Abstract

Background. Published data are equivocal about the relative rates of male-to-female and female-to-male human papillomavirus (HPV) transmission. Our objective was to estimate genital HPV incidence among heterosexual partners from a broad age range and to investigate the effects of monogamy and relationship duration on incidence.

Methods. HPV genotyping was conducted for heterosexual partners, aged 18–70 years, from Tampa, Florida, who provided genital exfoliated cell specimens at semiannual visits during a 2-year study. The rate of incident HPV detection was assessed for 99 couples, and transmission incidence was estimated among a subset of 65 discordant couples. We also evaluated the effect of monogamy and relationship duration on transmission incidence.

Results. Couples were followed up for a median of 25 months and had a mean age of 33 years for both sexes. The HPV type-specific transmission incidence rate was 12.3 (95% confidence interval, 7.1–19.6) per 1000 person-months for female-to-male transmission and 7.3 (95% confidence interval, 3.5–13.5) per 1000 person-months for male-to-female transmission. Regardless of monogamy status or relationship duration, there was a similar pattern of increased incident HPV detection among men compared with women.

Conclusions. HPV may be transmitted more often from women to men than from men to women, suggesting a need for prevention interventions, such as vaccination, for men.

Keywords: human papillomavirus, genitals, couples, epidemiology, transmission, incidence

Although the sexual transmission of human papillomavirus (HPV) is common [1], these infections are typically transient and asymptomatic; however, some infections will result in anogenital warts, dysplastic lesions, and/or neoplasms, which create a substantial disease burden in both sexes [2]. The prevention, screening, diagnosis and treatment of these HPV-associated diseases generate a considerable economic burden within societies [3].

Although HPV transmission between sexes is common, some aspects of HPV natural history seem to differ between heterosexual men and women. For example, the prevalence of genital HPV is higher among men than among women [4, 5]. Furthermore, incidence among men remains relatively stable across the life span [6] whereas incidence among women may decline [7]. Although men and women in these studies were from different populations, the differences suggest transmission rates may differ by sex; however, there have been few reports estimating HPV transmission incidence within couples, and these reports are equivocal regarding relative male-to-female and female-to-male transmission rates [8–11].

We reported elsewhere that monogamy was not associated with concordance of genital HPV among asymptomatic heterosexual couples [12]. Our objective in the current study was to characterize type-specific genital HPV incidence among heterosexual partners across a broad age range and to investigate the effects of monogamy and relationship duration on incidence. Understanding more about the natural history of HPV within these couples may provide new insights into prevention strategies.

METHODS

Between 2005 and 2009, men were recruited from the general community in the Tampa, Florida, area for enrollment in the prospective HPV in Men (HIM) Study. Its methods have been described in detail elsewhere [6]. Enrollment criteria for the HIM Study included an age of 18–70 years; no prior diagnosis of an HPV-associated cancer or genital warts; and no current sexually transmitted disease diagnosis, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

A total of 1258 HIM Study male recruits with clinic visits from 2006 to 2010 were asked if they had a steady female partner and to invite her to join the couples’ study. A total of 560 men agreed to invite their partners, with 222 female partners responding affirmatively. Of these women, 165 (74%) met inclusion criteria for the study; however, 28 did not attend the first clinical visit. Women were excluded if they were <18 years of age or if they reported abnormal Papanicolaou test results in the prior 6 months, current sexually transmitted disease treatment, a history of genital warts, a hysterectomy, current pregnancy, or enrollment in an HPV vaccine trial; however, they were not excluded if they had HPV vaccination after enrollment. Thus, a total of 137 female sexual partners of HIM Study participants were enrolled.

After the enrollment visit, couples returned to the clinic for a total of 4 semiannual follow-up visits during a 2-year period. Although couples were encouraged to attend each clinic visit with no more than 14 days between each other's visit, not all couples observed the 14-day limit.

Although partners in couples were required to be each other's current primary sexual partners, they were not required to be monogamous nor to acknowledge sex with their primary partner in the recent past. Couples were instructed not to have sex for 48 hours before each clinic visit to avoid detection of superficial HPV. Women were asked not to douche for 24 hours before an appointment. Participants received a nominal incentive for study involvement. Each partner independently consented to the study's protocol, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of South Florida.

Procedure

The clinical protocols were similar for both male and female partners and included a physical examination, collection of biological specimens, and collection of behavioral data with a computer-assisted self-interview which elicited information about participant demographics, substance use, and sexual behaviors. Women were also questioned about Papanicolaou screening and pregnancy histories.

At all study visits, blood and urine samples were collected, and a clinician examined the external genitalia of each participant. If present, warts and/or lesions were sampled with a saline-wetted cotton swab. For women, the cervix, vulva/labia (including perineum), and anal canal were sampled. Vulva/labia specimens were collected by swabbing from the clitoral prepuce to the posterior fourchette (including collection between the folds of the labia minora and majora). Then, with a separate swab, cells were collected from between the anal os and the anal canal dentate line. To sample the endo- and ectocervix, a swab moistened with normal saline was introduced into the cervical os, rotated once or twice, and then brushed back and forth across the ectocervix. Swabs from the cervix, vulva/labia, and anal canal were kept separate with each swab placed into standard transport media. The cervix was then swabbed to assess cytological status.

For men, the clinician used a saline-wetted swab to sweep 360° around the coronal sulcus and glans penis, and if present, a retracted prepuce. A second swab was used to sample the entire surface of the penile shaft, and a third to sample the scrotum. These 3 swabs were combined and placed into standard transport media. Specimens from both partners were stored at –80°C until polymerase chain reaction analyses and genotyping were conducted.

