Abstract

Estrogens have been shown to rapidly promote male copulatory behaviors with a time-course that suggests rapid signaling events are involved. The present study tested the hypothesis that estrogen acts through a novel Gq protein-coupled membrane estrogen receptor (ER). Thus, either estradiol (E2), STX (a diphenylacrylamide compound that selectively activates a membrane ER pathway), or vehicle were administered acutely to castrated male rats that bore sc dihydrotestosterone implants to maintain genital sensitivity. Appetitive (level changes, genital investigation) and consummatory (mounts, intromissions, ejaculations) components of male sexual behavior were measured in a bilevel testing apparatus. Testing showed that E2 treatment promoted olfactory and mounting behaviors, but had no effect on motivation as measured by anticipatory level changes. STX treatment showed no effect on either component of male sexual behavior. These results support previous results that showed that E2 can rapidly affect male sexual behaviors, but fail to support a role for the specific membrane-initiated pathway activated by STX.

Keywords: estradiol, STX, copulatory behavior, mounting behavior, olfactory behavior, bilevel test, sexual motivation

Introduction

Sexual behavior of the male rat is characterized by a discreet series of behaviors, including sniffing, mounting, intromission and culminating in ejaculation (Hull, Meisel, & Sachs, 2002). While these behaviors are most often thought of as a whole, they can be divided into two distinct components, an appetitive component (in which the male seeks out and investigates a female) and a consummatory component (in which the male mounts, intromits and ejaculates). It is well established that the testicular hormone testosterone (T) plays an essential role to promote both the appetitive and consummatory components of sexual behavior in male mammals (Hull et al., 2002). Testosterone produces its effects by acting on nuclear androgen receptors located in hormone-sensitive brain regions including the medial preoptic area (MPOA) and the anterior hypothalamus. The MPOA and anterior hypothalamus are critical for integrating hormonal and sensory information into appropriate autonomic, somatomotor and motivational responses necessary for copulation (Hull et al., 2002). The MPOA receives relevant sexual input from autonomic, visual, auditory, and olfactory brain areas and sends output to other brain areas that are important for successful copulation (Simerly & Swanson, 1986). Biochemical studies have demonstrated that T can be aromatized to estradiol (E2) (Naftolin, Ryan, & Petro, 1972) or reduced to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in the brain (Denef, Magnus, & McEwen, 1973). Behavioral studies suggest that T acts, at least in part, through its active estrogenic metabolite. Systemic treatment or MPOA application of DHT alone is not effective in promoting male copulatory behaviors in castrated male rats (Davidson, 1969). In contrast, treatment of castrated males with E2 alone restores appreciable levels of male sexual behavior, while treatment with E2 and DHT together activate all components of male sexual behavior and are as effective as T (Baum, 2007; Christensen & Clemens, 1974; Feder, Naftolin, & Ryan, 1974). Complementary studies demonstrated that aromatase inhibitors or estrogen receptor antagonists dramatically inhibited male sexual behaviors when given systemically or applied centrally (Bonsall, Clancy, & Michael, 1992; Christensen & Clemens, 1975; Clancy, Zumpe, & Michael, 1995; Vagell & McGinnis, 1997; Roselli, Cross, Poonyagariyagorn, & Stadelman, 2003; Beyer, Morali, Naftolin, Larsson, & Perez-Palacios, 1976; Luttge, 1975). Thus, T appears to function as a prohormone that provides both estrogen and androgen stimulation to the CNS.

Steroid hormones are classically regarded to act on intracellular receptors to regulate nuclear-initiated gene transcription. Receptors for androgens and estrogens are co-expressed in neurons of the MPOA and activated during mating (Greco, Edwards, Michael, & Clancy, 1998). Indeed, it has been determined that for robust mating behavior to occur, T must act over a time scale of days, which indicates a genomic mechanism of action (McGinnis, Mirth, Zebrowski, & Dreifus, 1989). Inhibition of protein synthesis within the MPOA suppresses mounting behaviors in castrated T-treated male rats, further indicating that a classical mode of steroid action is at least partially necessary for the display of male mating behaviors (McGinnis & Kahn, 1997). At least one of the genomic actions of T in the MPOA is the induction of aromatase expression which has a time-course similar to activation of copulatory behavior (Christensen & Clemens, 1975; Abdelgadir et al., 1994) However, the mechanisms by which the generated E2 activates mating behaviors, both appetitive and consummatory, are not well understood.

It is now clear that steroid hormones can also activate membrane-initiated signaling events to produce rapid behavioral responses (Cornil & Charlier, 2010). We demonstrated earlier that E2, but not T, stimulates mounting behavior within 35 min of administration. This is a time frame in which significant nascent protein synthesis would not be expected to occur (Shang, Hu, DiRenzo, Lazar, & Brown, 2000), thus providing indirect evidence that this action is mediated through a non-genomic mechanism (Cross & Roselli, 1999). Similar effects were reported to occur within 10–15 min and vanish after 30 min in castrated quail and mice primed with a low dose of testosterone (Taziaux, Keller, Bakker, & Balthazart, 2007; Cornil, Dalla, Papadopoulou-Daifoti, Baillien, & Balthazart, 2006a). Support for the idea that E2 acts at the cell membrane to activate male sexual behavior was provided by the demonstration that bilateral MPOA implants of a membrane-impermeable form of E2 (i.e. E2 conjugated to bovine serum albumin) maintained mating behaviors in castrated DHT-treated rats (Huddleston, Paisley, Graham, Grober, & Clancy, 2007). However, the nature of the receptor involved in this response remains unknown.

