Abstract

Background:

Hepatic dysfunction in the cancer unit has a significant impact on patient outcomes. The therapeutic application of anthracycline antibiotics are limited by side-effects mainly myelosuppression, chronic cardiotoxicity, and hepatotoxicity.

Aim:

To assess the risk of Hepatotoxicity in breast cancer patients receiving Inj. Doxorubicin.

Subjects and Methods:

The investigation was a prospective study that was conducted in cancer patients receiving Inj. Doxorubicin doses of 50 mg/m2, and 75 mg/m2 at a South Indian tertiary care hospital. Sample collection was carried out from pre-chemotherapy to 4th cycle. Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT), serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT), direct bilirubin and total bilirubin were assessed to determine hepatotoxicity. Data were analyzed using unpaired t-test, Pearson correlation using Graph-Pad Prism version 5.00 for Windows, Graph-Pad Software, San Diego, California, USA, www.graphpad.com.

Results:

Breast cancer patients comprised 37% (49/132) of the total female cancer patient population, of which 46 patients with a mean age of 46.6 (13.4) years were included and 30.4% (14/46) patients were developed hepatotoxicity. The mean standard deviation of SGOT, SGPT, direct bilirubin, total bilirubin in the pre-chemotherapy cycle to fourth chemotherapy cycle were found to be 21.97 (5.798) U/L and 181.3 (103.6) U/L, 23.17 (6.237) U/L and 147.6 (90.9) U/L, 0.1351 (0.1186) mg/dL and 0.5445 (0.4587) mg/dL, 0.3094 (1.346) mg/dL and 2.7163 (1.898) mg/dL simultaneously where P < 0.05 which were statistically significant.

Conclusion:

There exist a strong correlation between the use of Inj. Doxorubicin and risk for developing hepatotoxicity. The health-care professionals dealing with breast cancer patients need to have awareness for hepatotoxicity with the use of Inj. Doxorubicin therapy.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Doxorubicin, Hepatotoxicity, Patient outcomes, South India

Introduction

Occurrence of organ dysfunction is a common phenomenon in the cancer unit and hepatic dysfunction in the cancer unit has a significant impact on patient outcomes and represents a substantial health-care burden, which requires consideration of hepatic function and probable or proven site of chemotherapy.[1] The therapeutic application of anthracycline antibiotics is limited by its side-effects mainly dose-dependent myelosuppression and chronic cardiotoxicity.[2] Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) is commonly used in the treatment of a wide range of cancers including, some leukemias and Hodgkin's lymphoma as well as cancers of the bladder, breast, stomach, lung, ovaries, thyroid, soft-tissue sarcoma, multiple myeloma, and others.[3] The exact mechanism of doxorubicin is complex and still somewhat unclear, though it is thought to interact with DNA by intercalation and inhibition of macromolecular biosynthesis.[4,5]

Hepatotoxicity can reproduce necrosis, steatosis, fibrosis, cholestasis, and vascular injury.[6] Liver injury caused during cancer chemotherapy treatment doesn’t always reflect hepatotoxic anticancer drugs, but also antibiotics, analgesics, anti-emetics or other medications. Host's susceptibility to liver injury may be affected by pre-existing medical problems, tumor, immunosuppression, hepatitis viruses, and other infections, and nutritional deficiencies or total parenteral nutrition. Hence, it is difficult to attribute liver injury to a toxic reaction.[7,8] Even though the liver performs many metabolic functions, yet proper quantitative markers for a liver function are not available in the routine practice. The stage or characterization of acute hepatotoxicity is mainly based on liver biopsy.[9] There are many pharmaceuticals, which can cause liver injury, but most hepatotoxic drug reactions are idiosyncratic either by immunologic mechanisms or variations in host metabolic response.[10] All these reactions are not typically dose-dependent. In general, pre-existing liver disease has little effect on elimination and toxicity of most drugs.[11,12]

Doxorubicin containing drug regimens are widely used in patients in breast cancer.[13] The incidence of the most common diverse toxicities resulting from its chemotherapy can be described as cardiotoxicity, hepatic, hematological and testicular toxicity.[14] The following study specifically, evaluated the incidence of hepatotoxicity with the use of Inj. Doxorubicin.

