Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to quantify the effects of coronary atherosclerosis morphology and extent on myocardial flow reserve (MFR).

Background

Although the relationship between coronary stenosis and myocardial perfusion is well established, little is known about the contribution of other anatomic descriptors of atherosclerosis burden to this relationship.

Methods

We evaluated the relationship between atherosclerosis plaque burden, morphology, and composition and regional MFR (MFRregional) in 73 consecutive patients undergoing Rubidium-82 positron emission tomography and coronary computed tomography angiography for the evaluation of known or suspected coronary artery disease.

Results

Atherosclerosis was seen in 51 of 73 patients and in 107 of 209 assessable coronary arteries. On a per-vessel basis, the percentage diameter stenosis (p = 0.02) or summed stenosis score (p = 0.002), integrating stenoses in series, was the best predictor of MFRregional. Importantly, MFRregional varied widely within each coronary stenosis category, even in vessels with nonobstructive plaques (n = 169), 38% of which had abnormal MFRregional (<2.0). Total plaque length, composition, and remodeling index were not associated with lower MFR. On a per-patient basis, the modified Duke CAD (coronary artery disease) index (p = 0.04) and the number of segments with mixed plaque (p = 0.01) were the best predictors of low MFRglobal.

Conclusions

Computed tomography angiography descriptors of atherosclerosis had only a modest effect on downstream MFR. On a per-patient basis, the extent and severity of atherosclerosis as assessed by the modified Duke CAD index and the number of coronary segments with mixed plaque were associated with decreased MFR.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, coronary computed tomography angiography, myocardial flow reserve, positron emission tomography

In patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), management decisions are generally based on the severity of symptoms and the magnitude of inducible myocardial ischemia. Although the anatomic severity of epicardial coronary stenosis has been used as a surrogate of functional significance, there is increased recognition that there is great individual variability and that complementary hemodynamic evaluation can improve the identification of patients who will benefit from revascularization (1). Coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) offers accurate, rapid, and noninvasive delineations of the extent and severity of anatomic CAD. Single- and multicenter studies have demonstrated that coronary CTA has high sensitivity and negative predictive value for excluding significant CAD (2). Recent studies have shown that predictions of flow-limiting disease based on the severity of stenosis identified by CTA have the same limitations as those identified for conventional coronary angiography (3,4). Unlike conventional coronary angiography, CTA allows detailed delineation of other aspects of atherosclerosis beyond the severity of luminal narrowing, including plaque morphology and vessel remodeling. However, there are limited data about the relationship between these integrated anatomic descriptors of disease severity and coronary hemodynamics. Our objective was to evaluate the relationship between plaque extent, severity, and morphology by CTA and with functional downstream effect on myocardial perfusion as defined by estimates of myocardial blood flow (MBF) (in ml/min/g) and flow reserve derived by positron emission tomography (PET).

Methods

Study population

Seventy-three consecutive patients with suspected or known stable CAD referred for coronary CTA and rubidium-82 myocardial perfusion PET imaging within a 14-day interval were included in this analysis. Patients with previous coronary artery bypass grafting were excluded, as were those with valvular heart disease or a left ventricular ejection fraction <40%. For each subject, information about their medical history, coronary risk factors, and medication use was collected at the time of their imaging study.

The study was approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board, and all study procedures were in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Hybrid PET and CTA study

PET SCAN

Patients were studied using a whole-body PET computed tomography (CT) scanner (Discovery RX or STE LightSpeed 64, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) after an overnight fast. Patients were instructed to avoid caffeine and methylxanthine-containing substances for 24 h.

MBF was measured at rest and during peak hyperemia using rubidium-82 as a perfusion tracer, as described previously (5). Briefly, after transmission imaging and beginning with the intravenous bolus administration of rubidium-82 (1,480 to 2,220 MBq), list mode images were acquired for 7 min. Then, intravenous dipyridamole (0.142 mg/kg/min for 4 min; n = 14), adenosine (0.142 mg/kg/min for 4 min; n = 53), or (0.4-mg bolus; n = 6) was infused. At peak hyperemia, a second dose of rubidium-82 was injected, and images were recorded in the same manner. The heart rate, systemic blood pressure, and 12-lead electrocardiogram were recorded at baseline and every minute during and after the infusion of the vasodilator. The rate pressure product was calculated by multiplying heart rate and systolic blood pressure measured at rest and during peak hyperemia, respectively.

CTA SCAN

Coronary CTA was performed using a 64-channel CT scanner (GE Discovery VCT, GE Healthcare; n = 68) or 320-channel CT scanner (Aquilion One, Toshiba America Medical Systems, Tustin, California; n = 5). Patients with a heart rate >60 beats/min received 5 to 15 mg metoprolol intravenously immediately before the CT scan. All patients with a systolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg before administration of contrast received 0.4 mg of sublingual nitroglycerin. The mean heart rate during CTA was 62 ± 8 beats/min.

A low-dose scout scan was performed to define anatomic landmarks for the contrast-enhanced study. Before each scan, a test bolus of 10 to 20 ml of Ultravist 370 (370 mg/ml of iodine) was injected at 5 ml/s. The timing of peak contrast enhancement in the ascending aorta was then used to determine the timing of scan acquisition. The contrast-enhanced scan used 60 to 90 ml of Ultravist 370 intravenously (rate, 5 ml/s) during a single breath-hold (~10 s).

CTA data were acquired using the following parameters for studies performed with GE Discovery VCT: collimation, 0.625 mm; gantry rotation, 300 ms; helical acquisition using a pitch of 0.16, tube current, 300 to 600 mA with ECG tube current modulation; tube voltage, 120 kV; rotation time, 0.35 s, and for studies performed with Aquilion One: collimation, 0.50 mm; gantry rotation, 350 ms; axial volume acquisition using prospective electrocardiographic triggering, x-ray tube current, 300 to 550 mA; x-ray tube voltage, 120 kV. Retrospective electrocardiography gating was used to reconstruct images at mid-diastole (65% to 75%, in 5% increments) for patients with low heart rates (<65 beats/min), and in end-systole (45% to 60%, in 5% increments) for patients with higher heart rates (≥65 beats/min). The cardiac phase with the best image quality was used for analysis.

