Abstract

Purpose

A laparoscopic appendectomy is now commonly performed. The push in recent years toward reducing the number of ports required to perform this surgery has led to the development of a single-port laparoscopic appendectomy (SPA). We compared postoperative pain after an SPA using a glove port with a percutaneous organ-holding device (group 1) with that of an SPA using a commercially-available multichannel single-port device (group 2).

Methods

Between March 2010 and July 2011, a retrospective study was conducted of a total of 77 patients who underwent an SPA by three surgeons at department of surgery, Kangbuk Samsung Medical Center. Thirty-eight patients received an SPA using a glove port with a percutaneous organ-holding device. The other 39 patients received an SPA using a commercially-available multichannel single port (Octo-Port or SILS Port). Operative details and postoperative outcomes were collected and evaluated.

Results

There were no differences in the mean operative times, times to pass gas, postoperative hospital stays, or cosmetic satisfaction scores between the two groups. The pain score in the first 24 hours after surgery was higher in group 2 than group 1 patients (P < 0.001). Furthermore, the trocar used in group 2 was more expensive than that used in group 1.

Conclusion

An SPA using a glove port with a percutaneous organ-holding device was associated with a lower pain score during the first 24 hours after surgery because of the shorter fascia incision length and a cheaper cost than an SPA using a commercially-available multichannel single-port device.

Keywords: Single port, Percutaneous organ-holding device, Laparoscopic appendectomy

INTRODUCTION

The laparoscopic appendectomy (LA) is now considered the gold standard for an appendectomy, even in complicated appendicitis cases [1]. A LA has several advantages over a conventional appendectomy, including improved cosmetic outcome, reduced postoperative pain, reduced operative wound complications, shorter length of hospital stay, and quicker recovery to the activities of daily life [1]. To maximize the benefits of minimally-invasive surgery, a continued push has been made to reduce the number of ports required to perform such procedures. The number of reported laparoscopic single-site procedures based on a single incision has, therefore, increased in recent years [1-5]. With the reduction in the number of ports to one, the length of the single fascia incision has tended to increase [6-8]. Single umbilical incisions reported in previous studies are typically 15 to 20 mm in length, and the length of the fascia incision may be closely associated with postoperative pain [6]. A single-port laparoscopic appendectomy (SPA) using a glove port with a percutaneous organ-holding device can reduce the length of the fascia incision and can, therefore, potentially reduce postoperative pain [9]. To test this hypothesis, we compared postoperative pain between an SPA using a glove port with a percutaneous organ-holding device and an SPA using a commercially-available multichannel single port for treating simple appendicitis.

METHODS

Patients

Between March 2010 and July 2011, we conducted a retrospective analysis of a total of 77 single-port laparoscopic appendectomies that were performed at department of surgery, Kangbuk Samsung Medical Center by three surgeons skilled in conventional laparoscopic surgery. All patients had been evaluated for appendicitis in the emergency room. All patients with appendicitis were diagnosed by using computed tomography. The type of SPA was chosen based on the surgeon's preference after written informed consent regarding the SPA had been obtained from the patient. Thirty-eight patients (group 1) received an SPA using a glove port with a percutaneous organ-holding device. The other 39 patients (group 2) received an SPA using a commercially-available multichannel single port, an Octo-Port (Dalim SurgNet, Seoul, Korea) or the product's name is SILS port (Covidien Inc. Norwalk, CT, USA).

Operative technique

The patient was placed in a supine position with the surgeon and assistant on the patient's left and right, respectively. In group 1, an SPA using a glove port with a percutaneous organ-holding device was performed. A handmade glove port was prepared before the skin incision. Two fingers of the powder-free surgical glove were cutoff, and two trocars (5 and 12 mm, respectively) were inserted and immobilized with 1-0 silk. A 10 mm longitudinal incision was made through the umbilicus, and the fascia and peritoneum were opened under direct vision. The inner ring of a wound retractor (Alexis, Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, USA) was inserted into the umbilical incision, and the rim of the outer ring was rolled down to the anchor. The glove was snapped onto the external top, and an airtight seal was created around the ports with 1-0 silk sutures. The operation was performed with the surgeon and assistant (scopist) positioned on the left side of the patient. The patient was placed in the Trendelenburg position with his/her left side down. A rigid 0° 5-mm laparoscope and 5 mm laparoscopic instrument were inserted through the cannulas. After intra-abdominal access, the appendix was identified, and to overcome inadequate retraction, a percutaneous organ-holding device (Suture Grasper Closure Device, Mediflex Surgical Products, Islandia, NY, USA) was inserted in the right lower quadrant abdomen to grasp the appendix (Fig. 1). The mesoappendix was first divided using ultrasonic shears (Harmonic Scalpel, Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA); then, the base of the appendix was ligated using a round loop (Laploop, Sejong Medical Co., Paju, Korea) and resected. The appendix was removed in a specimen bag (LapBag, Sejong Medical Co.) through the incision site by using the wound retractor. After all procedures had been completed, the peritoneum and the fascia were approximated and closed with 2-0 Vicryl sutures. The subcutaneous layer was sutured with 4-0 Vicryl to align the skin edges without using skin sutures.

