Abstract

Background: Dementia is a progressive terminal illness which requires decisions around aggressiveness of care.

Objective: The study objective was to examine the rate of intensive care unit (ICU) utilization and its regional variation among persons with both advanced cognitive and severe functional impairment.

Methods: We utilized the Minimum Data Set (MDS) to identify a cohort of decedents between 2000 and 2007 who (1) were in a nursing home (NH) 120 days prior to death and (2) had an MDS assessment indicating advanced cognitive and functional impairment as identified by cognitive performance scale (CPS) ≥5 and total dependence or extensive assistance in seven activities of daily living (ADLs). ICU utilization in the last 30 days of life was determined from Medicare claims files. A multivariate logistic regression model examined the likelihood of ICU admission in 2007 versus 2000 adjusting for sociodemographics, orders to limit life sustaining treatment, and health status.

Results: Among 474,829 Medicare NH residents with advanced cognitive impairment followed during 2000–2007, we observed an increase in ICU utilization from 6.1% in 2000 to 9.5% in 2007. After adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics, orders to limit life sustaining treatment, and measures of health status, the likelihood of a resident being admitted to an ICU was higher in 2007 compared to 2000 (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.71, 95% CI 1.60–1.81). Additionally, substantial regional variation was noted in ICU utilization, from 0.82% in Montana to 22% in the District of Columbia.

Conclusions: Even among patients with advanced cognitive and functional impairment, ICU utilization in the last 30 days increased and varied by geographic region.

Introduction

Dementia is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States, with estimated health care costs ranging from 157–215 billion dollars in 2010. The cost to Medicare was approximately 11 billion dollars.1,2 The financial cost is only a portion of the impact on patient and family. Dementia is a devastating illness which brings suffering to those afflicted, their family and friends. Loved ones watch helplessly as their family member loses memories, functional capacity, and their entire personality. Without hope of disease altering treatment, families often wish for comfort care and a focus on quality of life. Dementia is a progressive terminal illness with infection and eating difficulty being common complications in the final stages.3,4 The development of these expected complications often leads to hospitalization. Research has demonstrated that the transition from the permanent care facility to the hospital and back can be burdensome to patients and families.4–6 Health care transitions can lead to aggressive interventions, medical errors, and adverse reactions.3,4 Such hospitalizations, which can result in aggressive interventions such as feeding tube placement and use of the intensive care unit (ICU), seem at odds with families' stated goal of comfort care.3

Such decisions regarding hospitalization should take into account the patient's stated goals of care. Increasingly, court cases, professional guidelines, and legislation, such as the 1991 Patient Self-Determination Act, have increased the focus on patient autonomy. Our intent is to aid in decision making regarding hospitalization by examining ICU utilization in light of expected outcomes in patients with advanced cognitive impairment. Using nationwide data from the Minimum Data Set (MDS) and Medicare claims files from 2000 to 2007, the objectives of the study were to describe the rate of ICU admission within the last 30 days of life among NH residents with severe cognitive and functional impairment, and to describe regional variation and temporal trends of these rates.

Methods

Study population

The study included nationwide data from the MDS of individuals residing in a NH in the United States. This MDS data was linked with Medicare claims files from 2000 through 2007. The study population included persons with advanced cognitive and functional impairment based on the MDS. Advanced cognitive impairment was defined as a cognitive performance scale (CPS) score ≥5. A CPS score of 5 to 6 (on a scale ranging from 0 to 6, with 0 being cognitively intact and 6 being severely impaired with trouble eating) corresponds to a score of 5.1 to 5.3 on the mini-mental state examination (on which a score below 24 indicates cognitive impairment, on a scale of 0–30)4,7 Severe functional impairment is based on the seven items of the MDS activities of daily living (ADL) scale indicating total dependence or extensive assistance needed in all seven ADL items. Functional status was measured using staff-based functional status assessments on a 28-point scale that rated each of the seven basic ADLs on a scale from 0 to 4, with a higher score indicating more functional impairment. Additionally subjects must have been (1) insured by fee for service Medicare; (2) resident of the nursing home (NH) 120 days before death; and (3) age >66 years old.

Measures

ICU utilization was based on examining Medicare claims files indicating that patients received care in an ICU in the last 30 days of life. Sociodemographic data was taken from the MDS, while age was based on the Medicare denominator file. Information on health status was derived from the MDS assessment done closest to 120 days prior to death. Health status measures included comorbid medical conditions, functional status, weight loss, swallowing problems, pneumonia in the prior seven days, orders to forgo life sustaining treatment, written advance directives, and stability of patient condition as rated by NH staff. Comorbid medical conditions included were diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, hip fracture, stroke, coronary artery disease, renal disease, type of dementia, and cancer. Advance directives and orders to forgo life sustaining treatment included the presence of the following: durable power of attorney (DPOA) for health care, living will, do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order, and do-not-hospitalize (DNH) order.