Data analysis

QUANTIFICATION OF MBF

List mode images were unlisted and then reconstructed into 27 frames as described previously (5). To compute a semiquantitative summed stress score and a summed difference score, a standard 17-segment, 5-point scoring system was used. Commercially available software was used to calculate rest and stress left ventricular ejection fraction (Corridor 4DM, Ann Arbor, Michigan). To measure absolute MBF value, right and left ventricular blood pool time-activity curves were obtained using factor analysis (5). Regional and global rest and peak MBFs were then calculated by fitting the rubidium-82 time–activity curves with a 2-compartment tracer kinetic model and modeled extraction fraction as described previously (5,6). Regional (MFRregional) and global MFR (MFRglobal) were computed as the ratio of peak MBF to rest MBF. Regional coronary vascular resistance was computed as the ratio of mean arterial blood pressure to MBF. This methodology was validated against 13N-ammonia as the reference standard at our institution. In addition, the reproducibility of the MBF estimates in repeated rubidium-82 studies was very good, both at rest and during peak stress (R2 = 0.935), and no absolute systematic error was observed (5,6).

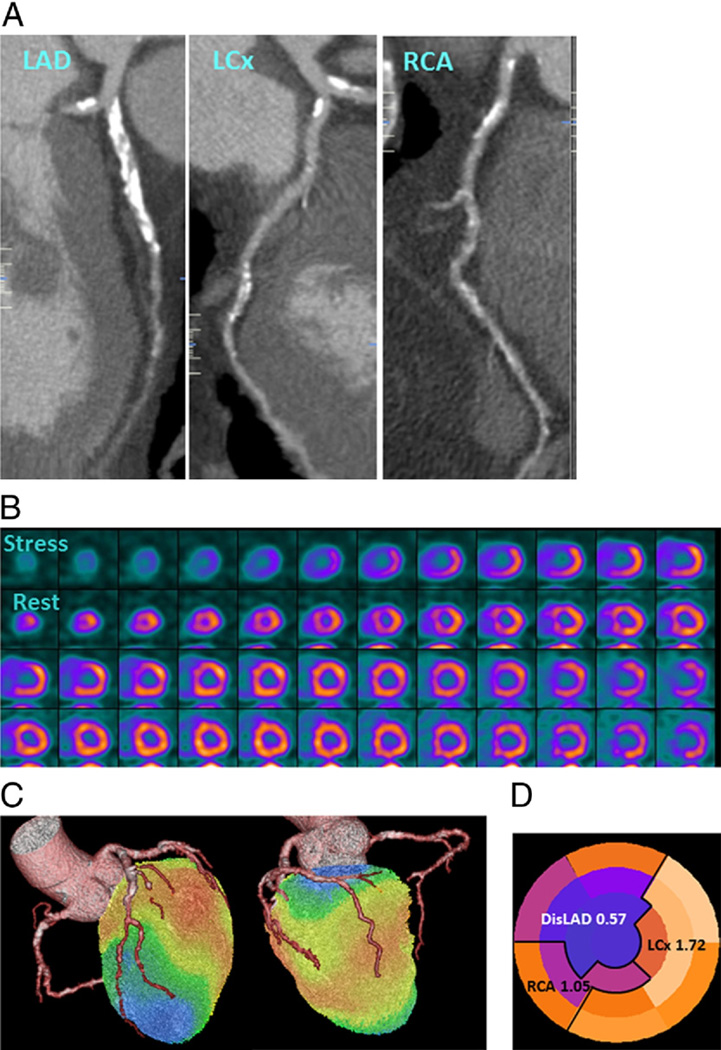

REGISTRATION OF MYOCARDIAL PERFUSION AND ANGIOGRAPHIC INFORMATION

Standard PET/CTA fusion software (HeartFusion, GE Healthcare) was used to facilitate ascertainment of the exact correspondence between the territorial region of interest used to estimate the MFRregional and the location of coronary stenoses (Fig. 1). Each of the 17 PET myocardial segments was assigned to the corresponding coronary vessel by 2 expert readers. MFRregional was computed based on these assignments by averaging MBF reserve values involving all segments distal to the most severe angiographic stenosis, regardless of whether a perfusion defect was present. For vessels without any stenosis, all segments subtended by the vessel were averaged.

Figure 1. Rubidium-82 PET/CTA Fusion Imaging and Correlation Between Regional MFR and Coronary Stenoses.

Integrated positron emission tomography/computed tomography angiography (PET/CTA) study in a 66-year-old man with obesity, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus. (A) Curved multiplanar reconstructions. The proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) shows a long calcified plaque with 85% stenosis. The left circumflex artery (LCx) artery shows calcified plaques with 47% stenosis proximally and 77% stenosis distally. The right coronary arter (RCA) has a proximal calcified plaque with 92% stenosis. The summed stenosis score was 19 in the LAD, 6 in the LCx, and 16 in the RCA. The Duke CAD index was 74. (B) Stress and rest myocardial perfusion imaging shows extensive and severe ischemia in LAD territory with transit ischemic dilation. (C) PET/CTA fusion imaging demonstrating that the mid- and basal inferior segments were supplied by a large-dominant LCx in contrast to the standard American Heart Association model. (D) Regional myocardial flow reserve (MFR) was 0.57, 1.72, and 1.05 in the LAD, LCx, and RCA territories, respectively. The MFRglobal was 1.28. DisLAD = distal left anterior descending artery.

QUANTIFICATION OF ATHEROSCLEROTIC BURDEN

Reconstructed CTA images were analyzed on a dedicated 3-dimensional workstation (Vitrea, Vital Images, Inc., Minnetonka, Minnesota). Coronary segments with a diameter of >1.5 mm were using a 17-segment model. Ten vessels were excluded due to motion artifact or previous stent implantation and/or myocardial infarction, leaving a total of 209 coronary vessels for the per-vessel analysis. For the evaluation of plaque morphology and severity, thin multiplanar reformation was used to view both cross-sectional and longitudinal images.

Definitions of descriptors of atherosclerotic burden

Plaque length was measured as the distance (in millimeters) from the proximal to the distal shoulder of each plaque. Total plaque length was calculated for each coronary vessel and for each patient globally by summing the lengths of individual plaques along each coronary vessel and in each patient. Epicardial luminal narrowing was assessed by quantifying the percentage diameter stenosis. The percentage of diameter stenosis was calculated by dividing the minimal lumen diameter of each stenosis by the proximal normal artery diameter. To account for serial plaques within each vessel, each coronary segment was graded using a 5-point scoring system (0 = no plaque, 1 = 1% to 24% stenosis, 2 = 25% to 49%, 3 = 50% to 69%, 4 = 70% to 100%). From these segmental scores, a summed stenosis score was then derived by adding individual segmental scores for each vessel and each patient.

Plaque composition was assessed by measuring the Hounsfield units within each plaque. Plaques with a CT density >150 Hounsfield units were considered calcified. Noncalcified plaque showed only a noncalcified component. Mixed plaque had both calcified and noncalcified components.

