Background: Biphenotypic hepatocytes expressing Sox9 emerge upon liver injuries associated with ductular reaction.

Results: Sox9+ biphenotypic hepatocytes are derived from mature hepatocytes (MHs). Some of them are incorporated into ductular structures, whereas they efficiently differentiate to functional hepatocytes.

Conclusion: Biphenotypic hepatocytes not only terminally convert to cholangiocytes but also differentiate back to MHs.

Significance: Mature epithelial cells can show plasticity upon severe injuries and contribute to regeneration.

Keywords: Cell Differentiation, Cell Polarity, Hepatocyte, Liver, Regeneration, Biphenotypic Cells, Ductular Reaction, Liver Stem/Progenitor Cells

Abstract

It has been shown that mature hepatocytes compensate tissue damages not only by proliferation and/or hypertrophy but also by conversion into cholangiocyte-like cells. We found that Sry HMG box protein 9-positive (Sox9+) epithelial cell adhesion molecule-negative (EpCAM−) hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α-positive (HNF4α+) biphenotypic cells showing hepatocytic morphology appeared near EpCAM+ ductular structures in the livers of mice fed 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC)-containing diet. When Mx1-Cre:ROSA mice, which were injected with poly(I:C) to label mature hepatocytes, were fed with the DDC diet, we found LacZ+Sox9+ cells near ductular structures. Although Sox9+EpCAM− cells adjacent to expanding ducts likely further converted into ductular cells, the incidence was rare. To know the cellular characteristics of Sox9+EpCAM− cells, we isolated them as GFP+EpCAM− cells from DDC-injured livers of Sox9-EGFP mice. Sox9+EpCAM− cells proliferated and could differentiate to functional hepatocytes in vitro. In addition, Sox9+EpCAM− cells formed cysts with a small central lumen in collagen gels containing Matrigel® without expressing EpCAM. These results suggest that Sox9+EpCAM− cells maintaining biphenotypic status can establish cholangiocyte-type polarity. Interestingly, we found that some of the Sox9+ cells surrounded luminal spaces in DDC-injured liver while they expressed HNF4α. Taken together, we consider that in addition to converting to cholangiocyte-like cells, Sox9+EpCAM− cells provide luminal space near expanded ductular structures to prevent deterioration of the injuries and potentially supply new hepatocytes to repair damaged tissues.

Introduction

It has been considered that in chronically injured livers, facultative liver stem/progenitor cells (LPCs)2 are activated, expand, and then contribute to repair of damaged liver tissue (1–3). LPCs prospectively isolated from chronically injured rodent and human livers showed the ability of self-renewal and bidirectional differentiation in vitro and differentiate to mature hepatocytes (MHs) in vivo (4–8) when they were transplanted into livers, where residential MHs proliferation was impaired. Recently, using a lineage tracing technique, it was demonstrated that LPCs supplied MHs in chronically injured livers of mice fed with choline-deficient ethionine-supplemented (CDE) diet (9). It is also demonstrated that in other rodent models of liver injuries induced by 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC)-containing diet, bile duct ligation (BDL), and chronic injection of carbon tetrachloride, ductular reaction is prominently induced, which is often considered as a sign of activation of LPCs. However, recent studies using the lineage tracing technique did not strongly support that LPCs efficiently supply new hepatocytes (9–11).

In addition to LPCs, MHs compensate the loss of hepatocytes by proliferation and hypertrophy after acute liver injuries (12, 13). Furthermore, MHs have been shown to convert to cholangiocyte-like cells both in vitro and in vivo (14–16). Recent studies demonstrated that the ectopic activation of the Notch pathway induced hepatocyte to cholangiocyte conversion (17, 18). Furthermore, in chronically injured human and mouse livers, the Notch pathway is activated, which is suggested to lead to hepatocyte to cholangiocyte conversion (18). However, it remains unclear whether all MHs equally possess the ability to differentiate into cholangiocyte-like cells. It also remains largely unknown how MHs contribute to tissue repair in chronically injured livers by depending on such differentiation potential.

In this study, we showed that in DDC-injured liver, some of the hepatocytes converted to biphenotypic cells recognized as Sry HMG box protein 9 (Sox9)+ epithelial adhesion molecule (EpCAM)− cells. Sox9+EpCAM− cells showed the ability to proliferate and to efficiently differentiate into functional hepatocytes in vitro. They established cholangiocyte-type polarity without expressing EpCAM and formed lumen in three-dimensional culture as well as in DDC-injured liver. Our results indicate that some of the MHs acquire biphenotypic characteristics and contribute to liver tissue repair.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mouse Experiments

C57BL6 mice were purchased from Sankyo Labo Service Corp., Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). Sox9-EGFP mice generated by inserting the IRES-EGFP sequence into the 3′-untranslated region of the endogenous Sox9 gene (19) were used to isolate cells expressing Sox9 as GFP+ cells. For in vivo lineage tracing of hepatocytes, Mx1-Cre mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were crossed with the Cre-inducible ROSA26R lacZ reporter mice (provided by Dr. Phillippe Soriano) (20). Mx1-Cre expression was induced by two intraperitoneal injections of poly(I:C) (250 μg, intraperitoneal; Invitrogen) at a 2-day interval. Three days after the second injection of poly(I:C), we started to feed mice with 0.1% DDC diet. All the animal experiments were approved by the Sapporo Medical University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were carried out under the institutional guidelines for ethical animal use.

Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemistry

Liver tissues isolated from DDC-fed mice were fixed in Zamboni solution for 8–10 h at 4 °C with continuous rotation. Liver tissues from other injury models were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. After washing in PBS and soaking in PBS containing 30% sucrose, they were embedded in O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) and used for preparation of thin sections. Frozen sections were incubated with primary antibodies listed in Table 1 followed by Alexa Fluor dye-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). In in vivo lineage tracing experiments using Mx1-Cre:ROSA26R mice, sections were incubated with an X-gal staining solution (35 mm potassium ferricyanide, 35 mm potassium ferrocyanide, and 1 mg/ml X-gal in PBS) overnight followed by Sox9 immunohistochemistry using a New Fuchsin alkaline phosphatase method (Nichirei Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan). Images were collected using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal laser scanning microscope or an Olympus X-80 fluorescence microscope.

TABLE 1.

Primary antibodies

IF, immunofluorescence; APC, allophycocyanin.

| Antibody | Company/source | Host animal | Method | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin | Bethyl Laboratories | Goat | IF | 1:1000 |

| CD16/32 | BD Pharmingen | Rat | FACS | 1:1000 |

| CD45 | BD Pharmingen | Rat | FACS | 1:1000 |

| Cytokeratin 19 | Tanimizu et al. (21) | Rabbit | IF | 1:2000 |

| EpCAM | BD Pharmingen | Rat | IF | 1:500 |

| EpCAM (FITC- or APC-conjugated) | BioLegend | Rat | FACS | 1:1000 |

| GFP | MBL | Rabbit | IF | 1:1000 |

| Grhl2 | Sigma-Aldrich | Rabbit | IF | 1:500 |

| HNF1β | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Rabbit | IF | 1:200 |

| HNF4α | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Rabbit | IF | 1:200 |

| HNF4α | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Goat | IF | 1:200 |

| Sox9 | Millipore | Rabbit | IF | 1:2000 |

| TER119 | BD Pharmingen | Rat | FACS | 1:1000 |

At day 7 of culture, colonies were fixed in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 15 min. After permeabilization with 0.2% Triton X-100 and blocking with BlockAce (Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Tokyo, Japan), cells were incubated with anti-mouse cytokeratin (CK) 19 (21) and anti-mouse albumin (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX) antibodies. Signals were visualized with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes) and Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated anti-goat IgG. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (Dojindo Molecular Technology, Inc., Masushiro, Japan). Images for samples were acquired on a Nikon X-81 fluorescence microscope.

