Background: The C-terminal tail of the HIV-1 envelope preferentially incorporates arginine over lysine despite the similar physicochemical properties of these two residues.

Results: Conservative arginine to lysine substitutions impair HIV-1 Env functions and virus replication.

Conclusion: Arginine conservation provides unique functions that cannot be provided by lysines.

Significance: These observations conclusively demonstrate unique functional properties for the conserved arginine residues in mediating Env functional properties.

Keywords: HIV-1, Lentivirus, Membrane Proteins, Site-directed Mutagenesis, Viral Replication, C-terminal Tail, Envelope, Arginines

Abstract

A previous study from our laboratory reported a preferential conservation of arginine relative to lysine in the C-terminal tail (CTT) of HIV-1 envelope (Env). Despite substantial overall sequence variation in the CTT, specific arginines are highly conserved in the lentivirus lytic peptide (LLP) motifs and are scarcely substituted by lysines, in contrast to gp120 and the ectodomain of gp41. However, to date, no explanation has been provided to explain the selective incorporation and conservation of arginines over lysines in these motifs. Herein, we address the functions in virus replication of the most conserved arginines by performing conservative mutations of arginine to lysine in the LLP1 and LLP2 motifs. The presence of lysine in place of arginine in the LLP1 motif resulted in significant impairment of Env expression and consequently virus replication kinetics, Env fusogenicity, and incorporation. By contrast, lysine exchanges in LLP2 only affected the level of Env incorporation and fusogenicity. Our findings demonstrate that the conservative lysine substitutions significantly affect Env functional properties indicating a unique functional role for the highly conserved arginines in the LLP motifs. These results provide for the first time a functional explanation to the preferred incorporation of arginine, relative to lysine, in the CTT of HIV-1 Env. We propose that these arginines may provide unique functions for Env interaction with viral or cellular cofactors that then influence overall Env functional properties.

Introduction

Retrovirus envelope (Env)2 proteins are important mediators of virus replication and immunogenicity. In the case of the lentivirus HIV-1, the gp160 precursor is processed into two subunits, gp120 and gp41, that remain non-covalently associated. The gp120 protein interacts with the CD4 receptor of the target cells, mediating the first step of virus entry (1, 2). Because of its exposure at the surface of the virus particle, gp120 is the target of most broadly neutralizing antibodies identified so far and thus represents a key protein in vaccine development (3, 4). The gp41 protein sequences are more conserved than their counterpart gp120 proteins (5), and similar to gp120, they are targeted by neutralizing antibodies, including the panel of well documented broadly neutralizing antibodies (reviewed in Refs. 6 and 7). The gp41 subunit comprises three regions: an ectodomain, a membrane-spanning domain (MSD), and a C-terminal tail (CTT) (Fig. 1A). Despite the substantial overall sequence variation found in gp41, the CTT contains three lentivirus lytic peptides motifs called LLP2, LLP3, and LLP1 (Fig. 1A) that are characterized by a high level of conservation of structural and physicochemical properties among HIV-1 strains and also among different lytic lentiviruses such as HIV-2, simian immunodeficiency virus, and equine infectious anemia virus (5, 8, 9). LLP peptide analogs characteristically adopt an α-helical amphipathic structure in the presence of lipids (5, 10), with LLP1 and LLP2 being further distinguished by their cationic properties.

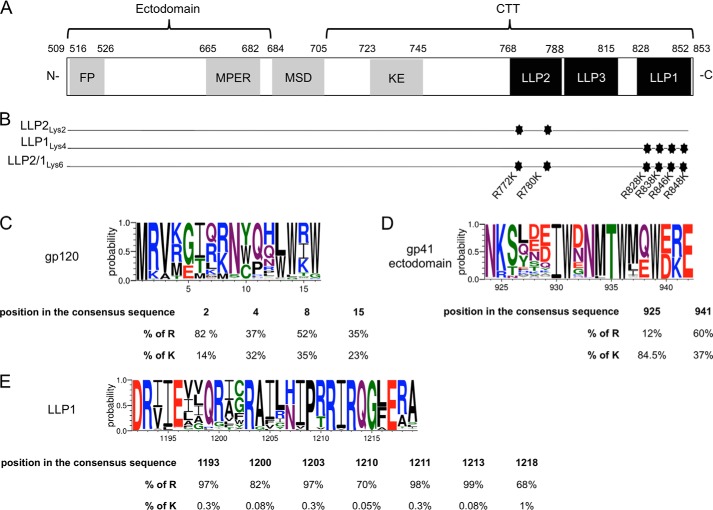

FIGURE 1.

Representation of the CTT mutations and amino acids conservation. A, schematic representation of gp41 from the 89.6 virus strain of HIV-1. The gp41 subunit is divided into three main parts: an ectodomain, a MSD, and a CTT. The residue numbering is based on the gp160 protein. gp120 subunit is not represented. FP, fusion peptide; MPER, membrane proximal external region; KE, Kennedy epitope. B, the most conserved LLP arginines were mutated into lysines. Three mutants were constructed containing two mutations in LLP2 (LLP2Lys2), four mutations in LLP1 (LLP1Lys4), and the third mutant contains all six mutations (LLP2/1Lys6). C–E, logo diagrams representing the relative frequency (y axis) for each amino acid of selected representative regions of gp120 (C), the ectodomain of gp41 (D), and LLP1 (E). Below each logo diagram are represented the percentages of arginine or lysine residue frequencies in the alignment at the indicated position.

Thorough examination of the positively charged residues in the CTT reveals that LLP1 and LLP2 preferentially incorporate arginines instead of lysines, with a marked conservation of arginines at specific residues, suggesting an important but undefined role for these arginines in LLP and Env structure and function (5). Data from the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot knowledgebase indicate that arginines are found in the LLPs at twice the frequency compared with average proteins. Compared with the arginines, lysines are observed on the average 3-fold less frequently in the LLPs as found in other proteins (5). This discrepancy in the relative frequency of incorporation of arginine and lysine in the LLPs as compared with the average protein is relatively unexpected. Arginine and lysine are very similar in their physicochemical properties as both are positively charged polar amino acids of similar structure. The only structural difference between the two residues is the terminal guanidinium group on the side chain in arginine versus an amine group for lysine. In general, the similar charge and relative size of arginine and lysine allow for substitution of one for the other in diverse proteins. For example, the analysis of amino acid substitutions, based on natural evolution of a large sample of different proteins in specific cellular locations (i.e. extracellular, intracellular, or transmembrane), indicates that arginine preferentially exchanges with lysine, especially in transmembrane proteins (11, 12). In the MSD of HIV-1 gp41, it was shown that a highly conserved arginine was functionally substituted by lysine (13), further highlighting the interchangeability of arginine and lysine. Furthermore, alignment of different HIV-1 Env sequences indicate that arginines frequently exchange for lysines in gp120 (Fig. 1C) and in the ectodomain of gp41 (Fig. 1D), but not in the CTT (Fig. 1E). In fact, 36% of the conserved arginines and lysines substitute for each other in gp120 as well as in the gp41 ectodomain, but this rate drops to 8% in the CTT. Taken together, these observations clearly demonstrate that arginine and lysine frequently substitute for each other without any loss of function, even within other domains of Env, thus raising questions about the basis for the preferred presence of arginines over lysines in the CTT.

