Abstract

Many particulate materials of sizes approximating that of a cell disseminate after being introduced into the body. While some move about within phagocytic inflammatory cells, others appear to move about outside of, but in contact with, such cells. In this report, we provide unequivocal photomicroscopic evidence that cultured, mature, human dendritic cells can transportin extracellular fashion over significant distances both polymeric beads and tumor cells. At least in the case of polymeric beads, both fibrinogen and the β2-integrin subunit, CD18, appear to play important roles in the transport process. These discoveries may yield insight into a host of disease-related phenomena, including and especially tumor cell invasion and metastasis.

Introduction

It is well-established that cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system traffic cellular debris and foreign particulate materials in vivo (Abbas and Lichtman, 2003b). Existing dogma has such cells phagocytosing, i.e., ingesting, particulates and then, as presumably intended, migrating or “draining” to sites distant from the initial encounter, e.g., a lymph node. During the course of studies in vivo exploring inflammation elicited by particles coated variously with fibrinogen (DeAnglis and Retzinger, 1999; Retzinger, 1987; Whitlock et al., 2002), we found some of the larger particles – those of diameters up to 25 μm – far removed from their site of intraperitoneal administration. Importantly, while those larger particles were invariably associated with one or more mononuclear inflammatory cell, they often appeared to be not within those cells, but alongside them. Because it seemed inconceivable such large particles could move through tissue unassisted and by simple diffusion, we hypothesized the mononuclear inflammatory cells in contact with the particles were, in fact, physically escorting the particles, directing their movement, even transporting them in extracellular fashion (DeAnglis and Retzinger, 1999).

In their role as antigen-presenting cells, mature dendritic cells migrate from peripheral sites, e.g., skin, at which they first encounter an antigen to lymph nodes where the antigen is further processed (Cutler et al., 2001; Rossi and Young, 2005). It occurred to us mature dendritic cells, which bind fibrinogen (Gordon, 2002; Skoberne et al., 2006) might be ideally suited to transporting from peripheral sites to lymph nodes larger particulate materials coated with the adhesive protein. If true, such extracellular trafficking might contribute mechanistically to a host of disease processes, not the least of which would be tumor cell invasion and metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Human fibrinogen was from Enzyme Research Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). The buffer composition of the fibrinogen as delivered was changed by dialyzing repetitively against normal saline. The fibrinogen was then aliquoted and stored frozen at -20°C until use. Prior to use, a frozen aliquot of fibrinogen solution was thawed to room temperature, diluted as appropriate, and then heated to 37°C. As necessary, fibrinogen concentration was determined using 5.12 × 105 M−1·cm−1 as the molar absorptivity of the protein at 280 nm (Mihalyi, 1968). Interleukin-4 (IL-4), interleukin-13 (IL-13), granulocyte/macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and macrophage inflammatory protein-3β (MIP-3β) were from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Blocking antibodies anti-CD11b (clones CBRM1/5 (Diamond and Springer, 1993) and ICRF44 (Heit et al., 2005)), anti-CD11c (clone 3.9 (Fan and Edgington, 1993; Loike et al., 1991)), anti-CD18 (clone TS1/18 (Altieri et al., 1988; Fan and Edgington, 1993; Postigo et al., 1991; Sitrin et al., 1998)), anti-TLR4 (clone HTA125 (Sugawara et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2001)), and IgG1 isotype control antibody (clone MOPC-21), were from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). Plasmin was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Trypsin was from Promega (Madison, WI). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) prepared by phenolic extraction from Escherichia coli 0127:B8, poly-L-lysine (Mr 70,000–150,000), colchicine, and Hank’s balanced salt solution were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Poly(styrene-divinylbenzene) beads of diameter 15.9 ± 2.3 μm were from Duke Scientific (Palo Alto, CA). Poly(styrene-divinylbenzene) beads of diameter 25.7 ± 5.8 μm were from Seragen Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN). Prior to use, beads were washed and lyophilized as described elsewhere (Retzinger et al., 1981). Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM), Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) containing 1.0 mM EDTA, 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA, ultra-pure agarose, and bovine fetal serum (FBS) were from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). Before use, FBS was heat-inactivated by incubating in a water bath at 56°C for 30 min. RPMI-1640 powder was from Gibco (Grand Island, NY). Citrated, random donor whole blood was from the Hoxworth Blood Center (Cincinnati, OH). All organic solvents were of a grade suitable for HPLC. All buffer materials and other reagents and chemicals were of the highest quality available commercially.

Coating beads with either fibrinogen or the proteins of serum-supplemented medium

Washed beads were coated with fibrinogen as described elsewhere (Retzinger et al., 1994; Retzinger and McGinnis, 1990; Retzinger et al., 1985), or the proteins of serum-supplemented medium. In the case of fibrinogen, the coating procedure involved simply dispersing the beads, 25 mg, ultrasonically in buffered solution containing the protein at a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL. The beads were then washed thrice with water, and dispersed in medium to a final desired concentration. To coat beads with the proteins of serum-supplemented medium, beads were simply dispersed in that medium prior to use. Beads were then counted and adjusted to the final desired concentration.

Isolation and storage of monocytes

Citrated whole blood, 30 mL, was placed into a 50 mL sterile conical plastic tube. To the blood was then added 6.0 mL of DPBS. The diluted sample was then underlaid with 10.0 mL of sterile Ficoll-Paque PLUS (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). After centrifuging the entire sample at 400 × g for 35 min, the mononuclear cells were collected in sterile fashion from above the separation medium, and then washed thrice using each time 35 mL of DPBS and centrifugation at 150 × g for 10 min. After washing, the cells were dispersed to concentrations ranging from 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 cells/mL in IMDM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and L-glutamine (2 mM). To separate monocytes from lymphocytes, 25 mL of the dispersion was layered over an equivalent volume of 46% iso-osmotic Percoll, and subjected to centrifugation at 550 × g for 30 min. Monocytes were subsequently recovered and washed once using 35 mL DPBS (4°C) and centrifugation, 400 × g for 10 min. The washed cells were then dispersed in 25 mL of DPBS and counted. After counting, cells were again washed, and reconstituted to a final concentration of 1.0 × 107 cell/mL using as diluent chilled (4°C) medium containing 40% (v/v) FBS, 50% (v/v) RPMI-1640 medium, and 10% (v/v) dimethylsulfoxide. Once in this medium, cells were frozen overnight at -80°C, and then moved to liquid nitrogen for storage until use (Seager Danciger et al., 2004).

