Abstract

Both BMP and Wnt signaling control stem cells in bulge/dermal papilla, intestinal crypt, and bone marrow. To explore their roles in the limbal niche, which govern corneal epithelial homeostasis, we established an in vitro model of sphere growth by reunion between single limbal epithelial progenitor cells (LEPCs) and aggregates of limbal niche cells (LNCs) in 3D Matrigel. Compared to LEPCs alone, spheres formed by LEPC+LNC exhibited higher clonal growth and less corneal epithelial differentiation. Furthermore, pSmad1/5/8 was in the nucleus of LEPCs, but not LNCs, and correlated with upregulation of BMP1, BMP3, BMP4, all three BMP receptors, and BMP target genes. Inactivation of BMP signaling in LNCs was correlated with upregulation of noggin preferentially expressed by LNCs. Additionally, β-catenin was stabilized in the perinuclear cytoplasm in LEPCs and correlated with upregulation of Wnt7A and FZD5 preferentially expressed by LEPCs. Inactivation of Wnt signaling in LNCs was correlated with upregulation of DKK1/2 by LNCs. Addition of XAV939 that expectedly downregulated perinuclear β-catenin in LEPCs led to significant reduction of epithelial clonal growth, but upregulated all three BMP receptors and downregulated LNC-derived noggin, resulting in activation of BMP signaling in LNCs. Addition of noggin that expectedly downregulated nuclear localization of pSmad1/5/8 in LEPCs led to nuclear localization of β-catenin in larger LEPCs but membrane relocation of β-catenin in smaller LEPCs and significant upregulation of DKK1/2. Hence, balancing acts between Wnt signaling and BMP signaling exist not only within LEPCs but also between LEPCs and LNCs to regulate clonal growth of LEPCs.

Keywords: BMP, Wnt, Signaling, Clonal Growth, Limbus, Niche Cell, Epithelial Progenitor Cell, Stem Cell, Stem Cell Niche

INTRODUCTION

Stem cells (SC) are defined by their ability for self-renewal and adopting multiple fate decisions. Cumulative evidence indicates that self-renewal and fate decision of adult SC are regulated in a specialized microenvironment, termed “niche”. Regulation of SC in their native niche is conceivably mediated by a subset of neighboring cells including presumed niche cells (NCs), extracellular matrix, and modulating factors sequestered therein (reviewed in (1). In the model of the corneal epithelium, its SCs are located at a unique anatomic region termed limbal palisades of Vogt [2]. Like other adult SC niches, the limbal niche is composed of the extracellular matrix including the basement membrane and several candidate limbal NCs (LNCs) [3]. As a first step to dissect the in vivo complexity, we have recently used collagenase digestion to isolate a subset of pancytokeratin (PCK-) and vimentin+ LNCs that exhibit a unique phenotype, i.e., a size as small as 5 μm in diameter and heterogeneously expressing such SC markers as Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, Rex1, Nestin, N-cadherin, SSEA4, and CD34 [4],[5]. We further demonstrated that a close contact between limbal epithelial progenitor cells (LEPCs) including presumed SCs and LNCs is crucial to maintain the clonal growth on 3T3 fibroblast feeder layers [4]. Moreover, reunion between single LEPC and single LNC to form spheres in 3D Matrigel via SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling prevents differentiation of LEPC into the corneal fate decision [6]. However the signaling pathways intrinsically within LEPCs and extrinsically between LEPC and LNC that may govern self-renewal and corneal fate decision of LEPCs remain largely unknown.

Several studies have shown that adult SCs are regulated in their native niche by BMP, Wnt, Shh, and Notch signaling pathways [7],[8]. Canonical BMP and Wnt signaling pathways regulating gene transcription via SMAD and β-catenin/Lef transcription factors, respectively, are conserved and interact during many developmental processes [8–10]. For the epidermis, the BMP signaling is active to maintain SC quiescence in the hair bulge area [11–13] where the Wnt signaling is inhibited by Wnt inhibitors such as DKK1, sFRP, Wif1 [14]. In contrast, active SC renewal in the dermal papilla is achieved by blocking BMP signaling [11, 13, 15] and by activating the Wnt signaling [11, 13]. BMP-inactivated bulge SCs exhibit a gene profile of upregulation of Wnt ligands and receptors resembling hair SCs in the dermal papilla, suggesting that the competitive balance of intrabulge BMP and Wnt signaling governs the homeostasis of hair bulge SCs [16]. Gene ontology and network analyses also suggested that Wnt and TGF-β/BMP pathways are involved in the limbal niche regulation [17]. BMP2, BMP3, BMP4, BMP5, BMP7, and BMP receptors are expressed in human corneal epithelial cells and keratocytes [18, 19], suggesting BMP signaling is involved in regulation of corneal cells. Activation of Wnt signaling is noted during proliferation of LEPC induced by air-lifting [20] and addition of LiCl [21]. Exogenous addition of Wnt7A promoted corneal epithelial proliferation [22]. Hence, it remains largely unclear how both BMP and Wnt signaling might operate in achieving a balance between self-renewal and fate decision of LEPCs during interaction with LNCs in the limbal niche. To address this question, we first establish an in vitro model of sphere growth formed by reunion of LEPCs with LNC aggregates in 3D basement membrane-containing Matrigel. This model system serves as a surrogate limbal niche to recapitulate promotion of clonal growth (activation) and suppression of corneal differentiation (fate decision) of LEPCs by LNC aggregates. Our further investigation unravels for the first time that the aforementioned function of LEPCs is governed by integration of both BMP and Wnt signaling within LEPCs and between LEPCs and LNC through unique modulation of respective extracellular inhibitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of Limbal Epithelial Progenitor Cells and Niche Cells

LEPCs [23] and LNCs [4],[5],[6],[24] were isolated and cultured as previously prescribed. In brief, corneoscleral rims from 18 to 60 years old donors were obtained from the Florida Lions Eye Bank (Miami, FL) and managed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. After corneoscleral tissue was rinsed three times with Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 50 μg/mL gentamicin and 1.25 μg/mL amphotericin B, the remaining sclera, conjunctiva, iris, trabecular meshwork, and corneal endothelium were removed. Then the tissues were cut into 12 one-clock-hour segments by trimming of tissue at 1mm within and beyond the anatomic limbus. These limbal segments were digested at 4 °C for 16 h with 10 mg/ml Dispase II (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) in MESCM made of DMEM/F-12 (1:1) supplemented with 10% knockout serum, 5 μg/mL insulin, 5 μg/mL transferrin, 5ng/mL sodium selenite, 4 ng/mL bFGF, 10 ng/mL hLIF, 50 μg/mL gentamicin, and 1.25 μg/mL amphotericin B to generate intact epithelial sheets. The dispase-removed epithelial sheet was treated with 0.25% trypsin and 1 mM EDTA (T/E) at 37 °C for 15 min to yield single LEPCs. The remaining stroma was digested with collagenase A at 37 °C for 18 h to generate floating cell clusters. Single cells derived from limbal clusters were seeded at 1×104 per cm2 in the 6-well plate with coated Matrigel, which was prepared by adding 40 μl of 5% Matrigel per cm2 for 1 h at 37 °C before use and cultured in MESCM in humidified 5% CO2 with media changed every 3 or 4 days. Cells at 80–90% confluence were rendered single cells by T/E and serially expanded at the seeding density of 1×104 cells per cm2 for up to 4 passages to yield LNCs without epithelial contamination.