Even though a significant number of published studies have now demonstrated the importance of the CTT in Env functional and structural properties, to our knowledge, no study has provided any functional explanation for the preferential selection and conservation of arginine in diverse LLP quasispecies. In the present study, to better understand the role of arginine conservation in LLP functions, we performed conservative lysine substitutions of selected conserved arginines. To this end, the most conserved arginines in LLP1 and LLP2 were mutated into lysines, preserving the α-helical amphipathic structure and the net positive charge of the LLP motifs. Surprisingly, the analysis of virus functions indicated that LLP1 and LLP2 motifs were markedly affected by these extremely conservative mutations. These results indicate that arginine and lysine are not functionally exchangeable in the CTT LLP domains and provide for the first time a rational explanation for preferential incorporation of arginines over lysines in the LLP motifs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Alignment, Mutagenesis, and Cloning

Arginine and lysine frequencies in Env were analyzed in Geneious software using the 2011 HIV-1 and SIVcpz Env sequence alignment composed of over 3000 isolates, downloaded from the Los Alamos National Laboratory database. The same alignment was used to create the logo diagrams through WebLogo 3 website (14). The arginine and lysine amino acids were considered as significantly substituting for each other when both represented a minimum of 10% of the alignment, at positions indicating the presence of an arginine or a lysine in the consensus sequence.

The nucleotide sequences containing the three LLP motifs from the 89.6 strain of HIV-1 were synthesized by Geneart (Invitrogen) to introduce specific point mutations. The LLP2Lys2 mutant contains the following mutations to convert selected conserved arginines to lysines: G8528A and G8552A. The LLP1Lys4 mutant contains the following mutations G8696A, G8726A, G8750A, G8756A. The third mutant contains all six mutations and is called LLP2/1Lys6. These mutations have been designed such that the overlapping reading frames are not affected. The wild type LLP motifs were removed from the pUC19 vector containing 89.6 wild type DNA using XhoI restriction sites surrounding the three LLP motifs. The synthesized mutated sequences were then extracted from the pMA vector from Geneart and inserted between XhoI restriction sites in the pUC19 vector containing the parental DNA. The resulting clones were then sequenced (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ) to confirm that these clones efficiently inserted the synthesized sequences in the correct orientation, with no additional mutations beyond the inserted substitutions.

Computational Modeling

A predictive analysis of the 89.6 LLP2 and LLP1 wild type and mutated peptides interaction with the cellular plasma membrane was performed using E(z)-3D software with default parameters (15, 16).

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Virus Production

HEK293T/17 cells (ATCC, Manassas VA) and TZMbl cells (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Germantown, MD) were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% l-glutamine. CEMx174 cells (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program) were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% l-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin. TZMbl cells stably express the luciferase gene under the control of the HIV-1 promoter. HEK293T/17 cells were transfected with 2.5 μg (6-well plate) or 6.25 μg (T25 flask) of DNA using Lipofectamine LTX and Plus reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Infectious HIV-1 89.6 virus was produced by transient transfection of HEK293T/17 cells with the plasmid pUC19–89.6 wild type or mutated. Viral supernatant was retrieved 2 days after transfection and centrifuged at 663 × g for 10 min at 4 °C.

Virus Pelleting and Western Blotting

Three days following the transfection of HEK293T/17 cells in the T25 flask, the viral supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 663 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and then ultracentrifuged at 18,500 × g for 2 h at 4 °C. The viral pellet was then resuspended in MOPS and NuPAGE SDS-PAGE buffer, heated for 10 min at 70 °C, and loaded onto NuPAGE 4–12% bis-tris gel (Invitrogen). Gels were electrophoresed for 50 min at 200 volts followed by transfer on PVDF membrane using the iBlot system (Invitrogen). After transfer, the membranes were cut to allow separate staining of the proteins and were blocked for at least 1 h in 5% blotto. The viral proteins were stained overnight at 4 °C under agitation using mouse monoclonal anti-p24 antibody AG3 diluted 1/250 (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program), rabbit polyclonal anti-gp120 antibody diluted 1/500 (Advanced Biotechnologies Inc., Columbia, MD), or purified immunoglobulin from HIV-infected patients diluted 1/7500 (HIV-IG, NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program). The membranes were then washed three times for 10 min using 1× PBS, 0.025% Tween 20, followed by a 1-h incubation at room temperature with appropriate secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit IgG, anti-mouse IgG, or anti-human IgG coupled to horseradish peroxidase, Sigma). The membranes were then washed three times for 10 min using 1× PBS, 0.025% Tween 20 with the gp120 membrane receiving an additional wash in 1× PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, followed by exposure using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The proteins were visualized using CL-Xposure film (Thermo Scientific).

Western Blot Quantitation

The pelleted viral proteins were quantified by densitometry analysis. For each protein of interest, x-ray exposures were scanned and analyzed using ImageJ (NIH). The gp120 or gp41 bands were selected and the respective integrated area under the densitometry curve was normalized to that of the p24 protein in the corresponding sample to yield the ratio of incorporated Env. This was repeated in three independent experiments, and the results averaged to yield the overall percent of incorporated Env.

Virus Replication Kinetics and Infectivity

A sample of 1 × 104 CEMx174 cells was infected in a 96-well plate with equal amounts of p24 of WT or mutated virus particles, corresponding to a 0.1 multiplicity of infection of the wild type virus. Every 3 days, starting at 3 days post-infection, one-half of the viral supernatant was collected for each point and replaced by the same volume of warm fresh media. The viral supernatants were stored at −80 °C until the end of the experiment. The amount of virus produced from infected cells was determined by quantifying the p24 antigen concentration in the supernatant using HIV-1 p24 antigen capture kit (SAIC, Frederick, MD). Mock infected cell supernatants were used as negative controls in all assays. For the infectivity assay, 2.5 × 104 TZMbl cells were plated in a 96-well plate, allowed to adhere for 6 h, and infected overnight at 37 °C with equal amounts of p24 of WT or mutated virus particles, corresponding to 0.1 multiplicity of infection of the wild type virus. Twelve hours post-infection the media was changed, followed by an additional 36-h incubation before reading the luciferase activity.

Cellular FACS Analysis

A sample of 1 × 105 CEMx174 cells was infected for 1 h at 37 °C with equal amounts of p24 of WT or mutated virus particles, corresponding to 0.1 multiplicity of infection of the wild type virus. Infected cells were then transferred in a 6-well plate. Every 3 days, 2 ml of the media was replaced by the same volume of warm fresh media. Nine days post-infection the cells were harvested and washed twice with FACS wash buffer (5% human serum diluted in 1× PBS) at 4 °C prior antibody staining. For total Env expression analysis, cells were fixed with 2% methanol-free formaldehyde for 30 min on ice, washed twice with FACS wash buffer, and permeabilized using warm Perm buffer (5% FBS, 0.5% saponin in 1× PBS) for 15 min at room temperature prior to antibody staining. Reference monoclonal antibody SAR1 was labeled immediately prior to staining using a Zenon labeling kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instruction. Cells were stained for 30 min on ice with the antibody-zenon complex and p24-FITC antibody (KC57-FITC, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). For cell surface Env analysis, cells were stained with the antibody-zenon complex prior to any fixation or permeabilization. Following three washes with FACS buffer, cells were fixed with 2% methanol-free formaldehyde for 30 min on ice, washed twice with FACS wash buffer, and permeabilized using warm Perm buffer for 15 min at room temperature prior to p24-FITC antibody staining for 30 min, on ice. All the cells were then washed three times with ice-cold Perm buffer, and then resuspended in 2% methanol-free formaldehyde. p24-FITC and Zenon Alexa Fluor 647 fluorescence were analyzed using FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Only p24-positive cells were used for analysis of Env-AF647 fluorescence, except for the mock sample for which the same number as the maximum number of events was analyzed. The SAR1 hybridoma was a kind gift from Dr. Nigel Dimmock (University of Warwick, UK).