Preparation of monocytes used for the generation of dendritic cells

A frozen aliquot of monocytes was first thawed by the addition of 10 volumes of warm (37°C) modified RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% (v/v) FBS, penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), and L-glutamine (2 mM). The cells were then pelleted using centrifugation at 150 × g for 10 min. After discarding the supernatant, the cells were dispersed in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented as above but with only 1.0% (v/v) FBS. As assessed using trypan blue exclusion, the viability of cells in such a preparation was always > 98%. Cells were adjusted to concentrations ranging from 1.2 × 106 to 4 × 106 cell/mL.

Generation of dendritic cells

Monocytes prepared as described above were added to small (35 mm ID) Petri dishes (Corning, Corning, NY) such that, depending upon the experiment, the final number of cells per dish was between 1.2 × 106 and 4.0 × 106. Over the course of 1 - 4 h and while being incubated at 37°C under an atmosphere of humidified CO2 (5.5%), the cells were allowed to settle and adhere to the dish. Afterwards, a culture was gently agitated to liberate loosely adhered cells, which were subsequently aspirated along with nearly the entire volume of medium. After replacing the exhausted medium with fresh modified (10%, v/v, FBS) RPMI-1640 medium, 100 μL of additional fresh medium containing both IL-4, 1000 U, and GM-CSF, 1000 U, was added. The cells were then incubated as before. After 2–3 d, another 1000 U each of IL-4 and GM-CSF were added to the cultures, along with 500 μL of fresh modified (10%, v/v, FBS) RPMI-1640 medium. Cells derived after 5 d of such treatment were considered immature dendritic cells (Banchereau et al., 2000; Mohty and Gaugler, 2003; Mosca et al., 2000; Sato et al., 1999). As indicated in the text, cells of preliminary studies were exposed to IL-13, 50 ng/mL, starting on culture day 7 and then used on culture day 11 (Sato et al., 1999). For later studies, with the exception of those designed to assess directed cell migration, dendritic cells were used after 5 through 8 d of culture, without having ever been treated with IL-13. For directed migration studies, mature activated dendritic cells were generated by adding to the culture medium of immature dendritic cells (i.e., culture day 5 through 8) 10 μg of LPS and 2 μg of PGE2 24 h prior to use of the cells (Dieu et al., 1998; Humrich et al., 2006; Luft et al., 2002; Scandella et al., 2002; Scandella et al., 2004). To maintain the dendritic cell phenotype, experimental cultures were supplemented with IL-4 and GM-CSF.

Photomicroscopy

An inverted microscope (Olympus IX71, Olympus, Melville, NY) equipped with a digital camera (Retiga 1394, QImaging, Burnaby, British Columbia) and a heated, CO2-purged, environmental chamber (Olympus) was used to visualize and record the movement of cells and beads cultured variously. The frequency and duration of image capture were as indicated in the figure legends.

Scanning electron microscopy

A sterile plastic cover slip was first placed at the bottom of a small Petri dish. Monocytes were then plated on the cover slip and differentiated into dendritic cells as described above. After that, ~ 60,000 fibrinogen-coated beads of the smaller diameter were added to the Petri dish, and the dish subsequently incubated for either an additional 2 or 24 h. Following incubation, all medium atop the cells was aspirated and was replaced with DPBS containing 3% (v/v) glutaraldehyde. The cover slip was subsequently removed from the dish, and the sample was then dehydrated by rinsing repeatedly in dilute ethanol. Samples were sputter-coated with gold palladium in preparation for electron microscopy (Hitachi S-3000N).

Assessment of dendritic cell adherence to beads

Dendritic cell adherence to beads was assessed using two different substrates. For photomicroscopic assessment, the substrate was a poly-L-lysine-modified glass cover slip (Kleinfeld et al., 1988) coated with bovine serum proteins that had been precipitated in situ using trichloroacetic acid (TCA). For this purpose, 100 μL of bovine serum was first spread as a film across the cover slip, after which the cover slip was allowed to set undisturbed for 5 min at room temperature. Subsequently, 100 μL of TCA (20%, w/v) was also spread across the cover slip, precipitating the serum proteins. After another 5 min, the TCA was neutralized by covering the surface of the cover slip with 100 μL of 0.05 M NaOH. Following extensive rinsing with sterile water, the cover slip was placed at the bottom of a small Petri dish, to which cells and various additives in culture medium were added.

For quantitative assessment of dendritic cell adherence to beads, dendritic cells from 6 d cultures (antibody studies) or mature dendritic cells (colchicine studies) were vigorously dislodged and harvested using a sterile transfer pipette. The harvested cells were then centrifuged at 150 × g for 10 min, after which the cells of the resulting pellet were first dispersed in RPMI-1640 medium and then distributed among the wells of a 24-well tissue culture plate, at a density of 2 × 105 cell/well. Test reagents were added to culture 1 h prior to adding beads. Beads used for adherence studies were always of the larger diameter. Approximately 300 beads were added to a well, and then evenly distributed using gentle agitation. The plate was then incubated at 37°C for 24 h. After that time, the contents of a well were scanned microscopically under high power. The first 60 beads visualized were used to assess bead-cell associations.

