Abstract

Rarely are within-group differences among African American men explored in the context of mental health and well-being. Though current conceptual and empirical studies on depression among African American men exists, these studies do not offer a framework that considers how this disorder manifests over the adult life course for African American men. The purpose of this article is to examine the use of an adult life course perspective in understanding the complexity of depression for African American men. The proposed framework underscores six social determinants of depression (socioeconomic status, stressors, racial and masculine identity, kinship and social support, self-esteem and mastery, and access to quality health care) to initiate dialogue about the risk and protective factors that initiate, prolong, and exacerbate depression for African American men. The framework presented here is meant to stimulate discussion about the social determinants that influence depression for African American men to and through adulthood. Implications for the utility and applicability of the framework for researchers and health professionals who work with African American men are discussed.

Keywords: African American males, depression, developmental influences, life course, male development, mental health, social determinants

Three decades of research on African American males has documented the challenges they face in academic achievement, their performance in appropriate family and societal roles, the maintenance of their physical and mental health, and the deleterious effects of racism on their daily lives (Bonhomme, 2004; Bowman, 1989; Erguner-Tekinapl, 2009; Pierre & Mahalik, 2005; Pieterse & Carter, 2007; Williams, 2003; Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000). Yet few studies have presented an in-depth examination of these developmental issues over the adult life course for African American men. For example, despite the advantages of age-specific strategies for mental health promotion and disease prevention, few studies have investigated potential life stage–related differences in factors influencing mental health over the adult life course for African American men (Gadsden & Trent, 1995; Pettit & Western, 2004). An even smaller number of studies have discussed projected patterns within age-linked life stages for African American men and the relationship between the conditions of their formative years and their mental health (Bentelspacher, 2008; Mizell, 1999a, Mizell, 1999b; Watkins, Hudson, Caldwell, Siefert, & Jackson, 2011).

Age-linked life stages are time segments over the life course where groups of individuals share commonalities with regard to age- and behavior-specific tasks and accomplishments. Examples include the experiences individuals share during their college years, while entering the workforce through entry-level jobs, and during retirement. These experiences may differ for members of some racial and ethnic groups, and variations may also occur by gender. For example, some studies suggest that the chronic role strains faced by young African American males as adolescents and young adults can translate into severe provider role strains when they reach middle adulthood (Bowman, 1989; Williams, 2003). Thereby, the health and social well-being of their early years directly influence the challenges faced by African American males into and throughout adulthood.

Examining African American men’s mental health from a life course perspective is an innovative approach to understanding how events from their youth and early adulthood influence their mental health outcomes as they age. Toward advancement in this neglected area, this article will examine the use of an adult life course perspective in understanding the complexity of depression and present a framework that underscores the social determinants of depression for adult African American men. The aim of proposing a depression framework over the adult life course is to provide an exploratory framework that patterns the risk and protective factors that initiate, prolong, and exacerbate depression for African American men. Attentiveness to this perspective will help underscore the steps needed to progress this area of inquiry and inform researchers and health professionals about what is needed for African American males to achieve positive mental health status as they transition from youth into early, middle, and late adulthood. Implications for depression research and programs for African American men—whose perceptions of depression and health care systems may influence their decisions regarding preventive care, diagnoses, and treatment in health care settings—are also discussed. Before beginning, it is important to note the variation in the terms used to describe men of African descent in mental health research. Previous studies have used the term Black to describe an all-inclusive group of individuals that include various ethnicities of African descent (i.e., African Americans, Caribbeans, Jamaicans, Haitians, etc.). Because of the complexities around studying various ethnic groups of Black men (e.g., nativity, immigration status), here, the discussion is restricted to only those who identify as African American men.

The Complexity of Depression for African American Men

Mental health is defined as a state of well-being where one realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with normal life stressors, can engage in work productively and fruitfully, and is able to contribute to his or her community (World Health Organization, 2001). Alternatively, mental disorders are “health conditions that are characterized by alterations in thinking, mood, or behavior (or a combination thereof) associated with distress and/or impaired functioning” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999, p. 5). Epidemiologic studies have shaped reports on mental disorders across racial and ethnic groups. Overall, rates for mental disorders are reportedly higher among Whites compared to African Americans (Kessler et al., 1994; Kessler et al., 2003). Yet withingroup disparities exist for specific disorders. For instance, studies have suggested that major depressive disorder for African American men (7%) is lower than that of African American women (13.1%) and White men (16.2%) and women (19.5%; Williams, Gonzalez, et al., 2007). The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study reported high 1-year prevalence rates for African American women compared to African American men across several mental disorders, including major depression with no grief (4.9% vs. 1%) and major depression with grief (5.1% vs. 1.1%; Brown & Keith, 2003).

Findings from the National Comorbidity Study identified gender differences among African Americans, with women scoring higher than men for 1-year prevalence rates of major depression without hierarchy (11% vs. 5%). The National Comorbidity Study also reported that African American women scored higher than African American men for lifetime prevalence of major depression without hierarchy, 15.5% versus 7.3%, respectively (Brown & Keith, 2003; Kessler et al., 1994). Though these studies reported lower prevalence rates for mood disorders for African Americans compared to Whites, overall, some have suggested that the course and persistence of these disorders may be more chronic for African Americans than they are for Whites (Williams, Haile, et al., 2007). Findings such as these suggest that the impact of African American’s psychological health may not be as harmful as that of White men and women. However, looking beyond the prevalence rates and more deeply into the culture- and gender-specific antecedents—as well as social determinants of these disorders—may suggest particularly deleterious mental health outcomes for African American men (Keating, 2009).

A number of challenges surface when the mental health of African American males are examined for the purposes of research and practice (Keating, 2009). As such, the complexity of disorders such as depression as well as how it manifests across race, culture, and gender norms presents a multilayered phenomenon for African American males. For instance, little is known about the extent to which African American men subscribe to the definition of mental health described above by the World Health Organization (2001). In addition, conformity or nonconformity to certain racial, cultural, and gender norms may either permit or prohibit adherence to this mainstream understanding of mental health for certain subgroups of African American men. The etiology and symptomatology of mental disorders are influenced by the complex nature of what it means to be both an African American and a man, thereby making it difficult to diagnose, treat, and monitor a race and gendered phenomenon such as depression.

Despite the complexity of depression for African American males, a number of studies have attempted to understand the factors that lead to depression and depressive symptoms for this subgroup of men (Kendrick, Anderson, & Moore, 2007; Rich & Grey, 2005; Royster, Richmond, Eng, & Margolis, 2006; Watkins, Green, Goodson, Guidry, & Stanley, 2007; Watkins, Green, Rivers, & Rowell, 2006; Watkins & Neighbors, 2007). Previous studies have also explored factors that lead to psychological distress and overall poor mental health among African American males, specifically, their negative attitudes toward the criminal justice system (Gaines, 2007; Pettit & Western, 2004), racism and discrimination (Pierre & Mahalik, 2005; Pieterse & Carter, 2007), and issues surrounding masculinity (Courtenay, 2001; Pierre, Mahalik, & Woodland, 2002). Greater knowledge of risk and protective factors for African American males at different adult life stages can improve our understanding of the problems that lead to poor mental health and more severe disorders such as depression. Though other mental disorders plague African American men (Joe, Baser, Breeden, Neighbors, & Jackson,2006; Whaley, 2004), here, the social determinants of depression are examined. The adult life course perspective was chosen to address the manifestation, symptomatology, and identification of depression that may initiate in their youth and then subsequently continue through stages of adulthood.

