Abstract

Background/Aims:

Recent studies have revealed that Glasgow prognostic score (GPS), an inflammation-based prognostic score, is inversely related to prognosis in a variety of cancers; high levels of GPS is associated with poor prognosis. However, few studies regarding GPS in esophageal cancer (EC) are available. The aim of this study was to determine whether the GPS is useful for predicting cancer-specific survival (CSS) of patients for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC).

Patients and Methods:

The GPS was calculated on the basis of admission data as follows: Patients with elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level (>10 mg/L) and hypoalbuminemia (<35 g/L) were assigned to GPS2. Patients with one or no abnormal value were assigned to GPS1 or GPS0, respectively.

Results:

Our study showed that GPS was associated with tumor size, depth of invasion, and nodal metastasis (P < 0.001). In addition, there was a negative correlation between the serum CRP and albumin (r = −0.412, P < 0.001). The 5-year CSS in patients with GPS0, GPS1, and GPS2 were 60.8%, 34.7% and 10.7%, respectively (P < 0.001). Multivariate analysis showed that GPS was a significant predictor of CSS. GPS1-2 had a hazard ratio (HR) of 2.399 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.805-3.190] for 1-year CSS (P < 0.001) and 1.907 (95% CI: 1.608-2.262) for 5-year CSS (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

High levels of GPS is associated with tumor progression. GPS can be considered as an independent prognostic factor in patients who underwent esophagectomy for ESCC.

Keywords: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, glasgow prognostic score, prognostic factor, survival

Esophageal cancer (EC) is the eighth most common cancer worldwide, with 482,000 new cases estimated in 2008, and the sixth most common cause of death from cancer with 407,000 deaths.[1] The estimated overall age-adjusted incidence rate (standardized for world population) in 2008 was 5.7/100,000.[1] According to the Chinese national annual cancer registration reports, the incidence rate of EC was 20.9/100,000 in 2008.[2] In China, the crude mortality rate of EC in 2005 was 15.2/100,000, which represented 11.2% of all cancer deaths and ranked as the fourth most common cause of cancer death.[3] Thus, although the age-standardized mortality of EC decreased by 41.6% from 1973 to 2005, China still suffers a great disease burden from EC.[3] Although advancements have occurred in the multidisciplinary treatment, surgical resection remains the modality of choice. The 5-year overall survival after surgery is poor, the reason for that is the relatively late stage of diagnosis and rapid clinical progression.[4,5] Therefore, assessing the prognostic factors in EC patients will become more and more important.

Over the past few decades, a number of prognostic factors for EC have been identified, including lymph node status, depth of invasion, TNM stage, and other miscellaneous factors.[6,7] The Glasgow prognostic score (GPS) combines C-reactive protein (CRP) and albumin into a risk stratification score for prognosis of clinical outcome in cancer patients. Recent studies have revealed that GPS is inversely related to prognosis in a variety of cancers, such as colorectal cancer,[8,9] gastric cancer,[10] pancreatic cancer,[11] lung cancer,[12] and prostate cancer.[13] However, few studies regarding GPS in EC are available.[14,15] Furthermore, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is the most common pathological type in China, in contrast to the predominance of adenocarcinoma in the Western world. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine whether the GPS is useful for predicting postoperative survival of patients after esophagectomy for ESCC.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

A total of 1048 patients who underwent esophagectomy for EC at the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Zhejiang Cancer Hospital (Hangzhou, China), from January 2005 to December 2008 were eligible for this study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) ESCC confirmed by histopathology; (2) surgery with curative esophagectomy; (3) at least six nodes were examined for pathological diagnosis; (4) surgery was neither preceded nor followed by chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy; and (5) preoperative serum CRP and albumin were obtained before esophagectomy within 1 week. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) non-ESCC or gastroesophageal junction carcinoma; (2) previous or concomitant other cancer; (3) previous or concomitant esophagectomy for benign disease; (4) incomplete resection with microscopic or macroscopic residual tumors; (5) previous chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy; (6) previous anti-inflammatory medicines within 1 week; or (7) distant metastatic disease. All subjects gave written informed consent to the study protocol, which was approved by the Ethical Committees of Zhejiang Cancer Hospital (Hangzhou, China).

