Summary

Proteolysis of the β C-terminal fragment (β-CTF) of the amyloid precursor protein generates the Aβ peptides associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Familial mutations in the β-CTF, such as the A21G Flemish mutation, can increase Aβ secretion. We establish how the Flemish mutation alters the structure of C55, the first 55-residues of the β-CTF, using FTIR and solid-state NMR spectroscopy. We show that the A21G mutation reduces β-sheet structure of C55 from Leu17 to Ala21, an inhibitory region near the site of the mutation, and increases α-helical structure from Gly25 to Gly29, in a region near the membrane surface and thought to interact with cholesterol. Cholesterol also increases Aβ peptide secretion, and we show that the incorporation of cholesterol into model membranes enhances the structural changes induced by the Flemish mutant suggesting a common link between familial mutations and the cellular environment.

The amyloid precursor protein (APP) is an integral membrane protein with a single transmembrane (TM) domain that is expressed in a wide number of different cell types including neurons (Selkoe, 2004). Processing of APP occurs by the sequential action of several proteases. α- and β–secretase first cleave between the extracellular and the TM domains of APP to generate an N-terminal soluble fragment (soluble αAPP or soluble βAPP) and a membrane-anchored C-terminal fragment (α- or β-CTF). The γ-secretase complex cleaves the CTFs within their TM domains. The cleavage of the β-CTF generates predominantly the Aβ40 peptide, but both shorter and longer Aβ peptides are also produced. The major longer peptide generated, Aβ42, has a higher propensity to form aggregates than the shorter isoforms and is the most toxic peptide generated by γ-cleavage (Burdick et al., 1992).

Three clusters of familial Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) mutations in APP are located close to the α, β and γ-cleavage sites, respectively. Specific mutations within these clusters influence the proteolytic processing of APP to favor increased Aβ42 production over the shorter Aβ peptides, or to favor an increase in the total production of Aβ peptides. The substrate numbering is based on the APP695 isoform of APP. Asp597 corresponds to the first residue (i.e. Asp1) of the β-CTF (Fig. 1A).

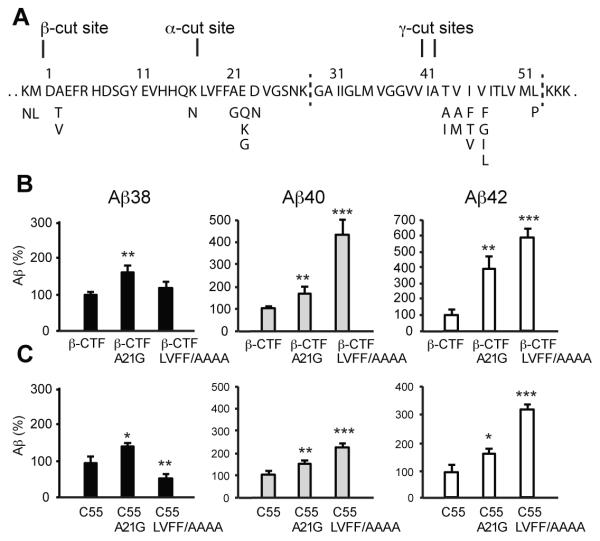

Fig. 1.

Increase of Aβ secretion in the A21G and LVFF-to-AAAA mutations. (A) Sequence of the extracellular and TM regions of the β-CTF. The β-CTF is produced by β-secretase cleavage of APP. The first 28 amino acids form the extracellular region of the β-CTF and contain the α-secretase cleavage site. The TM domain (denoted by vertical dashed lines) contains the site of γ-secretase cleavage. Both the extracellular and TM regions contain sites of familial AD mutations, shown as the single-letter amino acids below the sequence. (B) Comparison of the levels of Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42 produced by γ-secretase cleavage of the WT β-CTF, A21G and LVFF-to-AAAA mutants. (C) Comparison of the levels of Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42 produced by γ-secretase cleavage of WT C55 and the corresponding A21G and LVFF-to-AAAA mutants. Statistical significance was evaluated by One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test.Values are the means ± S.E., n > 5; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, compared with control. See also Figure S1.

A fourth cluster is located a few residues below the α-secretase cleavage site at K16-L17. This cluster is comprised of the A21G (Flemish), E22Q (Dutch), E22G (Arctic), E22K (Italian), and D23N (Iowa) mutations (Grabowski et al., 2001; Hendriks et al., 1992; Kamino et al., 1992; Levy et al., 1990), which have very different effects on APP processing (De Jonghe et al., 1998) and Aβ peptide aggregation. The A21G mutation appears to increase Aβ production by ~2-4 fold, but not via a change in α-secretase cleavage (De Jonghe et al., 1998; Tian et al., 2010). In contrast, mutations at E22 and D23 do not markedly change the level of total secreted Aβ peptides (De Jonghe et al., 1998; Tian et al., 2010), but rather increase the rate of fibril formation after the Aβ peptides are generated by proteolysis. To understand the diversity of effects within this central cluster of mutations midway between the β and γ cleavage sites, we focus here on the A21G Flemish mutation and address how the removal of a single methyl group can have such a dramatic influence on Aβ production.

Several residues surrounding the A21G mutation have been found to influence APP processing, although they are not associated with early-onset AD. Yi and colleagues (Tian et al., 2010) found that the L17-V18-F19-F20-A21 sequence is part of an inhibitory motif that modulates γ-secretase processing. Upon deletion of this motif, the catalytic efficiency of γ-secretase increases 25-fold compared to the full-length β-CTF. They suggested that the A21G mutation might disrupt the inhibitory effect of this region, implying that the interaction between APP and γ-secretase is altered upon mutation. In contrast, mutations in the G25-S26-N27-K28 region, which is a few residues C terminal to position 21, induce the opposite effect. Ren et al. (Ren et al., 2007) found that mutations at Ser26 and Lys28 reduce secreted Aβ40 and Aβ42 without a corresponding loss of the AICD cleavage product. Golde and colleagues (Kukar et al., 2011) found that the K28A and K28Q mutations shift the major cleavage site to the position of Gly33 from Val40. These results suggest that the precise nature and location of the border region between the extracellular and TM domains can exert a substantial effect on the position of γ-cleavage within the TM domain.

The structure of the non-mutated 99-residue β-CTF (also referred to as C99) was determined in detergent micelles by solution NMR spectroscopy (Beel et al., 2008). Helical structure was observed in the L17-V18-F19-F20 (or LVFF) sequence, the hydrophobic TM domain and in the last ~10 residues of the cytoplasmic sequence. The LVFF region is of particular interest because of its possible role as an inhibitory motif (Tian et al., 2010), and as a key element in amyloid plaque formation by the Aβ peptides (Inouye et al., 2010). An open question is whether structural changes are induced in the β-CTF upon the A21G mutation.

The A21G mutation may also influence the ability of the β-CTF to associate as TM homodimers. Glycines are abundant in TM helices of membrane proteins and the GxxxG sequence is well known to be a dimerization motif (Lemmon et al., 1992). The TM region of APP is unusual in containing three consecutive GxxxG motifs. The A21G mutation generates a fourth consecutive upstream motif, which raises the possibility that the mutation influences TM helix dimerization. Several studies have targeted these GxxxG sequences and found that mutations alter processing of the β-CTF (Kienlen-Campard et al., 2008; Munter et al., 2007).

