Mild Cognitive Impairment

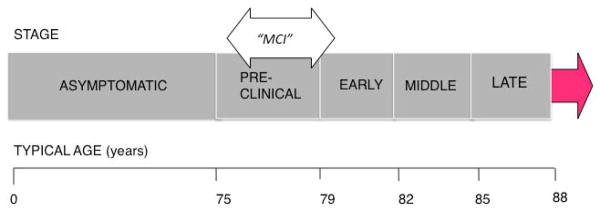

The pathway to Alzheimer’s disease may be viewed along a continuum in which cognition slowly declines over time from normal cognition to dementia (see Figure 1). Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) may be considered a transition point along this continuum where symptoms of cognitive impairment first become manifest. MCI is often defined as a subjective complaint of mild memory impairment or cognitive impairment that is also demonstrated objectively on cognitive testing. For a diagnosis of dementia, an individual must have impairment in more than one cognitive domain and show decline in functional status, whereas a person diagnosed as having MCI shows relatively preserved independent functioning in activities of daily living (dressing, eating) and only mild impairment in one or more cognitive domain. The degree of cognitive impairment, the domain affected, and the person reporting change in memory or functional activity all will influence how a diagnosis of MCI(or a related condition) comes to be made (Petersen, 2004).

Figure 1.

Decline from Normal Cognition to Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease appears as a continuum without discrete boundaries.

For this article, the term mild cognitive impairment represents this general state of mild cognitive change, which suggests that the person is at increased risk for dementia. In the absence of a standard set of cognitive measures (other than a test of delayed recall and of several other cognitive domains) and cutoff scores, MCI in practice is currently a clinical diagnosis. Standard mental status screening tests like the Mini Mental State Examination that are used in the primary care office may be insensitive to the subtle cognitive deficits seen in MCI. It is important to note that although MCI often progresses to dementia, some patients may return to normal on subsequent testing, and some remain stable. Cases of MCI may also be related to a variety of other medical conditions or depression, so it is important for a number of reasons to recognize MCI and to take memory or other cognitive complaints seriously.

Reports of the extent to which MCI progresses to Alzheimer’s disease vary widely, ranging from 2 percent per year to 31 percent per year (Bruscoli and Lovestone, 2004). This variation may be due to the lack of a consistent definition of MCI among many of the studies. Patients may show a subtle decline on neuropsychological testing several years before the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s (Amieva et al., 2005), with a more accelerated decline in the three years preceding diagnosis (Howieson et al., 2008). MCI may encompass several clinical subtypes and may be classified into amnestic (characterized by primarily a memory impairment, with a normal level of functioning) and non-amnestic (impairment of a cognitive domain other than memory, with a normal level of functioning) (Petersen et al., 2001). Many, but not all, amnestic MCI patients progress to Alzheimer’s disease (Ganguli et al., 2004). Non-amnestic MCI may be a precursor to a non-Alzheimer’s dementia such as fronto-temporal dementia (FTD) or dementia associated with vascular disease.

Given the diverse symptoms that first bring MCI patients to clinicians and the clinical implications of MCI, it may be necessary for the clinician to acquire additional supporting evidence about the individual for example, more detailed psychometric evaluations or plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, or neuroimaging studies to aid diagnosis and prognosis.

The neuropathological changes of Alzheimer’s most likely begin years before a clinical diagnosis of dementia or even MCI. As cognitive decline is clinically observed, it is reasonable to assume that the pathological substrates of the disease are increasing. Seen in postmortem examination of the brain, the pathologic hallmarks of Alzheimer’s are plaques, consisting of the protein amyloid, and neurons with tangled filaments, initially seen mostly in the hippocampus. Interestingly, brains that are clinically classified as cognitively normal, MCI, or Alzheimer’s may show great pathological heterogeneity upon postmortem examination. For example, some people who were considered cognitively normal on clinical exam may be found to have significant Alzheimer’s pathology postmortem (Erten-Lyons et al., 2009; Knopman et al., 2003). Neuropathologically, the diagnosis of MCI is unclear. In general, postmortems reveal more amyloid plaques in MCI than in normal aging, but the pathology of MCI may be difficult to distinguish from the pathology of Alzheimer’s. Cerebrovascular disease, which has its own treatment implications, may also be an important contributor.

The Quest for Early Diagnosis

As noted, current interest in achieving an earlier diagnosis of Alzheimer’s is great because the potential interventional therapies being developed may have their greatest impact early in the disease course. Researchers have been searching for early markers, or biomarkers, to allow diagnosis of Alzheimer’s before clinical symptoms appear.

Biomarkers are indicators of a biological or disease state that can be used to identify a particular disease, monitor progression, and predict response to treatment. Biomarkers are typically thought of as molecules in body fluids such as serum, plasma, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), but they may also be considered more broadly as any surrogate marker for pathological changes. These markers could be changes of the brain revealed with neuroimaging or they could be physiological changes that can be measured clinically in asymptomatic individuals.

