Background: Septins are filament-forming proteins involved in membrane-remodeling events.

Results: Two crystal structures of a septin with the highest resolution to date reveal the phenomenon of β-strand slippage.

Conclusion: A novel mechanistic framework for the influence of the nature of the bound nucleotide and the presence of Mg2+ in septins is proposed.

Significance: Identification of strand slippage might contribute to elucidating the mechanism of septin association with membranes.

Keywords: Crystal Structure, GTPase, Protein Conformation, Protein Structure, X-ray Crystallography, Conformational Change, Filament, GTPase Domain, Schistosoma, Septin

Abstract

Septins are filament-forming GTP-binding proteins involved in important cellular events, such as cytokinesis, barrier formation, and membrane remodeling. Here, we present two crystal structures of the GTPase domain of a Schistosoma mansoni septin (SmSEPT10), one bound to GDP and the other to GTP. The structures have been solved at an unprecedented resolution for septins (1.93 and 2.1 Å, respectively), which has allowed for unambiguous structural assignment of regions previously poorly defined. Consequently, we provide a reliable model for functional interpretation and a solid foundation for future structural studies. Upon comparing the two complexes, we observe for the first time the phenomenon of a strand slippage in septins. Such slippage generates a front-back communication mechanism between the G and NC interfaces. These data provide a novel mechanistic framework for the influence of nucleotide binding to the GTPase domain, opening new possibilities for the study of the dynamics of septin filaments.

Introduction

Septins are a family of highly conserved GTP-binding proteins found in a variety of eukaryotes (1). The number of septin members varies according to the organism, ranging from one in some algae (2, 3) to 13 in humans (4). The need for a variety of septins in most species seems to be related to their ability to form hetero-oligomeric polymers or filaments. These subsequently organize into higher order structures, such as bundles, gauzes, and rings (5, 6), and have recently been described as novel components of the cytoskeleton (1).

Septin filaments are involved in important cellular processes, such as cytokinesis, exocytosis, and membrane remodeling, and in the formation of diffusion barriers. They have also been implicated as scaffolds to recruit proteins to specific subcellular localizations and in the formation of cage-like structures for bacterial entrapment (1, 7, 8). Despite the increasing number of roles attributed to septins, many of the details of the mechanisms by which they act remain to be elucidated (8). In particular, the complex relationship between polymerization, bundling, GTP binding, nucleotide hydrolysis, and membrane association and dissociation is far from fully understood.

Most septins share three common structural domains: a highly conserved GTPase domain, a variable N-terminal region, and a C-terminal domain often predicted to form coiled-coil structures (9). A polybasic region is found in most septin sequences, between the N-terminal and the GTPase domain, and is associated with phospholipid binding (10, 11). Septins belong to the superfamily of P-loop GTPases, and the GTPase domain itself contains three of the five GTPase conserved motifs. G1 (GXXXXGK(S/T)), also known as the Walker A-box, is responsible for forming the P-loop itself and interacting with the phosphate groups of the nucleotide. G3 (DXXG) is part of the switch II region and is important for binding magnesium and interacting directly with the γ-phosphate of GTP. Finally, the G4 motif (AKAD) is responsible for imparting GTP binding specificity (12). The data currently available for septins from x-ray crystallography are restricted to a limited number of structures at relatively low resolution (12–16). Furthermore, for the most part, these structures correspond to the GTPase domain alone rather than the full molecule. Despite the fact that these results have provided useful insight into how a septin filament forms from its component monomers, they are limited as a consequence of all being mammalian in origin, and therefore little is known about the diversity of structures across different phyla.

Schistosoma mansoni is one of the major species responsible for the neglected tropical disease schistosomiasis, which affects over 230 million people in 77 countries worldwide (17). The genomic data recently published for this flatworm has opened up a series of novel opportunities for the study of unique features of its metabolism and evolution. Furthermore, it brings with it also the possibility of identifying new drug and/or vaccine targets (18). Recently, four different septins were identified and described in this organism (19), and these have been classified into three of the four existing subgroups (20–22).

Here, we describe the structure of the GTPase domain of one of these S. mansoni septins (SmSEPT10) as determined by x-ray crystallography. As such, this is the first report of a structure for a non-mammalian septin. The high resolution achieved for SmSEPT10G (the GTPase domain of SmSEPT10) bound to GDP (1.93 Å) and to GTP (2.1 Å) allows for an unprecedented and detailed analysis of septin structure. This provides surprising insights into their dynamics, which are expected to be relevant to a fuller understanding of the ways in which septins interact with other cellular components, such as membranes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression and Purification of Recombinant SmSEPT10 and SmSEPT10G

SmSEPT10 cDNA was amplified from RNA extracted from adult worms and cloned into the pET28a(+) vector as described previously (19). SmSEPT10G was obtained using the previous construct as template to a new PCR with primers flanking the GTPase domain (residues 39–306) of SmSEPT10. SmSEPT10G was also subcloned into the pET28a(+) vector, which introduces a His tag at the N terminus of the protein.

All constructs were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3) strain. Bacterial cells were grown at 37 °C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) until they reached an OD of 0.6–0.8. The cell suspension was cooled to 18 °C for 20 min, and isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 0.4 mm. Protein expression was performed overnight at 18 °C with continuous shaking.

The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 30 min and suspended in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 800 mm NaCl, 5 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10% glycerol (suspension buffer). After lysis by sonication (10 cycles of 25-s bursts followed by 35 s of rest), the lysed cells were centrifuged at 20,000 × g at 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatant containing the soluble proteins was loaded onto a column packed with Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Qiagen), pre-equilibrated with suspension buffer. The column was incubated for 30 min and washed with suspension buffer, followed by a wash step with standard buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 300 mm NaCl, 5 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10% glycerol) and a wash step with standard buffer supplemented with 10 mm imidazole. The proteins were eluted in standard buffer containing 0.5 m imidazole. Further purification was carried out by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 column coupled to an ÄKTA purifier system (GE Healthcare), from which they were eluted in standard buffer. The integrity and purity of the proteins were assessed by SDS-PAGE.