The Adult Life Course Perspective and African American Men

Life course theory proposes that health and well-being are determined by multiple contexts that change as a person develops and that cumulative risk and protective factors lead to different life trajectories (Halfon & Hochstein, 2002; Kuh, Power, Blane, & Bartley, 2003). This perspective is guided by the notion that any single threat, on its own, appears to have only moderate impact on quality of life. However, an accumulation of these threats is what has greater impact on poor health over time (Blane, Higgs, Hyde, & Wiggins, 2004). The life course is a sequence of age-linked transitions and includes times when social roles change; new rights, duties, and resources are encountered; and identities fluctuate (Settersten, 2004).

The life course health development perspective proposes the sequencing of events across an entire lifetime and also accounts for intergenerational influences (Halfon & Hochstein, 2002). “Health development” in this context is defined as a lifelong adaptive process that builds and maintains optimal functional capacity and disease resistance. A better understanding of how health develops over the life course enables the manipulation of early risk and protective factors and helps shift the emphasis on treatment in the later stages of disease to the promotion of earlier, more effective preventive strategies and interventions for optimal health development. Halfon and Hochstein (2002) outlined three key components to the scientific understanding of life course health development: the importance of embedding (experiences programmed into the structure and functioning of biological and behavioral systems), various health outcome determinants (multidimensionality and complexity of causation), and functional trajectories.

Life course scholars have divided adulthood into early, middle, and late adult stages as a way to understand the respective demands and benefits that occur at each life stage (Clarke & Wheaton, 2005). Such adult life stages are primarily age based and the issues that arise at each stage are defined in terms of the prevailing age-associated tasks, problems, and goals. The first stage of adulthood (often referred to as the sorting period) can begin anywhere between age 16 and age 30 and can last between 5 and 10 years after the end of one’s education. This stage is marked by “uncertainty, transience, choice, and turnover in relationships, roles, and jobs” (Clarke & Wheaton, 2005, p. 271). Though the 20s have also been referred to as the “new adolescence” (Arnett & Taber, 1994), modern times have found individuals in their 20s using that time as a time of sorting, as it tends to be filled with decisions regarding marriage, parenting, and career choices. For African American males, this sorting stage can be especially demanding as social and environmental conditions may shape how they understand and identify with their aspiring roles, relationships, and jobs. During this time African American males may be faced with the idea of “becoming” who they are as men as determined by their situations and surrounding role models (Aronson, Whitehead, & Baber, 2003; Hammond & Mattis, 2005; Hunter et al., 2006; Mankowski & Maton, 2010). Likewise, during this stage African American men may begin to absorb and assimilate to their understanding of differences across race and gender (Bowman, 1989; Watkins, Walker, & Griffith, 2010).

An adjoining, yet different life stage is one that occurs after the sorting period stabilizes. This stage of adulthood is considered the developmental period and is marked by an expansion of responsibilities and commitments within roles and a push toward achievement in the choices made during early adulthood (Arnett & Taber, 1994; Clarke & Wheaton, 2005). During this stage, the most clearly distinguishing differences occur with respect to employment, marriage, and parenting. Furthermore, during the developmental period, the paths that individuals started on with their peers during earlier life stages tend to diverge (Clarke & Wheaton, 2005). For some African American men, this could be a time when one’s peers diverge into lifestyles that focus on different types of goal attainment, such as educational attainment, sports, the arts, an immersion into the blue- or white-collar workforce, or commitment to providing for one’s family.

The next life stage—middle adulthood, or the “midlife period”—is the stage that occurs after age 40 (Brim, Ryff, & Kessler, 2004 This life stage is marked by specific choices concerning work and family decisions beyond age 65, with the potential for redirection. For African American men, middle adulthood could be the stage during which work and social functioning take shape. During this period, men may be more secure in their careers and established relationships than they were during the developmental stage. Also during this stage, African American men may experience more discrimination and workplace stress as of a result of their conformity to mainstream society’s definitions of and markers for success (Watkins et al., 2011). Later life is defined as the “winding down” period when the experience of disengagement, influenced in part by losses in physical functioning and social roles occurs (Schieman, Van Gundy, & Taylor, 2001). Later adulthood signifies a clear change in the direction of life events that may plateau during middle adulthood. For African American men, as with most individuals, the measures of success that were important during the developmental stage and midlife stage are less important during later life stages. As such, men may be more focused on winding down and enjoying the fruits of their labor while in retirement. For some men, this winding down period is met with unanticipated life choices as a result of their early life decisions. For example, men may find themselves needing to reengage into the workforce if they are faced with a fixed income, health challenges, or financial strain beyond their control (Bowman, 1989; Watkins et al., 2010; Watkins et al., 2011).

Examining depression in African American men over the adult life course is proposed because it is broadly defined in terms of early, middle, and later stages of adulthood (Clarke & Wheaton, 2005). Unlike childhood or other single phases of life, during adulthood individuals live for 50 or more years after adolescence (Levinson, 1990). Therefore, rather than studying adulthood as a single, unitary stage of life, previous studies have suggested that it be conceptualized as a series of stages that considers sequencing of life events guided by socialization, adaptation, and personality development through adulthood. Self-actualization is a part of adult development and is often the result of circumstances of one’s early years (Clarke & Wheaton, 2005; Levinson, 1990) that manifests into personal satisfaction with the execution of rights, duties, and social roles. The healthy progression through adult life stages for African American men may largely depend on the successful resolution of conflicts and mastery of tasks at each stage of adult development (Bentelspacher, 2008; Bowman, 1989; Watkins et al., 2011). For instance, the forces influencing the likelihood that African American men may ever experience depression begins early in their lives and is linked to childhood deprivation, whether material or psychosocial, and to the accumulation of life course disadvantage (Pierre & Mahalik, 2005; Pierre et al., 2002; Pieterse & Carter, 2007). The social and economic hardships many young African American males face, along with the marginalized roles within their families and communities (Howard-Hamilton, 1997; Plowden, John, Vasquez, & Kimani, 2006; Rich, 2000), may restrict the activation of protective factors on their mental health and well-being. Positive mental health for adult African American males involves transitioning from the identities of their youth to identities that define who they are as adults.

Consistently, studies have reported that the risk and protective factors children experience have a lasting impression on their health as adults (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002; Singer & Ryff, 2001). A number of studies have examined the mental and physical health of African American males of various age-linked life stages (Griffin, 2000; Love & Love, 2006; Mizell, 1999a, 1999b; Roy, 2006; Utsey, Payne, Jackson, & Jones, 2002; Watkins & Neighbors, 2007). However, only recently have studies examined within- and between-group differences with regard to mental health outcomes among African American men. For example, studies suggest that younger African American men experience psychological distress and depression at higher rates than older African American men do, which has implications for early interventions (Lincoln, Taylor, Watkins, & Chatters, 2011; Watkins et al., 2011). Despite these findings, few studies have considered the adult life course and how the risk and protective factors at early adulthood influence the mental health of African American men in later adulthood.