Cell Culture and Treatment

Single P4 LNCs were seeded at a density of 1×105 cells per cm2 in MESCM on 3D Matrigel, which was prepared by adding 100 μl of 50% Matrigel (diluted in MESCM) per well of a 96-well plate following incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, to form LNC aggregates. On the next day, single LEPCs obtained from dispase-isolated epithelial sheet were seeded on 3D Matrigel with or without LNC aggregates at a density of 1×105 cells per cm2. In some cultures, AMD3100 was added at the final concentration of 20 μg/ml [6], other were treated with or without 500 ng/ml noggin or 5 μM XAV939, a Wnt signaling inhibitor [25] on Day 0. All materials used for cell isolation, culturing and treatment are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

LEPCs or LNC aggregates alone or reunion (LEPC+LNC) cultured on 3D Matrigel in MESCM with or without noggin or XAV939 for 6 days and LNCs alone cultured on plastic were subjected to extraction of total RNAs by RNeasy Mini RNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). A total of 1–2 μg of total RNAs was reverse-transcribed to cDNA by High Capacity cDNA Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). qRT-PCR was carried out in a 20μl solution containing cDNA, TagMan Gene Expression Assay Mix and universal PCR Master Mix in 7300 Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). qRT-PCR profile consisted of 10 min of initial activation at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of 15-sec denaturation at 95 °C, and 1-min annealing and extension at 60 °C. The relative gene expression data was analyzed by the comparative CT method (ΔΔCT). All assays were performed in triplicate for each primer set. The results were normalized by an internal control, glceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). All TagMan Gene Expression Assays with probe sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 2.

RT2Profiler PCR Array

LEPCs or LNC aggregates alone or reunion (LEPC+LNC) cultured on 3D Matrigel in MESCM for 6 days were subjected to extraction of total RNAs by RNeasy Mini RNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). A total 0.5 μg of total RNAs was reverse transcribed to cDNA by RT2 First Strand Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for each plate. Real-Time PCR for RT2 Profiler PCR Array was carried out in a 25 μl solution containing cDNA, 2x RT2 SYBR Green Mastermix, cDNA synthesis reaction and RNase-free water on BMP and Wnt Signaling Pathway RT2 Profiler PCR Array Plate (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) in 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Real-time RT-PCR profile consists of 10 min of initial activation at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of 15-sec denaturation at 95 °C, and 1-min annealing and extension at 60 °C and an association stage including 15-sec at 95 °C, 1-min at 60 °C and 15-sec at 95 °C. The relative gene expression data was analyzed by RT2 profiler PCR array data analysis v3.5 (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Each array per plate was performed in triplicate, and contained 96 genes including 5 house genes and 91 genes of ligands, receptors, and modulators involved in and target genes of either BMP or Wnt singaling pathways. The detail of these genes is listed in Supplemental Table 3

3T3 Clonal Culture

The self-renewal (activation) of LEPCs was determined by a clonal assay on 3T3 fibroblast feeder layers in supplemental hormonal epithelial medium (SHEM), which was made of an equal volume of HEPES-buffered DMEM and Ham's F12 containing bicarbonate, 0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide, 2 ng/mL mouse-derived EGF, 5μg/mL insulin, 5μg/mL transferrin, 5 ng/mL sodium selenite, 0.5 μg/mL hydrocortisone, 30 ng/mL cholera toxin A subunit, 5% FBS, 50 μg/mL gentamicin, and 1.25 μg/mL amphotericin B(23). The feeder layer was prepared by treating 80% subconfluent 3T3 fibroblasts with 4 μg/mL mitomycin C at 37 °C for 2 h in DMEM containing 10% newborn calf serum before seeding at the density of 2×104 cells per cm2. On Day 6 of culturing, a total 1000 single cells obtained from LEPC+LNC treat with or without noggin or XAV939, and a total 500 single cells obtained from LEPC alone were seeded on mitomycin C–treated 3T3 fibroblast feeder layers for 12 days. The resultant clonal growth was assessed by rhodamine B staining, and colony-forming efficiency was measured by calculating the percentage of the clone number divided by the total number of PCK+ cells seeded according to the result of the double immunostaining of PCK/Vim. The resultant clones were subdivided into holoclone, meroclone, and paraclone based on the criteria established for skin keratinocytes [26] and successfully applied to LEPCs[4],[5].

Immunofluorescence Staining

Fresh human corneoscleral rims were embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) and snapfrozen in liquid nitrogen for cryosectioning into 6μm in thickness. Clones on 3T3 fibroblast feeder layer were fixed with 4% formaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min when terminated for the clonal assay. Single cells from all above treatment groups on Day 6 were prepared for cytospin using Cytofuge® at 1,000 rpm for 8 min [StatSpin, Inc., Norwood, MA), fixed with 4% formaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min. The above samples were permeabilized for immunofluorescence staining with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min and blocked with 2% BSA in PBS for 1 h at room temperature before being incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, corresponding secondary antibodies were incubated with for 1 h using appropriate isotype-matched non-specific IgG antibodies as controls. The nucleus was counterstained with Hoechst 33342 before being analyzed with a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope (LSM700, Carl Zeiss. Thornhood, NY). Detailed information about primary and secondary antibodies and agents used for immunostaining is listed in Supplemental Table 4.