Protease treatment of bead-cell complexes

Dendritic cells that had been treated with IL-13 were harvested on culture day 11 and distributed to a density of 1x 104 cells/well in a 96-well microtiter plate. Approximately 100 fibrinogen-coated beads of the larger diameter were then added to each well. After 24 h, the culture medium from within each well was aspirated using sterile technique, and replaced with 200 μL of RPMI-1640 medium alone or RPMI-1640 medium containing either trypsin or plasmin, 10 U/mL. The plate was then incubated at 37°C for 1 h, after which the contents of the wells were gently agitated using a Pasteur pipette. After allowing 5 min for the contents of wells to settle, assessment was made microscopically of the percentage of cell-free beads in each well.

Under-agarose migration assay

General details of the under-agarose migration assay are described elsewhere (Heit et al., 2005; Heit and Kubes, 2003; Heit et al., 2002). Modifications to the published assay included a different agarose concentration (0.5%, v/v) and the use of heat-inactivated FBS as medium supplement. Using a dermal biopsy punch (Miltex, Inc, York, PA), 3 wells each of diameter 3.5 mm were made in linear array in the center of the agarose field. The distance between adjacent wells was 2.4 mm. Prior to use, the plate containing the agarose field was placed for at least 1 h in a humidified incubator at 37°C.

Prior to the start of an experiment, 10 μL of a dispersion of dendritic cells, 3×106 cell/mL, was placed within the central well. Depending upon the experiment and as described in the text, either beads, 5000, of the smaller diameter or tumor cells, 5000, in 10 μL of culture medium were also added to the central well. To begin an experiment, 10 μL of medium alone was added to one outer well and 10 μL of medium containing the chemoattractant MIP-3β, 2 μg/mL, was added to the other outer well.

Tumor cell culture and treatment

Cells of the highly metastatic breast cancer cell line CRL-2326 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in modified RPMI-1640. Cells were harvested using 0.05% trypsin/0.5 mM EDTA. When applicable, prior to exposure to fibrinogen, cells were first washed once with DPBS. Exposure to fibrinogen involved gentle agitation of the cells in DPBS containing 1.0 mg/mL of the protein. Fibrinogen-exposed cells were washed twice with DPBS and then re-dispersed in modified RPMI-1640 medium in preparation for co-culture with dendritic cells.

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean ± SD of replicate analyses. Results were compared using one-way ANOVA. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was facilitated using a commercially available program (SigmaPlot, SYSTAT Software, San Jose, CA).

Results and Discussion

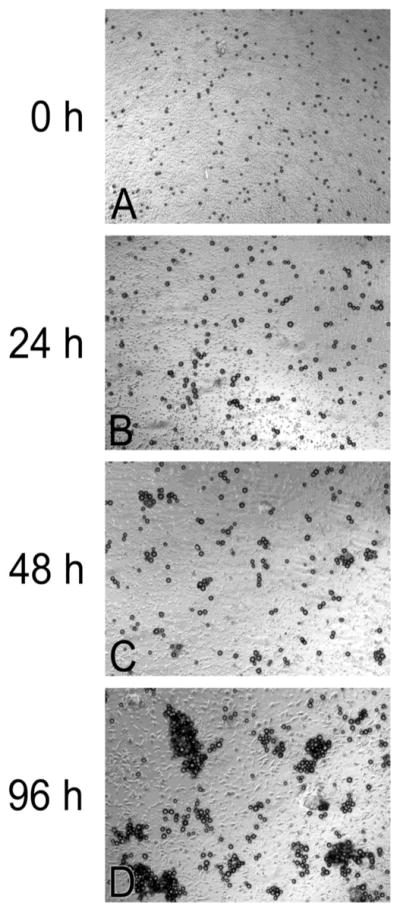

As a preliminary test of the hypothesis, fibrinogen-coated poly(styrene-divinylbenzene) beads of diameter 15.9 ± 2.3 μm were incubated with mature, monocyte-derived, human dendritic cells. Because fibrinogen-coated beads agglutinate in the presence of thrombin (Retzinger and McGinnis, 1990) and because other inflammatory cells of monocytic lineage express thrombin activity (Giuntoli and Retzinger, 1997), we reasoned the movement of beads on the dish surface might manifest as the formation of bead aggregates. In fact, such is the case. Over the course of 96 h, the distribution of beads changes from one of uniform monodispersity, Fig. 1A, to one of nonuniform polydispersity, Fig. 1B–D, with some bead aggregates containing tens of particles. Over the same period, fibrinogen-coated beads incubated in the absence of dendritic cells remain monodisperse and uniformly distributed.

Fig. 1.

Fibrinogen-coated beads, 15.9 ± 2.3 μm, aggregate over time when plated with cultured dendritic cells. Initially, beads co-incubated with dendritic cells are monodisperse, A. Over time, they become progressively more aggregated: B, 24 h; C, 48 h; and D, 96 h.