In addition, a cholesterol-binding site was identified in the juxtamembrane (JM) region of the β-CTF between the extracellular and TM domains (Barrett et al., 2012). As with the A21G mutation, the presence of cholesterol and cholesterol-rich domains were linked to γ-secretase activity and the level of secreted Aβ (Beel et al., 2008). NMR measurements show that residues that appear sensitive to cholesterol binding include Phe20, Glu22 and Gly33. Phe20 is the last residue in the LVFF sequence. Glu22 is part of the cluster of familial mutations described above. Gly33 is part of the third GxxxG motif that has been implicated in mediating TM helix dimerization of the β-CTF . Depletion of cholesterol inhibits γ-secretase and Aβ secretion, while addition of cholesterol enhances γ-secretase activity (Simons et al., 1998; Wahrle et al., 2002).

In this study, we focus on the structural changes arising from the A21G mutation and compare the changes with those caused by an increase in membrane cholesterol. We first measure how the A21G and surrounding mutations influence processing of APP and the β-CTF, and confirm that the A21G mutation increases secreted Aβ by γ–secretase cleavage. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and NMR measurements are made on C55, corresponding to the first 55 residues of the β-CTF, which includes the extracellular sequence, TM domain, and a cluster of intracellular positive charges. The measurements are carried out in model membrane bilayers in which we can modulate the amount of cholesterol. These studies address the structure of C55, the structural changes induced by the A21G mutation and whether the presence of cholesterol in membrane bilayers acts synergistically with the A21G mutation.

Results

A21G and LVFF-to-alanine mutations both lead to an increase in Aβ production

We first confirm that the A21G mutation results in an increase in Aβ production and then address whether mutations within the upstream LVFF sequence result in comparable changes in processing. Measurements were made using C55 and the β-CTF expressed in Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells. Measurements on full length APP are shown in Fig. S1.

Secreted Aβ peptides (Aβ38, Aβ40, and Aβ42) were measured after transfection by multiplex electrochemiluminescence (ECLIA) assays. Proteolysis of the WT β-CTF results predominantly in the Aβ40 peptide (85%), with smaller amounts of Aβ38 (10%) and Aβ42 (5%). Fig. 1B shows the level of secreted Aβ peptides produced by γ-secretase cleavage as a percentage relative to WT. Both the A21G mutation and the LVFF to AAAA mutation increase total Aβ production. The A21G mutation results in a 1.7-fold increase in Aβ40. A larger increase (4.5-fold) is observed in Aβ40 for the LVFF to AAAA mutation. There is a striking increase (4-fold) in Aβ42 produced relative to WT in the A21G mutant. In contrast to the increase of Aβ40 and Aβ42 with the A21G and LVFF/AAAA mutations, the level of Aβ38 increases for the A21G but not LVFF/AAAA mutation.

We further compared the influence of the A21G and LVFF-to-AAAA mutations using C55. Several shorter versions of the β-CTF have previously been shown to function as γ-secretase substrates (Funamoto et al., 2004; Yin et al., 2007). C55 is the C-terminal truncated version of C99, and includes the extracellular and TM regions of the protein. In our structural studies, we used C55 rather than the full-length C99 protein to allow selective incorporation of 13C probes for structural studies. In Fig. 1C, we show that both the A21G and the LVFF to AAAA mutations increase Aβ secretion. The changes in Aβ secretion using C55 are similar to those using the full β-CTF, supporting its use as a model γ-secretase substrate.

The LVFF sequence is predominantly β-sheet in membrane bilayers

The processing results show that the extracellular A21G mutation strongly promotes Aβ production with both C55 and C99. To address whether there are structural differences between WT C55 and C55 with extracellular mutations, we measured the global secondary structure of C55 reconstituted into model membrane bilayers using FTIR spectroscopy.

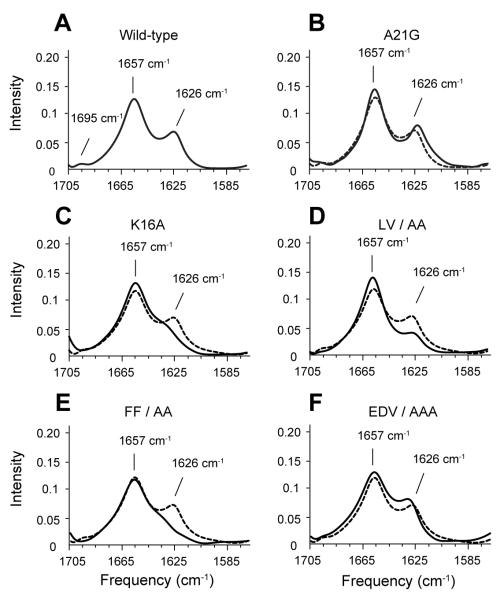

The amide I vibration (1600 – 1700 cm−1) is a sensitive marker of secondary structure. Fig. 2A presents the amide I region of WT C55 in dimyristoyl-phosphocholine (DMPC): dimyristoylphosphoglycerol (DMPG) bilayers. The FTIR spectrum exhibits both an intense band at 1657 cm−1 corresponding to α-helical structure and a weaker band at 1626 cm−1 corresponding to β-strand or β-sheet structure. Comparison of the FTIR spectrum of C55 with that of a TM peptide having a truncated extracellular domain (Sato et al., 2009) argues that the 1626 cm−1 band arises from the extracellular region of C55 (Fig. S2). To determine which residues are responsible for the 1626 cm−1 band, we mutated the KLVFF and EDV sequences that bracket A21. Mutations of K16 and F19-F20 reduce the 1626 cm−1 intensity consistent with a disruption or reduction of the β-strand secondary structure (Fig. 2). In contrast, the mutation of the E22-D23-V24 sequence does not strongly influence the 1626 cm−1 intensity. These results argue that the extracellular region upstream of A21 folds into β-structure. Comparable results are obtained from FTIR studies on the full-length β-CTF in the wild-type, A21G and LVFF mutant (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

FTIR spectroscopy of WT C55 and mutants. Comparison of FTIR spectra of WT C55 (A) reconstituted into DMPC:DMPG bilayers with spectra of the C55 protein containing the A21G mutation (B) and alanine mutations at K16 (C), L17-V18 (D), F19-F20 (E), and E22-D23-V24 (F). For comparison, FTIR spectra of unlabeled WT C55 are presented in dashed lines in panels (B)-(F). See also Figures S2 and S3.

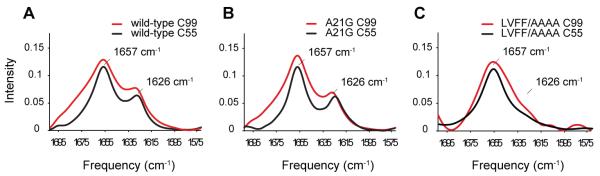

Fig.3.