Statistical Analysis

All assays were performed in triplicate, each with a minimum of three donors. The data were reported as means ± SD and compared using the appropriate version of Student's unpaired t-test. Test results were reported as two-tailed P-values, where P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

LNC Aggregates in 3D Matrigel

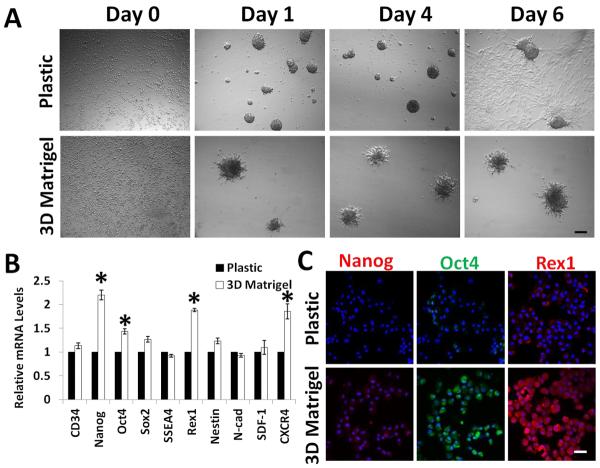

We have previously shown that LNC can be isolated and expanded on coated Matrigel in MESCM up to 12 passages [5],[24]. During this time, there is a transitional loss of the expression of several LNC markers, which can be regained by seeding single LNCs back in 3D Matrigel in MESCM [5]. To reaffirm this finding, we seeded single P4 LNCs at a density of 1×105/cm2 in MESCM in 3D Matrigel in MESCM. Our result showed that LNC formed aggregates in both 3D Matrigel and on plastic on Day 1. However by Day 6, aggregates formed on plastic began to spread to monolayers, but continued to be maintained in 3D Matrigel (Fig. 1A). qRT-PCR revealed significant upregulation of Nanog, Oct4, Rex1 and CXCR4 by LNC aggregates in 3D Matrigel when compared to the plastic control (Fig. 1B, * P<0.01, n=3).

Figure 1. 3D Matrigel promotes aggregation of LNC and maintains the phenotype of LNC.

Single P4 LNC was seeded on 3D Matrigel or plastic at 1×105/cm2 in MESCM. Phase contrast microscopy was used to monitor the formation of spheres (A). At Day 6, transcript levels expressed on 3D Matrigel were compared to that of the plastic control set as 1 by qRT-PCR (n=3, * P<0.01) (B). Immunofluorescence staining confirmed the higher expression of Nanog, Oct4, Rex1 and CXCR4 by LNC aggregates on 3D Matrigel (C, Nuclear counterstaining by Hoechst 33342). Scale bars: 100 μm in (A) and 50 μm in (C).

Immunofluorescence staining also confirmed higher expression of Oct4, Nanog, and Rex1 in 3D Matrigel when compared to the plastic control (Fig. 1C). The above finding supported our previous finding [5] and indicated that LNC aggregates formed in 3D Matrigel maintained the original phenotype.

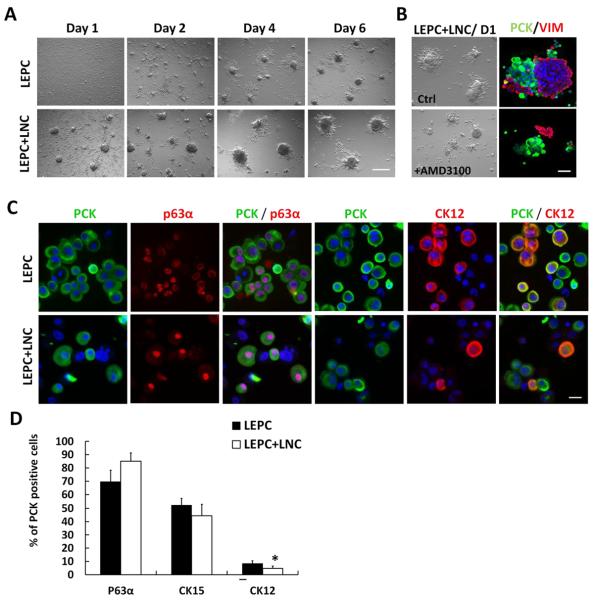

Reunion between LEPCs and LNC Aggregates Prevents Corneal Differentiation

We have previously demonstrated that single LEPCs and single LNCs could form reunion to yield sphere growth in 3D Matrigel in MESCM to prevent corneal differentiation of LEPCs [6],[24],[27]. Because LNC formed aggregates and maintained the phenotype in 3D Matrigel (Fig. 1) and because aggregated rather than single LNCs are more likely to mimic the in vivo niche, we would like to know whether pre-formed LNC aggregates also attracted single LEPCs to form spheres. Consistent with our previous report [6], single LEPC alone also gradually formed spheres in 3D Matrigel during 6 days of culturing (Fig. 2A). In contrast, when they were seeded with pre-formed LNC aggregates in LEPC+LNC, they formed fewer but larger spheres by Day 6 (Fig. 2A), supporting mutual attractions between LEPCs and LNC aggregates. Double immunostaining of PCK and Vimentin (VIM) confirmed that such sphere formation was mediated by SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in a similar manner to our previous report using single LEPCs and single LNCs [6] because interruption of SDF1/CXCR4 signaling by AMD3100 added at the time of seeding effectively disrupted reunion with PCK+ LEPCs and VIM+ LNCs, i.e., resulting in aggregates made of either PCK+ cells or Vim+ cells, but not those made of both in the control without AMD3100 (Fig. 2B). We then performed double immunostaining between PCK and the following three markers: p63α, a presumed marker of limbal SCs [28], CK15, which is preferentially expressed by limbal basal epithelial cells [29, 30] and the hair bulge region [31], and CK12, which is a known cornea-specific differentiation marker [32, 33]. The results showed that most PCK + cells were p63α+ no matter whether they were in LEPC or LEPC+LNC, consistent with the reported finding that only limbal “basal” epithelial progenitors can be retained in spheres in 3D Matrigel in this model [6]. However, more CK12+ cells were observed in LEPC than LEPC+LNC (Fig. 2C). Further quantification analysis revealed that there was no significant difference in the percentage of p63α + cells and CK15+ cells (Fig. 2D, 69.7 ± 8.6 % and 52.3 ± 4.9%, respectively, in LEPC vs. 85.1 ± 6.3% and 44.4 ± 8.6%, respectively, in LEPC+LNC (P>0.05, n=3). However, the percentage of CK12 + cells was significantly higher in LEPC (8.4 ± 2.0%) than in LEPC+LNC (4.7 ± 1.8%) (P<0.05, n=3). Hence, reunion between LEPC and LNC aggregates was also mediated by SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling and also reduced corneal fate decision similar to the reported reunion between LEPC and single LNC.

Figure 2. LNC aggregates on 3D Matrigel prevent LEPC from differentiation.

