Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To investigate the performance of screening rectal cultures obtained 2 weeks before transrectal prostate biopsy to detect fluoroquinolone-resistant organisms and again at transrectal prostate biopsy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After institutional review board approval for observational study, we obtained a rectal culture on patients identified for a prostate biopsy but before antibiotic prophylaxis from September 12, 2011 to April 23, 2012. The specimen was cultured onto MacConkey agar with and without 1 µg/mL ciprofloxacin. We then obtained a second rectal culture immediately before prostate biopsy after 24 hours of ciprofloxacin prophylaxis. All cultures were blinded to the practitioner until the end of the study.

RESULTS

Of 108 patients enrolled, 58 patients had both rectal cultures for comparison. The median time duration between cultures was 14 (6–119) days. There were 54 of 58 concordant pairs (93%), which included 47 negative cultures and 7 positive cultures; 2 patients (3%) who were culture negative from the first screening culture became positive at biopsy. Sensitivity, specificity, negative, positive predictive values, and area under the operator curve were 95.9%, 77.8%, 95.9%, 77.8%, and 0.868, respectively. When Pseudomonas spp. are removed from the analysis, the area under the curve is increased to 0.927.

CONCLUSION

Screening rectal cultures 2 weeks before prostate biopsy has favorable test performance, suggesting screening cultures give an accurate estimate of fluoroquinolone-resistant colonization.

More than 1 million transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsies (TRUSP) are performed in the United States each year and are the most common means of diagnosing prostate cancer.1 Infectious complications include urinary tract infection, prostatitis, epididymo-orchitis, and sepsis.2,3 The most common antibiotic prophylaxis used and currently recommended by the American Urological Association are fluoroquinolones (FQs).2 Unfortunately, FQ resistance (FQ-R) has been cited as a major concern for the increasing rate of infectious complications after the procedure.1,4–7

More recently, the prevalence of FQ-R organisms in the rectal flora at prostate biopsy has prompted the use of rectal cultures to provide specific recommendations regarding prophylaxis antibiotics before biopsy.8–10 Rectal culture is used to identify FQ-R organisms before the biopsy. A positive result would lead to an antibiotic susceptibility profile to guide an alternative antibiotic for prophylaxis. If the rectal screening culture is negative for FQ-R, then FQ-based prophylaxis can be used. This rectal culture-based approach is referred to as “targeted prophylaxis” and has the potential to decrease infection rates.11,12

The rectal culture needs to be performed before TRUSP to allow time for a culture and potentially antimicrobial susceptibility results, when a targeted prophylaxis is used for TRUSP. The time interval between the rectal culture and biopsy has not been clearly established, as there is concern the flora might change over time. In addition, there are no statistical measures of performance of screening rectal cultures for the purpose of targeted prophylaxis.

Therefore, our primary aim in this present study is to assess the agreement between FQ-R screening rectal cultures obtained from the office visit (enrollment) before biopsy to a second culture performed at biopsy. In addition, we evaluate test characteristics such as sensitivity, specificity, negative, positive predictive values, and receiver operator curves (area under the curve [AUC]) of the screening culture using the culture at the biopsy as the reference standard.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

After institutional review board approval, we obtained informed consent from patients selected to undergo prostate biopsy at the Long Beach Veterans Affairs Medical Center (LBVA, Long Beach, CA) from September 12, 2011 to April 23, 2012. Patients were prospectively enrolled specifically for investigating the agreement of a culture obtained in the office on enrollment to a rectal culture obtained at biopsy. Rectal cultures were performed for research purposes only and could not change clinical care or antibiotics before the biopsy as the protocol was only approved for observational research. Therefore, the culture results were blinded to investigators until completion of the study.

Microbiologic Evaluation

On enrollment, we obtained a rectal culture using a single culturette with Cary-Blair Media (Venturi Transystem Swabs, Copan Diagnostics, Murrieta, CA) in the outpatient office setting. The swab was first emulsified in 0.5 mL of sterile saline and ~0.05 mL and then cultured onto MacConkey agar with and without 1 µg/mL of ciprofloxacin. The MacConkey agar without ciprofloxacin served to assess adequacy of the specimen. Organisms that grew from the ciprofloxacin-containing media were subcultured and identified using the VITEK 2 automated system using GN-ID cards (bioMerieux, Durham, NC) and the minimum inhibitory concentration to ciprofloxacin was established using an Etest (bioMerieux) and Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (M100-20) guidelines.13