The remodeling index was calculated as the ratio of the overall vessel diameter at the site of maximal stenosis to that of a neighboring proximal nonstenotic segment, and vessels were subgrouped as follows: an index <1.10 identified vessels with negative remodeling and no remodeling; an index 1.10 to 1.29 defined mild to moderate positive remodeling, whereas an index ≥1.30 defined extensive positive remodeling. The most severely stenotic plaque in each coronary vessel was identified as the index lesion for the per-vessel analysis.

Finally, a modified Duke CAD index integrating the number of affected vessels and the location of disease with ≥50% stenosis was used to quantify the extent and severity of CAD on a per-patient level (7).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD or median and quartile, and categorical variables were as simple proportions. To correct for right-ward skew, MFR and MBF data were logarithmically transformed before further analysis. For per-patient analyses, univariate regression was used to explore the association among MFRglobal and demographic variables, coronary risk factors, and CTA descriptors. A multivariate regression model was used to identify independent predictors of MFRglobal among significant univariate variables. To examine the correlation between quantitative MFRglobal and semiquantitative summed stress score and summed difference score, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used.

For the per-vessel analysis, diameter stenosis was categorized as no disease, 1% to 49%, 50% to 69%, and ≥70% stenosis. Differences in rest MBFregional, peak MBFregional, and MFRregional across these categories were evaluated for significance with analysis of variance of the log-transformed values. To account for confounding due to the inclusion of multiple vessels per patient (i.e., clustering), a mixed-effects model was used for regression analysis with per-patient random effect to account for intrapatient correlation. Mixed-effects models were used to evaluate the relationship between MFRregional and the percentage of diameter stenosis or summed stenosis score and to explore the role of additional CTA descriptors as well as traditional coronary risk factors.

Receiver-operator characteristic curves were constructed for the identification of patients with the modified Duke CAD index ≥50 (i.e., those with 2-vessel disease with proximal left anterior descending artery involvement or 3-vessel disease) using MFRglobal. A 2-tailed p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the patients studied are summarized in Table 1. The population was sex balanced. Thirty-one of 73 patients had a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2. Dyslipidemia and hypertension were each present in >60% of the patients, whereas diabetes was present in nearly 20%. The use of medications for control of blood pressure and cholesterol was widespread. The frequency of coronary risk factors was very high, with 89% of subjects having 1 or more coronary risk factors, 56% having 2 or more, and nearly one-third having 3 or more.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (n = 73)

| Demographics | |

| Age, yrs | 60.6 ± 12.0 |

| Male | 33 (45) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.8 ± 8.1 |

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 31 (42) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 6 (8) |

| CAD risk factors | |

| Hypertension | 45 (62) |

| Diabetes | 14 (19) |

| Dyslipidemia | 44 (60) |

| Tobacco use | 4 (5) |

| Family history | 27 (37) |

| CAD risk factors | |

| None | 8 (11) |

| ≥1 | 65 (89) |

| ≥2 | 42 (56) |

| ≥3 | 22 (30) |

| Medications | |

| Antihypertensive medications | 45 (62) |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 21 (29) |

| Beta-blocker | 35 (48) |

| Calcium-channel blocker | 15 (21) |

| Statin | 42 (58) |

| Aspirin | 38 (52) |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI = body mass index; CAD = coronary artery disease.

Atherosclerosis burden and regional myocardial perfusion: per-vessel analysis

Of the 209 vessels analyzed, 107 (51%) had evidence of atherosclerotic plaque. Among these, 18 vessels had 50% to 69% stenosis and 22 had ≥70% stenosis. Three-fourths of the vessels had predominantly calcified lesions. The average plaque length was approximately 15 mm, although the range was quite broad (interquartile range: 0 to 19.6 mm) (Table 2).

Table 2.

CTA Findings

| Patient characteristics (n = 73) | |

| Vessels involved | |

| No atherosclerosis | 22 (30) |

| Nonobstructive disease | 27 (37) |

| 1-vessel disease | 9 (12) |

| 2-vessel disease | 8 (11) |

| 3-vessel disease | 7 (10) |

| Modified Duke CAD index | 15.7 ± 25.3 |

| Summed stenosis score | 6.4 ± 8.5 |

| Total plaque length, mm | 40.0 ± 57.2 |

| No. (%) of segments | |

| With any plaque | 2.9 ± 3.1 |

| With calcified plaque | 2.4 ± 2.7 |

| With noncalcified plaque | 0.2 ± 0.5 |

| With mixed plaque | 0.4 ± 0.9 |

| With positive remodeling | 1.5 ± 1.8 |

| 1 (0–3)* | |

| Vessel characteristics (n = 209) | |

| Stenosis severity | |

| No plaque | 102 (49) |

| 1%–24% | 24 (11) |

| 25%–49% | 43 (21) |

| 50%–69% | 18 (9) |

| ≥70% | 22 (10) |

| Summed stenosis score | 2.4 ± 3.4 |

| No. of segments with plaque | 1.1 ± 1.3 |

| Total plaque length, mm | 14.4 ± 24.8 |

| Plaque composition | |

| Predominantly calcified | 80 (75) |

| Noncalcified | 10 (9) |

| Mixed | 17 (16) |

| Positive vascular remodeling index | |

| <1.10 | 48 (45) |

| 1.10–1.29 | 51 (48) |

| ≥1.30 | 8 (7) |

Values are n (%) or mean ± SD.

Median (interquartile range).

CAD = coronary artery disease; CTA = computed tomographic angiography.

