Abstract

Despite intensive efforts towards the improvement of outcomes after acquired brain injury functional recovery is often limited. One reasons is the challenge in assessing and guiding plasticity after brain injury. In this context, Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) - a noninvasive tool of brain stimulation - could play a major role. TMS has shown to be a reliable tool to measure plastic changes in the motor cortex associated with interventions in the motor system; such as motor training and motor cortex stimulation. In addition, as illustrated by the experience in promoting recovery from stroke, TMS a promising therapeutic tool to minimize motor, speech, cognitive, and mood deficits. In this review, we will focus on stroke to discuss how TMS can provide insights into the mechanisms of neurological recovery, and can be used for measurement and modulation of plasticity after an acquired brain insult.

1. Introduction

The impact of acquired brain injuries, for example stroke, upon individuals, families, and society continues to increase due to both the aging of the general population and the increasing length of post-insult survival (1). Unfortunately, functional outcomes remain often limited. Consider stroke: within the past decade, a significant amount of research has delineated the clinical course of post-stroke recovery and has begun to elucidate potential mechanisms of injury and recovery. Yet the mechanisms underlying stroke recovery remain fairly misunderstood and effective neurorehabilitation interventions remain insufficiently proven or widespread.

There are distinct phases in neurological recovery. For example, one can conceptualize an acute and a chronic phase. In the acute phase there is usually a rapid natural recovery, while in the chronic phase natural recovery is unlikely and secondary worsening of function is possible. In the acute phase, neurological deficits observed are partly due to the death of neuronal tissue in the affected region. Restoration of viable blood supply to this region, and resolution of perilesional edema and inflammation are factors possibly contributing to rapid recovery of function following stroke in the acute phase (2). Another important consideration is the disruption of neuronal networks in undamaged brain regions that are remote from the original injury yet functionally connected, such as subcortical regions or the contralesional motor cortex. In part this concept matches the notions of “diaschisis”, advanced by von Monakow as a principle contributing to explain the functional impact and eventual recovery from brain lesions, and more recently confirmed with modern neuroimaging techniques (3). In the chronic phase, natural recovery is less likely and in fact a decrease in functioning can be observed. In this phase, cortical reorganization plays a major role in determining neurological deficits. Plasticity in chronic stroke may not be beneficial and can lead to further worsening of function, including increased transcallosal inhibition from the unaffected to the affected motor cortex (4). Therefore, greater understanding of the pathophysiology of functional deficits at various times (phases) after a brain insult is critical to optimize interventions. For example, understanding the extent and purpose of cortical reorganization might guide treatments aiming to improve motor function. In addition, it might be possible to minimize damage or enhance recovery by modulating cortical excitability or modifying processes of diaschisis.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) is a valuable non-invasive neurophysiologic tool to characterize the pathophysiologic processes involved in functional consequences after a brain insult and in harnessing such insights to maximize functional outcomes. In this review we shall focus on stroke and (1) Describe the neurophysiologic changes that occur after stroke; (2) Describe current rehabilitation techniques affecting brain activity and plasticity in order to compare them with TMS; and (3) Discuss the role of TMS in measuring cortical reorganization following stroke as well as the role of rTMS as an intervention in chronic stroke to enhance plasticity when used alone or in combination with other interventions to augment current pharmacotherapy and rehabilitation therapies for stroke rehabilitation.

2. Cortical Reorganization

In this section we discuss the role of cortical reorganization to better understand the role of interventions – such as TMS – that can both index and modulate cortical plasticity.

For example, consider motor deficits, which can be significantly improved by reorganization of function within surviving brain elements. At the cellular, systems, and behavioral levels, the motor system is capable of substantial reorganization after stroke. Some of these changes are spontaneous and occur during the weeks to months following a stroke. A number of studies have provided insights into the nature of this motor system reorganization. Several animal studies have described a wide range of multifocal changes with an experimental unilateral infarct, including changes in growth-related proteins, neuronal structure, and cortical representational maps. Human brain mapping studies have largely been concordant, illustrating diffuse changes throughout bilateral motor system elements.

Findings from recent studies indicate that cortical reorganization after cerebral damage is a normal compensatory mechanism that could perhaps be leveraged in stroke rehabilitation. A study performed by Dijkhuizen et al. (2001), correlated alterations in sensorimotor function in rats with the evolution of changes in brain activation, in relation to cerebral pathophysiologic status post-stroke. Within the first 24 hours after stroke onset, there was a marked impairment in the contralesional (left) forelimb, indicating sensorimotor dysfunction. Functional recovery was paralleled by temporal changes of the cortical activation pattern during stimulation of the impaired forelimb. A second study by Dijkhuizen et al. (2001) suggested that dysfunction of the hemiplegic forelimb was associated with loss of brain activity in M1 and S1, as revealed by fMRI. The recovery of sensorimotor functions was accompanied by changes in the activation and recruitment pattern of cortical areas (5, 6).

In a study of intra-cortical magnetic stimulation (ICMS), Liu and Rouiller (1999) investigated the mechanisms of dexterity recovery following a unilateral lesion of the sensorimotor cortex in adult monkeys. In this study, Liu and Rouiller showed that remote plastic changes in the premotor cortex (PM) (rather than the primary motor cortex (M1)) were responsible for partial behavioral recovery. This indicates that the burden of processing may be shifted to remote cortical areas to aid function (7).

Human studies have also demonstrated cortical reorganization. Feydy et al. (2002) showed a large range of functional cortical reorganization patterns in stroke patients, based on fMRI sessions ranging from one to six months after stroke. The study compared the response of muscle movement to TMS stimulation of the motor cortex of the affected and unaffected hemispheres; additionally, the degree of Wallerian degeneration of the descending motor pathways was assessed via MRI. Functional recovery was found to be inversely associated with the amount of axonal damage and degeneration (supported by delayed or nonexistent response to TMS stimulation). Thus, the degree of the initial injury and evolution of reorganization determined the functional motor recovery (8).

Interindividual variability in the pattern of recovery after stroke is certainly extensive and not all factors contributing to such variability are clear. Genetic and environmental factors are certain to contribute and interact in complex ways. Ultimately, individualized studies and interventions are likely to prove most effective. However, for now certain approximations and generalization can be drawn and might be helpful.

There appear to be three patterns of how distributed, bihemispheric cortical activation evolves after a stroke. Initially, immediately after injury, lesional and perilesional activity is suppressed, possibly due to surround inhibition aimed at minimizing damage by preventing excitotoxicity cascades. Thus, neural activation appears particularly prominent in contralesional areas. Thereafter, presumably promoted by reduction of perilesional inhibition and shifts in interhemispheric interactions, there is a progressive bihemispheric activation and eventually a shift back to perilesional activity. Therefore, eventually perilesional activity enhances and seems to drive functional recovery. The implication is thus that alterations in this complex distributed organization over time might lead to disrupted recovery processes and ultimately maladaptive plastic changes and dead-end strategies. A further important implication is that the actual interventions to promote recovery will likely need to be different at different timepoints following an brain insult (stroke). However, while such general conceptualization are appealing, it remains essential to remember that individual differences, related for example to preexisting differences in cortico-cortical connectivity and brain networks, are certain to hugely influence such dynamic processed. Therefore, ideally, longitudinal, individual studies would be needed to fully harness the potential of neuromodulatory interventions to promote recovery by guiding such reorganization processes. In order to consider such approaches, methods to characterize changes in bi-hemispheric brain networks and cortical excitation/inhibition balance serially following stroke are critical. Noninvasive brain stimulation techniques offer the possibility of gathering such information.

3. Non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS)

Non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) modalities such as Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) allow researchers to study human brain activity in real time, characterize balance of excitation and inhibition, and ultimately guide plastic changes.

TMS is based on the principle of electromagnetic induction, as discovered by Michael Faraday in 1838. TMS is a non-invasive method of stimulating cortical motor neurons through the scalp and skull. This technique uses a wire coil placed over the scalp to generate a local magnetic field. This magnetic field creates an electrical current that flows through the targeted area, inducing neuronal depolarization. Since its development (9) TMS has enabled safe and painless investigation of the primary motor cortex and central motor pathways.