Single LEPC were seeded with or without LNC aggregates, of which the latter was treated with or without AMD3100 on 3D Matrigel in MESCM at 1×105/cm2. Phase contrast microscopy was used to monitor sphere growth of LEPCs with or without LNC aggregates (A), of which the latter with or without AMD3100 (B). Representative double immunofluorescence staining of PCK/VIM was shown on cytospin preparations of aggregates culture with or without AMD3100 (B). Representative double immunofluorescence staining of PCK/ p63α and PCK/CK12 was shown on single LEPCs from with or without LNC aggregates on Day 6 (C, Nuclear counterstaining by Hoechst 33342). The percentage of p63α+, CK15+, or CK12+ cells in PCK+ cells was compared between these two groups (D). Scale bars: 100 μm in (A and B) and 25 μm in (C)

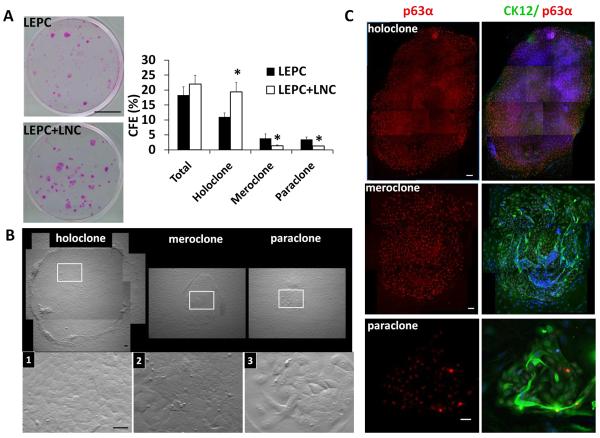

More Holoclones in LEPC+LNC

To determine whether the aforementioned suppression of corneal fate decision was also coupled with promotion of self-renewal of LEPCs by reunion with LNC aggregates, we performed a clonal assay by seeding a total 1000 single cells from LEPC+LNC and a total 500 single cells obtained from LEPC alone per six-well plate containing mitomycin C–treated 3T3 fibroblast feeder layers in SHEM for 12 days. A two-fold seeding density was used in LEPC+LNC was based on the result of the double immunostaining between PCK and Vim performed before seeding. The results showed that LEPC+LNC generated more rhodamine B-stained clones with a significantly higher percentage of holoclones and lower meroclones and paraclones than LEPC alone (Fig. 3A, *p < 0.05, n = 3). The three different types of clones, i.e., holoclone, meroclone, and paraclone, were differentiated by the clone size, the smoothness of the clone border, the cell size in the center of the clone as performed in keratinocytes [26] and LEPCs [4, 5]. Herein, we noted that the aforementioned morphological features also correlated well with expression of p63α and CK12 (Fig. 3B). Holoclones were not only larger and smoother and had small compact cells in the center, but also had p63α+ cells more densely packed in the periphery without any CK12+ cells (Fig. 3C). In contrast, paraclones and meroclones were not only smaller, irregular, and had large cells in the center, but also had p63α+ cells evenly distributed throughout the clone with many large suprabasal CK12+ cells (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these findings supported the notion that self-renewal of LEPCs was also promoted by reunion with LNC aggregates resembling reunion with single LNCs [5].

Figure 3. Holoclones are promoted by reunion with LNC aggregates.

To ensure that same number of PCK+ cells were compared, a total of 1000 single cells from LEPC+LNC and a total of 500 single LEPC were seeded per 6-well on mitomycin C–treated 3T3 fibroblast feeder layers in SHEM for 12 days. Representative clonal growth by rhodamine B staining showed that LEPC+LNC yielded a significantly higher percentage of holoclones and a significantly lower meroclones and paraclones (A, n = 3, *p < 0.05). Holoclone, meroclone, and paraclone were differentiated by the clone size, the smoothness of the clone border, the cell size in the center of the clone (B, inset marks the area with higher magnification), and by different patterns revealed by double immunofluorescence staining of CK12 and p63α (C, Nuclear counterstaining by Hoechst 33342). Scale bars: 10 mm in (A), 100 μm in (B), and 25μm in (C).

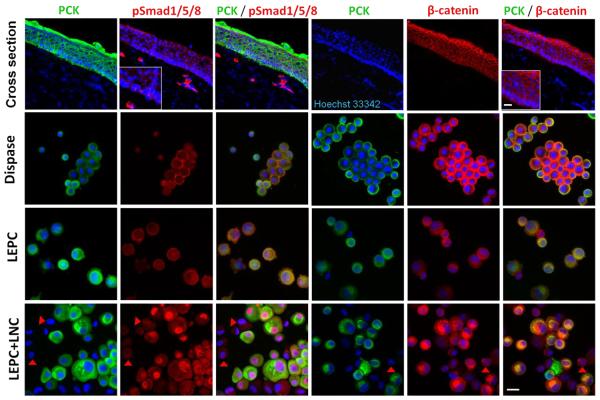

Activation of both BMP and Wnt signaling in LEPC+LNC

Using the above model system, we explored whether BMP and Wnt signaling were involved by performing double immunofluorescence staining between PCK and pSmad 1/5/8 or β-catenin. Cross-sections of the human limbal tissue showed positive staining of pSMAD1/5/8 close to the cell membrane in PCK+ limbal basal epithelial cells (Fig. 4). Interestingly, strong cytoplasmic pSMAD1/5/8 staining was detected in some stromal cells in the limbal stroma (Fig. 4) but not in cornea (data not shown). β-catenin was detected in the intercellular junction throughout the entire limbal and corneal epithelium (Fig. 4). The cytospin preparation of single cells from epithelial sheets freshly isolated by dispase also revealed the same pattern for both pSmad 1/5/8 and β-catenin in PCK+ cells (Fig. 4, dispase), indicating that dispase digestion followed by T/E did not activate either BMP or Wnt signaling in LEPCs. pSmad 1/5/8 and β-catenin were still located at the cell membrane of PCK + cells in cultures with LEPCs alone when dissociated from 3D Matrigel by dispase (Fig. 4, LEPC). In contrast, pSmad 1/5/8 was located in the nucleus and β-catenin was enriched in the perinuclear cytoplasm of PCK + cells in LEPC+LNC (Fig. 4, LEPC+LNC). These data indicated that both BMP and Wnt signaling pathways were not activated in LEPC spheres alone, but activated in LEPCs, but not in LNCs in LEPC+LNC in 3D Matrigel.

Figure 4. Activation of BMP and Wnt signaling in LEPC by re-union with LNC Aggregates.

