Abstract

Introduction

We analyzed the ability of various patient- and treatment-related factors to predict radiation-induced esophagitis (RE) in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with three-dimensional (3D) conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT), intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), or proton beam therapy (PBT).

Methods and Materials

Patients were treated for NSCLC with 3D-CRT, IMRT, or PBT at MD Anderson from 2000 to 2008 and had full dose-volume histogram (DVH) data available. The endpoint was severe (grade ≥3) RE. The Lyman-Kutcher-Burman (LKB) model was used to analyze RE as a function of the fractional esophageal DVH, with clinical variables included as dose-modifying factors.

Results

Overall, 652 patients were included: 405 treated with 3D-CRT, 139 with IMRT, and 108 with PBT; corresponding rates of grade ≥3 RE were 8%, 28%, and 6%, with a median time to onset of 42 days (range 11–93 days). A fit of the fractional-DVH LKB model demonstrated that the volume parameter n was significantly different (p=0.046) than 1, indicating that high doses to small volumes are more predictive than mean esophageal dose. The model fit was better for 3D-CRT and PBT than for IMRT. Including receipt of concurrent chemotherapy as a dose-modifying factor significantly improved the LKB model (p=0.005), and the model was further improved by including a variable representing treatment with >30 fractions. Examining individual types of chemotherapy agents revealed a trend toward receipt of concurrent taxanes and increased risk of RE (p=0.105).

Conclusions

The fractional dose (dose rate) and number of fractions (total dose) distinctly affect the risk of severe RE estimated using the LKB model, and concurrent chemotherapy improves the model fit. This risk of severe RE is underestimated by this model in patients receiving IMRT.

Keywords: intensity modulated radiation therapy, esophagitis, chemotherapy, DVH modeling

INTRODUCTION

Radiation esophagitis (RE) is a common form of toxicity among patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Previous attempts to identify predictors of RE have produced conflicting results. In a recent QUANTEC review of 12 relevant studies on predictors of esophageal toxicity published in 1999–2009, the authors found significant variation in the parameters that correlated with RE. The authors concluded that although there was “no singular threshold dose above which a toxic effect is observed, the parameters are closely interrelated” (1).

Data pertaining to predictors of RE amongst patients treated with different modalities, particularly photon versus particle therapy, are sparse. We previously reported our institution’s experience with predictors of acute RE in patients with NSCLC treated with definitive three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT) (2). We also reported a comparison of acute toxicity among patients treated with 3D-CRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), or proton beam therapy (PBT) and found high-grade RE in 18% of the 3D-CRT group, 44% of the IMRT group, and 5% of the PBT group (3). The focus of the current study was to assess the impact of selected clinical and dosimetric predictors of high-grade RE, and specifically to devise a predictive model of RE that accounts for dose-volume factors and is valid across different radiation therapy modalities. In addition, we sought to introduce a method for analyzing the data that takes into account the fact that the endpoint often occurs before the end of RT (when the full dose-volume histogram (DVH) would not be entirely relevant).

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patient Population

This investigation was approved by the institutional review board and was conducted in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. We studied all consecutive patients treated from 2000 to 2008 with 3D-CRT, IMRT, or PBT for NSCLC to a total dose of at least 50 Gy who had full DVH and RE data available for evaluation. Patients were exluded if they did not meet the following criteria: a history of radiation delivered in 1.8- to 2.5-Gy fractions, no prior irradiation of the lung, no history of esophageal cancer, no boost field used during treatment (i.e., received “straight” fields throughout treatment course so that fractional DVH could be computed), and completion of the prescribed radiation course.

Follow-up and Esophagitis Scoring

Toxicity was scored according to the Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0 (CTCAE v3.0) (4). The study endpoint was the development of Grade ≥3 RE within 6 months from the start of radiation therapy. Patients underwent evaluation by a radiation oncologist weekly during treatment. Follow-up monitoring included interval history and physical examination and endoscopy if indicated at 6 weeks after treatment, and then at the discretion of the treating physician thereafter.