Fig. 1.

(A, B) Percutaneous organ-holding device (suture grasper closure device, Mediflex Surgical Products, Islandia, NY, USA). (C) Grasping the appendix with a percutaneous organ-holding device.

In group 2, an SPA using a commercially-available multichannel single port was performed. A 20-mm longitudinal incision was made through the umbilicus, and the fascia and peritoneum were opened under direct vision. The commercial port was then inserted into the incision. The rest of the procedure was conducted as described for the conventional single-port appendectomy.

Perioperative management

Patients received 1.0 g/kg (adult) or 20 mg/kg (child) of cefotetan before the operation. Intravenous antibiotics were continued during the hospital stay. Patient-controllable anesthesia was not used. Relaxation therapy through breath control and muscle relaxation was administered first for pain management; then, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were injected intramuscularly as needed for pain that did not improve. Patients were eligible for discharge when they could tolerate a regular diet.

Data collection

Age, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, operative time, postoperative pain using a visual analogue scale (VAS), postoperative length of hospital stay, postoperative complications, and cosmetic satisfaction were recorded. Postoperative pain was measured using a VAS with a score ranging from "no pain" (score 0) to "worst possible pain" (score 10). VAS scoring was performed every 3 hours except during sleep and whenever patients complained of pain; this was done by the attending nurse who was unaware of the ongoing study. Postoperative complications included wound infection, incisional hernia and intraabdominal complications such as bleeding, stump leakage, intraabdominal abscess, ileus, etc. It based on symptoms and physical examinations. The wound satisfaction score (WSS; very unsatisfied, 1; unsatisfied, 2; acceptable, 3; satisfied, 4; very satisfied, 5) was recorded for each patient on the seventh postoperative day to assess the patient's satisfaction with his/her scar. The basic cost for the single-port system was calculated for both groups. Costs of laparoscopic instruments were not included in the cost analysis.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as median values and interquartile ranges or mean values ± standard deviations. Continuous variables were compared using the Student t-test or a repeated measures analysis of variance. Discrete variables were analyzed with the chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS ver. 19.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). A probability of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