HPV Testing

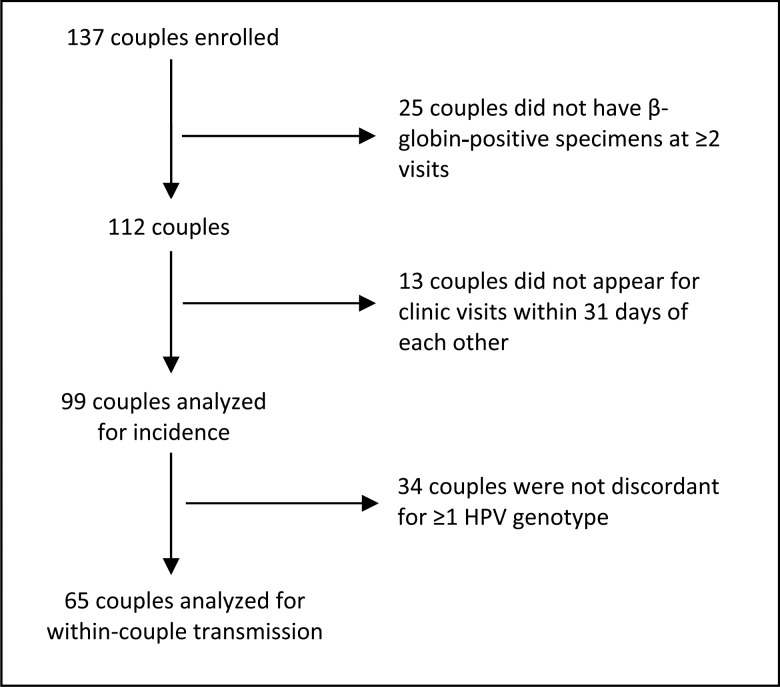

Specimens were analyzed for HPV DNA and β-globin, as described elsewhere [5]. DNA was extracted using the QIAamp Media MDx Kit (Qiagen). The polymerase chain reaction consensus primer system (PGMY 09/11) was used to amplify a fragment of the HPV L1 gene [13]. HPV genotyping was conducted on all specimens using DNA probes labeled with biotin to detect 36 HPV types: 6, 11, 16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 34, 35, 39, 40, 42, 44, 45, 51–54, 56, 58, 59, 61, 62, 66–73, 81–84, and 89 [14]. Accuracy and potential contamination were assessed using nontemplate negative controls and CaSki DNA–positive controls. Of 137 couples who provided biological specimens and behavioral data, 112 were β-globin or HPV genotype positive at ≥2 study visits in both partners (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of couples enrolled, attrition, and couples available for analysis. Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus.

Statistical Analyses

The current prospective analysis is based on couples' data collected at all study visits. For men, a genital specimen comprised exfoliated cells from the glans penis, prepuce (if present), penile shaft, and scrotum. For women, a genital specimen comprised exfoliated cells from the cervix and vulva/labia (the anal canal specimen was not included in analysis).

Analyses were conducted for specific HPV genotypes and groups of genotypes. A specimen was considered positive for the group “any HPV genotype” if it was positive for ≥1 of 36 genotypes. Specimens were “oncogenic” if ≥1 of 13 high-risk types were detected (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68 [15]), regardless of the presence of other genotypes. Similarly, specimens were “nononcogenic” if any of the remaining 23 types in the linear array were detected, regardless of the presence of oncogenic types.

Of 112 couples with valid specimens at multiple study visits, partners in 99 couples attended their clinical appointments within 31 days of each other and were included in incident analyses. These included couples who were either negative concordant (both partners free of HPV types at baseline), positive concordant (both partners had the same types at baseline), or discordant (the partners were discordant for ≥1 HPV type at baseline). Nine women reported receipt of an HPV vaccine during the study and were removed from analyses involving HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18.

Using Fisher exact tests, baseline characteristics of the 99 couples were compared with those in the balance of the 38 enrolled couples. Period prevalence was calculated for men, women, and each couple based on total time in the study. With the person used as the unit of analysis, incidence rates and cumulative incidence were calculated for each partner. Incident detection was defined as the detection of type-specific HPV at a follow-up visit when that type was absent at enrollment. Person-months for newly detected HPV infection were estimated by calculation of time from study entry to date of first detection of HPV. Otherwise, person-months were censored at the date of the last visit with negative results. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate 12-month cumulative incidence. The calculation of the exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for incidence estimates was based on the number of events modeled as a Poisson variable for the total person-months [16].

Of the 99 couples, 65 had HPV discordant partners at enrollment for analysis of genotype-specific HPV transmission incidence. A transmission incident event was defined as the first detection of an HPV genotype in a partner at a follow-up visit when that same genotype was present in the other partner at baseline. Because multiple infections are possible within an individual, the unit of analysis was the infection. As such, a total of 149 potentially transmissible infections were included in analysis. For groups of genotypes, a clustered Kaplan-Meier method [17] was used because of multiple transmission events within a couple. The effect of monogamy and relationship duration on sex-specific HPV transmission rates was assessed by stratifying (1) monogamous versus nonmonogamous couples and (2) couples whose relationship duration was ≤2 versus >2 years. A monogamous couple had partners who reported no out-of-relationship penetrative sex from 6 months before the study enrollment through the end of the study. The remaining couples were labeled nonmonogamous. The role of sex, monogamy, and relationship duration on HPV transmission incidence was evaluated using a Cox model with a robust covariance matrix estimator [18]. Data were analyzed using SAS 9.2 and 9.3 (SAS Institute) and R software.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics of men and women included in the incident analysis (n = 99) are compared in Table 1 with men and women who were not included (n = 38) because of study dropout or specimen inadequacy. Those included in the current analysis were younger (P = .05 and P =.04 for men and women, respectively) with a mean age of 33 years for those analyzed and 37 years for those not analyzed. There were no statistically significant differences in other variables (e.g., race, marital status, and sexual behavior) between the 2 groups.