Statistical Analysis

The χ2 and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare the distributions of categorical and continuous characteristics, respectively, amongst the groups treated with the different treatment modalities (3D-CRT, IMRT, PBT). The LKB model was used to analyze severe RE as a function of the esophageal DVH, with clinical factors included in the model as dose-modifying factors (DMFs) (5, 6). The factors assessed were number of fractions, sex, age (by decade), smoking status, Karnofsky performance status, receipt of induction chemotherapy, and receipt of concurrent chemotherapy. In addition, the effect of specific chemotherapeutic agents was considered in the following manner: any cisplatin-containing regimen, any carboplatin-containing regimen, any taxane-containing regimen, any etoposide-containing regimen, and any other agent (e.g., doxorubicin, gemcitabine, etoposide, other, or unknown agent). Agents delivered as induction therapy or concurrent with the radiation therapy were considered separately.

The effective radiation dose was used to determine the impact of radiation dose on esophagitis, as described elsewhere (7). In the LKB model, the effective dose is defined as:

| (1) |

where n is the volume parameter, Di is the dose to relative subvolume vi, and the sum extends over all dose bins in the DVH. With this formula, we can then model the probability of complications (normal-tissue complication probability, or NTCP) as a function of Deff as follows:

| (2) |

where

| (3) |

where TD50 is the dose that is expected to result in a 50% complication probability, and m is a measure of the slope of the sigmoid curve represented by the integral of the normal distribution. Because RE often appears before the end of therapy, we based the LKB model on the fractional (e.g. per fraction) DVH instead of the DVH representing the full course of treatment, with the number of dose fractions considered separately as an additional risk factor. Because the present study excluded patients whose treatment involved changes in field size, the fractional DVH could be computed from the full DVH by dividing each dose by the number of fractions delivered. Covariates were added to the fractional LKB model in a forward stepwise procedure, and the likelihood-ratio test was used to assess the improvement in model fit at each step. We then compared the fit of LKB models based on fractional DVH versus the full DVH by using Akaike’s information criterion, and we performed a 10-fold cross-validation to determine which model resulted in a lower mean-squared difference between observed and expected rates of RE (8).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Differences among Treatment Groups

Six hundred fifty-two patients were included in this study; 405 were treated with 3D-CRT, 139 with IMRT, and 108 with PBT. Three-dimensional conformal therapy was predominantly used in 2000–2005, IMRT in 2004–2008, and PBT in 2006–2008. This distribution reflects the practice patterns at our institution, where the primary shift from 3D-CRT to IMRT occurred in 2004–2005 and the use of PBT began in 2006.

Tables 1 and 2 list patient- and treatment-related characteristics. The median patient age was 66 years (range 33–92 years); the median radiation dose was 63 Gy (range 50–87.5 Gy); and the median number of fractions was 35 (range 25–42). No significant differences were evident among the three modality groups (3D-CRT vs. IMRT vs. PBT) in patient age, sex, or smoking status (P>0.05). Differences were found in pretreatment Karnofsky performance status, disease stage, tumor histology, radiation dose, and receipt of induction or concurrent therapy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n=652)

| No. of Patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | All Patients (%) | Treatment Modality | P Value | ||

| 3D-CRT (%) | IMRT (%) | PBT (%) | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 336 (52) | 202 (50) | 77 (55) | 59 (55) | 0.435 |

| Female | 310 (48) | 203 (50) | 62 (45) | 49 (45) | |

| Age, years | |||||

| Median (range) | 65 (33–92) | 64 (37–88) | 67 (33–82) | 0.134 | |

| Karnofsky Performance | |||||

| Score | |||||

| <70 | 37 (6) | 21 (5) | 7 (5) | 9 (8) | 0.049 |

| 70 | 98 (15) | 53 (13) | 25 (18) | 22 (20) | |

| 80 | 332 (52) | 228 (56) | 60 (43) | 46 (43) | |

| ≥90 | 174 (27) | 103 (26) | 45 (32) | 28 (26) | |

| Unknown | 5 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | |

| Smoking Status | |||||

| Current | 168 (26) | 107 (26) | 44 (32) | 19 (18) | 0.123 |

| Former | 426 (66) | 267 (66) | 86 (62) | 77 (71) | |

| Nonsmoker | 52 (8) | 31 (8) | 9 (6) | 12 (11) | |

| Clinical Disease Stage (AJCC 6th Edn) | |||||

| IA | 40 (6) | 34 (8) | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | <0.001 |