Toward a Understanding of Depression in African American Men Over the Adult Life Course

Social determinants that lead to poor mental health for African American males are often the result of early exposures to poor social and economic conditions that adversely affect mental health and play a significant role in the etiology of mood disorders in adulthood (Watkins et al., 2010; Williams, 2003). Previous studies accentuate the need for a focus on prevention at early adult life stages and intervention at all adult developmental stages for African American men (Plowden et al., 2006; Ravenell, Johnson, & Whitaker, 2006; Watkins et al., 2011). To this end, examining depression in African American men over the adult life course may provide a unique context for understanding ways in which the trajectory takes place as the men transition to and through certain age-specific task accomplishments. Young African American males encounter a number of stressful life events (i.e., racism, violence, economic marginalization) that influence their mental health (Mizell, 1999a; Rich, 2000; Watkins et al., 2007; Watkins & Neighbors, 2007; Williams, 2003). Furthermore, higher levels of depression during adulthood have been associated with psychosocial stressors, low self-esteem, low mastery levels, low monetary earnings, and negative life events for African American male adolescents (Mizell, 1999b). As African American males transition from adolescence to adulthood, they often experience an awareness of restricted educational, economic, and social opportunities that contribute to increased stress and maladaptive coping patterns (Williams, 2003).

Empirical examinations of evidenced-based strategies for understanding and working with depression in African American males are desolate in the literature. Instead, large, epidemiologic studies tend to report varied depressive scores for African American men as they age (Lincoln et al., 2011; Watkins et al., 2011). What these studies do not report are details surrounding the determinants and behaviors during early adulthood that would influence the likelihood of African American men experiencing depression or depression reoccurrence. Unfortunately, longitudinal data on African American males are rarely available, and cross-sectional studies seldom report patterns within life stages, making it difficult to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the social determinants of depression and outcomes as they pertain to African American men. Buffering effects of potentially damaging social determinants are needed and could be highly informative to the health professionals who work with African American men and the researchers who study them. In subsequent paragraphs, a culturally appropriate and gender-sensitive framework is proposed to initiate the discussion about how researchers and health professionals can move toward understanding the trajectory of depression in African American men over the adult life course.

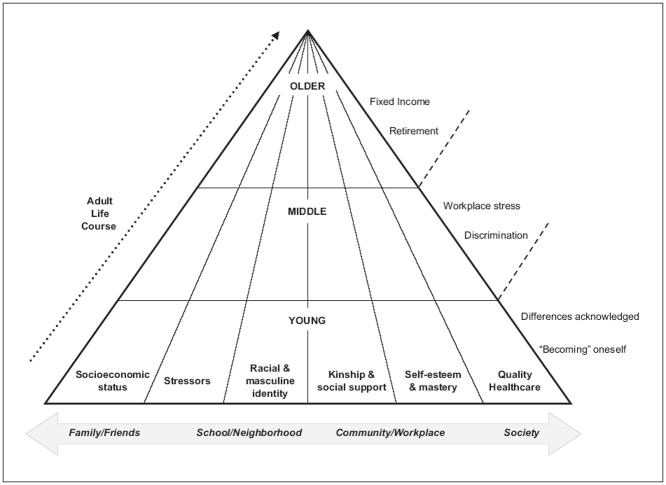

Six social determinants and how they influence the depression trajectory for African American men in the socioecological context of family and friends, school and neighborhood, community and workplace, and society are discussed (see Figure 1). Although a number of social determinants influence depression for African American men, the proposed framework presents six social determinants selected due to their recurrent presence in the literature (Hammond & Mattis, 2005; Oliver, 2006; Pierre, Mahalik, & Woodard, 2001; Plowden et al., 2006; Ravenell et al., 2006; Wade, 2008; Watkins et al., 2006; Watkins et al., 2010; Watkins & Neighbors, 2007). The social determinants presented in this framework are socioeconomic status (SES), stressors, racial and masculine identity, kinship and social support, self-esteem and mastery, and access to quality health care. These social determinants are not meant to serve as an exhaustive list of the factors that influence depression for African American males over the adult life course. Rather, this list should guide a more focused discussion about the social determinants of depression for adult African American men and provide a context with which interpretations can be made about other social determinants.

Figure 1.

A framework for conceptualizing depression for African American males over the adult life course

Socioeconomic Status

Economic marginalization has long-term negative consequences on the health of African American males. Because of the marginal effects of SES over the adult life course for African American males, research and programmatic efforts toward decreasing the prevalence for and consequences of depression for African American men should be approached using an adult life course perspective. For young African American males, SES is largely influenced by their parents’ education levels and household incomes (Mizell, 1999b). Thereby, their mental health is the result of generational successes and failures in terms of economic prosperity and can lead to comparable SES in early adulthood. In middle adulthood, African American males obtain a level of SES that is a result of their own educational attainment and management of finances. Oftentimes, the economic status of adult African American men at this life stage is a reflection of the financial lessons learned during their youth and thus influences their ability to monitor and care for their mental health as they age. For a number of men, self-care and personal wellness are not priorities due to the pressures of being a financial role provider for the household. Therefore, it becomes easy for these men to neglect their mental health in exchange for taking on the responsibilities associated with the role of the provider. Some African American males may assume the responsibility of financial provider for their households sooner than other males, thereby increasing their SES and potentially leading to increased levels of stress and poor mental health as they age (Bowman, 1989; Williams, 2003). Since men are more likely to delay seeking care for their health problems (Courtenay, 2001), financial security and economic advancement may be a prerequisite for obtaining optimal health care services for some African American men.

A succession of negative life events and pressing economic hardships may mean that African American men in late adulthood encounter fixed incomes due to retirement and the need to manage and adjust their lifestyles. Positive mental health for older African American men may also require the ability to cope with the financial successes and failures from earlier life experiences that have resulted in joy or despair (Bowman, 1989). Therefore, although depression management programs aimed at men in early and middle adulthood could focus on the successful acquisition and management of money and other material assets, older African American men may benefit most from programs aimed at health care and social services, including income and retirement services (Watkins et al., 2010; Williams, 2003). Also, due to the likelihood of a fixed income, strategies to assist African American men in late adulthood with the management of their finances in an era of challenging health care and fluctuating prescription costs would be advantageous. Though there is evidence of the association between low SES and depression for African American men (Watkins et al., 2006), more efforts should be made toward understanding how their SES during youth and early adulthood affects the likelihood of experiencing depression and depression reoccurrence as they age. As life presents challenges and economic uncertainly prevails, it is essential to understand how potential stressors associated with African American men’s ability to obtain and maintain financial security pose as risk factors for depression.