Isolation of Sox9+EpCAM− Cells

Normal and DDC-injured livers of Sox9-EGFP mice were digested with a two-step collagenase perfusion method. After eliminating hepatocytes by centrifugation at 800 rpm × 3 min, the cell suspension was centrifuged at 1400 rpm × 4 min (non-parenchymal fraction). Remaining tissues after two-step collagenase perfusion were further digested in collagenase/hyaluronidase solution. Cell suspension was centrifuged at 1400 rpm × 4 min (cholangiocyte fraction). Cells derived from non-parenchymal and cholangiocyte fractions were combined and treated with an anti-FcR antibody (BD Biosciences) followed by incubation with an allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-EpCAM antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, CA). GFP+EpCAM− and GFP+EpCAM+ cells were isolated on a FACSAria II (BD Biosciences).

Culture of Sox9+ Cells

To perform clonal analysis, GFP+EpCAM− and GFP+EpCAM+ cells were plated onto 35-mm culture dishes coated with laminin 111 (BD Biosciences) at 3000 and 1500 cells/dish, respectively. Cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 10−7 m dexamethasone, 1× Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium, 10 mm nicotinamide, 10 ng/ml EGF, 10 ng/ml hepatocyte growth factor, and 20 μm Y-27632 (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan), which was reported to promote clonal proliferation (6).

For inducing hepatocytic differentiation, cells were plated onto culture dishes coated with gelatin. After they became confluent, the cells were treated with 20 ng/ml oncostatin M (R&D, Minneapolis, MN) and 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then overlaid with 5% Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm (EHS) gel (Matrigel®, BD Biosciences). The ability to eliminate ammonium ions from the medium was examined by using the Wako ammonia test (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). Two mm ammonium chloride was added to EpCAM− cells treated with Matrigel® for 4 days. Albumin secreted from cultured cells was measured by a sandwich ELIZA. The accumulation of glycogen was examined by periodic acid-Schiff staining. To enhance the formation of bile canaliculus (BC) structures in the colonies, 100 μm taurocholate (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was added to the medium for 1 day (22). The formation of BC-like structures was certified by incubation with fluorescein diacetate (Sigma-Aldrich). Metabolized fluorescein was secreted into BC-like structures.

To examine the ability to differentiate to cholangiocytes, 5 × 103 GFP+EpCAM− or GFP+EpCAM+ cells were seeded onto a 1:1 mixture of type I collagen and Matrigel® in a well of an 8-well cover glass chamber (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). After adding DMEM/F12 medium containing EGF, hepatocyte growth factor, and Y-27632, cells were cultured for 2 weeks.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from each colony by lysing cells within a cloning ring (Asahi Glass Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). cDNAs were synthesized using Sensiscript reverse transcriptase (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with random hexamers (Takara, Otsu, Japan). Primers used for RT-PCR are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for PCR

HPRT, hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase.

| Gene name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Albumin (sense) | atgagattctgacccagtgttg |