Subjects and Methods

The investigation was a prospective, analytical study that was conducted at Mahatma Gandhi Memorial (MGM) Hospital with prior approval by the Human Ethics Committee for Human Experimentation of MGM Hospital/Kakatiya Medical College, Warangal, Andhra Pradesh, India. This study was conducted among 49 consecutive treatment groups receiving 4 cycles of chemotherapy with Inj. Doxorubicin from January 2011 to May 2011. Sample size was calculated depending on the assumption to assess the hepatotoxicity, based on standard deviation (SD) calculation (P = 95%, P = 0.05). Patient recruitment is based on review of case sheets, findings from clinical assessment and final judgment of chief oncologist with recommended Inj. Doxorubicin doses of 50 mg/m2, and 75 mg/m2. Hepatotoxicity can be attributed to serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) and serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) greater than 3 times the normal range or an increase of bilirubin greater than 1.5 mg/dL. Inclusion criteria were age greater than 19 years and have received Inj. Doxorubicin at one of the conventional doses. Exclusion criteria were the ambulatory patients, terminally ill patients and development of hepatic dysfunction prior to Inj. Doxorubicin administration.

During the data collection patients were informed about the study using the patient information format and the written consents were obtained from the patient or their caregivers through patient consent form, which was previously designed. Baseline demographics were collected including, age, baseline hemoglobin and serum creatinine. Blood sample collection was carried out at pre-chemotherapy and follow-up was done up to 4th cycle.

Statistical analysis

All the data were analyzed using unpaired t-test, Pearson correlation using the software Graph-Pad Prism version 5.00 for Windows, Graph-Pad Software, San Diego, California, USA, www.graphpad.com. P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

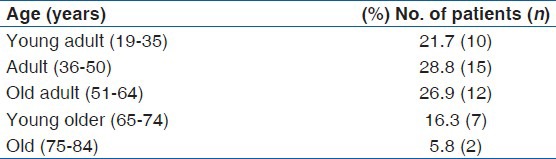

Breast cancer patients comprised 37% (49/132) of the total female cancer patient population, of which 46 patients with a mean age 46.6 (13.4) years were included based upon the predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria. The age distribution was given in Table 1. Habitat of the patients revealed that the 76.1% (35/46) were having rural background and 23.9% (11/48) were from the urban areas. The socio-demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 2. The main reasons for admission include nipple discharge in breast among 84.8% (39/46) and lumps in the breast among 15.2% (7/46) patients. Body mass index of the study population has shown that 36.9% (17/46) of the patients were having underweight. Of the patients included into the study, 30.4% (14/46) developed hepatotoxicity based upon the predefined criteria. There were no additive correlates for this adverse effect.

Table 1.

Age distribution of the patient group

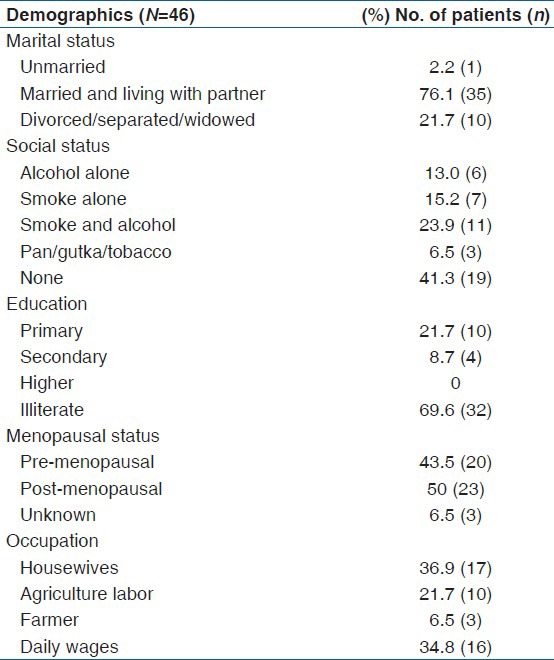

Table 2.