Table 1.

Selected Baseline Characteristics of Men and Women Analyzed or Not Analyzed

| Variable | No. (%)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men |

Women |

|||

| Analyzed (n = 99) | Not Analyzed (n = 38) | Analyzed (n = 99) | Not Analyzed (n = 38) | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 18–30 | 57 (58) | 14 (37) | 56 (57) | 13 (34) |

| 31–44 | 20 (20) | 15 (39) | 19 (19) | 14 (37) |

| 45–70 | 22 (22) | 9 (24) | 24 (24) | 11 (29) |

| Mean (range) | 33 (18–70) | 37 (19–64) | 33 (18–70) | 37 (19–64) |

| P valueb | .05 | .04 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White | 69 (70) | 27 (71) | 67 (68) | 26 (68) |

| Black | 20 (20) | 5 (13) | 13 (13) | 3 (8) |

| Mixed/other | 9 (9) | 6 (16) | 18 (18) | 9 (24) |

| Refuse | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| P value | .41 | .61 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 20 (20) | 7 (18) | 17 (17) | 5 (13) |

| Non-Hispanic | 72 (73) | 30 (79) | 80 (81) | 33 (87) |

| Refuse | 7 (7) | 1 (3) | 2 (2) | 0 |

| P value | .81 | .61 | ||

| Educational level, y | ||||

| <12 | 2 (2) | 2 (5) | 2 (2) | 3 (8) |

| 12 | 19 (19) | 11 (29) | 11 (11) | 6 (16) |

| 13–16 | 74 (75) | 23 (61) | 81 (82) | 27 (71) |

| ≥17 | 4 (4) | 2 (5) | 5 (5) | 2 (5) |

| P value | .29 | .29 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single, never married | 50 (51) | 11 (29) | 39 (39) | 8 (21) |

| Married | 31 (31) | 18 (47) | 30 (30) | 18 (47) |

| Cohabitating | 9 (9) | 3 (8) | 20 (20) | 6 (16) |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 9 (9) | 6 (16) | 10 (10) | 6 (16) |

| P value | .10 | .10 | ||

| HPV vaccination for female partner | ||||

| Yes | NA | NA | 4 (4) | 1 (3) |

| No | NA | NA | 86 (87) | 37 (97) |

| Refuse | NA | NA | 9 (9) | 0 |

| P value | … | >.99 | ||

| Prepuce present for male partner (clinician record) | ||||

| Yes | 17 (17) | 4 (11) | NA | NA |

| No | 82 (83) | 34 (89) | NA | NA |

| P value | .43 | … | ||

| Lifetime opposite-sex sex partners, No. | ||||

| 1–2 | 14 (14) | 7 (18) | 20 (20) | 8 (21) |

| 3–9 | 30 (30) | 8 (21) | 40 (40) | 16 (42) |

| ≥10 | 44 (44) | 21 (55) | 33 (33) | 12 (32) |

| Refuse | 11 (11) | 2 (5) | 6 (6) | 2 (5) |

| Median (range) | 9 (1–200) | 10 (1–200) | 5 (1–40) | 6 (1–35) |

| P value | .43 | >.99 | ||

| Opposite-sex sex partners in past 6 mo, No. | ||||

| 0 | 6 (6) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 69 (70) | 28 (74) | 78 (79) | 32 (84) |

| ≥2 | 17 (17) | 7 (18) | 17 (17) | 5 (13) |

| Refuse | 7 (7) | 2 (5) | 4 (4) | 1 (3) |

| Median (range) | 1 (0–20) | 1 (0–20) | 1 (1–8) | 1 (1–6) |

| P value | .87 | .61 | ||

| Frequency of condom use for vaginal sex with primary partner in past 6 mo | ||||

| Always | 5 (5) | 3 (8) | 12 (12) | 3 (8) |

| Sometimes | 31 (31) | 6 (16) | 36 (36) | 9 (24) |

| Never | 41 (41) | 23 (61) | 46 (46) | 24 (63) |

| No recent vaginal sex | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Refuse | 20 (20) | 6 (16) | 5 (5) | 2 (5) |

| P value | .12 | .23 | ||

Abbreviations: HPV, human papillomavirus; NA, not applicable.

a Values represent No. (%) unless otherwise specified.

b P values are derived from Fisher exact tests and do not include “refuse” observations.

The median lifetime number of opposite-sex sex partners was 9 among men (range, 1–200) and 5 among women (range, 1–40). A total of 100%, 94%, 93%, and 85% of couples reported sexual behavior in the 4 intervals between visits 1 and 5. The median time in the study for couples was 25 months.

During the 2 years, we detected any HPV type, oncogenic types, and nononcogenic types in 83%, 65% and 74% of couples, respectively (Table 2). Period prevalence was comparable between men and women for both oncogenic genotypes (48% for men and 47% for women) and nononcogenic types (59% for men and 61% for women). We detected HPV-16 in 14%, 14%, and 22% of men, women, and couples, respectively, during the study.

Table 2.

