Abstract

Objectives. We examined national patterns in adult diet-beverage consumption and caloric intake by body-weight status.

Methods. We analyzed 24-hour dietary recall with National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2010 data (adults aged ≥ 20 years; n = 23 965).

Results. Overall, 11% of healthy-weight, 19% of overweight, and 22% of obese adults drink diet beverages. Total caloric intake was higher among adults consuming sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) compared with diet beverages (2351 kcal/day vs 2203 kcal/day; P = .005). However, the difference was only significant for healthy-weight adults (2302 kcal/day vs 2095 kcal/day; P < .001). Among overweight and obese adults, calories from solid-food consumption were higher among adults consuming diet beverages compared with SSBs (overweight: 1965 kcal/day vs 1874 kcal/day; P = .03; obese: 2058 kcal/day vs 1897 kcal/day; P < .001). The net increase in daily solid-food consumption associated with diet-beverage consumption was 88 kilocalories for overweight and 194 kilocalories for obese adults.

Conclusions. Overweight and obese adults drink more diet beverages than healthy-weight adults and consume significantly more solid-food calories and a comparable total calories than overweight and obese adults who drink SSBs. Heavier US adults who drink diet beverages will need to reduce solid-food calorie consumption to lose weight.

The trends and patterns of sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption have been well described in the literature,1,2 but less is known about consumption of diet beverages (artificially sweetened no-calorie drinks) among US adults. Available evidence focuses on broad temporal trends or changes among demographic groups suggesting that consumption of diet beverages has increased dramatically from about 3% of adults in 19653 to about 20% of adults today,4 and that diet-beverage drinkers are typically characterized as young to middle-age adults (aged 20–59 years), female, non-Hispanic White, and higher income.4

To our knowledge, no studies to date have focused on national patterns in diet-beverage consumption and caloric intake by body-weight status. Understanding diet-beverage consumption by body weight is important as consuming these zero- or no-calorie drinks is a common weight-management strategy. Switching from SSBs to diet drinks has indeed been shown to be associated with weight loss because of differences in caloric content between the drinks.5 However, the evidence base is far from conclusive. Some studies, mostly cross-sectional in design, have shown that diet-beverage drinkers tend to be overweight,5,6 that they typically do not consume fewer calories on the days they consume diet beverages,7 and that high consumers (households purchasing more than 20 12-packs of diet soda annually) generally purchase more snack foods at the grocery store and more overall calories than consumers purchasing SSBs.8 The evidence from long-term studies is similarly mixed; some show the reduction in caloric intake promotes weight loss or maintenance, others show no effect, and some show weight gain.9 Evidence also suggests that diet drinkers have the same caloric intake and body mass index (BMI; defined as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters) as SSB drinkers10,11 and that consumption of diet drinks can be associated with significant weight gain.12

The primary purpose of this study was to describe patterns in diet-beverage consumption and caloric intake (total, beverage, and solid-food calories) among US adults overall and among body-weight categories. In addition, we examined variations in dietary habits (i.e., snacking and calories per meal occasion) among adults consuming diet beverages. This analysis does not attempt to estimate the impact of diet-beverage intake on obesity incidence because of our reliance on cross-sectional data.

METHODS

We obtained data from the nationally representative continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999–2010). The NHANES is a population-based survey designed to collect information on the health and nutrition of the US population. Participants were selected through a multistage, clustered, probability sampling strategy. Our analysis combined the continuous NHANES data collection (1999–2010) to look at overall patterns during that time period. A complete description of data-collection procedures and analytic guidelines are available elsewhere (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm).

The study sample consisted of adults aged 20 years and older with completed 24-hour dietary recalls. Survey respondents were excluded if they were pregnant or had diabetes at the time of data collection or if their dietary recall was incomplete or unreliable (as determined by the NHANES staff).

Measures

Beverages and snacks.

Survey respondents reported all food and beverages consumed in a previous 24-hour period (midnight to midnight) and reported type, quantity, and time of each food and beverage consumption occasion. Following the dietary interview, all reported food and beverage items were systemically coded with the US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrient Database. Caloric content and other nutrients derived from each consumed food or beverage item were calculated based on the quantity of food and beverages reported and the corresponding nutrient contents by the National Center for Health Statistics. We only used the first dietary recall from each survey for this analysis.

We identified 5 mutually exclusive beverage categories in the NHANES 1999–2010 (from 162 beverage items): (1) SSBs (nondiet soda, sport drinks, fruit drinks and punches, low-calorie drinks, sweetened tea, and other sugar-sweetened beverages), (2) diet beverages, (3) alcohol, (4) 100% juice, and (5) milk (including flavored milk).13 (See Appendix A, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org.) Of note, the number of items in each beverage category was calculated from NHANES 2007–2010, but includes all items from 1999 to 2010. Also, some milk, coffee or tea, or alcohol beverages may have added sugar.