Comparison of C55 and C99 in DMPC:DMPG bilayers. (A) Both C55 (black) and C99 (red) exhibit resonances characteristic of α-helix (1657 cm−1) and β-sheet (1626 cm−1). The C-terminal 44 residues of C99 are thought to be unstructured and consequently contribute to an overall broadening of the amide I resonances. (B) A21G does not significantly influence the FTIR spectra of C55 and C99. (C) In contrast to the A21G mutation, the LVFF-to-AAAA mutation removes the 1626 cm−1 β-sheet resonance. The disruption of the 1626 cm−1 resonance in both C55 and C99 by the LVFF-to-AAAA mutation is consistent with this region folding into β-sheet secondary structure, which is in disagreement with the solution NMR structures (Barrett et al., 2012; Beel et al., 2008; Nadezhdin et al., 2012) using detergent systems.

Integration of the 1626 cm−1 peak suggests the β-sheet structure is formed by ~6-8 residues suggesting that several additional residues may be involved in β-sheet formation. The small 1695 cm−1 resonance observed for WT C55 is often associated with anti-parallel β-sheet (Paul et al., 2004), and the loss of this peak upon mutation of the LVFF sequence suggests that this region adopts an anti-parallel β-sheet fold. One possibility is that the KLVFFAE sequence forms anti-parallel β-sheet through intermolecular interactions. Additional experiments are in progress to test this possibility, as well as the alternative that residues in the region N-terminal to KLVFF fold back and form β-sheet through intramolecular interactions.

Earlier solution NMR studies of the full β-CTF and shorter fragments show helical structure of the LVFF sequence (Beel et al., 2008; Nadezhdin et al., 2012). Our observation of β-structure within the LVFF sequence argues that this region adopts a different secondary structure in membrane bilayers than in detergent/lipid mixtures and detergent micelles (Beel et al., 2008; Nadezhdin et al., 2012). To test whether detergent interactions induce helical secondary, we compared FTIR spectra of C55 in membrane bilayers, detergent micelles and in bicelles that have been titrated from bilayer-like structures (q=2.0) to isotropic detergent-like structures (q=0.2) (Fig. S3). Both the titration of bicelles toward a more detergent-like environment or direct comparisons of C55 in bilayers and detergent micelles show a loss of β-sheet structure characterized by the 1626 cm−1 amide I vibration with added detergent.

The A21G mutation influences the β-sheet structure in membrane bilayers

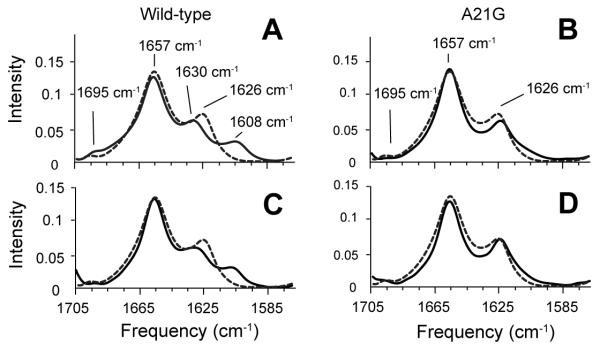

The A21G mutation has only a slight influence on the position of the 1626 cm−1 band observed in the FTIR spectrum of C55 (Fig. 2B). To further explore whether there are local changes in structure, we compared FTIR spectra of WT and A21G C55 peptides containing specific 13C labels at backbone C=O positions within the LVFF sequence. The 13C=O labels shift the amide vibration to lower frequencies. The frequency and intensity of the shifted resonances are sensitive to whether the 13C=O labeled sites fall within parallel or antiparallel β-sheet structure (Paul et al., 2004; Petty and Decatur, 2005). We selected F19 and F20 for labeling since mutations at these positions have a large influence on the 1626 cm−1 resonance. For WT C55 (Figs. 4A, C), the incorporation of 13C leads to splitting of the 1626 cm−1 band into two components at 1608 cm−1 and 1630 cm−1. These shifts are similar to those described for the KLVFFAED octapeptide (Fig. S4), which forms fibrils with β-strands in an antiparallel orientation (Balbach et al., 2000). In contrast, 13C-labeling does not cause the β-sheet peak to split in the A21G mutant (Figs. 4B and D) suggesting that the anti-parallel structure observed at positions F19 and F20 has been disrupted or altered. Previous studies have shown that the extent of splitting and intensity is dependent on the position of the 13C=O label. For example, Axelsen and colleagues (Paul et al., 2004) found that C=O groups at the edge of β-sheet and not involved in hydrogen bonds had higher frequencies and reduced intensity compared to hydrogen bonded C=O groups within β-sheet. As a result, we conclude that A21 is at the edge of the β-sheet structure formed (in part) by the LVFF sequence, and attribute the weak intensity at ~1610 cm−1 in the A21G mutant to the 13C=O carbonyls of F19 and F20.

Fig. 4.

Influence of 13C=O labeling on the amide I vibration of WT and A21G C55. FTIR spectra are shown of WT C55 (A,C) and the A21G mutant (B,D) containing 13C=O labels at F19 (A,B) and F20 (C,D). Spectra of unlabeled WT C55 are shown in dashed lines in panels (A)-(D) for comparison. The incorporation of 13C=O labels at F19 and F20 only influences the 1626 cm−1 band of WT C55. The C55 peptides were reconstituted in DMPC:DMPG bilayers. See also Figure S4.

The A21G mutation increases the helical character of the G25SNKG29 sequence

Solid-state NMR is complementary to FTIR spectroscopy and allows us to probe local structure. Fig. 5 presents the results from 2D magic angle spinning NMR spectra of C55 obtained with dipolar assisted rotational resonance (DARR). Figs. 5A-D show selected rows from the 2D spectra corresponding to the 13C=O resonances of F19, F20, G29 and A30. Comparison of the WT C55 (black) and A21G (red) spectra illustrates that the A21G mutation induces distinct changes in chemical shift at some positions, but not others.

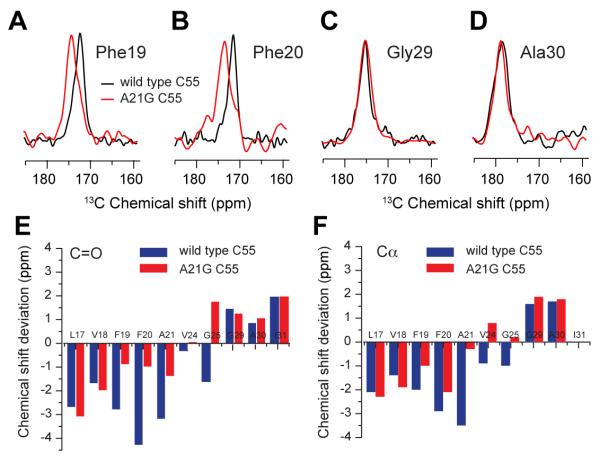

Fig. 5.

Comparison of 13C NMR chemical shifts between WT and A21G C55. Overlap of the carbonyl region of WT C55 (black) and the A21G mutant (red) labeled with U-13C F19 (A), U-13C F20 (B), U-13C G29 (C) and U-13C A30 (D). The A21G mutation leads to higher chemical shift values in the 13C=O carbonyl resonances of the adjacent F19 and F20 residues, but not G29 and A30. Spectra correspond to rows taken through the Cα diagonal resonance. Carbonyl (E) and Cα (F) carbon chemical shifts are plotted relative to their average values obtained from the BMRB database (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu/ref_info/statful.htm). See also Table S1.

