Background: PKG-1α nitration plays an important role in the development of pulmonary hypertension.

Results: We identified Tyr247 as the key residue susceptible to nitration and inhibition of PKG-1α.

Conclusion: Nitration attenuates PKG activity by reducing its affinity for cGMP.

Significance: Preventing the nitration of PKG-1α could prevent the phenotypic remodeling in the blood vessels during the development of a number of cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: Cyclic GMP (cGMP), Enzyme Catalysis, Mass Spectrometry (MS), Molecular Modeling, Protein Kinase G (PKG), Peroxynitrite

Abstract

The cGMP-dependent protein kinase G-1α (PKG-1α) is a downstream mediator of nitric oxide and natriuretic peptide signaling. Alterations in this pathway play a key role in the pathogenesis and progression of vascular diseases associated with increased vascular tone and thickness, such as pulmonary hypertension. Previous studies have shown that tyrosine nitration attenuates PKG-1α activity. However, little is known about the mechanisms involved in this event. Utilizing mass spectrometry, we found that PKG-1α is susceptible to nitration at tyrosine 247 and 425. Tyrosine to phenylalanine mutants, Y247F- and Y425F-PKG-1α, were both less susceptible to nitration than WT PKG-1α, but only Y247F-PKG-1α exhibited preserved activity, suggesting that the nitration of Tyr247 is critical in attenuating PKG-1α activity. The overexpression of WT- or Y247F-PKG-1α decreased the proliferation of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (SMC), increased the expression of SMC contractile markers, and decreased the expression of proliferative markers. Nitrosative stress induced a switch from a contractile to a synthetic phenotype in cells expressing WT- but not Y247F-PKG-1α. An antibody generated against 3-NT-Y247 identified increased levels of nitrated PKG-1α in humans with pulmonary hypertension. Finally, to gain a more mechanistic understanding of how nitration attenuates PKG activity, we developed a homology model of PKG-1α. This model predicted that the nitration of Tyr247 would decrease the affinity of PKG-1α for cGMP, which we confirmed using a [3H]cGMP binding assay. Our study shows that the nitration of Tyr247 and the attenuation of cGMP binding is an important mechanism regulating in PKG-1α activity and SMC proliferation/differentiation.

Introduction

Previous in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that the nitration of cGMP-dependent protein kinase G-1α (PKG-1α)4 is a key post-translational event responsible for the impaired PKG activity in the lungs of acute and chronic pulmonary hypertensive lambs (1), mice with hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension (2), and humans with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (3). However, the tyrosine residues susceptible to this nitration event and the mechanism(s) by which nitration inhibit PKG-1α activity are unclear and were the focus of this study.

PKG is a serine/threonine-specific protein kinase that is activated upon the intracellular generation of 3′,5′-cGMP by two main types of guanylyl cyclases: soluble and membrane-associated (4). Soluble guanylyl cyclase acts downstream of NO, whereas the membrane-associated guanylyl cyclase is activated through the extracellular binding of natriuretic peptides. The mammalian genome encodes a type 1 PKG (5) and a type 2 PKG (6, 7). Both types 1 and 2 PKG are homodimeric proteins containing two identical polypeptide chains of ∼76 and 85 kDa, respectively. Alternative mRNA splicing of PKG-1 produces a type 1α PKG (75 kDa) and a type 1β PKG (78 kDa), which only share 36% identity in their first 70–100 amino-terminal residues (8, 9). PKG-1 has been detected at high concentrations in all types of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) (5). PKG-2 has been detected in renal, adrenal, intestinal, pancreatic, and brain cells but not in cardiac and vascular cells.

The primary sequence of PKG-1α is divided into two separate domains: a regulatory domain (aa 1–343) containing an amino-terminal region (aa 1–110) and two cGMP-binding sites A (aa 111–227) and B (aa 228–343) and a catalytic domain (aa 344–671) containing an ATP-binding site (aa 344–474) and the substrate-binding site (aa 475–671) (10). The amino-terminal region of the regulatory domain of PKG-1α contains a dimerization site, an autoinhibitory motif, and several autophosphorylation sites. The leucine zipper motif in the dimerization domain (aa 1–39) ensures substrate specificity of PKG-1α (11). The autoinhibitory region of PKG-1α (aa 58–72) binds to the catalytic domain and maintains the enzyme in an inhibited state. This autoinhibition can be relieved by both cGMP binding and autophosphorylation, which cause a conformational change (12, 13) and disrupt the autoinhibitory interaction of the regulatory and catalytic domains. Cyclic GMP increases both the heterophosphorylation and the autophosphorylation activity of PKG (14). The autophosphorylation of PKG-1α increases kinase activity but decreases its cGMP-binding affinity (15).

A hinge region connects the amino-terminal dimerization site with the two tandem cGMP-binding sites A and B. These sites preferentially bind cGMP over cAMP with more than a 100-fold selectivity. The two cGMP-binding sites of PKG have different binding characteristics (16); the amino-terminal high affinity site A and the succeeding low affinity site B display slow and fast cGMP exchange characteristics, respectively (15, 17). The binding of cGMP to these sites activates the enzyme. The occupation of site B decreases the dissociation of cGMP from site A, and therefore, site A shows positive cooperativity (15). A maximally active enzyme is obtained when all four cGMP-binding sites of the dimeric kinase are occupied. In this study, we found that the nitration of PKG-1α at the tyrosine residue 247 prevents the binding of cGMP to the cGMP-binding site B and attenuates the catalytic activity of the enzyme.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Polyclonal anti-PKG-1α (goat), anti-Calponin-1 (rabbit), and monoclonal anti-vimentin (clone 2Q1035) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); monoclonal anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (clone CC22.8C7.3) was from EMD Biosciences, Inc. (San Diego, CA); monoclonal anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (clone PC10) and polyclonal anti-SM22-α (goat) antibodies were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA); monoclonal anti-β-actin (clone AC-15) and monoclonal anti-myosin heavy chain (MYH) (clone hSM-V) antibodies were from Sigma; 3-morpholinosydnonimine N-ethylcarbamide (SIN-1) was from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI); bovine PKG full-length recombinant protein (α1 isozyme) and a nonradioisotopic kit for measuring PKG activity were from Cyclex Co., Ltd. (Nagano, Japan); AlamarBlue was from AbD Serotec (Raleigh, NC); [3HcGMP] was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences; and YASARA software was from YASARA Biosciences GmbH (Vienna, Austria).

Generation of a Nitration-specific PKG-1α Polyclonal Antibody

The 3-NT Tyr247 PKG-1α specific antibody was raised against a synthetic peptide antigen ENGE(Y-NO2)IIRQGARGDC, where Y-NO2 represent 3-nitrotyrosine. The peptide was used to immunize rabbits. Tyrosine nitration-reactive rabbit antiserum was first purified by affinity chromatography. Further purification was carried out using immunodepletion by non-nitrated peptide ENGEYIIRQGARGDC resin chromatography, after which the resulting eluate was tested for antibody specificity by immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry with fluorescent staining.

Lamb Model of Pulmonary Hypertension

The surgical preparation to introduce fetal aorta-pulmonary shunt was carried out as previously described (18). All protocols and procedures were approved by the Committee on Animal Research at the University of California, San Francisco and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Georgia Regents University.

Human Specimens

We selected four bilateral lung explants from human patients who underwent lung transplantation because of Eisenmenger syndrome (“associated pulmonary arterial hypertension”, NYHA IV). All lung specimens showed prominent plexiform vasculopathy (age at transplantation, 36.5 ± 11.04 years; female:male ratio, 4:1). All the specimens were inflated with formalin via the main bronchi and were formalin-fixed overnight before being extensively sampled and paraffin-embedded. Subsequently, they were histologically evaluated, graded according to the Heath-Edwards classification (all grade 5), and correlated with clinical data to confirm the (histopathologic) diagnosis. The formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples were retrieved from the archives of the Institute of Pathology of Hannover Medical School and were handled anonymously, following the requirements of the local ethics committee (19). The controls were five downsized specimens of lung allografts without delimitable pathologic changes, which were sampled immediately prior to transplantation (one male and four female donors).

Cell Culture

Primary cultures of pulmonary artery SMC (PASMC) from 4-week-old lambs were isolated by the explant technique, as we have previously described (20). The identity of PASMC was confirmed by immunostaining (>99% positive) with SMC actin, caldesmon, and calponin. All culture for subsequent experiments was maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% antibiotics, and antimycotics at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and 95% air. All experiments were conducted between passages 5 and 15. HEK-293T cells were a kind gift from Dr. John. D. Catravas. Cells were transiently transfected with either the WT-PKG-1α or the Y247F-PKG-1α cDNA using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were prepared as previously described (21, 22). Similarly, peripheral lung tissue from the control lambs and the lambs with pulmonary hypertension secondary to increased pulmonary blood flow (shunt) was prepared as described earlier (1). Cell extracts (25 μg), lung tissue, or recombinant PKG-1α protein (1) were resolved using 4–20% Tris-SDS-Hepes PAGE, electrophoretically transferred to Immuno-BlotTM PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad), and then blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline. The membranes were probed with antibodies against PKG-1α (1:500 dilution), anti-3-NT Y247-PKG-1α (1:500), calponin-1 (1:500 dilution), vimentin (1:500 dilution), or MYH (1:500 dilution). Reactive bands were visualized using chemiluminescence (Pierce) on a Kodak 440CF image station. The band intensity was quantified using Kodak one-dimensional image processing software. Loading was normalized by reprobing with anti β-actin (1:2000).

Immunoprecipitation of Nitrated PKG-1α

This was carried out as recently described (1). Briefly, after immunoprecipitation of 1000 μg of total protein with 4 μg of an antibody against PKG-1α, the samples were resolved using 4–20% Tris-SDS-Hepes PAGE. The membrane was then probed for 3-nitrotyrosine (1:100 dilution), as described above. The immunoprecipitation efficiency was normalized by reprobing for PKG-1α (1:500).

