Abstract

Aims

Medication non-adherence is a significant health problem. There are numerous methods for measuring adherence, but no single method performs well on all criteria. The purpose of this systematic review is to (i) identify self-report medication adherence scales that have been correlated with comparison measures of medication-taking behaviour, (ii) assess how these scales measure adherence and (iii) explore how these adherence scales have been validated.

Methods

Cinahl and PubMed databases were used to search articles written in English on the development or validation of medication adherence scales dating to August 2012. The search terms used were medication adherence, medication non-adherence, medication compliance and names of each scale. Data such as barriers identified and validation comparison measures were extracted and compared.

Results

Sixty articles were included in the review, which consisted of 43 adherence scales. Adherence scales include items that either elicit information regarding the patient's medication-taking behaviour and/or attempts to identify barriers to good medication-taking behaviour or beliefs associated with adherence. The validation strategies employed depended on whether the focus of the scale was to measure medication-taking behaviour or identify barriers or beliefs.

Conclusions

Supporting patients to be adherent requires information on their medication-taking behaviour, barriers to adherence and beliefs about medicines. Adherence scales have the potential to explore these aspects of adherence, but currently there has been a greater focus on measuring medication-taking behaviour. Selecting the ‘right’ adherence scale(s) requires consideration of what needs to be measured and how (and in whom) the scale has been validated.

Keywords: adherence scales, adherence tools, medication adherence, questionnaires, surveys

Introduction

There are many effective medicines available to treat illness, but the benefits of these medicines will only accrue to the patients that take them. The World Health Organization [1] defines adherence as:

The extent to which a person's behaviour – taking medication, following a diet and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider.

Medication non-adherence is common, with studies in a range of settings identifying up to 50% of patients as non-adherent to a medicine [2–6]. Poor medication adherence results in adverse health outcomes [7–9] and increased health care costs [7].

Patients may be non-adherent due to different beliefs, barriers and a range of other factors. Patients may intentionally decide not to take their medicines based on well-informed or mistaken beliefs about the benefits and risks of their medicines [10,11]. Patients can unintentionally non-adhere to medicines due to forgetfulness, carelessness, health literacy and socioeconomic factors. Non-adherence can also occur at different stages of the medication-taking process. A patient may exhibit non-adherence at the initiation of treatment, during treatment (where the patient may exhibit sub-optimal implementation of the treatment regimen) or the patient may discontinue the treatment early [12]. Strong evidence for any single approach to improve medication adherence is lacking, but interventions that are tailored to a patient's specific reasons and stage of non-adherence can be expected to better support good medication-taking behaviour [13–17].

Adherence to medicines is measured for different purposes. Common reasons to measure adherence include better informing the assessment of an intervention (as unrecognized non-adherence may lead to an underestimation of possible treatment effects), determining influences on adherence to medicines in people with specific disease states (such as hypertension or HIV) and identifying patients requiring education or support to improve medication use. Ideally, clinicians and researchers wanting a comprehensive assessment of adherence need measures that are inexpensive, relatively easy to administer, accurately identify the patient's current medication-taking behaviour and any barriers or beliefs that may influence the patient's use of medicines.

There are a number of ways of measuring adherence. Objective measures, including measurement of clinical outcomes, dose counts, pharmacy records, electronic monitoring of medication administration (e.g. the Medication Event Monitoring System, MEMS) and drug concentrations [18–21], seemingly provide the best measure of a patient's medication-taking behaviour in many contexts [22–27]. It is important to recognize that, while objective, most of these measures have drawbacks. MEMS, arguably the best objective measure of medication-taking behaviour, records package opening or device actuation, rather than actual medication-taking and the possibility of intentional dose dumping remains. MEMS, or MEMS-like devices, are also expensive and not readily available for some dose forms [21,28–30]. While clinical outcomes are the ultimate aim of any intervention to improve adherence, the use of clinical outcomes as a proxy of adherence can be confounded by disease-specific factors independent of medication-taking behaviour.

Subjective measures of adherence include physician or family reports, patient interviews and self-report adherence scales [10,31–34]. These measures have the potential to identify the specific reasons for a patient's non-adherence. Subjective measures can be relatively simple to use and are less expensive. However, they are prone to recall bias and the prospect that respondents provide answers that conform to their perceived expectations of their interviewer [35,36]. There are a large number of adherence scales that are suitable for use in research or clinical settings. A number of well-validated adherence scales have been strongly correlated with objective measures of adherence in several different populations of patients.

There is a need for scales that are easy to administer and correctly identify medication-taking behaviour, key barriers to adherence and beliefs associated with medication use that influence adherence. There have been few systematic attempts to describe the available self-report adherence scales and their benefits and limitations with respect to both medication-taking behaviour and the identification of barriers and beliefs associated with adherence [37,38]. The aim of this review is to (i) identify self-report medication adherence scales that have been correlated with a comparison measure of medication-taking behaviour, (ii) assess how these scales measure adherence and (iii) explore how these adherence scales have been validated.

Methods

A literature search for adherence scales was conducted using Cinahl and PubMed electronic databases. The initial search terms used to identify the articles were: medication adherence, medication non-adherence, medication compliance and medication non-compliance. This broad database search identified the names of the self-report adherence scales, which were then searched individually. This search was limited to English language studies published between 1981 and 2012. The date of the last search was on 1 August 2012. The reference lists of the relevant studies were searched to identify additional articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Adherence scales were included if they had been correlated against a comparison measure (objective or subjective) of medication-taking behaviour. To be included there needed to be a full text article, written in the English language on the development and/or validation of the adherence scale. Studies that used the self-report adherence scale without correlating the adherence scale against a comparison measure of medication-taking behaviour were excluded. The list of scales was reviewed for completeness with two adherence researchers.

Data extraction and analysis

The data extracted from the studies included the number of items in the adherence scale, study setting, criteria for identifying non-adherence, response rate and time to complete the adherence scale. Each validated self-report adherence scale was categorized according to whether it contained items that elicited information on (i) specific medication-taking behaviours: dose taken, dose frequency, dose administration and prescription refills, (ii) barriers to adherence: e.g. forgetfulness, treatment complexity and side effects and/or (iii) beliefs associated with adherence: e.g. perceived necessity of medicines and concerns about medicines. Adherence scales were also assessed on whether or not the scale identified the initiation, implementation or discontinuation of treatment as per the taxonomy proposed by Vrijens et al. [12].

To assess the quality of the correlation study, the following criteria were extracted: how the adherence scale was administered, sample size, the adherence comparison measures, internal consistency and, where reported, the sensitivity and specificity of the scale against a standard of adherence. Information on criterion, content and construct validity was also extracted to assess the validation of the adherence scale. The results of the studies were reviewed and compared.

Results

Search strategy

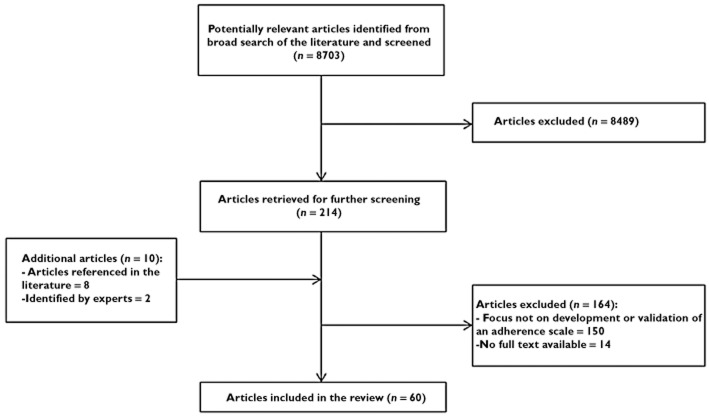

The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1. Twenty-one articles were retrieved using the Cinahl search engine and the remaining were identified using the same strategy in the PubMed database and from reference lists. Some adherence scales were excluded, as shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection process

Table 1.