GTP Hydrolysis Assay

The hydrolytic activity assay was performed with 15 μm SmSEPT10 in standard buffer. The samples were incubated with a 3-fold excess of GTP (45 μm) in the presence of 5 mm MgCl2. Aliquots were removed after different time intervals and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Nucleotides were extracted from the protein samples according to the method described by Seckler et al. (23) with minor modifications. Ice-cold HClO4 (final concentration 0.5 m) was added to the protein samples, and after a 10-min incubation period, the protein pellet was separated by centrifugation at 20,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was buffered and neutralized with ice-cooled solutions of KOH 3 m (one-sixth volume), K2HPO4 1 m (one-sixth volume), and acetic acid (0.5 m) (final concentration). The nucleotides were analyzed by HPLC after a centrifugation step (20,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min). The GTP was separated from GDP by anion exchange chromatography on a Protein Pack DEAE 5 PW 7.5 mm × 7.5 cm column (Waters) driven by a Waters 2695 chromatography system. The column was equilibrated in 25 mm Tris at pH 8.0, and 200 μl of each sample were loaded into the system and eluted with a linear NaCl gradient (0.1–0.45 m in 10 min) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min at room temperature. The absorbance was monitored at 253 nm. The retention times of each guanine nucleotide were determined using a mixture of 15 μm GDP and 15 μm GTP in the same sample buffer after treatment with HClO4.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

The nucleotide binding affinity of SmSEPT10G was determined at 18 °C using a VP-ITC4 calorimeter (MicroCal). Measurements were performed in standard buffer in the presence or absence of 5 mm MgCl2. The sample cell was loaded with 15–25 μm SmSEPT10G, and the guanine nucleotide (GTP or GDP at a concentration of 2–3 mm) was titrated in a series of 45 injections of 5 μl each to achieve a complete binding isotherm. All ITC experiments were repeated at least twice, and the heat of dilution (obtained by titration of the nucleotide into the buffer) was subtracted from the binding curve. The dissociation constant (Kd) and enthalpy were obtained with the software Microcal® ITC OriginTM. Curve fitting was performed assuming a one-binding site model, and the reaction stoichiometry was fixed (n = 1) to enable proper curve fitting due to the low affinity observed (24).

31P NMR Spectroscopy

1 mm SmSEPT10G in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mm NaCl, 7% glycerol, 6 mm DTT, 10% D2O, and 1 mm GDP was subjected to 31P NMR analysis either in the absence of magnesium or in the presence of different MgCl2 concentrations (1 and 20 mm of MgCl2) to evaluate the binding of the Mg2+ ion to the SmSEPT10G-GDP complex. The binding of Mg2+ ion to the complex can be identified by a change in the chemical shift of the GDP β phosphate. 31P{1H} NMR spectra were recorded in a Bruker Avance III HD-600 NMR spectrometer operating at 242.94 MHz (31P frequency). The measurements were performed at 290 K (17 °C), using 5-mm NMR tubes, 30° flip angle, 1.0 s relaxation delay, 3.0 s acquisition time, and 3000 scans. The 31P spectra were acquired using 262,144 data points and processed with an exponential line broadening function of 15 Hz. The spectra phase and baseline were corrected automatically. A 85% phosphoric acid 1-mm capillary tube was used as an external reference for 31P chemical shifts.

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Determination

The hanging drop vapor diffusion method was used to obtain crystals of SmSEPT10G. Drops of 2 μl of the purified protein in standard buffer (3.5 mg/ml protein in the presence of 2 mm GDP or GTP) were mixed with 2 μl of the reservoir solution (0.2 m sodium acetate, 25% PEG 3350) at 20 °C. After 24 h, the crystals were briefly transferred to the cryoprotective solution and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The x-ray diffraction data were collected at the Diamond Light Source using the beamlines I24 (SmSEP10-GDP) and I04-1 (SmSEP10-GTP). The data were collected up to 1.93 and 2.14 Å for the GDP and GTP complexes, respectively. These resolutions are the highest obtained for any septin reported to date. The data were indexed, integrated, and scaled using the package Xia2. The structure of the S. mansoni Septin10 GTPase domain in complex with GDP was solved by molecular replacement with the program Phaser (25), using the GTPase domain of human SEPT2 modified by the Chainsaw program (26) as the search model (Protein Data Bank entry 2QNR). The two proteins share 64% sequence identity. Two molecules related by non-crystallographic symmetry were found in the asymmetric unit consistent with the Matthews coefficient. Structure refinement was carried out using Phenix (27) and Coot for model building (28), using σa-weighted 2Fo − Fc and Fo − Fc electron density maps. The GDP ligands were automatically placed using the Find Ligand routine of Coot, and water molecules were located using a combination of COOT and Phenix. The complex with GTP was also solved employing Phaser using the coordinates of the previously refined GDP complex. The behavior of R and Rfree were used as the principal criteria for validating the refinement protocol, and the stereochemical quality of the model was evaluated with Procheck (29) and Molprobity (30). The data collection and processing parameters can be visualized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| SmSEPT10G (GDP) | SmSEPT10G (GTP) | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | C121 | C121 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) a, b, c, β | 160.90, 45.04, 95.49, 112.17 | 160.80, 47.04, 95.48, 112.61 |

| Detector | PILATUS 6M | PILATUS 2M |

| X-ray source | DLS I24 | DLS I04-1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9686 | 0.9200 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 26.17–1.93 (1.98–1.93)a | 74.22–2.14 (2.20–2.14) |

| Redundancy | 4.0 (3.6) | 4.8 (5.0) |

| Rmerge (%)a | 4.8 (63.3) | 8.8 (78.5) |

| Rpim (%)a | 2.9 (54.0) | 5.0 (43.5) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.6 (96.3) | 99.0 (99.5) |

| Total reflections | 189,605 (12,206) | 173,158 (13,112) |

| Unique reflections | 47,003 (3421) | 36,342 (2643) |

| I/σ(I) | 10.0 (2.0) | 9.9 (2.4) |

| Refinement parameters | ||

| Reflections used for refinement | 46,962 | 36,333 |

| R (%) | 18.51 | 18.68 |

| RFree (%) | 21.70 | 22.12 |

| No. of protein atoms | 3968 | 4019 |

| No. of water molecules | 129 | 193 |

| B (Å2) | ||

| Protein | 53.98 | 43.93 |

| Ligands | 39.03 | 32.37 |

| Water | 49.34 | 41.29 |

| Error estimates | ||

| Coordinate error (Å) | 0.25 | 0.26 |

| Phase error (degrees) | 28.78 | 24.99 |

| DPI Cruckshank | 0.12 | 0.16 |

| Molprobity all-atom clashscore | 2.88 | 2.35 |

| Root mean square deviation from ideal geometry | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 | 0.002 |

| Bond angles (degrees) | 1.041 | 0.592 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Most favored region (%) | 96.75 | 97.96 |

| Residues in disallowed regions (%) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Protein Data Bank code | 4KV9 | 4KVA |

a Values for the highest resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The GTPase Domain of SmSEPT10 Is Able to Bind both GTP and GDP but Does Not Display Hydrolytic Activity

Recombinant full-length SmSEPT10 and a construct named SmSEPT10G (comprising the 268 amino acids of the GTPase domain of SmSEPT10, residues 39–306) were successfully expressed in E. coli. After cell lysis and removal of insoluble material, strong protein bands of the expected molecular masses were detected in the soluble fraction for both samples on SDS-PAGE (data not shown). These fractions were submitted to nickel affinity chromatography followed by size exclusion chromatography for purification of the recombinant proteins.