Surgery

The standard surgical approach consisted of a limited thoracotomy on the right side and intrathoracic gastric reconstruction (Ivor Lewis) for lesions at the middle/lower third of the esophagus. Upper third lesions were treated by cervical anastomosis (McKeown). In our institute, the majority of patients underwent two-field lymphadenectomy. In this cohort of patients, thoracoabdominal lymphadenectomy was performed, including the subcarinal, paraesophageal, pulmonary ligament, diaphragmatic and paracardial lymph nodes, as well as those located along the lesser gastric curvature, the origin of the left gastric artery, the celiac trunk, the common hepatic artery, and the splenic artery. Three-field lymphadenectomy was performed only if the cervical lymph nodes were thought to be abnormal upon preoperative evaluation.

Pathological analysis

The diagnosis of ESCC was confirmed by histopathology. The fresh specimen was routinely dissected and measured by surgeons immediately after resection of the tumor. The length of each tumor was measured with a handheld ruler and was recorded in the operation notes. Then the specimens were sent for histopathology examination after preservation in 10% formalin. The differentiation, vessel involvement, perineural invasion, depth of invasion, and nodal metastasis were recorded according to the results of pathologic reports. All patients were staged according to the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual.[16]

Follow-up

In our institute, patients were followed up at our outpatient department every 3-6 months for the first 2 years after resection, then annually. Recording of medical history, physical examination, and computed tomography of the chest were performed during the follow-up. Endoscopy was obtained in cases of clinically indicated recurrence or metastasis. As this series described the prognosis of patients with ESCC, a cancer-specific survival (CSS) analysis was more appropriate. Therefore, the CSS was ascertained in this study. The median follow-up for the entire cohort was 45 months. The last follow-up was November 30, 2011.

GPS evaluation

For evaluation of the GPS, blood test results from the day before surgery were used. GPS was constructed as previously described.[7,9] Patients with both an elevated CRP (>10 mg/L) and hypoalbuminemia (<35 g/L) were allocated a score of 2 (GPS2). Accordingly, patients with neither of these abnormalities were allocated a score of 0 (GPS0). Remaining patients in whom only one of the biochemical parameters was abnormal were assigned a score of 1 (GPS1).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Pearson Chi-squared test was used to determine the significance of differences for dichotomous variables. The Pearson's correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the correlation between CRP and albumin with the logarithmic model. A univariate analysis was used to examine the association between various prognostic predictors and CSS. Possible prognostic factors (P < 0.05) associated with CSS on univariate analysis were considered in a multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis with the enter method. The CSS was calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and the difference was assessed by the log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to quantify the strength of the association between predictors and survival. A P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Four hundred and ninety-three patients with ESCC were included in this study. Among the 493 patients, 73 (14.8%) were women and 420 (85.2%) were men. The mean age was 59.1 ± 7.9 years, with an age range from 34 to 80 years. Three hundred and sixteen (64.1%) patients were allocated a GPS of 0, 121 (24.5%) patients were allocated a GPS of 1, and 56 (11.4%) patients were allocated a GPS of 2, respectively.

