Abstract

The multistep continuous flow assembly of 2-(1H-indol-3-yl)thiazoles using a Syrris AFRICA® synthesis station is reported. Sequential Hantzsch thiazole synthesis, deketalization and Fischer indole synthesis provides rapid and efficient access to highly functionalized, pharmacologically significant 2-(1H-indol-3-yl)thiazoles. These complex, drug-like small molecules are generated in reaction times of less than 15 min and in high yields (38%–82% over three chemical steps without isolation of intermediates).

Keywords: heterocycles, indoles, condensation, tandem reaction, microreactors, microfluidic synthesis

The interaction of small molecule compounds with specific human proteins, such as enzymes, receptors or ion channels, is one of the fundamental principles upon which the discovery of new medicines is based. Advantages of low molecular weight drugs include the potential for oral bioavailability, efficient tissue (e.g. brain) penetration and low cost of manufacture, among others. The vast majority of low molecular weight drugs are heterocyclic compounds, often comprising several connected heterocyclic rings. This is not surprising considering the propensity of heteroatoms within drug scaffolds to form reversible interactions (electrostatic, H-bonds etc.) within the active sites of proteins, thereby exerting a modulatory effect. High-throughput screening is one of the most common and effective methods to identify small molecule compounds with activity against the target protein of interest. Invariably, however, the initial hit structure identified in a screening campaign exhibits relatively low potency and selectivity for the target protein, in addition to sub-optimal physicochemical (drug-like) properties. Therefore, the development of new synthetic chemistry methods for the rapid and efficient generation of analogues for in vitro testing is critical for the hit-to-lead optimization of screening hits.1–8 Accordingly, we have established a research program focused on developing automated flow chemistry methods to rapidly access complex, drug-like compounds from readily available precursors. More specifically, we are developing highly efficient flow chemistry methods that combine multiple chemical transformations into single, continuous processes. Advantages of this technology include optimal heat transfer, enhanced reagent mixing, precise reaction times, small reaction volumes, and the ability to conduct multistep reactions in a single, unbroken microreactor sequence.9 Thus, flow processes are safe, environmentally friendly and cost effective on a manufacturing scale. To demonstrate the utility of flow synthesis we have previously reported the continuous flow preparation of bis-substituted 1,2,4-oxadiazoles,5 functionalized imidazo[1,2-a] heterocycles,6 pyrrole-3-carboxylic acid derivatives,7 and 5-(thiazol-2-yl)-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones.8 We now report methodology for consecutive heterocycle formation reactions to access 2-(1H-indol-3-yl)thiazoles, privileged scaffolds with demonstrated biological activity, using an uninterrupted continuous flow microreactor sequence. In this unique continuous process, sequential thiazole formation, deketalization and Fischer indole synthesis provides rapid and efficient access to novel 2-(1H-indol-3-yl)thiazole (indolylthiazole) derivatives 1. These structures, which are generated from β-ketothiazoles 2 and prepared thioamide 3 (Figure 1), are formed cleanly and without isolation of intermediates.

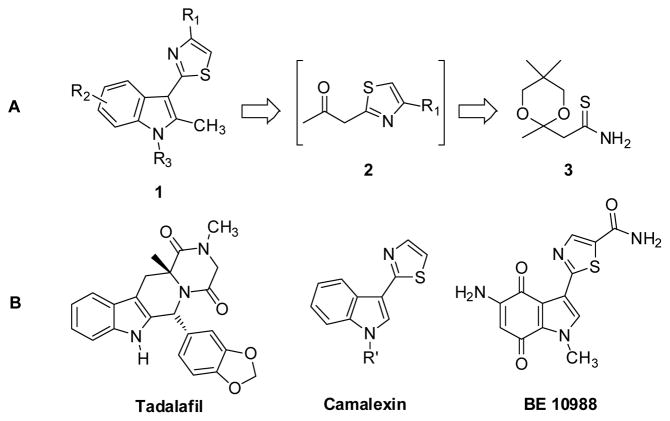

Figure 1.

(a) Indolylthiazoles 1 from intermediate β-ketothiazoles 2 and prepared thioamide 3. (b) Marketed indole Tadalafil and biologically active natural products camalexin and BE 10988.

Indoles constitute a ubiquitous structural motif present in a broad range of biologically active small molecules and natural products. These heterocycles are present in investigational and approved drugs such as Tadalafil, an inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) (Figure 1).10 Tadalafil is currently indicated for the treatment of both erectile dysfunction (Cialis®) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (Adcirca®). Indolylthiazole derivatives also constitute a large family of medicinally significant compounds displaying a wide range of pharmacological properties. For example, the camalexin class of natural products has received much attention in recent years because of both its antifungal and antiviral activity (Figure 1).11 In addition, closely related thiazolyl indolequinones, such as the natural product BE 10988, have been identified as potent topoisomerase II inhibitors and have consequently been shown to possess promising anticancer activity (Figure 1).12 Due to this broad spectrum of therapeutic areas, methods for the high-throughput synthesis of connected heterocyclic derivatives, like the indolylthiazoles, are of significant interest.