Fusogenicity Assay

The fusogenicity assay was adapted from previously published studies (17–21). The day prior to the fusogenicity assay, 2 × 104 TZMbl cells were plated in a 96-well plate. HEK293T/17 cells were transfected with pUC19–89.6 wild type or mutated DNA in a 6-well plate, and after 24 h the transfected cells were harvested using 1× citric saline for 4 min at 37 °C and diluted with 1 volume of 1× PBS. The transfected cells were washed once with media and then resuspended in 1 ml of media. The supernatant from the transfected cells was also harvested as a control and centrifuged at 663 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. A 100-μl sample of transfected HEK293T/17 donor cells or cell-free viral supernatant, supplemented with 10 μm AZT, was added to the monolayer of target TZMbl cells that were pre-treated for 2 h with 10 μm AZT. Donor and target cells were incubated for 6 h at 37 °C before reading the luciferase activity as a measure of cell-cell fusion. To normalize the luciferase activity, half of the cells were analyzed by FACS using IgG1b12 antibody to quantify Env expression at the cell surface, as described above. The luciferase activity was then normalized to the percentage of IgG1b12 positive cells. The normalized luciferase activity is expressed as relative luciferase units (RLUs) per μg of protein in the cell lysate after protein quantification using a Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay Kit.

Standard Neutralization Assay and Luciferase Analysis

A sample of 2.5 × 104 TZMbl cells were plated in a 96-well plate and allowed to adhere for 6 h. Test virus stocks were diluted such that the resulting luciferase activity was at least 1.5 × 105 RLUs and 10 times higher than the background, as recommended by the Los Alamos database protocol for neutralizing antibody assay, and equivalent between WT and mutated viruses. Prior to viral infection of the cells, virus dilutions were mixed with the indicated concentrations of reference antibodies in a U-bottom 96-well plate and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Untreated and antibody-treated virus samples were then incubated with target cells overnight at 37 °C. Media were changed 12 h following the infection and incubated for an additional 36 h before luciferase reading. Forty eight hours post-infection the cells were lysed with 50 μl of cell culture lysis reagent, and luciferase activity was read using the luciferase assay system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI) using an Orion microplate luminometer (Berthold, Oak Ridge, TN).

Statistical Analyses and Calculations

p values were determined using unpaired parametric Student's t test on Prism 6.0a for Mac (GraphPad Prism software, San Diego, CA). NC50 were calculated by performing a non-linear regression curve fit interpolation analysis on Prism 6.0a for Mac (GraphPad Prism).

RESULTS

Design of the LLP Arginine to Lysine Mutations

To evaluate the conservation of amino acids in the LLP regions of HIV-1 CTT, constructed alignments between Env protein sequences representing HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus-1 strains were downloaded from the LANL database and analyzed using Geneious software. The alignment clearly indicated that specific arginines were highly conserved among the different isolates. In fact, based on the HIV-1 89.6 strain sequence, arginines at positions 772 and 780 in LLP2 were present in 95 and 97% of the sequences, respectively, whereas in LLP1 arginines at positions 828, 838, 846, and 848 occurred at a rate of 97, 97, 98, and 99%, respectively, within over 3000 isolates. Based on this alignment, the most conserved arginines from the LLP motifs were selected for mutation. Thus, two arginines in LLP2 and four arginines in LLP1 were mutated into lysines to conserve LLP cationic properties. The specific mutations are depicted in Fig. 1B. Three mutants were constructed containing mutations in LLP2 (LLP2Lys2), LLP1 (LLP1Lys4), or both (LLP2/1Lys6). These mutations did not affect the overall net charge and predicted amphipathic structure of the LLP motifs and hence allowed for specific analyses of a unique function of conserved LLP arginines in the virus life cycle.

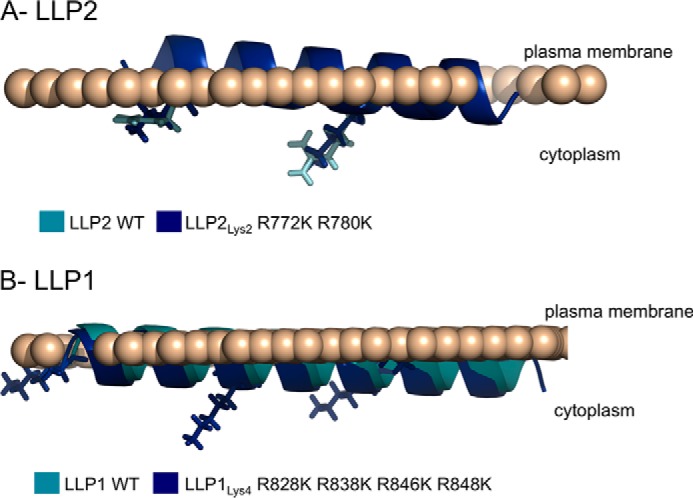

Predictive Modeling of LLP Peptides Interaction with the Plasma Membrane

The three LLP motifs of the CTT of gp41 have been suggested to interact with the plasma membrane (9, 22–28), although the depth and orientation of their insertion inside the phospholipid bilayer has not been described. Recently the computational modeling of the Ez potential has been described as the ability of peptides to insert into lipid membranes (15, 16). The Ez potential is empirically determined using a computational-based method that relies on the peptide length as well as the amino acid composition and frequency of the peptide sequence. It allows a prediction of the ability, depth, and orientation of transmembrane protein insertion inside a lipid bilayer such as the plasma membrane. Thus, we used this modeling method to compare the predicted association of the wild type and mutated LLP2 and LLP1 motifs with the lipid bilayer of the plasma membrane. Because of the size of the gp41 protein, only the LLP peptides were analyzed. Similar to previous observations of the LLP motifs (5), the LLP2 and LLP1 peptides, WT and mutated, are all predicted to adopt a helical conformation in association with the plasma membrane (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the arginine to lysine mutations do not significantly alter the predicted peptide association with the membrane for both LLP2 and LLP1. Although these predicted structures are in the context of only the LLP sequences and not the entire gp41 sequence, the initial data suggest that lysine substitutions would not be expected to markedly change either the LLP1 and LLP2 peptide interactions with the lipid bilayer or the adopted helical conformation. These predictive structural analyses also emphasize the extremely conservative characteristics of these arginine to lysine mutations and further stress the need for an experimental approach to determine the properties of lysine substituted Env proteins.

FIGURE 2.

Predicted interactions of the WT and mutated LLP peptides with the cellular plasma membrane. The 89.6 LLP2 (A) and LLP1 (B) peptide sequences WT or mutated were analyzed using E(z)-3D for a predictive analysis of their interaction with the cellular plasma membrane. The WT peptide is shown in cyan. The arginine to lysine mutants used in this study are represented in blue.

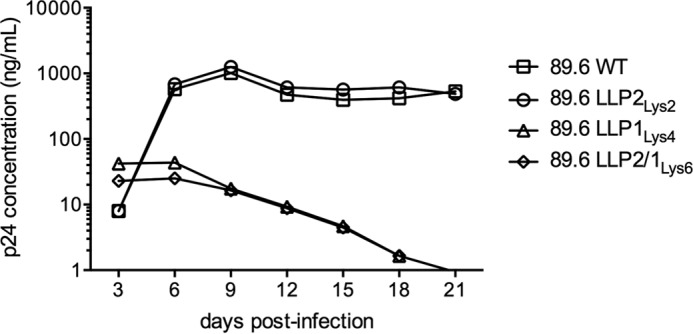

Virus Replication Kinetics and Infectivity

To assess whether the arginine to lysine mutations in the LLP motifs affect virus replication properties, a multiround infection assay was used to compare wild type and mutant virus replication. CEMx174 cells were infected with WT or mutated viruses for 21 days. Starting at 3 days post-infection, viral supernatant was collected every 3 days, and the p24 concentrations in the cell-free viral supernatants were quantified. As shown in Fig. 3, the replication kinetics of the WT virus reached a peak at 9 days post-infection and remained stable beyond that time point. The LLP2Lys2-mutated virus displayed similar replication kinetics and levels compared with the WT virus. In marked contrast, the LLP1Lys4 and LLP2/1Lys6 mutated viruses were significantly impaired, as supernatant p24 levels continuously decreased starting at 6 days post-infection. Thus the virus replication kinetics were affected by arginine to lysine mutations in the LLP1 region, but not in the LLP2 motif. These results indicated that the conserved arginines in the LLP1 region are critical to virus replication, with arginine providing a unique function that cannot be replaced by substituted lysines.