Stressors

There are several stressors associated with life transitions and the personal and professional development of African American men (Bowman, 1989). Moreover, just the nature of being both African American and male may yield experiences that vary compared to African American women and men from other racial and ethnic groups (Watkins et al., 2010). Here, three stressors commonly presented in the depression literature on adult African American men are presented: racial discrimination, violence, and incarceration.

Racial discrimination

Racial discrimination and its subsequent consequences strongly influence the mental health of underrepresented individuals, their families, and their communities (Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000). For some African American men, the blatant reality of racial discrimination results in challenging and unpleasant life course experiences compared to men of other racial and ethnic groups. The intersection of debilitating forces, such as racism, oppression, and poverty, mean that African American men may lack the resources and opportunities needed to recognize their true potential (Hattery & Smith, 2007) and address the challenges associated with maintaining their mental health. Furthermore, and as a result of racism, African American men endure a range of challenges in their lives and role performances that lead them to create alternative lifestyles (Oliver, 2006; Payne, 2006; Payne, 2011). Understanding the difference between issues of “race” and “racism” is an essential first step for dealing with racial discrimination among African American males (Karlsen, 2007). For example, the historical impact of racism in the context of migration, alienation, and the way in which African American men are stigmatized in society is an important step in dealing with the mental health challenges of African American men.

In terms of the life course, resiliency against racism and other social and emotional challenges among young African American males is a protective factor for depression in adulthood (Mizell, 1999a, 1999b). It is during their youth that African American males may experience their first bout with racial discrimination. Therefore, efforts toward understanding discrimination as a result of racism and its influence on the psychological health of African American men (Mahalik, Pierre, & Wan, 2006) will help researchers and providers develop methods for early intervention and improved resiliency against its harming psychological effects. Studies have found that African American men between the ages of 35 and 54 may experience more racial discrimination than their younger and older counterparts (Watkins et al., 2011). Therefore, efforts for this group should focus on preventive measures that address racism, both individually and collectively. African American men at this life stage may experience racial discrimination in the workplace and preventive measures against the social and emotional challenges that they experience as a result of racial discrimination is an important step toward improving mental health and reducing the occurrence and reoccurrence of depression (Watkins et al., 2011). For older African American men, the ability to cope with earlier life experiences is a useful approach to reducing and/or eliminating the lasting effects of racial discrimination (Bowman, 1989). In addition, the recent economic downturn suggests that some African American men in late adulthood still have a presence in the workforce and therefore may experience prolonged effects of racial discrimination that may not have been experienced by previous cohorts of African American men in this age group. Research and programmatic efforts that highlight the lived experiences of older African American males as a result of discriminatory events from their past would be a unique approach to understanding depression.

Violence

Violence and homicide are leading causes of death for African American men. Some African American men are more likely than men of other racial and ethnic groups to participate in violent acts rather than demonstrate their dominance through professional and economic achievements (Pearson, 1994; Whaley, 1998). Over the life course, many African American men participate in “street life” as a way to help them establish their reputations as well as convey symbolic and overt displays of masculinities (Oliver, 2006). “Street life” in this context is defined as the network of public and semi-public social settings (e.g., street corners, bars, after-hours locations, drug houses, and vacant lots) that serve as important influences on the psychosocial development and life course trajectories and transitions of African American males (Oliver, 2006; Payne, 2006, Payne, 2011). It is through “the streets” that many African American males develop interpersonal skills, rights, and behaviors that they apply to school, their communities, the workplace, and society.

The relationships that occur as a result of “street life” are oftentimes the negative undertone for the violence that erupts in the lives of African American men. For example, in “the streets,” violence is often used as a means to resolving disputes (Majors & Billson, 1992). Therefore, African American men who enter “the streets” in early adulthood may be groomed to handle their disputes using violence as opposed to more constructive ways of conflict resolution. Exposure to violence leads to psychological distress in young African American males (Paxton, Robinson, Shah, & Schoeny, 2004) and is also linked to depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation as they age. Maintenance of “street life” and street life–related behaviors may mean that African American men in middle and late adulthood are challenged with how to maintain healthy relationships with others due their gravitation toward violence as a means to handle their problems. Therefore, the effects of violence on the psychological health of African American men in early, middle, and late adulthood should be included in the conceptualization of how depression manifests for African American men.

Incarceration

The involvement of African American males in “street life” (Oliver, 2006) is also associated with their high rates of incarceration. Class inequalities widened between the 1980s and 1990s, during which the frequency of imprisonment overshadowed that of military service and college graduation for birth cohorts of African American males (Pettit & Western, 2004). For more than three decades, African American men have remained the most disproportionately incarcerated group compared with men of other racial and ethnic groups, constituting about 45% of the prison population (Harrison & Karberg, 2004). In terms of the life course, African American men have a 32% chance of going to prison at some time in their lives, compared with just 6% for White men (Bonczar, 2003). African American men are also approximately seven times more likely than White men to have a prison record (Pettit & Western, 2004).

Few African American male role models are left in Black communities due to widespread incarceration. Furthermore, incarceration leads to a significant reordering of the life course that can have lifelong effects on African American men. For instance, the high risk of imprisonment for African American men distinguishes the early adulthood of African American men from the life course of others in more ways than military enlistment, marriage, or college graduation (Pettit & Western, 2004). In fact, some scholars argue that the mass imprisonment of non–college African American men should be included in the discussion of life course and influence the social contexts with which key institutional influences on African American men’s social inequality are described (Pettit & Western, 2004).

The association between imprisonment and poor mental health is lucid. Sixteen percent of individuals in jail and prison have a mental illness (Ditton, 1999). Likewise, individuals who are substance users, unemployed, have lower incomes, and have fewer years of education are at greater risk for incarceration (Draine, Salzer, Culhane, & Hadley, 2002). Unfortunately, the experience of incarceration for some African American men has become somewhat of a rite of passage into manhood (Whitehead, 2000) and a disproportionate number of these incarcerated individuals are African American men who suffer from depression and could benefit from programs that treat them as both criminal offenders and recipients of mental health services.

Racial and Masculine Identity

Racial identity

Literature on self-esteem in African Americans has focused on African self-consciousness, examining the importance of developing knowledge of African American culture and recognizing factors that affirm Black life (Parham, White, & Ajamu, 2000; Pierre & Mahalik, 2005; Pierre, Mahalik, & Woodard, 2001). For example, Pierre and Mahalik (2005) argued that African self-consciousness is positively related to self-esteem and that positive attitudes about race may serve as a protective factor for African American males by providing them with a positive sense of self and self-affirmation. Studies on race and gender suggest that race plays an essential role in mental health outcomes for Blacks and that it is a marker for mental health, health behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs (Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000). A number of studies have identified the importance of positive aspects of racial identity in reducing the effects of psychological distress for African American males (e.g., Mahalik et al., 2006; Nghe & Mahalik, 2001; Wester, Vogel, Wei, & McLain, 2006). However, few studies consider the relationship between racial identity and depression among African American males. African American youth must develop a sense of racial or ethnic identity (Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998), which is often heightened during early adulthood. During middle adulthood, identity becomes even more of a combination of what African American men were exposed to during their youth as well as their own interpretation of what it means to be an African American man. Academic and career achievements can also influence the identity and mental health status for African American men in middle adulthood. In late adulthood, the mental health behaviors and trajectories established early in their lives are strongly influenced by their racial identity.