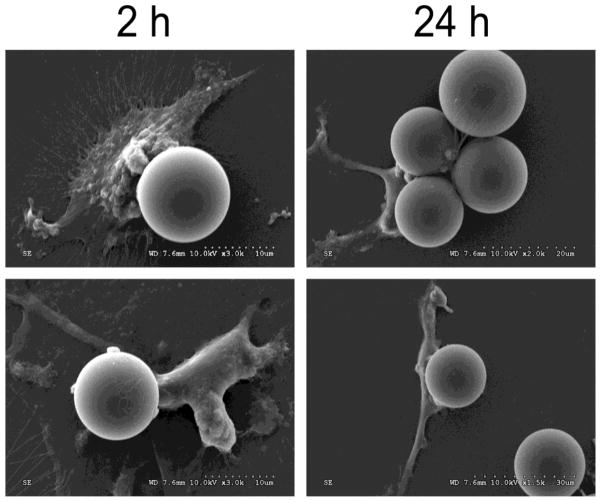

Encouraged by these results, time-lapse photomicroscopy was used to record the first 36 h of the process by which the beads aggregate (S1). What follows is a summary description of the course of events. Within minutes after adding them to an existing culture of mature dendritic cells, beads begin to move as a consequence of what appears to be their random contact with the motile cells. Such “nudging” yields the occasional pairing of beads that are already in close proximity. Over the course of the ensuing 36 h, many otherwise motile cells make sustained contact with beads. Although such contacts often involve individual cells with individual beads, occasionally many cells contact an individual bead, and individual cells can be in contact with several beads. During the entire period, all beads in contact with cells, whether individually or in collections, move: some gyrate locally, others move about in what appears to be haphazard fashion. With respect to the “bodies” of migrating cells with which beads are in contact, the beads usually appear to be centrally positioned, but, often, they appear to be caudal (being pulled) or, infrequently, they appear to be rostral (being pushed). Occasionally a bead or beads associated with a migrating cell or migrating group of cells is/are transferred to another migrating cell or migrating group of cells. At any time during the movement of cell-associated beads, the addition of trypsin results in the prompt disjunction of the complexes, leaving only monodisperse beads and intact, viable (> 98%), motile cells. Plasmin, too, dissociates the complexes suggesting fibrinogen adsorbed to the beads does indeed serve a tethering function. These direct observations indicate the beads are, in fact, moved in extra-cellular fashion, a conclusion supported by scanning electron micrographs of bead-associated cells, Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Electron micrographs showing representative extracellular complexes of fibrinogen-coated beads, 15.9 ± 2.3 μm, and dendritic cells, co-incubated for 2 or 24 h.

To assess the dependence of the extracellular transport process on fibrinogen coating the beads, we added to cultures of dendritic cells beads that had been wetted by exposure to culture medium containing as its only protein source fibrinogen-free serum. Time-lapse photomicroscopy (S2) shows beads wetted by serum proteins are, in fact, moved by dendritic cells, albeit much less robustly than their fibrinogen-coated counterparts, i.e., the process is characterized by bead-cell contacts that are slower to develop, fewer in number and of shorter duration. Furthermore, whereas beads coated with fibrinogen aggregate in the presence of dendritic cells, beads coated with proteins derived from serum do not. Although as yet untested, we suspect the failure of the latter beads to aggregate is due solely to the absence on their surface of fibrinogen, the inter-bead dimerization of which is responsible for the aggregation phenomenon (Retzinger and McGinnis, 1990).

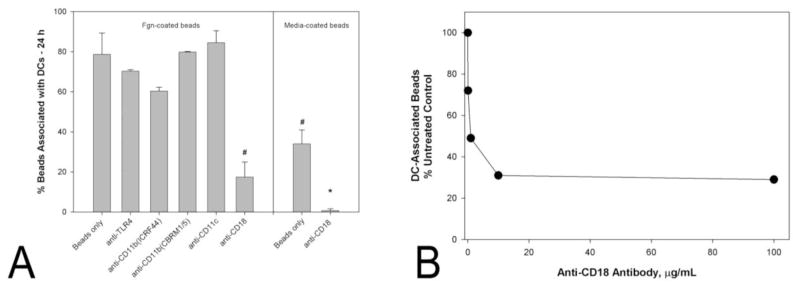

The extracellular transport of beads by dendritic cells necessarily requires association of the particles with the cells. The apparent “pulling” of beads by cells suggests true complexation of the one with the other. Given that fibrinogen appears to facilitate bead-cell complexation, it seemed reasonable to assess whether the process would be prevented by antibodies directed against dendritic cell receptors that bind fibrinogen, e.g., CD11b/CD18 (CR3 or MAC-1) (Gordon, 2002), CD11c/CD18 (CR4)(Skoberne et al., 2006), and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)(Gordon, 2002). While anti-CD11b, anti-CD11c and anti-TLR4 antibodies do not inhibit significantly the formation of bead-cell complexes, Fig. 3A, antibody directed against the shared β2-integrin subunit, CD18, does inhibit complexation significantly, in dose-dependent fashion, Fig. 3B. These data are supported by time-lapse photomicroscopic evidence (S3). We conclude CD18 is intimately involved in complexation of fibrinogen-coated beads with dendritic cells, and its obstruction prevents bead-cell complexation.

Fig. 3.

Of the antibodies tested, only one directed against CD18 significantly inhibited complexation of dendritic cells with either fibrinogen-coated beads or media-wetted beads, A. Beads were of diameter 25.7 ± 5.8 μm. Complexation, defined as the association of a bead with 3 or more dendritic cells, was assessed after a 24 h period of co-incubation. Bars indicate the means ± standard deviations of the results of triplicate experiments. The concentration of antibody was in all cases 10 μg/mL. A statistically significant difference, P < 0.001, from fibrinogen-coated beads incubated in the absence of any antibody is indicated by a #. A statistically significant difference, P < 0.001, from media-wetted beads incubated in the absence of any antibody is indicated by a *. Anti-CD18 inhibits complexation of dendritic cells with fibrinogen-coated beads in dose-dependent fashion, B. Beads and dendritic cells were co-incubated in the presence of the antibody for 24 h.

Having shown that fibrinogen adsorbed to their surface is not strictly required for the extracellular transport of beads, it behooved us to test whether any of the antibodies described above would inhibit even the limited complexation of dendritic cells with beads wetted by fibrinogen-free medium. In fact, the very same antibody that inhibits complexation of dendritic cells with fibrinogen-coated beads also inhibits complexation of the cells with medium-wetted beads, Fig. 3A. Taken together, these data suggest CD18 facilitates the formation of bead-cell complexes by a mechanism that may not involve fibrinogen uniquely.

