1175 school children were examined for infection across the Tihama region of Al Hudaydah Governorate, the slide positivity rate was 48% (Mashaal, 1998). The epidemic had one positive consequence – it served to galvanise government action to strengthen the malaria control programme.

In March 2001, the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) was established under the presidential appointment of a Supreme National Malaria Control Committee. The NMCP moved back to Sana’a, from small offices based at Jaar in Abyan Governorate, to take forward a National Malaria Strategic Plan (2001–2005), developed following adoption of the global RBM initiative (NMCP-Yemen, 2001). The government increased its annual budgetary allocation from US$ 0.25 to 2 million at the launch of the strategy; the Global Fund (second round) approved US$ 12 million for 5 years from 2002, and Yemen received additional financial support from some Gulf countries (Saudi Arabia, Oman and UAE). The organisation of malaria control across the country was so dysfunctional that the programme started building the infrastructure and capacity from scratch. The expanded delivery of integrated vector control began in areas of highest risk – the Tihama coast from the Saudi border to Ta’iz, selected districts in foothill and mountain areas and Socotra Island. The control approaches included larviciding with temephos (approximately 400 l used per month in 2002), lambda-cyhalothrin IRS (514 tons used in 2002) and biological control using A. dispar at a small scale in Tihama region and Socotra Island. In 2005, coverage increased to over 40,000 households receiving IRS, 48,000 ITN distributed and 2180 km2 potential breeding sites covered with larvicides (Ali, 2005). By 2002, acceptable clinical responses to chloroquine were only 43–54% at three drug sensitivity-monitoring sites at Bajil, Musemir and Udayn (NMCP Yemen, 2006), and this prompted a transition in November 2005 to artesunate-sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine as a first-line treatment for uncomplicated falciparum cases, supported by a second-line treatment using artemether-lumefantrine (Anon, 2007). There has been no systematic review of the morbidity impact of the increased intervention coverage; however, compared to the November 1998, Tihama plains school malaria infection surveys showing 48% infection prevalence recorded at its maximum post-epidemic peak, school surveys undertaken in Tihama in March 2003 showed prevalence rates of only 7% (NMCP Yemen, 2003).

Socotra Island, with a small population of 43,000 people living on 3650 km2 about 400 km from the Yemeni coastline, had one of the highest recorded transmission intensities in Yemen. Clinical cases transmitted by a single vector (An. culicifacies) presented as both P. falciparum and P. vivax. During the mid-1980s, DDT IRS was deployed on the island but discontinued following recommendations to adopt temephos as an approach to target larval stages in 1989 (Farid, 1988). Control was sporadic and unregulated on this inaccessible island, until 2000. In September 2000, an elimination demonstration project was established using extensive larviciding with temephos across the island, followed in 2002 by IRS spraying using lambda-cyhalothrin (Kondrachine, 2009). No locally acquired cases were reported on the island from 2006 (Fig. 3.5) (EMRO, 2008). Socotra’s success was a boost for the National Malaria Control Programme to initiate those efforts into the mainland.

Figure 3.5. Monthly slide confirmed cases 2000–2010 on Socotra island (Anon, 2009).

According to the census in 2004, Socotra Island had a population of 43,000 people. 50% of the population live in two settlements, Hudaibo and Qalansia. The rest of the population live in scattered villages across three ecological zones: Coastal (0–400 m above sea level), foothills (400–700 m) and hills (above 700 m). Anopheles culicifacies is believed to be the major malaria vector in all geographical areas of the island. In September 2000, the Plan of Action for Malaria Control in Socotra was launched and implemented with funding from the government, Oman, Italy and WHO. Operational personnel included a director, team leaders in operations, supervision, malaria case management and health education, six supervisors and 37 spray-men. Larviciding with temephos across over 5000 mapped breeding sites began in 2001. Over 5000 ITN were distributed between 2002 and 2005. Between 2004 and 2008, 25,000–30,000 people were protected with bi-annual IRS using lambda-cyhalothrin (Kondrachine, 2009).

The second National Malaria Strategic Plan was launched in 2006 to cover the period up to 2010, using similar approaches to control and similar ambitions to the previous five-year strategic plan, reducing 2000 morbidity by 75% by 2010 by sustaining the gains and improving progress towards coverage targets established in 2001. In addition, the 2006 strategy pledged to support the regional vision of a malaria-free Arabian Peninsula by 2015 (NMCP Yemen, 2006) and reaffirmed its commitment to work with Saudi Arabia to control malaria along their borders; an initiative first launched in 1993 (EMRO, 1993) but restarted in February 2004. In 2008, the Global Fund approved US$ 27 million to provide support to the second national strategic plan. During a national household sample survey in 2009, 11% of households had received IRS in the preceding 12 months and 27% of households owned at least one ITN. Overall slide positivity from 12,902 persons sampled was only 1.5% (NMCP Yemen, 2009). Despite the limitations of accuracy and coverage of reporting, the rise and fall of presumed malaria burdens in Yemen since 1979 is shown in Fig. 3.6.