Excluded self-report adherence scales

| Excluded adherence scale | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) Adherence Scale [90] | No validation studies were found in the literature search |

| Basel Assessment of Adherence Scale (BAAS) [91] | No validation studies were found in literature search. |

| Medication Adherence Evaluation Scale (MASS) [92] | No full-text article available |

| Medication Adherence Measure (MAM) interview [32] | Semi-structured interview and thus was not consistent between patients |

| Multicentre Aids Cohort Study (MACS) adherence form [93] | No adherence comparison measure |

The literature search retrieved 60 articles that met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The sample size of the studies ranged from 40 to 1367 (Table 2) [39,40]. The median sample size of the studies was 228. Twenty-two of the studies reported the response rate, ranging from 29 to 98%. The average response rate was 72% (Table 3). Forty-three self-report adherence scales were identified from the included studies.

Table 2.

Comparison of the self-report adherence scales

| Self-report adherence scale | Based on | Number of questions | Time to complete | Barriers identified | Stage of medication-taking identified | Number of development and correlation studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: Medication-taking behaviour | ||||||

| Adherence Self-Report Questionnaire (ASRQ) [41] | CQR | 1 | Not reported | -Nil | Implementation | 2 |

| Adherence Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) Computerized [52] | Literature review | 1 | Not reported | -Nil | Implementation | 1 |

| Brief Adherence Rating Scale (BARS) [33] | CATIE trial | 4 | Not reported | -Nil | Implementation | 1 |

| Barroso et al. 30-day Adherence Question [53] | Did not specify | 1 | Not reported | -Nil | Implementation | 1 |

| Bell et al. Adherence Question [42] | Did not specify | 1 | Not reported | -Nil | Implementation | 1 |

| Centre for Adherence Support Evaluation (CASE) Adherence Index [54] | Literature review | 3 | Not reported | -Nil | Implementation | 1 |

| Gehi et al. Adherence Question [9] | Expertise | 1 | Not reported | -Nil | Implementation | 1 |

| Grymonpre et al. Adherence Question [43] | Did not specify | 1 | Not reported | -Nil | Implementation | 1 |

| Kerr et al. Adherence Question [44] | Expertise | 1 | Not reported | -Nil | Implementation | 1 |

| Medication Adherence Report Scale – 5 (MARS-5) [71,85] | MARS-10 | 5 | Not reported | -Nil | Implementation Discontinuation | 3 |

| Stages of Change for Adherence (SOCA) [55] | Stages of Change model | 2 | Not reported | -Stages of change in regards to medication adherence | Initiation Implementation | 1 |

| Group 2: Medication-taking behaviour and barriers | ||||||

| Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS) [51] | Literature review, MAQ and Hill-Bone Compliance Scale | 12 | Not reported | -Correct administration | Implementation Discontinuation | 1 |

| -Forgetfulness | ||||||

| -Prescription refill ability | ||||||

| Adherence Starts with Knowledge-12 (ASK-12) [45] | ASK-20 | 12 | Not reported | -Patient-perceived barriers | Implementation Discontinuation | 1 |

| -Inconvenience | ||||||

| -Forgetfulness | ||||||

| -Medication beliefs | ||||||

| Adherence Starts with Knowledge-20 (ASK-20) [46] | Literature review, patient focus groups and expert panel input | 20 | Not reported | -Medication-taking behaviour | Implementation Discontinuation | 2 |

| -Patient-perceived barriers | ||||||

| Brief Medication Questionnaire [40] | Literature review and patient feedback | 9 | Not reported | -Evaluates regimen | Implementation | 1 |

| -Medication-taking problems | ||||||

| Brooks Medication Adherence Scale (BMAS) [56] | MAQ | 4 | Less than 5 min | -Forgetfulness | Implementation Discontinuation | 2 |

| -Carelessness | ||||||

| -Adverse effects and efficacy | ||||||

| Choo et al. 5-item Questionnaire [57] | Brief Medication Questionnaire | 5 | Not reported | -Unintentional and intentional non-adherence | Implementation | 1 |

| Fodor et al. Adherence Questionnaire [72] | Did not specify | 9 | Not reported | -Blood pressure awareness | Implementation Discontinuation | 1 |

| Godin et al. Self-Reported Adherence Questionnaire [47] | Expertize | 6 | 5 min | -Barriers to adherence | Implementation | 1 |

| Hill-Bone Compliance Scale – 10 [8] | The Hill-Bone Compliance Scale – 14 | 10 | Not reported | -Medication adherence | Implementation | 1 |

| -Appointment-making | ||||||

| -Sodium intake | ||||||

| Hill-Bone Compliance Scale – 14 [62] | Literature review and Clinical expertise | 14 | 5 min | -Medication adherence | Implementation | 1 |

| -Appointment-making | ||||||

| -Sodium intake | ||||||

| Immunosuppressant Therapy Adherence Scale (ITAS) [58] | MAQ | 4 | Less than 5 min | -Forgetfulness | Implementation Discontinuation | 1 |

| -Carelessness | ||||||

| -Adverse effects | ||||||

| Medication Adherence Assessment Tool (MAAT) [80] | Literature review and Expert clinicians | 12 | Not reported | -Previous history | Implementation | 1 |

| -Adverse effects | ||||||

| -Access to medications | ||||||

| Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) [34] | MAQ and behavioural aspects | 8 | Not reported | -Forgetfulness | Implementation Discontinuation | 3 |

| -Medication-taking behaviour | ||||||

| -Adverse effects and problems | ||||||

| Osteoporosis-Specific Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (OS-MMAS) [48] | MMAS | 8 | Not reported | -Forgetfulness | Implementation Discontinuation | 1 |

| -Medication-taking behaviour | ||||||

| -Adverse effects and problems | ||||||

| Pediatric Inhaler Adherence Questionnaire (PIAQ) [49] | Literature review, expertise and focus groups, | 6 | 1–3 min | -Missed and additional doses | Implementation | 1 |

| -Barriers to adherence | ||||||

| Reported Adherence to Medicine (RAM) Scale [10] | Literature review | 4 | Not reported | -Forgetfulness | Implementation | 2 |

| -Dose adjustments | ||||||

| Self-Reported Adherence (SERAD) Questionnaire [59] | SERAD study | 13 | Not reported | -Dose frequency adherence | Implementation | 1 |

| -Barriers to adherence | ||||||

| Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire (SMAQ) [39] | MAQ | 6 | Not reported | -Forgetfulness | Implementation Discontinuation | 1 |

| -Adverse effects | ||||||

| The Patterns of Asthma Medication Use Questionnaire [60] | Literature review, Expertise | 5 | Not reported | -Forgetfulness | Implementation | 1 |

| -Medication-taking strategy | ||||||

| Group 3: Barriers to adherence | ||||||

| Adherence Attitude Inventory (AAI) [63] | Health Belief Model, Health Promotion Model, Reasoned Action | 28 | Not reported | -Cognitive functioning | Implementation | 1 |

| -Patient-Provider | ||||||

| -Self-efficacy | ||||||

| -Commitment | ||||||

| Medication Adherence Questionnaire (MAQ) [73] | 5-item questionnaire by Green et al. | 4 | Not reported | -Forgetfulness and carelessness | Implementation Discontinuation | 8 |

| -Adverse effects and efficacy | ||||||

| Medication Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale (MASES) [64] | Patient interviews | 26 | Not reported | -Medication self-efficacy | Implementation | 1 |

| -Access to medications | ||||||

| -Adverse effects | ||||||

| -Lifestyle barriers | ||||||

| Medication Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale Revised (MASES-R) [79] | MASES | 13 | Not reported | -Medication self-efficacy | Implementation | 1 |

| -Lifestyle barriers | ||||||

| -Adverse effects | ||||||

| Medication Adherence Reasons Scale [66] | Literature review | 15 | Not reported | -Managing issues | Implementation Discontinuation | 1 |

| -Beliefs | ||||||

| -Multiple medication issues | ||||||

| -Availability issues | ||||||

| -Forgetfulness | ||||||

| The Self-Efficacy for Appropriate Medication Use Scale (SEAMS) [65] | Literature, expertise and patient interviews | 13 | Not reported | -Specific problem areas | Nil | 1 |