Figs. 5E, F and Table S1 summarize the chemical shifts of selected Cα and C=O resonances between L17 and I31. The chemical shifts are plotted as differences from the average residue chemical shifts. Deviations to lower chemical shift values correspond to β-sheet secondary structure. Deviations to higher chemical shift values correspond to α-helical secondary structure. For WT C55, the Cα and C=O resonances between L17 and A21 all exhibit negative deviations corresponding to β-strand or sheet structure. The observation of β-structure is consistent with the FTIR results, but contrasts with solution NMR structures previously determined of this region (Beel et al., 2008; Nadezhdin et al., 2012). Mutation to A21G results in less negative deviations of both the Cα and C=O chemical shifts for residues F19-A21 suggesting that there is a reduction in β-structure. G29 and A30 both exhibit positive deviations consistent with the helical TM domain beginning at K28. Mutation to A21G does not alter these latter chemical shifts. The two residues probed between the LVFF region and the TM domain – V24 and G25 – exhibit negative shifts in WT C55 and positive shifts in the A21G mutant, suggesting a shift in local secondary structure to α-helix.

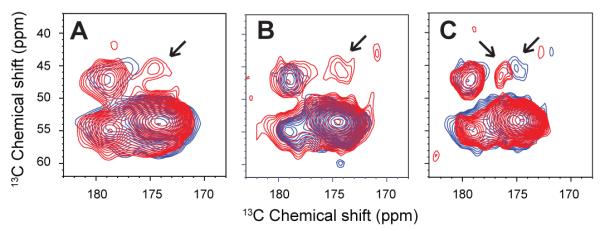

The conclusion that the region between G25 and G29 increases in helical structure in the A21G mutant is supported by DARR NMR measurements between these two residues. Fig. 6A presents DARR NMR spectra of the WT (black) and A21G C55 (red) peptides 13C labeled at G25 and G29. The distance between the 13C=O and 13Cα carbons is ~5.3 Å, which is within the ~6 Å DARR distance range when this region is α-helical. However, this distance is considerably longer (~12-13 Å) in an extended conformation. Comparison of the two spectra shows the appearance of the cross peak (arrow) correlating the G25 13C=O and G29 13Cα resonances in the A21G mutant. The appearance of the G25 13C=O to G29 13Cα cross peak is consistent with the stretch of amino acids between these residues folding into helical structure in the A21G mutant.

Fig. 6.

13C DARR NMR measurements between G25 and G29 in WT and A21G C55. Regions of the 2D DARR NMR spectra are shown corresponding to C=O to Cα crosspeaks. In (A), WT (blue) and A21G (red) C55 containing 13C-labels at G25 (13C=O) and G29 (13Cα) were reconstituted into DMPC:DMPG bilayers. An interresidue cross peak (arrow) between these 13C sites is only observed for the A21G mutant and corresponds to the formation of helical secondary structure. (B) DARR NMR measurements on WT C55 in POPC:POPS (blue) and WT C55 in POPC:POPS:cholesterol (red) using the same G25 (13C=O) and G29 (13Cα) labeled peptide as in (A). (C) DARR NMR measurements on WT C55 (blue) and A21G C55 (red) peptide in POPC:POPS:cholesterol bilayers. Upon addition of cholesterol, the cross peak is observed for both the WT and mutant peptides. The spectra are scaled to the strong 1,2 -13C L17 cross peak at 173 ppm corresponding to directly bonded carbons, which is not expected to change intensity in these spectra. See also Figure S6.

The familial E22Q and D23N mutations do not markedly influence the extracellular β-sheet structure

For comparison to A21, we studied the adjacent two positions (E22 and D23), which are also sites of familial AD mutations, using FTIR and MAS NMR. In FTIR measurements of C55 containing either the E22Q or D23N mutations (Fig. S5C and D), the incorporation of 13C=O at F19 leads to a splitting of the 1626 cm−1 band as in WT C55. In MAS NMR measurements (Fig. S5G and H), 13C=O labeling at F19, V24 and G25 in E22Q or D23N C55 also yields spectra similar to WT C55, and not the large chemical shift changes observed in the A21G mutant.

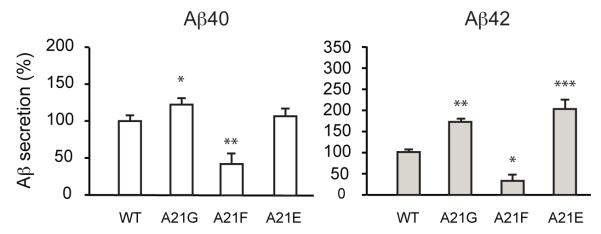

These observations highlight the critical position of A21. Mutation of the LVFF sequence just N-terminal to A21 can decrease the β-sheet structure in the extracellular domain and decrease Aβ secretion. In contrast, mutations just C-terminal to A21 do not significantly influence C55 structure or Aβ processing. These studies agree with previous results showing that A21G exhibits distinct phenotypes from familial mutations at E22 and D23 (De Jonghe et al., 1998; Tian et al., 2010). To further test the idea that the influence of the A21G mutation is similar to that of mutations in the LVFF sequence rather than in the ED sequence, we measured Aβ secretion in a series of A21 mutants. In Fig. 7, we show that extension of the LVFF sequence with an A21F substitution reduces Aβ40 and Aβ42 secretion, whereas extension of the E22-D23 sequence with an A21E substitution increases Aβ secretion similar to the observation in the A21G mutant.

Fig. 7.

Influence of β-CTF processing upon substitution of Ala21 with aromatic and charged residues. The A21F mutation reduces Aβ40 and Aβ42 production. This mutation replaces A21 with a hydrophobic phenylalanine identical to the last residue in the upstream LVFF sequence, A21E increases both Aβ40 and Aβ42 secretion. The A21E mutation replaces A21 with a residue identical to the downstream Glu22. Values are the means ± S.E., n > 5; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, compared with control. See also Figure S5.

Dimerization of WT and A21G C55 is mediated by a GxxxG interface

In soluble proteins, glycines serve as both helix and β-sheet breakers. However in TM helices, glycines mediate helix dimerization (Lemmon et al., 1992). The TM region of APP is unusual in containing three consecutive GxxxG motifs. The A21G mutation generates a fourth consecutive GxxxG motif. The observation that the helical secondary structure increases in the region between G25 and G29 in the A21G mutant raises the possibility that the helical G25xxxG29 motif stabilizes a TM dimer of C55.

The dimer structure of the TM domain of APP has been reported in both detergent micelles (Nadezhdin et al., 2012) and in membrane bilayers (Sato et al., 2009). In DMPC:DMPG bilayers, the TM domain dimerizes via the G29xxxG33xxxG37 interface (Sato et al., 2009). In contrast, the G38xxxA42 sequence mediates dimerization in dodecylphosphocholine micelles (Nadezhdin et al., 2012). 2D DARR NMR experiments were designed to test if either of these dimer interfaces exists in WT C55 or in the A21G mutant. These experiments involve co-mixing of two different peptides where cross peaks in the 2D spectra are only observed between heterodimers. Specifically, 13C labels were selectively incorporated at G33 and A42 in two different C55 peptides (peptide 1 contains G33 13C=O and A42 13Cβ and peptide 2 contains G33 13Cα and A42 13C=O). In the heterodimer, the G33 residues are closely packed if the G33xxxG37 motif mediates dimerization, whereas the A42 residues are in close proximity if the G38xxxA42 motif mediates dimerization.

