Background: Cholesterol transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 export excess cellular cholesterol and protect against atherosclerosis.

Results: Cholesterol loading decreases cellular degradation of ABCA1 and ABCG1 and also their ubiquitination.

Conclusion: Cholesterol-dependent suppression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 ubiquitination decreases their proteasomal degradation.

Significance: This mechanism enhances the capacity of cholesterol-loaded cells to export their excess cholesterol.

Keywords: ABC Transporter, Cholesterol, Proteasome, Protein Degradation, Ubiquitination, ABCA1, ABCG1

Abstract

The objective of this study was to examine the influence of cholesterol in post-translational control of ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein expression. Using CHO cell lines stably expressing human ABCA1 or ABCG1, we observed that the abundance of these proteins is increased by cell cholesterol loading. The response to increased cholesterol is rapid, is independent of transcription, and appears to be specific for these membrane proteins. The effect is mediated through cholesterol-dependent inhibition of transporter protein degradation. Cell cholesterol loading similarly regulates degradation of endogenously expressed ABCA1 and ABCG1 in human THP-1 macrophages. Turnover of ABCA1 and ABCG1 is strongly inhibited by proteasomal inhibitors and is unresponsive to inhibitors of lysosomal proteolysis. Furthermore, cell cholesterol loading inhibits ubiquitination of ABCA1 and ABCG1. Our findings provide evidence for a rapid, cholesterol-dependent, post-translational control of ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein levels, mediated through a specific and sterol-sensitive mechanism for suppression of transporter protein ubiquitination, which in turn decreases proteasomal degradation. This provides a mechanism for acute fine-tuning of cholesterol transporter activity in response to fluctuations in cell cholesterol levels, in addition to the longer term cholesterol-dependent transcriptional regulation of these genes.

Introduction

Cholesterol is an essential component of all mammalian cell membranes and is important for normal cell function. However, accumulation of excess cholesterol can be harmful, leading to toxicity at the cellular level and to disease states such as atherosclerosis in specific tissues. Most cells are able to actively export excess cholesterol to acceptors such as apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I)3 and HDL, the first step in the process of “reverse cholesterol transport” in which cholesterol is delivered from peripheral tissues to the liver for eventual excretion. Cholesterol export is mediated by several membrane cholesterol transporters, including ABCA1 and ABCG1. ABCA1 mediates export of cholesterol and phospholipids to lipid-poor acceptors such as apoA-I, whereas ABCG1 can mediate sterol export to lipidated acceptors such as HDL. Working together, ABCA1 and ABCG1 appear capable of mediating most cellular cholesterol export (1–3).

Cholesterol accumulation in many cells is associated with substantial increases in ABCA1 and ABCG1 mRNA and protein levels, consistent with their roles in cell cholesterol homeostasis. ABCA1 and ABCG1 mRNA expression is highly regulated at the transcriptional level, largely through nuclear liver X receptors (LXR) and retinoid X receptor. In particular, cholesterol-dependent transcription is regulated through ligand-mediated activation of liver X/retinoid X receptors, involving cell-derived intermediates such as 24,25-epoxycholesterol (4, 5) and desmosterol (6). However, the observed discordance between ABCA1 mRNA and protein levels in some tissues suggests that ABCA1 protein is also controlled by post-translational mechanisms in vivo (7). In vitro studies have confirmed that ABCA1 is highly regulated post-translationally, largely through control of its rate of degradation. ABCA1 protein turnover is reduced by exposure of cells to apolipoprotein A-I (8) and stimulated by unsaturated fatty acids (9). ABCA1 turnover is also controlled by intracellular proteins such as oxysterol-binding protein (10) and α1-syntrophin (11). Post-translational control of ABCG1 protein is less well studied, although it has been reported that 12/15-lipoxygenase activity promotes ABCG1 degradation in murine macrophages, leading to a corresponding decrease in cholesterol efflux to HDL (12, 13). We recently reported that in addition to the ubiquitously expressed ABCG1-666, humans also express ABCG1-678, another isoform (not found in rodents (14)) with an extra 12-amino acid peptide between the ABC cassette and the transmembrane region (15). When expressed separately in CHO cells, ABCG1-678 is more rapidly degraded than ABCG1-666, apparently mediated via a PKA phosphorylation site near the 12-amino acid region of ABCG1-678, which implies an extra level of complexity to the post-translational control of this transporter (16).

The atheroprotective functions of ABCA1 and ABCG1 appear to depend on their abilities to mobilize cell cholesterol. We therefore considered that cell cholesterol status might exert additional, post-translational control over their expression and activity. Excessive accumulation of unesterified cholesterol is already known to accelerate ABCA1 protein degradation (17). However, the effect of more subtle pathophysiological changes in cell cholesterol content on ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression has not been explored. In the present study, we report that modest cell cholesterol loading specifically preserves ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein levels by retarding their degradation. We provide evidence that ABCA1 and ABCG1 turnover is mediated largely by proteasomal proteolysis and that modest elevation of cell cholesterol levels is associated with a substantial reduction in their ubiquitination. We suggest that cholesterol-sensitive post-translational regulation of the turnover of these transporter proteins may represent an additional mechanism by which cells can rapidly fine-tune their cholesterol export activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Cycloheximide, tunicamycin, thapsigargin, MG132, ALLN, lactacystin, chloroquine, cholesterol, β-methyl-cyclodextrin, T-0901317, and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate were purchased from Sigma. HDL2 was isolated by ultracentrifugation as previously described (18). M-PER protein extraction reagent was purchased from Thermo Scientific, and Complete protease inhibitor tablets were from Roche. TrueBlot beads were purchased from Jomar Biosciences, and 1α,2α(n)-[3H]cholesterol was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences.

Cells

Chinese hamster ovary cell lines stably expressing either human ABCA1 (ABCA1-CHO) or human ABCG1 (ABCG1-666-CHO or ABCG1-678-CHO) were generated in our laboratory and cultured as previously described (1, 15, 19). ABCA1-CHO cells were treated for 24 h with tetracycline (1 μg/ml) to induce expression of the transporter. CHO cells stably expressing human SRBI (hSRBI-CHO) (20) were kindly provided by Prof. Dr. Bernd Engelmann (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München) and maintained under geneticin selection (Invitrogen; 0.5 mg/ml). These cells stably overexpress the ∼82-kDa glycosylated form of SRBI.

All CHO lines were ∼70% confluent at the time of experiments. THP-1 monocytes (American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% (v/v) FBS, l-glutamine (2 mm), penicillin (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). The cells were treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (50 ng/ml) for 3 days to induce differentiation to macrophages and pretreated with LXR agonist T0901317 (1 μm) for 24 h to induce expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1.

Sterol Loading

Soluble cholesterol/cyclodextrin (cholesterol/CD) complexes were prepared as previously described (21) and incubated with cells (usually at 20 μg cholesterol/ml) for up to 8 h. To measure cholesterol loading, cells were lysed in 0.2 m sodium hydroxide, then extracted, and analyzed by HPLC as previously described (22).

Western Blotting

Cells were lysed in M-PER containing Complete protease inhibitors and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis as previously described (1, 19). The antibodies used were ABCG1, rabbit polyclonal (Novus, 1:2500); ABCA1, rabbit polyclonal (Novus, 1:1000)) or mouse monoclonal (Life Research; 1:2500 or Abcam 1:2500); EEA1, rabbit polyclonal (Upstate, 1:2000); Na+/K+ ATPase α-1, mouse monoclonal (Upstate,1:10,000); SR-BI, rabbit polyclonal (Novus 400-104, 1:2500); transferrin receptor, mouse monoclonal (Invitrogen, 1:700) α-tubulin, mouse monoclonal (Sigma, 1:10,000); and ubiquitin, mouse monoclonal (Covance, 1:5000). Protein detection was by chemiluminescence (ECL®; Amersham Biosciences), and quantitation of protein bands was performed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health).

