Abstract

Background

Concerns about weight gain may influence contraceptive use. We compared the change in body weight over the first 12 months of use between women using the etonogestrel (ENG) implant, the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) with women using the copper intrauterine device (IUD).

Study Design

This was a substudy of the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, a prospective cohort study of 9256 women provided no-cost contraception. Women who had been using the ENG implant, LNG-IUS, DMPA, or copper IUD continuously for at least 11 months were eligible for participation. We obtained body weight at enrollment and at 12 months and compared the weight change for each progestin-only method to the copper IUD.

Results

We enrolled a total of 427 women: 130 ENG implant users, 130 LNG-IUS users, 67 DMPA users, and 100 copper IUD users. The mean weight change (in kilograms) over 12 months was 2.1 for ENG implant users (standard deviation [SD] 6.7); 1.0 for LNG-IUS users (SD 5.3); 2.2 for DMPA users (SD 4.9); and 0.2 for copper IUD users (SD 5.1). The range of weight change was broad across all contraceptive methods. In the unadjusted linear regression model, ENG implant and DMPA use was associated with weight gain compared to the copper IUD. However, in the adjusted model, no difference in weight gain with the ENG implant, LNG-IUS, or DMPA was observed. Only black race was associated with significant weight gain (1.3 kg, 95% CI 0.2-2.4) when compared to other racial groups.

Conclusions

Weight change was variable among women using progestin-only contraceptives. Black race was a significant predictor of weight gain among contraceptive users.

1. Introduction

Weight gain is a commonly perceived side effect of hormonal contraception and may cause women to avoid or discontinue contraceptive methods.1 Prior studies have shown weight gain and changes in body composition among users of depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), progestin-only pills, and the subdermal levonorgestrel implant.2 Therefore, it is plausible that newer, long-acting progestin contraceptives may also cause weight gain. However, there are fewer studies investigating weight change with these methods, which include the etonogestrel (ENG) implant and the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS). In a 2006 retrospective study of ENG implant users, 5% discontinued the method for the complaint of weight gain, but weight measurements were not objectively collected.3 A 2004 study of nulliparous women choosing either the LNG-IUS or combined oral contraceptives failed to find a difference in reported weight change between the two methods.4 The ENG implant and the LNG-IUS are associated with high rates of effectiveness, continuation, and satisfaction.5,6 However, concerns about weight gain may limit some women's choice of these methods and additional evidence about the risk of weight gain with these contraceptive methods is needed.

A better understanding of weight gain and progestin-only contraceptives requires objective assessment of weight change. The aim of this study was to compare the 12-month weight change among progestin-only contraceptive users (ENG implant, LNG-IUS, and DMPA) to users of the copper intrauterine device (IUD). Our hypothesis was that progestin-only contraceptive users would gain more weight over the initial 12 months of use than users of the copper IUD.

2. Materials and methods

This study was a sub-study of the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. CHOICE is a prospective cohort study of 9256 women designed to promote the use of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods, remove financial barriers to contraception, and evaluate method continuation. The methods of this study have been described in detail elsewhere.7 Women between 14 and 45 years of age were eligible to participate in CHOICE if they desired reversible contraception and were willing to start a new method; had not had a hysterectomy or sterilization; spoke English or Spanish; and were sexually active or planning to become sexually active in the next 6 months. Enrollment occurred between August 2007 and September 2011 and follow-up is ongoing. We obtained approval from the Washington University School of Medicine Human Research Protection Office prior to participant recruitment.

In this substudy, we compared the change in body weight from baseline to 12 months among users of the ENG implant, the LNG-IUS, DMPA, and the copper IUD. Because the copper IUD contains no hormones, women using this method served as the control group. Potential participants were identified from the study database and contacted by telephone. Eligible women were continuous users of the above methods for at least 11 months who had enrolled at our university clinical research site between June of 2009 and May of 2011 and had height and weight measured at the enrollment visit. Women who did not speak English, were younger than 18 years of age, or had metabolic disorders known to affect body weight such as hypothyroidism or diabetes were not eligible for participation. At the time of scheduling the 12-month CHOICE telephone survey, a research assistant offered eligible women participation in this study.

Women who met the study criteria and agreed to participate were scheduled for an in-person visit at our university clinical research site within six weeks of their 12-month anniversary of enrollment. A research assistant obtained written informed consent and measured the participant's height and weight using the same scale and protocol used for baseline measurements. Participants were provided with a gift card in appreciation for their participation.