Socio-demographic variables of the patients

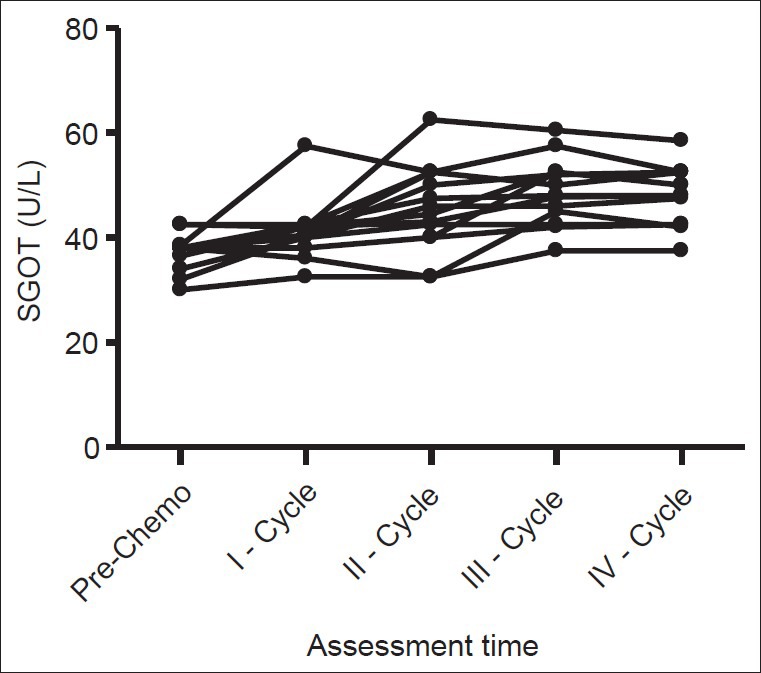

SGOT

The mean (SD) of SGOT in the pre-chemotherapy cycle to fourth chemotherapy cycle was observed to be 21.97 (5.798) U/L and 181.3 (103.6) U/L where the P < 0.001 which is statistically significant [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase levels during treatment among hepatotoxic patients

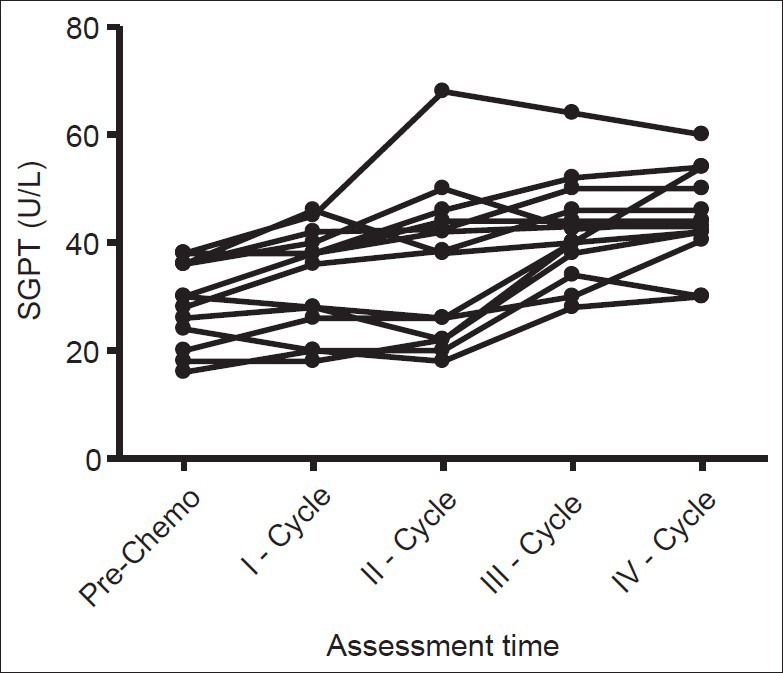

SGPT

The mean (SD) of SGPT in the pre-chemotherapy cycle to fourth chemotherapy cycle was observed to be 23.17 (6.237) U/L and 147.6 (90.9) U/L where the P < 0.001 which is statistically significant [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase levels during treatment among hepatotoxic patients