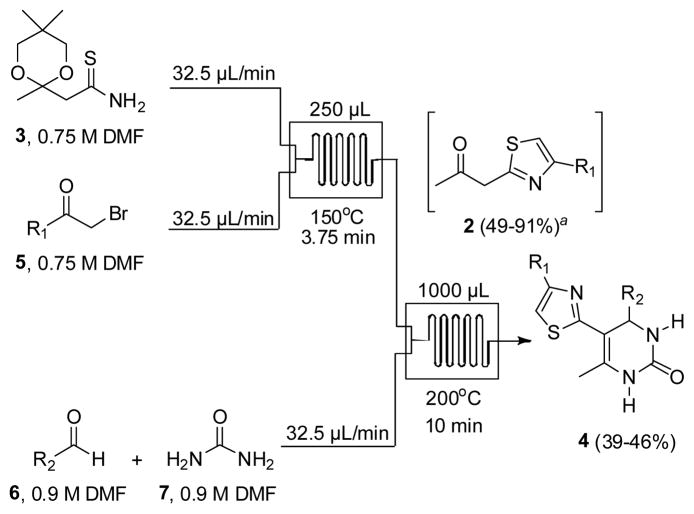

Although continuous flow methods for the synthesis of simple indoles have been reported separately by Watts13 and Seeberger14, the inspiration for our multistep flow assembly of indolylthiazoles 1 stems from our recently reported synthesis of 5-(thiazol-2-yl)-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones 4 (Scheme 1).8 In this method, intermediate β-ketothiazoles 2 from ketal-protected thioamide 3 provided access to a novel class of connected heterocycles in high yield (39–46%) over three chemical steps. This automated process comprised Hantzsch thiazole synthesis of thioamide 3 with α-bromoketones 5 liberating molar equivalents of HBr and water, triggering removal of the 1,3-dioxane protecting group to generate intermediate β-ketothiazoles 2. The released acid was then further utilized to catalyze the subsequent Biginelli multicomponent reaction with aldehydes 6 and urea 7. Knowing that the Fischer indole synthesis is also promoted with acid, we hypothesized that replacement of the aldehyde and urea components with hydrazines would provide a viable route to the 2-(1H-indol-3-yl)thiazole core (1).

Scheme 1.

Microfluidic Synthesis of 5-(thiazol-2-yl)-3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones 4. Yields for one-chip reactions determined using 5 min retention times and 1 equiv of water. Refer to Ref. 8 for complete details of this study.

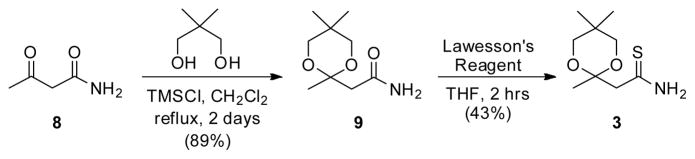

At the outset of our experiments, we prepared the ketal-protected thioamide 3 (Scheme 2) from commercially available acetoacetamide 8 in two steps. First, ketone 8 was heated at reflux in the presence of neopentyl glycol and chlorotrimethylsilane in anhydrous methylene chloride to furnish known ketal-protected amide 9 in excellent yield (89%).15 Then, compound 9 was carefully treated with just over one-half equivalent of Lawesson’s reagent at 0 °C in anhydrous THF to generate protected thioamide 3 in 43% yield. In our hands, the necessary ketone required a protecting group for acceptable thioamide production. This reaction process is amenable to scale-up procedures with crystalline 3 easily isolated by precipitation from toluene. Furthermore, this key building block can be stored at room temperature without significant decomposition and is stable in the DMF solutions used for all the microfluidic experiments described herein.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Thioamide 3.

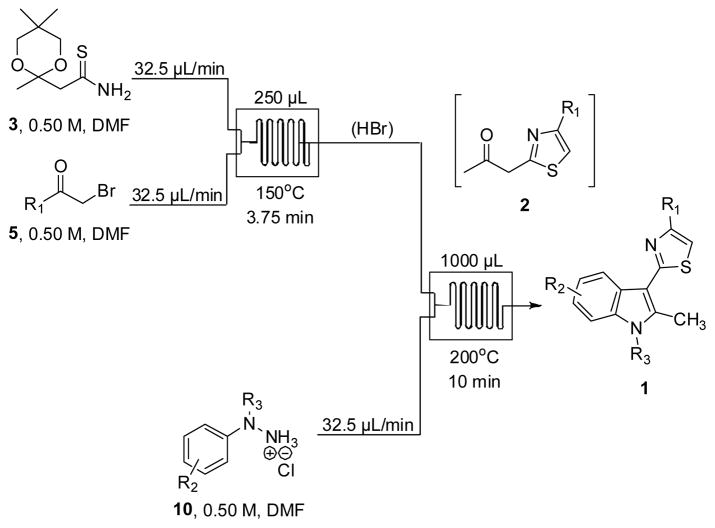

With freshly prepared thioamide 3 in hand, we next focused our efforts on using this building block for the microfluidic synthesis of indolylthiazoles 1 (Scheme 3). For this continuous multistep process, the setup is identical to that shown in Scheme 1 except that aldehydes 6 and urea 7 have now been exchanged for hydrazines 10. As with the Biginelli process, we envisioned that the liberated HBr utilized to unmask the ketone intermediates could be harnessed to catalyze the subsequent Fischer indole synthesis. Gratifyingly, we found that the two-chip flow synthesis of indolylthiazoles 1 proceeded efficiently under the conditions shown in Scheme 3. Initially, 0.50 M solutions of thioamide 3 and α-bromoketones 5 in DMF were pumped (32.5 μL/min) into a 250 μL reactor heated to 150 °C for 3.75 minutes.

Scheme 3.

Final Microfluidic Setup for the Synthesis of Indolylthiazoles 1.

This reaction concentration was chosen as a compromise between general solubility and theoretical yield for the sequence. The generated ketothiazole intermediate 2 was then introduced to a separate stream (32.5 μL/min) of hydrazine hydrochlorides 10 (0.50 M, DMF). The combined flow (97.5 μL/min) was pumped into a 1000 μL reactor heated to 200 °C. Overall, each continuous two-chip microfluidic sequence required less than one hour for completion from start to finish (injection, reaction, and 1000 μL collection).

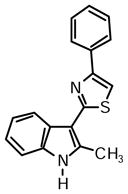

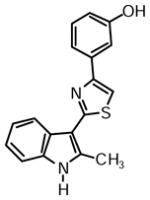

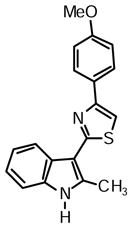

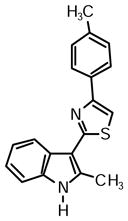

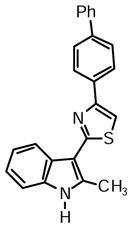

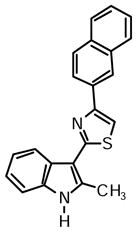

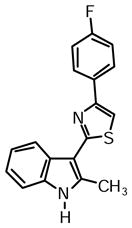

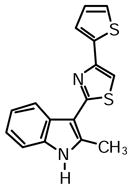

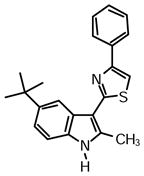

The multistep continuous flow synthesis of indolylthiazoles 1a–1l is presented in Table 1. For all entries (1–12), a DMF solution of phenylhydrazine hydrochloride (10a) was pumped into the second chip in order to study the reaction scope of α-bromoketones 5. The overall yields for the three-step, two-chip sequence were high (43%–65%) when using aromatic α-bromoketones 5, averaging at least 70% yield for each chemical transformation. Acetophenone substrates bearing either electron-donating (entries 2, 3 and 4), electron-withdrawing (entries 10 and 11), or halogen substitution (entries 7, 8 and 9) as well as 2-naphthyl (entry 6) and heteroaromatic (entry 12) were found to be suitable for this process. Importantly, these data largely represent the current supply of commercially available α-bromoketones, yielding complex drug-like compounds for extensive biological evaluation and/or continued chemistry.

