Abstract

Objectives. We examined neighborhood-level foreclosure rates and their association with onset of depressive symptoms in older adults.

Methods. We linked data from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (2005–2006 and 2010–2011 waves), a longitudinal, nationally representative survey, to data on zip code–level foreclosure rates, and predicted the onset of depressive symptoms using logit-linked regression.

Results. Multiple stages of the foreclosure process predicted the onset of depressive symptoms, with adjustment for demographic characteristics and changes in household assets, neighborhood poverty, and visible neighborhood disorder. A large increase in the number of notices of default (odds ratio [OR] = 1.75; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.14, 2.67) and properties returning to ownership by the bank (OR = 1.62; 95% CI = 1.06, 2.47) were associated with depressive symptoms. A large increase in properties going to auction was suggestive of such an association (OR = 1.45; 95% CI = 0.96, 2.19). Age, fewer years of education, and functional limitations also were predictive.

Conclusions. Increases in neighborhood-level foreclosure represent an important risk factor for depression in older adults. These results accord with previous studies suggesting that the effects of economic crises are typically first experienced through deficits in emotional well-being.

Recent evidence suggests that the foreclosure crisis, emerging in full force in 2007, has had devastating effects on the housing market and on the condition of housing units in neighborhoods with high rates of foreclosure. Economic models point to significant neighborhood externalities associated with increases in foreclosure rates,1,2 and extant research suggests that the impact of an economic downturn may first be felt through depression.3

Depression, in turn, has important implications for physical health, quality of life, and the cost of medical care.4 Research on the association between neighborhood social context and depression suggests that the surrounding neighborhood environment may have independent effects on depression, over and above individual influences.5

Research on foreclosure and health is limited, but ecological analyses suggest an association between a spike in foreclosures and use of health services, such as unscheduled hospital visits.6 To our knowledge, no research has examined the role of the economic downturn, or the “Great Recession,” in the onset of depression with a focus on the residential context in which individuals observe economic decline.6 We therefore explored the onset of depression over the interval of the economic downturn with a unique data source, the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP), and with attention to one visible sign of economic decline—household foreclosures.

Fortuitously, NSHAP wave 1 (W1) was collected in 2005 and 2006 and wave 2 (W2) in 2010 and 2011, thus bounding the economic downturn and foreclosure crisis. We linked these data with national foreclosure data to examine the effect of neighborhood foreclosure rates on the onset of depressive symptoms. NSHAP is a study of older adults (≥ 57 years), a group for whom the experience of foreclosure in the residential environment may be particularly relevant.7 More than 1.5 million older adults lost their homes between 2007 and 2011; by 2011, the foreclosure rate for this age group was more than 8 times what it had been at the inception of the crisis. The Federal Reserve reports that nearly one half of households whose head is aged 65 to 74 years have no retirement account savings,8 making the value of one’s home, and the fear of its loss, of even greater concern. Although the absolute risk of foreclosure may still be relatively low for older adults, the experience of an increase in that risk in the immediate neighborhood environment may nevertheless have consequences. Furthermore, the effects of foreclosure at the neighborhood level may be borne most heavily by older residents. Retirement and mobility limitations may diminish the radius of routine activity; the immediate neighborhood environment may then become more important because the greater share of one’s day is spent in neighborhood space.9

Drawing on physical and social disorder approaches in urban sociology and research on neighborhoods and mental health in social epidemiology,10–14 we hypothesized that increased foreclosure rates in the immediate environment and the corresponding decline in the condition of housing may affect onset of depression and reports of depressive symptoms. A key component of our model was that foreclosure and deteriorated housing, the increased presence of vacant or abandoned buildings, and the associated potential for increased criminal activity15 may have significant consequences for mental health. Physical disorder (e.g., boarded-up buildings, infrastructure deterioration) may combine with indicators of social decline (e.g., crime, loitering), leading to a depressed mood, fear, and social withdrawal.16,17 Mental health states such as these may discourage contact among residents18,19 and lead to lower levels of street activity,20 further disconnecting older adults from potentially important sources of local social support and interaction. Thus the erosion of neighborhood life that accompanies high rates of foreclosure may have a significant impact on the mental health of its residents.