Several potential mechanisms exist that could mediate rapid membrane-initiated responses to E2 (Kelly & Ronnekleiv, 2008). These include E2 activation of cell surface membrane estrogen receptors (mER). In particular, substantial evidence has shown that E2 modulates hypothalamic ion channels and phospholipase C through the activation of a unique Gq protein-coupled mER. STX, a diphenylacrylamide compound that does not bind ERα or ERβ mimics these effects (Qiu et al., 2003). Both E2 and STX are fully efficacious in ERα-, ERβ- and GPR-30-knockout mice in an ICI 182,780 reversible manner that further implicates a unique, but unidentified Gq protein-coupled mER (Roepke, Qiu, Bosch, Ronnekleiv, & Kelly, 2009). The present experiments evaluated the potential short latency effects of the natural estrogen E2 and the synthetic estrogenic compound STX on male sex behaviors. In order to accomplish this, male rats were trained in the bilevel chamber, an apparatus that measures both the appetitive and consummatory aspects of copulatory behavior (Mendelson & Pfaus, 1989). Once trained, the rats were either gonadectomized (genital sensitivity was maintained with DHT implants; GDX+DHT) or left intact (INT). A group of GDX+DHT rats were then treated with either E2 or STX during different trials to elucidate their ability to activate sexual behaviors in a rapid fashion. Although we hypothesized that both E2 and STX administration would rapidly elicit appetitive and consummatory aspects of male sexual behavior in this experimental model, our results show that only E2 was active in this paradigm.

Research Design and Methods

Animals

Adult Sprague-Dawley rats (20 females and 26 males) were purchased from Charles Rivers (Gilroy, CA) and were housed under a 12 hr. reversed light/dark cycle with lights off at 0900. Food and water were available ad libitum and all animals were pair housed in standard rat cages with cob bedding. All animal procedures were completed in accordance with institutional regulations and with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Surgeries

All surgeries were performed while the animals were anesthetized with isoflurane. Females were ovariectomized and given subcutaneous (sc) silicone elastomer capsules (10 mm) filled with a mixture of crystalline cholesterol and 17β-estradiol (E2) in a ratio of 9 to 1. Following behavioral screening and assignment to treatment groups (see below), males were gonadectomized (GDX) and given sc capsules (10 mm) filled with undiluted DHT. This size of DHT capsule has been reported to produce physiological concentrations of serum DHT and maintain the sensitivity and erectile capacity of the penis (Parte & Juneja, 1992; Huddleston et al., 2007; Lugg, Rajfer, & González-Cadavid, 1995). Sham operated animals were anesthetized and all incisions were made, but the testes were not removed. These animals were implanted with empty capsules.

Behavioral testing

Stimulus females were allowed to recover from surgery and implant placement for at least one week prior to the start of behavioral testing. In order to induce behavioral estrus, females received 0.5 mg progesterone sc in 0.5 ml sesame oil 4–6 hours before being paired with males. This treatment produced robust female sex behavior in all animals. All behavioral testing took place during the dark cycle under dim red light illumination.

All males were given 20 minutes of exposure to females twice a week for 2 weeks to gain sexual experience and to screen for non-copulators. These tests were conducted in a semicircular chamber (30.5 cm radius). Only males that achieved ejaculation by the fourth exposure continued on in the experiment (19 out of 26 animals or 73% of the animals achieved ejaculation).

Bilevel testing

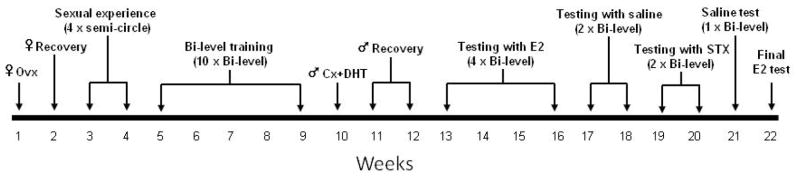

Following initial sexual experience, both males and females were acclimated to the bilevel chamber, an apparatus that measures both copulatory and sexual motivation behavior (Mendelson & Pfaus, 1989). Each animal was allowed to explore the chamber alone for 15 minutes/day for 4 days. Once acclimatized to the apparatus, males were conditioned to expect a female in the chamber by receiving a vehicle injection and then 15 minutes later they were placed in the chamber. After spending 5 minutes alone, a stimulus female was introduced and cohabitated for another 15 minutes. The conditioning trials occurred twice a week for five weeks so that each male was exposed to a female in the chamber on 10 separate occasions. Behavioral trials conducted in the bilevel apparatus were recorded on digital video and scored by a blind observer. The frequency and latency of the following measures as defined previously (Cross & Roselli, 1999) were scored: level changes, genital sniffs, thrustless mounts, mounts with thrusts, intromissions, and ejaculations. Copulatory behavior scores from the last conditioning trial were used to distribute the males into three experimental groups that exhibited similar behavioral characteristics prior to any treatments. The three groups were: intact males that underwent sham surgery and assigned to receive sc vehicle injections (INT), GDX males given DHT implants and assigned to receive sc vehicle injections (DHT+VEH) and GDX males given DHT implants and assigned to receive sc drug treatments (DHT+TX). Drug treatments and behavioral testing began two weeks after the males underwent surgery, a timeframe that has been shown sufficient to reduce circulating hormone levels from 4 ng/ml to less than 70 pg/ml (Roselli & Resko, 1984). On the day of testing, each male was given a sc injection of the VEH or experimental drug (E2, 100 μg/kg or STX, 6 and 12 mg/kg) and then placed in the bilevel chamber 15 minutes later. These tests followed the same procedure as the conditioning trials and were administered twice a week. Each animal underwent 10 testing trials. Males in the DHT+TX group were tested sequentially with E2 and STX that were separated by tests with VEH. After the final STX trial, males were tested once with saline before they were given a final trial with E2 to counterbalance the sequential drug treatment protocol. A summary of the experimental design is depicted in Fig. 1. The treatment schedule is indicated in the figure legends of the results.

