Abstract

The latest findings on the role played by human LDH5 (hLDH5) in the promotion of glycolysis in invasive tumor cells indicates that this enzyme subtype is a promising therapeutic target for invasive cancer. Compounds able to selectively inhibit hLDH5 hold promise for the cure of neoplastic diseases. hLDH5 has so far been a rather unexplored target, since its importance in the promotion of cancer progression has been neglected for decades. This enzyme should also be considered as a challenging target due the high polar character (mostly cationic) of its ligand cavity. Recently, significant progresses have been reached with small-molecule inhibitors of hLDH5 displaying remarkable potencies and selectivities. This review provides an overview of the newly developed hLDH5 inhibitors. The roles of hLDH isoforms will be briefly discussed, and then the inhibitors will be grouped into chemical classes. Furthermore, general pharmacophore features will be emphasized throughout the structural subgroups analyzed.

Cancer cell metabolism & the Warburg effect

Normal healthy cells usually rely on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to produce energy, unlike cancer cells that preferentially exploit glycolysis. The shift from OXPHOS toward glycolysis represents one of the main hallmarks of tumors. This key change is accompanied by a high glucose uptake, due to the lower energetic efficiency of glycolysis compared with OXPHOS, as well as by extracellular acidosis, since elevated levels of lactate are produced [1,2].

The glycolytic abnormal metabolism is a common feature of tumor cells and is usually known as the Warburg effect. This name originates from the scientist Otto Warburg, who first observed this phenomenon. Warburg realized that tumor cells rely on glycolysis even in the presence of sufficient oxygen to support mitochondrial OXPHOS (‘aerobic glycolysis’), and he also understood the relationship between the peculiar glycolytic metabolism and cancer [3]. Initially, Warburg ascribed this metabolic alteration to a defective mitochondrial function, but now it has been established that this metabolism is adopted to satisfy the enhanced requirements for energy and anabolites needed by cancer cells [4]. In fact, the glycolytic metabolic alteration is highly functional for rapidly growing cells such as tumor cells: it ensures an adequate and rapid supply of energy and biosynthetic intermediates starting from glucose, thus allowing survival even in hypoxic regions of cancer tissues, where the oxygen requirement for OXPHOS cannot be satisfied. The glycolytic pathway is much less efficient than OXPHOS in producing energy: for each glucose molecule two molecules of ATP are produced versus the ~36 ATP units usually produced in the OXPHOS process. However, the generation of ATP through glycolysis is more rapid and this offers a selective advantage to proliferating tumor cells. In this context HIF-1, a heterodimeric transcription factor, regulates cellular adaptation to hypoxia by inducing the transcription of several proteins that help tumors to grow in a hypoxic environment [5], including lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; enzyme commission number: 1.1.1.27). This enzyme catalyzes the reduction of pyruvate to lactate at the end of the glycolytic process (lactate fermentation), which is coupled to the oxidation of cofactor NADH to NAD+ [6].

In healthy cells, glucose is metabolized to pyruvate by glycolysis, which is then coupled to OXPHOS so that the end-product of glycolysis (pyruvate) can be further oxidized in mitochondria to produce ATP and CO2. In hypoxic conditions, OXPHOS is not active due to the absence of sufficient levels of oxygen, which is the final electron acceptor in the electron transport chain; hence. pyruvate must be converted to lactate by LDH to allow the continuation of glycolysis. In fact, the oxidized cofactor NAD+, which is produced in the LDH-catalyzed reaction, is required by glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehyde- 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (which promotes the conversion of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate to 1,3-biphosphoglycerate), and is necessary for the regular continuation of glycolysis when OXPHOS in mitochondria is not active. Therefore, it is evident that LDH covers a central position in the metabolic reprogramming of tumor cells, playing a key role in the maintenance of altered glycolytic metabolism and permitting survival of tumor cells when glycolysis represents the only energetic source.

hLDH5: a promising antiglycolytic target

LDH is a tetrameric enzyme composed of two different kinds of subunits: M (mainly present in skeletal muscle and liver) and H (found in the heart, spleen, kidney, brain and erythrocytes). The tetrameric association of these two subunits can generate five isoforms. Two of the resulting isoforms are homotetramers – LDH-1 (H4) and LDH-5 (M4), which are also simply called LDH-H and LDH-M respectively, whereas three are hybrid tetramers, – LDH-2 (M1H3), LDH-3 (M2H2) and LDH-4 (M3H1). Subunits M and H are encoded by two specific genes, LDH-A and LDH-B, respectively; therefore, the five isozymes are also named LDH-B4, or simply LDH-B (H4), LDH-A1B3 (M1H3), LDH-A2B2 (M2H2), LDH-A3B1 (M3H1) and LDH-A4 or LDH-A (M4). The finding of a sixth isoform in mature human testis and sperm indicated the presence of an additional LDH subunit, called LDH-X or LDH-C4, and this last isoform seems to play a role in male fertility.

Human LDH-5 (hLDH5) has the highest activity in converting pyruvate to lactate under anaerobic conditions, such as those often found in skeletal muscle and hypoxic tumors, whereas human LDH-1 (hLDH1) is more efficient in the catalysis of the reverse reaction from lactate to pyruvate, which predominantly occurs in the heart and in other well-oxygenated tissues. hLDH5 expression, which is mainly regulated by HIF-1 and Myc (an oncogene encoding for a transcription factor, which leads to the expression of proteins involved in cell proliferation) [7], is strictly correlated with poor prognosis and aggressive phenotypes in several kinds of tumors. As a matter of fact, it has been established that hLDH5 may play an important role in the development and maintenance of metastatic tumors, and serum hLDH5 levels have been correlated with resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy [8,9]. Further evidence linking hLDH5 increase to aggressive tumor phenotypes comes from the observation that the increased lactate production caused by hLDH5 contributes to the development of extracellular acidosis, and the low pH represents a factor that finally facilitates tumor invasion and metastasis [10]. hLDH5 was found to be overexpressed in a wide range of tumors, where it is now considered as a useful prognostic factor, such as oral squamous cell carcinoma [11], gastric cancer [12], non-small-cell lung cancer [13,14], colorectal cancer [15], endometrial cancer tissues [16], non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas [17], melanoma [18], squamous head and neck cancer [19] and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [20]. Upregulation of hLDH5 confers a growth advantage, ensuring energy supply to highly glycolytic cancer cells, whereas this enzyme is not fundamental for healthy cells that normally rely on OXPHOS.

Recently, it has been observed that hLDH5 is subjected to post-transcriptional regulation by acetylation at lysine 5, which leads to a decrease of the enzymatic activity. In fact, once the acetylated protein is recognized by the HSC70 chaperone, it is delivered to lysosomes for degradation. On the contrary, Lys5 acetylation of this enzyme was found to be significantly reduced in human pancreatic cancer specimens, thus promoting a higher hLDH5 activity in these tissues. This effect seems to be supported by a higher activity of SIRT2 deacetylase in the tumor cells [21]. Differently, hLDH1 is often downregulated in cancer cells when compared with normal tissues [22]. Studies performed in prostate cancer demonstrated that silencing of the LDH-H subunit is due to hypermethylation of the LDH-B gene promoter [23]. However, hLDH1 is not merely a silent isoform in cancers, it seems to be involved in the cell–cell shuttle system, also known as the ‘lactate shuttle’ [24]. This phenomenon can be explained considering that the cell population of tumors is highly heterogeneous and can be divided into two main types: the cells near the blood vessels that have an oxidative metabolism thanks to the high oxygen levels, and those far from the vasculature that are hypoxic and glycolytic. These two cell populations establish a symbiosis by means of lactate, which can be shuttled through monocarboxylate transporters in the tumor microenvironment, as it usually happens in active skeletal muscle and the brain. In particular, glucose uptake through the GLUT transporter takes place into less oxygenated cells, because it is necessary to fuel glycolysis, and finally hLDH5 catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate to lactate, which is then extruded by monocarboxylate transporter 4 in the extracellular compartment. Later, lactate is internalized into ‘oxidative’ cells by monocarboxylate transporter 1, where it is used as an oxidizable substrate and converted to pyruvate by hLDH1. In these cells, pyruvate can then be metabolized in the Krebs cycle, producing ATP and CO2. Unfortunately, it is not completely clear, as of yet, whether hLDH1 inhibition could have positive consequences against cancer and, therefore, there is no evident interest in the search for selective hLDH1 inhibitors. The strong dependency of tumor cells on glucose metabolism and the overexpression of hLDH5 may constitute a weak point of hypoxic invasive cancers that could be therapeutically exploited by interfering with the hLDH5 activity.

Silencing of hLDH5 expression by means of shRNA represents a well-established proof of the essential role of this enzyme in the metabolism of cancer cells [25,26]. These studies demonstrated that when hLDH5 levels were genetically knocked down in tumor cell lines characterized by high glucose dependency and high LDH-A expression, under both normal and hypoxic conditions, the ability of those tumors to grow was severely compromised, and their OXPHOS activity and oxygen consumption were stimulated. In particular, when the oxygen pressure is limited, the effect is even more pronounced, because the proliferation was completely blocked and ATP levels were much lower. Altogether, these data suggest that hLDH5 plays a fundamental role in tumor maintenance, because cancer cells rely on hLDH5 activity for energy production even when oxygen is not a limiting factor. For these reasons, hLDH5 is now being considered as a very promising therapeutic target for the treatment of cancer. In the following years this concept was further confirmed by additional in vivo and in vitro experiments, which proved that genetic silencing of hLDH5 [27,28] or its inhibition by small molecules [29] decreased the tumorigenicity of many cancers, increased oxidative stress and induced apoptosis leading to cell death. Experimental evidences demonstrated that suppression of the LDH-A gene led to an increase of HIF1α in HT29 colon cells, hence influencing the adaptation of those cells to a hypoxic tumor microenvironment [30]. Moreover, promising results were obtained in in vivo studies: hLDH5 knockdown in the background of fumarate hydratase (an enzyme belonging to the Krebs cycle)-deficient cells caused a decrease of tumor growth in a xenograft mouse model of renal cancer [31], and this result was later confirmed in hepatocellular carcinoma, where hLDH5 suppression reduced the metastatic potential in a xenograft mouse model [32].

