Abstract

The noradrenergic system is involved in the etiology and progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) but its role is still unclear. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) as a catecholamine-synthesizing enzyme plays a central role in noradrenaline (NA) synthesis and turnover. Plasma DBH (pDBH) activity shows wide inheritable interindividual variability that is under genetic control. The aim of this study was to determine pDBH activity, DBH (C-970T; rs1611115) and DBH (C1603T; rs6271) gene polymorphisms in 207 patients with AD and in 90 healthy age-matched controls. Plasma DBH activity was lower, particularly in the early stage of AD, compared to values in middle and late stages of the disease, as well as to control values. Two-way ANOVA revealed significant effect of both diagnosis and DBH (C-970T) or DBH (C1603T) genotypes on pDBH activity, but without significant diagnosis×genotype interaction. No association was found between AD and DBH C-970T (OR=1.08, 95% CI 1.13–4.37; p=0.779) and C1603T (OR=0.89; 95% CI 0.36–2.20; p=0.814) genotypes controlled for age, gender, and ApoE4 allele. The decrease in pDBH activity, found in early phase of AD suggests that alterations in DBH activity represent a compensatory mechanism for the loss of noradrenergic neurons, and that treatment with selective NA reuptake inhibitors may be indicated in early stages of AD to compensate for loss of noradrenergic activity in the locus coeruleus.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Cognitive decline, DBH gene polymorphisms, Dopamine beta-hydroxylase, Plasma DBH activity

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by memory loss and cognitive impairment. Because aging is one of the main risk factors for AD and due to the generalized increase in life expectancy, the prevalence of AD among individuals above 65 years of age is rapidly increasing and AD represents a major public health problem worldwide (Alzheimer’s Association, 2010).

None of the many hypotheses of the etiology of AD has successfully explained all of the features of the disease. AD is a multifactorial disease with a complex interplay of many genetic and environmental factors resulting in a network of interactions that still have to be deciphered. Neuroimaging studies have revealed brain atrophy in the neocortex, hippocampus, and several other brain regions (Cummings, 2004). Dysfunction in cholinergic system was recognized early (Coyle et al., 1983; Giacobini, 2003; Lyness et al., 2003; Wenk, 2003). The loss of serotonergic and noradrenergic nuclei in the brainstem has also been reported in patients with AD (Garcia-Alloza et al., 2005; Herrmann et al., 2004) implying a role for these neurotransmitter systems in the etiology of AD (Lyness et al., 2003).

The noradrenergic system has two main projections, one originating from noradrenergic cells bodies in the ventrolateral tegmental area that is involved in sexual and feeding behaviors, and the other, originating from the locus coeruleus (LC), associated with learning, memory and cognitive functions (Grudzien et al., 2007; Heneka et al., 2010). The loss of noradrenergic neurons from LC correlates with the increase of extracellular amyloid β protein (Aβ) deposition in mice (Heneka et al., 2010), neurofibrillary abnormalities in early stage of AD (Grudzien et al., 2007), onset (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Counts and Mufson, 2010), and duration of dementia (Counts and Mufson, 2010; Forstl et al., 1994). In AD, reduced concentration of noradrenaline (NA) has been reported in many brain regions (Herrmann et al., 2004; Hoogendijk et al., 1999). In addition, increases in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) NA levels (Elrod et al., 1997; Raskind et al., 1999) in AD support the hypothesis that increased noradrenergic activity represents a compensatory mechanism for both cholinergic and noradrenergic deficits (Giubilei et al., 2004; Herrmann et al., 2004). There are several mechanisms providing evidence for the role of NA in AD as not merely a risk factor but as an actual etiological factor (Counts and Mufson, 2010; Fitzgerald, 2010; Weinshenker, 2008). Neuronal plasticity resulting in hyperinnervation of the forebrain regions and noradrenergic sprouting to reinnervate brain regions marked by loss of cholinergic neurons might be mechanisms that account for this compensation (McMillan et al., 2011; Szot et al., 2006). Apart from its role as a neurotransmitter, NA may act as an endogenous anti-inflammatory agent by inhibition of inflammatory activation of microglial cells (Feinstein et al., 2002; Heneka and O’Banion, 2007). Therefore, it has been suggested that cell death in LC and the loss of NA-mediated anti-inflammatory protection could exacerbate inflammation and contribute to the pathogenesis of AD.