For our sample size calculation, we assumed that copper IUD users would have a mean change of +0.6 kg over 12 months. This is the average weight gain for U.S. reproductive-aged females reported in the 2003-04 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.8 We assumed that the weight gain in users of progestin-only contraceptives would be greater with a mean weight gain of 2.0 kg. Assuming an alpha of 0.05, 80% power, and a standard deviation of 3.0 kg in all groups, we would require a sample size of 73 women in each group. Analysis of the data when we reached the planned sample size showed wide variability in the range of weight change resulting in larger-than-anticipated standard deviations. Using a larger standard deviation of 5.0 kg in copper IUD users and 6.0 kg in progestin-only users, we increased our sample size to provide greater power, planning for 130 women in both the ENG implant and LNG-IUS group and 100 women in the copper IUD group.

We compared the demographic, socioeconomic and reproductive characteristics of participants. Categorical variables were compared with Pearson's χ2 or Fisher's exact test where appropriate, while continuous variables were compared using ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test depending on the sample distribution. We calculated the mean and median weight change over 12 months in our sample. Change in weight was normally distributed. A simple linear regression model using a 4-category method variable was used to compare weight change between each of the 3 progestin methods with the copper IUD. As race was associated with weight change in the univariate analysis, we also stratified the mean weight change by race comparing black women to all other women (due to the small numbers of other races, white race and other races were collapsed into a single category). Linear regression was used to calculate coefficients which estimate the mean change in weight attributable to any given covariate including contraceptive method. We considered a value statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the coefficient did not cross zero. Confounding was defined as covariates that were associated with both the outcome and the exposure, and also altered the effect size by greater than 10%. Confounding factors were included in the final adjusted models. We performed all analyses using STATA version11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

3. Results

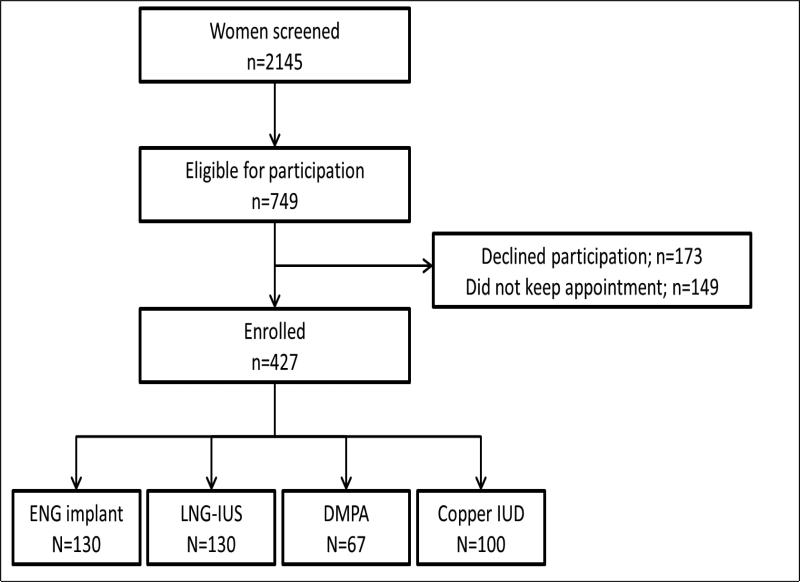

The study flow is shown in Figure 1. In total, 2145 women were screened for study eligibility, 749 met eligibility criteria, and 427 women (57.0%) enrolled in the study. Of these, 130 women were using the ENG implant, 130 were using the LNG-IUS, 67 were using DMPA, and 100 were using the copper IUD. All participants had been using their method for a minimum of 11 months continuously since enrollment, but none for more than 12.7 months. The baseline characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1 stratified by contraceptive method. Users of the four contraceptive methods were similar except that LNG-IUS and copper IUD users were slightly older; LNG-IUS users had a higher baseline weight; and copper IUD users were more likely to be white and have a college or graduate education. Forty-six percent of all participants were nulliparous. We compared women who declined participation in the substudy to participants and there was no statistically significant difference in BMI at the time of enrollment into the parent study.

Figure 1.