| IB | 56 (9) | 37 (9) | 7 (5) | 12 (11) | |

| IIA | 7 (1) | 6 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| IIB | 39 (6) | 20 (5) | 6 (4) | 13 (12) | |

| IIIA | 207 (32) | 137 (34) | 46 (33) | 27 (25) | |

| IIIB | 231 (36) | 146 (36) | 57 (41) | 30 (28) | |

| IV | 42 (6) | 25 (6) | 13 (9) | 4 (4) | |

| Recurrent/post-op | 10 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | 6 (6) | |

| Unknown | 14 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 13 (12) | |

| Tumor Histology | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 233 (36) | 140 (35) | 52 (37) | 42 (39) | 0.003 |

| SCC | 217 (34) | 125 (30) | 46 (33) | 49 (45) | |

| NSCLC, NOS | 196 (30) | 140 (35) | 41 (30) | 17 (16) | |

| Induction Therapy* | |||||

| No | 369 (57) | 247 (61) | 78 (56) | 80 (74) | 0.012 |

| Yes | 277 (43) | 158 (39) | 61 (44) | 28 (26) | |

| Concurrent Therapy* | |||||

| No | 190 (29) | 138 (34) | 31 (22) | 38 (35) | 0.026 |

| Yes | 456 (71) | 267 (66) | 108 (78) | 70 (65) | |

| Radiation Dose | |||||

| Median (range) | 63 Gy (50.4–84) | 63 Gy (50–74.25) | 74 Gy(RBE) (50–87.5) | <0.001 | |

Abbreviations: 3D-CRT, 3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; PBT, proton beam therapy AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; NSCLC NOS, non-small cell lung cancer not otherwise specified

These descriptors concern chemotherapy only. The number of patients receiving protective agents (e.g. celecoxib, amifostine) was: 3D-CRT, n=35, IMRT=11, PBT=1.

Table 2.

Systemic therapy regimens

| Regimen | Number of Patients |

|---|---|

| Induction Therapy | |

| Carboplatin | 212 |

| Paclitaxel | 173 |

| Docetaxel | 46 |

| Cisplatin | 29 |

| Etoposide | 14 |

| Gemcitabine | 12 |

| Navelbine | 10 |

| Other | 15 |

| Unknown | 11 |

| Concurrent Therapy | |

| Carboplatin | 341 |

| Paclitaxel | 294 |

| Cisplatin | 94 |

| Docetaxel | 77 |

| Celecoxib | 46 |

| Etoposide | 43 |

| Irinotecan | 16 |

| Gemcitabine | 3 |

| Radioprotective Agents¥ | 46 |

| Other | 12 |

| Unknown | 1 |

| Concurrent Chemotherapy Combinations | |

| Carboplatin + Taxane | 306 |

| Cisplatin + Etoposide | 36 |

| Cisplatin + Taxane | 34 |

| Cisplatin/Carboplatin Alone | 17 |

| Cisplatin + Irinotecan | 14 |

| Taxane alone | 11 |

| Other† | 26 |

Radioprotective agents (celecoxib, amifostine) may have been administered with chemotherapy.

Included doxorubicin alone, gemcitabine alone, etoposide alone, cisplatin + gemcitabine, carboplatin + etoposide, carboplatin + irinotecan, and carboplatin + taxane + other agent.

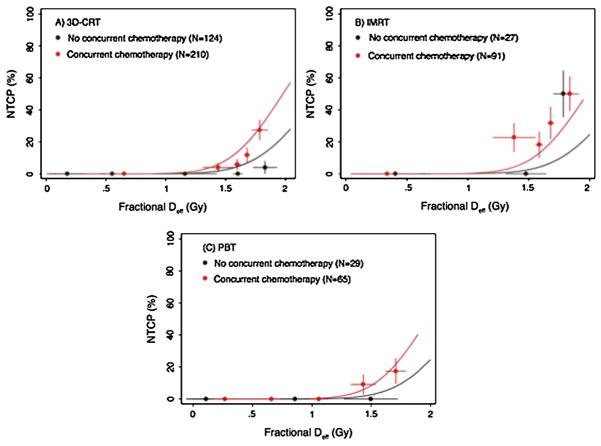

Rates of Esophagitis

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution time to severe RE per treatment group. Rates of severe RE (grade ≥3) were highest in the IMRT group (28% vs. 8% for 3D-CRT and 6% for PBT, p<0.05). There were no grade 5 toxicities.

