Abstract

Introduction

We investigated the differences between prostate cancer patients with radiation-induced hematuria treated with hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy that did or did not have a resolution of hematuria.

Materials and Methods

We performed a retrospective review of prostate cancer patients with radiation-induced hematuria who underwent HBO from April 2000 to March 2010. We performed an analysis of demographic data and severity of hematuria in those who had resolution of or persistent hematuria. Additionally, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) data were also obtained during the study period.

Results

Overall, 11/22 men had resolution of hematuria after HBO therapy with a median follow-up of 2.2 (0.35–13.6) years. The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) grade of hematuria is predictive of final hematuria outcome (resolution vs. persistent) after HBO (p = 0.026). No significant PSA changes were noted before and after HBO therapy.

Conclusions

The RTOG hematuria grade is associated with the resolution of hematuria after HBO therapy for radiation-induced hematuria in men treated for prostate cancer. This information may be helpful during shared medical decision-making regarding utility of HBO therapy in the context of severity of hematuria.

Keywords: Hyperbaric oxygen, Radiation cystitis, Hematuria, Prostate-specific antigen

Introduction

External beam radiotherapy is a common treatment in the management of prostate cancer as definitive, postoperative, or salvage local treatment [1]. However, chronic urinary tract complications can occur in 5.7–11.5% of patients treated with radiation therapy, and may occur up to 10 years after initial treatment [2, 3]. Radiation-induced hematuria may occur in 2.6–12.1% of patients; however, hemorrhagic cystitis is a rare event [4–6].

Hypothetically, hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy will cause neovascularization with increased oxygen tension to decrease the friability of blood vessels to potentially resolve the hematuria [7]. Previous studies have evaluated HBO to treat radiation cystitis and to prevent future hematuria; however, the reported efficacy was highly variable [8–10]. Many of the previous studies had limited numbers of patients with severe symptoms (hemorrhagic cystitis), and no studies have previously evaluated changes in prostate-specific antigen (PSA). We investigated variables related to the success of HBO therapy for the treatment of radiation cystitis in prostate cancer patients. Secondarily, we examined PSA changes before and after therapy.

Materials and Methods

After institutional review board approval, we retrospectively reviewed records from the HBO therapy center at Veterans Affairs Long Beach Healthcare System, where patients were treated for radiation cystitis due to prostate cancer therapy from April 2000 to March 2010. Details of the radiation total dose, dose per fraction, and technique were documented.

Patients were diagnosed with radiation cystitis based on gross hematuria and/or compatible findings on cystoscopic examination. Hemorrhagic cystitis was defined as hematuria requiring intraoperative clot evacuation or blood transfusion (>2 U packed red blood cells). Using a modified classification of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) grading criteria for radiation morbidity, a grade was assigned regarding the severity of the hematuria (table 1) [3, 11].

Table 1.

Classification of radiation cystitis severity

| A. Severity of hemorrhagic cystitis | |

| Units transfused within 30 days of HBO | |

| Mild | 0 U |

| Moderate | 1–6 U |

| Severe | >6 U |

| B. Modified RTOG grading system for morbidity | |

| Hematuria | |

| Grade I | Single minor bleeding |

| Grade II | Repeated minor bleeding |

| Grade III | Inpatient medical treatment |

| Grade IV | Inpatient surgical treatment |

| Grade V | Death |

Each patient was planned for 30 sessions and scheduled for only a single session on a given day excluding weekends. Patients received 100% oxygen at a pressure of 2.4 ATA for 90 min per treatment 5 days per week. HBO cure was defined as no gross hematuria documented in the chart after the last HBO treatment was completed. If the patient received a second dose of HBO, this was documented and the cure rate was considered no hematuria after the last dose of HBO.