Figure 3.6. Annual presumed malaria case incidence between 1979 and 2010 per 100,000 population per annum across the combined territories that constitute the present day Republic of Yemen.

(Data sourced from Anon (1981), Jamal Amran unpublished data (2006), Anon (2010) and EMRO Database (2012)). No distinction is made in the available reports between locally acquired/imported infections nor is it possible to define slide confirmed/presumptively treated for the entire surveillance period, and therefore cases included are regarded as presumed malaria diagnoses. However, by the mid-1980s, it is thought that reported cases were confirmed cases only. From the 1980s onwards, it is not possible to distinguish the slide-confirmed and presumptively treated malaria cases. The national malaria indicator survey in 2009 reported that only 56% of all fevers sought any form of treatment, and therefore it is additionally likely that many fever cases that are malaria go undetected (NMCP Yemen, 2009). Population has been estimated from several projections (Yemen Central Statistics Organization, 2010), combining YAR and PDYR estimates and based on the first census of the Republic in 1994 where nonreported years computed from intercensal growth rates, including pre-1994 census using the intercensal growth rate (2.91%).

The recently launched national strategy (2011–2015) states that by the end of 2015, the burden of the malaria disease in Yemen will be reduced, through the adoption and wide implementation of evidence-based malaria control interventions, to levels that warrant the embarkation of the NMCP on malaria pre-elimination (MoPH and P, 2011). Particular emphasis in the revised strategy is given to establishing a much stronger epidemiological platform to deliver control, including an adapted stratification to guide integrated vector control methods and improving access to treatment, diagnosis and case-reporting in the revised strategy. Consistent with strategic trends in Saudi Arabia over the last decade, Yemen also recognises the need to embrace intersectoral collaboration, strengthen partnerships and sustain cross-border collaborations to achieve its ambitions by 2015.

4. SULTANATE OF OMAN

The Sultanate of Oman is characterised by a large desert plain that covers most of central and southern regions of the country interspersed with wadis. Mountain ranges are found along the north (Al Hajar Mountains) and southeast coast, and the country’s main cities are also located at high altitude including the capital city Muscat, Sohar and Sur in the northern mountain regions and Salalah in the south. The peninsula of Musandam is a strategic location on the Strait of Hormuz but separated from the rest of Oman by the UAE. Early Sultans sought to extend their influence along the East African coast as far south as Mozambique, and most notable was the relocation of the Sultan to the Island of Zanzibar (Horton, 1987). Thousands of Omanis today can trace their lineage, and continue to have links with, East Africa. Oil exploration began in 1967 that heralded the country’s modern development, and the Omani economy has been radically transformed over a series of development plans since 1976. Before 1970, there were few asphalt roads and no ministry of health. About 50% of the 2.6 million population lives in Muscat and the Batinah coastal plain northwest of the capital; about 200,000 people live in the Dhofar (southern) region, and about 30,000 live in the remote Musandam Peninsula.

Buxton (1944) cites work by Gill in 1916 who reports that fever was a common debilitating illness among troops stationed at Muscat with admission rates between 100 and 400 cases per 1000 soldiers per month and that the cases were predominantly P. falciparum. Over 90% of infections in the 1970s were a result of P. falciparum; P. vivax and P. malariae were rare and only one case of P. ovale had been documented by 1979 (PHD, MoH, 1979). Parasitological surveys undertaken across Oman during the early 1970s suggest that most of the northern areas were mesoendemic with the highest rates of infection recorded in the Batinah (13% infection prevalence among school children) and the islands (including Masira) and the southern regions were either malaria-free, hypoendemic or had high epidemic potential at wells, oases and wadis (Farid et al., 1973). It seems reasonable therefore to regard Dhofar and the Omani Islands as unstable transmission areas in 1970.

