To the Editor: Body mass index (BMI) is widely used as a proxy for body fat and has been shown to correlate with other measures of adiposity.1 However, its use is limited by differences in body fatness for a given BMI across age, sex, and race.2–3 To address this limitation, Bergman et al. developed the body adiposity index (BAI) in samples of Mexican-Americans and blacks.4 However, no sex-specific information was provided, and it is unknown how well BAI performs in whites. We investigated the sex-specific relationship between both BMI and BAI and body fat in white and black adults.

Methods

The participants were mainly healthy volunteers recruited from the greater Baton Rouge area for metabolic studies from 1992 to 2011.5 This analysis included only adults with dual energy x-ray absorptiometry measures. Since a focus of the study was to understand racial differences, race was self-identified. The study was approved by the Pennington Biomedical Research Center’s institutional review board and participants provided written informed consent.

Height and weight were measured using a stadiometer and digital scale, respectively. Hip circumference was measured at the level of the trochanters. The BMI [weight (kg)/height (m2)] and BAI [hip (cm)/height (m1.5) - 18] were calculated. Fat mass (kg) and %fat were measured using a Hologic QDR4500 (n=1,549, 2001–2011) or QDR2000 scanner (n=2,302, 1992–2006); QDR2000 data were converted to QDR4500 output.5

Pearson correlations were computed among BAI, BMI, %fat, and fat mass within each sex-by-race group. A linear regression model was used to assess the relationship between %fat and BAI (or BMI), age, sex, and race. Interaction terms were entered into the model for sex*BAI (or BMI) and race*BAI (or BMI). BAI and BMI were standardized to zero mean and unit variance prior to analysis using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Level of significance was p<0.05, and statistical tests were 2-sided.

Results

The sample included 1,462 white women, 812 black women, 1,262 white men and 315 black men. The ages, BMI and %fat of the sample were (mean (SD) [range]) 41.0 y (13.4) [range 18–69], 29.4 kg/m2 (6.1)[range 17.2–57.7] and 32.0% (9.7) [range 7.8–55.9], respectively. The correlations with %fat across the 4 sex-by-race groups ranged from 0.75 to 0.82 for BAI and 0.80 to 0.83 for BMI, and the correlations with fat mass ranged from 0.77 to 0.86 for BAI and 0.90 to 0.96 for BMI (Table).

Table 1.

Mean (SD) values of BAI, BMI, %fat and fat mass and correlations [95% CI] among these variables in the four sex-by-race groups and the total sample.

| Mean (SD) | r* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAI | BMI (kg/m2) |

%fat | Fat Mass (kg) |

%fat & BAI |

%fat & BMI |

Fat Mass & BAI |

Fat Mass & BMI |

|

| Black Women (n=812) | 35.3 (6.3) | 31.6 (6.5) | 37.9 (6.0) | 32.8 (11.2) | 0.77 [0.74–0.80] | 0.80 [0.77–0.82] | 0.81 [0.79–0.84] | 0.94 [0.93–0.95] |

| Black Men (n=315) | 26.0 (4.2) | 28.6 (4.7) | 21.5 (6.9) | 20.2 (9.2) | 0.76 [0.71–0.80] | 0.80 [0.76–0.84] | 0.77 [0.72–0.81] | 0.90 [0.88–0.92] |

| White Women (n=1462) | 34.2 (6.9) | 29.2 (6.7) | 37.5 (7.3) | 30.3 (12.1) | 0.82 [0.80–0.83] | 0.83 [0.81–0.84] | 0.86 [0.85–0.88] | 0.96 [0.95–0.96] |

| White Men (n=1262) | 26.3 (4.4) | 28.5 (5.1) | 24.5 (7.2) | 23.1 (10.3) | 0.75 [0.73–0.77] | 0.81 [0.79–0.83] | 0.77 [0.74–0.79] | 0.91 [0.90–0.92] |

| Total (n=3851) | 31.1 (7.2) | 29.4 (6.1) | 32.0 (9.7) | 27.6 (11.9) | 0.85 [0.84–0.86] | 0.65 [0.64–0.67] | 0.83 [0.82–0.84] | 0.91 [0.90–0.92] |

all correlations statistically significant at p<0.001.