Measurement of PKG Catalytic Activity

Total PKG activity (pmol/min/μg protein) was determined using a nonradioactive immunoassay in cell lysates, according to the manufacturer's directions as recently described (1). Briefly, protein samples were diluted in kinase reaction buffer containing Mg2+ and ATP (125 μm) in the presence or absence of cGMP (10 μm) and incubated in a 96-well plate precoated with a PKG substrate containing threonine residues known to be phosphorylated by PKG. After incubation for 30 min at 30 °C to allow the phosphorylation of the bound substrate, an HRP -conjugated anti-phosphothreonine specific antibody was added to convert a chromogenic substrate to a colorimetric substrate that was then read spectrophotometrically at 450 nm. The change in absorbance reflects the relative activity of PKG in the sample. The results were reported as pmol of phosphate incorporated into the substrate by active PKG in the sample in the presence or absence of cGMP (10 μm) per minute at 30 °C per μg of protein (pmol/min/μg). These results were extrapolated by comparing the spectrophotometrical values of the samples to the known activity (pmol/min) of a positive control. Kinetic constants were then determined using nonlinear regression (curve fit) analysis (GraphPad Prism Software Inc.). To determine the Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) for cGMP, the kinase assay was performed with varying cGMP concentrations (0–10 μm), whereas the ATP concentration remained constant (125 μm).

Immunocytochemistry

PASMC were grown on a coverslip, and at the end of the treatment protocol, the cells were washed with PBS, then fixed with 100% methanol (5 min), and then permeabilized in 0.1% PBS-Tween (20 min). The cells were then washed three times with PBS and blocked for nonspecific protein-protein interactions using 1% BSA in PBS (1 h). The antibodies, SM22-α (5 μg/ml) and PCNA (1 μg/ml), were diluted in 1% BSA in PBS, added, and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The cells were again washed three times with PBS and incubated in secondary antibody: Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (1/1000 dilution) for PCNA or Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat IgG (H+L) (1/1000 dilution) for SM22-α for 1 h in the dark. DAPI was used to stain the cell nuclei (blue) at a concentration of 0.5 μg/ml for 3 min. The cells were rinsed three times with PBS, and the coverslips were mounted on the slides with ProLong Gold Antifade and analyzed with the use of a Nikon Eclipse TE 300 inverted fluorescent microscope with a 60× oil objective and a Hamamatsu digital camera. SM22-α levels were quantified as the number of filamentous cells with granular green staining (SM22-α) divided by total number of cells and presented as the percentage of SM22-α positive cells. PCNA levels were quantified using ImageJ software as mean intensity of green staining inside the nucleus and presented as the nuclear PCNA intensity.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Downsized lungs and pulmonary hypertensive human lung tissue paraffin sections (5 μm) were mounted on slides and placed in a 55 °C oven for 10 min, deparaffinized in xylene (three times for 5 min), and then hydrated using an alcohol series: 100, 95, and 70% alcohol (each three times for 5 min) and finally rinsed in water. The sections were processed for antigen retrieval by boiling the slides in 10 mm citrate buffer (pH 6.0). The slides were then cooled at room temperature for 20 min, washed in PBS, and blocked in 10% normal serum overnight at 4 °C. Immunofluorescence was then performed on serial sections from each group using goat anti-PKG-1α, rabbit anti-3-NT-Y247-PKG-1α, and mouse anti-caldesmon antibodies (Sigma). The sections were incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature and washed (three times for 5 min) with PBS. Subsequently, sections were double-stained either with Alexa Fluor® 546 anti-goat or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Inc.) and Alexa Fluor® 488 anti-mouse secondary antibodies. Sections were washed several times in PBS and mounted on the coverslip in anti-fading aqueous mounting medium. The fluorescently stained sections were then analyzed using the appropriate excitation and emission wavelengths by performing confocal microscopy using a computer-based DeltaVision imaging system (Applied Precision Inc.).

MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry

At the end of the experimental protocol, PKG-1α was immunoprecipitated, as described above. The protein was resolved using 4–20% Tris-SDS-Hepes PAGE and visualized by imperial protein stain (Thermo-Fisher). The band corresponding to PKG-1α (75 kDa) was excised, destained, and subjected to overnight in-gel digestion with trypsin (25 ng/μl in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate buffer, pH 7.8). The peptides were extracted with 0.1% TFA, 75% acetonitrile and evaporated to near dryness. Mass spectrometry analysis of PKG-1α was then performed as described (1). All spectra were taken on an ABSciex 5800 MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer in positive reflector mode (10 kV) with a matrix of CHCA. At least 1000 laser shots were averaged to get each spectrum. The masses were calibrated to known peptide standards. Aliquots (5 μl) of the PKG-1α tryptic digest were taken up into a C18 ZipTip (Millipore) that had been prepared, as per the manufacturer's instructions. The bound peptides were desalted with two 5-μl washes of 0.1% TFA and then eluted with 2.5 μl of aqueous, acidic acetonitrile (75% CH3CN, 0.1% TFA). The eluate was mixed with 2.5 μl of freshly prepared CHCA stock solution (20 mg/ml CHCA in aqueous acetonitrile, as above), and 1.5-μl portions of this mixture were spotted onto a MALDI sample plate for air drying. Crude peptides (1.5 μl) were additionally mixed with CHCA (1.5 μl) and were spotted. The MS/MS of the 2209.04 m/z peak was done in positive reflector mode without CID. The MS and MS/MS spectra were analyzed in the Mascot Distiller software package.

Homology Modeling

Because a complete x-ray structure for PKG-1α is unavailable in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), we used the homology modeling module of YASARA (23) to build a high resolution model of PKG-1α from its amino acid sequence. The PKG-1α homology model was developed using the following protocol: a PSI-BLAST (24) integrated in YASARA was used to identify the closest templates in the PDB. As a template for the three-dimensional structure for the PKG-1α homology model, we used the regulatory (PDB code 1NE4) and catalytic (PDB code 2CPK) domains of PKA because PKA shares significant structural and functional similarities to PKG-1α. We used BLAST to retrieve homologous sequences, create a multiple sequence alignment, and enter the sequences into a “discrimination of secondary structure class” prediction algorithm (25). The side chains were added and optimized in the next step, and all of the newly modeled parts were subjected to a combined steepest descent and underwent simulated annealing minimization. The backbone atoms of the aligned residues were kept fixed. Finally, an unrestrained, simulated, annealing minimization with water was performed on the entire model. The resultant individual homology models of the PKG-1α regulatory domain and the catalytic domain were combined together to form a single PDB sequence. This new sequence was used as a template sequence for generating a complete homology model of PKG-1α resulting in a structure containing two cGMP-binding sites: A and B as well as an ATP-binding site. Subsequently, a simulation cell was placed around each ligand-binding site on the PKG-1α homology model to focus the docking of two cGMP molecules and one ATP molecule to their respective binding sites using the AutoDock program developed at the Scripps Research Institute. To simulate nitration, an NO2 group was introduced into the protein model on the ortho carbon of the phenolic ring of the Tyr247 residue. The structure was minimized, and the hydrogen bonding energy (kJ/mol) and distance (Å) between the cGMP molecule and the cGMP-binding site B of PKG-1α were analyzed in the presence or absence of the NO2 group again using YASARA.

[3H]cGMP Binding Assay

At the end of the experimental protocol WT- and Y247F-PKG-1α were immunopurified, as described above, quantified using Bradford reagent, and stored at −80 °C until used. To assay the binding of cGMP to WT- and Y247F-PKG-1α, the enzymes were saturated with cGMP by incubating 50-μl aliquots of the diluted PKG constructs for 60 min at room temperature with 50 μl of [3H]cGMP and 150 μl of cGMP binding assay mixture (25 mm K2HPO4, 25 mm KH2PO4, 1 mm EDTA, pH 6.8, 2 m NaCl, 200 μm 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine). The final cGMP concentration varied from 0 to 200 nm, and the final concentration of enzyme was 100 ng. After incubation, 2 ml of cold aqueous saturated (NH4)2SO4 was added to each sample. The samples were then filtered onto 0.45-μm pore nitrocellulose paper (Millipore) that had been premoistened with saturated (NH4)2SO4 and were then rinsed three times with 2 ml of cold saturated (NH4)2SO4. The papers were dried and shaken in vials containing 1.5 ml of 2% SDS. Aqueous scintillant (10 ml) was added; the vials were shaken again and then counted in a liquid scintillation counter. The dissociation constant (Kd) values were determined using GraphPad Prism graphics.

[3H]cGMP Dissociation/Exchange Assay

WT- and Y247F-PKG-1α were immunopurified, as described above then incubated for 60 min at room temperature with 3 ml of cGMP binding assay mixture containing 3 μm [3H]cGMP. This incubation time and dose has been previously experimentally determined to be adequate for the saturation of the cGMP-binding sites in PKG. After incubation, the samples were cooled to 4 °C and divided into a 200-μl aliquot per tube. The addition of 100-fold excess unlabeled cGMP at time 0 s (Bo) initiated the dissociation (exchange) of the bound [3H]cGMP. The cGMP exchange in each tube was stopped at the appropriate time point by the addition of 2 ml of cold aqueous saturated (NH4)2SO4. The samples were filtered and washed, and the portion of bound [3H]cGMP at any time point was determined, as described previously.

Analysis of PASMC Cell Growth

PASMC were grown on a 10-cm dish to 75% confluence, transfected with WT-PKG-1α or Y247F-PKG-1α cDNA using a Qiagen transfection kit, according to manufacturer's instructions, and incubated at 37 °C for 20 h. This method resulted in an ∼20% transfection efficiency (not shown). The cells were then trypsinized, seeded onto a 6-well plate at a density of 2.5 × 104 cells/well, and grown for an additional 4 h in serum-free DMEM growth medium containing 1% FBS and antibiotics. The cells were then treated with or without SIN-1 (500 μm) and allowed to grow at 37 °C in the incubator for an additional 48h. The cellular proliferation was evaluated by counting the cells with a hemacytometer (Cascade Biologicals, Portland, OR) after the trypsinization of the PASMC monolayers.