FIGURE 3.

Analysis of the 89.6 virus replication kinetics. CEMx174 cells were infected with equal amounts of p24 of WT or mutated viruses. The data represent the replication kinetics of the 89.6 WT or mutated viruses. Every 3 days the viral supernatant was collected and quantified for p24 concentration. Data represent one among two separate experiments.

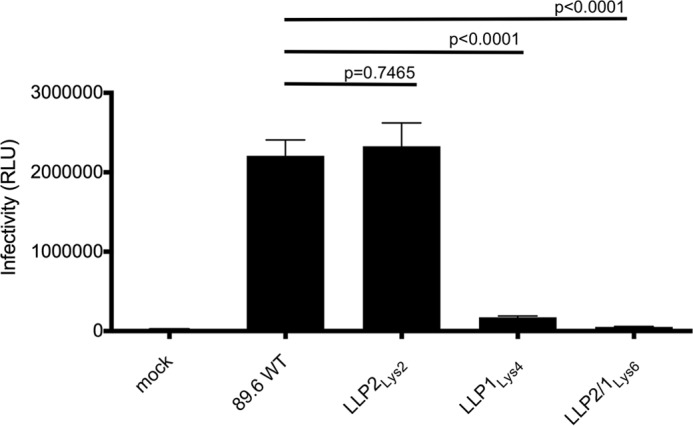

To understand further the mechanism of the replication defect, the virion infectivity of the LLP mutants and wild type virus were compared in a single round infectivity assay. To this end, TZMbl cells were infected with WT or mutated viruses, and the luciferase activity was determined at 48 h post-infection. The results, shown in Fig. 4, indicate that the LLP2Lys2 mutant is equally infectious as the WT virus. In contrast, the LLP1Lys4 and LLP2/1Lys6 mutants display a significantly impaired infectivity with a residual infectivity of 8 and 2%, respectively, in comparison to the WT virion. Thus, as observed for the replication kinetics, virus infectivity was affected by mutations in the LLP1 motif, but not in the LLP2 region. These results confirm that the conserved arginines in the LLP1 motif are of importance to maintain the virus infectivity at a wild type level, whereas the presence of positively charged lysines is sufficient in LLP2.

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of the 89.6 virus infectivity. TZMbl cells were infected with equal amounts of p24 of WT or mutated viruses for 48 h before reading the luciferase activity. The data represent the infectivity of the WT or mutated viruses and were expressed in RLU. Data represents the average of three separate experiments.

Envelope Incorporation

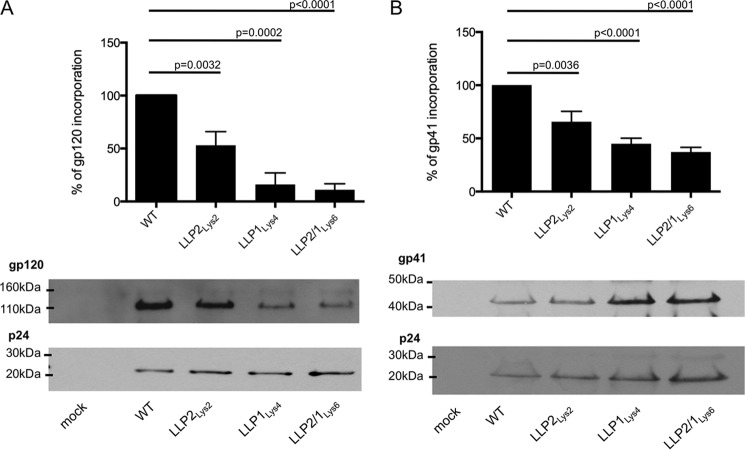

We then sought to determine whether the levels of Env incorporation into virus particles were affected by arginine to lysine mutations. To this end, HEK293T/17 cells were transfected with DNA encoding WT or mutated viruses. Three days following the transfection, the respective viral supernatants were retrieved, pelleted, and analyzed by Western blot with gp120- and p24-specific antibodies or purified immunoglobulin from HIV-infected patients (HIV-IG). Using ImageJ software to analyze the resultant immunoblots, the gp120 and gp41 protein expressions were quantified and normalized to the apparent p24 protein expression. The results indicate that 53% of gp120 (Fig. 5A) and 65% of gp41 (Fig. 5B) were incorporated in the LLP2Lys2-mutated virus, whereas only 16 and 11% of gp120 (Fig. 5A) and 44 and 37% of gp41 (Fig. 5B) were incorporated in the LLP1Lys4 and LLP2/1Lys6 mutants, respectively. Hence, arginine to lysine mutations in the LLP2 and LLP1 motifs were associated with a lower Env incorporation in virions, with the decrease being 3-fold (gp120) and 1.5-fold (gp41) greater with LLP1Lys4 and 5-fold (gp120) and 2-fold (gp41) greater with LLP2/1Lys6 mutations, compared with the LLP2Lys2 mutants.

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of Env incorporation into virions. HEK293T/17 cells were transfected with DNA encoding the HIV-1 virus. Three days after transfection the viral supernatants were pelleted by ultracentrifugation and separated by SDS-PAGE on a 4–12% bis-tris gel. The membrane was incubated with anti-gp120 and anti-p24 antibodies (A) or with HIV Ig (B). Data represented in the graphs have been obtained from the average of three independent experiments, expressed as percentage.

