Abstract

Blood pressure (BP) is a heritable risk factor for cardiovascular disease. To investigate genetic associations with systolic BP (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and pulse pressure (PP), we genotyped ∼50,000 SNPs in up to 87,736 individuals of European ancestry and combined these in a meta-analysis. We replicated findings in an independent set of 68,368 individuals of European ancestry. Our analyses identified 11 previously undescribed associations in independent loci containing 31 genes including PDE1A, HLA-DQB1, CDK6, PRKAG2, VCL, H19, NUCB2, RELA, HOXC@ complex, FBN1, and NFAT5 at the Bonferroni-corrected array-wide significance threshold (p < 6 × 10−7) and confirmed 27 previously reported associations. Bioinformatic analysis of the 11 loci provided support for a putative role in hypertension of several genes, such as CDK6 and NUCB2. Analysis of potential pharmacological targets in databases of small molecules showed that ten of the genes are predicted to be a target for small molecules. In summary, we identified previously unknown loci associated with BP. Our findings extend our understanding of genes involved in BP regulation, which may provide new targets for therapeutic intervention or drug response stratification.

Introduction

Blood pressure (BP) is a major, modifiable determinant of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk.1 Hypertension (MIM 145500) increases risk for a variety of sequelae, including coronary artery disease, heart failure (MIM 608320), stroke (MIM 601367), and peripheral vascular disease (MIM 606787).2 Heritability of daytime ambulatory BP from twin studies has been estimated to be approximately 50%–60%3,4 and ∼40% in family studies. Several studies have been performed to elucidate underlying genetic factors for BP, including genome-wide association studies (GWASs), meta-analyses, and admixture mapping.5–12 Efforts to dissect the genetic basis for this complex disorder have proven challenging and currently only a small portion of the total variation in BP can be explained by common genetic variants associated signals. Part of this “missing heritability” is likely to be due to as yet unknown common or low-frequency variants, and a fraction of it could be identified by increasing sample size. Increased understanding of the underlying genetics may contribute to improvement of the treatment to reduce CVD risk.

We conducted an association analysis of BP phenotypes in 87,736 individuals of European ancestry by using a gene-centric array with ∼50,000 SNPs capturing variation in ∼2,100 genes related to CVD, and we replicate our findings in 68,368 independent individuals. We also performed extensive bioinformatics analyses to identify regulatory regions by using the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE), eQTL studies, and pathway analyses. Finally, all previously reported BP-associated loci and the genes within were annotated for their suitability as drug targets.

Material and Methods

Population Characteristics

Phenotype and genotype data from 87,736 individuals of European ancestry from 36 participating studies were used for the discovery phase, and an additional 68,368 individuals of European ancestry, from 19 additional studies, were used in the replication phase. All individuals in these studies provided informed consent, and each study was approved by its own local ethics committee. Descriptions of the participating cohorts are provided in the original publications.5,8,11,13

Phenotypes

Pulse pressure (PP) was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) minus diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and median arterial pressure (MAP) was defined as 2/3 DBP plus 1/3 SBP. Each cohort provided regression models for its respective data, adjusted for age, age-squared, body mass index (BMI), and any study-specific corrections for population substructure (based on principal components analysis). BP values were adjusted for antihypertensive drug therapy by adding a standard treatment adjustment of 15 mmHg to the SBP and 10 mmHg to the DBP values of individuals receiving treatment in the discovery and replication cohorts. These adjustments were implemented prior to the calculation of MAP and PP.

Genotyping

A total of 52,029 SNPs were included in the meta-analyses, and all SNPs were present in at least one of the three iterative versions of the Illumina HumanCVD BeadChip (also known as the “Cardiochip” or the ITMAT-Broad-CARe [IBC] array manufactured by Illumina)14 used by all discovery cohorts. Several studies that used this array have already been published for a variety of phenotypes and disease outcomes, including coronary artery disease,16,17 plasma lipids,18 BP,8,11,15 heart failure,19 type 2 diabetes (T2D [MIM 125853]),20 and BMI (MIM 606641).21

Quality Control, Association, and Meta Analyses

The discovery data sets derive from three BP consortia with completely independent samples whose results have been published separately: the IBC BP consortium8 and the CVD-50 consortium,22 with the addition of the Beaver Dam Studies (BOSS, EHLS, BDES) consortium.13 The QC steps taken for SNPs and samples were similar for both consortia, namely: individuals with <90% call rate (completeness) across all SNPs were removed, as well as SNPs with <95% call rate (completeness) or SNPs causing heterozygous haploid genotype calls across all remaining individuals. SNPs were also removed if they were not in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p < 1 × 10−7). No study included imputed data in their analyses. Further details on genotyping and QC can be found in the original publications including the BOSS, EHLS, and BDES studies.8,11,13

During the meta-analysis step, SNPs with frequencies incompatible with HapMap CEU frequencies were removed (defined as >30% difference in the minor allele frequencies) for each data source separately, i.e., the meta-analysis results of IBC BP, of CVD-50, and of BOSS, EHLS, and BDES. We used inverse variance weighted meta-analysis in MANTEL23 to obtain a fixed-effect estimate and statistical significance for each SNP. We applied genomic control24 to each data set to control effects possibly resulting from population stratification or cryptic relatedness. The CARe IBC array studies, included in this meta-analysis, determined that after accounting for linkage disequilibrium (LD), the effective number of independent tests was ∼20,500 for Europeans. This resulted in an experimental or “arraywide” statistical threshold of p = 2.4 × 10−6 to maintain a false-positive rate of 5%25 and therefore we have adopted this threshold for this study. For each associated locus, the LD patterns were examined and independence between the loci identified in this study and previously published signals was verified with SNAP26 (r2 < 0.3).

Replication analysis was conducted in independent samples for each trait, for SNPs with association p < 1 × 10−5 in the discovery analysis, with a total of 68,368 individuals from the Global Blood Pressure Genetics (GBPG) consortium,10 Women’s Genome Health Study (WGHS),27 and PREVEND28 and LifeLines29 studies. We combined discovery and replication data in a meta-analysis and accounted for testing four phenotypes (albeit highly correlated), resulting in a Bonferroni-corrected threshold of p < 6 × 10−7 for the combined meta-analysis of discovery and replication samples.

Definition of Associated Gene Variants and Variant Functional Analysis

The extended locus around each associated SNP was defined by identification of all SNPs showing r2 ≥ 0.5. Linkage disequilibrium was defined with the HaploReg tool30 based on Phase I of the 1000 Genomes project. Variants showing evidence of LD with associated variants were explored for impact on gene function via Annovar31 and regulatory function (including eQTLs) by HaploReg30 and RegulomeDB,32 which both collate data from the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE)33 and nine eQTL studies.32 Associated genes were reviewed for evidence linking them to BP-related phenotypes via PubMed and “hypertension,” “cardiovascular disease,” or “vascular disease” as medical subject headings (MeSH) terms. MeSH is a controlled vocabulary created by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) to index journal articles and books in the life sciences. All articles in MEDLINE have been annotated with MeSH by NLM curators or designees, offering a sensitive measure of correlation between biological traits and genes in the literature.34 We also checked for annotation to the gene ontology term “regulation of blood pressure,” which also represents a highly curated set of genes consistently linked to blood pressure.35 At a pathway level, we used GeneGo Metacore (Thomson Reuters) to construct a custom BP network based on 436 genes annotated to the “hypertension” MeSH term and gene ontology terms described above. The Metacore database is a large commercial database of curated human, rat, and mouse gene and protein interactions individually evidenced in the literature.36 This allowed us to construct a core network of interacting genes that are each individually linked to blood pressure, which collectively are likely to represent a significant blood pressure gene network. We used this network as a tool to investigate direct interactions between the blood pressure gene network and the genes in the blood pressure loci reported here. By combining network data with data on gene and variant function, we were able to prioritize genes based on their level of support with respect to BP phenotypes.