The National Central Malaria Control Section (CMCS) of the Preventative Medicine Department, Ministry of Health, began work in 1970 (PHD, MoH, 1979; MoH, Oman, 2011a). Following a nationwide malaria survey that showed parasite rates between 3% and 49%, a control programme was started in January 1975 with financial assistance from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). By the middle of 1978, 17 malaria units had been established in the northern region and the malaria control staff had increased from 14 to 100. A malaria training centre, to overcome shortages in trained staff, was established in 1979. The principal aim of the first control programme was to target source reduction through biological control with indigenous larvivorous fish (A. dispar) but met with only partial success. The programme moved to larviciding with temephos following the pilot projects along the coastal strip at Seeb and extended from 1977 to 1979 to include Samayel, Bahla, Mudarib, Sohar, Saham, Khasab, Jue, Buraimi, Nizwa, Bahia, Hamia, Qurayat and limited areas in Bani Bou Hassan, Bilad, Bilad Sur and Jalan. A key feature of the vector control programme in Oman was the very detailed mapping of risk areas from aerial photography to guide larval control from early in the programme’s history in 1975 (Zahar et al., 1982). Weekly chloroquine prophylaxis of school children during the months of September to May in highly endemic areas was undertaken in collaboration with the Ministry of Education between 1973 and 1979 (Shidrawi, 1980b; Matta, 1984). This programme was stopped in Muscat in 1980 and in Salalah in 1981. By 1982, in areas protected by DDT, prophylaxis was stopped in part due to fears of emerging resistance, and chloroquine was reserved for use by pregnant women and young children (Matta, 1984).

From 1976, DDT residual spraying was expanded following a trial at Shinas in Batinah Province to areas of Dank and along the Buraimi border area with the UAE (Zahar et al., 1982). Between 1976 and 1992, it was estimated that approximately 0.14 million tons of DDT were used for IRS in Oman (Al-Wahabi and Parvez, 2002). However, the IRS campaign never really reached a maximal coverage; for example in Batinah Province, annual rounds of DDT house spraying declined from 1976, where more than 90% of houses were sprayed, to less than 50% by 1981 (Shidrawi, 1982). DDT resistance was first detected in larvae of An. culicifacies in 1980 (Zahar et al., 1982). The use of DDT was finally stopped and replaced with Fenitothion in 1993, partly because of the technical difficulties in maintaining high coverage (Al-Wahabi and Parvez, 2002) and because of recorded escalating resistance. By 2003, An. culicifacies was resistant to both insecticides (Al-Wahabi et al., 2003).

The programmes in the 1970s and early 1980s had only partial success, largely because of shortages of staff, funding and transport (Shidrawi, 1980b). Summarising the malaria situation in 1981, Zahar and colleagues described most of the northern populated areas as experiencing hypomeso-endemic transmission with the coastal strip of Batinah province having the highest transmission and the southern area of Dhofar province suffered only sporadic outbreaks (Zahar et al., 1982). By 1983, parasite prevalence among school children in the Batinah, Musandam, Buraimi and all other provinces remained between 3% and 10%, at Wadi Jizzi parasite rates were above 10% and overall it was felt that the DDT spraying campaigns had little impact since they started in 1976 (UNDP, 1987).

The malaria action plan covering the period 1981–1985 was managed by a newly formed intersectoral Malaria Control Coordinating Board and the programme largely funded by UNDP and the Cooperative Funds of the Gulf Health Secretariat. This five-year plan focused more on DDT IRS in rural areas supported by the mass drug administration (using chloroquine) provided during spraying times. One single round per year was planned for the coastal area during September/October and for the interior and mountainous areas in February/March. Priority for IRS was given to the border areas with UAE. Temephos larviciding continued in the urban areas and rural suburbs for 8 months a year with the possibility of using larvivorous fish and engineering methods for larval control in priority breeding sites as defined by the CMCS. Drug prophylaxis to school children in rural areas was suspended during this period of control. By 1985, it was hoped that the expansion of malaria control in the Oman Sultanate would result in almost negligible transmission along the borders with UAE and a yearly reduction of 35% in malaria prevalence among school children aged 6–9 years. Notable risks of infection continued through the 1980s along the border with UAE and both countries agreed in the late 1980s to supervise each other’s control efforts and maintain a coordinated effort to eliminate the vector-breeding sites in these areas. This coordinated effort led to only marginal success and cases detected in UAE were often labelled as originating from the Omani side of the border.

The programme was re-evaluated in 1991 and the Ministry of Health launched its programme of Eradication, with the ambition of completely interrupting transmission and eliminating the reservoir of infected cases (MoH Oman, 2011b; Delfini and Abdel-Majeed, 1993; Mashaal, 1998). Malaria was made the only disease in Oman to be treated free of charge (Mashaal, 1998). Special attention was continued to be given to the border areas with the UAE who saw Oman as a threat to their elimination agenda. The revised malaria plan organised the country according to eco-epidemiological criteria and defined coastal, foothills, desert oasis areas, islands and Dhofar to guide its selection of targeted control approaches (Matta, 1984). The first phase began with a technical, administrative and practical feasibility of the programme and a pilot project in Sharquiya region. After the 1991 pilot, the elimination strategy was extended to neighbouring areas of Qurayat in Muscat Governorate in 1992 before extending to Batinah Governorate in 1994 and the programme was extended spatially with time to all of Muscat Governorate (1995), Musandam Governorate (1996) and the Dhahia region (1997).

