Abstract

The type IV secretion system (T4SS) is used by Gram-negative bacteria to translocate protein and DNA substrates across the cell envelope and into target cells. Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri contains two copies of the T4SS, one in the chromosome and the other is plasmid-encoded. To understand the conditions that induce expression of the T4SS in Xcc, we analyzed, in vitro and in planta, the expression of 18 ORFs from the T4SS and 7 hypothetical flanking genes by RT-qPCR. As a positive control, we also evaluated the expression of 29 ORFs from the type III secretion system (T3SS), since these genes are known to be expressed during plant infection condition, but not necessarily in standard culture medium. From the 29 T3SS genes analyzed by qPCR, only hrpA was downregulated at 72 h after inoculation. All genes associated with the T4SS were downregulated on Citrus leaves 72 h after inoculation. Our results showed that unlike the T3SS, the T4SS is not induced during the infection process.

1. Introduction

Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri (Xcc) is a Gram-negative plant pathogenic bacteria that causes severe disease in many economically important citrus plants [1]. The citrus canker induced by Xcc is a destructive disease characterized by canker lesions on leaves, stems, and fruits; furthermore the pathogen induces defoliation, which results in reduced yield and premature fruit drop [2]. Control is difficult in areas where the disease is already established, and plant eradication is the only effective way to control and prevent the disease spread. Recurrent and severe attacks of the pathogen are responsible for serious economic losses in citrus groves around the world [2].

The focus of the present study is aimed at understanding the role of bacterial secretory systems, specifically the type IV secretory system (T4SS). Seven secretory systems are known and described in prokaryotic organisms, and each one is related to a physiological process [3–5]. Of these, the best studied is the type III secretory system (T3SS), which enables bacterial pathogens to deliver effector proteins into eukaryotic cells [6]. Some bacterial pathogens, including species from Chlamydia, Xanthomonas, Pseudomonas, Ralstonia, Shigella, Salmonella, Escherichia, and Yersinia, depend on the T3SS to induce damage to the host. In contrast, other organisms including Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Helicobacter pylori, and Legionella pneumophila depend on the type IV secretory system (T4SS) for virulence induction [7].

The T3SS contains at least twenty distinct proteins, which are subdivided into three parts. The basal body of the system [8–11] is associated with an ATPase and likely facilitates the entry of substrates into the secretion apparatus [12]. This basal body is also associated with a protein needle (the second part of the T3SS), which binds the bacterium to host cells and acts as a conduit for effectors secretion. The third part of the T3SS is composed of three proteins that are exported through the bacterial needle and form a pore on the surface of the host cell, which facilitates the export of toxins into the target cytoplasm [13].

On the other hand, the T4SS is a multiprotein complex that consists of a protein channel (encoded by virB and virD) through which proteins or protein-DNA complexes can be translocated between bacteria (cell-to-cell communication) and into host cells [14]. Translocation is driven by a number of cytoplasmic ATPases that potentially energize large conformational changes in the translocation complex [15]. There are three functional types of T4SS. The first type, found in many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and some Archaea, functions in conjugation and in the transfer of T-DNA into plant cells by A. tumefaciens. A second type of T4SS mediates DNA uptake in the transformation process (found in H. pylori). A third type of T4SS is used to transfer toxic effector proteins or protein complexes into the cytoplasm of host cells (found in Bordetella pertussis, Legionella pneumophila, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Xcc) [15].

Substrates transported by the T4SS modulate various cellular processes including apoptosis, vesicular traffic, and ubiquitination; furthermore, the number of type IV effector proteins continues to increase [16–19]. However, most of these substrates have not been functionally characterized, and their role in bacterial pathogenesis remains unknown [20].

In many bacteria, these two secretory systems types are well characterized; however, in Xanthomonas spp. only the T3SS has been intensively studied [1], in contrast to the limited number of studies involving the T4SS [21, 22]. In Xcc the T4SS deserves more attention, especially since the genome contains two copies of this system (chromosomal and plasmid-borne) [23]. The plasmid copy is homologous to others Xanthomonads that contain the T4SS on extrachromosomal DNA. However, only Xcc and Xanthomonas campestris contain the chromosomal copy of the T4SS.

To understand the conditions that stimulate expression of T4SS genes in Xcc we used qPCR to analyze the in vitro and in planta expression of 18 ORFs from the T4SS (both chromosomal and plasmid copies) and 7 hypothetical ORFs flanking the T4SS. To validate the qPCR data, we compared expression of 29 ORFs from the T3SS, which are known to be expressed in planta.