GTPase activity assays were performed by incubating GTP with SmSEPT10 for different times and evaluating the GTP and GDP content of the sample by HPLC (Fig. 1). It is possible to note that even after 24 h of incubation with GTP, there is no noticeable production of GDP, indicating that the protein displays no or very low levels of catalytic activity. Such a result was not unexpected because it has been previously reported that members of the SEPT6 subgroup are catalytically less active than the remaining three subgroups (13, 31), and the closest mammalian homologue to SmSEPT10 is SEPT10 itself, which belongs to this subgroup.

FIGURE 1.

SmSEPT10 displays no detectable GTPase activity. Shown is the profile of the elution of guanine nucleotides from the DEAE-5PW anion exchange column as measured at 253 nm after incubating 15 μm SmSEPT10 and 45 μm GTP for different time intervals. AU, absorbance units.

In order to characterize the binding of GTP and GDP, ITC experiments were performed with the SmSEPT10G construct, because it displayed a greater stability at the high concentrations necessary to perform ITC measurements. The purified SmSEPT10G had no detectable nucleotide carryover as assessed by anion exchange chromatography (data not shown), enabling the direct use of the purified protein in the ITC measurements without the need to displace any bound nucleotide. The analysis of the binding isotherms obtained for SmSEPT10G titrated with GTP (Fig. 2A) and GDP (Fig. 2B) reveals that the reactions were exothermic, and the dissociation constants for both nucleotides were determined (Table 2). The affinity for both nucleotides was much lower than that determined for human SEPT2 and SEPT3, which display Kd values in the micromolar range (16, 32). The influence of MgCl2 on the binding of GTP and GDP was also evaluated. The presence of MgCl2 was essential for the interaction with GTP, and no binding was detected in the absence of the metal ion (data not shown). On the other hand, the binding of GDP was independent of the presence of MgCl2.

FIGURE 2.

SmSEPT10G is able to bind GTP and GDP. Shown are raw ITC data (top) and binding isotherms (bottom) from the guanine nucleotide binding assay utilizing the following: SmSEPT10G (24 μm) in standard buffer in the presence of 5 mm MgCl2 titrated with 2 mm GTP (A) or SmSEPT10G (15 μm) in standard buffer titrated with 3 mm GDP (B). Each titration was carried out with 45 injections of 5 μl.

TABLE 2.

Thermodynamic parameters of SmSEPT10 binding to nucleotides

| ΔH | Kd | |

|---|---|---|

| kcal/mol | m | |

| SmSEPT10 + GTP | −3.98 ± 0.09 | (1,15 ± 0,05) × 10−4 |

| SmSEPT10 + GDP | −2.89 ± 0.08 | (1,46 ± 0,05) × 10−4 |

Considering that the Mg2+ ion is not essential to the formation of the SmSEPT10G-GDP complex, we performed 31P NMR spectroscopy to infer the relevance of Mg2+ binding to this complex at physiological magnesium concentrations. Fig. 3 displays the obtained 31P NMR spectra of SmSEPT10G-GDP in the absence and presence of different Mg2+ concentrations: resonances corresponding to the α- and β-phosphates of free GDP (the sharp lines at −9.87 and −5.88 ppm) and GDP bound to the protein (broad lines at −8.97 and 2.82 ppm), respectively (Fig. 3A). The sharp lines indicate that GDP tumbles freely in solution, and the broad lines show reduced mobility of GDP molecules when bound to protein. Fig. 3, B and C, shows the spectra of free and bound GDP but in the presence of 1 mm (B) and 20 mm (C) Mg2+. Comparing the spectra using Mg2+ at saturating concentrations (Fig. 3C) and in the absence of the ion (Fig. 3A), it is possible to note a marked change in the chemical shift of the GDP β-phosphate bound to the protein. At 1 mm Mg2+, which represents the high end of physiological free Mg2+ concentrations (33), the chemical shift of the GDP β-phosphate bound to the protein is similar to that observed in the absence of Mg2+ (Fig. 3B). This suggests that within the cellular context, the SmSEPT10G-GDP complex should be predominantly in the unbound state. Consequently, during the crystallization assays, MgCl2 was added to the purified protein only when GTP was present, and the structure obtained for the GDP-bound complex did not contain Mg2+.

FIGURE 3.

SmSEPT10-GDP complex is predominantly magnesium-free at physiological concentrations. Shown are 31P{1H} NMR spectra recorded at 290 K and operating at 31P frequency of 243.94 MHz (11.4 T) of SmSEPT10G-GDP complex in the absence of Mg2+ (A) and in the presence of 1 mm (B) and 20 mm (C) of Mg2+. The chemical shift scale was referenced in 0.00 ppm from signal of 85% external phosphoric acid contained in a capillary tube, and the resonances were assigned to the α- and β-phosphate (free and bound), according to John et al. (54).

Structure Solution and Refinement

Considering that much previous structural work on human septins has also been performed on the isolated GTPase domains (14, 15, 34), the structures described here for SmSEPT10G allow for direct comparison. Despite the fact that it is expected that SmSEPT10 would be bound to GTP when present within heterofilaments (as is the case for SEPT6 within the SEPT2/6/7 complex), we have been successful in solving crystal structures for both the GTP- and GDP-bound forms. Both complexes crystallized in space group C2 with two monomers in the asymmetric unit and were successfully solved by molecular replacement. The structures have been refined to 1.93 Å (GDP) and 2.1 Å (GTP), respectively, the highest resolutions reported to date for any septin structure, yielding final R/RFree values of 18.51/21.70% for SmSEPT10G-GDP and 18.68/22.12% for SmSEPT10G-GTP. The structures reported for SmSEPT10G (residues 39–306 of the full SmSEPT10 sequence) consist of 3,965 protein atoms, 129 water molecules, and two molecules of GDP in the case of the GDP complex and 4,019 protein atoms, 193 water molecules, two molecules of GTP, and two magnesium ions in the case of the GTP complex. However, in both cases, some residues presented no interpretable electron density and are absent from the final models. In the GDP complex, these correspond to residues 39, 69–78, 103–110, and 246–248 from subunit A and residues 39, 71–78, and 103–108 from subunit B, whereas in the GTP complex they correspond to residues 39, 69–77, 107–110, and 245–248 from subunit A and 39, 70–77, and 108 from subunit B. Despite the difference in the β3 strand register that will be discussed below, the monomer structures are very similar in both complexes, showing a root mean square deviation that varies between 0.58 and 0.63 Å (upon automatically overlaying Cαs). These values compare with 0.62 Å when the dimers are simultaneously superposed, suggesting the relative orientation of the two subunits to be effectively identical in both structures, consistent with the crystals being isomorphous. When compared with other septin monomers, the mean RMS deviation is 1.4 Å.