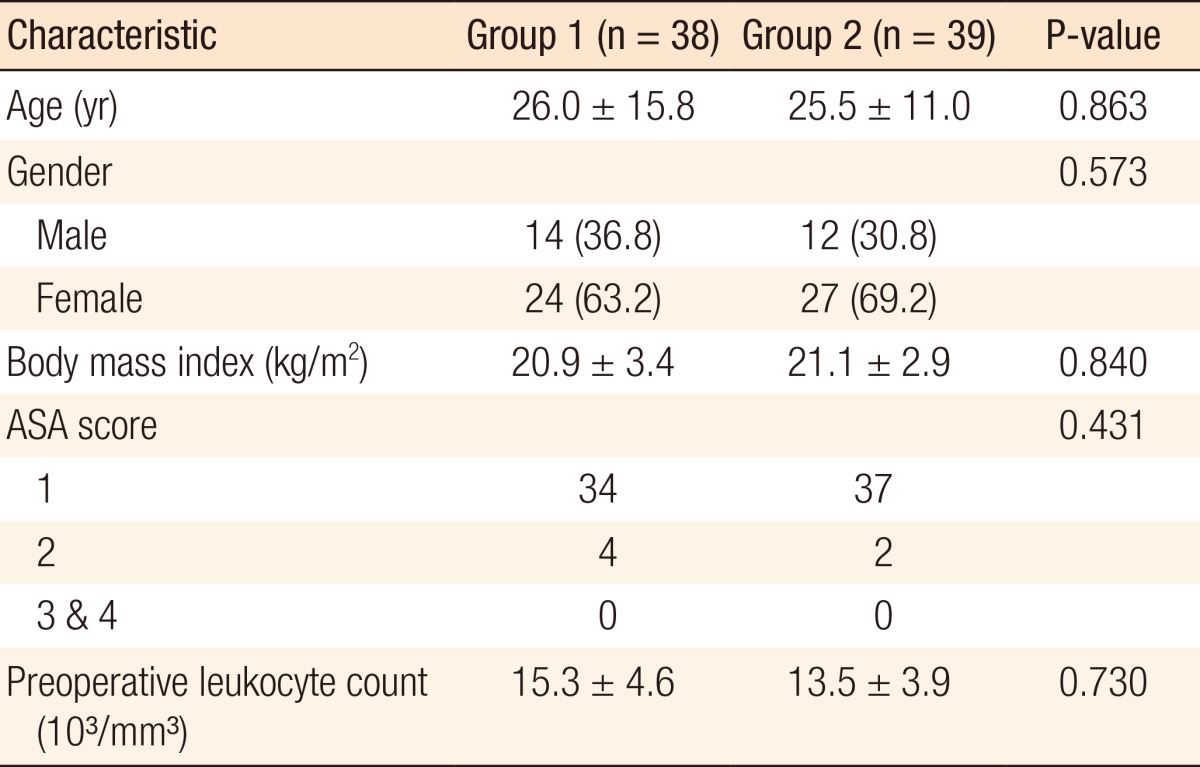

There were no differences in age, sex, BMI, ASA score, or preoperative leukocyte count between the two groups (Table 1). Perioperative outcomes are listed in Table 2. The mean operative time was shorter in group 1 than group 2, but this difference did not reach statistical significance. There were no differences between the two groups in the times to pass gas or hospital stays. There were no postoperative complications during the follow-up period in either group. Cosmetic outcomes on the seventh postoperative day were excellent with a minimal, barely-visible scar in most patients, regardless of group assignment. There were no significant differences in cosmetic outcomes between the two groups.

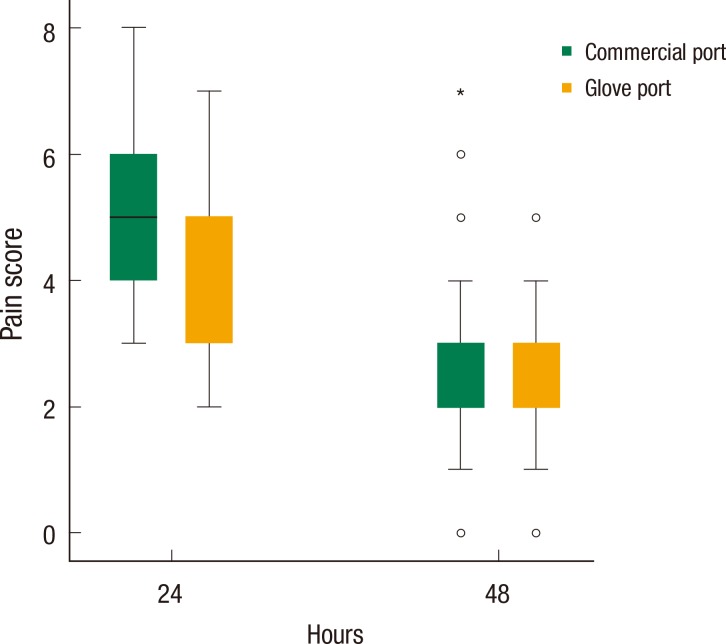

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of the patients

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

Group 1, single-port laparoscopic appendectomy (SPA) using a percutaneous organ-holding device; group 2, SPA using a commercially-available multichannel single port; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists score.

Table 2.