Our results showed that the T4SS is not induced during the infection process in Xcc, but may be very important in cell-to-cell communication.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbiological Procedures

Xcc strain 306 was previously sequenced by da Silva et al. [23]. Xcc was maintained in sterile tap water and grown on nutrient agar (NA) medium containing 3 g beef extract, 5 g peptone, and 15 g agar in 1 L of distilled water at 28°C. After 24 h, three single colonies were transferred to new NA plates and incubated for 12 h at 28°C. These Xcc solid cultures were used as pre-inoculum for in planta and in vitro studies. For in planta studies, pre-inoculum cultures were aseptically transferred to sterile flasks containing 50 mL of nutrient broth (NB) and the bacterial concentration was adjusted to 108 CFU/mL (OD600 = 0.3). This bacterial suspension was taken up in a 1 mL needleless syringe and used to infiltrate orange leaves (Citrus sinensis cv. pera) grown in 20 L capacity pots. A total of nine plants were inoculated (20 leaves per plant) and maintained for 72 h in a growth room at 28°C, with a 12 h photoperiod and light intensity ~2,000 lux. Three plants were used for each incubation period. After multiplication, inoculated leaves were collected, sliced into thin strips with a razor blade, and placed in a beakers with sterile distilled water in an ice bath with gentle agitation. Samples from each plant were placed in separate beakers for bacterial exudation. After 5 min, leaf debris was removed by filtration through gauze, and bacterial cells were recovered by centrifugation at 5,000 ×g for 5 min at 4°C. Total RNA was extracted immediately, as described below. For in vitro studies, 1 mL of each Xcc suspension at 108 CFU/mL were aseptically transferred to three Erlenmeyer flasks and incubated for 12 h at 28°C with shaking (200 rpm). After incubation, bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 ×g for 5 min. Total RNA was extracted as described below. Thus, we obtained three independent biological replicates for Xcc growth in vitro and in planta. All cultivation media were obtained from Difco Chemical Co., Detroit, USA. For confirmatory RT-qPCR, the same procedures were followed except the plant incubation period was only 72 h, due to RNA quality and concentration sufficient to yield reliable results. The time point 72 hours was the shortest period to allow obtaining satisfactory bacterial mass to the proposed analyzes involving gene expression. The bacterial cells concentration in short time (12 or 24 hours) don't allows this study. For this reason, some works are using culture media that mimic vegetable conditions to investigate the infectious process under these time scales [24, 25].

2.2. Extraction of RNA from Xcc

Each inoculated flask represented one independent biological replicate. RNA was extracted using an Illustra-RNAspin Mini RNA Isolation Kit (Amersham Biosciences) following the manufacturer's instructions. To ensure that samples did not contain DNA, PCR was performed using RNA samples treated with DNase I as a template. PCR conditions consisted of an initial denaturing step of 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of a denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and elongation at 72°C for 2 min. A final elongation step of 72°C for 4 min was performed, and then samples were maintained at 4°C until needed. The amplification reaction was conducted in a total volume of 25 μL containing 200 ng RNA in 2.5 μL, PCR buffer (2.5 μL, Invitrogen), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTP, 300 nM 16S rRNA primer [26], and 1 U Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). The products were electrophoresed in a 1% agarose gel with TAE buffer, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized using a UV transilluminator. No products were observed (data not shown). To verify the quality of extracted RNA, the samples were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel using TAE buffer followed by ethidium bromide staining. The A260/280 ratio of RNA samples was measured, and RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). RNA samples were stored at −80°C until needed.

2.3. Gene Expression Using RT-qPCR

First strand cDNA synthesis and all RT-qPCR reactions were done using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix for RT-qPCR (Invitrogen) as recommended by the manufacturer's specifications except for the amount of cDNA in each reaction, which was 20 ng. All PCR was performed with SYBR Green on a 7500 Real-Time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems) using three biological replicates and three technical replicates (one for each biological replicate). PCR was for 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, and 1 min at 60°C. To determine PCR efficiency, standard curves were generated using cDNA samples at five dilutions and measured in triplicate. rpoB, atpD, and gyrB were used as reference genes in all experiments [26]. To perform relative expression analysis, we used the 2−ΔΔ CT method [27]. Primer features are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

General features of the T3SS and T4SS primer sequences.

| XAC ID | Gene | Gene ID | Product (NCBI Annotation) | Primers (Forward) | Primers (Reverse) | Amplicon (bp) | System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XAC0293 | hrpB | 1154364 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase | GCCGTATCCCGTTGACCTT | ACCGCCCCTTCATCTCTTTT | 81 | T3SS |

| XAC0393 | hpaF | 1154464 | HpaF protein | GGCGAGCGTTTTGACAA | CCGGAGATCCTGGCAGTTT | 57 | T3SS |

| XAC0394 | hrpF | 1154465 | HrpF protein | GCCGCGACGCAGTTG | CGGTGATCGAGTTGTTCAA | 62 | T3SS |

| XAC0396 | hpaB | 1154467 | HpaB protein | GTCCGTGTACGCGCAAGAC | TGACGCCGGCATCATTG | 53 | T3SS |