Overall Description of the Structures

SmSEPT10G has the typical septin fold, based on that of small GTPases (Fig. 4). In addition to the central six-stranded β-sheet (β1–β6), septins possess a C-terminal extension known as the septin unique element, which corresponds to β-strands 9, 10, 7, and 8 (in that order) and α-helices 5 and 6 (13). Helix 6 possesses a characteristic α-aneurism (35, 36), which is conserved in all known structures (residues 290–294). β2 runs antiparallel to the remainder of the sheet and is poorly defined in all previously described structures. Here we observe clear density for the entire strand in both the GDP- and GTP-bound forms due to the significantly higher resolution of the present structures. The helix α5′ has been seen in two rather different orientations in previous structures, and here it is observed to be in the more common of the two, as observed in SEPT2 (13) and SEPT7 (14, 15), but different from that seen in SEPT3 (16).

FIGURE 4.

Ribbon diagram of the asymmetric unit of the SmSEPT10G-GDP complex. The nomenclature for the secondary structure elements follows that adopted by Sirajuddin et al. (12) and is shown on the right.

The septin unique element contributes to two interfaces, known as G and NC, leading to the formation of a filament within the crystal lattice. In the present structures, this filament is essentially identical in both the GDP- and GTP-bound forms and also identical to that observed previously for the only known crystal structure of a septin heterocomplex, that composed of septins 2, 6, and 7 (13). Furthermore, similar filaments are also observed when individual septin GTPase domains are crystallized separately (13–16). This is the case for SEPT3, SEPT7, and SEPT2 (when bound to GDP). The only exception to this observation described to date is that of SEPT2 bound to a GTP analog, GppNHp (12), and this will be discussed below. The filament observed in the present structures is neither foreshortened nor expanded with respect to the heterocomplex, unlike those observed for SEPT3, SEPT2, and SEPT7. In the structures of both complexes, the nucleotide is found bound to its canonical binding site at the G interface. Fig. 5 shows the specific interactions made in the B subunit of the GTP complex. The higher resolution of the present structures allows us to comment on details of the binding site that have not been described previously. The P-loop (residues 48–55) (37) provides the most important interactions stabilizing the nucleotide phosphates. In septins, the loop extends to include the side chain of Thr56, which coordinates the α-phosphate of the nucleotide in both the GDP- and GTP-bound complexes. Lys54 lies between the β- and γ-phosphates in the GTP complex whereas Thr50 interacts solely with the latter via water Wat60 (w60 in Fig. 5), itself hydrogen-bonded to the main chain amide of the invariant Gly103 from the DXXG motif (G3 motif) of the switch II region. Interestingly, the aspartic acid of this motif is in fact a glutamic acid in SmSEPT10, and this position is generally not well conserved in the SEPT6 subgroup to which SmSEPT10 belongs. Furthermore, Gly103 does not interact directly via its backbone amide with the γ-phosphate in the classical arrangement for small GTPases but does so via a water molecule (Wat60).

FIGURE 5.

LIGPLOT+ representation of contacts within the GTP binding site. Hydrogen bonds made between the GTP molecule and the B subunit are shown explicitly, and the majority are conserved in both complexes (GTP and GDP). Water molecules (which are observed interacting with both the phosphate groups and the base) are shown as light blue spheres, and the Mg2+ ion is shown as a green sphere.

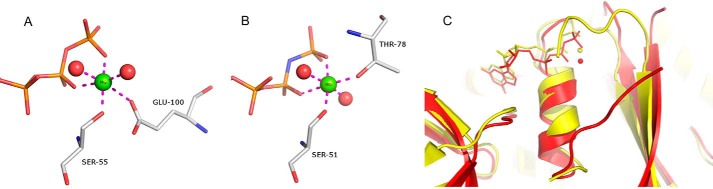

Thr50 is unique to the SEPT6 subgroup of septins, being a serine in the remaining subgroups. The Mg2+ ion, which is only present in the GTP complex, is directly bound by Ser55 from the P-loop, two oxygens from the β- and γ-phosphates, two water molecules, and Glu100 from the C-terminal end of β3, which replaces the Asp typically found in the DXXG motif. In the GDP complex, due to the lack of Mg2+, this glutamic acid is released into the switch II loop region, as described below. Similarly, the water molecule Wat60 is lost due to both the absence of the γ-phosphate and a concomitant change in conformation to Gly103 (which no longer shows significant electron density).

Interestingly, switch I does not participate in Mg2+ binding. This is different from what is observed in the SEPT2-GppNHp and SEPT3-GDP complexes in which switch I is directly involved via the side chain of Thr78 or its homologue, Thr102, respectively. The SEPT6 subgroup is unique in lacking this otherwise conserved threonine and in having a five-residue deletion prior to it. As a consequence, SmSEPT10G does not follow the otherwise universal “loaded spring” mechanism (38), which involves the participation of switch I not only in Mg2+ binding but also in anchoring the γ-phosphate directly via the threonine backbone amide (Fig. 6). Indeed, the homologue to the switch I threonine is disordered in the GTP complex, and the resulting coordination of the Mg2+ ion is significantly different from that described for other septins (Fig. 7). Not only is one of the protein ligands different (Glu for Thr), but its coordination position is also different, due to an exchange with a water molecule.

FIGURE 6.

SmSEPT10 lacks catalytic activity. Both p21 H-ras (A) and SEPT2 (B) display the classical “loaded spring” mechanism by which main chain amide groups from both switch regions (SW1 and SW2) form direct hydrogen bonds to the γ-phosphate. In the case of switch 1, this is provided by a threonine residue that is not conserved in SmSEPT10. This threonine also secures a water molecule (red sphere in A and B), which is poised for in-line attack during catalysis. In SmSEPT10 (C), no direct hydrogen bonds are formed with the γ-phosphate by residues from the switch regions. SW2 interacts via a water molecule (small red sphere in C), and SW1 is completely absent due to the lack of the threonine. As a consequence, there is no water adequately poised for catalysis. In SmSEP10, a standard 2Fo − Fc electron density map for this region is also shown.

FIGURE 7.

The Mg2+ binding site. A, Mg2+ ion coordination as observed in the SmSEPT10 complex with GTP. B, Mg2+ binding site in the GppNHp complex with SEPT2. C, superposition of the SmSEPT10 (red) and SEPT2 (yellow) complexes, showing that the switch I region in the former does not participate in Mg2+ coordination. This leads to a significant difference from the metal coordination sphere, as can be seen in A and B.