CSF and Plasma Biomarkers

Currently, CSF examination is not used in the routine clinical evaluation of dementia. It is more commonly used to identify etiologies of cognitive decline presenting in atypical or rapidly progressive dementias. CSF shows great potential as a diagnostic tool for Alzheimer’s, but is not currently realized. CSF has a clinical role in selected cases, distinguishing Alzheimer’s from other dementias (see the case of Mr. D). Research on the use of biomarkers in CSF as a diagnostic tool or measure of progression for MCI or Alzheimer’s has focused on proteins thought to be involved in disease pathogenesis. Other promising studies focus on markers of neuronal degeneration.

Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging is commonly used in clinical practice in the evaluation of patients with cognitive impairment. Imaging is used clinically to evaluate for specific causes of cognitive impairment such as stroke or space-occupying lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is usually preferred because it provides more detail, but computed tomography (CT) may be used, especially when MRI is contraindicated because of implants such as pacemakers or in cases of claustrophobia. In research, neuroimaging is being studied on several fronts. Structural neuroimaging with MRI is commonly used to quantify loss of brain volume loss (Anderson, Litvack, and Kaye, 2005; Ries et al., 2008). It may aid in the initial diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and serve as a marker of progression of disease. Functional neuroimaging identifies areas of alteration in metabolic activity. Future diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s may use neuroimaging as an adjunctive diagnostic tool or as a biomarker for diagnosis (Dubois et al., 2007).

Genetics

The risk of Alzheimer’s is linked to the interplay of genetics and environmental factors. Major risk factors include age and a family history of dementia. Most knowledge of the related genetics comes from the study of early-onset Alzheimer’s (Brouwers, Sleegers, and Van Broeckhoven, 2008). “Early-onset” is arbitrarily considered to be before the age of 65, but early-onset cases with known genetic mutations typically have an onset before the age of 50. Early-onset Alzheimer’s occurs in 1 percent to2 percent of Alzheimer’s patients, and has generally similar pathology to late-onset Alzheimer’s.

There are three known genetic mutations in early-onset Alzheimer’s: the APP gene and Presenilin genes 1 and 2. These are causal genes and are involved in amyloid processing. The APP mutation is autosomal dominant, that is, an individual need only receive the gene from one parent in order to inherit the disorder. Together, APP and Presenilin 1 and 2 account for fewer than 10 percent of all cases of early-onset Alzheimer’s. Genetic studies of these early-onset forms have contributed greatly to our understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms of Alzheimer’s and form the strongest case for the role of amyloid leading to the disease in nongenetic cases.

The apolipoprotein E gene, or ApoE4, is associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s (Brouwers, Sleegers, and Van Broeckhoven, 2008) and is consistently overrepresented in families that have a high rate of late-onset Alzheimer’s as well as in sporadically occurring Alzheimer’s. The risk of developing Alzheimer’s is increased up to three times in people with APOE4 from one parent and up to fifteen times in people with the gene from both parents. It also appears that people who carry the APOE4 genes may also have an earlier age of onset of Alzheimer’s.

The exact role of the ApoE4 allele remains unclear even though it was first recognized as a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s fifteen years ago. Knowledge of other major genes that contribute to late-onset Alzheimer’s is limited, but remains a very active focus of research (Bertram et al., 2007), especially with the advent of new genomic technologies.

The genetics of MCI are similar to that of Alzheimer’s, with a higher representation of ApoE4 carriers. Clinically, genetic testing for known genetic mutations is reserved for those with age of onset younger than 65 and a family history in an autosomal dominant pattern. Those who undergo genetic testing should also undergo genetic counseling. There is no clinical indication to test for ApoE4 genotype in MCI or late-onset dementia.

Technology

Technology is being used to assist older adults at home with devices such as alarms and pill reminders (see the case of Mrs. T) and to assist clinicians, for example, with computerized cognitive testing. However, technology-assisted methodologies for early detection of MCI or dementia are new and likely to be used increasingly. In general, the use of in-home assessment, for example, with motion detectors to detect subtle physical changes, for physiological monitoring and for frequent on-line questionnaires allows for novel opportunities to obtain more frequent, real-time data. Continuous or more frequent measurement affords the opportunity to map trajectories of change and account for individual variability in measurements that cannot be determined with current infrequent, episodic assessments performed in the office or in a clinic. Thus, for example, it has been shown that changes in walking speed or gait predict future onset of MCI. These predictive motor changes may now be identified years before MCI onset by being able to measure gait variability multiple times in a day at home (Hayes et al., 2008). Other opportunities may be afforded by being able to assess daily function unobtrusively, such as medication-taking behavior using an automated medication-recording device. Accordingly, using such a “Medtracker” to test the ability to adhere to a medication regimen, may provide a sensitive measure of an instrumental activity of daily living that is susceptible to early cognitive change (Hayes et al., 2008). Ultimately, these methodologies may be employed to improve the conduct of clinical trials by providing more sensitive and early measures of cognitive and functional change (Kaye, 2008).