| Albumin (antisense) | ttctccttcacaccatcaagc |

| CK19 (sense) | agattgagagagaacacgccttgc |

| CK19 (antisense) | tcaggctctcaatctgcatctcca |

| CPSI (sense) | tgggatcttgaccgtttcc |

| CPSI (antisense) | accaatggccatgacctc |

| Cyp1a2 (sense) | ccctgcccttcagtggtaca |

| Cyp1a2 (antisense) | gaagagccgagtcatggaag |

| Cyp2b10 (sense) | gttgagccaaccttcaaggaa |

| Cyp2b10 (antisense) | aagagctcaaacatctggctg |

| Cyp2d10 (sense) | gatcccaaggtgtggtcctt |

| Cyp2d10 (antisense) | gcaggagtatggggaacata |

| EpCAM (sense) | ctgtcatttgctccaaactggcgt |

| EpCAM (antisense) | cgttgcactgcttggctttgaaga |

| HPRT (sense) | tcctcctcagaccgctttt |

| HPRT (antisense) | cctggttcatcatcgctaatc |

| PEPCK (sense) | ttgatgcccaaggcaactta |

| PEPCK (antisense) | acggccaccaaagatgatac |

| Sox9 (sense) | cagcaagactctgggcaag |

| Sox9 (antisense) | atcggggtggtctttcttgt |

| TAT (sense) | caacaacccgtccaatcc |

| TAT (antisense) | gacgcattgcctttcagc |

| Tdo2 (sense) | tgagtaaaggtgaacgacgac |

| Tdo2 (antisense) | acggccaccaaagatgatac |

RESULTS

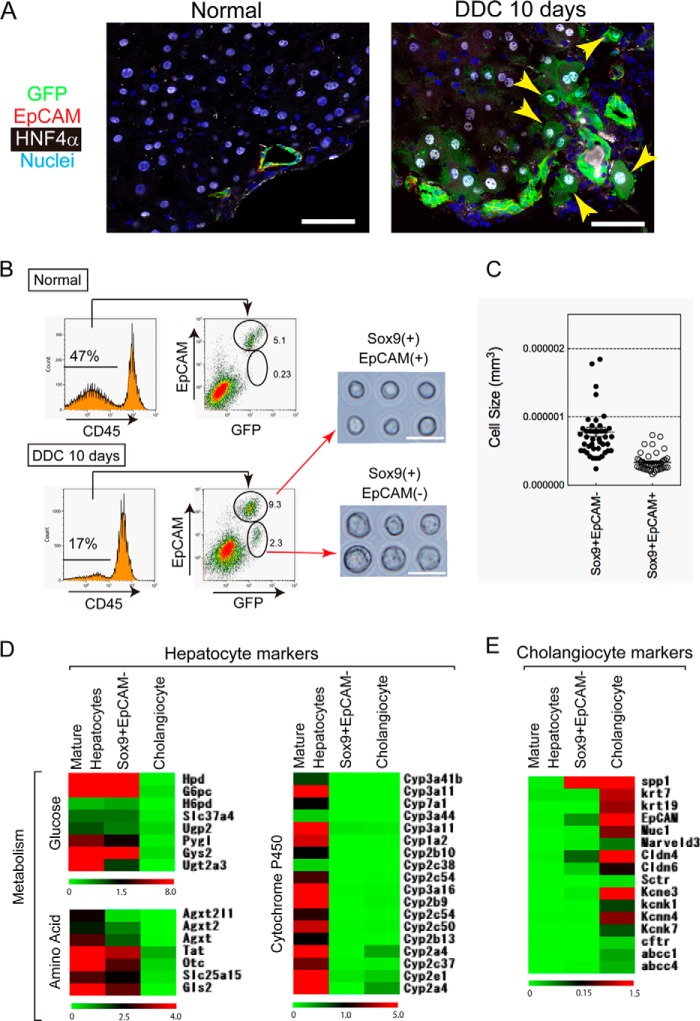

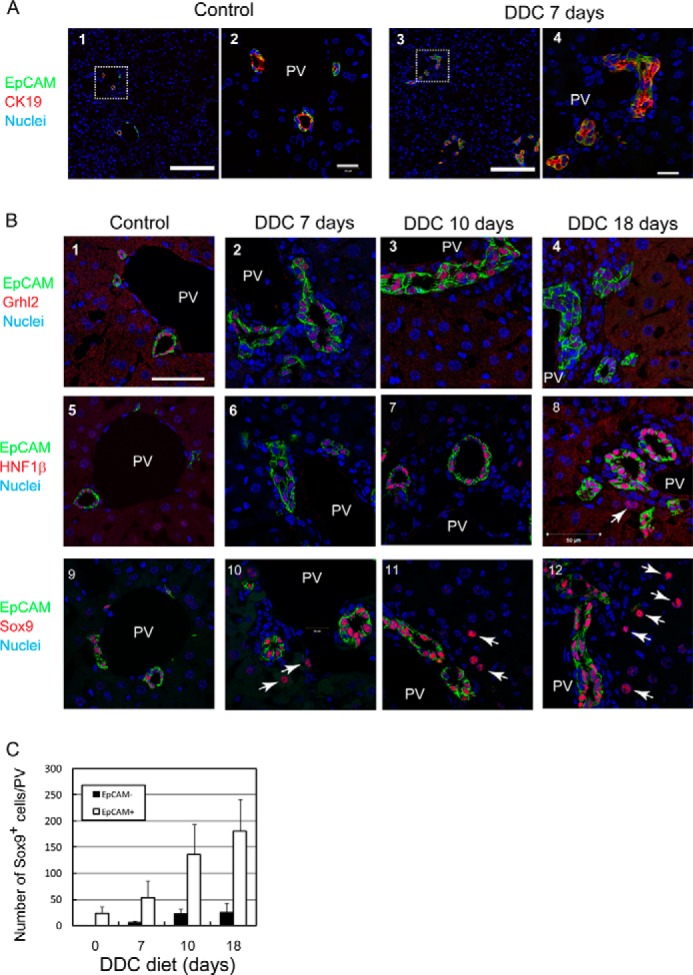

Sox9+EpCAM− Cells Appear in DDC-injured Livers

In the previous study, we identified several cholangiocyte-specific genes including grainyhead-like 2 (Grhl2), hepatocyte nuclear factor 1β (HNF1β), and Sox9 by comparing hepatoblasts and cholangiocytes (23). They are exclusively expressed in bile ducts in normal liver. However, their expression has not been examined in liver injuries that result in an activation of LPCs. The DDC diet has often been used to induce liver injury with ductular reaction, in which LPCs recognized as EpCAM+CK19+ cells are activated and expanded (24) (Fig. 1A). We compared expression of Grhl2, and Sox9 as well as HNF1β in the liver of DDC-fed mice with that in the normal liver. Consistent with previous studies (23, 25), HNF1β, Grhl2, and Sox9 were detected in the nuclei of EpCAM+ bile duct cells in the normal liver (Fig. 1B, panels 1, 5, and 9). In the injured liver, Grhl2 was exclusively expressed in EpCAM+ ductular cells (Fig. 1B, panels 2–4). HNF1β was mostly expressed in EpCAM+ cells, although a small number of EpCAM− cells expressed HNF1β (Fig. 1B, panel 8, arrow). In contrast, Sox9 was obviously expressed in cells other than EpCAM+ ductular cells (Fig. 1B, panels 10–12, arrows). As shown in Fig. 1C, the number of Sox9+EpCAM− cells increased when mouse were fed with the DDC diet for 18 days; an especially significant increase of the cells was observed between 7 and 10 days.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of cholangiocyte specific transcription factors in DDC-injured liver. A, ductular reactions are induced by DDC diet. Ductular structures consisting of CK19+EpCAM+ cells are expanded in the liver of DDC diet-fed mice. The boxes in panels 1 and 3 are enlarged in panels 2 and 4, respectively. Bars in panels 1 and 3 and panels 2 and 4 are 100 μm and 20 μm, respectively. PV, portal vein. B, expression of Grhl2, HNF1β, and Sox9 in DDC-injured livers. In the control, Grhl2, HNF1β, and Sox9 are exclusively expressed in EpCAM+ bile ducts around the portal veins (PV) (panels 1, 5, and 9). In DDC-injured livers, Grhl2 is expressed only in EpCAM+ ductular structures (panels 2–4). HNF1β is mostly expressed in EpCAM+ cells (panels 6–8), although it is occasionally detected in EpCAM− cells (arrow in panel 8). On the other hand, Sox9 is apparently expressed in EpCAM− cells in addition to EpCAM+ ductular cells (arrows in panels 10–12). Bar represents 50 μm. C, the number of Sox9+EpCAM− and Sox9+EpCAM+ cells at different time points during DDC feeding. Numbers of Sox9+EpCAM− cells are much less than EpCAM+ cells but increase in livers of DDC diet fed-mice. At each time point, livers of 3–4 mice were analyzed. Bars represent means ± S.E.

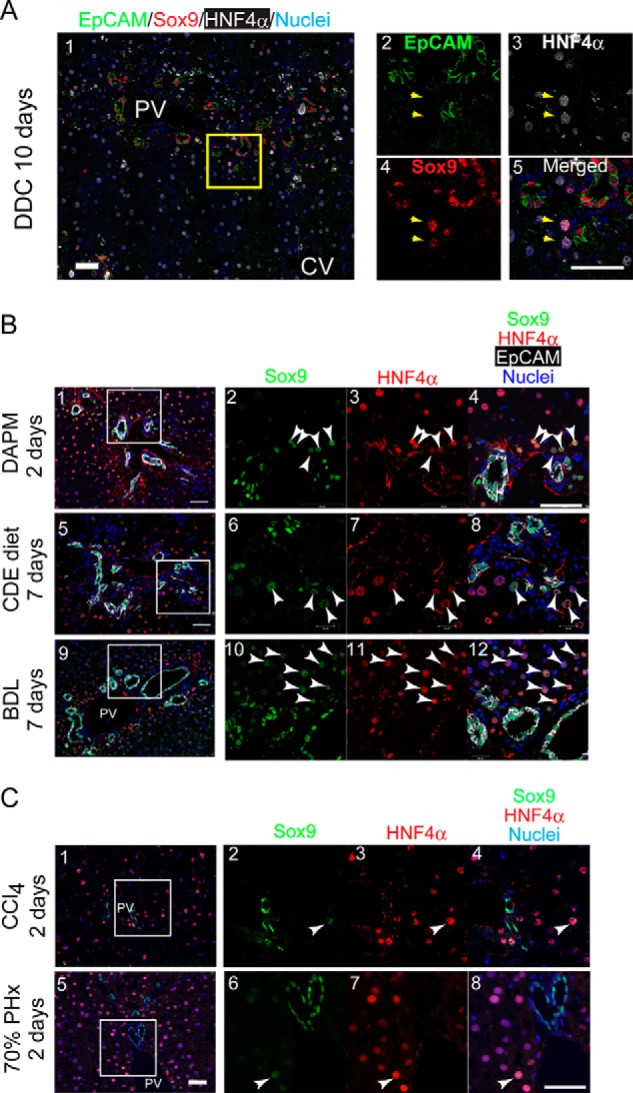

We performed co-staining of Sox9 with HNF4α and found that Sox9+ non-ductular cells were positive for HNF4α (Fig. 2A), a conventional marker of hepatocytes, indicating that cells with characteristics of both hepatocyte and cholangiocyte (biphenotypic cells) emerged in DDC-injured livers. We also examined co-expression of Sox9 and HNF4α in livers of other injury models. Sox9+HNF4α+ cells were observed in livers of mice fed with CDE diet, injected with 4,4′-diaminodiphenylmethane (DAPM), and operated with BDL (Fig. 2B). Although Sox9+HNF4α+ cells were also detected in regenerating livers at 2 days after 70% partial hepatectomy and after a single injection of carbon tetrachloride, the number of such biphenotypic cells was much less than that in CDE-, DDC-, DAPM-, and BDL-injured livers (Fig. 2C) and disappeared at 7 days (data not shown). These results suggest that Sox9+EpCAM−HNF4α+ biphenotypic cells appear upon liver injuries inducing ductular reactions.

FIGURE 2.

Sox9+ biphenotypic cells appear in injured livers associated with ductular reactions. A, expression of HNF4α in non-ductular Sox9+ cells. Non-ductular Sox9+ cells (arrows) are also positive for HNF4α, a hepatocyte marker. The box in panel 1 is enlarged in panels 2–5. Bars represent 50 μm. B, expression of Sox9 and HNF4α in injured livers including ductular reactions. Sox9+HNF4α+ cells (arrowheads) emerge in DAPM-, CDE-, and BDL-injured livers. The boxes in panels 1, 5, and 9 are enlarged in panels 2–4, 6–8, and 10–12, respectively. Bars represent 50 μm. C, expression of Sox9 and HNF4α in regenerating livers after 70% partial hepatectomy and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) injection. Sox9+HNF4α+ cells were occasionally observed in carbon tetrachloride-injured livers and in regenerating liver after 70% partial hepatectomy (PHx) (white arrowheads). The boxes in panels 1 and 5 are enlarged in panels 2–4 and 6–8, respectively. Bars represent 50 μm.