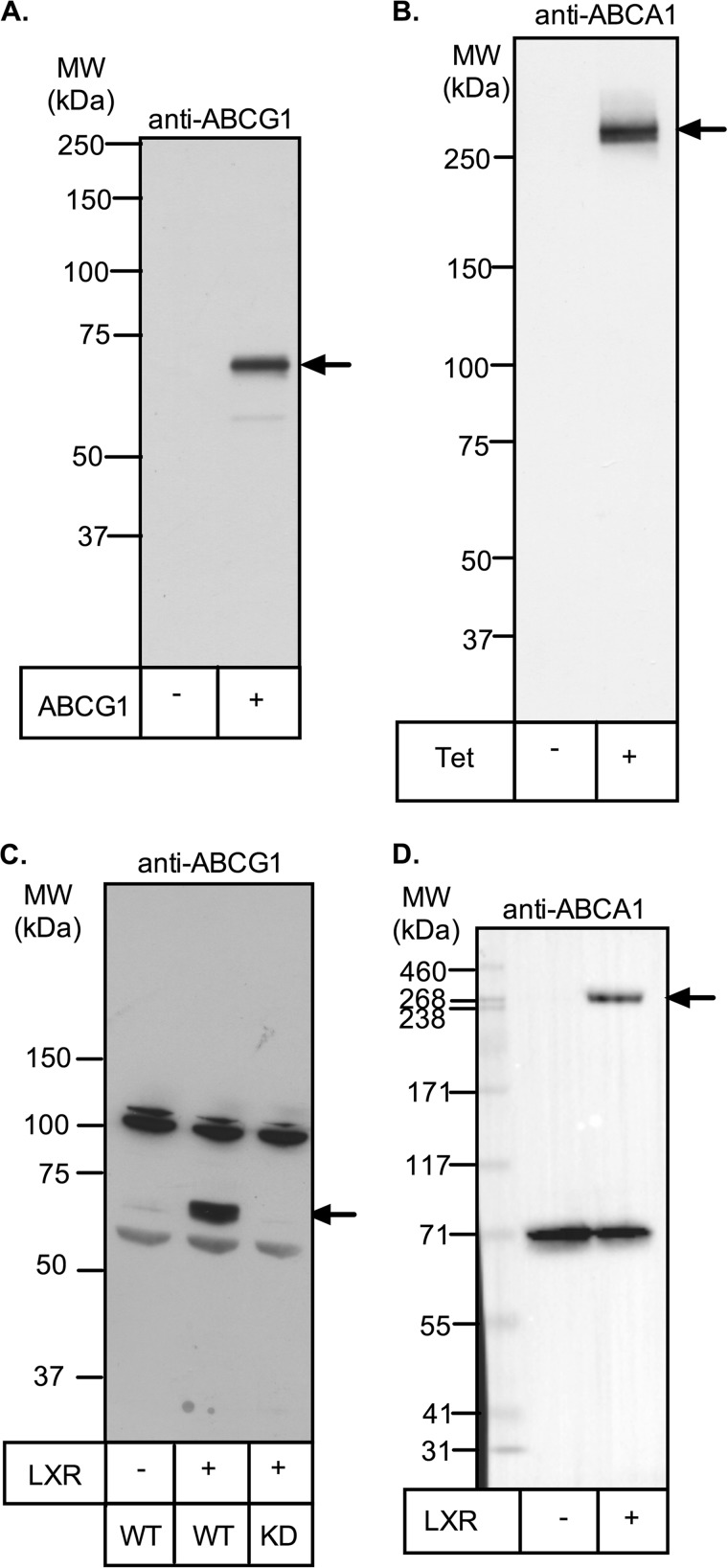

Representative full-length Western blots of ABCA1 and ABCG1 are shown in Fig. 1. Human ABCG1 has an apparent molecular mass of 67 kDa and is the single protein detected in ABCG1-CHO cells, consistent with previous reports in this (1) and other cell types, including THP-1 macrophages (23–25). In THP-1 macrophages, we found that expression of the 67-kDa band is strongly up-regulated by preincubation with T0901317 but is lost when ABCG1 is stably silenced (19). Other nonspecific protein bands are also detected in THP-1 macrophages, but they are not altered by LXR induction or silencing. Human ABCA1 has an apparent molecular mass of ∼260 kDa in both ABCA1-CHO cells and THP-1 macrophages, consistent with other reports (8, 26). It is the major protein detected in tetracycline-induced ABCA1-CHO cells but is not seen when tetracycline is omitted. In THP-1 cells, another protein of ∼70 kDa was detected but was unaffected by LXR induction. In all THP-1 blots, control lysates with or without LXR induction were included, and only the LXR-sensitive 67- and ∼260-kDa bands were used to quantitate ABCG1 and ABCA1 expression, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Detection of ABCA1 and ABCG1 by Western blot. A, cell lysate (10 μg of protein) from CHO cells stably expressing ABCG1-678 was separated by SDS-PAGE (7% Tris acetate gel) and subjected to Western blotting for ABCG1 (Novus rabbit polyclonal antibody; 1:2500) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, ABCA1-CHO cells were preincubated overnight with or without tetracycline (1 μg/ml) to induce ABCA1 expression. Cell lysates (30 μg of protein) were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Western blotting for ABCA1 (Life Research mouse monoclonal; 1:2500) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” C and D, THP-1 cells were preincubated for 24 h with (second lane) or without (first lane) T0901317 (1 μm) to induce ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression. Cell lysates (15 μg of protein) were then separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Western blotting for either ABCG1 (Novus rabbit polyclonal antibody; 1:2000; C) or ABCA1 (Novus rabbit polyclonal antibody; 1:2000; D) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Positions of molecular mass markers are shown, and arrows indicate the bands of ABCA1 or ABCG1. KD, THP-1 cell clone in which ABCG1 is stably silenced (19). MW, molecular mass.

ABCA1 and ABCG1 Immunoprecipitation and Detection of Ubiquitination

Cells were incubated for 8 h in medium containing 0.5% (v/v) FBS, MG-132 (10 μm) with or without cholesterol/CD (20 μg of cholesterol/ml), and then lysed in M-PER containing Complete protease inhibitors. For ABCG1 cells, equal amounts of protein (1–2 mg) were precleared and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-rabbit beads (TrueBlot) and rabbit polyclonal anti-ABCG1 (Novus). The beads were washed and heated in sample buffer at 100 °C for 5 min, and then the proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by immunoblotting. For ABCA1 cells, the protocol used anti-mouse beads (TrueBlot) and mouse monoclonal anti-ABCA1 (Life Research).

Cholesterol Efflux

Cells were preloaded with [3H]cholesterol for 24 h and then incubated with or without unlabeled cholesterol/CD (20 μg cholesterol/ml) for 8 h. The cells were then washed, equilibrated for 30 min in serum-free medium, and incubated in fresh medium containing 0.1% (w/v) BSA ± HDL2 (10 μg protein/ml) for 4 h. Samples of cells and media were collected and counted for radioactivity. Efflux of [3H]cholesterol into the medium was calculated as a percentage of the total radioactivity (cells + medium) in the system. ABCG1-specific efflux to HDL was calculated as the difference in percentage efflux between CHO cells expressing ABCG1-678 and nontransfected CHO cells; ABCA1-specific efflux was calculated as the difference in efflux rates between ABCA1-CHO cells with or without tetracycline induction.

Data Analysis

Experimental kinetic data were fitted to a first order rate equation using a nonlinear least squares fitting program (Prism). Comparison of two groups used a Student's t test (Prism). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Influence of Cell Cholesterol Status on ABCG1 Protein Expression

Our previous observation of a difference in the relative stabilities of ABCG1-678 and ABCG1-666 led us to further examination of factors affecting ABCG1 protein expression, including cellular cholesterol status. To achieve this, CHO cells stably expressing either isoform were transferred from normal growth medium (10% FBS) to either low cholesterol medium (0.5% FBS) or cholesterol-enriched medium (0.5% FBS supplemented with soluble cholesterol/cyclodextrin complex (20 μg cholesterol/ml) for up to 8 h.

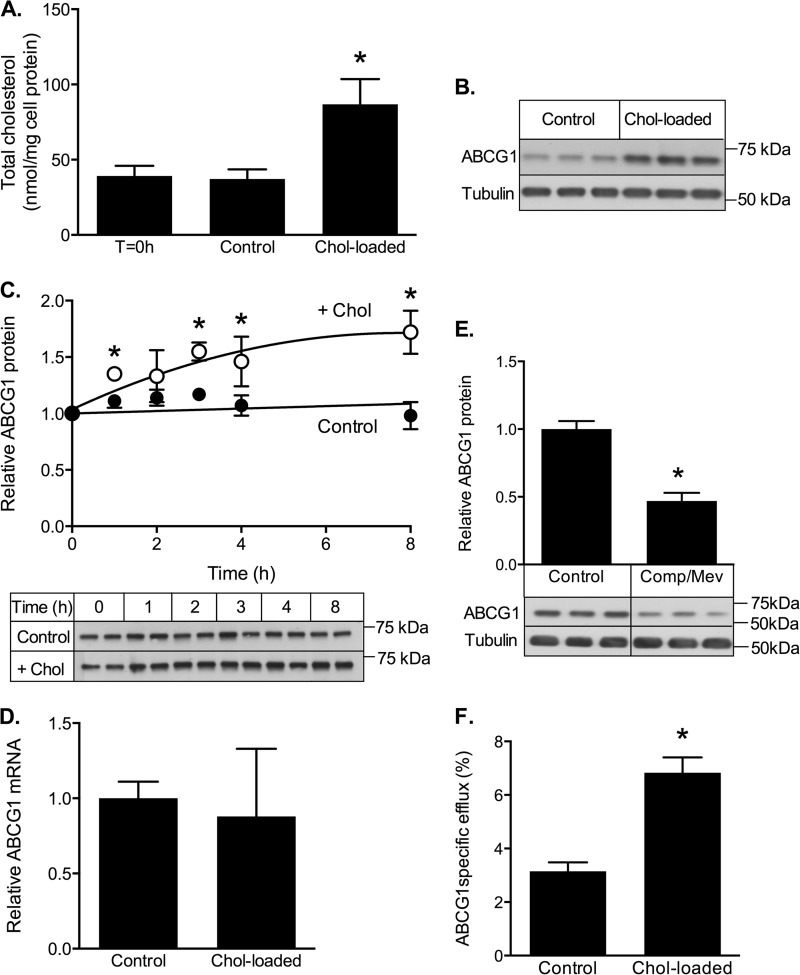

The effects of this treatment on ABCG1-678 are shown in Fig. 2. The addition of cholesterol to the medium increased the cell cholesterol level >2-fold over this period, whereas there was no significant change in control (low cholesterol medium) cells (Fig. 2A). In both basal and cholesterol-loaded conditions ∼20% of cholesterol was esterified (data not shown). Cholesterol loading resulted in significantly higher ABCG1 protein levels, relative to the nonloaded cells (Fig. 2B), and significant differences between the groups could be detected as early as 1 h after the addition of cholesterol (Fig. 2C). CHO cells express very low levels of endogenous ABCG1, the constitutive expression of human ABCG1 in these cells is driven by a cytomegalovirus promoter (which is insensitive to cholesterol), and we confirmed that ABCG1 transcription was unaffected under these conditions (Fig. 2D). Thus cholesterol loading most likely increases ABCG1 protein levels by a post-transcriptional mechanism. Conversely, depletion of cell cholesterol by inhibition of cholesterol synthesis using compactin/mevalonate (Fig. 2E) or by treatment with 0.2% (w/v) cyclodextrin (data not shown) was associated with reduced ABCG1 protein, relative to controls. The increased ABCG1 protein level in cholesterol-loaded cells was associated with increased ABCG1-dependent cholesterol efflux to HDL (Fig. 1F).

