Abstract

Recycling in the gastrointestinal tract is important for endogenous substances such as bile acids and for xenobiotics such as flavonoids. Although both enterohepatic and enteric recycling mechanisms are well recognized, no one has discussed the third recycling mechanism for glucuronides: local recycling. The intestinal absorption and metabolism of wogonin and wogonoside (wogonin-7-glucuronide) was characterized by using a four-site perfused rat intestinal model, and hydrolysis of wogonoside was measured in various enzyme preparations. In the perfusion model, the wogonoside and wogonin were inter-converted in all four perfused segments. Absorption of wogonoside and conversion to its aglycone at upper small intestine was inhibited in the presence of a glucuronidase inhibitor (saccharolactone) but was not inhibited by a LPH inhibitor gluconolactone or antibiotics. Further investigation indicated that hydrolysis of wogonoside in the blank intestinal perfusate was not correlated with bacteria counts. Kinetic studies indicated that Km values from blank duodenal and jejunal perfusate were essentially identical to the Km values from intestinal S9 fraction but were much higher (>2-fold) than those from the microbial enzyme extract. Lastly, jejunal perfusate and S9 fraction share the same optimal pH, which was different from those of fecal extract. In conclusion, local recycling of wogonin and wogonoside is the first demonstrated example that this novel mechanism is functional in the upper small intestine without significant contribution from bacteria β-glucuronidase.

Keywords: Local recycling, flavonoid bioavailability, intestine, phenolic, phase II metabolism

Introduction

Enterohepatic and enteric recycling schemes are two well-known mechanisms that allow the recycling of compounds that undergo extensive phase II conjugation via glucuronidation and sulfation (sulfonation) 1. Among these two schemes, the enterohepatic recycling is more classical and involves the action of liver to excrete the conjugated phase II metabolites and action of the microflora or bacterial β-glucuronidases and/or sulfatases to release the aglycones (from the conjugated phase II metabolites). Released aglycones can enter the body again, thereby completing the recycling loop. Although enterohepatic recycling was first recognized more than a half century ago 2, enteric recycling has only been termed more recently 3. In enteric recycling scheme, the phase II conjugates are excreted by the enterocytes, and once again, the action of bacterial β-glucuronidases or sulfatase is required to release aglycone for reabsorption 1.

In this paper we have identified the third and perhaps equally important recycling scheme for compounds that are extensively glucuronidated in the gut: the local recycling. Wogonin, a plant di-hydroxyl flavonoid (Fig.1) that has attracted a lot of attention for its anti-tumor and anti-inflammatory activity in the gut and elsewhere, was used here as the model compound to demonstrate the presence of this recycling scheme. Wogonin was selected because it is extensively glucuronidated 4, 5. It was also chosen because of its important pharmacological activities, including its ability to restore the sensitivity of tumor necrosis factor receptor apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) in TRAIL-resistant cancer cells 6, 7, to induce apoptosis via p53-dependent PUMA induction in human colon cancer HCT116 cells8, 9. In addition, wogonin is used widely in humans, mostly in the form of herbal formulation. For example, BZL 101, an aqueous herbal extract active against breast cancer cell lines, was shown to have a favorable toxicity profile in a phase I clinical trial and demonstrated encouraging clinical activity 10. Hange-shashin-to (HST), a combination of seven herbs including Scutellaria baicalensis, was found to suppress inflammatory bowel diseases 11. Another reason to study wogonin was several flavonoids were shown to be active in management of the gastrointestinal diseases 12-15. For example, silibinin was shown to inhibit hepatitis C virus 12,13, whereas green tea flavonoids were shown to be active against colon cancer 15. Lastly, wogonin was also selected because large quantities of wogonoside were available commercially at a reasonable cost.

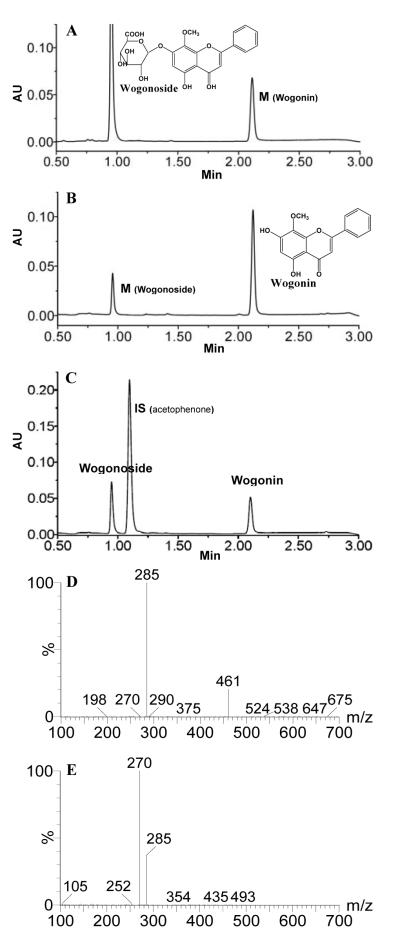

Fig.1.

Representative UPLC chromatograms of wogonin and wogonoside, as well as MS2 scan for each compound. Panel A shows wogonoside and its corresponding metabolite (wogonin) in a rat jejunal perfusate sample using wogonoside (20 μM). Panel B shows wogonin and its corresponding metabolite (wogonoside) in a rat jejunal sample using wogonin (5 μM). Panel C shows the retention time of internal standard (IS) acetophenone to demonstrate that the IS will not co-elute with wogonoside or wogonin. Panels D, E show the MS2 scan for wogonoside and wogonin, respectively, confirming their identities. Specific conditions for MS (m/z and CE) are shown in Table S1 of Supplement Materials.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Wogonin and wogonoside (≥98%, HPLC grade, confirmed by LC-MS/MS) were purchased from Chengdu Mansite Pharmaceutical Co. LTD (Chengdu, China). Gluconolactone, saccharolactone, magnesium chloride, dithiothreitol (DTT), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), bovine serum albumin (BSA, quantity 98%), Hank’s balanced salt solution (powder form), benzylpenicillin and streptomycin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Standard microbiological plates covered with pre-made culture media were purchased from Guangzhou Dijing Microbe Technology Company (Guangzhou, China). All other materials were typically analytical grade or better, and were used as received.

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (80–110 days old) weighing from 280 to 350 g were obtained from laboratory animal center of Southern Medical University. The rats were fasted overnight with free access to water before the day of the experiment. No flavonoids were found in pH 6.5 HBSS buffer that had been perfused through a segment of the rat upper small intestine (i.e., jejunum), indicating that no dietary wogonin or wogonoside were detected in the rat gut.

Animal Surgery

The animal protocol used in the present study was approved by the Southern Medical University’s Ethics Committee. The intestinal surgical procedures were essentially the same as those described in previous publications with minor modification 3, 16. Here, four segments of the intestine were simultaneously perfused using the “four site (perfusion) model”. In addition, a bile duct cannulation was made. Surgical procedures commenced after anesthesia was induced by an i.p. injection of 1.2 g/kg urethane (50%, w/v). Other procedures were identical to those described previously 3. Here is a brief description, First, the duodenum was located as the intestinal segment immediately adjacent to the stomach, and two cannulae at ≈10 cm apart were inserted into two ends of the duodenum and secured with suture. Next, the jejunum was located at ≈4 cm below the duodenum, and two cannulae at ≈10 cm apart were inserted. For the terminal ileum, the outlet cannula was inserted into the ileum at ≈2 cm above the ileocecal junction, and the inlet cannula was inserted ≈10 cm above the outlet cannula. Last, the colon inlet cannula was inserted into the colon at ≈2 cm below the junction, and the outlet cannula was inserted through the anus. After cannulation, the small intestinal segments were placed carefully into the abdominal cavity, minimizing crimping or kinking of the segments to the best of our ability. The cannulated segments were kept at the same height to avoid gravitational flow, and the perfusate was driven into the cannulated segment using a perfusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, Cambridge, MA). To keep the temperature of the perfusate constant, all inlet cannulae were insulated and kept warm by a 37°C circulating water bath.