Analysis of PASMC Cellular Metabolism

This was determined via the AlamarBlue assay (AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK). The assay is based on the reducing ability of metabolically active cells to convert the active reagent, resazurin, into a fluorescent and colorimetric indicator, resorufin. The color change of the dye was determined at an excitation wavelength of 560 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm in a Fluoroskan Ascent plate reader. Cells exposed to 0.1% Triton X-100 were used as a negative control, whereas medium containing AlamarBlue dye autoclaved for 15 min was used to obtain the 100% reduced form of AlamarBlue (positive control). Cellular metabolism was expressed as follows: percentage of reduction of AlamarBlue = (sample value − negative control)/(positive control − negative control) × 100%.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The mean ± S.E. was calculated in all experiments, and statistical significance was determined either by the unpaired t test (for 2 groups) or analysis of variance (for ≥3 groups). For the analysis of variance analyses, Newman-Kuels post hoc testing was employed. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

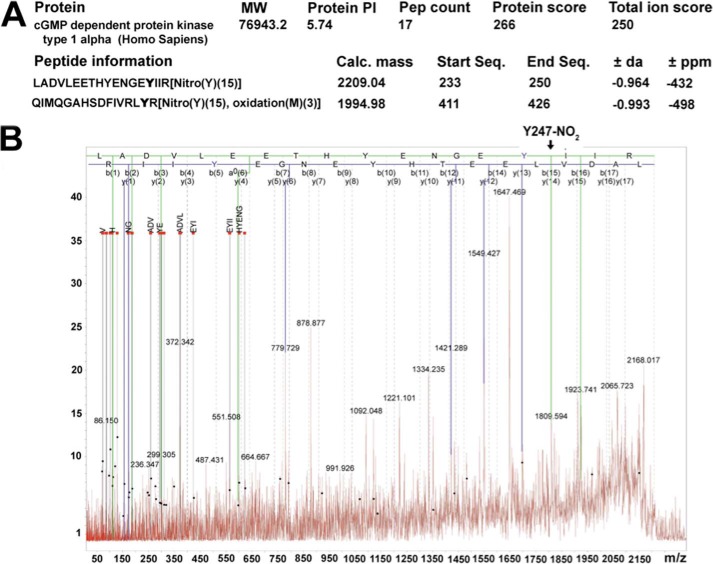

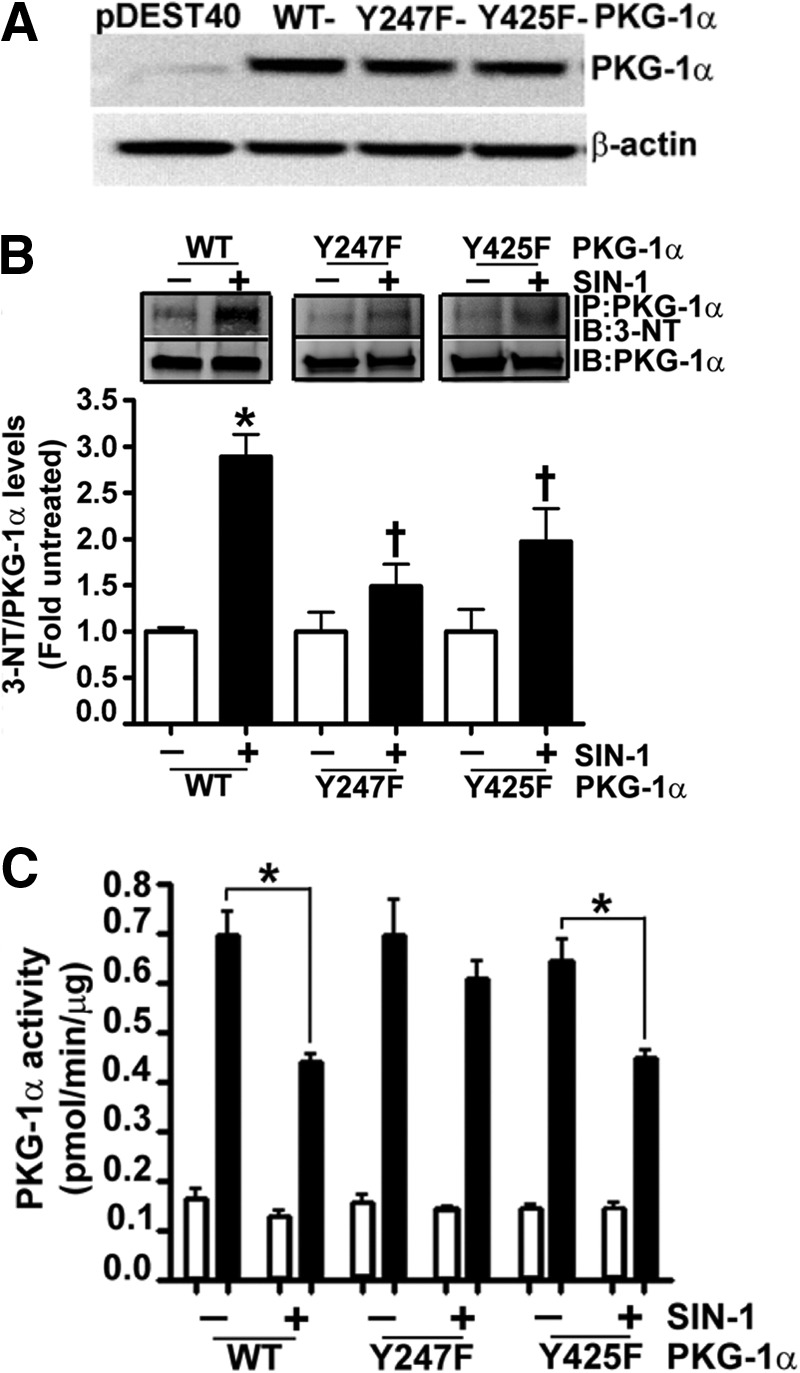

We have previously shown that the nitration of PKG-1α is associated with an attenuation of kinase activity (1). However, the tyrosine residues susceptible to this post-translational event are unknown. To identify these residues, we transfected HEK-293T cells with an expression plasmid containing a WT-PKG-1α cDNA and then exposed the cells to the peroxynitrite generator, SIN-1. PKG-1α was then immunopurified and trypsinized, and MS was performed on the extracted peptides. Our results demonstrated that Tyr247 and Tyr425 of PKG-1α were nitrated (Fig. 1A). MS/MS was then performed to verify the tyrosine nitration sites within PKG-1α. However, because of the low intensity of the peak corresponding to Tyr425, MS/MS could only confirm the nitration of Tyr247, suggesting that Tyr425 is a poor nitration site (Fig. 1B). To determine the role of tyrosine 247 and 425 in mediating the nitration-dependent inhibition of PKG-1α kinase activity, we generated Y247F- and Y425F-PKG-1α mutants and expressed them in HEK-293T cells (Fig. 2A). When these cells were exposed to SIN-1, there was an increase in PKG-1α nitration in cells overexpressing WT-PKG-1α (Fig. 2B). However, the levels of nitrated PKG-1α did not significantly increase in the cells transfected with either the Y247F- or Y425F-PKG-1α mutant (Fig. 2B). The moderate increase in the nitration levels of PKG-1α in the cells expressing either the Y247F or the Y425F mutant may be due to the nitration of the other tyrosine site. SIN-1 did not affect basal PKG-1α activity (without exogenous cGMP activation) (Fig. 2C). The cGMP-dependent increase in PKG-1α activity in the cells transfected with WT- or Y425F-PKG-1α was attenuated in the presence of SIN-1 (Fig. 2C). However, the activity of the Y247F PKG-1α mutant was unaffected (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that Tyr247 is involved in the nitration-mediated decrease in PKG-1α activity.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of the nitration sites on human PKG-1α. HEK-293T cells were transfected with an expression plasmid containing full-length WT-PKG-1α cDNA. After 48 h, the cells were exposed or not to SIN-1 (500 μm) for 30 min. The cells were lysed; PKG-1α was immunoprecipitated, and the protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and staining by imperial protein stain. The band corresponding to PKG-1α was excised and trypsinized, and MS was performed on the extracted peptides. MS analysis of the human 3-NT modified PKG-1α sequence, LADVLEETHYENGEYIIR, corresponding to the peptide comprising the amino acids 233–250, and the sequence, QIMQGAHSDFIVRLYR, corresponding to the peptide comprising the amino acids 411–426, demonstrated the nitration of Tyr247 and Tyr425 (A). The peptide with m/z 2209.04 (parent peptide LADVLEETHYENGEYIIR with m/z 2164.04 + 45 Da of nitro group) was further fragmented, and MS/MS data were analyzed (B). Solid lines represent the predicted masses for the nitrated peptide found in the MS/MS with an error less than 0.5 ppm. The MS/MS spectrum of the 2209.04 m/z ion was obtained in positive reflector mode fitted with peptide 233LADVLEETHYENGEY(NO2)IIR250 from the PKG-1α sequence.

FIGURE 2.

Nitration of Tyr247 attenuates PKG-1α activity. HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids containing WT-, Y247F-, or Y425F-PKG-1α for 48 h. Immunoblot analysis verified increased expression of PKG-1α (A). Cells were also treated or not with SIN-1 (500 μm, 30 min). Protein extracts were immunoprecipitated using an antibody raised against PKG-1α, and the level of nitrated PKG-1α was determined by probing the membranes with an antiserum raised against 3-NT. The blots were then stripped and reprobed for PKG-1α to normalize for the efficiency of the immunoprecipitation. A representative blot is shown (B). The nitration of WT-PKG-1α was significantly increased in the presence of SIN-1 (B). However, there were no significant increases in the nitration levels of Y247F- or Y425F-PKG-1α in the presence of SIN-1 (B). Although SIN-1 did not alter cGMP-independent PKG activity (white bars), cGMP-dependent PKG activity was attenuated in cells expressing WT- and Y425F-PKG-1α, but not in cells expressing Y247F-PKG-1α (black bars, C). The data are means ± S.E., n = 3–7. *, p < 0.05 versus untreated WT-PKG-1α and Y425F-PKG-1α. IB, immunoblotting; IP, immunoprecipitation.