We retrospectively reviewed PSA (ng/ml) levels from before prostate cancer diagnosis to the most recent PSA in the medical record with particular interest on PSA levels around the time of HBO. As nadir PSA is not well documented, in order to use the Phoenix criteria [12], those with PSA values >2.0 ng/ml were considered to be at the highest risk for progression. PSA values were then compared using the Mann-Whitney test and Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Other statistical analyses consisted of using the Mann-Whitney or Fisher’s exact test for nonparametric and small population size as well as logistic regression for multivariable analysis.

Results

Twenty-two patients were identified from April 17, 2000, with follow-up until March 23, 2010. Pertinent demographics are shown in table 2. Seventy-two percent (13/18) of patients had a known Gleason sum of ≤ 6 and were treated with external beam radiotherapy at a mean dose of 70 Gy (SD = 4 Gy). Patients that received above or below 70 Gy did not have large differences in the need for upper tract diversion (<70 Gy 25%, 1/4, and >70 Gy 30%, 3/10, p = 1.00). Only 64% (14/22) of the patients had adequate information regarding the dose of radiation received and 36% (8/22) had salvage radiation therapy. Most patients (91%, 21/23) presented with RTOG grade III or IV hemorrhagic cystitis (inpatient medical or surgical therapy, respectively) [13].

Table 2.

Patient demographics

| Characteristics | Resolution of hematuria (n = 11) | Persistent hematuria (n = 11) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 75 (59–85) | 75 (54–87) | 0.7421 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.3 (22.8–38.6) | 26.6 (21.7–31.1) | 0.2541 |

| RTOG grade of morbidity from hematuria | 3 (2–4; mean 3.1) | 4 (3–4; mean 3.7) | 0.0261 |

| Number of transfusions, U | 0 (0–5; mean 1.4) | 4 (0–8; mean 3.3) | 0.0621 |

| Smoking history, pack/years | 11 (0–148) | 30 (0–100) | 0.3941 |

| Time from radiation treatment to HBO therapy, years | 4 (1–16) | 3 (1–17) | |

| Follow-up after HBO, years | 1.88 (0.35–13.6) | 3.01 (1.19–10.9) | 0.1781 |

| PSA at biopsy, ng/ml | 7.4 (2–17) | 7.5 (2–54) | |

| Amount of radiation received, cGy | 6,850 (6,600–7,800) | 7,010 (6,600–7,800) | 0.6351 |

| Ethnicity | 0.6702 | ||

| White | 7 (63.6%) | 5 (45.5%) | |

| Black | 4 (36.4%) | 6 (54.5%) | |

| Anticoagulation (Coumadin therapy) | 3 (27.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0.3882 |

| Gleason | 0.5872 | ||

| ≤6 | 7 (63.6%) | 6 (54.5%) | |

| ≥7 | 2 (18.2%) | 3 (27.3%) | |

| Upper tract urinary diversion | 0 | 5 (45%) | 0.0352 |

| Hormonal therapy at time of HBO | 2 (18.2%) | 2 (18.2%) | 1.0002 |

| Timing of radiation | |||

| Primary radiation therapy | 8 (72.7%) | 6 (36.4%) | 0.6942 |

| Adjuvant radiation therapy | 3 (27.3%) | 5 (45.5%) |

Values are expressed as median (range) unless otherwise indicated.

Mann-Whitney test.

Fisher’s exact test.

The absence of hematuria for men after HBO therapy was 50% (11/22). Forty-four percent of patients had resolution of hematuria without recurrence after the first 30-session treatment of HBO, and an additional 3 patients had resolution after a second course of HBO. Five men (23%) needed urinary diversion, 3 of whom needed nephrostomy tubes prior to HBO treatment and 2 patients were diverted due to fistulae.