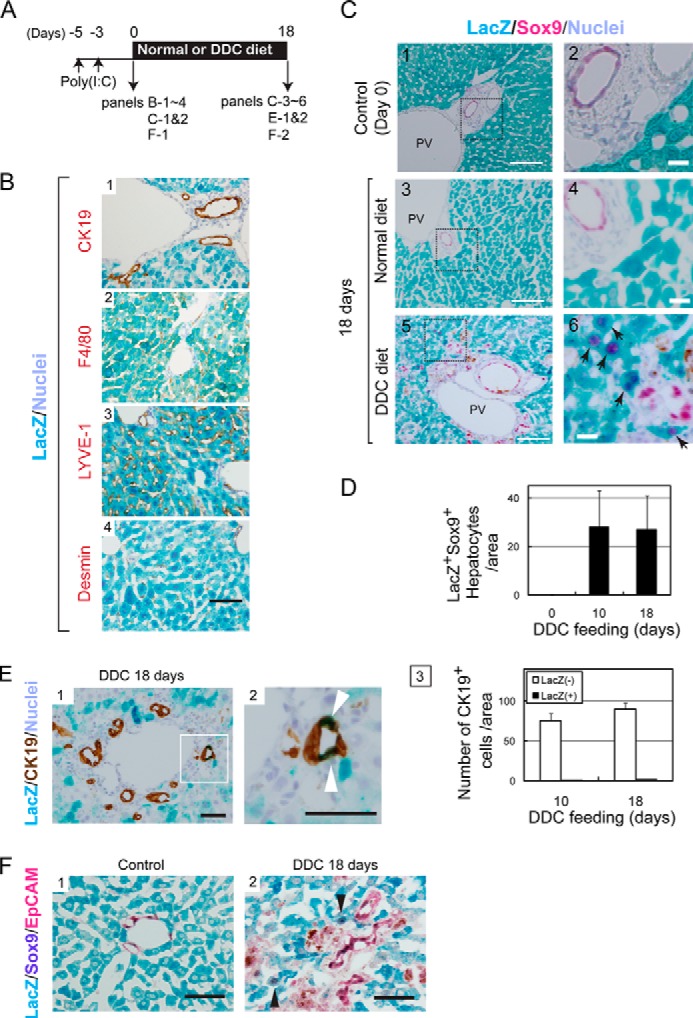

Sox9+EpCAM− Progenitors Are Probably Derived from Hepatocytes

To identify the origin of Sox9+EpCAM− cells, we labeled MHs by using Mx1-Cre:ROSA26 mice. Hepatocytes were labeled with LacZ expression by peritoneal injection of poly(I:C) before feeding mice with the DDC diet (Fig. 3A). Many hepatocytes, but not cholangiocytes, were labeled with LacZ (Fig. 3B, panel 1). We further confirmed that neither LYVE-1+ cells including sinusoidal endothelial cells, Desmin+ stellate cells, nor F4/80+ cells, including Kupffer cells, were labeled with LacZ in this condition (Fig. 3B, panels 2–4). It was previously reported that the recombination was induced not only in hepatocytes but also in other types of cells in Mx1-Cre mice injected with poly(I:C) (26–28). In those studies, poly(I:C) was injected three times instead of twice in the present work. Relatively weak activation of Mx1 promoter may result in limited recombination in hepatocytes in the present work. We confirmed that these LacZ+Sox9+ cells did not emerge without DDC feeding (Fig. 3C, panels 3 and 4). At days 10 and 18 of the DDC diet, we found that some LacZ+Sox9+ cells emerged in periportal area (Fig. 3C, arrows in panels 5 and 6, and 3D). This result indicates that Sox9+ biphenotypic cells derived from hepatocytes emerge in DDC-injured livers. This result is also consistent with the recent study demonstrating that these biphenotypic cells are derived from hepatocytes (18). The same study demonstrated that biphenotypic cells further converted into cholangiocytes. In our experiments, we found that LacZ+CK19+ cells were incorporated into ductular structures (Fig. 3E), suggesting that some of the hepatocytes convert to ductular cells via Sox9+ status. This assumption was further supported by the finding that LacZ+Sox9+ biphenotypic cells were negative for EpCAM (Fig. 3F, panel 2), indicating that it is unlikely that LacZ+ hepatocytes directly converted to Sox9+EpCAM+ cholangiocyte-like cells. However, considering the fact that LacZ+ cells were only about 2% of CK19+ ductular cells at day 18 of the DDC diet, a small number of the Sox9+ biphenotypic cells terminally converted into cholangiocyte-like cells (Fig. 3E).

FIGURE 3.

Mature hepatocytes are the origin of Sox9+ biphenotypic cells. A, the time course of the labeling of MHs in Mx1-Cre:ROSA mice and the induction of liver injury. B, specificity of hepatocytes labeling in Mx1-Cre:ROSA mice. Hepatocytes were labeled with LacZ after poly(I:C) injection. On the other hand, CK19+ cholangiocytes, LYVE-1+ sinusoidal endothelial cells, F4/80+ Kupffer cells, and Desmin+ stellate cells were not labeled with LacZ in Mx1-Cre:ROSA mice injected with poly(I:C). Bar represents 50 μm. C, LacZ+ hepatocytes convert to Sox9+ cells. Before DDC injury, LacZ staining is limited to MHs (panels 1 and 2). After feeding mice with the DDC diet for 10 and 18 days, LacZ+Sox9+ cells appear near the portal vein (PV) (arrows in panels 4 and 6). Bars in panels 1, 3, and 5 represent 100 μm, while those in panels 2, 4, and 6 represent 20 μm. D, the number of LacZ+Sox9+ cells with hepatocyte morphology. The number of LacZ+Sox9+ cells showing hepatocyte morphology was counted on liver sections of normal and DDC diet-fed mice. Error bars represent S.E. E, CK19+LacZ+ cells emerge in DDC-injured livers of Mx1-Cre:ROSA mice. After 18 days of DDC injury, some of LacZ+ cells are incorporated to ductular structures as CK19+ cells (white arrowheads). The number of CK19+LacZ+ cell is slightly increased between 10 and 18 days of DDC injury. At day 18, it represents about 2% of CK19+ cells. Bars in panels 1 and 2 are 50 μm. F, LacZ+Sox9+ cells emerging in DDC-injured liver of Mx1-Cre mice are negative for EpCAM. In the control liver, LacZ+ cells express neither Sox9 nor EpCAM (panel 1). After DDC injury, LacZ+Sox9+ biphenotypic cells, which are negative for EpCAM, are observed (arrowheads in panel 2). EpCAM and Sox9 were visualized with Permanent Red and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate, respectively. Bars represent 50 μm.