Figure 1.

Experimental design and treatment time line. Adult stimulus female rats were ovariectomized prior to testing. Adult male rats were given sexual experience with estrus-induced females prior to training in the bilevel apparatus for 5 wk. The males were then castrated and given sc implants of DHT. Males were allowed to recover from surgery (2 wk) and then tested in the bilevel apparatus 15 min after receiving sc injections of E2 (4 trials); saline (2 trials); STX (2 trials); saline (1 trial), and E2 (final trial) over sequential weeks.

Drugs and treatments

The steroids E2, DHT and progesterone were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO). STX was synthesized by AAPharmSyn, LLC (Ann Arbor, MI). For injections, E2 and STX were dissolved in 20% Pharmasolve (Ashland Specialty Ingredients, Wayne, NJ) in lactated Ringers solution. The dose of E2 used replicated our earlier study (Cross & Roselli, 1999), while the doses of STX were chosen for the efficacy in modulating body temperature and food intake (Roepke et al., 2010).

Data analysis

Each behavior was analyzed using a repeated measure two-way ANOVA (experimental group x trial) and Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were used when necessary (Norman & Streiner, 2012). Tukey’s post-hoc tests were used when appropriate. As our experiment was not factorial in design, each cohort of animals was treated as a separate group. Because of our a priori hypothesis that E2 and STX administration would increase some sexual behaviors, we also averaged the behaviors seen during those drug trials and analyzed them using a one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc tests. For example, during the E2 trials, comparison was made among average performances of the INT (n=6), DHT + E2 (n=6) and DHT + VEH (n=7) groups. Identical comparisons were made during the saline and STX trials. All statistical analyses were done using the program “Statistical Program for the Social Sciences” (IBM, Armonk, New York). Differences between experimental groups were considered significant at a level of P < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Appetitive behaviors

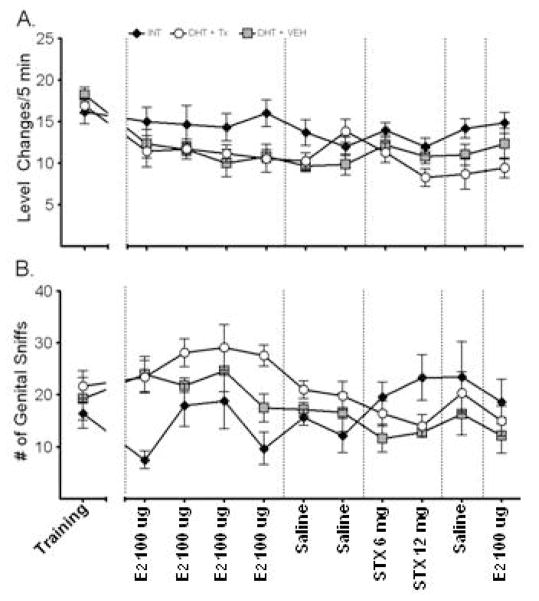

During the conditioning trials, males reached an asymptote in level changing behavior within three weeks. This remained stable through the rest of the conditioning trials. When the animals were compared according to their subsequent experimental groups, there were no significant differences in level changing behaviors (data not shown). During the drug treatments, there was no effect of trial nor a trial by experimental group interaction on level changes [Fs (9/18,144) ≤1.52, ps≥0.14], however there was a main effect of experimental group [F (1, 16) =3.88, p=0.042], Figure 2A. Tukey’s post-hoc test showed that DHT+TX was not different from DHT+VEH but did exhibit significantly fewer level changes than INT animals. When data were averaged by treatment, a main effect of experimental group was evident during the E2 trial only [F (2, 18) =3.80, p=0.045]. Tukey’s post-hoc test indicated that DHT+TX and DHT+VEH treated male exhibited significantly fewer levels changes than the INT group.

Figure 2.

Short latency effects of E2 and STX on frequency of level changing behavior (A) and genital investigatory behavior (B). Values are mean ± SEM; n = 6–7 rats per group. Experimental groups are signified by different symbols and trials are labeled on the x-axis. The frequency of level changes showed a significant group difference but not a trial difference or interaction. Reanalysis of the data averaged by treatment showed a main effect of experimental group during the E2 trials only and indicated that E2 treated male exhibited significantly fewer levels changes than INT or VEH groups. The frequency of genital sniffs showed a main effect of trial and a trial by group interaction, but no effect of experimental group. Reanalysis of the results averaged by treatment showed that E2 treatment significantly increased genital sniffs compared to INT controls, while STX significantly lowered genital sniffs.