The 24-month Period Prevalence of HPV Genital Infection Among Partners in 99 Heterosexual Couples (2006–2011)

| HPV Typea | Prevalence, No. (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Couplesb | |

| Any HPV genotypec | 73 (74) | 67 (68) | 82 (84) |

| Oncogenic | 47 (50)d | 46 (49)d | 64 (65)c |

| 16e | 13 (14) | 13 (14) | 20 (22) |

| 18e | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 5 (6) |

| 31 | 6 (6) | 8 (8) | 11 (11) |

| 33 | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) |

| 35 | 2 (2) | 5 (5) | 6 (6) |

| 39 | 10 (10) | 5 (5) | 12 (12) |

| 45 | 3 (3) | 6 (6) | 8 (8) |

| 51 | 16 (16) | 8 (8) | 20 (20) |

| 52 | 10 (10) | 8 (8) | 14 (14) |

| 56 | 5 (5) | 6 (6) | 9 (9) |

| 58 | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 6 (6) |

| 59 | 10 (10) | 7 (7) | 14 (14) |

| 68 | 9 (9) | 4 (4) | 11 (11) |

| Nononcogenic | 58 (60)f | 60 (63)f | 73 (74)c |

| 6e | 13 (14) | 8 (9) | 17 (19) |

| 11e | 3 (3) | 0 | 3 (3) |

| 40 | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 4 (4) |

| 42 | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) |

| 44 | 5 (5) | 9 (9) | 11 (11) |

| 53 | 12 (12) | 7 (7) | 16 (16) |

| 54 | 10 (10) | 11 (11) | 16 (16) |

| 61 | 5 (5) | 7 (7) | 11 (11) |

| 62 | 16 (16) | 20 (20) | 26 (26) |

| 66 | 12 (12) | 12 (12) | 18 (18) |

| 67 | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 5 (5) |

| 70 | 5 (5) | 4 (4) | 8 (8) |

| 71 | 0 | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| 72 | 5 (5) | 5 (5) | 8 (8) |

| 73 | 4 (4) | 5 (5) | 9 (8) |

| 81 | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 7 (7) |

| 82 | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 6 (6) |

| 83 | 8 (8) | 8 (8) | 13 (13) |

| 84 | 15 (15) | 9 (9) | 22 (22) |

| 89 | 17 (17) | 14 (14) | 23 (23) |

Abbreviation: HPV, human papillomavirus.

a HPV genotypes 26, 34, and 69 were not detected in any couples at any visit.

b Period prevalence of HPV in either or both partners.

c Denominator is 98 due to woman's receipt of quadrivalent HPV vaccination.

d Denominator is 94 due to women's receipt of quadrivalent HPV vaccination.

e Denominator is 90 due to women's receipt of quadrivalent HPV vaccination.

f Denominator is 96 due to women's receipt of quadrivalent HPV vaccination.

Likewise, both the incidence rate and 12-month cumulative incidence were comparable between the sexes when HPV-negative concordant, HPV-positive concordant, and discordant couples were analyzed together using the person as the unit of analysis (Table 3). Oncogenic type incidence rates were highest for HPV types 16, 52, 51 and 39 among men and HPV types 51 and 16 among women. Nononcogenic type incidence was highest for HPV types 89, 62, 84, 54, and 6 among men and HPV types 62, 89, 6, 44, and 84 among women. The 12-month cumulative incidence for any HPV genotype was the same for both sexes (28%; 95% CI, 14%–40%).

Table 3.

Genital Incidence of Type-Specific HPV Among Partners in 99 Heterosexual Couples (2006–2011)

| HPV Typea | Men |

Women |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. at Risk | No. of Infections | Person-months | Incidence Rate (95% CI)b | 12-mo Cumulative Incidence (95% CI) | No. at Risk | No. of Infections | Person-months | Incidence Rate (95% CI)b | 12-mo Cumulative Incidence (95% CI) | |

| Any HPV type | 48 | 21 | 877 | 23.9 (14.8–36.6) | 0.28 (.14–.40) | 53 | 22 | 963 | 22.9 (13.7–39.7) | 0.28 (.14–.40) |

| Oncogenic | 68 | 17 | 1419 | 12.0 (7.0–19.2) | 0.16 (.07–.25) | 73 | 20 | 1439 | 12.0 (8.5–21.5) | 0.17 (.08–.26) |

| 16 | 83 | 7 | 1849 | 3.8 (1.5–7.8) | 0.02 (.0–.05) | 81 | 5 | 1771 | 2.8 (.9–6.6) | 0.05 (.0–.10) |

| 18 | 88 | 2 | 2030 | 1.0 (.1–3.6) | 0.0 (.0–.0) | 89 | 3 | 1931 | 1.6 (.3–4.5) | 0.02 (.0–.06) |

| 31 | 96 | 3 | 2158 | 1.4 (.3–4.1) | 0.02 (.0–.05) | 95 | 4 | 2083 | 1.9 (.5–4.9) | 0.03 (.0–.06) |

| 33 | 99 | 1 | 2272 | 0.4 (.0–2.5) | 0.0 (.0–.0) | 98 | 1 | 2195 | 0.5 (.0–2.5) | 0.01 (.0–.03) |

| 35 | 98 | 1 | 2236 | 0.4 (.0–2.5) | 0.01 (.0–.03) | 98 | 4 | 2166 | 1.8 (.5–4.7) | 0.02 (.0–.05) |

| 39 | 95 | 6 | 2100 | 2.9 (1.0–6.2) | 0.03 (.0–.07) | 97 | 3 | 2146 | 1.4 (.3–4.1) | 0.02 (.0–.06) |

| 45 | 96 | 0 | 2204 | 0.0 (.0–1.7) | 0.0 (.0–.0) | 97 | 4 | 2167 | 1.8 (.5–4.7) | 0.0 (.0–.0) |