Figure 1.

Distribution of esophagitis among patients treated with three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT), intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), or proton beam therapy (PBT).

Time to Severe Esophagitis

The median time to severe RE was 42 days from the start of radiation treatment (range 11–93 days). Because the median number of fractions was 35 (meaning that approximately 49 days elapsed from the beginning of treatment until the maximum grade of RE), a large percentage of events occurred before the completion of the radiation therapy. Thus it was deemed more appropriate that the DVHs analysis should be done with fractional (rather than full-treatment-course) dose-volume factors.

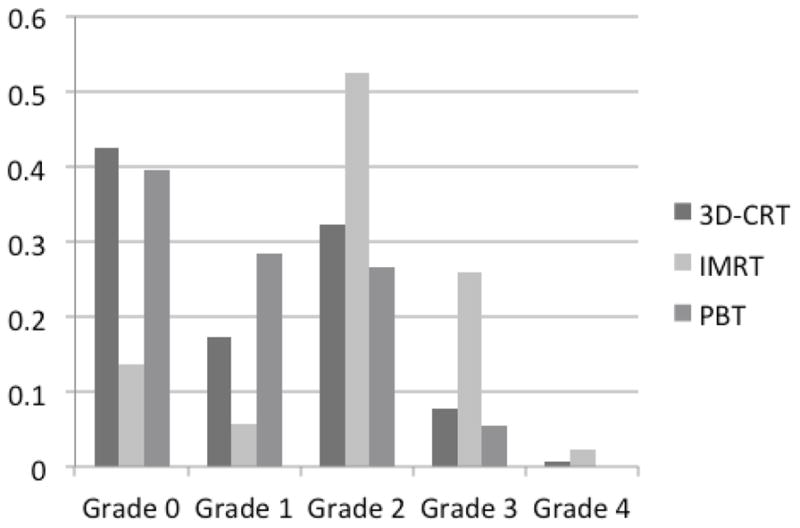

Fit of the LKB Model

A fit of the fractional LKB model demonstrated that the fractional effective dose was significantly different (p=0.046) than n=1 (the fractional mean dose). Treatment with concurrent chemotherapy significantly improved the model when it was included as a dose-modifying factor (p=0.005), and the model was further improved by the inclusion of an indicator variable representing treatment with >30 fractions (Figure 2; p=0.002). The resulting model parameters were fractional TD50=2.61 Gy, m=0.176, and n=0.13, with a DMF=1.15 for concurrent chemotherapy and DMF=1.15 for treatment with >30 fractions. In other words, the effective dose is increased by a factor of 1.15 for patients treated with concurrent chemotherapy or >30 fractions, and by a factor of (1.15)2 = 1.3 for a patient whose treatment had both of these features. Similarly, the TD50 for a patient treated with concurrent chemotherapy or >30 dose fractions is reduced by a factor of 1/1.15 = 0.870 (to 2.27 Gy), and by 1/1.3=0.769 (to 1.99 Gy) for a patient receiving both concurrent chemotherapy and >30 fractions. The clinical factors of age, gender, smoking status, stage, and histology did not affect the model fit.

Figure 2.

Lyman-Kutcher-Berman model fit based on concurrent chemotherapy and number of fractions. NTCP, normal tissue complication probability; Deff, effective (radiation) dose.

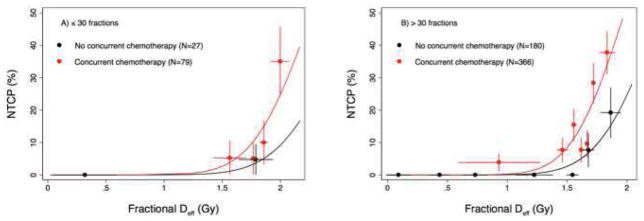

We next investigated whether individual systemic agents, delivered as induction or concurrent chemotherapy (or both) modified the risk of RE predicted by the model (as described above) based on use of any concurrent chemotherapy and number of radiation fractions. Compared to concurrent chemotherapy overall, no significant modifying effects were found for any induction agent (p>0.133 in all cases) or for concurrent treatment with cisplatin (p=0.997), carboplatin (p=0.843), or etoposide (p=0.966). There was also no dose-modifying effect for radioprotective agents (e.g. amifostine or celecoxib) (p=0.362). A trend was noted for delivery of concurrent taxanes to increase the risk of RE (p=0.105) and in fact delivery of concurrent taxanes improved the model slightly more (P=0.004) than concurrent therapy with any agent.