| -Self-efficacy | ||||||

| Group 4: Beliefs associated with adherence | ||||||

| Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire [10] | Health Belief Model and Patient Beliefs | 18 | Not reported | -Medication necessity beliefs | Nil | 4 |

| -Medication concerns | ||||||

| Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI) [4] | Literature review and patient reports | 30 | Not reported | -Attitudes towards medications | Discontinuation | 1 |

| -Beliefs on medications | ||||||

| Group 5: Barriers and beliefs | ||||||

| Beliefs and Behaviour Questionnaire (BBQ) [67] | Qualitative interviews with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) patients | 30 | Not reported | -Beliefs | Nil | 1 |

| -Experiences | ||||||

| Brief Evaluation of Medication Influences and Beliefs (BEMIB) [68] | Health Belief Model and Patient/Investigator feedback | 8 | Less than 5 min | -Forgetfulness | Implementation | 1 |

| -Access to medications | ||||||

| -Support network | ||||||

| -Benefits of medication | ||||||

| Compliance Questionnaire Rheumatology (CQR) [75] | Patient interviews | 19 | Approximately 12 min | -Forgetfulness | Implementation | 2 |

| -Value of doctor instructions | ||||||

| Maastricht Utrecht Adherence in Hypertension (MUAH) Questionnaire [69] | Patient interviews | 25 | Average 25 min | -Medication attitude | Implementation | 1 |

| -Discipline and aversions | ||||||

| -Coping with health problems | ||||||

| Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS) [70] | MAQ and DAI | 10 | Not reported | -Forgetfulness | Implementation Discontinuation | 2 |

| -Adverse effects | ||||||

| -Value of medication | ||||||

| -Behaviour and attitudes |

Table 3.

Self-report adherence scales – administration, response and validation data

| Self-report adherence scale | Reference number | How scale was administered | Response rate | Internal consistency | Sensitivity | Specificity | Correlation (criterion validity) | Comparison measure of adherence | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: Medication-taking behaviour | |||||||||

| Adherence Self-Report Questionnaire (ASRQ) | [41] | Clinician-administered (Other HCP) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Electronic monitoring (MEMS) | 245 |

| [94] | Clinician-administered (Primary physician) | 53% | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not significant (all) | Electronic monitoring (MEMS) and Other scale (VAS) | 78 | |

| Adherence Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) Computerized | [52] | Self-administered (Home, Internet) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (all) | Dose counts and Clinical outcome (Viral load) | 290 |

| Brief Adherence Rating Scale (BARS) | [33] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | Not reported | α = 0.92 | 0.73 | 0.74 | Significant | Electronic monitoring (MEMS) | 61 |

| Barroso et al. 30-day Adherence Question | [53] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Clinical outcome (Viral load) | 93 |

| Bell et al. Adherence Question | [42] | Self-administered (Clinic, Absent) | 80% | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not significant (all) | Electronic monitoring (MEMS) and Dose count | 80 |

| Centre for Adherence Support Evaluation (CASE) Adherence Index | [54] | Clinician-administered (Primary physician) | Not reported | Not reported | 0.70 | 0.71 | Significant (all) | Clinical outcome (Viral load) and Self-report | 524 |

| Gehi et al. Adherence Question | [9] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Clinical outcome (Cardiovascular events) | 1015 |

| Grymonpre et al. Adherence Question | [43] | Researcher-administered (Home) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (all) | Pharmacy records and Dose counts | 135 |

| Kerr et al. Adherence Question | [44] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not significant | Pharmacy records | 88 |

| Medication Adherence Report Scale – 5 (MARS-5) [85] | [5] | Clinician-administered (Primary physician) | Not reported | Not reported | 0.085 | 0.97 | Not significant | Pharmacy records | 128 |

| [71] | Self-administered (Clinic, Present) | Not reported | α = 0.78 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (all) | Drug levels and Self-report | 255 | |

| Stages of Change for Adherence (SOCA) | [55] | Self-administered (Clinic, Absent) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (all) | Electronic monitoring (MEMS) and Other scale (BMAS) | 731 |

| Group 2: Medication-taking behaviour and barriers | |||||||||

| Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS) | [51] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | 89% | α = 0.81 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (all) | Clinical outcome (BP control), Pharmacy records and Other scale (MAQ) | 435 |

| Adherence Starts with Knowledge-12 (ASK-12) | [45] | Self-administered (Clinic, Absent) | Not reported | α = 0.75 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (all) | Pharmacy record and Other scale (MAQ) | 112 |

| Adherence Starts with Knowledge-20 (ASK-20) | [46] | Self-administered (Home, Internet) | Not reported | α = 0.85 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Self-report | 605 |

| [95] | Self-administered (Clinic, Present) | Not reported | α = 0.76 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (Scale only) | Pharmacy records and Other scale (MAQ) | 112 | |

| Brief Medication Questionnaire | [40] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | 92% | Not reported | 0.80 | 1.00 | Significant | Electronic monitoring (MEMS) | 43 |

| Brooks Medication Adherence Scale (BMAS) | [56] | Self-administered (Unclear) | 86% | α = 0.69 | Not reported | Not reported | – | Nil | 294 |

| [96] | Self-administered (Home) | 63% | α = 0.86 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (all) | Pharmacy records and Self-report | 98 | |

| Choo et al. 5-item Questionnaire | [57] | Researcher-administered (Telephone) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Electronic monitoring (MEMS) | 286 |

| Fodor et al. Adherence Questionnaire | [72] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Clinical outcome (BP control) | 359 |

| Godin et al. Self-Reported Adherence Questionnaire | [47] | Self-administered (Clinic, Absent) | Not reported | Not reported | 0.71 | 0.72 | Not significant | Clinical outcome (Viral suppression) | 256 |

| Hill-Bone Compliance Scale – 10 | [8] | Researcher-and self-administered (Clinic) | Not reported | α = 0.79 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Clinical outcome (BP control) | 98 |

| Hill-Bone Compliance Scale – 14 | [62] | Researcher-and self-administered (Clinic) | Not reported | α = 0.84 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Clinical outcome (BP control) | 718 |

| Immunosuppressant Therapy Adherence Scale (ITAS) | [58] | Self-administered (Home) | 91% | α = 0.81 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (all) | Pharmacy records, Drug levels and Clinical outcome (Rejection) | 222 |

| Medication Adherence Assessment Tool (MAAT) | [80] | Self-administered (Clinic) | 29% | α = 0.80 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Pharmacy records | 289 |

| Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) | [34] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | 98% | α = 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.53 | Significant | Clinical outcome (BP control) | 1367 |

| [20] | Self-administered (Unclear) | 66% | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Pharmacy records | 87 | |

| [97] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | 82% | α = 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.36 | Significant | Pharmacy records | 151 | |

| Osteoporosis-Specific Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (OS-MMAS) | [48] | Self-administered (Home) | 39% | α = 0.82 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Other scale (Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire) | 197 |

| Pediatric Inhaler Adherence Questionnaire (PIAQ) | [49] | Self-administered (Clinic, Absent) | Not reported | Not reported | 0.63 | 0.91 | Significant | Dose counts | 64 |

| Reported Adherence to Medicine (RAM) Scale | [10] | Self-administered (Clinic, Absent) | Not reported | α = 0.72 | Not reported | Not reported | – | Nil | 524 |

| [50] | Self-administered (Home) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Other scale (Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire) | 271 | |

| Self-Reported Adherence (SERAD) Questionnaire | [59] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (all) | Electronic monitoring (MEMS), Dose counts and Drug levels | 530 |

| Simplified Medication Adherence Questionnaire (SMAQ) | [39] | Clinician-administered (Primary physician) | Not reported | α = 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.91 | Significant (all) | Electronic monitoring (MEMS) and Clinical outcome (Viral load) | 40 |