Table 1.

Synthesis of Indolylthiazoles 1a–1l: Scope of α-Bromoketones

| entrya | product | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1, 1a |

|

50b |

| 2, 1b |

|

65 |

| 3, 1c |

|

49 |

| 4, 1d |

|

49 |

| 5, 1e |

|

44 |

| 6, 1f |

|

44 |

| 7, 1g |

|

49 |

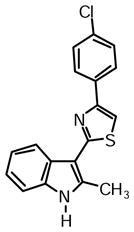

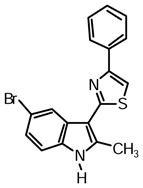

| 8, 1h |

|

46 |

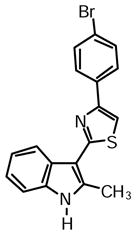

| 9, 1i |

|

46 |

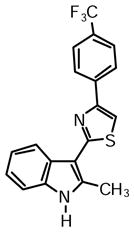

| 10, 1j |

|

43 |

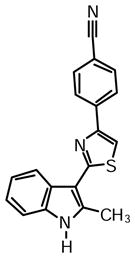

| 11, 1k |

|

48 |

| 12, 1l |

|

41 |

Refer to Supporting Information for structures of α-bromoketones 5a–5l.

Isolated yields based on 1000 μL collection volumes and following silica gel chromatography.

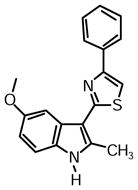

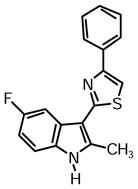

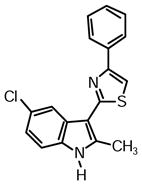

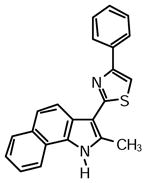

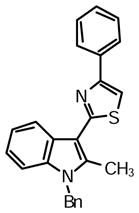

We next investigated the reaction scope of hydrazines 10 and the multistep continuous flow synthesis of indolylthiazoles 1m–1v is presented in Table 2. For all entries (1–10), a DMF solution of 2-bromoacetophenone (5a) was pumped into the first microreactor chip. The overall yields for the three-step, two-chip sequence were also high (38%–82%) when using hydrochloride and free base hydrazines, again averaging at least 70% yield for each chemical transformation. Hydrazine substrates bearing either electron-donating (entries 1 and 6), alkyl (entries 7 and 8), or halogen substitution (entries 2, 3 and 4) were found to be suitable for this process. While extended aromatic systems such as 1-naphthyl (entry 9) proceeded in excellent yield, hydrazine substrates bearing electron-withdrawing groups such as 4-cyano and 4-trifluoromethyl (not shown) failed to furnish sufficient quantities of desired indolylthiazole product for isolation. Not surprisingly, this reaction sequence also proved futile with batch-mode standard heating using an oil bath and longer reaction times. Importantly, nitrogen substituted hydrazines such as methyl and benzyl (entries 5 and 10) are also viable using this process. Since free base hydrazines are known to be unstable, freshly opened bottles were used for these experiments. It should also be noted that hydrazines 10a and 10b used to generate 1m and 1n, respectively, were not soluble in straight DMF and therefore stock solutions were prepared in 1:1 DMF:ethylene glycol.

Table 2.

Synthesis of Indolylthiazoles 1m–1v: Scope of Hydrazines

| entrya | product | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|

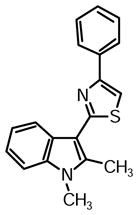

| 1, 1m |

|

51b |

| 2, 1n |

|

47 |

| 3, 1o |

|

54 |

| 4, 1p |

|

44 |

| 5, 1q |

|

63c |

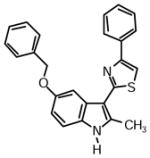

| 6, 1r |

|

38 |

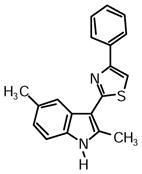

| 7, 1s |

|

57 |

| 8, 1t |

|

53 |

| 9, 1u |

|

82 |

| 10, 1v |

|

44c |

Refer to Supporting Information for structures of hydrazines 10a–10j.

Isolated yields based on 1000 μL collection volumes and following silica gel chromatography.

Freshly opened free base hydrazines used.