We identified 2 mutually exclusive snack categories in the NHANES 1999–2010 (from 772 snack items): (1) salty snacks, including hush puppies, all types of chips, popcorn, pretzels, party mixes, french fries, and potato skins (76 items) and (2) sweet snacks, including ice cream, other desserts (e.g., custards, puddings, mousse), sweet rolls, cakes, pastries (e.g., crepes, cream puffs, strudels, croissants, muffins, sweet breads), cookies, pies, and candy (696 items). The sweet-snack category did not include solid foods with naturally occurring sugar such as fruit. (See Appendix B, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Body-weight status.

In the NHANES, weight and height were measured via standard procedures in a mobile examination center. Healthy weight was defined as having a BMI from 18.5 kg/m2 to 24.99 kg/m2; overweight, BMI from 25 kg/m2 to 29.99 kg/m2; and obese, BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2.14

Socioeconomic status.

The poverty–income ratio—the ratio of household income to a family’s appropriate poverty threshold—was based on self-reported household income. We dichotomized the poverty–income ratio into lower- and higher-income groups on the basis of eligibility for food assistance programs (i.e., ≤ 130% of the poverty level). We categorized education into 3 mutually exclusive categories: (1) less than high school, (2) high school (or GED), and (3) more than high school.

Analysis.

We weighted all analyses to be representative of the general population and conducted them with Stata, version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) to account for the complex sampling structure. For each of the outcome variables—percentage of drinkers and energy intake (overall, solid food, beverages, sweet snacks, salty snacks)—we used multiple regressions to adjust for potential differences in population characteristics across the body-weight and beverage categories, including race/ethnicity, gender, income, age, marital status, employment status, and education. For the binary outcomes (percentage drinkers), we used Logit models. For continuous outcomes (energy intake), we used ordinary least squares models. Using postestimation commands, we calculated the predicted percentage of beverage drinkers and the predicted number of calories for energy intake overall and for each subcategory of energy intake (solid food, beverages, sweet snacks, salty snacks). As consumption patterns may vary depending on the day of the week, we also controlled for whether the surveyed day was a weekday or weekend. Of note, we did not perform separate analyses for individuals who consumed multiple beverage types as the overlap between categories was very small; for example, only 4.4% of our sample reported consuming both SSBs and diet beverages.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the NHANES 1999–2010 sample are presented in Table 1, overall and by body-weight category. The categories of body weight had comparable distributions of employment status and the day of the week the respondents completed the survey. The obese category had more women, non-Hispanic Blacks and Mexican Americans, middle-aged adults (45–64 years), less-educated individuals (≤ high-school education), married persons, and lower-income adults (P < .05).

TABLE 1—

Overall and Body-Weight Characteristics of US Adults Aged 20 Years and Older: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2010

| Characteristics | Total, No. (%) | Healthy Weight, No. (%) | Overweight, No. (%) | Obese, No. (%) | P for Difference |

| Total | 23 965 (100) | 7438 (33) | 8662 (35) | 7865 (31) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 12 052 (49) | 3537 (43) | 4973 (58) | 3542 (47) | <.001 |

| Female | 11 913 (51) | 3901 (57) | 3689 (42) | 4323 (53) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 12 152 (72) | 4151 (74) | 4371 (72) | 3630 (69) | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4534 (11) | 1220 (9) | 1432 (9) | 1882 (14) | |

| Mexican American | 6358 (13) | 1625 (10) | 2582 (14) | 2151 (13) | |

| Othera | 921 (5) | 442 (7) | 277 (4) | 202 (3) | |

| Age, y | |||||

| 20–44 | 10 888 (52) | 3819 (58) | 3578 (48) | 3491 (50) | <.001 |

| 45–64 | 7498 (34) | 1878 (28) | 2816 (35) | 2804 (38) | |

| ≥ 65 | 5579 (14) | 1741 (13) | 2268 (17) | 1570 (13) | |

| Education | |||||

| < high school | 6880 (18) | 1932 (17) | 2621 (19) | 2327 (19) | <.001 |

| High school diploma or GED | 5781 (25) | 1744 (24) | 2038 (25) | 1999 (28) | |

| > high school | 11 271 (57) | 3744 (60) | 3993 (55) | 3534 (53) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Currently married | 12 801 (58) | 3643 (53) | 4896 (61) | 4262 (60) | <.001 |

| Previously married | 5087 (17) | 1530 (17) | 1836 (18) | 1721 (18) | |

| Living with a partner | 1652 (7) | 561 (8) | 580 (7) | 511 (6) | |

| Never married | 4046 (18) | 1592 (22) | 1197 (15) | 1257 (16) | |

| Employment status | |||||

| Unemployed | 8410 (32) | 2620 (33) | 2989 (31) | 2801 (33) | .036 |

| Employed | 12 077 (68) | 3670 (67) | 4425 (69) | 3982 (67) | |

| Incomeb | |||||

| Lower income | 6197 (20) | 1894 (20) | 2149 (18) | 2154 (21) | .002 |

| Higher income | 15 870 (80) | 4934 (80) | 5804 (82) | 5132 (79) | |

| Day of week surveyed | |||||

| Weekday | 14 896 (62) | 4613 (62) | 5358 (61) | 4925 (62) | .759 |

| Weekend | 9069 (38) | 2825 (38) | 3304 (39) | 2940 (38) |

Note. GED = general equivalency diploma. Healthy weight = body mass index (BMI) 18.5–24.99 kg/m2; overweight = BMI 25–29.99 kg/m2; obese = BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. Percentage of US population estimated with survey weights to adjust for unequal probability of sampling P value measured at the .05 level.