Analysis of Pharmacologic Targets

We annotated genes containing variants in LD (HapMap CEU r2 > 0.5) with discovered associations and analyzed information concerning potential druggability—that is, the potential for modulation of the protein target by a water-soluble small-molecule drug. Druggable proteins usually contain a defined binding pocket or active site, which could act as a site of action (pharmacophore) for an orally bioavailable small-molecule drug. We grouped proteins into four druggability classes, based on complementary annotations of the potentially druggable genome and publicly available databases of small molecules. Targets in class 1 are already drugged with a marketed drug recorded in DrugBank; class 2 have small molecules recorded in ChEMBL, which may include compounds in current development within pharmaceutical companies, and could be used as tools in animal and cellular models; class 3 are homologous to class 1 or class 2 targets; and class 4 are predicted to contain a potentially druggable pharmacophore based on de novo structure-based druggability prediction via the online available DoGSiteScorer tool,37 which binds site prediction, analysis, and druggability.

Expression Quantitative Trait Loci Analysis

We identified alias identifiers for significant index SNPs by using SNAP, an online tool for LD calculations.26 Further proxy SNPs displaying high LD (r2 > 0.8) were identified across four HapMap builds in European ancestry samples (CEU) with SNAP. The primary SNPs and LD proxies were searched against a collated database of expression SNP (eSNP) results including the following tissues: fresh lymphocytes,38 fresh leukocytes,39 leukocyte samples in individuals with celiac disease (MIM 212750),24 whole blood samples,40–43 lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) derived from asthmatic children (MIM 600807),44,45 HapMap LCLs from three populations,46 a separate study on HapMap CEU LCLs,47 additional LCL population samples,48–51 CD19+ B cells,52 primary PHA-stimulated T cells,48 CD4+ T cells,53 peripheral blood monocytes,52,54,55 CD11+ dendritic cells before and after Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (MIM 607948),56 omental and subcutaneous adipose,40,50,57 stomach,57 endometrial carcinomas (MIM 608089),58 ER+ and ER− breast cancer tumor cells (MIM 114480),59 brain cortex,54,60,61 prefrontal cortex,62,63 frontal cortex,64 temporal cortex,61,64 pons,64 cerebellum,61,64 three additional large studies of brain regions including prefrontal cortex, visual cortex, and cerebellum,65 liver,57,66,67 osteoblasts,68 ileum,57,69 lung,70 skin,50,71 and primary fibroblasts.48 MicroRNA QTLs were also queried for LCLs72 and gluteal and abdominal adipose.73 The collected eSNP results met the criteria for association with gene expression levels as defined in the original papers. The majority of eQTLs (15/17) showed a p value of 1 × 10−6 or less. Two replication studies with more modest association were also included. We placed more value on eQTLs with low p values that showed consistent reporting across independent studies. In each case where a SNP or proxy was associated with transcript levels, we further examined the strongest eSNP for that transcript within that data set (best eSNP) and the LD between the best eSNP and BP-selected eSNPs to estimate the concordance of the BP and expression signals.

Results

Discovery Meta-analysis

In the discovery meta-analysis, four BP traits were analyzed in 87,736 individuals from 36 cohorts, as described in Table S1 available online. We analyzed SBP, DBP, MAP, and PP as continuous traits. Cohort characteristics, including age, sex, BP values, and the proportion of individuals treated with BP-lowering medications, are provided in Table S1.

Association analyses were successfully carried out for up to 48,616 SNPs that passed QC. We identified 17 SNPs that passed a suggestive discovery p value threshold of p < 1 × 10−5 with six SNPs showing strongest associations with SBP, i.e., lowest p value among all four traits (and one secondary association, i.e., a threshold-passing p value but with a higher p value than in another trait), two SNPs showing strongest associations with DBP (and two other secondary associations), two showing strongest associations with MAP (and two other secondary ones), and three leading associations to PP (with three secondary associations).

Replication Analyses

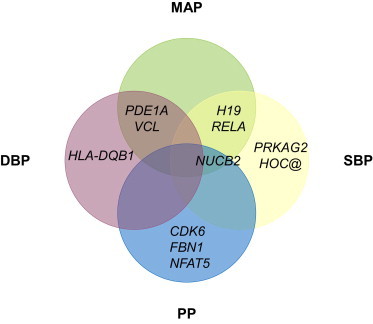

Replication testing was performed in 68,368 additional individuals from 19 cohorts with genome-wide SNP genotypes imputed to HapMap, only to the signals passing the threshold on discovery and previously not published. A meta-analysis of the 17 SNPs taken forward from the discovery phase with replication data showed that 11 SNPs at independent loci met our Bonferroni-corrected array-wide significance threshold of p < 6 × 10−7. Some of these SNPs showed association with more than one trait, which resulted in 17 previously not described associations: three loci were associated with DBP (PDE1A [MIM 171890], HLA-DQB1 [MIM 604305], and VCL [MIM 193065]), five loci were associated with SBP (PRKAG2 [MIM 602743], H19 [MIM 103280], NUCB2 [MIM 608020], SIPA1 [MIM 602180], and HOXC complex [MIM 142974]), five loci were associated with MAP (PDE1A, VCL, H19, NUCB2, and RELA [MIM 164014]), and four loci were associated with PP (CDK6 [MIM 603368], NUCB2, FBN1 [MIM 134797], and NFAT5 [MIM 604708]) (Figure 1). The association results are summarized in Table 1. We also found a suggestive association in ERAP1 (MIM 606832) with 2.4 × 10−6 > p > 6 × 10−7, which reached array-wide significance but not Bonferroni-corrected significance (array-wide significance divided by the number of traits, four).

Figure 1.

Overview of the Replicated Blood-Pressure-Related Findings from This Meta-analysis for Overlap with the Various Blood-Pressure-Related Traits

Abbreviations are as follows: SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; and PP, pulse pressure.

Table 1.