METHODS

These data came from 2 waves of the NSHAP survey, a nationally representative longitudinal probability sample of older adults.21 The sample design involved selection with probability proportional to size and oversampling of African Americans, Hispanics, and the oldest old (≥ 85 years), with a minimum age for inclusion of 57 years. The final weighted response rate was 75.5%, and the W1 sample size was 3005.22 Of the original 3005 participants, 2261 returned to be reinterviewed in 2010 (W2); 430 were deceased, 139 were in too poor health for inclusion, 4 were residing in a nursing home, and 171 could not be located. We restricted our sample to those 2261 persons who survived or were able to participate in W2 (75.2%).

We geocoded NSHAP respondents’ home addresses and linked them to tract data from the 2000 and 2010 censuses, the 2009 American Community Survey (ACS),23 and zip code–level data purchased from RealtyTrac, the authoritative source of data on foreclosure.24 From the census and ACS we obtained the number of housing units and the proportion of people living in the respondent’s tract who were below the poverty line, respectively. Note that the lag between the 2000 census and W1 is longer than that between the 2010 census and W2. Also note that the 2009 ACS aggregates across the 2005–2009 interval to determine estimates of those living in poverty. RealtyTrac data provided the number of housing units in a zip code that experienced foreclosure during the 2 field periods, as well as information on state-by-state differences in foreclosure processes. We focused on 3 stages of the foreclosure process—notice of default, auction, and transition to real-estate–owned (REO), which we schematize in Figure 1. Notice of default is the initial stage of the process in which homeowners are alerted to a mortgage account in arrears (typically 60–90 days in default). Assuming that the mortgage holders are unable to repay the lender, the property is then taken to auction, where it may be purchased by a third party. However, if no buyer purchases the property, it reverts to ownership by the lender, usually a bank. If a property reaches this final stage, it is described as REO. Note that borrowers may successfully repay their mortgages and third parties may purchase foreclosed properties at auction, meaning that a property that exists at one stage of the process will not inevitably proceed to the next stage. Each stage also may lead to increases in visible disorder (e.g., piles of mail and newspapers, unmowed lawns, signage indicating foreclosure) as borrowers disinvest in the upkeep of their homes as foreclosure approaches, or, in other cases, are evicted. We therefore count “foreclosure” not as a single variable but as a complex process that may affect neighborhood conditions and quality, and thus depression, through all 3 foreclosure stages.

FIGURE 1—

The foreclosure process in the United States.

Throughout this analysis, foreclosures are given in terms of the percentage of housing stock that received notices of default, went to auction, or became REO between the W1 and W2 field periods. RealtyTrac also allowed us to examine which respondents lived in states with judicial versus nonjudicial foreclosure processes. Judicial processes tend to be slower because the process must be approved by a judge, who may have a considerable backlog of cases.

In addition to using the administrative data sources described in this section, the NSHAP project team asked field interviewers, at both waves, to rate the condition of the respondent’s building and street. From interviewer reports we constructed a scale, “neighborhood disorder,” that reflected visible physical disorder in the respondent’s built environment (at W1, α = 0.76; at W2, α = 0.81). The disorder scale comprised 2 items: (1) How well kept is the building in which the respondent lives? and (2) How well kept are most of the buildings on the street (1 block, both sides) where the respondent lives? Possible responses were as follows: very poorly kept (needs major repairs), poorly kept (needs minor repairs), fairly well kept (needs cosmetic work), and very well kept.

Our outcome was significant depressive symptoms, a dichotomous measure derived from the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) that was asked of our NSHAP respondents. This version of the CES-D uses the 11 questions from the Iowa Short Form of the CES-D.25 Following previous analyses and recommendations from the NSHAP investigative team (Martha K. McClintock, written communication, 2011), we dichotomized the CES-D at 8 (range = 0–22). This corresponds to the established cut point for the Iowa Short Form, which is used to identify those individuals with significant and persistent depressive symptoms.25 We chose depression as an outcome on the basis of existing empirical work suggesting that economic downturns tend to have a more immediate impact on mental rather than physical health.26 We hypothesized that living in a neighborhood with a high rate of foreclosure will lead to symptoms of depression through a general sense of disinvestment, concern over the value of one’s own assets or the assets of one’s neighbors, and fewer opportunities for social interaction.

