Abstract

The human calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) is widely expressed in the body, where its activity is regulated by multiple orthosteric and endogenous allosteric ligands. Each ligand stabilizes a unique subset of conformational states, which enables the CaSR to couple to distinct intracellular signalling pathways depending on the extracellular milieu in which it is bathed. Differential signalling arising from distinct receptor conformations favoured by each ligand is referred to as biased signalling. The outcome of CaSR activation also depends on the cell type in which it is expressed. Thus, the same ligand may activate diverse pathways in distinct cell types. Given that the CaSR is implicated in numerous physiological and pathophysiological processes, it is an ideal target for biased ligands that could be rationally designed to selectively regulate desired signalling pathways in preferred cell types.

Linked ArticlesThis article is part of a themed section on Molecular Pharmacology of GPCRs. To view the other articles in this section visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2014.171.issue-5

Keywords: calcium-sensing receptor, biased signalling, allosteric modulation, naturally occurring mutations

The CaSR protein and its ligands

The extracellular calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) is a family C GPCR that plays a pivotal role in maintaining extracellular calcium (Ca2+o) homeostasis. [Drug/molecular target nomenclature throughout this manuscript conforms to BJP's Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Alexander et al., 2013)]. It is composed of 1078 amino acids in four main domains beyond the signal peptide (http://www.casrdb.mcgill.ca). These are an N-terminal extracellular Venus FlyTrap (VFT) domain (residues 22–528) linked via a cysteine-rich domain (residues 529–612) to the heptahelical signalling domain (residues 613–862) and a C-terminal intracellular domain (residues 863–1078). The VFT domain provides binding sites for the endogenous (orthosteric) agonists Ca2+o and Mg2+o, although Ca2+o can also activate the CaSR via the heptahelical or extracellular loop domains, as evidenced by its activity at ‘headless’ CaSR constructs that lack the N-terminal domain of the receptor (Ray and Northup, 2002; Mun et al., 2004; Ray et al., 2005). The CaSR also responds to various di- and tervalent cations, including Gd3+, Al3+, Sr2+, Ba2+, Co2+, Fe2+, Ni2+ and Pb2+ (McGehee et al., 1997; Handlogten et al., 2000). The VFT is additionally the site of action of endogenous allosteric agonists, including cationic polyamines, such as spermine and spermidine (Quinn et al., 1997), and endogenous allosteric modulators, including L-amino acids and glutathione analogues (for a review, see Conigrave and Hampson, 2010). Aminoglycoside antibiotics, such as neomycin, gentamicin and tobramycin, also activate the CaSR (McLarnon et al., 2002; Ward et al., 2002), although their binding site is yet to be identified. Synthetic allosteric modulators that bind in the heptahelical domain and extracellular loops of the CaSR have also been identified, which include calcimimetics, such as cinacalcet (and related phenylalkylamines) (Nemeth et al., 1998), and calcilytics, such as NPS 2143 (Nemeth, 2002).

Biased signalling from the CaSR

The CaSR couples to Gq/11, Gi/o and G12/13 (Huang et al., 2004; Davey et al., 2012) and even Gs in some cell contexts (Mamillapalli and Wysolmerski, 2010). Stimulation of distinct effectors downstream of these G proteins mediates cellular responses to CaSR activation (Figures 3). Its promiscuous binding to numerous endogenous ligands, and its propensity to couple to multiple G proteins and downstream signalling pathways, make the CaSR an ideal candidate for biased signalling (also known as stimulus bias, ligand-directed trafficking of receptor stimulus, functional selectivity or biased agonism). Biased signalling arises from the ability of different ligands to favour distinct conformational receptor states, each possessing its own coupling preferences to downstream signalling pathways (Kenakin, 2011).

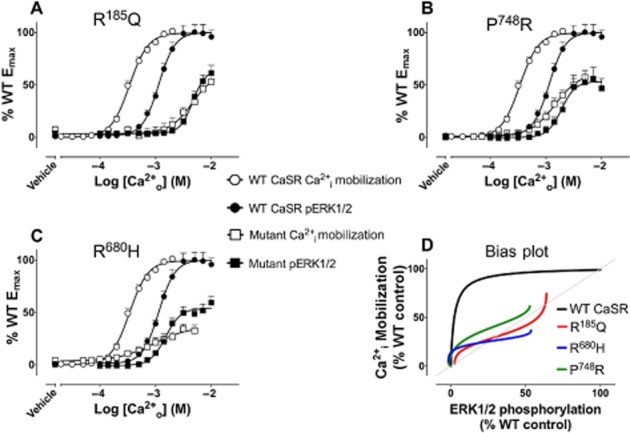

Figure 3.

Biased signalling engendered by naturally occurring CaSR mutations. Concentration–response curves (A–C) to Ca2+o in Ca2+i mobilization assays or ERK1/2 phosphorylation assays at the WT CaSR or mutant CaSRs (the mutation is stated in the title of each graph) and bias plots (D) corresponding to these curves. The bias plot depicts the response of cells expressing the receptor to equimolar concentrations of Ca2+o measured in Ca2+i mobilization assays (y axis) and ERK1/2 phosphorylation assays (x axis). If the receptor shows no preference for either pathway, points on the bias plots are coincident and the plots overlap with the line of identity (grey line). If it favours one of the pathways, the points fall away from this line towards the preferred pathway. Thus, naturally occurring mutations can engender stimulus bias.

Biased signalling operates in response to various endogenous CaSR agonists and modulators. In HEK293 cells, for instance, when stimulated with Ca2+o, the CaSR preferentially couples to inhibition of cAMP production and stimulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) accumulation over phosphorylation of ERK 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) (Thomsen et al., 2012a). Spermine, however, strongly favours ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Thomsen et al., 2012a). Similarly, although both Ca2+o and L-phenylalanine (L-Phe) stimulate CaSR-mediated Ca2+i release, Ca2+o promotes higher frequency Ca2+i oscillations (up to 4 min−1), whereas L-Phe mediates lower frequency oscillations (up to 2 min−1) (Rey et al., 2010). Ca2+o-mediated sinusoidal Ca2+i release is facilitated by activation of PLC, which promotes the release of IP3 and DAG from the parent phospholipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. IP3 causes release of Ca2+i from intracellular stores and DAG activates PKC, which subsequently phosphorylates the CaSR and attenuates signalling (Bai et al., 1998; Davies et al., 2007). In contrast, activation of the CaSR by L-Phe is reported to promote its interaction with G12/13, Rho, filamin-A and transient receptor potential cation (TRPC) 1 channels, resulting in TRPC1 channel opening and Ca2+ influx from the extracellular fluid (Rey et al., 2005; 2006; 2010). Intriguingly, higher frequency Ca2+o-stimulated Ca2+i oscillations and lower frequency L-Phe-stimulated Ca2+i oscillations have also been observed in human proximal tubule epithelial cells (Rey et al., 2005). These results suggest that the cellular location of CaSR expression and its subsequent exposure to a subset of ligands that are present in specific compartments (e.g. in the luminal compartments of the gastrointestinal tract or renal tubules) may govern its signalling, enabling selective activation of intracellular signalling pathways depending on which ligand binds the receptor.

This review will summarize our current understanding of the physiological roles of the human CaSR, the implications of biased signalling arising from the CaSR and how biased signalling may be engendered to manipulate CaSR function in pathological states.

The CaSR's roles in calcium homeostasis

Two well-characterized actions of the CaSR in response to a rise in systemic Ca2+o level are (i) suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH) secretion and (ii) suppression of renal calcium re-absorption arising, respectively, from receptors expressed by parathyroid chief cells and renal cortical thick ascending limb cells of Henle's loop. Indeed, in response to hypercalcaemia, the CaSR mediates enhanced renal calcium excretion, independent of changes in PTH levels (Kantham et al., 2009; Loupy et al., 2012). This effect requires CaSR-mediated inhibition of Ca2+ re-absorption via both paracellular and transcellular pathways (Figure 2) (for a review, see Riccardi and Brown, 2010). Together, these effects rapidly stimulate renal calcium excretion and lower the serum calcium level. In addition, the CaSR appears to mediate three further responses to elevated Ca2+o: (i) suppression of 1,25(OH)2D3 synthesis, which lowers the drive for intestinal Ca2+ absorption; (ii) negative modulation of PTH-induced phosphate excretion to raise the serum inorganic phosphate level; and (iii) decreased osteoclastic-dependent bone resorption. CaSR-dependent suppression of bone resorption is mediated via receptors on osteoblasts, which suppress osteoclastogenesis, via receptors on thyroid C-cells, which promote the release of calcitonin, and via receptors on osteoclasts themselves, which suppress resorptive activity (for a review, see Riccardi and Kemp, 2012). The concerted effect of these various CaSR-mediated responses is a pronounced decrease in ionized Ca2+o concentration and a more modest increase in serum phosphate level.