| 51 | 90 | 7 | 1962 | 3.6 (1.4–7.4) | 0.07 (.01–.12) | 98 | 7 | 2154 | 3.2 (1.3–6.7) | 0.05 (.01–.10) |

| 52 | 97 | 8 | 2141 | 3.7 (1.6–7.4) | 0.04 (.0–.09) | 94 | 3 | 2097 | 1.4 (.3–4.2) | 0.01 (.0–.03) |

| 56 | 97 | 3 | 2195 | 1.4 (.3–4.0) | 0.01 (.0–.03) | 95 | 2 | 2141 | 0.9 (.1–3.4) | 0.0 (.0–.0) |

| 58 | 96 | 1 | 2192 | 0.5 (.0–2.5) | 0.0 (.0–.0) | 97 | 1 | 2196 | 0.5 (.0–2.5) | 0.01 (.0–.04) |

| 59 | 90 | 1 | 2093 | 0.5 (.0–2.7) | 0.01 (.0–.03) | 95 | 3 | 2147 | 1.4 (.3–4.1) | 0.01 (.0–.03) |

| 68 | 93 | 3 | 2117 | 1.4 (.3–4.1) | 0.01 (.0–.03) | 97 | 2 | 2169 | 0.9 (.1–3.3) | 0.01 (.0–.03) |

| Nononcogenic | 59 | 17 | 1187 | 14.3 (8.3–22.9) | 0.16 (.06–.25) | 59 | 20 | 1140 | 17.6 (10.6–27.1) | 0.16 (.06–.25) |

| 6 | 83 | 6 | 1892 | 3.2 (1.2–6.9) | 0.04 (.0–0.08) | 87 | 6 | 1889 | 3.2 (1.2–6.9) | 0.05 (.0–.10) |

| 11 | 89 | 3 | 2030 | 1.5 (.3–4.3) | 0.02 (.0–.05) | 89 | 0 | 2004 | 0.0 (.0–1.8) | 0.0 (.0–.0) |

| 40 | 99 | 2 | 2253 | 0.9 (.1–3.2) | 0.01 (.0–.03) | 97 | 0 | 2188 | 0.0 (.0–1.7) | 0.0 (.0–.0) |

| 42 | 99 | 2 | 2260 | 0.9 (.1–3.2) | 0.0 (.0–.0) | 98 | 2 | 2206 | 0.9 (.1–3.3) | 0.01 (.0–.03) |

| 44 | 97 | 3 | 2188 | 1.4 (.3–4.0) | 0.02 (.0–.05) | 96 | 6 | 2144 | 2.8 (1.0–6.1) | 0.02 (.0–.05) |

| 53 | 93 | 6 | 2070 | 2.9 (1.1–6.3) | 0.02 (.0–.05) | 97 | 5 | 2115 | 2.4 (.8–5.5) | 0.02 (.0–.05) |

| 54 | 96 | 7 | 2137 | 3.3 (1.3–6.7) | 0.04 (.0–.08) | 93 | 5 | 2068 | 2.4 (.8–5.6) | 0.01 (.0–.04) |

| 61 | 96 | 2 | 2204 | 0.9 (.1–3.3) | 0.0 (.0–.0) | 95 | 3 | 2118 | 1.4 (.3–4.1) | 0.02 (.0–.05) |

| 62 | 91 | 8 | 2026 | 3.9 (1.7–7.8) | 0.04 (.0–.07) | 87 | 8 | 1924 | 4.2 (1.8–8.2) | 0.05 (.0–.09) |

| 66 | 93 | 6 | 2075 | 2.9 (1.1–6.3) | 0.06 (.0–.10) | 91 | 4 | 1985 | 2.0 (.5–5.2) | 0.01 (.0–.03) |

| 67 | 98 | 1 | 2231 | 0.4 (.0–2.5) | 0.01 (.0–.03) | 97 | 1 | 2147 | 0.5 (.0–2.6) | 0.01 (.0–.03) |

| 70 | 97 | 3 | 2186 | 1.4 (.3–4.0) | 0.02 (.0–.05) | 97 | 2 | 2143 | 0.9 (.1–3.4) | 0.01 (.0–.04) |

| 72 | 98 | 4 | 2172 | 1.8 (.5–4.7) | 0.04 (.0–.08) | 96 | 2 | 2171 | 0.9 (.1–3.3) | 0.01 (.0–.03) |

| 73 | 97 | 2 | 2200 | 0.9 (.1–3.3) | 0.01 (.0–.03) | 96 | 2 | 2145 | 0.9 (.1–3.4) | 0.01 (.0–.03) |

| 81 | 96 | 1 | 2186 | 0.5 (.0–2.5) | 0.0 (.0–.0) | 98 | 3 | 2211 | 1.4 (.3–4.0) | 0.01 (.0–.04) |

| 82 | 96 | 2 | 2186 | 0.9 (.1–3.3) | 0.0 (.0–.0) | 97 | 1 | 2160 | 0.5 (.0–2.6) | 0.01 (.0–.03) |

| 83 | 96 | 5 | 2150 | 2.3 (.8–5.4) | 0.02 (.0–.05) | 96 | 5 | 2147 | 2.3 (.8–5.4) | 0.02 (.0–.05) |

| 84 | 91 | 7 | 2042 | 3.4 (1.4–7.1) | 0.02 (.0–.05) | 96 | 6 | 2134 | 2.8 (1.0–6.1) | 0.03 (.0–.07) |

| 89 | 92 | 10 | 2008 | 5.0 (2.4–9.2) | 0.07 (.01–.12) | 93 | 8 | 2025 | 4.0 (1.7–7.8) | 0.03 (.0–.07) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval. HPV, human papillomavirus.

a Incident HPV types 26, 34, 69, and 71 were not detected in any participant.

b Infections per 1000 person-months; the unit of analysis is the person.