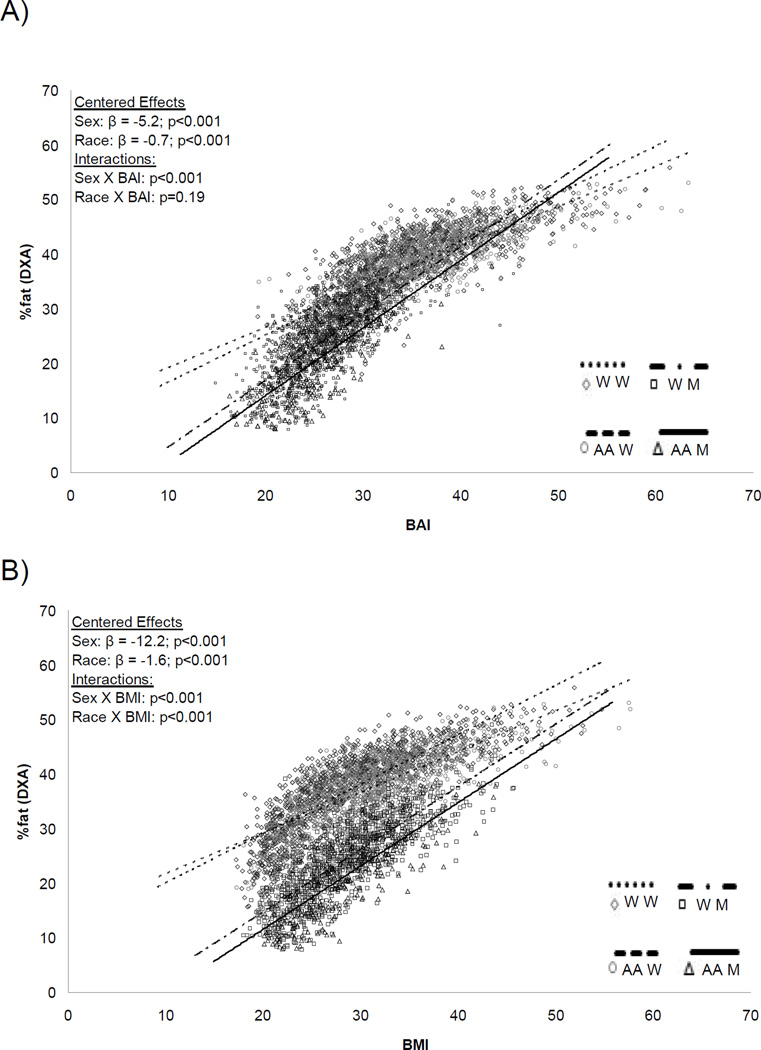

The regression model that included BAI explained 81.9% of the variance in %fat. The corresponding model for BMI explained 84.1%. Women had 5.2% and 12.2% more %fat than men (p<0.001) at the mean BAI and BMI, respectively, while whites had 0.7% and 1.6% more %fat than blacks (p<0.001) at the mean BAI and BMI, respectively. The race interaction term was not significant for BAI (p=0.19) but it was for BMI (p<0.001); however, both sex interaction terms were significant, indicating that the associations between BAI and BMI with %fat differed by sex, and by race for BMI (Figure).

Figure 1.

Percent body fat vs. A) body adiposity index (BAI) and B) body mass index (BMI) in race-by-sex groups. P-values for centered main effects and interactions are from a regression model including BAI (or BMI), age, sex, race, and sex*BAI (sex*BMI) and race*BAI (race*BMI) interactions.

Comment

BMI and BAI perform similarly in predicting body fat. In each sex-by-race group, the correlations with %fat and fat mass were similar for BMI and BAI. Moreover, the regression models including BAI or BMI explained a similar percentage of the variance in %fat. The sex and race differences in the relationship between both BAI and BMI with %fat make interpreting these measures in different population groups difficult. Our results are based on a sample of volunteers enrolled in clinical studies, and the representativeness of the results is not known. Neither BMI nor BAI measure obesity complications directly, and further research is required to determine the clinical significance of these measures.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported by the Pennington Biomedical Research Center. PK is supported, in part, by the Louisiana Public Facilities Authority Endowed Chair in Nutrition. This work was partially supported by an NORC Center grant #2P30-DK072476-06 entitled “Nutritional Programming: Environmental and Molecular Interactions” sponsored by NIDDK.

Role of the Sponsor: The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Additional Contributions: We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Emily Mire, MS and Connie Murla, BS for data management and the many clinical scientists and staff of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center who have contributed data to the Pennington Center Longitudinal Study, particularly Dr. Steven R. Smith, MD. Emily Mire, Connie Murla and Dr. Smith were all employees of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center and did not receive compensation beyond their normal salary.

Footnotes

Author Affiliations: All authors are affiliated with the Pennington Biomedical Research Center.

Author Contributions: Dr Katzmarzyk had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Barreira, Harrington, Staiano, Heymsfield, and Katzmarzyk

Acquisition of data: None

Analysis and interpretation of data: Barreira, Harrington, Staiano, Heymsfield, and Katzmarzyk

Drafting of the manuscript: Barreira, Harrington, Staiano, Heymsfield, and Katzmarzyk

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Barreira, Harrington, Staiano and Katzmarzyk

Statistical analysis: Barreira and Katzmarzyk

Obtained funding: None

Administrative, technical, or material support: None

Study supervision: Katzmarzyk

Financial Disclosure: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. None reported.

References

- 1.Bouchard C. BMI, fat mass, abdominal adiposity and visceral fat: where is the 'beef'? Int J Obes. 2007;31(10):1552–1553. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camhi SM, Bray GA, Bouchard C, et al. The relationship of waist circumference and BMI to visceral, subcutaneous, and total body fat: sex and race differences. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19(2):402–408. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson AS, Stanforth PR, Gagnon J, et al. The effect of sex, age and race on estimating percentage body fat from body mass index: The Heritage Family Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(6):789–796. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergman RN, Stefanovski D, Buchanan TA, et al. A better index of body adiposity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19(5):1083–1089. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katzmarzyk PT, Bray GA, Greenway FL, et al. Racial differences in abdominal depot-specific adiposity in white and African American adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(1):7–15. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]