Lack of Catalytic Activity

The minimal hydrolytic activity of the SEPT6 subgroup is well known and has been further demonstrated here for SmSEPT10. In addressing the structural basis for this lack of activity, it has been speculated (12), based on the structure of SEPT2, that Thr78 from switch I may be essential for catalysis. Here we provide some direct support for this proposal. This threonine normally performs three important functions. It directly coordinates the Mg2+ ion, it donates a hydrogen bond to the γ-phosphate, and it secures a water molecule via a main chain carbonyl, ready for in-line nucleophilic attack during catalysis. The absence of this threonine in SmSEPT10 means that this water is not observed in the structure we report here, making catalysis impossible. Either of the competing proposals for the catalytic mechanism, be it associative (39) or dissociative (40), requires the presence of such a water molecule. Therefore, our structure strongly supports the notion that it is the differences in the switch I region (and particularly the absence of the threonine) that are responsible for the lack of activity observed for this subgroup (Fig. 6). However, it is important to add that the structure reported here does not represent the transition state for catalysis, and therefore a degree of caution should be applied when trying to provide a mechanistic explanation for the experimentally observed lack of catalytic activity.

Water Structure and the G Interface

Several water molecules appear to be important for binding both GDP and GTP. Two of these interact directly with the N7 and N3 positions of the base, and a further one interacts with the O3′ of the ribose. The water that is anchored to N7 also interacts with Gly53 of the P-loop and with a second water that connects to Ile52 and Lys184 (of the G4 GTPase signature sequence, AKXD). The guanine base lies sandwiched between this lysine and Arg253. The latter is a septin-specific residue (20) coming from β7 and shows some degree of disorder in the electron density maps. It forms a salt bridge with Glu192 from the neighboring subunit (also septin-specific), suggesting this interaction to be an important component of the G interface. Tyr255 from the loop between β7 and β8 slots into the G interface interacting with Arg253 in a manner identical to that seen previously for other septin structures. This residue has recently been shown to be essential for the formation of an intact G interface (16). Finally, Gly238 donates a hydrogen bond to O6, and Asp186 (from the AKXD G4 signature sequence) secures N1 and N2 of the guanine base as normally observed in small GTPases.

Besides the salt bridge with Arg253 described above, Glu192 is also normally observed interacting with the ribose base either directly or via a water molecule. Furthermore, N2 and N3 of the base also form cross-interface hydrogen bonds with the main chain oxygen of Thr187, the former directly and the latter via a water molecule. His159 from the neighboring subunit may interact with the nucleotide phosphates, but the density is poorly defined in both subunits of both of the structures reported here, indicating, at best, a weak interaction. In the only other structure of a septin-GTP (or GTP analog) complex, that of SEPT2 with GppNHp (3FTQ), this histidine (His158 in SEPT2) is reported to form a salt bridge with Asp106 (Asp107 in SEPT2, part of the switch II region). This is not observed in either of our structures or in that of SEPT3 and may be SEPT2-specific. Indeed, different from the SEPT2-GppNHp complex, the switch II region is not completely structured in either of the SmSEPT10 structures described here. When ordered, it also takes a course different from that observed in either SEPT3 (16) or SEPT7 (14, 15). However, it should be pointed out that G interfaces observed in homofilaments encountered in crystal structures are likely to be promiscuous rather than physiological. Nevertheless, the significantly higher resolution of the structures described here makes them useful models for better understanding such interfaces.

Switch Regions

There are few differences between the GDP- and GTP-bound complexes in the switch I region, which is largely disordered in both cases. This might be unexpected were it not for the fact that the SEPT6 group is catalytically less active, as mentioned above. The only significant difference is that Lys81 in the GDP complex interacts with Ser55, which is a ligand to the Mg2+ in the GTP complex. In the case of switch II, neither structure is completely ordered (in the GDP complex, density is lacking for residues 103–110 (subunit A) and 103–108 (subunit B), whereas in the case of the GTP complex, this applies to residues 107–110 (subunit A) and residue 108 alone (subunit B). Furthermore, there is no interaction between neighboring switches II across the G interface as seen in SEPT7 and SEPT3. As mentioned above, in the GTP complex, switch II is unstructured at least to some extent in both monomers and is two residues shorter due to strand slippage (described below). Consequently, the ordered parts of switch II and its associated water structure show significantly different conformations in the two complexes.

Strand Register

For the first time, we are able to describe with confidence the register of residues within certain parts of the septin structure that until now have been poorly defined due to the limits of resolution. This applies particularly to β2, which lies at the edge of the main β-sheet and is the only strand to run antiparallel to the remainder. The register of this strand has been interpreted differently in the several septin crystal structures reported to date. Although this could potentially be explained by alternative crystal packing, it seems far more likely to be due to the ambiguities inherent in the interpretation of poorly defined electron density.

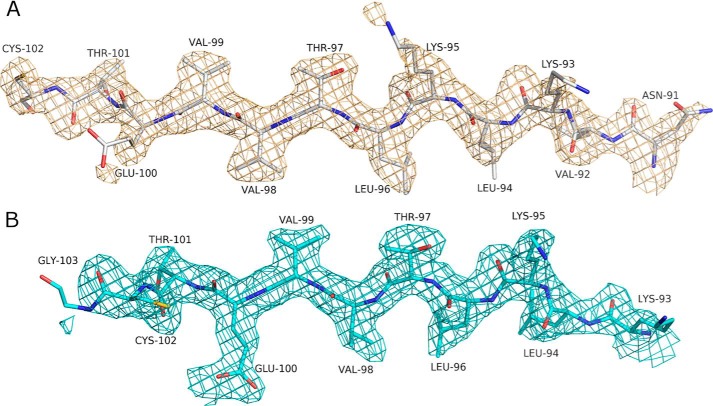

The most striking difference between the GDP- and GTP-bound forms of SmSEPT10 affects strand β3, which lies between β2 on one side and the parallel strand, β1, on the other. Upon comparing the two complexes, it becomes clear that the β3 strand is shifted with respect to both of its neighbors by exactly two residues (∼6 Å) (Fig. 8). The consequence is to increase the size of the β2/β3 hairpin loop in the GTP complex and simultaneously reduce that of the loop following β3, which leads into switch II. A total of 18 hydrogen bonds on both sides of β3 in the GTP complex are replaced by 19 with a shifted register in the GDP complex (Fig. 9). As a consequence, β2 and β3 are extended toward the NC interface in the presence of GTP. On the other hand, a rearrangement of switch II at the G interface means that β3 forms additional hydrogen bonds with β1 in the GDP complex. Despite not having been commented on by the authors, a similar phenomenon appears to occur in human SEPT2 (12). Upon comparing the crystal structures of the GDP-bound form (2QA5 or 2QNR) with that with the GTP analog GppNHp (3FTQ), the β3 strand is also observed to be shifted by two residues. This shift is clearly evident with respect to β1, but the poor definition of the density of the β2 strand due to limited resolution made it impossible to exactly define the correct relative register. This is emphasized by the different interpretations present in Protein Data Bank files 2QA5 and 2QNR. Here, we are able to unambiguously affirm that it is the β3 strand that alone is shifted with respect to both β1 and β2 and therefore with respect to the rest of the sheet.

FIGURE 8.