The programme continued to build its intelligence of risk using detailed geographic reconnaissance based on larval survey mapping and school based infection prevalence surveys. The strategies used as part of the elimination strategy were almost entirely anchored on source reduction using temephos and the passive and active detection of malaria cases. Supplementary vector control measures included imagociding operations, biological, environmental management measures and occasional IRS using lambda-cyhalothrin were implemented as required. All suspected cases were parasitologically diagnosed under a quality assured programme of upgraded laboratory services. Vivax patients were treated with chloroquine and primaquine and imported falciparum cases with a combination of quinine, Fansidar and primaquine. In the last few years, treatment policy for the falciparum cases has changed to artemether-lumefantrine for all imported cases. A policy of chemoprophylaxis was introduced for all travellers to East Africa, where many imported cases from Zanzibar continued to be detected. One of the main pillars of the elimination programme was the combined passive and active surveillance of new cases and case investigation. Passive surveillance included all the 231 peripheral health facilities maintained by the government, an engagement with the over 500 private sector health providers to improve parasitological diagnosis and reporting and a public awareness campaign. Active case detection included screening of all travellers arriving from East Africa at Seeb Airport and the follow-up of all positive cases to screen neighbourhood contacts and periodic school surveys.

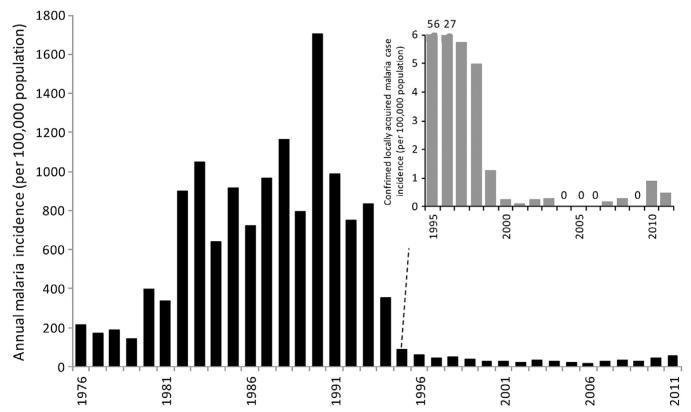

During the late 1980s, it was estimated that there were up to 300,000 clinical malaria cases of malaria each year (MoH Oman, 2011b). Between 1994 and 1999, the annual incidence of locally acquired malaria dropped from 21.5 per 10,000 population to 0.1 per 10,000 population (Fig. 3.7). By 1999, 77% of the population was under an elimination strategy while the remaining areas of the country were under a phase of control; there were no malaria deaths reported, and malaria infection prevalence among school children had declined from 2.2% in 1990 to 0.003% in 1998 (Khalifa, 1999). In 1996, a focal epidemic occurred in Nizwa in Dakhliya affecting 16 children and at Debba in Musandam affecting 10 people (Mashaal, 1998). After 1999, school infection prevalence surveys were suspended in 2000 due to their insensitive nature at very low transmission intensity. By 1999, only 29 of all identified cases were considered local, of which 14 were detected near the Bilad mountainous areas in Musandam province (Mashaal, 2006). By 2000, there were no locally acquired cases (Al Zedjali, 2010). Threats from unregulated, illegal migration continued to challenge the programme, notably in the mountainous areas of North Batinah (Mashaal, 2000). Between 2000 and 2003, a total of 20 cases were detected; between 2004 and 2006, there were no cases. In 2007 and 2008, 4 and 8 autochthonous cases were detected in Dakhliya and North Batinah regions respectively (EMRO, 2010). In 2010 and 2011, 24 and 13 locally acquired cases were identified as part of combined active and passive case detection (Fig. 3.7).

Figure 3.7. Annual locally acquired, slide-confirmed malaria cases both locally acquired and imported in Oman 1976–2011 per 100,000 resident populations; insert shows only locally acquired notified case incidence 1995–2011.