FIGURE 2.

ABCG1 response to cholesterol loading. CHO cells stably expressing ABCG1-678 were incubated for up to 8 h in either low cholesterol (control) medium (0.5% FBS; control) or cholesterol-enriched medium (0.5% FBS supplemented with cholesterol/CD (20 μg cholesterol/ml; Chol-loaded). A, cholesterol content of cells before (T = 0 h) and after incubation for 8 h with or without cholesterol. The data are means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. B, Western blot showing cellular ABCG1 protein after 8 h with or without cholesterol. C, time course of ABCG1 protein expression during incubation with (white circles) or without (black circles) cholesterol. The data are means ± S.D. of six independent experiments. Representative Western blots from a single experiment are shown. D, ABCG1 mRNA levels measured after 8 h of incubation with or without cholesterol. The data are means ± half-range of two separate experiments. E, ABCG1 protein after 8 h of incubation without (Control) or with (Comp/Mev) compactin (5 μm) plus mevalonate (50 μm). F, ABCG1-dependent [3H]cholesterol efflux after preloading cells with or without unlabeled cholesterol. For E and F, the data are means ± S.D. of triplicate cultures in a single experiment. *, p < 0.05 relative to control cells.

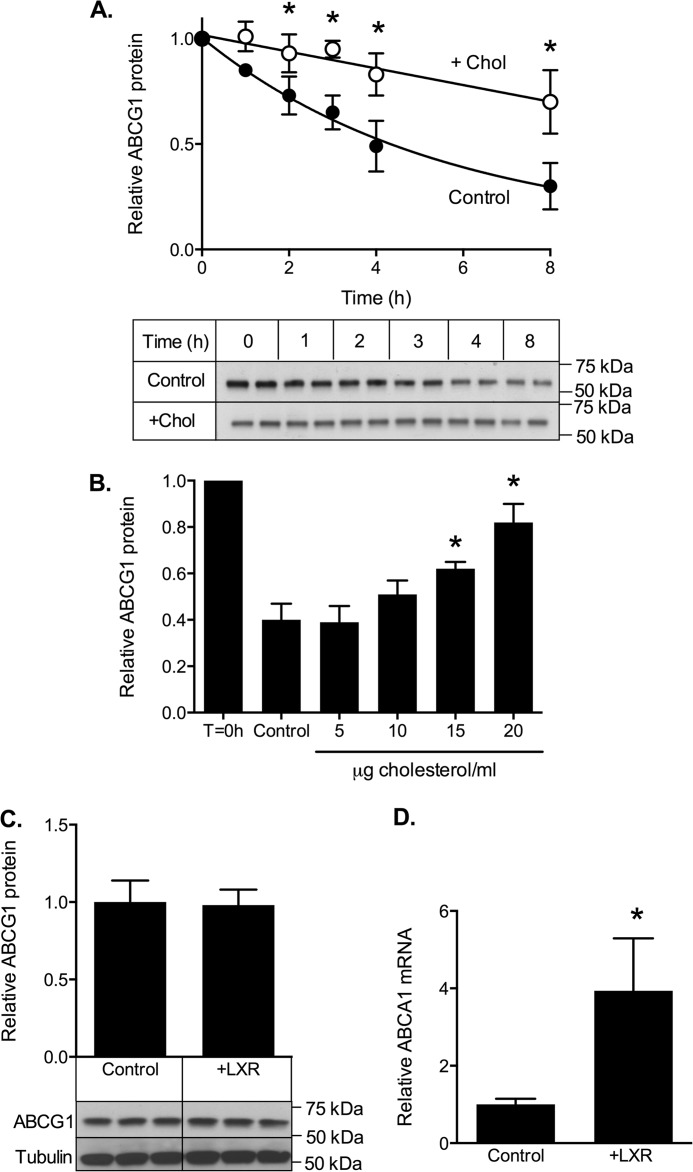

ABCG1 protein levels reflect a balance between cellular synthesis and degradation. To test whether cholesterol loading raised ABCG1-678 protein levels by inhibiting its degradation, cells were incubated with or without cholesterol in the presence of cycloheximide to block further protein synthesis (Fig. 3A). Under these conditions, any changes in ABCG1 protein levels reflect an altered rate of degradation. Initial studies established that cell viability was not affected by these conditions (data not shown). In control cells, ABCG1-678 protein levels decreased by ∼70% over 8 h (first order decay constant, k = 0.157 ± 0.012 h−1), whereas the addition of cholesterol decreased the rate of ABCG1-678 degradation 3-fold (k = 0.046 ± 0.008 h−1). To exclude possible off target effects of cycloheximide, in separate experiments we also measured the effect of cholesterol loading on ABCG1 turnover using pulse-chase decay after labeling with [35S]methionine/cysteine. In these experiments (data not shown), cholesterol loading caused a similar decrease in the rate of ABCG1 loss, further confirming that cholesterol loading retards ABCG1 protein degradation.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of cholesterol on ABCG1-678 degradation. A, ABCG1-678-CHO cells were incubated for the indicated times in medium containing 0.5% (v/v) FBS and cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) in the presence (white circles) or absence (black circles) of cholesterol (Chol)/CD (20 μg cholesterol/ml). The data are means ± S.D. of six independent experiments. Representative Western blots from a single experiment are shown below. B, cells were either harvested immediately (T = 0 h) or were incubated for 8 h in medium containing 0.5% (v/v) FBS and cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) plus the indicated concentrations (μg/ml) of cholesterol. The data are means ± half-range of two independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. C and D, CHO-ABCG1-678 cells were incubated for 8 h ± T-0901317 (1 μm) and then analyzed for ABCG1 protein (C) or ABCA1 mRNA (D). The data are means ± S.D. of a single experiment (C, n = 3; D, n = 6). *, p < 0.05 relative to control cells.

The effect of cholesterol on ABCG1-678 protein degradation was time-dependent (Fig. 3A) and dose-dependent (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, a synthetic LXR ligand had no effect on ABCG1 protein (Fig. 3C) under conditions where its activity on endogenous gene expression was strongly stimulated (for example, ABCA1 mRNA; Fig. 3D), indicating that cholesterol loading does not affect ABCG1 turnover through an LXR-dependent mechanism.

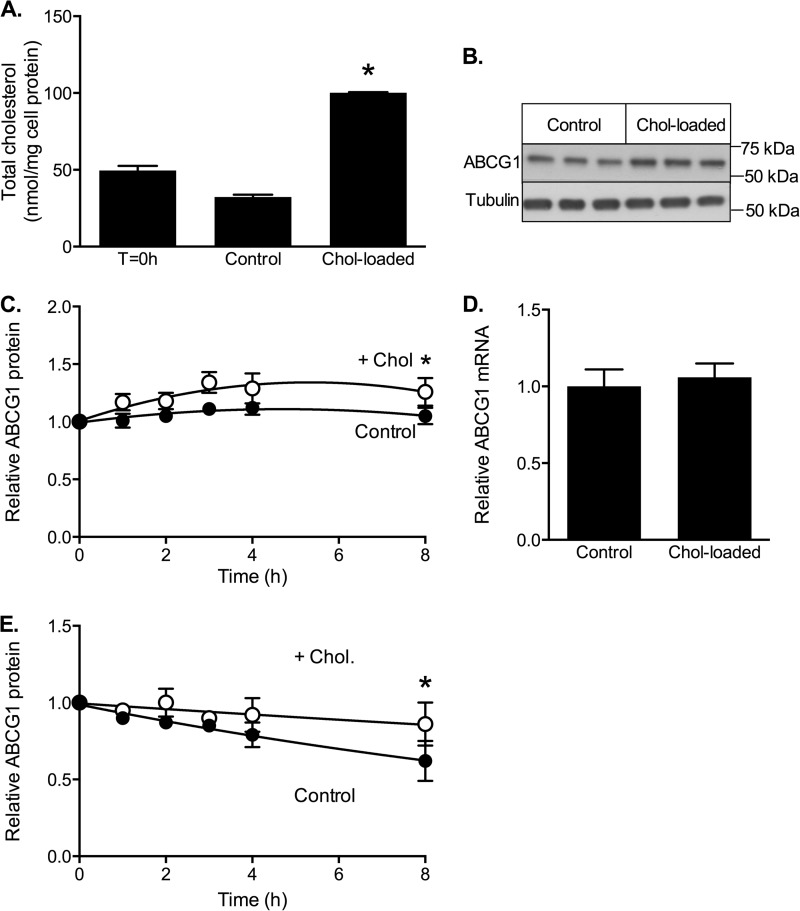

The effects of cholesterol loading on ABCG1-666 protein stability was also measured using ABCG1-666-CHO cells (Fig. 4). We previously reported that the turnover of ABCG1-666 is significantly slower than ABCG1-678, suggesting that the 12-amino acid segment influences ABCG1 degradation (15, 16). We were therefore interested to know whether the effect of cholesterol on ABCG1-678 was mediated through this sequence. Here we again confirmed that the degradation of ABCG1-666 is slower than that of ABCG1-678 (Fig. 3A versus Fig. 4E). However, ABCG1-666 was also stabilized by cholesterol loading (k = 0.058 ± 0.007 without cholesterol h−1 versus 0.019 ± 0.007 h−1 with cholesterol), suggesting that the PKA phosphorylation site in the 12-amino acid segment is not responsible for the effects seen here and that cholesterol-dependent regulation of degradation acts similarly on both isoforms.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of cholesterol on stability and degradation of ABCG1-666. CHO cells stably expressing ABCG1-666 were incubated for up to 8 h in either low cholesterol (control) medium (0.5% (v/v) FBS) or cholesterol-enriched medium (0.5% FBS supplemented with cholesterol/CD (20 μg cholesterol/ml)) (Chol-loaded). A, cholesterol content of cells before (T = 0 h) and after incubation for 8 h with or without cholesterol. The data are means ± S.D. of triplicate measurements in a single representative experiment. B, Western blot showing cellular ABCG1 protein after 8 h with or without cholesterol. C, time course of ABCG1 protein expression during incubation with (white circles) or without (black circles) cholesterol. The data are means ± S.D. of five independent experiments. D, ABCG1 mRNA levels measured after 8 h of incubation with or without cholesterol. The data are means ± half-range of two separate experiments, each performed in triplicate. E, decline in ABCG1 protein after addition of cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) in the presence (white circles) or absence (black circles) of cholesterol. The data are means ± S.D. of five independent experiments. *, significant difference (p < 0.05) relative to control cells.