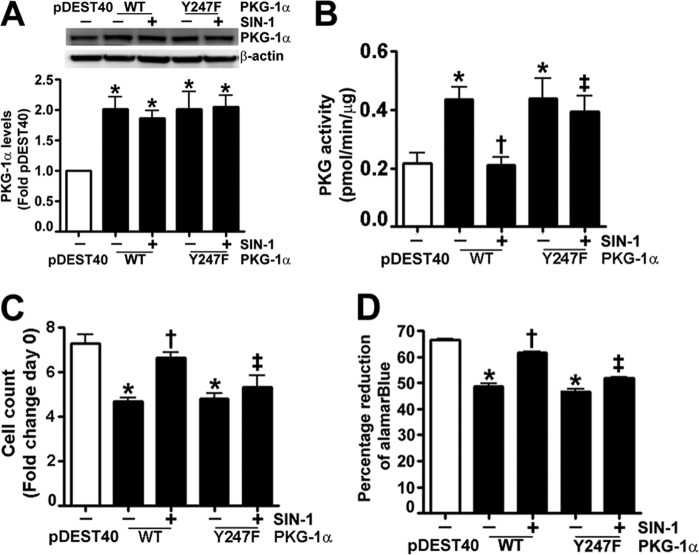

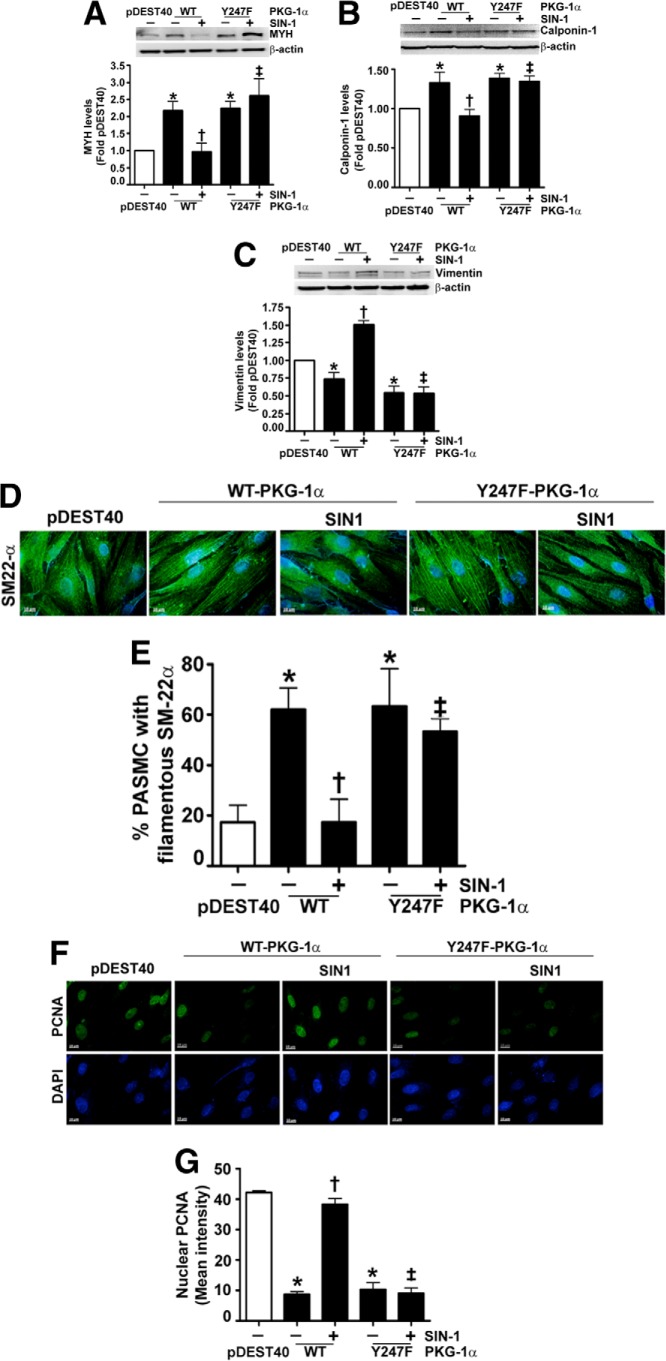

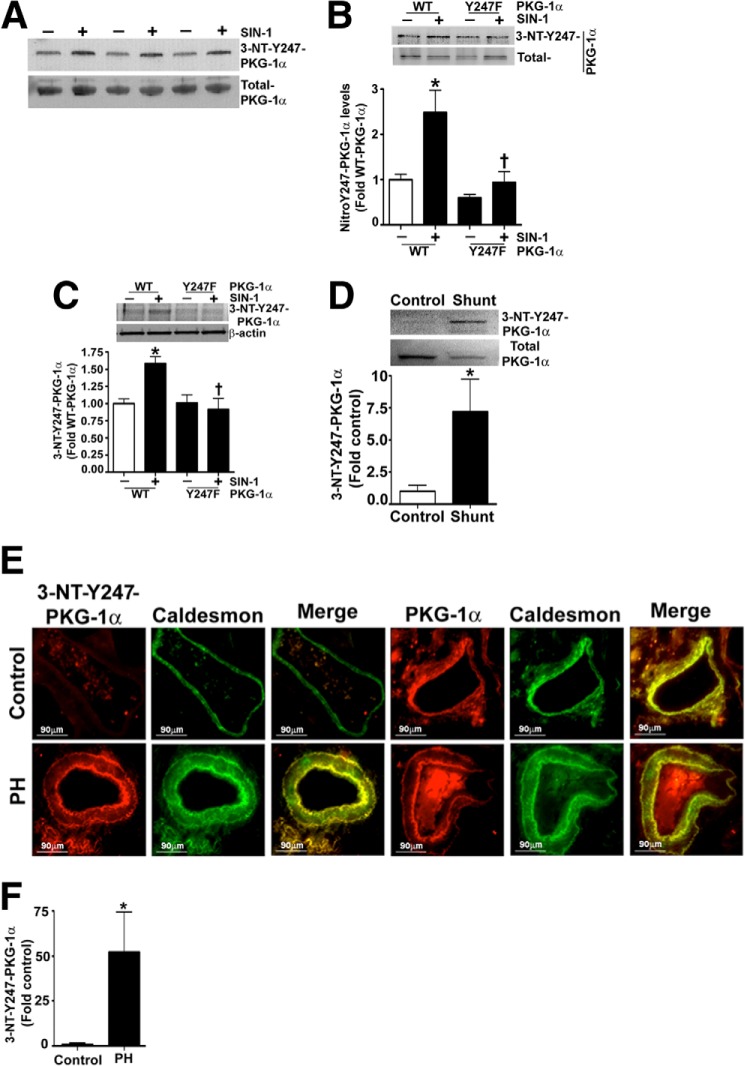

Past studies have demonstrated that the expression of PKG-1 results in decreased proliferation (26, 27) and acquisition of a contractile phenotype in VSMC (28). Therefore, we next investigated the effect on these events in PASMC transiently transfected with expression plasmids containing WT- and Y247F-PKG-1α (Fig. 3A). We first confirmed that SIN-1 attenuated PKG kinase activity in cells transfected with WT-PKG-1α but not in cells expressing Y247F-PKG-1α (Fig. 3B). The effect on PASMC proliferation (Fig. 3C) and metabolic activity was then determined (Fig. 3D). Our results demonstrated that PASMC transfected with either WT- or Y247F-PKG-1α had lower cell counts and metabolic activity compared with those transfected with the parental vector, pDEST40. SIN-1 exposure induced proliferation and metabolic activity in the PASMC expressing WT-PKG-1α but not in the cells transfected with the Y247F-PKG-1α mutant (Fig. 3, C and D). Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that PASMC transfected with WT- and Y247F-PKG-1α (Fig. 3A) exhibited a contractile phenotype, as illustrated by the increased levels of the contractile markers: MYH and calponin-1 (Fig. 4, A and B) and decreased levels of the proliferative marker vimentin (Fig. 4C). However, when exposed to SIN-1, WT-PKG-1α expressing PASMC acquired a more proliferative phenotype compared with the cells transfected with the Y247F-PKG-1α mutant (Fig. 4, A–C). Our immunocytochemistry analysis also found that the PASMC transfected with the WT- and the Y247F-PKG-1α were spindle-shaped and had increased expression of the contractile phenotype marker, SM22-α, bound to actin stress fibers (Fig. 4, D and E). In contrast, the nuclear levels of the proliferative marker protein, PCNA, were decreased (Fig. 4, F and G) in these cells. SIN-1 treatment attenuated SM-22α expression and increased PCNA staining in the WT- but not in the Y247F-PKG-α-expressing cells, suggesting that the Y247F-PKG-α mutant is resistant to phenotype modulation by nitrosative stress. Next, we developed an anti-Y247-PKG-1α antibody to directly analyze the nitration of Tyr247 in cells and tissues. To confirm its specificity to nitrated Y247-PKG-1α, we utilized immunoblot analysis to demonstrate that this antibody detected higher levels of 3-NT-Y247-PKG-1α in SIN-1-treated recombinant PKG-1α (Fig. 5A) and in HEK-293 cells (Fig. 5B) and PASMC (Fig. 5C) transfected with WT-PKG-1α compared with cells transfected with the Y247F-PKG-1α mutant. This antibody also detected high levels of Tyr247 nitration in the peripheral lung tissue of lambs with pulmonary hypertension secondary to increased pulmonary blood flow (Fig. 5D), confirming our earlier study (1). Further, immunohistochemical analysis identified greater signal in the pulmonary vessels from patients suffering from idiopathic pulmonary hypertension (3) compared with controls (Fig. 5, E and F). Together these data indicate that the nitration of Tyr247 is an important mechanism by which nitrosative stress impairs PKG-1α activity both in vitro and in vivo.

FIGURE 3.