Before 1994, malaria was not a notifiable disease and imported versus locally acquired cases were not distinguished. The graph shows all slide-confirmed cases of malaria detected in the Sultanate of Oman between 1976 and 2011 as dark bars. Various authors and reports have assembled estimates of locally acquired slide-positivity rates from clinic records before 1994 including the periods 1976–1979 (Zahar et al., 1982), 1980–1985 (EMRO, 1987), 1986–1988 (WHO, 1989) and data 1988–1993 from the Omani MoH Statistics office (MoH Oman, 2009). Data for the period 1994–2011 are from the EMRO database. The insert is from 1995 to 2011 showing the incidence of only locally acquired cases all foci rapidly identified and EMRO regard Oman as malaria-free today. Population has been sourced from several publications: 1993–2002, 2004 and 2006–2010 (Sultanate of Oman Ministry of National Economy, 2012); 2003 (MoH, Oman, 2003) and 2011 (UN population projections, 2011). All population estimates prior to 1993 have been calculated using intercensal growth rates.

There continues to be outbreaks of locally acquired cases following importation since 2007 and the challenge has been to maintain strong surveillance for early detection and treatment of all cases – proper timely epidemiological investigation of cases and foci especially with increasing vulnerability. While receptive risks have probably reduced substantially by targeting vector larval sites rather than reducing adult vectors, vectors continue to be identified, and vigilant larval control is necessary to protect against the highly vulnerable nature of imported infections from East Africa and the Indian sub-continent. Almost 30% of Oman’s population today comprise foreign nationals. Monitoring of breeding sites and their management with temephos remain a priority. There was no documented evidence of temephos resistance by 2006, but reduced mortalities (80%) were observed in bioassays of An. stephensi larvae in Dhahira in 2010. Recommendations have been made to begin using biological agents such as Bacillus thuringiensis (Andreason, 2006). Figure 3.7 shows the declining incidence of locally acquired cases in the Sultanate of Oman since 1994 when epidemiological investigations of reported cases distinguished between imported and local infections. Given the sporadic nature of new cases over the last 10 years, all rapidly contained, EMRO considers Oman ostensibly malaria-free today.

5. UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

UAE has approximately 200 small islands in the Gulf and a sea border of 650 km that encompasses coastal salt flats (‘sabkha’). Approximately 80% of the country is desert merging with the Rub’ al-Khali of Saudi Arabia; however, there are oases, notably the large oasis settlements at Al Ain, Liwa and several others towards the borders of Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Fertile plains are fed by mountain ranges in Ras Al-Khaimah Emirate. The sea and the desert provide natural barriers to malaria transmission in the UAE. Oil was discovered in the early 1960s and revenues were used to accelerate development. In 1971, the Trucial States became the UAE and today is constitutionally run by a federation of seven emirates: Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Dubai, Fujeirah, Ras Al-Khaimah, Shariqah, and Umm Al-Quwain. Abu Dhabi is the largest of the seven emirates, and Abu Dhabi City is the capital of the UAE.

During the early 1970s, the country was divided into two main epidemiological strata (Farid, 1977). The first stratum was the highly endemic areas, including the emirates of Ras Al-Khaimah, Shariqah, Fujeirah, the east along the Omani border and the central plateau. Across Fujeirah, in April 1969, P. falciparum parasite rates among children were 43% and 12% for P. vivax; at Shariqah corresponding figures were 26% P. falciparum and 14% P. vivax; and across Ras Al-Khaimah prevalence was 12% P. falciparum and 4% P. vivax (Zahar, 1969). The dominant vector reported for this stratum was Anopheles culicifaces (Farid, 1977). The second dominant stratum was the low-risk region encompassing the coastal strip from Abu Dhabi to Umm Al Quwain and Ajman and included the oasis areas of Al Ain where, in 1977, spleen rates among school children were 6% and the dominant vector was An. stephensi (Farid, 1977). The rapidly growing economy in the 1970s led to major construction works requiring imported labour from the Indian sub-continent that transformed the epidemiological risks, including increased transmission of P. vivax (Farid, 1977).

Malaria control began across the emirates in 1970. Annual rounds of DDT spraying were mounted at labour camps, space spraying in densely populated areas or near breeding sites and fortnightly temephos larviciding across all rural areas. Occasionally, the school health department distributed chloroquine as part of mass drug administration, as practised in areas within neighbouring Oman, but this was not coordinated with the malaria service and little information is available on the extent of this practice. An attempt to devolve control responsibility to district levels in 1975 did not provide harmonised and complete coverage, DDT was stopped during this year and a lack of central leadership meant that drugs, insecticides and supporting commodities were not ordered; peripheral malaria staff then undertook other non-malaria activities. The parasitological diagnosis of malaria was incomplete and inadequate at most peripheral health facilities and there was no functioning health information system by 1976 that hampered effective malaria planning (Farid, 1977). A series of malaria epidemics were reported between 1975 and 1977 and prompted the re-establishment of the Central Malaria Department (CMD) in 1977.

