Abstract

Objectives

Mechanical ventilation is associated with overwhelming inflammatory responses that are associated with ventilator- induced lung injury (VILI) in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. The activation of adenosine A2A receptors has been reported to attenuate inflammatory cascades.

Hypothesis

The administration of A2A receptors agonist ameliorates VILI.

Methods

Rats were subjected to hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation as a first hit to induce systemic inflammation. The animals randomly received the selective A2A receptor agonist CGS-21680 or a vehicle control in a blinded fashion at the onset of resuscitation phase. They were then randomized to receive mechanical ventilation as a second hit with a high tidal volume of 20 mL/kg and zero positive end-expiratory pressure, or a low tidal volume of 6 mL/kg with positive end-expiratory pressure of 5 cm H2O.

Results

The administration of CGS-21680 attenuated lung injury as evidenced by a decrease in respiratory elastance, lung edema, lung injury scores, neutrophil recruitment in the lung, and production of inflammatory cytokines, compared with the vehicle treated animals.

Conclusions

The selective A2A receptor agonist may have a place as a novel therapeutic approach in reducing VILI.

Keywords: acute respiratory distress syndrome, inflammation, neutrophils

Introduction

Hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation (HSR) triggers inflammatory responses as reflected by an increased infiltration of polymorphonuclear neutrophils into the lung and an enhanced expression of inflammatory cytokines including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. This inflammatory response has been associated with acute lung injury and its worst form the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (1). It has been shown that HSR can prime the immune system to enhance excessive host reaction in response to a secondary stimulus such as endotoxin (2, 3) and mechanical ventilation (4). We have recently shown in a rat model that HSR renders the lung more susceptible to mechanical ventilation resulting in ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) and kidney dysfunction (4, 5).

Adenosine—a purine nucleoside released during hypoxia, inflammation, and ischemia/reperfusion—is a potent agent to protect organ systems from injury by its anti-inflammatory properties (6 –10) to decrease macrophage activation, block endothelial polymorphonuclear neutrophils interactions, and reduce polymorphonuclear neutrophils-mediated injury and vascular derangement (11, 12). A couple of recent studies have demonstrated that mechanical ventilation in rats and mice increases the level of pulmonary adenosine (13, 14), and that mice deficient for extracellular adenosine generation show increased pulmonary edema and inflammation after VILI (14). Once in the extracellular milieu, adenosine exerts its biological effects through binding to the G-protein coupled adenosine receptors including A1R, A2AR, A2BR, and A3R (8, 15, 16). The A2AR expressed on leukocytes and lung displays high affinity for adenosine (8). Several studies have shown that activation of A2A receptor is protective against ischemia/reperfusion injury by decreasing the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules and the production of cytokines and reactive oxygen species (17–21). We thus hypothesized that a pharmacologic intervention with an A2AR agonist protects the lung from injury in a two-hit model of HSR followed by mechanical ventilation.

Methods

Surgical Preparation

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee at St. Michael’s Hospital. Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 280 –360 g (Charles River Labs, St. Constant, Quebec, Canada) were anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (8 mg/kg) intraperitoneally. Tracheostomy was performed for endotracheal intubation (14-gauge Angiocath Catheter, Becton Dickinson Infusion Therapy Systems, Sandy, UT). The animals were then ventilated (Servo 300 ventilator, Siemens, Sweden) using a tidal volume (Vt) of 6 mL/kg, positive end-expiratory pressure of 5 cm H2O, and a respiratory rate of 50 breaths/min under 40% FIO2. Anesthesia and muscle paralysis were maintained by a continuous infusion of ketamine (15 mg/kg/h), xylazine (3 mg/kg/h), and pancuronium (0.35mg/kg/h) through a tail vein. The right carotid artery was catheterized for monitoring mean arterial pressure (MAP), blood gas analysis (Ciba-Corning Model 248 blood gas analyzer; Corning Medical, Mefield, MA), and conduction of controlled hemorrhagic shock.

Hemorrhagic Shock/Resuscitation and A2AR Agonist Administration

Hemorrhagic shock was induced by blood withdrawal over 15 minutes to reach an MAP of 40 ± 5mmHg. The target MAP was achieved by further blood withdrawal if the MAP was > 45 mm Hg, or by injection of shed blood collected in a 0.1% citrate solution if the MAP was <35 mm Hg. The hypotension status was maintained for 60 minutes, followed by resuscitation by transfusion of the shed blood and Lactated Ringer’s (1:1 volume) to achieve an MAP of 70–80 mm Hg within 15 minutes.