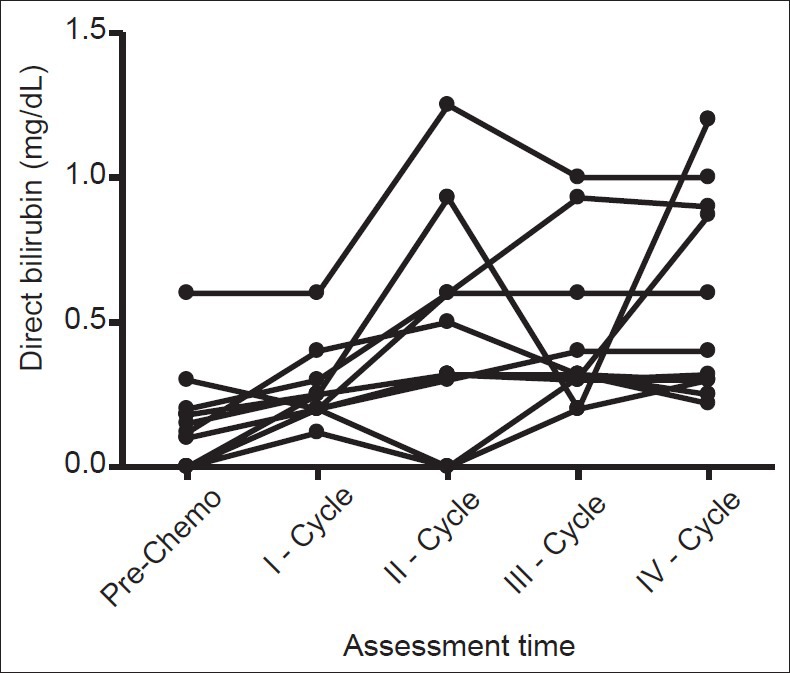

Direct bilirubin

The mean (SD) of Bilirubin in the pre-chemotherapy cycle to fourth chemotherapy cycle was observed to be 0.1351 (0.1186) mg/dL and 0.5445 (0.4587) mg/dL where the P = 0.04 which is statistically significant [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Direct bilirubin levels during treatment among hepatotoxic patients

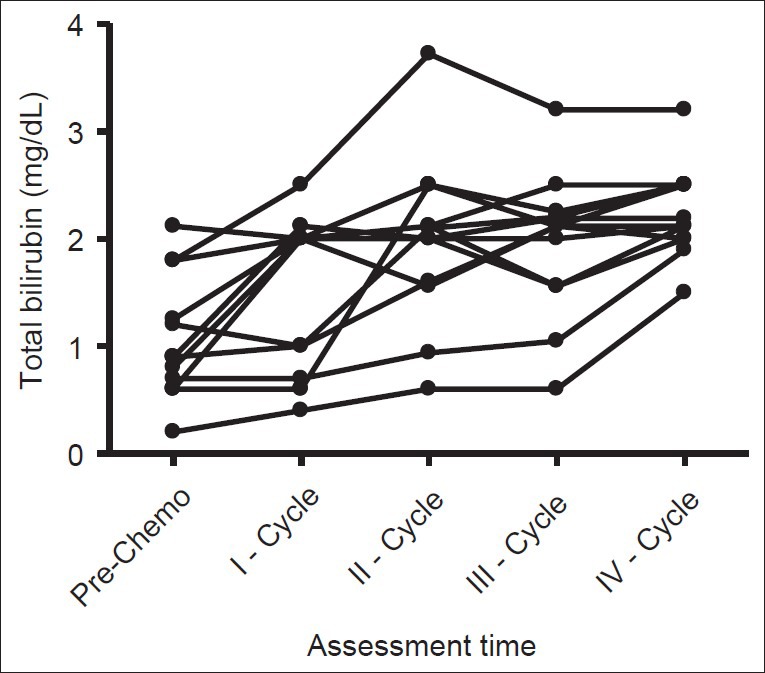

Total bilirubin

The mean (SD) of total bilirubin in the pre-chemotherapy cycle to fourth chemotherapy cycle was observed to be 0.3094 (1.346) mg/dL and 2.7163 (1.898) mg/dL where P = 0.03, which is statistically significant [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Total bilirubin levels during treatment among hepatotoxic patients