Analysis

The characteristics of subjects were described for the entire cohort with simple frequencies and means for continuous variables. The percentage of subjects in each state (categorized into quartiles) with an ICU stay was displayed as a map of the United States. A multivariate logistic model was used, controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, advance directives, orders to forgo life sustaining treatment, health measures listed above, the MDS-CHESS (Changes in Health, End-stage dis-ease and Symptoms and Signs) score, and year of death. The unit of analysis was the NH resident, with the clustering of NH residents in hospital referral regions accounted for by a robust variance estimator. All analyses were done using Stata statistical software version 12.0 (StataCorp., College Station, TX).

Results

Sample description

The sample included 474,829 NH residents who had advanced cognitive impairment and functional impairment based on the MDS assessment completed within 120 days prior to death. A total of 54% of the cohort had difficulty swallowing or chewing, 73% had a DNR order, 15% had substantial weight loss, and 27% had feeding tubes. The mean age was 85.9±7.6 years; 79% were women, 83% were white. and 38% had less than a high school education level. The majority of residents had a DNR order (73%), but only 36% had an identified DPOA, 7% had DNR orders, and only 12% had an order not to insert a feeding tube (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics: ICU Utilization in Advanced Dementia

| Characteristic | Entire cohort | No ICU stay in the last 30 days of life | ICU stay in the last 30 days of life | Selected adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 85.9 (7.7 SD) | 86.1 (7.6 SD) | 83.6 (7.6 SD) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 77.9 | 78.6 | 69.7 | |

| Male | 22.0 | 21.3 | 30.2 | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) |

| Race | ||||

| American Indian | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) |

| Asian | 1.2 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 1.5 (1.2–2.0) |

| Black | 12.0 | 10.8 | 26.5 | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) |

| Hispanic | 3.3 | 2.9 | 8.3 | 2.0 (1.6–2.6) |

| White | 83.0 | 84.7 | 62.3 | |

| Level of education | ||||

| No school | 2.0 | 1.9 | 3.1 | |

| 8th grade | 24.6 | 24.3 | 28.8 | |

| 9th–11th grade | 11.3 | 11.2 | 12.9 | |

| High school | 31.2 | 31.2 | 30.4 | |

| Technical | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.0 | |

| Some college | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.1 | |

| Bachelor's | 4.7 | 4.8 | 3.6 | |

| Graduate | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.1 | |

| DPOA identified | 35.6 | 36.8 | 21.1 | |

| DNR present | 73.0 | 75.8 | 38.3 | |

| DNR absent | 26.7 | 23.8 | 61.5 | 3.39 (3.2–3.6) |

| DNH present | 6.9 | 7.3 | 1.2 | |

| DNH absent | 92.8 | 92.3 | 98.6 | 3.1 (2.8–3.5) |

| Living will identified | 19.3 | 20.1 | 9.5 | |

| CPS | ||||

| 5=Severe | 17.9 | 18.2 | 14.6 | |

| 6=Very severe | 82.1 | 81.8 | 85.4 | |

| Medical diagnosis | ||||

| Diabetes | 23.7 | 22.8 | 35.2 | 1.2 (1.1–1.2) |

| Congestive heart failure | 14.4 | 14.2 | 18.0 | 1.2 (1.2–1.3) |

| Hip Fracture | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) |

| CVA | 29.3 | 28.5 | 38.8 | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) |

| Dementia not Alzheimer's | 30.5 | 30.7 | 28.3 | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) |

| Alzheimer's disease | 20.9 | 21.4 | 14.9 | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) |

| Hemiplegia-hemiparesis | 12.7 | 12.3 | 18.2 | |

| Multiple sclerosis | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | |

| Parkinson's disease | 6.2 | 6.3 | 5.4 | |

| COPD/emphysema | 8.5 | 8.2 | 12.3 | 1.3 (1.2–1.3) |

| Cancer | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) |

| Pneumonia | 4.7 | 4.3 | 8.6 | 1.2 (1.2–1.3) |

| Dehydrated | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | |

| Not consuming fluids last 3 days | 3.9 | 4.1 | 1.6 | |

| Recurring aspirations last 90 days | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.9 | |

| Unstable cognitive/ADL status | 43.0 | 42.9 | 44.3 | |

| Chewing problems | 53.2 | 53.7 | 47.5 | |

| Swallowing problems | 54.0 | 53.2 | 63.5 | |

| Weight loss | 15.4 | 15.6 | 13.4 | |

| Feeding tube present | 27.1 | 25.0 | 51.5 | 1.7 (1.7–1.8) |

ADL, activities of daily living, CPS, cognitive performance scale; DNH, do-not-hospitalize order; DNR, do-not-resuscitate order; DPOA, durable power of attorney; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation.