| XAC0397 | hrpE | 1154468 | HrpE protein | ACGAGGCCCAGAAGTCCAT | CCACGTTGAAGTCCAGATCATTT | 66 | T3SS |

| XAC0398 | hrpD6 | 1154469 | HrpD6 protein | ACCGATACGGTCACCCAAGA | GATCCGCCGCCTTGGT | 55 | T3SS |

| XAC0399 | hrpD5 | 1154470 | HrpD5 protein | GCCCTGAAGTGCGTTCGTTA | TCACGGACGGGTCTTGCT | 54 | T3SS |

| XAC0400 | hpaA | 1154471 | HpaA protein | CGCCACCCCAACAGAAAA | ACGGCATCAGCTCCATCAA | 59 | T3SS |

| XAC0401 | hrcS | 1154472 | HrcS protein | CGACGATCTAGTGCGATTTACCT | CGACCACCGGCAAGGA | 68 | T3SS |

| XAC0402 | hrcR | 1154473 | Protein T3SS | ACACGGGAACGCGAAAAA | CCTTGGGCCAGATCTGTTGT | 58 | T3SS |

| XAC0403 | hrcQ | 1154474 | HrcQ protein | GCAGCTGGAAGTGGACCAA | GGCTGCAAACCCGACAAC | 57 | T3SS |

| XAC0404 | hpaP | 1154475 | HpaP protein | TGTCGATGGCACGAAATACC | CCCAACCGCGCCATT | 58 | T3SS |

| XAC0405 | hrcV | 1154476 | HrcV protein | GCCGCAAGTTGGTCGAGTT | CTCTGCCATATCGCGATTCC | 58 | T3SS |

| XAC0406 | hrcU | 1154477 | HrcU protein T3SS | AGCCGCGGTGCTCTTTG | TAGTCGCCGGCCGATTT | 51 | T3SS |

| XAC0407 | hrpB1 | 1154478 | HrpB1 protein | CTGCGGCCAGAGCTGAAG | ACCGCGCTTGATGGAAATC | 60 | T3SS |

| XAC0408 | hrpB2 | 1154479 | HrpB2 protein | CAGCGCAGCAGATCAAGTTG | CGCCGACGCTGACATTG | 69 | T3SS |

| XAC0409 | hrcJ | 1154480 | HrcJ protein | GAGCGGCACGCCAATC | TGTCGAGATCAAGCCATCCTT | 54 | T3SS |

| XAC0410 | hrpB4 | 1154481 | HrpB4 protein | GGACAACACGCGGATCGA | GTCCGTCCAGCGCTGAA | 52 | T3SS |

| XAC0411 | hrpB5 | 1154482 | Protein T3SS HrpB | CGCACGCCTGGGATATG | AGGCCGGATTCGTTCCA | 63 | T3SS |

| XAC0412 | hrcN | 1154483 | T3SS ATPase protein | TCGATGGGCACCTGATTCTC | CGTCGATTGCCGGGTACT | 63 | T3SS |

| XAC0413 | hrpB7 | 1154484 | HrpB7 protein | CCGCGCTGATGGACAAG | GCTGCAGGATCGTGTCGATA | 60 | T3SS |

| XAC0414 | hrcT | 1154485 | HrcT protein | ATCCAGCAATCCGACAGCAT | CACCGGTGCGGACAGTTT | 54 | T3SS |

| XAC0415 | hrcC | 1154486 | HrcC protein | CAGATGCGGCTGGATGTG | CCGTCCACGGTGTTGGAT | 59 | T3SS |

| XAC0416 | hpa1 | 1154487 | Hpa1 protein | GCAGCAGGCCGGTCAGT | TTCATCAGCATCTGGGTGTATTG | 57 | T3SS |

| XAC0459 | phaE | 1154530 | monovalent cation/H + antiporter subunit E | CCATCCCGGCTTCATCTG | GCGATGCCGTGAATGTTG | 54 | T3SS |

| XAC0618 | hrpM | 1154689 | Glucosyltransferase MdoH | CAAGGGCCTGCACTGGAT | GCATCAACAGACCCCACATC | 86 | T3SS |

| XAC1265 | hrpG | 1155336 | HrpG protein | CGGCAAGCCGATCGTATT | GAAAAGAGCAGCCAGGCAAT | 54 | T3SS |

| XAC1266 | hrpXct | 1155337 | HrpX protein | GCCTACAGCTACATGATCACCAAT | TGCGGCCACTTCGTTGA | 63 | T3SS |

| XAC1520 | hrcA | 1155591 | Heat-inducible transcriptional repressor | AGTTCGCGTTTCGGCATATC | CGGTTCTGCACCTCGTTGT | 91 | T3SS |

| XAC1994 | hrpX | 1156064 | HrpX-like protein | CTGGTCTGATGCGAGCTTTCT | GCGTACTCGTCCACGATCAA | 90 | T3SS |