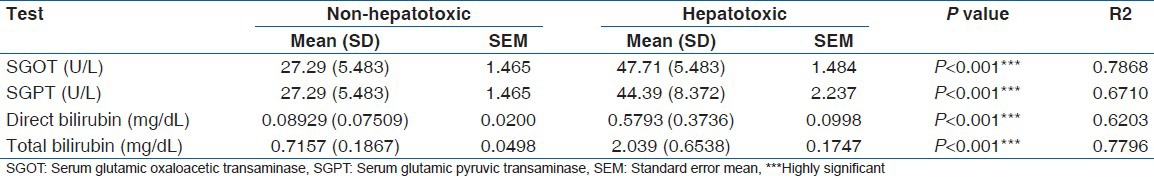

Similarly, the mean (SD) values for liver function tests of hepatotoxic and non-hepatotoxic patients were compared and found that there exists a highly significant (P < 0.001) difference between those two groups which is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Liver function tests of the non-hepatotoxic and hepatotoxic patient groups

Discussion

Liver dysfunction or liver damage, which is associated with an overload of hepatotoxins or hepatotoxicants is known as hepatotoxicity.[15] Breast cancer is having a major proportion among all type of cancers in this study site and the majority of them are from the low-socioeconomic status with a little knowledge about the risk factors of cancer.[16] Age distribution of the study population at this study site has shown that the adult population was mostly affected. A majority of the patients were having rural background, which constitutes about 76.1% (35/46) since this study site is having more rural areas surrounding it and 23.9% (11/46) patients came from urban areas. Among the total patients only 2.7% (1/46) were unmarried, 76.1% (35/46) were married and living with a partner and 21.7% (10/46) were divorced/separated/widowed. As the social status is having a direct relationship with the risk of getting cancers, we collected the information regarding social status of patients with a personal interview. In our study group 13.0% (6/46) were having the habit of alcoholism, 15.2% (7/46) were having the habit of smoking, 23.91% (11/46) were having both alcoholism and smoking, 6.5% (3/46) were having the habit of chewing Pan/Gutka/Tobacco and 41.30% (19/46) were having clean habits. These findings are similar to the past studies in South India.[17]

Of the total population, most of the patients were illiterate, which accounts for 69.6% (32/46), 21.7% (10/46) were having primary educational status, 8.7% (4/46) were having secondary level educational status. Higher educational status was zero in this patient group. These results are showing the poor educational status of this study group. Menopausal status has shown that the 43.5% (20/46) were in pre-menopausal status, 50% (23/46) were having the post-menopausal status and the menopausal status of 6.52% (3/46) patients is unknown because of reasons like unwillingness of patients to reveal. Occupationally 36.95% (17/46) patients were housewives, 21.7% (10/46) were agricultural labors, 6.5% (3/46) were farmers and 34.8% (16/46) were daily wages. As revealed by the patients the reasons for admission include nipple discharge in breast among 84.8% (39/46) patients, lumps in the breast among 15.2% (7/46) patients. These are the main symptoms they had experienced before the exact diagnosis of breast cancer. Body mass index of the patients were calculated during the patient recruitment and found that 36.9% (17/46) were underweight, 56.5% (26/46) were having normal weight and 6.5% (3/46) were having overweight. There were no obese patients in this study group. Since, the prevalence of underweight was more among these patients, there is a great need to provide dietary counseling based on their financial and educational status.[18]