Electron density of the β3 strand. Fo − Fc electron density omit maps (contoured at 2.5σ) for the β3 strand in the GDP complex (A) and the GTP complex (B). In the latter, all residues are shifted by two to the right bring Glu100 into a position for coordinating the Mg2+ ion. Slippage appears to be facilitated by the existence of a Lys-Leu-Lys-Leu repeat and the presence of many small β-branched amino acids.

FIGURE 9.

β-strand slippage. Shown are HERA hydrogen bonding diagrams for part of the β-sheet composed of strands 1–3. The situation in the GDP complex (A) is different to that of the GTP complex (B), but the total number of main chain hydrogen bonds is almost identical in both cases. In C, the result of slippage is seen to be the communication between the G interface to the left and the NC interface to the right. Part of a filament of the GTP complex is shown (dark blue) with a single subunit from the GDP complex superimposed at the center (light blue). The sliding (β3) strand is shown in yellow (GTP complex) and orange (GDP complex).

This two-residue slippage appears to be facilitated by a Lys-Leu-Lys-Leu repeat within the β3 strand sequence (Fig. 8). Similar observations have been made for other systems that use strand slippage as an activation mechanism, as is the case for factor VIIa and Arf (41, 42). Furthermore, similar phenomena have also been reported in T-cell receptor α subunits (43), amyloidogenic transthyretin mutants (44), and the β-amyloid peptide at different pH values (45).

In SmSEPT10G, the register shift results in Lys93 and Leu94 in the GDP-bound form taking up the positions occupied by Lys95 and Leu96 in the GTP complex. As such, either Lys95 or Lys93 aligns with Asp86 of the neighboring β2 strand. Furthermore, the presence of a Phe-X-Phe sequence (residues 40–42) at the beginning of the β1 strand appears to be related to the same phenomenon because it allows a Leu96-Phe42 hydrophobic contact in the GTP complex to be replaced by an analogous Leu94-Phe42 contact for the alternative register of the β-strand. This can be more clearly appreciated from the hydrogen bonding map of the two states shown in Fig. 9.

One critical structural feature related to strand slippage appears to be the presence of the magnesium ion in the GTP complex. The metal is directly coordinated by Glu100 from the sliding β3 strand. In the GDP complex, which does not contain Mg2+, Glu100 is shifted into the loop following β3, which leads into the switch II region. Thus, metal ion coordination must certainly be one of the factors that control the register of the β-sheet. This is consistent with the fact that the recently solved structure of human SEPT3 (16) in complex with GDP/Mg2+ presents the β3 strand shifted in a way reminiscent of the GTP complex described here. In this case, Glu100 is replaced by Asp125 (3SOP), which coordinates the magnesium ion indirectly via a water molecule. It is also consistent with the structure of SEPT6 within the heterofilament formed by human septins 2, 6, and 7 (13). In this complex, SEPT6 is unique in being bound to GTP rather than GDP, and despite the low resolution of the structure, it was interpreted to have a strand register between β1 and β3 identical to that observed here for the SmSEPT10G-GTP complex (Fig. 10).

FIGURE 10.

The consequences of strand slippage. Part of the heterocomplex of SEPT2-SEPT6-SEPT7 is shown (red, dark blue, and yellow, respectively) with the SmSEPT10G structure, as observed when complexed to GTP (light blue), superimposed on SEPT6. The consequence of strand slippage is the extension of the β-hairpin connecting β2 to β3 and thereby the coverage of the N-terminal helix α0. This region corresponds to the polybasic region known to be important for membrane association in mammalian septins. The implication is that strand slippage may affect membrane binding in a nucleotide-dependent fashion.

A second consequence of the slippage is the extension of strands β2 and β3 toward the NC interface in the GTP complex. This extension has been previously noted (although not the slippage) in the case of human SEPT2 (12) and used to explain why the structure in the presence of the GTP analog does not form filaments within the crystal. This was attributed to a ∼20° tilt of the β2/β3 region of the sheet, which would lead to a clash with the α0 helix of the NC interface, thus preventing filament formation. However, as shown in Fig. 9C, the extension to the sheet strands in SmSEP10G (as well as SEPT3 and SEPT6 from the heterofilament) does not lead to sheet distortion and is not incompatible with filament formation, so much so that such filaments are indeed observed in both crystal structures reported here. Indeed, this is compatible with data on yeast septins suggesting that filament formation is independent of the nature of the nucleotide (46).

It seems more likely that the observed sheet distortion in SEPT2 is in fact the result of crystal packing because this region forms extensive β-sheet hydrogen bonds with the equivalent region from a 2-fold related molecule. It would seem that rather than sheet distortion preventing filament formation, it is non-filamentous crystal packing that leads to sheet distortion. Overall, there seems to be no incompatibility between strand slippage/sheet extension and filament formation.

The consequence of strand slippage is to generate a front-back communication mechanism between the G and NC interfaces. Strand slippage as a protein activation mechanism is not entirely unprecedented but is rare. The example most relevant to the current discussion was seen in Arf proteins. Like septins, Arf proteins are small GTPases involved in a series of membrane-remodeling events associated with intracellular vesicle transport (47, 48). Membrane association depends on the exposure of an N-terminal myristoyl group that is dependent on the presence of GTP rather than GDP. Unlike septins, however, Arf proteins do not form filaments but rather are active as monomers. The best known examples are Arf1 and Arf6, which are specifically involved in the assembly of coat complexes at the Golgi and plasma membrane, respectively. Their activity is controlled by GTP hydrolysis, which leads to β3 strand slippage analogous to that described here. However, in this case, the β2 strand accompanies β3, and both slide as a rigid body with respect to β1 (42, 49–51) (Fig. 11).

FIGURE 11.

Comparison between SmSEPT10 and Arf6. Septins may operate via a mechanism analogous to that seen in Arf proteins, which use β-strand slippage as a means to dislodge the N-terminal helix and so influence membrane association. A, superposition of Arf6 in its GDP complex (blue) and GTPγS complex (yellow), showing the slippage of both strands β2 and β3 with respect to β1, in the direction of the short N-terminal helix. B, in SmSEPT10, a similar color scheme is adopted, but in this case, β3 slips with respect to both β1 and β2.

What is most intriguing is that, like septins, Arf proteins have an N-terminal α-helix that precedes the β1 strand. In septins, this helix corresponds to the polybasic region, known to be involved in membrane association (11). The orientation of this helix is radically different in the Arf complexes with GDP and GTP, being folded back on the structure in the former and exposed in the latter. This conformational change controls membrane association and involves both the N-myristoyl group and hydrophobic and basic residues from the helix (52). Based on the crystal structure of the SEPT2/6/7 heterocomplex, where helix α0 is present (albeit poorly defined), it is possible to assert that the strand slippage in the GTP complex of SmSEPT10G would cause steric hindrance and force the helix into a different conformation, in a fashion analogous to that seen in Arf. The similarity in both structure and function of these two families is highly suggestive of a similar mechanism of action. We therefore speculate that strand slippage is an integral part of the mechanism by which septins associate and disassociate from membranes. This implies that the importance of GTP binding and hydrolysis is related to membrane association rather than filament formation. This is consistent with results described on SEPT4 by Zhang et al. (11), who demonstrated that the GDP complex had greater affinity for membranes containing phosphotidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate than the corresponding GTP complex.