The A2AR agonist CGS-21680 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in 45% (w/v) aqueous 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin, or an identical volume of placebo-control solution was administered at 0.3 mg/kg intravenously over 30 seconds at the onset of resuscitation phase. The administration of CGS-21680 and placebo control solution was chosen in a random and blinded fashion to the investigators who conducted the experiments.

Randomization of Mechanical Ventilation

After HSR and CGS-21680 administration, the animals were randomly assigned to receive mechanical ventilation for 3 hours at two different ventilator settings. In the high Vt group, the animals were ventilated with a Vt of 20 mL/kg and zero positive end expiratory pressure and in the low Vt group, the animals were ventilated with a Vt of 6 mL/kg at a positive end-expiratory pressure level of 5 cm H2O. Thus, there were a total of four groups: group 1 (high Vt + placebo, n =10); group 2 (high Vt + CGS-21680, n = 10); group 3 (low Vt + placebo, n = 10); and group 4 (low Vt +CGS-21680, n = 10).

Monitoring and Fluid Maintenance

In addition to MAP, heart rate and oxygen saturation were monitored in a real time fashion by placing a veterinary pulse coximeter (SpO2) (Nonin 8600, Plymouth, MN). Airway plateau pressure was measured by holding breath for 4 seconds at the end inspiratory phase. Lung elastance was calculated by using the formula: Lung elastance = (plateau pressure – positive end-expiratory pressure)/Vt. Lactated Ringer’s solution was infused (3 mL/hr) to maintain MAP, and a bolus of 1 mL shed blood was given hourly to replace blood loss due to sampling. Rectal temperature was maintained at 37°C ± 0.5°C by using a heating pad.

Measurements

On completion of the experiments, animals were sacrificed by injecting overdose of sodium pentobarbital followed by lung pressure-volume curve construction. The left lung was then lavaged for cell differentiation assay (n =10 per group). The right lung was used for estimation of wet-to-dry (W/D) weight ratio (n = 5 per group) or histology analysis by hematoxylin and eosin staining (n = 5 per group). The lung injury score (22) was graded by a pathologist (C.-F.L.) who was blinded to the experimental groups.

Cytokine profiles (multiplex including rat IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, granulocytemacrophage colony stimulating factor [GMCSF], interferon-γ and TNF-α; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were analyzed in plasma and lung-lavage fluids by a technician in a blinded manner.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SE. Comparison between the groups was performed using a two-way analysis of variance for repeated measurement. Post hoc analysis was conducted using the Bonferroni method. One-way analysis of variance followed by a Student’s t test was used where appropriate. A p value <0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Model

The amount of blood withdrawn was similar to reach target MAP during hemorrhagic shock (13.5 ±0.5 mL in HV + placebo vs. 13.2 ± 0.7 mL in HV + CGS-21680, and 13.3 ± 0.6 mL in LV + placebo vs. 13.6 ± 0.6 mL in LV + CGS-21680 group, p = not significant for all). The volume of fluid infused was identical in all animals in the resuscitation phase and thereafter during the mechanical ventilation period.

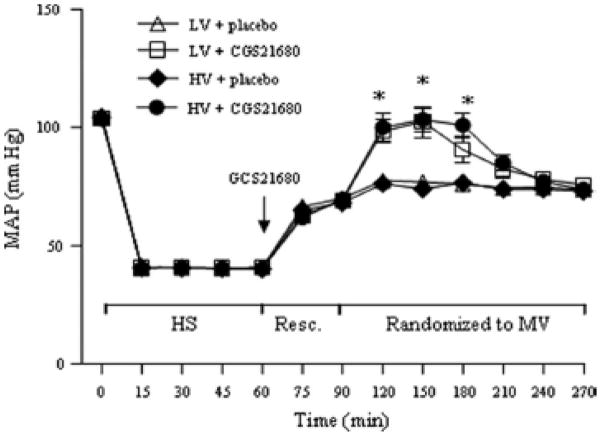

The MAP was similar at baseline and during HSR in all animals. For a given amount of fluid infused in all animals, the two groups of animals receiving CGS-21680 had greater MAP than the two placebo groups between 30 and 90 minutes after randomization to the two ventilatory strategies (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Time course of mean arterial pressure (MAP) during hemorrhagic shock (HS) and resuscitation (Resc.) and after randomization to mechanical ventilation (MV) of low volume (LV) with placebo, low volume with drug (CGS21680), high volume (HV) with placebo, and high tidal volume with drug, n=10 each. *p< 0.05 CGS21680 vs. placebo in identical conditions, respectively.