Expression of Env at the Cell Surface

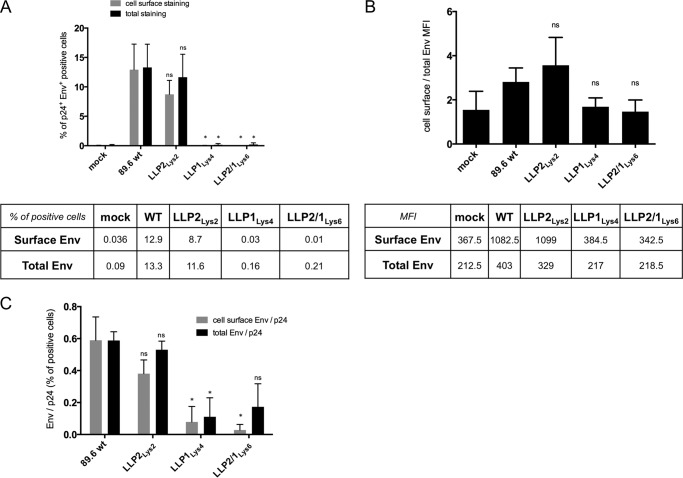

We next examined the levels and distribution of WT and mutated Env expression in physiologically relevant cells that are non-permissive to CTT deletion mutants. Thus, CEMx174 cells were infected with WT or mutated viruses in a multiround infection assay. Based on previous data on viral replication kinetics, the infections were stopped at 9 days post-infection, the time of maximal viral protein production (Fig. 3). The infected cells were then analyzed for Env protein expression at the cell surface and normalized to the total Env expression (both the cell surface and the cytoplasm) in p24-positive cells. The results indicate that 23 and 22% of cells were infected by WT and LLP2Lys2-mutated viruses, respectively, whereas this rate dropped to 1 and 0.8% in the presence of LLP1Lys4- and LLP2/1Lys6-mutated viruses, respectively. Due to the impaired virus infectivity, the expression of Env LLP1Lys4 and LLP2/1Lys6 appeared to be decreased both in total Env staining and in cell surface staining (Fig. 6A). Approximately 8 to 13% of the cells expressed both p24 and WT or LLP2Lys2 Env, whereas in the case of LLP1Lys4 and LLP2/1Lys6 Env, this proportion dropped to below 1% of p24 and Env positive cells (Fig. 6A). However, the ratio analysis of the mean fluorescence intensity indicated that the cell surface relative to total Env expression was decreased by 40 and 48% with the LLP1Lys4 and LLP2/1Lys6 mutants, respectively, in comparison to the WT cells (Fig. 6B). In contrast, the percentage of Env and p24 positive cells in LLP2Lys2 virus-infected cells was only about 25% different from the level observed in cells infected with WT virus (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, the analysis of Env expression per infected cell, determined by calculating the ratio of the percentage of Env positive cells normalized to the percentage of p24 expressing cells, indicate that the expression levels of LLP1Lys4 decreased by 90% at the cell surface and 80% in the total Env staining relative to the WT Env expression (Fig. 6C). Similarly the staining of LLP2/1Lys6 was reduced by 95% at the cell surface and 70% in the total staining. In contrast LLP2Lys2 Env staining was reduced by only 35% at the cell surface and 10% in the total staining by comparison to the wild type (Fig. 6C). These results indicated that arginines in the LLP1 motif were critical to maintain Env expression at the cell surface and intracellularly and that lysine was unable to replace this critical function completely.

FIGURE 6.

Expression of Env at the cell surface and in the cells. CEMx174 cells were infected with equal amounts of p24 of WT or mutated viruses. At 9 days post-infection the cells were stained with SAR1 anti-Env antibodies and then permeabilized for p24 staining (cell surface Env analysis) or permeabilized prior staining with both SAR1 anti-Env and anti-p24 antibodies (total Env analysis). Data represent two independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed for the mutated relative to the wild type Env (ns, non significant; *, p < 0.05). A, percentage of Env expression in p24-positive cells. Gated live cells were analyzed for the percentages of p24-positive and cell surface or the total Env positive population for each mutant, indicated on the y axis. The corresponding percentage data are shown in the table below and represent the average of two independent experiments. B, mean fluorescence intensity of Env positive cells expressed at the cell surface normalized to the mean fluorescence intensity of Env expressed in the cells. Corresponding mean fluorescence intensity data are shown in the table below and represent the average of two independent experiments. C, relative expression of Env per infected cells. The percentage of cell surface or total Env positive cells was normalized to the percentage of p24 positive cells. The data represent the average of two independent experiments.

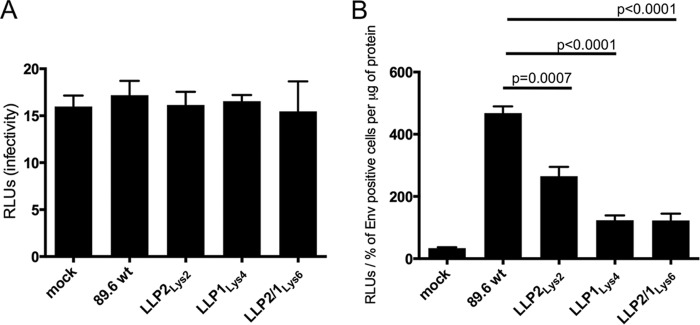

Env-mediated Cell-to-Cell Fusion

We previously reported that non-conservative LLP mutations altered the cell-to-cell fusogenicity properties of Env containing LLP sequences in which arginines were changed to glutamate residues, even when virion-cell fusogenicity was unaltered by the LLP mutations (29, 30). Therefore, we next assayed the ability of lysine-mutated Env, expressed at the cell surface, to mediate cell-to-cell fusion in a fusogenicity assay. To this end, transfected donor HEK293T/17 cells and target TZMbl cells were co-cultivated for 6 h at 37 °C, at which time the luciferase activity was measured to assess cell-cell fusion levels. As the donor cells were transfected with DNA encoding the virus, the target cells were treated with AZT to prevent interference by luciferase activation due to the virus-to-cell fusion. Thus, the cell-free supernatant of transfected HEK293T/17 cells was added to the target TZMbl cells as a control. As expected, the virus produced from the donor cells did not activate the luciferase gene in the target cells (Fig. 7A), indicating a lack of detectable virion-cell fusion under the experimental conditions. Comparison of the specific cell-cell fusogenicity data presented in Fig. 7B clearly indicates a reduction in cell-cell fusogenicity of all of the LLP mutants compared with WT virus. Specifically, the LLP2Lys2 mutant displayed 56% of the cell-cell fusion activity compared with WT, whereas the LLP1Lys4 and LLP2/1Lys6 both displayed ∼26% of the WT Env fusion activity. Thus, these data again demonstrate a unique role for the conserved LLP arginines, in contrast to substituted lysines, in the ability of cell surface Env to mediate fusion with other cells.

FIGURE 7.

Cell-to-cell fusion mediated by Env at the cell surface. A, cell-free supernatant from donor-transfected HEK293T/17 cells was added to the TZMbl target cells for 6 h in the presence of AZT. Luciferase activity is expressed as RLUs. Data represent one among three separate experiments. B, transfected donor HEK293T/17 cells were co-cultured with TZMbl target cells for 6 h in the presence of AZT. Luciferase activity was normalized to the percentage of FACS-stained Env expressed at the cell surface and expressed as RLU/μg of protein in the cell lysate. Data represent one among three separate experiments.

The LLP2 Motif and Env Conformation

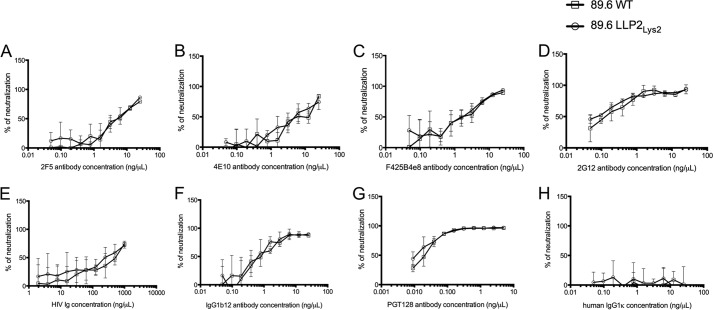

Previous studies have shown that deletions or mutations in the gp41 C-terminal tail can alter antigenicity of the Env protein, presumably reflecting changes caused by the CTT mutations in the conformation of gp120 and the gp41 ectodomain (29–36)(for review see Ref. 7). Importantly, replacement of arginines from the LLP2 motif by negatively charged glutamate is associated with an increased resistance of the virus to neutralization by various reference broadly neutralizing antibodies without affecting virus infectivity and replication kinetics (32). To determine whether the conservative arginine to lysine mutations in LLP2Lys2 would affect Env conformation and epitope exposure at the surface of the virus, neutralization assays were performed with a panel of reference broadly neutralizing antibodies. Due to the low infectivity titers of LLP1Lys4 and LLP2/1Lys6 viruses, these two mutants could not be analyzed in this experiment. A summary of the NC50 for each antibody with WT and LLP2Lys2 viruses is shown in Table 1. The results, shown in Fig. 8, demonstrate that all the tested antibodies similarly neutralized the WT and LLP2Lys2 mutant viruses. The least neutralizing antibody was HIV Ig (Fig. 8E) (NC50 = 206.8 and 184.9 ng/μl with the WT and LLP2Lys2 mutant, respectively (Table 1)), whereas PGT128 was the most efficient neutralizing antibody (Fig. 8G) (NC50 = 0.02 and 0.013 ng/μl with WT and LLP2Lys2 mutant, respectively (Table 1)). As expected human IgG1κ did not neutralize the viruses (Fig. 8H). Hence, the presence of lysines in place of arginines in the LLP2 domain did not cause apparent changes in Env antigenicity, presumably reflecting a conservation of Env conformation and epitope exposure in the lysine-substituted mutants.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics and NC50 of the broadly neutralizing antibodies with WT or LLP2Lys2-mutated viruses