Although the other commonly used technique of NIBS - tDCS – has been used for a much longer period of time compared with rTMS; only recently initial mechanistic studies in humans have investigated tDCS mechanisms of action and also more effective parameters of stimulation (10). tDCS does not cause resting neurons to fire; it rather modulates the spontaneous firing rate of neurons by influencing their membrane potential through constant polarizing electric fields that can influence electrically charges substances such as ions and transmembrane proteins. This quality distinguishes tDCS from other stimulation techniques, such as TMS, which excite neurons directly (11–13).

The magnetic field of TMS reaches only 2–3 centimeters into the brain, directly beneath the treatment coil. With stereotactic MRI-based control, the precision of targeted TMS can be approximated to within a few millimeters (14). Recent development of navigated brain stimulation (NBS), allows the location of the coil to be continuously visualized on a 3D rendering of an individual MR image. This ensures that the coil remains in a stable location without tilting or rotating on a sweep-to-sweep basis with sub-millimeter precision, thus enabling consistent and precise targeting of a specific brain region (15–17).

TMS can track cortical excitability and reorganization during clinical rehabilitation of stroke patients (18). Because TMS is a non-invasive, low risk technique, it is particularly well suited for translation into clinic.

When applied repetitively, trains of rTMS can modify cortical activity beyond the duration of the rTMS train itself (19). Effectively, this provides an opportunity to provoke and study the mechanisms of acute cortical reorganization in the healthy human brain and their effects on the corticospinal system. In addition, such sustained neuromodulatory effects open the door to exploring therapeutic interventions. The exact mechanisms of such lasting neuromodulatory effect of rTMS (or tDCS) remain unclear. However, the magnitude and duration of such effects are critically dependent on the stimulation parameters. Three factors that influence the effect of rTMS are frequency, intensity and duration of stimulation. In general, burst of high-frequency stimulation (5 Hz and above) tend to lead to a facilitation of activity in the targeted brain region, while continuous low frequency stimulation (around 1Hz) renders the targeted brain region suppressed in activity. It is thus possible to either enhance or suppress activity in the targeted brain region depending on the pattern of stimulation applied. However, it is worth noting that there are substantial interindividual differences in this regard (20). Such modulatory effects appear to also be influences by the intensity of the applied stimulation. However, the precise relation remains insufficiently studied.

Stroke alters the balance between excitation and inhibition between the hemispheres. As we have discussed, the balance between hemispheres may in fact shift over time following a stroke. Depending on the time from the stroke, down-regulation of the activity in the lesional hemisphere, down-regulation of activity in the unaffected hemisphere, or up-regulation of activity in perilesional brain regions may minimize damage or promote functional recovery (13, 20–24) (23–25) (26). The ability of rTMS to modulate cortical excitability in a frequency-dependent manner can thus be exploited in studies investigating stimulation of either the affected or unaffected hemispheres of stroke patients.

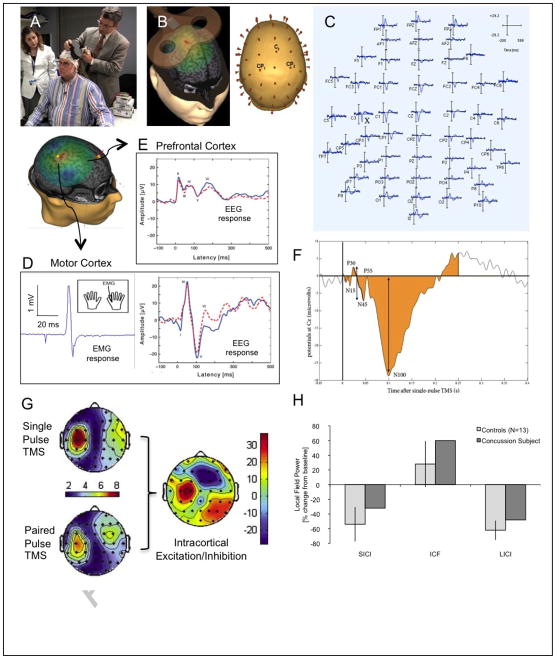

4. Using TMS to characterize excitation/inhibition balance and cortical plasticity (Figure 1)

FIGURE 1. Summary of TMS methodology.

(A) The Nexstim TMS system is one of the available systems that provides neuronavigation and real-time display of induced current in the subject’s brain and targeted brain area (B), and enables fully integrated EMG (D) and EEG (C, D,E) recording. TMS-evoked EEG potentials (D, E) can be quantified using various measures of amplitude, timing and magnitude (F) and topographic distribution (G), allowing quantification of various measures of E/I balance. H demonstrates feasibility of the use of this techniques in the assessment of patients with acquired brain insults, in this case mild traumatic brain injury. It shows the average response to ICF, SICI and LICI for 13 control subjects and a pilot participant with a recent concussion. Controls show the expected suppression to SICI and LICI and enhancement in ICF. The TBI patient, shows less SICI and LICI, and more ICF than controls. Note that a subject with concussion shows reduced SICI and LICI, and increased ICF (as compared with 13 normal controls ± 95% confidence intervals).

Navigated TMS utilizes individual structural MRI to enable online monitoring of the targeted cortical region, as well as coil position and orientation within and across sessions. The Nexstim system also calculates and displays the results of finite element models of the induced currents in each participant’s brain, and integrates a high-density EEG system. This provides trial by trial information about the induced electric field for every TMS pulse, the localization of the induced current maxima, all the TMS parameters, and the recorded EEG free of artifacts thanks to a pin-and-hold circuit. Such a system provides the reproducibility of the stimulation parameters that is essential for any comparative or longitudinal study. Critically, the calculation and display of the induced currents will allows to overcome the limitation of TMS targeting according to anatomical brain structures alone, since interindividual differences in structure–function relationships, particularly in individuals with brain pathology, may alter the induced currents and thus precision of the neuronavigation system.

Single and paired pulse TMS have been used to measure cortical plasticity associated with neuromodulatory approaches such as sensory-motor training, brain stimulation, motor learning interventions and deafferentation. Furthermore, when measures of cortical excitability are analyzed within subject as comparing before and after a given intervention, these measurements provide important insights into cortical plasticity. Here we review some of these measurements such as motor threshold, motor evoked potential and intracortical facilitation and inhibition.

Motor Threshold

Motor threshold refers to the lowest TMS intensity necessary to evoke motor evoked potentials (MEPs) in the target muscle when single-pulse stimuli are applied to the motor cortex. Following guidelines from the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology (IFCN) motor threshold is defined as the lowest intensity required to elicit MEPs of more than 50 μV peak-to-peak amplitude in at least 50% of 10 successive trials, at resting or activated (slightly contracted) target muscles (27). TMS activates a mixed population of inhibitory and excitatory cortical interneurons, which can affect local and remote pyramidal tract neurons. The frequency, intensity, and coil orientation at which TMS pulses are delivered to the cortex significantly affect its consequences and its uses. Ultimately though the motor threshold appears to be an index of cortical membrane excitability and thus of Na/K pump function.

Motor Evoked Potentials (MEP)

When TMS is applied at intensities above motor threshold, the activation of excitatory interneurons can result in descending cortico-spinal volleys (direct (D) and indirect (I) waves that can be recorded from epidural electrodes over the spinal cord). The proportion of D and I waves depends, amount other factors on the intensity of the stimulation and the orientation of the current induced in the brain. The descending volleys can depolarize spinal alpha motor neurons, lead to peripheral nerve activation, neuromuscular endplate and ultimately muscle fiber contraction. The compound motor action activity (MEP) can be recorded using electromyography (EMG) with surface or needle electrodes from the muscles of interest. The amplitude, area under the curve, and latency of MEPs are all used in various ways to measure motor cortical excitability.