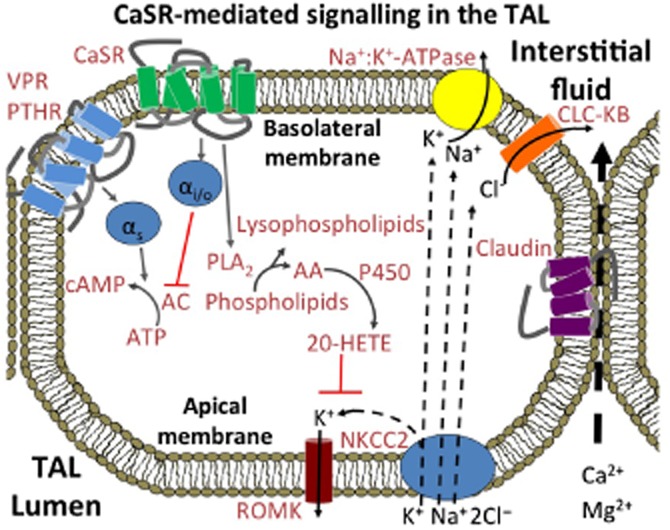

Figure 2.

CaSR-mediated control of ion transport across the thick ascending limb. On the basolateral membrane of cells in the cortical thick ascending limb (cTAL), Ca2+o-induced suppression of transepithelial Ca2+ transport is dependent on PLA2-mediated inhibition of renal outer medullary potassium (ROMK) channels (Wang et al., 1997; Huang et al., 2007; Cha et al., 2011), which contributes to enhanced urinary excretion of Na+, Ca2+ and Mg2+. In addition, Ca2+o suppresses transcellular Na+ and Cl− re-absorption secondary to Gi/o-mediated inhibition of PTH- and vasopressin-stimulated cAMP production (de Jesus Ferreira et al., 1998; for review, see Gamba and Friedman, 2009). Blockade of K+ recycling across the luminal membrane and impaired NaCl reabsorption induce an attendant reduction in the lumen positive transepithelial potential that drives Ca2+o re-absorption. In consequence, paracellular transport of Ca2+ (and Mg2+) is impaired resulting in enhanced urinary excretion. In addition to this acute mechanism for Ca2+o-dependent inhibition of Ca2+ re-absorption, the CaSR has recently been reported to up-regulate the expression of claudin-14, a key inhibitor of a claudin-16/19-dependent divalent cation selective paracellular pathway in the thick ascending limb (Gong et al., 2012).

The CaSR also facilitates the transport of Ca2+ across the placenta in support of fetal skeletal development and growth (Kovacs et al., 1998) and promotes Ca2+ transport into milk during lactation via its expression in mammary duct epithelial cells (Cheng et al., 1998; VanHouten, 2005). Recently, selective knockout of the CaSR in the lactating mouse mammary gland confirmed that the mammary gland receptor promotes calcium transport into milk and, in turn, calcium accrual in suckling neonates (Mamillapalli et al., 2013). Furthermore, CaSR-null lactating dams from this model exhibited hypercalcaemia and appropriately suppressed serum PTH levels, demonstrating that the mammary gland CaSR has a physiological role in maintaining normal maternal serum calcium levels during lactation (Mamillapalli et al., 2013).

Roles of the CaSR in bone and cartilage cells

The CaSR has been implicated in bone mineralization and linear bone growth. In osteoblasts, the CaSR modulates the expression of genes that promote bone mineralization and osteoblast differentiation. Activation of the CaSR in osteoblasts by Sr2+, for instance, stimulates phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase) and consequent Akt phosphorylation (Rybchyn et al., 2011). CaSR activation also promotes Wnt-dependent β-catenin translocation to the nucleus and attendant osteoblast differentiation (Rybchyn et al., 2011). The CaSR promotes the differentiation of cartilage-producing chrondrocytes in the growth plate, leading to the growth of the long bones during skeletal development (Chang et al., 2008).

The CaSR in cells of the osteoblast–osteocyte lineage also suppresses osteoclastogenesis by inducing down-regulation of receptor activator of NFκB ligand (TNFSF11) and up-regulation of its decoy receptor osteoprotegerin (Brennan et al., 2009; Saidak and Marie, 2012). Reduced expression of TNFSF11 results in reduced osteoclast number, reduced osteoclast activity and reduced bone resorption (Dvorak-Ewell et al., 2011). In addition, CaSRs expressed on osteoclasts appear to mediate high Ca2+o-induced apoptosis (Kanatani et al., 1999; Mentaverri et al., 2006), which is dependent on PLC, IP3, nuclear translocation of NF-κB and enhanced caspase activity (Mentaverri et al., 2006).

Some of the effects of elevated Ca2+o in bone are mediated not only by the CaSR but also by other family C GPCRs, including GPRC6, which mediates some of the responses to Ca2+o in osteoblasts and thereby contributes to the control of bone mineralization (Pi et al., 2010).

Roles of the CaSR in tissues that are not involved in calcium homeostasis

Perhaps surprisingly, the CaSR is also expressed in tissues that are not involved in Ca2+o homeostasis. In the CVS, for example, CaSR expression in the heart and blood vessels has been linked to the modulation of BP (see Smajilovic et al., 2011 for a review) and protection against vascular calcification (Alam et al., 2009), raising the possibility that a drug that selectively modulates CaSR function in this setting might be effective at lowering BP and/or reducing or even reversing calcification.

In the CNS, the CaSR is widely expressed in neurons and glial cells and is subject to developmental regulation (Rogers et al., 1997). For example, it promotes neuronal differentiation, myelination and growth during development (Ferry et al., 2000; Chattopadhyay et al., 2008; Vizard et al., 2008), and modulates neurotransmission in post-natal life (Phillips et al., 2008).

In addition, the CaSR acts as an ionic strength sensor in the subfornical organ linked to the control of BP and whole body salt and water metabolism (Washburn et al., 1999). It also directly modulates salt and water transport in the colon (Geibel and Hebert, 2009) and renal tubules (for a review, see Riccardi and Brown, 2010).

CaSR expression has also been demonstrated in monocytes and macrophages (Yamaguchi et al., 1998; Olszak et al., 2000), in which, alongside GPRC6, it activates the key inflammatory mediator NLRP3 (Lee et al., 2012; Rossol et al., 2012), and in keratinocytes it acts as a mediator of differentiation (Tu et al., 2008). Consistent with this latter idea, keratinocyte-specific CaSR null mice demonstrate disordered skin development (Bikle et al., 2012; Tu et al., 2012).

Modulation of macronutrient digestion, absorption, nutrient disposition and storage

The CaSR has multiple roles in the gastrointestinal tract dependent primarily on its expression by enteroendocrine cells as well as epithelial cells such as gastric parietal cells (for a review, see Conigrave and Brown, 2006). Thus, CaSRs expressed by enteroendocrine G-cells detect nutrient L-amino acids (Geibel and Hebert, 2009) to stimulate the release of gastrin and thus gastric acid secretion (Feng et al., 2010), and CaSRs expressed by I-cells mediate cholecystokinin (CCK) release (Liou et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011) to support the digestion and absorption of macronutrients. In addition, CaSRs expressed by K- and L-cells mediate amino acid–induced release of gastric inhibitory peptide and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), respectively (Mace et al., 2012), to provide a mechanism by which gut luminal contents facilitate nutrient-dependent insulin release.

Consistent with its effects on gut hormone release and gastric acid secretion, CaSRs expressed in hepatocytes promote bile flow (Canaff et al., 2001) to facilitate digestion and absorption of fats and CaSRs expressed on adipocytes, in turn, facilitate fat storage by promoting adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis (Cifuentes and Rojas, 2008; He et al., 2011; 2012; Reyes et al., 2012). CaSR activation in adipose tissue also elevates the production of cytokines and chemokines, including IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and CC chemokine 2 (Cifuentes et al., 2012) and pro-inflammatory cytokines increase CaSR expression in adipocytes (Cifuentes et al., 2010), suggesting the existence of a positive feedback loop. CaSR-mediated release of GLP-1 and the appetite reducing peptide, peptide YY (Mace et al., 2012), as well as CCK provide satiety signals to the hypothalamus for the suppression of further feeding. Collectively, these findings suggest that the CaSR plays a fundamental role in the regulation of appetite and nutrient disposal.

Finally, the CaSR has been detected in pancreatic islet beta-cells, with evidence suggesting it modulates insulin release (Squires et al., 2000; Leech and Habener, 2003; Gray et al., 2006; Parkash and Asotra, 2011).