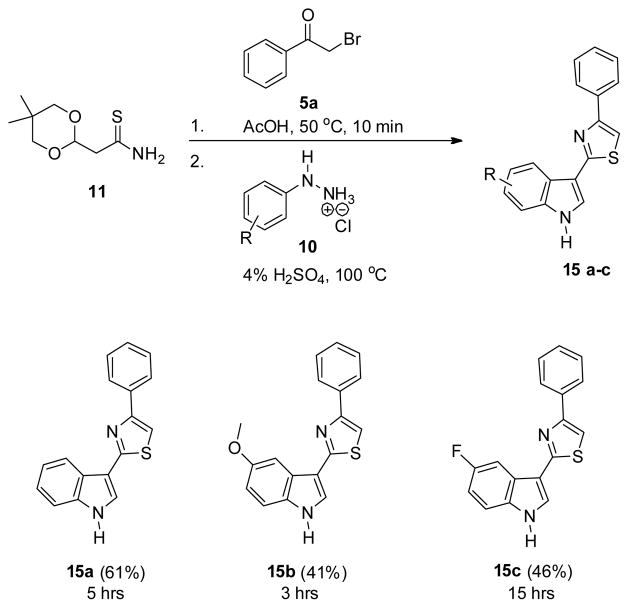

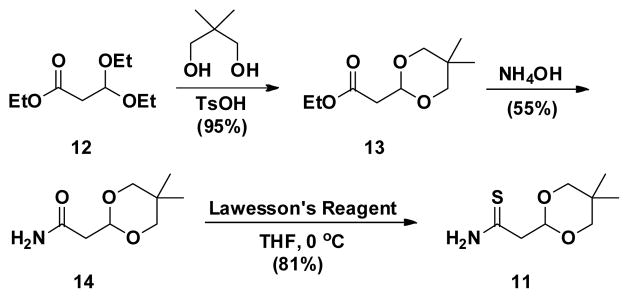

Each of the indolylthiazoles (1a–1v) thus far described was a derivative of 2-methylindole as a direct result of using thioamide 3 in the experiments. To broaden the scope of the methodology and increase the structural diversity of the scaffold, we became interested in methods to rapidly prepare 2-(1H-indol-3-yl)thiazoles lacking a 2-methyl group. In addition to enhancing the utility of our methodology, functionalization of the 2-position of an indole heterocycle is well established16 and would provide access to highly complex and valuable intermediates for continued chemistry. Thus, we envisioned that an acetyl-protected thioamide precursor such as 11 might accomplish this goal (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Batch Synthesis of Acetyl-Protected Thioamide 11

Beginning from commercially available ethyl ester 12, reaction with neopentyl glycol in the presence of catalytic acid provided acetal 13 in near quantitative yield (95%).17 Then, treatment with aqueous ammonium hydroxide (28–30% ammonia) under ambient conditions afforded amide 14 in 55% yield. Lastly, reaction with Lawesson’s Reagent furnished the target acetyl-protected thioamide 11 in high yield (81%) following column chromatography. Taken together, thioamide 11 was accessed in three steps in an overall yield of 42% with only one purification step necessary. Similar to thioamide 3, 11 can be stored at room temperature without significant decomposition and is stable in both organic and aqueous solutions used for all the experiments described herein.

With building block 11 in hand, we turned our attention to the flow synthesis of 2-H-indolylthiazoles. To start, we simply exchanged thioamide 3 with 11 and used the same setup and reaction conditions shown in Scheme 3. Unfortunately, liberated equivalents of HBr and water following thiazole formation proved insufficient to release the masked aldehyde necessary for the Fischer indole synthesis. Higher microreactor temperatures, longer reaction times, acid additives, and increased water equivalents all failed to remove the acetyl-protection group. Thus, it became clear to us that a completely aqueous reaction environment would be necessary for deprotection. While this would likely preclude development of a continuous flow method using the AFRICA synthesis station due to decreased solubility, a one-pot procedure in batch mode remained an attractive option. In 1989, Speckamp and co-workers developed a one-pot deacetylation/Fischer indole reaction in their total synthesis of the Aristotelia alkaloid peduncularine.18 For this, they heated 4% aqueous sulfuric acid at reflux for 16 h in the presence of phenylhydrazine hydrochloride.

The one-pot batch synthesis of 2-H-indolylthiazoles 15 from acetyl-protected thioamide 11 is outlined in Scheme 5. For all experiments, 2-bromoacetophenone 5a was first heated together with thioamide 11 for 10 min in water soluble acetic acid. Then, a solution of hydrazine 10 in sulfuric acid (4% aq.) was added and the reaction mixtures monitered at reflux. Gratifyingly, hydrazines 10 bearing electron-donating, unsubstituted, and electron-withdrawing halogen substitution were all found to be suitable for this process requiring 5, 3, and 15 h for completion, respectively. As expected, precipitates readily formed in the AFRICA chip during the course of all reactions making such transformations impractical within our microfluidic chips.

Scheme 5.

One-Pot Batch Synthesis of 2-H-Indolylthiazoles 15

In conclusion, we have engineered consecutive heterocycle formation reactions using an automated continuous flow process that allows efficient access to a novel class of indolylthiazoles (1). These complex heterocyclic scaffolds are constructed rapidly and in high yield allowing the facile synthesis of libraries of biologically active analogues. We have also developed an efficient one-pot (batch) procedure for the synthesis of related 2-H-indolylthiazoles. Further applications of both the continuous flow and batch methods to the generation of analogues with optimal biological activity are in progress.

All reactions were carried out using oven-dried glassware and conducted under a positive pressure of nitrogen unless otherwise specified. NMR spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz spectrometer. All NMR samples were prepared using DMSO-d6. High resolution mass spectrometry data were obtained with a time of flight mass spectrometer (MS-TOF) using electrospray ionization at the Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (SBMRI). LC/MS analyses were carried out using a 5 micron C18 column (50 x 2.1 mmID). Silica gel purifications were accomplished using pre-packed columns. All reagents and solvents were used as received from standard suppliers. Microfluidic experiments were conducted using a Syrris AFRICA® synthesis station.

Synthesis of indolylthiazoles (1a–1l)

All reactions were conducted in DMF under a positive pressure of nitrogen. Streams of the thioamide 3 (32.5 μL/min, 0.50 M, DMF, 1 equiv) and a solution of α-bromoketones 5 (32.5 μL/min, 0.50 M, DMF, 1 equiv) were mixed in a 250 μL glass reactor heated to 150 °C (3.75 min). After exiting the chip, the combined flow (65.0 μL/min) was introduced to a single stream (32.5 μL/min, 0.50 M, DMF, 1 equiv) of phenylhydrazine hydrochloride (10a) in a 1000 μL glass reactor heated to 200 °C (10 min). The reaction flow was then collected (1000 μL) after passing though the back pressure regulator. These reactions were carried out with a back pressure of 6.0 bar. Then, the crude reaction mixtures were adsorbed onto silica gel, loaded onto a pre-packed silica gel column (12 g), and chromatographed using hexanes:EtOAc (30 mL/min, 100% hexanes for 2 min then ramped to 40% EtOAc in hexanes over 18 min). The products were isolated as yellow-brown amorphous solids.