Once the female rat is introduced into the bilevel chamber, the suite of sexual behaviors almost always starts with the male investigating the female and sniffing her genitals. All three groups displayed this behavior, Figure 2B. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a main effect of trial and a trial by group interaction [Fs (4.5/9.01, 67.6) ≥3.37, ps≤0.011], but there was no main effect of experimental group [F (2, 17) =3.90, p=0.043]. When the data were averaged by treatment, a main effect was evident during both the E2 trials [F (2, 17) =3.90, p=0.043] and the STX trials [F (2, 18) =3.745, p=0.046], but not the saline trials. Post-hoc analysis found that when treated with E2, animals showed a significantly higher number of sniffs than INT animals, while when treated with STX, animals showed significantly lower numbers of sniffs than INT animals, indicating that acute E2 treatment is effective at restoring some appetitive sex behaviors in castrated, DHT-maintained males.

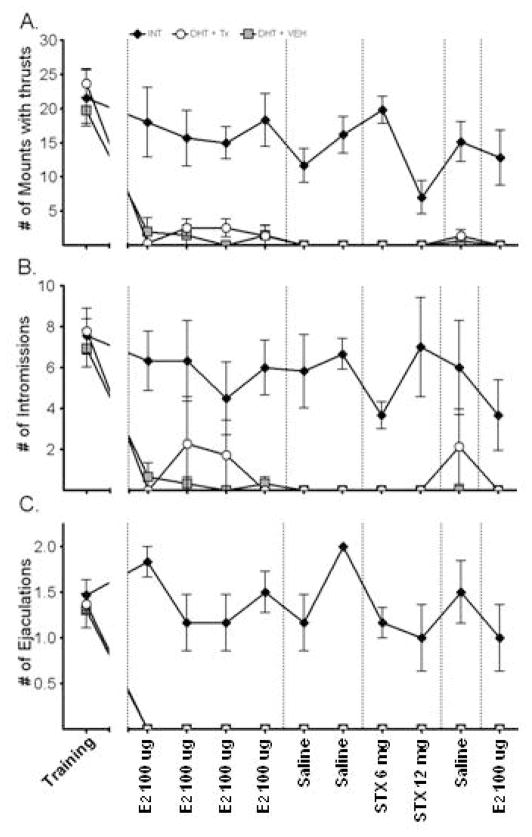

Consummatory behaviors

Overall, the frequency of male consummatory sex behaviors, including mounts with thrusts, intromissions and ejaculations, declined significantly in DHT+VEH and DHT+TX groups over time and in comparison to the INT group, Figure 3A–C. For each of these behaviors, there was no effect of trial, or trial by group interaction [Fs (9, 15) ≥1.011, ps≥0.434], but there was a main effect of experimental group [Fs (2, 15) =12.98, p=0.001]. Post-hoc tests indicated that INT males showed higher levels of all consummatory behaviors than DHT+VEH and DHT+TX males indicating that there was no effect of E2 or STX administration on these behaviors. Significantly greater behaviors in the INT males were also evident when averaged behaviors were analyzed by drug trial.

Figure 3.

Short latency effects of E2 and STX on Mounts with thrust (A); Intromissions (B); and Ejaculations (C). Values are mean ± SEM; n = 6–7 rats per group. Experimental groups are signified by different symbols and trials are labeled on the x-axis. For all behaviors, INT males showed significantly higher behaviors than DHT+VEH and DHT+TX across all trials, indicating that E2 and STX had no effect.