| XAC2047 | phaE | 1156118 | PHA synthase subunit | AGCAGGGTGCATCGAAGAAG | TTTTCGGAGCCGCCTTTT | 63 | T3SS |

| XAC2606 | — | 1156677 | Hypothetical protein | CCCTCAGTGTGGGCCAGAT | AGGAGGCGGTTGAGGGATA | 58 | H_T4SS_C |

| XAC2611 | — | 1156682 | Hypothetical protein | GGGAGCCCGCAATGTG | GGAGGCGTGGGAATATCATCT | 59 | H_T4SS_C |

| XAC2612 | virB6 | 1156683 | VirB6 protein | TGCAGCAGGGAGGATTAGGA | CGGCGGTGCGGTGAT | 56 | T4SS_C |

| XAC2613 | — | 1156684 | Hypothetical protein | CGAAGGGAGATGGAAGCAGTT | GCTCAACAGATCGGCTGGAA | 59 | H_T4SS_C |

| XAC2614 | virB4 | 1156685 | VirB4 protein | GACGTCGCTTGGTGGAGAAA | TTCCTCGGCGCGAATCT | 53 | T4SS_C |

| XAC2615 | virB3 | 1156686 | VirB3 protein | GCCCCGCCATGTTTTTG | CGCCCGCACCAATGAA | 54 | T4SS_C |

| XAC2616 | virB2 | 1156687 | VirB2 protein | TCGCCGATGCCAAAATG | CAGCAACGAAATGAATAGCAATG | 62 | T4SS_C |

| XAC2617 | virB1 | 1156688 | VirB1 protein | CGTATCGAGTCGTCGCGTAAT | CACCAGGCGTCCACCAA | 57 | T4SS_C |

| XAC2618 | virB11 | 1156689 | VirB11 protein | CGCTGGTCAACCACATTCC | CCTGGCGTCCTCAATCGT | 56 | T4SS_C |

| XAC2619 | virB10 | 1156690 | VirB10 protein | CCATTGCAGCTCTCTTGATTCTC | GAATCCTCCCCGCTTTGC | 61 | T4SS_C |

| XAC2620 | virB9 | 1156691 | VirB9 protein | GCTGAGCCCGAACGAAAAA | GCTCCCATCCACCAGTGAA | 59 | T4SS_C |

| XAC2621 | virB8 | 1156692 | VirB8 protein | TCGTCATGGCAGATGCGTAT | CCGAAGTTGGGCTCAAGCT | 61 | T4SS_C |

| XAC2622 | — | 1156693 | Hypothetical protein | GGCGGATTCCAATATGCAGTT | TGGCCCGATCAAGGTGTAG | 59 | H_T4SS_C |

| XAC2623 | virD4 | 1156694 | VirD4 protein | TCGCTGGAATCCATTGACCTA | TCAAATCCGAAACGCGAAAT | 59 | T4SS_C |

| XAC2922 | hrpW | 1156993 | HrpW protein | GGCGGACACACCGACATC | TGCCTTTCAGGGTGGAGTCTT | 58 | T3SS |

| XAC3122 | hrpA | 1157193 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase | TGCGCGCTCTGAATTCG | GGACTGGGTAAGATCTTCATGCA | 76 | T3SS |

| XACb0035 | — | 1158522 | Hypothetical protein | CGAGACGAGAACGGCCATT | TGTCACGCAGCAATTCGAA | 55 | H_T4SS_P |

| XACb0036 | virB1 | 1158523 | VirB1 protein | CGTTACAACCTCGCCAAATATG | CTGCCCGCCTTGAGATTG | 74 | T4SS_P |

| XACb0037 | virB11 | 1158524 | VirB11 protein | CCCGGAAGCGGTTGAGT | CGTGAGCGACCCCTTGTG | 58 | T4SS_P |

| XACb0038 | virB10 | 1158525 | VirB10 protein | TCTACGTGAACAAAGACCTCGATT | CGCTTGGCTCCGTCGAT | 64 | T4SS_P |

| XACb0039 | virB9 | 1158526 | VirB9 protein | GCTCACGCGGCGAAGTT | GCACTTGCTTGACACGATCATC | 58 | T4SS_P |

| XACb0040 | virB8 | 1158527 | VirB8 protein | CTCGAACAAGCTCAAACAGGAA | AACAGCAGCAACCCGATGA | 60 | T4SS_P |

| XACb0041 | virB6 | 1158528 | VirB6 protein | GCGCAGCTCGTCATCGT | CGCGGACACCCAACATG | 55 | T4SS_P |

| XACb0042 | — | 1158529 | Hypothetical protein | CCGGGAACCCGCTTTTA | GGAAGCCACTGCCGAAACT | 52 | H_T4SS_P |