2-(2-Methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole (1a)

Yield: 0.024 g (50%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.68 (s, 1H), 8.24 (dd, J = 6.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.98 (s, 1H), 7.48 (m, 2H), 7.41-7.33 (m, 2H), 7.17 (m, 2H), 2.78 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.6, 153.5, 137.6, 135.0, 134.5, 128.8, 127.9, 126.0, 125.8, 121.6, 120.5, 119.5, 111.2, 110.2, 107.0, 14.1.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C18H15N2S (M + H)+ 291.0950, found (M + H)+ 291.0965.

3-(2-(2-Methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)thiazol-4-yl)phenol (1b)

Yield: 0.033 g (65%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.67 (s, 1H), 9.52 (s, 1H), 8.24 (dd, J = 6.4, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (s, 1H), 7.52 (m, 1H), 7.48 (m, 1H), 7.40 (m, 1H), 7.25 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (m, 2H), 6.75 (ddd, J = 7.8, 2.3, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 2.77 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.4, 157.7, 153.6, 137.5, 135.7, 135.0, 129.7, 125.8, 121.6, 120.5, 119.6, 116.8, 114.9, 113.0, 111.1, 110.1, 107.0, 14.0.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C18H15N2OS (M + H)+ 307.0900, found (M + H)+ 307.0931.

4-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)thiazole (1c)

Yield: 0.026 g (49%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.66 (s, 1H), 8.23 (dd, J = 6.0, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (m, 2H), 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.40 (m, 1H), 7.17 (m, 2H), 7.04 (m, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 2.78 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.4, 159.0, 153.4, 137.4, 135.0, 127.4, 125.8, 121.6, 120.5, 119.5, 114.1, 111.1, 108.2, 107.0, 55.1, 14.0, one hidden carbon.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C19H17N2OS (M + H)+ 321.1056, found (M + H)+ 321.1081.

2-(2-Methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-(p-tolyl)thiazole (1d)

Yield: 0.025 g (49%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.67 (s, 1H), 8.23 (dd, J = 6.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (m, 2H), 7.92 (s, 1H), 7.40 (m, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.2, 2H), 7.18 (m, 2H), 2.78 (s, 3H), 2.35 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.5, 153.6, 137.5, 137.1, 135.0, 131.8, 129.3, 126.0, 125.8, 121.6, 120.5, 119.5, 111.1, 109.3, 107.0, 20.9, 14.0.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C19H17N2S (M + H)+ 305.1107, found (M + H)+ 305.1113.

4-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-yl)-2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)thiazole (1e)

Yield: 0.027 g (44%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.68 (s, 1H), 8.24 (dd, J = 6.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (m, 2H), 8.03 (s, 1H), 7.77 (m, 2H), 7.71 (m, 2H), 7.46 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (m, 2H), 7.39-7.33 (m, 2H), 2.77 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.7, 153.1, 139.7, 139.4, 137.7, 135.0, 133.6, 129.0, 127.5, 127.0, 126.6, 126.6, 125.8, 121.7, 120.6, 119.5, 111.2, 110.4, 107.0, 14.1.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C24H19N2S (M + H)+ 367.1263, found (M + H)+ 367.1265.

2-(2-Methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-(naphthalen-2-yl)thiazole (1f)

Yield: 0.025 g (44%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.71 (s, 1H), 8.62 (s, 1H), 8.29 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (dd, J = 8.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (s, 1H), 8.03-8.00 (m, 2H), 7.93 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (m, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 7.3, 1H), 7.20 (m, 2H), 2.82 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.8, 153.5, 137.7, 135.0, 133.2, 132.6, 132.0, 128.3, 128.2, 127.6, 126.4, 126.1, 125.8, 124.6, 124.4, 121.6, 120.6, 119.6, 111.2, 110.9, 107.0, 14.1.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C22H17N2S (M + H)+ 341.1107, found (M + H)+ 341.1103.

4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)thiazole (1g)

Yield: 0.025 g (49%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.70 (s, 1H), 8.23 (dd, J = 6.0, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (m, 2H), 7.98 (s, 1H), 7.41 (m, 1H), 7.32 (m, 2H), 7.18 (m, 2H), 2.78 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.8, 161.8 (dC-F, J = 245.4 Hz), 152.4, 137.7, 135.0, 131.1, 128.0 (dC-F, J = 8.6 Hz), 125.7, 121.6, 120.5, 119.5, 115.6 (dC-F, J = 21.1 Hz), 111.2, 110.0, 106.9, 14.1.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C18H14FN2S (M + H)+ 309.0856, found (M + H)+ 309.0866.

4-(4-Chlorophenyl)-2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)thiazole (1h)

Yield: 0.025 g (46%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.70 (s, 1H), 8.22 (dd, J = 6.0, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (m, 2H), 8.06 (s, 1H), 7.54 (m, 2H), 7.40 (m, 1H), 7.17 (m, 2H), 2.77 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.9, 152.2, 137.8, 135.0, 133.3, 132.3, 128.8, 127.7, 125.7, 121.7, 120.6, 119.5, 111.2, 111.0, 106.8, 14.1.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C18H14ClN2S (M + H)+ 325.0561, found (M + H)+ 325.0568.

4-(4-Bromophenyl)-2-(2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)thiazole (1i)

Yield: 0.028 g (46%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.71 (s, 1H), 8.23 (dd, J = 6.4, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 8.07 (s, 1H), 8.04 (m, 2H), 7.68 (m, 2H), 7.41 (m, 1H), 7.18 (m, 2H), 2.78 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.9, 152.3, 137.8, 135.0, 133.7, 131.7, 128.0, 125.7, 121.7, 120.9, 120.6, 119.5, 111.2, 111.0, 106.8, 14.1.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C18H14BrN2S (M + H)+ 371.0036, found (M + H)+ 371.0045.