Influence of Cell Cholesterol Status on ABCA1 Protein Expression

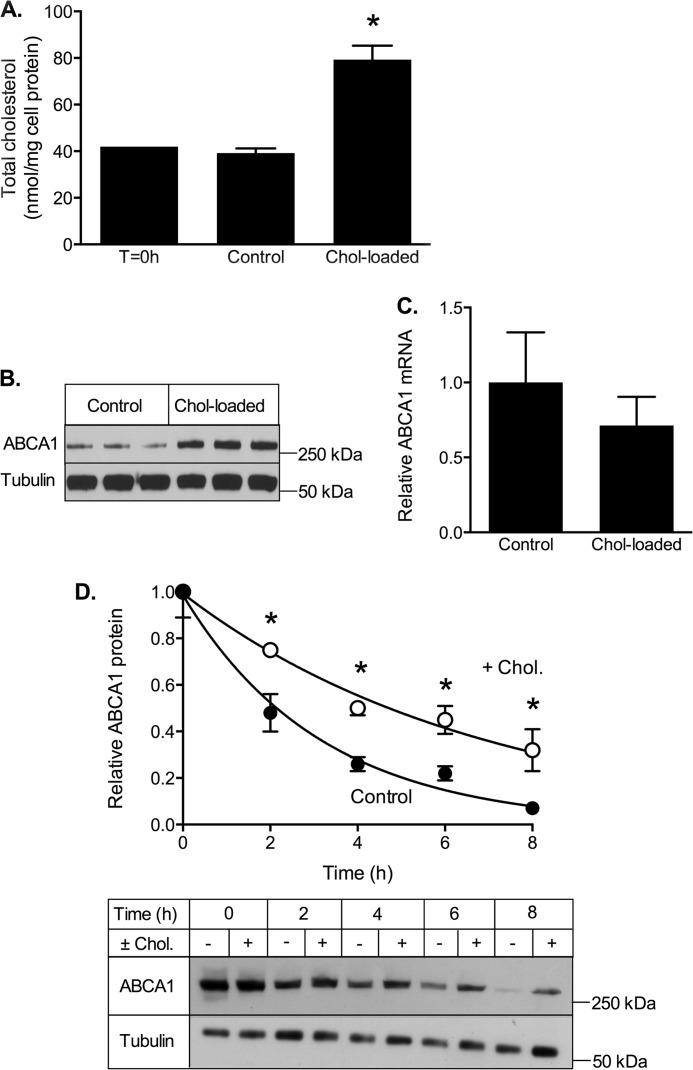

To determine the selectivity of the effects of cholesterol on ABCG1 turnover, we also examined the effect of cholesterol on ABCA1 stability (Fig. 5) using CHO cells stably expressing human ABCA1 under a tetracycline-inducible promoter (19). Exposure to cholesterol/CD increased cell cholesterol ∼2-fold (Fig. 5A), similar to ABCG1-CHO cells (Figs. 2A and 4A). This was associated with increased ABCA1 protein in the cholesterol-treated cells (Fig. 5B), without significantly altering ABCA1 mRNA expression (Fig. 5C). Similar to results for ABCG1, cholesterol loading also significantly reduced the rate of ABCA1 degradation (k = 0.316 ± 0.018 h−1 versus 0.145 ± 0.009 h−1; Fig. 5D). This reflected a cholesterol-dependent increase in the half-life of ABCA1 (measured in the presence of cycloheximide) from 2.7 ± 0.3 to 5.1 ± 0.7 h (mean ± S.D.; n = 4 independent experiments). Thus cholesterol loading regulates the turnover of both ABCA1 and ABCG1 proteins in CHO cells expressing these transporters.

FIGURE 5.

ABCA1 response to cholesterol loading. CHO cells stably expressing ABCA1 were incubated for up to 8 h in either low cholesterol (control) medium (0.5% FBS) or cholesterol-enriched medium (0.5% (v/v) FBS supplemented with cholesterol/CD (20 μg cholesterol/ml) (Chol-loaded). A, cholesterol content of cells before (T = 0 h) and after incubation for 8 h with or without cholesterol. The data are means ± S.D. of a single experiment (n = 3). B, Western blot showing cellular ABCA1 protein after 8 h with or without cholesterol. C, ABCA1 mRNA levels measured after 8 h of incubation with or without cholesterol. The data are means ± S.D. of a single experiment (n = 6). D, cells were incubated for the indicated times with medium containing 0.5% FBS and cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) in the presence (white circles) or absence (black circles) of cholesterol/CD (20 μg cholesterol/ml). The data are means ± S.D. (n = 6) of a single experiment representative of four independent experiments. A representative Western blot from a single experiment is shown below. *, p < 0.05 relative to control cells.

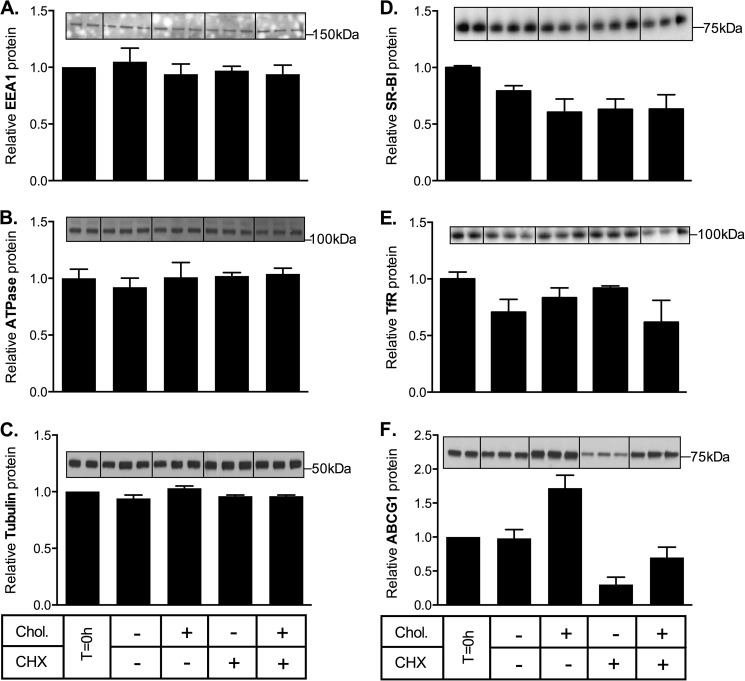

To determine whether the effects of cholesterol loading on ABCA1 and ABCG1 turnover were specific for these transporters, the impact of cholesterol loading on endogenous levels of other cell proteins (Na+/K+ ATPase, EEA1, and α-tubulin) was measured in ABCG1-678-CHO cells. Na+/K+ ATPase is a transmembrane electrogenic ATPase located in the plasma membrane, EEA1 is a hydrophilic peripheral membrane protein associated with early endosomes, whereas α-tubulin is a globular cytosolic protein involved in microtubule formation. In addition, we measured the levels of human SR-BI and endogenous transferrin receptor in CHO cells stably overexpressing SR-BI. Transferrin receptor is a dimeric transmembrane protein involved cellular uptake of transferrin, and SR-BI is a cell surface membrane glycoprotein involved in selective uptake of cholesteryl esters from high density lipoprotein. None of these proteins were affected by cholesterol loading (Fig. 6). This suggests that the effects of cholesterol on ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein turnover are relatively selective, although further studies are required to determine whether this mechanism also applies to other proteins subject to rapid regulation of expression through protein turnover.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of cholesterol loading on other cell proteins. ABCG1-678-CHO cells were incubated for 8 h in medium containing 0.5% (v/v) FBS with or without cholesterol/CD (Chol, 20 μg cholesterol/ml) and with or without cycloheximide (CHX, 10 μg/ml). A–C and F, Na/K-ATPase (A), EEA1 (B), α-tubulin (C), and ABCG1 (F) were measured in cell lysates by Western blot. D and E, in a separate experiment, SR-BI-CHO cells were treated identically and blotted for transferrin receptor (D) and SR-BI (E). The data for each protein are expressed relative to its starting level (T = 0 h) and are means ± S.D. of triplicate determinations from single representative experiments.