A reduced amplitude of MEPs is associated with a central motor conduction failure in many cases. However, the size and latency of MEPs show great inter- and intra-individual variability, leading to a broad range of normal values and limiting clinical utility of MEP measures alone. In addition, MEPs by TMS are usually much smaller than compound muscle potentials (CMAPs) evoked by peripheral nerve stimulation, and TMS does not seem to accomplish depolarization of all spinal motor neurons. Solving these problems, Magistris et al. (28, 29) developed a triple stimulation technique, which provides a quantitative electrophysiological measurement of the central motor conduction failure. With their method, applying peripheral stimuli at Erb’s point and wrist stimulation as well as TMS, they have induced two collisions in the peripheral motor neurons and have successfully suppressed the desynchronization of MEPs caused by multiple descending volleys evoked by TMS. Their methods demonstrate that TMS can depolarize almost all spinal motor neurons supplying target muscle in healthy subjects. According to their data, the sizes of MEPs by TMS get smaller than those of CMAPs because of ‘phase cancellation’ in which the negative phases of individual motor unit potentials are cancelled by the positive phases of others because of their various latencies. This technique provides new insights into corticospinal tract conduction of healthy normal subjects and, when applied to patients with corticospinal dysfunction, is 2.75 times more sensitive than conventional MEPs in detecting corticospinal conduction failures. This technique thus improves detection and also gives quantitative information on deficits of the corticospinal conduction. Further studies are required, but the triple stimulation technique is useful in following clinical courses of patients, assessing and following treatment of disorders affecting central motor conduction, and ultimately predicting prognosis of functional motor recovery after brain insults.

Silent period

When a subject is instructed to maintain muscle contraction of a targeted muscle and a single TMS pulse with suprathreshold intensity is applied over the motor cortex representing the targeted muscle, the EMG activity of the muscle is arrested for a few hundred milliseconds following the MEP. This period of EMG suppression is referred to as a ‘silent period’, often defined as the time from the end of the MEP to the return of voluntary EMG activity. Most of this period is believed to be due to cortical inhibitory mechanisms of the motor cortex while spinal inhibitory mechanisms such as Renshaw inhibition are considered to contribute only to the first 50 or 60 ms of this suppression (30–32). The neuronal elements responsible for the silent period are most likely mediated by GABA-B receptors (33).

Using TMS techniques including silent periods, Classen et al. (1997) (34) investigated a syndrome after acute stroke, which involves hemiparesis, impairment of movement initiation, inability to maintain a constant force and impairment of individual finger movement, resembling motor neglect.

Interestingly, patients with this syndrome showed prolonged duration of silent period, but normal central motor conduction and MEPs in the affected side, indicating that motor disorders in these patients are caused by exaggerated inhibitory mechanisms in the motor cortex rather than by a direct corticospinal disorder. They also reported that silent period improved parallel with clinical improvement, suggesting usefulness of the silent period to evaluate clinical neurophysiology and prognosis of such motor syndromes.

The duration of the cortical silent period or the TMS-induced delay in voluntary movement can also be used to map inhibitory effects of TMS and thus assess topographic reorganization across brain regions (35).

Short-Interval Intracortical Inhibition (SICI) and Facilitation (ICF)

Exploiting TMS’s preferential activation of interneurons and transsynaptic activation of pyramidal tract cells allows for direct characterization in vivo, in humans of intracortical inhibitory and facilitatory mechanisms. Paired pulse stimulation delivered through the same magnetic coil over M1, where a suprathreshold test stimulus (TS) is preceded by a subthreshold or suprathreshold-conditioning stimulus (CS) can be used to assess local inhibitory and excitatory intracortical circuits. Combining a subthreshold conditioning stimulus with a suprathreshold test stimulus at different short (1–20 ms) interstimulus intervals through the same TMS coil, it is possible to study inhibitory and facilitatory interactions in the cortex and examine the functional integrity of intracortical neuronal structures. This methodology was first introduced by Kujirai et al. (36)(for the study of the motor cortex. The effects of the conditioning TMS on the size of test MEP depend on the stimulus intensity and the interstimulus interval. When a conditioning stimulus is set at 60–80% of the resting motor threshold, maximum inhibitory effects are found at short interstimulus intervals of 1–4ms. The maximum amount of this inhibition is usually 20–40% of the test MEP. This is termed Short-Interval Intracortical Inhibition (SICI).

Facilitatory effects of the conditioning TMS pulse with the same subthreshold intensity onto the test MEP can be observed at intervals of 7–20 ms. The magnitude of this facilitation is quite variable across subjects, from 120 to 300% of the test MEPs. This is termed Intracortical Inhibition Facilitation (ICF).

The amount of these effects can vary depending on the size of test MEPs, and thus, for this paired pulse TMS study, it is critical to maintain the relaxation of patients and adjust the size of test MEPs across trials and subjects. Previous studies, applying this method on the motor representation of various muscles, showed that these phenomena of intra-cortical inhibition and facilitation are very similar for intrinsic hand muscles, lower face, leg or proximal arm muscles, indicating that these intracortical mechanisms are similar across different motor representations. The intra-cortical inhibition and facilitation measured by this technique are induced by separate mechanisms and their effects seem to originate at the motor cortical level, but not at subcortical or spinal levels.

This paired pulse technique has also been used to examine the effects of CNS-active drugs on the human motor cortex (37). In this context, paired-pulse TMS might be useful in selecting the best-suited medication for a given patient by matching the identified abnormality in a given disorder with the effects of different pharmaceutical agents.

Paired pulse paradigm to examine interhemispheric interactions

The term, ‘paired-pulse TMS’ can also be used to refer to the application of single stimuli to two different brain regions. For instance, interhemispheric interactions and transcallosal conduction times between motor cortices in both sides can be examined, applying a conditioning suprathreshold stimulus to one motor cortex and the following test TMS pulse after a short interval (4 to 30 ms) to the other motor cortex. This paradigm was first introduced by Ferbert et al. (38) who showed that the cortical excitability of one motor cortex is decreased 7 to 15 ms after suprathreshold TMS of the opposite motor cortex. This interhemispheric interaction is influenced by the intensity of the conditioning TMS; the stronger the conditioning TMS the greater and longer the induced interhemispheric inhibition. In addition to interhemispheric inhibition, Ugawa and his colleagues have reported early interhemispheric facilitation, which can be observed at interstimulus intervals of 4–5 ms using conditioning TMS of relatively low intensity (39).

This methodology allows the investigation of interhemispheric interactions in a variety of circumstances. In the context of patients with acquired brain lesions, it is possible to assess the interhemispheric balance serially, and thus evaluate the shifts and evaluation of bi-hemispheric contributions to function as discussed above (22)

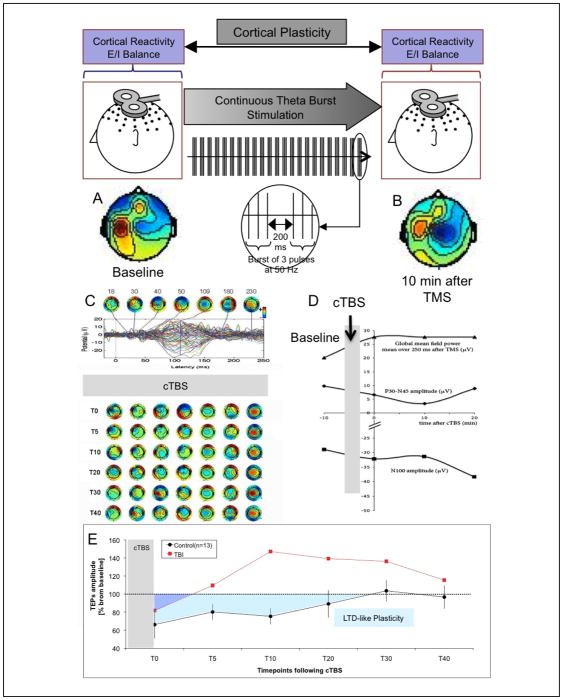

Examining cortical plasticity (Figure 2)

FIGURE 2. TMS-EEG measures of cortical reactivity and plasticity.

TMS-EEG measures of cortical reactivity (E/I balance) before (A) and after (B) continuous theta burst (cTBS) in order to assess cortical plasticity (LTD-like). EEG measures can be quantified in various ways (C, D).