2-(2-Methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)thiazole 1j

Yield: 0.026 g (43%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.73 (s, 1H), 8.31-8.23 (m, 4H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (m, 1H), 7.19 (m, 2H), 2.79 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 163.2, 151.9, 138.2, 137.9, 135.0, 126.6, 125.8, 125.8, 125.7, 121.7, 120.6, 119.5, 112.9, 111.2, 106.8, 14.1.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C19H14F3N2S (M + H)+ 359.0824, found (M + H)+ 359.0840.

4-(2-(2-Methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)thiazol-4-yl)benzonitrile (1k)

Yield: 0.025 g (48%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.74 (s, 1H), 8.28-8.21 (m, 4H), 7.94 (m, 2H), 7.40 (m, 1H), 7.18 (m, 1H), 2.77 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 163.2, 151.7, 138.5, 138.1, 135.0, 132.9, 126.6, 125.7, 121.7, 120.7, 119.5, 113.7, 111.2, 110.0, 106.7, 14.1.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C19H14N3S (M + H)+ 316.0903, found (M + H)+ 316.0907.

2-(2-Methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-(thiophen-2-yl)thiazole (1l)

Yield: 0.020 g (41%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.71 (s, 1H), 8.22 (s, 1H), 7.82 (s, 1H), 7.63 (dd, J = 3.4, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (dd, J = 5.0, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (m, 1H), 7.19-7.13 (m, 3H), 2.75 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.7, 148.2, 138.6, 137.8, 135.0, 128.0, 125.7, 123.8, 121.7, 120.6, 119.5, 111.2, 108.4, 106.6, 13.9.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C16 H13N2S2 (M + H)+ 297.0515, found (M + H)+ 297.0516.

Synthesis of Indolylthiazoles 1m–1v

All reactions were conducted in DMF under a positive pressure of nitrogen. Streams of the thioamide 3 (32.5 μL/min, 0.50 M, DMF, 1 equiv) and a solution of 2-bromoacetophenone (5a) (32.5 μL/min, 0.50 M, DMF, 1 equiv) were mixed in a 250 μL glass reactor heated to 150 °C (3.75 min). After exiting the chip, the combined flow (65.0 μL/min) was introduced to a single stream (32.5 μL/min, 0.50 M, DMF, 1 equiv) of hydrazines (10) in a 1000 μL glass reactor heated to 200 °C (10 min). 0.50 M streams of hydrazines 10a and 10b were prepared using 1:1 DMF:ethylene glycol. The reaction flow was then collected (1000 μL) after passing though the back pressure regulator. These reactions were carried out with a back pressure of 6.0 bar. Then, the crude reaction mixtures were adsorbed onto silica gel, loaded onto a pre-packed silica gel column (12 g), and chromatographed using hexanes:EtOAc (30 mL/min, 100% hexanes for 2 min then ramped to 40% EtOAc in hexanes over 18 min).

2-(5-Methoxy-2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole (1m)

Yield: 0.027 g (51%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.55 (s, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.96 (s, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.35 (m, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 2.74 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.7, 154.5, 153.4, 138.0, 134.5, 129.9, 128.8, 127.8, 126.4, 126.0, 111.8, 110.8, 109.9, 107.0, 102.3, 55.2, 14.1.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C19H17N2OS (M + H)+ 321.1056, found (M + H)+ 321.1060.

2-(5-Fluoro-2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole (1n)

Yield: 0.024 g (47%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.81 (s, 1H), 8.07 (m, 2H), 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.99 (dd, J = 10.0, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (m, 2H), 7.40 (dd, J = 8.7, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (m, 1H), 7.02 (m, 1H), 2.75 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.2, 157.9 (dC-F, J = 232.9 Hz), 153.5, 139.5, 134.4, 131.6, 128.8, 127.9, 126.2 (dC-F, J = 10.5 Hz), 126.0, 112.2 (dC-F, J = 9.6 Hz), 110.4, 109.5 (dC-F, J = 25.9 Hz), 107.4, 104.7 (dC-F, J = 24.9 Hz), 14.1.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C18H14FN2S (M + H)+ 309.0856, found (M + H)+ 309.0863.

2-(5-Chloro-2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole (1o)

Yield: 0.029 g (54%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.90 (s, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.06 (m, 2H), 8.02 (s, 1H), 7.49 (m, 2H), 7.42 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (m, 1H), 7.18 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 2.76 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.0, 153.6, 139.3, 134.4, 133.5, 128.8, 128.0, 126.9, 126.0, 125.1, 121.6, 118.9, 112.7, 110.6, 106.9, 14.0.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C18H14ClN2S (M + H)+ 325.0566, found (M + H)+ 325.0564.

2-(5-Bromo-2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole (1p)

Yield: 0.027 g (44%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.92 (s, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H), 8.06 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.4 Hz, 2H), 8.03 (s, 1H), 7.50 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.40-7.35 (m, 2H), 7.30 (dd, J = 8.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 2.76 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.0, 153.6, 139.1, 134.4, 133.7, 128.8, 128.0, 127.5, 126.0, 124.1, 121.9, 113.2, 113.1, 110.7, 106.7, 14.0.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C18H14BrN2S (M + H)+ 371.0036, found (M + H)+ 371.0064.

2-(1,2-Dimethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole 1q

Yield: 0.032 g (63%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 8.21 (m, 1H), 8.07 (m, 2H), 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.55 (m, 1H), 7.48 (m, 2H), 7.35 (m, 1H), 7.23 (m, 2H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 2.86 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.5, 153.5, 138.7, 136.4, 134.4, 128.8, 127.9, 126.0, 124.9, 121.7, 120.8, 119.2, 110.5, 110.0, 106.8, 29.7, 12.0.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C19H17N2S (M + H)+ 305.1107, found (M + H)+ 305.1121.

2-(5-(Benzyloxy)-2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole (1r)

Yield: 0.024 g (38%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 8.23 (dd, J = 6.9, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (m, 2H), 8.03 (s, 1H), 7.52 (m, 1H), 7.45 (m, 2H), 7.34-7.18 (m, 6H), 7.03 (m, 2H), 5.55 (s, 2H), 2.79 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.2, 153.6, 138.3, 137.5, 136.3, 134.4, 128.8, 128.8, 128.0, 127.3, 126.2, 126.1, 125.1, 122.1, 121.1, 119.5, 110.9, 110.4, 107.6, 39.9, 12.1. HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C25H21N2OS (M + H)+ 397.1369, found (M + H)+ 397.1388.