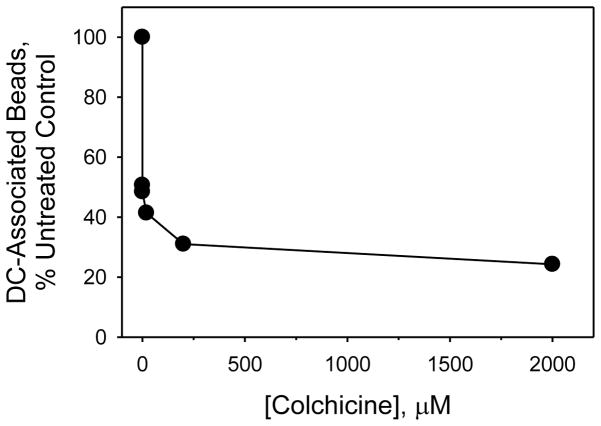

The attachment and capture of some particles by dendritic cells requires the operation of microtubules within the cells’ dendrites. Drugs that inhibit microtubule polymerization, e.g., colchicine, destabilize dendrites and, consequently, prevent particle attachment and capture (Swetman Andersen et al., 2006). For this reason, we tested whether colchicine would inhibit formation of bead-cell complexes. As shown in Fig. 4, colchicine does indeed inhibit complexation significantly, and at doses that do not appear to affect either the viability or motility of the dendritic cells (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Colchicine inhibits complexation of dendritic cells with fibrinogen-coated beads in dose-dependent fashion. Beads and dendritic cells were co-incubated in the presence of the drug for 24 h.

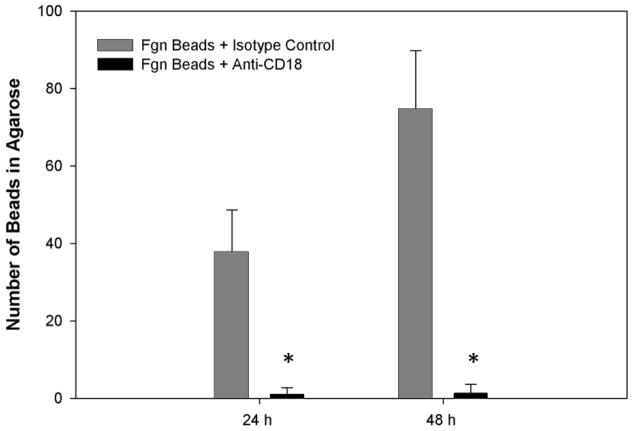

In their capacity as mediators of inflammation and immunity in vivo, dendritic cells undergo directed migration in response to a number of chemoattractants. Directed migration can be modeled in vitro using an imposed chemotactic signal (Zhao et al., 2005). We tested whether mature dendritic cells, when complexed with fibrinogen-coated beads, would respond in directed fashion to MIP-3β, a potent dendritic cell chemoattractant (Abbas and Lichtman, 2003a). Using time-lapse photomicroscopy, we obtained unequivocal evidence that not only individual mature dendritic cells, but also complexes formed between those cells and fibrinogen-coated beads, migrate in directed fashion, some complexes covering significant distances, > 500 μm, over an extended period, 24 h, in the process (S4). For a complex consisting of an individual bead and an individual cell, the migration rate can be surprisingly fast, e.g., upwards of 10 μm/min, even if only for a short period, 2–10 min. More routinely, such complexes move at a more constant, slower rate, e.g., 1–5 μm/min, for an extended period, 2–96 h. In support of earlier observations that suggested inflammatory cells in vivo can act cooperatively to move larger particles (Whitlock et al., 2002), we found that collections of juxtaposed cells can migrate in unison while in contact with either an individual bead or even an aggregate of beads, escorting the particles across significant distances. Occasionally, individual cells dislodge themselves from such a collection, transporting with them from the aggregate one to several beads as they distance themselves from the larger collection. Importantly, anti-CD18 antibody inhibits the extracellular transport of beads without inhibiting directed migration, Fig. 5. Inasmuch as chemokines orchestrate the migration of mature dendritic cells in vivo (Bachmann et al., 2006), it appears the extracellular transport and presentation of particulate materials by mature dendritic cells is not an artifactual process, but an intended one.

Fig. 5.

In comparison to an isotypic control, antibody directed against CD18 inhibits extracellular transport of fibrinogen-coated beads by dendritic cells. Cells, beads, 15.9 ± 2.3 μm, and antibody, 10 μg/mL, were incubated together within one of two adjacent wells of an agarose field for 2 h prior to the addition of MIP-3β to the other well. Bars indicate the number of beads observed within a high power field located midway between the two wells, 24 and 48 h after the imposition of chemoattractant. Data are the means ± SD’s of the results of 6 separate experiments. * indicates a significant difference between test and control results, P ≤ 0.001. Not shown are data indicating the isotypic control has no influence on bead transport beyond that of medium alone.

Physicians and scientists have long appreciated that solid malignancies are enveloped in fibrin(ogen) (Costantini and Zacharski, 1993; Dvorak et al., 1992). Indeed, that appreciation prompted studies designed to assess the role of the clotting protein in cancer-related phenomena, especially tumor cell invasion and metastasis (Costantini and Zacharski, 1992; Laki, 1974). It occurred to us that if cell-size particles can be transported in extracellular fashion by dendritic cells, then so, too, might tumor cells.

As a preliminary test of the proposal that extracellular transport contributes to the invasiveness and metastatic spread of malignant cells, human breast cancer cells (ductal carcinoma CRL-2326) were first bathed in either fibrinogen-free or fibrinogen-supplemented culture medium and then simply co-cultured with mature dendritic cells. Using this tumor cell system, we made several notable discoveries, some remarkably reminiscent of those made using the bead system: 1) dendritic cells make contact with tumor cells whether or not the tumor cells have been pre-exposed to fibrinogen, 2) the contacts dendritic cells make with tumor cells are more sustained if the tumor cells have been pre-exposed to fibrinogen and tumor cells that have been pre-exposed to fibrinogen aggregate more in the presence of dendritic cells than do tumor cells that have not been exposed to fibrinogen (S5), 3) whilst individual dendritic cells can contact and transport individual tumor cells, more often multiple dendritic cells, acting in what appears to be cooperative fashion, contact and transport individual tumor cells or small collections of tumor cells that otherwise remain stationary (S5), and 4) over the course of observation, tumor cells in association with dendritic cells remain viable, > 98%.