The role of “provider” is an important aspect of racial identity for African American men (Bowman, 1989), though it can result in a form of identity-related stress. Some African American men may experience psychosocial stressors associated with perceived roles and responsibilities in the context of their environments. Not only do these men render less desirable partners that lead to relationship disruption resulting in high divorce rates, female-headed families, out-of-wedlock births, less commitment of men to relationships, and negative perceptions of African American men by African American women (Tucker & Mitchell-Kernan, 1995), but this type of identity-induced stress results in some African American men being limited in their ability to serve as responsible husbands and father figures (Oliver, 2006). Studies have found that the inability to perform their roles in the household may lead to depression in African American men (Bowman, 1989). The behaviors of male role models may be monitored closely by African American males during their youth and then practiced once they, themselves, reach early adulthood (Watkins & Neighbors, 2007). If not successfully executed, the result can be the inability to cope with stressors that lead to poor mental health and more severe mental disorders such as depression.

Masculine identity

Young African American males are influenced by their peers and role models when developing their masculine identities. Whether positive or negative, the construction of masculine identity for young African American males becomes a by-product of what it means to be a man as illustrated through their social circles and what they see in the media (Franklin, 1986; Watkins & Neighbors, 2007). By the time an African American male reaches early adulthood, he has had a number of experiences that help shape his masculine identity and his conformity or nonconformity to masculine norms. Conformity to masculine norms may produce benefits for the African American male by fostering acceptance from social groups and by providing social and financial rewards. Conformity to masculine norms may also negatively affect African American men and may result in a man being described by others as emotionally distant and interpersonally dominant in his relationships. Nonconformity to masculine norms can reduce psychological distress (Mahalik, Good, & Englar-Carlson, 2003) as well as problems such as violence, high-risk behaviors, and absent fathering—all problems associated with poor mental health and that can exacerbate mental disorders for African American men.

Programmatic efforts that consider the social construction of manhood are believed to empower African American men to care for their health (Rich, 2000). Evidence suggests that males who endorse more traditional masculine ideologies also experience poorer self-esteem, problems with interpersonal intimacy, greater depression and anxiety, abuse of substances, problems with interpersonal violence, as well as greater overall psychological distress (Addis & Mahalik, 2003; Franchina, Eisler, & Moore, 2001; Phillips, 2006). Consistently, the literature has suggested that African American males endorse traditional masculine ideologies (Abreu, Goodyear, Campos, & Newcomb, 2000; Courtenay, 2001) and may experience poor mental health, at least in part, due to their tendency to adhere to traditional masculine norms that promote avoidance of medical care (Royster et al., 2006; Watkins & Neighbors, 2007; Watkins et al., 2007). By the time men reach middle and late adulthood, they will likely maintain the masculine identities that they established during the early years of their life. In other words, if African American males adopt a set of traditional masculine ideologies in their youth and these ideologies do not undergo some sort of modification during middle adulthood, they may be less likely to change as they age. For some aging men, the modification of their traditional masculine identity occurs during the start of health challenges, as during this time they may need to depend more on others (e.g., children and significant others) for their daily needs. For others, despite the downturn in their health, they may maintain the traditional masculine identities that they established in years prior. Research and services that support the development, modification, and maintenance of health-promoting masculine ideologies over the adult life course for African American men will help improve and maintain their mental health and protect them from challenges associated with depression.

Kinship and Social Support

For African American men, understanding the positive and negative aspects of kinship and social support in mental health status is a critical piece to understanding depression (Watkins & Neighbors, 2007). An important part of the functionality of the Black home is the involvement of a large network of kinship and family support such as uncles, aunts, preachers, and significant others (White, 2004). Regarding mental health, studies have found that high levels of critical and intrusive behaviors by family members predicted better mental health outcomes for African Americans when compared to Whites (Rosenfarb, Bellack, & Aziz, 2006). The authors of these studies affirm that the cultural beliefs of Black families suggest that confrontation is an expression of concern. Therefore, when more people are involved in one’s personal matters, they do so because they care about the individual and want to be helpful. Consider the influence of significant others in the mental health of African American men. Several studies have suggested that marriage is psychologically beneficial for African American men (e.g., James, Tucker, & Kernan, 1996) such that separated and divorced African American men have higher rates of depression than their married counterparts. Relative rates of psychiatric disorder are also higher in separated, divorced, and never-married African American men when compared to nonmarried African American women and their peers (Williams, Takeuchi, & Adiar, 1992). Beyond their significant others, equally important to the mental health status of African American men are their extended social support networks.

Existing research on the social support networks of African American men is limited and usually involves the relationships of socially marginalized men, such as those involved in gang activity (Mac An Ghaill, 1994), street life (Oliver, 2006; Payne, 2011), the criminal justice system (Gaines, 2007), homeless men (Littrell & Beck, 2001), and low-income nonresidential fathers (Anderson, Kohler, & Letiecq, 2005). Despite these limitations in the research, kinship and social support are especially important for maintaining a sense of community and support for issues surrounding the health of African American men (Plowden et al., 2006; Plowden & Young, 2003). For example, Plowden and Young (2003) suggested that the influence of members of support networks is a critical social factor in motivating their sample of urban African American men to seek health care and participate in health-related activities. A 2006 study by Plowden and colleagues also identified the influence of “trusted and respected individuals,” (e.g., family, political officials, and members of the media) in men’s health decisions. Respondents indicated that beyond race, men with whom they shared common characteristics (e.g., economic status and age) were influential in helping them navigate to and through their health needs. Kinship and social support will benefit African American men across all stages of adulthood and efforts to include members of social support networks in research and programs for African American men would be advantageous.

Self-Esteem and Mastery

Greater self-esteem among adolescent African American males can lead to an increase in their resilience for depression in adulthood (Mizell, 1999a). This underscores the influence of early self-concept on adult mental health and the significance of life course perspectives in examining the effects of early life determinants on later adulthood. Given the greater number of psychosocial stressors encountered by African American men, high self-esteem may be predictive of positive mental health (Franklin & Mizell, 1995; Watkins et al., 2011). In addition to self-esteem, higher levels of Black consciousness may also be linked to increased mastery among young African American males (Okech & Harrington, 2002; Pierre & Mahalik, 2005).

Young adulthood may be a time of social and environmental challenges for many African American males (e.g., high levels of under or unemployment, disproportionate imprisonment, and nonmarital births). Nevertheless, at this stage they may be more resilient in terms of their beliefs about controlling their own destiny than at any other life stage. It is during this stage of development that the identities of early adults begin to take shape and they establish a sense of who they are as separate from their families (Watkins et al., 2011). Gender and culture-related aspects of self-conceptions emerge as critical markers for African American males at early adulthood that have implications for their mental health as they age. Specifically, as young African American males enter adulthood, they are met with a number of psychosocial factors that influence their self-identification and self-efficacy. Learned empowerment and approaches to cope and manage their own mental health is most important for African American males during early adulthood.