2-(2,5-Dimethyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole (1s)

Yield: 0.029 g (57%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.60 (s, 1H), 8.11 (m, 2H), 8.02 (s, 1H), 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.52 (m, 2H), 7.39 (m, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 2.81 (s, 3H), 2.49 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.8, 153.5, 137.7, 134.5, 133.3, 129.1, 128.8, 127.9, 126.0, 126.0, 123.0, 119.1, 110.9, 110.1, 106.5, 21.6, 14.1.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C19H17N2S (M + H)+ 305.1107, found (M + H)+ 305.1121.

2-(5-(tert-Butyl)-2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole (1t)

Yield: 0.031 g, 53%.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.51 (s, 1H), 8.30 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 8.06 (m, 2H), 7.94 (s, 1H), 7.44 (m, 2H), 7.33 (m, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (s, 1H), 7.22 (dd, J = 8.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 2.73 (s, 3H), 1.36 (s, 9H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.7, 153.3, 142.8, 137.5, 134.6, 133.1, 128.8, 127.9, 126.0, 125.6, 119.7, 115.4, 110.6, 110.0, 107.1, 34.4, 31.8, 14.1.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C22H23N2S (M + H)+ 347.1576, found (M + H)+ 347.1583.

2-(2-Methyl-1H-benzo[g]indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole (1u)

Yield: 0.047 mg (82%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 12.40 (s, 1H), 8.40 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 8.35 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 8.06 (m, 2H), 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 2.84 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.6, 153.7, 135.3, 134.5, 129.7, 129.4, 128.8, 128.4, 127.9, 126.1, 125.7, 123.9, 121.7, 121.3, 121.1, 120.6, 119.9, 110.7, 108.9, 14.0.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C22H17N2S (M + H)+ 341.1107, found (M + H)+ 341.1109.

2-(1-Benzyl-2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole (1v)

Yield: 0.028 mg (44%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 8.26 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 8.07 (m, 2H), 8.04 (s, 1H), 7.55 (dd, J = 7.1, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (m, 2H), 7.37-7.20 (m, 9H), 7.05 (m, 2H), 5.57 (s, 2H), 2.82 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.3, 153.6, 138.3, 137.5, 136.2, 134.4, 128.8, 128.7, 127.9, 127.3, 126.2, 126.0, 125.1, 122.1, 121.1, 119.5, 110.8, 110.4, 107.6, 39.9, 12.1.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C25H21N2S (M + H)+ 381.1420, found (M + H)+ 381.1439.

2-(5,5-Dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-2-yl)acetamide (14)

A solution of solution 13 (4.6 g, 22.8 mmol, 1 equiv) in aqueous ammonium hydroxide (28–30% ammonia) (50 mL) was sealed and stirred vigorously at room temperature overnight. The resulting pale yellow reaction mixture was extracted with methylene chloride. Then, the combined organic layers were washed with brine, dried using Na2SO4, and concentrated to dryness in vacuo to provide amide 14.

Yield: 2.16 g (55%) as a white solid.

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 6.39 (s, 1H), 6.08 (s, 1H), 4.73 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 3.60 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 2H), 3.44 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 2H), 2.56 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H), 1.15 (s, 3H), 0.70 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 171.4, 98.7, 41.8, 30.0, 22.9, 21.6.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C8H15NNaO3 (M + Na)+ 196.0944, found (M + H)+ 196.0945.

2-(5,5-Dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-2-yl)ethanethioamide (11)

A solution of amide 14 (1.0 g, 5.78 mmol, 1 equiv) in anhydrous THF (30 mL) was prepared and cooled to 0 °C. Lawesson’s reagent (1.3 g, 3.18 mmol, 0.55 equiv) was then added and the resulting yellow suspension was allowed to naturally warm to room temperature, stirring for a total of 2 hrs. The resulting light yellow solution was concentrated in vacuo and re-dissolved in EtOAc. Then, the organic phase was washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 followed by brine, dried using Na2SO4, and concentrated to dryness in vacuo. The crude material was adsorbed onto silica gel, loaded onto a pre-packed silica gel column (80 g), and chromatographed using hexanes:EtOAc (60 mL/min, 0% EtOAc to 30% EtOAc over 45 min). Following concentration of product eluents, 11 was isolated as an off-white solid.

Yield: 0.88 g (81%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 7.96 (s, 1H), 7.71 (s, 1H), 4.75 (m, 1H), 3.64 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 2H), 3.47 (d, J = 11.0 Hz, 2H), 3.09 (m, 2H), 1.18 (s, 3H), 0.73 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 203.9, 99.4, 49.7, 29.9, 22.8, 21.4.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C8H16NO2S (M + H)+ 190.0896, found (M + H)+ 190.0906.

Synthesis of Indolylthiazoles 15a–15c

An aqueous solution of 4% sulfuric acid (2.5 mL) was heated to 50 °C following a thorough purge with nitrogen gas. Then, hydrazines 10 (0.294 mmol, 1.1 equiv) were added to the reaction mixture and dissolved by heating for an additional 10 min. At the same time, a mixture of thioamide 11 (50 mg, 0.267 mmol, 1 equiv) and 2-bromoacetophenone (10a) (54 mg, 0.267 mmol, 1 equiv) in acetic acid (0.65 mL) was purged with nitrogen and then heated to 50 °C for 10 min. Lastly, the separate reaction mixtures were combined and monitored at reflux (105 °C). Each resulting suspension was extracted with EtOAc, adsorbed onto silica gel, loaded onto a pre-packed silica gel column (12 g), and chromatographed using hexanes:EtOAc (30 mL/min, 100% hexanes for 2 min then ramped to 40% EtOAc in hexanes over 18 min).

2-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole (15a)

Yield: 0.045 g (61%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.76 (s, 1H), 8.33 (m, 1H), 8.14 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.91 (s, 1H), 7.51-7.46 (m, 3H), 7.35 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (s, 2H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.9, 153.9, 136.6, 134.4, 128.8, 127.9, 126.7, 126.0, 124.3, 122.4, 120.8, 120.4, 112.2, 110.6, 110.5.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C17H13N2S (M + H)+ 277.0794, found (M + H)+ 277.0791.