Blood Gas Analysis and Respiratory Mechanics

The mean values of PaO2 at baseline were similar in all animals and were lower in the HV + placebo group than in the LV groups 60 minutes after randomization into the two mechanical ventilatory strategies. The administration of CGS-21680 reserved the PaO2 in the HV group (Fig. 2A). The SpO2 value was significantly lower in the HV + placebo group than other groups, respectively, at the end of the experiments (Fig. 2B). The CGS-21680-treated groups showed a higher level of pH and HCO3− compared with the placebo group (Table 1) with no differences in PaCO2 values (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

PaO2, SpO2, and PaCO2 during the 3-hr period of mechanical ventilation after randomization (n=10 each). *p< 0.05 LV groups vs. HV groups (except LV + GCS21680 vs. HV + GCS21680 at 60 min); +p< 0.05 HV + placebo vs. other groups. LV, low volume; HV, high volume.

Table 1.

Time course for pH and HCO3− at baseline and after randomization for mechanical ventilation.

| Baseline | 5 Mins | 60 Mins | 120 Mins | 180 Mins | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | |||||

| LV + placebo | 7.390 ± 0.010 | 7.297 ± 0.013 | 7.340 ± 0.016 | 7.310 ± 0.024 | 7.313 ±0.025 |

| LV + CGS21680 | 7.374 ± 0.010 | 7.289 ± 0.015 | 7.357 ± 0.012 | 7.368 ± 0.017 | 7.344 ± 0.022 |

| HV + placebo | 7.384 ± 0.009 | 7.273 ± 0.015 | 7.295 ± 0.015a | 7.294 ± 0.013a | 7.242 ± 0.014a |

| HV + CGS21680 | 7.381 ± 0.009 | 7.269 ± 0.013 | 7.332 ± 0.012 | 7.365 ± 0.015 | 7.363 ± 0.018 |

| HCO3− | |||||

| LV + placebo | 22.5 ± 0.6 | 18.2 ± 0.5 | 19.3 ± 0.7 | 18.5 ± 1.0 | 18.2 ± 0.9 |

| LV + CGS21680 | 21.6 ± 0.5 | 17.6 ± 0.5 | 20.3 ± 0.7 | 20.7 ± 0.8 | 19.8 ± 0.9 |

| HV + placebo | 23.4 ± 0.6 | 17.3 ± 0.8 | 17.9 ± 0.6 | 17.5 ± 0.4a | 16.1 ± 0.7a |

| HV + CGS21680 | 22.0 ± 0.5 | 16.9 ± 0.7 | 20.1 ± 0.8 | 20.8 ± 0.9 | 20.4 ± 1.0 |

The levels of lung elastance at baseline were similar in all groups, but increased in the HV + placebo group than the other groups (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the static pressure–volume curve showed that the HV + placebo group had a lower compliance that was reversed by the treatment with CGS-21680 (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Elastance changes during mechanical ventilation after randomization. *p< 0.05 HV groups vs. LV groups. B, Static compliance curves of total respiratory system at the end of the experimental protocol. *p< 0.05 HV + placebo vs. other group. LV, low volume; HV, high volume.

PMN Lung Infiltration and Lung Injury

The total cell counts in lung lavage (bronchoalveolar lavage) fluid were significantly higher in the HV + placebo group (1.67 ± 0.21 X 106/mL) than in the other groups (0.99 ± 0.11 X 106/mL in HV + CGS-21680, 0.80 ± 0.08 X 106/mL in LV + CGS-21680, and 1.01 ± 0.10 X 106/mL in LV + placebo, respectively, p < 0.05 for all; Fig. 4A). Similarly, the HV + placebo group had a higher percentage of neutrophils than the other groups (27% ± 2% vs. 12% ± 2% in HV + CGS-21680, 9% ± 1% in LV +CGS-21680, and 14% ± 3% in LV + placebo, respectively, p< 0.05 for all; Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

A, The total cell counts in lung lavage fluids (n=10 each). B, The percentage of neutrophil counts in lung lavage fluids. C, Lung wet-dry ration (n=5 each) and D, lung injury scores. *p< 0.05 HV + placebo vs. other groups, respectively. +p <0.05 LV + GCS21680. LV, low volume; HV, high volume; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage.