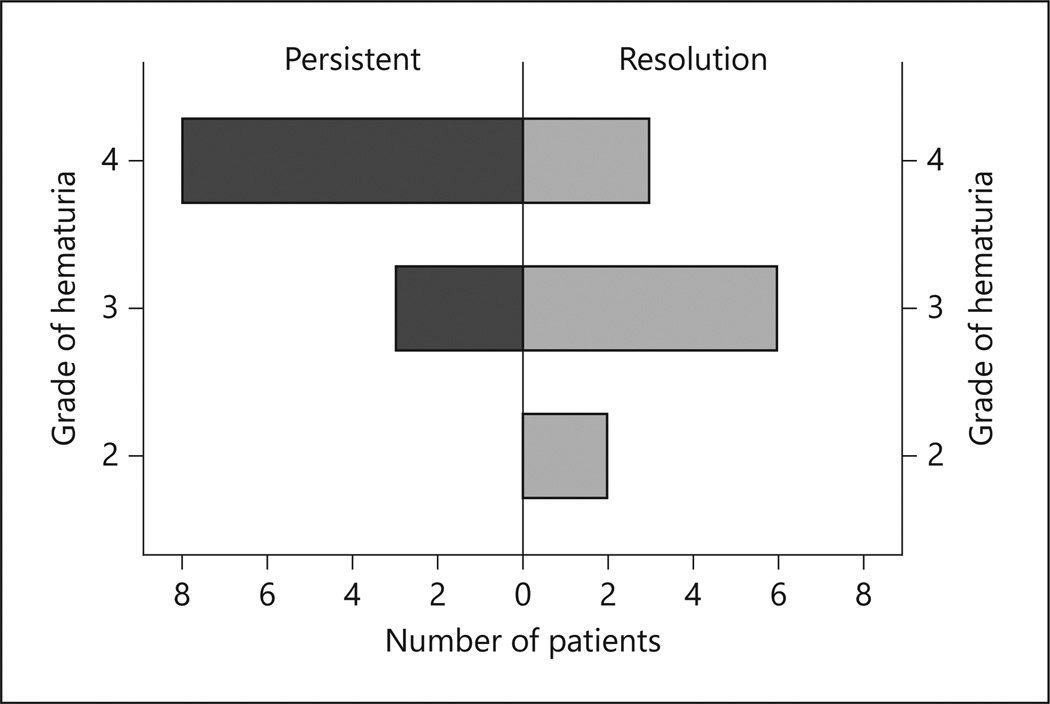

Patients were divided into resolved (n = 11) and persistent (n = 11) after HBO. No difference in age, ethnicity, smoking pack/year, BMI, amount of radiation received, primary or salvage radiation was noted. A significant difference was noted between RTOG grade (I–V) of hematuria and response to HBO therapy (p = 0.026) (figure 1). The median follow-up was 2.2 years (0.35–13.6) with no difference between groups (p = 0.178). We discovered a trend of increased transfusions in the persistent group (3.7 vs. 3.1 U; Mann-Whitney p = 0.062). Only 1 person (4.5%, 1/22) was categorized as having severe hemorrhage (>6 U), and 54.5% (12/22) were moderate (1–6 U) and also did not show to predict HBO response (p = 0.155). In the logistic regression controlling for age, previous prostatectomy, pack/year smoking history, and Gleason grade, a lower RTOG stage of hematuria was associated with resolution of hematuria after HBO (OR 0.175, range 0.031–0.972; p = 0.023).

Fig. 1.

Resolution of hematuria after HBO therapy given the RTOG grade. A population pyramid representing hematuria resolution after HBO therapy for the given RTOG grade of hematuria.

Median PSA for 21 patients with complete data was 0.36 ng/ml (range 0–15.8) prior to HBO therapy (median time prior to therapy 62 days, range 14–467). Following HBO therapy, median PSA was 0.60 ng/ml (range 0–92.5) with a median follow-up time of 127 days (range 38–725). Median change in PSA was 0.20 ng/ml (range 2.8–88; Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.014). To control for subjects with a high risk of progression, we classified the subjects according to pre-diagnosis PSA (≤ 2.0 vs. >2.0), and there was a nonsignificant difference in PSA change between the groups (Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.32). Figure 2 shows PSA (ng/ml) over time with day zero set at the start date of HBO therapy in order to observe PSA per patient over time.