A strong sense of mastery is protective against the development of depression and other mental disorders among African American men (Baker, 2001; Watkins et al., 2011). For example, some studies argue that young African American males may compensate for low self-esteem through the mastery of certain tasks and that for African American males individual adult achievement and adult mastery provide defenses against depression (Mizell, 1999a, 1999b). Comparable to self-esteem, a greater sense of mastery is also protective against depressive symptoms for African American men as they age (Mizell, 1999b; Weaver & Gary, 1993; Williams, 2003). For African American men in middle adulthood, their self-esteem and sense of mastery of their environment, compared with that during their youth, has been modified based on their lived experiences. If established earlier in life, self-esteem can be enhanced and mastery maintained for older African American men, reducing the likelihood that they will experience poor mental health (Weaver & Gary1993).

Access to Quality Health Care

For African American men, help-seeking behavior is a function of several factors, including their degree of endorsement of masculine gender-role norms (Addis & Mahalik, 2003; Brooks, 2001; Mahalik, Pierre, & Wan, 2006; Rochlen & Hoyer, 2005), African-centered norms (Parham et al., 2000), and cultural mistrust. Studies have debated the meaning and significance of African Americans’ mistrust of the health care system (Whaley, 2001). One illustration describes the association between racial discrimination and poor health as a result of the negative attitudes associated with their racial and ethnic groups (Karlsen, 2007). Another study reported that if men of African American and Caribbean descent had co-occurring mental and substance disorders, experienced an episode in the past 12 months, and had more information networks, they were more likely to use information supports and professional services (Woodard, Taylor, Bullard, & Chatters, 2011). Of the African American men who seek support, many of them rely on informal support alone, professional services alone, or no help at all (Woodard et al., 2008). A reluctance to seek help may be attributed to fear of locus of control, independence, autonomy, masculine ideologies (Addis & Mahalik, 2003; Brooks, 2001; Mahalik et al., 2003; Rochlen & Hoyer, 2005), and/or racial identity (Parham et al., 2000).

African American men may also avoid seeking mental health services due to the stigma associated with it and a belief that they will be discriminated against (Keating & Robertson, 2004). One strategy may be for mental health service providers to assess the needs of African American males at different adult life stages and tailor mental health promotion programs specifically to their needs at those stages with regard to diagnosis and treatment. Diagnosis is essential to the provision of mental health services for African American men. However, accurate diagnoses must move beyond our generalizations about all men in American culture and recognize the influence and interactions of these contextual variables in creating and defining African American men’s unique experiences. Since African American men may deny their emotional distress or attempt to conceal their illnesses, there is a need for age-specific, culturally sensitive, and gender-appropriate services that address their multifaceted needs. For example, mental health professionals who adopt a “stories over symptoms” approach to depression assessment for African American men may be more successful than those who do not. During their youth, African American men should be introduced to and utilize quality mental health services. As they enter and proceed through adulthood, African American men will need to initiate and maintain their relationships with mental health care providers, as this could result in better mental health results in the long term.

Recommendations for Addressing Depression in Adult African American Men

The purpose of this article is to conceptualize a depression framework over the adult life course that patterns the risk and protective factors that initiate, prolong, and exacerbate depression for adult African American men. This framework will be beneficial to both researchers and health professionals who work with African American men.

For Use by Researchers

Researchers may use this framework to gain an understanding of the multilevel factors that influence mental health outcomes for adult African American men. Existing evidence on the social determinants of depression for African American men challenges the next generation of researchers to consider the role of social and cultural context (Watkins et al., 2010). Future research should consider an intersectional approach to understanding African American men’s depression and overall mental health (Weber & Parra-Medina, 2003). An intersectional approach calls for simultaneously addressing the intersection of multiple aspects of socially constructed identity, including race, ethnicity, gender, class, SES, and context. Inclusion of biological, sociocultural, psychological, and environmental factors and how these factors are manifested through individual identities (e.g., racial, cultural, gender) will help develop a comprehensive understanding of depression in African American men. Future inquiries should continue to examine the impact of African American men’s lived experiences and incorporate important social and psychosocial factors that influence their lives such as SES, successful life transitions, and gender role socialization. Logical next steps include proposing other factors that lead to depression in African American men and exerting greater effort toward understanding within- and between-group differences. In terms of measurement, retrospective, prospective, and life history analysis can be used to explore African American men’s psychological resilience to risk factors and uncover more information that will inform efforts to promote their positive transitions and mental health trajectories.

Qualitative researchers may consider focusing on one period during the adult life course for African American men and exploring a social determinant such as SES or kinship using a phenomenological, grounded theory, or ethnographic approach. Depending on the approach selected, qualitative researchers may find value in using interviews, focus groups, and/or participant observation to acquire in-depth information about how a social determinant such as SES may exacerbate depression for African American men during middle adulthood, for instance. Several analyses techniques such as constant comparative analysis or content analysis could be applied to uncover the lived experiences of adult African American men with depression in order to build theory around the phenomenon. Quantitatively, such a theory could be tested using some more established measures to better understand the social determinants of depression that affect African American men over the adult life course. For example, established scales with evidence of validity and reliability, such as mastery scales (i.e., Pearlin, Lieberman, Menaghan, & Mullan, 1981), discrimination scales (i.e., Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997), and masculine norms, roles, and identity scales (i.e., Levant et al., 2007; Mahalik et al., 2003; O’Neil, 2008) could be included in surveys given to African American men in early, middle, and late adulthood. Descriptive and inferential statistics could provide details about within- and between-group differences. Future studies should also consider the acquisition of longitudinal data about the experiences of African American males. This information could help create strategies necessary for informing behavioral interventions over the adult life course and provide details on the best times during the life course for intervention.

For Use by Health Professionals

Researchers will experience greater impact if they partner with health professionals and who work with African American men, as they tend to work toward strategies for targeting mental health promotion and prevention efforts. One strategy may be for mental health service providers to include elements from the lived experiences and developmental patterns of different subgroups of African American men. For example, the life experiences of African American men with depression are frequently contextualized in disadvantaged social and economic settings (Draine et al., 2002). However, this important factor has been missing in the development and delivery of interventions and treatment of depression. Targeted interventions that focus on cognitive behavioral methods tailored to culture are a driving force in reducing the severity of depression in minority samples (Munoz et al., 1995). Similar efforts are promising for African American men across different adult life stages. For example, targeted interventions for African American men in middle adulthood could focus on prevention and intervention efforts that address racism at the workplace. This information could be delivered through a variety of mediums. For example, a brochure on workplace stress and unfair treatment could be available in the waiting rooms of doctors’ offices and other health care facilities that service African American men. In addition, the age and social and economic situations of African American men could prompt their health care professionals to initiate discussions around some of the social determinants presented in the framework. In other words, if members of an African American man’s health care team were knowledgeable about the ways in which depression are conceptualized over the adult life course for African American men, they could use the framework to initiate a conversation about mental health with them.