Modulation of colonic epithelial cell differentiation and proliferation

The human colonic epithelium is composed of tubular invaginations known as ‘crypts’, at the base of which, stem cells proliferate rapidly and rise progressively towards the luminal surface. At the crypt base, CaSR expression is barely detectable, but it increases substantially as epithelial cells move towards the crypt apex promoting differentiation and suppressing proliferation (for a review, see Peterlik et al., 2013) dependent, in part, on Ca2+i mobilization and ERK1/2 activation (Bhagavathula et al., 2005; Rey et al., 2010). Evidence that dietary calcium protects against colon cancer in human populations (for a review, see Peterlik et al., 2013) and that CaSR expression is markedly down-regulated in colon cancer (Kallay et al., 2003; Chakrabarty et al., 2005; Hizaki et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2012) has led to the hypothesis that the CaSR acts as a colonic tumour suppressor (for reviews, see Brennan et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2013). Consistent with this idea, CaSR activators promote Wnt5a secretion to suppress inappropriate canonical Wnt signalling in colon cancer cells (MacLeod et al., 2007).

Broader implications of the CaSR as a drug target

Given that the CaSR mediates diverse sensing and signalling functions and associated cellular responses in a surprising diversity of tissues and physiological contexts, it may be a suitable target for the treatment of disorders in which appropriate up- or down-regulated expression or increased or decreased receptor function could be engendered in a tissue and/or signal pathway selective manner.

Impact of CaSR mutations and polymorphisms in disorders of calcium metabolism and other disorders

The broad nature of the CaSR's physiological roles is highlighted by the effects of many naturally occurring mutations or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that occur in the CaSR gene. These include, as might be expected, disorders of calcium homeostasis, including familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia and neonatal severe hyperparathyroidism, both of which arise from inactivating mutations, as well as autosomal dominant hypocalcaemia, which arises from activating mutations (Brown and MacLeod, 2001). In addition, more severe activating mutations of the CaSR induce the salt-wasting disorder Bartter syndrome type V (Watanabe et al., 2002). These disorders result from mutation-specific impairments in receptor function, which include deficiencies in signalling capacity, trafficking to the cell surface and/or dimerization (Pidasheva et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2012; Leach et al., 2012).

Other disorders that have been linked to CaSR mutations and/or SNPs include some forms of nephrolithiasis (Vezzoli et al., 2012), idiopathic epilepsy (Kapoor et al., 2008), Alzheimer's disease (Conley et al., 2009), chronic pancreatitis (Muddana et al., 2008), coronary heart disease and myocardial infarction (Marz et al., 2007), prostate cancer (Shui et al., 2013) and rectal cancer (Speer et al., 2002).

The majority of mutations that cause loss or gain in CaSR function and/or expression encode amino acid substitutions affecting the receptor's 19 residue signal peptide, its N-terminus, heptahelical domains and C-terminal tail (http://www.casrdb.mcgill.ca). Frameshift mutations (e.g. Ma et al., 2008) or nonsense mutations that introduce premature stop codons and thereby truncate the receptor protein (e.g. Rodrigues et al., 2011; Ward et al., 2013) also induce loss of function and/or expression. Receptor truncation can also arise from mutations in acceptor splice sites (D'Souza-Li et al., 2001) or from the insertion of Alu elements (Janicic et al., 1995). The incidence of mutations in untranslated regions of the CaSR gene and their significance for disorders of calcium homeostasis are currently unknown.

Mutations that result in amino acid substitutions in the CaSR protein cause a range of functional outcomes, most commonly altering the signalling capacity of the receptor and/or reducing receptor expression. In fact, many ‘loss-of-function’ CaSR mutations cause reductions in cell surface expression, which limit signalling output in response to ligands (Leach et al., 2012). As noted earlier, a reduction in CaSR expression has also been reported in the context of colonic tumourigenesis (Hizaki et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2012) and is a prominent feature of primary (Kifor et al., 1996; Cetani et al., 2000) and secondary (Kifor et al., 1996; Gogusev et al., 1997; Chikatsu et al., 2000; Yano et al., 2000) hyperparathyroidism. In these disease states, reduced CaSR expression is correlated with increased cell proliferation and decreased differentiation. Intriguingly, in rats treated with streptozotocin, which induces type I diabetes by destroying pancreatic islet beta-cells, CaSR expression was reduced in cardiomyocytes (Bai et al., 2012), and up-regulated in the pancreas, liver and kidney (Haligur et al., 2012). Thus, aberrant CaSR expression is a hallmark of various proliferative and metabolic disorders.

Engendering biased signalling at the CaSR

Given that endogenous ligands promote biased signalling at the CaSR, it is possible that synthetic drugs that bias CaSR signalling towards a particular ‘signature’ cluster of pathways to the exclusion of others will provide unique treatment opportunities for specific CaSR-mediated disorders. Likely design characteristics will be discussed in the following sections.

At present, strontium ranelate and cinacalcet are the only drugs in clinical practice that target the CaSR. Strontium ions are presumed to bind, like Ca2+o, in the VFT domain, thereby stimulating receptor signalling in osteoblasts and osteoclasts. In osteoblasts, Sr2+ stimulates the expression of genes that promote cell proliferation and differentiation and down-regulates expression of the pro-osteoclastogenic signal TNFSF11 (RANKL) and up-regulates expression of its decoy receptor osteoprotegerin (Brennan et al., 2009; for a review, see Saidak and Marie, 2012). The outcome is reduced bone resorption together with enhanced bone formation. These effects appear to be primary contributors to the therapeutic efficacy of strontium ranelate in osteoporosis.

Cinacalcet, in contrast, binds in the receptor's heptahelical domain and acts as a positive allosteric modulator. Therapeutically, cinacalcet enhances Ca2+o-mediated receptor activation, which results in normalization of PTH levels in hyperparathyroidism via enhanced inhibition of PTH secretion from the parathyroid glands. Cinacalcet has also been used successfully to correct serum Ca2+o concentrations in patients possessing loss-of-function CaSR mutations by lowering the Ca2+o set point in the parathyroid to normal levels (Timmers et al., 2006; Reh et al., 2011; Wilhelm-Bals et al., 2012). Furthermore, we and others have shown that phenylalkylamine calcimimetics such as cinacalcet are efficient pharmacochaperones that promote trafficking of loss-of-expression CaSR mutants to the cell surface (White et al., 2009; Leach et al., 2013), indicating that allosteric modulators could be used to regulate CaSR expression levels in diseases where its expression is attenuated. However, cinacalcet and other early generation phenylalkylamines frequently cause hypocalcaemia (Chonchol et al., 2009). Thus, its use is currently limited to patients with hyperparathyroidism in the context of end-stage kidney disease, parathyroid cancer or patients with moderate–severe primary hyperparathyroidism who cannot undergo parathyroidectomy. Cinacalcet causes a transient increase in the serum calcitonin level in both haemodialysis patients and in patients that have undergone renal transplantation (Serra et al., 2008; Arenas et al., 2013). Following cinacalcet administration, the serum calcitonin level peaks after 2–3 h and normalizes after 6–12 h and may thus exacerbate the hypocalcaemic effect of calcimimetics. Calcitonin inhibits bone resorption (Hosking et al., 1981) and has traditionally been thought to decrease renal Ca2+ re-absorption (Haas et al., 1971), thus lowering the serum Ca2+o concentration. Although recent work suggests that calcitonin may, in fact, stimulate renal Ca2+ re-absorption (Hsu et al., 2010), suggesting calcitonin acts to redirect Ca2+ from urine to bone rather than directly lowering serum Ca2+ through enhanced secretion. Drugs that bias CaSR activity towards signalling pathways, which selectively suppress PTH secretion to the exclusion of others that promote calcitonin release, may reduce the incidence of symptomatic hypocalcaemic episodes. Proximal signalling events that link CaSR to the inhibition of PTH release and activation of calcitonin release have been identified (Figure 1) and will be described later.

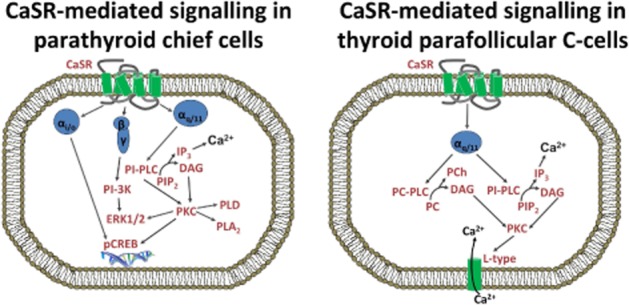

Figure 1.