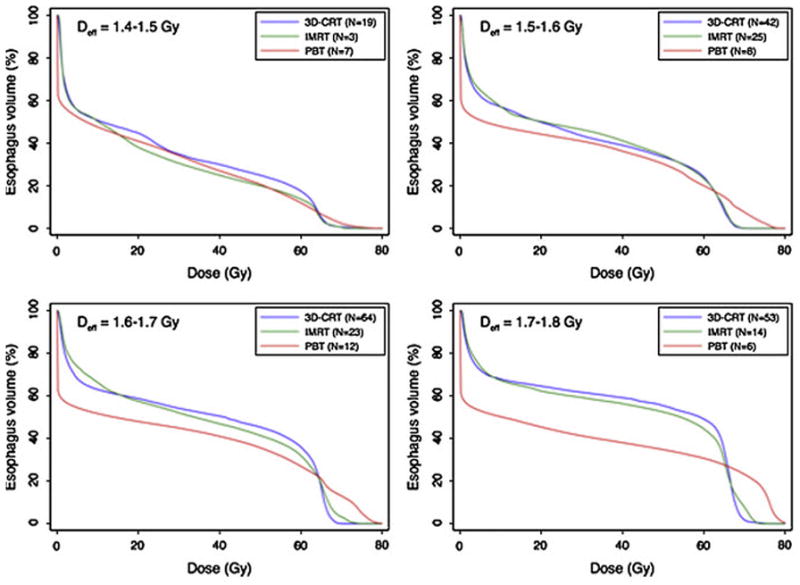

Figure 3 illustrates the resulting model fit, plotted separately for the data from each treatment modality. The model was found to fit well in estimating the difference in the risk of high-grade RE based on fractional effective dose (Deff) and the presence or absence of concurrent taxanes. However, the model clearly was a better fit for 3D-CRT and PBT than it was for IMRT. That is, the risk of RE was higher for patients treated with IMRT than would be predicted by this model, taking into account Deff and concurrent taxanes, as opposed to the other two techniques. Indeed, when IMRT was added to the model (as a covariate representing this technique), the improvement of the model fit was drastic (p=3.08 × 10−7). Indeed, the plots illustrated in Figure 4 (average esophageal DVH in patients receiving concurrent chemotherapy and >30 radiation fractions, in which narrow Deff ranges were chosen so that the doses would be expected to have the same effect) demonstrate that the difference between treatment modalities cannot be explained by the current LKB model. The final plot also demonstrates that the Deff can be similar for DVHs with different shapes.

Figure 3.

Lyman-Kutcher-Berman model fit by treatment modality among patients receiving >30 fractions of 3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT), intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), or proton beam therapy (PBT). NTCP, normal tissue complication probability; Deff, effective (radiation) dose.

Figure 4.

Average esophagus dose-volume histograms (DVHs) by treatment modality among patients with similar effective doses (Deff). 3D-CRT, 3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; PBT, proton beam therapy; NTCP, normal tissue complication probability.