Transport and Metabolism Experiments in Perfused Rat Intestinal Model

Four segments of the intestine (duodenum, upper jejunum, terminal ileum and colon) were perfused simultaneously with perfusate containing the compound(s) of interest using an infusion pump (Model PHD2000; Harvard Apparatus, Cambridge, MA) at a flow rate of 0.168 ml/min. After a 30 min wash-out period, which is usually sufficient to achieve steady-state absorption, four samples were collected from the outlet cannula every 30 min. To terminate substrate hydrolysis by enzymes contained in perfused sample, a stop solution containing 94% acetonitrile and 6% glacial acetic acid (2 ml) was added into the receiving container prior to sample collection, which prevented hydrolysis of wogonoside and stabilized wogonin (see later). The outlet concentrations of test compounds in the perfusate were determined by UPLC.

Rat Intestine S9 Fractions

The preparation method was adapted from a previously published method of preparing microsomes 3, 16, and the only difference was that the S9 fraction was obtained following 30 min centrifugation at 9,000 × g. All solutions used and procedures employed were identical.

Microbial Enzymatic Extract from Rat Feces

Rat fecal extract was prepared using a procedure adapted from the literature with minor modification 17. Briefly, 1 g of fresh mixed feces from three SD rats was collected and added into 9 g of HBSS buffer at 4°C. Then, the feces were well suspended. The suspension was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 min and the resulting supernatant was recovered for enzyme activity (i.e., glucuronidase) assay.

Protein Concentration Measurement

Protein concentrations of rat intestine perfusates, intestinal S9 fractions and enzymatic extract of feces were measured using a protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard 18.

Hydrolysis Experiments

To determine the hydrolysis activities of β-glucuronidase in the rat intestine perfusates, wogonoside was spiked into the respective blank perfusates at a pre-determined concentration (e.g., 20 μM). For kinetic studies that determine the Km and Vmax values, concentrations of 1.25, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 60, 80 and 160 μM were used. Reactions were carried out at 37°C for a predetermined period of time (e.g., 60 min), and stopped by the addition of 94% acetonitrile/6% glacial acetic acid containing 90 μM acetophenone (2:1 v/v) as the internal standard. The reaction mixture was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 min and the supernatant was subjected to UPLC for analysis.

To determine the hydrolysis activities of intestine S9 fractions and microbial enzymatic extract, they were first diluted 10 times and 100 times respectively with HBSS buffer before reaction was allowed to proceed as described above. Dilution was necessary to allow reasonable reaction time (e.g., 15 min) without substantial loss of substrate (<30%).

Determination of Bacterial Counts in the Perfusate

Freshly collected perfusate samples from four segments of intestine were used for determination of the bacteria counts. Samples were spread over the culture plates and then incubated exactly according to the method described previously in the Methods in Molecular Biology 19, 20, and bacterial colonies were counted using the method described on the page 95 of Appendix XI J of 2005 Edition of Chinese Pharmacopeia 21.

UPLC Analysis of Wogonin and Wogonoside

The validated method for analyzing wogonin and wogonoside was as follows: system, Waters Acquity UPLC with photodiode array detector and Empower™ software; column, BEH C18, 1.7 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm; mobile phase B, 100% acetonitrile, mobile phase A, 100% aqueous buffer (0.1%, v/v formic acid, pH 2.5); flow rate 0.4 ml/min; gradient, 0 to 1.5 min, 30-40% B, 1.5 to 2.5 min, 40-70% B, 2.5 to 3.0 min, 70-30% B; wavelength, 280 nm for flavones and their respective glucuronides and acetophenone; and injection volume, 10 μl. The tested linear response range was 0.625-160 μM (for a total of 9 concentrations) for wogonoside and 0.625-40 μM (7 concentrations) for wogonin. Analytical methods for each test compound were validated for inter-day and intra-day variation using 6 samples at three concentrations (40, 10 and 1.25 μM). Precision and accuracy for both compounds were in the acceptable range (usually <10%).

Confirmation of Flavone Glucuronide Structure by LC-MS/MS

Wogonin and its corresponding glucuronide wogonoside were separated by the same UPLC system without altering the chromatographic conditions. The separation, detection and analysis of these compounds were achieved by Waters Micromass Quattro Premier XE, operated in the positive ion mode. The main mass working parameters for the mass spectrometers were set as follows (see Supplemental Materials Table S1 for details): capillary voltage, 3 KV; cone voltage, 35 V; ion source temperature, 100°C; desolvation temperature, 350°C; cone gas flow, 50 l/h; desolvation temperature gas flow, 600 l/h. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using a MassLynx V4.1 software (Waters Corp, Milford, MA, USA).

Data Analysis

During the course of perfusion, conjugated wogonin or wogonoside was excreted into the intestinal lumen while pure aglycone was perfused, whereas pure aglycone or wogonin was excreted into the intestinal lumen while wogonoside was perfused. Permeability of the conjugated flavone and pure aglycone was represented by P*eff, which was obtained as described previously 22, 23. Briefly,

| 1 |

where Co and Cm are inlet and outlet concentrations corrected for water flux using the sample weight, respectively; while Gz, or Graetz number , is a scaling factor that incorporates flow rate (Q) and intestinal length (L), and diffusion coefficients (D) to make the permeability dimensionless.

Amounts of pure aglycone or conjugated flavone absorbed (Mab) and amounts of corresponding conjugated flavone or pure aglycone excreted into the intestinal lumen (Mmet) were calculated as described previously 3, 22. Generally, Mab was expressed as:

| 2 |

where τ is the sampling interval (30 min), and other parameters were the same as those defined in Equation (1). Amounts of metabolites (Mmet) were expressed as:

| 3 |

where Cmet is the outlet concentrations (nmol/l) of metabolites corrected for water flux. Hydrolysis rates of wogonoside by blank rat intestine perfusate, intestine S9 fractions and microbial enzymatic extract, were expressed as amounts of its aglycone formed (nmol) per min per mg protein (nmol/min/mg). Kinetic parameters were then obtained according to the standard Michaelis-Menten equation (Equation 4) since all Eadie-Hofstee plots were linear 22.

| 4 |

where Km is the Michaelis-Menten constant and Vmax is the maximum rate of glucuronidation.

Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA with or without Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison (posthoc) and/or Student’s t-test were used to evaluate differences between control and treatment; and differences were considered significant when p values were less than 0.05.

Results

Confirmation of Wogonin and Wogonoside Structure by LC-MS/MS

During perfusion of wogonin, wogonoside was found in the perfusate at fairly high concentration (more wogonosie than wogonin) (Fig.1A). Similarly, wogonin was also found in the perfusate when wogonoside was used to perfuse the rat intestine, albeit the amounts of metabolite found were relatively small (Fig.1B). The structure of the metabolite was confirmed by co-elution with authentic standards and with MS2 scan obtained from LC-MS/MS analysis (Fig.1D, 1E). The same two compounds were also found in the bile during perfusion, regardless wogonin or wogonoside was used for perfusion (See Supplement Information).

