Abstract

In vitro flowering and effective micropropagation protocol were studied in Swertia chirayita, an important medicinal plant using axillary bud explants. The Murashige and Skoog's medium (MS) supplemented with benzyl amino purine (BAP) 1.0 mg L−1 and adenine sulfate 70.0 mg L−1 was found optimum for production of multiple shoots. In the present study, incubation of flowering cultures on BAP supplemented medium (during shoot multiplication) was found necessary for flowering (6 weeks). However, concentrations of auxins-like IBA (0–2.0 mg/L) were ineffective to form reproductive buds. Subculture duration, photoperiod, and carbon source type do have influence on the in vitro flowering. The mature purple flowers were observed when the cultures were maintained in the same medium. This is the very first report that describes in vitro flowering system to overcome problems associated with flower growth and development as well as lay foundation for fruit and seed production in vitro in Swertia chirayita.

1. Introduction

India is ranked the 6th among 12 mega diversity countries of the world [1] and Uttarakhand is one of the states in India which is known for its great diversity. Swertia chirayita is an important medicinal plantfound in Uttarakhand. Swertia chirayita is considered the most important plant for its bitterness, antihelminthic [2], hypoglycemic, hepatoprotective [3], and antiviral [4] properties. The novel techniques of plant tissue culture provide a viable alternative for managing these valuable resources in a sustainable manner. There are few reports about the tissue culture of Swertia chirayita. Documented literature reveals that there is a limited literature reported by few workers on in vitro propagation of Swertia chirayita, where they have used the nodal explants, in vitro grown seedlings, nodal meristems, and immature seed culture [5–9]. Balaraju et al. (2009) published reports on in vitro propagation of S. chirata using shoot tip explants derived from in vitro grown seedlings [10]. Chaudhuri et al. (2008) and Wang et al. (2009) reported direct shoot regeneration from in vitro leaves [11, 12]. But there is no report about the in vitro flowering of Swertia chirayita till date. The flowering process is one of the critical events in the life of a plant. This process involves the switch from vegetative stage to reproductive stage of growth and is believed to be regulated by both internal and external factors. A flowering system in vitro is considered to be a convenient tool to study specific aspects of flowering, floral initiation, floral organ development, and floral senescence [13]. The application of cytokinins, sucrose concentrations, photoperiod, and subculture time to promote flowering in vitro is well documented in many plant species [14, 15]. This is the very first report on in vitro flowering of this valuable medicinal plant and may open up new gates in the field of its conservation and continuous supply of plant material throughout the year by knowing its flowering behavior in vitro. This study is part of a larger programme designed to investigate the in vitro conservation protocol of Swertia chirayita and describes in vitro flowering system to overcome problems associated with flower growth and development as well as fruit and seed production in vitro and hence may open up new gates in the conservation and sustainable exploitation of this very important plant.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The nodal segments from juvenile plants of Swertia chirayita grown ex situ were collected from Hitech Nursery, Deovan, Chakrata (7,699 ft., lat. 30°43.642′, long. 77°51.941′), India, during the month of July and prepared herbarium was submitted to Botanical Survey of India, Northern Regional Centre, Dehradun (BSD), for identification of species level and plants were identified as Swertia chirayita (Roxb. ex Fleming) (VS 02) Family: Gentianaceae (Acc. number 113342). Surface sterilization was done as per the protocol given by Sharma et al. (2013) [16].

2.2. Culture Conditions

The basal media comprised of the mineral salts and organic nutrients of the MS medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) [17] containing 2.5% sucrose, solidified with 0.2% clarigel (HiMedia), and supplemented with 1.0 mg/L 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) and 70 mg/L adenine sulfate was used for culture establishment [16, 18]. The Subculturing was performed at an interval of 3 to 4 weeks. Each treatment was replicated 12 times and all experiments were repeated at least thrice.

To examine the effect of photoperiod, 3 light/dark cycles, that is, 12/12, 16/8, and 8/16, were used in monitoring flowering in vitro. To examine the subculture time, explants were subcultured to fresh MS medium supplemented with 1.0 mg/L 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) and 70 mg/L adenine sulfate on an interval of 4, 6, and 8 weeks. Five different sources of carbohydrates, that is, glucose sucrose, maltose, fructose, and lactose for a same concentration (2.5%), were examined for best flowering response. After bud formation, the cultures were shifted to continuous light of low intensity for induction of fully opened flowers. Subsequently, they were maintained under 16/8 h light/dark cycle for fruit development.