| XACb0043 | — | 1158530 | Hypothetical protein | TTCGCGGCCCTCATCTC | AGGGCGACTTGTTGAACTTGTT | 58 | H_T4SS_P |

| XACb0044 | virB5 | 1158531 | VirB5 protein | CAGGCCGCCTACGAGAAG | GGGATTGGCGAACAGGTCTT | 57 | T4SS_P |

| XACb0045 | virB4 | 1158532 | VirB4 protein | GGAACAGGCAAAAGACGTCAAC | CCCGACAAGGTTTGAACGA | 57 | T4SS_P |

| XACb0046 | virB3 | 1158533 | VirB3 protein | TCTTGCGATGAGCTTTTATTTCC | CCCAAAGTGATCGCGTGATT | 59 | T4SS_P |

| XACb0047 | virB2 | 1158534 | VirB2 protein | CGATCTGGCGGCTAACGT | ATGCGAGCTGCGGAAGAA | 56 | T4SS_P |

| XACb0048 | — | 1158535 | Hypothetical protein | GGCGGATGACGTTGAAGCT | CGCGGTAACGACCTCATAAAC | 56 | H_T4SS_P |

| XACb0049 | — | 1158536 | Hypothetical protein | ACCACGGATCCTGGCAAAT | AGCAGCCCCCGTGAACA | 51 | H_T4SS_P |

This table provides primers sequences, ORF's identification ID, gene's name, and respective Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri secretory systems. T4SS: type IV secretion system; T3SS: type III secretion system; C: chromosomal copy; P: plasmid copy; H: hypothetical genes associated with the T4SS.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. qPCR Results for the T3SS

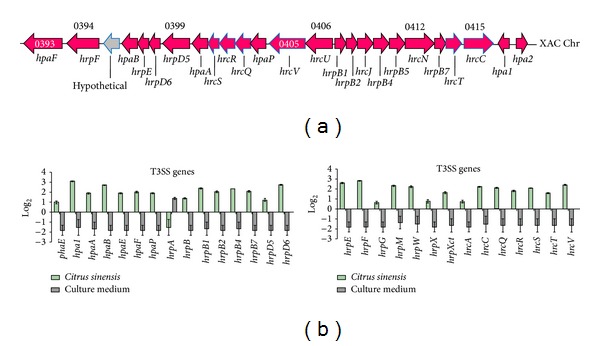

The results obtained from Xcc growing in planta or in vitro are presented in Figure 1. From the 29 T3SS genes analyzed by qPCR, only hrpA was downregulated at 72 h after inoculation (Figure 1(b)). hpa1, hpaB, hrpD6, hrpE, and hrpF showed the highest rates of expression, whereas phaE, hrpG, hrpX, and hrcA showed the lowest levels of expression. Interestingly, hrpB4 and hrpXct, which were shown to be necessary for Xcc pathogenesis [28], were not among the most upregulated genes in this study.

Figure 1.

T3SS genes in Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri and their expression levels. Schematic representation of T3SS genes in Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri and their expression levels. (a) shows functional maps of T3SS genes on the chromosome. The expression levels of genes in the T3SS (b) are indicated. Solid green bars indicate in vivo expression with respect to their expression in vitro (black bars). Error bars indicate standard deviation of the replicates.