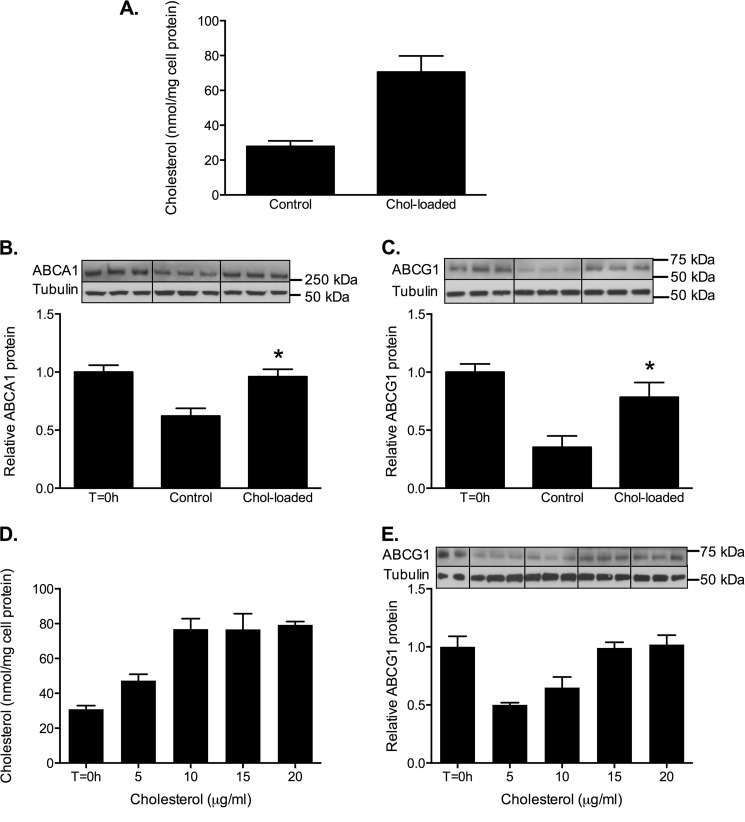

Cholesterol Loading Inhibits Degradation of ABCG1 and ABCA1 in Human Macrophages

To determine that there was an inhibitory effect of cholesterol loading on the degradation of endogenously expressed ABCG1 and ABCA1, we examined their stability in human THP-1 macrophages. Basal expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 mRNA in these cells is low (15, 19), so the cells were preincubated with an LXR agonist (T-0901317) for 24 h to stimulate transporter expression before exposure with or without cholesterol for 8 h in the presence of cycloheximide. Enrichment with cholesterol increased cell cholesterol levels 2–3-fold (Fig. 7A). The degradation of both ABCA1 (Fig. 7B) and ABCG1 (Fig. 7C) was retarded by cholesterol loading, and the effect was dose-dependent (Fig. 7, D and E). Because cycloheximide blocks de novo protein synthesis, the observed effects of cholesterol on protein levels are independent of any direct effects of cholesterol loading on gene transcription. Thus the turnover of endogenous, as well as overexpressed, ABCA1 and ABCG1 proteins are sensitive to cell cholesterol loading.

FIGURE 7.

Cholesterol loading preserves ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein in human macrophages. THP-1 macrophages were treated for 24 h with T-0901317 (1 μm) and then incubated for 8 h in medium containing cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) with or without cholesterol/CD (20 μg cholesterol/ml). A, cholesterol content at 8 h (mean ± S.D. of three separate experiments). B and D, ABCA1 (B) and ABCG1 (C) levels at 8 h were measured by Western blot. The data are means ± S.D. (n = 3) from a single experiment, representative of four. *, p < 0.05 compared with nonloaded (control) cells. Representative Western blot images are shown. D and E, dose-dependent cholesterol loading (D) and ABCG1 protein levels (E) when THP-1 macrophages were incubated as above with the indicated concentrations of cholesterol. The data are means ± S.D. (n = 3) from a single experiment.

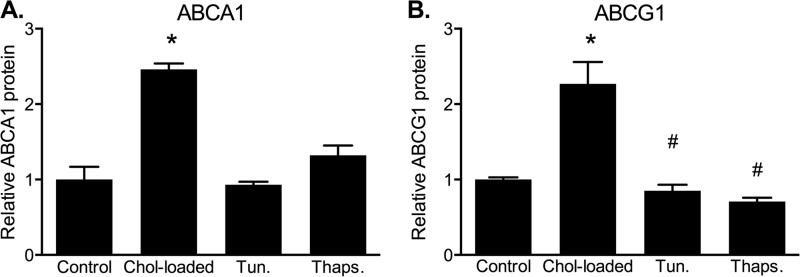

Role of Cholesterol-induced ER Stress in ABCA1 and ABCG1 Stability

It has been shown in mouse macrophages that conditions that stimulate cholesterol trafficking to the ER in mouse macrophages lead to ER stress and are associated with accelerated degradation of ABCA1 (17). Although we observed retarded, rather than accelerated, degradation of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in response to cholesterol loading, we examined the possibility that this was related to cholesterol-induced ER stress. The effects of cholesterol loading or exposure to the ER stressors tunicamycin and thapsigargin on ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein levels were compared in CHO cell lines (Fig. 8). Under similar conditions, we previously demonstrated that this treatment of CHO cells with tunicamycin or thapsigargin strongly induced several markers of ER stress (expression of GADD4 and phosphorylation of IRE1α and eIF2α), whereas cholesterol loading had relatively little effect (27). In the present study, neither tunicamycin nor thapsigargin were able to reproduce the effect of cholesterol loading on ABCA1 or ABCG1 stability. A slight increase in ABCA1 was observed in cells treated with thapsigargin, but this did not reach significance (p = 0.06 relative to control). In contrast, ABCG1 protein was slightly but significantly decreased by both tunicamycin (p = 0.038) and thapsigargin (p = 0.001). This indicates that an ER stress response is unlikely to mediate the increased stability of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in cholesterol-loaded cells.

FIGURE 8.

Effects of ER stress inducers on ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein levels. A and B, ABCA1-CHO cells (A) or ABCG1-678-CHO cells (B) were incubated in medium (0.5% (v/v) FBS) containing cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) plus either; no addition (Control), cholesterol (Chol-loaded)/CD (20 μg cholesterol/ml), tunicamycin (5 μg/ml, Tun.), or thapsigargin (250 nm, Thaps.) for 6 h. ABCA1 and ABCG1 were measured by Western blot. The data are expressed relative to control and are means ± S.D. (n = 3). *, significantly higher than control cells; #, significantly lower than control cells (both p < 0.05).

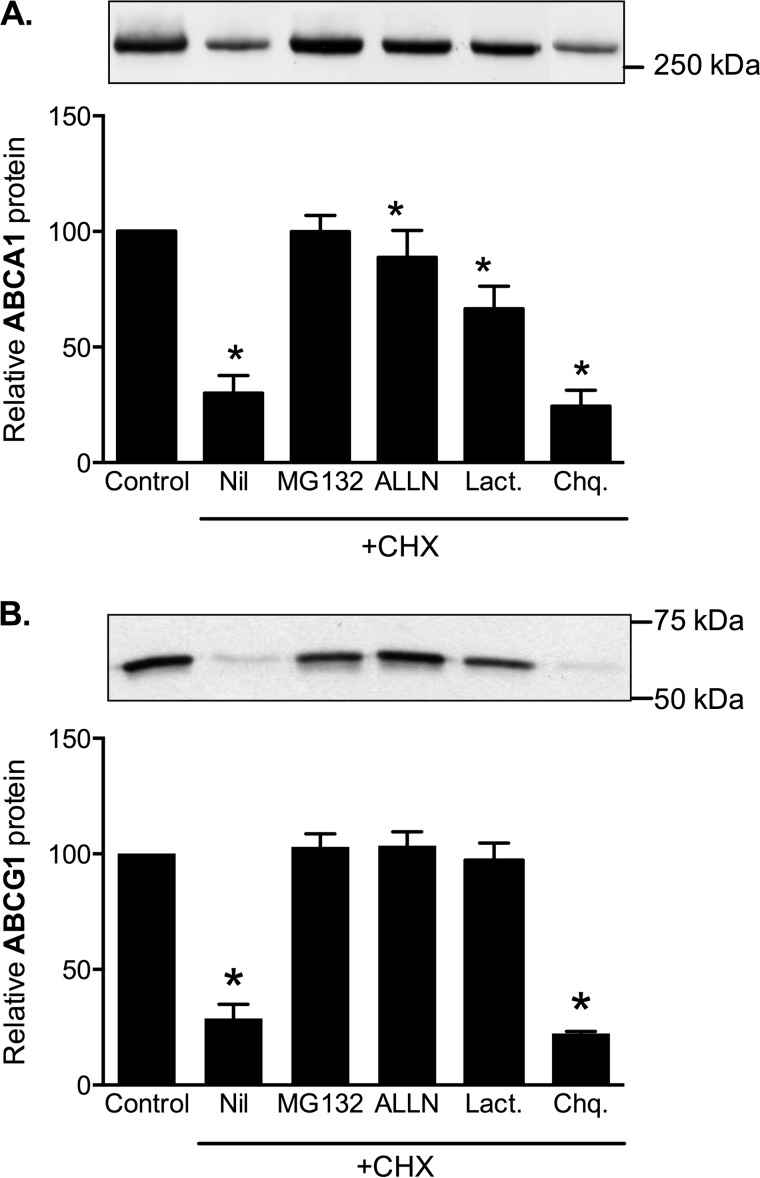

Mechanism of ABCG1 and ABCA1 Protein Degradation

Earlier studies have shown that proteasomal and calpain inhibitors block degradation of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in mouse and human macrophages (13, 23, 25, 28). We confirmed that degradation of ABCA1 and ABCG1 was completely inhibited by protease inhibitors MG132 and ALLN in CHO cells (Fig. 9) and in THP-1 macrophages (data not shown). At the concentrations used, these are effective inhibitors of both proteasomal and calpain-mediated proteolysis. We therefore also measured the effect of lactacystin, a more specific proteasomal inhibitor (29). We found that lactacystin partially inhibits ABCA1 degradation, although not as efficiently as MG132 and ALLN, which is consistent with previous reports that calpain contributes to ABCA1 degradation independently of the proteasome (28). In contrast, lactacystin inhibited ABCG1 degradation almost as efficiently as MG132 and ALLN, indicating that calpain probably makes little contribution to ABCG1 degradation. Lysosomal protease inhibitors chloroquine (Fig. 9) and ammonium chloride (data not shown) were ineffective.