3. Results

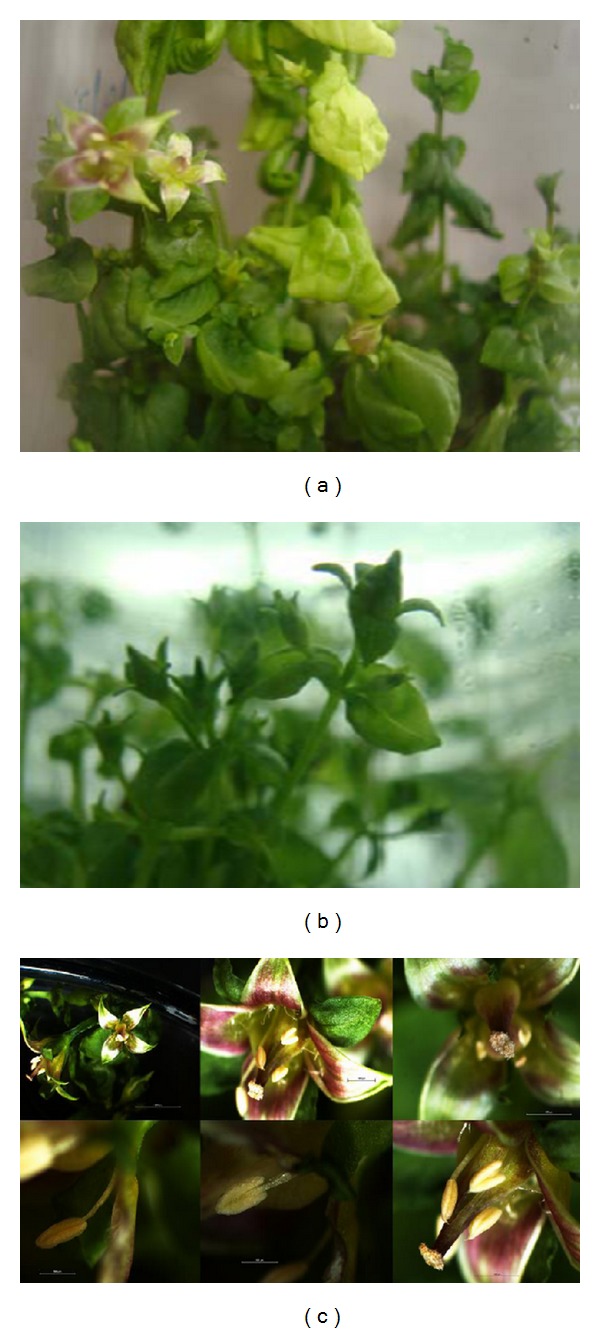

The in vitro flowering was observed in the present study of Swertia chirayita and had not been reported earlier. In vitro flowering offers a unique systemin the study of molecular basis and hormonal regulation of flowering. Flower initiated in MS media supplemented with BAP (1.0 mg/L) and adenine sulfate (70 mg/L) (Figure 1(a)) after 4–6 weeks of cultures. The production of flowering shoots continued for many subcultures spanning a period of more than two years. Flowers produced from tissue cultures systems presented normal morphological aspects. They were monoecious and differentiated from lateral branches as field-grown plants (Figure 1(c)). Besides, anthesis was observed in floral buds development.

Figure 1.

(a) In vitro flowering in Swertia chirayita. (b) Flower buds production. (c) Micrograph of in vitro flowers showing various parts of the flower and anthesis.

Maximum numbers of flowers (buds) (12 per culture) were obtained when shoots werecultured on MS medium containing 1.0 mg/L BAP + 70 mg/L adenine sulfate (Figure 1(b)) and incubated at 16/8 h light/dark period after 6 weeks. In the present study, incubation of flowering cultures on BAP supplemented medium (during shoot multiplication) was necessary for flowering (6 weeks). However, concentrations of auxins-like IBA (0–2.0 mg/L) were ineffective to form reproductive buds (data not shown). The production of flowers was promoted in approximately the same proportion. Flowering was induced in vitro in excised shoot cultures of Swertia chirayita devoid of any preformed bud. Photoperiod was found to be important for in vitro flowering. Maximum in vitro flowers were obtained at 16 hrs ± 2 light periods; it was observed that plants incubated under 12 hrs or shorter photoperiods (8 hrs) were negatively affected for floral bud development. Optimum temperature for efficient in vitro flowering was 24°C ± 2°C with a relative humidity of 60–70%. The nature of carbon source (mono or disaccharides) in the medium has an important influence on the formation of reproductive buds. The carbohydrates slightly differed in their ability to support the formation of reproductive buds. In general, sucrose was best closely followed by glucose; maltose and fructose were also effective for formation of flowering shoots whereas lactose was totally ineffective (Table 1).