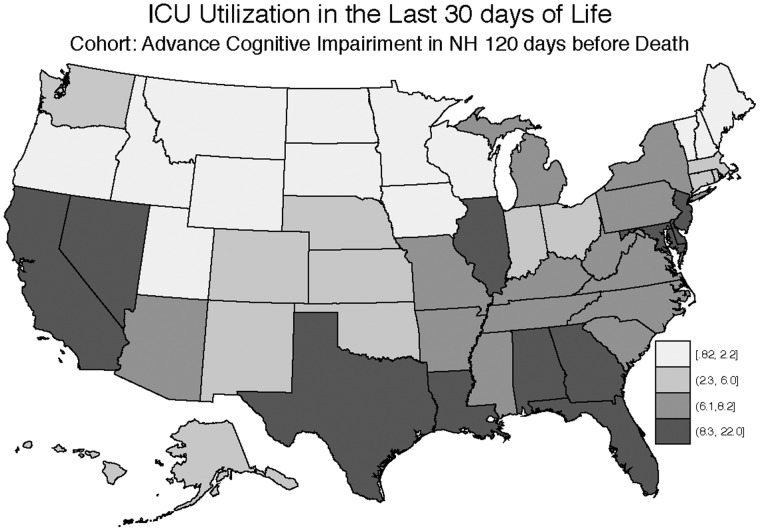

There was an increase in ICU admissions over the study period from 6.1% in 2000 to 9.5% in 2007. After multivariate adjustment, the likelihood of a resident being admitted to an ICU was higher in 2007 compared to 2000 (adjusted OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.60–1.81) (see Table 2). The rates of ICU utilization showed substantial variation across states as demonstrated in Figure 1. States like Texas (10.2%), California (13.7%), Louisiana (10.1%), and Florida (13.1%) had the highest ICU use rates; while Montana (0.82%), Vermont (0.86%), New Hampshire (1.2%), and Maine (1.5%) were among the lowest, with the overall range being 0.1%–22.0%.

Table 2.

Likelihood of ICU Admission Over Time

| ICU admission within 30 days of death by year | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Reference | |

| 2001 | 1.1 | 1.0 1.1 |

| 2002 | 1.2 | 1.1 1.2 |

| 2003 | 1.3 | 1.2 1.3 |

| 2004 | 1.4 | 1.3 1.5 |

| 2005 | 1.4 | 1.4 1.5 |

| 2006 | 1.6 | 1.5 1.7 |

| 2007 | 1.7 | 1.6 1.8 |

FIG. 1.

ICU utilization in the last 30 days of life in NH residents with advanced cognitive impairment. (Key indicates percent of NH residents in the United States who had an ICU stay within the last 30 days of life.)

A total of 35,993 residents (7.6%) had an admission to the ICU in the last 30 days of life. A multivariate logistic regression model revealed that being male (OR 1.1, 95% CI 1.1–1.2), black (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.4–1.6), Hispanic (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.6–2.6), or Asian (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.2–2.0) made having an ICU admission more likely. Other variables that made an ICU admission more likely were not having a DNR (OR 3.4, 95% CI 3.2–3.6) and having a feeding tube (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.7–1.8). Other measures of comorbidity associated with ICU utilization in the last 30 days of life are shown in Table 1.

Discussion

Despite the increasing recognition of dementia as progressive, fatal illness, we found that NH residents with advanced cognitive impairment and severe functional impairment demonstrated a rate of ICU utilization that increased from 6.1% in 2000 to 9.5% in 2007. Being nonwhite, having a feeding tube, or living in certain areas of the country increased likelihood of an ICU admission within the last 30 days of life. State to state variation was demonstrated for ICU utilization and was in the same pattern as previously reported in studies of feeding tube insertion and rate of burdensome transitions.4,10 Our finding that nearly one in ten NH residents with advanced cognitive impairment and severe functional impairment has an ICU stay appears to be at odds with family stated goals of care to focus on comfort.3

A second concern is the striking regional variation in ICU use in the last 30 days of life. Our previous work suggests NH residents residing in a geographic region with a high rate of burdensome transitions, such as multiple hospitalizations for the expected infectious complications of dementia, are not only more likely to experience ICU utilizations, but are more likely to have a stage IV decubitus ulcer in the last 30 days of life.4 The six-month mortality for patients after these complications develop is high, ranging from 38.6% (eating problem) to 46.7% (pneumonia)3 and is even higher for NH residents with advanced cognitive impairment hospitalized with two or more complications such as pneumonia or dehydration in the last 90 days. There is evidence to support successful treatment of the complications of advanced cognitive impairment in the NH setting.

