1.1 Introduction

Since the controversial yet groundbreaking experiments by John Olney on glutamate-induced excitotoxicity, the retina has prevailed as a useful model to address significant questions in neurobiology. The retina which is derived from neural ectoderm, and its surrounding structures which are derived from the neural crest, are essential for vision. Given the vital nature of these specialized tissues, a multi-checkpoint blood-barrier has evolved to prohibit the entry of proinfl ammatory immune cells into the parenchyma. However, like the central nervous system, the retina remains under constant immune surveillance by its resident cells, including microglia, astrocytes, ganglion cells, pigmented epithelium, and endothelium capable of triggering innate immune response via Toll-like receptors (TLRs).

1.2 TLRs and Neuroimmunity

TLRs are type I transmembrane proteins that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP) resulting in the initiation of the innate immune response pathways (Medzhitov and Janeway 2000). To date, 13 TLRs have been identified in humans and mice that bind with specific PAMP (Oda and Kitano 2006). TLRs are critical signal transducers for PAMP detection and are required to activate the intracellular interferon (IFN) mediated immune pathways. Viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) has long been known to induce type I IFN genes, although it is only recently that this mechanism was shown to be partly mediated by specific recognition of dsRNA through TLR3 (Alexopoulou et al. 2001). Signal translation is achieved via coupling with various cytosolic adaptor molecules that contain a Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain. One such adaptor, myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) was thought to be ubiquitous among TLRs, but data on TLR3 activation by dsRNA suggested the critical involvement of another adaptor called Toll/IL-1 domain-containing adapter inducing IFN-β (TRIF) (Yamamoto et al. 2003). TRIF relays TLR3 signaling through a kinase cascade resulting in nuclear translocation of NF-κB and IFN regulatory factor-3 (IRF-3), induction of IFN-related genes, and subsequent expression of infl ammatory cytokines and pro-apoptotic mediators (Hoebe et al. 2003; Meylan et al. 2004). In addition to TLR3, known dsRNA receptors include the RNA-binding protein kinase (PKR) and retinoic acid inducible gene I (RIG-I) (Sledz et al. 2003).

In many neurodegenerative pathologies including Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and age-related macular degeneration (AMD), viruses have been speculated to play a key role in disease onset and progression (Margolis et al. 2004; Ringheim and Conant 2004). Several TLRs, including TLR 2–9, are expressed on microglia and astrocytes (Jack et al. 2005), and a multitude of neurocytotoxic effects have been observed with TLR3 activation including neurite growth cone collapse (Cameron et al. 2007), exacerbation of chronic neurodegeneration (Field et al. 2010), and negative regulation of neural progenitor cell proliferation (Lathia et al. 2008). In our studies, we observed TLR3 induced neurodegeneration in the retina which has generated considerable interest in targeting this pathway for the treatment of AMD.