Our analysis made use of logit-linked regression to predict depressive symptoms. We predicted whether the respondents developed symptoms between the 2 waves, restricting the risk pool for becoming depressed to those respondents who did not report depression at W1. We used changes in predictors where applicable (changes in percentage of foreclosure, percentage poor, neighborhood disorder, household assets, marital status, limitations in activities of daily living, and whether the respondent moved between the 2 waves). The NSHAP measured assets by asking respondents to provide the approximate amount of assets held in their homes, cars, rental properties, businesses, savings, stocks, mutual funds, and pensions, over and above their loans. Activities of daily living limitations included difficulty walking a block, walking across a room, dressing, showering, eating, toileting, driving, and getting in and out of bed.27 We were concerned about functional limitations because respondents who are more physically disabled may be more likely to experience depression.28 Our regression employed sampling weights, Taylor linearized standard errors, and adjustments for primary sampling unit clustering and sample stratification to obtain correct point and variance estimates.22

To address missing data, we made use of multiple imputation with chained equations (MI-ICE) to create imputed values.29 A total of 2.7% of respondents had missing data on the dependent variable, 3.0% on percentage of REO property, 0.4% on ethnicity, 0.2% on employment status, and 53.9% on changes in assets; 38% of these data were missing from W1 and 36% from W2 (high percentages of missing data are common for data on assets and income in large-scale social surveys). MI-ICE operates by predicting each variable in the analysis using all other variables, one variable at a time. We carried out imputation with these data in wide format, predicting values of the variable at W1 and W2; we then used these imputed values to produce indices of change, restricting our regressions to analyze only returning respondents who were not depressed at W1 (n = 1883).30 We carried out each regression with 20 imputations, estimating correct standard errors for coefficients by summing within- and between-imputation variance.29–31 When asked to report household assets, some respondents did not give a single number but rather provided an upper and lower bound, so we imputed household income using interval regression.31 We employed auxiliary variables in the imputation process, so we retained the imputed cases for the dependent variable.30 We conducted all analyses with Stata version 12 statistical software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX); to restrict regressions to the subpopulation of respondents who met our inclusion criteria, we used SVY settings and the MI estimate command with the SUBPOP option.32 We present results as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Because we were concerned about nonlinear relationships between our predictors and our outcomes, we created several ordinal variables. We separated age into 3 categories: 57 to 64, 65 to 74, and 75 to 85 years. At W2, these 3 categories were 63 to 69, 70 to 79, and 80 to 90 years. For our change analysis—predicting who among the nondepressed became depressed at W2—we created 3 categories of foreclosure for each of the 3 stages of the foreclosure process. The first group comprised those whose zip codes experienced a decrease in the percentage of housing stock foreclosed between W1 and W2. A decrease may suggest a very different sort of process than the rest of the country was experiencing at the time (e.g., rapid gentrification that would lead to an overall decrease in the proportion experiencing foreclosure). For those neighborhoods that experienced any increase in the percentage of housing stock foreclosed or no change at all, we divided those cases into 2 groups based on the median value. We then created 3 categories of foreclosure change, which we labeled (1) decrease, (2) no change or small increase, and (3) large increase. We followed this same process for all 3 foreclosure types—notices of default, auction, and REO. We used the middle category—no change or small increase—as our reference group because it was the largest and most representative category with which to compare the effect of large increases in foreclosures rates. Note that we log-transformed household assets to address nonnormality in this variable. Finally, we examined multicollinearity among our socioeconomic measures with pairwise correlations and computation of variance inflation factors for each of our 3 models. The results indicated that multicollinearity was not a threat to our findings—pairwise correlations were low, and most variance inflation factors were between 1 and 2 (with the highest at 2.31), far below the benchmark of 5.33