Between 1977 and 1984, DDT IRS was the mainstay of malaria control as part of a vertical programme to reduce malaria risk in the high-risk strata, complimented with larviciding and reports of ULV space spraying with neopyburthrin in urban areas of focal risk. The programme was directed to cover operational zones under the leadership of a federal, vertical programme that received 1.2% of the national health budget in 1979 equivalent to US$ 300,000 (Farid, 1981). By 1979, a system of malaria reporting had been introduced that assisted in planning the control programme, although it was recognised that the reported cases were likely to be less than the actual cases (Farid, 1981). In addition, entomological mapping, surveillance and a census of construction sites helped guide intervention. By 1980, the number of malaria cases had declined; Al Ain, Dubai and Abu Dhabi were reported as malaria-free without any vectors; however, resistant foci continued to pose a problem for control in Ras Al-Khaimah and along the Omani border at Debba where communities refused larviciding (Farid, 1981). Meetings between the malaria programmes of the Sultanate of Oman and UAE were held twice a year to coordinate activities in this area. From 1984, IRS was gradually replaced, following detection of DDT resistance, by the detection of vector-breeding sites and their weekly or fortnightly treatment with temephos, including later with larvivorous fish (A. dispar and Tilapia), and improved surveillance. By 1987, the malaria funding provided from the federal health budget increased to US$ 2.5 million.

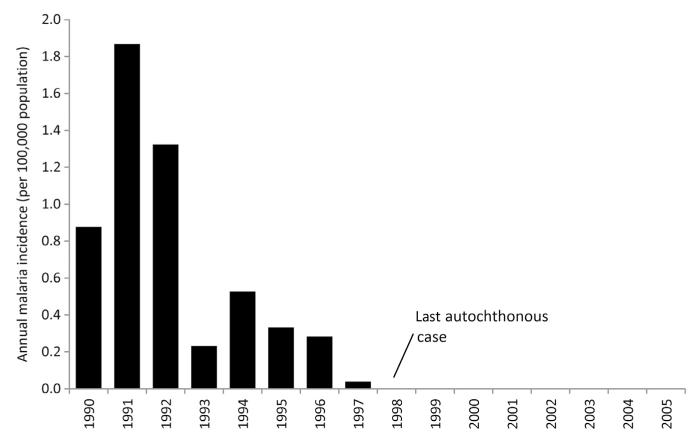

In 1990, a more intensive case-register surveillance system was introduced combining active and passive-case detections, treatment of confirmed malaria cases, epidemiological investigation of cases and foci, and posttreatment follow-up of the malaria cases. Active case detection was gradually phased out as comprehensive health facility coverage across the country became established. The proportion of cases originating from autochthonous malaria transmission in 1990 was 0.46% but declined to 0.04% by 1997. The last autochthonous case of vivax malaria was recorded at Mas-foot in the Central Plateau, in 1997 (Kondrachine, 2001; MoH-UAE, 2002, 2007; Fikiri, 2010; Wernsdorfer, 2004; Fig. 3.8). Despite the heavy rainfall in 1998 and 2004 across the receptive central plateau region, no local transmission occurred. In 1998, the national malaria plan was redesigned from the one supporting control to elimination, and within a few years the CMD staff across the country was 240 full-time employees with 47 based at the headquarters in Sharjah.

Figure 3.8. Annual, locally acquired case incidence per 100,000 population in the United Arab Emirates 1990–2005.

Locally acquired case data provided by MoH-UAE (2002). The last case of locally acquired malaria was vivax and reported in 1997. UAE was certified malaria-free in 2007. Annual population estimates derived from UAE National Bureau of Statistics (2006) and all noncensus years have been estimated using intercensal growth rates.

UAE managed to escape the threats posed by chloroquine resistance elsewhere, and given the increasing numbers of P. vivax cases from India, Bangladesh and Pakistan continued to use chloroquine and the 14-day treatment regimen primaquine from 1990s. In 2006, the drug policy changed to support the use of artemether-lumefanthine for uncomplicated falciparum imported malaria cases, in-line with regional policy, while chloroquine and primaquine continued to be used for vivax cases.

Strategies to maintain the malaria-free status in the UAE from 1999 included surveillance at clinics runs by both the public and private sectors, detailed case investigation, traveller advisory awareness on the need for prompt fever investigation, vector-breeding surveillance including a detailed GIS reconnaissance, continued use of temephos and larvivorous fish, the monitoring of insecticide resistance and high profile, politically supported malaria-free awareness days on 28 December. A request for the certification of malaria-free status in the UAE was submitted in 2002. There followed three review visits by the WHO, which included a review of records, programme efficiencies (including the ability to detect all cases) and other supporting data. This official approach for certification stimulated a renaissance in the certification process for the WHO.