CaSR-mediated regulation of PTH and calcitonin release. Suppression of PTH release from parathyroid chief cells is dependent on CaSR activation of Gq/11-mediated pathways and possibly the suppression of cAMP synthesis (not shown). CaSR activation of PI-PLC and phosphorylation of ERK1/2 leads to changes in the immediate secretion of PTH. CaSR activity has additionally been linked to changes in PTH gene transcription and subsequent PTH synthesis. Calcitonin release from parafollicular C-cells of the thyroid gland has been linked to Gq/11-mediated stimulation of PI-PLC, PC-PLC and the opening of L-type Ca2+ channels but calcitonin release is independent of ERK1/2 signalling and inhibition of cAMP. PIP2, phospholipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate.

Desired properties of CaSR modulators that selectively target PTH release

PTH secretion is promoted by GPCR-mediated stimulation of AC (for a review, see Brown and MacLeod, 2001). Elevated Ca2+o suppresses the release of PTH from prepackaged vesicles and enhances PTH degradation in parathyroid cells (Habener et al., 1975), and these effects are likely mediated by the CaSR. Activation of the CaSR by elevated Ca2+o suppresses AC activity and subsequent intracellular cAMP levels, for example, in dopamine-stimulated bovine parathyroid cells (Chen et al., 1989). However, although overnight exposure to pertussis toxin attenuates CaSR-mediated suppression of cAMP levels demonstrating a role for Gi/o in the mechanism, Gi/o is not required for Ca2+o-dependent suppression of PTH secretion (Brown et al., 1992; for a review, see Brown and MacLeod, 2001), pointing to the existence of key roles for other G-proteins in PTH secretion control. Consistent with this, mice, in which Gαq was selectively deleted in parathyroid cells on a global Gα11 null background, exhibited a phenotype that closely resembled that described for CaSR exon-5 null mice (Ho et al., 1995), including growth retardation, parathyroid gland hyperplasia, hyperparathyroidism and severe hypercalcaemia (Wettschureck et al., 2007). The first CaSR knockout strategy described employed a deletion of 20 bps in exon 5, which encodes residues 460–536 in the N-terminal extracellular domain, rendering the succeeding sequence out of frame (Ho et al., 1995). It is now known that an exon 5-less CaSR splice variant is expressed and functional in several tissues including keratinocytes (Oda et al., 1998) and fetal lung (Finney et al., 2011). More recently, tissue-specific deletion of CaSR exon 7 has revealed more severe phenotypes including developmental disturbances of cartilage and bone (Chang et al., 2008). CaSR-mediated suppression of PTH release via Gq/11 has been linked to activation of phosphatidylinositol-specific PLC (PI-PLC) resulting in the release of IP3 and DAG with consequent elevation of Ca2+i and activation of PKC (Corbetta et al., 2002). PKC stimulates ERK1/2 phosphorylation and inhibition of either PKC or ERK1/2 signalling abolished the inhibitory effect of Ca2+o on PTH release (Corbetta et al., 2002). PKC additionally activates PLD and PLA2 (Kifor et al., 1997). CaSR-mediated PI 3-kinase activity also appears to contribute to the inhibitory control of PTH secretion (Corbetta et al., 2002). Although it seems paradoxical that CaSR-mediated activation of pathways that lead to increased Ca2+i should suppress PTH secretion rather than activate it, as observed for other hormones that are released via exocytosis (Gustavsson et al., 2012), it is possible that Gq/11 contributes to CaSR-mediated suppression of intracellular cAMP levels via Ca2+i-inihibited isoforms of AC (5, 6 or 9) as described for CaSR-expressing HEK-293 cells (Gerbino et al., 2005) and renin-secreting renal juxtaglomerular cells (Atchison and Beierwaltes, 2013).

Both Gi/o and Gq/11 have been implicated in the control of gene expression that modulates PTH production (Thiel et al., 2012; Avlani et al., 2013) and release of Ca2+i has been linked to changes in PTH gene transcription (Ritter et al., 2008).

CaSR-mediated release of calcitonin from thyroid parafollicular C-cells has also been linked to PLC-dependent signalling and appears to occur independently of the activation of ERK1/2 signalling and suppression of cAMP synthesis (Thomsen et al., 2012b). However, the signalling mechanisms that couple CaSR activation to calcitonin release appear to be different in various cell models pointing to the need for a more robust human C-cell model. Thus, in sheep C-cells in primary culture, the CaSR was reported to signal via a pathway dependent on Gβγ-mediated stimulation of PI 3-kinase followed by the activation of PKCζ and PLC (McGehee et al., 1997; Liu et al., 2003). However, in cultured rat 6–23 medullary thyroid carcinoma cells, PI 3-kinase was not required for Ca2+o-stimulated calcitonin secretion. Instead, it was driven by phosphatidylcholine-specific PLC (PC-PLC) as well as PI-PLC-dependent signalling pathways coupled to Ca2+i mobilization (Thomsen et al., 2012b). Ca2+o-induced elevations in Ca2+i were mediated by L-type Ca2+ channels activated downstream of PC-PLC.

Interestingly, unlike Ca2+o, calcitonin secretion induced by the closely related alkaline earth metal Sr2+o was driven solely by PI-PLC, and Sr2+o-mediated elevations of Ca2+i did not require L-type Ca2+ channels (Thomsen et al., 2012b). The observed differences in CaSR-mediated signalling and calcitonin release in response to Ca2+o versus Sr2+o point to the existence of distinct classes of divalent cation binding sites linked to the activation of discrete signalling mechanisms. In keeping with this notion, distinct Ca2+o binding sites have been described in the CaSR VFT domain (Huang et al., 2009) as well as the HH domain (Ray and Northup, 2002; Mun et al., 2004). In addition, a binding site for the tervalent cation Gd3+ has been identified at the dimeric interface of neighbouring VFT domains in the crystal structure of the rat type-1 metabotropic glutamate receptor, a CaSR homologue (Tsuchiya et al., 2002).

Thus, CaSR-acting drugs that selectively promote Gq/11-dependent activation of PI-PLC and ERK1/2 and, perhaps, promote the inhibition of cAMP formation (Chen et al., 1989) may suppress PTH secretion without disturbing calcitonin secretion. Since the development of cinacalcet and related calcimimetics, several classes of novel positive allosteric CaSR modulators have been identified (Harrington et al., 2010; Kiefer et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2011; Deprez et al., 2013). Of these compounds, calcimimetic B (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA), when compared with NPS R568, has reduced potency for the promotion of calcitonin release relative to its ability to inhibit PTH secretion in rats. In addition, in human TT medullary thyroid carcinoma C-cells, calcimimetic B exhibits reduced ability to stimulate calcitonin secretion when compared with the first generation phenylalkylamine, NPS R568 (Henley et al., 2011). If these differences in selectivity are retained in vivo in treated patients, calcimimetic B or a related compound with reduced propensity to stimulate calcitonin release might reduce the frequency and/or severity of hypocalcaemic episodes.

Biased drugs that correct defective signalling engendered by naturally occurring mutations

Although CaSR mutations have traditionally been classified as ‘loss-’ or ‘gain-of-function’, their effects are not transmitted equally across all pathways. Some CaSR mutations differentially alter receptor signalling, resulting in a change in coupling preference (Leach et al., 2012). Thus, naturally occurring mutations engender CaSR signalling bias. This has implications for the treatment of patients harbouring such mutations. For instance, when overexpressed in HEK293 cells, the wild-type (WT) CaSR couples preferentially to Ca2+i mobilization over ERK1/2 phosphorylation, highlighted by a higher Ca2+o potency for Ca2+i mobilization (Davey et al., 2012; Leach et al., 2012). In addition, we identified three naturally occurring mutations in which this coupling preference was lost, that is, both pathways were equally sensitive to Ca2+o (Leach et al., 2012) (Figure 3). Thus, a drug that preferentially enhanced CaSR signalling via Ca2+i mobilization could be used to restore the natural signalling bias.

Type-II calcimimetics (positive modulators), including cinacalcet and NPS R568 (Nemeth et al., 1998), and the calcilytic, NPS 2143 (Nemeth, 2002), also engender biased signalling at the CaSR. These small-molecule drugs manifest greater allosteric modulation of Ca2+i mobilization relative to ERK1/2 phosphorylation and possess higher potency and estimated affinity for receptor states that mediate plasma membrane ruffling relative to either of the other two pathways investigated (Davey et al., 2012; Leach et al., 2013). Thus, for mutants whose coupling to Ca2+i mobilization is compromised, cinacalcet corrects their signalling bias towards the coupling preference of the WT receptor.

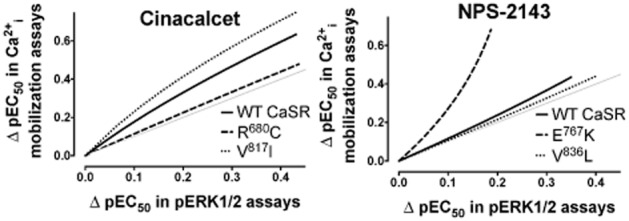

Interestingly, some naturally occurring mutations of the CaSR alter the stimulus bias engendered by allosteric modulators. Positive allosteric modulation of the CaSR mutant R680C by cinacalcet, for example, is approximately equal in both Ca2+i mobilization and ERK1/2 phosphorylation assays. In the case of the CaSR mutant, V817I, however, cinacalcet exhibits a bias towards Ca2+i mobilization that is greater than that observed for the WT CaSR (Leach et al., 2013).