Double immunofluorescence staining of PCK/pSmad 1/5/8 and PCK/β-catenin was performed on cross section of the human limbal tissue and cytospin preparations of the limbal epithelial sheet freshly isolated by dispase, LEPC alone, and LEPC+LNC. LNCs were PCK- cells (marked by red arrow heads). Nuclear counterstaining by Hoechst 33342. Scale bar: 25 μm.

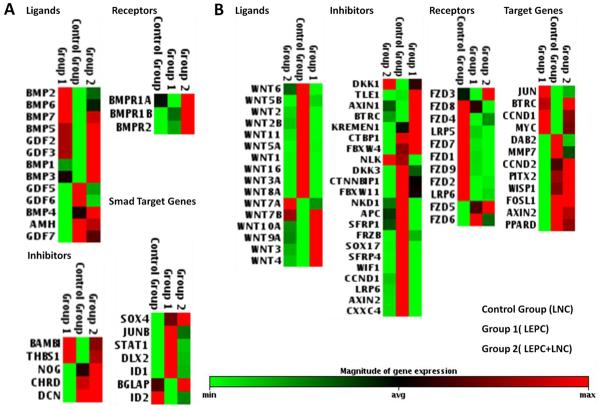

Differential Gene Expression in BMP and Wnt Signaling

To further dissect the mechanism and thereby activation of both BMP and Wnt signaling that occurred in LEPC+LNC, we used RT2 Profiler PCR Array to screen the expression of 5 house genes as the control and 84 genes including ligands, receptors, extracellular, membrane and intracellular modulators, and downstream target genes reported to modulate either BMP or Wnt signaling (for details of these genes see Supplemental Table 3). Setting the expression level of LNCs alone as the control, we compared those of LEPC alone and LEPC+LNC. Among 7 Smad target genes, Sox4 and bone gamma-carboxyglutamic acid-containing protein (BGLAP) were uniquely upregulated in LEPC+LNC, confirming the aforementioned activation of BMP signaling (Fig. 4). As shown in Figure 5A, among 12 BMP ligands, BMP1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7, Growth differentiation factor GDF2 and GDF3 were upregulated in LEPC culture alone while GDF5, 6, 7 and BMP4 were upregulated in LNC culture alone, suggesting that different BMP ligands were upregulated by LEPCs and LNCs. Interestingly, BMP1, BMP3, and BMP4 were further upregulated in LEPC+LNC. Among 3 BMP receptors, BMPR1B and BMPR2 were upregulated in LEPCs alone; BMPR1A was upregulated in LNCs alone, while all three were markedly upregulated in LEPC+LNC. Such BMP inhibitors as BMP and activin membrane-bound inhibitor homolog (BAMBI) and thrombospondin 1 (THBS1) were upregulated in LEPCs alone while noggin (NOG), chordin (CHRD), and decorin (DCN) were upregulated by LNCs alone. Among 12 Wnt targeted genes, G1/S-specific cyclin-D2 (CCND2), Paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 2 (PITX2) and WNT1-inducible-signaling pathway protein 1 (WISP1) were uniquely upregulated in LEPC+LNC, confirming the aforementioned activation of Wnt signaling (Fig. 4). As shown in Figure 5B, among 13 Wnt ligands, Wnt7A, 7B, 10A, 9A, 3, and 4 were upregulated in LEPC, while Wnt 1, 2, 3A, 2B, 5A, 5B, 6, 8A, 11, and 16 were upregulated in LNCs, also suggesting that different Wnt ligands were expressed by these two cell types. Importantly, Wnt7A was uniquely upregulated in LEPC+LNC. An overwhelming majority of 11 Wnt receptors was expressed by LNCs except for FZD5 and FZD6, which were expressed in LEPC. Interestingly, FZD3 and FZD5 were further upregulated in LEPC+LNC. Among 22 negative Wnt regulators, 18 genes were upregulated in LNCs, 4 genes were upregulated in LEPC, but interestingly, only Dickkopf-related protein (DKK) 1 was upregulated in LEPC+LNC. Hence, we have identified a subset of ligands, receptors, and extracellular inhibitors that are specifically upregulated during activation of Wnt and BMP signaling in LEPC+LNC.

Fig. 5. Differential expression of ligands, receptors, and modulators of BMP and Wnt signaling.

Total RNAs from LEPC alone, LNC alone, and LEPC+LNC in 3D Matrigel on day 6 were subjected to the RT2 Profiler PCR Array designed for BMP and Wnt signaling respectively. The relative expression level (low in green and high in red) was displayed for all ligands, receptors, and negative inhibitors, as well as a subset of target genes in BMP signaling (A) and Wnt signaling (B) were compared by setting LNC alone as the Control Group, LEPC alone as Group 1, and LEPC+LNC as Group 2.