There were no differences in demographics between the 65 discordant couples and the 34 couples who were not discordant except that discordant couples were more likely to be African American (P = .02 and P = .01 for men and women, respectively) and more likely to have ≥10 lifetime sexual partners (P = .002 and P < .001 for men and women, respectively; data not shown). The 65 couples had been together for a median of 3.5 years at the time of a transmission event or censoring.

In transmission analysis using the infection as the unit of analysis, detection of incident HPV was higher in men than in women for any HPV and oncogenic and nononcogenic genotypes, although 95% CIs overlapped (Table 4). For example, the incidence rate for any HPV genotype among men in discordant couples (i.e., men in whom we observed an incident infection for a genotype that was observed in their female partner at baseline) was 12.3/1000 person-months (95% CI, 7.1–19.6) compared with 7.3/1000 person-months (95% CI, 3.5–13.5) among women. The cumulative probability of transmission from a woman to a man during the study's first year was 0.18 (95% CI, .09–.28), and the probability of transmission from a man to a woman was 0.07 (95% CI, .01–.13). Most transmission events involved nononcogenic rather than oncogenic types, regardless of the direction of transmission (Table 4).

Table 4.

Genital Transmission Incidence of Type-Specific HPV Within 65 Discordant Heterosexual Couples (2006–2011)

| HPV Type | Incident Detections, No.a |

Incidence Rate (95% CI)b |

12-mo Cumulative Incidence (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Women to Men | Men to Women | Women to Men | Men to Women | |

| Any HPV type | 17 | 10 | 12.3 (7.1–19.6) | 7.3 (3.5–13.5) | .18 (.09–.28) | .07 (.01–.13) |

| Oncogenic | 4 | 3 | 9.4 (2.6–24.0) | 4.2 (.9–12.3) | .16 (.0–.31) | .06 (.0–.14) |

| Nononcogenic | 13 | 7 | 13.5 (7.2–23.2) | 7.6 (3.0–15.6) | .14 (.09–.30) | .07 (.0–.16) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HPV, human papillomavirus.

a The unit of analysis is the infection; there were 149 potential incident events among the 65 couples.

b Infections per 1000 person-months.

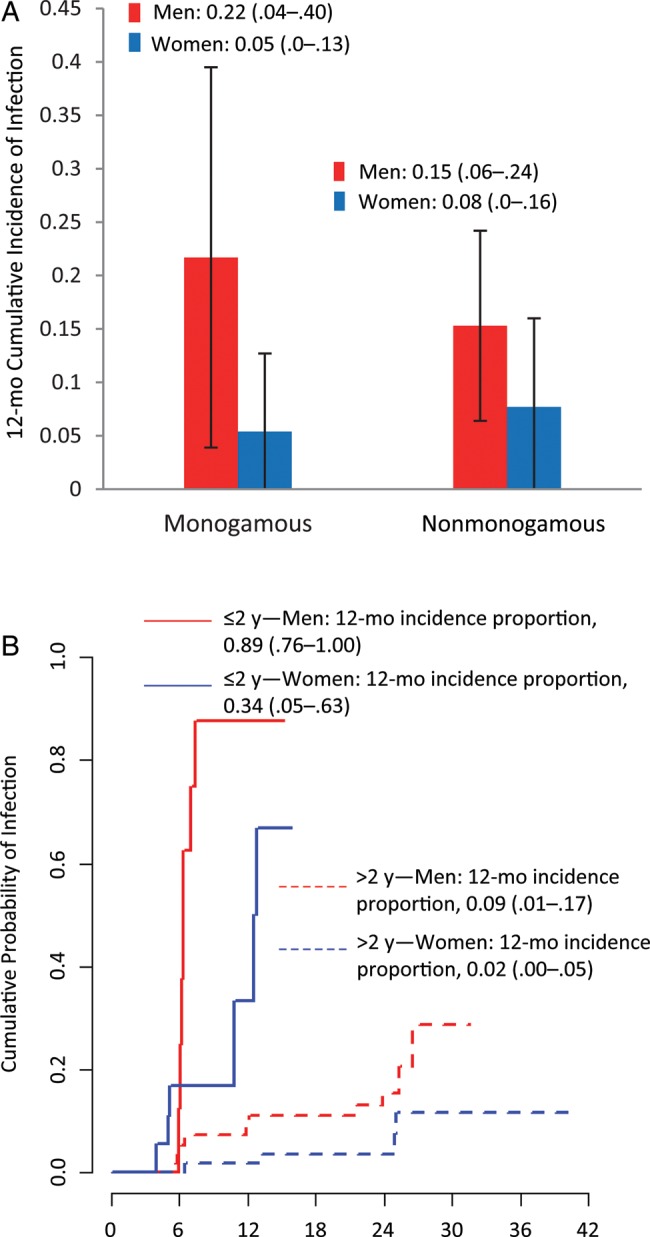

Increased incident HPV detection among men in discordant couples occurred in both monogamous and nonmonogamous couples, although CIs overlapped (Figure 2). In addition, compared with couples whose relationship duration was >2 years, newer couples in relationships of ≤2 years showed an increased probability of transmission events. For example, the 12-month cumulative incidence for partners in couples together for ≤2 years was 0.89 (95% CI, .76–1.00) and 0.34 (95% CI, .05–.63) for men and women, respectively; however, the 12-month cumulative incidence for men and women together for >2 years was 0.09 (95% CI, .01–.17) and 0.02 (95% CI, .00–.05) for men and women, respectively. Regardless of relationship duration, the male-to-female transmission incidence was lower than the female-to-male transmission incidence.