Elevation of liver enzymes and function tests can often be difficult to determine in a patient clinical setting. Our investigation revealed that the incidence of hepatotoxicity associated with Inj. Doxorubicin was 30.4% (14/46) based upon our predefined criteria which were supported by the study of Llesuy and Arnaiz.[19] In a study by Yang et al., almost 40% of the patients suffered liver injury after doxorubicin treatment.[20] In order to evaluate hepatotoxicity in the study group, liver function tests such as, SGOT, SGPT, Direct Bilirubin, Total Bilirubin were assessed from pre-chemotherapy to completion of four chemotherapy cycles. Our criteria of utilizing elevation of transaminases and bilirubin have been reported by other investigators prior as a surrogate for liver function during drug therapy.[21] In this study, the mean (SD) of the SGOT in the pre-chemotherapy cycle and fourth chemotherapy cycle were found to be 21.97 (5.798) U/L and 181.3 (103.6) U/L simultaneously which is a significant increase (P < 0.001). Mean (SD) of SGPT was found to increased significantly (P < 0.001) from 23.17 (6.237) U/L to 147.6 (90.9) U/L. Direct Bilirubin was increased from 0.1351 (0.1186) mg/dL to 0.5445 (0.4587) mg/dL and Total Bilirubin was increased from 0.3094 (1.346) mg/dL to 2.7163 (1.898) mg/dL where P < 0.04 and P < 0.03 simultaneously, which were statistically significant. After controlling for concurrent hepatotoxic exposures (chemotherapy), there were no correlates (e.g. hemoglobin) for this adverse drug event when utilizing a multivariate logistic regression model.

Prior investigations by Llesuy and Arnaiz have determined that the administration of doxorubicin produced increases of 51% and 53% in liver spontaneous chemiluminescence and malonaldehyde formation respectively.[19] Characteristics of the population were an elevation in serum transaminases and bilirubin. The proposed mechanism for this observation centers on the free radical hypothesis that Doxorubicin undergoes one-electron reduction through nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) cytochrome P-450 reductase and decreases in antioxidant enzyme, Superoxide dismutase, and catalase activity while the increase in the malondialdehyde levels.[19,22,23] Similarly the mean (SD) values of SGOT, SGPT, direct bilirubin, total bilirubin of patients who have developed hepatotoxicity and patient group who didn’t develop hepatotoxicity were compared and found that there exists a highly significant (P < 0.001) difference between those two groups with reference to all liver function tests. Based on this study, it appears that Inj. Doxorubicin have the potential to develop hepatotoxicity, and precautions should be taken including optimizing the dosage pattern, providing appropriate concentration, dosage, and treatment schedule of antioxidants such as vitamin E, vitamin C, vitamin A, antioxidant components of virgin olive oil and selenium as dietary supplements as well as administration as chemotherapeutic agents, by which the anti-tumor action can be maximized and toxicity especially hepatotoxicity of Inj. Doxorubicin can be minimized.[24,25]

Limitations of the Study

The first limitation was that the cohort used to define our patient population for this study was split between the intensive care unit and oncology medicine floor at 24% and 76% respectively. Additional limitations include that the study is singl e-centered and contains relatively small number of patients. Another limitation of the study was that to truly see the effect of Inj. Doxorubicin on liver, it should be the only exposure to the patient. However, patients that would require Inj. Doxorubicin therapy may be exposed to additional hepatotoxins. The patient population that are receiving chemotherapy often have underlying disease process (i.e., cancer) and/or exposure to risk factors (i.e., medications, intravenous contrast) for the development of hepatotoxicity.

Conclusion

From these results, we can conclude that there exist a strong correlation between the use of Inj. Doxorubicin and risk for developing hepatotoxicity among the breast cancer patients at this study site. These findings are showing that the health-care professionals need to have awareness for hepatotoxicity with the use of Inj. Doxorubicin therapy. A weakness of our analysis is that it may not include the statistical correlations of socio-demographic factors such as age, dose escalation, or cumulative dose. There are multiple reasons for and consequences of hepatotoxicity in this population and there is a need for future interventions to target each specific aspect of hepatotoxicity.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Vaagdevi College of Pharmacy/Kakatiya University, Mahatma Gandhi Memorial (MGM) Hospital, St. Ann's Hospital, Warangal, Andhra Pradesh, India and All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE), New Delhi, India.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Vaagdevi College of Pharmacy/Kakatiya University, Warangal, Andhra Pradesh and All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE), New Delhi, India