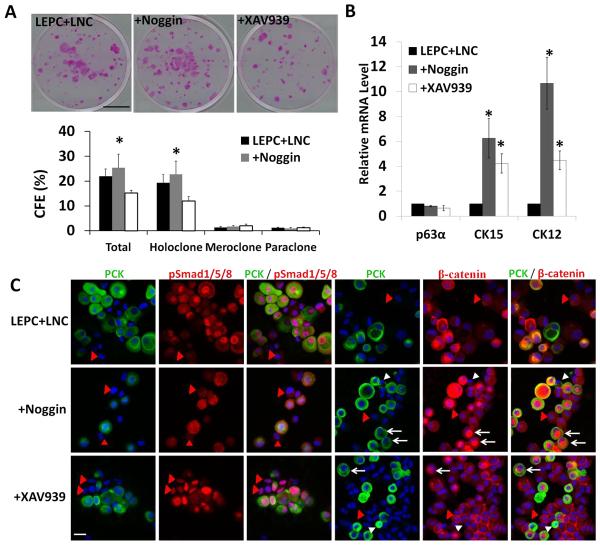

Involvement of BMP or Wnt Signaling in LEPC Clonal Growth

Because both BMP and Wnt signaling were activated in LEPCs in LEPC+LNC (Fig. 4), we would like to determine their respective role in controlling the activation of the aforementioned epithelial clonal growth of LEPCs (Fig. 3) by adding noggin to intercede extracellular BMP [34] and XAV939, which suppresses Wnt signaling by inhibiting tankyrase to promote cytoplasmic degradation of β-catenin [25]. The results showed that both colony-forming efficiency and the number of holoclones were not affected by noggin (Fig. 6A, P>0.05, n=3), but significantly reduced by XAV939 (P<0.05, n=3), suggesting that activation of Wnt signaling was necessary for promoting clonal growth of LEPCs. To determine the outcome of LEPCs following the treatment of noggin or XAV939, we investigated the expression of p63α, CK15 and CK12 by qRT-PCR. Compared to the control (LEPC+LNC), addition of either noggin or XAV939 significantly upregulated the transcript level of CK15 and CK12 without affecting that of p63α, suggesting that both treatments promoted corneal epithelial differentiation (Fig. 6B). Addition of noggin promoted significantly upregulated CK12 expression, suggesting more corneal differentiation, than addition of XAV939 (Fig. 6B). As expected, noggin downregulated nuclear localization of pSmad 1/5/8 in PCK+ LEPCs. Surprisingly, noggin turned the perinuclear cytoplasmic staining of β-catenin into two patterns, that is, nuclear localization in larger PCK+ cells and membrane localization in smaller PCK+ cells where adjacent LNCs also exhibited membrane staining of β-catenin (Fig. 6C). As expected, XAV939 reduced the intensity of the perinuclear cytoplasmic staining of β-catenin in larger PCK+ cells, but to nil in smaller PCK+ cells where adjacent LNCs also exhibited strong membrane staining of β-catenin. Surprisingly, XAV939 enhanced nuclear localization of pSmad 1/5/8 in both PCK+ LEPCs and PCK− LNCs, leading to activation of BMP signaling in both LEPCs and LNCs. These results disclosed that the clonal growth of LEPCs was promoted by Wnt signaling after reunion with LNCs and that such Wnt activation could negatively be modulated by BMP signaling.

Figure 6. Clonal growth of LEPC is modulated by BMP or Wnt signaling.

The same number of cells from LEPC+LNC was seeded per 6-well on mitomycin C–treated 3T3 fibroblast feeder layers in SHEM with or without 500 ng/ml noggin or 5 μM XAV939 for 12 days. Representative rhodamine B stained clones and percentage of total clones, holoclones, paraclones, and meroclones were compared (A, n = 3, *p < 0.05). Total RNAs from LEPC+LNC with or without treatment by noggin or XAV939 were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis of p63α, CK15, CK12 (B, n = 3, *p < 0.05 when compared to the control, i.e., LEPC+LNC, and when noggin was compared to XAV939 for CK12 but not CK15). Representative double immunofluorescence images of PCK/pSmad 1/5/8 and PCK/β-catenin were also compared. LNCs were PCK- cells (marked by red arrow heads). Two different staining patterns in PCK+ cells, indicated by white arrows and arrow heads, respectively were noted after noggin and XAV939 treatments. (C, Nuclear counterstaining by Hoechst 33342). Scale bars: 10 mm in (A), 25 μm in (C).

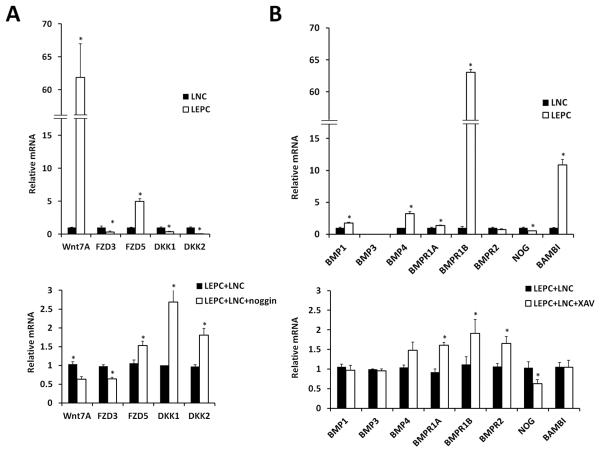

Integration of BMP and Wnt Signaling

Because noggin suppressed BMP signaling and promoted Wnt signaling in larger LEPCs in LEPC+LNC (Fig. 6B) we then performed qRT-PCR analysis to verify whether the genes identified by the PCR array in these two signaling pathways (Fig. 5) were indeed changed. Setting the expression level by LNCs alone as the control, we confirmed that both Wnt7A and FZD5 were predominantly expressed by LEPCs and that DKK1, DKK2 and noggin were predominantly expressed by LNCs (Fig. 7A). This finding was consistently noted in two separate donors. Setting the expression level of LEPC+LNC as the control, we noted that addition of noggin resulted in significant reduction of Wnt7A and FZD3 but upregulation of FZD5, DKK1, and DKK2 (Fig. 7A), suggesting that suppression of BMP signaling could modulate Wnt signaling. Because addition of XAV939 downregulated Wnt signaling and clonal growth but promoted BMP signaling in LNCs (Fig. 6), we also used qRT-PCR analysis to examine expression of those genes identified by the array (Fig. 5). Setting the expression level by LNCs alone as the control, we noted that BMP1, BMP4, BMPR1A, BMPR1B, and BAMBI were more expressed by LEPCs, while noggin was expressed more by LNCs (Fig. 7B). Using the expression pattern of LEPC+LNC as the control, we noted that addition of XAV939 upregulated all three BMP receptors, but downregulated noggin (Fig. 7B), suggesting that suppression of Wnt signaling by XAV9393 could upregulate BMP signaling. Collectively, these balancing acts between Wnt signaling and BMP signaling could partake in clonal growth of LEPCs after reunion with LNC aggregates.

Figure 7. Integration of BMP and Wnt Signaling.

Total RNAs from LEPC alone, LNC alone, and LEPC+LNC with or without noggin (A) or XAV939 (B) were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis of genes identified by the PCR array. The top panel compares LNC alone and LEPC alone by setting the transcript expression level by the former as 1 (n=3, * indicates P<0.05). The bottom panel compares the effect of either noggin or XAV939 by setting the transcript expression level by LEPC+LNC as 1 (n=3, * indicates P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

In the locale of limbal palisades of Vogt, limbal epithelial SCs lie deep in the stroma, as suggested by undulation and fenestration of the basement membrane [35, 36], by crypt-like structures disclosed by serial histologic sectioning [36–38] and ultrastructural analyses [39] and by the necessity of using collagenase rather than dispase for their isolation [4]. Such teleological closeness is crucial to modulate fate decision of LEPCs, as demonstrated by the prevention of corneal epithelial differentiation in the sphere growth generated by reunion between single LEPCs and single NCs in 3D Matrigel [6],[24],[27]. Because LNCs in this locale exist not as single cells but a group of cells with heterogeneous expression of a number of ESC markers [4], as a first step to dissect the in vivo complexity and recapitulate this in vivo feature, we have demonstrated that LNCs formed aggregates in 3D Matrigel and retained their normal phenotype based on expression of several ESC markers (Fig. 1). Like reunion between single LEPCs and single NCs reported earlier [6], reunion between single LEPCs and LNC aggregates also occurred and maintained their progenitor status (Fig. 2). Similar to previous reports [6],[24],[27], reunion between single LEPCs and LNC aggregates in 3D Matrigel was mediated by SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling and accompanied by inhibition of corneal fate decision (Fig. 2) and significantly more clonal growth with more holoclones (Fig. 3). Therefore, this in vitro model recapitulates an in vivo scenario where self-renewal and fate decisions of LEPCs are controlled by LNCs in a close range within the basement membrane.