1.3 TLRs and Age-Related Macular Degeneration

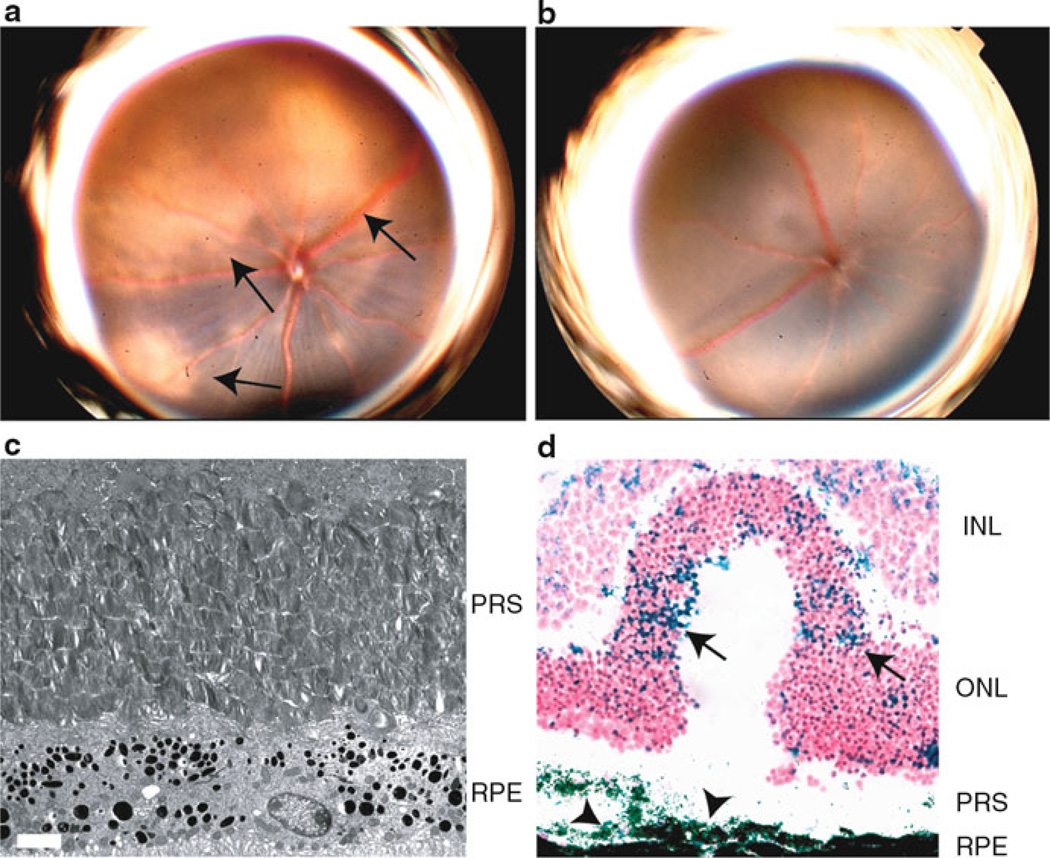

The natural history of the AMD is uniquely characterized by advancement to either geographic atrophy (GA) of the macula or choroidal neovascularization (CNV). While the pathogenesis of CNV has been well studied in a surrogate laser injury animal model leading to the development of clinically proven therapeutics, there is a paucity of data on the cellular events leading to GA due to the lack of a suitable animal model. In a world-wide collaboration, a genetic association between GA and a hypomorphic single nucleotide polymorphism in the TLR3 gene called L412F was recently identified (Yang et al. 2008). The study suggested that carriers of the mutation are protected from the development of GA suggesting that TLR3 activation may be deleterious to the macula. In order to evaluate the functionality pathway in vivo, intraocular injections of a potent TLR3 agonist, poly (I:C), were performed in wild-type and TLR3-deficient mice. Serial retinal imaging over a 2-week period demonstrated a progressive accumulation of discrete areas of hypopigmentation in wild-type mice similar to the appearance of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) loss associated with GA (Fig. 1.1). In agreement with a previous study (Kumar et al. 2004), we found abundant TLR3 expression in RPE cells in both human and mouse suggesting that this cell may be directly activated by dsRNA. Moreover, in our most recent unpublished studies, we observed increased concentrations of dsRNA in GA eyes compared to age-matched controls and are currently performing sequencing studies to determine its origin.

Fig. 1.1.

Dilated fundoscopic examination of wild-type mice (a) 2 weeks after treatment with intraocular poly (I:C) (2 µg) revealed confluent areas of hypo- and complete depigmentation (arrows) suggestive of RPE loss whereas TLR3-deficient mice did not (b). Ultrastructural analysis showed disorganized photoreceptor segments (PRS) and vacuolization of the RPE layer, a sign of autophagy that occurs during cell death (c) (scale bar = 2 µm). Forty-eight hours after treatment, severe disturbances in retinal morphology are evident along with significantly increased apoptotic nuclei (TUNEL + blue, nuclei in red) in the RPE (arrowheads) and nuclear layers (INL, ONL) (arrows) of wild-type treated retinas (d) (scale bar = 10 µm)