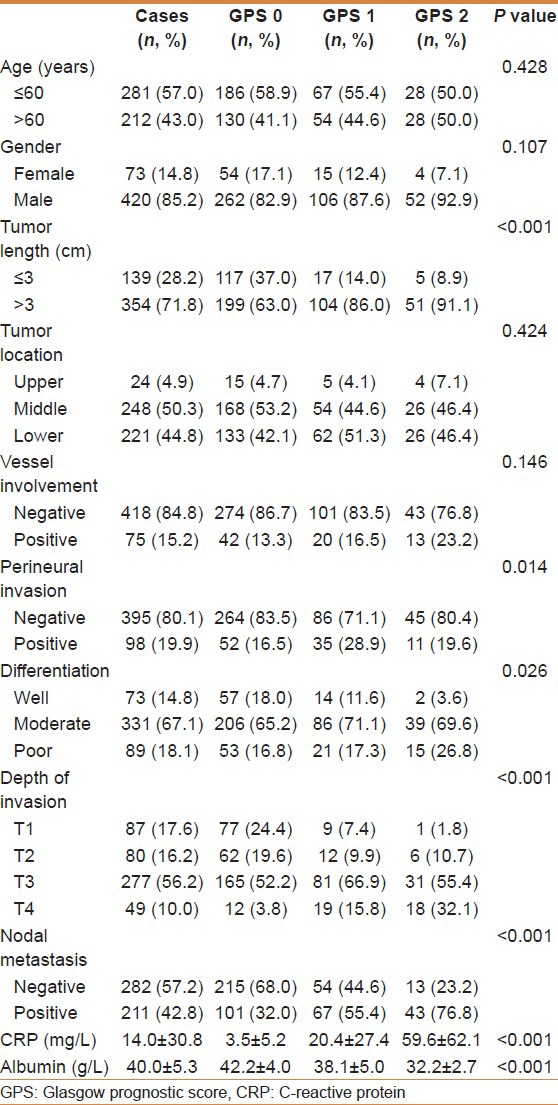

Correlation of GPS with clinicopathological characteristics

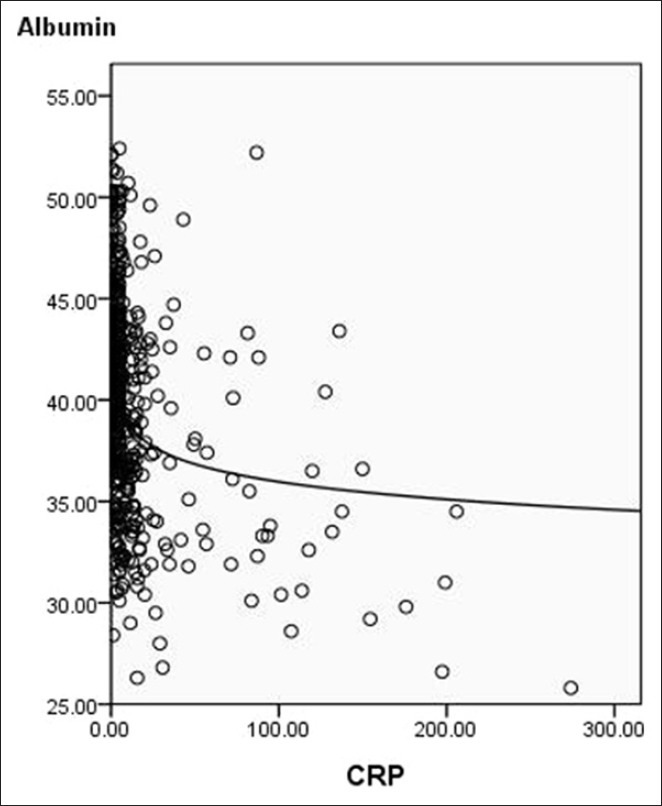

The relationships between the GPS and clinicopathological characteristics of the 493 patients who underwent surgery for ESCC are shown in Table 1. Our study showed that GPS was associated with tumor size, depth of invasion, and nodal metastasis (P < 0.001). In addition, there was a negative correlation between the CRP and albumin (r = −0.412, P < 0.001) [Figure 1].

Table 1.

The relationship between GPS and clinicopathological characteristics

Figure 1.

Correlation between C-reactive protein and albumin (r = −0.412, P < 0.001)