The two WT C55 (or the two 13C-labeled A21G C55) peptides were reconstituted into 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphocholine (POPC): 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphoserine (POPS) membranes in equimolar amounts. Fig. 8 presents the DARR NMR spectrum of WT C55 (black) overlaid with the spectrum of the A21G mutant (red). In both the WT and A21G C55 peptides, inter-peptide cross peaks are observed between G33 (13Cα) and G33 (13C=O) (red box), but not between A42 (13Cβ) and A42 (13C=O) (blue box). No intensity was observed at this position in DARR NMR spectra of the single peptides containing the G33 13C=O and A42 13Cβ labels alone or the G33 13Cα and A42 13C=O labels alone, and the cross peak was reduced with the addition of unlabeled peptide (not shown). The cross peak was only observed when the two peptides were mixed.

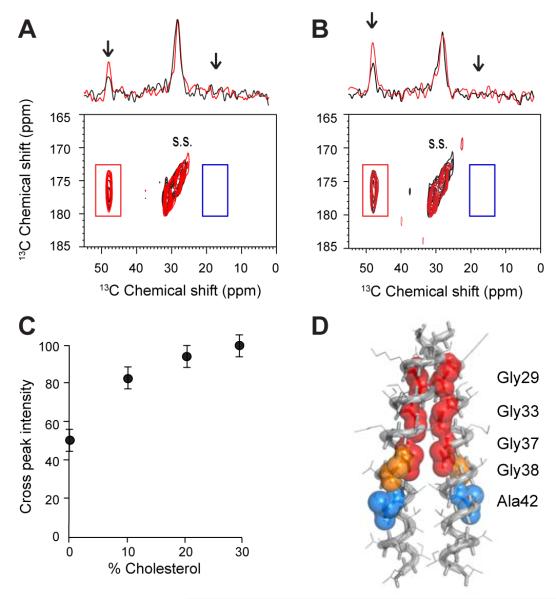

Fig. 8.

Interhelical 13C DARR NMR measurements of WT and A21G C55 reconstituted into POPC:POPS bilayers. Two WT C55 or two A21G C55 peptides were mixed in equal molar amounts to establish the dimer interface, either G29xxxG33xxxG37 or G38xxxA42. (A) 1D and 2D DARR NMR spectra of WT C55 (black) and A21G C55 (red) are overlapped. Only cross peaks resulting from G33 on different peptides (i.e. G33 Cα to G33 C=O) are observed. Cross peaks are not observed between A42 on different peptides (i.e. A42 Cβ to A42 C=O, blue box). (B) 1D and 2D DARR NMR spectra of WT C55 (black) and A21G C55 (red) are overlapped in POPC:POPS membranes with 30 mol% cholesterol. Rows are shown through the G33 C=O diagonal resonance. The resonance at ~26 ppm is a spinning side band and serves as an internal control for comparing relative intensity changes between spectra. (C) Influence of the G33 Cα to G33 C=O cross peak intensity on cholesterol content for A21G C55. The content of the cholesterol in POPC:POPS membranes was varied from 0-30%. (D) Molecular model of the C55 TM dimer mediated by the G29xxxG33xxxG37 interface (red). A42 (blue) is oriented away from the interface.

It is possible to relate the intensity of the cross peaks to the proportion of the peptide associating as dimers if one assumes that the packing interactions within the dimer structure are the same for WT C55 and the A21G mutant. In Fig. 8A, the cross peak intensity increases ~1.5 fold (relative to the spinning side band at ~26 ppm) suggesting that the Kd decreases for the A21G mutant of C55 compared to the WT sequence. Since dimerization is occurring within the membrane bilayer, it is possible to define a Kd in terms of the concentration of C55 (relative to the amount of lipid) that yields equal amounts of monomer and dimer (Song et al., 2013). If we assume that the cross peak intensity for dimer corresponds to that for C55 in cholesterol-containing membranes (Figs. 8B,C), we can estimate a Kd of ~2 mol% on the basis of the cross peak intensities observed in Fig. 8A. However, it is important to note that we cannot yet rule out that the increase in cross peak intensity results in a change in the dimer interface rather than a change in affinity. In either case, changes in the G33-G33 cross peak intensity show that a change within the structure of the extracellular domain of C55 can be transmitted down to the TM domain in the absence of the γ-secretase complex.

Cholesterol-rich bilayers increase the helicity of the TM domain of WT C55

Both familial mutations and environmental factors influence Aβ generation by γ-secretase. For example, a higher concentration of serum cholesterol has been statistically observed as a risk factor for AD (Kivipelto et al., 2001). Hypercholesterolemia leads to an increase in Aβ deposition and intraneuronal accumulation of toxic Aβ oligomers in transgenic mice (Umeda et al., 2012). NMR studies reveal that cholesterol interacts with the β-CTF at the JM boundary between the extracellular and TM domains in micelles or detergent/lipid mixtures (Barrett et al., 2012). On the basis of our observations in the A21G mutant, we investigated the possibility that cholesterol may influence the structure of the extracellular region of the β-CTF and enhance the structural changes induced by the A21G mutation.

To test the influence of cholesterol on the structure of the LVFF sequence, FTIR spectra are presented in Fig. S6 of C55 13C-labeled at F19. We observe a splitting of the 1626 cm−1 band as for the WT peptide in bilayers without cholesterol arguing that cholesterol does not influence the LVFF anti-parallel β-sheet structure. In contrast, the addition of cholesterol to POPC:POPS bilayers results in a 2.2 ppm downfield shift of the NMR 13C=O resonance of G25, although without influencing the carbonyl chemical shifts of F20 or G33, resonances observed to be sensitive to cholesterol in detergent (Beel et al., 2008). This observation is consistent with a shift to more helical structure in the region of G25.

The increase in helical secondary structure in the region between G25 and G29 is supported by intra-helical DARR NMR measurements. Fig. 6B presents the DARR spectra of WT C55 reconstituted in POPC:POPS (blue) and in POPC:POPS:cholesterol (red) using the same 13C labeling scheme as described above. In Fig. 6B, the cross peak between G25 13C=O and G29 13Cα is only observed in WT C55 upon the addition of cholesterol. The appearance of the G25-G29 cross peak in the A21G mutant or upon the addition of cholesterol in WT C55 indicates that both conditions induce TM helical structure of the C55 peptide.

The observation that both the A21G mutant and cholesterol addition result in a G25-G29 cross peak raises the question as to whether these two different mechanisms can act synergistically. Fig. 6C presents 2D DARR NMR spectra of the WT (blue) and A21G C55 (red) peptide in POPC:PS:cholesterol bilayers using the same 13C labeling scheme as above. The intensity of the cross peak of the A21G mutant is ~1.5-fold higher in the cholesterol containing membranes consistent with a synergistic effect.