Clinical Evaluation

We provided instructions regarding the patients’ prophylaxis regimen as per LBVA protocol, which included a 3-day regimen of ciprofloxacin 500 mg every 12 hours starting the morning before the biopsy. All patients used a single bisacodyl suppository the morning of the prostate biopsy. Immediately before performing the biopsy, the physician obtained the second (confirmatory) rectal swab. The same screening culture protocol as previously described was used. The medical record was reviewed 30 days after prostate biopsy to investigate if a prostate biopsy-related infection was noted; however, the patients were not contacted after biopsy for study purposes.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was the agreement of office culture with the biopsy culture as a dichotomous variable (positive vs negative). We used the kappa statistic to test the agreement of the twopaired cultures. Landis and Kock had previously reported standards for the strength of agreement for the kappa coefficient as 0 = poor, 0.1–0.2 = slight, 0.21–0.4 = fair, 0.41–0.60 = moderate, 0.61–0.8 = substantial, and 0.81–1 = almost perfect.14 We estimate a sample size of 108 patients needed to show a significant difference (80% power and alpha of 0.05) assuming 20% of the population is colonized with FQ-R organisms.15

We used the statistical program SPSS v20 (IBM, Chicago, IL) to perform the statistical analysis. The t-test or one-way analysis of variance was used to compare continuous variables among groups. In addition, the sensitivity, specificity, negative, and positive predictive value were calculated. We used the culture at biopsy as the reference “standard” to determine the sensitivity, specificity, negative, and positive predictive values of the screening culture. A false negative is defined as a culture that is negative for FQ-R organisms at screening; however, the result is positive for FQ-R organisms at biopsy. A false positive is a positive culture at screening that is negative at prostate biopsy. Receiver operator curves were used to generate an AUC with a value of 0.75 to be clinically useful and >0.80 to be considered a high value.16