Single pulse TMS can induce TMS-evoked potentials (TEP) that can be measured by EEG. When applying TMS to the motor cortex, EMG will also be used to define motor threshold and silent period. TEPs will be characterized by N100 amplitude, P30-N45 peak-to-peak amplitude and Global Field Power. Paired pulse TMS delivered at different interpulse intervals can determine various aspects of intracortical inhibition and facilitation (SICI, ICF, LICI).

Continuous theta burst stimulation (cTBS) can be applied as three pulses at 50 Hz repeated at 200 ms intervals (80% of active motor threshold intensity). Participants can receive a 47 s train of uninterrupted TBS (600 pulses). This paradigm causes suppression of post-stimulation MEPs in healthy subjects. The measures of intracortical E/I balance described above can be obtained before and then serially after cTBS (immediately after, T0, and then every 5 min following cTBS to track changes in amplitude over time). As an index of the duration of the cTBS-induced modulation of cortical response (index of plasticity), one can define for each participant the time point at which the average E/I measure returns within the 95% confidence interval of baseline and does not return to outside that interval on subsequent time point measures.

E presents pilot data in controls and a patient with a recent concussion to illustrate the value of such measures in assessing the neurophysiologic impact of acquired brain injury. Control subjects show the expected suppression following cTBS and lasting approximately 30 min (LTD-like plasticity). However, the TBI subject shows a marked suppression of LTD-like plasticity, a return to baseline following cTBS after less than 5 min, and an apparent inversion of the modulatory effects of cTBS (potentiation instead of depression). Notably, such neurophysiologic effects are demonstrable despite absent clinical deficit.

Contrasting the results of TMS on EEG before and after TBS will provide information about cortical plasticity (at the site of stimulation) but also about resulting network dynamic adaptation. Brain functional connectivity and inter-regional coordination can be directly estimated from EEGs. Analysis of network dynamics over time in patients with concussion will be compared against normal controls. For example, local, inter-region and global synchronization will be estimated, using 1) cross-correlation of EEG signals in the time domain, which will enable us to estimate temporal locking of these potentials; 2) cross-coherence in the frequency domain, assuming stationarity of the data in the analysis window; and 3) relative phase, obtained from phase time series corresponding to each EEG signal. Multivariate mixed effects regression models will be developed to compare measures of network synchronization and direct effects of stimulation across brain regions, time points, and study cohorts.

As discussed above, various measures of intracortical E/I balance are possible with TMS (40): (1) resting and active motor threshold, which is thought to measure Na/K pump dependent neuronal membrane excitability; (2) cortical silent period duration, which is believed to measure GABAB-dependent inhibition; (3) short interval intracortical inhibition (SICI), which is believed to be GABAA-dependent; (4) long interval intracortical inhibition (LICI), which is thought to be mediated by long-lasting GABAB-dependent IPSPs and activation of pre-synaptic GABAB receptors on inhibitory interneurons; and (5) intracortical facilitation (ICF), believed to be mediated by glutamatergic (NMDA-dependant) cortical interneurons. Furthermore, trains of repeated TMS pulses (rTMS) at various stimulation frequencies and patterns can induce a lasting modification of activity in the targeted brain region which can outlast the effects of the stimulation itself.

For example, it is possible to apply Theta Burst Stimulation (TBS): bursts of 3 pulses at 50 Hz repeated at intervals of 200ms. After TBS is applied to the motor cortex in an intermittent fashion (iTBS), TMS-induced potentials show increased amplitude for a period of 20–30 minutes, whereas continuous TBS (cTBS) leads to a suppression of the TMS-induced potentials for approximately the same amount of time. This modulation parallels that seen in theta burst protocols used for the induction of LTP and LTD in slice preparations and animal models. Physiologic and pharmacologic studies of TBS in humans show involvement of glutamatergic and GABAergic mediators consistent with LTP and LTD, and the effects and their time-course are consistent with the notion that TBS does indeed index mechanisms of cortical synaptic plasticity (41–43). Thus, post-TBS enhancement (following iTBS) or suppression (after cTBS) of the cortical activity is considered an index of LTP and LTD-like induction of synaptic plasticity in the targeted brain area.

Traditionally, measures of cortical E/I balance with TMS have been limited to the motor cortex. However, paradigms that integrate TMS and EEG enable characterization of E/I balance across cortical brain regions and assessment of the integrity of circuit plasticity in humans (44–47). Real-time integration of image-guided TMS with EEG can provide novel information about the integrity of cortical E/I balance, cortical plasticity and brain network dynamics longitudinally following a brain insult, and thus ultimately enable optimization of therapeutic approaches.

5. Current rehabilitation therapy approaches

Rehabilitation approaches usually train patients either to approximate for the partially lost motor function, or to substitute for its absence (by using the other limb or a device). It seems important to emphasize that any intervention may come at a cost. Thus, substitution might be detrimental to recovery as it prevents the activity dependent reorganization of the nervous system associated with the dysfunctional behavior that likely underlies improved clinical recovery.

However, restitution strategies that may result in the most long-term improvement take time and practice, and thus are not always the quickest way to improve function. There likely are critical periods following stroke for optimal relearning of particular tasks, just as there are critical optimal periods for learning during normal development (e.g. language acquisition). Thus the ideal rehabilitation therapy may evolve over the course of recovery and different strategies may be needed according to the time since the stroke. Finally prolonged and sustained interventions probably underlie the higher level of recovery seen in some patients. If so, identification of the correct intervention and sustained, persistence will be crucial, though currently most post-stroke patients receive only a few weeks to a few months of rehabilitation.

Some of the earliest observational studies of stroke patients suggested that motor disabilities were largely the result of disuse (48). This was confirmed by experiments investigating various treatment combinations for monkeys with large motor cortical lesions, including restraint of the unaffected limb, passive and active treatment. It was observed that those subjects who received active treatment, with or without restraint, recovered after only one month (49), confirming that use of the limb is essential for recovery. These observations have been replicated by subsequent researchers (50, 51) and form the basis for constraint-induced movement therapy (CIT;(52)) and forced use therapy (53). Both techniques aim to reverse the effect of learned non-use—As repeated attempts to move the affected extremity are unsuccessful, subjects gradually cease to use the limb at all (54, 55). The nonuse hypothesis was confirmed in humans who sustain brain injuries in two studies applying CIT to patients following stroke (52) and traumatic brain injury (53). In addition to confirming the hypothesis, they showed that restraining the unaffected limb, and performing intensive goal-directed movement with the affected limb resulted in increased use of the affected upper limb in real-world situations, with improvements maintained for at least one to two years.

Arguably, the greatest increases in strength and decreases in impairment following a stroke have been reported with functional task-specific physiotherapy, based on the motor relearning approach devised by Carr and Shepherd (1985) (56). This treatment is widely advocated as more effective than traditional approaches (57, 58). In fact, task trained patients have increased activation of bilateral parietal and premotor areas, possibly indicative of training-induced plasticity (59).

Another technique to increase paretic arm activity in chronic stroke patients involves bilateral arm training with a custom-built arm trainer (60). In this study, patients participated in three twenty-minute sessions per week of bilateral repetitive pushing/pulling movements for six weeks. Results revealed increased function and increased strength and active range of motion. The lack of a control group prevents any extrapolation of the specificity of this type of training. Bilateral movements likely allow facilitation of the paretic arm through spared ipsilateral CM projections, indirect ipsilateral corticospinal pathways or ipsilateral corticospinal pathways from the unaffected hemisphere (61). A series of multiple-baseline single-case experiments were conducted and the authors developed a scale to quantify kinematic characteristics during the bilateral tasks to demonstrate that during bilateral training, performance was superior than during the baseline phase where patients practiced other unilateral or active-assisted bilateral tasks. Again, the lack of clear evidence that this approach results in functional improvements that are superior to conventional physiotherapy limits the clinical relevance of these studies.