| The Patterns of Asthma Medication Use Questionnaire | [60] | Self-administered (Home) | 70% | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (all) | Pharmacy records and Clinical outcome (Asthma) | 176 |

| Group 3: Barriers to adherence | |||||||||

| Adherence Attitude Inventory (AAI) | [63] | Self-administered (Clinic, Absent) | Not reported | α = 0.90 | Not reported | Not reported | Not significant | Self-report | 165 |

| Medication Adherence Questionnaire (MAQ) | [73] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | 73% | α = 0.61 | 0.81 | 0.44 | Significant | Clinical outcome (BP control) | 290 |

| [76] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | Not reported | α = 0.32 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Pharmacy records | 377 | |

| [5] | Clinician-administered (Primary physician) | Not reported | Not reported | 0.32 | 0.73 | Not significant | Pharmacy records | 128 | |

| [77] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (all) | Electronic monitoring (MEMS), Dose counts and Drug levels | 385 | |

| [98] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | 32% | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Clinical outcome (Diabetes control) | 186 | |

| [99] | Researcher-administered (Home) | 88% | α = 0.42 | Not reported | Not reported | Not significant | Dose counts | 319 | |

| [78] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Dose counts | 413 | |

| [100] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | 81% | α = 0.62 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Clinical outcome (Diabetes control) | 294 | |

| Medication Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale (MASES) | [64] | Self-administered (Unclear) | Not reported | α = 0.95 | Not reported | Not reported | Not significant | Clinical outcome (BP control) | 72 |

| Medication Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale Revised (MASES-R) | [79] | Self-administered (Clinic, Present) | Not reported | α = 0.91 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (all) | Electronic monitoring (MEMS) and Other scale (MAQ) | 168 |

| Medication Adherence Reasons Scale | [66] | Self-administered (Home, Internet) | Not reported | α = 0.65 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Other scale (MAQ) | 840 |

| Self-Efficacy for Appropriate Medication Use Scale (SEAMS) | [65] | Self-administered (Clinic) | Not reported | α = 0.89 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Other scale (MAQ) | 436 |

| Group 4: Beliefs associated with adherence | |||||||||

| Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire | [10] | Self-administered (Clinic, Absent) | Not reported | α = 0.70 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Other scale (RAM) | 524 |

| [2] | Self-administered (Clinic, Absent) | 57% | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Other scale (MARS-5) | 324 | |

| [101] | Self-administered (Clinic) | Not reported | α = 0.73 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Other scale (MAQ) | 192 | |

| [102] | Self-administered (Clinic, Present) | 93% | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Other scale (MMAS) | 275 | |

| Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI) | [4] | Self-administered (Home) | Not reported | α = 0.93 | 0.72 | 0.63 | Significant | Therapist report | 150 |

| Group 5: Barriers and beliefs | |||||||||

| Beliefs and Behaviour Questionnaire (BBQ) | [67] | Self-administered (Home, Post) | 53% | α = 0.65 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Other scale (MARS) | 276 |

| Brief Evaluation of Medication Influences and Beliefs (BEMIB) | [68] | Self-administered (Clinic, Absent) | Not reported | α = 0.63 | 0.83 | 0.71 | Not significant (all) | Pharmacy records and Other scale (DAI) | 63 |

| Compliance Questionnaire Rheumatology (CQR) | [61] | Researcher-administered (Home) | Not reported | α = 0.71 | 0.98 | 0.67 | Significant | Self-report | 127 |

| [75] | Self-administered (Home) | 82% | Not reported | 0.62 | 0.95 | Significant | Electronic monitoring (MEMS) | 127 | |

| Maastricht Utrecht Adherence in Hypertension (MUAH) Questionnaire | [69] | Researcher-administered (Clinic) | 90% | α = 0.74 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (all) | Electronic monitoring (MEMS), Pharmacy records and Other scale (Brief Medication Questionnaire) | 255 |

| Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS) | [70] | Self-administered (Clinic, Absent) | Not reported | α = 0.75 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant (Drug levels only) | Drug levels or Caregiver report | 66 |

| [103] | Self-administered (Clinic, Absent) | Not reported | α = 0.62 | Not reported | Not reported | Significant | Caregiver report | 277 | |

Home– patients completed adherence scale at home; Clinic– patients completed adherence scale in clinic, researcher or clinician may be present or absent while patient fills out form; Telephone – patients completed adherence scale over the telephone; Primary physician = Patient's usual physician; Other HCP = Other health care professionals looking after patient; α = Cronbach's alpha of reliability; BP = Blood pressure.

Content of the scales

The adherence scales can be categorized into five groups based on the information they seek to elicit (the number of scales is given in parentheses, full details in Table 2). Group 1 scales seek information only on medication-taking behaviour (11), group 2 scales seek information on medication-taking behaviour and barriers to adherence (19), group 3 scales seek information only on barriers to adherence (6), group 4 scales seek information only on beliefs associated with adherence (2) and group 5 scales seek information on barriers and beliefs associated with adherence (5).

Thirty of the 43 scales contained items that asked specific questions about medication-taking behaviour (groups 1 and 2). Most of these adherence scales measure the number of doses taken [9,33,41–50] and contain items such as ‘how many days over the past month did you take less than prescribed?’ [33] and ‘did you miss a tablet yesterday?’ [42]. Other adherence scales measuring medication-taking behaviour do so through exploring the frequency of patients not refilling their prescription on time [40,45,46,51].

Twenty adherence scales measuring medication-taking behaviour specified a timeframe for the questions. The timeframe specified ranged from 1 day to 12 months [9,33,40,41,47,52–58] [34,39,42,44,48,49,59,60].

Thirty scales contained items that elicited information on barriers to, and determinants of adherence (groups 2, 3 and 5). Some of these adherence scales are disease-specific and thus explore common barriers that may influence adherence in these disease populations [48,49,56,60,61]. For example, the Pediatric Inhaler Adherence Questionnaire (PIAQ) explores adherence in patients with asthma and assesses the patient's difficulty in using asthma inhalers and the cost of inhalers [49]. Most of these adherence scales explore forgetfulness as a barrier to adherence and identify some of the situations where forgetfulness may be more common, such as when working or travelling [8,62–65]. Some adherence scales also explore physical barriers to adherence, such as vision problems, dexterity issues and dysphagia [40,49,66].

Seven scales elicited information on the patient's beliefs about their medicines that may relate to adherence (groups 4 and 5). These scales included items identifying beliefs that medicines are necessary, harmful and unnatural [4,10,61,67–70]. For example, the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire explores whether the patient holds beliefs that their medicines are necessary as well as whether they have any concerns about their medicines [10].

Forty of the 43 scales contained items that sought to identify aspects of adherence that are consistent with the taxonomy provided by Vrijens et al. [12]. Most scales contain items that seek to assess the extent of implementation of a dosing regimen (39/43) (Table 2). Thirteen of the scales also contain items that seek to identify the discontinuation of treatment [34,39,45,46,48,51,56,58,66,71–74]. The DAI contained items that sought information on discontinuation (alone) [4] and the SOCA scale identified the initiation of treatment [55]. Three adherence scales do not contain any items that seek to identify the initiation, implementation or discontinuation of treatment [10,65,67].

Administration of the scales

The adherence scales have been administered in different ways. Indeed, for the scales with more than one validation or correlation study, the additional studies often administered the scale in a slightly different way. Details of who completed the scale (i.e. patient, clinician or researcher) and where the scale was administered are provided in Table 3. There was a roughly even split between studies that requested the patient to complete the scale and those that had the researcher or clinician complete the scale in consultation with the patient. The location of administration (clinic, home, via telephone or internet) varied between the scales (as reported in Table 3). The time to complete the scale was reported in eight of the 43 adherence scales. Reported times varied from less than 5 min [49,56,58,68] to approximately 25 min (Table 2) [69]. The scales taking less than 5 min to complete consisted of 4 to 14 items. Twelve min was required to complete a 19-item scale and 25 min to complete a 25-item scale [69,75].