We then fitted the LKB model using the full-treatment DVH, with concurrent chemotherapy included in the model. The resulting model did not fit the data as well as the model based on fractional DVHs, as assessed by the Akaike information criterion. This finding was confirmed when our 10-fold cross-validation showed that the model based on fractional DVH resulted in a lower mean-squared difference between predicted and observed esophagitis than the model based on the DVH corresponding to complete treatment.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first detailed assessment of dosimetric and clinical factors as they relate to high-grade RE after 3D-CRT, IMRT, or PBT for NSCLC. In addition, we have added to our previous dosimetric studies by utilizing the concept of fractional dose and distinguishing between factors such as number of fractions and dose per day. Our pertinent findings are as follows. First, patients treated with IMRT had the highest rate of severe RE. Second, most patients experienced the worst (highest grade) RE within 2 months of starting radiation therapy, and in many cases this occurred during the treatment. Indeed, although we included patients who experienced severe toxicity up to 6 months after initiating treatment, the maximum interval was 93 days, meaning that virtually all cases fit the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group definition of acute toxicity (<90 days). However, even though we used the fractional DVH rather than the whole-treatment DVH, we also found that receipt of >30 fractions improved the fit of the LKB model, suggesting that higher total dose also affects the risk of severe RE. Third, the Lyman model parameter n was 0.13, implying that dose-volume parameters representing large doses (e.g., maximum dose) are more appropriate than mean dose to the entire esophagus in assessing the risk of RE. Finally, the use of concurrent chemotherapy was the sole clinical/treatment factor that predicted grade ≥3 esophagitis, although the risk may also have been increased with receipt of particular chemotherapy agents (taxanes) concurrent with the radiation. However, the risk model based on fractional DVH, number of dose fractions, and concurrent chemotherapy significantly underestimated the incidence of severe RE observed among patients treated with IMRT.

This last finding, that patients treated with IMRT had the highest rate of RE, agrees with previous reports at our institution (3). Indeed, as demonstrated in the present study, IMRT was a risk factor for RE even when dosimetric and clinical factors were taken into account. Possible reasons for this increased risk are as follows. First, the inherent dose-distribution properties of IMRT could predispose recipients to develop higher-grade esophageal toxicity. IMRT involves the use of many beams to achieve conformality, whereas 3D-CRT and passive-scattering PBT both rely on 3D planning techniques; thus IMRT exposes a large proportion of the esophagus to low-dose radiation (e.g. “low dose bath”). Use of 3D-CRT or passive scattering PBT, by contrast, can allow complete or partial sparing of the esophagus. This low dose bath may contribute to increased toxicity, as suggested by prior data demonstrating that low-dose fields can contribute to normal tissue tolerance (9). Second, the spatial distribution of the esophageal dose may have been different for the IMRT group, meaning the cross-sectional anterior-posterior area and/or superior-inferior location of the irradiated region. That is, the anatomic region of the esophagus receiving dose, and thus the risk of RE, may have been different in the three treatment groups and not reflected in this dose-volume analysis. We are currently performing further dose and spatial distribution analyses to clarify the reason for the higher risk of esophageal toxicity with IMRT and are more attentive in our treatment planning to high doses given in the setting of the low- and intermediate-dose baths.

Our findings that the Lyman n parameter was significantly less than 1 and that in a large percentage of patients the maximum RE score was reached before the end of radiation therapy both have implications regarding the management of cases in which tumors are close to the esophagus. Several prior studies have also found n factors of <1, ranging from 0.06–0.69 (1). Thus, even though clinical trial results suggest that small segments of the esophagus can safely receive doses in excess of 70 Gy (10, 11), we recommend that the percentage of esophagus receiving a high dose be weighted heavily in evaluating a treatment plan. At our institution, dose constraints include not only a mean esophageal dose of ≤34 Gy but also a V70 <20% and a maximum esophageal dose of 80 Gy. These constraints are largely based on the QUANTEC recommendations described above (12), though we have added a maximum point dose to avoid large hot spots in patients being treated to 70 Gy or more.

The finding that patients treated with >30 fractions were more likely to experience RE than patients treated with fewer fractions, after accounting for the effects of fractional DVH and concurrent treatment, indicates that additional risk is associated with the continued delivery of dose fractions even for patients who have not experienced severe RE after the initial 30 fractions. This finding raises the question as to whether it would be preferable to model risk of esophagitis with the full DVH representing the entire course of therapy. However, we found that when the small volume parameter n and use of concurrent chemotherapy were included in the model fit, the fractional DVH was a better predictor of this particular toxic effect than was the full DVH. Therefore, separating the effects of fractional dose and number of fractions delivered improved the model for this endpoint, and probably for other acute endpoints as well.

The link between concurrent chemotherapy and severe RE was not surprising. While some studies have suggested that rates of esophagitis are higher with platinum agents than with taxanes (13, 14), data directly comparing chemotherapeutic agents and the risk of esophagitis in locally advanced NSCLC are sparse. Moreover, our institution recently reported an association between taxanes and an increased risk of pneumonitis (15). Given the prevalence of taxanes in definitive chemoradiation, the toxicity profile should continue to be explored both prospectively and retrospectively, particularly as radiation doses are further escalated.