The lack of significant side effects deriving from hLDH5 inhibition might be expected considering that people with a hereditary deficiency of the LDH-A gene, who consequently completely lack the A subunit, show myoglobinuria (the presence of myoglobin in the urine caused by muscle damage) after intense anaerobic exercise (exertional myoglobinuria), whereas they do not display any symptoms under ordinary circumstances [33–35]. Therefore, selective hLDH5 inhibition can be considered as a potentially safe target. Unlike other glycolytic enzymes, for which some drug candidates have been found so far [36,37], only a few selective hLDH5 inhibitors have been developed as of yet, and none of them has hitherto demonstrated any real clinical benefit. This is probably due to the fact that very few clinical applications had been previously associated with hLDH5 inhibition, and there was no evidence that this enzyme could represent an effective target for the treatment of cancer, until the above mentioned discoveries of the link between hLDH5 and the Warburg effect [25,26]. Most of the inhibitors present in literature were developed against the Plasmodium falciparum LDH isoform (pf LDH). In fact, it is well known that pf LDH is a key enzyme for the survival of the malarial parasite, and many molecules were designed and synthesized against this antimalarial target [38]. These compounds illustrated very poor inhibitory activities on the human isoform 5, although these data were originally reported only as undesired side effects, which were caused by the similarity of the dehydrogenases hLDH5 and pf LDH. Some of these first inhibitors demonstrated some structural features in common: in particular the presence of carboxylates, usually present in a position near to a hydroxyl or a carbonyl oxygen atom. This could be explained by considering the structures of the original substrates of LDH, which are lactate (an α-hydroxyacid) or pyruvate (an α-ketoacid). As a consequence, the LDH active site is very polar and rich in arginine residues (highly cationic). Besides the direct anticancer effects associated with inhibition of hLDH5, the ATP depletion provoked by hLDH5 inhibition seems to enhance the effects of kinase inhibitors, such as sorafenib, imatinib and sunitinib, without impairing the regular metabolism of healthy cells, which do not rely on LDH activity for their survival in normal conditions [39]. This effect finds its explanation by considering that after reducing the ATP levels, the competition for the ATP binding site in kinase enzymes becomes less difficult for the above-mentioned kinase inhibitors.

Gossypol & derivatives

Among the few LDH inhibitors reported in the literature, some already known natural polyphenolic flavone derivatives (such as morin) were patented for their potential application as anticancer agents due to their reported inhibition of hLDH5 [201], but they were not further developed.

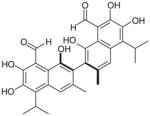

Among other natural compounds, polyphenolic binaphthyl disesquiterpene aldehyde derivative gossypol (1; Table 1) is a well-known nonselective LDH inhibitor. Gossypol is usually found in high concentrations in the pigment glands of the cotton plant. Hence its name derives from Gossypium, the plant from which it was originally isolated, but it was subsequently found in several other closely related genera belonging to the Malvaceae family [40]. Together, with other sesquiterpenoids detected in these plants, gossypol exerts the function of a natural insecticide, defending the plant from attacks of several kinds of pathogens and insects [41]. It exists as two enantiomers generated by the restricted rotation around the carbon 2–2′ single bond linking the two naphthalene units (atropisomerism). Some studies seem to suggest a dependence of the activity of gossypol from its chirality, reporting a dose-dependent cytotoxic action of (R)-(–)-gossypol on a series of cancer cell lines such as melanoma, lung, breast, cervix and leukemia cell cultures with a mean IC50 of 20 μM, whereas the (S)-(+) enantiomer is not so potent [42]. Despite this marked diversity, most of the biological activities of gossypol reported in literature were ascribed to atropisomeric mixtures. The initial pharmacological interest toward this compound rose from its male antifertility action thanks to its spermicidal activity [43]. Since this discovery, further promising biological properties of gossypol have been extensively studied, such as antitumor, antioxidant, antiviral and antiparasitic activities, revealing the broad spectrum of action of gossypol [44]. In particular, gossypol has reported good cytotoxic in vitro activities in a range of human tumor cell lines, such as melanoma and colon carcinoma, being toxic at a concentration of approximately 5 μM, as well as in human glioma cell lines and adrenocortical carcinoma [45–47]. The favored targets of gossypol are dehydrogenase enzymes, in particular LDH; in fact, its antifertility action has been attributed to inhibition of the isoform LDH-C4 [48], its antitumor activity may result from its action on hLDH5, and its antimalarial activity is caused by the inhibition of pf LDH.

Table 1.

Gossypol: inhibition data on plasmodial and hLDH5 isoforms.

Gossypol nonselectively inhibits both hLDH5 and hLDH1, being competitive with the enzyme cofactor NADH, with reported Ki values of 1.9 and 1.4 μM, respectively (Table 1), while it demonstrated a certain preference for pf LDH (Ki of 0.7 μM) [49]. It was reported to be a less potent inhibitor of the testis-specific human isoform LDH-C4, with a Ki value of 4.2 μM [50]. Moreover, gossypol inhibits other NADH/NAD+-dependent dehydrogenases, such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, an enzyme that, similarly to LDH, belongs to the glycolytic pathway [51].

Unfortunately, gossypol can chelate metal ions and possesses a highly reactive chemical structure, due to the two aldehyde groups, which are able to form Schiff bases with amino groups of proteins, and to the catechol hydroxyls, which are highly sensitive towards oxidation that generates toxic o-quinone-type metabolites. These structural characteristics of gossypol result in a highly unspecific toxicity in biological systems, mostly consisting of side effects such as cardiac arrhythmias, hypokalemia, renal failure, muscle weakness and sometimes even paralysis [52–54]. Because of its chemical nature, gossypol can interact with several cellular components in a variety of ways, influencing many cellular function, such as macromolecule synthesis, ion transport, membrane properties, calcium homeostasis, OXPHOS and glucose uptake [55]. The above-mentioned toxicity of this natural compound makes it a very difficult anticancer candidate to be developed. Therefore, many gossypol analogues were designed with the aim of maintaining its biological activities without its toxic side effects. These derivatives have chemical structures closely related to gossypol, but they generally lack the aldehyde functionality, which is responsible for most of its toxicity, or possess functional groups that replace or modify both aldehyde and phenolic groups.

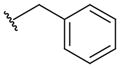

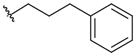

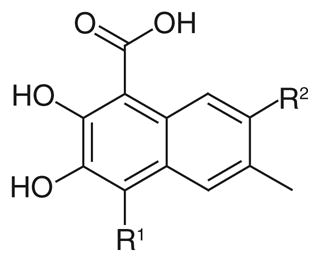

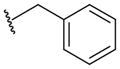

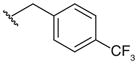

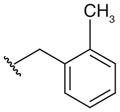

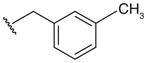

A group of gossypol analogues that are active on human LDH isoforms 1, 5 and C4 includes 2,3-dihydroxy-1-naphtoic acids (2–15; Table 2). These compounds are substituted in position 4 of the naphthalene core with different alkyl groups such as methyl (2–4), N-propyl (5–7) and isopropyl (8–15), whereas position 7, which is the coupling position in the formation of disesquiterpenes such as the parent compound gossypol, may be a hydrogen, a methyl or variously substituted benzyl groups [50,56]. These compounds demonstrated LDH-inhibitory properties on the plasmodial isoform and on the three main human isoforms, being competitive with NADH. The substitution on the dihydroxynaphthoic acid scaffold seems to strongly influence the potency and the selectivity toward a specific isoform. Compound 8, also called 8-deoxyhemigossylic acid, is the reference compound for this class of derivatives: it possesses Ki values approximately 30–45-fold lower on hLDH5 (3 μM) and pf LDH (2 μM) than that on hLDH1 (91 μM), and a certain activity even on hLDH-C4 (10 μM). Differently, its corresponding dimer – 1,1′-dideoxygossylic acid (16; Table 3) – is completely unselective and is reported to efficiently inhibit all the three isoforms (Ki of 1.2, 1.3 and 0.7 μM on pf LDH, hLDH5 and hLDH1, respectively) [49], revealing that the dimerization only improves the activity on hLDH1 and, therefore, probably half of the gossypol scaffold is sufficient for inhibition of hLDH5. This hypothesis can be confirmed by observing the inhibition values of the 2,3-dihydroxynaphtoic acid class (Table 2): they are generally less active on hLDH1 than on the other LDH isoforms. Introduction of a benzyl group in position 7 (10; Table 2) increases the inhibition potency on all the human isoforms, without a significant change in the activity on the malarial enzyme, but this trend is reversed when the benzyl group is p-CF3-substituted, since compound 11 is one of the most active and selective of this class on pf LDH (Ki = 0.2 μM).

Table 2.

2,3-dihydroxy-1-naphtoic acid class: inhibition data on plasmodial and human LDH5 isoforms.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | R2 | Ki (μM) pfLDH | Ki (μM) hLDH5 | Ki (μM) hLDH1 | Ki (μM) hLDH-C4‡ |

| 2† | –CH3 | H | 22 | 34 | >250 | 40 |

| 3† | –CH3 | 13 | 4 | 190 | 3 | |

| 4† |

|

8 | 0.5 | 39 | 3 | |

|

| ||||||

| 5† | –CH2CH2CH3 | H | 6 | 1 | 49 | NT |

| 6† | –CH3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 19 | 0.09 | |

| 7† |

|

0.3 | 0.05 | 1 | 2 | |

| FX11 | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 8† |

|

H | 2 | 3 | 91 | 10 |

| 9† | –CH3 | 1 | 2 | 78 | 3 | |

| 10† |

|

0.7 | 0.2 | 7 | 0.2 | |

| 11† |

|

0.2 | 13 | 81 | 4 | |

| 12‡ |

|

NT | 3 | >125 | 2 | |

| 13‡ |

|

NT | 0.2 | 34 | 0.2 | |

| 14‡ |

|

NT | 0.03 | 8 | 0.5 | |

| 15‡ |

|

NT | 1 | 8 | 0.5 | |

Table 3.

Gossypol derivatives: inhibition data on plasmodial and hLDH isoforms.