Conclusions

In mammalian septin complexes, the SEPT6 subgroup members occupy the middle position of the heterofilament, interacting with a SEPT2 subgroup member via a G interface and with SEPT7 via an NC interface. Assuming a similar arrangement for heterofilaments in schistosomes leads to the conclusion that both of the homotypic interfaces observed in our crystal structures should be considered promiscuous because they are not anticipated to exist physiologically. With the current report, there are now examples of crystal structures for all four individual subgroups of septins, revealing that the phenomenon of promiscuity in interfacial interactions is completely generic. Discovering the structural determinants responsible for the correct assembly of a heterofilament therefore remains an important challenge in current septin research (53).

SmSEPT10 belongs to the SEPT6 subgroup, whose members are expected to be bound to GTP rather than GDP when incorporated into heterofilaments, due to their extremely low catalytic activity. The manner by which GTP and its associated Mg2+ are bound to SmSEPT10G therefore represents the best description presented to date for the physiological state of this subgroup. On the other hand, the relevance of the GDP-bound form of SmSEPT10 is less certain. It should be considered a good high resolution model for the remaining septin subgroups. Despite this disclaimer, it seems highly likely that the strand slippage observed in SmSEPT10G and described in detail here is indeed an important mechanistic aspect of septins in general because, although not described by the authors, it has also been observed in the case of the hydrolytically active SEPT2 (12). The mechanism is analogous to that previously described in another small GTPase, Arf, but is unique in the fact that such strand slippage promotes the breakdown of interactions from the two sides of the slipping strand.

The structures we describe here emphasize the uniqueness of the SEPT6 subgroup. Among other features, SmSEPT10 shows an unusual Mg2+ coordination; a disordered switch I region even in the presence of GTP; an unusual primary structure within switch I itself (involving the lack of a normally conserved threonine that coordinates the magnesium); incomplete closure of the switch II region, which fails to interact directly with the γ-phosphate and remains largely disordered even in the GTP complex; alterations to the P-loop (where Thr50, at the G interface, substitutes a serine conserved in all other subgroups); and the absence of a polybasic region prior to the GTP-binding domain. These unique features of the SEPT6 subgroup are probably interrelated, implying a specific role in filament assembly, function, or dynamics. The difference between the GDP-bound and GTP-bound forms of SmSEPT10G and, more specifically, the shift to the β3 strand is likely to be a more general phenomenon that applies to several or all of the septin subgroups. It seems likely that it is an important molecular switch controlling membrane association and dissociation and thereby membrane-remodeling events.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Julio C. P. Damalio, Dr. Joci N. A. Macedo, Andressa A. Pinto, and Derminda I. de Moraes for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) Grant 550514/2011-2 and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) Grant 2008/57910-0 (to the Instituto Nacional de Ciencia e Tecnologia-Instituto Nacional de Biotecnologia Estrutural e Quimica Mecicinal em Doenças Infecciosas (INCT-INBEQMeDI).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 4KV9 and 4KVA) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- Arf

- ADP-ribosylation factor

- GTPγS

- guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mostowy S., Cossart P. (2012) Septins. The fourth component of the cytoskeleton. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 183–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nishihama R., Onishi M., Pringle J. R. (2011) New insights into the phylogenetic distribution and evolutionary origins of the septins. Biol. Chem. 392, 681–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Versele M., Thorner J. (2005) Some assembly required. Yeast septins provide the instruction manual. Trends Cell Biol. 15, 414–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Russell S. E., Hall P. A. (2011) Septin genomics. A road less travelled. Biol. Chem. 392, 763–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cao L., Yu W., Wu Y., Yu L. (2009) The evolution, complex structures and function of septin proteins. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 66, 3309–3323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kinoshita M., Field C. M., Coughlin M. L., Straight A. F., Mitchison T. J. (2002) Self and actin template assembly of mammalian septins. Dev. Cell 3, 791–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Estey M. P., Kim M. S., Trimble W. S. (2011) Septins. Curr. Biol. 21, R384–R387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weirich C. S., Erzberger J. P., Barral Y. (2008) The septin family of GTPases. Architecture and dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 478–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hall P. A., Russel S. E. H., Pringle J. R. (eds) (2008) The Septins, pp. 35–45, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Chichester, UK [Google Scholar]