Perioperative outcomes

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

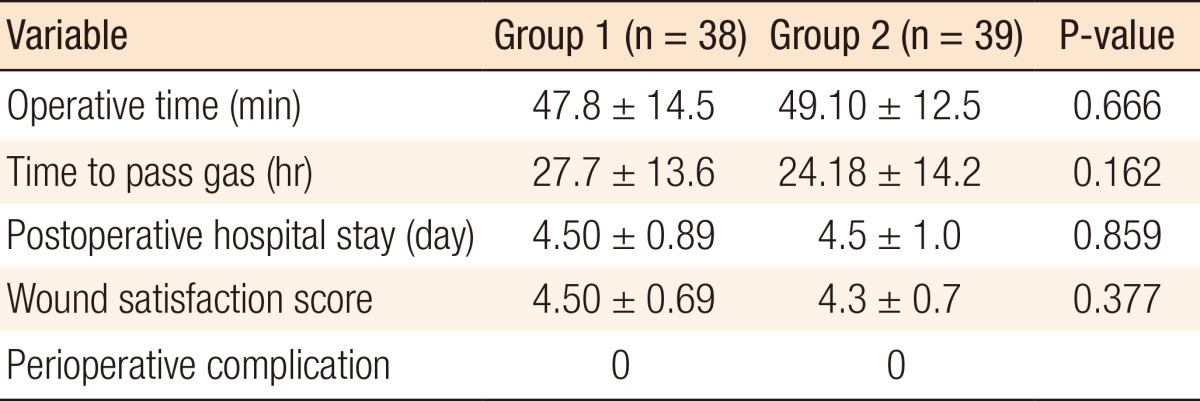

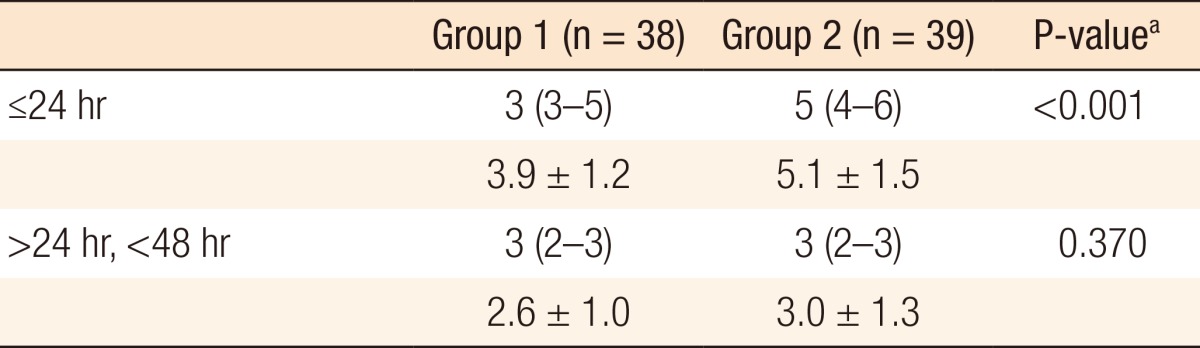

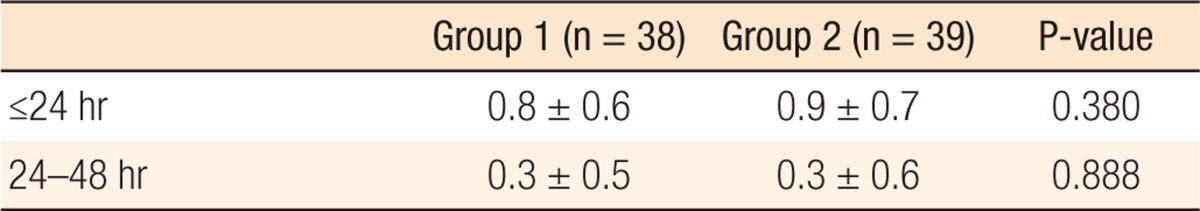

The median and the mean postoperative pain scores are listed in Table 3. When a discrepancy in pain scores presented within the same period, the highest scores were analyzed. Pain scores during the first 24 hours after surgery were higher in group 2 than group 1 (P < 0.001). However, there were no differences in pain scores between the two groups 24 to 48 hours after surgery (Fig. 2). Patients in the group 2 tended to receive more total doses of analgesics (NSAIDs) in the first 24 hours after surgery, but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 4). The basic cost of a trocar in group 1 was calculated as 237,517 Korean won (KRW). In group 2, the Octo-Port cost 354,755 KRW, and the SILS Port cost 351,288 KRW.

Table 3.

Postoperative pain score using a visual analogue scale

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or mean ± standard deviation.

P-values were corrected by using Bonferroni method.

aMann-Whitney U-test.

Fig. 2.

Postoperative pain score on the visual analogue scale according to the type of port as a function of time after a laparoscopic appendectomy. Pain scores during the first 24 hours after surgery were higher in group 2 than group 1 (P < 0.001).