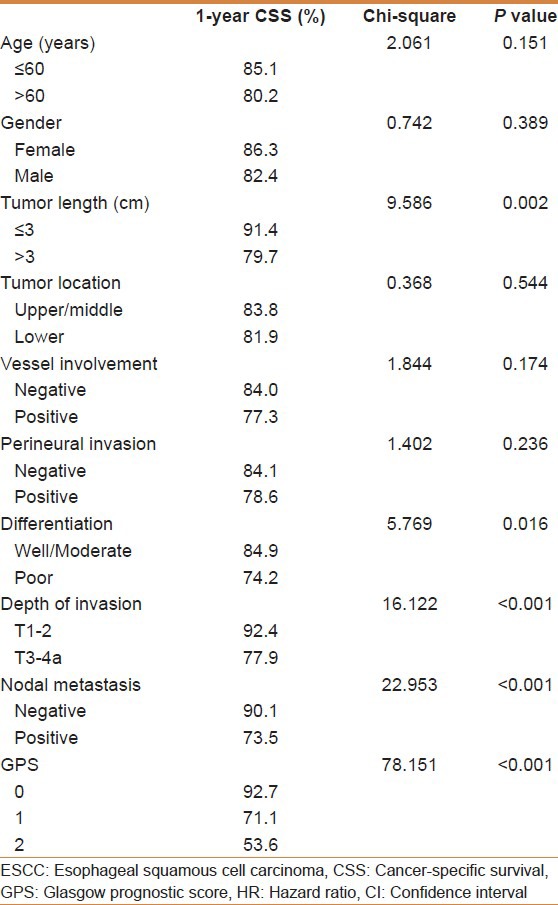

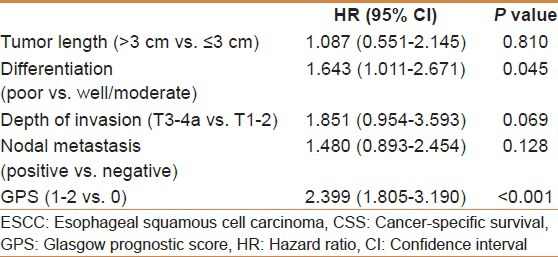

One-year CSS and prognostic factors

The 1-year CSS in patients with GPS0, GPS1, and GPS2 were 92.7%, 71.1%, and 53.6%, respectively (P < 0.001). By univariate analysis, we found five clinicopathological variables had significant associations with the 1-year CSS [Table 2]. Then all of the five variables above were included in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model (enter procedure) to adjust the effects of covariates. In that model, we demonstrated that differentiation (P = 0.045) and GPS (P < 0.001) were independent prognostic factors [Table 3].

Table 2.

SCCE to ESCC

Table 3.