RESULTS

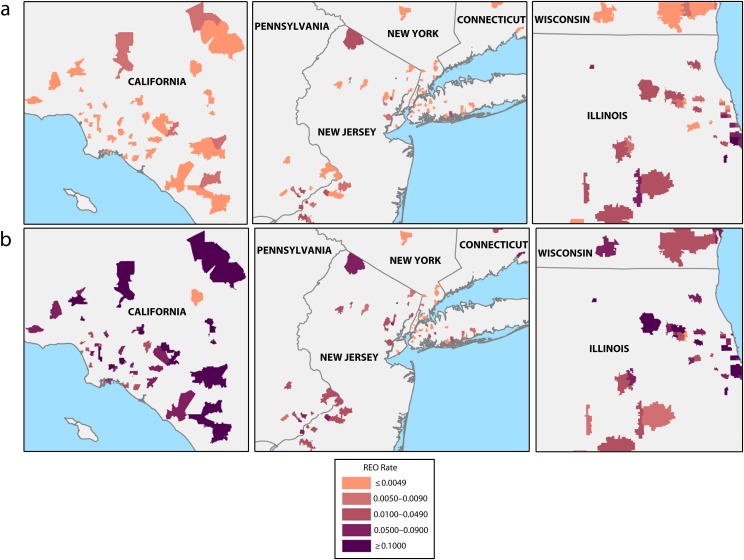

Figure 2 illustrates foreclosure change, using the 3 largest metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) where NSHAP respondents resided—Los Angeles, California; New York, New York; and Chicago, Illinois. Note that the NSHAP data source was nationally representative and not limited to urban areas; we drew on these 3 urban centers for illustration since we had more clustering of respondents in these 3 places. For these purposes, we focused on REO properties, the largest foreclosure type in our sample, and show changes in REO foreclosure rates by zip code for these MSAs. The clusters within each of the 3 MSAs were primary sampling units for the NSHAP sampling frame. We observed a dramatic uptick over the interval for Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles MSAs, with perhaps the greatest change in Los Angeles, where only 1 zip code appeared unaffected by the foreclosure crisis. Although representing a subset of respondents, these initial descriptive data suggest that NSHAP participants were living in communities that had undergone substantial structural change in the housing market.

FIGURE 2—

Annual rates of real-estate–owned (REO) households, by zip code, for (a) wave 1 (2005–2006) and (b) wave 2 (2010–2011): National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project, United States.

Table 1 includes descriptive data for NSHAP respondents at both waves and for changes over the 2 waves. Data on education, age, race, household assets, and marital status indicate that these data were nationally representative.34 Notably, about 10% of NSHAP respondents who did not report significant depressive symptoms in W1 reported such symptoms in W2. We also saw a small increase in respondents’ neighborhood disorder (0.06) and a 2% increase in percentage poor.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of the Study Sample: National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project; United States; Waves 1 (2005–2006) and 2 (2010–2011)

| Variable | Range | % (No.) or Mean ±SD | % Observeda |

| Became depressed between W1 and W2 | 0 or 1 | 9.97 (195) | 97.30b |

| Annual percentage receiving notices | 1 to 3 | 100.00 | |

| Decrease | −0.002 to −0.000 | 20.77 (483) | |

| No change or small increase | 0 to 0.0003 | 42.23 (983) | |

| Large increase | 0.0003 to 0.009 | 37.00 (861) | |

| Annual percentage auctioned | 1 to 3 | 100.00 | |

| Decrease | −0.002 to −0.000 | 13.98 (325) | |

| No change or small increase | 0 to 0.001 | 44.73 (1041) | |

| Large increase | 0.001 to 0.018 | 41.29 (961) | |

| Annual percentage REO | 1 to 3 | 96.99 | |

| Decrease | −0.192 to −0.000 | 9.77 (222) | |

| No change or small increase | 0 to 0.029 | 46.18 (1047) | |

| Large increase | 0.029 to 1.731 | 44.05 (999) | |

| Judicial foreclosure process | 0 or 1 | 42.57 (991) | 100.00 |

| Change in tract % poor | −28.28 to 25.64 | 1.97 ±5.66 | |

| Change in neighborhood disorderc | −3 to 3 | 0.06 ±0.64 | |

| Female | 0 or 1 | 52.19 (1215) | 100.00 |

| Race/ethnicity | 1 to 3 | 99.56 | |

| White | 83.47 (1936) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 9.52 (221) | ||