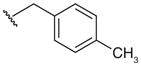

As for the effects of the 4-substitution, compounds 2–4 possessing a 4-methyl group and compounds 5–7 with a N-propyl chain are generally less active on hLDH1 when compared with pf LDH, hLDH5 and hLDH-C4. The activity increases, especially on the human isoforms, when a larger group such as a benzyl is introduced in position 7. In the third sub-group – the 4-isopropyl substituted compounds 8–15 – the p-tolyl derivative 14 results to be the most active hLDH5-inhibitor of this class with a Ki value of 30 nm and a good selectivity over the other two human isoforms, thus opening the way to the development of hLDH5-selective inhibitors structurally related to gossypol.

Subsequently, compound 7 (also called FX11) was further selected as a potential anticancer drug candidate hLDH5-inhibitor of the dihydroxynaphthoic acid group, due to its ability to preferentially inhibit hLDH5 [29]. It was tested again on the purified human liver hLDH5 isoform, this time demonstrating a Ki value of 8 μM in competition with NADH. Furthermore, FX11 was proven to significantly affect cellular energy supply, diminish cellular production of lactate, induce oxidative stress and cause cell death. All these effects were associated with its ability to interfere with hLDH5 activity. FX11 proved to be the first hLDH5-inhibitor that is able to reduce tumor growth in tumor cells such as breast cancer MCF-7 and renal cancer RCC4, which are highly dependent on glycolysis. Moreover, hypoxia accentuates the sensitivity of human P493 B-cells and human P198 pancreatic cancer cells to FX11 action, suggesting that cancer cells are susceptible to the growth-inhibitory effects of this agent because they rely on LDH activity for their metabolism. FX11 also proved to be effective in vivo, by reducing the progression of tumors in xenograft models (dose of 42 μg for daily intraperitoneal injection), such as human lymphoma and pancreatic cancer, supporting the essential role of hLDH5 in tumorigenesis and tumor maintenance. Finally, the use of a 13C NMR technique with hyperpolarized pyruvate demonstrated that FX11 actually diminished pyruvate-to-lactate conversion in vivo in murine xenografts of P493 human lymphoma [57]. In spite of these encouraging results, the highly reactive catechol portion of FX11 makes this molecule unsuitable as a drug candidate and off-target effects of FX11 might also contribute to its biological activities.

Two cyclic derivatives of gossypol, gossylic lactone and iminolactone (17 & 18; Table 3) are structurally similar compounds that differ only for a nitrogen atom present in iminolactone 18 (X = NH) in place of an oxygen atom (X = O) of lactone 17. Initially studied as antiHIV agents [58] and aldose reductase inhibitors [59], lactone 17 and iminolactone 18 displayed a marked inhibitory activity on LDH isoforms. In particular, compound 17 is more potent on malarial (Ki = 0.4 μM) and human isoforms (Ki = 0.6, 0.4, and 1.6 μM on hLDH5, 1 and C4, respectively) than its imino analogue 18, but it does not demonstrate any particular selectivity. On the other hand, compound 18, although it is not so potent, especially on pf LDH (Ki = 16 μM) and hLDH1 (Ki = 92 μM), demonstrated a marked preference for hLDH5 (Ki = 2.5 μM) and hLDH-C4 (Ki = 3.1 μM) [49,50,60].

The class of naphthoic acids (19–24; Table 4) can be included among that of gossypol derivatives, since they possess the same naphthalene scaffold of the disesquiterpene, but it is substituted by polar groups such as carboxylic or sulphonic acids [61]. These commercially available compounds, unlike gossypol and its previously described derivatives, are only modest LDH-inhibitors with millimolar IC50 values on both human and malarial isoforms. Some compounds reported a slight preference for the human isoform (which, by the way, is not specified in the original article), such as the 2,6-naphtalenedicarboxylic acid 19 and the 2,6-naphtalenedisulphonic acid 20, and docking studies revealed that these two derivatives assume a ‘vertical’ binding mode, lying across both the pyruvate and the nicotinamide binding sites of pf LDH, which suggests a similar interaction in the hLDH active site. Compound 25, 6,6′-dithiodinicotinic acid (Table 4), has been originally considered as assimilated to this group of compounds, although it possesses two pyridine rings linked by a disulphur bridge, in the place of the naphthalene central scaffold. Enzyme assays demonstrated that 25 is an unselective inhibitor of pf LDH and hLDH (IC50 = 6.6 and 4.6 mM, respectively).

Table 4.

Naphthoic acids and close analogues: inhibition data on plasmodial and human LDH.

| Compound | Structure | IC50 (mM) pfLDH1 | IC50 (mM) hLDH† |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19 |

|

5.1 | 1.4 |

| 20 |

|

21 | 9.8 |

| 21 |

|

0.52 | 1.1 |

| 22 |

|

2.4 | 5.0 |

| 23 |

|

1.7 | 150 |

| 24 |

|

0.31 | 5.9 |

|

25 6,6′-dithiodinicotinic acid |

|

6.6 | 4.6 |

An unspecified human LDH isoform was used.

hLDH: Human LDH; pf: Plasmodium falciparum.

Data taken from [61].

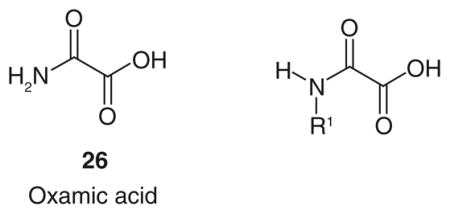

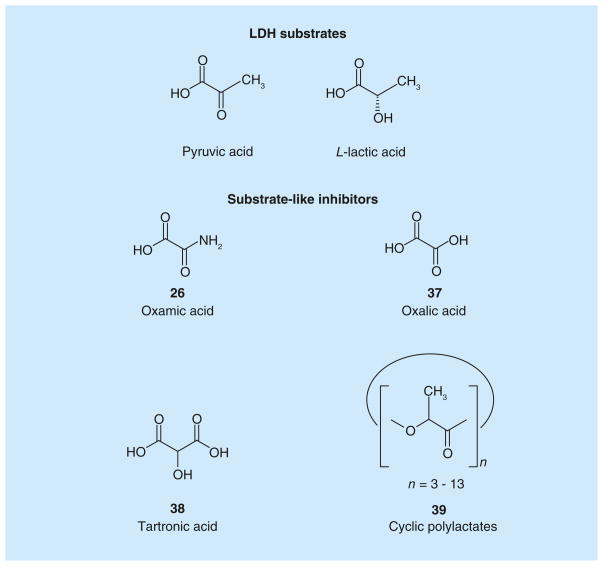

Oxamic acid & substrate-like derivatives

One of the most studied substrate-like inhibitors is represented by oxamic acid (Table 5; Figure 1) [26], which is a structural isostere of pyruvate and is commonly reported in literature as a well-known pyruvate-competitive reference inhibitor of hLDH5 (Ki = 136 μM) [62] and hLDH1 (Ki = 94.4 μM) [63]. The simple and small structure of oxamate confers several disadvantages, making it a rather nonspecific LDH-inhibitor. In fact, it also exerts a certain inhibitory effect on AAT, an enzyme involved in the malate–aspartate shuttle, with a Ki value of 28 μM, so 26 is a more efficient inhibitor of AAT than of LDH. Moreover, oxamate is also an inhibitor of pf LDH (IC50 = 94 μM), and the interest toward inhibition of this isoform resulted in the development of potential antimalaria agents belonging to the class of oxamic acid analogues [64]. Besides its low potency, oxamate is characterized by a poor penetration ability inside cells, due to its highly polar chemical structure. The scarce cell-membrane permeability of oxamate forces researchers to use high concentrations of it in order to see some effects in in vitro experiments concerning the block of aerobic glycolysis and of proliferation of tumor cells. The same high concentrations cannot be reached in in vivo experiments, regardless of the doses administered used [65–70].

Table 5.

N -substituted oxamic acids: inhibition data on plasmodial and human LDH isoforms.

Figure 1. LDH substrates and substrate-like inhibitors.

Structures of LDH substrates, and inhibitors resembling LDH substrates.

Some N-substituted derivatives of oxamic acid (27–36; Table 5) were designed as LDH inhibitors and tested on the three main human isoforms – hLDH5, hLDH1 and hLDH-C4 [50]. Originally, the potential therapeutic role of this group of oxamate derivatives as inhibitors of the human LDH isoforms was still unclear, although their use as male antifertility drugs, or as agents useful in the treatment of lactic acidosis was suggested by the authors. Some simple alkyl and aryl groups were inserted in the amidic nitrogen atom of oxamate with the purpose of producing isoform-selective LDH inhibitors. However, the resulting derivatives displayed similar potencies in the millimolar range on the three human enzymes, whereas some selectivity for the Plasmodium isoform was achieved in a few cases. In detail, benzyl derivative 28 reached the lowest Ki value (0.4 mM) on hLDH5 among these substituted oxamic acid derivatives, but the insertion of substituents on the phenyl ring (29–30) or variations of the length of the alkyl chain linker (31–35) only slightly affected the activity of the resulting compounds, and in some cases determined a marked loss of inhibitory potency, such as in compounds 34 (IC50 > 10 mM on hLDH5 and hLDH-C4), and 35 (IC50 > 10 mM on hLDH-C4). As for species selectivity, some of the compounds (28–33 and 36) were also tested on pf LDH [60,63], and generally displayed better inhibition properties for the Plasmodium isoform when compared with the human enzymes, with good selectivity levels. The most selective pf LDH-inhibitor is represented by the N-phenethyl oxamate analogue 31. A close analogue of oxamate is oxalic acid 37 (Figure 1), which was reported to inhibit both hLDH5 and hLDH1. This compound, unlike oxamate, which competes with pyruvate, illustrates a competitive behavior versus lactate, the product of the reductive direction of LDH-catalyzed reaction [71]. Nisselbaum et al. reported a Ki value for 37 of 142 μM on hLDH5 and of 23.6 μM on hLDH1, which were calculated in the reverse (oxidative) reaction using lactate as the substrate and NAD+ as the cofactor [72].