The effect of nitration on pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell growth and metabolism. PASMC were transiently transfected with expression plasmids containing WT-PKG-1α, Y247F-PKG-1α, or pDEST40 (as a control) for 20 h. Cells were then exposed or not to SIN-1 (500 μm, 48 h), and the effect on PKG protein levels (A) and activity was determined (B). SIN-1 had no effect on PKG-1α protein levels but attenuated the cGMP-dependent increase in PKG activity in the cells transfected with WT-PKG-1α, but not those expressing the Y247F PKG-1α mutant (A). The effects of SIN-1 on cellular proliferation (C) and cellular metabolic activity (D) were also determined. PASMC expressing either WT- or Y247F-PKG-1α were less proliferative and metabolically active than the pDEST40 transfected control cells. SIN-1 exposure stimulated proliferation and metabolism in WT-, but not Y247F-PKG-1α-transfected PASMC. The transfection efficiency in the PASMC was ∼20%. The data are means ± S.E., n = 4. *, p < 0.05 versus pDEST40; †, p < 0.05 versus WT-PKG-1α; ‡, p < 0.05 versus WT-PKG-1α + SIN-1.

FIGURE 4.

The effect of nitration on pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell phenotype. PASMC were transiently transfected with expression plasmids containing WT-PKG-1α, Y247F-PKG-1α, or PDEST40 (as a control) for 20 h. Cells were then exposed or not to SIN-1 (500 μm, 48 h), and the effect on synthetic and contractile markers was determined. The levels of MYH (A), calponin-1 (B), and vimentin (C) were determined. The blots were then stripped and reprobed for β-actin to normalize for protein loading. A representative blot is shown for each. Under basal conditions, PASMC transfected with the WT- and the Y247F-PKG-1α exhibited increased expression of the contractile markers MYH and calponin-1 and decreased expression of the proliferative marker vimentin, indicative of a contractile phenotype. SIN-1 decreased the expression of the contractile markers MYH and calponin-1 and increased the expression of the proliferative marker, vimentin, in the WT-PKG-1α-transfected cells, indicative of a proliferative phenotype. The Y247F PKG-1α-expressing cells were resistant to this phenotypic conversion. PASMC were also subjected to immunohistochemistry using antibodies to SM22-α (5 μg/ml) and PCNA (1 μg/ml). Relevant secondary antibodies linked to Alexa Fluor 488 were then applied (green). DAPI was also used to stain the cell nuclei (blue). PASMC expressing WT- or Y247F-PKG-1α acquired a contractile phenotype with the increased filamentous binding of the SM22-α protein on the actin stress fibers (D and E). The nuclear localization of PCNA was also reduced in these cells (F and G). However, when PASMC were treated with SIN-1, the WT PKG-1α-expressing cells exhibited decreased filamentous SM22-α expression and increased nuclear staining of PCNA, whereas the Y247F-PKG-1α-expressing cells were unaffected. The data are means ± S.E., n = 4–7. *, p < 0.05 versus pDEST40; †, p < 0.05 versus WT-PKG-1α; ‡, p < 0.05 versus WT-PKG-1α + SIN-1.

FIGURE 5.

Identification of Y247-PKG-1α nitration in vitro and in vivo. Recombinant PKG-1α protein (A) was incubated in the presence or absence of SIN-1 (500 μm, 30 min). The protein was immunoblotted and probed with an antibody raised against 3-NT-Y247-PKG-1α and then normalized with total PKG-1α antibody. Our results demonstrate that 3-NT-Y247-PKG-1α antibody preferentially binds to the nitrated PKG-1α. In addition, HEK-293T cells (B) or PASMC (C) were transiently transfected with expression plasmids containing WT- or Y247F-PKG-1α for 48 h. Cells were then treated or not with SIN-1 (500 μm, 30 min). Protein extracts were immunoblotted and probed with anti-3-NT-Y247-PKG-1α antibody. The blots were then stripped and reprobed for total PKG-1α and β-actin to normalize loading. WT-PKG-1α nitration was significantly increased in the presence of SIN-1. However, there were no significant increases in the nitration levels of Y247F-PKG-1α in the presence of SIN-1. The 3-NT-Y247-PKG-1α antibody also detected higher PKG-1α nitration levels in peripheral lung tissues of lambs with pulmonary hypertension secondary to increased pulmonary blood flow (D). Finally, immunohistochemical analysis was performed on lung sections prepared from humans with pulmonary hypertension (PH). The antibodies used were goat anti-PKG-1α (red), 3-NT-Y247-PKG-1α (red), and anti-caldesmon (green). The fluorescently stained sections were then analyzed using confocal microscopy and a representative image is shown (E). The 3-NT-Y247-PKG-1α antibody identified significantly higher levels of nitrated PKG-1α in the lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertensive (F), and this was predominant in the smooth muscle layer (E). The data are means ± S.E., n = 3–6. *, p < 0.05 versus untreated WT-PKG-1α for B and C, control lambs for D, and normal human reference lungs for F. †, p < 0.05 versus WT-PKG-1α + SIN-1 (B and C).

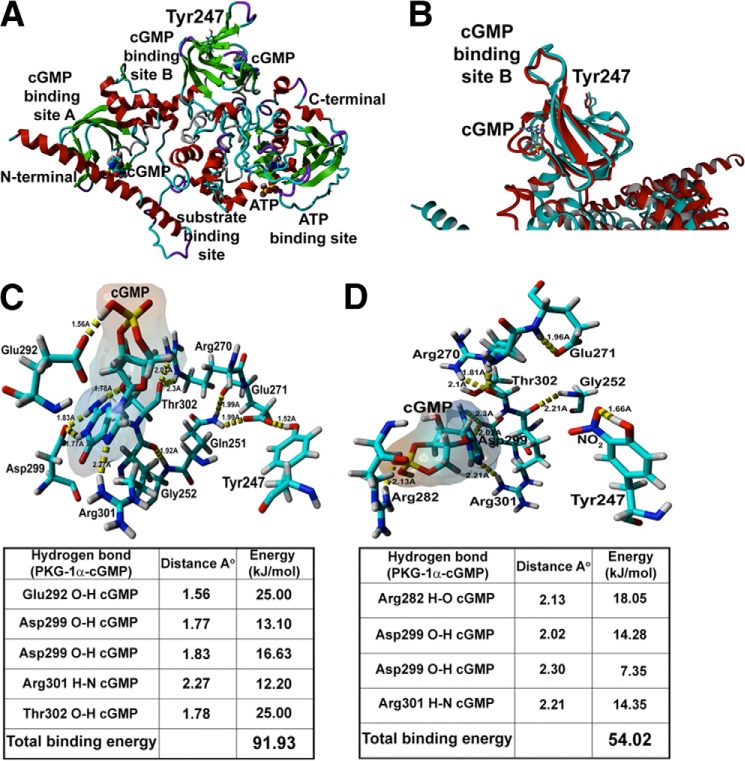

To further understand the molecular mechanism(s) by which nitration of Tyr247 impairs PKG-1α activity, we developed a homology model of full-length PKG-1α protein. Because of the labile structure of PKG-1, only the dimerization region in the regulatory domain in PKG-1β (29) and the regulatory domains of PKG-1α (aa 78–355) (30) and PKG-1β (aa 92–227) (31) have been crystallized and characterized. Therefore, we used the known crystal structures of the regulatory (PDB code 1NE4) and the catalytic (PDB code 2CPK) domains of PKA as templates, which share significant structural and functional homology with PKG-1α, to build our homology model. The analysis of the resulting three-dimensional PKG-1α structure indicated that Tyr247 shares a close proximity to the cGMP-binding site B (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, superimposition of the known crystal structure of the cGMP-binding site B of PKG-1α (30) showed high similarity with the cGMP-binding site B of our homology model (Fig. 6B), even though this crystal structure was not used to build the model.

FIGURE 6.

Generation of a homology model of human PKG-1α. The YASARA homology modeling software was used to build a homology model of the PKG-1α regulatory domain using the known crystal structure of the PKA regulatory domain (PDB code 1NE4), as a template. The known crystal structure of the catalytic domain of PKA (PDB code 2CPK) was used to construct the corresponding homology model of the catalytic domain of PKG-1α. Using the homology models of these two domains of PKG-1α, a complete three-dimensional model of the protein was generated. The AutoDock program was then used to dock two cGMP molecules to the cGMP-binding sites: A and B and an ATP molecule to the ATP-binding site. The analysis of the PKG-1α structure indicates that Tyr247 lies in close proximity to the cGMP-binding site B (A). Further, the comparison of the recently crystallized structure of PKG-1α and our homology model demonstrated high similarity within the cGMP-binding site B, even though this crystal structure was not used to build our homology model (B). The YASARA homology modeling software was also used to predict the affinity of cGMP for the cGMP-binding site B in the PKG-1α homology model under control (C) and nitrosative stress conditions (D). The addition of a NO2 group to Tyr247 is predicted to decrease the total hydrogen bonding energy between cGMP and PKG-1α from 91.93 to 54.02 kJ/mol (C and D).