Both BMP and Wnt signaling were not activated in PCK+ LEPCs in vivo and in vitro when freshly isolated by dispase (Fig. 4). Activation of Wnt signaling plays a critical role in controlling self-renewal of adult SCs located in the dermal papilla [40], the intestinal crypt [41], and the bone marrow [42]. Consistent with this general paradigm, our study demonstrated that clonal growth of LEPCs on 3T3 fibroblast feeder layers measured by the colony-forming efficiency and the total number of holoclones was promoted when LEPCs formed reunion with LNC aggregates and that such activation of clonal growth was accompanied by activation of Wnt signaling (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Activation of Wnt signaling in LEPC+LNC was demonstrated by upregulation of CCND2, PITX2, and WISP1, all known Wnt target genes, and was further supported by the finding that the aforementioned clonal growth was significantly reduced by addition of XAV939, which inhibits the Wnt signaling (Fig. 6). Array and qRT-PCR analyses of the entire family of Wnt ligands and receptors disclosed that such activation of Wnt signaling was correlated with upregulation of Wnt7A and FZD5 uniquely expressed by LEPCs (Fig. 5 and Fig. 7). Because exogenous Wnt7A has been shown to promote proliferation of corneal epithelial cells [22], future studies are needed to determine how the expression of Wnt7A and FZD5 by LEPCs is upregulated after reunion with LNC aggregates.

Additionally, BMP signaling was also activated as evidenced by nuclear translocation of pSmad 1/5/8 in LEPCs after reunion between LEPCs and LNC aggregates (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). Activation of BMP signaling in LEPCs was supported by upregulation of Sox4 and BGLAP, known BMP target genes, and by upregulation of BMP1, 3, and 4 and three BMP receptors among all ligands and receptors surveyed, by the array (Fig. 5 and Fig. 7). BMP signaling counteracts Wnt signaling in controlling SC activation in the bulge SCs [16]. Herein, we noted that addition of noggin, which suppresses BMP signaling as evidenced by decreased nuclear localization of pSmad 1/5/8 in LEPCs, resulted in nuclear translocation of perinuclear cytoplasmic β-catenin, i.e., full activation of the canonical Wnt signaling (Fig. 6). This finding reminisces an earlier finding in mouse embryonic epidermal buds where Wnt3a that stabilizes cytoplasmic β-catenin is complimented by noggin, which induces Lef1 expression, resulting in full activation of canonical Wnt signaling [15]. In our model, we noted nuclear translocation of cytoplasmic β-catenin in larger PCK+ cells but relocation to the cell membrane in smaller PCK+ cells (Fig. 6), suggesting that suppression of BMP signaling by noggin could result in divergent responses in Wnt signaling in these two LEPC populations. Because activation of Wnt signaling was correlated with clonal growth of LEPCs, we speculate that suppression of BMP signaling by noggin might have resulted in activation of clonal growth in presumed more differentiated LEPCs sparing younger ones, explaining why the overall clonal growth on 3T3 fibroblast feeder layers was not significantly changed from the control (Fig. 6). This viewpoint was also suggested by upregulation of more CK12 transcripts while maintaining a similar level of CK15 transcript by noggin when compared to XAV939 (Fig. 6). Future studies are needed to determine whether re-establishment of membranous expression of β-catenin in smaller LEPCs and adjacent LNCs might help control “quiescence” of limbal epithelial SCs.

It should be noted that both Wnt and BMP signaling were not activated in LNCs after reunion with LEPCs (Fig. 4). We wondered if the inactivation of Wnt signaling in LNCs might be due to unique upregulation of DKK1 (Fig. 5), which was preferentially expressed by LNCs (Fig. 7). Although DKK1 was expressed slightly more by LEPC in the PCR array (Fig. 5), RT-PCR verified consistent predominant expression of DKK1, DKK2 and noggin by LNCs and predominant expression of Wnt7A and FZD5 by LEPCs in two different donors (Fig. 7). DKK2 knockout mice manifest ocular surface keratinization as a result of the loss of the corneal fate decision of the ocular surface epithelial progenitors [43]. Unlike mice, in which DKK2 is expressed by the ocular surface epithelium [43], we noted that the DKK2 transcript was uniquely expressed by LNCs (Fig. 7). Expression of DKK1, however, was notably upregulated in LEPC+LNC (Fig. 5) and expression of both DKK1 and DKK2 was further upregulated by exogenous addition of noggin (Fig. 7). It is tempting to speculate that such upregulation of DKK1 and DKK2 by LNCs upon addition of noggin might suppress Wnt signaling in smaller LEPCs adjacent to LNCs. Similarly, we also wonder if the inactivation of BMP signaling in LNCs might be due to unique upregulation of noggin (Fig. 5), which was preferentially expressed by LNCs (Fig. 7). Because exogenous addition of XAV939 significantly downregulated expression of noggin (Fig. 7), this finding explained why BMP signaling was eventually upregulated in LNCs (Fig. 6). Hence, downregulation of either BMP or Wnt signaling in LNCs during LEPC+LNC was likely due to upregulation of noggin or DKK1/2 by LNCs. Our findings suggested that BMP and Wnt signaling might be integrated in the limbal niche not only within LEPCs but also between LEPCs and LNCs and that one controlling mechanism is to modulate expression of respective Wnt or BMP inhibitors by LNCs. Further studies into such a modulating mechanism of these three inhibitors should help us understand better how LNCs might regulate quiescence, self-renewal, and fate decision of LEPCs.

Supplementary Material

Highlights

To estabilish an in vitro model of surrogate LNCs to unite with LEPCs in 3D Matrigel

Comparative analysis of Wnt and BMP pathways in LEPCs, LNCs and LEPCs+LNCs

Study the expressions of receptors and ligands of Wnt and BMP signaling by integration of BMP or Wnt inhibitors

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to thank Angela Y. Tseng for the preparation of this manuscript.