Figure 2.

Type-specific genital transmission incidence of any human papillomavirus (HPV) genotype within 65 discordant heterosexual couples stratified by monogamy and relationship duration (2006–2011). A, 12-month cumulative incidence of HPV infection by sex within monogamous and nonmonogamous couples. B, Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative probability of infection for couples with relationship duration ≤2 years (solid lines) or >2 years (dashed lines). Parenthetical ranges represent 95% confidence intervals.

DISCUSSION

We report on incident HPV transmission among asymptomatic heterosexual couples aged 18–70 years. Among the discordant couples, incidence estimates for groups of HPV were substantially higher among men than among women, although CIs overlapped. HPV transmission seems to occur more often from women to men than from men to women suggesting a need for prevention interventions, such as vaccination, directed at men.

One interpretation of higher incident infection among men in heterosexual couples is that female-to-male transmission is more common than male-to-female transmission. Another explanation is that men may have been infected with additional types during out-of-relationship sex; however, when we stratified couples into monogamous couples (those in which both partners reported no additional sex partners from 6 months before enrollment to the end of study participation) and nonmonogamous couples, men in each kind of coupling continued to show increased acquisition of HPV compared to their partners. We also stratified by duration of relationship to assess whether transmission rates were different in newer couples than in those that were more established. Although the transmission incidence was highest in couples of ≤2 years duration, we observed higher incident detection in men than in women in both newer and more established couples.

We are aware of 4 publications that have estimated incident HPV detection by sex within heterosexual couples [8–11]. Among 179 recently formed and discordant heterosexual couples, Burchell et al [8] observed similar transmission incidence from women to men (40/1000 person-months) and men to women (35/1000 person-months) after 1 follow-up visit a median of 5.5 months after baseline. That study also observed a higher transmission rate among monogamous couples, although the increased transmission compared with nonmonogamous couples was not statistically significant. Hernandez et al [9] followed up a smaller number of monogamous heterosexual couples in which at least 1 partner tested positive for HPV at baseline (n = 18). They reported that the rate of transmission from cervix/urine to penis was 3.6 times greater than the rate of transmission from penis to cervix/urine.

Widdice et al [11], reporting on 25 monogamous heterosexual couples followed up for 5 visits during 6 weeks, observed more female-to-male than male-to-female transmission events. Transmission rates were reported between each visit and were 26.9–187.5/100 person-months for female-to-male genital transmission and 14.5–100.0/100 persons-months for male-to-female transmission. A single genital transmission estimate including all 5 visits was not reported. A South African study [10] also found more female-to-male than male-to-female HPV transmission events (2.8/100 vs 1.2/100 person-months) among 162 HIV-negative and 324 HIV-positive and HIV-discordant heterosexual couples tested for HPV at 6-month intervals for up to 2 years. HIV status affected transmission rates in this study, and transmission rates were not reported for couples in which both partners were HIV negative; thus, it is difficult to disentangle the potential effect of HIV infection and make comparisons with findings of our current study, which included only couples reporting no HIV infection.

Thus, the largest study to date found similar rates of transmission within young and newly formed heterosexual couples, whereas 4 other studies (including the current study) in heterogeneous groups of heterosexual couples (e.g., monogamous, nonmonogamous, HIV positive, and HIV negative) found a higher female-to-male transmission rate. One explanation is that young men and women in newly formed couples are more likely to be immune naive to a variety of HPV genotypes; thus, there is comparable sharing and a high rate of incident infection. For older couples there may be some immune protection from virion antibodies induced by past exposures (and within a couple, more so for women) [19] which could result in less overall detection of incident infection among couples together longer (albeit more frequent detection among men than women, given comparatively less immune protection in the men).

For example, in the current study, the mean age of both men and women in the 65 couples analyzed for transmission was 33 years. In the study by Hernandez et al [9], which also found an increased rate of transmission from women to men, the mean ages of the men and women were 28 and 26 years, respectively. Men and women in the study by Widdice et al [11] were slightly younger, and those in the study by Burchell et al [8] were younger still (mean age, 23.9 years in men and 21.5 years in women), which may account for their higher rate of HPV transmission compared with the current study. Indeed, when we averaged the age of the men and women in each couple and then stratified the couples by age (≤28 or >28 years), the 12–month transmission cumulative incidence for any HPV type was higher among the younger couples (25% from women to men and 11% from men to women; P = .31) than among older couples (13% from women to men and 3% from men to women; P = .12), although this difference not statistically significant (data not shown).

Although we are aware of only 1 comparative study, another explanation is that women harbor a higher viral load of HPV than men and thus are more likely to transmit HPV regardless of age [20]. Finally, collecting exfoliated cells from the penis and scrotum may result in collection of more superficially deposited HPV compared with collection of cells from the cervix and vulva. Given that alpha HPV species are commonly found on fingers and hands [9, 11], more tactilely-accessible anatomic sites may have more superficial deposition.

Males and females in the larger cohort of 99 couples had similar incidence of HPV infection; however, these estimates are not readily comparable to those in the smaller discordant cohort because the estimates in the larger cohort are derived from any incident event and not just an incident event involving a specific genotype among a discordant couple. In addition, the unit of analysis was different for each cohort.