Other than the inherent constraints of any retrospective study, this analysis had several limitations. First, the patients analyzed were not representative of all the patients we treated for locally advanced NSCLC; rather, they were selected based on the availability of full DVH and clinical data, and there were numerous differences in patient characteristics amongst groups that could have affected the overall results. Second, a percentage of patients received radioprotectors, which could bias the analysis by attenuating the effects of chemotherapeutic agents and/or radiation doses. However, we believe that the impact of this bias is minimal, given the relatively low percentage of patients that received these agents and because published data does not consistently support their use in minimizing toxicity as standard of care. Next, we recognize that after RT, patients are not routinely followed weekly, but rather at 6 weeks and 4.5 months after treatment, which could underestimate the true rate of esophagitis as well as the median development to this toxicity. Finally, scoring esophagitis with the CTCAE is inherently variable and dictated in large part by physician interventions. Thus, the reproducibility of this scoring, and therefore the factors predicting this outcome, is limited. Ideally, a more objective scoring system will be developed, possibly using patient- or physician-reported outcomes, which will improve the strength of all normal-tissue predictive studies.

Summary.

We examined multiple factors in predicting severe radiation esophagitis (RE) with three radiation modalities, and utilized the Lyman-Kutcher-Berman (LKB) model to take into account fractional dose. We found that concurrent chemotherapy was the most significant clinical factor influencing RE, and that patients receiving intensity modulated radiation therapy had high toxicity that could not be fully estimated by the LKB model. Finally, we found that high doses to small volumes are most predictive of RE.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support (Core) Grant CA016672 and by Varian Medical Systems.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Portions of this work were presented at the 52nd Annual Meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), November, 2010, San Diego, CA.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Werner-Wasik M, Yorke E, Deasy J, et al. Radiation dose-volume effects in the esophagus. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:S86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.05.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei X, Liu HH, Tucker SL, et al. Risk factors for acute esophagitis in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with concurrent chemotherapy and three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sejpal S, Komaki R, Tsao A, et al. Early findings on toxicity of proton beam therapy with concurrent chemotherapy for nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2011:117. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Common terminology criteria for adverse events, version 3. Bethesda, MD: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tucker SL, Dong L, Bosch WR, et al. Late rectal toxicity on RTOG 94-06: analysis using a mixture Lyman model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:1253–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.01.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peeters ST, Hoogeman MS, Heemsbergen WD, et al. Rectal bleeding, fecal incontinence, and high stool frequency after conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer: normal tissue complication probability modeling. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohan R, Mageras GS, Baldwin B, et al. Clinically relevant optimization of 3-D conformal treatments. Med Phys. 1992;19:933–944. doi: 10.1118/1.596781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan W. Akaike’s information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics. 2001;57:120–125. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bijl HP, van Luijk P, Coppes RP, et al. Influence of adjacent low-dose fields on tolerance to high doses of protons in rat cervical spinal cord. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:1204–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradley JD, Moughan J, Graham MV, et al. A phase I/II radiation dose escalation study with concurrent chemotherapy for patients with inoperable stages I to III non-small-cell lung cancer: phase I results of RTOG 0117. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 77:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schild SE, McGinnis WL, Graham D, et al. Results of a Phase I trial of concurrent chemotherapy and escalating doses of radiation for unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1106–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marks LB, Yorke ED, Jackson A, et al. Use of normal tissue complication probability models in the clinic. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:S10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werner-Wasik M, Paulus R, Curran WJ, Jr, et al. Acute Esophagitis and Late Lung Toxicity in Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy Trials in Patients with Locally Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Analysis of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) Database. Clin Lung Cancer. 12:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi A, Zhu G, Yu R, et al. A randomized phase I/II trial to compare weekly usage with triple weekly usage of paclitaxel in concurrent radiochemotherapy for patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 14:227–232. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2011.03.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCurdy M, McAleer MF, Wei W, et al. Induction and concurrent taxanes enhance both the pulmonary metabolic radiation response and the radiation pneumonitis response in patients with esophagus cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:816–823. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]