There is a need for a focus on prevention at early adult life stages and intervention at all adult developmental stages for African American males. If early prevention and successful intervention efforts to improving and maintaining the mental health and well-being of African American males are implemented, threatening social determinants could potentially have less of an impact on their mental health over the adult life course. Empirical examinations of the buffering effects of potentially damaging factors are needed and could be highly informative to health professionals working with African American men. One strategy may be for mental health service providers to assess the needs of African American males at different life stages and tailor mental health promotion and disorder prevention programs specifically to these needs. Again, the conceptual framework presented here should stimulate discussion around which social determinants are most deleterious for African American men and at which stages of adult development do these effects initiate, prolong, and exacerbate depression.

Health professionals who consider the social construction of manhood and masculinities empower African American men to care for their health (Rich, 2000; Watkins et al., 2010). Such practices may be more effective than those that focus on just enhancing self-esteem. Cochran and Rabinowitz (2003) outlined masculine-specific assessment approaches to detecting depression in men that integrate the idiosyncratic manner in which many men cope with depressed mood with traditional diagnostic criteria for depression used by most health professionals. Some health professionals have suggested that men might feel more amenable toward help seeking if they are offered treatment focused on thinking rather than on feeling. Although men’s emotional expressions are assumed to create a barrier between them and help-seeking behaviors, a study by Cusack, Deane, Wilson, and Ciarrochi (2006) found that once in therapy, bond and perceptions of treatment helpfulness are more important to future help-seeking intentions than a man’s difficulty with emotional expression. Self-directed techniques that focus on problem-solving skills rather than analyzing vulnerable feelings and changing the description of services may be appropriate for African American men over the adult life course. Yet as African Americans tend to conceal emotional health status (Baker, 2001), researchers have reported positive associations between self-concealment and indications of compromised mental health, such as depression, poor self-esteem, and lower levels of perceived social support (Cramer & Barry, 1999). Therefore, it is important for health professionals to consider the challenges associated with obtaining trust and establishing open communication with African American male patients.

Though this framework presents an initial inquiry about the social determinants that influence depression in adult African American men, it should be considered in the context of its limitations. First, this framework presents only six social determinants of depression in African American men. There are certainly more that exist; however, this article serves as an initial discussion around the risk and protective factors that influence depression over the adult life course for African American men. Next, though portions of the proposed framework have been examined by a number of studies (Hammond & Mattis, 2005; Lincoln et al., 2011; Mizell, 1999a, 1999b; Watkins et al., 2010; Watkins et al., 2011; Williams, 2003; Woodward et al., 2011), it has not been tested in its entirety. Therefore, recommendations provided here are merely exploratory and should be developed further. Some constructs of this framework may be easier to implement in behavioral interventions with African American men whereas others may be easier to test in empirical studies. For example, there is still not clear understanding about what masculine identity means to African American men and how health professionals can implement treatment strategies to help achieve African American men’s mental health goals. Finally, there are no clear guidelines for where each age-linked adult life stage should begin and end. Therefore, this framework loosely considers how these six social determinants may influence depression for African American men at different points in the adult life course, understanding that some determinants will influence a man’s life course transitions and trajectories differently than others.

Conclusion

This article presents an operational framework for examining six social determinants of depression (i.e., SES, stressors, racial and masculine identity, kinship and social support, self-esteem and mastery, and quality health care) for African American men over the adult life course. As African American men transition to and through adulthood, it is important to note the gender-specific and culturally specific experiences that they will endure, compared with men and women of other racial and ethnic groups. To date, research on within-group differences among African American men has been sparse. Even fewer studies have examined age-linked life stage differences with regard to depression for African American men. This limited scholarship has presented challenges for the researchers who study the mental health of African American men and the health professionals who treat them. Though not conclusive, the framework proposed here should stimulate future inquires about depression over the adult life course for African American men. In an effort to extend the work of previous scholars, this framework patterns the risk and protective factors that initiate, prolong, and exacerbate depression for African American men. Yet it leaves room for modifications. Next, steps should include building on the proposed framework by adding additional social determinants to understand within- and between-group differences. Furthermore, developing strategies to improve African American men’s psychological resilience to risk factors and focusing on methods to promote their successful transitions and mental health trajectories should be at the forefront of future inquiries.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge S. Olivia Jefferson and Mee-Young Um for assistance in preparing this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abreu JM, Goodyear RK, Campos A, Newcomb MD. Ethnic belonging and traditional masculinity ideology among African Americans, European Americans, and Latinos. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2000;1:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the context of help seeking. American Psychologist. 2003;58:5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EA, Kohler JK, Letiecq BL. Predictors of depression among low-income, nonresidential fathers. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26:547–567. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J, Taber S. Adolescence terminable and interminable: When does adolescence end? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1994;23:517–537. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson RE, Whitehead TL, Baber WL. Challenges to masculine transformation among urban low-income African American males. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:732–741. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker FM. Diagnosing depression in African Americans. Community Mental Health Journal. 2001;37(1):31–38. doi: 10.1023/a:1026540321366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life-course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: Conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31:285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentelspacher CE. Life course development of African American men: A social-psychological analysis. 2008 Abstract retrieved from http://i08.cgpublisher.com/proposals/229/index_html.

- Blane D, Higgs P, Hyde M, Wiggins RD. Life course influences on quality of life in older age. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58:2171–2179. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonczar TP. Prevalence of imprisonment in the US population 1974-2001 (Special Report, NCJ 197976) Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bonhomme JJE. The health status of African-American men: Improving our understanding of men’s health challenges. Journal of Men’s Health & Gender. 2004;1(2-3):142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman PJ. Research perspectives on black men: Role strain and adaptation across the adult life cycle. In: Jones RL, editor. Black adult development and aging. Berkeley, CA: Cobb & Henry; 1989. pp. 117–150. [Google Scholar]

- Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC. The MIDUS National Survey: An overview. In: Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC, editors. How healthy are we? A national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks G. Masculinity and men’s mental health. Journal of American College Health. 2001;49(6):285–297. doi: 10.1080/07448480109596315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR, Keith VM. The epidemiology of mental disorders and mental health among African American women. In: Brown DR, Keith VM, editors. In and out of our right minds: The mental health of African American women. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2003. pp. 23–58. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P, Wheaton B. Mapping social context on mental health trajectories through adulthood. In The structure of the life course: Standardized? Individualized? Differentiated? Advances in Life Course Research. 2005;9:269–301. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SV, Rabinowitz FE. Gender-sensitive recommendations for assessment and treatment of depression in men. Professional Psychology. 2003;34:132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay WH. Counseling men in medical settings. In: Brooks GR, Good GE, editors. The new handbook of psychotherapy and counseling with men: A comprehensive guide to settings, problems, and treatment approaches. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2001. pp. 59–91. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer KM, Barry JE. Conceptualizations and measures of loneliness: A comparison of subscales. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;27:491–502. [Google Scholar]