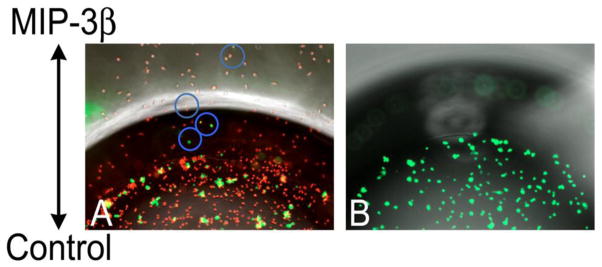

The preceding list of observations makes evident striking similarities between the treatments of polymeric beads and tumor cells by dendritic cells in culture, and a facilitating – but not required – role for fibrinogen in those treatments. In the experiments just described, viable cancer cells that had been pre-exposed to fibrinogen were merely substituted for the fibrinogen-coated beads of the previous experiments. Given fibrinogen’s predilection for malignant tumors (Costantini and Zacharski, 1993; Dvorak et al., 1992) and its functionality on sur-faces (Retzinger and McGinnis, 1990), we had fully expected monodisperse tumor cells would be handled by dendritic cells in much the same way as fibrinogen-coated beads. Having realized that expectation, we next attempted to make the acquisition and movement of tumor cells by dendritic cells more challenging. Toward that end, breast cancer cells were first cultured alone in fibrinogen-free medium for 48 h, yielding discrete “islands” of propagating tumor cells firmly adhered to the surface of the culture dish. Mature dendritic cells were then added to the culture, after which time-lapse photomicroscopy was used to record cellular interactions occurring on the surface of the dish (S6). Much to our surprise, even in the absence of added fibrinogen, dendritic cells engage and appear to process the adhered tumor cell islands for extended periods, acting collectively to disjoin and, subsequently, transport individual tumor cells from those islands. Furthermore, the extracellular transport of tumor cells by dendritic cells can be directed by MIP-3β, Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Fibrinogen-exposed breast tumor cells (green) form aggregates in the presence of dendritic cells (red), A. Over time, 24 h, some tumor cells (within the blue circles) are transported beyond the boundary of the plating well by dendritic cells migrating toward a reservoir of MIP-3β. In the absence of dendritic cells, fibrinogen-exposed tumor cells do not form aggregates, and they do not move toward an imposed chemotactic signal, B.

Conclusions

We have obtained cinematographic evidence that dendritic cells can transport large particles, including tumor cells, in extracellular fashion over relatively large distances across the surface of a tissue culture dish. In the case of polymeric beads, available evidence suggests fibrinogen, bound simultaneously to the particle and to a β2-integrin on the dendritic cell, can serve to tether the two species. In tissue culture, such tethering appears to facilitate the movement – indeed, carriage – of the otherwise stationary particles by dendritic cells, many of which are highly mobile. Not only are individual dendritic cells able to transport individual particles, but also collections of dendritic cells, acting in what appears to be cooperative fashion, can transport individual or even small groups of particles over significant distances. Although the studies reported herein focused on extracellular transport in vitro, we believe it likely, based on the earlier observations that, in part, prompted the present work, such transport also takes place in vivo. If it does, it would have relevance to a host of physiologic and pathophysiologic processes, including wound healing, tissue remodeling, sepsis, the dissemination in vivo of particulate materials, and, of course, metastasis. Indeed, it is the possibility that extracellular transport contributes to metastasis that we find most exciting because it would beg new ways of thinking about metastasis and its treatment.

Aside from any mechanistic understanding that may derive from this work, many practical applications may come from it as well. Because their migration can be directed, dendritic cells – or, perhaps, other inflammatory cells having similar ability – might one day be exploited as “nanotechnicians,” delivering micronized drugs or even stem cells in guided fashion to otherwise hard-to-reach sites in vivo. In that capacity, such cells might also be used in vitro or in vivo to direct the positioning of materials/cells in engineered tissues.

Much has yet to be done to establish extracellular transport as a biologically relevant process. Still, the very existence of the phenomenon – even if only in culture – has far-reaching implications, and warrants its further exploration.

Supplementary Material

Within minutes after their addition to an 11-day-old culture of IL-13-treated dendritic cells, fibrinogen-coated beads, 15.9 ± 2.3 μm, begin to be moved in extracellular fashion by the cells. During the 36 h of observation, some beads are made to gyrate locally; others are transported over considerable distances, > 300 μm. See text for details. The video frame rate is 15 fps.

Dendritic cells (500,000) were plated onto glass cover slips modified as described in Methods. After allowing the cells to settle onto a cover slip for 2 h, an aliquot of beads of diameter 25.7 ± 5.8 μm was added atop the substratum. Images on the left are of interactions of dendritic cells with fibrinogen-free beads, i.e., beads wetted using fibrinogen-free serum. Images on the right are of interactions of dendritic cells with fibrinogen-coated beads. Whereas dendritic cells immediately adhere to, aggregate around and move fibrinogen-coated beads, they adhere only slowly and in lesser number to fibrinogen-free beads, moving them little. The period of observation is 24 h. The video frame rate is 10 fps.

Dendritic cells (500,000) were plated onto glass cover slips modified as described in Methods. After 1 h, either anti-CD18 antibody, 10 ug/mL, or an isotypic control antibody, 10 ug/mL, was added to the culture. One h later, an aliquot of fibrinogen-coated beads of diameter 25.7 ± 5.8 μm was added atop each of the cover slips. Whereas dendritic cells treated with sham antibody, left, immediately adhere to, aggregate around and move fibrinogen-coated beads, dendritic cells treated with anti-CD18 antibody, right, adhere only slowly and in lesser number to fibrinogen-coated beads, moving them little. The period of observation is 24 h. The video frame rate is 10 fps.