- 10. Casamayor A., Snyder M. (2003) Molecular dissection of a yeast septin. Distinct domains are required for septin interaction, localization, and function. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 2762–2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang J., Kong C., Xie H., McPherson P. S., Grinstein S., Trimble W. S. (1999) Phosphatidyl inositol polyphosphate binding to the mammalian septin H5 is modulated by GTP. Curr. Biol. 9, 1458–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sirajuddin M., Farkasovsky M., Zent E., Wittinghofer A. (2009) GTP-induced conformational changes in septins and implications for function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16592–16597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sirajuddin M., Farkasovsky M., Hauer F., Kühlmann D., Macara I. G., Weyand M., Stark H., Wittinghofer A. (2007) Structural insight into filament formation by mammalian septins. Nature 449, 311–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zent E., Vetter I., Wittinghofer A. (2011) Structural and biochemical properties of Sept7, a unique septin required for filament formation. Biol. Chem. 392, 791–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Serrão V. H., Alessandro F., Caldas V. E., Marçal R. L., D'Muniz Pereira H. D., Thiemann O. H., Garratt R. C. (2011) Promiscuous interactions of human septins. The GTP binding domain of SEPT7 forms filaments within the crystal. FEBS Lett. 585, 3868–3873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Macedo J. N., Valadares N. F., Marques I. A., Ferreira F. M., Damalio J. C., Pereira H. M., Garratt R. C., Araujo A. P. (2013) The structure and properties of septin 3. A possible missing link in septin filament formation. Biochem. J. 450, 95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nahum L. A., Mourão M. M., Oliveira G. (2012) New frontiers in Schistosoma genomics and transcriptomics. J. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 849132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berriman M., Haas B. J., LoVerde P. T., Wilson R. A., Dillon G. P., Cerqueira G. C., Mashiyama S. T., Al-Lazikani B., Andrade L. F., Ashton P. D., Aslett M. A., Bartholomeu D. C., Blandin G., Caffrey C. R., Coghlan A., Coulson R., Day T. A., Delcher A., DeMarco R., Djikeng A., Eyre T., Gamble J. A., Ghedin E., Gu Y., Hertz-Fowler C., Hirai H., Hirai Y., Houston R., Ivens A., Johnston D. A., Lacerda D., Macedo C. D., McVeigh P., Ning Z., Oliveira G., Overington J. P., Parkhill J., Pertea M., Pierce R. J., Protasio A. V., Quail M. A., Rajandream M.-A., Rogers J., Sajid M., Salzberg S. L., Stanke M., Tivey A. R., White O., Williams D. L., Wortman J., Wu W., Zamanian M., Zerlotini A., Fraser-Liggett C. M., Barrell B. G., El-Sayed N. M. (2009) The genome of the blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni. Nature 460, 352–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zeraik A. E., Rinaldi G., Mann V. H., Popratiloff A., Araujo A. P., Demarco R., Brindley P. J. (2013) Septins of platyhelminths. Identification, phylogeny, expression and localization among developmental stages of Schistosoma mansoni. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7, e2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pan F., Malmberg R. L., Momany M. (2007) Analysis of septins across kingdoms reveals orthology and new motifs. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kinoshita M. (2003) Assembly of mammalian septins. J. Biochem. 134, 491–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martínez C., Sanjuan M. A., Dent J. A., Karlsson L., Ware J. (2004) Human septin-septin interactions as a prerequisite for targeting septin complexes in the cytosol. Biochem. J. 382, 783–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Seckler R., Wu G.-M., Timasheff S. N. (1990) Interactions of tubulin with guanylyl-(P-y-methylene)diphosphonate. Formation and assembly of a stoichiometric complex. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 7655–7661 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tellinghuisen J. (2008) Isothermal titration calorimetry at very low c. Anal. Biochem. 373, 395–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McCoy A. J. (2007) Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 63, 32–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stein N. (2008) CHAINSAW. A program for mutating pdb files used as templates in molecular replacement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 41, 641–643 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Terwilliger T. C. (2002) PHENIX. Building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot. Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lazarowski E. R., Homolya L., Boucher R. C., Harden T. K. (1997) Identification of an ecto-nucleoside diphosphokinase and its contribution to interconversion of P2 receptor agonists. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 20402–20407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen V. B., Arendall W. B., 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2010) MolProbity. All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Field C. M., al-Awar O., Rosenblatt J., Wong M. L., Alberts B., Mitchison T. J. (1996) A purified Drosophila septin complex forms filaments and exhibits GTPase activity. J. Cell Biol. 133, 605–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huang Y.-W., Surka M. C., Reynaud D., Pace-Asciak C., Trimble W. S. (2006) GTP binding and hydrolysis kinetics of human septin 2. FEBS J. 273, 3248–3260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grubbs R. D. (2002) Intracellular magnesium and magnesium buffering. BioMetals 15, 251–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Garcia W., Rodrigues N. C., Neto M., Araújo A. P., Polikarpov I., Tanaka M., Tanaka T., Garratt R. C. (2008) The stability and aggregation properties of the GTPase domain from human SEPT4. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1784, 1720–1727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heinz D. W., Baase W. A., Dahlquist F. W., Matthews B. W. (1993) How amino-acid insertions are allowed in an α-helix of T4 lysozyme. Nature 361, 561–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Keefe L. J., Sondek J., Shortle D., Lattman E. E. (1993) The α-aneurism. A structural motif revealed in an insertion mutant of staphylococcal nuclease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 3275–3279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Walker J. E., Saraste M., Runswick M. J., Gay N. J. (1982) Distantly related sequences in the α- and β-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1, 945–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vetter I. R., Wittinghofer A. (2001) The guanine nucleotide-binding switch in three dimensions. Science 294, 1299–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pai E. F., Krengel U., Petsko G. A., Goody R. S., Kabsch W., Wittinghofer A. (1990) Refined crystal structure of the triphosphate conformation of H-ras p21 at 1.35 Å resolution. Implications for the mechanism of GTP hydrolysis. EMBO J. 9, 2351–2359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maegley K. A., Admiraal S. J., Herschlag D. (1996) Ras-catalyzed hydrolysis of GTP. A new perspective from model studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 8160–8166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Eigenbrot C., Kirchhofer D., Dennis M. S., Santell L., Lazarus R. A., Stamos J., Ultsch M. H. (2001) The factor VII zymogen structure reveals reregistration of β-strands during activation. Structure 9, 627–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Goldberg J. (1998) Structural basis for activation of ARF GTPase. Mechanisms of guanine nucleotide exchange and GTP-myristoyl switching. Cell 95, 237–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van Boxel G. I., Holmes S., Fugger L., Jones E. Y. (2010) An alternative conformation of the T-cell receptor α constant region. J. Mol. Biol. 400, 828–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Eneqvist T., Andersson K., Olofsson A., Lundgren E., Sauer-Eriksson A. E. (2000) The β-slip. A novel concept in transthyretin amyloidosis. Mol. Cell 6, 1207–1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Petkova A. T., Buntkowsky G., Dyda F., Leapman R. D., Yau W. M., Tycko R. (2004) Solid state NMR reveals a pH-dependent antiparallel β-sheet registry in fibrils formed by a β-amyloid peptide. J. Mol. Biol. 335, 247–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Farkasovsky M., Herter P., Voss B., Wittinghofer A. (2005) Nucleotide binding and filament assembly of recombinant yeast septin complexes. Biol. Chem. 386, 643–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. D'Souza-Schorey C., Chavrier P. (2006) ARF proteins. Roles in membrane traffic and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 347–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gillingham A. K., Munro S. (2007) The small G proteins of the Arf family and their regulators. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 579–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Amor J. C., Harrison D. H., Kahn R. A., Ringe D. (1994) Structure of the human ADP-ribosylation factor 1 complexed with GDP. Nature 372, 704–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Greasley S. E., Jhoti H., Teahan C., Solari R., Fensome A., Thomas G. M., Cockcroft S., Bax B. (1995) The structure of rat ADP-ribosylation factor-1 (ARF-1) complexed to GDP determined from two different crystal forms. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2, 797–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pasqualato S., Renault L., Cherfils J. (2002) Arf, Arl, Arp and Sar proteins. A family of GTP-binding proteins with a structural device for front-back communication. EMBO Rep. 3, 1035–1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Antonny B., Beraud-Dufour S., Chardin P., Chabre M. (1997) N-terminal hydrophobic residues of the G-protein ADP-ribosylation factor-1 insert into membrane phospholipids upon GDP to GTP exchange. Biochemistry 36, 4675–4684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Almeida Marques I., Valadares N. F., Garcia W., Damalio J. C., Macedo J. N., Araújo A. P., Botello C. A., Andreu J. M., Garratt R. C. (2012) Septin C-terminal domain interactions. Implications for filament stability and assembly. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 62, 317–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. John J., Rensland H., Schlichting I., Vetter I., Borasio G. D., Goody R. S., Wittinghofer A. (1993) Kinetic and structural analysis of the Mg2+-binding site of the guanine nucleotide-binding protein p21H-ras. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 923–929 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]