Absorption and Metabolism of Wogonin and Wogonoside

Wogonin and wogonoside were found to be converted to each other in the rat intestine (Fig.1 and Fig.2). Compared with wogonoside, wogonin was smaller and less polar, and therefore it penetrated the intestine more rapidly or with higher (about 10-fold) P*eff value.

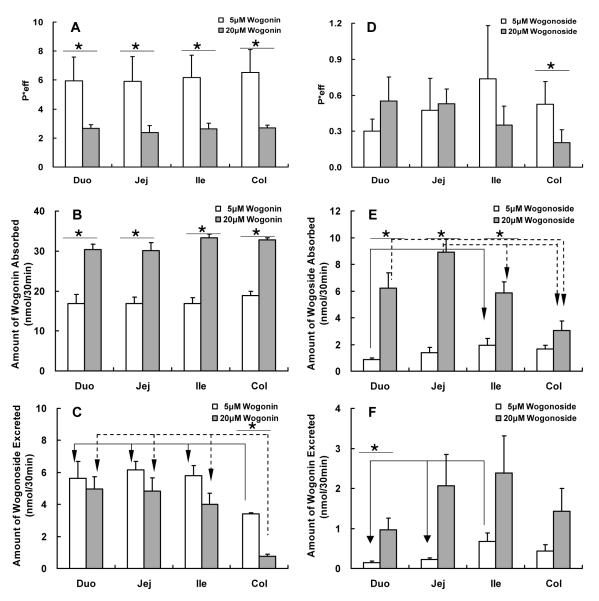

Fig. 2.

Effective intestinal permeability as well as absorption and metabolism of wogonin and wogonoside in a four-site rat intestinal perfusion model (number of replicates or n=4). Four segments of the intestine (i.e., duodenum, upper jejunum, terminal ileum, and colon) were perfused simultaneously at a flow rate of 0.168 ml/min using concentration of 5 μM (open columns) and 20 μM (solid columns). Effective permeabilities of wogonin (A), and amounts of wogonin absorbed (B) and wogonoside excreted (C) in 30 min interval were determined and normalized over a 5 cm intestinal length. Similarly, effective permeabilities of wogonoside (D), and amounts of wogonoside absorbed (E) and wogonin excreted (F) were also determined. Each column represents the average of four determinations, and the error bar is the S.E.M. The symbol “*” means the difference due to concentration change is significant (p<0.05, unpaired Student t-test), and the symbol “arrow” shows the significant difference between different segments of the intestine (p<0.05, one-way ANOVA with posthoc).

As expected, when wogonin or aglycone was perfused, it was well absorbed in all four segments of intestine, and its absorption showed no significant difference at different regions of the intestine at both 5 μM and 20 μM concentrations. Moreover, P*eff of wogonin at a concentration of 5 μM was significantly higher than that at 20 μM (Fig 2A). On the other hand, significant amounts of wogonoside were found in all four segments and the amounts formed was region-dependent, with excretion in colon significantly lower than that of the other 3 intestinal regions at both 5 μM and 20 μM concentrations (Fig.2C).

For wogonoside (i.e., wogonin-7-O-glucuronide), its absorption was slower in every intestine regions when compared to wogonin, but its absorption was similar in duodenum, jejunum, ileum, all of which were higher than those in the colon, at both 5 μM and 20 μM concentration (Fig.2E). Surprisingly, significant amounts of wogonin were recovered in the wogonoside perfusate at both 5 μM and 20 μM from the upper small intestine (Fig 2F), because β-glucuronidase was not known to hydrolyze flavonoid glucuronides there.

Chemical and Biological Stability of Wogonoside

To determine the reasons responsible for the previously observed surprising finding, chemical stability was determined. The results indicated that the wogonoside was chemically stable at pH 5.5, pH 6.5 and pH 7.4, with recovery in the range of 104%-106% after 8 h incubation at 37°C (See Supplement Information). Therefore, the surprising results shown in Fig.3 were not due to poor chemical stability of wogonoside.

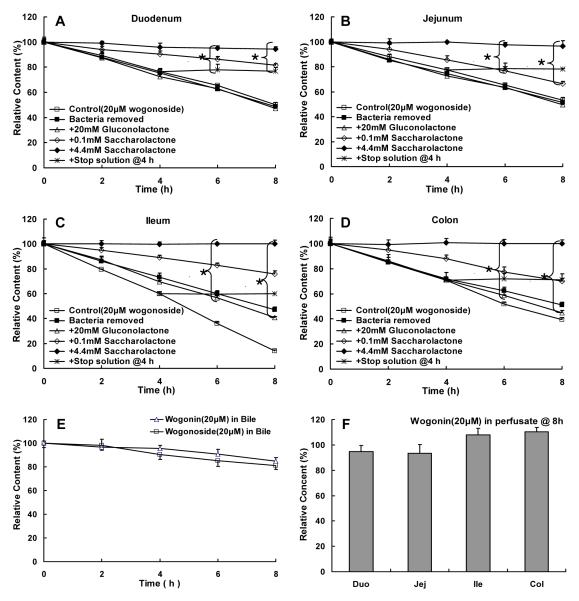

Fig.3.

Biological stability of wogonoside (20 μM) in blank intestinal perfusate of duodenum (A), jejunum (B), ileum (C), and colon (D) (n=3). Wogonoside was added into the intestinal perfusate and amounts of wogonoside were determined at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 h, and the rates of reaction were then calculated and used as the control group (□). Additional biological stability experiments were performed in the absence of bacteria (■), in the presence of 20 mM gluconolactone (▵), 0.1 mM saccharolactone (◇), or 4.4 mM saccharolactone (◆), respectively. Ability of a stop solution to stabilize 20 μM wogonoside was subsequently tested at 4, 6, 8, 24 h (*). Moreover, stability of 20 μM wogonoside was also determined in a 4-fold diluted bile solution (E), where stability of wogonin was determined in blank intestinal perfusate (F). All incubation experiments were performed at 37°C. Each data point is the average of three determinations and the error bar represents the standard deviation of the mean. The symbol “*{” means that there was a statistically significant difference in wogonoside content when compared to the control (p<0.05, one-way ANOVA with posthoc).

Next, a series of studies were conducted to determine the biological stability of wogonoside under different conditions. It was found that wogonoside was unstable in blank intestinal perfusate (generated by perfusing the HBSS buffer through ~10 cm segment of the small intestine) (control curve in Fig.3A-D), and the degradation (or hydrolysis) product was wogonin. The biological stability problem was found to be caused by the presence of β-glucuronidase in all intestinal perfusate since saccharolactone was found to inhibit the hydrolysis of wogonoside in all perfusate (saccharolactone curves in Fig.3A-D). In contrast, wogonoside was fairly stable in bile, and wogonin was very stable in the blank perfusate (Fig.3E-F). A stop solution (consisting of 94% acetonitrile and 6% glacial acetic acid) was then developed to ensure that wogonoside is stable after the samples were taken and the results indicated that addition of the stop solution at 4 h could stabilize wogonoside to 8 h (+stop solution curves in Fig.3A-D) and beyond (up to 24 h, not shown).

Lactasc phlorizin hydrolase (LPH) is a major contributor to the glucoside hydrolysis in the intestine and its contribution to glucuronide hydrolysis was unknown. The result demonstrated that it is probably not a main contributor to wogonoside’s biological instability since addition of gluconolactone, a specific inhibitor of the LPH, did not inhibit the hydrolysis of wogonoside (gluconolactone curve in Fig.3A-3D).