RESULTS

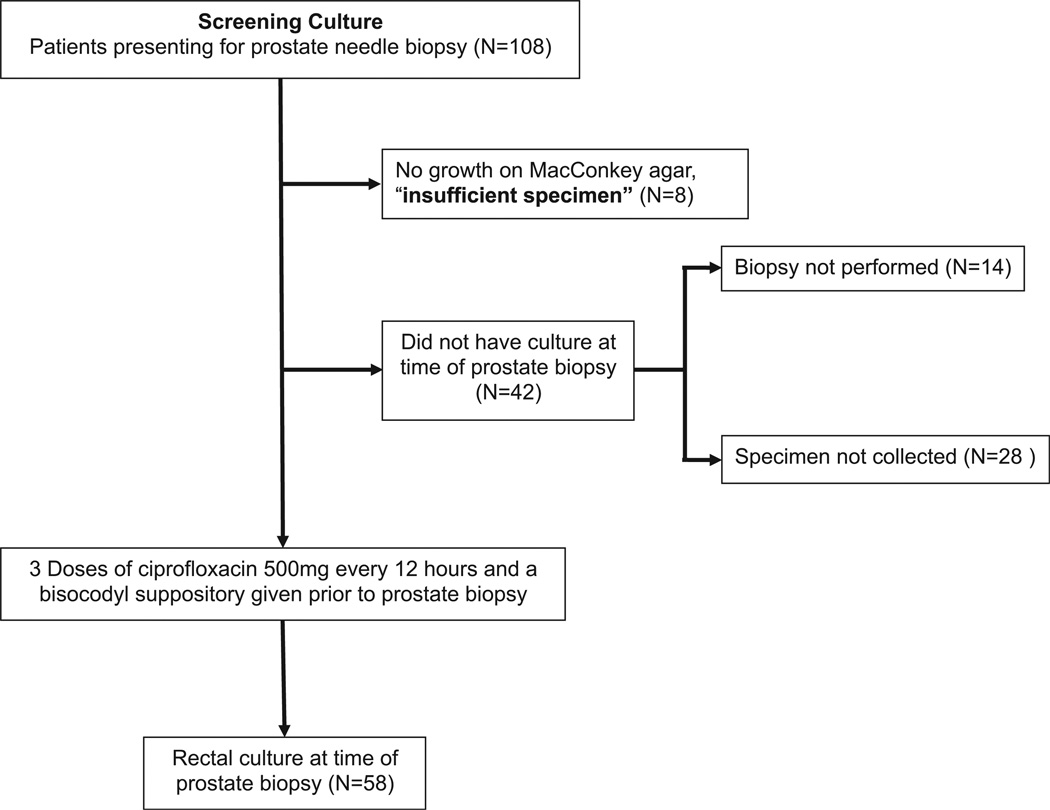

We enrolled 108 patients with mixed ethnicity or race as follows: 69% white, 14% Hispanic, 10% black, and 7% Asian. Eight patients had no growth on the MacConkey agar without ciprofloxacin and were therefore excluded because of an inadequate sample. The overall FQ-R was detected in 18 of 100 patients (18%) from the initial office-based rectal culture. Fifty-eight patients had both cultures for comparison. We excluded 28 patients for whom either the biopsy was delayed by comorbidities,5 the biopsy was canceled,6 had an active urinary tract infection,1 did not present for biopsy,2 or did not have a second culture at time of biopsy (Fig. 1). Charlson comorbidity score was lower for those included for analysis compared with those excluded (1.7 vs 2.5; P = .021) (Table 1). The median time between 2 cultures was 14 (4–119) days and a mean of 19.8 days for the 58 paired-samples included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of those included (cultures at both time points obtained) and excluded (did not receive culture at biopsy) from the final analysis

| Included (N = 58) |

Excluded (N = 50) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Students t |

| Number of patients | 58 | 50 | |

| Age | 65 (6.7) | 66 (6.0) | .278 |

| BMI | 29.5 (5.8) | 28.8 (4.9) | .512 |

| PSA | 5.98 (2.9) | 7.36 (8.0) | .25 |

| CCI | 1.71 (1.5) | 2.5 (1.9) | .021 |

| N (%) | N (%) | Chi-squared | |

| FQ-resistant colonization | 9 (15.5) | 9 (18) | .73 |

| Race or ethnicity | |||

| White | 43 (74.1) | 32 (64) | .179 |

| Hispanic | 7 (12.1) | 8 (16) | |

| Asian | 5 (8.6) | 2 (4) | |

| Black | 3 (5.2) | 8 (16) | |

| Previous prostate biopsy | |||

| 0 | 38 (65.5) | 37 (74) | .773 |

| 1 | 14 (24.1) | 9 (18) | |

| ≥2 | 6 (10.4) | 4 (8) | |

| Active surveillance | 4 (6.9) | 4 (8) | |

| Prostate cancer | |||

| Positive prostate biopsy | 20 (34.4) | ||

| Biopsy Gleason sum | |||

| 6 | 14 (70) | ||

| 7 | 4 (20) | ||

| ≥8 | 2 (10) | ||

BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; FQ, fluoroquinolone; PSA, prostate-specific antigen, SD, standard deviation.

The culture obtained approximately 2 weeks before TRUSP represented the FQ-R status in the rectal flora at biopsy with 93% of the cultures being the same (concordant pairs). Specifically, concordant cultures included 47 negative cultures and 7 positive cultures (κ = 0.737, P <.001). Four pairs of cultures were discordant between specimens taken during screening culture and at biopsy (Fig. 2). FQ-R E coli was recovered from 2 patients on their screening culture that eventually was negative at biopsy (false positive). One patient was positive for a FQ-R Pseudomonas spp. (7 days before TRUSP) and 1 patient was positive for FQ-R E coli (13 days before TRUSP).

Figure 2.

Concordance between the culture before biopsy and culture at prostate biopsy.

All organisms recovered from the MacConkey agar containing ciprofloxacin were FQ-R E coli, except 2 that were Pseudomonas spp. No demographic differences were detected between groups negative or positive for FQ-R organisms in regards to age, body mass index, diabetes, ethnicity or race, prostate-specific antigen, or Charlson comorbidity index (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics of 58 patients with both cultures collected

| Characteristics (N = 58) | FQ-Sensitive Mean (SD) | FQ-Resistant* Mean (SD) | P Value Wilcoxon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 47 | 11 | |

| Age | 64.8 (6.4) | 66.2 (7.8) | .557 |

| BMI | 29.3 (5.1) | 30.1 (8.5) | .827 |

| PSA | 7.51 (8.6) | 6.73 (4.56) | .904 |

| CCI | 1.70 (1.5) | 1.73 (1.8) | .815 |

| Prostate size (cc) | 54.0 (31.4) | 52.6 (40.3) | .601 |

| Days between cultures | 18.6 (16.7) | 24.9 (33.4) | .557 |

| N (%) | N (%) | Fischer’s exact | |

| Race or ethnicity (non-white) | 11 (23%) | 4 (36%) | .299 |

| Diabetes (type II) | 18 (38%) | 1 (9%) | .060 |

| Previous prostate biopsy (0 vs ≥1) | 14 (30%) | 6 (54%) | .116 |

| Active surveillance | 2 (4%) | 2 (18%) | .159 |

| Prostate cancer (yes vs no) | 15 (32%) | 6 (54%) | .176 |

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

FQ-resistant included any culture positive for FQ-resistant organisms on screening or biopsy culture.