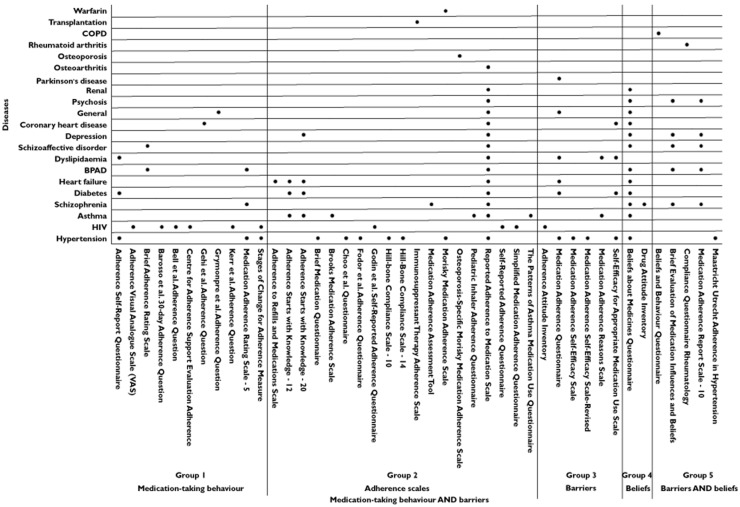

Figure 2 illustrates the conditions in which the adherence scales have been validated. Most of the adherence scales have been validated in a single disease population [4,8,9,40,42,44,47,49,51,53,54,56–59,62,72] (Figure 2). The Medication Adherence Questionnaire (MAQ), which is a simple four-item questionnaire, has been validated in a broad range of diseases, including hypertension, dyslipidaemia, heart failure and Parkinson's disease [73,76–78].

Figure 2.

Disease populations used to validate self-report adherence scales

Approaches to assessing self-report adherence scales

Assessing the validity of self-report adherence scales differed among the 60 included studies. Details of the studies, assessment of internal consistency, comparison measures and whether the scale was significantly correlated with the comparison measure are provided in Table 3. Similar approaches to validation were seen from scales with similar content.

Medication-taking behaviour

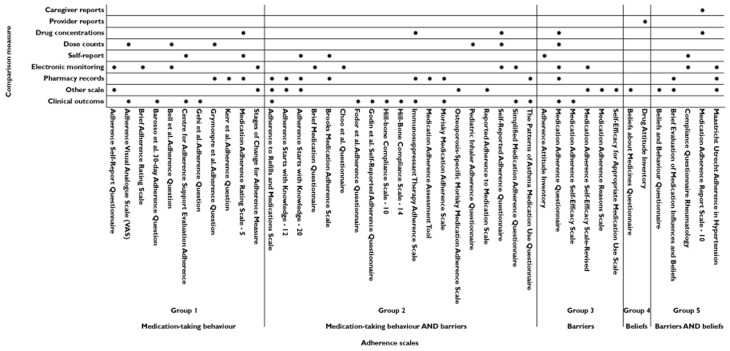

The primary method for assessing group 1 and group 2 scales was to determine the correlation between the scale and an objective measure of adherence. Twenty-eight of the 30 scales included in groups 1 and 2 assessed how well the scale correlated with an objective measure of adherence, eight of these scales have been assessed against MEMS and 12 against clinical outcomes (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison measures of medication-taking behaviour used to validate the self-report adherence scales

Barriers and beliefs

Scales in groups 3–5 were more likely to rely on alternative approaches to validation. Content validity was typically assessed via a panel of subject matter experts. A range of approaches was utilized for construct validity, including item analysis against tools validated to elicit specific types of health beliefs and factor analyses of responses to other scales or semi-structured interviews.

Three of the six group 3 scales (scales that contain items that elicit information on barriers to adherence only) have been assessed against an objective measure of adherence (one using MEMS, one using clinical outcomes and one using MEMS and clinical outcomes). All six of these scales have been tested for content validity [63–66,73,79] and four have also been tested for construct validity [63,64,66,73].

Adherence scales that solely focus on eliciting information regarding a patient's beliefs about their medicines (group 4) have not been assessed against objective measures of adherence. The Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire and DAI have been significantly correlated with other adherence scales (Table 3). Both scales have been tested for content validity, in addition the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire has also been tested for construct validity [4,10].

Two out of the five group 5 scales (beliefs and barriers) have assessed the correlation between the scale and an objective measure of adherence (both against MEMS). All five of the adherence scales have been correlated with subjective measures: other scales (n = 3), self-report (n = 1) and caregiver reports (n = 1). Four of these adherence scales have also been correlated with objective measures of adherence (Figure 3). All of these adherence scales have been tested for content validity and three (BBQ, BEMIB and MARS-10) have been tested for construct validity [67,68,70].

Identifying non-adherence

Many self-report adherence scales have recommended cut-offs for identifying non-adherent patients. Twenty-eight scales categorized medication adherence by determining the overall score and separating the population into two groups: adherent and non-adherent [4,9,33,39,42–47,49–51,53,54,56–63,65,68,72,79,80]. Where reported, the cut-off point to identify non-adherence is most commonly the score that corresponds to patients that took 80% of their medicines as ascertained by an objective measure of adherence such as MEMS. Some scales, such as the Beliefs and Behaviour Questionnaire (BBQ) [67], suggest a cut-off point that corresponds to the score of another self-report adherence scale which has been seen to correspond to patients that took 80% of their medicines according to an objective measure. Other adherence scales, such as the DAI, AAI and MASES-R first split the population into adherent and non-adherent based upon responses to questions about whether medicines were taken or not, and then compared the mean scores of the adherence scales to determine the cut-off [4,63,79]. The SERAD and Gehi et al. Adherence Question contain direct medication-taking behaviour questions and answers to these questions are utilized to determine the percentage of adherence and thus dichotomize adherence [9,59].

A small number of adherence scales have taken a different approach to assigning the adherence cut-off. The MAQ, MMAS, Brief Medication Questionnaire, ASRQ and VAS divided non-adherence into more than two groups, ranging from three to seven [34,40,41,52,73]. This categorization further differentiated between different levels of patient's adherence to their medicines. The MAQ and MMAS categorized the population into high, medium and low levels of adherence [34,73]. The MMAS cut-off points were selected based on the correlation with blood pressure control. The Brief Medication Questionnaire grouped the study population into repeat, sporadic and no non-adherence [40]. The ASRQ and VAS classified non-adherence into six and seven levels, respectively based on the researchers' expertise [41,52].

A small number of scales (12) have assessed the sensitivity and specificity of their cut-off against an objective measure of adherence. The results of these studies are reported in Table 3.

Discussion

We identified 43 adherence scales that have been correlated with a comparison measure of adherence. The identified adherence scales elicit information regarding different facets of adherence including medication-taking behaviour, barriers to and determinants of adherence and beliefs associated with adherence. This information, where accurate, can be put to different uses. Self-report adherence scales can (i) measure medication-taking behaviour, where use of the scale either complements objective measures, or is used as an alternative to objective measures and/or (ii) identify reasons for a patient's non-adherence, by identifying patient-specific barriers or beliefs that impede adherence. The data obtained in this systematic review provide information on how well specific adherence scales can be expected to perform these tasks.

Most of the scales identified as group 1–3 focus on measuring medication-taking behaviour by asking direct questions about medication-taking behaviour or eliciting barriers to good medication-taking behaviour. Group 3 scales focus on barriers to adherence and have the potential to both measure medication-taking behaviour and identify barriers to adherence. The purpose of some group 3 scales is to measure medication-taking behaviour by eliciting information on barriers, as opposed to providing a comprehensive assessment of patient barriers to adherence. The MAQ, for example, is a short four-item group 3 scale that has been well-validated against objective measures of adherence. The demonstration of a significant correlation between the adherence scale and a suitable objective measure in patients with the same disease seems a reasonable minimum requirement on the use of a scale as an alternative to an objective measure. Of the 36 group 1–3 adherence scales, 20 have been significantly correlated with either MEMS or clinical outcomes. Nine of the 36 adherence scales exploring medication-taking behaviour significantly correlated with the MEMS. The MEMS can record the time of dose actuation and can provide detailed information on medication-taking behaviour over time [28–30]. Fifteen group 1–3 adherence scales have been correlated with clinical outcomes. Few scales have been shown to correlate with MEMS or clinical outcomes in multiple disease states, making the choice of a scale more difficult in patient groups other than those included in the validation studies.