Bacteria are another major contributor to intestinal β-glucuronidase, so experiments were performed to determine the effects of the presence of bacteria. The results indicated that removal of bacteria via centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 30 min) and aseptic filtration did not improve stability of wogonoside (bacteria removed curve in Fig.3A-D). Further studies were then performed to further define the source of the β-glucuronidase (see later).

Effects of Glucuronidase Inhibitor (Saccharolactone) on Absorption and Metabolism of Wogonin and Wogonoside

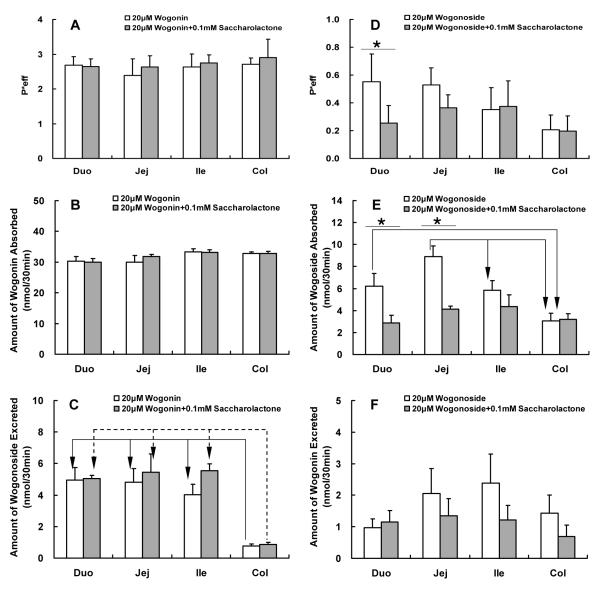

Glucuronidase inhibitor saccharolactone was used to inhibit the hydrolysis of wogonoside to wogonin in order to determine how this would impact the metabolism of either compound. As expected, saccharolactone did not affect the absorption or metabolism of wogonin (i.e., aglycone) but affected both absorption and metabolism of wogonoside (i.e., glucuronide) (Fig.4). Surprisingly, the effect on wogonoside absorption was more significant in the upper small intestine (Fig.4E) where the bacteria is absent or present at much lower quantities than those at the lower part of the small intestine (terminal ileum) and colon (see later).

Fig.4.

Effects of glucuronidase inhibitor saccharolactone on the absorption and metabolism of wogonin and wogonoside. Effective intestinal permeability as well as absorption and metabolism of wogonin and wogonoside were measured in “four site” perfused intestinal model using a flow rate of 0.168 ml/min. Flavonoids were perfused alone (open columns) or co-perfused with 0.1 mM saccharolactone (solid columns). Effective permeabilities of wogonin (A), and amounts of wogonin absorbed (B) and wogonoside excreted (C) in 30 min interval were determined and normalized over a 5 cm intestinal length. Similarly, effective permeabilities of wogonoside (D), and amounts of wogonoside absorbed (E) and wogonin excreted (F) were also determined. Each column represents the average of four determinations, and the error bar is the S.E.M. The symbol “*” means the difference due to concentration change is significant (p<0.05, unpaired Student t-test), and the symbol “arrow” shows the significant difference between different segments of the intestine (p<0.05, one-way ANOVA with posthoc).

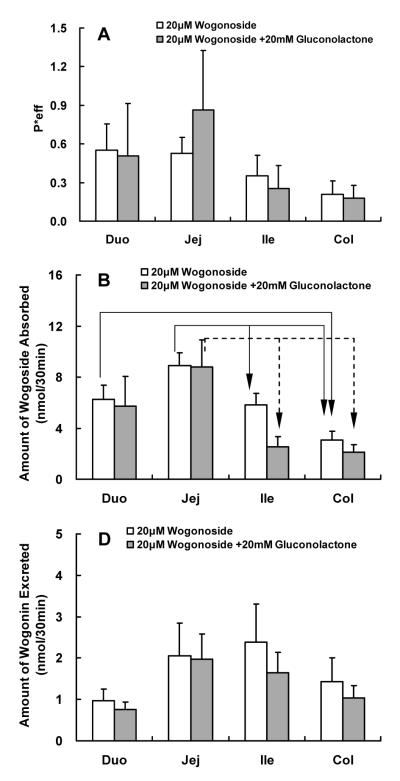

Effects of LPH Inhibitor (Gluconolactone) on Absorption and Metabolism of Wogonoside

Based on the results of the biological stability study, this LPH inhibitor was not expected to change the absorption or metabolism of wogonoside, and the results of the perfusion experiments demonstrated this point (Fig.5).

Fig.5.

Effects of LPH inhibitor gluconolactone on the absorption and metabolism of wogonin and wogonoside. Effective intestinal permeability as well as absorption and metabolism of wogonin and wogonoside were measured in “four site” perfused intestinal model using a flow rate of 0.168 ml/min. Flavonoids were perfused alone (open columns) or co-perfused with 20 mM gluconolactone (solid columns). Effective permeabilities of wogonoside (A), and amounts of wogonoside absorbed (B) and wogonin excreted (C) in 30 min interval were determined and normalized over a 5 cm intestinal length. Each column represents the average of four determinations, and the error bar is the S.E.M. The symbol “arrow” shows the significant difference between different segments of the intestine (p<0.05, one-way ANOVA with posthoc).

Effects of Antibiotic on Absorption and Metabolism of Wogonoside

Bacteria could have contributed to the hydrolysis of wogonoside and to determine its actual impact, an antibiotic mixture of penicillin and gentamicin was used to co-perfuse the rat intestine with wogonoside. The results indicated that the co-perfusion of antibiotics with wogonoside, which is equivalent to acute antibiotic treatment, did not impact absorption or metabolism of wogonoside (Fig.6).

Fig.6.

Effects of antibiotic on the absorption and metabolism of wogonin and wogonoside. Effective intestinal permeability as well as absorption and metabolism of wogonin and wogonoside were measured in “four site” perfused intestinal model using a flow rate of 0.168 ml/min. Flavonoids were perfused alone (open columns) or co-perfused with antibiotics (100 units penicillin and 0.1mg streptomycin/mL) (solid columns). Effective permeabilities of wogonoside (A), and amounts of wogonoside absorbed (B) and wogonin excreted (C) in 30 min interval were determined and normalized over a 5 cm intestinal length. Each column represents the average of four determinations, and the error bar is the S.E.M. The symbol “arrow” shows the significant difference between different segments of the intestine (p<0.05, one-way ANOVA with posthoc).

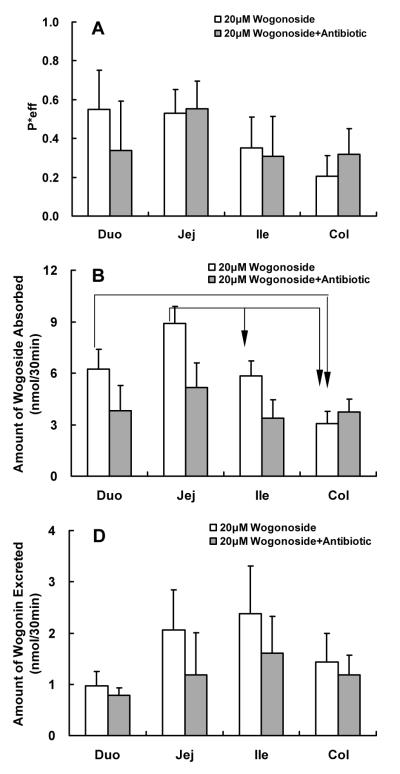

Determination of β-Glucuronidase Source in the Intestinal Perfusate

Since the prior study clearly implicated the role of β-glucuronidase in the intestinal absorption and metabolism of wogonoside, additional studies were conducted to determine the source of this enzyme in the gut and perfusate.