| Hispanic | 7.01 (162) | ||

| Age, y | 1 to 3 | 100.00 | |

| 63–69 | 45.01 (1048) | ||

| 70–79 | 35.67 (830) | ||

| 80–90 | 19.32 (450) | ||

| Education | 1 to 4 | 100.00 | |

| < high school | 15.79 (368) | ||

| High school | 25.49 (593) | ||

| Some college | 31.96 (744) | ||

| ≥ bachelor’s degree | 26.76 (623) | ||

| Change in log of assets | −6.99 to 10.82 | −0.04 ±1.42 | 46.09 |

| Unemployed (W2) | 0 or 1 | 2.14 (50) | 99.77 |

| Moved between W1 and W2 | 0 or 1 | 21.92 (510) | 100.00 |

| Partner transitions between W1 and W2 | 1 to 4 | 100.00 | |

| Stayed partnered | 62.81 (1462) | ||

| Gained partner | 1.67 (39) | ||

| Lost partner | 8.98 (209) | ||

| Stayed unpartnered | 26.54 (618) | ||

| Transitions in ADL limitations | 1 to 3 | 100.00 | |

| None, W1 and W2 | 77.86 (1812) | ||

| W1 and W2 | 2.83 (66) | ||

| New limitations in W2 | 19.30 (449) |

Note. ADL = activities of daily living; REO = real-estate–owned; W1 = wave 1; W2 = wave 2. The total weighted sample was n = 2261.

Calculated as 100 × (observed/2261), where 2261 is the total number of returning respondents.

Calculated on the basis of the number of cases where depression scores at W1 and W2 could be determined (2200/2261).

The disorder scale comprised 2 items: (1) How well kept is the building in which the respondent lives? and (2) How well kept are most of the buildings on the street (1 block, both sides) where the respondent lives? Possible responses were very poorly kept (needs major repairs), poorly kept (needs minor repairs), fairly well kept (needs cosmetic work), and very well kept. The scale ranges from 0 to 3 at both W1 and W2, and change scores accordingly range from –3 to 3.

Table 2 includes logistic regressions predicting the development of significant depressive symptoms between W1 and W2; this was the critical period (between 2005–2006 and 2010–2011) when these respondents, like the rest of the country, were exposed to the economic downturn.

TABLE 2—

Results of Multivariable Analysis Predicting the Development of Significant Depressive Symptoms Between Wave 1 (2005–2006) and Wave 2 (2010–2011), Using 3 Stages in the Foreclosure Process: National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project, United States

| Variable | Notices of Default, OR (95% CI) | Auctions, OR (95% CI) | REO, OR (95% CI) |

| Annual % foreclosure | |||

| Decrease | 1.24 (0.78, 1.97) | 1.00 (0.61, 1.64) | 1.32 (0.83, 2.13) |

| No change or small increase (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Large increase | 1.75* (1.14, 2.67) | 1.45 (0.96, 2.19) | 1.62* (1.06, 2.47) |

| Judicial foreclosure process | 1.04 (0.66, 1.65) | 1.13 (0.70, 1.83) | 1.14 (0.70, 1.84) |

| Change in tract % poor | 1.11 (0.96, 1.28) | 1.09 (0.94, 1.25) | 1.09 (0.94, 1.26) |

| Change in neighborhood disorder | 0.99 (0.82, 1.21) | 0.99 (0.81, 1.20) | 0.99 (0.81, 1.21) |

| Female | 1.23 (0.87, 1.73) | 1.21 (0.86, 1.71) | 1.23 (0.87, 1.73) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.12 (0.64, 1.95) | 1.11 (0.63, 1.96) | 1.12 (0.64, 1.95) |

| Hispanic | 1.09 (0.55, 2.16) | 1.06 (0.50, 2.23) | 1.09 (0.55, 2.16) |

| Age at W1, y | |||

| 63–69 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 70–79 | 1.43 (0.98, 2.08) | 1.44 (0.99, 2.09) | 1.45 (1.00, 2.09) |

| 80–90 | 1.81* (1.13, 2.90) | 1.82* (1.14, 2.91) | 1.84* (1.16, 2.92) |

| Education | |||

| < high school (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| High school | 0.95 (0.53, 1.71) | 0.96 (0.52, 1.75) | 0.99 (0.54, 1.80) |

| Some college | 0.64 (0.38, 1.08) | 0.65 (0.38, 1.10) | 0.65 (0.39, 1.09) |

| ≥ bachelor’s degree | 0.44* (0.22, 0.90) | 0.41* (0.20, 0.84) | 0.42* (0.21, 0.83) |

| Change in log of assets | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) |