The enzyme dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) catalyzes the oxidative hydroxylation of dopamine to NA. DBH is present in noradrenergic neurons in the central nervous system, peripheral postganglionic sympathetic neurons, and adrenal medulla (Kim et al., 2002). It is the only catecholamine-synthesizing enzyme within synaptic vesicles, where it exists in soluble and membrane-bound forms (Lewis and Asnani, 1992). DBH is co-released by exocytosis together with NA and can be found in CSF, plasma, and serum (Weinshilboum et al., 1971). The enzymatic activity of pDBH is characterized by wide interindividual variation regulated by genetic inheritance (Cubells and Zabetian, 2004). The enzymatic activity of DBH corresponds to the plasma level of DBH protein (O’Connor et al., 1994; Weinshilboum et al., 1973), is quite stable, and does not change after physical activity (Cubells and Zabetian, 2004). Single nucleotide polymorphism in the promoter region C-970T of the DBH gene (rs1611115, formerly called C-1021T) accounts for 30 to 50% of the variance in DBH activity, and the T-970 allele contributes to decreased pDBH activity through co-dominant inheritance (Zabetian et al., 2003). The next plausible variant at DBH locus accounting for the variance in pDBH activity, but with considerably less effect is the C1603T polymorphism in intron 11 (Tang et al., 2005; Zabetian et al., 2003).

Although DBH modulates NA levels (Burke et al., 1999; McMillan et al., 2011; Szot et al., 2006) little is known about the effect of DBH activity and/or NA turnover on the development and progression of AD. In patients with AD, reduced DBH activity was found in hippocampus and neocortex postmortem (Cross et al., 1981; Perry et al., 1981). It is possible that the −970T allele and consequently lowered DBH activity in patients with AD could be responsible for the reduced synthesis of NA and loss of its neuroprotective role (Heneka et al., 2010; Mateo et al., 2006; Weinshenker, 2008; Wenk et al., 2003).

Our hypothesis was that pDBH activity could be a biomarker for the development and cognitive dysfunction in AD. Because pDBH activity is genotype-controlled, the aim of the present study was to determine pDBH activity and C-970T and C1603T DBH gene polymorphisms in patients with AD and healthy age-matched control subjects. As so far no study has analyzed the relationship between pDBH activity and cognitive function in patients with AD, we measured pDBH activity in early, middle, and late phases of AD, to elucidate the possible involvement of DBH, and consequently of NA in the progress of AD.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

The present study included 297 unrelated Croatian Caucasian subjects: 207 patients with probable sporadic late onset AD (mean age 80±7.1; range 65–98 years; 185 women), who were recruited from the Psychiatric Clinic Vrapce, Zagreb, Croatia, and a control group of 90 healthy, elderly volunteers (mean age 77.0±7.9; range 60–90 years; 67 women) from local elder living communities. The diagnosis of probable AD was made according to the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and the criteria of the National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINDS–ADRDA) (McKhann et al., 1984). All subjects underwent a clinical interview to rule out for Axis I disorders and to evaluate current and past medical status. Exclusion criteria for patients and controls were the diagnoses of severe somatic diseases (heart disease, epilepsy, brain trauma, cancer), major functional psychiatric disorders (depression, schizophrenia), hypertension, smoking, and alcoholism. Patients were treated with ace-tylcholinesterase inhibitors, and some received antipsychotics, but were medication-free for at least one week before blood sampling. Their cognitive status was evaluated with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975) that was translated and validated to the Croatian population (www.parinc.com; Boban et al., 2012). MMSE scores (expressed as mean±standard deviations) were 28.56±1.94 (range 26–30) and 11.69±8.14 (range 0–24) in controls and in patients with AD, respectively. Patients were additionally subdivided according to the MMSE scores into three groups: 47 patients in the early (20.67±1.3; range 19–24), 80 patients in the middle (14.27±2.1; range 10–18) and 80 patients in the late (1.58±2.4; range 0–9) phases of AD. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the University Psychiatric Hospital Vrapce. All of the patients or their proxies and the healthy controls gave informed consent. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Biochemical and molecular analyses

Blood samples (4 ml) were taken in a plastic syringe with 1 ml of acid citrate dextrose as an anticoagulant. Plasma was obtained after centrifugation of blood at 5000 ×g for 10 min, and stored at −20 °C until assayed using modified method of Nagatsu and Udenfriend (1972). Briefly, DBH converts substrate tyramine to octopamine, which is oxidized to p-hydroxybenzaldehyde, and measured photometrically at 330 nm. The full protocol is available at http://hypertension.ucsd.edu/list_of_protocols/25_DBH_assay.htm.

Genomic DNA was extracted from blood samples using standard salting out procedure (Miller et al., 1988). Genotyping of DBH (C-970T; rs1611115), DBH (C1603T; rs6271), and ApoE (rs7412, rs429358) polymorphisms were performed in ABI Prism 7000 Sequencing Detection System apparatus (ABI, Foster City, CA USA) using a TaqMan-based allele-specific polymerase chain reaction assays, according to the procedure described by Applied Biosystems (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA). The primers and probes were purchased from ABI Assay ID numbers are available upon request.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as means±standard deviations. Differences in pDBH activity among groups were evaluated with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s test. Because the data for pDBH activity were not normally distributed, they were natural logarithm-transformed. Two-way ANOVA was used to test the effect and interaction of diagnosis (AD and healthy controls) and genotype (CC, CT, TT) on plasma DBH activity. The correlation between age and pDBH activity was determined by a Spearman’s coefficient of correlation. The deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, and genotype and allele distributions were performed by the χ2 test. Logistic regression was applied to test the association of AD and DBH (C-970T) and DBH (C1603T) genotypes TT+CT vs. CC, controlled for age, gender, and ApoE4 allele. Power was set to 0.8. The determination of the minimum sample size required to achieve a desired power were evaluated using Sigma Stat 3.5. The statistical packages used were GraphPad Prism and Sigma Stat 3.5 (Jandell Scientific Corp. San Raphael, California, USA). The level of significance was set to α=0.05, with 2-tailed p values.