The most obvious source of β-glucuronidase is intestinal microflora, and therefore a series of studies were run to determine if intestinal microflora supplied the β-glucuronidase responsible for the hydrolysis of wogonoside during perfusion experiments. It was hypothesized that if bacteria were the main source, the amounts of bacteria present in various perfusate samples would correlate with the amounts of bacteria present in these samples. Therefore, sequential perfusate samples were collected from all four regions, after every segment was washed as those would be done during a normal perfusion experiment, and amount of bacteria in every sample was determined and then plotted against hydrolysis reaction rates measured using 20 μM wogonoside. The results indicated that there was no correlation between the numbers of bacteria present in the perfusate and rate of wogonoside hydrolysis (Fig.7A). We also selected four perfusate samples with drastically different amounts of bacteria (difference of greater than 2,700-fold), and found that 90-120 min jejunal perfusate sample had the highest Vmax value even though it has the lowest bacteria count (Fig.7B, Table 1). In contrast, 60-90 min colon perfusate sample with the highest bacteria count had the lowest Vmax value (Fig.7B, Table 1).

Fig.7.

Effects of bacteria counts on the hydrolysis rates of wogonoside. Panel A displayed the relationship between bacteria counts (●) in blank intestinal perfusate and hydrolysis rates of 20 μM wogonoside (▴). The blank rat intestinal perfusate was collected at a 30 min interval from duodenum, upper jejunum, terminal ileum and colon, respectively. The periods of collecting samples were expressed with number as follows: 0, 0-30min; 1, 30-60min; 2, 60-90min; 3, 90-120min; 4, 120-150min. Additional hydrolysis studies were conducted to determine the effects of bacteria count (B), perfused intestinal region (C), and sample collection time (D) on kinetic profiles and parameters (see also Table 1). For kinetic studies, hydrolysis rates were determined using substrate concentrations ranging from 1.25 to 160 μM and a reaction of 30 to 60 min to keep the %hydrolyzed below 30%. Each data point is the average of three determinations and the error bar represents the standard deviation of the mean. The curves in Fig.7C-D were generated based on fitted parameters using the Michaelis-Menten equation.

Table 1.

Apparent kinetic parameters of wogonoside hydrolysis by various blank intestinal perfusate, S9 fractions derived from rat duodenum, jejunum and ileum, as well as microbial enzymatic extract. All the kinetic parameters were obtained based on curve fitting using the classical Michaelis-Menten model, as described in “Materials and Methods” section

| Sample | Vmax( nmol/min/mg ) | Km(μM) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perfusate Duo 60-90min | 0.15 | 19.88 | 0.995 |

| Perfusate Jej 0-30min | 1.84 | 19.82 | 0.998 |

| Perfusate Jej 30-60min | 0.93 | 15.79 | 0.998 |

| Perfusate Jej 60-90min | 0.47 | 18.72 | 0.998 |

| Perfusate Jej 90-120min | 0.37 | 16.99 | 0.998 |

| Perfusate Jej 120-150min | 0.18 | 25.53 | 0.998 |

| Perfusate Ile 60-90min | 0.85 | 6.33 | 0.997 |

| Perfusate Ile 120-150min | 0.30 | 6.96 | 0.998 |

| Perfusate Col 60-90min | 0.15 | 19.74 | 0.998 |

| Duo S9 fraction | 2.06 | 29.99 | 0.998 |

| Jeu S9 fraction | 1.68 | 28.21 | 0.995 |

| Ile S9 fraction | 0.26 | 25.71 | 0.999 |

| Microflora enzymatic extract | 49.64 | 7.704 | 0.992 |

The above results showed that samples with higher bacteria count did not have faster hydrolysis rates. To confirm this finding, we also determine the metabolism of wogonoside in different perfusate collected at the same time, and the results again indicated that samples with the highest bacteria count (colon) did not have faster hydrolysis rates (Fig.7C). However, the amounts of enzyme (as represented by the Vmax values, Table 1) present in the perfusate appeared to decrease with time, indicating amount of enzymes present in the perfusate was less after continuous single-pass perfusion (Fig.7D).

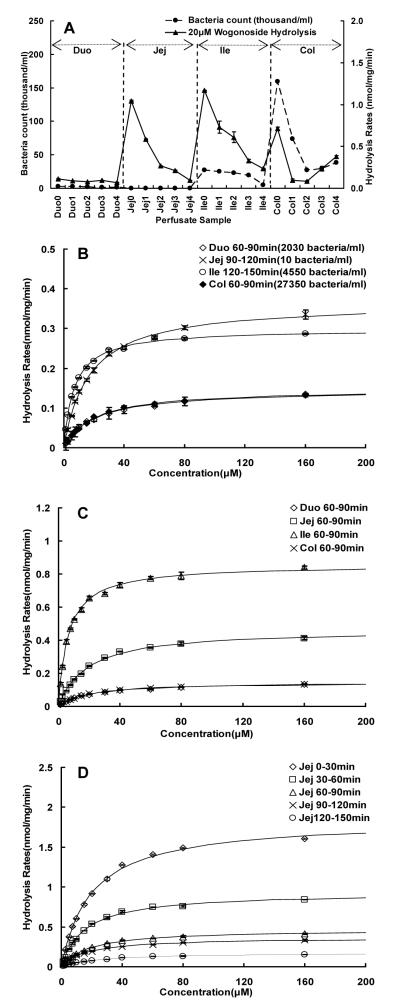

To determine if protein concentration in the perfusate could correlate with the hydrolysis activities, the amounts of protein in the perfusate were plotted against hydrolysis rates, and surprisingly, there was no correlation either (Fig.8A). In addition, we found that protein concentration did not decrease with perfusion time, indicating that protein in the perfusate may be due to sloughing off from the enterocytes or mucus or both. Lastly, there was no correlation between bacteria counts and protein concentration in the perfusate (Fig.8B).

Fig.8.

The relationships between protein concentrations (□) and 20 μM wogonoside hydrolysis rates (▴) (A), and between protein concentrations (□) and bacteria counts (●) (B) in various intestinal perfusate, as described in Fig.7A. Each data point is the average of three determinations and the error bar represents the standard deviation of the mean.