On histologic and ultrastructural analyses, photoreceptor arrays and the RPE monolayer were severely disrupted. RPE cell analyses over a 72-h period after poly (I:C) injection revealed a precipitous drop in viable cell numbers in wild-type mice compared to TLR3-deficient mice. Given that TLR3 activation may act through Fas-associated death domains (FADD) to induce caspase-dependent apoptosis (Balachandran et al. 2004), we evaluated the extent of TLR3-induced apoptosis in our model. At 48 h after treatment in wild-type mice, almost 40% of cells in the RPE and neural retina were undergoing apoptosis as measured by TUNEL, and a fraction of those were also positive for cleaved caspase-3 signifying some level of dependence on this pathway. In vitro, primary human RPE isolates exhibited over a fivefold reduction in survival in the treated cells at 48 h, whereas RPE cells genotyped for the hypomorphic TLR3 variant, L412F, were protected from this cytotoxicity. However, we were surprised that subsequent genetic association studies were unable to corroborate the initial data demonstrating a protective effect of L412F on GA (Cho et al. 2009b; Klein et al. 2010). Nonetheless, we have pursued TLR3 as a potentially critical signaling pathway in dry AMD progression given that functional biology often contradicts hypotheses generated with genetic association data as has occurred with sequencing investigations into VEGF-A polymorphisms and CNV (Richardson et al. 2007). Our functional in vivo and correlate in situ data suggest that TLR3 activation is an important factor in retinal cell health and may provide a critical pathway for the development of targeted therapeutics for GA.

1.4 Short Interfering RNA-Based Drugs Activate TLR3 Pathways

While potent TLR3 activation occurs with long dsRNA of 30 nucleotides (nt) or more, short interfering RNAs (siRNA), commonly designed as 19-nt RNA duplexes with 2-nt overhangs, may also serve as ligands for this highly evolved dsRNA recognition system at concentrations currently used in molecular biology protocols (Kariko et al. 2004). While this initial finding was concerning, we were fascinated that 21-nt siRNAs were being used nearly ubiquitously in molecular biology investigations and that several siRNA-based drugs were undergoing rapid development for clinical deployment with no evidence of unanticipated side effects. In fact, the pioneering clinical trials utilizing siRNA-based therapeutics were designed to test compounds targeting Vegfa and Vegfr1 for the treatment of neovascular AMD. While these initial trials were ongoing, we began studies evaluating siRNAs targeting critical angiogenic factors in the laser injury mouse model of CNV. We were surprised to find that nontargeted control siRNAs equally suppressed vascular growth when compared to siRNAs targeting Vegfa in this model. Furthermore, siRNA that was chemically modified to prevent incorporation into the RNAi silencing complex, RISC, also inhibited CNV strongly suggesting that this vascular effect was not due to RNAi but likely linked to an innate immune activation pathway.

In all of these studies, we employed unmodified “naked” siRNAs that cannot cross cell membranes due to their large molecular weight (~14 kDa) and polyanionic structure; therefore, we hypothesized that interaction with an extracellular receptor may be required for this angio-inhibitory effect. Our studies revealed that cell surface TLR3, which is expressed on human and mouse choroidal endothelial cells, is activated by 21-nt siRNA in a sequence- and target-independent fashion leading to downstream IFN-related gene expression and subsequent neovascular suppression (Kleinman et al. 2008)(Fig. 1.2). Similar angio-inhibition in the laser-injury CNV model was observed with the synthetic TLR3 agonist, poly I:C. Our initial data have been reproduced with control and targeted siRNAs synthesized by several different commercial sources and in two separate reports from independent laboratories (Ashikari et al. 2010; Gu et al. 2010). In further support of our findings, another laboratory recently observed parallel results of angiogenic suppression with control siRNAs in mouse hepatocellular carcinoma tumor models via IFN-γ upregulation and endothelial cell apoptosis (Berge et al. 2010).

Fig. 1.2.

RNA interference may occur through the traditional intracellular pathway mediated by RISC. However, siRNA (≥21 nt) bind to and activate TLR3 leading to an angio-inhibitory class effect that is mediated through the upregulation of IFN- γ, interleukin-12, and apoptosis

Importantly, TLR3 was expressed on the surface of endothelial cells from all human peripheral tissues tested including lung, aorta, and lymphatics (Cho et al. 2009a) suggesting that this innate response is likely global. These findings are a cause for alarm given that many other diseases are currently being approached with pharmacologic intentions of systemically delivering siRNA-based drugs. Future directions for the development of siRNA therapies should include rational chemical engineering of siRNA molecules that evade TLR3 detection. A Korean group has already reported that an asymmetric 16-nt siRNA design is able to achieve efficient gene-targeted suppression without TLR3 activation (Chang et al. 2009). Collectively, these studies signal a paradigm shift in understanding the role of the innate immune system in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, directly address unanticipated immune side effects of siRNA-based drugs, and open new avenues of research into TLR-mediated cellular effects in the retina and brain.