Future Research

Research into the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s is in a rapidly evolving state. These methods and technologies will continue to be developed to provide more robust diagnostic tools. Future directions of study will include the identification of new CSF markers, plasma or urine markers, and the use of proteomics assessment of protein signatures in the brain or body fluids. New neuroimaging techniques will be especially focused, not only on early detection, but to also to monitor disease progression or the effect of disease-modifying agents. Newer amyloid imaging and other targeted imaging agents will be developed that can be used clinically to aid diagnosis and in clinical trials to monitor the reversal of amyloid deposition and other pathologies. CSF or plasma studies may be combined with neuroimaging for more sensitive diagnostic tools. The use of genome-wide association studies of families characterized by late-onset Alzheimer’s as well as sporadic Alzheimer’s will continue to expand. Technology studies may make use of home-based networks with smaller sensors, wireless technology, combining home computer use with other commonly used devices, and integration of biomarker data with online clinical data. These technological advances will move the focus of research to be increasingly home-based and thus more ecologically representative of the larger community.

The Case of Mr. D: At first, a mixed message

A 54- year-old man with a long history of depression developed difficulties in his job as a manager. He described poor concentration and problems with his memory. Both Mr. D and his primary care physician attributed these problems to depression. A neuropsychological evaluation showed mild cognitive impairment and depression. Mr. D was treated with antidepressants, but there was no improvement in his cognition, and he subsequently lost his job. He was referred to a neurologist for further evaluation. His score on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) at the initial visit was 29/30, within normal range. A magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the brain was normal and other imaging was unrevealing. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed a profile consistent with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. He was started on an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, a medication used for patients with Alzheimer’s, and was enrolled in an observational clinical study. Mr. D was followed for several years and eventually developed characteristic symptoms of Alzheimer’s, with impairment of multiple cognitive domains and activities of daily living. Mr. D’s score on his last recorded MMSE was 10/20, which indicated progression of the disease to a more severe stage.

The Case of Mrs. T: Some solutions are simple

Mrs. T, a 74-year-old retired real estate broker, gradually developed problems remembering names and frequently repeated herself. Still, she was able to function independently at home and lived alone, with frequent visits from her son. She managed her own medications, but would occasionally forget whether she had taken them or not. One day she called her doctor’s office, sounding confused. An ambulance was sent to her house, and she was hospitalized with extremely low blood pressure. A review of her medications showed that she had taken several doses of her blood pressure medication that day.

Upon Mrs. T’S discharge from the hospital, her son purchased an automated pill dispenser and arranged for a caregiver to check on her for a few hours daily. Her son would set up the medication dispenser once a week with sealed containers containing her morning and evening doses of medication. A timer would release the dose, and an alarm would notify her that it was time to take her medication. She had no further medication errors after that. With the medication dispenser and occasional caregiver visits, she was able to remain in her own home.

Acknowledgments

The authors are supported by Grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institute on Aging (AG08017, AG024978, AG024059, AG10483).

References

- Amieva H, et al. The 9 year cognitive decline before dementia of the Alzheimer type: a prospective population-based study. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 5):1093–101. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson VC, Litvack ZN, Kaye JA. Magnetic resonance approaches to brain aging and Alzheimer disease-associated neuropathology. Topics in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2005;16(6):439–52. doi: 10.1097/01.rmr.0000245458.05654.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram L, et al. Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: the AlzGene database. Nature Genetics. 2007;39(1):17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers N, Sleegers K, Van Broeckhoven C. Molecular genetics of Alzheimer’s disease: An update. Annals of Medicine. 2008;40(8):1–22. doi: 10.1080/07853890802186905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruscoli M, Lovestone S. Is MCI really just early dementia? A systematic review of conversion studies. International Psychogeriatrics. 2004;16(2):129–40. doi: 10.1017/s1041610204000092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurology. 2007;6(8):734–46. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erten-Lyons D, et al. Factors associated with resistance to dementia despite high Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2009;72:354–60. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000341273.18141.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment, amnestic type: an epidemiologic study. Neurology. 2004;63(1):115–21. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000132523.27540.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes TL, et al. Unobtrusive assessment of activity patterns associated with mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2008;4(6):395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howieson DB, et al. Trajectory of mild cognitive impairment onset. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2008;14(2):192–8. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye J. Home-based technologies: a new paradigm for conducting dementia prevention trials. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2008;4(1 Suppl 1):S60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, et al. Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 2003;62(11):1087–95. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.11.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2004;256(3):183–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Archives of Neurology. 2001;58(12):1985–92. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.12.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries ML, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging characterization of brain structure and function in mild cognitive impairment: a review. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2008;56(5):920–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]