| Targeted protein | Antibody | Type of antibody | Targeted epitope | NC50 (ng/μl)a |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | LLP2Lys2 | ||||

| gp41 | 2F5 | Monoclonal | Membrane proximal external region | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 5.9 ± 1.1 |

| 4E10 | Monoclonal | Membrane proximal external region | 6.3 ± 2.9 | 4.5 ± 2.07 | |

| gp120 | F425B4e8 | Monoclonal | V3 loop | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 1.96 ± 0.6 |

| 2G12 | Monoclonal | gp120 carbohydrates | 0.15 ± 0.08 | 0.08 ± 0.002 | |

| HIV Ig | Polyclonal | NAb | 206.8 ± 106.7 | 184.9 ± 110.2 | |

| IgG1b12 | Monoclonal | CD4 binding site | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | |

| PGT128 | Monoclonal | gp120 carbohydrates | 0.02 ± 0.005 | 0.013 ± 0.004 | |

| Human IgG1 K | Monoclonal | No binding | |||

a The NC50 were calculated from the standard neutralization assay experiments.

b NA, data not available.

FIGURE 8.

Neutralization of the WT and LLP2Lys2-mutated viruses by broadly neutralizing antibodies. The 89.6 WT or LLP2Lys2 viruses were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with the indicated concentrations of 2F5 (A), 4E10 (B), F425B4e8 (C), 2G12 (D), HIV Ig (E), IgG1b12 (F), PGT128 (G), or human IgG1κ (negative control, H) antibodies prior to infection of TZMbl cells. Luciferase activity was analyzed 48 h post-infection. The results are expressed as a percentage of neutralization and are representative of two to three separate experiments.

DISCUSSION

The present study was designed to evaluate the functional equivalence of lysine residues substituted for highly conserved arginines identified in the LLP sequences of HIV-1 Env. Lysine substitutions of the selected conserved arginines maintained similar physicochemical and predicted conformational properties, differing only in the presence of a side chain containing either a positively charged amino (lysine) or guanidinium (arginine) group. The results of these studies demonstrate for the first time that conservative lysine substitutions of highly conserved arginines in LLP domains can markedly alter Env functional properties, indicating a unique functional role for these LLP arginines. Specifically, we showed that the most conserved arginines in the LLP1 motif were necessary to Env fusogenicity and to retain a correct Env expression and consequently Env incorporation, virus replication kinetics, and infectivity. Maintenance of a net positive charge through lysine substitutions did not preserve the arginine-associated LLP1 functions. In contrast, arginine to lysine substitutions in the LLP2 region affected only Env incorporation and cell-to-cell fusogenicity. Env expression, virus replication kinetics, and infectivity, as well as the virus neutralization were similar between the WT- and LLP2Lys2-mutated viruses.

Although similar to lysine in structure and charge, arginine contains a guanidinium group on the side chain that can participate in more hydrogen bonds than the single amino group of lysine (37, 38). Based on these basic parameters, the inability of lysine to substitute completely for arginine in LLP functions may be attributed to alterations in the interactions of the LLP sequences with membrane lipids or with protein cofactors, viral or cellular. Each of these potential interactions is discussed below.

Peptide analogs of HIV-1 LLP domains have been shown to associate rapidly in vitro with lipid vesicles, and reductions in LLP-positive charge can markedly reduce LLP binding to and disruption of lipid membranes (39–41). Interestingly, simulation studies indicate that arginines and lysines interact distinctly with lipid membranes, resulting in enhanced binding and membrane perturbation of arginines with the lipid bilayer compared with lysines (42, 43). To assess the role of conserved LLP arginines in mediating interactions with membrane lipids, we computationally modeled the predicted association of membrane lipids with WT and lysine-substituted LLP1 and LLP2 sequences. However, the lipid membrane modeling did not predict alterations in the membrane lipid interaction, or in the adopted helical conformation for the arginine to lysine mutant sequences, suggesting that the changes in Env functional properties cannot be readily correlated with changes in calculated structure and LLP-membrane lipid associations caused by lysine substitutions of conserved arginine residues.

A recent study by Tristram-Nagle and colleagues (41) found that LLP2 peptide analogs, regardless of sequence, bound to and altered the structure of membranes that mimicked the lipid content of the T lymphocytes, but the same peptides bound only weakly to HIV virion membrane mimics without altering the membrane structure. Their findings provide a framework with which to consider the current results as it may explain that the Env conformation and virus neutralization are not affected by LLP2 mutations. Initially, these results are difficult to reconcile with previous experiments showing that CTT modifications impair gp120 and gp41 ectodomain conformations (32, 35), but it is plausible that the non-conservative mutations and CTT deletions performed in these previous studies impair Env oligomerization (44, 45) or Env-Gag interaction (46, 47), rather than interaction with viral membrane, in contrast to the more conservative arginine to lysine substitutions performed in the present study.

Furthermore, the cell-to-cell fusogenicity assay reveals a defect for the three LLP mutants, suggesting a common mechanism such as impaired stability of the interaction between gp120 and gp41 (48) and/or of the trimer, as shown in the case of simian immunodeficiency virus (49), as well as impaired oligomerization (44, 45). However, it is not clear how these defects would spare LLP2Lys2 virus infectivity relative to cell-to-cell fusogenicity. Alternatively, impaired transitional conformational changes of Env occurring during the fusion process could contribute to these defects. As cell-to-cell and virus-to-cell fusions are two different phenomena (50, 51), it is possible that the Env conformational changes involved in these processes are also different and that the LLP2Lys2 mutations affect Env conformational changes during cell-to-cell fusion but not during virus-to-cell fusion. The question of how two point mutations significantly alter Env-mediated cell-to-cell fusogenicity without apparent effect on viral infectivity (which is also an Env-driven process) has been refractory to mutagenesis studies. Based on the study by Tristram-Nagle and colleagues (41) it is possible that mutations in LLP2 do not affect viral infectivity because the LLP2 region interacts only weakly with the viral membrane, regardless of the LLP2 sequence. In the context of the cell membrane, the LLP2 sequence has a profound effect on its interaction with the lipid membrane, with non-conservative glutamate substitutions causing large changes in the measured membrane structural and mechanical parameters (41). This differential interaction of LLP2 with viral and cellular membranes could contribute to the observed phenotypic differences of the current LLP2 mutations on Env conformational changes in cell-to-cell relative to virus-to-cell fusion. Given that we observed no effect of lysine substitution on the calculated interaction of the LLP2 and LLP1 peptides with the membrane, it could be interesting to consider that the observed differences in cellular fusogenicity may be due to alterations in the interactions of the CTT with cellular cofactors. Indeed, arginine-mediated phosphate interactions have been demonstrated to be sensitive even to conservative substitutions by lysine (37).