Isolation of Sox9+EpCAM− Cells

To further characterize Sox9+EpCAM− cells, we tried to isolate them and examine their differentiation potential in culture. For this purpose, we used Sox9-EGFP mice, where Sox9+ cells express GFP (Fig. 4A). In these mice, Sox9+EpCAM−HNF4α+ biphenotypic cells were recognized as GFP+EpCAM−HNF4α+ cells. After Sox9-EGFP mice were fed the DDC diet for 10 days, the livers were digested with a two-step collagenase perfusion method followed by collagenase/hyaluronidase treatment as described under “Experimental Procedures.” GFP+EpCAM− cells were isolated by cell sorting (Fig. 4B). Reanalysis of purified cells showed that the purity of the EpCAM− fraction was more than 98% (data not shown). We compared the cellular morphology of Sox9+EpCAM− cells with that of Sox9+EpCAM+ cells, which were reported to contain LPCs in addition to cholangiocytes (4). First, Sox9+EpCAM− cells were significantly larger than Sox9+EpCAM+ cells (Fig. 4, B and C). Furthermore, Sox9+EpCAM− cells showed high granularity in their cytoplasm, similar to hepatocytes, whereas Sox9+EpCAM+ cells possessed scant cytoplasm, similar to cholangiocytes (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Isolation of Sox9+EpCAM− cells from DDC-injured liver of Sox9-EGFP mice. A, expression of GFP, HNF4α, and EpCAM in the liver of a DDC diet-fed Sox9-EGFP mouse. Expression of GFP and HNF4α is mutually exclusive in the normal liver (panel 1). In DDC-injured liver, some of the GFP+ cells are positive for HNF4α (arrowheads in panel 2). The GFP+HNF4α+ cells are negative for EpCAM. Bars represent 50 μm. B, flow cytometric analysis of CD45− non-parenchymal cells isolated from normal and DDC-injured livers. In the control, GFP+ (Sox9+) cells are mostly EpCAM+, indicating that they are ductular cholangiocytes. After mice were fed with the DDC diet for 10 days, GFP+EpCAM− cells, in addition to GFP+EpCAM+ cells, become evident. Purified GFP+EpCAM− and GFP+EpCAM+ cells are shown in the right panels. EpCAM− cells are larger and show high granularity in their cytoplasm when compared with EpCAM+ cells. C, Sox9+EpCAM− cells are larger than Sox9+EpCAM+ cells. Cells were isolated from livers after feeding mice with the DDC diet for 10 days. Pictures of purified cells were used for acquiring cell size. Cell size was calculated from the diameter of each cell. D, expression of hepatocyte markers in Sox9+EpCAM− cells. The expression profile of hepatocyte markers is shown. The data suggested that genes related to glucose and amino acid metabolism are weakly expressed in Sox9+EpCAM− biphenotypic cells, whereas Cyps are not expressed. Hierarchical clustering analysis was performed on the MultiExperiment Viewer. E, cholangiocyte markers are barely expressed in Sox9+EpCAM− cells. The expression profile of cholangiocyte markers is shown. Cholangiocyte markers including CK7, CK19, and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (cftr) are not expressed in Sox9+EpCAM− biphenotypic cells. On the other hand, the data suggested that osteopontin (OPN) is significantly expressed in biphenotypic cells.

We further analyzed gene expression patterns of Sox9+EpCAM− cells by using DNA microarray in comparison with cholangiocytes and MHs, which were isolated from normal livers. The result of gene clustering analysis indicates that Sox9+EpCAM− cells expressed genes related to hepatic metabolic enzymes such as glucose 6-phosphatase (G6Pc), glycogen synthetase 2 (Gys2), and tyrosine aminotransferase (TAT), although most of those levels were weaker than that of MHs, and cytochrome P450s (Cyps) genes were not expressed in Sox9+EpCAM− cells (Fig. 4D). On the other hand, they did not express most of the cholangiocyte markers such as CK7, CK19, and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). However, the data also suggested that Sox9+EpCAM− cells significantly expressed osteopontin/secreted phosphoprotein 1 (spp1) (Fig. 4E). These data further strengthen the finding that Sox9+EpCAM− cells are biphenotypic cells, which are closer to MHs than cholangiocytes.

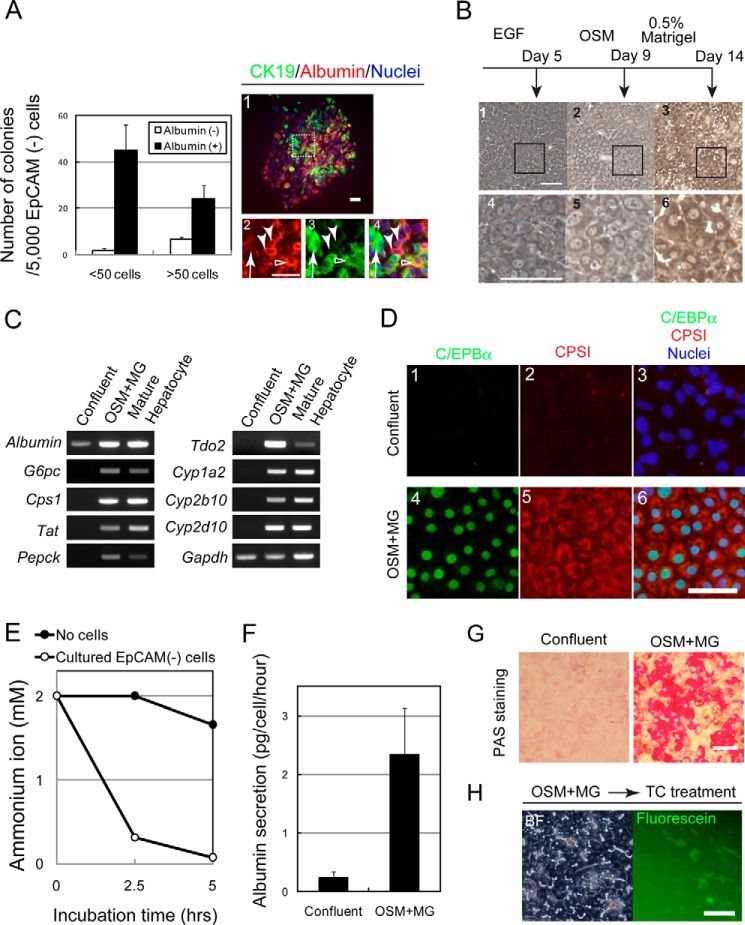

Sox9+EpCAM− Cells Differentiate to Functional Hepatocytes in Vitro

To clarify that Sox9+EpCAM− cells have the capability to be progenitors, we performed a low density culture. Five thousand cells were plated on the dishes, and we found that Sox9+EpCAM− cells clonally proliferated to form colonies. As shown in Fig. 5A, most of the small colonies, which consisted of less than 50 cells, and about 80% of the large colonies, which consisted of over 50 cells, contained both albumin+ cells and CK19+ cells. A typical large colony is shown in the right panels; it contained albumin+CK19− hepatocytes (Fig. 5A, right panels, closed arrowheads), albumin+CK19+ (open arrowheads), and albumin−CK19+ cholangiocyte-like cells (arrows). We isolated the identical population from BDL mice and found that they could also form colonies containing three types of cells (data not shown). These data indicate a possibility that Sox9+EpCAM− cells may have the potential to differentiate to hepatocytes as well as to cholangiocytes. Therefore, we further examined this possibility by inducing hepatocytic and cholangiocytic differentiation of Sox9+EpCAM− cells isolated from DDC-injured livers in two distinctive culture conditions.

FIGURE 5.