Fig. 2.

PSA of the patient population (n = 20) in relation to time of HBO (time = 0). PSA for each patient with values before and after HBO therapy over time.

Discussion

HBO therapy hypothetically treats radiation-induced cystitis by causing neovascularization and increasing oxygen tension [7]. The resolution after HBO therapy was 50% (11/22) and was associated with the modified RTOG grade of hematuria. If a clot evacuation or diversion (RTOG stage IV) is necessary to treat the hematuria, the chance of resolution of hematuria after HBO therapy is significantly diminished.

HBO therapy has been reported to have excellent response rates; however, the classification that identifies those factors associated with ‘success’ is limited. Corman et al. [8] reported a cure rate of 86% in one of the largest series reported on this topic; unfortunately, the severity of the pre-HBO hematuria was not clearly defined. Hwang and Heath [14] tempered the success rate showing that patients needing a large number of transfusions may not be successfully treated with HBO. They described three groups of patients that responded to HBO therapy: responders, mild hematuria recurrence, and unresponsive. Despite the reservation, they reported a 92.5% success rate with HBO therapy. Other groups also reported very high success rates with HBO for radiation-induced cystitis with varying severity of hematuria [15, 16]. More recent reports demonstrate more guarded results [9]. Our results suggest that HBO may have improved results in patients with milder hematuria and may be less successful in more significant hematuria. These findings can assist physicians in discussing treatment options with the patient and the projected success of HBO therapy.

However, the discussion must include the explanation that the natural history of radiation-induced hematuria is not fully known and hematuria may resolve without any treatment. Estimates of approximately USD 500 per session with the typical 30-session initial series for radiation-induced hematuria up to a cost of USD 20,000 have been projected [8]. Therefore, identifying patients who are less likely to benefit from HBO therapy in order to avoid costly additional therapy is important. Moreover, this highlights a significant gap in practice patterns and evidence-based medicine. Randomized clinical trials incorporating both cost and grade of hematuria are needed to adequately define the utility of HBO in this cohort of patients. The ability to perform such a trial is likely to encounter difficulty with funding and slow accrual for this rare event, nonetheless should be attempted.

Another concern with HBO therapy is the delivery of oxygen to those patients with cancer and the potential for tumor growth. Prostate cancer tumor growth had been a concern due to an animal model experiment finding HBO delivery to LNCaP cells could induce the cell cycle causing cell growth [17]. However, other in vivo mouse models involving LNCaP (indolent) and PC3 (advanced) prostate cancer cell lines showed no increase in tumor growth [18, 19]. In addition, a review article by Feldmeier et al. [11] concluded that most clinical and animal studies showed no cancer growth with HBO exposure. In human clinical evaluation, Daruwalla and Christophi [20] reviewed the HBO effects in various malignancies showing no effect on tumor growth and hypothesizing that the angiogenic activity is more likely induced by hypoxia. According to our evaluation, the PSA did not substantially increase over the course of HBO therapy when evaluating low- and high-progression risk groups.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size and retrospective nature of our study. While the population size is low, the cohort represents a 10-year, purely prostate cancer population treated with radiation therapy with a rare side effect of radiation. The follow-up after HBO also was slightly shorter in those we defined as resolved hematuria, though not statistically significant. This could cause a follow-up bias; however, our IRB was only for chart review, so patients could not be contacted and may have presented outside the Veterans Affairs Healthcare system. Evaluating PSA in patients with previous radiation therapy is exceedingly difficult with the added complexity of intermixed patients receiving hormonal ablation therapy. We included men on androgen deprivation therapy for two reasons: small overall numbers and some men progressing to androgen-independent cancer, which should also be evaluated.

Conclusion

The modified RTOG grading system for morbidity applied to hematuria severity is associated with outcomes of HBO therapy in patients with prostate cancer. HBO did not seem to significantly influence PSA values in patients with prostate cancer treated with external beam radiotherapy. Randomized studies regarding HBO therapy for radiation cystitis are needed.