Study flow.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by contraceptive method.

| ENG implant (n=130) | LNG-IUS (n=130) | DMPA (n=67) | Copper IUD (n=100) | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| 24.4 | 5.6 | 26.7 | 5.1 | 25.2 | 5.8 | 27.9 | 6.0 | <0.01 | |

| Baseline Weight (kg) | 76.7 | 20.3 | 81.5 | 22.9 | 69.5 | 20.8 | 76.7 | 20.3 | 0.01 |

| Baseline BMI (m2/kg) | 28.6 | 7.3 | 30.3 | 8.3 | 26.2 | 7.1 | 26.9 | 6.7 | <0.01 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Baseline BMI (m2/kg) | 0.004 | ||||||||

| Normal (<25) | 41 | 31.5 | 53 | 53.0 | 46 | 35.4 | 36 | 53.7 | |

| Overweight (25-29) | 34 | 26.2 | 18 | 18.0 | 39 | 30.0 | 10 | 14.9 | |

| Obese (>30) | 55 | 42.3 | 29 | 29.0 | 45 | 34.6 | 21 | 31.3 | |

| Race | <0.01 | ||||||||

| Black | 79 | 60.8 | 76 | 58.5 | 47 | 70.1 | 33 | 33.0 | |

| White | 47 | 36.2 | 50 | 38.5 | 14 | 20.9 | 60 | 60.3 | |

| Others | 4 | 3.1 | 4 | 3.1 | 6 | 9.0 | 7 | 7.0 | |

| Hispanic | 4 | 3.1 | 1 | 0.8 | 2 | 3.0 | 5 | 5.0 | 0.25 |

| Low SES* | 74 | 56.9 | 77 | 59.2 | 44 | 65.7 | 51 | 51.0 | 0.29 |

| Parity | 0.39 | ||||||||

| 0 | 64 | 49.2 | 53 | 40.8 | 29 | 43.3 | 50 | 50.0 | |

| 1 | 32 | 24.6 | 38 | 29.2 | 24 | 35.8 | 22 | 22.0 | |

| 2+ | 34 | 26.2 | 39 | 30.0 | 14 | 20.9 | 28 | 28.0 | |

| Education | <0.01 | ||||||||

| High school or less | 52 | 40.0 | 26 | 20.0 | 21 | 31.3 | 12 | 12.0 | |

| Some college | 43 | 33.1 | 55 | 42.3 | 34 | 50.7 | 40 | 40.0 | |

| College/Graduate school | 35 | 26.9 | 49 | 37.7 | 12 | 17.9 | 48 | 48.0 | |

Low SES defined as current receipt of public assistance or reported difficulty paying for transportation, housing, medical expenses or food in past 12 months

ENG – etonogestrel; LNG-IUS – levonorgestrel intrauterine system; DMPA – depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; IUD – intrauterine device; BMI – body mass index

The mean and median weight changes are shown in Table 2. The mean weight change at 12 months was greater among ENG implant and DMPA users compared to copper IUD users; +2.1 kg among ENG users and +2.2 kg among DMPA users. LNG-IUS users mean change in weight was similar to copper IUD users at +1.0 kg. There was significant variability in weight change among contraceptive method groups ranging from −16.3 to +32.7 kg for ENG implant users, −15.9 to +19.1kg for LNG-IUS users, −7.7 to +21.8 for DMPA users, and −16.3 to +16.3 kg for copper IUD users. Because race was associated with weight change, we also stratified weight change by race. Black women had a greater mean weight change across all of the contraceptive methods compared to white/other women although this was not statistically significant. When analyzed within the race category, the mean weight change for each progestin method was not significantly different than the copper IUD.

Table 2.

Weight change (kg) at 12 months by contraceptive method for all women and stratified by race

| n | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | Minimum | Maximum | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Women | |||||||

| ENG implant | 130 | 2.12 | 6.65 | 1.59 | −16.33 | 32.66 | 0.01 |

| LNG-IUS | 130 | 1.03 | 5.33 | 0.91 | −15.88 | 19.05 | 0.25 |

| DMPA | 67 | 2.20 | 4.85 | 1.81 | −7.71 | 21.77 | 0.02 |

| Copper IUD | 100 | 0.16 | 5.06 | 0.00 | −16.33 | 16.33 | Ref |

|

Black Race | |||||||

| ENG implant | 79 | 2.6 | 7.1 | 1.8 | −16.3 | 32.7 | 0.13 |

| LNG-IUS | 76 | 2.0 | 5.5 | 1.4 | −15.9 | 19.1 | 0.31 |

| DMPA | 47 | 2.3 | 4.4 | 1.8 | −7.3 | 15.9 | 0.26 |

| Copper IUD | 33 | 0.7 | 6.8 | 0.9 | −16.3 | 16.3 | Ref |

|

White/Other Race | |||||||

| ENG implant | 51 | 1.4 | 5.9 | 0 | −6.4 | 17.7 | 0.12 |

| LNG-IUS | 54 | −0.3 | 4.9 | −0.2 | −13.6 | 14.1 | 0.83 |

| DMPA | 20 | 2.0 | 6.0 | 1.4 | −7.7 | 21.8 | 0.10 |

| Copper IUD | 67 | −0.1 | 4.0 | 0.0 | −10.4 | 10.9 | Ref |

p-values calculated using linear regression with copper IUD as referent group

ENG – etonogestrel; LNG-IUS – levonorgestrel intrauterine system; DMPA – depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; IUD – intrauterine device