Limitations of this study include the sample size, which reduced our ability to observe more transmission events, especially of oncogenic types. In addition, the 6-month interval between visits probably misses some transmission events that would have been detected if visits were closer together [11]. Furthermore, sexually transmitted infection studies of discordant couples, in which transmission is not thought to have occurred, may be subject to spectrum or survivorship bias [21] because the study may artificially select couples that are less likely to transmit the infection; however, the relatively high transmission rate of HPV within discordant heterosexual couples may limit this type of bias. Although we removed 9 couples from analyses involving HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18 because the female partner reported HPV vaccination, we cannot rule out the possibility that a cross-protection effect of the vaccine affected estimates involving other genotypes. Moreover, because partners in a couple could have been tested as much as 31 days apart from each other, there is the potential for misclassification of discordant couples. Finally, a total of 9 couples at follow-up visits acknowledged sex within 48 hours before a clinic visit; however, when these couples were removed from analysis, point estimates did not markedly change (data not shown).

The current study found transmission of incident genital HPV to be more common from women to men than from men to women, and these findings indicate a need for prevention programs targeted at men. This pattern occurred without regard to monogamy or relationship duration (categorized as >2 or ≤2 years). Future studies should enroll couples with a broad range of relationship durations to help elucidate the effect that factors such as the host immune system may have on transmission within couples. In addition, given their high HPV disease burden, future transmission studies could include homosexual male couples.

Notes

Acknowledgments. Special thanks to the men and women who provided personal information and biological specimens for the study. Thanks to the HIM Study Team in Tampa, including Jane L. Messina, Kathy Eyring Cabrera, Kayoko Kennedy, Kimberly Isaacs, Andrea Bobanic, Bradley A. Sirak, Michael T. O'Keefe, Donna J. Ingles, Christine M. Pierce Campbell. Thanks also to Qiagen for donation of collection vials and Specimen Transport Medium.

Financial support. National Institutes of Health (grant RO1 CA098803 01–A1 to A. R. G.) and GlaxoSmithKline (grant EPI-HPV-036 BOD US CRT to A. R. G). The contribution of A. G. N. to this paper was also funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (grant R25 CA090314 to Paul B. Jacobsen, PhD, Principal Investigator). Publication and report contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health or GlaxoSmithKline.

Potential conflicts of interest. A. G. N. has previously received research support from Merck. C. M. G. is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline. A. R. G. receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline and Merck and is on the speaker's bureau for Merck. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Bosch FX, Burchell AN, Schiffman M, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of human papillomavirus infections and type-specific implications in cervical neoplasia. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 10):K1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nyitray AG, Lu B, Kreimer AR, Anic G, Stanberry LR, Giuliano AR. The epidemiology and control of human papillomavirus infection and clinical disease. In: Stanberry LR, Rosenthal SL, editors. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2nd ed. Hagerstown, MD: Wolters Kluwer–Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012. pp. 315–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chesson HW, Ekwueme DU, Saraiya M, Watson M, Lowy DR, Markowitz LE. Estimates of the annual direct medical costs of the prevention and treatment of disease associated with human papillomavirus in the United States. Vaccine. 2012;30:6016–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297:813–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giuliano AR, Lazcano-Ponce E, Villa LL, et al. The Human Papillomavirus Infection in Men Study: human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution among men residing in Brazil, Mexico, and the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2036–43. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giuliano AR, Lee JH, Fulp W, et al. Incidence and clearance of genital human papillomavirus infection in men (HIM): A cohort study. Lancet. 2011;377:932–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62342-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castle PE, Schiffman M, Herrero R, et al. A prospective study of age trends in cervical human papillomavirus acquisition and persistence in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1808–16. doi: 10.1086/428779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burchell AN, Coutlee F, Tellier PP, Hanley J, Franco EL. Genital transmission of human papillomavirus in recently formed heterosexual couples. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1723–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernandez BY, Wilkens LR, Zhu X, et al. Transmission of human papillomavirus in heterosexual couples. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:888–94. doi: 10.3201/eid1406.070616.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mbulawa ZZ, Johnson LF, Marais DJ, Coetzee D, Williamson AL. The impact of human immunodeficiency virus on human papillomavirus transmission in heterosexually active couples. J Infect. 2013;67:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Widdice L, Ma Y, Jonte J, et al. Concordance and transmission of human papillomavirus within heterosexual couples observed over short intervals. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1286–94. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nyitray AG, Menezes L, Lu B, et al. Genital human papillomavirus (HPV) concordance in heterosexual couples. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:202–11. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gravitt PE, Peyton CL, Alessi TQ, et al. Improved amplification of genital human papillomaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:357–61. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.357-361.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gravitt PE, Peyton CL, Apple RJ, Wheeler CM. Genotyping of 27 human papillomavirus types by using L1 consensus PCR products by a single-hybridization, reverse line blot detection method. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3020–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.10.3020-3027.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, et al. A review of human carcinogens-Part B: Biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:321–2. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulm K. A simple method to calculate the confidence interval of a standardized mortality ratio (SMR) Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131:373–5. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ying Z, Wei L. The Kaplan-Meier estimate for dependent failure time observations. J Multivar Anal. 1994;50:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin D, Wei L. The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84:1074–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markowitz LE, Sternberg M, Dunne EF, McQuillan G, Unger ER. Seroprevalence of human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, and 18 in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1059–67. doi: 10.1086/604729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bissett SL, Howell-Jones R, Swift C, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype detection and viral load in paired genital and urine samples from both females and males. J Med Virol. 2011;83:1744–51. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuite AR, Fisman DN. Spectrum bias and loss of statistical power in discordant couple studies of sexually transmitted infections. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:50–6. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181ec19f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]