Table 1.

| S. number |

Photoperiod (light/dark) |

Carbohydrate source | Subculture duration | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | G | F | M | L | 4 wks | 6 wks | 8 wks | ||

| 1 | 12 h/12 h | b | c | c | c | d | d | c | c |

| 2 | 16 h/8 h | a | b | b | b | d | d | a | b |

| 3 | 8 h/16 h | d | d | d | d | d | d | d | d |

S: sucrose, G: glucose, F: fructose, M: maltose, and L: lactose (All 2.5%). Flowering response: a: average of 12 flower buds per culture, b: average of 6 flower buds per culture, c: average of 4 flower buds per culture, and d: no flowering. All cultures were maintained on full strength MS medium with 1 mg/L BAP and .007% adenine sulfate.

4. Discussion

Flowering is considered to be a complex process regulated by both internal and external factors and its induction under in vitro culture is extensively rare. Physiological studies have sought for many years about what is florigen and have shown that flowering time control is influenced by environmental factors and endogenous cues. Plants can integrate these signals, such as day length, vernalization, ambient temperature, irradiance, water/mineral availability, and presence/absence of neighbors, to relate flowering time. Flowering in vitro has been promoted by cytokinins at optimum concentrations.

Results obtained from our previous study [16] revealed that, after 4 weeks of initial culture, nodal explants cultured on MS medium with BAP (1.0 mg/L) and .007% (70 mg/L) adenine sulfate developed maximum number of multiple shoots and cytokinin especially that BAP with adenine sulfate was found to be the key component for multiple shoot establishment. In the present investigation, effectiveness of BAP in inducing bud break was observed and has been reported in many other plant species [19–22]. Cytokinin is a common requirement for in vitro flowering [23]. A number of studies report the use of cytokinins for in vitro flowering in species like Murraya paniculata [24], Fortunella hindsii [25], Gentiana triflora [26], Pharbitis nil [27] and Ammi majus [28]. There are reports that indicate the beneficial effects of cytokinin especially BAP on the induction of in vitro flowering for medicinal plants like Withania somnifera, Rauvolfia tetraphylla, and Anethum graveolens [29–31] which are in accordance with our investigation. BAP is found to be playing an important role not only as a growth regulator but also as a factor regulating floral organ formation of regenerated plantlets [32]. It has been reported that phytohormones affected flowering by mediating growth changes within the apical meristem and that cytokinins, in particular, played a key role in the initiation of mitosis and the regulation of cell division and organ formation. Auxins have frequently been reported to inhibit the formation of flowering buds in vitro in both long-day plants and short-day plants; low concentrations, however, may promote flowering even when higher ones are inhibitory [33]. Chrungoo and Farooq (1984) reported that, in saffron plants, NAA had an inhibitory effect on sprouting, vegetative growth, and flowering [34] and this has been in accordance with the present study where incorporation of IBA was not having promontory or inductive effect on flowering initiation. Carbohydrate source is also found to be an important factor and, in the present study, a lower concentration of 2.5% was found optimum for Swertia chirayita for flower initiation and maturation. This has been evident from study on Arabidopsis thaliana which reported that presence of sucrose in aerial parts of the plant promotes flowering [35]. Sucrose and cytokinins interact with each other for floral induction in Sinapis alba by moving between shoot and root.