3.2. qPCR Results for the T4SS

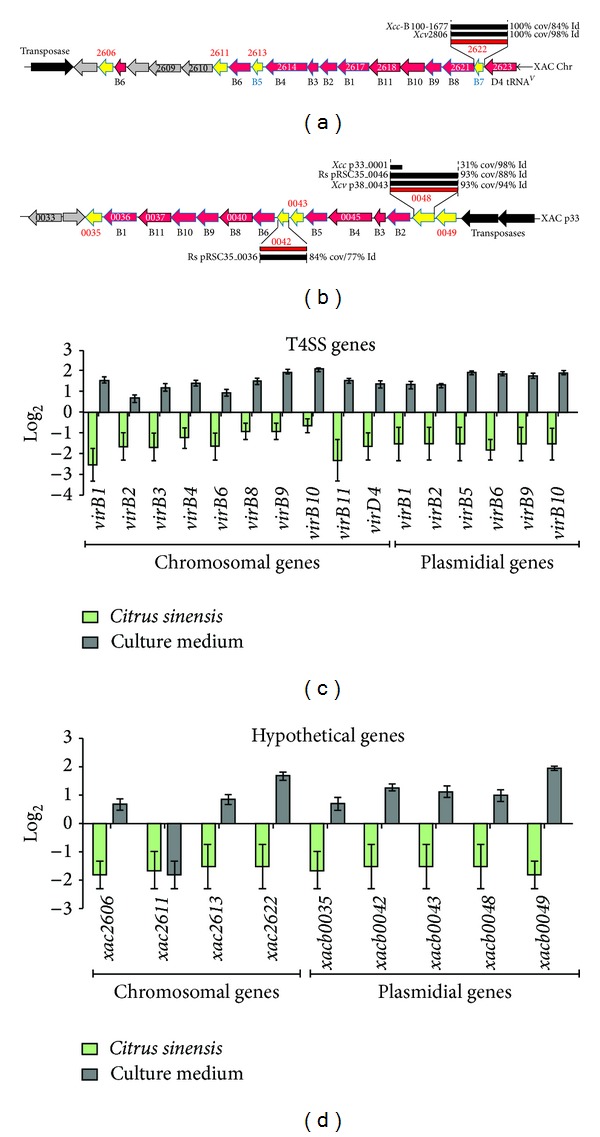

The results for the expression levels of T4SS genes in planta and in vitro are shown in Figure 2. All genes associated with the T4SS were downregulated on Citrus leaves 72 h after inoculation (Figure 2(c)). We also analyzed the expression of hypothetical genes located near virB in chromosomal DNA (XAC2606, XAC2611, XAC2613, and XAC2622) and in plasmid pXAC64 (XACb0035, XACb0042, XACb0043, XACb0048, and XACb0049) (Figure 2(d) and Table 1). ORFs representing hypothetical genes in both the chromosome and plasmid were down-regulated when Xcc was cultivated in Citrus sinensis for 72 h. An exception was XAC2611, where expression was similar when Xcc was cultivated in culture medium or in planta (Figure 2(d)).

Figure 2.

T4SS genes in Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri and their expression levels. Schematic representation of T4SS genes in Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri and their expression levels. (a) and (b) show functional maps of T4SS genes on the chromosome (a) and plasmid pXAC64 (b), respectively. The expression levels of genes in the T4SS (c) and ORFs localized near the virB genes (d) are indicated. Solid green bars indicate in vivo expression with respect to their expression in vitro (black bars). Error bars indicate standard deviation of the replicates.

Our results clearly show different gene expression profiles for the T3SS and T4SS in Xcc during Citrus infection. The T4SS was previously described in A. tumefaciens, where it mediates the transfer of DNA and protein substrates to plants and other organisms via a cell contact-dependent mechanism [14]. In Xcc, the genome sequence revealed the presence of two virB operons, one on the chromosome and a second copy in the 64 kb plasmid pXAC64 [23]. The chromosomal genes virB1, virB3, virB4, virB8, virB9, and virB11 and the plasmid-encoded genes virB1, virB2, virB4, virB6, virB9, and virB11 were all down-regulated in planta (Figure 2(c)). This was somewhat surprising because the T4SS is essential for a successful infection in many Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria [29]. The fact that ORFs representing hypothetical genes in both the chromosome and plasmid near the virB genes were also down-regulated under the same condition (Figure 2(d)) indicates that they could be related to the T4SS system in Xcc. Recent studies in Brucella suis [30] and in A. tumefaciens [31] showed that alterations in VirB8 result in protein dimerization, a process that modifies the T4SS structure and affects bacterial virulence. In Streptococcus suis [32], the knockout of the virD4-89K and virB4-89K of the T4SS eliminated the lethality of a highly virulent strain and impaired its ability to trigger host immune responses in mice. Recent studies continue to demonstrate the importance of the T4SS and its components in virulence; thus the lack of induction of Xcc T4SS genes in the present study is intriguing. However, in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris T4SS-deletion mutant displayed the same virulence as wild type and authors conclude that T4SS is not involved in pathogenicity in that Xanthomonas [33].

Wang et al. [34] presented evidence that in planta transfer of a 37 kb plasmid (pXcB) from Xanthomonas aurantifolii to Xanthomonas citri can occur via T4SS. Thus, at least the T4SS copy present in Xcc plasmid can play a hole in horizontal gene transfer.

All but one of the twenty-nine genes from the T3SS of Xcc were up-regulated in planta. Laia et al. [28] showed that Xcc mutants containing mutations in hrpB4 or hrpXct failed to cause disease and growth in citrus leaves was lower than the wild-type Xcc strain 306. These two genes, which are not among the most up-regulated genes in the present study, are part of the hrp (hypersensitive reaction and pathogenicity) system and comprise part of the T3SS [35]. In the related pathogen, Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria (Xcv), a hrpB4 mutant was unable to cause disease in susceptible pepper plants or the hypersensitive reaction in pepper plants carrying the respective compatible R gene [36]. Previously, hrpXv was shown to be necessary for transcriptional activation of five hrp genes (loci hrpB to hrpF) [37], and hrpB4 was required for complete functionality of the T3SS in Xcv [36]. Thus it is apparent that a gene does not have to be strongly up-regulated during infection to play an important role in virulence. Multiple genes, including hpaA, hpaE, hpaF, hpaP, hrpB, hrpB1, hrpB2, hrpB7, hrpD5, hrpM, hrpW, hrcC, hrcQ, hrcS, hrcT, and hrcV, were expressed at levels similar to hrpXct and hrpB4 and are good candidates for further studies into their roles in citrus canker disease.