References

- 1.Jereczek-Fossa BA, Orecchia R. Evidence-based radiation oncology: definitive, adjuvant and salvage radiotherapy for non-metastatic prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2007;84:197–215. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crew JP, Jephcott CR, Reynard JM. Radiation-induced haemorrhagic cystitis. Eur Urol. 2001;40:111–123. doi: 10.1159/000049760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levenback C, Eifel PJ, Burke TW, Morris M, Gershenson DM. Hemorrhagic cystitis following radiotherapy for stage Ib cancer of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;55:206–210. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1994.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greskovich FJ, Zagars GK, Sherman NE, Johnson DE. Complications following external beam radiation therapy for prostate cancer: an analysis of patients treated with and without staging pelvic lymphadenectomy. J Urol. 1991;146:798–802. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37924-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreno JG, Ahlering TE. Late local complications after definitive radiotherapy for prostatic adenocarcinoma. J Urol. 1992;147:926–928. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37424-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawton CA, Won M, Pilepich MV, Asbell SO, Shipley WU, Hanks GE, Cox JD, Perez CA, Sause WT, Doggett SR, et al. Long-term treatment sequelae following external beam irradiation for adenocarcinoma of the prostate: analysis of RTOG studies 7506 and 7706. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:935–939. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90732-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bevers RF, Bakker DJ, Kurth KH. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment for haemorrhagic radiation cystitis. Lancet. 1995;346:803–805. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91620-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corman JM, McClure D, Pritchett R, Kozlowski P, Hampson NB. Treatment of radiation induced hemorrhagic cystitis with hyperbaric oxygen. J Urol. 2003;169:2200–2202. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000063640.41307.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohamad Al-Ali B, Trummer H, Shamloul R, Zigeuner R, Pummer K. Is treatment of hemorrhagic radiation cystitis with hyperbaric oxygen effective? Urol Int. 2010;84:467–470. doi: 10.1159/000296289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norkool DM, Hampson NB, Gibbons RP, Weissman RM. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for radiation-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. J Urol. 1993;150:332–334. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35476-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldmeier JJ, Heimbach RD, Davolt DA, Brakora MJ, Sheffield PJ, Porter AT. Does hyperbaric oxygen have a cancer-causing or -promoting effect? A review of the pertinent literature. Undersea Hyperb Med. 1994;21:467–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roach M, 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H, Jr, Schellhammer P, Shipley WU, Sokol GH, Sandler H. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wessells H, McAninch JW. Urological Emergencies: A Practical Guide. Totowa: Humana Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwang C, Heath EI. Angiogenesis inhibitors in the treatment of prostate cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2010;3:26. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vilar DG, Fadrique GG, Martin IJ, Aguado JM, Perello CG, Argente VG, Sanz MB, Gomez JG. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for the management of hemorrhagic radio-induced cystitis. Arch Esp Urol. 2011;64:869–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathews R, Rajan N, Josefson L, Camporesi E, Makhuli Z. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for radiation induced hemorrhagic cystitis. J Urol. 1999;161:435–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalns JE, Piepmeier EH. Exposure to hyperbaric oxygen induces cell cycle perturbation in prostate cancer cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1999;35:98–101. doi: 10.1007/s11626-999-0008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chong KT, Hampson NB, Bostwick DG, Vessella RL, Corman JM. Hyperbaric oxygen does not accelerate latent in vivo prostate cancer: implications for the treatment of radiation-induced haemorrhagic cystitis. BJU Int. 2004;94:1275–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang H, Zhang ZY, Ge JP, Zhou WQ, Gao JP. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen on tumor growth in the mouse model of lncap prostate cancer cell line (in Chinese) Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2009;15:713–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daruwalla J, Christophi C. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for malignancy: a review. World J Surg. 2006;30:2112–2131. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]