We next investigated whether cholesterol influences the monomer-dimer equilibrium of the WT or A21G C55 peptides. Fig. 8B presents a comparison of the inter-helical G33-G33 dimer cross peak upon the incorporation of cholesterol into POPC:POPS membranes. Rows highlighting the interhelical G33 (13Cα) -G33 (13C=O) cross peak at 46.2 ppm are shown for WT C55 (black) reconstituted into POPC:POPS:cholesterol bilayers and for the A21G mutant (red) reconstituted into POPC:POPS:cholesterol bilayers. The cross peak intensity for WT C55 with cholesterol is approximately the same as that for the A21G peptide without cholesterol in POPC:POPS membranes, suggesting that the monomer-dimer equilibrium is approximately the same. When the A21G mutant is incorporated into POPC:POPS:cholesterol membranes (red), the cross peak intensity increases ~2-fold, consistent with a synergistic effect of A21G and cholesterol. Fig. 8C illustrates the influence of cholesterol on the G33-G33 cross peak intensity as cholesterol is increased in POPC:POPS bilayers from 0 to 30 mol%. As discussed for the A21G mutation, the increase in cross peak intensity may be due to a change in conformation rather than affinity. However, both A21G and cholesterol appear to have the same influence on TM interactions.

Discussion

The A21G mutation has a strong influence on intramembranous processing by the γ-secretase complex. We address how the loss of a single methyl group alters the structure of the extracellular region and TM domain using FTIR and NMR spectroscopy, and propose how these changes are linked to processing of the β-CTF. FTIR and NMR measurements of C55 in bilayers provide evidence that β-strand secondary structure is adopted in the extracellular region of the β-CTF and that the A21G mutation influences the upstream LVFF sequence (particularly F19 and F20) and the downstream GSNKG sequence with a small effect on TM dimerization. These data emphasize the ability of glycine to destabilize β-sheet structure (Minor and Kim, 1994) and to stabilize TM dimers through GxxxG motifs (Lemmon et al., 1992).

The structure of APP near the region of A21G regulates processing

The Flemish mutation was first described by Hendriks et al. (1992) and later shown to increase Aβ production by ~2-fold (De Jonghe et al., 1998). Yi and colleagues (Tian et al., 2010) found that the extracellular LVFFAED sequence was inhibitory to the activity of γ-secretase. They observed that deletion of this sequence resulted in a 10-fold increase in secreted Aβ40. To more directly test the role of the LVFF sequence in regulating Aβ secretion, we substituted the LVFF sequence with four alanine residues and found that the mutation increases Aβ secretion (Aβ40 and Aβ42) ~4.5-fold, considerably less than the increase observed when the sequence is deleted, but much greater than the ~1.7 fold increase due to the A21G mutation (Fig. 1).

Our studies suggest that A21 is at the edge of the β-sheet fold in the extracellular domain of the β-CTF. The FTIR measurements reveal only modest changes in the 1626 cm−1 band upon mutation of A21 to glycine. In contrast, the A21G mutation results in large changes in the chemical shifts at F19, F20 and G25 consistent with unraveling of the β-sheet structure at the end of the LVFF sequence and the formation of helical secondary structure in the GSNKG sequence. Strikingly, mutation of A21, but not the adjacent E22 and D23 residues, induces structural changes in the LVFF and GSNKG sequences and an increase in Aβ. A21 appears to be at a breakpoint between a well-defined β-strand and the TM helix; extension of the LVFF sequence with an A21F substitution reduces Aβ secretion, whereas extension of the E22-D23 sequence with an A21E substitution increases Aβ secretion (Fig. 7).

The WT and A21G C55 dimerize through the GxxxG and not the GxxxA interface

The observation that the A21G mutation introduces an additional GxxxG motif into the β-CTF and that the G25xxxG29 sequence becomes more helical suggests that the A21G mutation influences TM dimerization. Mutation of the consecutive G29xxxG33xxxG37 motifs supports the idea that TM dimerization influences processing (Kienlen-Campard et al., 2008; Munter et al., 2007). Recently, the dimer structure of residues Q15- K53 was determined in detergent micelles (Nadezhdin et al., 2012). Surprisingly, the dimer interface in their NMR structure was formed from the G38xxxA42 sequence rather than G33xxxG37.

Above we show unambiguously that the A21G dimer is mediated by the G33xxxG37 interface. The strong G33 Cα and G33 C=O cross peak can only be explained by a well-defined dimer structure. The observation that the A21G mutation has only a small influence on the G33-G33 cross peak intensity implies the large influence of the mutation on processing is associated with the structural changes in the extracellular domain rather than with dimerization. These results support the conclusions of Tian et al. (2010) that the LVFFAED sequence is inhibitory.

The A21G mutation and cholesterol act synergistically

Many cellular factors appear to influence the overall level of secreted Aβ peptides and the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, including the presence of cholesterol (Beel et al., 2008; Simons et al., 1998; Wahrle et al., 2002). Upon the addition of cholesterol to model membranes, we observe an increase in α-helical secondary structure, and in the A21G mutant, a shift of the monomer-dimer equilibrium toward dimer or reorientation of the dimer interface to strength the G33-G33 contact. It is known that cholesterol increases the thickness of the bilayer, and we infer that this induces an increase in the helical structure between G25 and G29, in a fashion similar to that of A21G. In neuronal axons, the concentration of cholesterol is estimated to be ~15% (Calderon et al., 1995). These results suggest that dimerization is facilitated by the G25xxxG29 interface in A21G, and that cholesterol helps stabilize this interface. Together our studies and recent studies by Sanders and coworkers (Song et al., 2013) indicate that dimerization of the WT TM sequence of APP is weak, but can be modulated by protein concentration, mutation and the membrane environment.

The results on the A21G mutation and added cholesterol point to a simple model in which structural changes in the extracellular sequence (LVFFAEDVGSNK) sequence lead to a reduction of inhibitory interactions and influence dimerization. The nature of the inhibitory interactions may originate with interactions between the LVFF sequence and γ-secretase (Tian et al., 2010) or with the membrane surface (Beel et al., 2008). The convergence of results reveals that both mutational and environmental factors can induce conformational changes in γ-secretase substrates that have implications in AD.

Methods

Materials

13C-amino acids were obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). Detergents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and lipids from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Human APP-specific antibody (WO-2) was obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA). All cell culture reagents were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The plasmids used to express human APP695 or β-CTF in eukaryotic cells have been previously described (Kienlen-Campard et al., 2008). The different mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis according to manufacturer’s instructions (Quick-Change™, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Cell cultures and transfection

CHO cells were cultured in F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics at 37 °C and 5% CO2 and transfected 24 h after seeding as previously described (Kienlen-Campard et al., 2008). Western blotting was performed on cell lysates (10 μg protein). Membranes were incubated at 4 °C overnight with human APP-specific WO-2 monoclonal antibody (1:2000), washed and incubated with 1:10,000 secondary anti-mouse antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, followed by ECL revelation (Amersham, Uppsala, Sweden). Aβ production was monitored in the culture media 48 h after transfection (Kienlen-Campard et al., 2008). Briefly, samples were cleared by centrifugation (12,000 g, 3 min, 4 °C). Aβ38/Aβ40/Aβ42 and soluble APPα/β were quantified in 25 μl of cellular medium by multiplex ECLIA assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (MesoScale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD).