A link between specific levels of adherence and clinical outcomes has been demonstrated in some disease states (e.g. HIV [25,53,81] and cardiovascular disease [9,82,83]). For the vast majority of disease states, however, no such link has been made. Most adherence scales provide suggested cut-offs for identifying ‘non-adherent’ patients. Cut-offs permit the identification of patients who may be non-adherent and benefit from education or support. However, the arbitrary nature of the cut-offs provided for most self-report adherence scales needs to be kept in mind. Dichotomizing adherence does not differentiate between types of non-adherence, repeat vs. sporadic adherence or patients at different stages of the medication-taking process. Recent taxonomies of adherence recognize the dynamic nature of patient medication-taking behaviour. Vrijens et al. acknowledges that the process of medication-taking starts when the patient takes the first dose of medicine (initiation) continues with the implementation of the regimen and ends when the patient discontinues the medicine [12]. Gearing et al. propose a six-phase dynamic model of adherence: treatment initiation, treatment trial, partial treatment acceptance, intermittent treatment adoption, premature discontinuation and full adherence [84]. An important area for future research is the use of self-report adherence scales to identify the different types of non-adherence suggested by Vrijens et al. [12] and Gearing et al. [84].

A substantial number of scales have been validated against clinical outcomes, but no direct measure of medication-taking behaviour such as MEMS; examples include the Barroso 30-day Adherence Question and the Hill-Bone Compliance Scales. A demonstrated correlation between a self-report adherence scale and clinical outcomes in a specific patient population has relatively clear benefits for use of the scale in similar populations of patients. Knowing when this evidence is transferrable into new populations of patients, however, is challenging. For most disease states there are influences on clinical outcomes in addition to medication-taking behaviour. Factors that influence clinical outcomes play a part in addition to the many factors that may separate measures of adherence by self-report adherence scales from actual medication-taking behaviour. No doubt some of these scales have focused on clinical outcomes due to the availability of clinical data and the relative cost or availability of MEMS. However, validation of a scale against both clinical outcomes and direct measures of medication-taking behaviour is beneficial.

Scales included in groups 2 to 5 include items that elicit reasons a patient may be non-adherent. These scales may identify barriers the patient is experiencing to good medication-taking behaviour, and any patient-specific beliefs about their medicines that may influence adherence. While some Group 3 scales focus more on measuring medication-taking behaviour (e.g. the MAQ), others seek more detailed information on barriers that an individual may be experiencing (e.g. the Pediatric Inhaler Adherence Questionnaire). Scales included in groups 4 and 5 seek to identify patient beliefs about medicines that may influence adherence. Of these scales, the most extensively assessed is the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ). The BMQ-Specific identifies whether patients hold the belief that their medicine is necessary as well as whether the patient has concerns about their medicine [10].

Scales that focus on identifying reasons for non-adherence appropriately employ validation strategies focused on content and construct validity. The BMQ is a good example of a self-report adherence scale focused on measuring an aspect of adherence other than medication-taking behaviour. The items of the BMQ have been validated through confirmatory principle components analysis and the criterion and divergent validity assessed against similar items in the Illness Perceptions Questionnaire and the Sensitive Soma Scale [10]. The BMQ-Specific has been shown to correlate well with medication-taking behaviour measured by self-report adherence scales. Patients who believe their medicine to be necessary and have fewer concerns have consistently been shown to be more adherent in a range of diseases [85–89].

Scales such as the BMQ are not stand-alone comprehensive adherence scales but, like scales that focus on identifying barriers to adherence, they provide the opportunity for a more comprehensive assessment of a patient's adherence, and the drivers behind that adherence, than subjective or objective measures that focus on measuring medication-taking behaviour. The information provided by self-report adherence scales that seek to identify barriers and beliefs that are influencing adherence may prove useful in addition to accurate information on the patient's medication-taking behaviour. Specifically, these scales may help inform tailored interventions to improve medication adherence, but their use for this purpose is yet to be assessed.

Limitations

This systematic review only included studies of self-report adherence scales that included a comparison measure of medication-taking behaviour. This was deemed appropriate given the importance of measuring medication-taking behaviour in assessing adherence. A consequence of this criterion is that this study does not provide a comprehensive analysis of the validation of self-report adherence scales.