Compared with WT, where NPS 2143 negatively modulates the potency of Ca2+o approximately 1.3-fold more in Ca2+i mobilization assays than in ERK1/2 phosphorylation assays, negative modulation by NPS 2143 of the mutant E767K was approximately fourfold greater for Ca2+i mobilization. However, in the case of V836L, little difference was observed between the modulation of either pathway (Leach et al., 2013). These changes can be visualized on a ‘bias plot’ that depicts the relationship between changes in agonist potency in two dimensions (corresponding to two distinct receptor-dependent signalling pathways) in the presence of equimolar concentrations of modulator (Figure 4). For instance, the bias plots shown in Figure 4 depict the change in Ca2+o potency in the presence of equimolar concentrations of allosteric modulator measured in Ca2+i mobilization assays (y axis) and ERK1/2 phosphorylation assays (x axis). If the allosteric modulator exerts greater cooperativity on one pathway, the points fall on the corresponding side of the line of identity.

Figure 4.

Allosteric stimulus bias is altered by naturally occurring CaSR mutations. Cooperativity bias plots highlight that allosteric compounds show bias in their modulation of Ca2+i mobilization and ERK1/2 phosphorylation, but that certain mutations alter this bias. The pEC50 of Ca2+o in the absence and presence of modulator in Ca2+i mobilization and ERK1/2 phosphorylation assays was first fitted to an allosteric ternary complex model and 150 XY coordinates of points that defined the curve that best fit the equation were determined. Next, the XY coordinates for the two pathways were plotted against one another, with Ca2+i mobilization data on the y axis against ERK1/2 phosphorylation data on the x axis. These plots thus represent the change (Δ) in Ca2+o pEC50 in the presence of equimolar concentrations of allosteric modulator across the two pathways.

An understanding of how naturally occurring mutations alter the pharmacoregulation of the CaSR protein may permit predictions of the clinical responses to specific drug treatments in different tissues. Consistent with this idea, a small study in patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism in the context of end-stage renal failure reported that cinacalcet-mediated suppression of PTH was markedly enhanced in a patient homozygous for the polymorphism R990G (Rothe et al., 2005).

Drugs that bias trafficking versus signalling

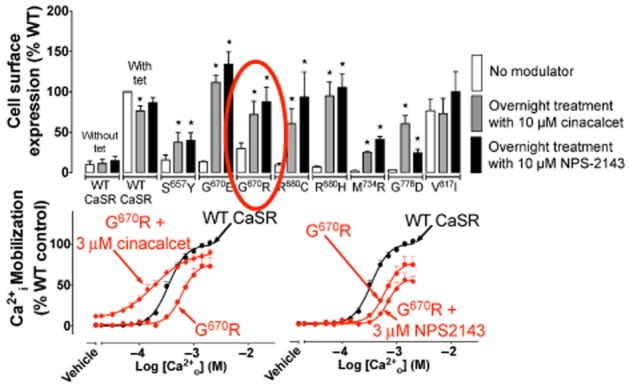

As noted earlier, various CaSR mutations reduce cell surface expression (Leach et al., 2012), and the expression of some of these mutants is rescued by cinacalcet and related calcimimetics (White et al., 2009; Leach et al., 2013). However, due to the positive modulation of CaSR signalling, CaSR activity is also significantly enhanced in response to calcimimetics and can readily exceed that of the WT CaSR (Figure 5). Therefore, drug-induced increases in the cell surface expression and signalling of mutant receptors may drive a gain-of-function phenotype with enhanced sensitivity to Ca2+o and attendant hypocalcaemia. An ideal drug in this instance would positively modulate cell surface expression of the mutant receptor but have neutral cooperativity on signalling responses. The CaSR is localized to both the cell membrane and to intracellular compartments in recombinant and native CaSR-expressing cells (Rodriguez et al., 2005; Pidasheva et al., 2006; Bonomini et al., 2012). CaSR agonists and positive allosteric modulators promote the forward trafficking and attendant glycosylation of intracellular receptors to the plasma membrane (McCormick et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2011), a phenomenon that has been termed agonist-driven insertional signalling (ADIS). This is directly linked to membrane-localized receptor signalling events, as evidenced by attenuation of ADIS by inactivating CaSR mutations (Grant et al., 2011; 2012). Strikingly, however, the small-molecule negative modulator (calcilytic) NPS 2143 also rescued cell surface expression of loss-of-expression mutants in HEK293 cells (Leach et al., 2013). This is a remarkable example of biased allosteric modulation, with a complete reversal in cooperativity (positive vs. negative) between pathways (trafficking vs. acute signalling). Thus, NPS 2143 negatively modulates CaSR-mediated signalling and positively modulates receptor trafficking to the cell surface.

Figure 5.

Stimulus bias engendered by NPS 2143. Both cinacalcet and NPS 2143 modulate trafficking of loss-of-expression mutant CaSRs to the cell surface, but whereas cinacalcet is a positive modulator of CaSR signalling, NPS 2143 is a negative allosteric modulator of signalling. For mutants such as G670R, positive modulation of trafficking and signalling may lead to overstimulation of the receptor, whereas NPS 2143 may be more appropriate for balancing expression versus signalling. *Significantly different from value obtained in the absence of modulator (no modulator), one-way ANOVA.

The use of allosteric modulators of the CaSR that bias receptor trafficking to the exclusion of signalling may be extended to disease states in which aberrant CaSR expression contributes to the pathogenesis. Thus, up-regulated CaSR expression upon exposure to calcimimetics may provide an effective approach to the prevention and/or treatment of colon cancer.

However, positive modulation of CaSR signalling in other cell types in the gastrointestinal tract may induce unwanted side effects, for example, arising from enhanced release of gut hormones including gastrin and CCK (Buchan et al., 2001; Liou et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011). For example, oral administration of the calcimimetic KRN568 (NPS R568) caused gastrin release in human subjects (Igarashi et al., 2000). Interestingly, Ca2+o-induced gastrin secretion from human G-cells occurs independently of cAMP inhibition, ERK1/2 or PLA2 signalling (Buchan et al., 2001), so that a CaSR-acting agent that promotes CaSR trafficking and selectively modulates signalling towards ERK1/2 may be effective in the treatment of colon cancer and exhibit a favourable side effect profile. Alternatively, a positive modulator of trafficking with neutral effects on receptor signalling that possesses a rapid receptor off rate might be ideal for mediating the cell surface chaperoning effect while minimizing interference with receptor activation once at the plasma membrane.

Some proof of concept for targeting CaSR expression has been provided by treatment of nephrectomized rats (an animal model of secondary hyperparathyroidism) with the novel calcimimetic, AMG641, which up-regulates parathyroid CaSR protein and mRNA expression and inhibits parathyroid gland hyperplasia (Mendoza et al., 2009). Furthermore, attenuation of CaSR expression has been linked to calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells (Alam et al., 2009) and expression is increased in the aortic intima of uraemic rats treated with the calcimimetic, NPS-R568. These rats show diminished calcification and reduced proliferation of vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells in comparison with vehicle-treated controls (Koleganova et al., 2009). These examples provide direct evidence that up-regulation of CaSR expression may be effective in treating certain disease states.

Summary

The CaSR is expressed widely in tissues throughout the body where it serves a multitude of functions through selective activation of distinct signalling pathways in response to diverse ligands. We now know that endogenous orthosteric and allosteric ligands as well as synthetic small-molecule allosteric drugs engender significant stimulus bias and provide the theoretical basis for the development of novel, highly selective therapeutics. Thus, drugs that activate a discrete ‘signature’ subset of receptor-mediated signalling pathways may be useful in the treatment of disorders such as osteoporosis, in which the selective recruitment and/or activation of osteoblasts would be beneficial. However, drugs that selectively promote receptor expression without disturbing the balance of downstream signalling pathways may be beneficial in disease states arising from defective CaSR expression (e.g. primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism, colon cancer and some forms of cardiovascular disease). Profiling of candidate calcimimetics, calcilytics and neutral modulators that up- or down-regulate CaSR expression across multiple signalling pathways will identify drugs that selectively promote CaSR trafficking and/or signalling and may provide new therapeutic options for various disorders.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia project grant number APP1026962 and NHMRC program grant number 519461. A. C. and P. M. S. are Principal Research Fellows of the NHMRC.