On 27 March 2007, UAE was declared malaria-free, with a cautionary note that while UAE had managed to reduce its receptivity of local transmission, by targeting the larval stages of the vector and rapid urbanisation, vectors had not been eliminated and combined with high vulnerability risks from imported infections meant that the CMD needed to remain vigilant. In 2010, there were 3239 imported infections of which 85% were P. vivax and 90% originated from Pakistan and India. A framework was proposed for the postelimination phase including continued notification of all imported cases, free diagnosis and treatment (including prophylaxis for travellers outside of UAE), toll-free help lines, case and breeding site epidemiological investigations and sustained public awareness campaigns. It was also recommended that the CMD be incorporated within a wider vector control department (MoH-UAE, 2007).

6. KINGDOM OF BAHRAIN

Bahrain is an archipelago of 33 islands, with the largest island of Bahrain Island being only 652 km2 where over 90% of the land mass is a low lying desert, with a single mountain, Jabal ad Dukhan, rising to 134 m above sea level. Bahrain Island is connected to Saudi Arabia by the King Fahd Causeway. Muharraq Island is much more barren and smaller in size and the only fresh water supply comes from the Zimma Spring near Hidd village. After protracted periods of international disagreement and national unrest, the Emirate of Bahrain became a self-governed nation state in 1970. The oil boom of the 1970s led to rapid financial prosperity and a period of diversification of its economy into offshore banking facilities. In 2002, Bahrain changed its name from the State of Bahrain to the Kingdom of Bahrain with five Governorates, Capital, Central, Muharraq, Northern and Southern. In 2010, Bahrain had 1.2 million residents, including 517,000 foreign nationals, the largest majority (290,000) from India.

Malaria is likely to have existed on the islands for hundreds of years. Belgrave (1935) wrote that in 1529, 400 Portuguese men stationed at Manama Fort suffered from an epidemic of fevers. Harrison (1924), writing about his experiences while practising at Manama Hospital, refers to the area as “full of fever, all along the coast the efficiency of the population is reduced by malaria to a mere fraction of what it ought to be”. Data on malaria cases between 1920 and 1937 presenting to the Victoria Memorial Hospital at Manama were assembled as part of a detailed malaria survey across Bahrain by the Malaria Institute of India, indicating at least 1000 cases per year up to 1927 when cases began to rise to over 3000 by 1937 (Afridi and Majid, 1938). The malaria survey identified An. stephensi as the dominant vector followed by Anopheles fluvatilis, An. culicifacies, An. pulcherrimus and An. sergentii. Among 249 school children sampled for parasitology, 4% were positive for P. falciparum, 4% were positive for P. malariae and 5% for P. vivax (Afridi and Majid, 1938). In 1938, recommendations were made by the survey team to improve drainage, manage the irrigations systems, ban water storage tanks around households and introduce larvivorous fish.

DDT was introduced for adult vector control in 1946 and led to a dramatic decline in malaria incidence within a year and expanded in 1953 to cover all towns and villages across the islands. By 1957 An. fluvatilis had almost disappeared but An. stephensi remained prolific. In 1953, there were only 169 locally acquired cases dropping to 38 cases by 1958; however, an epidemic occurred in 1959 due to flooding resulting in 329 cases (Hamza et al., 2006; Mahmood, 1992). The systematic documentation of imported malaria cases began in 1963 (Amin, 1989) and was recognised early on as a major threat to effective control in Bahrain. Twice yearly, DDT IRS remained the main vector control measure for many years, despite growing reluctance of the population to allow spray men into their houses (Delfini, 1977). Locally acquired malaria cases dropped to single digits by 1975. In 1976, there was an interruption in the downward trend, an epidemic of 35 P. vivax cases, felt largely to be a result of indiscriminate blockage of drains and a proliferation of landfills (Mahmood, 1992; Delfini, 1977; Oddo and Payne, 1982; Fig. 3.9). Under the guidance of WHO, the Ministry of Health began its elimination phase in 1977 with the introduction of active case detection and investigation to compliment the passive case-detection methods, presumptive treatment of immigrant labour and radical treatment of all parasite positive detected cases using chloroquine and primaquine (Delfini, 1977). In 1977, 111,000 inhabitants were protected by bi-annual house spraying with fenitrothion, and diesel oil was used for larval control every 8–10 days and occasional space spraying with pybuthrin in densely populated areas, which had started in 1968. Coincidental with vector control, rapid urbanisation across the island was felt to contribute to the decline in larval breeding sites (Oddo and Payne, 1982). The last autochthonous case was identified in 1979. Throughout the elimination attack phase malaria was integrated within other departments and divisions of the Ministry of Health; for example, epidemiological surveillance was part of the communicable disease section and vector control initiative as part of environmental health section – latterly a unit of malaria, insects and rodent control managed from six regional centres. As such, at no time was there a single malaria control or eradication department.