Table 4.

Mean number of analgesic doses after surgery

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

Broad acceptance of laparoscopic surgery has resulted in attempts to reduce the number of incisions [2, 10]. Single-port laparoscopic surgeries, including appendectomies, adrenalectomies, cholecystectomies, gastric bandings, and nephrectomies, have recently been performed for various intra-abdominal pathologies [3-8, 11-17]. The SPA has gained widespread acceptance because it has many advantages over a conventional multiport laparoscopic appendectomy, including better cosmetic outcomes due to a relatively hidden umbilical scar and no need for additional incisions [1, 6, 13, 18]. Furthermore, the SPA is associated with a decrease in morbidity related to visceral and vascular injuries during trocar placement [16, 19].

However, with the reduction in the number of ports to one, the length of the single fascia incision has tended to become longer. The length of the fascia incision is closely associated with postoperative pain [6-8]. Single umbilical incisions reported in previous studies reached lengths of 20 mm [6]. In the present study, we achieved an umbilical incision length of 10 mm by using an SPA with a percutaneous organ-holding device because only two trocars were inserted through the single port; a rigid 0° 5-mm laparoscope and a 5 mm laparoscopic instrument. This could explain the low pain score in the first 24 hours after surgery in these patients. During the operation, the percutaneous organ-holding device can function as a grasper [9]. Using this device, the appendix can be grasped and drawn to allow triangulation for division of the mesoappendix.

The increase in single-port surgery has increased the range of trocar options available. Three single-port systems are employed at our institution, with the type of system used based on each surgeon's preference: a handmade glove port, an Octo-Port, or a SILS port. Commercially-available multichannel single ports require advanced surgical skills if they are to be operated safely by using coaxially-arranged instruments with the resultant limited range of motion [6, 14, 16]. This is associated with poorer SPA performance and increased surgeon workload and is the reason the SPA is more technically challenging than a conventional multiport LA [18, 20]. This also tends to increase the operative time of the SPA [6, 10, 18]. Longer operative times may translate to more stretching of the single umbilical wound and subsequently more postoperative pain [6].

The difficulty in achieving triangulation using an SPA can be overcome by using a percutaneous organ-holding device. Some surgeons use a minigrasper without a trocar to retract the gallbladder in a single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy. With the help of this needlescopic instrument, the operative time can be decreased, scarring can be minimized, and the surgical procedure can be performed more easily and safely [9]. This improvement in SPA execution may shorten the operative time and reduce postoperative pain. For this reason needlescopic instruments have become important tools for expanding the indications for SILS in various fields of surgery [21]. In the present study, the mean operative time tended to be shorter in patients who underwent an SPA using a glove port with a percutaneous organ-holding device than in the commercial port patients, but this difference was not statistically significant. This may due to the small number of patients and the differences among surgeons. Larger comparative studies should be performed to determine whether an SPA using a percutaneous organ-holding device is more time-effective than an SPA using a commercial multichannel single port.

Although many surgeons in Korea use a commercially-available multichannel single port, that may not be suitable for the medical environments of other countries for economic reasons [7]. New surgical devices for an SPA cost more than conventional devices for multiport an LA [15]. When performing an SPA using a glove port with a percutaneous organ-holding device, the only additional operation material required is a wound retractor; thus, developing or purchasing new devices is not necessary [7, 15]. An SPA using a glove port with a percutaneous organ-holding device can reduce not only postoperative pain but also the cost of surgery.

An SPA may yield better cosmetic outcomes than conventional surgery because the number of trocar incisions is reduced [18]. There is no gold-standard standardized scoring system to evaluate wound cosmetics. We used a 5-point WSS to assess patients' cosmetic satisfaction [22]. Despite the differences in lengths of the umbilical incisions between the two groups in our study, no statistical differences in cosmetic outcomes were observed. This result may be due to the dimpled nature of the umbilicus, which makes scars of up to 20 mm invisible. The incision made for the SPA in group 1 was almost invisible on the seventh postoperative day.