Light is the most important environmental factor that induces changes in plant physiology and morphology, regulating flowering season cycles [36–38]. Day length and light quality play a crucial role in flower induction both in vivo and in vitro possibly due to altered photosynthetic turnover on flowering and are believed to be essentially perceived by expanded leaves; then, “florigen” (sucrose and isopentenyladenine) will be produced and moved directly or indirectly to shoot apical meristem (SAM) to guide flowering determination [39]. In some plants, vernalization alone is sufficient for flowering evocation, but others require subsequent exposure to inductive photoperiods (usually long days), and in them the changes at the apex wrought by vernalization and the photoperiodic stimulus are presumably different, possibly complementary [33]. Swertia chirayita is a high altitudinal plant enjoying gloomy and cold situation in nature, but importance of photoperiod instead of the vernalization for in vitro flowering of this plant has been demonstrated in the present study and maximum flowering frequency was observed with 16 h photoperiod. Subculture duration was also found to be an important factor for in vitro flowering in Swertia chirayita and importance of subculture duration has also been demonstrated by Wang et al. (2002) in other plant species [14].

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our work has laid a preliminary foundation for a further research of in vitro flowering of Swertia chirayita. In tissue culture, in vitro flowering serves as an important tool for many reasons. One of the most important ones is being able to shorten the life cycles of plants; other aims include studying flower induction and initiation and floral development. Controlling the environment and media components enables the manipulation of different variables that affect these processes. So, this technique is of practical importance and can also serve for mass production of specific organs with unique compounds for pharmaceutical, nutritional, and other uses.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very thankful to management of SBSPGI for providing necessary facilities for successful completion of the research work and UCOST for financial assistance.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Ramachandra TV, Suja A. Sahyadri: western ghats biodiversity information system. In: Ramakrishnan N, editor. Biodiversity in Indian Scenario. chapter 1. New Delhi, India: Daya Publishing House; 2006. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medda S, Mukhopadhyay S, Basu MK. Evaluation of the in-vivo activity and toxicity of amarogentin, an antileishmanial agent, in both liposomal and niosomal forms. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1999;44(6):791–794. doi: 10.1093/jac/44.6.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rastogi RP, Mehrotra BN. Compendium of Indian Medicinal Plants. Vol. 5. New Delhi, India: CDRI, Lukhnow and National Institute of Science Communication; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng MS, Lu ZY. Antiviral effect of mangiferin and isomangiferin on herpes simplex virus. Chinese Medical Journal. 1990;103(2):160–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahuja A, Koul S, Kaul BL, et al. Media compositions for faster propagation of Swertia chirata . Patent WO 03/045132 A1, 2003.