The lung wet-to-dry ratio was 7.03 ±0.71 in the HV + placebo group, which was significantly higher than the other groups (5.28 ± 0.13 in HV + CGS-21680, 5.05 ± 0.12 in LV + CGS-21680, and 5.42 ± 0.02 in LV + placebo, respectively, p <0.05 for all; Fig. 4C). The lung injury score was higher in the HV + placebo group (15.8 ± 0.9) than in the other groups (2.5 ± 0.6 in HV + CGS-21680, 7.1 ± 1.2 in LV + CGS-21680 [both p <0.05], and 13.5 ± 1.3 in LV + placebo, respectively; Fig. 4D).

Lung histology shows that the administration of CGS-21680 attenuated alveolar collapse, perivascular and peribronchial edema, and polymorphonuclear neutrophils infiltration seen in the placebo group (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Representative lung histology slides (original magnification X 400). A, high volume + CGS21680, (B) high volume + placebo, (C), low volume + CGS21680 and (D) low volume + placebo.

Cytokine Profiles

Among the ten cytokines assayed, the plasma level of IL-1β was significant and TNF-α tended to be higher in the HV + placebo group than in the other groups (p <0.05, Figs. 6, 7, and 8). The lung lavage levels of IL-2, -6, -10, and TNF-α were higher, and GM-CSF tended to be higher in the HV + placebo group than in the other groups (p <0.05, Figs. 6–8).

Figure 6.

Levels of interleukin (IL)-1α, -1β, and -2 in plasma (n= 5 each) and lung lavage fluid (n=10) at the end of the experiments. *p<vs. other groups, respectively. LV, low volume; HV, high volume.

Figure 7.

Levels of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-6 and IL-10 in plasma (n=5 each) and lung lavage fluid (n=10) at the end of the experiments. *p< 0.05 vs. other groups, respectively. LV, low volume; HV, high volume.

Figure 8.

Levels of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulation factor (GM-CSF), interferon (IFN)-γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in plasma (n=5 each) and lung lavage fluid (n=10) at the end of the exrperiments. *p< 0.05 vs. other groups, respectively. LV, low volume; HV, high volume.

Discussion

The main finding of the present study is that the administration of a specific A2A receptor agonist dramatically attenuated inflammatory responses thus VILI in the two-hit model of ischemia and reperfusion followed by mechanical ventilation in rats. It is noteworthy that these beneficial effects of CGS-21680 were observed where investigators were blinded to the compound administration during the studies.

Over seven decades ago, Drury and Szent-Györgyi (23) discovered the role of adenosine as an extracellular signaling molecule, which later was shown to protect organ systems from injury in response to stress conditions including ischemia and reperfusion (22). The administration of adenosine has displayed a beneficial effect in protecting tissue from ischemia and reperfusion. However, an extremely short half-life (1–2 seconds) of injected adenosine in plasma had limited its role for clinical application (23–25).

The cloning of cell surface ligands to recognize adenosine provides one with a power approach to modulate the various effects of adenosine (8, 15). There are four G-protein coupled receptors A1, A2A, A2B, and A3, and each of them mediates specific effects of adenosine (8, 15).

The anti-inflammatory effects of adenosine are generally attributed to the occupancy of A2A receptor that is widely distributed in the human body with high expression in leukocytes and platelets, while expressed at intermediate levels in the lung (26). In ischemia reperfusion models, the use of A2A receptor agonists resulted in a decrease in macrophage activation and adhesion molecular expression on endothelial cells, blockage of endothelial-neutrophil interactions, and attenuation of vascular derangement (11, 12, 17–21). The administration of the A2A receptors agonist CGS-21680 has been shown to ameliorate lung injury in animal models of ischemia and reperfusion (12, 17). Furthermore, a reduced inflammatory response and preserved pulmonary function was achieved by using an A2A receptor agonist in a rabbit model of lung transplantation (18). We thus speculated that the activation of A2A receptor may have a place in the attenuation of VILI by its anti-inflammatory properties.