- Cusack J, Deane FP, Wilson CJ, Ciarrochi J. Emotional expression, perceptions of therapy, and help-seeking intentions in men attending therapy services. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2006;7(2):69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ditton P. Mental health and treatment for inmates and probationers. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Draine J, Salzer MS, Culhane DP, Hadley TR. Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:565–573. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erguner-Tekinapl B. Daily experiences of racism and forgiving historical offenses: An African American experience. International Journal of Human and Social Sciences. 2009;4(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Franchina JJ, Eisler RM, Moore TM. Masculine gender role stress and intimate abuse: Effects of masculine gender relevance of dating situations and female threat on men’s attributions and affective responses. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2001;2(1):34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin CW. Conceptual and logical issues in theory and research related to Black masculinity. Western Journal of Black Studies. 1986;10(4):161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin CW, II, Mizell CA. Some factors influencing success among African-American men: A preliminary study. Journal of Men’s Studies. 1995;3:191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Gadsden V, Trent W, editors. Transitions in the life course of African-American males: Issues in schooling, adulthood, fatherhood, and families. Philadelphia, PA: National Center on Fathers and Families; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gaines JS. Social correlates of psychological distress among adult African American males. Journal of Black Studies. 2007;37:827–858. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin ST. Successful African-American men: From childhood to adulthood. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Halfon N, Hochstein M. Life course health development: An integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. Milbank Quarterly. 2002;80:433–479. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond W, Mattis JS. Being a man about it: Constructions of masculinity among African American men. Men and Masculinities. 2005;6:114–126. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P, Karberg J. Prison and jail inmates at mid-year 2003 (NCJ 203947) Washington, DC: U.S Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hattery AJ, Smith E. African American families: Issues of health, wealth, and violence. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Howard-Hamilton M. Theory to practice: Applying developmental theories relevant to African-American men. New Directions for Student Services. 1997;80:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter AG, Friend CF, Murphy SY, Rollins A, Williams-Wheeler M, Laughinghouse J. Loss, survival, and redemption: African American male youth’s reflections on life without fathers, manhood, and coming of age. Youth & Society. 2006;37:423–452. [Google Scholar]

- James A, Tucker B, Mitchell-Kernan C. Martial attitudes, perceived mate availability, and subjective well-being among partnered African American men and women. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Joe S, Baser RE, Breeden G, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts among Blacks in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296:2112–2123. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen S. Ethnic inequalities in health: The impact of racism (Better Health Briefing 3) London, England: Race Equality Foundation; 2007. Retrieved from http://www.better-health.org.uk/files/health/health-brief3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Keating F. African and Caribbean men and mental health. Ethnicity and Equalities in Health and Social Care. 2009;2(2):41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Keating F, Robertson D. Fear, Black people and mental illness: A vicious circle? Health and Social Care in the Community. 2004;12:439–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick L, Anderson NL, Moore B. Perceptions of depression among young African American men. Family & Community Health. 2007;30(1):63–73. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200701000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Wang PS, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle K, Zhao S, Nelson C, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Kendler K, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Power C, Blane D, Bartley M. Socioeconomic pathways between childhood and adult health. In: Kuh DL, Ben-Shlomo Y, editors. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: Tracing the origins of ill health from early to adult life. 2. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 371–395. [Google Scholar]

- Levant RF, Smalley KB, Aupont M, House A, Richmond K, Noronha D. Initial validation of the Male Role Norms Inventory–Revised. Journal of Men’s Studies. 2007;15:85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson DJ. A theory of life structure development in adulthood. In: Alexander CN, Langer J, editors. Higher stages of human development: Perspectives on adult growth. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1990. pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Watkins DC, Chatters L. Correlates of psychological distress and major depressive disorder among African American men. Research on Social Work Practice. 2011;21:278–288. doi: 10.1177/1049731510386122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littrell J, Beck E. Predictors of depression in a sample of African-American homeless men: Identifying effective coping strategies given varying levels of daily stressors. Community Mental Health Journal. 2001;37:15–29. doi: 10.1023/a:1026588204527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love AS, Love RJ. Measurement suitability of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale among older urban Black men. International Journal of Men’s Health. 2006;5:173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Mac An Ghaill M. The making of men: Masculinities, sexualities and schooling. Buckingham, England: Open University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Good GE, Englar-Carlson M. Masculinity scripts, presenting concerns, and help seeking: Implications for practice and training. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2003;34:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Locke BD, Ludlow LH, Diemer MA, Scott RPJ, Gottfried M, Freitas G. Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2003;4(1):3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Pierre MR, Wan SC. Examining racial identity and masculinity as correlates of self-esteem and psychological distress in black men. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 2006;34:94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Majors R, Billson J. Cool pose: The dilemmas of Black manhood in America. New York, NY: Lexington Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mankowski ES, Manton KI. A community psychology of men and masculinity: Historical and conceptual review. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;45:73–86. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9288-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizell AC. Life course influences on AfricanAmericanmen’s depression: Adolescent parental composition, self-concept, and adult earnings. Journal of Black Studies. 1999a;29:467–490. [Google Scholar]

- Mizell AC. African American men’s personal sense of mastery: The consequences of the adolescent environment, self-concept, and adult achievement. Journal of Black Psychology. 1999b;25:210–230. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz RF, Ying YW, Bernal G, Perez-Stable EJ, Sorensen JL, Hargreaves WA, Miller LS, et al. Prevention of depression with primary care patients: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:199–222. doi: 10.1007/BF02506936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nghe LT, Mahalik JR. Examining racial identity statuses as predictors of psychological defenses in African American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2001;48:10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Okech AP, Harrington R. The relationships among Black consciousness, self-esteem, and academic self-efficacy in African American men. Journal of Psychology. 2002;136:214–224. doi: 10.1080/00223980209604151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver W. “The streets”: An alternative Black male socialization institution. Journal of Black Studies. 2006;36:918–937. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil J. Summarizing 25 years of research on men’s gender role conflict using the Gender Role Conflict Scale: New research paradigms and clinical implications. The Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36:358–445. [Google Scholar]

- Parham TA, White JL, Ajamu A. The psychology of Blacks: An African centered perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Paxton K, Robinson WL, Shah S, Schoeny M. Psychological distress for African-American adolescent males: Exposure to community violence and social support as factors. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2004;34:281–295. doi: 10.1023/B:CHUD.0000020680.67029.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne YA. A gangster and a gentleman: How street life-oriented, U.S.-born African men negotiate issues of survival in relation to their masculinity. Men and Masculinities. 2006;8:288–297. [Google Scholar]

- Payne YA. Site of resilience: A reconceptualization of resiliency and resilience in street life-oriented Black men. Journal of Black Psychology. 2011;37(4):426–451. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, Mullan JT. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson DF. The Black man: Health issues and implications for clinical practice. Journal Black Studies. 1994;25:81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit B, Western B. Mass imprisonment and the life course: Race and class inequality in U.S. incarceration. American Sociological Review. 2004;69:151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DA. Masculinity, male development, gender, and identity: Modern and postmodern meanings. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2006;27:403–423. doi: 10.1080/01612840600569666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre MR, Mahalik JR. Examining African self-consciousness and Black racial identity as predictors Black men’s psychological well-being. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2005;11(1):28–40. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]