In the unadjusted linear regression results shown in Table 3, both the ENG implant and DMPA were associated with weight gain, with an increase of approximately 2.0 kg over that observed among copper IUD users. There was no weight gain observed with the LNG-IUS compared to the copper IUD. In the crude analysis, black race was also associated with weight gain. Women using the ENG implant and LNG-IUS had a slightly higher mean baseline BMI than women using DMPA or the copper IUD (Table 1). However, being overweight or obese at baseline was not associated with weight gain in the crude analysis.

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted linear regression models of characteristics associated with weight change at 12 months

| Crude | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Weight Change (Beta) | P value | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

| Age | −0.09 | 0.07 | −0.18 | 0.01 |

| Baseline weight | 0.00 | 0.87 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Baseline BMI (m2/kg) | ||||

| Normal (<25) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Overweight (25-29) | 1.14 | 0.11 | −0.25 | 2.54 |

| Obese (≥30) | −0.04 | 0.94 | −1.28 | 1.19 |

| Contraceptive method | ||||

| ENG implant | 1.95 | 0.01 | 0.48 | 3.43 |

| LNG-IUS | 0.87 | 0.25 | −0.60 | 2.34 |

| DMPA | 2.04 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 3.79 |

| Copper IUD | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 1.60 | <0.01 | 0.53 | 2.68 |

| White/Other | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Parity | ||||

| 0 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 1 | 0.75 | 0.26 | −0.56 | 2.05 |

| 2+ | −0.51 | 0.44 | −1.82 | 0.80 |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Some college | −1.04 | 0.13 | −2.40 | 0.32 |

| College/Graduate school | −0.31 | 0.66 | −1.72 | 1.09 |

| Adjusted | ||||

| Age | −0.06 | 0.21 | −0.16 | 0.03 |

| Contraceptive method | ||||

| ENG implant | 1.37 | 0.08 | −0.16 | 2.91 |

| LNG-IUS | 0.46 | 0.55 | −1.04 | 1.95 |

| DMPA | 1.37 | 0.14 | −0.44 | 3.18 |

| Copper IUD | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 1.34 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 2.44 |

| White/Other | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

ENG – etonogestrel; LNG-IUS – levonorgestrel intrauterine system; DMPA – depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; IUD – intrauterine device

The variables shown in Table 3 were evaluated as potential confounders in the unadjusted linear regression model investigating the association between contraceptive method and weight change. Only age and race were found to be confounders and these were included in the final adjusted model. After adjusting for race and age, the associations observed between progestin-only contraceptives and weight change were attenuated and no longer statistically significant. In the adjusted model, black race continued to be associated with weight change with black women gaining 1.3 kg more than white/other women over 12 months (with estimated weight gain ranging from 0.23-2.44 kg, p=0.02).

4. Discussion

In this study, we compared weight change at 12 months between users of three progestin-only contraceptive methods, the ENG implant, the LNG-IUS, and DMPA, with users of the non-hormonal copper IUD. After adjusting for age and race, we did not find statistically significant differences in weight change between users of the ENG implant, LNG-IUS or DMPA when compared to copper IUD users. While data about weight change with long-acting, progestin contraceptives are limited, a recent study of 76 women found that LNG-IUS users had a mean weight gain of 2.9 kg at 12 months compared to 1.4 kg in copper IUD users, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=.07).9 Our findings also are supported by a recent Cochrane review of the effects of progestin-only contraceptives on weight where the authors concluded, “[W]e found little evidence of weight gain when using progestin-only contraceptives. Mean gain was less than 2 kg for most studies up to 12 months, and usually similar for the comparison group using another contraceptive.”2

Of note, we did not find a significant difference in weight change between DMPA and copper IUD users despite prior studies that have demonstrated an association with DMPA and weight gain.10-12. A previous 36-month longitudinal study of 703 contracepting women found that DMPA users had a 5.1 kg weight gain compared to 1.5 kg gain among oral contraceptive users (p<.001) and 2.1 kg gain among non-hormonal contraceptives users (p<.001). In addition, DMPA users had a greater increase in total body fat and percent body fat.11 The authors did not report on the effect of race on weight gain among DMPA users. Our lack of association between DMPA and weight gain may be due to our relatively small sample size.