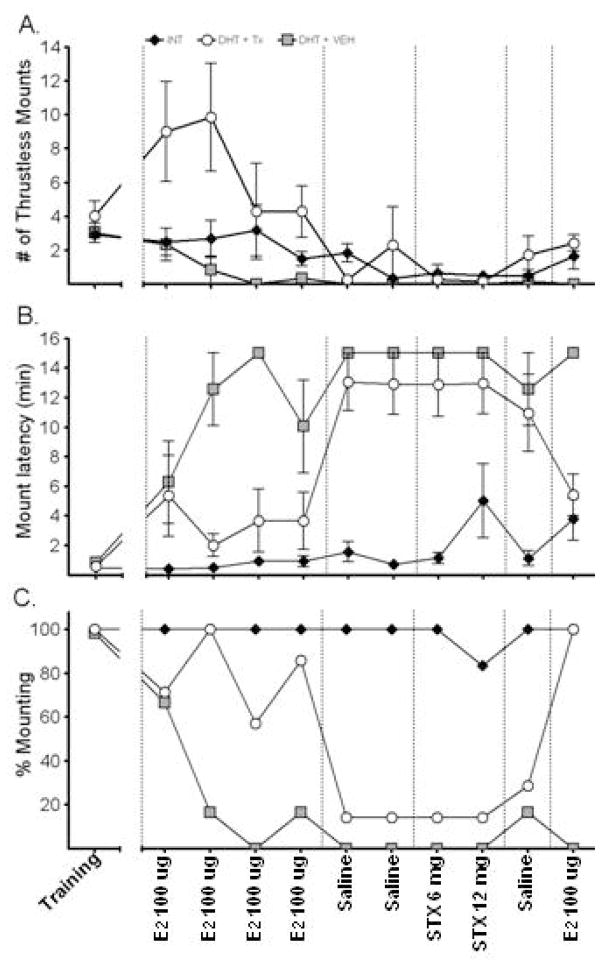

Despite the obvious deficits in sexual performance that were not reversed by E2 or STX treatments, E2, but not STX, did affect the frequency of thrustless mounts (Figure 4A). For this behavior, there was a significant effect of trial [F (2.16, 21.6) = 5.75, p=0.009], a trend for trial by group interaction [F (2.16, 21.6) = 3.83, p=0.063] and a significant main effect of group [F (1, 10) =5.182, p=0.046]. When the data were averaged by treatment, a main effect was evident during the E2 trials only [F (2, 11) =6.90, p=0.025]. Tukey’s post-hoc test indicated that E2 stimulated a greater number of thrustless mounts in comparison to INT and DHT+VEH treated rats.

Figure 4.

Short latency effects of E2 and STX on frequency of thrustless mounts (A); mount latency (B); and % of males mounting during each trial (C). Values for A & B are mean ± SEM; n = 6–7 rats per all groups. Experimental groups are signified by different symbols and trials are labeled on the x-axis. For thrustless mounts (A) there was a significant effect of treatment and trial, and a trend for an interaction (p = 0.06). Reanalysis of the mean data per treatment period indicated that E2 treated males exhibited greater thrustless mount frequencies than INT or VEH groups. Mount latency (B) showed a significant effect of experimental group and trial and a significant interaction. Reanalysis of the mean data per treatment showed that E2 treatment, but not STX or VEH, maintained latency at a level equivalent to INT males.

The mount latency (defined as the time from introduction of the female to the first mount with or without thrusts) follows a similar pattern to thrustless mounts (Figure 4B). There was a main effect of trial [F (4.415, 66.223) =7.294, p<0.001], a trial by group interaction [F (8.83, 69.223) =0.927, p=0.018] and a main effect of experimental group [F (2, 17) =19.092, p<0.001]. Tukey’s post-hoc tests show that the INT males have a significantly shorter latency to mount than either experimental treatment group. However, when the data are averaged by treatment, it becomes apparent that during E2 trials, only the DHT+VEH group has a higher latency [F (2, 17) =10.648, p=0.001 and Tukey’s post-hoc]. This effect is lost during the saline and STX trials, when both the DHT+VEH and DHT+TX groups have increased latencies compared to intact animals (Fs(2,18)≥16.835, p≤0.001 and Tukey’s post-hoc]. These results indicate that short-term estrogen can restore the latency to mounting behavior to that seen in an intact animal, but that STX administration cannot.

An effect of E2 is also evident when the data are expressed as the percentage of animals exhibiting mounting behavior (both with and without thrusts), Figure 4C. By the second trial, only 20% of the DHT+VEH group displayed any type of mounting behavior, whereas 100% of INT rats were showing these behaviors. By the third test, this was reduced to ~10% and remained at or below this level throughout the remaining trials. The percentage of rats in the DHT+TX group was not different from the INT group during E2 administration, but was significantly reduced during trials in which STX or saline was administered. In a final E2 trial that followed the STX trial and a saline trial, 100% of E2 treated males mounted. Thus, acute E2 treatment enhanced the proportion of GDX+DHT males that displayed mounting behavior.

Discussion

In this study, we used the diphenylacrylamide compound STX to investigate if the short latency effects that E2 exerts on sexual behavior are mediated through a putative Gq-coupled mER. We found that while E2 administration to GDX males bearing DHT capsules increased anogenital investigation and mounting behavior, and decreased mount latency within 20 minutes of administration, treatment with STX had no effects on these behaviors. Neither E2 nor STX affected anticipatory level-changing behavior within the short time frame examined. These results indicate that the short-latency effect of E2 on copulatory behaviors is produced by a different mechanism than the Gq protein-coupled mER pathway shown to mediate the rapid STX effects on neuronal activity, body temperature and energy homeostasis (Qiu et al., 2003; Roepke et al., 2010).

The present results replicated our previous finding that injection of a high dose of E2 (100 μg) rapidly facilitates anogenital investigation and reduces mount latency (Cross & Roselli, 1999). These results may be interpreted to infer that E2 acutely enhances sexual motivation. However, this conclusion is not supported when sexual motivation was independently assessed by the performance in the bilevel apparatus. The number of level changes displayed in this apparatus prior to the introduction of an estrous female is a form of appetitive sexual behavior that is used to measure sexual motivation in male rats (Van Furth & Van Ree, 1996a; Mendelson & Pfaus, 1989; Van Furth & Van Ree, 1996b). Thus, the lack of an acute effect of E2 or STX on level changes in the present study does not support a membrane-initiated mechanism of steroid action on sexual motivation in male rats.

The role of androgens and estrogens in the male rat’s precopulatory behaviors and sexual motivation has been most extensively studied in experimental paradigms that test chronic steroid effects, presumably mediated through classical steroid receptor pathways. T and the combination of DHT and E2 have been shown to maintain chemoinvestigation and sexual motivation in castrated male rats under these conditions (Attila, Oksala, & Ågmo, 2010; Bakker, Brand, Van Ophemert, & Slob, 1994; Merkx, Slob, & van der Werff ten Bosch, 1989). Recent evidence shows that DHT alone can partly maintain sexual motivation in castrated male rats (Attila et al., 2010). However, contradictory data exist regarding whether aromatization of T to E2 is absolutely required or whether E2 can act alone (Merkx, 1984; Vagell & McGinnis, 1997; Roselli et al., 2003; Matuszczyk & Larsson, 1994).