| Unemployed (W2) | 1.40 (0.32, 6.02) | 1.46 (0.34, 6.26) | 1.46 (0.33, 6.43) |

| Moved between W1 and W2 | 1.21 (0.75, 1.94) | 1.17 (0.74, 1.86) | 1.15 (0.72, 1.85) |

| Partner transitions between W1 and W2 | |||

| Stayed partnered (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Gained partner | 0.63 (0.14, 2.78) | 0.69 (0.15, 3.10) | 0.67 (0.15, 3.07) |

| Lost partner | 1.61 (0.90, 2.89) | 1.59 (0.89, 2.84) | 1.61 (0.89, 2.91) |

| Stayed unpartnered | 1.29 (0.82, 2.02) | 1.33 (0.85, 2.09) | 1.36 (0.87, 2.11) |

| Transitions in ADL limitations | |||

| None, W1 and W2 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| W1 and W2 | 1.01 (0.30, 3.47) | 0.96 (0.28, 3.34) | 0.98 (0.28, 3.44) |

| New limitations in W2 | 1.86** (1.20, 2.90) | 1.84** (1.17, 2.88) | 1.85** (1.18, 2.90) |

| Constant | 0.06** (0.03, 0.12) | 0.07** (0.03, 0.13) | 0.06** (0.03, 0.12) |

Note. ADL = activities of daily living; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; REO = real-estate–owned; W1 = wave 1; W2 = wave 2. All continuous variables were standardized. The estimation sample was n = 1883.

*P < .05; **P < .01.

For all 3 stages of the foreclosure process, residing in an area that underwent an increase in the percentage of housing stock foreclosed increased the risk of developing significant depressive symptoms (for notices of default, OR = 1.75; 95% CI = 1.14, 2.67; for auctions, OR = 1.45; 95% CI = 0.96, 2.19; for REO, OR = 1.62; 95% CI = 1.06, 2.47). We note that change in neighborhood disorder was not related to depressive symptoms in unadjusted analyses (results not shown). In terms of control variables, adults in the oldest age category were more likely to develop significant depressive symptoms between the 2 waves, with, for example, an OR of approximately 1.84 in the REO category (95% CI = 1.16, 2.92). Adults with a bachelor’s degree or more were less likely to develop significant depressive symptoms (OR = 0.42; 95% CI = 0.21, 0.83). Individuals who developed limitations in activities of daily living between the 2 waves were significantly more likely to experience new significant depressive symptoms, with an OR of approximately 1.85 (95% CI = 1.18, 2.90). Results for these controls were consistent with previous literature on the development of depression at older ages.35

DISCUSSION

Foreclosure not only affects individual households, its reach is felt by those who are left with lower-density communities, properties in disrepair, and a general sense of disinvestment and social withdrawal. Extant literature indicates that physical signs of disorder are associated with reports of depression.5,36 Consistent with these findings, we observed a dramatic uptick in reports of depressive symptoms among older adults who were exposed to communities most severely affected by the foreclosure crisis. We observed this increase in analyses of all 3 foreclosure stages, lending support to the claim that neighborhood-level foreclosure activity is influential in reports of emotional well-being. Although not significant at the conventional threshold of P < .05, we note that the finding on auctions (OR = 1.45; P < .077) was in the expected direction and was consistent with the pattern observed for the other two forms of foreclosure. We emphasize that the respondents in our analysis did not report depressive symptomatology in W1, prior to the economic downturn. Interestingly, increases in neighborhood poverty and visible disorder were not statistically significant, suggesting that neither of these contextual factors was important to the mechanism connecting foreclosure and depression. This result is consistent with recent findings in the social sciences suggesting that the impact of foreclosure on communities is independent of disorder.37 We speculate that foreclosure is a sign of disorder in its own right; a posting of foreclosure, regardless of the quality of the property in arrears, signals instability and disinvestment akin to trash on the street or sidewalks in disrepair. Thus, foreclosure can embody components of disorder even when it may not immediately lead to other visible forms of disorder, such as a dilapidated porch or a broken picture window.