2-(5-Methoxy-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole (15b)

Yield: 0.034 g (41%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.62 (s, 1H), 8.07 (m, 3H), 7.91 (s, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.40-7.33 (m, 2H), 6.88 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 3.85 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 163.0, 154.6, 153.8, 134.4, 131.6, 128.8, 127.8, 127.1, 125.9, 124.9, 112.9, 112.2, 110.3, 110.2, 102.4, 55.3.

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C18H15N2OS (M + H)+ 307.0900, found (M + H)+ 307.0902.

2-(5-Fluoro-1H-indol-3-yl)-4-phenylthiazole (15c)

Yield: 0.036 g (46%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 11.87 (s, 1H), 8.21 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.06 (m, 2H), 8.03 (dd, J = 10.1, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (s, 1H), 7.51-7.46 (m, 3H), 7.35 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (m, 1H).

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ (ppm) 162.6, 158.0 (dC-F, J = 232.9 Hz), 154.0, 134.3, 133.2, 128.8, 128.6, 127.9, 126.0, 124.6 (dC-F, J = 10.5 Hz), 113.4 (dC-F, J = 10.5 Hz), 110.7, 110.7 (dC-F, J = 26.8 Hz), 110.6, 105.2 (dC-F, J = 24.0 Hz).

HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd for C17H12FN2S (M + H)+ 295.0700, found (M + H)+ 295.0696.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant nos. AI078048, CA140427, HG005033, GM079590, and GM081261. The MS-TOF instrument was awarded through the Bankhead-Coley Florida Biomedical Cancer Research Program shared instrument grant 09BE-02.

Footnotes

Primary Data for this article, including NMR spectral (1H & 13C) data for all new compounds, are available online at http://www.thieme-connect.com/ejournals/toc/synthesis and can be cited using the following DOI: (number will be inserted prior to online publication).

Supporting Information for this article, including Structures of α-bromoketones 5a–l and hydrazines 10a–j, is available online at http://www.thieme-connect.com/ejournals/toc/synthesis.

References

- 1.(a) Chighine A, Sechi G, Bradley M. Drug Disc Today. 2007;12:459–464. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huryn DM, Cosford NDP. Annu Rep Med Chem. 2007;42:401–416. doi: 10.1016/S0065-7743(07)42026-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Baxendale IR, Hayward JJ, Lanners S, Ley SV, Smith CD. In: Microreactors in Organic Synthesis and Catalysis. Wirth T, editor. WILEY-VCH; Weinheim: 2008. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ehrfeld W, Hessel V, Lowe H. Microreactors: New Technology for Modern Chemistry; WILEY-VCH; Weinheim: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.For recent selected reviews, see: Glasnov TN, Kappe CO. J Heterocyclic Chem. 2011;48:11–30.Webb D, Jamison TF. Chem Sci. 2010;1:675–680.Geyer K, Gustafsson T, Seeberger PH. Synlett. 2009;15:2382–2391.Mak XY, Laurino P, Seeberger PH. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2009;5(19) doi: 10.3762/bjoc.5.19.Weiler A, Junkers M. Pharm Technol. 2009;S6:S10–S11.Baxendale IR, Hayward JJ, Ley SV. Comb Chem High Throughput Screening. 2007;10:802–836. doi: 10.2174/138620707783220374.Watts P. Curr Opin Drug Discovery Dev. 2004;7:807–812.

- 4.Kang L, Chung BG, Langer R, Khademhosseini A. Drug Disc Today. 2008;13:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant D, Dahl R, Cosford NDP. J Org Chem. 2008;73:7219–7223. doi: 10.1021/jo801152c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herath A, Dahl R, Cosford NDP. Org Lett. 2010;12:412–415. doi: 10.1021/ol902433a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herath A, Cosford NDP. Org Lett. 2010;12:5182–5185. doi: 10.1021/ol102216x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pagano N, Herath A, Cosford NDP. J Flow Chem. 2011;1:28–31. doi: 10.1556/jfchem.2011.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Razzaq T, Kappe CO. Chem Asian J. 2010;5:1274–1289. doi: 10.1002/asia.201000010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daugan A, Grondin P, Ruault C, Le Monnier de Gouville A-C, Coste H, Linget J-M, Kirilovsky J, Hyafil F, Labaudinière R. J Med Chem. 2003;46:4533–4542. doi: 10.1021/jm0300577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Moody CJ, Roffey JRA, Stephens MA, Stratford I. J Anti-Cancer Drugs. 1997;8:489–499. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199706000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mezencev R, Updegrove T, Kutschy P, Repovská M, McDonald JF. J Nat Med. 2011;65:488–499. doi: 10.1007/s11418-011-0526-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Moody CJ, Roffey JRA, Swann E, Lockyer S, Houlbrook S, Stratford I. J Anti-Cancer Drugs. 1999;10:577–589. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199907000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Moody CJ, Swann E. J Med Chem. 1995;38:1039–1043. doi: 10.1021/jm00006a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wahab B, Ellames G, Passey S, Watts P. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:3861–3865. [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Brien AG, Levesque F, Seeberger PH. Chem Commun. 2011;47:2688–2690. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04481d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Zamir LO, Nguyen C. J Labelled Compd Radiopharm. 1988;25:1189–1196. [Google Scholar]; (b) Paquette LA, Efremov I. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4492–4501. doi: 10.1021/ja010313+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.For boronic acid synthesis see: Vazquez E, Davies IW, Payack JF. J Org Chem. 2002;67:7551–7552. doi: 10.1021/jo026087j.For boronic acid reactions, see: Pagano N, Maksimoska J, Bregman H, Williams DS, Webster RD, Xue F, Meggers E. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:1218–1227. doi: 10.1039/b700433h.de Koning CB, Michael JP, Rousseau AL. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans I. 2000:1705–1713.

- 17.Tietze LF, Meier H, Voβ E. Synthesis. 1988:274–277. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klaver WJ, Hiemstra H, Speckamp WN. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:2588–2595. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.