Tartronic acid (38; Figure 1), also known as 2-hydroxymalonic acid, was discovered by the research group of Fiume et al. as a LDH inhibitor able to block aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells. Tartronic acid was one of the first LDH inhibitors to be studied as an anticancer agent, thus opening the way to further experimental studies in this field. Fiume et al. found that this malonate derivative was able to reduce the growth of some tumor cell lines, such as Yoshida’s ascites hepatoma and Ehrlich’s ascites tumor, giving a 58% inhibition at a concentration of 50 mM. However, this small molecule has the disadvantage of being a weak and unselective inhibitor of LDH, since it also inhibits cytosolic malate dehydrogenase (MDH), an enzyme participating in the Krebs cycle [65,73,74].

Cyclic polylactates (39; Figure 1) are included in this section of substrate-like LDH inhibitors due to their chemical structure, which contains repetitions of the lactate units. Mixtures of cyclic polylactates, with a degree of polymerization number, ranging from 3 to 13, were demonstrated to have a relevant noncompetitive inhibitory activity on the enzyme, with a calculated apparent Ki value on LDH (from rabbit muscle) of 2.3 mg/ml, as well as in in vitro cellular assays. This effect determines the inhibition of the aerobic glycolysis in FM3A ascites tumor cells and the reduction of tumor cell growth. The efficacy of these polymers was further validated in vivo, where the survival of mice treated with cyclic polylactates after inoculation of FM3A ascites tumor cells was significantly longer than that observed in untreated mice, without any additional significant side effects. Simultaneously, polylactates were tested on a second enzyme of the glycolytic pathway, PK, also demonstrating a good inhibition activity on this target, which most likely contributes to the overall antitumor activity observed in cellular assays [75].

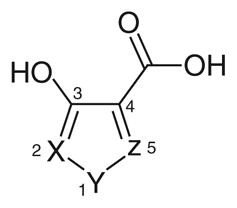

Azoles

Azole-based inhibitors were initially discovered in a high-throughput enzymatic screening aimed at finding new antimalarial drugs, but as it happened, in addition to their inhibitory activity on pf LDH, they also demonstrated a certain inhibition of the human isoform hLDH1 [76]. 1,2,5-oxadiazole (40), 1,2-isoxazole (41) and 1,2,5-thiadiazole (42) reported in Table 6, are the only examples of this class with IC50 values on hLDH1 in the micromolar range, although they displayed a marked selectivity for the plasmodial isoform. These azoles illustrated a mixed competition behavior towards NADH and pyruvate, and a full competition against lactate in the oxidative direction of the LDH-catalyzed reaction. They have a common pharmacophoric portion with hydroxyl and carboxylic groups in adjacent positions, as often observed in many LDH inhibitors. Analogues of these three compounds, where insertion of substituents in the azole ring, or modifications of the ‘3-OH, 4-COOH’ moiety were applied, displayed a dramatic loss of potency, suggesting that the presence of the ‘OH-COOH’ motif is essential for the interaction of these azole derivatives with the LDH active site. Crystallographic analysis of the enzyme complexed with compound 40 (protein data bank code: 1T2F) revealed that the carboxylic acid formed salt bridges with two arginine residues of the active site (Arg109 and Arg171). The hydroxyl group was involved in a hydrogen bond network with the side chains of Leu140, His195 and Arg109, whereas the azole heterocycle of the inhibitor was parallel (π-stacking) to the nicotinamide ring of the NAD+ co-crystallized cofactor. Moreover, it is evident that the presence of a sulfur atom in position 1 of the pentacyclic ring, as in compound 42 (IC50 = 10.27 μM), is preferred for inhibition of hLDH1, whereas when the sulfur is replaced by an oxygen atom, the resulting oxadiazole (40) and isoxazole (41) experienced a substantial loss of activity on hLDH1 (IC50 = 72 and 54 μM, respectively). Unfortunately, since these derivatives have a simple and small structure, they are potentially able to interact with several other biological targets, and the impossibility to extend this chemical class with chemical modifications blocked their further development. In 2011, compound 42 (Table 6) was further studied and re-tested by AstraZeneca (Macclesfield, UK), confirming the inhibition data on hLDH1 (IC50 = 7.8 μM) and revealing a very modest inhibition on hLDH5 (IC50 = 450 μM) Moreover, the binding mode in the active site of hLDH5 was demonstrated by NMR and crystallographic studies [77].

Table 6.

Azole derivatives: inhibition data on human LDH1 and Plasmoidum falciparum LDH.

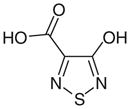

Quinolines & 1,4-dihydro-4-quinolones

Since 1972 the quinoline scaffold has been employed as a suitable heterocycle for the design of inhibitors of several dehydrogenases. Baker et al. reported a series of quinoline-based inhibitors containing the OH-COOH motif (43–47; Table 7), as well as 1,4-dihydro-4-quinolones with a carboxylic function in position 3 (48 & 49; Table 7), which were designed with the aim of obtaining inhibitors of four dehydrogenases: LDH, GLDH, GAPDH and MDH. These resulting enzymes are all involved in the glucose metabolism in cancer cells. This way the authors intended to deprive cancer cells of energy supply by inhibiting the above-mentioned four dehydrogenases, thus leading to cancer cell death. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported approach where LDH inhibitors were intentionally realized as potential anticancer agents affecting the glycolytic pathway [78–81]. These studies confirmed as a general trend that 4-hydroxyquinoline-2-carboxylic acids are generally less active than their 4-hydroxyquinoline-3-carboxylic counterparts, thus confirming that the presence of the hydroxyl and carboxyl groups in adjacent positions is favorable for the inhibition potency on dehydrogenase enzymes. Furthermore, the ‘4-OH/3-COOH’ series is characterized by an easier synthetic accessibility and, as a consequence, this group was selected and further investigated for structural modifications. In detail, compound 43 (Table 7) is the most active LDH inhibitor belonging to the series of 4-hydroxyquinoline-2-carboxylic acids. 4-hydroxy-3-carboxy-substituted quinolines compounds 44–47 (Table 7) revealed that the substitutions in positions 5, 6 and 8 of the heterocyclic scaffold gave the most potent LDH-inhibitors of this series. In these derivatives, the presence of small groups such as 6-acetylamine (44) and 8-methoxy (45) increased the selectivity for LDH (hLDH IC50 = 86 and 98 μM, respectively) over the other three dehydrogenases (IC50 > 200 μM on all of them). On the other hand, when the size of substituents was increased, the resulting compounds displayed a marked inversion of selectivity. In fact, both compounds 46 and 47 preferentially inhibited malate dehydrogenase (IC50 = 2.7 μM for 46, IC50 = 1.0 μM for 47) and 47 demonstrated similar potencies on LDH (IC50 = 6.7 μM) and glutamate dehydrogenase (IC50 = 5.2 μM). As for the dihydroquinoline derivatives, the p-nitrophenoxyalkyl- substituted compound 48 represents the best LDH inhibitor (IC50 = 31 μM) of this group, although it proved to be unselective, reporting similar IC50 values described on the other three dehydrogenases. Slight changes of R1 led to an evident increase in selectivity, generally associated to a contained reduction of LDH inhibition potency. For example, the replacement of the p-NO2 substituent of 48 with an amino-group (49) caused a slight loss of activity on LDH (IC50 = 80 μM) associated with a high increase of selectivity (IC50 > 200 μM on all the other dehydrogenases).

Table 7.

Quinoline-based compounds: activity values on human LDH.

The interest toward the quinoline scaffold in the search for new LDH inhibitors has been very recently renewed, and a series of quinoline-based hLDH5 inhibitors for the treatment of cancer and diseases associated with tumor cell metabolism was patented by GlaxoSmithKline (Brentford, UK) [202]. Most of the compounds included in this patent are generally substituted in position 3 of the quinoline scaffold with amide or sulfonamide groups, in position 4 with an aniline portion, whose phenyl ring principally bears carboxylic acids in one or more positions, and finally in position 7 of the central scaffold with variously substituted aromatic or heteroaromatic rings. Compound 50 (Figure 2) is the most representative example of this class of derivatives, displaying an excellent level of inhibition of hLDH5, as demonstrated by its pIC50 value of 7.2 (IC50 = 63.1 nm). The structural features of this wide class of compounds are quite different from those of previously reported LDH inhibitors, where a carboxylic acid is present in the adjacent position or at least in proximity of a hydroxyl group, or a carbonyl-type oxygen atom. In this series, the pyridine ring of the quinoline scaffold, which is substituted with the amide/sulfonamide group, closely resemble the structure of the nicotinamide portion of cofactor NADH/NAD+, whereas the COOH group on the aniline pendant ring may efficiently mimic the substrate (pyruvate/lactate), and consequently bind the enzyme in the substrate-binding region. Curiously, these inhibitors were tested on hLDH5 in the ‘reverse reaction’, consisting of the oxidation of lactate to pyruvate, using NAD+ as the cofactor in a diaphorase-coupled assay. Moreover, they were assayed in vitro on U2OS cells from human osteosarcoma, to establish the cellular reduction of pyruvate formation, subsequent to LDH inhibition. These compounds also proved to be active on Snu398 hepatocellular carcinoma cells [82].

Figure 2.

A quinoline-based compound.

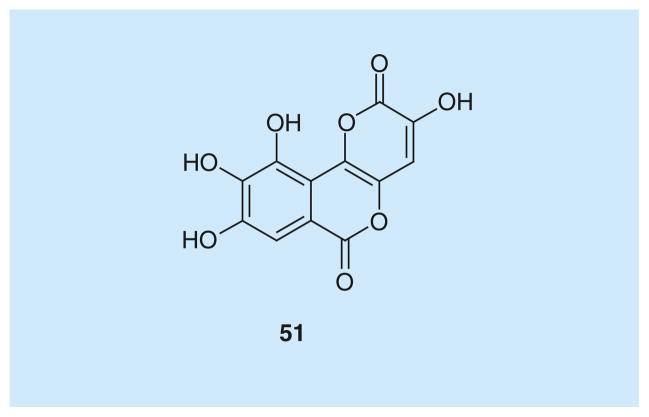

Galloflavin

Galloflavin (51; Figure 3) has been recently identified as a novel inhibitor of human isoforms hLDH5 and hLDH1. It was tested in competition with both pyruvate (Ki = 5.46 μM on hLDH5, Ki = 15.1 μM on hLDH1) and NADH (Ki = 56.0 μM on hLDH5, Ki = 23.2 μM on hLDH1). The resulting kinetic data, analyzed by applying the mixed-model inhibition fit, revealed that galloflavin preferentially binds the free enzyme without being fully competitive with neither the substrate or the cofactor. This green–yellow gallic acid derivative, which was recently identified by virtual screening of molecules from the national cancer institute dataset, and was later re-synthesized and fully characterized by Manerba et al., demonstrated promising antitumor effects [83].