Significant Association Results for All Four Traits in the Meta-analysis

| Locus | SNP | CHR | Pos | Effect Allele |

Discovery p Values |

Replication p Values |

Combined Discovery + Replication |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 87,736) | (n = 68,368) | beta | SE | p Val | |||||

| DBP | |||||||||

| PDE1A | rs16823124 | 2 | 182932372 | A | 1.76 × 10−6 | 2.59 × 10−5 | 0.262 | 0.041 | 1.95 × 10−10 |

| HLA-DQB1 | rs2854275 | 6 | 32736406 | A | 2.97 × 10−8 | 1.86 × 10−4 | −0.562 | 0.101 | 5.53 × 10−12 |

| VCL | rs4746172 | 10 | 75525848 | C | 2.14 × 10−5 | 1.07 × 10−3 | 0.230 | 0.043 | 9.14 × 10−8 |

| MAP | |||||||||

| PDE1A | rs16823124 | 2 | 182932372 | A | 1.10 × 10−4 | 3.85 × 10−4 | 0.269 | 0.052 | 1.90 × 10−7 |

| VCL | rs4746172 | 10 | 75525848 | C | 7.91 × 10−6 | 8.73 × 10−3 | 0.279 | 0.054 | 2.45 × 10−7 |

| H19 | rs217727 | 11 | 1973484 | A | 1.63 × 10−5 | 3.94 × 10−3 | 0.315 | 0.061 | 2.15 × 10−7 |

| NUCB2 | rs757081 | 11 | 17308259 | G | 3.23 × 10−5 | 1.16 × 10−3 | 0.265 | 0.050 | 1.39 × 10−7 |

| RELA | rs3741378 | 11 | 65165513 | T | 3.08 × 10−5 | 2.30 × 10−3 | −0.359 | 0.070 | 2.44 × 10−7 |

| PP | |||||||||

| CDK6 | rs2282978 | 7 | 92102346 | C | 3.82 × 10−8 | 0.073 | −0.268 | 0.049 | 4.51 × 10−8 |

| NUCB2 | rs757081 | 11 | 17308259 | G | 4.51 × 10−7 | 4.48 × 10−5 | 0.321 | 0.050 | 8.94 × 10−11 |

| FBN1 | rs1036477 | 15 | 46702218 | G | 6.59 × 10−6 | 8.02 × 10−3 | −0.402 | 0.077 | 2.00 × 10−7 |

| NFAT5 | rs33063 | 16 | 68197718 | A | 9.07 × 10−7 | 0.063 | 0.335 | 0.066 | 4.14 × 10−7 |

| SBP | |||||||||

| PRKAG2 | rs10224002 | 7 | 151045974 | G | 1.67 × 10−6 | 0.023 | 0.361 | 0.072 | 5.50 × 10−7 |

| H19 | rs217727 | 11 | 1973484 | A | 7.88 × 10−6 | 2.95 × 10−3 | 0.417 | 0.078 | 1.03 × 10−7 |

| NUCB2 | rs757081 | 11 | 17308259 | G | 2.26 × 10−7 | 1.28 × 10−4 | 0.403 | 0.063 | 1.65 × 10−10 |

| RELA | rs3741378 | 11 | 65165513 | T | 1.70 × 10−6 | 4.42 × 10−5 | −0.546 | 0.087 | 3.41 × 10−10 |

| HOXC@ | rs7297416 | 12 | 52729357 | C | 2.26 × 10−6 | 0.011 | −0.334 | 0.065 | 2.32 × 10−7 |

We compared the results of our analysis with all published associations at the time of this report (to the best of our knowledge)5,8–11,22,74–77 and confirmed previously reported BP associations at 27 loci with same direction of effect (at a nominal association threshold [p < 0.05]), out of 32 loci covered by this genotyping array, with partial sample overlap between original findings and our study (Table S2 contains all previously reported loci and our p values for these associations; each column with an X indicates a significant result was found by the referred study to the specified trait). We did not find supportive evidence of association with BP of five loci: CACNB2 (MIM 600003), CDH13 (MIM 601364), C10orf107 (MIM not available), ZNF652 (MIM 613907), and STK39 (MIM 607648), which were found in GWAS meta-analyses. The IBC array does not contain lead SNPs or proxies for 18 of the previously reported loci identified by GWASs.

eQTLs

Several of the reported loci have significant eQTLs. rs2854275 is associated with the expression of HLA-DRB4 in monocytes (p = 4.82 × 10−95) and in liver (p = 1.31 × 10−10) and HLA-DRB1 (MIM 142857) in blood (p = 3.20 × 10−59); rs2282978 associates with CDK6 expression (MIM 603368) (p = 2.6 × 10−5); rs4746172 is in perfect LD with rs10824069, which presents a significant association with expression of the ADK transcript (MIM 102750) in lung (p < 2 × 10−16); and rs217727 is associated with increased expression of AK126915 in LCLs (p = 2.40 × 10−6) and skin (p = 6.59 × 10−6). Closer investigation of the AK126915 transcript in the UCSC Genome Browser suggests that it may represent an isoform of the mitochondrial ribosomal protein L23 (MRPL23 [MIM 600789]) (data not shown). rs757081 is associated with expression of NUCB2 (MIM 608020) in LCLs in asthmatics (p = 1.56 × 10−16) and of SNORD14A in LCLs (p = 3.10 × 10−5); rs33063 is associated with expression of another unknown transcript, LOC283970 in B cells (p = 9.55 × 10−8); and rs3741378 is in tight LD with several SNPs that present significant eQTL levels in lymph, liver, and other tissues. Table S4 presents the results in more detail.

Extended Locus Analysis and Variant Functional Analysis

Variants in LD (r2 > 0.5) with the 11 replicated SNPs are functionally annotated in Table S5, and a nonredundant list of corresponding genes appear in Table S6. Several loci contained only one gene (PDE1A, HLA-DQB1, CDK6, PRKAG2, and FBN1), whereas others contained several genes (see Table S6). By comprehensive functional annotation, we reviewed the genes at each locus both for evidence of functional impact (genic and regulatory) and a rationale in BP.

Discussion

In this study we identified 11 loci associated with BP traits (p < 6 × 10−7) in a meta-analysis comprising 87,736 individuals of European descent. These associations were validated in a replication cohort of 68,368 individuals. The robust sample size also confirmed a nominal association (p < 0.05) of 27 previously reported signals, out of the 32 previously reported loci covered by this array.

Associated Loci with a Single Candidate Gene

Of the 11 loci described in this study, 5 contain only a single gene. The PDE1A locus contains the phosphodiesterase 1A (PDE1A) gene, a Ca2+/calmodulin-stimulated phosphodiesterase that preferentially hydrolyzes cGMP and has an important role in regulating vascular tone and smooth muscle cell proliferation.78,79 The HLA-DQB1 locus contains HLA-DQB1 (major histocompatibility complex, class II, DQ beta 1), which encodes a class II molecule expressed in antigen-presenting cells and plays a role in the immune system by presenting peptides derived from extracellular proteins. HLA-DQB1 alleles have been linked to essential hypertension in Chinese populations.80 At the PRKAG2 locus, PRKAG2 (protein kinase, AMP-activated, gamma 2 noncatalytic subunit) is important in cellular metabolism and has been associated with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (MIM 194200), urate levels and chronic kidney disease,81,82 and accumulation of cardiac glycogen and left ventricular hypertrophy resembling hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.83,84 Chronic kidney disease and left ventricular hypertrophy represent target organ damage related to hypertension, and thus, our findings may provide a link between genetic loci affecting BP and the occurrence of clinically important sequelae. Other traits associated with PRKAG2 include hemoglobin85 and hematocrits.86 The FBN1 locus encodes fibrillin-1 (FBN1), a component of elastic fibers in connective tissue, and this gene has been associated with Marfan syndrome (MIM 154700), with systolic and pulse pressure, with aortic stiffness in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD),87,88 and with thoracic aortic aneurysms and thoracic aortic dissection.89 CDK6 variants are associated with height (MIM 606255) in a number of studies90–92 and are implicated in white blood cell counts in Japanese populations93,94 and in African Americans.95

Associated Loci with Multiple Genes

The remaining loci (VCL, H19, NUCB2, SIPA1, HOXC4, and NFAT5) contain several genes that we have prioritized on the basis of variant functionality and the biological rationale of the genes in the BP phenotypes.