We did observe that race was a predictor of weight gain in our study population regardless of contraceptive method use and age. Mean weight changes were higher for black women than for white/other women for each method group. Longitudinal studies of weight gain have found similar associations between race and weight gain, particularly among women.13-15 Recent data from NHANES supports racial disparities in obesity with black women being almost twice as likely to be obese compared to white women (58.5% versus 32.2%).16 These racial disparities are likely due to a complex interplay of multiple factors, as controlling for differences in socioeconomic status do not eliminate the effect.15

An unexpected finding of our study was the wide variability in weight change over the 12 months of contraceptive use. Wide variability was observed even among the copper IUD users and suggests that multiple factors play a role in weight change over time. The large amount of variability did decrease our power to detect significant differences in weight change. We increased our sample size to offset the variability; however, we would have needed almost 300 women per group to maintain 80% power with the observed standard deviations. We did not enroll as many DMPA users as users of the other methods because there is already substantial evidence to support the relationship between DMPA and weight gain.

Strengths of our study include a racially and socioeconomically diverse cohort and the objective measurement of body weight at two time points using the same scale and measurement protocol. There was potential for selection bias as participants had to come for an in-person visit and agree to be weighed. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the baseline BMI of women who agreed to participate and women who declined to participate. The results of our study may not be generalizable to other U.S. women seeking contraception as our study population is limited to a single geographical area. However, the CHOICE cohort overall is racially and socioeconomically diverse with demonstrated comparability to both state and national samples.17 In spite of these limitations, this study provides important results about the association between race, ENG implant and LNG-IUS use, and weight change.

Our objective in this study was to increase our understanding of the relationship between long-acting progestin contraceptives and weight change. We did not find an association between use of the ENG implant and LNG-IUS and weight gain in the first 12 months of use. We did find that black women gained more weight over 12 months than non-black women adjusting for contraceptive method and age. However, there was broad variability in weight change. There are many factors that influence weight gain, with race a likely influence. It is important for healthcare providers to have an evidence-based understanding of the effect of contraception on weight gain so that they can provide appropriate and accurate counseling to patients.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by: 1) an anonymous foundation; 2) award number UL1 RR024992 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH); and 3) award number K23HD070979 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NICHD, NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Dr. Madden receives research funding from Merck & Co, Inc and honorarium from Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Allworth receives research funding from Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Peipert receives research funding from Merck & Co, Inc and Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, Schulz KF, Helmerhorst FM. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9):CD003987. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003987.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez LM, Edelman A, Chen-Mok M, Trussell J, Helmerhorst FM. Progestin-only contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(4):CD008815. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008815.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakha F, Glasier AF. Continuation rates of Implanon in the UK: data from an observational study in a clinical setting. Contraception. 2006;74:287–289. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suhonen S, Haukkamaa M, Jakobsson T, Rauramo I. Clinical performance of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and oral contraceptives in young nulliparous women: a comparative study. Contraception. 2004;69:407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1998–2007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105–1113. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821188ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Mullersman JL, Peipert JF. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:115, e111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) & National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dal'Ava N, Bahamondes L, Bahamondes MV, de Oliveira Santos A, Monteiro I. Body weight and composition in users of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2012;86:350–353. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark MK, Dillon JS, Sowers M, Nichols S. Weight, fat mass, and central distribution of fat increase when women use depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:1252–1258. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berenson AB, Rahman M. Changes in weight, total fat, percent body fat, and central-to-peripheral fat ratio associated with injectable and oral contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gyneco. 2009;200:329, e321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pantoja M, Medeiros T, Baccarin MC, Morais SS, Bahamondes L, Fernandes AM. Variations in body mass index of users of depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate as a contraceptive. Contraception. 2010;81:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke GL, Bild DE, Hilner JE, Folsom AR, Wagenknecht LE, Sidney S. Differences in weight gain in relation to race, gender, age and education in young adults: the CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. Ethn Health. 1996;1:327–335. doi: 10.1080/13557858.1996.9961802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Truong KD, Sturm R. Weight gain trends across sociodemographic groups in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1602–1606. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.043935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baltrus PT, Lynch JW, Everson-Rose S, Raghunathan TE, Kaplan GA. Race/ethnicity, life-course socioeconomic position, and body weight trajectories over 34 years: the Alameda County Study. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1595–1601. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.046292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kittur ND, Secura GM, Peipert JF, Madden T, Finer LB, Allsworth JE. Comparison of contraceptive use between the Contraceptive CHOICE Project and state and national data. Contraception. 2011;83:479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]