To our knowledge, this analysis is the first of its kind to examine community-level foreclosure rates and the mental health of older adult residents. We argue that a focus on older adults is important given the likelihood of longer residential tenure and attachment to community and neighbors. We surmise that a threat to a neighborhood’s fabric may be more rapidly internalized by this population group. Data linkages such as this one—a national social survey with national data on foreclosure—are critical to examining the extent to which changes in economic circumstances affect individual-level health status. Our constructed data source provided a temporal advantage, allowing us to examine how changes in foreclosure led to onset of depressive symptoms.

Although the NSHAP data source is novel, it is limited in its ability to address some questions pertinent to this body of research. First, the range of neighborhood measures in the NSHAP could be more comprehensive, including other characteristics of the social and physical space that NSHAP respondents inhabit and more precise indicators of physical and social disorder. We hope that the NSHAP study will continue to expand its set of neighborhood context measures. Second, although the focus on older adults is an appealing feature of the NSHAP, comparisons across age are not possible. Future investigations of the relationship between the foreclosure crisis and depression onset should include comparisons across age categories. Third, analyses could examine smaller units than zip codes. The RealtyTrac data source is currently not coded at smaller units of aggregation, but researcher demand or other incentives might alter the data products available in the near future. We note, too, that zip codes only approximate neighborhoods. Qualitative investigations aimed at smaller, defined neighborhood spaces could provide additional insight into the mechanisms linking increases in foreclosure to depressive symptoms. Fourth, we were not able to ascertain whether the respondent, or those in his or her social network, was experiencing foreclosure. Certainly the proximity of the experience could have implications for mental health. Our control for household assets helped in some manner to alleviate this concern, but of course it did not capture what might be occurring in one’s close social network. Network-based analyses of the impact of foreclosure would be a fruitful pursuit, but unfortunately these analyses were not possible with these data. Finally, extensions of this research could examine other measures of emotional well-being and, in time, the physical symptoms that might manifest themselves as communities experience decline.

Older residents in neighborhoods with high rates of foreclosure may need additional supports to maintain community residence and weather the effects of the economic downturn. At the individual level, these supports may manifest themselves in policies designed to assist those at risk for foreclosure, including property tax abatement and mortgage loan refinancing with the original lender. At the neighborhood level, communities may want to consider how best to manage distressed and abandoned properties so they do not introduce physically or socially compromised spaces that older adults must navigate. At the municipal level, communities may choose to approach the foreclosure crisis with a particular policy prescription that applies to a range of homeowners. Richmond, California, for instance, is now pursuing a strategy whereby the city invokes its eminent domain power (used in other circumstances to improve municipal infrastructure or develop new projects) to buy at-risk mortgages at market value and resell them to their original holders at a lower price.38 Efforts such as these could contribute to prevention, since residents could readily observe action and activities meant to benefit the community as a whole.

The costs of depression are difficult to assess, but depression’s impact has been documented in lost work days, physical health decline, and degraded social relationships.36,39 Older adults who experience depressive symptoms may be particularly vulnerable to these associated ills since their health already may be compromised. Our results suggest that some portion of depression onset in older adults is yet another consequence of the Great Recession.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health, including the National Institute on Aging, the Office of Women’s Health Research, the Office of AIDS Research, the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, and the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development for the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP; R01AG021487 and R37AG030481); the NSHAP Wave 2 Partner Project (R01AG033903); the Center on the Demography and Economics of Aging (P30AG012857); and the Population Research Center (R24HD051152).

We are grateful to Linda Waite, Elyzabeth Gaumer, Kristen Schilt, and Mario Small for very helpful comments on an earlier version of this article and to Tyler White of RealtyTrac for assistance with the foreclosure data. We also thank our NSHAP colleagues for feedback throughout the development of this work.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was received from both the University of Chicago and the National Opinion Research Center.

References

- 1.Immergluck D, Smith G. Measuring the effects of subprime lending on neighborhood foreclosures: evidence from Chicago. Urban Aff Rev. 2005;40(3):362–389. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leonard T, Murdoch J. The neighborhood effects of foreclosure. J Geogr Syst. 2009;11(4):317–322. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davalos ME, French MT. This recession is wearing me out! Health-related quality of life and economic downturns. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2011;14(2):61–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuijpers P, Aartjan TF, Beekman TF, Reynolds CF. Preventing depression: a global priority. JAMA. 2012;307(10):1033–1034. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross CE. Neighborhood disadvantage and adult depression. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(2):177–187. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Currie J, Tekin E. Is there a link between foreclosure and health? 2011. NBER Working Paper No. 17310. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w17310. Accessed May 18, 2013.