In the present study, E2, but not STX, rapidly increased the frequency of thrustless mounts. Mounts without thrusts are the lowest element of the mating behavior pattern exhibited by male rats and were referred to originally as mounting and clasp without palpation by Beach (Beach, 1944). It is the first element to reappear in castrated males given testosterone and represents a low level of sexual arousal (Young, 1961). These results differ from our previous study in which E2 seemed to exert a more robust effect by rapidly stimulating total mounts (with and without thrusts). There are possible reasons for this discrepancy. The studies differed procedurally in both the vehicle (2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin versus Pharmasolve) and route of injection (ip versus sc) used for drug delivery. The studies also differed significantly in design; the earlier study evaluated the effect of a single E2 injection in a semicircular arena, while the present study used repeated injections over weekly intervals and observed behaviors in a bilevel apparatus.

In contrast to E2, STX had no effect on appetitive or consummatory sexual behaviors. This result suggests that E2 acts through a pathway other than the Gq-coupled mER stimulated by STX (Qiu et al., 2003). However, it also may reflect the order in which E2 and STX were administered after castration and the fact that the males had been castrated for a comparatively shorter time during the E2 trials than the STX trials. Indeed, in the absence of continual E2 priming, mounting diminished during the initial E2 trials. A final E2 trial conducted after STX treatment stimulated low levels of thrustless mounting in all animals. This result indicates that the inability of STX to affect male sexual behavior is not due entirely to an order effect. Nor does it appear that STX exerts negative effects on motor activity because the frequency of level changes during the bilevel test – a proxy measure of motor activity – were not different between treatment groups (data not shown).

Previous studies in quails demonstrated that rapid increases and decreases in brain estrogen availability induce corresponding changes in both appetitive sexual behaviors, (measured by social proximity and cloacal sphincter responses) and consummatory behaviors (measured by mount frequency and latency) (Cornil, Dalla, Papadopoulou-Daifoti, Baillien, & Balthazart, 2006b; Cornil, Taziaux, Baillien, Ball, & Balthazart, 2006). Inhibition of aromatase activity in mice rapidly and almost completely suppresses male copulatory behaviors within 10 – 20 minutes of administration and is reversed by a simultaneous injection of E2. Similarly, a single injection of E2 to aromatase knockout mice activated copulatory behaviors within 15 minutes. However, unlike the quail, inhibition of aromatase fails to rapidly alter anogenital investigations or odor preferences for an estrous female in mice (Taziaux et al., 2007). These latter results suggest that changes in estrogen rapidly alter the expression of consummatory sexual behaviors without eliciting similar changes in sexual motivation. Consistent with the present study, these findings suggest that one important difference between appetitive and consummatory sexual behaviors in rodents might be their susceptibility to rapid modulation by E2.

In other studies (Taziaux et al., 2007; Cornil et al., 2006b), more robust behavioral effects were elicited when priming with low dose E2 benzoate for 9 days preceded acute E2 administration. It is also clear that E2 regulates masculine sexual behavior by signaling through classical estrogen receptor alpha (ERα)-mediated transcriptional mechanisms (Rissman, Wersinger, Fugger, & Foster, 1999; McDevitt et al., 2007; Wersinger et al., 1997; Ogawa et al., 1998; Wersinger & Rissman, 2000). Thus, it is likely that, similar to estrogen facilitation of lordosis behavior (Kow & Pfaff, 2004), the effects of estrogens on masculine behavior involve an integrated response initiated at both the membrane and the genome. Specifically, E2 has been shown to transcriptionally regulate genes that are important for cell signaling and may be essential for transducing membrane-initiated ER responses (Malyala, Pattee, Nagalla, Kelly, & Ronnekleiv, 2004; Boulware, Kordasiewicz, & Mermelstein, 2007) that could, in turn, contribute to the expression of masculine sexual behavior.

In conclusion, the present study indicates that activation of a unique Gq protein-coupled membrane receptor by STX treatment alone is not sufficient to stimulate masculine behavior even at doses and within time frames that are effective for regulating other centrally mediated processes such as body temperature regulation and energy homeostasis (Roepke et al., 2010). We cannot exclude the possibility that some steroid priming is needed for STX to acutely facilitate male behavior, although E2 acts even in its absence. Nonetheless, another pathway or pathways may be more critical. Thus, other candidate membrane receptors for E2 such as GPR30 and membrane-associated ERα that have been shown to rapidly mediate behaviors such as anxiety and lordosis (Dewing et al., 2007; Kastenberger, Lutsch, & Schwarzer, 2012) should be tested in future experiments for their possible contribution to the regulation of male sexual behavior.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01OD011047 (CER); R01 NS38809 (MJK) and T32 HD007133 (KRK). We thank Linda Miksovski for technical assistance.