We consider vinculin (VCL) the strongest biological candidate. Vinculin is a cytoskeletal protein, localized to intercalated discs, and by anchoring thin filaments it is implicated in cardiac force generation. Targeted disruption of vinculin in mice has shown loss of cardiac contractility in embryonic development.96 The two other candidates at the VCL locus (AP3M1 and ADK) show moderate evidence of functional variation.

The H19 locus contains three genes. H19 (H19, imprinted maternally expressed transcript [nonprotein coding]) expresses a noncoding RNA. Methylation defects in this gene have been associated with pre-eclampsia in a study with 188 pregnancies97 and imprinting syndromes such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (MIM 130650) and growth retardation disorder Silver-Russell syndrome (MIM 180860).98,99 The locus also contains the mitochondrial ribosomal protein L23 (MRPL23) and an antisense transcript MRPL23-AS1. There are no data suggesting a putative role in BP for the latter, but eQTL analysis identified a putative isoform of MRPL23 (AK126915).

The NUCB2 locus contains four genes: PIK3C2A, NUCB2, NCR3LG1, and KCNJ11. The product of NUCB2, nucleobindin 2, induces hypertension when intracerebrally administered.100 It is also involved in the maintenance of calcium blood levels, feeding behavior, water intake, glucose homeostasis, and the release of tumor necrosis factor from vascular endothelial cells by interacting with ERAP1.101,102 It has been also associated with height in GWASs.90–92 The potassium inwardly rectifying channel, encoded by KCNJ11, is also a good biological candidate, which has been reported to be associated with hypertension103 as well as type 2 diabetes, although the previously reported variants are not in LD with the association reported in this study.

The SIPA1 locus contains seven genes: MAP3K11, PCNXL3, SIPA1, RELA, KAT5, RNASEH2C, and AP5B1. SIPA1 (signal-induced proliferation-associated 1) is the strongest functional candidate, and the associated SNP encodes a nonsynonymous p.Ser182Phe polymorphism, which is predicted to be deleterious by several bioinformatics tools.31 The strongest biological candidate is the adjacent RELA (a.k.a. NF-κB3), which forms part of the NF-κB protein complex and has been shown to modulate angiotensin II-induced hypertension in the paraventricular nucleus.104

The HOXC4 locus contains three homeobox genes: HOXC4, HOXC5, and HOXC6. All three genes are closely related and encode transcription factors involved in morphogenesis. A recent trans-ethnic GWAS on blood pressure found a signal related to HOXCA,105 suggesting that homeoboxes may have an association with blood pressure in more ethnicities.

The NFAT5 locus also contains several candidates, including NFAT5 (Nuclear factor of activated T cells 5). NFAT5 is a transcription factor, recently shown to regulate vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) modulation.106 In vivo studies in NFAT5+/−ApoE−/− mice indicated that NFAT5 is directly involved in atherosclerotic lesion formation and identified NFAT5 as a positive regulator of atherosclerotic lesion formation.107 A variant at this locus has also been associated with serum urate81 and age at menarche.108 Small-molecule activators of the adjacent NQO1 (NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase) have been shown to ameliorate spontaneous hypertension in animal models via modulation of eNOS activity.109 The Ubiquitin-protein ligase WWP2 is also a candidate, because it is known to bind and downregulate the epithelial Na(+) channel (ENaC). Mutations in WWP2 have been shown to result in hypertension.110

Therapeutic Opportunities

Current antihypertensive medications do not show complete efficacy in all subjects and often require combination therapy of three or more drugs to reach a target blood pressure, and ∼10% of individuals show limited reduction in blood pressure on all therapeutic regimens.111 This highlights the need for additional antihypertensive medications, both to improve efficacy of treatment and reduce the burden of side effects experienced, particularly where combination therapies are concerned. Among the associations reported in this manuscript, there is evidence of association for 15 genes that are either current drug targets or are potentially druggable based on the predicted potential of a protein to be modified by a small-molecule drug in our analyses. Two genes are targeted by currently widely applied drugs. The KCNJ11 product is targeted by several agents including the antihypertensive drug verapamil (DrugBank ID DB00661) and the glucose-lowering agent glyburide (DrugBank DB01016). NQO1 is targeted by several marketed anticoagulant drugs, including dicumarol and menadione (DrugBank DB00266 and DB00170). The protein encoded by RELA is part of the NF-κB protein complex, which is considered to be inhibited by several known drugs, including the antihypertensive olmesartan (DrugBank DB00275)112 and the alcohol deterrent drug disulfiram (DrugBank DB00822). A known side effect of disulfiram in presence of alcohol exposure is hypotension, which gives support to a potential role of RELA in hypertension.

Nine genes with evidence of association have also previously described small-molecule modulators (mainly inhibitory or binding) based on a query of the ChEMBL database. The genes are listed with the number of tool compounds in parentheses: PDE1A (42), CDK6 (405), ADK (483), MAP3K11 (192), RELA (289), KAT5 (25), and PIK3C2A (10). The number of molecules identified may indicate the extent of drug discovery research that has been focused on each target. Many are likely to be the focus of pre-existing drug development in industry that may still be ongoing or terminated.113 Once molecular properties of these compounds are considered to have a favorable profile, they could be investigated in animal models of hypertension; a large number of compounds have already been characterized: the ChEMBL database reports that 405 molecules show activity against CDK6. Most of these CDK6 inhibitors originate from the published GSK (Glaxosmithkline) kinase inhibitor set.113 A review of the molecular properties of these molecules in ChEMBL shows that they have similar drug-like features and are likely to be orally bioavailable (based on Lipinski’s rule of five compliance114). As we described earlier, association is limited to CDK6 only, and because many of these drug-like molecules would be suitable for immediate evaluation in animal models of hypertension, this might be a worthwhile experiment, even in the absence of other strong evidence to support the role of CDK6 in BP.

The 11 loci identified in the present study increase our knowledge on BP-related processes and shed light on plausible candidates at each locus and networks, via eQTL and pathway analysis. It is particularly interesting that most of the genes within the associations are suitable candidates for existing drugs or preclinical compounds. These new observations will help to improve our knowledge on BP and related mechanisms.

Contributor Information

Patricia B. Munroe, Email: p.b.munroe@qmul.ac.uk.

Brendan J. Keating, Email: bkeating@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

ChEMBL, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl

DrugBank, http://www.drugbank.ca

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org/

SNP Annotation and Proxy Search (SNAP), http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/snap/

UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu

References

- 1.Wilson P.W. Established risk factors and coronary artery disease: the Framingham Study. Am. J. Hypertens. 1994;7:7S–12S. doi: 10.1093/ajh/7.7.7s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawes C.M.M., Vander Hoorn S., Rodgers A., International Society of Hypertension Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet. 2008;371:1513–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy D., DeStefano A.L., Larson M.G., O’Donnell C.J., Lifton R.P., Gavras H., Cupples L.A., Myers R.H. Evidence for a gene influencing blood pressure on chromosome 17. Genome scan linkage results for longitudinal blood pressure phenotypes in subjects from the framingham heart study. Hypertension. 2000;36:477–483. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kupper N., Willemsen G., Riese H., Posthuma D., Boomsma D.I., de Geus E.J. Heritability of daytime ambulatory blood pressure in an extended twin design. Hypertension. 2005;45:80–85. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000149952.84391.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy D., Ehret G.B., Rice K., Verwoert G.C., Launer L.J., Dehghan A., Glazer N.L., Morrison A.C., Johnson A.D., Aspelund T. Genome-wide association study of blood pressure and hypertension. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:677–687. doi: 10.1038/ng.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Padmanabhan S., Newton-Cheh C., Dominiczak A.F. Genetic basis of blood pressure and hypertension. Trends Genet. 2012;28:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franceschini N., Reiner A.P., Heiss G. Recent findings in the genetics of blood pressure and hypertension traits. Am. J. Hypertens. 2011;24:392–400. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganesh S.K., Tragante V., Guo W., Guo Y., Lanktree M.B., Smith E.N., Johnson T., Castillo B.A., Barnard J., Baumert J., CARDIOGRAM, METASTROKE. LifeLines Cohort Study Loci influencing blood pressure identified using a cardiovascular gene-centric array. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22:1663–1678. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehret G.B., Munroe P.B., Rice K.M., Bochud M., Johnson A.D., Chasman D.I., Smith A.V., Tobin M.D., Verwoert G.C., Hwang S.J., International Consortium for Blood Pressure Genome-Wide Association Studies. CARDIoGRAM consortium. CKDGen Consortium. KidneyGen Consortium. EchoGen consortium. CHARGE-HF consortium Genetic variants in novel pathways influence blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Nature. 2011;478:103–109. doi: 10.1038/nature10405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newton-Cheh C., Johnson T., Gateva V., Tobin M.D., Bochud M., Coin L., Najjar S.S., Zhao J.H., Heath S.C., Eyheramendy S., Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Genome-wide association study identifies eight loci associated with blood pressure. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:666–676. doi: 10.1038/ng.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson T., Gaunt T.R., Newhouse S.J., Padmanabhan S., Tomaszewski M., Kumari M., Morris R.W., Tzoulaki I., O’Brien E.T., Poulter N.R., Cardiogenics Consortium. Global BPgen Consortium Blood pressure loci identified with a gene-centric array. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;89:688–700. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu X., Young J.H., Fox E., Keating B.J., Franceschini N., Kang S., Tayo B., Adeyemo A., Sun Y.V., Li Y. Combined admixture mapping and association analysis identifies a novel blood pressure genetic locus on 5p13: contributions from the CARe consortium. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:2285–2295. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhan W., Cruickshanks K.J., Klein B.E.K., Klein R., Huang G.-H., Pankow J.S., Gangnon R.E., Tweed T.S. Generational differences in the prevalence of hearing impairment in older adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010;171:260–266. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keating B.J., Tischfield S., Murray S.S., Bhangale T., Price T.S., Glessner J.T., Galver L., Barrett J.C., Grant S.F., Farlow D.N. Concept, design and implementation of a cardiovascular gene-centric 50 k SNP array for large-scale genomic association studies. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomaszewski M., Debiec R., Braund P.S., Nelson C.P., Hardwick R., Christofidou P., Denniff M., Codd V., Rafelt S., van der Harst P. Genetic architecture of ambulatory blood pressure in the general population: insights from cardiovascular gene-centric array. Hypertension. 2010;56:1069–1076. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.155721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke R., Peden J.F., Hopewell J.C., Kyriakou T., Goel A., Heath S.C., Parish S., Barlera S., Franzosi M.G., Rust S., PROCARDIS Consortium Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:2518–2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IBC 50K CAD Consortium Large-scale gene-centric analysis identifies novel variants for coronary artery disease. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asselbergs F.W., Guo Y., van Iperen E.P., Sivapalaratnam S., Tragante V., Lanktree M.B., Lange L.A., Almoguera B., Appelman Y.E., Barnard J., LifeLines Cohort Study Large-scale gene-centric meta-analysis across 32 studies identifies multiple lipid loci. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:823–838. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cappola T.P., Li M., He J., Ky B., Gilmore J., Qu L., Keating B., Reilly M., Kim C.E., Glessner J. Common variants in HSPB7 and FRMD4B associated with advanced heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:147–154. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.898395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxena R., Elbers C.C., Guo Y., Peter I., Gaunt T.R., Mega J.L., Lanktree M.B., Tare A., Castillo B.A., Li Y.R., Look AHEAD Research Group. DIAGRAM consortium Large-scale gene-centric meta-analysis across 39 studies identifies type 2 diabetes loci. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:410–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo Y., Lanktree M.B., Taylor K.C., Hakonarson H., Lange L.A., Keating B.J., IBC 50K SNP array BMI Consortium Gene-centric meta-analyses of 108 912 individuals confirm known body mass index loci and reveal three novel signals. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013;22:184–201. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson A.D., Newton-Cheh C., Chasman D.I., Ehret G.B., Johnson T., Rose L., Rice K., Verwoert G.C., Launer L.J., Gudnason V., Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology Consortium. Global BPgen Consortium. Women’s Genome Health Study Association of hypertension drug target genes with blood pressure and hypertension in 86,588 individuals. Hypertension. 2011;57:903–910. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.158667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Bakker P.I.W., Ferreira M.A.R., Jia X., Neale B.M., Raychaudhuri S., Voight B.F. Practical aspects of imputation-driven meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17(R2):R122–R128. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heap G.A., Trynka G., Jansen R.C., Bruinenberg M., Swertz M.A., Dinesen L.C., Hunt K.A., Wijmenga C., Vanheel D.A., Franke L. Complex nature of SNP genotype effects on gene expression in primary human leucocytes. BMC Med. Genomics. 2009;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lo K.S., Wilson J.G., Lange L.A., Folsom A.R., Galarneau G., Ganesh S.K., Grant S.F., Keating B.J., McCarroll S.A., Mohler E.R., 3rd Genetic association analysis highlights new loci that modulate hematological trait variation in Caucasians and African Americans. Hum. Genet. 2011;129:307–317. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0925-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson A.D., Handsaker R.E., Pulit S.L., Nizzari M.M., O’Donnell C.J., de Bakker P.I. SNAP: a web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2938–2939. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ridker P.M., Chasman D.I., Zee R.Y., Parker A., Rose L., Cook N.R., Buring J.E., Women’s Genome Health Study Working Group Rationale, design, and methodology of the Women’s Genome Health Study: a genome-wide association study of more than 25,000 initially healthy american women. Clin. Chem. 2008;54:249–255. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.099366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diercks G.F., van Boven A.J., Hillege H.L., Janssen W.M., Kors J.A., de Jong P.E., Grobbee D.E., Crijns H.J., van Gilst W.H. Microalbuminuria is independently associated with ischaemic electrocardiographic abnormalities in a large non-diabetic population. The PREVEND (Prevention of REnal and Vascular ENdstage Disease) study. Eur. Heart J. 2000;21:1922–1927. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stolk R.P., Rosmalen J.G., Postma D.S., de Boer R.A., Navis G., Slaets J.P., Ormel J., Wolffenbuttel B.H. Universal risk factors for multifactorial diseases: LifeLines: a three-generation population-based study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2008;23:67–74. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ward L.D., Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(D1):D930–D934. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang K., Li M., Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyle A.P., Hong E.L., Hariharan M., Cheng Y., Schaub M.A., Kasowski M., Karczewski K.J., Park J., Hitz B.C., Weng S. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012;22:1790–1797. doi: 10.1101/gr.137323.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernstein B.E., Birney E., Dunham I., Green E.D., Gunter C., Snyder M., ENCODE Project Consortium An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y.I., Wise P.H., Butte A.J. The “etiome”: identification and clustering of human disease etiological factors. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(Suppl 2):S14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-S2-S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talmud P.J., Drenos F., Shah S., Shah T., Palmen J., Verzilli C., Gaunt T.R., Pallas J., Lovering R., Li K., ASCOT investigators. NORDIL investigators. BRIGHT Consortium Gene-centric association signals for lipids and apolipoproteins identified via the HumanCVD BeadChip. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;85:628–642. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ekins S., Mestres J., Testa B. In silico pharmacology for drug discovery: applications to targets and beyond. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007;152:21–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Volkamer A., Kuhn D., Grombacher T., Rippmann F., Rarey M. Combining global and local measures for structure-based druggability predictions. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012;52:360–372. doi: 10.1021/ci200454v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Göring H.H., Curran J.E., Johnson M.P., Dyer T.D., Charlesworth J., Cole S.A., Jowett J.B., Abraham L.J., Rainwater D.L., Comuzzie A.G. Discovery of expression QTLs using large-scale transcriptional profiling in human lymphocytes. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1208–1216. doi: 10.1038/ng2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Idaghdour Y., Czika W., Shianna K.V., Lee S.H., Visscher P.M., Martin H.C., Miclaus K., Jadallah S.J., Goldstein D.B., Wolfinger R.D., Gibson G. Geographical genomics of human leukocyte gene expression variation in southern Morocco. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:62–67. doi: 10.1038/ng.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emilsson V., Thorleifsson G., Zhang B., Leonardson A.S., Zink F., Zhu J., Carlson S., Helgason A., Walters G.B., Gunnarsdottir S. Genetics of gene expression and its effect on disease. Nature. 2008;452:423–428. doi: 10.1038/nature06758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fehrmann R.S., Jansen R.C., Veldink J.H., Westra H.J., Arends D., Bonder M.J., Fu J., Deelen P., Groen H.J., Smolonska A. Trans-eQTLs reveal that independent genetic variants associated with a complex phenotype converge on intermediate genes, with a major role for the HLA. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehta D., Heim K., Herder C., Carstensen M., Eckstein G., Schurmann C., Homuth G., Nauck M., Völker U., Roden M. Impact of common regulatory single-nucleotide variants on gene expression profiles in whole blood. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;21:48–54. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sasayama D., Hori H., Nakamura S., Miyata R., Teraishi T., Hattori K., Ota M., Yamamoto N., Higuchi T., Amano N., Kunugi H. Identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms regulating peripheral blood mRNA expression with genome-wide significance: an eQTL study in the Japanese population. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dixon A.L., Liang L., Moffatt M.F., Chen W., Heath S., Wong K.C., Taylor J., Burnett E., Gut I., Farrall M. A genome-wide association study of global gene expression. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1202–1207. doi: 10.1038/ng2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liang L., Morar N., Dixon A.L., Lathrop G.M., Abecasis G.R., Moffatt M.F., Cookson W.O. A cross-platform analysis of 14,177 expression quantitative trait loci derived from lymphoblastoid cell lines. Genome Res. 2013;23:716–726. doi: 10.1101/gr.142521.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stranger B.E., Nica A.C., Forrest M.S., Dimas A., Bird C.P., Beazley C., Ingle C.E., Dunning M., Flicek P., Koller D. Population genomics of human gene expression. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1217–1224. doi: 10.1038/ng2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kwan T., Benovoy D., Dias C., Gurd S., Provencher C., Beaulieu P., Hudson T.J., Sladek R., Majewski J. Genome-wide analysis of transcript isoform variation in humans. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:225–231. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dimas A.S., Deutsch S., Stranger B.E., Montgomery S.B., Borel C., Attar-Cohen H., Ingle C., Beazley C., Gutierrez Arcelus M., Sekowska M. Common regulatory variation impacts gene expression in a cell type-dependent manner. Science. 2009;325:1246–1250. doi: 10.1126/science.1174148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cusanovich D.A., Billstrand C., Zhou X., Chavarria C., De Leon S., Michelini K., Pai A.A., Ober C., Gilad Y. The combination of a genome-wide association study of lymphocyte count and analysis of gene expression data reveals novel asthma candidate genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:2111–2123. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grundberg E., Small K.S., Hedman A.K., Nica A.C., Buil A., Keildson S., Bell J.T., Yang T.P., Meduri E., Barrett A., Multiple Tissue Human Expression Resource (MuTHER) Consortium Mapping cis- and trans-regulatory effects across multiple tissues in twins. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1084–1089. doi: 10.1038/ng.2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mangravite L.M., Engelhardt B.E., Medina M.W., Smith J.D., Brown C.D., Chasman D.I., Mecham B.H., Howie B., Shim H., Naidoo D. A statin-dependent QTL for GATM expression is associated with statin-induced myopathy. Nature. 2013;502:377–380. doi: 10.1038/nature12508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fairfax B.P., Makino S., Radhakrishnan J., Plant K., Leslie S., Dilthey A., Ellis P., Langford C., Vannberg F.O., Knight J.C. Genetics of gene expression in primary immune cells identifies cell type-specific master regulators and roles of HLA alleles. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:502–510. doi: 10.1038/ng.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murphy A., Chu J.H., Xu M., Carey V.J., Lazarus R., Liu A., Szefler S.J., Strunk R., Demuth K., Castro M. Mapping of numerous disease-associated expression polymorphisms in primary peripheral blood CD4+ lymphocytes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:4745–4757. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heinzen E.L., Ge D., Cronin K.D., Maia J.M., Shianna K.V., Gabriel W.N., Welsh-Bohmer K.A., Hulette C.M., Denny T.N., Goldstein D.B. Tissue-specific genetic control of splicing: implications for the study of complex traits. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zeller T., Wild P., Szymczak S., Rotival M., Schillert A., Castagne R., Maouche S., Germain M., Lackner K., Rossmann H. Genetics and beyond—the transcriptome of human monocytes and disease susceptibility. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barreiro L.B., Tailleux L., Pai A.A., Gicquel B., Marioni J.C., Gilad Y. Deciphering the genetic architecture of variation in the immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:1204–1209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115761109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greenawalt D.M., Dobrin R., Chudin E., Hatoum I.J., Suver C., Beaulaurier J., Zhang B., Castro V., Zhu J., Sieberts S.K. A survey of the genetics of stomach, liver, and adipose gene expression from a morbidly obese cohort. Genome Res. 2011;21:1008–1016. doi: 10.1101/gr.112821.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kompass K.S., Witte J.S. Co-regulatory expression quantitative trait loci mapping: method and application to endometrial cancer. BMC Med. Genomics. 2011;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Q., Seo J.H., Stranger B., McKenna A., Pe’er I., Laframboise T., Brown M., Tyekucheva S., Freedman M.L. Integrative eQTL-based analyses reveal the biology of breast cancer risk loci. Cell. 2013;152:633–641. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Webster J.A., Gibbs J.R., Clarke J., Ray M., Zhang W., Holmans P., Rohrer K., Zhao A., Marlowe L., Kaleem M., NACC-Neuropathology Group Genetic control of human brain transcript expression in Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;84:445–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zou F., Chai H.S., Younkin C.S., Allen M., Crook J., Pankratz V.S., Carrasquillo M.M., Rowley C.N., Nair A.A., Middha S., Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium Brain expression genome-wide association study (eGWAS) identifies human disease-associated variants. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Colantuoni C., Lipska B.K., Ye T., Hyde T.M., Tao R., Leek J.T., Colantuoni E.A., Elkahloun A.G., Herman M.M., Weinberger D.R., Kleinman J.E. Temporal dynamics and genetic control of transcription in the human prefrontal cortex. Nature. 2011;478:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature10524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu C., Cheng L., Badner J.A., Zhang D., Craig D.W., Redman M., Gershon E.S. Whole-genome association mapping of gene expression in the human prefrontal cortex. Mol. Psychiatry. 2010;15:779–784. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gibbs J.R., van der Brug M.P., Hernandez D.G., Traynor B.J., Nalls M.A., Lai S.L., Arepalli S., Dillman A., Rafferty I.P., Troncoso J. Abundant quantitative trait loci exist for DNA methylation and gene expression in human brain. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang B., Gaiteri C., Bodea L.-G., Wang Z., McElwee J., Podtelezhnikov A.A., Zhang C., Xie T., Tran L., Dobrin R. Integrated systems approach identifies genetic nodes and networks in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2013;153:707–720. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schadt E.E., Molony C., Chudin E., Hao K., Yang X., Lum P.Y., Kasarskis A., Zhang B., Wang S., Suver C. Mapping the genetic architecture of gene expression in human liver. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Innocenti F., Cooper G.M., Stanaway I.B., Gamazon E.R., Smith J.D., Mirkov S., Ramirez J., Liu W., Lin Y.S., Moloney C. Identification, replication, and functional fine-mapping of expression quantitative trait loci in primary human liver tissue. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grundberg E., Kwan T., Ge B., Lam K.C., Koka V., Kindmark A., Mallmin H., Dias J., Verlaan D.J., Ouimet M. Population genomics in a disease targeted primary cell model. Genome Res. 2009;19:1942–1952. doi: 10.1101/gr.095224.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kabakchiev B., Silverberg M.S. Expression quantitative trait loci analysis identifies associations between genotype and gene expression in human intestine. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1488–1496. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.03.001. e1–e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hao K., Bossé Y., Nickle D.C., Paré P.D., Postma D.S., Laviolette M., Sandford A., Hackett T.L., Daley D., Hogg J.C. Lung eQTLs to help reveal the molecular underpinnings of asthma. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ding J., Gudjonsson J.E., Liang L., Stuart P.E., Li Y., Chen W., Weichenthal M., Ellinghaus E., Franke A., Cookson W. Gene expression in skin and lymphoblastoid cells: Refined statistical method reveals extensive overlap in cis-eQTL signals. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;87:779–789. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang R.S., Gamazon E.R., Ziliak D., Wen Y., Im H.K., Zhang W., Wing C., Duan S., Bleibel W.K., Cox N.J., Dolan M.E. Population differences in microRNA expression and biological implications. RNA Biol. 2011;8:692–701. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.4.16029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rantalainen M., Herrera B.M., Nicholson G., Bowden R., Wills Q.F., Min J.L., Neville M.J., Barrett A., Allen M., Rayner N.W. MicroRNA expression in abdominal and gluteal adipose tissue is associated with mRNA expression levels and partly genetically driven. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Newton-Cheh C., Larson M.G., Vasan R.S., Levy D., Bloch K.D., Surti A., Guiducci C., Kathiresan S., Benjamin E.J., Struck J. Association of common variants in NPPA and NPPB with circulating natriuretic peptides and blood pressure. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:348–353. doi: 10.1038/ng.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Salvi E., Kutalik Z., Glorioso N., Benaglio P., Frau F., Kuznetsova T., Arima H., Hoggart C., Tichet J., Nikitin Y.P. Genomewide association study using a high-density single nucleotide polymorphism array and case-control design identifies a novel essential hypertension susceptibility locus in the promoter region of endothelial NO synthase. Hypertension. 2012;59:248–255. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.181990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wain L.V., Verwoert G.C., O’Reilly P.F., Shi G., Johnson T., Johnson A.D., Bochud M., Rice K.M., Henneman P., Smith A.V., LifeLines Cohort Study. EchoGen consortium. AortaGen Consortium. CHARGE Consortium Heart Failure Working Group. KidneyGen consortium. CKDGen consortium. Cardiogenics consortium. CardioGram Genome-wide association study identifies six new loci influencing pulse pressure and mean arterial pressure. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:1005–1011. doi: 10.1038/ng.922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Padmanabhan S., Melander O., Johnson T., Di Blasio A.M., Lee W.K., Gentilini D., Hastie C.E., Menni C., Monti M.C., Delles C., Global BPgen Consortium Genome-wide association study of blood pressure extremes identifies variant near UMOD associated with hypertension. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Giachini F.R., Lima V.V., Carneiro F.S., Tostes R.C., Webb R.C. Decreased cGMP level contributes to increased contraction in arteries from hypertensive rats: role of phosphodiesterase 1. Hypertension. 2011;57:655–663. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.164327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schermuly R.T., Pullamsetti S.S., Kwapiszewska G., Dumitrascu R., Tian X., Weissmann N., Ghofrani H.A., Kaulen C., Dunkern T., Schudt C. Phosphodiesterase 1 upregulation in pulmonary arterial hypertension: target for reverse-remodeling therapy. Circulation. 2007;115:2331–2339. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.676809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhu F., Sun Y., Wang M., Ma S., Chen X., Cao A., Chen F., Qiu Y., Liao Y. Correlation between HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQB1 polymorphism and autoantibodies against angiotensin AT(1) receptors in Chinese patients with essential hypertension. Clin. Cardiol. 2011;34:302–308. doi: 10.1002/clc.20852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Köttgen A., Albrecht E., Teumer A., Vitart V., Krumsiek J., Hundertmark C., Pistis G., Ruggiero D., O’Seaghdha C.M., Haller T., LifeLines Cohort Study. CARDIoGRAM Consortium. DIAGRAM Consortium. ICBP Consortium. MAGIC Consortium Genome-wide association analyses identify 18 new loci associated with serum urate concentrations. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:145–154. doi: 10.1038/ng.2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Köttgen A., Pattaro C., Böger C.A., Fuchsberger C., Olden M., Glazer N.L., Parsa A., Gao X., Yang Q., Smith A.V. New loci associated with kidney function and chronic kidney disease. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:376–384. doi: 10.1038/ng.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gollob M.H., Green M.S., Tang A.S., Gollob T., Karibe A., Ali Hassan A.S., Ahmad F., Lozado R., Shah G., Fananapazir L. Identification of a gene responsible for familial Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:1823–1831. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106143442403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Arad M., Maron B.J., Gorham J.M., Johnson W.H., Jr., Saul J.P., Perez-Atayde A.R., Spirito P., Wright G.B., Kanter R.J., Seidman C.E., Seidman J.G. Glycogen storage diseases presenting as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:362–372. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.van der Harst P., Zhang W., Mateo Leach I., Rendon A., Verweij N., Sehmi J., Paul D.S., Elling U., Allayee H., Li X. Seventy-five genetic loci influencing the human red blood cell. Nature. 2012;492:369–375. doi: 10.1038/nature11677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ganesh S.K., Zakai N.A., van Rooij F.J., Soranzo N., Smith A.V., Nalls M.A., Chen M.H., Kottgen A., Glazer N.L., Dehghan A. Multiple loci influence erythrocyte phenotypes in the CHARGE Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1191–1198. doi: 10.1038/ng.