3. Results

3.1. Plasma DBH activity

One-way ANOVA revealed that pDBH activity did not differ (F=2.103; df=1,88; p=0.151) between healthy women (15.26± 10.9 nmol/ml/min) and men (18.39±10.8 nmol/ml/min) or between women (9.07±5.9 nmol/ml/min) and men (8.21±6.1 nmol/ml/min) with AD (F=1.093; df=1,205; p=0.297). Therefore, in further analyses, the results from both genders were collapsed. Significantly lower pDBH activity was detected in patients with AD (8.98± 5.87 nmol/ml/min) compared to values of pDBH activity in healthy control subjects (16.09±10.9 nmol/ml/min) (F=39.2; df=1,295; p<0.001; power=1.00 with sufficient sample size). No significant correlation (Spearman’s coefficient of correlation) was found between pDBH activity and age in 90 healthy control subjects (r=−0.079; p=0.175) or in 207 patients with AD (r=−0.093; p=0.141).

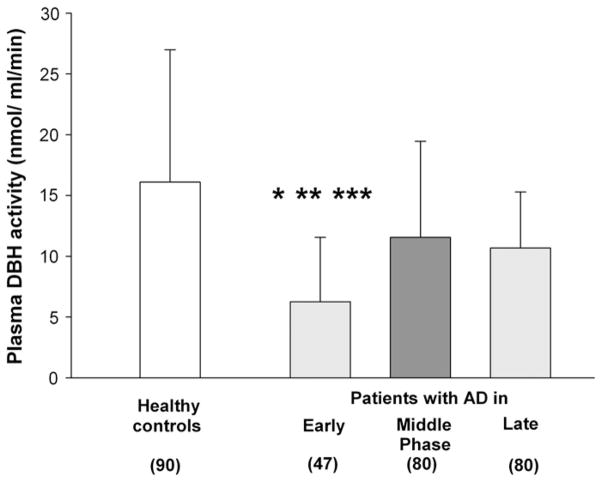

Plasma DBH activity was significantly different (F=10.251; df=3, 294; p<0.001, one-way ANOVA) between patients with early, middle, and late phases of AD and healthy control subjects (Fig. 1). Post-hoc analysis (Tukey’s test) revealed that patients in early phase of AD had lower pDBH activity than patients in middle (p=0.006) or late (p=0.004) phase of AD, or than healthy control subjects (p=0.0001).

Fig. 1.

Plasma DBH activity in patients with different stages of AD (subdivided according to MMSE scores) and in healthy controls. Each column represents mean±SD. *p=0.006 vs. middle stage; **p=0.004 vs. late stage; ***p=0.0001 vs. healthy controls (ANOVA; Tukey’s test).

3.2. DBH gene polymorphisms and plasma DBH activity

No significant deviation from the Hardy–Weinberg distribution was found in DBH (C-970T) genotypes for patients with AD (χ2=0.620; df=1; p=0.431) and healthy control subjects (χ2=0.046; df=1; p=0.829). The distribution of the genotypes of DBH (C1603T) polymorphism did not deviate from the Hardy–Weinberg distribution in patients with AD (χ2=0.533; df=1; p=0.465), while healthy subjects did (χ2=11.970; df=1; p=0.0005).

There was no significant difference in the genotype or CC and T allele (CT+TT) carriers frequencies of the C-970T DBH and of C1603T DBH polymorphism between patients with AD and control subjects (Table 1). The 970T allele was found in 24.2% and 24.4% of patients with AD and healthy control subjects, respectively. The frequency of the 1603T allele was 5.6% in healthy controls and 4.8% in AD patients.

Table 1.

Genotype and allele frequencies of the C-970T and 1603C/T DBH gene polymorphisms and plasma DBH activity, in patients with AD and elderly healthy controls stratified according to genotype.

|

DBH polymorphism

|

Healthy controls (90)

|

AD patients (207)

|

|---|---|---|

| Genotype | N (%) | N (%) |

| C-970T (rs1611115) | ||

| CC | 51 (57) | 117 (56) |

| CT | 34 (38) | 80 (39) |

| TT | 5 (5) χ2=0.080; df=2; p=0.962 |

10 (5) |

| CC homozygotes | 51 (57) | 117 (56) |

| T allele carriers (CT+TT) | 39 (43) χ2=0.011; df=1; p=0.917 |

90 (44) |

| C1603T (rs6271) | ||

| CC | 82 (91) | 187 (90) |

| CT | 6 (7) | 20 (10) |

| TT | 2 (2) χ2=5.240; df=2; p=0.072 |

0 |

| CC homozygotes | 82 (91) | 187 (90) |

| T allele carriers (CT+TT) | 8 (9) χ2=0.000; df=1; p=0.995 |

20 (10) |

N is the number of subjects.