Conclusions

Self-report adherence scales have the potential to measure both medication-taking behaviour, and/or identify barriers and beliefs associated with adherence. Selecting an adherence scale requires consideration of what the adherence scale measures and how well it has been validated. Research on validating and using the existing self-report adherence scales as a measure of medication-taking behaviour is relatively strong. There has been less focus on assessing how information gained from scales that identify patient-specific barriers and beliefs associated with adherence may be used to support wise medicine use. This presents an important and exciting avenue for further research.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva: WHO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mardby AC, Akerlind I, Jorgensen T. Beliefs about medicines and self-reported adherence among pharmacy clients. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fawzi W, Abdel Mohsen MY, Hashem AH, Moussa S, Coker E, Wilson KC. Beliefs about medications predict adherence to antidepressants in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:159–169. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R. A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenics – reliability and discriminative validity. Psychol Med. 1983;13:177–183. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700050182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van de Steeg N, Sielk M, Pentzek M, Bakx C, Altiner A. Drug-adherence questionnaires not valid for patients taking blood-pressure-lowering drugs in a primary health care setting. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:468–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broekmans S, Dobbels F, Milisen K, Morlion B, Vanderschueren S. Pharmacologic pain treatment in a multidisciplinary pain center: do patients adhere to the prescription of the physician? Clin J Pain. 2010;26:81–86. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b91b22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005;43:521–530. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163641.86870.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambert EV, Steyn K, Stender S, Everage N, Fourie JM, Hill M. Cross-cultural validation of the hill-bone compliance to high blood pressure therapy scale in a South African, primary healthcare setting. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:286–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gehi AK, Ali S, Na B, Whooley MA. Self-reported medication adherence and cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary heart disease: the Heart and Soul Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1798–1803. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health. 1999;14:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unni EJ, Farris KB. Unintentional non-adherence and belief in medicines in older adults. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:265–268. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, Przemyslaw K, Demonceau J, Ruppar T, Dobbels F, Fargher E, Morrison V, Lewek P, Matyjaszczyk M, Mshelia C, Clyne W, Aronson JK, Urquhart J Team ABCP. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:691–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3. CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cutrona SL, Choudhry NK, Fischer MA, Servi AD, Stedman M, Liberman JN, Brennan TA, Shrank WH. Targeting cardiovascular medication adherence interventions. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2012;52:381–397. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2012.10211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenerty SD, West C, Davis SA, Kaplan SG, Feldman SR. The effect of reminder systems on patients' adherence to treatment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:127–135. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S26314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroeder K, Fahey T, Ebrahim S. Interventions for improving adherence to treatment in patients with high blood pressure in ambulatory settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004804. CD004804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schedlbauer A, Schroeder K, Peters TJ, Fahey T. Interventions to improve adherence to lipid lowering medication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004371.pub2. CD004371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eidlitz-Markus T, Zeharia A, Baum G, Mimouni M, Amir J. Use of the urine color test to monitor compliance with isoniazid treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Chest. 2003;123:736–739. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.3.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saberi P, Caswell N, Amodio-Groton M, Alpert P. Pharmacy-refill measure of adherence to efavirenz can predict maintenance of HIV viral suppression. AIDS Care. 2008;20:741–745. doi: 10.1080/09540120701694006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krousel-Wood M, Islam T, Webber LS, Re RN, Morisky DE, Muntner P. New medication adherence scale versus pharmacy fill rates in seniors with hypertension. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:59–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Boogaard J, Lyimo RA, Boeree MJ, Kibiki GS, Aarnoutse RE. Electronic monitoring of treatment adherence and validation of alternative adherence measures in tuberculosis patients: a pilot study. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:632–639. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.086462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu JR, Moser DK, Chung ML, Lennie TA. Objectively measured, but not self-reported, medication adherence independently predicts event-free survival in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2008;14:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velligan DI, Wang M, Diamond P, Glahn DC, Castillo D, Bendle S, Lam YW, Ereshefsky L, Miller AL. Relationships among subjective and objective measures of adherence to oral antipsychotic medications. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:1187–1192. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.9.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pai ALH, Drotar D, Kodish E. Correspondence between objective and subjective reports of adherence among adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Child Health Care. 2008;37:225–235. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Zolopa AR, Holodniy M, Sheiner L, Bamberger JD, Chesney MA, Moss A. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. AIDS. 2000;14:357–366. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mason BJ, Matsuyama JR, Jue SG. Assessment of sulfonylurea adherence and metabolic control. Diabetes Educ. 1995;21:52–57. doi: 10.1177/014572179502100109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schectman JM, Nadkarni MM, Voss JD. The association between diabetes metabolic control and drug adherence in an indigent population. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1015–1021. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.6.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remington G, Kwon J, Collins A, Laporte D, Mann S, Christensen B. The use of electronic monitoring (MEMS) to evaluate antipsychotic compliance in outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;90:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santschi V, Wuerzner G, Schneider MP, Bugnon O, Burnier M. Clinical evaluation of IDAS II, a new electronic device enabling drug adherence monitoring. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:1179–1184. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Onzenoort HA, Neef C, Verberk WW, van Iperen HP, de Leeuw PW, van der Kuy PH. Determining the feasibility of objective adherence measurement with blister packaging smart technology. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69:872–879. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daniels T, Goodacre L, Sutton C, Pollard K, Conway S, Peckham D. Accurate assessment of adherence: self-report and clinician report vs electronic monitoring of nebulizers. Chest. 2011;140:425–432. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zelikovsky N, Schast AP. Eliciting accurate reports of adherence in a clinical interview: development of the Medical Adherence Measure. Pediatr Nurs. 2008;34:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Byerly MJ, Nakonezny PA, Rush AJ. The Brief Adherence Rating Scale (BARS) validated against electronic monitoring in assessing the antipsychotic medication adherence of outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2008;100:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.12.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10:348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 35.Wagner GJ, Rabkin JG. Measuring medication adherence: are missed doses reported more accurately then perfect adherence? AIDS Care. 2000;12:405–408. doi: 10.1080/09540120050123800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barfod TS, Sorensen HT, Nielsen H, Rodkjaer L, Obel N. ‘Simply forgot’ is the most frequently stated reason for missed doses of HAART irrespective of degree of adherence. HIV Med. 2006;7:285–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lavsa SM, Holzworth A, Ansani NT. Selection of a validated scale for measuring medication adherence. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2011;51:90–94. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2011.09154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garfield S, Clifford S, Eliasson L, Barber N, Willson A. Suitability of measures of self-reported medication adherence for routine clinical use: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:149. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knobel H, Alonso J, Casado JL, Collazos J, Gonzalez J, Ruiz I, Kindelan JM, Carmona A, Juega J, Ocampo A. Validation of a simplified medication adherence questionnaire in a large cohort of HIV-infected patients: the GEEMA Study. AIDS. 2002;16:605–613. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Svarstad BL, Chewning BA, Sleath BL, Claesson C. The Brief Medication Questionnaire: a tool for screening patient adherence and barriers to adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;37:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schroeder K, Fahey T, Hay AD, Montgomery A, Peters TJ. Adherence to antihypertensive medication assessed by self-report was associated with electronic monitoring compliance. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:650–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bell DJ, Kapitao Y, Sikwese R, van Oosterhout JJ, Lalloo DG. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients receiving free treatment from a government hospital in Blantyre, Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:560–563. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180decadb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grymonpre RE, Didur CD, Montgomery PR, Sitar DS. Pill count, self-report, and pharmacy claims data to measure medication adherence in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:749–754. doi: 10.1345/aph.17423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kerr T, Hogg RS, Yip B, Tyndall MW, Montaner J, Wood E. Validity of self-reported adherence among injection drug users. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2008;7:157–159. doi: 10.1177/1545109708320686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matza LS, Park J, Coyne KS, Skinner EP, Malley KG, Wolever RQ. Derivation and validation of the ASK-12 adherence barrier survey. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1621–1630. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hahn SR, Park J, Skinner EP, Yu-Isenberg KS, Weaver MB, Crawford B, Flowers PW. Development of the ASK-20 adherence barrier survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:2127–2138. doi: 10.1185/03007990802174769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Godin G, Gagné C, Naccache H. Validation of a self-reported questionnaire assessing adherence to antiretroviral medication. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2003;17:325–332. doi: 10.1089/108729103322231268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reynolds K, Viswanathan HN, O'Malley CD, Muntner P, Harrison TN, Cheetham TC, Hsu JW, Gold DT, Silverman S, Grauer A, Morisky DE. Psychometric properties of the Osteoporosis-specific Morisky Medication Adherence Scale in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis newly treated with bisphosphonates. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:659–670. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodriguez Martinez CE, Sossa MP, Rand CS. Validation of a questionnaire for assessing adherence to metered-dose inhaler use in asthmatic children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2007;20:243–253. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schuz B, Wurm S, Ziegelmann JP, Warner LM, Tesch-Romer C, Schwarzer R. Changes in functional health, changes in medication beliefs, and medication adherence. Health Psychol. 2011;30:31–39. doi: 10.1037/a0021881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kripalani S, Risser J, Gatti ME, Jacobson TA. Development and evaluation of the Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS) among low-literacy patients with chronic disease. Value Health. 2009;12:118–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, Swetzes C, Jones M, Macy R, Kalichman MO, Cherry C. A simple single-item rating scale to measure medication adherence: further evidence for convergent validity. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2009;8:367–374. doi: 10.1177/1545109709352884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barroso PF, Schechter M, Gupta P, Bressan C, Bomfim A, Harrison LH. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and persistence of HIV RNA in semen. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:435–440. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mannheimer SB, Mukherjee R, Hirschhorn LR, Dougherty J, Celano SA, Ciccarone D, Graham KK, Mantell JE, Mundy LM, Eldred L, Botsko M, Finkelstein R. The CASE adherence index: a novel method for measuring adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care. 2006;18:853–861. doi: 10.1080/09540120500465160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Willey C, Redding C, Stafford J, Garfield F, Geletko S, Flanigan T, Melbourne K, Mitty J, Caro JJ. Stages of change for adherence with medication regimens for chronic disease: development and validation of a measure. Clin Ther. 2000;22:858–871. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(00)80058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brooks CM, Richards JM, Kohler CL, Soong SJ, Martin B, Windsor RA, Bailey WC. Assessing adherence to asthma medication and inhaler regimens: a psychometric analysis of adult self-report scales. Med Care. 1994;32:298–307. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199403000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choo PW, Rand CS, Inui TS, Lee ML, Cain E, Cordeiro-Breault M, Canning C, Platt R. Validation of patient reports, automated pharmacy records, and pill counts with electronic monitoring of adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Med Care. 1999;37:846–857. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199909000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chisholm MA, Lance CE, Williamson GM, Mulloy LL. Development and validation of an immunosuppressant therapy adherence barrier instrument. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;20:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Munoz-Moreno JA, Fumaz CR, Ferrer MJ, Tuldra A, Rovira T, Viladrich C, Bayes R, Burger DM, Negredo E, Clotet B. Assessing self-reported adherence to HIV therapy by questionnaire: the SERAD (Self-Reported Adherence) Study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:1166–1175. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greaves CJ, Hyland ME, Halpin DM, Blake S, Seamark D. Patterns of corticosteroid medication use: non-adherence can be effective in milder asthma. Prim Care Respir J. 2005;14:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pcrj.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Klerk E, van der Heijde D, van der Tempel H, van der Linden S. Development of a questionnaire to investigate patient compliance with antirheumatic drug therapy. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:2635–2641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim MT, Hill MN, Bone LR, Levine DM. Development and testing of the hill-bone compliance to high blood pressure therapy scale. Summer. 2000;15:90–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7117.2000.tb00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lewis SJ, Abell N. Development and evaluation of the Adherence Attitude Inventory. Res Soc Work Pract. 2002;12:107–123. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ogedegbe G, Mancuso CA, Allegrante JP, Charlson ME. Development and evaluation of a medication adherence self-efficacy scale in hypertensive African-American patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:520–529. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Risser J, Jacobson TA, Kripalani S. Development and psychometric evaluation of the self-efficacy for appropriate medication use scale (SEAMS) in low-literacy patients with chronic disease. J Nurs Meas. 2007;15:203–219. doi: 10.1891/106137407783095757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Unni EJ, Farris KB. Development of a new scale to measure self-reported medication nonadherence. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2009.06.005. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.George J, Mackinnon A, Kong DC, Stewart K. Development and validation of the Beliefs and Behaviour Questionnaire (BBQ) Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Warren KA, Golshan S, Perkins DO, Jeste DV. Brief evaluation of medication influences and beliefs: development and testing of a brief scale for medication adherence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:404–409. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000130554.63254.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wetzels G, Nelemans P, van Wijk B, Broers N, Schouten J, Prins M. Determinants of poor adherence in hypertensive patients: development and validation of the ‘Maastricht Utrecht Adherence in Hypertension (MUAH)-questionnaire’. Patient Educ Counsel. 2006;64:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thompson K, Kulkarni J, Sergejew AA. Reliability and validity of a new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophr Res. 2000;42:241–247. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jonsdottir H, Opjordsmoen S, Birkenaes AB, Engh JA, Ringen PA, Vaskinn A, Aamo TO, Friis S, Andreassen OA. Medication adherence in outpatients with severe mental disorders: relation between self-reports and serum level. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:169–175. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181d2191e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fodor GJ, Kotrec M, Bacskai K, Dorner T, Lietava J, Sonkodi S, Rieder A, Turton P. Is interview a reliable method to verify the compliance with antihypertensive therapy? An international central-European study. J Hypertens. 2005;23:1261–1266. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000170390.07321.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thompson IR, Bidgood P, Petroczi A, Denholm-Price JC, Fielder MD, EuResist Network Study G. An alternative methodology for the prediction of adherence to anti HIV treatment. AIDS Res Ther. 2009;6:9–14. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-6-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Klerk E, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, van der Tempel H, van der Linden S. The compliance-questionnaire-rheumatology compared with electronic medication event monitoring: a validation study. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2469–2475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shalansky SJ, Levy AR, Ignaszewski AP. Self-reported Morisky score for identifying nonadherence with cardiovascular medications. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1363–1368. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Toll BA, McKee SA, Martin DJ, Jatlow P, O'Malley SS. Factor structure and validity of the Medication Adherence Questionnaire (MAQ) with cigarette smokers trying to quit. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:597–605. doi: 10.1080/14622200701239662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Elm JJ, Kamp C, Tilley BC, Guimaraes P, Fraser D, Deppen P, Brocht A, Weaver C, Bennett S, Investigators NN-P Coordinators. Self-reported adherence versus pill count in Parkinson's disease: the NET-PD experience. Mov Disord. 2007;22:822–827. doi: 10.1002/mds.21409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fernandez S, Chaplin W, Schoenthaler AM, Ogedegbe G. Revision and validation of the medication adherence self-efficacy scale (MASES) in hypertensive African Americans. J Behav Med. 2008;31:453–462. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9170-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Clayton CD, Veach J, Macfadden W, Haskins J, Docherty JP, Lindenmayer JP. Assessment of clinician awareness of nonadherence using a new structured rating scale. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16:164–169. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000375712.85454.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gardner EM, Hullsiek KH, Telzak EE, Sharma S, Peng G, Burman WJ, MacArthur RD, Chesney M, Friedland G, Mannheimer SB. Antiretroviral medication adherence and class-specific resistance in a large prospective clinical trial. AIDS. 2010;24:395–403. doi: 10.1097/qad.0b013e328335cd8a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Addison CC, Jenkins BW, Sarpong D, Wilson G, Champion C, Sims J, White MS. Relationship between medication use and cardiovascular disease health outcomes in the Jackson Heart Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:2505–2515. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8062505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, Islam T, Morisky DE, Webber LS. Barriers to and determinants of medication adherence in hypertension management: perspective of the cohort study of medication adherence among older adults. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:753–769. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gearing RE, Townsend L, MacKenzie M, Charach A. Reconceptualizing medication adherence: six phases of dynamic adherence. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2011;19:177–189. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2011.602560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Horne R, Weinman J. Self-regulation and self-management in asthma: exploring the role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medication. Psychol Health. 2002;17:17–32. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ross S, Walker A, MacLeod MJ. Patient compliance in hypertension: role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:607–613. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Berglund E, Lytsy P, Westerling R. Adherence to and beliefs in lipid-lowering medical treatments: a structural equation modeling approach including the necessity-concern framework. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Alhalaiqa F, Deane KH, Nawafleh AH, Clark A, Gray R. Adherence therapy for medication non-compliant patients with hypertension: a randomised controlled trial. J Hum Hypertens. 2012;26:117–126. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2010.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Petrie KJ, Perry K, Broadbent E, Weinman J. A text message programme designed to modify patients' illness and treatment beliefs improves self-reported adherence to asthma preventer medication. Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17:74–84. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, Wu AW. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) AIDS Care. 2000;12:255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dobbels F, Berben L, De Geest S, Drent G, Lennerling A, Whittaker C, Kugler C. Transplant360 Task F. The psychometric properties and practicability of self-report instruments to identify medication nonadherence in adult transplant patients: a systematic review. Transplantation. 2010;90:205–219. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181e346cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lapshin O. Assessing medication adherence in clinical practice. Bridg East West Psychiatry. 2006;4:42–45. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kleeberger CA, Phair JP, Strathdee SA, Detels R, Kingsley L, Jacobson LP. Determinants of heterogeneous adherence to HIV-antiretroviral therapies in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26:82–92. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200101010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zeller A, Ramseier E, Teagtmeyer A, Battegay E. Patients' self-reported adherence to cardiovascular medication using electronic monitors as comparators. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:2037–2043. doi: 10.1291/hypres.31.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Matza LS, Yu-Isenberg KS, Coyne KS, Park J, Wakefield J, Skinner EP, Wolever RQ. Further testing of the reliability and validity of the ASK-20 adherence barrier questionnaire in a medical center outpatient population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:3197–3206. doi: 10.1185/03007990802463642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Erickson SR, Coombs JH, Kirking DM, Azimi AR. Compliance from self-reported versus pharmacy claims data with metered-dose inhalers. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:997–1003. doi: 10.1345/aph.10379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang Y, Kong MC, Ko Y. Psychometric properties of the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale in patients taking warfarin. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108:1–7. doi: 10.1160/TH12-05-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hill-Briggs F, Gary TL, Bone LR, Hill MN, Levine DM, Brancati FL. Medication adherence and diabetes control in urban African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Health Psychol. 2005;24:349–357. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vik SA, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB, Patten SB, Johnson JA, Romonko-Slack L. Assessing medication adherence among older persons in community settings. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;12:152–164. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang Y, Lee J, Tang WE, Toh MP, Ko Y. Validity and reliability of a self-reported measure of medication adherence in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Singapore. Diabet Med. 2012;29:338–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Brown C, Battista DR, Bruehlman R, Sereika SS, Thase ME, Dunbar-Jacob J. Beliefs about antidepressant medications in primary care patients: relationship to self-reported adherence. Med Care. 2005;43:1203–1207. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000185733.30697.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]