Figure 3.

Galloflavin.

Galloflavin blocked aerobic glycolysis in a PLC/PRF/5 cell line from hepatocellular carcinoma without affecting mitochondrial respiration. It reduced lactate production and decreased ATP levels at a concentration of approximately 200 μM, which is the same concentration that was reported to:

Completely block the enzymatic activities of hLDH5 and hLDH1;

Inhibit cell growth (60% inhibition) and induce apoptosis.

The effects of galloflavin on tumors were further examined by studying the action of this molecule on three different pathological subtypes of human breast cancer, in which LDH plays a critical role for their growth and maintenance: the well differentiated cell line MCF-7; a more aggressive form of tumor, such as the MDA-MB-231 cell line; and, MCF-Tam, a tamoxifen-resistant sub-line of MCF-7 [84]. MDA-MB-231 and MCF-Tam are the most glycolytic phenotypes, nevertheless, galloflavin exerted comparable growth inhibition on all the three tested cell lines (IC50 values in the 90–150 μM range). This effect is most likely due to the activation of a stress response in the glycolysis- dependent MDA-MB-231 and MCF-Tam cells, which renders these cells less susceptible to chemotherapeutic agents, and the inability to overcome the ATP depletion caused by galloflavin by exploiting the mitochondrial activity. Moreover, galloflavin proved to be less cytotoxic in normal cells, such as human lymphocytes and lymphoblasts. Some preliminary in vivo toxicity data are available on the National Cancer Institute website [301]; mice well tolerate galloflavin at the maximum tested dose (400 mg/kg, injected intraperitoneal) without lethal side effects. Obviously, these promising results of the effects of galloflavin in aggressive tumors encourage further studies on this molecule.

A recent discovery has associated additional pharmacological properties to galloflavin, which proved to be able to interfere with the interaction of hLDH5 with ssDNA, consequently blocking RNA synthesis in vitro [85], a process that was found to require an unexpected ‘nuclear’ role played by hLDH5. In fact, some glycolytic enzymes, such as hLDH5 itself, are known to also be ssDNA binding proteins, playing a role in DNA transcription and replication [86], and this interaction involves the NADH binding site. This observation explains why galloflavin, which occupies the NADH binding site of hLDH5, strongly hampers the interaction of the enzyme with ssDNA and its transcription. In light of this property of galloflavin, its action on cancer cells that do not rely exclusively on glycolysis and on LDH enzymatic activity, such as the previously discussed MCF-7 cells, can be ascribed to an inhibition of the RNA synthesis, rather than to the impairment of aerobic glycolysis.

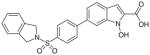

N-hydroxyindole-based inhibitors

Another group of hLDH5 inhibitors is represented by N-hydroxyindole-based derivatives, which have a central indole scaffold possessing an OH group on the nitrogen atom in position 1 and a carboxylic acid in position 2 (52–60; Table 8). Generally, they behave as competitive inhibitors with respect to both NADH and pyruvate, and report Ki values in the low micromolar range on the target enzyme [87–90]. These compounds mostly display a good specificity for isoform 5 of LDH, since only a few of them induced a weak inhibition of the heart isoform of hLDH1. N-hydroxyindoles (NHIs) are scarcely represented chemical entities in nature. In fact, only a few natural compounds possessing a highly substituted NHI moiety within their complicated structures were recently discovered [91,92]. Moreover, they are also a relatively new and unexplored class of heterocyclic compounds in the field of medicinal chemistry, mainly due to the few suitable synthetic methods for their preparation, and also to their supposedly low stability. These molecules retain the OH-COOH motif observed in many other LDH inhibitors. In fact, the N-OH/COOH pharmacophoric portion partially resembles the structure of the natural substrates of LDH, pyruvate or lactate, that are α-ketoacid (pyruvate) or α-hydroxyacid (lactate). Among these derivatives, compound 52 (Table 8), possessing a trifluoromethyl group in position 4 and a phenyl substituent in position 6, demonstrated a Ki value of 8.9 μM in kinetic assays in competition with NADH and of 4.7 μM in competition with pyruvate, whereas 5-phenyl-substituted NHIs (53; Table 8) displayed slightly higher Ki values in both kinds of assays (Ki = 10.4 and 15.7 μM in NADH-competition and pyruvate- competition experiments, respectively). Preliminary molecular modeling studies for this chemical class indicated that the carboxylic group makes a salt bridge with catalytic Arg169, and it also forms a hydrogen bond with Thr248 in the substrate-binding site of the enzyme. Furthermore, the N-hydroxy group is involved in some direct and water-mediated hydrogen bonds with Thr248 and His193. In addition, the presence of an aromatic portion in position 6 is justified by considering that the phenyl ring of compound 52 is placed in a mainly lipophilic pocket at the entrance of the enzyme active site, and it occupies a part of the cofactor binding cavity. The introduction of a chlorine atom in para position of the phenyl ring in position 6 and the presence of a p-biphenyl substituent in the same position were revealed to be beneficial for enzymatic activity. The resulting compounds, p-chloro-derivative 54 and biphenyl-derivative 55 (Table 8), reported very similar Ki values in competition with the cofactor (Ki ~ 5 μM). However, in the pyruvate-competition assay the presence of the p-chlorine atom proved to negatively affect the activity of the resulting compound 54 (Ki = 56 μM). Finally, the co-presence of two phenyl rings in the adjacent positions 5 and 6 of the central scaffold generated compound 56 (Table 8), which possesses a good inhibition activity (Ki = 5.4 and 7.5 μM in NADH and pyruvate-saturating conditions, respectively). A slightly lower potency is generally associated to the class of 1,2,3-triazole-based NHIs. Among them, the most efficient inhibitors were found to be compound 57, substituted with a phenyl-triazole group in position 4, and ‘dimeric’ analogue 58, where two NHI portions are linked together through a 1,3-bis(triazole)-propane chain (Table 8), reaching Ki values of 28 μM with 57 and 20 μM with 58 in competition assays versus NADH. The observation that aromatic substituents in position 6 of the central scaffold are usually beneficial for biological activity is confirmed by the subclass of sulfonamide-containing NHIs, such as compounds 59 and 60 (Table 8). In this case, the N-methyl-N-p-chlorophenyl sulfonamide 59 is well tolerated by the enzyme (Ki = 6.6 μM vs NADH). The addition of a phenyl spacer between position 6 of the indole scaffold and an isoindoline sulfonamide portion produced compound 60, which maintained a good activity (Ki = 7.7 μM vs NADH). Representative compound 52 proved to inhibit lactate formation in cells, and to inhibit growth of cancer cells, even under hypoxic conditions [87].

Table 8.

N -Hydroxyindole derivatives: inhibition data on human LDH5, in competition with NADH and pyruvate.

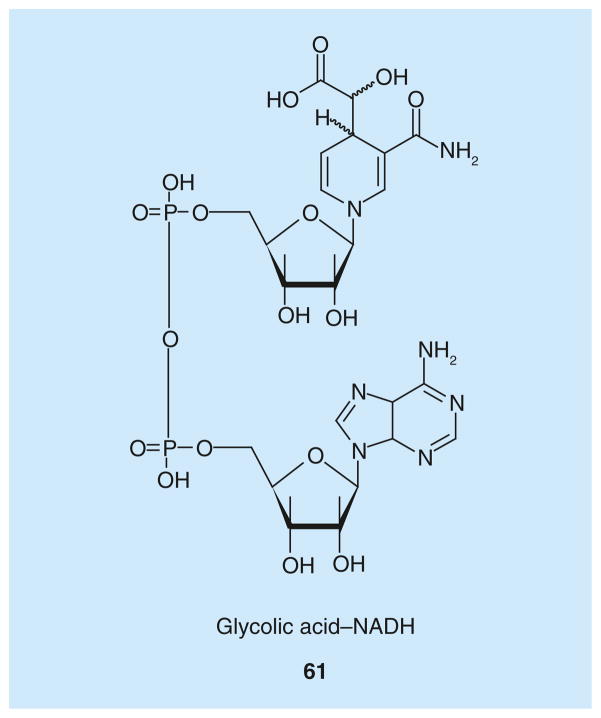

‘Bifunctional’ inhibitors

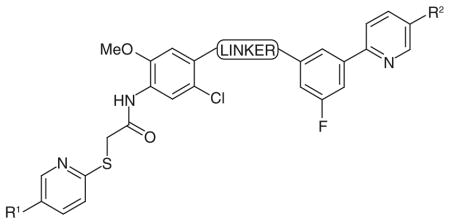

‘Bifunctional’ inhibitors is a term that was coined to indicate compounds where a cofactor-like portion and a substrate mimic are connected through a linker, so they extend through both cofactor- and substrate-binding pockets, in order to achieve a dual binding in the NADH- and pyruvate-binding pockets of the LDH active site. The crystal structure of hLDH5 complexed with NADH and oxamate (PDB code: 1i10 [93]) illustrates that the cofactor binds in an extended conformation with its two terminal portions, the nicotinamide and the adenosine moieties, at two ends of the cofactor binding site, far-between 20 Å; while the substrate analogue oxamate lies parallel to the nicotindamide ring.