As described in the text, mature dendritic cells and fibrinogen-coated beads, 15.9 ± 2.3 μm, were co-incubated in the central well of an under-agarose assay system. To initiate directed migration of the dendritic cells, a chemoattractant, MIP-3β, was added to a well adjacent to the central well. In this image, only the boundary of the well containing the cells and beads is visible. With respect to that boundary, the well containing the chemoattractant is directly above, but out of the visible field. Directed movement of dendritic cells and any accompanying beads becomes obvious 1-2 h after addition of the chemoattractant. Individual beads and bead aggregates are transported by dendritic cells in extracellular fashion, with many of the beads accumulating at the well's boundary or leaving the visible field, in the direction of the chemoattractant reservoir. The period of observation is 24 h. The video frame rate is 10 fps.

Mature dendritic cells dispersed in complete tissue culture medium were added to a Petri dish. After allowing the cells to settle for 2 h, an aliquot of breast tumor cells was added. Images on the left are of interactions of dendritic cells with tumor cells that had not been exposed to fibrinogen. Images on the right are of interactions of dendritic cells with tumor cells that had been exposed to fibrinogen as described in the methods. Whereas dendritic cells immediately adhere to, aggregate around and move fibrinogen-exposed tumor cells, they adhere only slowly and in lesser number to tumor cells that had not been exposed to fibrinogen. The period of observation is ~2 h. The video frame rate is 10 fps.

Mature dendritic cells were added to human breast tumor cells propagated as islands on the surface of a tissue culture dish. During the course of the video, dendritic cells act collectively, first, to disjoin a single tumor cell from a discrete collection of tumor cells and, then, to transport the single tumor cell away from the larger collection. The period of observation is ~17 h. The video frame rate is 15 fps.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to GSR from the Komen Foundation for Breast Cancer Research, Johnson & Johnson, and the National Cancer Institute. GSR thanks his parents, Ruth and David, for inspiration.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and Notes

- Abbas AK, Lichtman AH. Cellular and Molecular Immunology. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2003a. Antigen Processing and Presentation to T Lymphocytes; pp. 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas AK, Lichtman AH. Cellular and Molecular Immunology. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2003b. Introduction to Immunology; pp. 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri DC, et al. Oligospecificity of the cellular adhesion receptor Mac-1 encompasses an inducible recognition specificity for fibrinogen. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1893–900. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann MF, et al. Chemokines: more than just road signs. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:159–64. doi: 10.1038/nri1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J, et al. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini V, Zacharski LR. The role of fibrin in tumor metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1992;11:283–90. doi: 10.1007/BF01307183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini V, Zacharski LR. Fibrin and cancer. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69:406–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler CW, et al. Dendritic cells: immune saviors or Achilles’ heel? Infect Immun. 2001;69:4703–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.8.4703-4708.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAnglis AP, Retzinger GS. Fibrin(ogen) and inflammation: current understanding and new perspectives. Clin Immunol Newsletter. 1999;19:111–18. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond MS, Springer TA. A subpopulation of Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) molecules mediates neutrophil adhesion to ICAM-1 and fibrinogen. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:545–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.2.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieu MC, et al. Selective recruitment of immature and mature dendritic cells by distinct chemokines expressed in different anatomic sites. J Exp Med. 1998;188:373–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak HF, et al. Vascular permeability factor, fibrin, and the pathogenesis of tumor stroma formation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;667:101–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb51603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan ST, Edgington TS. Integrin regulation of leukocyte inflammatory functions. CD11b/CD18 enhancement of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha responses of monocytes. J Immunol. 1993;150:2972–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuntoli DL, Retzinger GS. Evidence for prothrombin production and thrombin expression by phorbol ester-treated THP-1 cells. Exp Mol Pathol. 1997;64:53–62. doi: 10.1006/exmp.1997.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S. Pattern recognition receptors: doubling up for the innate immune response. Cell. 2002;111:927–30. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit B, et al. Fundamentally different roles for LFA-1, Mac-1 and alpha4-integrin in neutrophil chemotaxis. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5205–20. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit B, Kubes P. Measuring chemotaxis and chemokinesis: the under-agarose cell migration assay. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:PL5. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.170.pl5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit B, et al. An intracellular signaling hierarchy determines direction of migration in opposing chemotactic gradients. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:91–102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humrich JY, et al. Mature monocyte-derived dendritic cells respond more strongly to CCL19 than to CXCL12: consequences for directional migration. Immunology. 2006;117:238–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinfeld D, et al. Controlled outgrowth of dissociated neurons on patterned substrates. J Neurosci. 1988;8:4098–120. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04098.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laki K. Fibrinogen and metastases. J Med. 1974;5:32–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loike JD, et al. CD11c/CD18 on neutrophils recognizes a domain at the N terminus of the A alpha chain of fibrinogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1044–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft T, et al. Functionally distinct dendritic cell (DC) populations induced by physiologic stimuli: prostaglandin E(2) regulates the migratory capacity of specific DC subsets. Blood. 2002;100:1362–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalyi E. Physicochemical studies of bovine fibrinogen. IV. Ultraviolet absorption and its relation to the structure of the molecule. Biochemistry. 1968;7:208–23. doi: 10.1021/bi00841a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohty M, Gaugler B. Dendritic cells: interfaces with immunobiology and medicine. Leukemia; A report from the Keystone Symposia Meeting; Keystone. 3–8 March 2003; 2003. pp. 1753–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosca PJ, et al. A subset of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells expresses high levels of interleukin-12 in response to combined CD40 ligand and interferon-gamma treatment. Blood. 2000;96:3499–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postigo AA, et al. Regulated expression and function of CD11c/CD18 integrin on human B lymphocytes. Relation between attachment to fibrinogen and triggering of proliferation through CD11c/CD18. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1313–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retzinger GS. Dissemination of beads coated with trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate: a possible role for coagulation in the dissemination process. Exp Mol Pathol. 1987;46:190–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(87)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retzinger GS, et al. The binding of fibrinogen to surfaces and the identification of two distinct surface-bound species of the protein. J Colloid and Interface Science. 1994;168:514–521. [Google Scholar]