Sox9+EpCAM− cells have the potential to differentiate into mature hepatocytes. A, colony-forming ability of Sox9+EpCAM− cells. In the low density culture, Sox9+EpCAM− cells form small and large colonies containing albumin+ and CK19+ cells (closed bars) and colonies containing only CK19+ cells (open bars). A typical colony derived from a Sox9+EpCAM− cell is shown in the right panels. It consists of albumin+CK19− (arrowheads), albumin+CK19+ (open arrowhead), and albumin−CK19+ (arrow) cells. The box in panel 1 is enlarged in panels 2–4. Cells were isolated from 2–3 mice, and experiments were repeated four times. The average values of the number of colonies with S.E. are shown in the graph. Bars represent 50 μm. B, Sox9+EpCAM− cells show hepatocyte-like morphology in the culture. In the presence of oncostatin M (OSM), Sox9+EpCAM− cells show hepatocyte-like morphology (panels 2 and 3), which becomes clearer after the overlay with Matrigel (panels 3 and 6). The boxes in panels 1–3 are enlarged in panels 4–6. Bars represent 50 μm. C, Sox9+EpCAM− cells are induced to express metabolic enzymes and cytochrome P450s. EpCAM− cells differentiate to express markers of MHs in the presence of oncostatin M and Matrigel. Expressions of albumin, CPSI, and tyrosine aminotransferase (Tat) are enhanced during the culture, whereas those of glucose 6-phosphatase (G6pc), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (Pepck), Tdo2, and Cyps are induced. D, Sox9+EpCAM− cells are induced to express CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein α (C/EBPα) and CPSI proteins. Bar represents 50 μm. E, hepatocytes derived from Sox9+EpCAM− cells eliminate ammonium ions from the medium. Two mm ammonium chloride was added to EpCAM− cells treated with Matrigel. The concentration of ammonium ion was examined by using an ammonia test Wako kit. F, hepatocytes derived from Sox9+EpCAM− cells secrete albumin into the medium. When cells became confluent, at which about 2 × 105 cells were in each well of a 24-well plate, or after they were incubated with Matrigel (MG) for 4 days, medium was changed to fresh medium and then kept for 24 h. The concentration of albumin was measured by a sandwich ELIZA. G, hepatocytes derived from Sox9+EpCAM− cells store glycogen in cytosol. Sox9+EpCAM− cells before and after hepatocyte differentiation were fixed, and their glycogen storage was examined by periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining. Bar represents 50 μm. H, hepatocytes derived from Sox9+EpCAM− cells form BC-like structures. After Matrigel overlay, Sox9+EpCAM− cells were further treated with 100 μm taurocholate (TC). When fluorescein diacetate is added to the medium, fluorescein is accumulated into BC-like structures. Bar represents 50 μm.

To examine the characteristics of GFP+EpCAM− cells as hepatocyte progenitors, we induced hepatocytic differentiation/maturation in vitro. The cells were plated on a dish coated with gelatin and treated with oncostatin M and DMSO followed by overlay with Matrigel® (Fig. 5B). After 2 weeks of hepatic induction, they showed hepatocytic morphology, including dense cytoplasm and round nuclei (Fig. 5B, panels 3 and 6), and expressed genes of metabolic enzymes and Cyps (Fig. 5C) and CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein α (C/EBPα) and CPSI proteins (Fig. 5D). They acquired the ability to eliminate ammonium ions from the culture medium (Fig. 5E), secreted albumin into medium (Fig. 5F), and accumulated polysaccharide including glycogen in cytoplasm (Fig. 5G). We also found that cultured GFP+EpCAM− cells acquired Cyp activity (data not shown). After adding taurocholate, which was shown to promote BC formation (22), to GFP+EpCAM− cells, BC-like structures were further evident, and fluorescein derived from fluorescein diacetate accumulated in the structures (Fig. 5H). These data indicated that Sox9+EpCAM− cells had the characteristics of progenitors for hepatocytes.

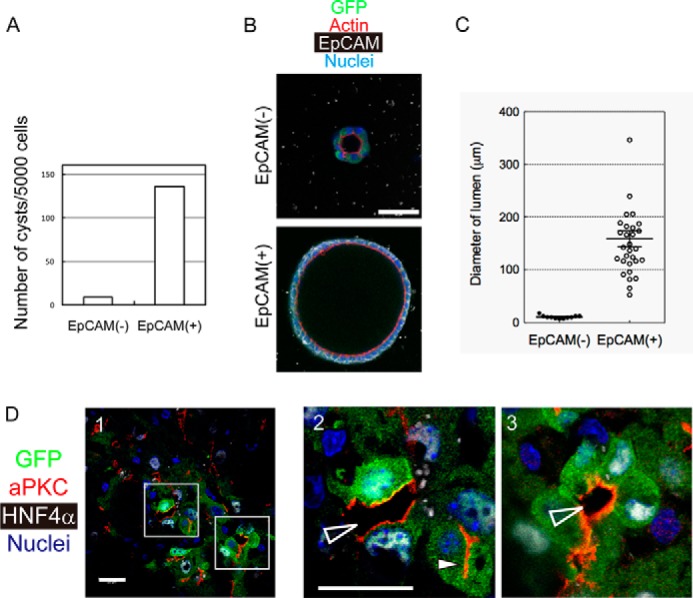

Sox9+EpCAM− Cells Acquire Cholangiocyte-type Apico-basal Polarity

As shown in Fig. 5A, we found CK19+albumin− cells as well as albumin+ hepatocytes in the colony assay. The result suggests a possibility that Sox9+EpCAM− cells might be able to differentiate to cholangiocyte-like cells. To further examine the ability to differentiate to cholangiocyte-like cells, we performed three-dimensional culture, where bipotential progenitors and cholangiocytes form cysts, a spherical structure with the central lumen (29). As a positive control, we also cultured Sox9+EpCAM+ cells that could form cysts. When compared with Sox9+EpCAM+ cells, although efficiency was low, some Sox9+EpCAM− cells could form tiny cysts (Fig. 6, A–C), in which multiple cells surround the central lumen. The formation of cysts suggests that they acquired cholangiocyte-type epithelial polarity. However, the cells forming tiny cysts did not express EpCAM, a marker of cholangiocytes, whereas large cysts derived from Sox9+EpCAM+ cells maintained EpCAM expression (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that Sox9+EpCAM− cells in cysts kept biphenotypic status during the establishment of cholangiocyte-type polarity. Interestingly, in DDC-injured liver, we found that the duct-like structures (Fig. 6D, open arrowheads in panels 2 and 3) in which GFP+ cells with HNF4α expression surrounded lumen in the parenchyma (Fig. 6D). Such luminal structures surrounded by PKCζ, a typical apical marker, were totally different from BCs between MHs that were recognized as narrow lumen by PKCζ staining (Fig. 6D, panel 2, arrowhead). Taken together, in addition to the strong ability to differentiate into functional hepatocytes, Sox9+EpCAM− cells have the potential to generate luminal structures without terminally differentiating into cholangiocyte-like cells in DDC-injured livers.

FIGURE 6.

Sox9+EpCAM− cells show the ability to establish cholangiocyte-type epithelial polarity both in vitro and in vivo. A, number of cysts derived from Sox9+EpCAM− and Sox9+EpCAM+ cells. Cellular structures associated with the apical lumen were counted after 2 weeks of three-dimensional culture. Sox9+EpCAM− and Sox9+EpCAM+ cells were isolated from DDC-injured Sox9-EGFP mice by FACS and seeded onto Matrigel. After being overlaid with 5% Matrigel, cells were incubated for 2 weeks in the presence of EGF, hepatocyte growth factor, and Y-27632. Cells were isolated from three mice and plated into 3 wells of an 8-well coverglass chamber. Experiments were repeated twice. The average of the number of cysts is shown in the graph. B, Sox9+EpCAM− cells form small cysts in three-dimensional culture. A typical cystic structure that emerged in three-dimensional culture of EpCAM− cells is shown with that derived from an EpCAM+ cell. A Sox9+EpCAM− cyst consists of GFP+EpCAM− cells and is associated with a tiny lumen. Bar represents 50 μm. C, the lumen size of cysts derived from EpCAM− and EpCAM+ cells. The lumen size of EpCAM− cysts is much smaller than that of EpCAM+ cells. Data points are shown with means ± S.E. D, Sox9+ biphenotypic cells surround luminal space in DDC-injured liver. GFP+ (Sox9+)HNF4α+ cells emerge in DDC-injured livers. BCs between hepatocytes are recognized by atypical PKC (aPKC) staining (closed arrowhead in panel 2). Additionally, luminal spaces that are obviously larger than BCs are evident (open arrowheads in panels 2 and 3). The boxes in panel 1 are enlarged in panels 2 and 3. Bars represent 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

In the present experiment, we demonstrated that some of the MHs became biphenotypic cells recognized as Sox9+EpCAM− cells, which maintain hepatocytic morphology and HNF4α expression. In addition, we showed that the cells further converted into CK19+ duct cells. This result is consistent with the previous studies indicating that some MHs could transdifferentiate into cholangiocytes (14, 18). Moreover, we found that Sox9+EpCAM− cells isolated from DDC-injured livers had the ability to revert to functional hepatocytes in vitro and that some Sox9+EpCAM− cells could form cholangiocyte-type luminal structures in DDC-injured livers without terminally converting into cholangiocytes.