Givens and colleagues evaluated comfort and survival in patients with dementia, with or without antimicrobial treatment, grouped by route of administration upon diagnosis with pneumonia.8 Antimicrobial therapy, by any route of administration, was associated with lower mortality and increased survival after pneumonia compared to no treatment. Comfort scores were highest for those persons who were not treated with antimicrobial agents and lowest for those who were treated.8 Those treated with intravenous agents had the lowest comfort rating.8 The patients who were treated with intravenous agents were typically hospitalized, while those on oral agents were managed in the NH setting. Furthermore, a randomized control trial by Loeb and colleagues demonstrated that there was no adverse impact on mortality or quality of life by treating pneumonia in the NH.9 Together this work lends support to the movement to maintain patients with advanced cognitive impairment in the NH or home and to either treat with oral agents or comfort care, rather than transfer to the acute care setting for more invasive intervention.

Our study has limitations that should be acknowledged. Information on detailed patient or family preferences was not available, though orders to forgo specific treatments are noted in the MDS. Information abstracted from the MDS is subject to coding errors. State to state variation in ICU utilization was demonstrated and could represent other factors that could not be elicited by this retrospective review. There might be particular attributes of the states and communities themselves that affected ICU utilization that could not be revealed by this study. More research is needed to better delineate the cause of such dramatic regional variation. A further limitation of our study is the use of a retrospective design that identified a cohort of NH residents who had advanced cognitive impairment before death. We tried to mitigate bias by limiting the cohort to those with a consistent diagnosis of advanced cognitive and functional impairment, and by observing them for a short period of time before death.

Under the current Medicare and Medicaid systems, a three-day hospitalization qualifies a NH resident for skilled services, which will be reimbursed to the NH at a higher rate than the Medicaid rate for room and board. As described by Ouslander in a recent perspective piece, a fundamental issue is that state Medicaid programs do not benefit from savings to Medicare from the prevention of hospitalization.11 Additionally, the NHs actually have financial incentives for sending a patient to the hospital, so that after a three-day stay they qualify for Medicare Part A payments for post-acute care in the NH when they return.11 These system-based incentives will require a comprehensive approach to financing, regulation, and public reporting regarding quality of care of the dual eligibles. Better NH staffing, increased geriatric training, and other interventions will need to follow as well.11

Our study provides further evidence of the need to improve the quality of decision making for patients at the end of life with advanced cognitive impairment. Families express a desire for comfort care for the NH resident with advanced cognitive impairment. Increasing ICU utilization is not consistent with the preferences of family, or with the evidence that demonstrates successful care, with increased comfort, in the NH. Caregivers and families should be helped to weigh the risks and benefits with a goal of making decisions that support quality of life, patient preference, and whenever possible that avoid aggressive and unnecessary interventions and multiple transitions with pain and discomfort.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cindy Williams, BS, for assistance in manuscript preparation and research review. ATF thanks Jose A. Tuya, Sr. for assistance in manuscript review for grammar and clarity.

Author Disclosure Statement

This project was supported by grants P01AG027296 and K24AG033640 (Dr. Mitchell) from the National Institute on Aging. Ana Tuya Fulton, MD, FACP, asserts that no competing financial interests exist. Pedro Gozalo, PhD, asserts that no competing financial interests exist. Susan L. Mitchell, MD, was supported by grant K24AG033640 from the National Institute on Aging. Vince Mor, PhD, was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health and AHRQ; he reports board membership of PointRight and HCR Manor Care. Joan M. Teno, MD, MS, was supported by grant P01AG027296 from the National Institute on Aging. Ms. Williams is employed by Brown University and assistance was part of her employment at Brown University; there was no external compensation.

References

- 1.Xu J, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Tejada-Vera B: Deaths: Final Data for 2007. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM: Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1326–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. : The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. : End-of-life transitions among nursing-home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med 2011;365:40–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB: Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:321–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrison RS, Siu AL: Survival in end-stage dementia following acute illness. JAMA 2000;284:47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. : MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol 1994;49:M174–M182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Givens JL, Jones RN, Schaffer ML, et al. : Survival and comfort after treatment of pneumonia in advanced dementia. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1102–1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loeb M, Carusone SC, Goeree R, et al. : Effect of a clinical pathway to reduce hospitalizations in nursing home residents with pneumonia: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006;295:2503–2510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teno JM, Mitchell SK, Kuo SK, et al. : Decision-making and outcomes of feeding tube insertions: A five-state study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:881–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ouslander JG, Berenson RA: Reducing unnecessary hospitalizations of nursing home residents. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1165–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]