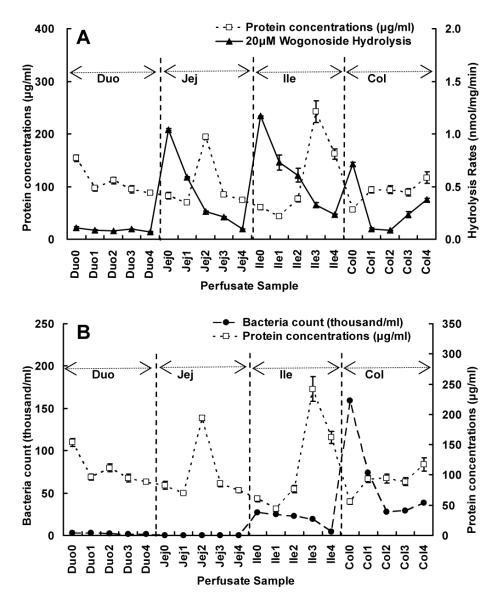

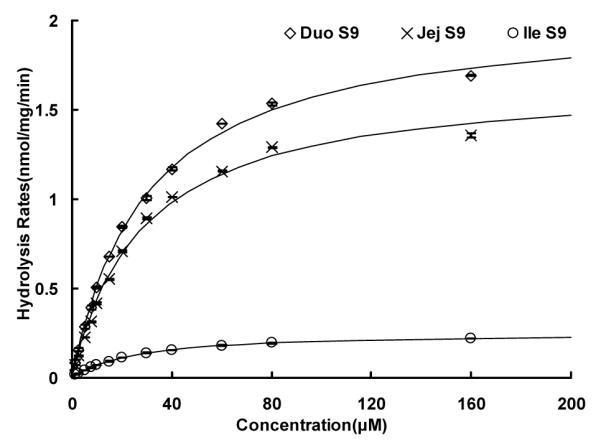

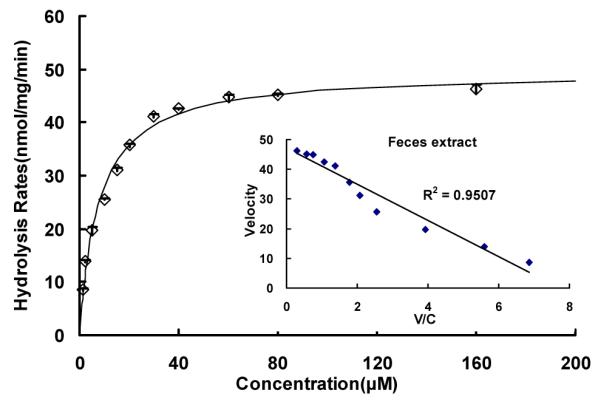

Because of the lack of commercial monoclonal antibody to distinguish bacteria β-glucuronidase from mammalian one, kinetic parameters were used to distinguish them functionally. To do so, the kinetic parameters were first determined and Eadie-Hofstee plots were generated for β-glucuronidase derived from intestinal S9 fraction (Fig.9), microbial enzymatic extract, (Fig.10), and perfusate samples (Fig.7, Table 1). The results indicated that enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis of wogonoside in different sample matrices all followed a classic Michaelis-Menten kinetic profile (as signified by the linear Eadie-Hofstee plots in Fig.3 of Supplement Materials). The Km values of intestinal S9 fractions from all three small intestinal segment were similar (25-30 μM, Table 1), but they were significantly higher than those derived from microbial enzymatic extract (7.7 μM, Table 1). When comparing to the Km values derived from the intestinal perfusate samples (15.8-25.6 μM, Table 1), they were all close to the Km values derived from the intestinal S9 fractions, except for two terminal ileal perfusate samples, which displayed Km values (6.3-6.9 μM, Table 1) closely resembled that of the microbial enzymatic extract.

Fig.9.

Kinetics of wogonoside hydrolysis by intestine S9 fractions pooled from three rats’ duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, respectively. Hydrolysis rates were determined using substrate concentrations ranging from 1.25 to 160 μM, and reaction time was 30 or 60 min. Each data point is the average of three determinations and the error bar represents the standard deviation of the mean. The curve was generated based on fitted parameters using the Michaelis-Menten equation. The apparent kinetic parameters were listed in Table 1.

Fig.10.

Kinetics of wogonoside hydrolysis by microflora enzymatic extract pooled from three rats’ fresh-collected feces. Hydrolysis rates were determined using substrate concentrations ranging from 1.25 to 160 μM, and reaction time was 30 or 60 min. Each data point is the average of three determinations and the error bar represents the standard deviation of the mean. The curve was generated based on fitted parameters using the Michaelis-Menten equation. The apparent kinetic parameters were listed in Table 1.

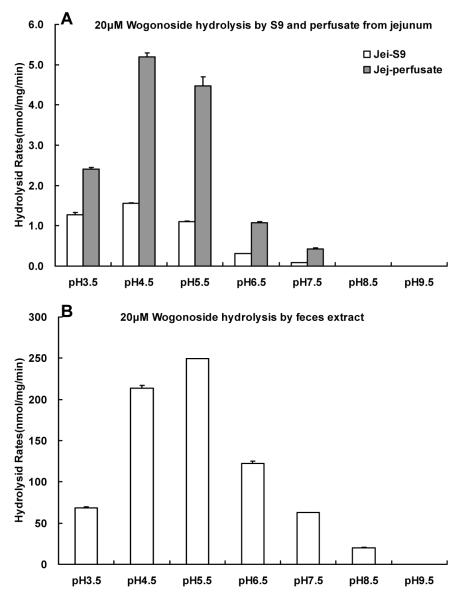

To investigate the source of the β-glucuronidase that drives the wogonoside hydrolysis in the perfusate, S9 fraction of jejunum, blank jejunal perfusate and supernatant of fecal extract were used to determine their pH-activity profiles. We found the optimal activities of glucuronidases present in the blank perfusate and S9 fraction from jejunum were obtained the same (pH 4.5), but the actual maximal rates were different (5.195±0.103 for S9 fraction, 1.559±0.008 nmol/min/mg for blank perfusate) (Fig.11). For the fecal extract, the highest hydrolysis rate was at pH 5.5, and the hydrolysis rate was 249.211±0.178 nmol/min/mg. The results suggest that β-glucuronidase in perfusate and S9 fractions from jejunum may be from the same source, whereas those found in the fecal extract may be derived from a different source.

Fig.11.

Hydrolysis rates of wogonoside (20μM) in the jejunal S9 fraction and blank jejunal perfusate as well as in fecal extract under different pH values. Experiments were conducted at the following pHs: 3.5, 4.5, 5.5, 6.5, 7.5, 8.5, 9.5. The reactions were proceeded at 37°C for 30 min, and stopped by the addition of 0.5 ml of 94% acetonitrile / 6% glacial acetic acid containing 90 μM acetophenone as the internal standard. The reaction mixture was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min and the supernatant was subjected to UPLC for analysis.

Discussion

The results of this investigation showed for the first time that flavonoid could undergo local recycling, where action of bacteria is not essential for the recycling of this class of important dietary chemicals, many of which have important chemopreventive activities. In fact, this is the first instance in the literature such local recycling of any xenobiotic could occur in appreciable (i.e., measurable) extents in the small intestine, although recycling in the large intestine involving bacterial β-glucuronidase was already implicated because of the action of microflora 24. We were quite surprised that glucuronide can be rigorously hydrolyzed by enterocyte-derived β-glucuronidase, since there is no report in the literatures that such action of glucuronidase may exist outside of the enterocytes. It was commonly assumed that any hydrolysis of glucuronides in the gut came from bacteria-derived β-glucuronidase.

Our conclusion that flavonoid glucuronides can be recycled locally was well-supported by the following results. First, wogonoside was rapidly hydrolyzed into wogonin (Fig.2F), which was then rapidly absorbed. Second, the hydrolysis was driven by β-glucuronidase since hydrolysis in the blank perfusate was inhibited by saccharolactone (Fig.3). In addition, co-perfusion with a β-glucuronidase inhibitor saccharolactone significantly decreased the absorption of wogonoside (Fig.4) whereas co-perfusion with gluconolactone (a lactase phlorizin hydrolase inhibitor) or antibiotics did not affect its absorption (Fig.5 and Fig.6). Third, the β-glucuronidase activities were mediated by enteric β-glucuronidase since the activities were higher in the upper small intestine (i.e., jejunum) than in colon, although the latter has the highest count of bacteria in the blank perfusate collected from different regions of the intestine (Fig.7A). Additionally, the β-glucuronidase activities were higher in upper small intestinal blank perfusate (Fig.7B) and that the Km values of hydrolysis reaction in duodenal and jejunal blank perfusate were nearly identical to those of their intestinal S9 fraction, respectively (Table 1). Their kinetic profiles were also very similar as shown by both regular concentration versus rate plots (Fig.7B-D, Fig.9) and Eadie-Hofstee plots (see Supplement Materials).