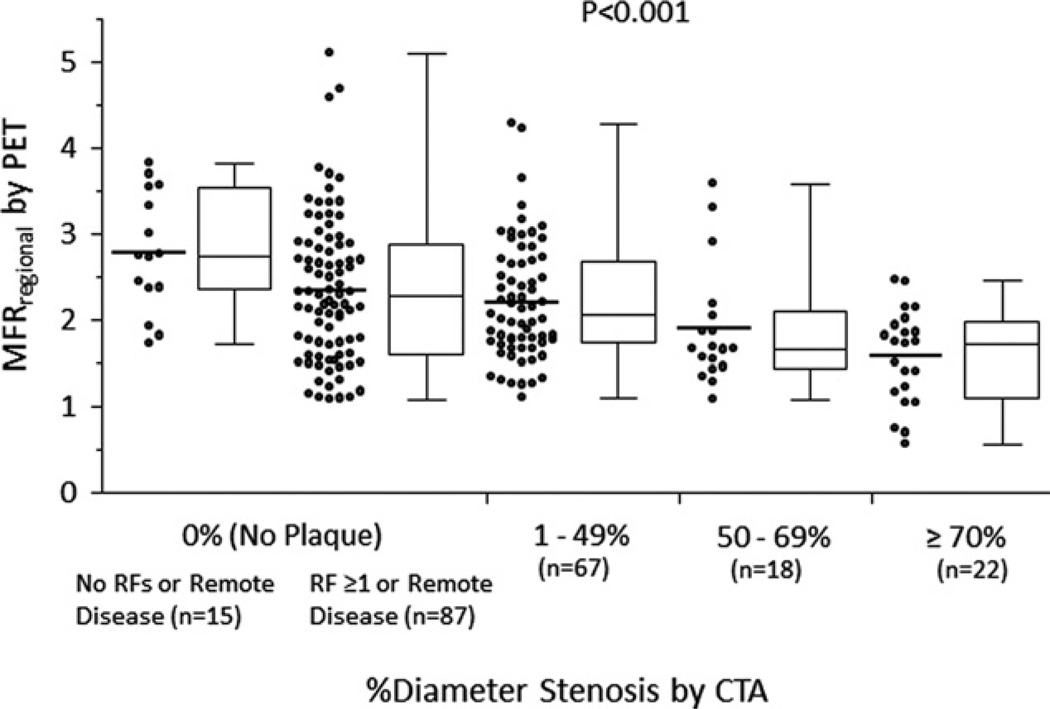

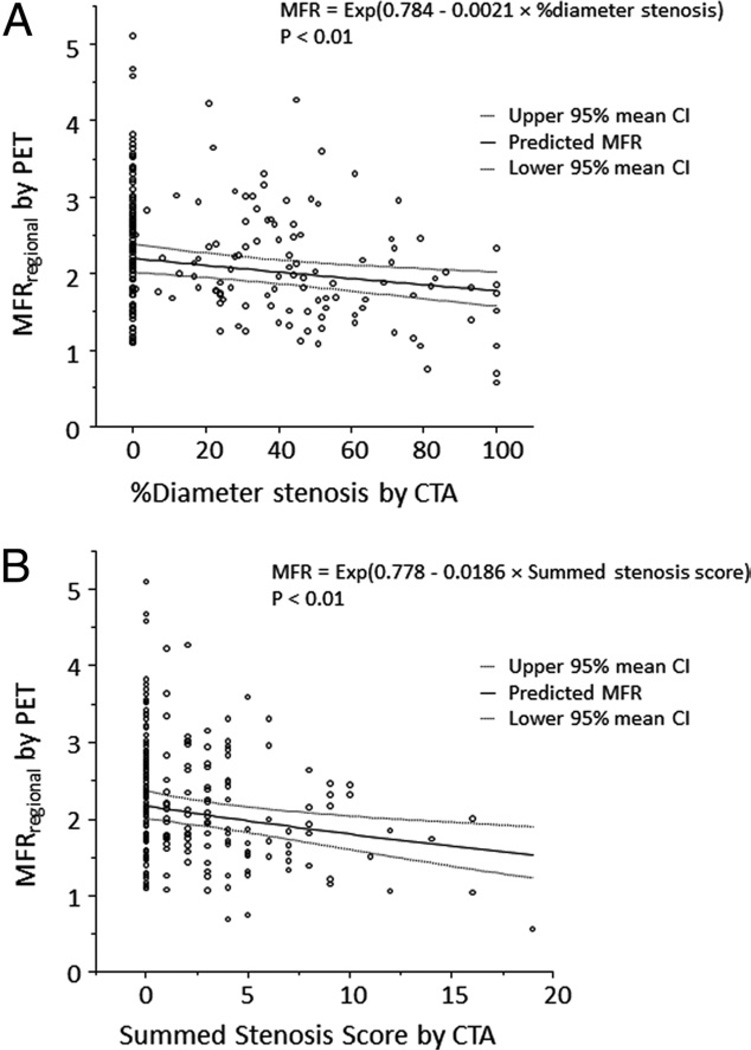

Rest MBFregional was comparable across the entire spectrum of stenosis severity (Table 3). In contrast, there was a stepwise decrease in both peak MBFregional and MFRregional with increasing stenosis severity (Table 3, Figs. 2 and 3). Among normal coronary vessels by CTA, MFRregional was higher in patients without coronary risk factors or remote disease than that in patients with coronary risk factors or remote disease (p = 0.038). In subgroup analysis of angiographically normal coronary vessels, no significant associations were found between MFRregional and patient demographics, coronary risk factors, or the presence of remote disease. Of note, MFRregional varied widely within each coronary stenosis category, even in vessels with nonobstructive CAD (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Regional Myocardiaal Perfusion and Percentage of Diameter Stenosis

| % Diameter Stenosis by CTA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% (No Plaque) | 1%–49% | 50%–69% | ≥70% | p Value | |

| Quantitative myocardial perfusion | |||||

| Rest MBF, ml/g/min | 1.01 (0.81–1.21) | 0.93 (0.75–1.21) | 1.27 (0.98–1.47) | 1.03 (0.87–1.34) | 0.10 |

| Peak MBF, ml/g/min | 2.19 (1.54–3.76) | 1.83 (1.40–3.14) | 2.07 (1.54–3.53) | 1.69 (1.23–1.98) | 0.03* |

| MFR | 2.33 (1.73–2.91) | 2.12 (1.75–2.68) | 1.66 (1.45–2.07) | 1.78 (1.13–2.19) | <0.001* |

Values are median (interquartile range).

Significant variables by the analysis of variance of the log-transformed values.

MBF = myocardial blood flow; MFR = myocardial flow reserve; other abbreviations as in Table 2.

Figure 2. Per-Vessel Relationship Between MFR and Percentage of Diameter Stenosis Categories.

Scatterplots and box and whiskers plots demonstrating the distributions of regional myocardial reserve (MFRregional) in vessels with no plaque (patients with no risk factors [RF] or remote disease; patients with ≥1 RF or remote disease), 1% to 49%, 50% to 69%, and ≥70% diameter stenosis, respectively. Although there is a significant relationship between stenosis severity and MFRregional, there is wide variability. CTA = computed tomography angiography; PET = positron emission tomography.

Figure 3. Per-Vessel Relationship Between MFR and Percentage of Diameter Stenosis or Summed Stenosis Score.

Scatterplots demonstrating the inverse relationship between the percentage of diameter stenosis and MFRregional (A), and summed stenosis score and MFRregional (B). Solid lines indicate the best fit lines from a multivariate mixed model with 95% confidence intervals for the mean indicated by the dashed lines. CI = confidence interval; other abbreviations as in Figure 2.