Achieving maximal post-stroke recovery strongly depends on the quality of rehabilitation. As recovery processes are reflected and adjusted by cortical reorganization, it is important to guide these plastic changes to restore natural movement sequences. Therefore, physiotherapists have a great impact on the outcome of rehabilitative training. Yet there are three limiting factors in this context: (1.) a physiotherapist has limited time to devote to a given patient; (2.) movements practiced under the survey of physiotherapists are generally not completely optimized to an individual patient; (3.) treatment is not standardized and therefore effects are heterogeneous. To ameliorate these problems, robotic devices such as the LOKOMAT and ARMIN (for low and upper extremities respectively) were developed. They are individualized to suit each patient’s needs. The robots are “patient – cooperative” - controllers that take into account the patient’s intention and efforts rather than imposing any predefined movement. From feedback measurement, the robot knows the amount of force that patient can produce, and can support the patient only as much as is needed to complete the movement. With this system, patients can repeat movements more often and more precisely than with classical physiotherapy. In addition, audiovisual displays can present a virtual environment and let the patient perform different motor tasks and activities of daily life. The combination of individualized support and repetitive training increases motivation and has a net positive affect on rehabilitation (62).

A common characteristic of behavioral rehabilitation approaches, with or without technology support, is that functional gains are usually associated with the amount of cortical excitability within the lesioned and non-lesioned motor related cortical areas. For example, Liepert et al (1999) showed that CI therapy leads to an increase of motor mapping area size as indexed by TMS, supporting the notion that CIT leads to an increase in corticospinal excitability in the affected primary motor cortex (63). In another example, Jang et al. (2003) used fMRI to demonstrate increased activation in the affected hemisphere, and decreased activation of the unaffected hemisphere, in a group of chronic stroke patients undergoing four weeks of task-oriented training (64). Thus interventions that can enhance cortical plasticity may enhance the effects of behavioral rehabilitation approaches. This is one context where non-invasive brain stimulation techniques are appealing. One potential approach for instance is to combine CI therapy with cortical stimulation to maximize decrease in activation in the unaffected hemisphere and increase activity in the lesioned hemisphere. Although the studies are still preliminary and some of them uncontrolled, the results from these studies are important in guiding clinicians to the underlying mechanisms that may ultimately underlie most successful new approaches.

6. Novel approaches by combining interventions to harness brain plasticity mechanisms

Repeated motions are well known to reinforce plasticity in the motor cortex and can promote recovery. However, simply doing more movements may not be sufficient. For example, adding fifteen-minute sessions of repetitive wrist and hand exercises against increasing loads twice daily to the usual care regimen for subacute stroke patients resulted in increased grip strength and peak acceleration in the paretic hand over four weeks. This was not observed in the control group who were given only transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (65). Muellbacher et al. (2002) trained patients to perform repetitive pinching movements between the paretic index finger and thumb over several weeks until they became proficient. At this stage, the upper arm was anesthetized with the aim of enhancing the effects of motor practice by depriving the motor cortex of sensory inputs. This led to greater improvements in pinch force and acceleration than exercises alone (66). However, the potential impact of repetitive simple movements on rehabilitation is unclear as neither of these studies reported sustained improved function. Similarly, it is unclear how and whether simple repetitive movements can lead to carry-over effects to other abilities and functions.

Techniques that engage and leverage cognitive demands in conjunction with motor tasks also promote cortical reorganization. These include tracking a moving target across a screen (67), computerized arm training with a robotic arm trainer either on the affected arm alone (68–71) or bilaterally (72, 73), use of a “virtual reality” computer game (74), and a form of task-specific therapy known as arm ability training (75, 76). In general these studies have involved small sample sizes, lack appropriate control groups, and require complex training and/or equipment, and thus are not commonly used in mainstream rehabilitation.

An area of research that has gathered increasing support is the use of electrical muscular and peripheral nerve stimulation in stroke rehabilitation. Electrical stimulation alone of the wrist and finger extensors enhances upper limb motor recovery in acute stroke patients (77) and increases function compared with controls (78). In addition peripheral somatosensory stimulation, in the absence of muscle contraction, also influences cortical reorganization and may be beneficial for the rehabilitation of chronic stroke patients. When tested in a randomized crossover design (79), pinch grip strength increased following a two-hour session of median nerve stimulation but not control stimulation, and patients reported improved ability to write and hold objects. This type of stimulation increased the amount of use-dependent plasticity seen in chronic stroke patients when measured with TMS (80), supporting the hypothesis that somatosensory input is able to drive plastic changes in the motor cortex even in stroke-damaged brains (80, 81) (82). A single session of peripheral nerve stimulation improved the ability of stroke patients to complete the Jebsen-Taylor Functional Hand Test (83). However no longitudinal studies have yet investigated the effects of repeated application of somatosensory stimulation in stroke patients. Such studies are interesting and worth pursuing, even though, it the situation is likely complex as illustrated by past failed attempts of start-up companies combining peripheral stimulation with rehabilitation to succeed in the competitive market of new interventions.

It may be possible to maximize the effects of peripheral electrical stimulation by combining it with brain stimulation. In fact, paired associative stimulation aims to maximize potential gains by modulating excitability of the motor cortex through both central and peripheral inputs. This dual stimulation likely operates similarly to LTP mechanisms in animal experiments (84, 85). In a recent study, paired stimulation was applied daily for four weeks to increase the excitability of the corticospinal projections to paretic ankle dorsiflexors and evertors in a group of chronic stroke patients (86). In some subjects, this induced significant improvements in the gait cadence, stride length and time-to-heel-strike, even in the absence of gait training. Increased MEP amplitude and maximal voluntary contraction force was demonstrated in five of the nine subjects, but there was no overall group effect in this small sample. Although this study lacked a control group, it suggests that in some subjects the application of repeated sessions of dual stimulation can result in plastic changes in the motor cortex and lead to sustainable functional improvements.

Just brain stimulation alone appears to be promising as an intervention to enhance the effects of training. Bütefisch et al. (2004) demonstrated that among healthy controls, TMS of the motor cortex combined with motor training enhances human cortical plasticity leading to better task performance. The study found that depending on the intervention, plastic changes could last from 20 to greater than 60 minutes. It also demonstrated that the effect of TMS sessions on plasticity may depend on whether stimulation is applied synchronous or asynchronous with movements. In addition, the results show the impact of TMS targeting the ipsilateral M1 (cortex not involved in movement) versus such targeting of the contralateral M1 (directly implicated in movements). In spite of limited, short training sessions, TMS can induce motor cortical plasticity, and enhance and prolong the effects of motor training. As discussed above, stroke alters interhemispheric excitability balance (22) and considerations of the time course of changes following an insult suggest that down-regulation of the unaffected M1, rather than modulation of the lesioned hemisphere, may sometimes have a great impact on recovery. It is important to remember in developing a TMS protocol for rehabilitation that the ipsi-and contralesional hemispheres differ in their functions, and that the timing of stimulation, relative to motor tasks, can greatly affect any functional gains.

7. TMS in Stroke

Tables 1 and 2 provide a summary of rTMS trials of stroke rehabilitation. Favorable neurological effects have been reported after high-frequency rTMS in patients with stroke (87, 88) (26). These studies found modest improvements in grip strength, range of motion, and pegboard performance up to 1 week after rTMS, and that stimulation up to 20Hz were tolerated. (87). High frequency rTMS can also be a useful adjunct to conventional therapy for dysphagia after stroke (89). Because standard rTMS protocols exhibit short post-stimulus effects, novel protocols such as theta burst stimulation (TBS) may further enhance the effectiveness of rTMS. However, cautious research is necessary as TBS protocols of the human prefrontal cortex seem to be safe only in healthy subjects (90).

Table 1.