In conclusion, an SPA using a glove port with a percutaneous organ-holding device can reduce the length of the umbilical fascia incision and improve the execution of the operation. Furthermore, this method can reduce postoperative pain by shortening the length of the umbilical fascia incision, and it is cost-effective relative to an SPA using a commercial multichannel port.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Tiwari MM, Reynoso JF, Tsang AW, Oleynikov D. Comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic and open appendectomy in management of uncomplicated and complicated appendicitis. Ann Surg. 2011;254:927–932. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822aa8ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ateş O, Hakguder G, Olguner M, Akgur FM. Single-port laparoscopic appendectomy conducted intracorporeally with the aid of a transabdominal sling suture. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1071–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwak HN, Kim JH, Yun JS, Son BH, Chung WY, Park YL, et al. Conventional laparoscopic adrenalectomy versus laparoscopic adrenalectomy through mono port. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:439–442. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31823a9ab7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwasnicki RM, Aggarwal R, Lewis TM, Purkayastha S, Darzi A, Paraskeva PA. A comparison of skill acquisition and transfer in single incision and multi-port laparoscopic surgery. J Surg Educ. 2013;70:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakravartty S, Murgatroyd B, Ashton D, Patel A. Single and multiple incision laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: a matched comparison. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1695–1700. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0704-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HO, Yoo CH, Lee SR, Son BH, Park YL, Shin JH, et al. Pain after laparoscopic appendectomy: a comparison of transumbilical single-port and conventional laparoscopic surgery. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012;82:172–178. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2012.82.3.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JS, Choi YI, Lim SH, Hong TH. Transumbilical single port laparoscopic appendectomy using basic equipment: a comparison with the three ports method. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012;83:212–217. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2012.83.4.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.St Peter SD, Adibe OO, Juang D, Sharp SW, Garey CL, Laituri CA, et al. Single incision versus standard 3-port laparoscopic appendectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2011;254:586–590. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31823003b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gulpinar K, Ozdemir S, Ozis SE, Aydin T, Korkmaz A. Single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy by using a 2 mm atraumatic grasper without trocar. HPB Surg. 2011;2011:761315. doi: 10.1155/2011/761315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panait L, Bell RL, Duffy AJ, Roberts KE. Two-port laparoscopic appendectomy: minimizing the minimally invasive approach. J Surg Res. 2009;153:167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afaneh C, Aull MJ, Gimenez E, Wang G, Charlton M, Leeser DB, et al. Comparison of laparoendoscopic single-site donor nephrectomy and conventional laparoscopic donor nephrectomy: donor and recipient outcomes. Urology. 2011;78:1332–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SW, Lee JY. Laparoendoscopic single-site urological surgery using a homemade single port device: the first 70 cases performed at a single center by one surgeon. J Endourol. 2011;25:257–264. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greaves N, Nicholson J. Single incision laparoscopic surgery in general surgery: a review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93:437–440. doi: 10.1308/003588411X590358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berkowitz JR, Allaf ME. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery: complications and how to avoid them. BJU Int. 2010;106(6 Pt B):903–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi M, Asakuma M, Komeda K, Miyamoto Y, Hirokawa F, Tanigawa N. Effectiveness of a surgical glove port for single port surgery. World J Surg. 2010;34:2487–2489. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0649-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HJ, Lee JI, Lee YS, Lee IK, Park JH, Lee SK, et al. Single-port transumbilical laparoscopic appendectomy: 43 consecutive cases. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2765–2769. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee WS, Choi ST, Lee JN, Kim KK, Park YH, Lee WK, et al. Single-port laparoscopic appendectomy versus conventional laparoscopic appendectomy: a prospective randomized controlled study. Ann Surg. 2013;257:214–218. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318273bde4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goel R, Buhari SA, Foo J, Chung LK, Wen VL, Agarwal A, et al. Single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy: prospective case series at a single centre in Singapore. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:318–321. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182311bd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frutos MD, Abrisqueta J, Lujan J, Abellan I, Parrilla P. Randomized prospective study to compare laparoscopic appendectomy versus umbilical single-incision appendectomy. Ann Surg. 2013;257:413–418. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318278d225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YS, Kim JH, Moon EJ, Kim JJ, Lee KH, Oh SJ, et al. Comparative study on surgical outcomes and operative costs of transumbilical single-port laparoscopic appendectomy versus conventional laparoscopic appendectomy in adult patients. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:493–496. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181c15493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tagaya N, Kubota K. Reevaluation of needlescopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:137–143. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1839-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arrigoni SC, Halbersma WB, Grandjean JG, Mariani MA. Patients' satisfaction and wound-site complications after radial artery harvesting for coronary artery bypass. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;14:324–326. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivr091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]