Local recycling of flavonoid glucuronides may have significant impact on the biological activities of flavonoids, especially in the gut. This is because local recycling clearly will prolong the residence time of flavonoids in the gut. Since flavonoids are good anti-oxidants regardless if they are glucuronidated 25, 26, this local recycling function allows the flavonoids to have good exposure locally even though flavonoids usually have poor systemic bioavailabilities 1, 27, 28. Considering a myriad of activities possessed by flavonoids, including anticancer and anti-inflammation, these results suggest that flavonoids that undergo local recycling may have much more biological activities in the gut than predicted based on their systemic bioavailability. Indeed, wogonin recycling could have been the reason why herbs containing high concentration of wogonin (e.g., roots of Scutellaria baicalensis) are routinely used to protect gastrointestinal tract in traditional Chinese medicine 29.

Local recycling could explain the pharmacokinetic profiles and even pharmacodynamic and toxicological effects of drugs and dietary chemicals that also undergo extensive intestinal glucuronidation. The drugs may include raloxifene, ezetimibe and SN-38, all of which are extensively glucuronidated in the gut. For ezetimibe, whose glucuronide is more bioactive than the parent 30, 31, local recycling means longer duration of action and higher activities than predicted based on its systemic blood level. For raloxifene, whose glucuronide is less bioactive or inactive, local recycling means longer half-life 32, 33 resulting from substantial recycling that involves all three distinctive mechanisms: enterohepatic, enteric and local recycling. For SN-38, local recycling means toxicity in the upper small intestine 34, 35, which could not be fully explained by using only enterohepatic and enteric recycling that requires bacteria β-glucuronidase for releasing toxic aglycone. For dietary chemicals that include flavonoids such as wogonin and other classes of phenolic compounds such as resveratrol, a phenolic stilbene that is extensively glucuronidated in the gut 36 , local recycling means better local activities and this recycling action along with enterohepatic and enteric recycling schemes translate into longer apparent half-life than expected from a poorly bioavailable (<5%) compound 37.

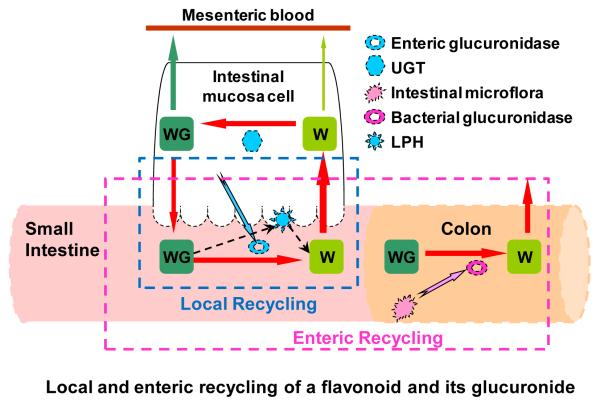

Local recycling described here is different from enteric recycling coined previously by us 3. In enteric recycling, the action of both enteric enzymes (i.e., UGTs and SULTs) and microbial β-glucuronidases are necessary, and because enzyme activities of UGTs and SULTs are usually much higher in the small intestine, and that of the β-glucuronidases are usually much higher in the large intestine, recycling is completed over the entire intestine (Fig. 12). In local recycling, the action of microbial β-glucuronidases is not needed, so recycling could complete in the small intestine (Fig. 12). Both enteric and local recycling differs from enterohepatic recycling in that the action of hepatic enzymes and efflux transporters are not required. Hepatic enzymes and efflux transporters enable the phase II metabolism of their substrates and subsequent excretion of phase II conjugates via bile. In humans, recycling via any or all three mechanisms could all extend the apparent half-life of an aglycone and its conjugates. Because human bile is emptied as a bolus (as a response to food ingestion, for example), an aglycone and its metabolite will often exhibit a second peak following a meal, which is often called a “double peak” phenomenon. For enteric and local recycling, the second peak may not occur since this excretion of phase II conjugates is continuous, not as a bolus.

Fig.12.

Diagram of local recycling of wogonoside and wogonin: WG, wogonoside; W, wogonin; GUS, β-glucuronidase; UGT, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase. Hydrolytic enzyme excretion pathway from enterocytes/bacteria was marked with blue/pink arrow(s), and hydrolysis pathway was signified with dashed black arrow. The local recycling only need the involvement of players enclosed in the dashed blue box, whereas enteric recycling need the involvement of players enclosed in the dashed purple box. Within the local recycling, the involvement of bacterial glucuronidase is not essential, whereas for enteric recycling, bacterial glucuronidase is considered to be essential.

Local recycling could occur independent of the other recycling processes or as a part of the other two recycling processes, depending on an aglycone absorption and metabolism characterisitcs. For example, an aglycone at high concentration is very rapidly absorbed (saturating the metabolism in the gut) and is predominantly metabolized in the liver so local recycling was not predominant during first-pass. But conjugated metabolites that are present in the lumen as the result of biliary excretion could then participate in local recycling since conjugates are not going to be rapidly absorbed in the small intestine until it is first hydrolyzed by the enteric glucuronidases. For another aglycone that is absorbed and extensively metabolized (with metabolite then rapidly excreted) in the gut, the excreted metabolites could be hydrolyzed back to aglycone and re-enter the intestine, completing the cycle without the involvement of the other recycling mechanisms. We are planning additional studies to sort out these mechanisms, and we also hope that our studies will serve as the impetus for other scientists to get involved in the study of the importance of the local recycling mechanism.

In conclusion, we have discovered a novel local recycling mechanism that will significantly enhance the local bioavailability and residence time of flavonoids such as wogonin. This local recycling mechanism has the potential to significantly impact the bioavailabilities of other drugs and dietary chemicals that also undergo extensive glucuronidation in the gut. Because a large numbers of phenolics are glucuronidated significantly in gut, this newly discover recycling mechanism should have a significant physiological role in governing the local bioavailability and residence time of phenolics, which may ultimate impact the pharmacodynamic and toxicological effects of this class of important compounds, many of which are showing promise as chemopreventive agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Yunchang Qiu and Ms Lijun Zhu of School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Southern Medical University for their help in bacteria culture experiments. The authors would like to acknowledge Juan Zhou, Ya Li, and Chang Lv for their help in animal experiments.

This work was supported in part by the Key International Joint Research Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81120108025), the Key Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China (U0832002) to ZQL, and in part by The National Institutes of Health grant GM-70737 to MH.

Abbreviations Used

- UGT

UDP-glucuronosyltransferase

- LPH

Lactasc phlorizin hydrolases

- GUS

glucuronidase

- HBSS

Hank’s balanced salt solution

Footnotes

Authorship Contributions: Participated in research design: Zhongqiu Liu, Ming Hu and Bijun Xia Conducted experiments: Bijun Xia, Qiong Zhou, Zhijie Zheng and Lin Ye Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Bijun Xia, Zhijie Zheng and Lin Ye Performed data analysis: Bijun Xia, Qiong Zhou

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Ming Hu, Zhongqiu Liu and Bijun Xia Other: Zhongqiu Liu and Ming Hu acquired funding for the research.