- 7.Trawinski LA. Nightmare of Main Street: Older Americans and the Mortgage Market Crisis. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bricker J, Kennickell AB, Moore KB, Sabelhaus J. Changes in US family finances from 2007 to 2010: evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Fed Reserve Bull. 2010;98(2):1–80. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cagney KA, Browning CR, Jackson AL, Soller B. Social network, neighborhood and institutional effects in aging research: an integrated “activity space” approach to examining social context. In: Waite L, editor. New Directions in Social Demography: Social Epidemiology and the Sociology of Aging. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matheson FI, Moineddin R, Dunn JR, Creatore MI, Gozdyra P, Glazier RH. Urban neighborhoods, chronic stress, gender and depression. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(10):2604–2616. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Latkin CA, Curry A. Stressful neighborhoods and depression: a prospective study of the impact of neighborhood disorder. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(1):34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galea S, Ahern J, Nandi A, Traci M, Beard J, Vlahov D. Urban neighborhood poverty and the incidence of depression in a population based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(3):171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Echeverria S, Diez-Roux AV, Shea S, Borrell LN, Jackson S. Associations of neighborhood problems and neighborhood social cohesion with mental health and health behaviors: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Health Place. 2008;14(4):853–865. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sampson RJ. Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Immergluck D, Smith G. The impact of single-family mortgage foreclosures on neighborhood crime. Housing Stud. 2006;21(6):851–866. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Seeing disorder: neighborhood stigma and the social construction of “broken windows.”. Soc Psychol Q. 2004;67(4):319–342. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skogan WG. Disorder and Decline: Crime and the Spiral of Decay in American Neighborhoods. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson EE, Krause N. Living alone and neighborhood characteristics as predictors of social support in late life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53(6):S354–S364. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.6.s354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krause N. Neighborhood deterioration and social isolation in later life. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1993;36(1):9–38. doi: 10.2190/UBR2-JW3W-LJEL-J1Y5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York, NY: Random House; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzman R. The National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project: an introduction. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(suppl 1):i5–i11. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Muircheartaigh C, Eckman S, Smith S. Statistical design and estimation for the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(suppl 1):i12–i19. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanson BS, Isacsson SO, Janzon L, Lindell SE. Social support and quitting smoking for good: is there an association? Results from the Population Study, “Men Born in 1914,” Malmö, Sweden. Addict Behav. 1990;15(3):221–233. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. RealtyTrac. Available at: http://www.realtytrac.com. Accessed June 6, 2012.

- 25.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5(2):179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charles KK, DeCicca P. Local labor market fluctuations and health: is there a connection and for whom? J Health Econ. 2008;27(6):1532–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31(12):721–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb03391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chemerinski E, Robinson RG, Kosier JT. Improved recovery in activities of daily living associated with remission of poststroke depression. Stroke. 2001;32(1):113–117. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-InterScience; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allison P. Missing Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long JS, Freese J. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables Using Stata. 2nd ed. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton LC. Stata Multiple-Imputation Reference Manual: Release 12. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon RA. Applied Statistics for the Social and Health Sciences. New York, NY: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34. US Census Bureau. Available at: http://www.census.gov. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- 35.Harris T, Cook DG, Victor C, DeWilde S, Beighton C. Onset and persistence of depression in older people—results from a 2-year community follow-up study. Age Ageing. 2006;35(1):25–32. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Demakakos P, Pierce MB, Hardy R. Depressive symptoms and risk of type 2 diabetes in a national sample of middle-aged and older adults. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(4):792–797. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallace D, Hedberg EC, Katz CM. The impact of foreclosures on neighborhood disorder before and during the housing crisis: testing the spiral of decay. Soc Sci Q. 2012;93(3):625–647. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dreier P. To rescue local economies, cities seize underwater mortgages through eminent domain. The Nation. July 12, 2013. Available at: http://www.thenation.com/article/175244/rescue-local-economies-cities-seize-underwater-mortgages-through-eminent-domain. Accessed July 12, 2013.

- 39.Kessler RC. The costs of depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]