Glossary

- ADIS

agonist-driven insertional signalling

- CaSR

calcium-sensing receptor

- CCK

cholecystokinin

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide 1

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- L-Phe

L-phenylalanine

- PC-PLC

phosphatidylcholine-specific PLC

- PI 3-kinase

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PI-PLC

phosphatidylinositol-specific PLC

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- RANKL/TNFSF11

receptor activator of NFκB ligand

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- TRPC

transient receptor potential cation

Conflict of interest

KL, PMS and ADC have nothing to declare. AC has previously published work on the CaSR in collaboration with researchers from Amgen.

References

- Alam MU, Kirton JP, Wilkinson FL, Towers E, Sinha S, Rouhi M, et al. Calcification is associated with loss of functional calcium-sensing receptor in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:260–268. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Catterall WA, Spedding M, Peters JA, Harmar AJ CGTP Collaborators. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1459–1581. doi: 10.1111/bph.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas MD, de la Fuente V, Delgado P, Gil MT, Gutierrez P, Ribero J, et al. Pharmacodynamics of cinacalcet over 48 hours in patients with controlled secondary hyperparathyroidism: useful data in clinical practice. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:1718–1725. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchison DK, Beierwaltes WH. The influence of extracellular and intracellular calcium on the secretion of renin. Pflugers Arch. 2013;465:59–69. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1107-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avlani VA, Ma W, Mun HC, Leach K, Delbridge L, Christopoulos A, et al. Calcium-sensing receptor-dependent activation of CREB phosphorylation in HEK-293 cells and human parathyroid cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E1097–E1104. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00054.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai M, Trivedi S, Lane CR, Yang Y, Quinn SJ, Brown EM. Protein kinase C phosphorylation of threonine at position 888 in Ca2+o-sensing receptor (CaR) inhibits coupling to Ca2+ store release. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21267–21275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai SZ, Sun J, Wu H, Zhang N, Li HX, Li GW, et al. Decrease in calcium-sensing receptor in the progress of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;95:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagavathula N, Kelley EA, Reddy M, Nerusu KC, Leonard C, Fay K, et al. Upregulation of calcium-sensing receptor and mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling in the regulation of growth and differentiation in colon carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1364–1371. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikle DD, Xie Z, Tu CL. Calcium regulation of keratinocyte differentiation. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2012;7:461–472. doi: 10.1586/eem.12.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomini M, Giardinelli A, Morabito C, Di Silvestre S, Di Cesare M, Di Pietro N, et al. Calcimimetic R-568 and its enantiomer S-568 increase nitric oxide release in human endothelial cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan SC, Thiem U, Roth S, Aggarwal A, Fetahu IS, Tennakoon S, et al. Calcium sensing receptor signalling in physiology and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1833:1732–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan TC, Rybchyn MS, Green W, Atwa S, Conigrave AD, Mason RS. Osteoblasts play key roles in the mechanisms of action of strontium ranelate. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:1291–1300. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EM, MacLeod RJ. Extracellular calcium sensing and extracellular calcium signaling. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:239–297. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EM, Butters R, Katz C, Kifor O, Fuleihan GE. A comparison of the effects of concanavalin-A and tetradecanoylphorbol acetate on the modulation of parathyroid function by extracellular calcium and neomycin in dispersed bovine parathyroid cells. Endocrinology. 1992;130:3143–3151. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.6.1317777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan AM, Squires PE, Ring M, Meloche RM. Mechanism of action of the calcium-sensing receptor in human antral gastrin cells. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1128–1139. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canaff L, Petit JL, Kisiel M, Watson PH, Gascon-Barre M, Hendy GN. Extracellular calcium-sensing receptor is expressed in rat hepatocytes. Coupling to intracellular calcium mobilization and stimulation of bile flow. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4070–4079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetani F, Picone A, Cerrai P, Vignali E, Borsari S, Pardi E, et al. Parathyroid expression of calcium-sensing receptor protein and in vivo parathyroid hormone-Ca(2+) set-point in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4789–4794. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha SK, Huang C, Ding Y, Qi X, Huang CL, Miller RT. Calcium-sensing receptor decreases cell surface expression of the inwardly rectifying K+ channel Kir4.1. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1828–1835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty S, Wang H, Canaff L, Hendy GN, Appelman H, Varani J. Calcium sensing receptor in human colon carcinoma: interaction with Ca(2+) and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) Cancer Res. 2005;65:493–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W, Tu C, Chen TH, Bikle D, Shoback D. The extracellular calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) is a critical modulator of skeletal development. Sci Signal. 2008;1:ra1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1159945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay N, Espinosa-Jeffrey A, Tfelt-Hansen J, Yano S, Bandyopadhyay S, Brown EM, et al. Calcium receptor expression and function in oligodendrocyte commitment and lineage progression: potential impact on reduced myelin basic protein in CaR-null mice. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:2159–2167. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CJ, Barnett JV, Congo DA, Brown EM. Divalent cations suppress 3′,5′-adenosine monophosphate accumulation by stimulating a pertussis toxin-sensitive guanine nucleotide-binding protein in cultured bovine parathyroid cells. Endocrinology. 1989;124:233–239. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-1-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng I, Klingensmith ME, Chattopadhyay N, Kifor O, Butters RR, Soybel DI, et al. Identification and localization of the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor in human breast. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:703–707. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.2.4558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikatsu N, Fukumoto S, Takeuchi Y, Suzawa M, Obara T, Matsumoto T, et al. Cloning and characterization of two promoters for the human calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) and changes of CaSR expression in parathyroid adenomas. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7553–7557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chonchol M, Locatelli F, Abboud HE, Charytan C, de Francisco AL, Jolly S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and safety of cinacalcet HCl in participants with CKD not receiving dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:197–207. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes M, Rojas CV. Antilipolytic effect of calcium-sensing receptor in human adipocytes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;319:17–21. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9872-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes M, Fuentes C, Mattar P, Tobar N, Hugo E, Ben-Jonathan N, et al. Obesity-associated proinflammatory cytokines increase calcium sensing receptor (CaSR) protein expression in primary human adipocytes and LS14 human adipose cell line. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;500:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes M, Fuentes C, Tobar N, Acevedo I, Villalobos E, Hugo E, et al. Calcium sensing receptor activation elevates proinflammatory factor expression in human adipose cells and adipose tissue. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;361:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conigrave AD, Brown EM. Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. II. L-amino acid sensing by calcium-sensing receptors: implications for GI physiology. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G753–G761. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00189.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conigrave AD, Hampson DR. Broad-spectrum amino acid-sensing class C G-protein coupled receptors: molecular mechanisms, physiological significance and options for drug development. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;127:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley YP, Mukherjee A, Kammerer C, DeKosky ST, Kamboh MI, Finegold DN, et al. Evidence supporting a role for the calcium-sensing receptor in Alzheimer disease. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:703–709. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta S, Lania A, Filopanti M, Vicentini L, Ballare E, Spada A. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in human normal and tumoral parathyroid cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2201–2205. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza-Li L, Canaff L, Janicic N, Cole DE, Hendy GN. An acceptor splice site mutation in the calcium-sensing receptor (CASR) gene in familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia and neonatal severe hyperparathyroidism. Hum Mutat. 2001;18:411–421. doi: 10.1002/humu.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey AE, Leach K, Valant C, Conigrave AD, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. Positive and negative allosteric modulators promote biased signaling at the calcium-sensing receptor. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1232–1241. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SL, Ozawa A, McCormick WD, Dvorak MM, Ward DT. Protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation of the calcium-sensing receptor is stimulated by receptor activation and attenuated by calyculin-sensitive phosphatase activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15048–15056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprez P, Temal T, Jary H, Auberval M, Lively S, Guedin D, et al. New potent calcimietics: II. Discovery of benzothiazole trisubstituted ureas. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:2455–2459. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak-Ewell MM, Chen TH, Liang N, Garvey C, Liu B, Tu C, et al. Osteoblast extracellular Ca2+ -sensing receptor regulates bone development, mineralization, and turnover. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2935–2947. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Petersen CD, Coy DH, Jiang JK, Thomas CJ, Pollak MR, et al. Calcium-sensing receptor is a physiologic multimodal chemosensor regulating gastric G-cell growth and gastrin secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17791–17796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009078107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry S, Traiffort E, Stinnakre J, Ruat M. Developmental and adult expression of rat calcium-sensing receptor transcripts in neurons and oligodendrocytes. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:872–884. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney B, Wilkinson WJ, Searchfield L, Cole M, Bailey S, Kemp PJ, et al. An exon 5-less splice variant of the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor rescues absence of the full-length receptor in the developing mouse lung. Exp Lung Res. 2011;37:269–278. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2010.545471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamba G, Friedman PA. Thick ascending limb: the Na(+):K (+):2Cl (-) co-transporter, NKCC2, and the calcium-sensing receptor, CaSR. Pflugers Arch. 2009;458:61–76. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0607-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geibel JP, Hebert SC. The functions and roles of the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor along the gastrointestinal tract. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:205–217. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbino A, Ruder WC, Curci S, Pozzan T, Zaccolo M, Hofer AM. Termination of cAMP signals by Ca2+ and G(alpha)i via extracellular Ca2+ sensors: a link to intracellular Ca2+ oscillations. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:303–312. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogusev J, Duchambon P, Hory B, Giovannini M, Goureau Y, Sarfati E, et al. Depressed expression of calcium receptor in parathyroid gland tissue of patients with hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int. 1997;51:328–336. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Renigunta V, Himmerkus N, Zhang J, Renigunta A, Bleich M, et al. Claudin-14 regulates renal Ca(+)(+) transport in response to CaSR signalling via a novel microRNA pathway. EMBO J. 2012;31:1999–2012. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MP, Stepanchick A, Cavanaugh A, Breitwieser GE. Agonist-driven maturation and plasma membrane insertion of calcium-sensing receptors dynamically control signal amplitude. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra78. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MP, Stepanchick A, Breitwieser GE. Calcium signaling regulates trafficking of familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (FHH) mutants of the calcium sensing receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:2081–2091. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray E, Muller D, Squires PE, Asare-Anane H, Huang GC, Amiel S, et al. Activation of the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor initiates insulin secretion from human islets of Langerhans: involvement of protein kinases. J Endocrinol. 2006;190:703–710. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson N, Wu B, Han W. Calcium sensing in exocytosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;740:731–757. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2888-2_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas HG, Dambacher MA, Guncaga J, Lauffenbruger T. Renal effects of calcitonin and parathyroid extract in man. Studies in hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Invest. 1971;50:2689–2702. doi: 10.1172/JCI106770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habener JF, Kemper B, Potts JT., Jr Calcium-dependent intracellular degradation of parathyroid hormone: a possible mechanism for the regulation of hormone stores. Endocrinology. 1975;97:431–441. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-2-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haligur M, Topsakal S, Ozmen O. Early degenerative effects of diabetes mellitus on pancreas, liver, and kidney in rats: an immunohistochemical study. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/120645. DOI: 10.1155/2012/120645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handlogten ME, Shiraishi N, Awata H, Huang C, Miller RT. Extracellular Ca(2+)-sensing receptor is a promiscuous divalent cation sensor that responds to lead. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F1083–F1091. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.6.F1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington PE, St Jean DJ, Jr, Clarine J, Coulter TS, Croghan M, Davenport A, et al. The discovery of an orally efficacious positive allosteric modulator of the calcium sensing receptor containing a dibenzylamine core. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:5544–5547. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YH, Song Y, Liao XL, Wang L, Li G, Alima, Li Y, et al. The calcium-sensing receptor affects fat accumulation via effects on antilipolytic pathways in adipose tissue of rats fed low-calcium diets. J Nutr. 2011;141:1938–1946. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.141762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YH, He Y, Liao XL, Niu YC, Wang G, Zhao C, et al. The calcium-sensing receptor promotes adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis through PPARgamma pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;361:321–328. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henley C, 3rd, Yang Y, Davis J, Lu JY, Morony S, Fan W, et al. Discovery of a calcimimetic with differential effects on parathyroid hormone and calcitonin secretion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;337:681–691. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.178681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hizaki K, Yamamoto H, Taniguchi H, Adachi Y, Nakazawa M, Tanuma T, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of calcium-sensing receptor in colorectal carcinogenesis. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:876–884. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C, Conner DA, Pollak MR, Ladd DJ, Kifor O, Warren HB, et al. A mouse model of human familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia and neonatal severe hyperparathyroidism. Nat Genet. 1995;11:389–394. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking DJ, Cowley A, Bucknall CA. Rehydration in the treatment of severe hypercalcaemia. Q J Med. 1981;50:473–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu YJ, Dimke H, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Calcitonin-stimulated renal Ca2+ reabsorption occurs independently of TRPV5. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:1428–1435. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Hujer KM, Wu Z, Miller RT. The Ca2+-sensing receptor couples to Galpha12/13 to activate phospholipase D in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C22–C30. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00229.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Sindic A, Hill CE, Hujer KM, Chan KW, Sassen M, et al. Interaction of the Ca2+-sensing receptor with the inwardly rectifying potassium channels Kir4.1 and Kir4.2 results in inhibition of channel function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F1073–F1081. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00269.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Zhou Y, Castiblanco A, Yang W, Brown EM, Yang JJ. Multiple Ca(2+)-binding sites in the extracellular domain of the Ca(2+)-sensing receptor corresponding to cooperative Ca(2+) response. Biochemistry. 2009;48:388–398. doi: 10.1021/bi8014604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi T, Ogata E, Maruyama K, Fukuda T. Effect of calcimimetic agent, KRN568, on gastrin secretion in healthy subjects. Endocr J. 2000;47:517–523. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.47.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicic N, Pausova Z, Cole DE, Hendy GN. Insertion of an Alu sequence in the Ca(2+)-sensing receptor gene in familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia and neonatal severe hyperparathyroidism. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:880–886. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jesus Ferreira MC, Helies-Toussaint C, Imbert-Teboul M, Bailly C, Verbavatz JM, Bellanger AC, et al. Co-expression of a Ca2+-inhibitable adenylyl cyclase and of a Ca2+-sensing receptor in the cortical thick ascending limb cell of the rat kidney. Inhibition of hormone-dependent cAMP accumulation by extracellular Ca2+ J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15192–15202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallay E, Bonner E, Wrba F, Thakker RV, Peterlik M, Cross HS. Molecular and functional characterization of the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor in human colon cancer cells. Oncol Res. 2003;13:551–559. doi: 10.3727/000000003108748072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatani M, Sugimoto T, Kanzawa M, Yano S, Chihara K. High extracellular calcium inhibits osteoclast-like cell formation by directly acting on the calcium-sensing receptor existing in osteoclast precursor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;261:144–148. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantham L, Quinn SJ, Egbuna OI, Baxi K, Butters R, Pang JL, et al. The calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) defends against hypercalcemia independently of its regulation of parathyroid hormone secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E915–E923. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00315.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor A, Satishchandra P, Ratnapriya R, Reddy R, Kadandale J, Shankar SK, et al. An idiopathic epilepsy syndrome linked to 3q13.3-q21 and missense mutations in the extracellular calcium sensing receptor gene. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:158–167. doi: 10.1002/ana.21428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. Functional selectivity and biased receptor signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:296–302. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.173948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer L, Gorojankina T, Dauban P, Faure H, Ruat M, Dodd RH. Design and synthesis of cyclic sulfonamides and sulfamates as new calcium sensing receptor agonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:7483–7487. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kifor O, Moore FD, Jr, Wang P, Goldstein M, Vassilev P, Kifor I, et al. Reduced immunostaining for the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor in primary and uremic secondary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:1598–1606. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.4.8636374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kifor O, Diaz R, Butters R, Brown EM. The Ca2+-sensing receptor (CaR) activates phospholipases C, A2, and D in bovine parathyroid and CaR-transfected, human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:715–725. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koleganova N, Piecha G, Ritz E, Schmitt CP, Gross ML. A calcimimetic (R-568), but not calcitriol, prevents vascular remodeling in uremia. Kidney Int. 2009;75:60–71. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs CS, Ho-Pao CL, Hunzelman JL, Lanske B, Fox J, Seidman JG, et al. Regulation of murine fetal-placental calcium metabolism by the calcium-sensing receptor. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2812–2820. doi: 10.1172/JCI2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach K, Wen A, Davey AE, Sexton PM, Conigrave AD, Christopoulos A. Identification of molecular phenotypes and biased signaling induced by naturally occurring mutations of the human calcium-sensing receptor. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4304–4316. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach K, Wen A, Cook AE, Sexton PM, Conigrave AD, Christopoulos A. Impact of clinically relevant mutations on the pharmacoregulation and signaling bias of the calcium-sensing receptor by positive and negative allosteric modulators. Endocrinology. 2013;154:1105–1116. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GS, Subramanian N, Kim AI, Aksentijevich I, Goldbach-Mansky R, Sacks DB, et al. The calcium-sensing receptor regulates the NLRP3 inflammasome through Ca2+ and cAMP. Nature. 2012;492:123–127. doi: 10.1038/nature11588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leech CA, Habener JF. Regulation of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor and calcium-sensing receptor signaling by L-histidine. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4851–4858. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou AP, Sei Y, Zhao X, Feng J, Lu X, Thomas C, et al. The extracellular calcium-sensing receptor is required for cholecystokinin secretion in response to L-phenylalanine in acutely isolated intestinal I cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G538–G546. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00342.