Table 4 describes the results of multivariable analyses exploring the associations between estimates of coronary hemodynamics (MFRregional, peak MBFregional, and coronary vascular resistanceregional) and patient demographics, coronary risk factors, and anatomic data using 2 models that included the percentage of diameter stenosis (model 1) or summed stenosis score (model 2). Overall, both models were highly significant using any of the 3 descriptors of coronary artery physiology. Interestingly, the presence of obstructive disease in any vessel (≥50%) was associated with decreased MFRregional in remote vessels without apparent obstructive disease. However, other CTA-derived descriptors of epicardial coronary atherosclerosis (i.e., total plaque length, plaque composition, and remodeling index) were not significantly associated with reduced MFRregional.

Table 4.

Multivariate Models Describing Associations Between CTA Descriptions of Atherosclerosis Burden and MBF, MFR, and CVR

| MFR | Peak MBF | Peak CVR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Standardized Coefficient | p Value | Standardized Coefficient | p Value | Standardized Coefficient | p Value |

| Model 1: Demographics, CAD Risk Factors, Percentage of Stenosis, and Other CTA Descriptors of Atherosclerosis | ||||||

| −2 Log-likelihood | 98.5 | <0.001 | 89.3 | <0.001 | 78.8 | <0.001 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, yrs | −0.154 | 0.20 | −0.279 | 0.02* | 0.370 | 0.001* |

| Male | −0.084 | 0.48 | −0.142 | 0.22 | 0.232 | 0.04* |

| BMI, kg/m2 | −0.078 | 0.53 | −0.171 | 0.18 | 0.148 | 0.22 |

| Previous MI | −0.075 | 0.72 | −0.419 | 0.04* | 0.375 | 0.05 |

| CAD risk factors | ||||||

| Hypertension | 0.075 | 0.53 | −0.051 | 0.67 | 0.141 | 0.22 |

| Diabetes | −0.114 | 0.47 | −0.146 | 0.35 | 0.091 | 0.54 |

| Dyslipidemia | −0.002 | 0.98 | −0.056 | 0.63 | 0.037 | 0.74 |

| Tobacco use | −0.134 | 0.59 | −0.360 | 0.15 | 0.604 | 0.02* |

| Family history | −0.006 | 0.96 | −0.029 | 0.81 | −0.017 | 0.88 |

| CTA findings | ||||||

| % diameter stenosis | −0.233 | 0.02* | −0.133 | 0.04* | 0.118 | 0.06 |

| Vessel (LAD, LCx, RCA) | N/A | 0.39 | N/A | 0.006* | N/A | 0.003* |

| Total plaque length, mm | 0.043 | 0.48 | 0.018 | 0.63 | −0.024 | 0.51 |

| Plaque composition | 0.37 | 0.82 | 0.86 | |||

| Calcified | −0.065 | 0.68 | 0.061 | 0.55 | −0.065 | 0.52 |

| Noncalcified | 0.109 | 0.59 | 0.122 | 0.34 | −0.100 | 0.43 |

| Mixed | −0.275 | 0.17 | 0.055 | 0.67 | −0.042 | 0.74 |

| Remodeling index | 0.80 | 0.94 | 0.87 | |||

| <1.10 | 0.530 | 0.37 | −0.141 | 0.71 | 0.081 | 0.83 |

| 1.10–1.29 | −0.064 | 0.59 | −0.035 | 0.64 | 0.057 | 0.44 |

| ≥1.30 | 0.011 | 0.95 | 0.021 | 0.86 | −0.021 | 0.86 |

| Remote lesion ≥50% | −0.181 | 0.04* | −0.022 | 0.73 | −0.0004 | 0.99 |

| Model 2: Demographics, CAD Risk Factors, Summed Stenosis Score, and Other CTA Descriptors of Atherosclerosis | ||||||

| −2 Log-likelihood | 90.0 | <0.001 | 76.4 | <0.001 | 66.0 | <0.001 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, yrs | −0.152 | 0.20 | −0.269 | 0.02* | 0.358 | 0.002* |

| Male | −0.064 | 0.58 | −0.117 | 0.31 | 0.206 | 0.06 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | −0.078 | 0.53 | −0.177 | 0.16 | 0.155 | 0.19 |

| Previous MI | −0.104 | 0.61 | −0.440 | 0.03* | 0.394 | 0.04* |

| CAD risk factors | ||||||

| Hypertension | 0.060 | 0.61 | −0.055 | 0.64 | 0.143 | 0.21 |

| Diabetes | −0.100 | 0.53 | −0.127 | 0.42 | 0.072 | 0.63 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.002 | 0.99 | −0.047 | 0.68 | 0.029 | 0.80 |

| Tobacco use | −0.120 | 0.63 | −0.361 | 0.15 | 0.599 | 0.03* |

| Family history | −0.001 | 0.99 | −0.026 | 0.83 | −0.020 | 0.86 |

| CTA findings | ||||||

| Summed stenosis score | −0.298 | 0.002* | −0.223 | 0.0003* | 0.210 | 0.0005* |

| Vessel (LAD, LCx, RCA) | N/A | 0.23 | N/A | 0.01* | N/A | 0.006* |

| Total plaque length, mm | 0.132 | 0.06 | 0.092 | 0.04* | −0.094 | 0.03* |

| Plaque composition | 0.08 | 0.70 | 0.71 | |||

| Calcified | −0.064 | 0.68 | 0.060 | 0.55 | −0.063 | 0.51 |

| Noncalcified | 0.075 | 0.70 | 0.107 | 0.39 | −0.088 | 0.47 |

| Mixed | −0.408 | 0.03* | −0.024 | 0.84 | 0.028 | 0.81 |

| Remodeling index | 0.79 | 0.91 | 0.85 | |||

| <1.10 | 0.592 | 0.31 | −0.093 | 0.80 | 0.034 | 0.92 |

| 1.10–1.29 | −0.056 | 0.62 | −0.031 | 0.67 | 0.051 | 0.45 |

| ≥1.30 | 0.064 | 0.74 | 0.070 | 0.56 | −0.068 | 0.56 |

| Remote lesion ≥50% | −0.174 | 0.04* | −0.038 | 0.53 | 0.018 | 0.77 |

Quantitative relationship between the extent of CAD and myocardial perfusion: per-patient analysis

CTA-derived descriptors of coronary atherosclerosis on a patient level are summarized in Table 2. More than two-thirds of patients had either normal coronary arteries or only nonobstructive disease. Multivessel obstructive CAD (2- and 3-vessel disease) was present in 21% of patients.