References

- 1.Hu M. Commentary: bioavailability of flavonoids and polyphenols: call to arms. Mol Pharm. 2007;4(6):803–6. doi: 10.1021/mp7001363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manwaring WH. Enterohepatic Circulation of Estrogens. Cal West Med. 1943;59(5):257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Lin H, Hu M. Metabolism of flavonoids via enteric recycling: role of intestinal disposition. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304(3):1228–35. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai JY, Yang JL, Li C. Transport and metabolism of flavonoids from Chinese herbal remedy Xiaochaihutang across human intestinal Caco-2 cell monolayers. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29(9):1086–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YH, Jeong DW, Kim YC, Sohn DH, Park ES, Lee HS. Pharmacokinetics of baicalein, baicalin and wogonin after oral administration of a standardized extract of Scutellaria baicalensis, PF-2405 in rats. Arch Pharm Res. 2007;30(2):260–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02977703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fas SC, Baumann S, Zhu JY, Giaisi M, Treiber MK, Mahlknecht U, Krammer PH, Li-Weber M. Wogonin sensitizes resistant malignant cells to TNFalpha- and TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Blood. 2006;108(12):3700–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-011973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rushworth SA, Micheau O. Molecular crosstalk between TRAIL and natural antioxidants in the treatment of cancer. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157(7):1186–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee DH, Kim C, Zhang L, Lee YJ. Role of p53, PUMA, and Bax in wogonin-induced apoptosis in human cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75(10):2020–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee DH, Rhee JG, Lee YJ. Reactive oxygen species up-regulate p53 and Puma; a possible mechanism for apoptosis during combined treatment with TRAIL and wogonin. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157(7):1189–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rugo H, Shtivelman E, Perez A, Vogel C, Franco S, Tan Chiu E, Melisko M, Tagliaferri M, Cohen I, Shoemaker M, Tran Z, Tripathy D. Phase I trial and antitumor effects of BZL101 for patients with advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;105(1):17–28. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawashima K, Nomura A, Makino T, Saito K, Kano Y. Pharmacological properties of traditional medicine (XXIX): effect of Hange-shashin-to and the combinations of its herbal constituents on rat experimental colitis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27(10):1599–603. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed-Belkacem A, Ahnou N, Barbotte L, Wychowski C, Pallier C, Brillet R, Pohl RT, Pawlotsky JM. Silibinin and Related Compounds Are Direct Inhibitors of Hepatitis C Virus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase. Gastroenterology. 2009 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferenci P, Scherzer TM, Kerschner H, Rutter K, Beinhardt S, Hofer H, Schoniger-Hekele M, Holzmann H, Steindl-Munda P. Silibinin is a potent antiviral agent in patients with chronic hepatitis C not responding to pegylated interferon/ribavirin therapy. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(5):1561–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polyak SJ, Morishima C, Shuhart MC, Wang CC, Liu Y, Lee DY. Inhibition of T-cell inflammatory cytokines, hepatocyte NF-kappaB signaling, and HCV infection by standardized Silymarin. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(5):1925–36. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sukhthankar M, Yamaguchi K, Lee SH, McEntee MF, Eling TE, Hara Y, Baek SJ. A green tea component suppresses posttranslational expression of basic fibroblast growth factor in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(7):1972–80. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jia X, Chen J, Lin H, Hu M. Disposition of flavonoids via enteric recycling: enzyme-transporter coupling affects metabolism of biochanin A and formononetin and excretion of their phase II conjugates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310(3):1103–13. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.068403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin YT, Hsiu SL, Hou YC, Chen HY, Chao PD. Degradation of flavonoid aglycones by rabbit, rat and human fecal flora. Biol Pharm Bull. 2003;26(5):747–51. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Comparison of Coomassie Brilliant Blue protein dye-binding assays for determination of urinary protein concentration. 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ausbubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, K, S. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Vol 1. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1988. pp. 1.3.1–4.pp. 1 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yi JH, Ni RY, Luo DD, Li SL. Intestinal flora translocation and overgrowth in upper gastrointestinal tract induced by hepatic failure. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5(4):327–329. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v5.i4.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.China Parmacopeia,2005. Appendix XI J. second edition. 2005. pp. 93–5. the.

- 22.Wang SW, Chen J, Jia X, Tam VH, Hu M. Disposition of flavonoids via enteric recycling: structural effects and lack of correlations between in vitro and in situ metabolic properties. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34(11):1837–48. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.009910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Liu Y, Dai Y, Xun L, Hu M. Enteric disposition and recycling of flavonoids and ginkgo flavonoids. J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9(5):631–40. doi: 10.1089/107555303322524481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Z, Hu M. Natural polyphenol disposition via coupled metabolic pathways. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2007;3(3):389–406. doi: 10.1517/17425255.3.3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terao J. Dietary flavonoids as antioxidants in vivo: conjugated metabolites of (−)-epicatechin and quercetin participate in antioxidative defense in blood plasma. J Med Invest. 1999;46(3-4):159–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto N, Moon JH, Tsushida T, Nagao A, Terao J. Inhibitory effect of quercetin metabolites and their related derivatives on copper ion-induced lipid peroxidation in human low-density lipoprotein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;372(2):347–54. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeong EJ, Liu X, Jia X, Chen J, Hu M. Coupling of conjugating enzymes and efflux transporters: impact on bioavailability and drug interactions. Curr Drug Metab. 2005;6(5):455–68. doi: 10.2174/138920005774330657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L, Zuo Z, Lin G. Intestinal and hepatic glucuronidation of flavonoids. Mol Pharm. 2007;4(6):833–45. doi: 10.1021/mp700077z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolfson P, Hoffmann DL. An investigation into the efficacy of Scutellaria lateriflora in healthy volunteers. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(2):74–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghosal A, Hapangama N, Yuan Y, Achanfuo-Yeboah J, Iannucci R, Chowdhury S, Alton K, Patrick JE, Zbaida S. Identification of human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzyme(s) responsible for the glucuronidation of ezetimibe (Zetia) Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32(3):314–20. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kosoglou T, Statkevich P, Johnson-Levonas AO, Paolini JF, Bergman AJ, Alton KB. Ezetimibe: a review of its metabolism, pharmacokinetics and drug interactions. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44(5):467–94. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeong EJ, Liu Y, Lin H, Hu M. Species- and disposition model-dependent metabolism of raloxifene in gut and liver: role of ugt1a10. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33(6):785–94. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.001883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levi MS, Borne RF, Williamson JS. A review of cancer chemopreventive agents. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8(11):1349–62. doi: 10.2174/0929867013372229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Logan RM, Gibson RJ, Bowen JM, Stringer AM, Sonis ST, Keefe DM. Characterisation of mucosal changes in the alimentary tract following administration of irinotecan: implications for the pathobiology of mucositis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;62(1):33–41. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagano T, Yasunaga M, Goto K, Kenmotsu H, Koga Y, Kuroda J, Nishimura Y, Sugino T, Nishiwaki Y, Matsumura Y. Antitumor activity of NK012 combined with cisplatin against small cell lung cancer and intestinal mucosal changes in tumor-bearing mouse after treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(13):4348–55. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brill SS, Furimsky AM, Ho MN, Furniss MJ, Li Y, Green AG, Bradford WW, Green CE, Kapetanovic IM, Iyer LV. Glucuronidation of trans-resveratrol by human liver and intestinal microsomes and UGT isoforms. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2006;58(4):469–79. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.4.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walle T, Hsieh F, DeLegge MH, Oatis JE, Jr., Walle UK. High absorption but very low bioavailability of oral resveratrol in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32(12):1377–82. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.000885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.