Lineage conversions in pathophysiological conditions have been reported in multiple organs/tissues including liver, pancreas, lung, and, mammary gland. Although it can be assumed that cells with intermediate status emerge during the conversions, cellular characteristics have not been extensively examined at different time points. Here, we demonstrate that biphenotypic cells emerge during hepatocyte-to-cholangiocyte conversion. Although we cannot totally exclude the possibility that some of the Sox9+EpCAM− biphenotypic cells represent the intermediate status of hepatocyte differentiation from Sox9+EpCAM+ LPCs, the lineage tracing experiments indicate that biphenotypic cells are mainly derived from hepatocytes. Moreover, our results suggest that partial lineage conversion may also be important during regeneration.

As reported previously (30), a subpopulation of hepatocytes called “atypical hepatocytes” expressing A6, a marker for stem/progenitors, appeared in DDC-injured livers. Given that atypical hepatocytes expressed hepatocyte markers, but not cholangiocyte markers such as CK19 and HNF1β, they might be a cell population similar to Sox9+EpCAM− cells shown in this experiment. On the other hand, in DDC-injured livers, LPCs have been identified as EpCAM+ (4), CD133+ (5), Foxl1+ (31), MIC1-1C3+CD133+CD26− (7), or Lgr5+ cells (32). Except for Foxl1, we failed to detect expression of those markers in Sox9+EpCAM− cells isolated from mice fed with the DDC diet for 10 days (data not shown). Therefore, Sox9+EpCAM− cells are likely distinctive to LPCs (4, 5, 7, 32). In addition, Sox9+EpCAM− cells have the potential to be hepatic progenitors with the ability to clonally proliferate and to differentiate into functional hepatocytes. Taken together, in DDC-injured livers, there might be two distinctive progenitor pools: LPCs and Sox9+EpCAM− biphenotypic cells.

It has been shown that LPCs have substantial roles in the expansion of ductular structures in DDC-injured livers (33). In addition to LPCs, Sox9+EpCAM− progenitors derived from MHs may also contribute to the expansion of ductular structures by converting into cholangiocyte-like cells in DDC-injured livers (18). It can be speculated that because cholestasis occurs in DDC-injured liver, hepatocytes near the portal triads may convert into cholangiocyte-like cells to help supply temporal storage structures. However, CK19+ ductular cells derived from MHs account for only about 4 and 2% of the total CK19+ population in the previous study (18) and in our present work, respectively. Another recent study concluded that MHs did not convert into CK19+ cholangiocytes (10). Although the discrepancies of the number of cholangiocytes derived from MHs might be caused by antibody specificities, the period of liver injury, and/or methods for lineage tracing, it is likely that MHs have the potential to convert into cholangiocyte-like cells but the conversion does not frequently occur in DDC-injured livers. In addition to ductular structures containing cholangiocytes derived from MHs, we found that luminal structures were surrounded by Sox9+HNF4α+ cells in lobules of DDC-injured livers. It should be noticed that Sox9+EpCAM− cells expressed syntaxin 3, annexin A2, and claudin 4 (data not shown), which are highly expressed in cholangiocytes and have been implicated in formation of the apical lumen (23, 34, 35). Thus, we consider that MHs can change the mode of polarity, without terminally converting into cholangiocytes, to form luminal spaces for preventing the expansion of the cellular injury, e.g. leakage of bile juice due to cholestasis, in addition to expanding ductular structures derived from LPCs or cholangiocytes. However, because the expansion of ductular structures derived from LPCs is physiologically crucial (11, 33), complete or partial hepatocyte-to-cholangiocyte conversion may be a supportive mechanism responding to liver injuries induced by DDC feeding.

Moreover, we demonstrated that Sox9+EpCAM− cells have the ability to proliferate and to efficiently differentiate into functional hepatocytes in vitro. DDC feeding does not cause massive apoptosis and/or necrosis of MHs but continuously damages MHs because the values of injury markers such as alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) stay high (33). A recent study demonstrated that MHs strongly stained by cleaved caspase 3 were observed in DDC-injured livers (18). We also found some apoptotic MHs in DDC-injured livers (data not shown). Therefore, it is necessary to supply new MHs in DDC-injured livers. However, LPCs do not efficiently supply new MHs in this injury model (9–11). Thus, Sox9+EpCAM− cells are candidates for compensating MHs lost in DDC-injured livers. In the future, we need to show that Sox9+EpCAM− cells, which have the potential of differentiating into MHs as shown here, actually supply MHs in vivo during liver regeneration.

In summary, we have identified Sox9+EpCAM− biphenotypic cells, which may contribute to tissue repair by disclosing cholangiocytic characteristics and by differentiating into functional hepatocytes, in injured mouse livers. Although LPCs have great potential to proliferate in vitro, to apply them for regenerative medicine and pharmaceutical purposes, it is necessary to find a method to efficiently convert them into mature/functional hepatocytes. Because Sox9+EpCAM− cells have intermediate characteristics between cholangiocytes, including LPCs, and MHs, our results may help to reveal the process by which LPCs differentiate into MHs and to establish a protocol to make a large number of MHs ex vivo, which would be useful for drug screening and cell therapy. In addition, considering that Sox9+ biphenotypic cells emerge in human diseased livers (18), if we find a method to activate proliferation and differentiation of Sox9+EpCAM− cells in vivo, the loss of MHs could be compensated in severely damaged livers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Minako Kuwano, Yumiko Tsukamoto, and Yoko Okada for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Grants-in-aid for Young Scientists (B) and for Scientific Research (C) 22790386 and 25460271 (to N. T.) and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 21390365 and 24390304 (to T. M.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

- LPC

- liver progenitor cells

- BC

- bile canaliculus

- CDE

- choline-deficient ethionine-supplemented

- Cyp

- cytochrome P450

- DAPM

- 4–4′-diaminodiphenylmethane

- BDL

- bile duct ligation

- DDC

- 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine

- EpCAM

- epithelial adhesion molecule

- Grhl2

- grainyhead-like 2

- HNF1β

- hepatocyte nuclear factor 1β

- MH

- mature hepatocyte

- PHx

- partial hepatectomy

- Sox9

- Sry HMG box protein 9

- HMG

- high mobility group

- CK

- cytokeratin

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- CPSI

- carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I.