- 6.Joshi P, Dhawan V. Axillary multiplication of Swertia chirayita (Roxb. Ex Fleming) H. Karst., a critically endangered medicinal herb of temperate Himalayas. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology. 2007;43(6):631–638. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koul S, Suri KA, Dutt P, Sambyal M, Ahuja A, Kaul MK. Protocol for in vitro regeneration and marker glycoside assessment in Swertia chirata Buch-Ham. In: Jain SM, Saxena PK, editors. Methods in Molecular Biology, Protocols for In Vitro Cultures and Secondary Metabolite Analysis of Aromatic and Medicinal Plants. Vol. 547. New York, NY, USA: Humana Press; 2009. pp. 139–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaudhuri RK, Pal A, Jha TB. Production of genetically uniform plants from nodal explants of Swertia chirata Buch.-Ham. ex Wall.—an endangered medicinal herb. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology. 2007;43(5):467–472. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhuri RK, Pal A, Jha TB. Regeneration and characterization of Swertia chirata Buch.-Ham. ex Wall. plants from immature seed cultures. Scientia Horticulturae. 2009;120(1):107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balaraju K, Agastian P, Ignacimuthu S. Micropropagation of Swertia chirata Buch.-Hams. ex Wall.: a critically endangered medicinal herb. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum. 2009;31(3):487–494. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhuri RK, Pal A, Jha TB. Conservation of Swertia chirata through direct shoot multiplication from leaf explants. Plant Biotechnology Reports. 2008;2(3):213–218. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, An L, Hu Y, Wei L, Li Y. Influence of phytohormones and medium on the shoot regeneration from leaf of Swertia chirata Buch.-Ham. ex Wall. in vitro . African Journal of Biotechnology. 2009;8(11):2513–2517. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goh CJ. Studies on flowering in orchids—a review and future directions. Proceedings of the Nagoya International Orchid Show (NIOC '92); 1992; Nagoya, Japan. pp. 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang GY, Yuan MF, Hong Y. In vitro flower induction in roses. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology. 2002;38(5):513–518. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vu NH, Anh PH, Nhut DT. The role of sucrose and different cytokinins in the in vitro floral morphogenesis of rose (hybrid tea) cv. ‘First Prize’. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture. 2006;87(3):315–320. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma V, Kamal B, Srivastava N, Dobriyal AK, Jadon V. Effects of additives in shoot multiplication and genetic validation in Swertia chirayita revealed through RAPD Analysis. Plant Tissue Culture and Biotechnology. 2013;23(1):11–19. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum. 1962;15(3):473–497. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma V. In vitro rapid mass multiplication and molecular validation of Swertia chirayita [Ph.D. thesis] Uttarakhand, India: HNB Garhwal University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goel N, Singh N, Saini R. Efficient in vitro multiplication of Syrian rue (Peganum harmala L.) using 6-benzylaminopurine pre-conditioned seedling explants. Nature and Science. 2009;7:129–134. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lal D, Singh N. Mass multiplication of Celastrus paniculatus Willd—an important medicinal plant under in vitro conditions using nodal segments. Journal of American Science. 2010;6(7):55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lal D, Singh N, Yadav K. In vitro studies on Celastrus paniculatus . Journal of Tropical Medicinal Plants. 2010;11(2):169–174. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yadav K, Singh N. In vitro propagation and biochemical analysis of field established wood apple (Aegle marmelos L.) Analele Universităţii Din Oradea. 2011;18(1):23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scorza R. In vitro flowering. Horticulture Review. 1982;4:106–127. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jumin HB, Ahmad M. High-frequency in vitro flowering of Murraya paniculata (L.) Jack. Plant Cell Reports. 1999;18(9):764–768. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jumin HB, Nito N. In vitro flowering of Fortunella hindsii (Champ.) Plant Cell Reports. 1996;15(7):484–488. doi: 10.1007/BF00232979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Z, Leung DWM. A comparison of in vitro with in vivo flowering in Gentian. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture. 2000;63(3):223–226. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galoch E, Czaplewska J, Burkacka-Łaukajtys E, Kopcewicz J. Induction and stimulation of in vitro flowering of Pharbitis nil by cytokinin and gibberellin. Plant Growth Regulation. 2002;37(3):199–205. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pande D, Purohit M, Srivastava PS. Variation in xanthotoxin content in Ammi majus L. cultures during in vitro flowering and fruiting. Plant Science. 2002;162(4):583–587. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anitha S, Kumari BDR. In vitro flowering in Rauvolfia tetraphylla L. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences. 2006;9(3):422–424. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jana S, Shekhawat GS. Plant growth regulators, adenine sulfate and carbohydrates regulate organogenesis and in vitro flowering of Anethum graveolens . Acta Physiologiae Plantarum. 2011;33(2):305–311. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saritha KV, Naidu CV. In vitro flowering of Withania somnifera Dunal.—an important antitumor medicinal plant. Plant Science. 2007;172(4):847–851. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandal AB, Maiti A, Elanchezhian R. In vitro flowering in maize (Zea mays L.) Asia-Pacific Journal of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. 2000;8(1):81–83. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans LT. Flower induction and the florigen concept. Annual Review of Plant Physiology. 1971;22:365–394. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chrungoo NK, Farooq S. Influence of gibberellic acid and naphtaleneacetic acid on the yield of saffron and on growth in saffron crocus (Crocus sativus L.) Journal of Plant Physiology. 1984;27:201–205. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roldán M, Gómez-Mena C, Ruiz-García L, Salinas J, Martínez-Zapater JM. Sucrose availability on the aerial part of the plant promotes morphogenesis and flowering of Arabidopsis in the dark. Plant Journal. 1999;20(5):581–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Victório CP, Kuster RM, Lage CLS. Light quality and production of photosynthetic pigments in in vitro plants of Phyllanthus tenellus Roxb. Brazilian Journal of Biosciences. 2007;5:213–215. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Victório CP, Tavares ES, Lage CLS. Plant anatomy of Phyllanthus tenellus Roxb. cultured in vitro under different light qualities. Brazilian Journal of Biosciences. 2007;5:216–218. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kerbauy GB. Fisiologia Vegetal. 2nd edition. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Guanabara Koogan; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernier G, Périlleux C. A physiological overview of the genetics of flowering time control. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2005;3(1):3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2004.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]