Reference List

- Abdelgadir SE, Resko JA, Ojeda SR, Lephart ED, McPhaul MJ, Roselli CE. Androgens regulate aromatase cytochrome P450 messenger ribonucleic acid in rat brain. Endocrinology. 1994;135:395–401. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.1.8013375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attila M, Oksala R, Ågmo A. Sexual incentive motivation in male rats requires both androgens and estrogens. Horm Behav. 2010;58:341–351. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker J, Brand T, Van Ophemert J, Slob AK. Hormonal regulation of adult partner preference behavior in neonatally ATD-treated male rats. Behav Neurosci. 1994;56:597–601. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum MJ. Neuroendocrinology of Male Reproductive Behavior. In: Lajtha A, Blaustein JD, editors. Handbook of Neurochemistry and Molecular Neurobiology Behavioral Neurochemistry, Neuroendocrinology and Molecular Neurobiology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2007. pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Beach FA. Relative effects of androgen upon mating behavior of male rats subjected to forebrain injury or castrations. J Exp Zool. 1944;97:249–295. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer C, Morali G, Naftolin F, Larsson K, Perez-Palacios G. Effect of some antiestrogens and aromatase inhibitors on androgen induced sexual behavior in castrated male rats. Horm Behav. 1976;7:353–363. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(76)90040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsall RW, Clancy AN, Michael RP. Effects of the nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor, Fadrozole, on sexual behavior in male rats. Horm Behav. 1992;26:240–254. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(92)90045-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulware MI, Kordasiewicz H, Mermelstein PG. Caveolin proteins are essential for distinct effects of membrane estrogen receptors in neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9941–9950. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1647-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen LW, Clemens LG. Intrahypothalamic implants of testosterone or estradiol and resumption of masculine sexual behavior in long-term castrated male rats. Endocrinology. 1974;95:984–990. doi: 10.1210/endo-95-4-984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen LW, Clemens LG. Blockade of testosterone-induced mounting behavior in the male rat with intracranial application of aromatization inhibitor, androst-1,4,6-trien-3,17-dione. Endocrinology. 1975;97:1545–1551. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-6-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy AN, Zumpe D, Michael RP. Intracerebral infusion of an aromatase inhibitor, sexual behavior and brain estrogen receptor-like immunoreactivity in intact male rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1995;61:98–111. doi: 10.1159/000126830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornil CA, Charlier TD. Rapid behavioural effects of oestrogens and fast regulation of their local synthesis by brain aromatase. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:664–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02023.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornil CA, Dalla C, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z, Baillien M, Balthazart J. Estradiol rapidly activates male sexual behavior and affects brain monoamine levels in the quail brain. Behav Brain Res. 2006a;166:110–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornil CA, Dalla C, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z, Baillien M, Balthazart J. Estradiol rapidly activates male sexual behavior and affects brain monoamine levels in the quail brain. Behav Brain Res. 2006b;166:110–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornil CA, Taziaux M, Baillien M, Ball GF, Balthazart J. Rapid effects of aromatase inhibition on male reproductive behaviors in Japanese quail. Horm Behav. 2006;49:45–67. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross E, Roselli CE. 17beta-Estradiol rapidly facilitates chemoinvestigation and mounting in castrated male rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R1346–R1350. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JM. Effects of estrogen on the sexual behavior of male rats. Endocrinology. 1969;84:1365–1372. doi: 10.1210/endo-84-6-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denef C, Magnus C, McEwen BS. Sex differences and hormonal control of testosterone metabolism in rat pituitary and brain. J Endocr. 1973;59:605–621. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0590605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewing P, Boulware MI, Sinchak K, Christensen A, Mermelstein PG, Micevych P. Membrane estrogen receptor-α interactions with metabotropic glutamate receptor 1a modulate female sexual receptivity in rats. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9294–9300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0592-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder HH, Naftolin F, Ryan KJ. Male and female sexual responses in male rats given estradiol benzoate and 5α-androstan-17β-ol-3-one propionate. Endocrinology. 1974;94:136–141. doi: 10.1210/endo-94-1-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco B, Edwards DA, Michael RP, Clancy AN. Androgen receptors and estrogen receptors are colocalized in male rat hypothalamic and limbic neurons that express fos immunoreactivity induced by mating. Neuroendocrinology. 1998;67:1828. doi: 10.1159/000054294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huddleston GG, Paisley JC, Graham S, Grober MS, Clancy AN. Implants of estradiol conjugated to bovine serum albumin in the male rat medial preoptic area promote copulatory behavior. Neuroendocrinology. 2007;86:249–259. doi: 10.1159/000107695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull EM, Meisel RL, Sachs BD. Male sexual behavior. In: Pfaff DW, Arnold AP, Etgen AM, Fahrbach SE, Rubin RT, editors. Hormones, Brain and Behavior. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 3–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenberger I, Lutsch C, Schwarzer C. Activation of the G-protein- coupled receptor GPR30 induces anxiogenic effects in mice, similar to oestradiol. Psychopharmacology. 2012;221:527–535. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2599-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MJ, Ronnekleiv OK. Membrane-initiated estrogen signaling in hypothalamic neurons. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;290:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kow LM, Pfaff DW. The membrane actions of estrogens can potentiate their lordosis behavior-facilitating genomic actions. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:12354–12357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404889101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugg JA, Rajfer J, González-Cadavid NF. Dihydrotestosterone is the active androgen in the maintenance of nitric oxide-mediated penile erection in the rat. Endocrinology. 1995;136:1495–1501. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.4.7534702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttge WG. Effects of anti-estrogens on testosterone stimulated male sexual behavior and peripheral target tissues in the castrate male rat. Physiol Behav. 1975;14:839–846. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(75)90079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malyala A, Pattee P, Nagalla SR, Kelly MJ, Ronnekleiv OK. Suppression subtractive hybridization and microarray identification of estrogen-regulated hypothalamic genes. Neurochem Res. 2004;29:1189–1200. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000023606.13670.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuszczyk JV, Larsson K. Experience modulates the influence of gonadal hormones on sexual orientation of male rats. Physiol Behav. 1994;55:527–531. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt MA, Glidewell-Kenney C, Weiss J, Chambon P, Jameson JL, Levine JE. Estrogen response element-independent estrogen receptor (ER)-{alpha} signaling does not rescue sexual behavior but restores normal testosterone secretion in male ER{alpha} knockout mice. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5288–5294. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis MY, Kahn DF. Inhibition of male sexual behavior by intracranial implants of the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin into the medial preoptic area of the rat. Horm Behav. 1997;31:15–23. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis MY, Mirth MC, Zebrowski AF, Dreifus RM. Critical exposure time for androgen activation of male sexual behavior in rats. Physiol Behav. 1989;46:159–165. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson SD, Pfaus JG. Level searching: a new assay of sexual motivation in the male rat. Physiol Behav. 1989;45:337–341. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkx J. Effect of castration and subsequent substitution with testosterone, dihydrotestosterone and oestradiol on sexual preference behaviour in the male rat. Behav Brain Res. 1984;11:59–65. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(84)90008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkx J, Slob AK, van der Werff ten Bosch JJ. Preference for an estrous female over a non-estrous female evinced by female rats requires dihydrotestosterone plus estradiol. Horm Behav. 1989;23:466–472. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(89)90036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naftolin F, Ryan KJ, Petro Z. Aromatization of androstenedione by the anterior hypothalamus of adult male and female rats. Endocrinology. 1972;90:295–298. doi: 10.1210/endo-90-1-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman GR, Streiner DL. Biostatistics: The Bare Essentials. 2. Hamilton: B.C. Decker, Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Washburn TF, Taylor J, Lubahn DB, Korach KS, Pfaff DW. Modifications of testosterone-dependent behaviors by estrogen receptor- alpha gene disruption in male mice. Endocrinology. 1998;139:5058–5069. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.12.6358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parte P, Juneja HS. Temporal changes in the serum levels of gonadotrophins and testosterone in male rats bearing subcutaneous implants of 5α-dihydrotestosterone. Int J Androl. 1992;15:355–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1992.tb01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Bosch MA, Tobias SC, Grandy DK, Scanlan TS, Ronnekleiv OK, et al. Rapid signaling of estrogen in hypothalamic neurons involves a novel G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor that activates protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9529–9540. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-29-09529.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissman EF, Wersinger SR, Fugger HN, Foster TC. Sex with knockout models: behavioral studies of estrogen receptor alpha. Brain Res. 1999;835:80–90. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roepke TA, Bosch MA, Rick EA, Lee B, Wagner EJ, Seidlova-Wuttke D, et al. Contribution of a membrane estrogen receptor to the estrogenic regulation of body temperature and energy homeostasis. Endocrinology. 2010;151:4926–4937. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roepke TA, Qiu J, Bosch MA, Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Cross-talk between membrane-initiated and nuclear-initiated oestrogen signaling in the hypothalamus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21:263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01846.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli CE, Cross E, Poonyagariyagorn HK, Stadelman HL. Role of aromatization in anticipatory and consummatory aspects of sexual behavior in male rats. Horm Behav. 2003;44:146–151. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli CE, Resko JA. Androgens regulate brain aromatase activity in adult male rats through a receptor mechanism. Endocrinology. 1984;114:2183–2189. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-6-2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA, Brown M. Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor–regulated transcription. Cell. 2000;103:843–852. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerly RB, Swanson LW. The organization of neural inputs to the medial preoptic nucleus of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1986;246:312–342. doi: 10.1002/cne.902460304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taziaux M, Keller M, Bakker J, Balthazart J. Sexual behavior activity tracks rapid changes in brain estrogen concentrations. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6563–6572. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1797-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagell ME, McGinnis MY. The role of aromatization in the restoration of male rat reproductive behavior. J Neuroendocrinol. 1997;9:415–421. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1997.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Furth WR, Van Ree JM. Appetitive sexual behavior in male rats: 1. The role of olfaction in level-changing behavior. Physiol Behav. 1996a;60:999–1005. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(96)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Furth WR, Van Ree JM. Appetitive sexual behavior in male rats: 2. Sexual reward and level-changing behavior. Physiol Behav. 1996b;60:1007–1012. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(96)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wersinger SR, Rissman EF. Oestrogen receptor α is essential for female-directed chemo-investigatory behavior but is not required for the pheromone-induced luteinizing hormone surge in male mice. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:103–110. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wersinger SR, Sannen K, Villalba C, Lubahn DB, Rissman EF, De Vries GJ. Masculine sexual behavior is disrupted in male and female mice lacking a functional estrogen receptor α gene. Horm Behav. 1997;32:176–183. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young WC. The Hormones and Mating Behavior. In: Young WC, editor. Sex and Internal Secretions. 3. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1961. pp. 1173–1239. [Google Scholar]