Powerful design strategies aimed at obtaining LDH bifunctional inhibitors have been successfully applied in the past few years, with a big help given by the close proximity of the substrate and the cofactor-binding sites. The first example of this class, glycolic acid–NADH conjugate 61 (Figure 4), was obtained by simply attaching a glycolic acid portion to the 4-position of the reduced nicotinamide ring of NADH [94]. The α-hydroxyacid moiety was intended to mimic the substrate pyruvate, which is positioned closely to the nicotinamide ring of NADH in the enzyme active site. This glycolic acid–NADH conjugate, which was prepared by incubating NADH in alkaline solutions in the presence of air, demonstrated a high inhibition activity on bovine heart and rabbit muscle LDH isoforms, behaving as a competitive inhibitor with respect to NADH with a calculated Ki value of approximately 4 nm. Compound 61 demonstrated a cardioprotective effect both in vitro and in vivo, promoting cell survival in cultured mouse cardiomyocytes exposed to hypoxia–reoxygenation stress and reducing the extent of tissue damage caused by myocardial infarction in isolated mouse hearts. In fact, the large intracellular levels of lactate produced by heart cells during ischemia led to severe heart injury, so inhibition of lactate production should counteract this damage. Nonetheless, this consideration only partially explains why a LDH inhibitor could be of some interest in this pathological situation, because the inhibitor was added only during the reperfusion phase of the reported experiments. As a matter of fact, the cardioprotective effect is probably due to the reduced formation of pyruvate from lactate in the LDH-catalyzed reverse (oxidative) reaction and to the subsequent suppression of reactive oxygen species formation, usually produced during metabolism of pyruvate in the OXPHOS. Unfortunately, one of the main limitations of compound 61 is its low cell permeability, which may limit its effective clinical application as a cardioprotective agent.

Figure 4.

Glycolic acid–NADH conjugate.

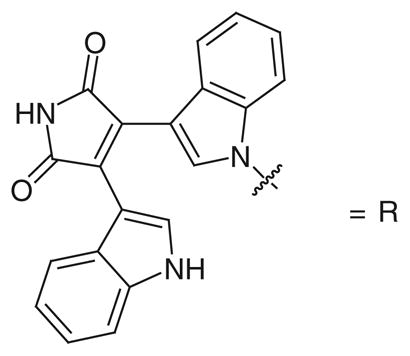

A 31-member library of bifunctional derivatives was synthesized by using a fragment-based approach, taking advantage of a ‘click’ chemistry strategy [95]. These bifunctional compounds were designed as hLDH5 inhibitors in the search for antiglycolytic therapeutic agents against cancer. Derivatives belonging to this class possess a NADH-like portion, the bis(indolyl)maleimide moiety, which is known to be an adenosine mimetic, and can be easily synthesized and conjugated. The other functional group present in these molecules is a carboxylic acid, which mimics the COOH function of the natural substrates of the enzyme. The linker between these two portions is constituted by alkyl or aryl–alkyl chains of different length connected by means of a 1,2,3-triazole ring, which is produced in the Huisgen cycloaddition reaction. Compounds 62, 63 and 64 (Table 9) demonstrated hLDH5 inhibition properties. Compound 62 was demonstrated to be the most potent inhibitor, illustrating an IC50 value of 14.8 μM. The introduction of an additional methylene unit in the linker caused a sharp drop in the inhibitory potency (63; IC50 > 170 μM), whereas the replacement of the phenyl ring of 63 with three methylene units maintained an appreciable activity in the resulting compound 64 (IC50 = 35.9 μM). Molecular docking studies indicated that the terminal COOH portion probably establishes strong polar interactions in the substrate-binding site of the enzyme.

Table 9.

Bifunctional inhibitors containing a bis(indolyl)maleimide moiety: inhibition data on human LDH5.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Compound | Structure | IC50 (μM) hLDH5 |

| 62 |

|

14.8 |

| 63 |

|

173.8 |

| 64 |

|

35.9 |

hLDH: Human LDH.

Data taken from [95].

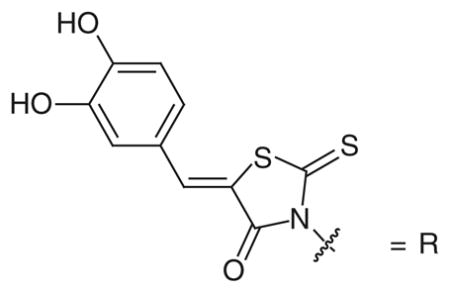

Structural proteomic-based methods supported by NMR studies were developed by Triad Therapuetics Inc. (CA, USA), in order to discover inhibitors of multiple oxidoreductase enzymes, including LDH [96]. In fact, oxidoreductases usually share the same Rossmann fold domain [97,98] to bind the cofactor NAD/NADPH, but they differ in their substrate-binding pockets, in accordance with their biological functions. Initially, a common ligand for the cofactor binding site was identified (referred as ‘common ligand mimic’ [CLM]) by a computational screening of ligand candidates and by subsequent enzyme kinetic assays. Finally, an NMR-based binding site mapping was exploited to design diversity elements directed to the adjacent substrate binding site (referred as ‘specificity ligand’), in order to obtain a combinatorial library with these dual structural features. The resulting bifunctional library was screened on LDH, as well as on dihydrodipicolinate reductase (DHPR) and on 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DOXPR). In particular, compounds 65–68 (Table 10) were tested in a NADH-based spectrophotometric enzymatic assay on LDH without specifying the isoform used, and their inhibition potencies were unusually reported as Kis values, that are defined as the dissociation constants among the substrate–enzyme complex and the inhibitor, and represent the slope inhibition constants in the competitive model [99]. The four compounds share the same CLM motif, represented by the 3,4-dihydroxyphenylmethylene-rhodanine group (indicated as R in Table 10). The simplest compound (65), where the CLM is linked to an acetic acid group, showed a competitive behavior versus the cofactor and a weak binding affinity for LDH, with a Kis in the micromolar range. A further diversification of the specificity ligand portion, such as that represented by an aryloxy-substituted anilide function in compound 67, caused a slight improvement of the potency against LDH; however, a strong preference for DOXPR inhibition (IC50 = 202 nm) was found. Different amide groups, such as those of 66 and 68, led to the production of the most potent LDH inhibitors of this class. In particular, the 2,6-pyridine dicarboxylate portion present in compound 68 was chosen as a stable analog of the dihydrodipicolinate substrate of DHPR, mimicking the ternary complex that forms during the catalytic cycle, and as a consequence it demonstrated the best inhibition on DHPR (Kis = 100 nm), which was superior to its inhibition of LDH (Kis = 0.62 μM). On the other hand, the 3,4-dichlorobenzylamide-substituted derivative (66) was found to be the most potent LDH-inhibitor obtained in this study (Kis = 0.042 μM), with a remarkable selectivity for LDH over the other two enzymes (Kis > 50 μM for DHPR and IC50 = 10 μM for DOXPR).

Table 10.

Bifunctional inhibitors containing a 3,4-dihydroxyphenylmethylene-rhodanine moiety: inhibition data on LDH†.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Compound | Structure | Kis (μM) LDH |

| 65 |

|

55 |

| 66 |

|

0.042 |

| 67 |

|

12 |

| 68 |

|

0.62 |

The LDH isoform used is unspecified.

Data taken from [96].

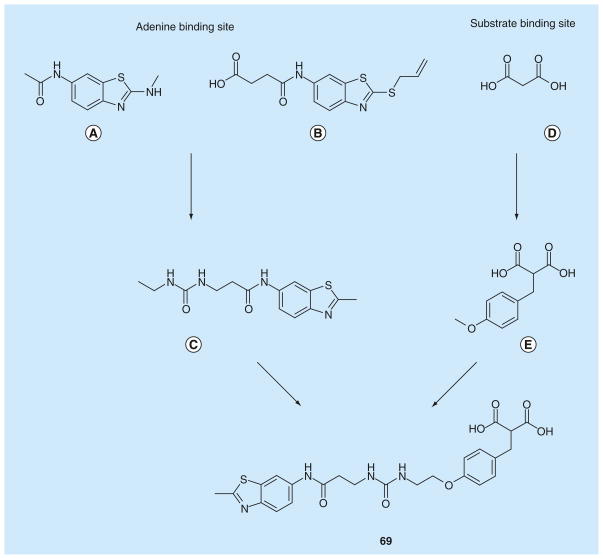

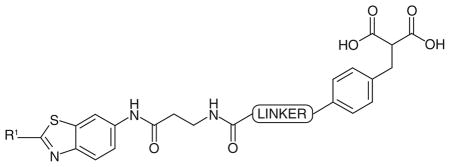

In 2012, a fragment-based lead generation strategy was disclosed by AstraZeneca, which led to the discovery of some of the most potent hLDH5 inhibitors reported in literature so far [77]. Ligand- and protein-observed NMR techniques were adopted for the primary screening of fragments, which were then assisted by BIAcore assays (based on surface plasmon resonance methods). x-ray crystallography (by using a rat LDH5 protein crystal structure) was utilized for the optimization of the fragment hits that occupy either the substrate-binding site, or the cofactor pocket of the enzyme. Finally, the best fragments were linked to obtain nanomolar bifunctional inhibitors. The selectivity over hLDH1 was not taken into consideration to avoid further complications during the complex sequence of experiments, in fact the selectivity over this isoform was not considered as strictly necessary by the authors.