The culture taken at biopsy was used as the reference standard. Screening cultures had a sensitivity, specificity, negative, and positive predictive values of 95.9%, 77.8%, 95.9%, and 77.8%, respectively. In addition, the AUC was 0.868. We found no difference in the interval between paired positive and negative cultures, concordant (n = 54) or disconcordant pairs (n = 4) (20 days vs 13 days, P = .410). No clinical infections were identified in any of the patients enrolled, who had a biopsy in the study as determined by a record review done within 30 days of the biopsy.

COMMENT

An increasing trend of infectious complications from TRUSP has been documented most notably FQ-R organisms, in particular E coli.1,4,6,7 Various strategies have been used to counteract the emergence of infectious complications. However, targeted prophylaxis using a screening rectal culture is an emerging concept that provides an individualized prophylaxis regimen.8–10 Two pilot studies regarding the use of targeted prophylaxis before prostate biopsy have been encouraging with 0 infection rates (0 of 347 pooled from both studies).11,12 Although not randomized and underpowered, these pilot studies have raised the awareness of the possible benefit of the routine use of FQ-R rectal screening cultures. Unfortunately, no previous studies have addressed the concern of changing rectal flora or false negative rates.

Horcajada et al17 investigated changes in rectal flora after starting ciprofloxacin for chronic prostatitis and concluded that a previously negative rectal culture for FQ-R E coli might become positive because of unmasking low numbers of FQ-R, exogenous contamination, or conversion of strains to be completely resistant to ciprofloxacin that had been intermediate before taking ciprofloxacin. It is also known that fecal flora can change over time and with age, especially more than the age of 65.18,19

Our results suggest that a screening rectal culture obtained in the office-based setting before prophylaxis corresponds to that cultured in the rectum at biopsy, with 93% of the cultures producing identical results. Importantly, the negative predictive value is >95%, suggesting the chances of a negative culture becoming positive within study time period in 2 of 58 (3%), with a favorable AUC of 0.868.

One caveat of the results is that the two FQ-R Pseudomonas spp. obtained complicated the outcomes as they resulted in discordant cultures. Although the numbers are too low to draw definite conclusions, with the addition of more cases we might find that Pseudomonas spp. might not mirror the concordance in screening cultures seen with E coli. Moreover, we did not culture for gram-positive organisms in this evaluation. Infection with grampositive organisms after prostate biopsy has been reported in 1 of 62 positive cultures (<2%) in symptomatic patients of 3 large international series.6,20,21

We noted a learning curve associated with obtaining rectal cultures with a high rate of inadequate samples (no growth on control agar) encountered early in the study but decreased to 3% after the first 20 patients. Stool must be seen on the culturette and if not, a digital rectal examination might be performed and a sample taken from the gloved finger to improve results. The noninformative result highlights the importance of the control MacConkey agar to notify the physician that the test needs to be repeated. Clinicians interested in incorporating targeted prophylaxis into their practice should consider noninformative rates causing potential retesting and the small but present rate of discordant results in the assessment of the culture and the translation of these results into diverse practice settings. In addition, the cost can be variable depending on location.12,22

Although not a primary outcome of the study, 18% of the patients were colonized with organisms found to have FQ-R and did not have documented infections. The attack rate of the E coli and the bacterial-host factors that cause an infection after TRUSP are currently unknown. However, infection prevention is not the only proposed benefit of targeted prophylaxis. The potential benefit of knowing the FQ-R status of a patient is 3-fold (1) to potentially prevent infection after biopsy, (2) to reduce the use of FQs when they might be futile if that particular patient has a FQ-R organism, and (3) to avoid routine use of broader-spectrum antibiotics selecting for additional resistance and are unnecessary in most patients.

Limitations of the study include the small sample size and the 3-day regimen of ciprofloxacin. The sample size was affected largely because of participants who did not obtain a biopsy for various reasons as documented per study of the flow chart (Fig. 2). The American Urological Association Best Practice Policy Statement on Urologic Surgery and Antimicrobial Prophylaxis lists a recommendation of ≤24 hours of a FQ antibiotic as first line prophylaxis with level 1b evidence.2 Ciprofloxacin will have a peak serum and prostate concentration in 1–3 hours and ideally should be taken 2 hours before biopsy.23,24Weacknowledge the 3-day protocol, as used in this evaluation, is not consistent with the American Urological Association statement and are currently under protocol evaluation to institute change. Owing to the nature of this recommendation being only a best practice and not a guideline recommendation, urologists might still use this regimen.