Supported by RO1 EY06819 grant from the National Eye Institute, the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland (Scheffer C. G Tseng).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contribution Bo Han: conception and design, provision of study material, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing Szu-Yu Chen: conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, Ying-Ting Zhu: provision of study material and collection and/assembly of data Scheffer C. G. Tseng: conception and design, financial support, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing and final approval of manuscript

Reference List

- 1.Li L, Clevers H. Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science. 2010;327:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.1180794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavker RM, Tseng SC, Sun TT. Corneal epithelial stem cells at the limbus: looking at some old problems from a new angle. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:433–446. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li W, Hayashida Y, Chen YT, et al. Niche regulation of corneal epithelial stem cells at the limbus. Cell Res. 2007;17:26–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen SY, Hayashida Y, Chen MY, et al. A new isolation method of human limbal progenitor cells by maintaining close association with their niche cells. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2011;17:537–548. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2010.0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xie HT, Chen SY, Li GG, et al. Isolation and expansion of human limbal stromal niche cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:279–286. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie HT, Chen SY, Li GG, et al. Limbal epithelial stem/progenitor cells attract stromal niche cells by SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling to prevent differentiation. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1874–1885. doi: 10.1002/stem.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spradling A, Drummond-Barbosa D, Kai T. Stem cells find their niche. Nature. 2001;414:98–104. doi: 10.1038/35102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Staal FJ, Luis TC. Wnt signaling in hematopoiesis: crucial factors for self-renewal, proliferation, and cell fate decisions. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109:844–849. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsson J, Karlsson S. The role of Smad signaling in hematopoiesis. Oncogene. 2005;24:5676–5692. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobielak K, Stokes N, de la CJ, et al. Loss of a quiescent niche but not follicle stem cells in the absence of bone morphogenetic protein signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10063–10068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703004104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Geoghegan A, et al. Self-renewal, multipotency, and the existence of two cell populations within an epithelial stem cell niche. Cell. 2004;118:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, He XC, Tong WG, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling inhibits hair follicle anagen induction by restricting epithelial stem/progenitor cell activation and expansion. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2826–2839. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tumbar T, Guasch G, Greco V, et al. Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science. 2004;303:359–363. doi: 10.1126/science.1092436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamora C, DasGupta R, Kocieniewski P, et al. Links between signal transduction, transcription and adhesion in epithelial bud development. Nature. 2003;422:317–322. doi: 10.1038/nature01458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kandyba E, Leung Y, Chen YB, et al. Competitive balance of intrabulge BMP/Wnt signaling reveals a robust gene network ruling stem cell homeostasis and cyclic activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1351–1356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121312110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakatsu MN, Vartanyan L, Vu DM, et al. Preferential biological processes in the human limbus by differential gene profiling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.You L, Kruse FE, Pohl J, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins and growth and differentiation factors in the human cornea 1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:296–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohan RR, Kim W-J, Mohan RR, et al. Bone morphogenic proteins 2 and 4 and their receptors in the adult human cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:2626–2636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawakita T, Espana EM, He H, et al. Intrastromal invasion by limbal epithelial progenitor cells is mediated by epithelial-mesenchymal transition activated by air exposure. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:381–393. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62983-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakatsu MN, Ding Z, Ng MY, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates proliferation of human cornea epithelial stem/progenitor cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:4734–4741. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyu J, Joo CK. Wnt-7a up-regulates matrix metalloproteinase-12 expression and promotes cell proliferation in corneal epithelial cells during wound healing. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21653–21660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espana EM, Romano AC, Kawakita T, et al. Novel enzymatic isolation of an entire viable human limbal epithelial sheet. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4275–4281. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li GG, Chen SY, Xie HT, et al. Angiogenesis potential of human limbal stromal niche cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:3357–3367. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang SM, Mishina YM, Liu S, et al. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizesWnt signalling. Nature. 2009;461:614–620. doi: 10.1038/nature08356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrandon Y, Green H. Three clonal types of keratinocyte with different capacities for multiplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:2302–2306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li GG, Zhu YT, Xie HT, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from human limbal niche cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:5686–5697. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pellegrini G, Dellambra E, Golisano O, et al. p63 identifies keratinocyte stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3156–3161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061032098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshida S, Shimmura S, Kawakita T, et al. Cytokeratin 15 can be used to identify the limbal phenotype in normal and diseased ocular surfaces. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4780–4786. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyngholm M, Vorum H, Nielsen K, et al. Differences in the protein expression in limbal versus central human corneal epithelium--a search for stem cell markers. Exp Eye Res. 2008;87:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Lyle S, Yang Z, et al. Keratin 15 promoter targets putative epithelial stem cells in the hair follicle bulge. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:963–968. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen WY, Mui MM, Kao WW, et al. Conjunctival epithelial cells do not transdifferentiate in organotypic cultures: expression of K12 keratin is restricted to corneal epithelium. Curr Eye Res. 1994;13:765–778. doi: 10.3109/02713689409047012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu C-Y, Zhu G, Converse R, et al. Characterization and chromosomal localization of the cornea-specific murine keratin gene Krt1.12. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24627–24636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bragdon B, Moseychuk O, Saldanha S, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins: a critical review. Cell Signal. 2011;23:609–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gipson IK. The epithelial basement membrane zone of the limbus. Eye. 1989;3(Pt 2):132–140. doi: 10.1038/eye.1989.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dua HS, Shanmuganathan VA, Powell-Richards A, et al. Limbal epithelial crypts: a novel anatomical structure and a putative limbal stem cell niche. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:529–532. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.049742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shanmuganathan VA, Foster T, Kulkarni BB, et al. Morphological characteristics of the limbal epithelial crypt. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:514–519. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.102640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yeung AM, Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Kulkarni B, et al. Limbal epithelial crypt: a model for corneal epithelial maintenance and novel limbal regional variations. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:665–669. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shortt AJ, Secker GA, Munro PM, et al. Characterization of the limbal epithelial stem cell niche: novel imaging techniques permit in vivo observation and targeted biopsy of limbal epithelial stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1402–1409. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myung PS, Takeo M, Ito M, et al. Epithelial Wnt ligand secretion is required for adult hair follicle growth and regeneration. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:31–41. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirata A, Utikal J, Yamashita S, et al. Dose-dependent roles for canonical Wnt signalling in de novo crypt formation and cell cycle properties of the colonic epithelium. Development. 2013;140:66–75. doi: 10.1242/dev.084103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang J, Nguyen-McCarty M, Hexner EO, et al. Maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells through regulation of Wnt and mTOR pathways. Nat Med. 2012;18:1778–1785. doi: 10.1038/nm.2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mukhopadhyay M, Gorivodsky M, Shtrom S, et al. Dkk2 plays an essential role in the corneal fate of the ocular surface epithelium. Development. 2006;133:2149–2154. doi: 10.1242/dev.02381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.