The first screening revealed the benzothiazole portion (Figure 5A) as a developable fragment, demonstrating a tight binding to the enzyme both in NMR and BIAcore assays, with a good ligand efficacy (ligand efficacy = −RTlnKd/N, where N is the number of nonhydrogen atoms [100]), even if it did not display an acceptable IC50 value in the enzyme assay (over 500 μM). The co-crystal structure of benzothiazole with rat LDH5 confirmed the binding of the heterocyclic ring in the hydrophobic pocket where the adenine ring of NADH lies (Figure 5A). Subsequently, the benzothiazole fragment, containing a S-allyl group in position 2 and an amido-butanoic acid chain on the phenyl ring (Figure 5B), was found to assume a similar binding mode, together with a tighter binding in the BIAcore assay (Kd = 130 μM) than that of the parent benzothiazole (Figure 5A). On the other hand, simple malonate (Figure 5D) was chosen as the starting point in the screening for the substrate and/or nicotinamide-binding site ligand, thanks to its central methylene group, which could act as a fragment-growth point. Benzyl-substituted malonate derivatives, such as the compound shown in Figure 5E, were selected as fragments binding to the substrate-site of the enzyme. Then, the fragments shown in Figures 5C & 5E were selected and subsequent fragment linking gave rise to compound 69, where the two antipodal portions are linked by a urea group. This compound displayed a relevant increase in enzyme-binding affinity when compared with the single fragments, with a Kd value in the BIAcore assay of 0.13 μM. Moreover, compound 69 represented the first compound to be active in the enzymatic inhibition assay, with an IC50 of 4.2 μM. A subsequent optimization process involving slight variations of the chemical structure and the length of the linker produced several compounds, and some of the best representative examples (70–73) are reported in Table 11. The replacement of the methyl on the benzothiazole of 69 with a S-propyl group gave compound 70, which demonstrated a marked increase of the affinity (Kd = 0.046 μM), but only a modest improvement in the enzyme inhibitory properties (IC50 = 3.1 μM). Compound 71, which possesses a slightly shorter linking group than that of 70, displayed a very similar binding affinity (Kd = 0.06 μM), but its hLDH5 inhibition potency resulted to be remarkably improved with a sub-micromolar IC50 value (0.29 μM). The replacement of the urea portion with an amide group in the central linker produced other active inhibitors, such as 72 and 73. Among them, S-propyl derivative 73 is the most potent inhibitor of this class, as demonstrated by both the BIAcore binding affinity assay (Kd = 0.008 μM) and the enzyme inhibition assay (IC50 = 0.27 μM).

Figure 5. Progressive fragment screening and linking, leading to bifunctional inhibitor 69.

(A), (B) and (C) are fragments binding in the adenine binding site of the cofactor, while (D) and (E) are fragments binding in the pyruvate binding site.

Table 11.

Bifunctional malonate inhibitors of AstraZeneca (Macclesfield, UK): inhibition data on human LDH5.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Structure | IC50 (μM) hLDH5 | |

| R1 | Linker | ||

| 70 |

|

S-propyl | 3.1 |

| 71 |

|

S-propyl | 0.29 |

| 72 |

|

Me | 0.5 |

| 73 |

|

S-propyl | 0.27 |

hLDH: Human LDH.

Data taken from [77].

These malonate derivatives were reported to lack activity in cell-based assays, probably because of their low cell penetration due to the diacid malonic functionality. For this reason, dimethyl ester of active hLDH5 inhibitor 72 (IC50 = 0.5 μM) was prepared, and it displayed a good antiproliferative activity in cells (IC50 = 4.8 μM), thus supporting the hypothesis of the prodrug behavior of diester derivatives. It is important to mention that the AstraZeneca group also tested some previously reported LDH-inhibitors, such as 7 (FX-11), 52 and 66. Under their conditions, compound 66 displayed a nonspecific superstoichiometric binding, and a similar ambiguous behavior was observed with 7 [77]. With regard to compound 52, the same authors confirmed specific binding of this inhibitor to LDH-A by 2D-NMR and reported a calculated Kd value of approximately 9 μM, although the results from surface plasmon resonance experiments were ambiguous and led the authors to hypothesize the occurrence of significant levels of nonspecific binding with this compound [77].

A similar fragment-based strategy was more recently applied by researchers at ARIAD Pharmaceuticals (MA, USA) and it resulted in the development of other potent hLDH5 inhibitors [101]. The primary screens identified 6-phenyl-nicotinic acid as the first fragment able to bind the substrate site and, in part, also the nicotinamide- hosting pocket. Starting from this small fragment, further optimization and exploration of more elaborate analogues were performed with the aim of extending the molecule into the rest of the enzyme active site. The structures of the most promising fragments were tethered together with some flexible linkers in order to properly cover the distance between the two extreme portions of the enzyme cavity. This resulted in a series of compounds possessing, on one side, a 6-(3-fluorophenyl) nicotinic acid terminal portion which binds in the nicotinamide binding pocket of the enzyme, and, on the other side, a second nicotinic acid portion, connected to the rest of the molecule through a thio-arylalkyl chain, which instead lies in the adenosine site (74–80; Table 12). A moderate activity was found with compound 74 (Table 12), possessing a simple polyether linker. In compounds 75 and 76 (Table 12) the linker was shortened and substituted with four hydroxyl groups in order to achieve additional interactions with the enzyme active site, by mimicking the diphosphate portion of the NADH cofactor. Compounds 75 and 76 differ only for the terminal heteroatom of the linker chain, which is constituted by an ether-type oxygen atom in compound 75, or by an amine-type nitrogen atom in compound 76. This minor difference proved to be important for the activity of the resulting compounds. In fact, amine-containing compound 76 proved to be the most active compound of this series, with an IC50 of 0.12 μM, whereas its oxygenated analogue 75 is approximately fourfold less potent (IC50 = 0.44 μM).

Table 12.

Bifunctional inhibitors of ARIAD Pharmaceuticals (MA, USA): inhibition data on human LDH5.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Structure | IC50 (μM) hLDH5 | ||

| Linker | R1 | R2 | ||

| 74 |

|

COOH | COOH | 59 |

| 75 |

|

COOH | COOH | 0.44 |

| 76 |

|

COOH | COOH | 0.12 |

| 77 |

|

COOH | COOH | 2.40 |

| 78 |

|

COOH | COOH | 15 |

| 79 |

|

H | COOH | 2.40 |

| 80 |

|

COOH | H | 13 |

hLDH: Human LDH.

Data taken from [101].

The presence of the four hydroxyl groups and their chirality was found to be very important, as confirmed by x-ray studies. In fact, all the OH groups are placed in a solvent-exposed region between the two antipodal binding sites of the enzyme. So they form several direct and water-mediated hydrogen bonds with the protein. This observation was further confirmed by the fact that their removal or changes in their stereochemistry caused substantial reductions of the inhibition potencies of the resulting compounds (77 & 78; Table 12). The presence of two carboxylic groups at both ends of the two portions caused a reduced permeability of these compounds through the cell membrane and, consequently, poor results in cellular assays. Therefore, lead compound 76 was modified by removing one of these groups from either side, leading to compounds 79 and 80 (Table 12). Both compounds displayed a good activity in the enzyme inhibition assay, although lower than that of their parent dicarboxylate analogue 76. In particular, a higher potency was observed (IC50 = 2.4 μM) when the carboxylic group interacting in the substrate binding site was maintained (79) when compared with the other example (80) where the preserved COOH group is positioned in the opposite region of the enzyme active site (IC50 = 13 μM). This result suggests that the presence of an acid group in the pyruvate-binding site is strictly necessary, probably due to the fact that the COOH of the substrate usually binds the protein in that position. Otherwise, transforming the two COOH groups into two methyl esters, in order to increase the cellular permeability, resulted in inactive compounds (not illustrated). Compound 76 and the mono-acid derivatives 79 and 80 were evaluated in cellular assays to test if they could reduce lactate levels in cancer cells (lymphoma) at a 200 μM concentration: 76 demonstrated a limited reduction of lactate, which was similar to the effect of oxamate (tested as the positive control), whereas both 79 and 80 drastically reduced the production of lactate, demonstrating promising anticancer effects.

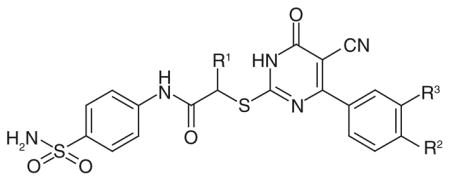

Dihidropyrimidines

Very recently, a high-throughput screening carried out by researchers at Roche (Basal, Switzerland) and Genentech (CA, USA) led to the discovery of potent hLDH5 inhibitors (81–85; Table 13) possessing a 2-thio-6-oxo-1,6-dihydropyrimidine structure [102]. The first representative inhibitor of this series, compound 81, reported an IC50 of 8.8 μM in the enzymatic assay on hLDH5. The activity of 81 was confirmed by MS and surface plasmon resonance experiments, and its mechanism of action was further elucidated, suggesting that the presence of the cofactor in the LDH active site is required for optimal binding of the inhibitor itself. Moreover, compound 81 was tested on other related targets to assess its specificity. It demonstrated a very similar inhibition potency on the heart isoform hLDH1 (IC50 = 11.1 μM), which does not surprise due to the high similarity between isoforms 5 and 1. On the contrary, it proved to be a very weak inhibitor of the two isoforms of malate dehydrogenases (MDH1 and MDH2), thus demonstrating that it is not an unspecific inhibitor of dehydrogenase enzymes. Subsequently, compound 81 was modified with the aim to improve its potency, but any attempt to modify or replace the sulfonamide substituent on the anilide ring, the cyano group of the central dihydropyrimidine scaffold, or the p-chloro atom on the peripheral phenyl substituent led to a loss of inhibition potency. The introduction of a methyl group on the aliphatic methylene (R1; Table 13) strongly increased the activity by more than tenfold. In fact, compound 82 displayed an IC50 of 0.48 μM. Such an improvement of inhibition potency was substantially maintained even when additional halogens, such as chlorine or fluorine atoms, were added to the phenyl ring in the ortho position with respect to the already present chlorine atom (R3; Table 13). For example, compound 83 (R3 = Cl) and compound 84 (R3 = F) exhibited activities in the nanomolar range (IC50 = 0.75 and 0.71 μM, for 83 & 84, respectively). Similarly, the replacement of the methyl group of 82 with an ethyl substituent led to compound 85 (Table 13) displaying an almost unchanged inhibitory potency. With regard to the selectivity over hLDH1, compounds 82–85 demonstrated IC50 values of approximately 2–3 μM on this isoform, so they are quite selective for isoform 5.

Table 13.

Genentech (CA, USA) dihydropyrimidine-based inhibitors: activity data on human LDH5.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Structure | IC50 (μM) hLDH5 | ||

| R1 | R2 | R3 | ||

| 81 | H | Cl | H | 8.8 |

| 82 | Me | Cl | H | 0.48 |

| 83 | Me | Cl | Cl | 0.75 |

| 84 | Me | Cl | F | 0.71 |

| 85 | Et | Cl | H | 0.65 |

hLDH: Human LDH.

Data taken from [102].