Acknowledgments

J.A. was supported by NEI/NIH, the Doris Duke Distinguished Clinical Scientist Award, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Clinical Scientist Award in Translational Research, the Dr. E. Vernon Smith and Eloise C. Smith Macular Degeneration Endowed Chair, the Senior Scientist Investigator Award (RPB), the American Health Assistance Foundation, and a departmental unrestricted grant from the RPB. M.E.K. by the International Retinal Research Foundation and NIH T32 grant.

References

- Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, et al. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashikari M, Tokoro M, Itaya M, et al. Suppression of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization by nontargeted siRNA. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:3820–3824. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balachandran S, Thomas E, Barber GN. A FADD-dependent innate immune mechanism in mammalian cells. Nature. 2004;432:401–405. doi: 10.1038/nature03124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge M, Bonnin P, Sulpice E, et al. Small Interfering RNAs Induce Target-Independent Inhibition of Tumor Growth and Vasculature Remodeling in a Mouse Model of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2010 doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JS, Alexopoulou L, Sloane JA, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 is a potent negative regulator of axonal growth in mammals. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13033–13041. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4290-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CI, Yoo JW, Hong SW, et al. Asymmetric shorter-duplex siRNA structures trigger efficient gene silencing with reduced nonspecific effects. Mol Ther. 2009;17:725–732. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho WG, Albuquerque RJ, Kleinman ME, et al. Small interfering RNA-induced TLR3 activation inhibits blood and lymphatic vessel growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009a;106:7137–7142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812317106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y, Wang JJ, Chew EY, et al. Toll-like receptor polymorphisms and age-related macular degeneration: replication in three case-control samples. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009b;50:5614–5618. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field R, Campion S, Warren C, et al. Systemic challenge with the TLR3 agonist poly I:C induces amplified IFNalpha/beta and IL-1beta responses in the diseased brain and exacerbates chronic neurodegeneration. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:996–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L, Chen H, Tuo J, et al. Inhibition of experimental choroidal neovascularization in mice by anti-VEGFA/VEGFR2 or non-specific siRNA. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoebe K, Janssen EM, Kim SO, et al. Upregulation of costimulatory molecules induced by lipopolysaccharide and double-stranded RNA occurs by Trif-dependent and Trif-independent pathways. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1223–1229. doi: 10.1038/ni1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CS, Arbour N, Manusow J, et al. TLR signaling tailors innate immune responses in human microglia and astrocytes. J Immunol. 2005;175:4320–4330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariko K, Bhuyan P, Capodici J, et al. Small interfering RNAs mediate sequence-independent gene suppression and induce immune activation by signaling through toll-like receptor 3. J Immunol. 2004;172:6545–6549. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein ML, Ferris FL, 3rd, Francis PJ, et al. Progression of geographic atrophy and genotype in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1554–1559. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.12.012. 1559 e1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman ME, Yamada K, Takeda A, et al. Sequence- and target-independent angiogenesis suppression by siRNA via TLR3. Nature. 2008;452:591–597. doi: 10.1038/nature06765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar MV, Nagineni CN, Chin MS, et al. Innate immunity in the retina: Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;153:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathia JD, Okun E, Tang SC, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 is a negative regulator of embryonic neural progenitor cell proliferation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13978–13984. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2140-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis TP, Lietman T, Strauss E. Infectious agents and ARMD: a connection. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:468–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R, Janeway C., Jr The Toll receptor family and microbial recognition. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:452–456. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01845-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan E, Burns K, Hofmann K, et al. RIP1 is an essential mediator of Toll-like receptor 3-induced NF-kappa B activation. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:503–507. doi: 10.1038/ni1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda K, Kitano H. A comprehensive map of the toll-like receptor signaling network. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2 doi: 10.1038/msb4100057. 2006 0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson AJ, Islam FM, Guymer RH, et al. A tag-single nucleotide polymorphisms approach to the vascular endothelial growth factor-A gene in age-related macular degeneration. Mol Vis. 2007;13:2148–2152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringheim GE, Conant K. Neurodegenerative disease and the neuroimmune axis (Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, and viral infections) Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2004;147:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledz CA, Holko M, de Veer MJ, et al. Activation of the interferon system by short-interfering RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:834–839. doi: 10.1038/ncb1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, et al. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 2003;301:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1087262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Stratton C, Francis PJ, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 and geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1456–1463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]