In patients with AD, pDBH activity differed significantly among the carriers of the CC (11.02±5.9 nmol/min/ml), CT (6.71± 4.6 nmol/min/ml), and TT (3.20±3.6 nmol/min/ml) genotypes of the DBH (C-970T) (F =39.452; df=2,204; p <0.001). A significant difference in pDBH was observed between healthy control subjects carriers of CC (20.16±11.3 nmol/min/ml), CT (11.59±7.8 nmol/min/ml), and TT (4.77±1.7 nmol/min/ml) genotypes of the DBH (C-970T) (F= 17.760; df=2,87; p<0.001). This association was manifested in a co-dominant manner. Regarding the other DBH polymorphism, there were no carriers of the TT genotype of the DBH (C1603T) in patients with AD, and therefore, groups were divided into CC and T allele (CT+TT) carriers. Plasma DBH activity did not differ significantly between the CC (9.27±6.0 nmol/min/ml) and T allele (6.22± 3.4 nmol/min/ml) in patients with AD (F =3.85; df=1, 205, p = 0.051) and CC (16.51±11.2 nmol/min/ml) and T allele (11.55± 6.3 nmol/min/ml) healthy control subjects (F =1.48; df=1,88; p <0.227) carriers of the C1603T DBH.

To explore the genetic influence on pDBH activity, further calculations evaluated the effects of DBH C-970T and C1603T polymorphism on pDBH activity. When pDBH activity was stratified according to the C-970T DBH genotype, two-way ANOVA revealed significant effects of both diagnosis (F=25.721; df=1; p<0.001) and genotype (F=48.772; df=2; p<0.001) on pDBH activity, but no significant (F=0.274; df=2; p=0.764) interaction between the diagnosis and genotype. The frequencies of the CC, CT and TT genotypes did not differ significantly (χ2=4.004; df=4; p=0.405) between patients in early (58.3%, 38.9%, 2.8%), middle (52.8%, 38.9%, 8.3%) and late (69.5%, 22.2%, 8.3%) stages of AD, respectively. Logistic regression showed no significant association (OR=1.08; 95% CI 1.13–4.37; p=0.779) between AD and DBH CC homozygotes vs. T allele (CT+TT) carriers, controlled for age, gender, and ApoE4 allele. Two-way ANOVA on effect of C1603T polymorphism and diagnosis revealed significant effect of genotype (F=4.298; df=2; p<0.039), and diagnosis (F=13.240; df=1; p<0.001) on pDBH, but the interaction between them was not statistically significant (F= 0.001; df=2; p=0.969). Logistic regression analysis adjusted for age, gender, and presence of ApoE4 allele was not significant (OR=0.89; 95% CI 0.36–2.20; p=0.814).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare both pDBH activity, DBH gene promoter variant (C-970T), and DBH exon 11 variant (C1603T) in patients with AD and age-matched healthy controls. The most important findings of the present study are the occurrence of genotypes-independent decrease in pDBH activity in patients with AD compared to healthy controls, and the existence of a pronounced decrease in pDBH activity in the early stages of AD compared to values in later stages of AD and values in healthy controls.

Our result of lower pDBH activity in AD compared to healthy subjects is in agreement with decreased plasma (Elrod et al., 1997) and CSF (Elrod et al., 1997; Raskind et al., 1999) NA levels in AD. Although the majority of pDBH protein originates from the peripheral noradrenergic neurons, a good correlation was found between plasma and CSF DBH activity (Lerner et al., 1978; O’Connor et al., 1994). In this respect, our result of altered pDBH activity in patients with AD may be in line with reduced DBH activity in the frontal and temporal cortex and hippocampus (Cross et al., 1981), decreased NA levels (Hoogendijk et al., 1999), and the loss of noradrenergic neurons (Lyness et al., 2003) in postmortem brains of patients with AD. Although there are no data in the literature, we cannot exclude the possibility that the low pDBH activity in patients with AD is a consequence of degeneration of peripheral noradrenergic neurons in AD.

There are several factors such as age, gender, medication, race, and genetic traits that might explain the differences in pDBH activity among patients with AD and healthy control subjects. Although aging is a well-known risk factor for the development of AD, no association was found between pDBH activity in healthy controls in the age up to 60 years (Paclt and Koudelova, 2004), in healthy controls (age range 60 to 90 years) and in patients with AD (age range 65 to 98 years) in the present study.