Peptide synthesis, purification and reconstitution of C55 into bicelles

C55 peptides (Asp1-Lys55) corresponding to the TM and JM regions of APP were synthesized by solid-phase methods (Keck Facility, Yale University). The purity was confirmed with MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and analytical reverse phase HPLC. For reconstitution into bicelles, the C55 peptides were refolded with 16 mM dihexoylphosphocholine (DHPC). The fractions containing purified protein were collected on the basis of the absorbance at 280 nm. The peptide to lipid ratio was 1:50 in bicelles with different q values (0.25, 0.35, 1.0, and 2.0) by adding proper amounts of lipids in the protein stock solutions. The samples of peptides reconstituted into bicelles were prepared by several cool-and-thaw cycles until the samples appeared clear.

Protein overexpression and purification

The C55 sequence was subcloned into a pET21a vector and expressed with an N-terminal methionine and a C-terminal linker plus His-tag (KLAAALEHHHHHH). The C55 protein was purified using a Nickel NTA column. Cell pellets were washed 3 times with the 35 ml of lysis buffer until the washed solution became clear. The pellets were then dissolved in 35 ml of urea/SDS buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 8 M urea, 0.2% SDS, pH 7.8) and mixed overnight at room temperature. The resulting solution was centrifuged at 25000 g for 20 min. The supernatants were pooled with the pre-equilibrium Nickel beads and mixed for 2 hours at room temperature. The beads were then washed with urea/SDS buffer and the proteins were eluted with 250 mM imidazole in Tris-buffered saline solution (pH 7.8) containing octyl-β-D-glucoside. The eluted fractions were collected and checked by SDS-PAGE. The protein purity was further confirmed with mass spectroscopy.

Reconstitution of C55 into bicelles

The C55 peptides were eluted from the Ni column and refolded with 16 mM dihexoylphosphocholine (DHPC) (Avanti lipids) in the elution buffer as described above. The fractions containing purified protein were collected on the basis of the absorbance at 260-280 nm. The peptide to lipid ratio was 1:50 in bicelles with different q values (0.25, 0.35, 1.0, and 2.0) by adding proper amounts of lipids in the protein stock solutions. The samples of peptides reconstituted into bicelles were prepared as described (Lu et al., 2012) by several cool-and-thaw cycles until the samples appear clear.

Reconstitution of C55 into membrane bilayers

The C55 peptides were cosolubilized with lipid and octyl-β-glucoside in hexafluoroisopropanol. The peptide:lipid molar ratio was 1:50 and the molar ratios between lipids were as follows: DMPC:DMPG, 10:3; POPC:POPS,10:3; or POPC:POPS:cholesterol, 10:3:5.6). The solution was incubated for 3 h at 30 °C, after which the solvent was removed under a stream of argon gas and then under vacuum overnight. MES buffer (5 mM MES, 50 mM NaCl, pH 6.2) was added to the solid from the previous step and gently mixed at 30 °C for 6 hours. The octyl-ß-glucoside was removed by dialysis (Smith et al., 2002). DMPC and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) are representative lipids with saturated and unsaturated fatty acyl chains, respectively, while the DMPG and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine (POPS) headgroups introduce an overall negative membrane charge similar to that in cellular plasma membranes. DMPC can be titrated with DHPC to convert from membrane bilayers to isotropic (detergent-like) bicelles. POPC is abundant in plasma membranes and exhibits a continuous transition from a liquid disordered state to liquid ordered state with the addition of cholesterol (London, 2005). In our studies, only small differences were observed in the FTIR and NMR spectra between C55 reconstituted into POPC:PS or DMPC:PG bilayers. The only marked differences were observed upon titration of cholesterol into the POPC:PS membranes.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

Polarized attenuated total reflection (ATR) FTIR spectra were obtained on a Bruker IFS 66V/S spectrometer. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy was used to characterize the global secondary structure, and the orientation of the TM domain of C55 in bilayers. The WT and A21G C55 peptides reconstituted in bilayers were layered on a germanium plate and bulk water removed by a slow flow of nitrogen gas. Similar dichroic ratios of the 1657 cm−1 band of 3.2-3.3 are observed for both peptides regardless of the lipid mixture used in these studies. The high dichroic ratio is consistent with an orientation of the TM α-helix of ~20° relative to the bilayer normal and indicates that both peptides can be reconstituted into bilayers by detergent dialysis.

Solid-State NMR spectroscopy

NMR experiments were performed at a 13C frequency of 125 MHz on a Bruker AVANCE spectrometer. The MAS spinning rate was set to 9-11 KHz (± 5 Hz). The ramped amplitude cross polarization contact time was 2 ms. Two-pulse phase-modulated decoupling was used during the evolution and acquisition periods with a radiofrequency field strength of 80 kHz. Internuclear 13C…13C distance constraints were obtained from 2D dipolar assisted rotational resonance (DARR) NMR experiments (Takegoshi et al., 2001) using a mixing time of 600 ms. The sample temperature was maintained at 198 K (± 2 K). 13C chemical shifts are referenced to external 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid (DSS).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The extracellular region of β CTF of APP folds into β-sheet.

The β-sheet structure in the β CTF inhibits processing of APP to the Aβ peptides.

The familial A21G mutation reduces β-sheet in the adjacent, inhibitory LVFF motif.