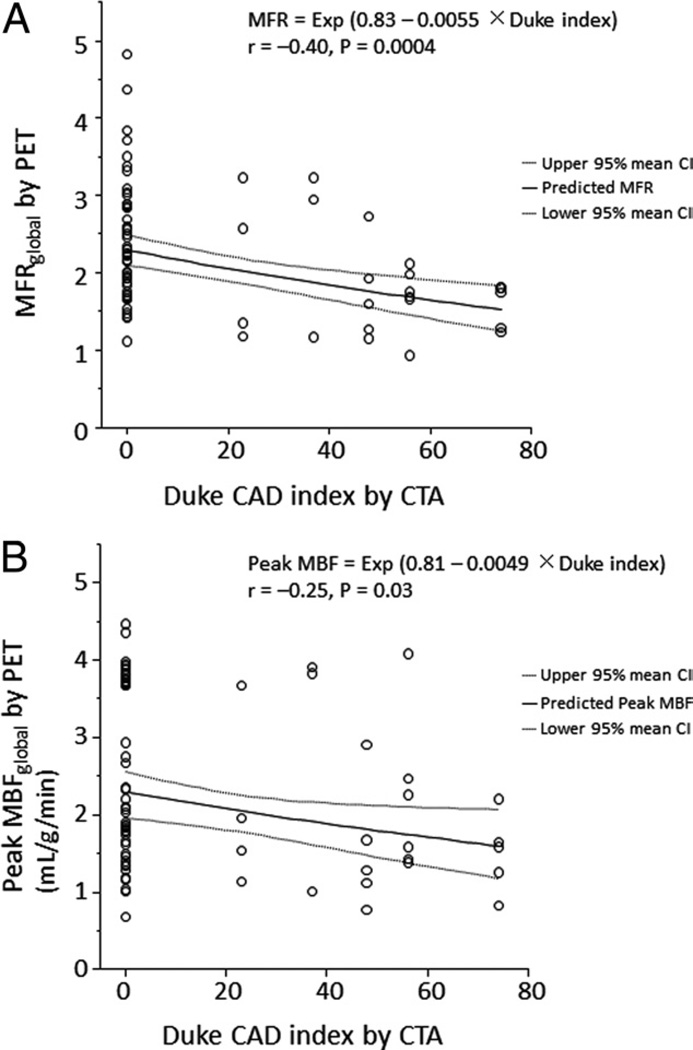

By semiquantitative visual analysis of PET images, 42 patients had normal scans (summed stress score = 0), 11 had a summed stress score of 1 to 3, and 20 patients had a summed stress score ≥4. Quantitative MFRglobal was inversely correlated with the semiquantitative summed stress score (r = −0.34, p = 0.01) and summed difference score (r = −0.31, p = 0.01). As in the per-vessel analysis, MFRglobal and peak MBFglobal showed a modest inverse correlation with the severity of CAD, as defined by the modified Duke CAD index (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Per-Patient Relationship Between MFR and Duke CAD Index.

Scatterplot showing the inverse relationship between modified Duke CAD (coronary artery disease) index and MFRglobal (A) or peak MBFglobal (B). The solid line corresponds to the best fit line with ln(MFRglobal) (A) and ln(peak MBFglobal) (B) as the response variable and modified Duke CAD index as the predictor variable. Dashed lines indicate the 95% mean confidence interval. MBF = myocardial blood flow; other abbreviations as in Figure 2.