Gender is also one of the risk factors for the development of AD. The majority (89.4%) of our patients with AD were women, confirming the clinical observations of a higher AD prevalence in women than in men, probably due to the differences in life span between genders. In agreement with the results from previous studies in healthy controls (Arato et al., 1983; Lerner et al., 1978; Ogihara et al., 1975), we have found that pDBH activity in both patients with AD and healthy subjects did not differ according to gender. Although some of our patients received psychotropic medication, the effect of medication on pDBH activity is likely negligible, as it has been reported that treatment with different neuroleptics (haloperidol, chlorpromazine, fluphenazine) in patients with schizophrenia (Baron et al., 1982), and with benzodiazepines and imipramine in patients with depression (Friedman et al., 1984) does not influence pDBH activity. A recent study showed ethnic differences in pDBH activity between African Americans and Americans of European descent (Chen et al., 2010; Tang et al., 2007) the African Americans having lower pDBH activity. However, the potential effect of ethnic differences on pDBH activity can be ignored; our study includes only Caucasians of European (Croatian) origin.

Because neuroinflammation could play an important role in the etiology of AD (Heneka and O’Banion, 2007; Wenk et al., 2003), a possible explanation for the differences in DBH activity between patients with AD and healthy controls may be that inflammatory mediators affect DBH activity (Mateo et al., 2006). Oxidative stress, as one of the consequences of neuroinflammation, produces neurotoxic agents such as reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide that inhibit DBH activity (Zhou et al., 2000). Apart from its role as neurotransmitter, NA can act as an anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective agent, regulating Aβ clearance and microglial Aβ phagocytosis (Heneka and O’Banion, 2007) by activation of neurotrophic pathways that protect against neuronal Aβ toxicity (Counts and Mufson, 2010). Thus, low DBH activity may diminish the probable neuroprotective role of NA, and consequently make individuals with lower DBH activity more susceptible to inflammation and development of AD. Alternatively, a decrease in DBH activity could reflect the neurodegenerative changes in the noradrenergic system, resulting in diminished NA concentration and altered dopamine/NA ratio, with a subsequent compensatory potential as a response to cholinergic deficit (Combarros et al., 2010).

In line with our hypothesis that alterations in DBH activity are an index of the progression of AD, we found lower pDBH activity in the early stages of AD, and a gradual increase in enzyme activity with worsening of cognitive symptoms in the later stages of AD. Our results concur with the low and high NA CSF levels observed in patients with mild/moderate and severe AD, respectively (Elrod et al., 1997). A similar inverse correlation was observed between cognitive decline and DBH immunoreactivity in peripheral lymphocytes (Giubilei et al., 2004).

Owing to the fact that DBH activity is under genetic control (Cubells and Zabetian, 2004; Zabetian et al., 2001), the possible effect of gene polymorphisms influencing the enzyme activity should be taken into account when searching for a potential difference in pDBH activity. Lower plasma DBH activity in our patients with AD than in healthy elderly subjects might be also induced by the individual differences in genetic traits. In agreement with results obtained in ethnically diverse populations like African American (Tang et al., 2005), Indian (Bhaduri and Mukhopadhyay, 2008), and German (Zabetian et al., 2001), our results confirm that the DBH C-970T polymorphism strongly influences plasma DBH activity in Caucasian (Croatian) subjects (Mustapic et al., 2007), with low and high pDBH activity in individuals homozygous for T and C allele of the C-970T DBH, respectively. The relationship between DBH activity and severity of AD in our study could be explained by genetic control of DBH activity. However, no significant differences in the distribution of the particular genotypes between groups of patients in early, middle, and late stage of AD were found. The decline in early and increase of pDBH activity in the later stages of AD could not be attributed to different proportions of less (T allele) or more (C allele) effective enzyme variants.

We have found a deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for C1603T DBH polymorphisms in healthy controls. The possible reason for the significant deviation could be the low frequency of the minor T allele in healthy subjects as suggested by Hosking et al. (2004).

Taking into account the genetic control of DBH activity by the C-970T DBH, we did not confirm our hypothesis that the decrease in plasma (present study) and postmortem brain (Cross et al., 1981) DBH activity in patients with AD is related to a higher frequency of the T allele. Our results do not support the suggestion that noradrenergic deficiency and homozygosis for the T allele of the C-970T DBH might increase the risk for the development of AD (Combarros et al., 2010; Mateo et al., 2006). The reasons for the discrepancies among studies may be related to the different number of patients with AD and healthy subjects, and differences in the geographical origin of subjects, namely Northern Europe and Northern Spain (Combarros et al., 2010) vs. Middle Europe (present study). However, it seems that relationship between T allele and AD depends on gender and age, because a significant association was found only in men younger than 75 years (Combarros et al., 2010). Therefore, the lack of association between the T allele and AD in our study and disagreement with the previous finding (Combarros et al., 2010) could be explained by higher prevalence of women and only 10.6% of men, who were older than 75 years.