Low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

| Method of stimulation | Area of Stimulation | Number of Patients | Stroke duration | Study Design | Outcome Measure (Improvement of Motor Performance of the Affected Hand) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Hz rTMS at 100% RMT* | M1 of the unaffected hemisphere | 10 | ≥ 12 months | Single-blinded crossover, sham- controlled | Simple and choice reaction times Purdue Pegboard Test |

Mansur et al, 2005 (23) |

| 1-Hz rTMS at 100% RMT* unaffected hemisphere | M1 of the | 15 | 1–11 years | Single-blinded, longitudinal, randomized, sham-controlled | Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function test choice reaction times Purdue Pegboard test |

Fregni et al, 2006 (24) |

| 1-Hz rTMS at 100% RMT* | M1 of the unaffected hemisphere | 1 | 23–107 months | Double-blind, crossover, single- case study | Thumb and finger movements | Boggio et al, 2006 (91) |

| 1-Hz rTMS at 100% RMT* | M1 of the unaffected hemisphere | 15 | 1–4 months | Double-blinded, crossover, sham- controlled | Index finger tapping | Nowak et al, 2008 (92) |

| 1-Hz rTMS at 90% RMT* | M1 of the unaffected hemisphere | 20 | 7–121 months | Double-blinded, crossover, sham- controlled | Pinch acceleration peak pinch force | Takeuchi et al, 2005 (25) |

| 1-Hz rTMS at 100% RMT* | M1 of the unaffected hemisphere | 12 | 1–15 months | Double-blinded, crossover, sham- controlled | Grasping and lifting an object | Dafotakis et al, 2008 (93) |

| 1-Hz rTMS at 90% RMT* | M1 of the unaffected hemisphere | 12 | <14 days | Double-blinded, crossover, sham- controlled | Nine Hole Peg Test | Leipert et al, 1999 |

Table 2.

High frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

| Method of stimulation | Area of Stimulation | Number of Patients | Stroke duration | Study Design | Outcome Measure (Improvement of Motor Performance of the Affected Hand) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50-Hz rTMS at 80% RMT | M1 of the affected hemisphere | 6 | 12–108 months | Single-blinded crossover, sham- controlled | Grip speed and grip force | Talelli et al, 2007 (94) |

| 10-Hz rTMS at 80% RMT | M1 of the affected hemisphere | 15 | 4–41 months | Single-blinded crossover, sham- controlled | Movement accuracy | Kim et al, 2006 (88) |

| 10-Hz rTMS at 90% | M1 of the affected hemisphere | 19 | 4 years | Double-blinded, longitudinal, randomized, sham-controlled (1:1, sham-real rTMS) | Wolf Motor Function Test and Motor Activity Log | Malcolm et al, 2007 (95) |

| 20-Hz rTMS at 90% RMT | M1 of the affected hemisphere | 12 | >10 weeks | Non-controlled longitudinal | Fugl-Meyer score; grip strength; Nine Hole Peg Test | Yozbatiram et al, 2009 (87) |

On the other hand, low-frequency rTMS (1Hz range) decreases cortical excitability (11) and has been applied to the unaffected motor cortex to decrease hyperexcitability in chronic stroke patients as initially shown in a population of subacute subjects (23) and subsequently confirmed in other studies (24, 25). A single session of 1 Hz rTMS decreased cortical excitability and transcortical inhibition, and led to a short-lasting increases in pinch acceleration of the paretic hand, while no change was seen following sham stimulation (25). In addition, 1Hz rTMS of the unaffected motor cortex leads to an increase in the excitability of the affected motor cortex (24).

In contrast, a recent study applied 3 Hz rTMS in conjunction with routine rehabilitation in acute stroke patients, and found that real, but not sham, stimulation decreased disability over a two-week period, although there was no increase in motor cortical excitability as predicted (26). These studies suggest that decreasing inhibition in the affected M1, and perhaps other motor related areas such as the dorsal premotor cortex, can unmask pre-existing, functionally latent neural connections around the lesion, and contribute to cortical reorganization (25). A case study highlighting the functional gains made after three weeks of motor cortex stimulation via implanted epidural electrodes during structured occupational therapy sessions adds further support to the hypothesis that cortical stimulation could contribute to recovery of motor function in stroke patients (96).

Contralesional neglect after stroke is not due to the lesion itself but primarily due to the resulting shifts in bi-hemispheric distributed neural network activity, which includes hyperactivity of the intact hemisphere. In this setting, 1 Hz rTMS of the unaffected frontal or parietal lobe to suppress excitability of the intact hemisphere can improve contralesional visuospatial neglect after stroke (97). Naeser and co-workers (98) have shown that patients with Broca’s aphasia may improve their naming ability after 1 Hz rTMS of the right Brodmann’s area 45 that is supposed to be over activated in patients with unrecovered, non-fluent aphasia. Therefore, rTMS to contralesional hemispheres may modulate maladaptive plastic changes and offer valuable future clinical interventions.

Even though the duration of the aftereffects is frequently thought to be relatively short-lived—lasting minutes to hours—there might be methods of extracting even of longer-lasting effects. A second train of rTMS applied 24 hours after the first one to the motor cortex has been shown to have a more robust effect on corticospinal excitability (Maeda et al., 2002). However, to date, there has been no systematic study of the implications of these findings in the context of brain injury. In addition, it may be possible to optimize the impact of the stimulation itself. The effects that strokes can have on perturbing the currents induced by TMS are insufficiently studied, despite the well-known fact that numerous neurophysiologic changes after a stroke can alter the brain’s electrical response properties. A computer-based model concluded that the distribution of TMS-induced currents can be severely disrupted by tissue changes associated with a stroke lesion (99). Individualized modeling of the TMS-induced currents may thus possibly improve the efficacy of TMS in neurorehabilitation.

8. TMS combined with robotics and pharmacotherapy

Based on recent evidence showing the beneficial effects of robotics and also pharmacotherapy in improving function and also inducing plastic changes, the combination of TMS with these therapies may offer synergistic advantages (100–102). Initially, TMS can be a valuable measurement tool to assess the impact of robotics (103) or neuropharmacology (37). Furthermore, combination treatment offers promising therapeutic advantages.

Strategies such as CIMT and weight-bearing therapy by using robotics, combined with stimulation techniques such as tDCS or rTMS have shown promise within the literature, but not always consistent results (104). These combined strategies appear to increase the efficacies of standard treatments by either increasing their accuracy (with respect to physical therapy), or by modulating the cortical excitability, thus potentially increasing neural plasticity (102, 103, 105, 106).

The ease of application, and the mechanisms of action of tDCS in enhancing motor learning without disrupting brain activity make it particularly suitable for combination with robotic training (107). Although the number of studies is still small and all of them are preliminary, this seems an important area of future research (102).

Another potential area of future development is the combination of TMS and tDCS with pharmacotherapy for stroke recovery. Several studies have shown that pharmacological agents can modulate activity-dependent plasticity in animal models and have recently been tested for the treatment of motor recovery after stroke (108–110). The main drugs tested are amphetamines, selective norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors, dopamine, dopamine agonists, cholinergic substances, serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor. Although combination of these drugs with rTMS or tDCS might be complex, it may offer opportunity to increase their effects if properly combined.

9. Limitations on the usefulness of brain stimulation as treatment in neurorehabilitation

Despite these promising results, some limitations of TMS or tDCS need to be noted. Critically, after stroke, there is a change in the local anatomy and the lesion evolves into scar tissue and, particularly in the case of cortical damage, larger cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) spaces. Because the conductance of CSF is 4 to 10 times higher than that of brain tissue, scar formation and larger CSF spaces modify the geometry and magnitude of the electric field induced by rTMS, and stimulation of the lesioned hemisphere can become difficult to predict unless careful modeling is done (111).

While only very few of the very large number of possible combinations of stimulation parameters (frequency, intensity, train duration, etc.) have been tested experimentally, the issue of safety places stringent boundaries stimulation parameters that can be used in human studies (112, 113). Therefore, careful safety studies are critically needed, and animal models are most desirable to gain further mechanistic insights.

10. Conclusion

Mechanisms of recovery from acquired brain insult, including stroke, are still poorly understood. Owing to the belief that functional connections among cortical and subcortical structures are essentially ‘hard wired’ and static, it was assumed that lesions in particular parts of the brain would result in permanent loss of function (114). This perspective meant that efforts to rehabilitate stroke patients were doomed to fail. Yet on the other hand, this view suggested that the behavioral correlates of specific cortical and subcortical regions could be determined in a straightforward manner by comparing the performance of normal subjects with patients who sustained lesions in particular structures. For many years, clinicians and researchers accepted this tradeoff between explanatory power and optimism regarding recovery. As time passed, however, it has become clear that return of function often takes place. Because such improvement was inconsistent with the localizationist perspective, later theorists proposed ‘parallel processing mechanisms’ that assume responsibility for the functions of damaged areas (114, 115). However even these newer, refined, explanations of restored motor function oversimplify the complexity of basic brain processes (114). Given the evidence against strict cerebral localization, there has been a gradual paradigm shift toward more integrated views of the brain. Such theories suggest that that behavior (including motor responses) reflect the interactive functioning of diverse cortical regions that are linked by intricate fiber networks.