The x-ray structure (PDB code: 4JNK) of hLDH5 complexed with compound 83 (the R enantiomer was present in the crystal structure) illustrated that the molecule was located in close proximity to several residues that are involved in the catalytic process of the enzyme, but it did not form any direct interactions with them. Rather, this compound was involved in hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with other different residues of the protein. Compound 83 made some interactions with NADH, which was present in the crystal structure, and also with several crystallographic water molecules. Unfortunately, compounds 82–84 did not demonstrate any activity in cell culture experiments, since they were not able to reduce the production of lactate even at a high concentration (50 μM), probably because of their poor cell membrane permeability and high protein binding. Unfortunately, the effect of chirality on the inhibition potency of 82–85 was not further investigated, although the enantiomer included in the complex with the enzyme found in the crystal structure displayed an (R)-configuration.

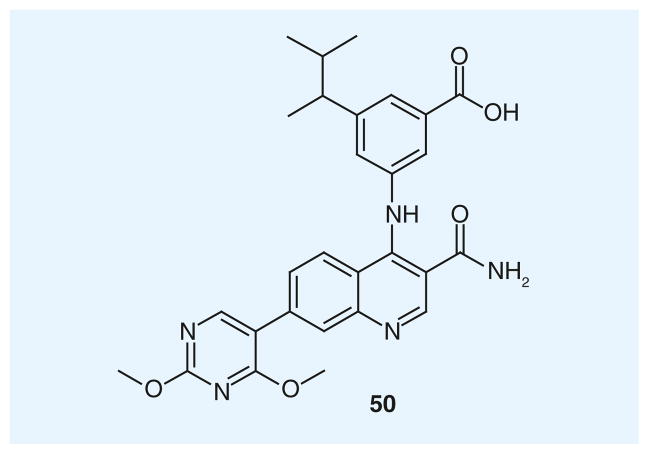

Compounds interfering with hLDH5 expression

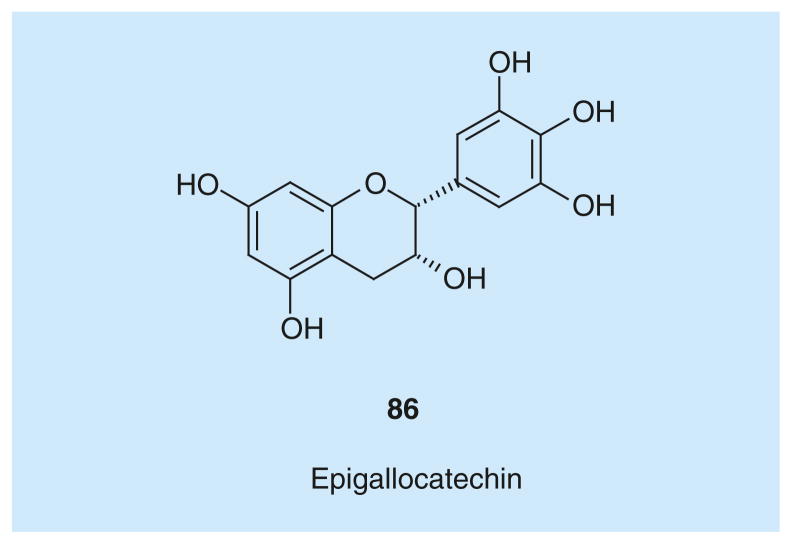

Natural polyphenolic compound epigallocatechin (86; Figure 6) was recently reported to interfere with hLDH5 expression and, consequently, to decrease hLDH5 activity [103].

Figure 6.

Epigallocatechin.

Epigallocatechin belongs to the family of catechins that are flavonoid compounds widely distributed in plants and fruits such as green tea. It is well known that catechin intake is beneficial for cancer prevention. For the first time, the anticancer effect of epigallocatechin has been associated with the inhibition of hLDH5. Moreover, epigallocatechin was identified as one of the main components of the common herbal medicine Spatholobus suberectus, which is used in Chinese medicine in cancer treatment, and its effects were investigated both in in vitro and in vivo models. The inhibition of hLDH5 by 86 in in vitro experiments is not due to a direct interaction with the enzyme, but seems to be related to a diminished expression of the enzyme. In detail, compound 86 promotes the dissociation of protein Hsp90 from HIF-1α, which is an inducer of LDH-A expression leading to the production of hLDH5. Consequently, HIF-1α is directed towards proteasome degradation and this may lead to a decreased hLDH5 cellular activity. Overall, the reduction of hLDH5 expression caused by 86 resulted in a sensible inhibition of breast cancer growth in animal xenografts, and was proved to trigger apoptosis without causing relevant toxic side effects.

Future perspective

The possibility whether inhibitors of hLDH5 may be clinically utilized as anticancer agents in the near future or not still remains an unanswered question. For sure, there is an extraordinary growing interest for any potential target involved in the altered glucose metabolism, which is associated to invasive tumor phenotypes. Among these targets, LDH definitely occupies an optimal checkpoint, since it is placed at the ‘pyruvate bifurcation point’ of the glycolytic pathway, a position where therapeutic inhibition is highly preferable to the other steps in order to obtain a selective starvation of cancer cells, which preferentially rely on lactate fermentation, and contemporarily spare normal cells, which instead direct pyruvate towards exhaustive oxidation by OXPHOS. Therefore, this enzyme would be an ideal target for antiglycolytic therapeutic strategies against invasive neoplastic diseases. On the other hand, hLDH5 has so far proved to be quite a ‘tough’ target, which has been considered as ‘nondruggable’ in some instances. As a matter of fact, considering the largely polar nature and small size of its substrate site, together with the long distance between the adenine and nicotinamide sites, the search for potent hLDH5 inhibitors had often led to the production of highly polar, elongate and ‘obese’ molecules, which are not able to cross the cell membrane and therefore are devoid of any significant cellular activity. In the near future, we will probably see a progressive increase of newly reported small molecules able to inhibit hLDH5 with better drug-like properties and, hopefully, some of them might reach the clinic by the next decade.

Due to their mechanism of action and to the high heterogeneous nature of most cancer phenotypes, the most suitable therapeutic application of hLDH5 inhibitors would be in combination with other anticancer drugs acting by different mechanism of actions, rather than being administered as single agents. Hence, we expect them to be considered in the future as ‘antirelapse’ additives to standard chemotherapeutic regimens, which have the potential of bringing a major breakthrough in the fight against cancer.

Executive summary.

Background

Many tumors develop hypoxic areas and acquire an aggressive phenotype, which is characterized by a high degree of invasiveness and resistance to conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Unlike healthy tissues, their main feature is a common metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis and the upregulation of proteins involved in the maintenance and growth of the tumor.

Role of human LDH5

Human LDH5 (hLDH5) converts the end product of glycolysis, pyruvate, to lactate and it supports the maintenance of glycolytic activity even when the oxidative metabolism of pyruvate is not possible. As a consequence, hLDH5 plays a critical role in the metabolic reprogramming of tumor cells and it represents an important contributor to the metabolic alterations required for the growth and proliferation of certain tumors.

hLDH5: a promising antiglycolytic target

In the area of anticancer treatment, inhibition of hLDH5 is currently emerging as an attractive and potentially safe approach to disrupt the energy supply in tumor cells.

hLDH5: a challenging enzyme

Targeting hLDH5 has been a quite unexplored approach so far, because few clinical uses have been identified. Moreover, hLDH5 inhibition presents many challenges: the substrate-binding site is very narrow and it is very polar with many positively charged residues, whereas the cofactor binding region is extended and the natural cofactor NADH binds to the enzyme with the nicotinamide and adenosine portions at the two ends of this site.

Origin of the first hLDH5 inhibitors

The first developed hLDH5 inhibitors were originally designed to bind the malarial isoform Plasmodium falciparum-LDH, but they were highly unspecific, since these molecules also display a certain inhibition of hLDH5, which was initially considered as a side effect.

Bifunctional inhibitors of hLDH5

Recent advances in the discovery of hLDH5 inhibitors highlight the potentiality of developing bifunctional inhibitors that are molecules able to bind both the cofactor and substrate-binding regions of the enzyme active site, as demonstrated by many recent successful examples.

Key Terms

- Oxidative phosphorylation

Mitochondrial metabolic process producing ATP as a result of the oxidation of cofactors NADH or flavin adenine dinucleotide-H2 by molecular oxygen. During this process glucose is completely oxidized to carbonic anhydride and water, producing up to 36 ATP molecules per glucose unit

- Glycolysis

Cytosolic multistep metabolic pathway converting intracellular glucose to pyruvate, generating two molecules of ATP and NADH from one molecule of glucose

- Warburg effect

Large increase in aerobic glycolysis, ending with massive production of lactic acid by the lactate fermentation, which is found in most tumor cells, regardless of the oxygen content or the mitochondrial functional status

- Hypoxia

Condition characterized by low oxygen concentrations (typically of 0.1–2.0% in the gas phase), as opposed to normoxia (>10%) or anoxia (~0%)

- Lactate fermentation

Cytosolic metabolic process by which glycolysis product pyruvate is converted by LDH into lactic acid, with the production of oxidized cofactor NAD+

- Dehydrogenase

Enzymes that catalyze the oxidation of substrates by a hydride transfer to electron acceptors, such as cofactors NAD+, NADP+, flavin mononucleotide or flavin dinucleotide

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7-PEOPLE-2011- IIF 299026, ‘LACTA-BLOCK’) under grant agreement n° PIIF-GA-2011–299026, from the US NIH (Grant NIHR01GM098453), and from the University of Pisa (Institutional Intramural Research Funds) are gratefully acknowledged. C Granchi and F Minutolo are co-inventors of patents owned by the University of Pisa covering inhibitors of LDH and of cellular lactate production. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

■ of interest

■■ of considerable interest

- 1.Romero-Garcia S, Lopez-Gonzalez JS, Báez-Viveros JL, Aguilar-Cazares D, Prado-Garcia H. Tumor cell metabolism: an integral view. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12(11):939–948. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.11.18140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kroemer G, Pouyssegur J. Tumor cell metabolism: cancer’s Achilles’ heel. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(6):472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123(3191):309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koppenol WH, Bounds PL, Dang CV. Otto Warburg’s contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(5):325–337. doi: 10.1038/nrc3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JW, Gao P, Dang CV. Effects of hypoxia on tumor metabolism. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26(2):291–298. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]