- Retzinger GS, McGinnis MC. A turbidimetric method for measuring fibrin formation and fibrinolysis at solid-liquid interfaces. Anal Biochem. 1990;186:169–78. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90592-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retzinger GS, et al. A method for probing the affinity of peptides for amphiphilic surfaces. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:131–40. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retzinger GS, et al. The role of surface in the biological activities of trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate. Surface properties and development of a model system. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:8208–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M, Young JW. Human dendritic cells: potent antigen-presenting cells at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immunity. J Immunol. 2005;175:1373–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, et al. Interleukin-13 is involved in functional maturation of human peripheral blood monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:326–36. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(98)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scandella E, et al. Prostaglandin E2 is a key factor for CCR7 surface expression and migration of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2002;100:1354–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scandella E, et al. CCL19/CCL21-triggered signal transduction and migration of dendritic cells requires prostaglandin E2. Blood. 2004;103:1595–601. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seager Danciger J, et al. Method for large scale isolation, culture and cryopreservation of human monocytes suitable for chemotaxis, cellular adhesion assays, macrophage and dendritic cell differentiation. J Immunol Methods. 2004;288:123–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitrin RG, et al. Fibrinogen activates NF-kappa B transcription factors in mononuclear phagocytes. J Immunol. 1998;161:1462–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoberne M, et al. The apoptotic-cell receptor CR3, but not alphavbeta5, is a regulator of human dendritic-cell immunostimulatory function. Blood. 2006;108:947–55. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara S, et al. Monocytic cell activation by Nonendotoxic glycoprotein from Prevotella intermedia ATCC 25611 is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4951–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.8.4951-4957.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swetman Andersen CA, et al. beta1-Integrins determine the dendritic morphology which enhances DC-SIGN-mediated particle capture by dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1295–303. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JE, et al. Involvement of CD14 and toll-like receptors in activation of human monocytes by Aspergillus fumigatus hyphae. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2402–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2402-2406.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock PW, et al. Distribution of silicon/e in tissues of mice of different fibrinogen genotypes following intraperitoneal administration of emulsified poly(dimethylsiloxane) [correction of poly(dimethysiloxane)] Exp Mol Pathol. 2002;72:161–71. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2002.2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, et al. Directed cell migration via chemoattractants released from degradable microspheres. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5048–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Within minutes after their addition to an 11-day-old culture of IL-13-treated dendritic cells, fibrinogen-coated beads, 15.9 ± 2.3 μm, begin to be moved in extracellular fashion by the cells. During the 36 h of observation, some beads are made to gyrate locally; others are transported over considerable distances, > 300 μm. See text for details. The video frame rate is 15 fps.

Dendritic cells (500,000) were plated onto glass cover slips modified as described in Methods. After allowing the cells to settle onto a cover slip for 2 h, an aliquot of beads of diameter 25.7 ± 5.8 μm was added atop the substratum. Images on the left are of interactions of dendritic cells with fibrinogen-free beads, i.e., beads wetted using fibrinogen-free serum. Images on the right are of interactions of dendritic cells with fibrinogen-coated beads. Whereas dendritic cells immediately adhere to, aggregate around and move fibrinogen-coated beads, they adhere only slowly and in lesser number to fibrinogen-free beads, moving them little. The period of observation is 24 h. The video frame rate is 10 fps.

Dendritic cells (500,000) were plated onto glass cover slips modified as described in Methods. After 1 h, either anti-CD18 antibody, 10 ug/mL, or an isotypic control antibody, 10 ug/mL, was added to the culture. One h later, an aliquot of fibrinogen-coated beads of diameter 25.7 ± 5.8 μm was added atop each of the cover slips. Whereas dendritic cells treated with sham antibody, left, immediately adhere to, aggregate around and move fibrinogen-coated beads, dendritic cells treated with anti-CD18 antibody, right, adhere only slowly and in lesser number to fibrinogen-coated beads, moving them little. The period of observation is 24 h. The video frame rate is 10 fps.

As described in the text, mature dendritic cells and fibrinogen-coated beads, 15.9 ± 2.3 μm, were co-incubated in the central well of an under-agarose assay system. To initiate directed migration of the dendritic cells, a chemoattractant, MIP-3β, was added to a well adjacent to the central well. In this image, only the boundary of the well containing the cells and beads is visible. With respect to that boundary, the well containing the chemoattractant is directly above, but out of the visible field. Directed movement of dendritic cells and any accompanying beads becomes obvious 1-2 h after addition of the chemoattractant. Individual beads and bead aggregates are transported by dendritic cells in extracellular fashion, with many of the beads accumulating at the well's boundary or leaving the visible field, in the direction of the chemoattractant reservoir. The period of observation is 24 h. The video frame rate is 10 fps.

Mature dendritic cells dispersed in complete tissue culture medium were added to a Petri dish. After allowing the cells to settle for 2 h, an aliquot of breast tumor cells was added. Images on the left are of interactions of dendritic cells with tumor cells that had not been exposed to fibrinogen. Images on the right are of interactions of dendritic cells with tumor cells that had been exposed to fibrinogen as described in the methods. Whereas dendritic cells immediately adhere to, aggregate around and move fibrinogen-exposed tumor cells, they adhere only slowly and in lesser number to tumor cells that had not been exposed to fibrinogen. The period of observation is ~2 h. The video frame rate is 10 fps.

Mature dendritic cells were added to human breast tumor cells propagated as islands on the surface of a tissue culture dish. During the course of the video, dendritic cells act collectively, first, to disjoin a single tumor cell from a discrete collection of tumor cells and, then, to transport the single tumor cell away from the larger collection. The period of observation is ~17 h. The video frame rate is 15 fps.