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Superfin D, Iannucci AA, Davies AM. Commentary: Oncologic drugs in patients with organ dysfunction: A summary. Oncologist. 2007;12:1070–83. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-9-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson IC, Frei E., 3rd Adriamycin cardiotoxicity. Am Heart J. 1980;99:671–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(80)90743-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Archived 2007 April 3 at the Wayback Machine; [Last updated on: 1999 June 15; Retrieved on 2011 January 26]. “Doxorubicin (Systemic).” Mayo Clinic. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fornari FA, Randolph JK, Yalowich JC, Ritke MK, Gewirtz DA. Interference by doxorubicin with DNA unwinding in MCF-7 breast tumor cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:649–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Momparler RL, Karon M, Siegel SE, Avila F. Effect of adriamycin on DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis in cell-free systems and intact cells. Cancer Res. 1976;36:2891–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishak KG, Zimmerman HJ. Morphologic spectrum of drug-induced hepatic disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1995;24:759–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bénichou C. Criteria of drug-induced liver disorders. Report of an international consensus meeting. J Hepatol. 1990;11:272–6. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90124-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maria VA, Victorino RM. Development and validation of a clinical scale for the diagnosis of drug-induced hepatitis. Hepatology. 1997;26:664–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pratt DS, Kaplan MM. Evaluation of abnormal liver-enzyme results in asymptomatic patients. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1266–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004273421707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee WM. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1118–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510263331706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huet PM, Villeneuve JP, Fenyves D. Drug elimination in chronic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 1997;26(Suppl 2):63–72. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80498-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schenker S, Martin RR, Hoyumpa AM. Antecedent liver disease and drug toxicity. J Hepatol. 1999;31:1098–105. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(99)80325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardenbergh PH, Recht A, Gollamudi S, Come SE, Hayes DF, Shulman LN, et al. Treatment-related toxicity from a randomized trial of the sequencing of doxorubicin and radiation therapy in patients treated for early stage breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45:69–72. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohan M, Kamble S, Satyanarayana J, Nageshwar M, Reddy N. Protective effect of Solanum torvum on Doxorubicin-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Int J Drug Dev Res. 2011;3:131–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navarro VJ, Senior JR. Drug-related hepatotoxicity. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:731–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damodar G, Smitha T, Gopinath S, Vijayakumar S, Rao YA. Assessment of quality of life in breast cancer patients at a tertiary care hospital. Arch Pharma Pract. 2013;4:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damodar G, Smitha T, Rao YA. A descriptive epidemiological study of cancers at a South Indian tertiary care hospital. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci. 2011;2:907–15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Damodar G, Vijayakumar S. Implementation of dietary counselling for low socioeconomic cancer patients: A review. Int J Comm Pharm. 2011;4:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Llesuy SF, Arnaiz SL. Hepatotoxicity of mitoxantrone and doxorubicin. Toxicology. 1990;63:187–98. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(90)90042-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang XL, Fan CH, Zhu HS. Photo-induced cytotoxicity of malonic acid C (60) fullerene derivatives and its mechanism. Toxicol in vitro. 2002;16:41–6. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(01)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Floyd J, Mirza I, Sachs B, Perry MC. Hepatotoxicity of chemotherapy. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:50–67. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee V, Randhawa AK, Singal PK. Adriamycin-induced myocardial dysfunction in vitro is mediated by free radicals. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:H989–95. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.4.H989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalender Y, Yel M, Kalender S. Doxorubicin hepatotoxicity and hepatic free radical metabolism in rats. The effects of vitamin E and catechin. Toxicology. 2005;209:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Jungsuwadee P, Vore M, Butterfield DA, St Clair DK. Collateral damage in cancer chemotherapy: Oxidative stress in nontargeted tissues. Mol Interv. 2007;7:147–56. doi: 10.1124/mi.7.3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Granados-Principal S, Quiles JL, Ramirez-Tortosa CL, Sanchez-Rovira P, Ramirez-Tortosa MC. New advances in molecular mechanisms and the prevention of adriamycin toxicity by antioxidant nutrients. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:1425–38. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]