FIGURE 9.

ABCA1 and ABCG1 sensitivity to protease inhibitors. A and B, ABCG1-678 CHO cells (A) or ABCA1-CHO cells (B) were incubated for 8 h in medium (0.5% (v/v) FBS) without (Control) or with (all other conditions) cycloheximide (CHX, 10 μg/ml) together with the inhibitors. Nil, no addition, MG132 (10 μm), ALLN (100 μg/ml), lactacystin (Lact., 10 μm), or chloroquine (Chq., 100 μm). ABCG1 and ABCA1 were measured in cell lysates by Western blotting, and the data are presented relative to the level in untreated control cells. Representative Western blot images are shown. The data are means ± S.D. of triplicate samples from single representative experiments. *, significantly (p < 0.05) different to control condition.

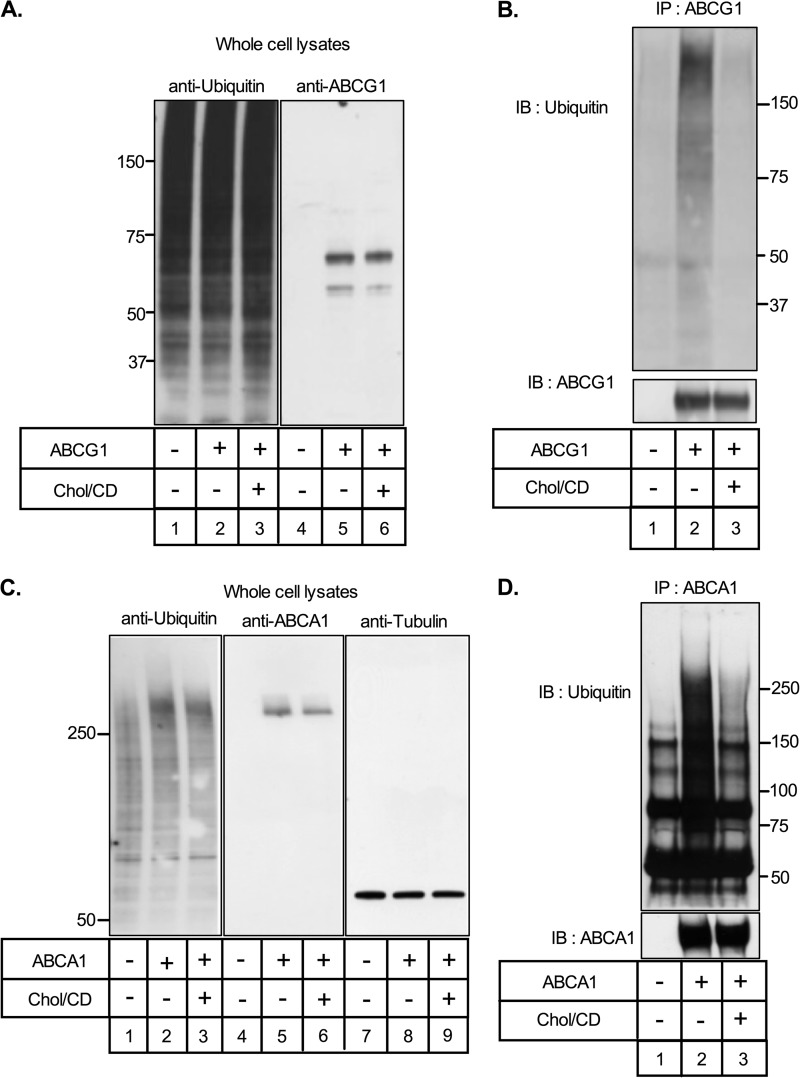

Proteins are targeted for proteasomal degradation by the covalent attachment of ubiquitin molecules to lysine residues, and proteasomal inhibitors lead to the accumulation of ubiquitinated ABCA1 and ABCG1 (23). To determine whether cholesterol loading changed the ubiquitination status of ABCG1, ABCG1-678-CHO cells were incubated in the presence of MG132 with or without cholesterol/CD. MG-132 completely blocks proteasomal degradation of ABCG1 (Fig. 9B) so that ubiquitinated protein will accumulate. As expected, under these conditions cellular ABCG1 protein levels were similar in the presence or absence of cholesterol loading (Fig. 10A, lanes 5 and 6). Overall cell protein ubiquitination was not altered by expression of ABCG1 (Fig. 10A, lanes 1 versus lanes 2 and 3) or by cholesterol loading (Fig. 10A, lanes 1 and 2 versus lane 3). Cell lysates then were immunoprecipitated using an antibody against ABCG1, and the products were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted for ubiquitin and ABCG1 (Fig. 10B). Significantly, the extent of ABCG1 ubiquitination was strongly repressed by cholesterol loading (Fig. 10B, lane 2 versus lane 3).

FIGURE 10.

Cholesterol-sensitive ubiquitination of ABCA1 and ABCG1. A, control (lanes 1 and 4) and ABCG1-678-expressing (lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6) CHO cells were incubated for 8 h in medium (0.5% (v/v) FBS) containing MG132 (10 μm) with or without cholesterol/CD (20 μg/ml). Whole cell lysates (10 μg protein) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted (IB) for ubiquitin (left panel) or ABCG1 (right panel). B, samples of the same cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-ABCG1, followed by immunoblotting with an anti-ubiquitin antibody (upper panel). The blots were then reprobed with anti-ABCG1 (lower panel). Molecular weight markers are shown. C and D, results for ABCA1 using ABCA1-CHO (lanes 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, and 9) and control (lanes 1, 4, and 7) cells and conditions as for A and B, except that Western blots for tubulin are also shown in C (lanes 7–9).

Similar results were obtained for ABCA1 (Fig. 10, C and D). Taken together, these data indicate that ABCA1 and ABCG1 are degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and that their ubiquitination and subsequent degradation are inhibited by cholesterol loading.

DISCUSSION

Maintenance of cholesterol homeostasis is essential for normal cell function. Removal of excess cholesterol is achieved through apoA-I and HDL-mediated export, which requires the activity of membrane transporters such as ABCA1 and ABCG1 (30–32). However, cholesterol is an essential component of all cell membranes, and so its export must be closely regulated. It is therefore logical that both ABCA1 and ABCG1 are sterol-sensitive genes whose expression is closely regulated at the transcriptional level. In addition, post-translational regulation of these transporters is now recognized as an additional important mechanism for the control of their activity in many tissues (7). In the present study, we investigated the influence of cell cholesterol status on ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein expression and demonstrated that modest increases in cell cholesterol exert a rapid and positive effect on transporter protein levels and activity. Increases in ABCG1 protein were detected as rapidly as 1 h after cholesterol addition, suggesting that this may represent a significant mechanism for acute regulation of cholesterol transporter activity in response to fluctuations in cell cholesterol levels. To our knowledge, this is the first report of cholesterol-dependent post-translational control of ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein levels.

In a recent study, we observed that two isoforms of human ABCG1 are degraded at different rates under basal conditions (15). These isoforms differ only by a 12-amino acid cytoplasmic domain, which is associated with a 2–3-fold difference in their rates of degradation (15). In the present study, we observed that the turnover of both ABCG1 isoforms was altered by cholesterol loading, indicating that this mechanism is common to both isoforms and therefore distinct from the isoform-specific control of ABCG1 turnover. Because turnover of ABCA1 protein is similarly regulated by cholesterol loading, this suggests that cholesterol-dependent suppression of transporter degradation may be mediated by factors common to both ABCA1 and ABCG1. Whether other membrane proteins involved in cholesterol homeostasis are also affected by this mechanism is currently unknown. It is noteworthy that we demonstrated that several other, unrelated, membrane-associated proteins (Na/K-ATPase, EEA1, transferrin receptor, and SR-BI) were not affected by cellular cholesterol enrichment.

A previous study showed that LXR-β can interact directly with ABCA1 protein, to retard its degradation (33). We consider it unlikely that a similar mechanism underlies the cholesterol-sensitive regulation of ABCG1 degradation that we observed here. First, in the above study addition of the synthetic LXR ligand T0901317 disrupted the interaction between ABCA1 and LXR-β leading to accelerated degradation of ABCA1, whereas under similar conditions we found no effect of this LXR ligand on ABCG1 degradation (Fig. 3C). Second, this model predicts that cholesterol loading and associated increases in endogenous oxysterol LXR ligands would accelerate transporter degradation rather than inhibit degradation of both ABCA1 and ABCG1 as we observed.

Several cellular mechanisms are involved in degradation of membrane proteins, which is complex because different parts of the protein are on opposite sides of the membrane. Endoplasmic reticulum membrane proteins can be extracted from their membrane back into the cytoplasm (retrotranslocation), where they are ubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome (34). This mechanism is used to degrade proteins that are incorrectly folded in the ER or lack other appropriate post-translational modifications, as well as to short-lived proteins that are rapidly degraded when not needed. In contrast, plasma membrane proteins can be collected in vesicles formed through invagination and vesiculation of regions of the plasma membrane containing the protein, creating vesicles within endosomes (35). Fusion of these endosomes with lysosomes leads to complete degradation of the vesicular membrane and its proteins. Ubiquitination also participates in this process by signaling the targeting of specific proteins through this process (36).