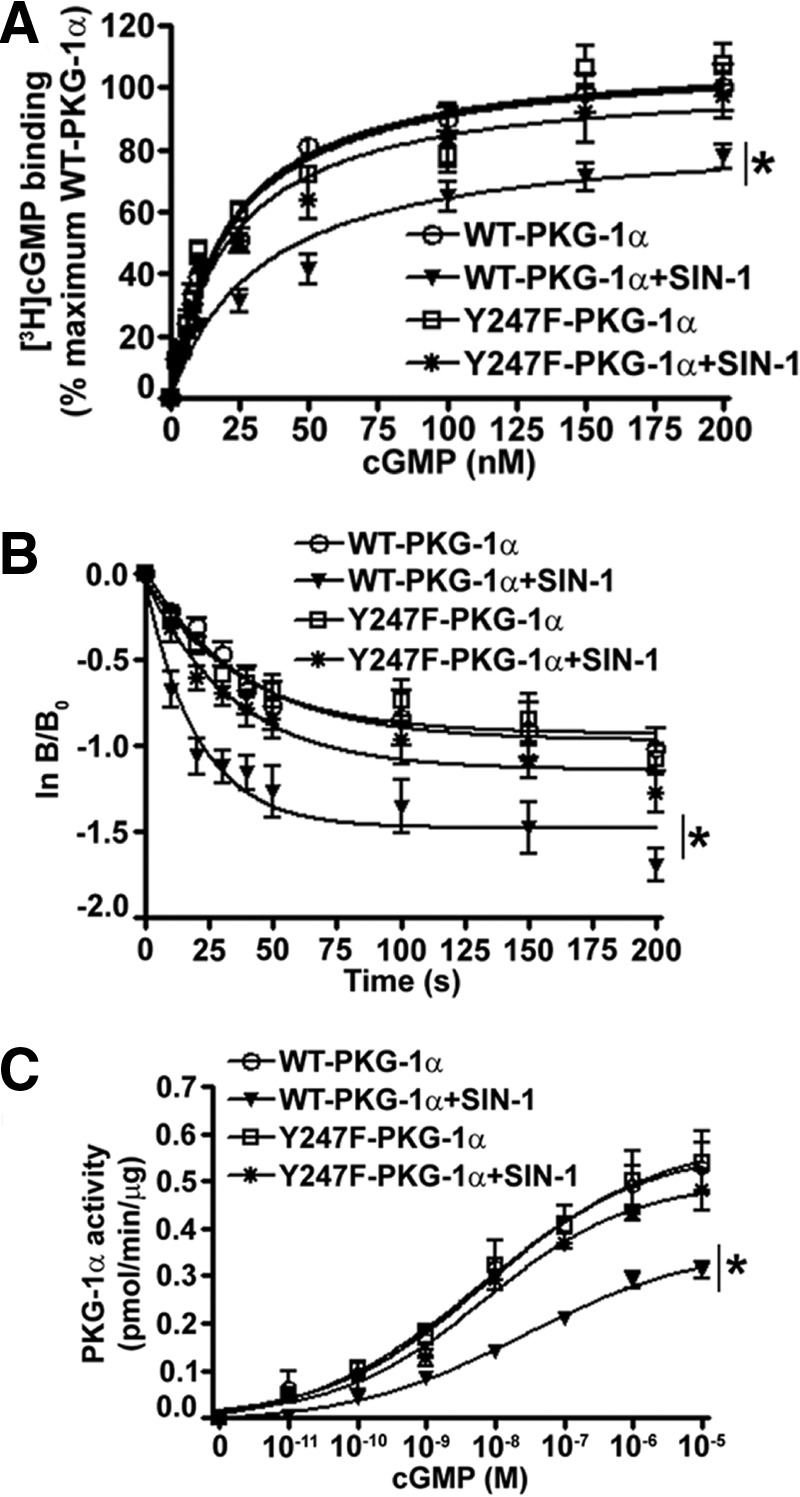

Further, molecular dynamic simulations in our model after the addition of a NO2 group to the Tyr247 predicted the loss of a hydrogen bond between the cGMP molecule and threonine 302 of PKG-1α, the residue responsible for nucleotide specificity of cGMP-binding site B (Fig. 6C). Further, the NO2 group was predicted to displace the hydrogen bond between cGMP and glutamate 292 and form a new hydrogen bond between cGMP and arginine 282 of PKG-1α (Fig. 6D). Thus, in total, the nitration of Tyr247 should result in a net loss of 1 hydrogen bond between cGMP and PKG-1α and an increase in bond lengths with a predicted net decrease in total hydrogen bonding energy between cGMP and PKG-1α from 91.93 to 54.02 kJ/mol (Fig. 6, C and D). To test the predictions made by our homology model, we assessed the influence of nitrosative stress on the affinity of PKG-1α for cGMP by performing [3H]cGMP binding studies. We transfected HEK-293T cells with either WT- or Y247F-PKG-1α and treated the cells with SIN-1. The PKG protein was immunopurified, and a binding assay was performed in the presence of increasing concentrations of [3H]cGMP. In the absence of SIN-1, the cGMP-binding stoichiometry of the Y247F-PKG-1α mutant was comparable with that of the WT-PKG-1α (Fig. 7A). However, the Kd values obtained for the WT-PKG-1α after SIN-1 treatment were higher than those obtained from the SIN-1 treated Y247F mutant (Fig. 7A and Table 1). The Kd values derived from these experiments were an average affinity of the two cGMP-binding sites within PKG-1α, and the binding characteristics of the individual sites, A and B, could not be assessed. To further confirm these results, a second measure of affinity was performed using cGMP exchange/dissociation analysis of the WT- and the Y247F-PKG-1α. In the absence of SIN-1, our results demonstrated that the [3H]cGMP exchange/dissociation was biphasic (rapid versus slow exchange) in the WT- and in the Y247F-PKG-1α dissociation curves, consistent with the presence of two kinetically distinct cGMP-binding sites (sites A and B). However, SIN-1 exposure enhanced [3H]cGMP exchange/dissociation from the WT-PKG-1α but not from the Y247F mutant (Fig. 7B and Table 1). Further, SIN-1 decreased the dissociation/exchange rate (T½), or the time required for cGMP to dissociate from half the binding sites on PKG-Iα in the WT-PKG-1α, from 27.06 to 14.22 s, whereas no change was observed in the Y247F mutant (Table 1).

FIGURE 7.

The cGMP binding and dissociation characteristics of PKG-1α under nitrosative stress. PASMC were transiently transfected with expression plasmids containing WT- or Y247F-PKG-1α for 48 h. The cells were then serum-starved for 4 h and exposed or not to SIN-1 (500 μm, 30 min), and PKG-1α was immunoprecipitated. Immunoprecipitated WT- and Y247F-PKG-1α protein (100 ng) was then analyzed in a [3H]cGMP binding assay (A) and a [3H]cGMP dissociation assay (B). SIN-1 treatment significantly attenuated maximal [3H]cGMP binding to WT-PKG-1α, but not to the Y247F-PKG-1α mutant (A). In the dissociation assay, a 100-fold excess of unlabeled cGMP was added at time 0 s (Bo) to initiate the dissociation (exchange) of bound [3H]cGMP. The reaction was stopped with cold aqueous saturated (NH4)2SO4 at various time points. The results were plotted as ln(B/Bo) with Bo as the initial [3H]cGMP bound] and B as the [3H]cGMP remaining bound at various time points. SIN-1 treatment enhanced the dissociation/exchange of [3H]cGMP from WT-PKG-1α, but not from Y247F-PKG-1α (B). Enzyme kinetics were also determined using varying concentrations of cGMP (0–10 μm). The change in the enzyme activity for each concentration of cGMP was plotted in pmol/min/μg protein using nonlinear regression (curve fit) analysis. The maximum velocity (Vmax) of the phosphotransferase reaction of WT-PKG-1α, but not Y247F-PKG-1α, was significantly decreased with SIN-1 exposure (C). Each value represents the mean of three separate experiments. The data are means ± S.E., n = 3. *, p < 0.05 versus untreated WT-PKG-1α.

TABLE 1.

Michaelis-Menten kinetics of wild type and Y247F-PKG-1α in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells in the presence and absence of nitrative stress

| Treatment | Kd | T½ | Vmax | Km |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | s | pmol/min/μg | nm | |

| WT-PKG-1α | 21.34 ± 2.2 | 27.06 | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 2.73 ± 0.99 |

| WT-PKG-1α + SIN-1 | 32.12 ± 5.5 | 14.22 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 8.91 ± 2.69 |

| Y247F-PKG-1α | 20.43 ± 2.8 | 26.02 | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 2.43 ± 1.03 |

| Y247F-PKG-1α + SIN-1 | 21.54 ± 3.4 | 23.79 | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 3.26 ± 0.99 |

Our cGMP binding and dissociation studies suggested that the phosphotransferase reaction catalyzed by PKG-1α may require a higher concentration of cGMP to reach the maximum velocity (Vmax) under nitrosative stress. Therefore, we performed Michaelis-Menten kinetics to determine the cGMP concentrations required for PKG-1α to achieve half of the maximum velocity (Km). Utilizing a nonlinear regression curve, we demonstrated that, at constant ATP levels (125 μm) and varying cGMP concentrations (0–10 μm), SIN-1 challenge decreased the Vmax of the reaction of the WT-PKG-1α, but not of the Y247F mutant PKG-1α, from 0.47 to 0.28 pmol/min/μg protein (Fig. 7C and Table 1). Further, our results showed that the Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) increased from 2.73 to 8.91 nm for cGMP in the WT-PKG-1α upon SIN-1 treatment, whereas no significant change was observed in the Y247F mutant (Fig. 7C and Table 1).

DISCUSSION

The nitration and subsequent attenuation of PKG-1α catalytic activity appears to be an important pathological event underlying the development of vascular dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension and other vascular pathologies (1, 3, 32). However, the molecular mechanisms by which tyrosine nitration of PKG-1α attenuates the catalytic activity are not known. In this study, we have developed a molecular model of PKG-1α and demonstrated that the nitration of Tyr247 in the cGMP-binding domain B reduces the binding of cGMP to the enzyme and impairs the catalytic activity of PKG-1α. In conjunction with our past study and the studies from other laboratories, our data underscore the critical role of PKG-1α nitration in attenuating downstream NO/cGMP signaling.

In addition to its role in mediating the vasodilator effects of NO, PKG contributes to the maintenance of a contractile-like phenotype in SMC, and the suppression of PKG expression/activity in vitro induces a more synthetic, dedifferentiated phenotype (33). The transition of VSMC from a contractile to a proliferative phenotype appears to be an early event in various pathologies, such as pulmonary hypertension, atherosclerosis, and restenosis (34–36) and is associated with increased oxidative and nitrosative stress (37–39). Although the precise mechanisms by which oxidative stress induces a proliferative phenotype are still unresolved, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species have been shown to attenuate PKG-1α signaling in both experimental and human forms of pulmonary hypertension as a result of diminished catalytic activity (1, 3) or protein expression (2). Protein nitration is now emerging as an important post-translational event responsible for attenuating PKG-1α activity. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species levels are increased in pulmonary hypertensive mice (40), lambs (1), and humans (3), and the increase in oxidative and nitrosative stress is implicated in both vasoconstriction (41) and vascular remodeling (42). Our recent studies have identified nitration and the ensuing attenuation of PKG-1α activity in the lungs of lambs with pulmonary hypertension secondary to increased pulmonary blood flow and in lambs with rebound pulmonary hypertension associated with the acute withdrawal of inhaled NO therapy (1). In addition, the nitration and subsequent attenuation of PKG activity in the right ventricle appears to be responsible for the deterioration of right ventricle function in a mouse model of pulmonary hypertensive induced by chronic hypoxia (43). However, the increase in protein nitration associated with hypoxia reduces PKG activity through changes at the transcriptional and post-translational levels (2). The clinical relevance of PKG nitration has also been shown by the observation that patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension have increased PKG nitration in their lungs with no noticeable alteration in PKG protein levels (3). Thus, the accumulated data suggest that the nitration-dependent impairment of PKG activity may be a critical event in the development of vascular dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension.