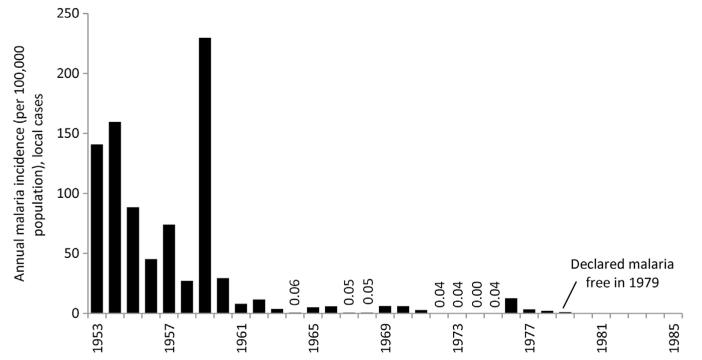

Figure 3.9. Annual locally acquired malaria case incidence 1953–1990 in the Kingdom of Bahrain per 100,000 resident populations.

(Data assembled from Amin (1989)). Bahrain was declared malaria-free in 1979. Population data sourced from census years between 1950 and 1985 (State of Bahrain Central Statistics Organization, 2002). Intercensal growth rates used to compute noncensus year population size.

From 1980, all fever cases screened at health clinics, the Salmaniya Medical Centre and the Public Health Laboratory cases were investigated by a health inspector including the screening of household and neighbourhood contacts. From 1976, imported cases remained relatively stable between 200 and 300 cases each year, mostly from India. Imported cases were detected at a time coincidental with returning travel to and emigration from the sub-continent during peak months of transmission in India (Fernandes and Mahmood, 1987). Between 1992 and 2001, no cases of indigenous malaria in Bahrain were reported, and the number of imported cases began to show a steady decline from 282 to 54 cases by 2001 with five countries, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Sudan, as the major importation origins (Ismaeel et al., 2004). Between 2005 and 2010, there have been 528 imported infections – 471 from India and Pakistan. The predominance of latent P. vivax infections from the Indian sub-continent continues to pose threats to reintroduction of malaria in Bahrain as An. stephensi remains present. Between 1992 and 2004, 792 active breeding sites were identified, despite regular larval control activities and thus there remains a potential for the reintroduction of indigenous malaria transmission (Ismaeel et al. 2004). Currently, vector control is maintained using diesel oil and where this is not appropriate temephos has been used since 1983 (Amin, 1989; Alsitrawi, 2003). There are also reports of continued use of IRS. Bahrain has been malaria-free since 1979 but has not sought certification from the WHO.

7. QATAR

Qatar has a small land border with Saudi Arabia but is otherwise surrounded by the Gulf. Combined with several islands, Qatar covers approximately 11,437 km2, with a hilly region known as the Dukhan hills in the west and salt flats along large parts of coastline. Oil was discovered in 1930s and the off-shore natural gas field is largest in the world. Of Qatar’s 1.5 million people, 60% live in Doha, a large part of rest of population now live in the fast-growing cities of Al Khor, Ras Laffan and Dukhan.

Not much is known about the historical risks of malaria in Qatar. In the early 1960s, the WHO classified Qatar as at risk of malaria. The principal vectors have been identified as An. stephensi and Anopheles multicolor. In 1977, only 116 cases were reported to the central laboratory, and most were thought to be imported although there was little systematic investigation or follow-up of detected cases during this period (Shidrawi, 1976). Artesian wells, irrigation areas, swamps and farms investigated for breeding sites in 1977 identified very few vectors, and it was felt that overall conditions were not favourable to dominant vectors of the region so while imported infections were high receptivity remained low (Shidrawi, 1976). In the early 1980s, a malaria unit was established under the division of infectious diseases and epidemic control. Their functions were to survey and control vector-breeding sites and undertake insecticide spraying in areas where Anopheles larvae were identified, mostly at farms in the northern reaches of the peninsula (El Manieh, 1982). It is not clear when local transmission was interrupted but it is likely that there were no locally acquired malaria infections since the 1970s and the Qatari government has never sought the official WHO certification. Imported infections varied between 100 and 450 cases per year since 1997 (Al-Kuwari, 2009). In 2011, there were 673 imported infections and 98% were P. vivax.