Among the most up-regulated genes, hrpD6 warrants further attention. A hrpD6 mutant of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) failed to trigger a hypersensitive response in tobacco and was nonpathogenic in rice because the mutation in hrpD6 impacts the secretion of T3SS effectors, such as Hpa1, which is translocated through the T3SS [38]. Our qPCR data showed that hpa1 was the most up-regulated gene during Citrus sinensis infection by Xcc, followed by hrpD6 (Figure 1(b)). Conversely, hrpA, which encodes an important component of the T3SS pilus [39], was down-regulated in our study. Previously, hrpA mutants of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 showed reduced accumulation of structural components of the hrp pilus [39]. Haapalainen et al. [40] showed that soluble plant cell signals induce the expression of hrp/hrc genes and specifically upregulate hrpA. Interestingly, they found that HrpA does not accumulate to high levels intracellularly, suggesting that some kind of feedback regulation takes place between secretion and production of HrpA, perhaps through degradation of intracellular HrpA. Our work shows that this may also be applicable to hrpA gene in Xcc: its mRNA may be degraded faster, just as happen with HrpA in Pseudomonas syringae.

4. Conclusions

Our finds confirm that the T3SS genes are induced in the successful infection of Citrus sinensis by Xcc, and therefore are excellent targets to help control or decrease the severity of citrus canker, whereas T4SS seems not have any relation with virulence. On the other hand, our results show that T4SS is not induced under the same infection conditions, which could indicate that it is not necessary for infection but only for cell-to-cell communication.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), Fundo de Defesa da Citricultura (FUNDECITRUS), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the biological tests and fellowship Grants, and by Grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (CBB-APQ-04425-10) for Xcc functional database creation. The funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the paper.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Boch J, Bonas U. Xanthomonas AvrBs3 family-type III effectors: discovery and function. Annual Review of Phytopathology. 2010;48:419–436. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham JH, Gottwald TR, Cubero J, Achor DS. Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri: factors affecting successful eradication of citrus canker. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2004;5(1):1–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2004.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bitter W, Houben ENG, Luirink J, Appelmelk BJ. Type VII secretion in mycobacteria: classification in line with cell envelope structure. Trends in Microbiology. 2009;17(8):337–338. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Büttner D, Bonas U. Regulation and secretion of Xanthomonas virulence factors. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2010;34(2):107–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoop EJM, Bitter W, van der Sar AM. Tubercle bacilli rely on a type VII army for pathogenicity. Trends in Microbiology. 2012;20(10):477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troisfontaines P, Cornelis GR. Type III secretion: more systems than you think. Physiology. 2005;20(5):326–339. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00011.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coburn B, Sekirov I, Finlay BB. Type III secretion systems and disease. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2007;20(4):535–549. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00013-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodgkinson JL, Horsley A, Stabat D, et al. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the Shigella T3SS transmembrane regions reveals 12-fold symmetry and novel features throughout. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2009;16(5):477–485. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moraes TF, Spreter T, Strynadka NC. Piecing together the Type III injectisome of bacterial pathogens. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2008;18(2):258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schraidt O, Lefebre MD, Brunner MJ, et al. Topology and organization of the Salmonella typhimurium type III secretion needle complex components. PLoS Pathogens. 2010;6(4, article e1000824) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spreter T, Yip CK, Sanowar S, et al. A conserved structural motif mediates formation of the periplasmic rings in the type III secretion system. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2009;16(5):468–476. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akeda Y, Galán JE. Chaperone release and unfolding of substrates in type III secretion. Nature. 2005;437(7060):911–915. doi: 10.1038/nature03992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matteï P-J, Faudry E, Job V, Izoré T, Attree I, Dessen A. Membrane targeting and pore formation by the type III secretion system translocon. FEBS Journal. 2011;278(3):414–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christie PJ, Atmakuri K, Krishnamoorthy V, Jakubowski S, Cascales E. Biogenesis, architecture, and function of bacterial type IV secretion systems. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2005;59:451–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallden K, Rivera-Calzada A, Waksman G. Type IV secretion systems: versatility and diversity in function. Cellular Microbiology. 2010;12(9):1203–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Felipe KS, Pampou S, Jovanovic OS, et al. Evidence for acquisition of Legionella type IV secretion substrates via interdomain horizontal gene transfer. Journal of Bacteriology. 2005;187(22):7716–7726. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.22.7716-7726.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagai H, Kagan JC, Zhu X, Kahn RA, Roy CR. A bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factor activates ARF on Legionella phagosomes. Science. 2002;295(5555):679–682. doi: 10.1126/science.1067025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ninio S, Roy CR. Effector proteins translocated by Legionella pneumophila: strength in numbers. Trends in Microbiology. 2007;15(8):372–380. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan X, Lührmann A, Satoh A, Laskowski-Arce MA, Roy CR. Ankyrin repeat proteins comprise a diverse family of bacterial type IV effectors. Science. 2008;320(5883):1651–1654. doi: 10.1126/science.1158160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchesini MI, Herrmann CK, Salcedo SP, Gorvel J-P, Comerci DJ. In search of Brucella abortus type iv secretion substrates: screening and identification of four proteins translocated into host cells through virb system. Cellular Microbiology. 2011;13(8):1261–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alegria MC, Souza DP, Andrade MO, et al. Identification of new protein-protein interactions involving the products of the chromosome- and plasmid-encoded type IV secretion loci of the phytopathogen Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri. Journal of Bacteriology. 2005;187(7):2315–2325. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2315-2325.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Souza DP, Andrade MO, Alvarez-Martinez CE, Arantes GM, Farah CS, Salinas RK. A component of the Xanthomonadaceae type IV secretion system combines a VirB7 motif with a N0 domain found in outer membrane transport proteins. PLoS Pathogens. 2011;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002031.e1002031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Da Silva ACR, Ferro JA, Reinach FC, et al. Comparison of the genomes of two Xanthomonas pathogens with differing host specificities. Nature. 2002;417(6887):459–463. doi: 10.1038/417459a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Facincani A, Moreira L, Soares M, et al. Comparative proteomic analysis reveals that T3SS, Tfp, and xanthan gum are key factors in initial stages of Citrus sinensis infection by Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri . Functional & Integrative Genomics. 2013:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10142-013-0340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soares MR, Facincani AP, Ferreira RM, et al. Proteome of the phytopathogen Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri: a global expression profile. Proteome Science. 2010;8, article 55 doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-8-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacob TR, Laia ML, Ferro JA, Ferro MIT. Selection and validation of reference genes for gene expression studies by reverse transcription quantitative PCR in Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri during infection of Citrus sinensis. Biotechnology Letters. 2011;33(6):1177–1184. doi: 10.1007/s10529-011-0552-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laia ML, Moreira LM, Dezajacomo J, et al. New genes of Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri involved in pathogenesis and adaptation revealed by a transposon-based mutant library. BMC Microbiology. 2009;9, article 12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagai H, Kubori T. Type IVB secretion systems of legionella and other gram-negative bacteria. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2011;2, article 136 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrieux L, Bourg G, Pirone A, O’Callaghan D, Patey G. A single amino acid change in the transmembrane domain of the VirB8 protein affects dimerization, interaction with VirB10 and Brucella suis virulence. FEBS Letters. 2011;585(15):2431–2436. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sivanesan D, Baron C. The dimer interface of Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB8 is important for type IV secretion system function, stability, and association of VirB2 with the core complex. Journal of Bacteriology. 2011;193(9):2097–2106. doi: 10.1128/JB.00907-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Y, Liu G, Li S, et al. Role of a type IV-like secretion system of Streptococcus suis 2 in the development of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2011;204(2):274–281. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He Y-Q, Zhang L, Jiang B-L, et al. Comparative and functional genomics reveals genetic diversity and determinants of host specificity among reference strains and a large collection of Chinese isolates of the phytopathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Genome Biology. 2007;8(10, article R218) doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, Xiao M, Geng X, Liu J, Chen J. Horizontal transfer of genetic determinants for degradation of phenol between the bacteria living in plant and its rhizosphere. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2007;77(3):733–739. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornelis GR, Van Gijsegem F. Assembly and function of type III secretory systems. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2000;54:735–774. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossier O, Van Den Ackerveken G, Bonas U. HrpB2 and hrpF from Xanthomonas are type III-secreted proteins and essential for pathogenicity and recognition by the host plant. Molecular Microbiology. 2000;38(4):828–838. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wengelnik K, Bonas U. HrpXv, an AraC-type regulator, activates expression of five of the six loci in the hrp cluster of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Journal of Bacteriology. 1996;178(12):3462–3469. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3462-3469.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo X, Zou H, Li Y, Zou L, Chen G. HrpD6 gene determines Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae to trigger hypersensitive response in tobacco and pathogenicity in rice. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao. 2010;50(9):1155–1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roine E, Saarinen J, Kalkkinen N, Romantschuk M. Purified HrpA of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 reassembles into pili. FEBS Letters. 1997;417(2):168–172. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haapalainen M, Van Gestel K, Pirhonen M, Taira S. Soluble plant cell signals induce the expression of the type III secretion system of Pseudomonas syringae and upregulate the production of pilus protein HrpA. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2009;22(3):282–290. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-3-0282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]