The CTT has also been shown to interact with numerous cellular proteins (described in Refs. 7, 52, and 53), and most of these interactions occur through the LLP domains. As arginine has been shown to bind more avidly to phosphate than lysine (37), post-translational phosphorylation of cellular proteins interacting with the CTT (54) could allow their stable association with arginine-containing WT Env, but not with the mutated Env. As LLP2-mutated Env in the present study only impaired Env functions (incorporation and cell-to-cell fusion), in contrast to LLP1-mutated Env that demonstrated impaired expression, the current results suggest that the arginines in these two motifs are likely to be involved in independent protein-protein interactions. In this perspective, it is interesting to note that cellular proteins reported to interact with the CTT and involved in Env sorting interact through the LLP1 motif (reviewed in Ref. 53), whereas previous studies have demonstrated that sequences in LLP2 are involved in interactions with the HIV matrix protein (55, 56) and that the CTT is required for Env virion incorporation in a cell-type dependent manner (57). All together these observations suggest that impaired sorting of LLP1 mutants could potentially result in aberrant positioning of Env to the lysosomes, for example, concordant with the decreased Env expression both at the cell surface and in the cells, as detected by FACS, and consequently responsible for the decreased Env incorporation and virus infectivity. In support of this hypothesis, specific deletions in LLP1 have been shown to decrease Env protein stability and were suggested to be due to impaired interaction with cellular proteins (58). Similarly, the presence of lysine in LLP2 could impair interaction of gp41 with viral partners such as Gag (55, 56). Mutation of Gag has been shown to specifically decrease gp120 levels in virus particles without affecting gp41 (48). In this study, the authors experimentally exclude gp120 shedding and discuss the possibility that Gag interaction with gp41 within an intracellular assembly compartment could stabilize the interaction between these two subunits. This interpretation is consistent with the greater decrease of gp120 relative to gp41 in mutated virus particles observed in our study. In accordance, the suggested impaired trafficking of the LLP1-mutated Env could also impair the Gag-Env interaction by limiting their interfacing during their trafficking toward the plasma membrane and would explain that LLP1-mutated virus particles also incorporate less gp120 relative to gp41. These possible mechanisms require further study.

In summary, the current study for the first time reveals a functional basis for the preferential incorporation and stringent conservation of arginine, relative to lysine, in the LLP1 and LLP2 domains of the HIV-1 CTT. In addition, these observations are consistent with our previous studies (29, 30, 32) in that the mutations differentially affect LLP1 and LLP2 functions. The data demonstrate conclusively the critical functional role of arginine, and more specifically the guanidinium moiety, in mediating CTT and Env functions. Further studies are required to assess the importance of these conserved LLP arginines in the interaction of the CTT with cellular and viral protein cofactors and to determine the impact of these interactions on Env functional properties.

Acknowledgments

The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: TZM-bl from Dr. John C. Kappes, Dr. Xiaoyun Wu, and Tranzyme Inc.; 174xCEM from Dr. Peter Cresswell; Zidovudine, monoclonal antibody to HIV-1 p24 (AG3.0) from Dr. Jonathan Allan; HIV-1 gp120 monoclonal antibody (F425 B4e8) from Dr. Marshall Posner and Dr. Lisa Cavacini; HIV-1 gp120 monoclonal antibody (IgG1 b12) from Dr. Dennis Burton and Carlos Barbas; catalog number 3957, HIV-IG from North American Biologicals, Inc. and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; HIV-1 gp41 monoclonal antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 from Dr. Hermann Katinger; HIV-1 gp120 monoclonal antibody (2G12) from Dr. Hermann Katinger. The PGT128 antibody was provided by the IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Consortium. We thank Dr. Phalguni Gupta and his lab members for performing the p24 quantification assays.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant 5R01 AI087533 (to R. C. M.) from the NIAID.

- Env

- envelope

- CTT

- C-terminal tail

- LLP

- lentivirus lytic peptide

- MSD

- membrane-spanning domain

- AZT

- azidothymidine

- RLU

- relative luciferase units

- WT

- wild type

- bis-tris

- [Bis (2-hydroxyethyl) imino-tris (hydroxymethyl) methane-HCl]

- gp

- glycoprotein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wilen C. B., Tilton J. C., Doms R. W. (2012) Molecular mechanisms of HIV entry. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 726, 223–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blumenthal R., Durell S., Viard M. (2012) HIV entry and envelope glycoprotein-mediated fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 40841–40849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mascola J. R., Montefiori D. C. (2010) The role of antibodies in HIV vaccines. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28, 413–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Gils M. J., Sanders R. W. (2013) Broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1. Templates for a vaccine. Virology 435, 46–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steckbeck J. D., Craigo J. K., Barnes C. O., Montelaro R. C. (2011) Highly conserved structural properties of the C-terminal tail of HIV-1 gp41 protein despite substantial sequence variation among diverse clades. Implications for functions in viral replication. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 27156–27166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Denner J. (2011) Towards an AIDS vaccine. The transmembrane envelope protein as target for broadly neutralizing antibodies. Hum. Vaccin. 7, 4–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Steckbeck J. D., Kuhlmann A. S., Montelaro R. C. (2013) C-terminal tail of human immunodeficiency virus gp41. Functionally rich and structurally enigmatic. J. Gen. Virol. 94, 1–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miller M. A., Garry R. F., Jaynes J. M., Montelaro R. C. (1991) A structural correlation between lentivirus transmembrane proteins and natural cytolytic peptides. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 7, 511–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Srinivas S. K., Srinivas R. V., Anantharamaiah G. M., Segrest J. P., Compans R. W. (1992) Membrane interactions of synthetic peptides corresponding to amphipathic helical segments of the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 envelope glycoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 7121–7127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Costin J. M., Rausch J. M., Garry R. F., Wimley W. C. (2007) Viroporin potential of the lentivirus lytic peptide (LLP) domains of the HIV-1 gp41 protein. Virol. J. 4, 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Betts M. J., Russell R. B. (2007) in Bioinformatics for Geneticists (Barnes M. R., ed) 2nd Ed., pp. 311–342, Wiley, New York [Google Scholar]

- 12. Plumpton M., Barnes M. R. (2007) in Bioinformatics for Geneticists (Barnes M. R., ed) 2nd Ed., pp. 249–280, Wiley, New York [Google Scholar]