Cholesterol-sensitive protein turnover is already known to occur by both of these mechanisms. For example, the rates of proteasomal degradation of several integral ER proteins involved in cholesterol synthesis and metabolism (HMG-CoA reductase, squalene monooxygenase, and the precursors of SREBP-1 and -2) are accelerated in response to cholesterol accumulation (37–39). Conversely, accelerated degradation of the LDL receptor in response to cholesterol accumulation occurs by ubiquitin-targeted lysosomal degradation, mediated by LXR-sensitive expression of Idol, an E3 ligase (40).

It is already known that ABCA1 and ABCG1 can be degraded by proteasomal mechanisms (13, 23, 41, 42), and this was confirmed in the present study, where degradation of both ABCA1 and ABCG1 was completely inhibited by proteasomal inhibitors, whereas lysosomal inhibitors were ineffective. This indicates that this process occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and involves retrotranslocation. Proteins are usually targeted for proteasomal degradation by covalent addition of polyubiquitin chains. Normally the specificity of protein ubiquitination is determined by ubiquitin ligases (E3), a diverse class of enzymes that catalyzes transfer of ubiquitin to specific target proteins. Our data provide evidence that ABCA1 and ABCG1 proteins are ubiquitinated and that this is strongly suppressed by cholesterol loading. Moreover, cholesterol loading did not further increase cellular levels of ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein in the presence of proteasomal inhibitors. This suggests that the cholesterol-dependent increase in ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein is mediated through reduced ubiquitination of these proteins and thus decreased proteasomal degradation. At the present time the specific mechanism by which cholesterol controls ubiquitination of ABCA1 and ABCG1 is not known. Cholesterol loading did not affect overall protein ubiquitination in our system, suggesting that it may involve a relatively specific cholesterol-sensitive E3 ligase or deubiqitinating enzyme. Recently, it was suggested that ABCA1 ubiquitination and proteolysis are controlled by the COP9 signalosome, and it would be interesting to determine whether this entity is cholesterol-sensitive (42). Several E3 ligases are known to exert cholesterol-dependent effects on the turnover of other membrane proteins (38, 39, 43–45). Further study is required to define the exact processes that change in response to cell cholesterol status to control ABCA1 and ABCG1 turnover.

Ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation are known to control the turnover of several other ABC transporters, including the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (ABCC7) (46) and the breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) (47). However, in these cases accelerated degradation is associated with mutated forms of these proteins and likely involves endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation, a cellular pathway that targets misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum for ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation (48). An endoplasmic reticulum surveillance system, the “unfolded protein response” continuously monitors and coordinates the processing and degradation pathways for unfolded proteins. Interestingly, the unfolded protein response is also activated by very high levels of free (unesterified) cellular cholesterol, such as that found in macrophages following uptake of acetylated LDL in the presence of an ACAT inhibitor (49). In these conditions, proteasomal degradation of ABCA1 protein is accelerated (17). However, the same study noted that when ACAT inhibition was omitted during cholesterol loading, resulting in a less dramatic increase in free cholesterol (∼2–3-fold increase over basal levels (50)), ABCA1 protein was stabilized. These increases in free cholesterol are similar to those used in the present study, where we found that both ABCA1 and ABCG1 proteins were stabilized in human macrophages, as well as overexpressing model cells. We suggest that such intermediate increases in cell cholesterol promote a protective mechanism that is relatively specific to these cholesterol transporters and that, by limiting their degradation, maintains the capacity of the cells to export this excess cholesterol and to restore cell cholesterol balance.

Plasma membrane localized ABCA1 can also be degraded by ubiquitin-dependent lysosomal proteolysis in human hepatoma cells and THP-1 macrophages (51). This appears distinct from the calpain-mediated degradation pathway for ABCA1, which occurs in the absence of apolipoprotein A-I or other helical apolipoprotein acceptors of cell cholesterol (52, 53) (reviewed in Ref. 28). The calpain pathway depends on phosphorylation of a PEST sequence in the central intracellular loop of ABCA1, which is suppressed in the presence of apoA-I at physiological levels. This probably explains why we observed that calpain-mediated proteolysis contributed only modestly to ABCA1 degradation in our studies, because they were performed in media containing 0.5% serum. Calpain-mediated degradation of plasma membrane localized ABCG1 and ABCA7 have also been reported (25, 54), although in our studies we observed no obvious calpain-dependent degradation of ABCG1. However, only 10–20% of cellular ABCG1 is expressed at the plasma membrane,4 and more targeted studies may be needed to detect changes in turnover of this minor proportion of ABCG1 protein. The mechanisms by which ABCG1 and ABCA7 are targeted to calpain are not understood, although it has been suggested that ABCG1 contains a PEST domain in its amino-terminal cytosolic domain. It would be of interest to determine whether these calpain and lysosomal pathways are also sensitive to cell cholesterol status. Similarly, the relevance of cholesterol-dependent control of proteasomal degradation to other ABC transporter members, particularly those implicated in lipid metabolism and traffic, merits investigation.

In summary, the turnover of both ABCA1 and ABCG1 proteins responds very rapidly to fluctuations in cell cholesterol, which may provide a responsive acute control of cholesterol export capacity. The relative importance of this post-translational control of transporter expression, in addition to cholesterol/LXR-dependent transcriptional regulation, remains to be determined.

Acknowledgment

The contribution of Carmel M. Quinn in the generation of ABCG1-null THP-1 clones and Fig. 1C is acknowledged.

This work was supported by a Pfizer CardioVascular Lipid grant (to V. H.), National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Program grants (to W. J. and L. K.), and a Principal Research Fellowship (to W. J.).