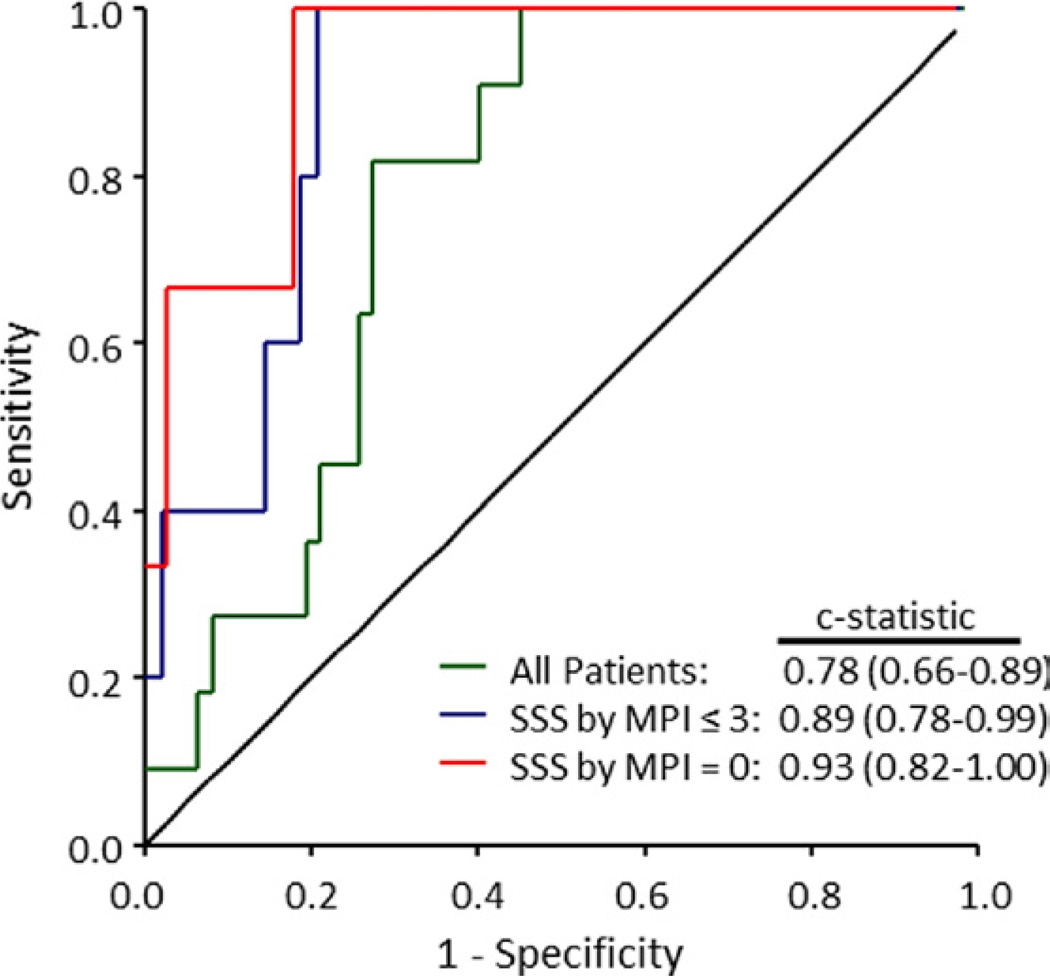

Interestingly, 17 of 42 patients (40%) with normal PET perfusion imaging on qualitative analysis had quantitative MFRglobal <2.0. Five of these 17 patients (29%) had significant obstructive CAD (≥50% stenosis) by CTA. In contrast, only 2 of 25 patients (8%) with a normal scan and preserved MFR (MFRglobal ≥2.0) showed obstructive CAD by CTA. Quantitative MFRglobal improved the identification of patients with high-risk coronary anatomy by CTA (Duke CAD index ≥50) including those with 2-vessel CAD with proximal left anterior descending artery stenosis ≥50% and 3-vessel CAD (Fig. 5). This was true even among patients with normal findings on PET (summed stress score = zero) or relatively low-risk findings on PET scans (summed stress score ≤3) by semiquantitative visual analysis. An MFRglobal <2.0 had a sensitivity of 0.91 (95% confidence interval: 0.59 to 1.00) and specificity of 0.58 (95% confidence interval: 0.45 to 0.70) to identify high-risk CAD by CTA. Similar values were obtained for the normal and relatively low-risk subgroups (receiver-operator characteristic area = 0.93 and 0.89, respectively) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Receiver-Operator Characteristic Curves for Identification of High-Risk Coronary Anatomy.

Receiver-operator characteristic curves for the identification of Duke CAD index ≥50 (including 2-vessel CAD with proximal LAD stenosis ≥50% and 3-vessel CAD) using MFRglobal among all patients studied as well as subsets with normal (summed stress score [SSS] = 0) or relatively low-risk (SSS ≤3) PET myocardial perfusion images (MPI). Abbreviations as in Figures 1, 2, and 4.

In multivariable analyses including demographic data, coronary risk factors, and CTA data, only the modified Duke CAD index (standardized coefficient = −0.380, p = 0.04) and the number of coronary segments with mixed plaque (standardized coefficient = −0.585, p = 0.01) were significantly associated with reduced MFRglobal (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariable Predictors of MFRglobal Model: Significant Univariate Predictors Among Demographics, CAD RFs, and CTA Findings

| Variable | Standardized Coefficient | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age, yrs | −0.147 | 0.22 |

| CTA findings | ||

| Modified Duke CAD index | −0.380 | 0.04* |

| Summed stenosis score | −0.088 | 0.85 |

| Total plaque length, mm | 0.189 | 0.52 |

| No. of segments | ||

| With any plaque | 1.270 | 0.07 |

| With mixed plaque | −0.585 | 0.01* |

| With calcified plaque | −1.141 | 0.07 |

Discussion

There are several important findings in this study. First, on a per-vessel basis, we found a statistically significant but clinically modest relationship between the degree of stenosis severity by CTA and its downstream effect of coronary artery physiology as assessed by MFR, peak MBF, or coronary vascular resistance. Second, there appears to be widespread physiologic variability in peak MBF and MFR even in coronary territories supplied by angiographically normal vessels or those with nonobstructive disease. Third, global quantitative estimates of MFR were sensitive markers for the identification of patients with high-risk anatomic disease by CTA.

There is growing and consistent evidence supporting the high sensitivity and negative predictive value of CTA for ruling out the presence of obstructive CAD (2,3). However, the presence of coronary plaques on CTA is more problematic to interpret clinically because the technique offers only moderate accuracy to delineate the stenosis severity compared with quantitative coronary angiography. An additional problem is that estimates of anatomic severity of CAD by CTA or conventional angiography are only modest predictors of downstream ischemia (8). Unlike conventional angiography, CTA allows a more detailed assessment of plaque burden including plaque morphology and composition as well as vessel remodeling. It has been hypothesized that integration of these comprehensive anatomic descriptors of disease severity may improve the ability of CTA to diagnose flow-limiting disease and, thus, help identify patients for revascularization. Accordingly, we sought to determine the relationships between the anatomic severity of disease as demonstrated by CTA and its physiologic severity as defined by quantitative estimates of MBF and MFR as defined by PET. The use of quantitative myocardial perfusion as a more sensitive means to define functional significance builds on previous work using less sensitive semiquantitative assessments of ischemia (9).

On a per-vessel basis, we found a statistically significant but clinically modest relationship between the degree of stenosis severity by CTA and MFR. Indeed, we observed wide physiologic variability within each category of stenosis severity, which is consistent with the results of other investigators (10). Importantly, this variability between epicardial CAD and its downstream physiologic consequence is not unique to CTA and has been previously noted with conventional quantitative coronary angiography (8,11). These results extend those of previous studies by demonstrating that the observations derived from conventional coronary angiography also apply to CTA and highlights the notion that the percentage of diameter stenosis is only a modest descriptor of coronary resistance, confirming the universality of these relationships using different methodologies for assessing the anatomic severity of CAD. Importantly, we found that other CTA-based descriptors of coronary atherosclerosis unique to CTA did not add incremental information beyond the quantitative percentage of diameter stenosis for predicting decreased MFR as a downstream measure of impaired tissue perfusion. If these CTA descriptors were shown to provide incremental prognostic data over myocardial perfusion, they could be used to identify individuals who would benefit from more aggressive medical therapies. This needs to be examined in a larger study. However, on a per-patient basis, the extent of atherosclerosis as assessed by the modified Duke CAD index (integrating the site and severity of coronary stenosis) and the number of coronary segments with mixed plaque were associated with decreased MFR. This finding agrees with that reported by Lin et al. (12) and may reflect a link between noncalcified plaques as a surrogate marker of more diffuse coronary microvascular dysfunction.

A second observation of our study was that there appears to be widespread physiologic variability in peak MBF and MFR, even in coronary territories supplied by angiographically normal vessels or those with nonobstructive disease. Interestingly, we observed that the presence of obstructive disease (≥50%) in 1 vessel was associated with a decreased MFR in remote myocardial regions supplied by vessels without obstructive CAD. This is consistent with a small previous study demonstrating an association between mild atherosclerosis and impaired endothelium-dependent coronary vasodilation (13). This is likely related to the adverse effects of coronary risk factors on vascular function (14) and its related effect on diffuse atherosclerosis, which has been shown to affect coronary artery physiology (15–17). The observed variability in MBF highlights the high sensitivity of these functional estimates to factors other than upstream epicardial stenosis (i.e., coronary risk factors, diffuse CAD, and microvascular dysfunction). This suggests that quantitative flow estimates are a sensitive but potentially not specific marker for obstructive epicardial CAD. In fact, our preliminary data in the per-patient– based analysis support this notion. The precise impact of this issue on subsequent referral for cardiac catheterization needs to be evaluated prospectively in a larger cohort. However, this observation may have potentially important prognostic implications beyond diagnosis, especially for those with diabetes and chronic kidney disease (18,19).