Tyrosine nitration is a selective process because not all tyrosine residues in a protein undergo nitration under pathophysiological conditions (44). PKG-1α has 21 tyrosine residues in its monomeric structure, of which 9 tyrosines are located in the regulatory domain and 12 are part of the catalytic domain. Using MS and mutational studies, we found that the nitration of tyrosine 247, located within the cGMP-binding site B of the regulatory domain of PKG-1α, is responsible for the impaired kinase activity. Cyclic GMP binding to both sites A and B of PKG brings about a conformational change necessary for full kinase activity. The two cGMP-binding sites share ∼37% amino acid sequence similarity but differ in their cGMP binding kinetics (45). This difference may be due to the number of hydrogen bonds between cGMP and the cGMP-binding sites on PKG, as well as the length of these bonds (31). Molecular dynamic simulations using our full-length PKG-1α homology model predicted that the nitration of Tyr247 impairs hydrogen bonding between cGMP and the cGMP-binding site B of the kinase. These results were confirmed by our in vitro [3H]cGMP binding studies and reveal a novel mechanism by which PKG is regulated by nitrosative stress. Although site B is a low affinity site that is presumably occupied at higher cGMP levels, previous studies have shown that the binding of cGMP to site B positively influences the binding of cGMP to site A (positive cooperativity) (15). It is therefore possible that the nitration of Tyr247, which hinders cGMP binding to site B also hampers the full saturation at site A. Hence, even at saturating levels of cGMP for the non-nitrated enzyme, the kinase activity seems to be lower in the nitrated protein. Our findings are also in agreement with other studies that have also shown that the negative charge imparted by nitration alters the hydrogen bonding network between the substrate and protein in such enzymes as manganese superoxide dismutase (46), glutathione reductase (47), and prostacyclin synthase (48). However, it should be noted that our results appear to be contradictory to a previous study. In this study, single tyrosine to phenylalanine mutations of all tyrosine residues located in the catalytic domain of human PKG-1α were generated, and Y345F- and the Y549F-PKG-1α mutants were found to be resistant to nitration-dependent inhibition (3). Several differences between the studies may explain these apparently conflicting findings. First, Tyr345 in PKG-1α is located in the hinge/switch region (aa 328–355) between the regulatory and the catalytic domain and acts as a tether for the catalytic domain (30). Mutations in this switch region have been shown to cause the kinase to be more active, presumably independent of cGMP (30). Second, based on our homology model, Tyr549 of PKG-1α is located within the catalytic domain and interacts with the pseudo-substrate site, maintaining the enzyme in an autoinhibited state (49, 50). The autoinhibition of PKG-1α is relieved by the conformational change caused by either cGMP binding or autophosphorylation, which disrupts the autoinhibitory interaction between the regulatory and catalytic domains (12, 13, 51). The structural alterations resulting from the replacement of the tyrosine with a phenylalanine at residue 549 could result in a conformational change, thereby relieving this basal inhibition. Under both these circumstances, the nitration of Tyr247 observed in our study would not influence the kinase activity of these PKG-1α mutants, because our data indicate that the nitration of Tyr247 inhibits only the cGMP-inducible activation of PKG-1α.

A previous study has indicated that SIN-1 treatment decreased both basal and cGMP-dependent PKG activity in VSMC (3), whereas we found that basal PKG activity was unchanged in HEK-293 exposed to SIN-1. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear. However, it should be noted that the regulation of PKG enzyme activity under both basal and stimulated conditions is complex. In the cGMP starved state, the enzyme activity (basal) is mediated by either autophosphorylation or the binding of limited cGMP to the high affinity site A on PKG. However, during cGMP abundant states, the enzyme activity (active) is mediated by the binding of cGMP to both the high affinity site A and the low affinity site B (17). It has also been shown that the binding of cGMP or cAMP to site A enhances the autophosphorylation of PKG (52), whereas the binding of cGMP to both cGMP-binding sites A and B prevents autophosphorylation. The autophosphorylation of PKG-1 increases basal kinase activity 3–4-fold (52) in comparison with a 3–10-fold increase by cGMP binding to both sites (53). The sites of autophosphorylation are different for PKG-1α and PKG-1β, and they are also differentially regulated (52, 54, 55). Because PKG-1α and PKG-1β are both expressed in VSMC; therefore, it is possible that the decrease in basal activity in the VSMC exposed to SIN-1 may be attributed to the differential regulation of PKG-1β in VSMC. Additionally, it is possible that the levels of endogenous cGMP and cAMP bound to site A of PKG may vary in VSMC and HEK-293 cells in the basal state. Based upon our findings, we speculate that the nitration of PKG-1α may not be a predominant mechanism regulating PKG activity under basal (low cGMP) conditions. However, under pathological conditions, the vasodilatory response of the nitric oxide/cGMP signaling will be attenuated because of decreased cGMP binding to PKG-1α, resulting in the suboptimal activation.

In conclusion, our data, in combination with recent studies (2, 3), suggest that the nitration of PKG-1α may be a common mechanism underlying vascular dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension and other disorders. Our study has identified nitration of Tyr247 as being responsible for the attenuation of PKG-1α catalytic activity. Therefore, we speculate that strategies aimed at minimizing PKG-1α nitration may have adjunct therapeutic value in the treatment of vascular disorders. Current therapeutic interventions for ameliorating multiple vascular disorders are aimed at increasing intracellular cGMP levels. These management strategies include inhaled NO therapy for pulmonary hypertension; NO donors, such as nitroglycerin, isosorbide dinitrate, or isosorbide mononitrate for coronary artery diseases; cGMP specific phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors sildenafil and tadalafil for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension and erectile dysfunction; and B-type natriuretic peptides for hypoxemic respiratory failure. The major goal of these therapies is to increase the production of cGMP or inhibit its breakdown and thereby increase vascular dilation. However, based on our data and studies from other groups, we speculate that the management approach could also include cell or protein specific targeting of anti-oxidants, the development of nitration site shielding peptides, or perhaps interventions to enhance the autophosphorylation of PKG-1 that, in combination, would minimize the external requirement of cGMP-dependent enzyme activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marius M. Hoeper (Department of Respiratory Medicine, Hannover Medical School) and Gregor Warnecke (Department of Thoracic Surgery, Hannover Medical School) for providing clinical data and surgical samples from human patients, as well as Lavinia Maegel, Nicole Izykowski, and Regina Engelhardt (Institute of Pathology, Hannover Medical School) for excellent technical support.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL60190, HL67841, HL084739, and HL0101902 (to S. M. B.) and HL061284 (to J. R. F.). This work was also supported by incubator and programmatic awards from the Cardiovascular Discovery Institute of Georgia Regents University (to S. M. B.).

- PKG

- protein kinase G

- SMC

- smooth muscle cell

- VSMC

- vascular SMC

- PASMC

- pulmonary artery SMC

- aa

- amino acid(s)