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu KP, Russo AF, Hsiung SC, Adlersberg M, Franke TF, Gershon MD, et al. Calcium receptor-induced serotonin secretion by parafollicular cells: role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent signal transduction pathways. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2049–2057. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02049.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loupy A, Ramakrishnan SK, Wootla B, Chambrey R, de la Faille R, Bourgeois S, et al. PTH-independent regulation of blood calcium concentration by the calcium-sensing receptor. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3355–3367. doi: 10.1172/JCI57407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JN, Owens M, Gustafsson M, Jensen J, Tabatabaei A, Schmelzer K, et al. Characterization of highly efficacious allosteric agonists of the human calcium-sensing receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;337:275–284. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.178194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma RC, Lam CW, So WY, Tong PC, Cockram C, Chow CC. A novel CASR gene mutation in an octogenarian with asymptomatic hypercalcaemia. Hong Kong Med J. 2008;14:226–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick WD, Atkinson-Dell R, Campion KL, Mun HC, Conigrave AD, Ward DT. Increased receptor stimulation elicits differential calcium-sensing receptor(T888) dephosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14170–14177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.071084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Aldersberg M, Liu KP, Hsuing S, Heath MJ, Tamir H. Mechanism of extracellular Ca2+ receptor-stimulated hormone release from sheep thyroid parafollicular cells. J Physiol. 1997;502(Pt 1):31–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.031bl.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLarnon S, Holden D, Ward D, Jones M, Elliott A, Riccardi D. Aminoglycoside antibiotics induce pH-sensitive activation of the calcium-sensing receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:71–77. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace OJ, Schindler M, Patel S. The regulation of K- and L-cell activity by GLUT2 and the calcium-sensing receptor CasR in rat small intestine. J Physiol. 2012;590:2917–2936. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.223800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod RJ, Hayes M, Pacheco I. Wnt5a secretion stimulated by the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor inhibits defective Wnt signaling in colon cancer cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G403–G411. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00119.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamillapalli R, Wysolmerski J. The calcium-sensing receptor couples to Galpha(s) and regulates PTHrP and ACTH secretion in pituitary cells. J Endocrinol. 2010;204:287–297. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamillapalli R, Vanhouten J, Dann P, Bikle D, Chang W, Brown E, et al. Mammary-specific ablation of the calcium sensing receptor during lactation alters maternal calcium metabolism, milk calcium transport and neonatal calcium accrual. Endocrinology. 2013;154:3031–3042. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marz W, Seelhorst U, Wellnitz B, Tiran B, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Renner W, et al. Alanine to serine polymorphism at position 986 of the calcium-sensing receptor associated with coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, all-cause, and cardiovascular mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2363–2369. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza FJ, Lopez I, Canalejo R, Almaden Y, Martin D, Aguilera-Tejero E, et al. Direct upregulation of parathyroid calcium-sensing receptor and vitamin D receptor by calcimimetics in uremic rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F605–F613. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90272.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentaverri R, Yano S, Chattopadhyay N, Petit L, Kifor O, Kamel S, et al. The calcium sensing receptor is directly involved in both osteoclast differentiation and apoptosis. FASEB J. 2006;20:2562–2564. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6304fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muddana V, Lamb J, Greer JB, Elinoff B, Hawes RH, Cotton PB, et al. Association between calcium sensing receptor gene polymorphisms and chronic pancreatitis in a US population: role of serine protease inhibitor Kazal 1type and alcohol. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4486–4491. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun HC, Franks AH, Culverston EL, Krapcho K, Nemeth EF, Conigrave AD. The Venus Fly Trap domain of the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor is required for L-amino acid sensing. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51739–51744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406164/200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth EF. The search for calcium receptor antagonists (calcilytics) J Mol Endocrinol. 2002;29:15–21. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0290015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth EF, Steffey ME, Hammerland LG, Hung BC, Van Wagenen BC, DelMar EG, et al. Calcimimetics with potent and selective activity on the parathyroid calcium receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4040–4045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y, Tu CL, Pillai S, Bikle DD. The calcium sensing receptor and its alternatively spliced form in keratinocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23344–23352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszak IT, Poznansky MC, Evans RH, Olson D, Kos C, Pollak MR, et al. Extracellular calcium elicits a chemokinetic response from monocytes in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1299–1305. doi: 10.1172/JCI9799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkash J, Asotra K. L-histidine sensing by calcium sensing receptor inhibits voltage-dependent calcium channel activity and insulin secretion in beta-cells. Life Sci. 2011;88:440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterlik M, Kallay E, Cross HS. Calcium nutrition and extracellular calcium sensing: relevance for the pathogenesis of osteoporosis, cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Nutrients. 2013;5:302–327. doi: 10.3390/nu5010302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips CG, Harnett MT, Chen W, Smith SM. Calcium-sensing receptor activation depresses synaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12062–12070. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4134-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi M, Zhang L, Lei SF, Huang MZ, Zhu W, Zhang J, et al. Impaired osteoblast function in GPRC6A null mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1092–1102. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.091037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidasheva S, Grant M, Canaff L, Ercan O, Kumar U, Hendy GN. Calcium-sensing receptor dimerizes in the endoplasmic reticulum: biochemical and biophysical characterization of CASR mutants retained intracellularly. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2200–2209. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn SJ, Ye CP, Diaz R, Kifor O, Bai M, Vassilev P, et al. The Ca2+-sensing receptor: a target for polyamines. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1315–C1323. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray K, Northup J. Evidence for distinct cation and calcimimetic compound (NPS 568) recognition domains in the transmembrane regions of the human Ca2+ receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18908–18913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray K, Tisdale J, Dodd RH, Dauban P, Ruat M, Northup JK. Calindol, a positive allosteric modulator of the human Ca(2+) receptor, activates an extracellular ligand-binding domain-deleted rhodopsin-like seven-transmembrane structure in the absence of Ca(2+) J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37013–37020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reh CM, Hendy GN, Cole DE, Jeandron DD. Neonatal hyperparathyroidism with a heterozygous calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) R185Q mutation: clinical benefit from cinacalcet. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E707–E712. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey O, Young SH, Yuan J, Slice L, Rozengurt E. Amino acid-stimulated Ca2+ oscillations produced by the Ca2+-sensing receptor are mediated by a phospholipase C/inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-independent pathway that requires G12, Rho, filamin-A, and the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22875–22882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503455200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey O, Young SH, Papazyan R, Shapiro MS, Rozengurt E. Requirement of the TRPC1 cation channel in the generation of transient Ca2+ oscillations by the calcium-sensing receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38730–38737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605956200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey O, Young SH, Jacamo R, Moyer MP, Rozengurt E. Extracellular calcium sensing receptor stimulation in human colonic epithelial cells induces intracellular calcium oscillations and proliferation inhibition. J Cell Physiol. 2010;225:73–83. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes M, Rothe HM, Mattar P, Shapiro WB, Cifuentes M. Antilipolytic effect of calcimimetics depends on the allelic variant of calcium-sensing receptor gene polymorphism rs1042636 (Arg990Gly) Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:480–482. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi D, Brown EM. Physiology and pathophysiology of the calcium-sensing receptor in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F485–F499. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00608.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi D, Kemp PJ. The calcium-sensing receptor beyond extracellular calcium homeostasis: conception, development, adult physiology, and disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2012;74:271–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter CS, Pande S, Krits I, Slatopolsky E, Brown AJ. Destabilization of parathyroid hormone mRNA by extracellular Ca2+ and the calcimimetic R-568 in parathyroid cells: role of cytosolic Ca and requirement for gene transcription. J Mol Endocrinol. 2008;40:13–21. doi: 10.1677/JME-07-0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues LS, Cau AC, Bussmann LZ, Bastida G, Brunetto OH, Correa PH, et al. New mutation in the CASR gene in a family with familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (FHH) and neonatal severe hyperparathyroidism (NSHPT) Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2011;55:67–71. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302011000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez L, Tu C, Cheng Z, Chen TH, Bikle D, Shoback D, et al. Expression and functional assessment of an alternatively spliced extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor in growth plate chondrocytes. Endocrinology. 2005;146:5294–5303. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers KV, Dunn CK, Hebert SC, Brown EM. Localization of calcium receptor mRNA in the adult rat central nervous system by in situ hybridization. Brain Res. 1997;744:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossol M, Pierer M, Raulien N, Quandt D, Meusch U, Rothe K, et al. Extracellular Ca(2+) is a danger signal activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through G protein-coupled calcium sensing receptors. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1329. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe HM, Shapiro WB, Sun WY, Chou SY. Calcium-sensing receptor gene polymorphism Arg990Gly and its possible effect on response to cinacalcet HCl. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:29–34. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]