Applied to the process of motor recovery following stroke, one may consider that the adult human brain contains multiple somatotopically-organized pathways that have the potential to transmit impulses to trunk and limb musculature when normal functioning is compromised. In addition, certain cortical regions demonstrate an intrinsic ability to assume responsibility for novel functions when customary circuits are interrupted. Although the cellular processes underlying these changes have not been fully explained, one promising line of research suggests that the loss of inhibitory influences leads to an expansion of the receptive fields of some neurons. This expansion allows previously dormant paths to conduct impulses to their final destinations. In general these studies have involved small sample sizes, lack appropriate control groups, and require complex training and/or equipment, and thus are not commonly used in mainstream rehabilitation. Overall, though, the studies discussed provide some encouraging information supporting the proposal that NIBS might optimize the effect of standard physical therapy under certain circumstances. Beyond the obvious need for further clinical trials to corroborate the validity of this approach, attention must be directed to understanding the optimal way to combine other behavioral interventions with NIBS. Obvious next steps are to determine the parameters required to optimize the conditioning effects of NIBS on motor therapy, as well as the exact temporal window during which NIBS can be delivered in order to modulate brain plasticity and enhance the effects of the motor training.

Acknowledgments

Work on this study was supported in part by the Berenson-Allen Foundation, the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (Harvard Catalyst; NCRR-NIH UL1 RR025758), and a K24-RR018875 award from the National Institutes of Health to APL; and from American Heart Association (AHA # 0735535T) and CIMIT to F.F. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Andlin-Sobocki P, Jonsson B, Wittchen HU, Olesen J. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2005 Jun;12( Suppl 1):1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossini PM, Calautti C, Pauri F, Baron JC. Post-stroke plastic reorganisation in the adult brain. Lancet Neurol. 2003 Aug;2(8):493–502. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00485-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seitz RJ, Azari NP, Knorr U, Binkofski F, Herzog H, Freund HJ. The role of diaschisis in stroke recovery. Stroke. 1999 Sep;30(9):1844–1850. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.9.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pascual-Leone A, Amedi A, Fregni F, Merabet LB. The plastic human brain cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:377–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dijkhuizen RM, Asahi M, Wu O, Rosen BR, Lo EH. Delayed rt-PA treatment in a rat embolic stroke model: diagnosis and prognosis of ischemic injury and hemorrhagic transformation with magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001 Aug;21(8):964–971. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200108000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dijkhuizen RM, Ren J, Mandeville JB, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of reorganization in rat brain after stroke. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Oct 23;98(22):12766–12771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231235598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Rouiller EM. Mechanisms of recovery of dexterity following unilateral lesion of the sensorimotor cortex in adult monkeys. Exp Brain Res. 1999 Sep;128(1–2):149–159. doi: 10.1007/s002210050830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feydy A, Carlier R, Roby-Brami A, et al. Longitudinal study of motor recovery after stroke: recruitment and focusing of brain activation. Stroke. 2002 Jun;33(6):1610–1617. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000017100.68294.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barker AT, Jalinous R, Freeston IL. Non-invasive magnetic stimulation of human motor cortex. Lancet. 1985 May 11;1(8437):1106–1107. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaghi S, Acar M, Hultgren B, Boggio PS, Fregni F. Noninvasive brain stimulation with low-intensity electrical currents: putative mechanisms of action for direct and alternating current stimulation. Neuroscientist. Jun;16(3):285–307. doi: 10.1177/1073858409336227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maeda F, Keenan JP, Tormos JM, Topka H, Pascual-Leone A. Modulation of corticospinal excitability by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000 May;111(5):800–805. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(99)00323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. Technology insight: noninvasive brain stimulation in neurology-perspectives on the therapeutic potential of rTMS and tDCS. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007 Jul;3(7):383–393. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pascual-Leone A, Valls-Sole J, Wassermann EM, Hallett M. Responses to rapid-rate transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human motor cortex. Brain. 1994 Aug;117( Pt 4):847–858. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.4.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hannula H, Ylioja S, Pertovaara A, et al. Somatotopic blocking of sensation with navigated transcranial magnetic stimulation of the primary somatosensory cortex. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005 Oct;26(2):100–109. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt S, Cichy RM, Kraft A, Brocke J, Irlbacher K, Brandt SA. An initial transient-state and reliable measures of corticospinal excitability in TMS studies. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009 May;120(5):987–993. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.02.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gugino LD, Romero JR, Aglio L, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation coregistered with MRI: a comparison of a guided versus blind stimulation technique and its effect on evoked compound muscle action potentials. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001 Oct;112(10):1781–1792. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00633-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Julkunen P, Saisanen L, Danner N, et al. Comparison of navigated and non-navigated transcranial magnetic stimulation for motor cortex mapping, motor threshold and motor evoked potentials. Neuroimage. 2009 Feb 1;44(3):790–795. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liepert J, Graef S, Uhde I, Leidner O, Weiller C. Training-induced changes of motor cortex representations in stroke patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 2000 May;101(5):321–326. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2000.90337a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hallett M, Wassermann EM, Pascual-Leone A, Valls-Sole J. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. The International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl. 1999;52:105–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maeda F, Keenan JP, Tormos JM, Topka H, Pascual-Leone A. Interindividual variability of the modulatory effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on cortical excitability. Exp Brain Res. 2000 Aug;133(4):425–430. doi: 10.1007/s002210000432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pascual-Leone A, Tarazona F, Keenan J, Tormos JM, Hamilton R, Catala MD. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and neuroplasticity. Neuropsychologia. 1999 Feb;37(2):207–217. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(98)00095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murase N, Duque J, Mazzocchio R, Cohen LG. Influence of interhemispheric interactions on motor function in chronic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2004 Mar;55(3):400–409. doi: 10.1002/ana.10848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mansur CG, Fregni F, Boggio PS, et al. A sham stimulation-controlled trial of rTMS of the unaffected hemisphere in stroke patients. Neurology. 2005 May 24;64(10):1802–1804. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000161839.38079.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fregni F, Boggio PS, Valle AC, et al. A sham-controlled trial of a 5-day course of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the unaffected hemisphere in stroke patients. Stroke. 2006 Aug;37(8):2115–2122. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000231390.58967.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takeuchi N, Chuma T, Matsuo Y, Watanabe I, Ikoma K. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of contralesional primary motor cortex improves hand function after stroke. Stroke. 2005 Dec;36(12):2681–2686. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000189658.51972.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khedr EM, Ahmed MA, Fathy N, Rothwell JC. Therapeutic trial of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation after acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2005 Aug 9;65(3):466–468. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173067.84247.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossini PM, Barker AT, Berardelli A, et al. Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord and roots: basic principles and procedures for routine clinical application. Report of an IFCN committee. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994 Aug;91(2):79–92. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(94)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magistris MR, Rosler KM, Truffert A, Landis T, Hess CW. A clinical study of motor evoked potentials using a triple stimulation technique. Brain. 1999 Feb;122( Pt 2):265–279. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magistris MR, Rosler KM, Truffert A, Myers JP. Transcranial stimulation excites virtually all motor neurons supplying the target muscle. A demonstration and a method improving the study of motor evoked potentials. Brain. 1998 Mar;121( Pt 3):437–450. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuhr P, Agostino R, Hallett M. Spinal motor neuron excitability during the silent period after cortical stimulation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1991 Aug;81(4):257–262. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(91)90011-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen R, Lozano AM, Ashby P. Mechanism of the silent period following transcranial magnetic stimulation. Evidence from epidural recordings. Exp Brain Res. 1999 Oct;128(4):539–542. doi: 10.1007/s002210050878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brasil-Neto JP, Cammarota A, Valls-Sole J, Pascual-Leone A, Hallett M, Cohen LG. Role of intracortical mechanisms in the late part of the silent period to transcranial stimulation of the human motor cortex. Acta Neurol Scand. 1995 Nov;92(5):383–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1995.tb00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Werhahn KJ, Kunesch E, Noachtar S, Benecke R, Classen J. Differential effects on motorcortical inhibition induced by blockade of GABA uptake in humans. J Physiol. 1999 Jun 1;517( Pt 2):591–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0591t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Classen J, Schnitzler A, Binkofski F, et al. The motor syndrome associated with exaggerated inhibition within the primary motor cortex of patients with hemiparetic. Brain. 1997 Apr;120( Pt 4):605–619. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thickbroom GW, Stell R, Mastaglia FL. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human frontal eye field. J Neurol Sci. 1996 Dec;144(1–2):114–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(96)00194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kujirai T, Caramia MD, Rothwell JC, et al. Corticocortical inhibition in human motor cortex. J Physiol. 1993 Nov;471:501–519. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ziemann U, Lonnecker S, Steinhoff BJ, Paulus W. Effects of antiepileptic drugs on motor cortex excitability in humans: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Ann Neurol. 1996 Sep;40(3):367–378. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferbert A, Priori A, Rothwell JC, Day BL, Colebatch JG, Marsden CD. Interhemispheric inhibition of the human motor cortex. J Physiol. 1992;453:525–546. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanajima R, Ugawa Y, Machii K, et al. Interhemispheric facilitation of the hand motor area in humans. J Physiol. 2001 Mar 15;531(Pt 3):849–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0849h.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobayashi M, Pascual-Leone A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in neurology. Lancet Neurol. 2003 Mar;2(3):145–156. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hallett M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: a primer. Neuron. 2007 Jul 19;55(2):187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thickbroom GW. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and synaptic plasticity: experimental framework and human models. Exp Brain Res. 2007 Jul;180(4):583–593. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-0991-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Di Lazzaro V, Profice P, Pilato F, Dileone M, Oliviero A, Ziemann U. The effects of motor cortex rTMS on corticospinal descending activity. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;121(4):464–473. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thut G, Ives JR, Kampmann F, Pastor MA, Pascual-Leone A. A new device and protocol for combining TMS and online recordings of EEG and evoked potentials. J Neurosci Methods. 2005 Feb 15;141(2):207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thut G, Pascual-Leone A. A review of combined TMS-EEG studies to characterize lasting effects of repetitive TMS and assess their usefulness in cognitive and clinical neuroscience. Brain Topogr. Jan;22(4):219–232. doi: 10.1007/s10548-009-0115-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thut G, Pascual-Leone A. Integrating TMS with EEG: How and what for? Brain Topogr. Jan;22(4):215–218. doi: 10.1007/s10548-009-0128-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ives JR, Rotenberg A, Poma R, Thut G, Pascual-Leone A. Electroencephalographic recording during transcranial magnetic stimulation in humans and animals. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006 Aug;117(8):1870–1875. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Franz SI, Scheetz ME, Wilson AA. The possibility of recovery of motor function in long-standing hemiplegia. JAMA. 1915;65:2150–2154. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogden R, Franz SI. On cerebral motor control: The recovery from experimentally produced hemiplegia. Psychobiol. 1917;1:33–50. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taub E, Crago JE, Burgio LD, et al. An operant approach to rehabilitation medicine: overcoming learned nonuse by shaping. J Exp Anal Behav. 1994 Mar;61(2):281–293. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1994.61-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nudo RJ, Milliken GW. Reorganization of movement representations in primary motor cortex following focal ischemic infarcts in adult squirrel monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 1996 May;75(5):2144–2149. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.5.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taub E, Uswatte G, Pidikiti R. Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy: a new family of techniques with broad application to physical rehabilitation--a clinical review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1999 Jul;36(3):237–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolf SL, Lecraw DE, Barton LA, Jann BB. Forced use of hemiplegic upper extremities to reverse the effect of learned nonuse among chronic stroke and head-injured patients. Exp Neurol. 1989 May;104(2):125–132. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(89)80005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Knapp HD, Taub E, Berman AJ. Effect of deafferentiation on a conditioned avoidance response. Science. 1958;128:842–843. doi: 10.1126/science.128.3328.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Twitchell TE. Sensory factors in purposive movement. J Neurophysiol. 1954 May;17(3):239–252. doi: 10.1152/jn.1954.17.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carr JH, Shepherd RB, Nordholm L, Lynne D. Investigation of a new motor assessment scale for stroke patients. Phys Ther. 1985 Feb;65(2):175–180. doi: 10.1093/ptj/65.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bayona NA, Bitensky J, Salter K, Teasell R. The role of task-specific training in rehabilitation therapies. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2005 Summer;12(3):58–65. doi: 10.1310/BQM5-6YGB-MVJ5-WVCR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Winstein CJ, Rose DK, Tan SM, Lewthwaite R, Chui HC, Azen SP. A randomized controlled comparison of upper-extremity rehabilitation strategies in acute stroke: A pilot study of immediate and long-term outcomes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004 Apr;85(4):620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nelles G, Esser J, Eckstein A, Tiede A, Gerhard H, Diener HC. Compensatory visual field training for patients with hemianopia after stroke. Neurosci Lett. 2001 Jun 29;306(3):189–192. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01907-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Whitall J, McCombe Waller S, Silver KH, Macko RF. Repetitive bilateral arm training with rhythmic auditory cueing improves motor function in chronic hemiparetic stroke. Stroke. 2000 Oct;31(10):2390–2395. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mudie MH, Matyas TA. Can simultaneous bilateral movement involve the undamaged hemisphere in reconstruction of neural networks damaged by stroke? Disabil Rehabil. 2000 Jan 10–20;22(1–2):23–37. doi: 10.1080/096382800297097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Riener R, Lunenburger L, Colombo G. Cooperative strategies for robot-aided gait neuro-rehabilitation. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2004;7:4822–4824. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2004.1404334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liepert J. TMS mapping studies in peripheral and central lesions. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl. 1999;51:151–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jang SH, Kim YH, Cho SH, Lee JH, Park JW, Kwon YH. Cortical reorganization induced by task-oriented training in chronic hemiplegic stroke patients. Neuroreport. 2003 Jan 20;14(1):137–141. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200301200-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Butefisch C, Hummelsheim H, Denzler P, Mauritz KH. Repetitive training of isolated movements improves the outcome of motor rehabilitation of the centrally paretic hand. J Neurol Sci. 1995 May;130(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00003-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Muellbacher W, Richards C, Ziemann U, et al. Improving hand function in chronic stroke. Arch Neurol. 2002 Aug;59(8):1278–1282. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.8.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carey JR, Kimberley TJ, Lewis SM, et al. Analysis of fMRI and finger tracking training in subjects with chronic stroke. Brain. 2002 Apr;125(Pt 4):773–788. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aisen ML, Krebs HI, Hogan N, McDowell F, Volpe BT. The effect of robot-assisted therapy and rehabilitative training on motor recovery following stroke. Arch Neurol. 1997 Apr;54(4):443–446. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550160075019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Volpe BT, Krebs HI, Hogan N, Edelsteinn L, Diels CM, Aisen ML. Robot training enhanced motor outcome in patients with stroke maintained over 3 years. Neurology. 1999 Nov 10;53(8):1874–1876. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.8.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fasoli SE, Krebs HI, Hogan N. Robotic technology and stroke rehabilitation: translating research into practice. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2004 Fall;11(4):11–19. doi: 10.1310/G8XB-VM23-1TK7-PWQU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fasoli SE, Krebs HI, Stein J, Frontera WR, Hogan N. Effects of robotic therapy on motor impairment and recovery in chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003 Apr;84(4):477–482. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lum PS, Burgar CG, Shor PC, Majmundar M, Van der Loos M. Robot-assisted movement training compared with conventional therapy techniques for the rehabilitation of upper-limb motor function after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002 Jul;83(7):952–959. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.33101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]