SCCE to ESCC

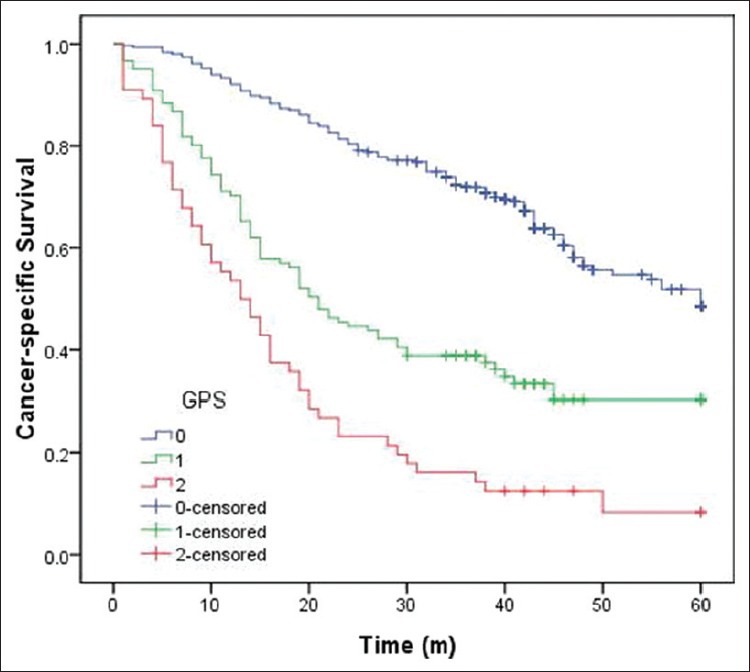

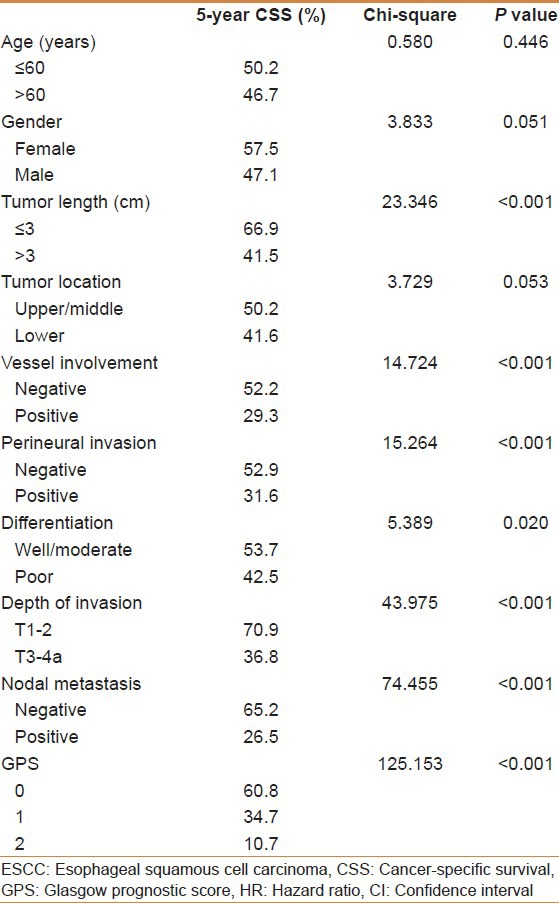

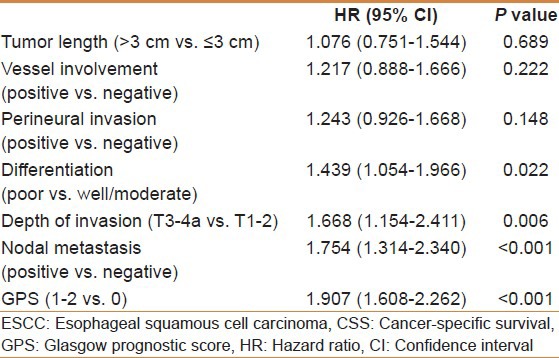

Five-year CSS and prognostic factors

The 5-year CSS in patients with GPS0, GPS1, and GPS2 were 60.8%, 34.7%, and 10.7%, respectively (P < 0.001) [Figure 2]. Univariate analyses showed that tumor length, vessel involvement, perineural invasion, differentiation, depth of invasion, nodal metastasis, and GPS were predictive of CSS [Table 4]. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that differentiation (P = 0.022), depth of invasion (P = 0.006), nodal metastasis (P < 0.001), and GPS (P < 0.001) were independent prognostic factors [Table 5].

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves stratified by Glasgow prognostic score (GPS). The 5-year cancer-specific survival in patients with GPS0, GPS1, and GPS2 were 60.8%, 34.7%, and 10.7%, respectively (P < 0.001)

Table 4.

SCCE to ESCC

Table 5.

SCCE to ESCC

DISCUSSION

There is a strong linkage between inflammation and cancer. A systemic chemotherapy or radiation will inevitably have an impact on the systemic inflammation. Thus, evaluation of GPS in neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemoradiotherapy does not reflect the baseline impact of systemic inflammation on clinical outcome in EC patients. Thus, in our study, we evaluate the potential prognostic role of GPS in patients undergoing esophagectomy for ESCC without neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment. Our study demonstrated that GPS is associated with prognosis and can be considered as an independent prognostic marker in patients who underwent esophagectomy for ESCC.

It is well known that cancer promotes release of proinflammatory cytokines from tumor cells. The cytokines interact with immunovascular system and facilitate tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis.[17,18] Recent studies have shown that elevated serum CRP levels may be associated with tumor size, depth of invasion, and nodal metastasis, resulting in poor prognosis in patients with various cancers, including EC.[19,20,21] It has been also reported that serum albumin participates in systemic inflammatory response and that decline of its serum level is a poor prognostic factor for long-term survival in patients with various cancers.[22,23] Based on these reports, GPS, incorporating CRP and serum albumin levels, may reflect both the presence of the systemic inflammatory response and the progressive nutritional decline in patients with cancers.[24]

Our study showed that GPS was associated with tumor size, depth of invasion, and nodal metastasis. This observation is in line with data from Vashist et al.,[15] but is contrary to the result of Kobayashi et al.,[14] who suggested that GPS has no significant correlation with the above clinicopathological factors. However, the results of our study were consistent with the prognostic value of the GPS previously reported.[14,15] Crumley et al.[25] revealed that the GPS predicts CSS in patients with inoperable gastroesophageal cancers. Kobayashi et al.[14] also reported that GPS determined before treatment is an independent predictor of survival of patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery, although their study was limited to 48 cases only. From the database of 493 consecutive patients with ESCC who underwent surgery, our results clearly demonstrated that GPS can serve as an independent predictor of long-term survival for patients with ESCC.