- PCNA

- proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- MYH

- myosin heavy chain

- SIN-1

- 3-morpholinosydnonimine N-ethylcarbamide

- 3-NT

- 3-nitrotyrosine

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- CHCA

- α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aggarwal S., Gross C. M., Kumar S., Datar S., Oishi P., Kalkan G., Schreiber C., Fratz S., Fineman J. R., Black S. M. (2011) Attenuated vasodilatation in lambs with endogenous and exogenous activation of cGMP signaling. Role of protein kinase G nitration. J. Cell. Physiol. 226, 3104–3113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Negash S., Gao Y., Zhou W., Liu J., Chinta S., Raj J. U. (2007) Regulation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase-mediated vasodilation by hypoxia-induced reactive species in ovine fetal pulmonary veins. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 293, L1012–L1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhao Y. Y., Zhao Y. D., Mirza M. K., Huang J. H., Potula H. H., Vogel S. M., Brovkovych V., Yuan J. X., Wharton J., Malik A. B. (2009) Persistent eNOS activation secondary to caveolin-1 deficiency induces pulmonary hypertension in mice and humans through PKG nitration. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 2009–2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garbers D. L. (1992) Guanylyl cyclase receptors and their endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine ligands. Cell 71, 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feil S., Zimmermann P., Knorn A., Brummer S., Schlossmann J., Hofmann F., Feil R. (2005) Distribution of cGMP-dependent protein kinase type I and its isoforms in the mouse brain and retina. Neuroscience 135, 863–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Uhler M. D. (1993) Cloning and expression of a novel cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase from mouse brain. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 13586–13591 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vaandrager A. B., Hogema B. M., de Jonge H. R. (2005) Molecular properties and biological functions of cGMP-dependent protein kinase II. Front. Biosci. 10, 2150–2164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wolfe L., Corbin J. D. (1989) Cyclic nucleotides and disease. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1, 215–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wolfe L., Corbin J. D., Francis S. H. (1989) Characterization of a novel isozyme of cGMP-dependent protein kinase from bovine aorta. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 7734–7741 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takio K., Wade R. D., Smith S. B., Krebs E. G., Walsh K. A., Titani K. (1984) Guanosine cyclic 3′,5′-phosphate dependent protein kinase, a chimeric protein homologous with two separate protein families. Biochemistry 23, 4207–4218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Atkinson R. A., Saudek V., Huggins J. P., Pelton J. T. (1991) 1H NMR and circular dichroism studies of the N-terminal domain of cyclic GMP dependent protein kinase. A leucine/isoleucine zipper. Biochemistry 30, 9387–9395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhao J., Trewhella J., Corbin J., Francis S., Mitchell R., Brushia R., Walsh D. (1997) Progressive cyclic nucleotide-induced conformational changes in the cGMP-dependent protein kinase studied by small angle x-ray scattering in solution. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 31929–31936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chu D. M., Francis S. H., Thomas J. W., Maksymovitch E. A., Fosler M., Corbin J. D. (1998) Activation by autophosphorylation or cGMP binding produces a similar apparent conformational change in cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 14649–14656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hofmann F., Gensheimer H. P., Göbel C. (1983) Autophosphorylation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase is stimulated only by occupancy of one of the two cGMP binding sites. FEBS Lett. 164, 350–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hofmann F., Gensheimer H. P., Göbel C. (1985) cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Autophosphorylation changes the characteristics of binding site 1. Eur. J. Biochem. 147, 361–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reed R. B., Sandberg M., Jahnsen T., Lohmann S. M., Francis S. H., Corbin J. D. (1996) Fast and slow cyclic nucleotide-dissociation sites in cAMP-dependent protein kinase are transposed in type Ibeta cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 17570–17575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Corbin J. D., Døskeland S. O. (1983) Studies of two different intrachain cGMP-binding sites of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 11391–11397 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reddy V. M., Meyrick B., Wong J., Khoor A., Liddicoat J. R., Hanley F. L., Fineman J. R. (1995) In utero placement of aortopulmonary shunts. A model of postnatal pulmonary hypertension with increased pulmonary blood flow in lambs. Circulation 92, 606–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jonigk D., Golpon H., Bockmeyer C. L., Maegel L., Hoeper M. M., Gottlieb J., Nickel N., Hussein K., Maus U., Lehmann U., Janciauskiene S., Welte T., Haverich A., Rische J., Kreipe H., Laenger F. (2011) Plexiform lesions in pulmonary arterial hypertension composition, architecture, and microenvironment. Am. J. Pathol. 179, 167–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wedgwood S., McMullan D. M., Bekker J. M., Fineman J. R., Black S. M. (2001) Role for endothelin-1-induced superoxide and peroxynitrite production in rebound pulmonary hypertension associated with inhaled nitric oxide therapy. Circ. Res. 89, 357–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sud N., Sharma S., Wiseman D. A., Harmon C., Kumar S., Venema R. C., Fineman J. R., Black S. M. (2007) Nitric oxide and superoxide generation from endothelial NOS. Modulation by HSP90. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 293, L1444–L1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sharma S., Sud N., Wiseman D. A., Carter A. L., Kumar S., Hou Y., Rau T., Wilham J., Harmon C., Oishi P., Fineman J. R., Black S. M. (2008) Altered carnitine homeostasis is associated with decreased mitochondrial function and altered nitric oxide signaling in lambs with pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 294, L46–L56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Venselaar H., Joosten R. P., Vroling B., Baakman C. A., Hekkelman M. L., Krieger E., Vriend G. (2010) Homology modelling and spectroscopy, a never-ending love story. Eur. Biophys. J. 39, 551–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D. J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST. A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. King R. D., Sternberg M. J. (1996) Identification and application of the concepts important for accurate and reliable protein secondary structure prediction. Protein Sci. 5, 2298–2310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kawashima S., Yamashita T., Ozaki M., Ohashi Y., Azumi H., Inoue N., Hirata K., Hayashi Y., Itoh H., Yokoyama M. (2001) Endothelial NO synthase overexpression inhibits lesion formation in mouse model of vascular remodeling. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 21, 201–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rudic R. D., Shesely E. G., Maeda N., Smithies O., Segal S. S., Sessa W. C. (1998) Direct evidence for the importance of endothelium-derived nitric oxide in vascular remodeling. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 731–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pilz R. B., Broderick K. E. (2005) Role of cyclic GMP in gene regulation. Front. Biosci. 10, 1239–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Casteel D. E., Smith-Nguyen E. V., Sankaran B., Roh S. H., Pilz R. B., Kim C. (2010) A crystal structure of the cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase Iβ dimerization/docking domain reveals molecular details of isoform-specific anchoring. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 32684–32688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Osborne B. W., Wu J., McFarland C. J., Nickl C. K., Sankaran B., Casteel D. E., Woods V. L., Jr., Kornev A. P., Taylor S. S., Dostmann W. R. (2011) Crystal structure of cGMP-dependent protein kinase reveals novel site of interchain communication. Structure 19, 1317–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim J. J., Casteel D. E., Huang G., Kwon T. H., Ren R. K., Zwart P., Headd J. J., Brown N. G., Chow D. C., Palzkill T., Kim C. (2011) Co-crystal structures of PKG Iβ (92–227) with cGMP and cAMP reveal the molecular details of cyclic-nucleotide binding. PLoS One 6, e18413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Herranz B., Marquez S., Guijarro B., Aracil E., Aicart-Ramos C., Rodriguez-Crespo I., Serrano I., Rodríguez-Puyol M., Zaragoza C., Saura M. (2012) Integrin-linked kinase regulates vasomotor function by preventing endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling. Role in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 110, 439–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lincoln T. M., Dey N. B., Boerth N. J., Cornwell T. L., Soff G. A. (1998) Nitric oxide-cyclic GMP pathway regulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation. Implications in vascular diseases. Acta. Physiol. Scand. 164, 507–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Acampora K. B., Nagatomi J., Langan E. M., 3rd, LaBerge M. (2010) Increased synthetic phenotype behavior of smooth muscle cells in response to in vitro balloon angioplasty injury model. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 24, 116–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Negash S., Narasimhan S. R., Zhou W., Liu J., Wei F. L., Tian J., Raj J. U. (2009) Role of cGMP-dependent protein kinase in regulation of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell adhesion and migration. Effect of hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297, H304–H312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dusserre E., Bourdillon M. C., Pulcini T., Berthezene F. (1994) Decrease in high density lipoprotein binding sites is associated with decrease in intracellular cholesterol efflux in dedifferentiated aortic smooth muscle cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1212, 235–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klemm D. J., Majka S. M., Crossno J. T., Jr., Psilas J. C., Reusch J. E., Garat C. V. (2011) Reduction of reactive oxygen species prevents hypoxia-induced CREB depletion in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 58, 181–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Madamanchi N. R., Moon S. K., Hakim Z. S., Clark S., Mehrizi A., Patterson C., Runge M. S. (2005) Differential activation of mitogenic signaling pathways in aortic smooth muscle cells deficient in superoxide dismutase isoforms. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 950–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang J. N., Shi N., Chen S. Y. (2012) Manganese superoxide dismutase inhibits neointima formation through attenuation of migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 52, 173–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nisbet R. E., Graves A. S., Kleinhenz D. J., Rupnow H. L., Reed A. L., Fan T. H., Mitchell P. O., Sutliff R. L., Hart C. M. (2009) The role of NADPH oxidase in chronic intermittent hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 40, 601–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Broughton B. R., Jernigan N. L., Norton C. E., Walker B. R., Resta T. C. (2010) Chronic hypoxia augments depolarization-induced Ca2+ sensitization in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle through superoxide-dependent stimulation of RhoA. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 298, L232–L242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nozik-Grayck E., Stenmark K. R. (2007) Role of reactive oxygen species in chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 618, 101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cruz J. A., Bauer E. M., Rodriguez A. I., Gangopadhyay A., Zeineh N. S., Wang Y., Shiva S., Champion H. C., Bauer P. M. (2012) Chronic hypoxia induces right heart failure in caveolin-1−/− mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 302, H2518–H2527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ischiropoulos H. (2003) Biological selectivity and functional aspects of protein tyrosine nitration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 305, 776–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Corbin J. D., Ogreid D., Miller J. P., Suva R. H., Jastorff B., Døskeland S. O. (1986) Studies of cGMP analog specificity and function of the two intrasubunit binding sites of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 1208–1214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Redondo-Horcajo M., Romero N., Martínez-Acedo P., Martínez-Ruiz A., Quijano C., Lourenço C. F., Movilla N., Enríquez J. A., Rodríguez-Pascual F., Rial E., Radi R., Vázquez J., Lamas S. (2010) Cyclosporine A-induced nitration of tyrosine 34 MnSOD in endothelial cells. Role of mitochondrial superoxide. Cardiovasc. Res. 87, 356–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Savvides S. N., Scheiwein M., Bohme C. C., Arteel G. E., Karplus P. A., Becker K., Schirmer R. H. (2002) Crystal structure of the antioxidant enzyme glutathione reductase inactivated by peroxynitrite. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 2779–2784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nie H., Wu J. L., Zhang M., Xu J., Zou M. H. (2006) Endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent tyrosine nitration of prostacyclin synthase in diabetes in vivo. Diabetes 55, 3133–3141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Francis S. H., Smith J. A., Colbran J. L., Grimes K., Walsh K. A., Kumar S., Corbin J. D. (1996) Arginine 75 in the pseudosubstrate sequence of type Iβ cGMP-dependent protein kinase is critical for autoinhibition, although autophosphorylated serine 63 is outside this sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20748–20755 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Heil W. G., Landgraf W., Hofmann F. (1987) A catalytically active fragment of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Occupation of its cGMP-binding sites does not affect its phosphotransferase activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 168, 117–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chu D. M., Corbin J. D., Grimes K. A., Francis S. H. (1997) Activation by cyclic GMP binding causes an apparent conformational change in cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 31922–31928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Smith J. A., Francis S. H., Walsh K. A., Kumar S., Corbin J. D. (1996) Autophosphorylation of type Iβ cGMP-dependent protein kinase increases basal catalytic activity and enhances allosteric activation by cGMP or cAMP. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20756–20762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hofmann F., Bernhard D., Lukowski R., Weinmeister P. (2009) cGMP regulated protein kinases (cGK). Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2009, 137–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Busch J. L., Bessay E. P., Francis S. H., Corbin J. D. (2002) A conserved serine juxtaposed to the pseudosubstrate site of type I cGMP-dependent protein kinase contributes strongly to autoinhibition and lower cGMP affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34048–34054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Aitken A., Hemmings B. A., Hofmann F. (1984) Identification of the residues on cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase that are autophosphorylated in the presence of cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 790, 219–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]