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Powell J.T., Turner R.J., Henney A.M., Miller G.J., Humphries S.E. An association between arterial pulse pressure and variation in the fibrillin-1 gene. Heart. 1997;78:396–398. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.4.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Medley T.L., Cole T.J., Gatzka C.D., Wang W.Y.S., Dart A.M., Kingwell B.A. Fibrillin-1 genotype is associated with aortic stiffness and disease severity in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2002;105:810–815. doi: 10.1161/hc0702.104129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lemaire S.A., McDonald M.-L.N., Guo D.C., Russell L., Miller C.C., 3rd, Johnson R.J., Bekheirnia M.R., Franco L.M., Nguyen M., Pyeritz R.E. Genome-wide association study identifies a susceptibility locus for thoracic aortic aneurysms and aortic dissections spanning FBN1 at 15q21.1. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:996–1000. doi: 10.1038/ng.934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lettre G., Jackson A.U., Gieger C., Schumacher F.R., Berndt S.I., Sanna S., Eyheramendy S., Voight B.F., Butler J.L., Guiducci C., Diabetes Genetics Initiative. FUSION. KORA. Prostate, Lung Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Nurses’ Health Study. SardiNIA Identification of ten loci associated with height highlights new biological pathways in human growth. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:584–591. doi: 10.1038/ng.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lango Allen H., Estrada K., Lettre G., Berndt S.I., Weedon M.N., Rivadeneira F., Willer C.J., Jackson A.U., Vedantam S., Raychaudhuri S. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature. 2010;467:832–838. doi: 10.1038/nature09410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Berndt S.I., Gustafsson S., Mägi R., Ganna A., Wheeler E., Feitosa M.F., Justice A.E., Monda K.L., Croteau-Chonka D.C., Day F.R. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 11 new loci for anthropometric traits and provides insights into genetic architecture. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:501–512. doi: 10.1038/ng.2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kamatani Y., Matsuda K., Okada Y., Kubo M., Hosono N., Daigo Y., Nakamura Y., Kamatani N. Genome-wide association study of hematological and biochemical traits in a Japanese population. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:210–215. doi: 10.1038/ng.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Okada Y., Hirota T., Kamatani Y., Takahashi A., Ohmiya H., Kumasaka N., Higasa K., Yamaguchi-Kabata Y., Hosono N., Nalls M.A. Identification of nine novel loci associated with white blood cell subtypes in a Japanese population. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Reiner A.P., Lettre G., Nalls M.A., Ganesh S.K., Mathias R., Austin M.A., Dean E., Arepalli S., Britton A., Chen Z. Genome-wide association study of white blood cell count in 16,388 African Americans: the continental origins and genetic epidemiology network (COGENT) PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xu W., Baribault H., Adamson E.D. Vinculin knockout results in heart and brain defects during embryonic development. Development. 1998;125:327–337. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yu L., Chen M., Zhao D., Yi P., Lu L., Han J., Zheng X., Zhou Y., Li L. The H19 gene imprinting in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Placenta. 2009;30:443–447. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sparago A., Cerrato F., Vernucci M., Ferrero G.B., Silengo M.C., Riccio A. Microdeletions in the human H19 DMR result in loss of IGF2 imprinting and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:958–960. doi: 10.1038/ng1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bliek J., Terhal P., van den Bogaard M.-J., Maas S., Hamel B., Salieb-Beugelaar G., Simon M., Letteboer T., van der Smagt J., Kroes H., Mannens M. Hypomethylation of the H19 gene causes not only Silver-Russell syndrome (SRS) but also isolated asymmetry or an SRS-like phenotype. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;78:604–614. doi: 10.1086/502981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Angelone T., Filice E., Pasqua T., Amodio N., Galluccio M., Montesanti G., Quintieri A.M., Cerra M.C. Nesfatin-1 as a novel cardiac peptide: identification, functional characterization, and protection against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013;70:495–509. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1138-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Islam A., Adamik B., Hawari F.I., Ma G., Rouhani F.N., Zhang J., Levine S.J. Extracellular TNFR1 release requires the calcium-dependent formation of a nucleobindin 2-ARTS-1 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:6860–6873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Oh-I S., Shimizu H., Satoh T., Okada S., Adachi S., Inoue K., Eguchi H., Yamamoto M., Imaki T., Hashimoto K. Identification of nesfatin-1 as a satiety molecule in the hypothalamus. Nature. 2006;443:709–712. doi: 10.1038/nature05162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kokubo Y., Tomoike H., Tanaka C., Banno M., Okuda T., Inamoto N., Kamide K., Kawano Y., Miyata T. Association of sixty-one non-synonymous polymorphisms in forty-one hypertension candidate genes with blood pressure variation and hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 2006;29:611–619. doi: 10.1291/hypres.29.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cardinale J.P., Sriramula S., Mariappan N., Agarwal D., Francis J. Angiotensin II-induced hypertension is modulated by nuclear factor-κB in the paraventricular nucleus. Hypertension. 2012;59:113–121. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.182154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Franceschini N., Fox E., Zhang Z., Edwards T.L., Nalls M.A., Sung Y.J., Tayo B.O., Sun Y.V., Gottesman O., Adeyemo A., Asian Genetic Epidemiology Network Consortium Genome-wide association analysis of blood-pressure traits in African-ancestry individuals reveals common associated genes in African and non-African populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;93:545–554. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Halterman J.A., Kwon H.M., Zargham R., Bortz P.D., Wamhoff B.R. Nuclear factor of activated T cells 5 regulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011;31:2287–2296. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.232165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Halterman J.A., Kwon H.M., Leitinger N., Wamhoff B.R. NFAT5 expression in bone marrow-derived cells enhances atherosclerosis and drives macrophage migration. Front. Physiol. 2012;3:313. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Elks C.E., Perry J.R., Sulem P., Chasman D.I., Franceschini N., He C., Lunetta K.L., Visser J.A., Byrne E.M., Cousminer D.L., GIANT Consortium Thirty new loci for age at menarche identified by a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:1077–1085. doi: 10.1038/ng.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kim Y.-H., Hwang J.H., Noh J.-R., Gang G.-T., Kim H., Son H.Y., Kwak T.H., Shong M., Lee I.K., Lee C.H. Activation of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase ameliorates spontaneous hypertension in an animal model via modulation of eNOS activity. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011;91:519–527. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.McDonald F.J., Western A.H., McNeil J.D., Thomas B.C., Olson D.R., Snyder P.M. Ubiquitin-protein ligase WWP2 binds to and downregulates the epithelial Na(+) channel. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F431–F436. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00080.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Persell S.D. Prevalence of resistant hypertension in the United States, 2003-2008. Hypertension. 2011;57:1076–1080. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.170308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cvek B., Dvorak Z. Targeting of nuclear factor-kappaB and proteasome by dithiocarbamate complexes with metals. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007;13:3155–3167. doi: 10.2174/138161207782110390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dranchak P., MacArthur R., Guha R., Zuercher W.J., Drewry D.H., Auld D.S., Inglese J. Profile of the GSK published protein kinase inhibitor set across ATP-dependent and-independent luciferases: implications for reporter-gene assays. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e57888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lipinski C.A., Lombardo F., Dominy B.W., Feeney P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.