Our results enhance the current knowledge of the role of DBH and NA in the etiology of AD (Weinshenker, 2008). Even though tyrosine hydroxylase is considered as a rate-limiting enzyme in catecholamine metabolism there is evidence that under certain conditions DBH can influence NA levels in brain and become rate-limiting (Bourdelat-Parks et al., 2005; Cubells and Zabetian, 2004; McMillan et al., 2011; Schroeder et al., 2010). These findings confirm the presumption that initial loss of noradrenergic neurons from the LC is compensated by the increased activity of the surviving neurons (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Hoogendijk et al., 1999; Szot et al., 2006). Several compensatory mechanisms have been described (Counts and Mufson, 2010: Fitzgerald, 2010; Szot et al., 2006; Weinshenker, 2008), including stimulation of NA synthesis due to the increased expression of TH (Szot et al., 2006), decreased clearance of NA from the presynaptic terminals (Raskind et al., 1999), impaired NA turnover (Counts and Mufson, 2010; Fitzgerald, 2010; Weinshenker, 2008), and increased sprouting of the surviving noradrenergic neurons originating from LC (Szot et al., 2006). The determination of NA and its metabolite 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG) revealed a high MHPG/NA ratio in frontal cortex and LC in AD (Hoogendijk et al., 1999), suggesting that increase in NA metabolism in remaining noradrenergic neurons could be also a potential compensatory mechanism for the loss of noradrenergic neurons. The increase in DBH activity and NA levels, calculated per neurons was also reported postmortem in AD cases compared to controls (Burke et al., 1999). Conversely, McMillan et al. (2011) recently observed an overall decrease in DBH mRNA in LC neurons of AD patients measured postmortem, but the amount of DBH mRNA expression/neuron in AD subjects was not significantly different from that in controls. The lack of significant difference in mRNA DBH expression per neuron between AD subjects and controls (McMillan et al., 2011) is possibly revealing a compensatory effect as increased pDBH activity in a later stage, almost reaching the values of pDBH activity in healthy controls (Fig. 1) as opposed to low pDBH activity in early stage patients, who may have decreased DBH mRNA expression.

A limitation of the present study is the sample size particularly of the control subjects. The number of healthy control subjects was limited due to exclusion criteria like the presence of somatic diseases that are often present in elderly subjects. Another limitation is the measurement of peripheral pDBH activity at one time point, without individual longitudinal follow-up of pDBH activity during the progress of AD. In addition, cognitive decline in AD was determined using MMSE but not with other clinical scales, such as Clinical Dementia Rating Scores. The advantages of the study however are the determination of three bio-markers: pDBH activity and C-970T and C1603T DBH polymorphisms in patients with different stages of AD, the inclusion of the gender- and age-matched healthy controls, the power (0.8), and a sufficiently large sample size to determine the differences in pDBH activity.

In conclusion, our results show genotypes-independent decrease in pDBH activity in patients with AD compared to enzyme activity in age-matched healthy controls. We did not confirm the association of low activity T allele variant of the DBH C-970T and AD. Despite the limitations of the study and the questionable significance of the alteration in peripheral pDBH activity and the central noradrenergic activity, the relationship between pDBH activity and severity of AD suggests that initial loss of noradrenergic neurons in the LC in AD could be compensated by increased activity and production of NA in surviving neurons. This finding indicates that in early phase of AD, treatment with drugs such as selective NA reuptake inhibitors is warranted for compensation of the loss of noradrenergic activity in LC. Further studies are necessary to confirm that altered DBH activity represents a compensatory mechanism for the loss of noradrenergic neurons in the early stages of AD.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by Croatian Ministry of Science, Education and Sports (grant nos. 098-0982522-2457, 098-0982522-2455 and 108-1081870-2418), Croatian Science Foundation grant no. 09/16, as well as COST Action CM1103. Thanks are due to the staff of University Psychiatric Hospital Vrapce and Psychiatric Hospital Sv. Ivan, Zagreb, Croatia.