There were several potential limitations in our study. The prognostic analysis was retrospective, the mean follow-up duration was short, and the study was conducted by a single institution. Furthermore, we excluded patients who had adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, which may have influenced our analysis. Thus, larger prospective studies will need to be performed to confirm these preliminary results.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that high levels of GPS is associated with tumor progression. GPS can be considered as an independent prognostic factor of in patients who underwent esophagectomy for ESCC. However, the prognostic value of the GPS remains to be formally tested within the context of such randomized trials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Ms. Ying Huang (Department of Nursing, Zhejiang Cancer Hospital) for data collection and statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beijing: Military Medical Sciences; 2012. National Cancer Center. Cancer Registration Annual Report 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beijing: Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College Press; 2008. Ministry of Health of the people's republic of China. Report of the 3rd national retrospective survey of death causes in China. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siersema PD, van Hillegersberg R. Treatment of locally advanced esophageal cancer with surgery and chemoradiation. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:535–40. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283025ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tachibana M, Kinugasa S, Hirahara N, Yoshimura H. Lymph node classification of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:427–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peyre CG, Hagen JA, DeMeester SR, Altorki NK, Ancona E, Griffin SM, et al. The number of lymph nodes removed predicts survival in esophageal cancer: An international study on the impact of extent of surgical resection. Ann Surg. 2008;248:549–56. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318188c474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wijnhoven BP, Tran KT, Esterman A, Watson DI, Tilanus HW. An evaluation of prognostic factors and tumor staging of resected carcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Surg. 2007;245:717–25. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251703.35919.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMillan DC, Crozier JE, Canna K, Angerson WJ, McArdle CS. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score (GPS) in patients undergoing resection for colon and rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:881–6. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishizuka M, Nagata H, Takagi K, Horie T, Kubota K. Inflammation-based prognostic score is a novel predictor of postoperative outcome in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2007;246:1047–51. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181454171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutta S, Crumley AB, Fullarton GM, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. Comparison of the prognostic value of tumour and patient related factors in patients undergoing potentially curative resection of gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2012;204:294–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamieson NB, Denley SM, Logue J, MacKenzie DJ, Foulis AK, Dickson EJ, et al. A prospective comparison of the prognostic value of tumor- and patient-related factors in patients undergoing potentially curative surgery for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2318–28. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1560-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dunlop DJ. Comparison of an inflammation-based prognostic score (GPS) with performance status (ECOG) in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy for inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1704–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shafique K, Proctor MJ, McMillan DC, Leung H, Smith K, Sloan B, et al. The modified Glasgow prognostic score in prostate cancer: Results from a retrospective clinical series of 744 patients. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:292. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi T, Teruya M, Kishiki T, Endo D, Takenaka Y, Tanaka H, et al. Inflammation-based prognostic score, prior to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, predicts postoperative outcome in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Surgery. 2008;144:729–35. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vashist YK, Loos J, Dedow J, Tachezy M, Uzunoglu G, Kutup A, et al. Glasgow Prognostic Score is a predictor of perioperative and long-term outcome in patients with only surgically treated esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1130–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rice TW, Rusch VW, Ishwaran H, Blackstone EH Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration. Cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: Data-driven staging for the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union Against Cancer Staging Manuals. Cancer. 2010;116:3763–73. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: Back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–44. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto K, Ikeda Y, Korenaga D, Tanoue K, Hamatake M, Kawasaki K, et al. The impact of preoperative serum C-reactive protein on the prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:1856–64. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nozoe T, Saeki H, Sugimachi K. Significance of pre-operative elevation of serum C-reactive protein as an indicator of prognosis in esophageal carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2001;182:197–201. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00684-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimada H, Nabeya Y, Okazumi S, Matsubara H, Shiratori T, Aoki T, et al. Elevation of pre-operative serum C-reactive protein level is related to poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2003;83:248–52. doi: 10.1002/jso.10275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crumley AB, Stuart RC, McKernan M, McMillan DC. Is hypoalbuminemia an independent prognostic factor in patients with gastric cancer? World J Surg. 2010;34:2393–8. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0641-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandrasinghe PC, Ediriweera DS, Kumarage SK, Deen KI. Pre-operative hypoalbuminaemia predicts poor overall survival in rectal cancer: A retrospective cohort analysis. BMC Clin Pathol. 2013;13:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6890-13-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMillan DC. An inflammation-based prognostic score and its role in the nutrition-based management of patients with cancer. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67:257–62. doi: 10.1017/S0029665108007131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crumley AB, McMillan DC, McKernan M, McDonald AC, Stuart RC. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score in patients with inoperable gastro- oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:637–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]