It is noteworthy that a recent study demonstrated in a model of LPS induced acute lung injury in mice that deletion of the A2B receptor gene was associated with reduced survival time and increased lung permeability (27). Furthermore, treatment with A2B receptor-selective antagonist resulted in enhanced pulmonary inflammation and lung permeability while an A2B receptor agonist attenuated VILI in wild-type mice. Taken together, our current and the recent study (27) suggest that both A2A and A2B receptor agonists may become a therapeutic approach in VILI.

Our HSR model is different from those ischemia reperfusion models previously described (12, 17). We used a shorter period of reperfusion (30 minutes) than the previous models in which a longer time of reperfusion (3 hours) was used (12, 17, 18). Thus, an inflammatory response was induced by HSR to prime the lung without causing lung injury in our rat model (18). Our model of HSR followed by mechanical ventilation is clinically relevant, since approximately 20% of patients who have hemorrhagic shock require mechanical ventilation. We have previously reported that the HSR renders the lung more susceptible to VILI (4). It has been well established that mechanical ventilation can cause biotrauma by releasing inflammatory cytokines in experimental and clinical settings (28 –30). Several clinical trials including the ARDS Network study demonstrated that patients with ARDS ventilated with low tidal volume had an improved survival rate associated with a decrease in circulating cytokine levels compared with those ventilated with high tidal volume (31, 32). However, the low tidal volume strategy may not apply to all patients with ARDS (33), thus an effective pharmacologic intervention is required to treat these patients. In the present study, we demonstrated that the administration of the A2A receptors agonist CGS-21680 protected the lung from injury associated with a decreased cytokine response.

We observed that the plasma levels of IL-1β and TNF-α decreased in the CGS-21680-treated animals ventilated with high tidal volume. Because IL-1β and TNF-α are early and central proinflammatory cytokines in response to stresses, the attenuation of these cytokines may have contributed to beneficial effects in the CGS-21680-treated animals.

Interestingly, the levels of IL-2, GMCSF, IL-10, and TNF-α in lung-lavage fluid decreased in the CGS-21680-treated animals than those in the placebo group under HV mechanical ventilation. IL-2 is produced by helper T (Th1) cells. The intrinsic death-sensitizing activity of IL-2 was believed to be a key mediator for apoptosis of peripheral autoreactive T cells. However, recent studies redefine the pivotal role for IL-2 as the major inducer for the developmental production of suppressive T regulatory cells (34). GM-CSF is a glycoprotein cytokine secreted by monocytes that regulate the proliferation and differentiation of myeloid cells and the activation of monocytes (32). GM-CSF has a stimulatory effect on a number of neutrophil functions (35). The IL-10 secretion was significantly increased by stimulation with GM-CSF in spleen cells compared with similarly cultured saline spleen cells (36). IL-10 was originally described as a cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor produced by Th2 cells that inhibit Th1 function. Much of the early studies with IL-10 focused on its ability to inhibit production of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β and TNF-α. In fact, a major stimulus for the production of IL-10 is inflammation itself, because IL-1β, TNF-α, and GM-CSF can stimulate IL-10 production directly, suggesting the existence of a negative feedback loop, whereby inflammatory processes are self limited by the endogenous production of IL-10 (37). Taken together, these findings suggest that the magnitude of the endogenous IL-10 response correlates with both the severity of the inflammatory insult and the concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α (38).

The cytokine profiles observed in the present study provide one with novel information suggesting that T-cell activation may have well taken place in response to a short term (i.e., 3.5 hours) of mechanical ventilation in an ARDS lung. This was evidenced by the release of the Th cytokines including IL-2 and IL-10. Clinical studies have suggested that the ratio of T cells expressing CD4+ over CD8+ could help diagnose ARDS and predict its outcome. Although the direct consequences of the cytokine responses in relation to VILI were not addressed in the present study, previous studies have demonstrated the importance of cytokines in the context of ARDS by showing that increased blood levels of cytokines were correlated with mortality rate in patients with ARDS (39).

Neutrophils are considered to be central to the pathogenesis of ARDS (40). The decreased neutrophil migration in the lung is believed to be related to the anti-inflammatory properties of CGS- 21680 in the treated groups (41, 42). Furthermore, the transient higher MAP values observed in the CGS-21680-treated animals may be due to preserved vascular integrity for a given amount of fluids infused in all animals.