Our study provides the first data to support the predictive value of the rectal culture screening and potential timing relative to the prostate biopsy. Our major intent was to focus on the reliability of results obtained before the biopsy. This pilot study might be useful to provide information for future studies and analysis. Specific information such as, the sensitivity, specificity, and evidence from clinical trials will further elucidate the potential benefit of targeted prophylaxis.

CONCLUSION

Screening rectal cultures in the office before prostate biopsy predicts colonization of FQ-R organisms with high concordance and favorable test characteristics. This might be used to guide a personalized targeted prophylaxis regimen if obtained a few weeks before prostate biopsy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Hardy Diagnostics for supplying the quality-controlled media and Copan Diagnostics for supplying culturettes.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

References

- 1.Loeb S, Carter HB, Berndt SI, et al. Complications after prostate biopsy: data from SEER-Medicare. J Urol. 2011;186:1830–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf JS, Jr, Bennett CJ, Dmochowski RR, et al. Best practice policy statement on urologic surgery antimicrobial prophylaxis. J Urol. 2008;179:1379–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aron M, Rajeev TP, Gupta NP. Antibiotic prophylaxis for trans-rectal needle biopsy of the prostate: a randomized controlled study. BJU Int. 2000;85:682–685. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nam RK, Saskin R, Lee Y, et al. Increasing hospital admission rates for urological complications after transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2010;183:963–968. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaytoun OM, Vargo EH, Rajan R, et al. Emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli as cause of postprostate biopsy infection: implications for prophylaxis and treatment. Urology. 2011;77:1035–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loeb S, van den Heuvel S, Zhu X, et al. Infectious complications and hospital admissions after prostate biopsy in a European randomized trial. Eur Urol. 2012;61:1110–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feliciano J, Teper E, Ferrandino M, et al. The incidence of fluoroquinolone resistant infections after prostate biopsy—are fluoroquinolones still effective prophylaxis? J Urol. 2008;179:952–955. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.10.071. discussion: 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batura D, Rao GG, Nielsen PB. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in intestinal flora of patients undergoing prostatic biopsy: implications for prophylaxis and treatment of infections after biopsy. BJU Int. 2010;106:1017–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liss MA, Chang A, Santos R, et al. Prevalence and significance of fluoroquinolone resistant Escherichia coli in patients undergoing transrectal ultrasound guided prostate needle biopsy. J Urol. 2011;185:1283–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steensels D, Slabbaert K, De Wever L, et al. Fluoroquinolone-resistant E. coli in intestinal flora of patients undergoing transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy—should we reassess our practices for antibiotic prophylaxis? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:575–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duplessis CA, Bavaro M, Simons MP, et al. Rectal cultures before transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy reduce post-prostatic biopsy infection rates. Urology. 2012;79:556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor AK, Zembower TR, Nadler RB, et al. Targeted antimicrobial prophylaxis using rectal swab cultures in men undergoing transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy is associated with reduced incidence of postoperative infectious complications and cost of care. J Urol. 2012;187:1275–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: 20th Informational Supplement M100-S20. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, NCCLS; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther. 2005;85:257–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obuchowski NA. ROC analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:364–372. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.2.01840364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horcajada JP, Vila J, Moreno-Martinez A, et al. Molecular epidemiology and evolution of resistance to quinolones in Escherichia coli after prolonged administration of ciprofloxacin in patients with prostatitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49:55–59. doi: 10.1093/jac/49.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Claesson MJ, Cusack S, O’Sullivan O, et al. Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(suppl 1):4586–4591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000097107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maslow JN, Lee B, Lautenbach E. Fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli carriage in long-term care facility. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:889–894. doi: 10.3201/eid1106.041335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madden T, Doble A, Aliyu SH, Neal DE. Infective complications after transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy following a new protocol for antibiotic prophylaxis aimed at reducing hospital-acquired infections. BJU Int. 2011;108:1597–1602. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagenlehner FM, van Oostrum E, Tenke P, et al. Infective complications after prostate biopsy: outcome of the Global Prevalence Study of Infections in Urology (GPIU) 2010 and 2011, a prospective multinational multicentre prostate biopsy study. Eur Urol. 2013;63:521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liss MA, Nakamura KK, Peterson EM. Comparison of broth enhancement to direct plating for screening of rectal cultures for ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:249–252. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02158-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis R, Markham A, Balfour JA. Ciprofloxacin. An updated review of its pharmacology, therapeutic efficacy and tolerability. Drugs. 1996;51:1019–1074. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199651060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergan T. Extravascular penetration of ciprofloxacin. A review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;13:103–114. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(90)90093-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]