V. Hsieh, M.-J. Kim, and W. Jessup, unpublished studies.

- apoA-I

- apolipoprotein A-I

- ALLN

- N-acetyl-l-leucyl-l-leucyl-l-norleucinal

- CD

- cyclodextrin

- EEA1

- early endosome antigen 1

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- LXR

- liver X receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gelissen I. C., Harris M., Rye K. A., Quinn C., Brown A. J., Kockx M., Cartland S., Packianathan M., Kritharides L., Jessup W. (2006) ABCA1 and ABCG1 synergize to mediate cholesterol export to apoA-I. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 534–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jessup W., Gelissen I. C., Gaus K., Kritharides L. (2006) Roles of ATP binding cassette transporters A1 and G1, scavenger receptor BI and membrane lipid domains in cholesterol export from macrophages. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 17, 247–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Out R., Jessup W., Le Goff W., Hoekstra M., Gelissen I. C., Zhao Y., Kritharides L., Chimini G., Kuiper J., Chapman M. J., Huby T., Van Berkel T. J., Van Eck M. (2008) Coexistence of foam cells and hypocholesterolemia in mice lacking the ABC transporters A1 and G1. Circ. Res. 102, 113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wong J, Quinn CM, Brown A. J. (2006) SREBP-2 positively regulates transcription of the cholesterol efflux gene, ABCA1, by generating oxysterol ligands for LXR. Biochem. J. 400, 485–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chawla A., Boisvert W. A., Lee C.-H., Laffitte B. A., Barak Y., Joseph S. B., Liao D., Nagy L., Edwards P. A., Curtiss L. K., Evans R. M., Tontonoz P. (2001) A PPARγ-LXR-ABCA1 pathway in macrophages is involved in cholesterol efflux and atherogenesis. Mol. Cell 7, 161–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spann N. J., Garmire L. X., McDonald J. G., Myers D. S., Milne S. B., Shibata N., Reichart D., Fox J. N., Shaked I., Heudobler D., Raetz C. R., Wang E. W., Kelly S. L., Sullards M. C., Murphy R. C., Merrill A. H., Jr., Brown H. A., Dennis E. A., Li A. C., Ley K., Tsimikas S., Fahy E., Subramaniam S., Quehenberger O., Russell D. W., Glass C. K. (2012) Regulated accumulation of desmosterol integrates macrophage lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell 151, 138–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wellington C. L., Walker E. K., Suarez A., Kwok A., Bissada N., Singaraja R., Yang Y.-Z., Zhang L.-H., James E., Wilson J. E., Francone O., McManus B. M., Hayden M. R. (2002) ABCA1 mRNA and protein distribution patterns predict multiple different roles and levels of regulation. Lab. Invest. 82, 273–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arakawa R., Yokoyama S. (2002) Helical apolipoproteins stabilize ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 by protecting it from thiol protease-mediated degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 22426–22429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang Y., Oram J. F. (2002) Unsaturated fatty acids inhibit cholesterol efflux from macrophages by increasing degradation of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 5692–5697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bowden K., Ridgway N. D. (2008) OSBP negatively regulates ABCA1 protein stability. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18210–18217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Munehira Y., Ohnishi T., Kawamoto S., Furuya A., Shitara K., Imamura M., Yokota T., Takeda S., Amachi T., Matsuo M., Kioka N., Ueda K. (2004) α1-Syntrophin modulates turnover of ABCA1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 15091–15095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nagelin M. H., Srinivasan S., Lee J., Nadler J. L., Hedrick C. C. (2008) 12/15-Lipoxygenase activity increases the degradation of macrophage ATP-binding cassette transporter G1. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 1811–1819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nagelin M. H., Srinivasan S., Nadler J. L., Hedrick C. C. (2009) Murine 12/15-lipoxygenase regulates ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 protein degradation through p38- and JNK2-dependent pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 31303–31314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burns V., Sharpe L. J., Gelissen I. C., Brown A. J. (2013) Species variation in ABCG1 isoform expression. Implications for the use of animal models in elucidating ABCG1 function. Atherosclerosis 226, 408–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gelissen I. C., Cartland S., Brown A. J., Sandoval C., Kim M., Dinnes D. L., Lee Y., Hsieh V., Gaus K., Kritharides L., Jessup W. (2010) Expression and stability of two isoforms of ABCG1 in human vascular cells. Atherosclerosis 208, 75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gelissen I. C., Sharpe L. J., Sandoval C., Rao G., Kockx M., Kritharides L., Jessup W., Brown A. J. (2012) Protein kinase A modulates the activity of a major human isoform of ABCG1. J. Lipid Res. 53, 2133–2140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feng B., Tabas I. (2002) ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux is defective in free cholesterol-loaded macrophages. Mechanism involves enhanced ABCA1 degradation in a process requiring full NPC1 activity. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43271–43280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gelissen I. C., Brown A. J., Mander E. L., Kritharides L., Dean R. T., Jessup W. (1996) Sterol efflux is impaired from macrophage foam cells selectively enriched with 7-ketocholesterol. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 17852–17860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Larrede S., Quinn C. M., Jessup W., Frisdal E., Olivier M., Hsieh V., Kim M. J., Van Eck M., Couvert P., Carrie A., Giral P., Chapman M. J., Guerin M., Le Goff W. (2009) Stimulation of cholesterol efflux by LXR agonists in cholesterol-loaded human macrophages is ABCA1-dependent but ABCG1-independent. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29, 1930–1936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scarselli E., Ansuini H., Cerino R., Roccasecca R. M., Acali S., Filocamo G., Traboni C., Nicosia A., Cortese R., Vitelli A. (2002) The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J. 21, 5017–5025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brown A. J., Sun L., Feramisco J. D., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (2002) Cholesterol addition to ER membranes alters conformation of SCAP, the SREBP escort protein that regulates cholesterol metabolism. Mol. Cell 10, 237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garner B., Baoutina A., Dean R. T., Jessup W. (1997) Regulation of serum-induced lipid accumulation in human monocyte-derived macrophages by interferon-γ. Correlations with apolipoprotein E production, lipoprotein lipase activity and LDL receptor-related protein expression. Atherosclerosis 128, 47–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ogura M., Ayaori M., Terao Y., Hisada T., Iizuka M., Takiguchi S., Uto-Kondo H., Yakushiji E., Nakaya K., Sasaki M., Komatsu T., Ozasa H., Ohsuzu F., Ikewaki K. (2011) Proteasomal inhibition promotes ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) and ABCG1 expression and cholesterol efflux from macrophages in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31, 1980–1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kobayashi A., Takanezawa Y., Hirata T., Shimizu Y., Misasa K., Kioka N., Arai H., Ueda K., Matsuo M. (2006) Efflux of sphingomyelin, cholesterol, and phosphatidylcholine by ABCG1. J. Lipid Res. 47, 1791–1802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hori N., Hayashi H., Sugiyama Y. (2011) Calpain-mediated cleavage negatively regulates the expression level of ABCG1. Atherosclerosis 215, 383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fitzgerald M. L., Mendez A. J., Moore K. J., Andersson L. P., Panjeton H. A., Freeman M. W. (2001) ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 contains an NH2-terminal signal anchor sequence that translocates the protein's first hydrophilic domain to the exoplasmic space. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 15137–15145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kockx M., Dinnes D. L., Huang K. Y., Sharpe L. J., Jessup W., Brown A. J., Kritharides L. (2012) Cholesterol accumulation inhibits ER to Golgi transport and protein secretion. Studies of apolipoprotein E and VSVGt. Biochem. J. 447, 51–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yokoyama S., Arakawa R., Wu C.-A., Iwamoto N., Lu R., Tsujita M., Abe-Dohmae S. (2012) Calpain-mediated ABCA1 degradation. Post-translational regulation of ABCA1 for HDL biogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1821, 547–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fenteany G., Schreiber S. L. (1998) Lactacystin, proteasome function, and cell fate. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 8545–8548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Out R., Hoekstra M., Hildebrand R. B., Kruit J. K., Meurs I., Li Z., Kuipers F., Van Berkel T. J., Van Eck M. (2006) Macrophage ABCG1 deletion disrupts lipid homeostasis in alveolar macrophages and moderately influences atherosclerotic lesion development in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 2295–2300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Out R., Hoekstra M., Meurs I., de Vos P., Kuiper J., Van Eck M., Van Berkel T. J. (2007) Total body ABCG1 expression protects against early atherosclerotic lesion development in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 594–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yvan-Charvet L., Ranalletta M., Wang N., Han S., Terasaka N., Li R., Welch C., Tall A. R. (2007) Combined deficiency of ABCA1 and ABCG1 promotes foam cell accumulation and accelerates atherosclerosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 3900–3908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hozoji M., Munehira Y., Ikeda Y., Makishima M., Matsuo M., Kioka N., Ueda K. (2008) Direct interaction of nuclear liver X receptor-beta with ABCA1 modulates cholesterol efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 30057–30063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vembar S. S., Brodsky J. L. (2008) One step at a time. Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 944–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Raiborg C., Stenmark H. (2009) The ESCRT machinery in endosomal sorting of ubiquitylated membrane proteins. Nature 458, 445–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Haglund K., Dikic I. (2012) The role of ubiquitylation in receptor endocytosis and endosomal sorting. J. Cell Sci. 125, 265–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gill S., Stevenson J., Kristiana I., Brown A. J. (2011) Cholesterol-dependent degradation of squalene monooxygenase, a control point in cholesterol synthesis beyond HMG-CoA reductase. Cell Metab. 13, 260–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ravid T., Doolman R., Avner R., Harats D., Roitelman J. (2000) The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway mediates the regulated degradation of mammalian 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35840–35847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee J. P., Brauweiler A., Rudolph M., Hooper J. E., Drabkin H. A., Gemmill R. M. (2010) The TRC8 ubiquitin ligase is sterol regulated and interacts with lipid and protein biosynthetic pathways. Mol. Cancer Res. 8, 93–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Scotti E., Calamai M., Goulbourne C. N., Zhang L., Hong C., Lin R. R., Choi J., Pilch P. F., Fong L. G., Zou P., Ting A. Y., Pavone F. S., Young S. G., Tontonoz P. (2013) IDOL stimulates clathrin-independent endocytosis and multivesicular body-mediated lysosomal degradation of the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 1503–1514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang N., Tall A. R. (2003) Regulation and mechanisms of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1-mediated cellular cholesterol efflux. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 1178–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Azuma Y., Takada M., Maeda M., Kioka N., Ueda K. (2009) The COP9 signalosome controls ubiquitinylation of ABCA1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 382, 145–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stagg H. R., Thomas M., van den Boomen D., Wiertz E. J., Drabkin H. A., Gemmill R. M., Lehner P. J. (2009) The TRC8 E3 ligase ubiquitinates MHC class I molecules before dislocation from the ER. J. Cell Biol. 186, 685–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zelcer N., Hong C., Boyadjian R., Tontonoz P. (2009) LXR regulates cholesterol uptake through Idol-dependent ubiquitination of the LDL receptor. Science 325, 100–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hong C., Duit S., Jalonen P., Out R., Scheer L., Sorrentino V., Boyadjian R., Rodenburg K. W., Foley E., Korhonen L., Lindholm D., Nimpf J., van Berkel T. J., Tontonoz P., Zelcer N. (2010) The E3 ubiquitin ligase IDOL induces the degradation of the low density lipoprotein receptor family members VLDLR and ApoER2. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 19720–19726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ward C. L., Omura S., Kopito R. R. (1995) Degradation of CFTR by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cell 83, 121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nakagawa H., Tamura A., Wakabayashi K., Hoshijima K., Komada M., Yoshida T., Kometani S., Matsubara T., Mikuriya K., Ishikawa T. (2008) Ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation of non-synonymous SNP variants of human ABC transporter ABCG2. Biochem. J. 411, 623–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schröder M., Kaufman R. J. (2005) ER stress and the unfolded protein response. Mutat. Res. 569, 29–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Feng B., Yao P. M., Li Y., Devlin C. M., Zhang D., Harding H. P., Sweeney M., Rong J. X., Kuriakose G., Fisher E. A., Marks A. R., Ron D., Tabas I. (2003) The endoplasmic reticulum is the site of cholesterol-induced cytotoxicity in macrophages. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 781–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kritharides L., Jessup W., Mander E. L., Dean R. T. (1995) Apolipoprotein A-I-mediated efflux of sterols from oxidized LDL-loaded macrophages. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15, 276–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mizuno T., Hayashi H., Naoi S., Sugiyama Y. (2011) Ubiquitination is associated with lysosomal degradation of cell surface-resident ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) through the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) pathway. Hepatology 54, 631–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang N., Chen W., Linsel-Nitschke P., Martinez L. O., Agerholm-Larsen B., Silver D. L., Tall A. R. (2003) A PEST sequence in ABCA1 regulates degradation by calpain protease and stabilization of ABCA1 by apoA-I. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 99–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Arakawa R., Hayashi M., Remaley A. T., Brewer B. H., Yamauchi Y., Yokoyama S. (2004) Phosphorylation and stabilization of ATP binding cassette transporter A1 by synthetic amphiphilic helical peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 6217–6220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tanaka N., Abe-Dohmae S., Iwamoto N., Fitzgerald M. L., Yokoyama S. (2010) Helical apolipoproteins of high-density lipoprotein enhance phagocytosis by stabilizing ATP-binding cassette transporter A7. J. Lipid Res. 51, 2591–2599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]