A third observation was that global quantitative estimates of MFR were sensitive markers for the identification of patients with high-risk anatomic disease by CTA, especially among patients with normal or low-risk myocardial perfusion scans on semiquantitative visual analysis, which is consistent with the increased sensitivity of MFR for detection of multivessel CAD (20,21). Although these consistent results are encouraging, they should be viewed as hypothesis generating because all these studies, including ours, are small. Larger studies with angiographic confirmation are warranted to evaluate the added value of quantitative flow measurements for the noninvasive diagnosis of CAD.

Study limitations

Our study consisted of an entirely physician referral– based, stable diagnostic population with an intermediate likelihood of CAD. As such, this study design and the nature of patients referred to stress imaging limit the generalizability of our results to other populations such as those with acute coronary syndromes. Larger prospective studies investigating the relationship between MFR and coronary atherosclerosis could help confirm or extend our findings. Catheter-based coronary angiography or intravascular ultrasound was not performed routinely in our patients, many of whom had normal PET scans on semiquantitative visual analysis. Quantitative MFR is currently not a routine component of our clinical assessments and reporting. However, previous studies have documented the value of CTA for assessing plaque morphology and vessel remodeling, as demonstrated by intravascular ultrasound.

Conclusions

There is a modest association between the severity of stenosis quantified by CTA and its associated impairment of downstream MFR. On a per-vessel analysis, other CTA-based descriptors of coronary atherosclerosis did not add incremental information beyond the quantitative percentage of diameter stenosis for predicting decreased MFR as a downstream measure of impaired tissue perfusion. However, on a per-patient basis, the extent of atherosclerosis as assessed by the modified Duke CAD index (integrating the site and severity of coronary stenosis) and the number of coronary segments with mixed plaque were associated with decreased MFR. The latter may reflect a link between noncalcified plaques as a surrogate marker of more diffuse coronary microvascular dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the Grants-in-Aid for Young Scientists (20790871) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (to Dr. Naya), the Society of Nuclear Medicine Wagner-Torizuka Fellowship (to Dr. Naya), the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research (to Dr. Naya), and a T32 training grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32 HL094301).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CT

computed tomography

- CTA

computed tomography angiography

- MBF

myocardial blood flow

- MFR

myocardial flow reserve

- PET

positron emission tomography

Footnotes

All authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:213–224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blankstein R, Di Carli MF. Integration of coronary anatomy and myocardial perfusion imaging. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:226–236. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Carli MF, Hachamovitch R. New technology for noninvasive evaluation of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2007;115:1464–1480. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.629808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato A, Hiroe M, Tamura M, et al. Quantitative measures of coronary stenosis severity by 64-slice CT angiography and relation to physiologic significance of perfusion in nonobese patients: comparison with stress myocardial perfusion imaging. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:564–572. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.042481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Fakhri G, Sitek A, Guerin B, Kijewski MF, Di Carli MF, Moore SC. Quantitative dynamic cardiac 82Rb PET using generalized factor and compartment analyses. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1264–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Fakhri G, Kardan A, Sitek A, et al. Reproducibility and accuracy of quantitative myocardial blood flow assessment with (82)Rb PET: comparison with (13)N-ammonia PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1062–1071. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.104.007831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller JM, Rochitte CE, Dewey M, et al. Diagnostic performance of coronary angiography by 64-row CT. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2324–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gould KL. Does coronary flow trump coronary anatomy? J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2009;2:1009–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Carli MF, Dorbala S, Curillova Z, et al. Relationship between CT coronary angiography and stress perfusion imaging in patients with suspected ischemic heart disease assessed by integrated PET-CT imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2007;14:799–809. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meijboom WB, Van Mieghem CA, van Pelt N, et al. Comprehensive assessment of coronary artery stenoses: computed tomography coronary angiography versus conventional coronary angiography and correlation with fractional flow reserve in patients with stable angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:636–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Carli M, Czernin J, Hoh CK, et al. Relation among stenosis severity, myocardial blood flow, and flow reserve in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1995;91:1944–1951. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.7.1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin F, Shaw LJ, Berman DS, et al. Multidetector computed tomography coronary artery plaque predictors of stress-induced myocardial ischemia by SPECT. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:700–709. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egashira K, Inou T, Hirooka Y, et al. Impaired coronary blood flow response to acetylcholine in patients with coronary risk factors and proximal atherosclerotic lesions. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:29–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI116183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campisi R, Di Carli MF. Assessment of coronary flow reserve and microcirculation: a clinical perspective. J Nucl Cardiol. 2004;11:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gould KL, Nakagawa Y, Nakagawa K, et al. Frequency and clinical implications of fluid dynamically significant diffuse coronary artery disease manifest as graded, longitudinal, base-to-apex myocardial perfusion abnormalities by noninvasive positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2000;101:1931–1939. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.16.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Bruyne B, Hersbach F, Pijls NH, et al. Abnormal epicardial coronary resistance in patients with diffuse atherosclerosis but “normal” coronary angiography. Circulation. 2001;104:2401–2406. doi: 10.1161/hc4501.099316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schindler TH, Facta AD, Prior JO, et al. PET-measured heterogeneity in longitudinal myocardial blood flow in response to sympathetic and pharmacologic stress as a non-invasive probe of epicardial vasomotor dysfunction. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:1140–1149. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giri S, Shaw LJ, Murthy DR, et al. Impact of diabetes on the risk stratification using stress single-photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with symptoms suggestive of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2002;105:32–40. doi: 10.1161/hc5001.100528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Mallah MH, Hachamovitch R, Dorbala S, Di Carli MF. Incremental prognostic value of myocardial perfusion imaging in patients referred to stress single-photon emission computed tomography with renal dysfunction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:429–436. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.831164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshinaga K, Katoh C, Noriyasu K, et al. Reduction of coronary flow reserve in areas with and without ischemia on stress perfusion imaging in patients with coronary artery disease: a study using oxygen 15-labeled water PET. J Nucl Cardiol. 2003;10:275–283. doi: 10.1016/s1071-3581(02)43243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkash R, deKemp RA, Ruddy TD, et al. Potential utility of rubidium 82 PET quantification in patients with 3-vessel coronary artery disease. J Nucl Cardiol. 2004;11:440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]