We did not measure the level of adenosine in the present study. However, previous in vitro studies have revealed that supernatants from hypoxia- or stretch induced injury contained adenosine that diminished endothelial leakage (14, 43). Additional studies in vivo demonstrated prominent increases in pulmonary adenosine levels with mechanical ventilation (13, 14). The increased adenosine level was associated with the enhanced expression of ectoapyrase (CD39) and ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) that hydrolyze ATP to adenosine at the cell surface of neutrophils and endothelial cells (43). The CD39 deficient mice have been shown to have pressure- and time-dependent increases in pulmonary edema and inflammation following mechanical ventilation, and administration of CD39 deficient or CD73 deficient mice with soluble apyrase or 5′ nucleotidase, respectively, abolished such increases (14). An alternate source for adenosine formation is cyclic adenosine monophosphate. A previous study has reported an elevation of pulmonary cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels following VILI (27). In the present study, we noted that the CGS-21680-treated animals in the high volume group had the lowest lung injury score. This observation is in agreement with those reported by Eckle et al who have recently demonstrated a 1.5-fold increase in the expression of A2A receptor associated with a significant increase in A2A receptor mRNA level in a mouse model of VILI, and the A2A receptor signaling pathway further increased pulmonary levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (27).

Taken together, the previous work suggests that a more severe VILI resulted in a higher expression of A2A receptor and adenosine in the given lung conditions (27). Because both cyclic adenosine monophosphate and adenosine regulate the activities of the epithelial sodium channel and the chloride channel cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator to balance between fluid secretion and absorption in the alveolar space, the adenosine pathways to dry out the lungs during VILI may have contributed to the better preserved lung histology by surpassing the effects of leukocyte migration seen in the HV + CGS21680 group.

In summary, the present study suggests that a selective activation of adenosine A2A receptors by using CGS-21680 is protective in the two-hit model of VILI in rats. Further studies are warranted to confirm the observation in other models of VILI.

Acknowledgments

Supported, in part, by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to H.Z. and A.S.S.) and Ontario Thoracic Society (to H.Z.).

The authors thank Dr. Jack Haitsma for initial technical support in the study.