REFERENCES

- 1. Duncan A. W., Dorrell C., Grompe M. (2009) Stem cells and liver regeneration. Gastroenterology 137, 466–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tanaka M., Itoh T., Tanimizu N., Miyajima A. (2011) Liver stem/progenitor cells: their characteristics and regulatory mechanisms. J. Biochem. 149, 231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cardinale V., Wang Y., Carpino G., Mendel G., Alpini G., Gaudio E., Reid L. M., Alvaro D. (2012) The biliary tree–a reservoir of multipotent stem cells. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9, 231–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Okabe M., Tsukahara Y., Tanaka M., Suzuki K., Saito S., Kamiya Y., Tsujimura T., Nakamura K., Miyajima A. (2009) Potential hepatic stem cells reside in EpCAM+ cells of normal and injured mouse liver. Development 136, 1951–1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Suzuki A., Sekiya S., Onishi M., Oshima N., Kiyonari H., Nakauchi H., Taniguchi H. (2008) Flow cytometric isolation and clonal identification of self-renewing bipotent hepatic progenitor cells in adult mouse liver. Hepatology 48, 1964–1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kamiya A., Kakinuma S., Yamazaki Y., Nakauchi H. (2009) Enrichment and clonal culture of progenitor cells during mouse postnatal liver development in mice. Gastroenterology 137, 1114–1126, 1126, e1111–e1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dorrell C., Erker L., Schug J., Kopp J. L., Canaday P. S., Fox A. J., Smirnova O., Duncan A. W., Finegold M. J., Sander M., Kaestner K. H., Grompe M. (2011) Prospective isolation of a bipotential clonogenic liver progenitor cell in adult mice. Genes Dev. 25, 1193–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cardinale V., Wang Y., Carpino G., Cui C. B., Gatto M., Rossi M., Berloco P. B., Cantafora A., Wauthier E., Furth M. E., Inverardi L., Dominguez-Bendala J., Ricordi C., Gerber D., Gaudio E., Alvaro D., Reid L. (2011) Multipotent stem/progenitor cells in human biliary tree give rise to hepatocytes, cholangiocytes, and pancreatic islets. Hepatology 54, 2159–2172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Español-Suñer R., Carpentier R., Van Hul N., Legry V., Achouri Y., Cordi S., Jacquemin P., Lemaigre F., Leclercq I. A. (2012) Liver progenitor cells yield functional hepatocytes in response to chronic liver injury in mice. Gastroenterology 143, 1564–1575 e1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Malato Y., Naqvi S., Schürmann N., Ng R., Wang B., Zape J., Kay M. A., Grimm D., Willenbring H. (2011) Fate tracing of mature hepatocytes in mouse liver homeostasis and regeneration. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4850–4860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boulter L., Govaere O., Bird T. G., Radulescu S., Ramachandran P., Pellicoro A., Ridgway R. A., Seo S. S., Spee B., Van Rooijen N., Sansom O. J., Iredale J. P., Lowell S., Roskams T., Forbes S. J. (2012) Macrophage-derived Wnt opposes Notch signaling to specify hepatic progenitor cell fate in chronic liver disease. Nat. Med. 18, 572–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Michalopoulos G. K. (2010) Liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy: critical analysis of mechanistic dilemmas. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 2–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miyaoka Y., Ebato K., Kato H., Arakawa S., Shimizu S., Miyajima A. (2012) Hypertrophy and unconventional cell division of hepatocytes underlie liver regeneration. Curr. Biol. 22, 1166–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nishikawa Y., Doi Y., Watanabe H., Tokairin T., Omori Y., Su M., Yoshioka T., Enomoto K. (2005) Transdifferentiation of mature rat hepatocytes into bile duct-like cells in vitro. Am. J. Pathol. 166, 1077–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zong Y., Panikkar A., Xu J., Antoniou A., Raynaud P., Lemaigre F., Stanger B. Z. (2009) Notch signaling controls liver development by regulating biliary differentiation. Development 136, 1727–1739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fan B., Malato Y., Calvisi D. F., Naqvi S., Razumilava N., Ribback S., Gores G. J., Dombrowski F., Evert M., Chen X., Willenbring H. (2012) Cholangiocarcinomas can originate from hepatocytes in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 2911–2915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jeliazkova P., Jörs S., Lee M., Zimber-Strobl U., Ferrer J., Schmid R. M., Siveke J. T., Geisler F. (2013) Canonical Notch2 signaling determines biliary cell fates of embryonic hepatoblasts and adult hepatocytes independent of Hes1. Hepatology 57, 2469–2479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yanger K., Zong Y., Maggs L. R., Shapira S. N., Maddipati R., Aiello N. M., Thung S. N., Wells R. G., Greenbaum L. E., Stanger B. Z. (2013) Robust cellular reprogramming occurs spontaneously during liver regeneration. Genes Dev. 27, 719–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nel-Themaat L., Vadakkan T. J., Wang Y., Dickinson M. E., Akiyama H., Behringer R. R. (2009) Morphometric analysis of testis cord formation in Sox9-EGFP mice. Dev. Dyn 238, 1100–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Soriano P. (1999) Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat. Genet. 21, 70–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tanimizu N., Nishikawa M., Saito H., Tsujimura T., Miyajima A. (2003) Isolation of hepatoblasts based on the expression of Dlk/Pref-1. J. Cell Sci. 116, 1775–1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fu D., Wakabayashi Y., Lippincott-Schwartz J., Arias I. M. (2011) Bile acid stimulates hepatocyte polarization through a cAMP-Epac-MEK-LKB1-AMPK pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1403–1408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Senga K., Mostov K. E., Mitaka T., Miyajima A., Tanimizu N. (2012) Grainyhead-like 2 regulates epithelial morphogenesis by establishing functional tight junctions through the organization of a molecular network among claudin3, claudin4, and Rab25. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 2845–2855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang X., Foster M., Al-Dhalimy M., Lagasse E., Finegold M., Grompe M. (2003) The origin and liver repopulating capacity of murine oval cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, Suppl. 1, 11881–11888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Antoniou A., Raynaud P., Cordi S., Zong Y., Tronche F., Stanger B. Z., Jacquemin P., Pierreux C. E., Clotman F., Lemaigre F. P. (2009) Intrahepatic bile ducts develop according to a new mode of tubulogenesis regulated by the transcription factor SOX9. Gastroenterology 136, 2325–2333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kawelke N., Vasel M., Sens C., Au A.v., Dooley S., Nakchbandi I. A. (2011) Fibronectin protects from excessive liver fibrosis by modulating the availability of and responsiveness of stellate cells to active TGF-β. PLoS One 6, e28181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ishikawa T., Factor V. M., Marquardt J. U., Raggi C., Seo D., Kitade M., Conner E. A., Thorgeirsson S. S. (2012) Hepatocyte growth factor/c-met signaling is required for stem-cell-mediated liver regeneration in mice. Hepatology 55, 1215–1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nejak-Bowen K., Orr A., Bowen W. C., Jr., Michalopoulos G. K. (2013) Conditional genetic elimination of hepatocyte growth factor in mice compromises liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy. PLoS One 8, e59836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tanimizu N., Miyajima A., Mostov K. E. (2007) Liver progenitor cells develop cholangiocyte-type epithelial polarity in three-dimensional culture. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 1472–1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thompson M. D., Awuah P., Singh S., Monga S. P. (2010) Disparate cellular basis of improved liver repair in β-catenin-overexpressing mice after long-term exposure to 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine. Am. J. Pathol. 177, 1812–1822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shin S., Walton G., Aoki R., Brondell K., Schug J., Fox A., Smirnova O., Dorrell C., Erker L., Chu A. S., Wells R. G., Grompe M., Greenbaum L. E., Kaestner K. H. (2011) Foxl1-Cre-marked adult hepatic progenitors have clonogenic and bilineage differentiation potential. Genes Dev. 25, 1185–1192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huch M., Dorrell C., Boj S. F., van Es J. H., Li V. S., van de Wetering M., Sato T., Hamer K., Sasaki N., Finegold M. J., Haft A., Vries R. G., Grompe M., Clevers H. (2013) In vitro expansion of single Lgr5+ liver stem cells induced by Wnt-driven regeneration. Nature 494, 247–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Takase H. M., Itoh T., Ino S., Wang T., Koji T., Akira S., Takikawa Y., Miyajima A. (2013) FGF7 is a functional niche signal required for stimulation of adult liver progenitor cells that support liver regeneration. Genes Dev. 27, 169–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sharma N., Low S. H., Misra S., Pallavi B., Weimbs T. (2006) Apical targeting of syntaxin 3 is essential for epithelial cell polarity. J. Cell Biol. 173, 937–948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martin-Belmonte F., Gassama A., Datta A., Yu W., Rescher U., Gerke V., Mostov K. (2007) PTEN-mediated apical segregation of phosphoinositides controls epithelial morphogenesis through Cdc42. Cell 128, 383–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]