- 13. Long Y., Meng F., Kondo N., Iwamoto A., Matsuda Z. (2011) Conserved arginine residue in the membrane-spanning domain of HIV-1 gp41 is required for efficient membrane fusion. Protein Cell 2, 369–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J. M., Brenner S. E. (2004) WebLogo. A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Senes A., Chadi D. C., Law P. B., Walters R. F., Nanda V., Degrado W. F. (2007) E15(z), a depth-dependent potential for assessing the energies of insertion of amino acid side-chains into membranes. Derivation and applications to determining the orientation of transmembrane and interfacial helices. J. Mol. Biol. 366, 436–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schramm C. A., Hannigan B. T., Donald J. E., Keasar C., Saven J. G., Degrado W. F., Samish I. (2012) Knowledge-based potential for positioning membrane-associated structures and assessing residue-specific energetic contributions. Structure 20, 924–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cheng D. C., Zhong G. C., Su J. X., Liu Y. H., Li Y., Wang J. Y., Hattori T., Ling H., Zhang F. M. (2010) A sensitive HIV-1 envelope induced fusion assay identifies fusion enhancement of thrombin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 1780–1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cunyat F., Curriu M., Marfil S., García E., Clotet B., Blanco J., Cabrera C. (2012) Evaluation of the cytopathicity (fusion/hemifusion) of patient-derived HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins comparing two effector cell lines. J. Biomol. Screen. 17, 727–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martínez J. P., Bocharov G., Ignatovich A., Reiter J., Dittmar M. T., Wain-Hobson S., Meyerhans A. (2011) Fitness ranking of individual mutants drives patterns of epistatic interactions in HIV-1. PLoS One 6, e18375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Paintsil E., Dutschman G. E., Hu R., Grill S. P., Lam W., Baba M., Tanaka H., Cheng Y. C. (2007) Intracellular metabolism and persistence of the anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity of 2′,3′-didehydro-3′-deoxy-4′-ethynylthymidine, a novel thymidine analog. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 3870–3879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Paintsil E., Grill S. P., Dutschman G. E., Cheng Y. C. (2009) Comparative study of the persistence of anti-HIV activity of deoxynucleoside HIV reverse transcriptase inhibitors after removal from culture. AIDS Res. Ther. 6, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haffar O. K., Dowbenko D. J., Berman P. W. (1988) Topogenic analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein, gp160, in microsomal membranes. J. Cell Biol. 107, 1677–1687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haffar O. K., Dowbenko D. J., Berman P. W. (1991) The cytoplasmic tail of HIV-1 gp160 contains regions that associate with cellular membranes. Virology 180, 439–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang C., Spies C. P., Compans R. W. (1995) The human and simian immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein transmembrane subunits are palmitoylated. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 9871–9875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kliger Y., Shai Y. (1997) A leucine zipper-like sequence from the cytoplasmic tail of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein binds and perturbs lipid bilayers. Biochemistry 36, 5157–5169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen S. S., Lee S. F., Wang C. T. (2001) Cellular membrane-binding ability of the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope transmembrane protein gp41. J. Virol. 75, 9925–9938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moreno M. R., Giudici M., Villalaín J. (2006) The membranotropic regions of the endo and ecto domains of HIV gp41 envelope glycoprotein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1758, 111–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Steckbeck J. D., Sun C., Sturgeon T. J., Montelaro R. C. (2010) Topology of the C-terminal tail of HIV-1 gp41. Differential exposure of the Kennedy epitope on cell and viral membranes. PLoS One 5, e15261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kalia V., Sarkar S., Gupta P., Montelaro R. C. (2003) Rational site-directed mutations of the LLP-1 and LLP-2 lentivirus lytic peptide domains in the intracytoplasmic tail of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 indicate common functions in cell-cell fusion but distinct roles in virion envelope incorporation. J. Virol. 77, 3634–3646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Newman J. T., Sturgeon T. J., Gupta P., Montelaro R. C. (2007) Differential functional phenotypes of two primary HIV-1 strains resulting from homologous point mutations in the LLP domains of the envelope gp41 intracytoplasmic domain. Virology 367, 102–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Edwards T. G., Wyss S., Reeves J. D., Zolla-Pazner S., Hoxie J. A., Doms R. W., Baribaud F. (2002) Truncation of the cytoplasmic domain induces exposure of conserved regions in the ectodomain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein. J. Virol. 76, 2683–2691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kalia V., Sarkar S., Gupta P., Montelaro R. C. (2005) Antibody neutralization escape mediated by point mutations in the intracytoplasmic tail of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41. J. Virol. 79, 2097–2107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wyss S., Dimitrov A. S., Baribaud F., Edwards T. G., Blumenthal R., Hoxie J. A. (2005) Regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein fusion by a membrane-interactive domain in the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 79, 12231–12241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jiang J., Aiken C. (2007) Maturation-dependent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particle fusion requires a carboxyl-terminal region of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 81, 9999–10008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Joyner A. S., Willis J. R., Crowe J. E., Jr., Aiken C. (2011) Maturation-induced cloaking of neutralization epitopes on HIV-1 particles. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Durham N. D., Yewdall A. W., Chen P., Lee R., Zony C., Robinson J. E., Chen B. K. (2012) Neutralization resistance of virological synapse-mediated HIV-1 infection is regulated by the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 86, 7484–7495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Copley R. R., Barton G. J. (1994) A structural analysis of phosphate and sulphate binding sites in proteins. Estimation of propensities for binding and conservation of phosphate binding sites. J. Mol. Biol. 242, 321–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sakai N., Futaki S., Matile S. (2006) Anion hopping of (and on) functional oligoarginines: from chloroform to cells. Soft Matter 2, 636–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miller M. A., Cloyd M. W., Liebmann J., Rinaldo C. R., Jr., Islam K. R., Wang S. Z., Mietzner T. A., Montelaro R. C. (1993) Alterations in cell membrane permeability by the lentivirus lytic peptide (LLP-1) of HIV-1 transmembrane protein. Virology 196, 89–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tencza S. B., Miller M. A., Islam K., Mietzner T. A., Montelaro R. C. (1995) Effect of amino acid substitutions on calmodulin binding and cytolytic properties of the LLP-1 peptide segment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane protein. J. Virol. 69, 5199–5202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Boscia A. L., Akabori K., Benamram Z., Michel J. A., Jablin M. S., Steckbeck J. D., Montelaro R. C., Nagle J. F., Tristram-Nagle S. (2013) Membrane structure correlates to function of LLP2 on the cytoplasmic tail of HIV-1 gp41 protein. Biophys. J. 105, 657–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu Z., Cui Q., Yethiraj A. (2013) Why do arginine and lysine organize lipids differently? Insights from coarse-grained and atomistic simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 12145–12156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li L., Vorobyov I., Allen T. W. (2013) The different interactions of lysine and arginine side chains with lipid membranes. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 11906–11920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee S. F., Wang C. T., Liang J. Y., Hong S. L., Huang C. C., Chen S. S. (2000) Multimerization potential of the cytoplasmic domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein gp41. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 15809–15819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhu Y., Lu L., Chao L., Chen Y. H. (2007) Important changes in biochemical properties and function of mutated LLP12 domain of HIV-1 gp41. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 70, 311–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cosson P. (1996) Direct interaction between the envelope and matrix proteins of HIV-1. EMBO J. 15, 5783–5788 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Murakami T. (2012) Retroviral env glycoprotein trafficking and incorporation into virions. Mol. Biol. Int. 2012, 682850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Davis M. R., Jiang J., Zhou J., Freed E. O., Aiken C. (2006) A mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein destabilizes the interaction of the envelope protein subunits gp120 and gp41. J. Virol. 80, 2405–2417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vzorov A. N., Compans R. W. (2011) Effects of stabilization of the gp41 cytoplasmic domain on fusion activity and infectivity of SIVmac239. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 27, 1213–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yoder A., Yu D., Dong L., Iyer S. R., Xu X., Kelly J., Liu J., Wang W., Vorster P. J., Agulto L., Stephany D. A., Cooper J. N., Marsh J. W., Wu Y. (2008) HIV envelope-CXCR4 signaling activates cofilin to overcome cortical actin restriction in resting CD4 T cells. Cell 134, 782–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Miyauchi K., Kim Y., Latinovic O., Morozov V., Melikyan G. B. (2009) HIV enters cells via endocytosis and dynamin-dependent fusion with endosomes. Cell 137, 433–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Postler T. S., Desrosiers R. C. (2013) The tale of the long tail. The cytoplasmic domain of HIV-1 gp41. J. Virol. 87, 2–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. da Silva E. S., Mulinge M., Bercoff D. P. (2013) The frantic play of the concealed HIV envelope cytoplasmic tail. Retrovirology 10, 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hornbeck P. V., Kornhauser J. M., Tkachev S., Zhang B., Skrzypek E., Murray B., Latham V., Sullivan M. (2012) PhosphoSitePlus. A comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D261–D270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Freed E. O., Martin M. A. (1996) Domains of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into virions. J. Virol. 70, 341–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Murakami T., Freed E. O. (2000) Genetic evidence for an interaction between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and α-helix 2 of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 74, 3548–3554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Murakami T., Freed E. O. (2000) The long cytoplasmic tail of gp41 is required in a cell type-dependent manner for HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein incorporation into virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 343–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lee S. F., Ko C. Y., Wang C. T., Chen S. S. (2002) Effect of point mutations in the N terminus of the lentivirus lytic peptide-1 sequence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane protein gp41 on Env stability. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15363–15375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]