Footnotes

The authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Toda Y, Takahashi T, Maeshima K, et al. A neutrophil elastase inhibitor, sivelestat, ameliorates lung injury after hemorrhagic shock in rats. Int J Mol Med. 2007;19:237–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rotstein OD. Modeling the two-hit hypothesis for evaluating strategies to prevent organ injury after shock/resuscitation. J Trauma. 2003;54:203–206. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000064512.62949.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulman AM, Claridge JA, Ghezel-Ayagh A, et al. Differential local and systemic tumor necrosis factor-alpha responses to a second hit of lipopolysaccharide after hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2003;55:298–307. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000028970.50515.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crimi E, Zhang H, Han RN, et al. Ischemia and reperfusion increases susceptibility to ventilator-induced lung injury in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:178–186. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200507-1178OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouadma L, Dreyfuss D, Ricard JD, et al. Mechanical ventilation and hemorrhagic shock-resuscitation interact to increase inflammatory cytokine release in rats. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2601–2606. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000286398.78243.CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonioli L, Fornai M, Colucci R, et al. Pharmacological modulation of adenosine system: Novel options for treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:566–574. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Headrick JP, Hack B, Ashton KJ. Acute adenosinergic cardioprotection in ischemic reperfused hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:1797–1818. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00407.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linden J. Molecular approach to adenosine receptors: Receptor-mediated mechanisms of tissue protection. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:775–787. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredholm BB. Adenosine, an endogenous distress signal, modulates tissue damage and repair. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1315–1323. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufmann I, Hoelzl A, Schliephake F, et al. Effects of adenosine on functions of polymorphonuclear leukocytes from patients with septic shock. Shock. 2007;27:25–31. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000238066.00074.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredholm BB, Cunha RA, Svenningsson P. Pharmacology of adenosine A2A receptors and therapeutic applications. Curr Top Med Chem. 2003;3:413–426. doi: 10.2174/1568026033392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haskó G, Xu DZ, Lu Q, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor activation reduces lung injury in trauma/hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1119–1125. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000206467.19509.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douillet CD, Robinson WP, III, Milano PM, et al. Nucleotides induce IL-6 release from human airway epithelia via P2Y2 and p38 MAPK dependent pathways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L734–L746. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00389.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eckle T, Füllbier L, Wehrmann M, et al. Identification of ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73 in innate protection during acute lung injury. J Immunol. 2007;178:8127–8137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.8127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haskó G, Cronstein BN. Adenosine: An endogenous regulator of innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fortin A, Harbour D, Fernandes M, et al. Differential expression of adenosine receptors in human neutrophils: Up-regulation by specific Th1 cytokines and lipopolysaccharide. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:574–585. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0505249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivo J, Zeira E, Galun E, et al. Attenuation of reperfusion lung injury and apoptosis by A2A adenosine receptor activation is associated with modulation of Bcl-2 and Bax expression and activation of extracellular signal regulated kinases. Shock. 2007;27:266–273. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000235137.13152.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reece TB, Laubach VE, Tribble CG, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor agonist improves cardiac dysfunction from pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1189–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McPherson JA, Barringhaus KG, Bishop GG, et al. Adenosine A(2A) receptor stimulation reduces inflammation and neointimal growth in a murine carotid ligation model. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:791–796. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.5.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reutershan J, Cagnina RE, Chang D, et al. Therapeutic anti-inflammatory effects of myeloid cell adenosine receptor A2a stimulation in lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. J Immunol. 2007;179:1254–1263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan GW, Linden J, Buster BL, et al. Neutrophil A2A adenosine receptor inhibits inflammation in a rat model of meningitis: Synergy with the type IV phosphodiesterase inhibitor, rolipram. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1550–1560. doi: 10.1086/315084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ko SC, Zhang H, Haitsma JJ, et al. Effects of PEEP levels following repeated recruitment maneuvers on ventilator-induced lung injury. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52:514–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drury AN, Szent-Györgyi A. The physiological activity of adenine compounds with especial reference to their action upon the mammalian heart. J Physiol. 1929;68:213–237. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1929.sp002608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tung CS, Chu KM, Tseng CJ, et al. Adenosine in hemorrhagic shock: Possible role in attenuating sympathetic activation. Life Sci. 1987;41:1375–1382. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90612-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haskó G, Sitkovsky MV, Szabo C. Immunomodulatory and neuroprotective effects of inosine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spicuzza L, Di Maria G, Polosa R. Adenosine in the airways: Implications and applications. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eckle T, Grenz A, Laucher S, et al. A2B adenosine receptor signaling attenuates acute lung injury by enhancing alveolar fluid clearance in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3301–3315. doi: 10.1172/JCI34203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tremblay L, Valenza F, Ribeiro SP, et al. Injurious ventilatory strategies increase cytokines and c-fos m-RNA expression in an isolated rat lung model. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:944–952. doi: 10.1172/JCI119259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ranieri VM, Suter PM, Tortorella C, et al. Effect of mechanical ventilation on inflammatory mediators in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282:54–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tremblay LN, Miatto D, Hamid Q, et al. Injurious ventilation induces widespread pulmonary epithelial expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 messenger RNA. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1693–1700. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Headley AS, Tolley E, Meduri GU. Infections and the inflammatory response in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Chest. 1997;111:1306–1321. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.5.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gajic O, Dara SI, Mendez JL, et al. Ventilator associated lung injury in patients without acute lung injury at the onset of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1817–1824. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000133019.52531.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malek TR. The main function of IL-2 is to promote the development of T regulatory cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:961–965. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gasson JC, Weisbart RH, Kaufman SE, et al. Purified human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor: Direct action on neutrophils. Science. 1984;226:1339–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.6390681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khatami S, Brummer E, Stevens DA. Effects of granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in vivo on cytokine production and proliferation by spleen cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;125:198–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van der Poll T, Jansen J, Levi M, et al. Regulation of interleukin 10 release by tumor necrosis factor in humans and chimpanzees. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1985–1988. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scumpia PO, Moldawer LL. Biology of interleukin-10 and its regulatory roles in sepsis syndromes. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:468– 471. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000186268.53799.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abraham E. Neutrophils and acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S195–S199. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057843.47705.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee WL, Downey GP. Neutrophil activation and acute lung injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Day YJ, Marshall MA, Huang L, et al. Protection from ischemic liver injury by activation of A2A adenosine receptors during reperfusion: Inhibition of chemokine induction. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:285–293. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00348.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okusa MD, Linden J, Macdonald T, et al. Selective A2A adenosine receptor activation reduces ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:404–412. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.3.F404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eltzschig HK, Ibla JC, Furuta GT, et al. Coordinated adenine nucleotide phosphohydrolysis and nucleoside signaling in posthypoxic endothelium: Role of ectonucleotidases and adenosine A2B receptors. J Exp Med. 2003;198:783–796. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]