Abbreviations

- Aβ

amyloid β protein

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ANOVA

one-way analysis of variance

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- DBH

dopamine beta-hydroxylase

- DBH

dopamine beta-hydroxylase gene

- LC

locus coeruleus

- MHPG

3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- NA

noradrenaline

- pDBH

plasma dopamine beta-hydroxylase

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2010 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6:158–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arato M, Bagdy G, Blumel F, Perenyi A, Rihmer Z. Reduced serum dopamine-beta-hydroxylase activity in paranoid schizophrenics. Pharmacopsychiatria. 1983;16:19–22. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1017442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron M, Gruen R, Levitt M, Kane J. Neuroleptic drug effect on plasma dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in schizophrenia. Neuropsychobiology. 1982;8:312–4. doi: 10.1159/000117917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaduri N, Mukhopadhyay K. Correlation of plasma dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity with polymorphisms in DBH gene: a study on Eastern Indian population. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2008;28:343–50. doi: 10.1007/s10571-007-9256-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boban M, Malojcic B, Mimica N, Vukovic S, Zrilic I, Hof PR, et al. The reliability and validity of the Mini-Mental State Examination in the elderly Croatian population. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;33:385–92. doi: 10.1159/000339596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdelat-Parks BN, Anderson GM, Donaldson ZR, Weiss JM, Bonsall RW, Emery MS, et al. Effects of dopamine beta-hydroxylase genotype and disulfiram inhibition on cate-cholamine homeostasis in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;183:72–80. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke WJ, Li SW, Schmitt CA, Xia P, Chung HD, Gillespie KN. Accumulation of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycolaldehyde, the neurotoxic monoamine oxidase A metabolite of norepinephrine, in locus ceruleus cell bodies in Alzheimer’s disease: mechanism of neuron death. Brain Res. 1999;816:633–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Wen G, Rao F, Zhang K, Wang L, Rodriguez-Flores JL, et al. Human dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) regulatory polymorphism that influences enzymatic activity, autonomic function, and blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2010;28:76–86. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328332bc87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combarros O, Warden DR, Hammond N, Cortina-Borja M, Belbin O, Lehmann MG, et al. The dopamine beta-hydroxylase −1021C/T polymorphism is associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in the Epistasis Project. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counts SE, Mufson EJ. Noradrenaline activation of neurotrophic pathways protects against neuronal amyloid toxicity. J Neurochem. 2010;113:649–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Price DL, DeLong MR. Alzheimer’s disease: a disorder of cortical cholinergic innervation. Science. 1983;219:1184–90. doi: 10.1126/science.6338589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross AJ, Crow TJ, Perry EK, Perry RH, Blessed G, Tomlinson BE. Reduced dopamine-beta-hydroxylase activity in Alzheimer’s disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981;282:93–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6258.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubells JF, Zabetian CP. Human genetics of plasma dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity: applications to research in psychiatry and neurology. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:463–76. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1840-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:56–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod R, Peskind ER, DiGiacomo L, Brodkin KI, Veith RC, Raskind MA. Effects of Alzheimer’s disease severity on cerebrospinal fluid norepinephrine concentration. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:25–30. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein DL, Heneka MT, Gavrilyuk V, Dello Russo C, Weinberg G, Galea E. Noradrenergic regulation of inflammatory gene expression in brain. Neurochem Int. 2002;41:357–65. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald PJ. Is elevated norepinephrine an etiological factor in some cases of Alzheimer’s disease? Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:506–16. doi: 10.2174/156720510792231775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstl H, Levy R, Burns A, Luthert P, Cairns N. Disproportionate loss of noradrenergic and cholinergic neurons as cause of depression in Alzheimer’s disease — a hypothesis. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1994;27:11–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MJ, Stolk JM, Harris PQ, Cooper TB. Serum dopamine-beta-hydroxylase activity in depression and anxiety. Biol Psychiatry. 1984;19:557–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Alloza M, Gil-Bea FJ, Diez-Ariza M, Chen CP, Francis PT, Lasheras B, et al. Cholinergic–serotonergic imbalance contributes to cognitive and behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:442–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacobini E. Cholinergic function and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:S1–5. doi: 10.1002/gps.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giubilei F, Calderaro C, Antonini G, Sepe-Monti M, Tisei P, Brunetti E, et al. Increased lymphocyte dopamine beta-hydroxylase immunoreactivity in Alzheimer’s disease: compensatory response to cholinergic deficit? Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18:338–41. doi: 10.1159/000080128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudzien A, Shaw P, Weintraub S, Bigio E, Mash DC, Mesulam MM. Locus coeruleus neurofibrillary degeneration in aging, mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:327–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, O’Banion MK. Inflammatory processes in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;184:69–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Nadrigny F, Regen T, Martinez-Hernandez A, Dumitrescu-Ozimek L, Terwel D, et al. Locus ceruleus controls Alzheimer’s disease pathology by modulating microglial functions through norepinephrine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6058–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909586107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann N, Lanctot KL, Khan LR. The role of norepinephrine in the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16:261–76. doi: 10.1176/jnp.16.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogendijk WJ, Feenstra MG, Botterblom MH, Gilhuis J, Sommer IE, Kamphorst W, et al. Increased activity of surviving locus ceruleus neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:82–91. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199901)45:1<82::aid-art14>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking L, Lumsden S, Lewis K, Yeo A, McCarthy L, Bansal A, et al. Detection of genotyping errors by Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium testing. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:395–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Zabetian CP, Cubells JF, Cho S, Biaggioni I, Cohen BM, et al. Mutations in the dopamine beta-hydroxylase gene are associated with human norepinephrine deficiency. Am J Med Genet. 2002;108:140–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner P, Goodwin FK, van Kammen DP, Post RM, Major LF, Ballenger JC, et al. Dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in the cerebrospinal fluid of psychiatric patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1978;13:685–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis EJ, Asnani LP. Soluble and membrane-bound forms of dopamine beta-hydroxylase are encoded by the same mRNA. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:494–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyness SA, Zarow C, Chui HC. Neuron loss in key cholinergic and aminergic nuclei in Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo I, Infante J, Rodriguez E, Berciano J, Combarros O, Llorca J. Interaction between dopamine beta-hydroxylase and interleukin genes increases Alzheimer’s disease risk. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:278–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.075358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS–ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan PJ, White SS, Franklin A, Greenup JL, Leverenz JB, Raskind MA, et al. Differential response of the central noradrenergic nervous system to the loss of locus coeruleus neurons in Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2011;1373:240–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustapic M, Pivac N, Kozaric-Kovacic D, Dezeljin M, Cubells JF, Muck-Seler D. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) activity and −1021C/T polymorphism of DBH gene in combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:1087–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatsu T, Udenfriend S. Photometric assay of dopamine-hydroxylase activity in human blood. Clin Chem. 1972;18:980–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor DT, Cervenka JH, Stone RA, Levine GL, Parmer RJ, Franco-Bourland RE, et al. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase immunoreactivity in human cerebrospinal fluid: properties, relationship to central noradrenergic neuronal activity and variation in Parkinson’s disease and congenital dopamine beta-hydroxylase deficiency. Clin Sci (Lond) 1994;86:149–58. doi: 10.1042/cs0860149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogihara T, Nugent CA, Shen SW, Goldfein S. Serum dopamine-beta-hydroxylase activity in parents and children. J Lab Clin Med. 1975;85:566–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paclt I, Koudelova J. Changes of dopamine-beta-hydroxylase activity during ontogenesis in healthy subjects and in an experimental model (rats) Physiol Res. 2004;53:661–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry EK, Tomlinson BE, Blessed G, Perry RH, Cross AJ, Crow TJ. Neuropathological and biochemical observations on the noradrenergic system in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 1981;51:279–87. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(81)90106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Holmes C, Goldstein DS. Patterns of cerebrospinal fluid catechols support increased central noradrenergic responsiveness in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:756–65. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JP, Cooper DA, Schank JR, Lyle MA, Gaval-Cruz M, Ogbonmwan YE, et al. Di-sulfiram attenuates drug-primed reinstatement of cocaine seeking via inhibition of dopamine beta-hydroxylase. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2440–9. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szot P, White SS, Greenup JL, Leverenz JB, Peskind ER, Raskind MA. Compensatory changes in the noradrenergic nervous system in the locus ceruleus and hippocampus of postmortem subjects with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurosci. 2006;26:467–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4265-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Anderson GM, Zabetian CP, Kohnke MD, Cubells JF. Haplotype-controlled analysis of the association of a non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism at DBH (+1603C→T) with plasma dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;139B:88–90. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YL, Epstein MP, Anderson GM, Zabetian CP, Cubells JF. Genotypic and haplotypic associations of the DBH gene with plasma dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity in African Americans. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:878–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshenker D. Functional consequences of locus coeruleus degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5:342–5. doi: 10.2174/156720508784533286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshilboum RM, Thoa NB, Johnson DG, Kopin IJ, Axelrod J. Proportional release of norepinephrine and dopamine-hydroxylase from sympathetic nerves. Science. 1971;174:1349–51. doi: 10.1126/science.174.4016.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshilboum RM, Raymond FA, Elveback LR, Weidman WH. Serum dopamine-beta-hydroxylase activity: sibling–sibling correlation. Science. 1973;181:943–5. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4103.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk GL. Neuropathologic changes in Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 9):7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk GL, McGann K, Hauss-Wegrzyniak B, Rosi S. The toxicity of tumor necrosis factor-alpha upon cholinergic neurons within the nucleus basalis and the role of norepinephrine in the regulation of inflammation: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2003;121:719–29. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabetian CP, Anderson GM, Buxbaum SG, Elston RC, Ichinose H, Nagatsu T, et al. A quantitative-trait analysis of human plasma-dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity: evidence for a major functional polymorphism at the DBH locus. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:515–22. doi: 10.1086/318198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabetian CP, Buxbaum SG, Elston RC, Kohnke MD, Anderson GM, Gelernter J, et al. The structure of linkage disequilibrium at the DBH locus strongly influences the magnitude of association between diallelic markers and plasma dopamine beta-hydroxylase activity. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1389–400. doi: 10.1086/375499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Espey MG, Chen JX, Hofseth LJ, Miranda KM, Hussain SP, et al. Inhibitory effects of nitric oxide and nitrosative stress on dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21241–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M904498199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]