Cholesterol enhances the effects of the A21G mutation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (RO1-AG027317 to SOS), the Interuniversity Attraction Poles Programme-Belgian State-Belgian Science Policy (IAP P7-16 to JNO and PKC and IAP to SNC), a grant from the Alzheimer Research Foundation (SAO-FRMA to PKC) and support from Salus Sanguinis, Fondation contre le cancer, ARC Program of the Université catholique de Louvain, FRS-FNRS Belgium (to SNC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Balbach JJ, Ishii Y, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Rizzo NW, Dyda F, Reed J, Tycko R. Amyloid fibril formation by Aβ16-22, a seven-residue fragment of the Alzheimer’s β-amyloid peptide, and structural characterization by solid state NMR. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13748–13759. doi: 10.1021/bi0011330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett PJ, Song Y, Van Horn WD, Hustedt EJ, Schafer JM, Hadziselimovic A, Beel AJ, Sanders CR. The amyloid precursor protein has a flexible transmembrane domain and binds cholesterol. Science. 2012;336:1168–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.1219988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beel AJ, Mobley CK, Kim HJ, Tian F, Hadziselimovic A, Jap B, Prestegard JH, Sanders CR. Structural studies of the transmembrane C-terminal domain of the amyloid precursor protein (APP): Does APP function as a cholesterol sensor? Biochemistry. 2008;47:9428–9446. doi: 10.1021/bi800993c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts V, Leissring MA, Dolios G, Wang R, Selkoe DJ, Walsh DM. Aggregation and catabolism of disease-associated intra-Aβ mutations: reduced proteolysis of AβA21G by neprilysin. Neurobiol. Disease. 2008;31:442–450. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdick D, Soreghan B, Kwon M, Kosmoski J, Knauer M, Henschen A, Yates J, Cotman C, Glabe C. Assembly and aggregation properties of synthetic Alzheimer’s A4/β amyloid peptide analogs. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:546–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon RO, Attema B, Devries GH. Lipid composition of neuronal cell bodies and neurites from cultured dorsal root ganglia. J. Neurochem. 1995;64:424–429. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64010424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonghe C, Zehr C, Yager D, Prada CM, Younkin S, Hendriks L, Van Broeckhoven C, Eckman CB. Flemish and Dutch mutations in amyloid β precursor protein have different effects on amyloid β secretion. Neurobiol. Disease. 1998;5:281–286. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funamoto S, Morshima-Kawashima M, Tanimura Y, Hirotani N, Saido TC, Ihara Y. Truncated carboxyl-terminal fragments of β-amyloid precursor protein are processed to amyloid β-proteins 40 and 42. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13532–13540. doi: 10.1021/bi049399k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski TJ, Cho HS, Vonsattel JP, Rebeck GW, Greenberg SM. Novel amyloid precursor protein mutation in an Iowa family with dementia and severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann. Neurol. 2001;49:697–705. doi: 10.1002/ana.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks L, van Duijn CM, Cras P, Cruts M, Van Hul W, van Harskamp F, Warren A, McInnis MG, Antonarakis SE, Martin JJ, et al. Presenile dementia and cerebral haemorrhage linked to a mutation at codon 692 of the β-amyloid precursor protein gene. Nat. Genet. 1992;1:218–221. doi: 10.1038/ng0692-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye H, Gleason KA, Zhang D, Decatur SM, Kirschner DA. Differential effects of Phe19 and Phe20 on fibril formation by amyloidogenic peptide Aβ 16-22 (Ac-KLVFFAE-NH2) Proteins. 2010;78:2306–2321. doi: 10.1002/prot.22743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamino K, Orr HT, Payami H, Wijsman EM, Alonso ME, Pulst SM, Anderson L, O’Dahl S, Nemens E, White JA, et al. Linkage and mutational analysis of familial Alzheimer disease kindreds for the APP gene region. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1992;51:998–1014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kienlen-Campard P, Tasiaux B, Van Hees J, Li M, Huysseune S, Sato T, Fei JZ, Aimoto S, Courtoy PJ, Smith SO, et al. Amyloidogenic processing but not amyloid precursor protein (APP) intracellular C-terminal domain production requires a precisely oriented APP dimer assembled by transmembrane GXXXG motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:7733–7744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707142200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Laakso MP, Hanninen T, Hallikainen M, Alhainen K, Soininen H, Tuomilehto J, Nissien A. Midlife vascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease in later life: longitudinal, population based study. Br. Med. J. 2001;322:1447–1451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7300.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukar TL, Ladd TB, Robertson P, Pintchovski SA, Moore B, Bann MA, Ren Z, Jansen-West K, Malphrus K, Eggert S, et al. Lysine 624 of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) is a critical determinant of amyloid β peptide length: Support for a sequential model of γ-secretase intramembrane proteolysis and regulation by the amyloid β precursor protein (APP) juxtamembrane region. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:39804–39812. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.274696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon MA, Flanagan JM, Treutlein HR, Zhang J, Engelman DM. Sequence specificity in the dimerization of transmembrane α-helices. Biochemistry. 1992;31:12719–12725. doi: 10.1021/bi00166a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy E, Carman MD, Fernandez-Madrid IJ, Power MD, Lieberburg I, van Duinen SG, Bots GT, Luyendijk W, Frangione B. Mutation of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid gene in hereditary cerebral hemorrhage, Dutch type. Science. 1990;248:1124–1126. doi: 10.1126/science.2111584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London E. How principles of domain formation in model membranes may explain ambiguities concerning lipid raft formation in cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1746:203–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Van Horn WD, Chen J, Mathew S, Zent R, Sanders CR. Bicelles at low concentrations. Mol. Pharm. 2012;9:752–761. doi: 10.1021/mp2004687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor DL, Kim PS. Measurement of the β-sheet-forming propensities of amino acids. Nature. 1994;367:660–663. doi: 10.1038/367660a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munter L-M, Botev A, Richter L, Hildebrand PW, Althoff V, Weise C, Kaden D, Multhaup G. Aberrant amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing in hereditary forms of Alzheimer disease caused by APP familial Alzheimer disease mutations can be rescued by mutations in the APP GxxxG motif. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:21636–21643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munter LM, Voigt P, Harmeier A, Kaden D, Gottschalk KE, Weise C, Pipkorn R, Schaefer M, Langosch D, Multhaup G. GxxxG motifs within the amyloid precursor protein transmembrane sequence are critical for the etiology of Aβ42. EMBO J. 2007;26:1702–1712. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadezhdin KD, Bocharova OV, Bocharov EV, Arseniev AS. Dimeric structure of transmembrane domain of amyloid precursor protein in micellar environment. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:1687–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul C, Wang JP, Wimley WC, Hochstrasser RM, Axelsen PH. Vibrational coupling, isotopic editing, and β-sheet structure in a membrane-bound polypeptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5843–5850. doi: 10.1021/ja038869f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty SA, Decatur SM. Experimental evidence for the reorganization of β-strands within aggregates of the Aβ(16-22) peptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13488–13489. doi: 10.1021/ja054663y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z, Schenk D, Basi GS, Shapiro IP. Amyloid β-protein precursor juxtamembrane domain regulates specificity of γ-secretase-dependent cleavages. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:35350–35360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702739200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Tang TC, Reubins G, Fei JZ, Fujimoto T, Kienlen-Campard P, Constantinescu SN, Octave JN, Aimoto S, Smith SO. A helix-to-coil transition at the ε-cut site in the transmembrane dimer of the amyloid precursor protein is required for proteolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:1421–1426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812261106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer disease: Mechanistic understanding predicts novel therapies. Ann. Internal Med. 2004;140:627–638. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons M, Keller P, De Strooper B, Beyreuther K, Dotti CG, Simons K. Cholesterol depletion inhibits the generation of β-amyloid in hippocampal neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:6460–6464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SO, Eilers M, Song D, Crocker E, Ying WW, Groesbeek M, Metz G, Ziliox M, Aimoto S. Implications of threonine hydrogen bonding in the glycophorin A transmembrane helix dimer. Biophys. J. 2002;82:2476–2486. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75590-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Hustedt EJ, Brandon S, Sanders CR. Competition between homodimerization and cholesterol binding to the c99 domain of the amyloid precursor protein. Biochemistry. 2013;52:5051–5064. doi: 10.1021/bi400735x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takegoshi K, Nakamura S, Terao T. 13C-1H dipolar-assisted rotational resonance in magic-angle spinning NMR. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2001;344:631–637. [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, Bassit B, Chau DM, Li YM. An APP inhibitory domain containing the Flemish mutation residue modulates γ-secretase activity for Aβ production. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:151–158. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda T, Tomiyama T, Kitajima E, Idomoto T, Nomura S, Lambert MP, Klein WL, Mori H. Hypercholesterolemia accelerates intraneuronal accumulation of A beta oligomers resulting in memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease model mice. Life Sci. 2012;91:1169–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahrle S, Das P, Nyborg AC, McLendon C, Shoji M, Kawarabayashi T, Younkin LH, Younkin SG, Golde TE. Cholesterol-dependent γ-secretase activity in buoyant cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains. Neurobiol. Disease. 2002;9:11–23. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin YI, Bassit B, Zhu L, Yang X, Wang C, Li Y-M. γ-secretase substrate concentration modulates the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:23639–23644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.