Other includes non-Hispanic multiracial and any other non-Hispanic race categories not included in the listed categories.

Income level was dichotomized based on the poverty index ratio (ratio of annual family income to federal poverty line). Lower income refers to persons below 130% of poverty, which represents eligibility threshold for the federal food stamp program.

Overall Beverage Consumption

Table 2 reports the percentage of adults consuming beverages on a typical day. Overall, 61% of adults consumed SSBs and 15% of adults consumed diet beverages. Overweight and obese adults were more likely to consume diet beverages than were healthy-weight adults, and obese adults were more likely to consume diet beverages than overweight adults (healthy weight: 11%; overweight: 19%; and obese: 22%; P < .05). Overweight and obese adults were also significantly more likely to consume SSBs compared with healthy-weight adults (63% vs 59%; P < .05). For all other beverage categories (alcohol, juice, and milk), significantly fewer obese adults consumed those beverages than healthy-weight adults (P < .05).

TABLE 2—

Percentage of US Adults (Aged 20 Years and Older) Consuming Various Beverages on the Surveyed Day: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2010

| Beverage Consumed | Total, Mean ±SE | Healthy Weight, Mean ±SE | Overweight, Mean ±SE | Obese, Mean ±SE |

| Sugar-sweetened | 61 ±1 | 59 ±1 | 63* ±1 | 63* ±1 |

| Diet | 15 ±1 | 11 ±1 | 19* ±1 | 22*,** ±1 |

| Alcohol | 26 ±1 | 28 ±1 | 23* ±1 | 18*,** ±1 |

| 100% juice | 20 ±1 | 21 ±1 | 19 ±1 | 18*,** ±1 |

| Milk | 46 ±1 | 47 ±1 | 45 ±1 | 42*,** ±1 |

Note. Healthy weight = body mass index (BMI) 18.5–24.99 kg/m2; overweight = BMI 25–29.99 kg/m2; obese = BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. Multivariate regression was used to adjust for gender, race/ethnicity, education, body-weight category, marital status, income, employment status, weekend or weekday, and other beverages consumed.

*Difference from healthy-weight group significant at P < .05; **difference between overweight and obese groups significant at P < .05.

Consumption of Total, Beverage, and Solid-Food Calories

Table 3 presents the caloric consumption (total, beverage, and solid-food kcal) associated with consuming each type of beverage, overall and by body-weight category. On a typical day, adults drinking SSBs consumed a total of 2351 kilocalories and adults drinking diet beverages consumed 2203 kilocalories. Among SSB drinkers, obese adults consumed significantly more total calories than did overweight adults (2305 kcal/day vs 2266 kcal/day; P < .05). Among diet-beverage drinkers, who presumably are more conscious about calories, total caloric consumption increased significantly by body weight with overweight and obese adults consuming more than healthy-weight adults and obese adults consuming more than overweight adults (healthy weight: 2095 kcal/day; overweight: 2196 kcal/day; obese: 2280 kcal/day; P < .05). Among milk drinkers, overweight adults consumed significantly fewer total calories than healthy-weight adults (2241 kcal/day vs 2315 kcal/day; P < .05).

TABLE 3—

Associations of Caloric Intake Among US Adults (Aged 20 Years and Older) With Consuming Various Beverages on the Surveyed Day: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2010

| Beverage Consumed | Total, Mean ±SE | Healthy Weight, Mean ±SE | Overweight, Mean ±SE | Obese, Mean ±SE |

| Sugar-sweetened | ||||

| Solid food, kcal | 1938 ±27 | 1908 ±18 | 1874 ±19 | 1897 ±20 |

| Beverage, kcal | 414 ±11 | 394 ±9 | 392 ±7 | 408*,** ±9 |

| Total, kcal | 2351 ±31 | 2302 ±20 | 2266 ±22 | 2305** ±23 |

| Diet | ||||

| Solid food, kcal | 1950 ±42 | 1841 ±39 | 1965* ±38 | 2058*,** ±34 |

| Beverage, kcal | 258 ±19 | 262 ±18 | 231 ±12 | 225 ±13 |

| Total, kcal | 2203 ±42 | 2095 ±42 | 2196 ±43 | 2280*,** ±37 |

| Alcohol | ||||

| Solid food, kcal | 1888 ±30 | 1849 ±27 | 1828 ±26 | 1847 ±29 |

| Beverage, kcal | 588 ±22 | 581 ±14 | 592 ±12 | 596 ±17 |

| Total, kcal | 2479 ±33 | 2430 ±32 | 2420 ±32 | 2442 ±32 |

| 100% juice | ||||

| Solid food, kcal | 2096 ±38 | 2059 ±34 | 2015 ±29 | 2057 ±29 |

| Beverage, kcal | 298 ±17 | 272 ±13 | 293 ±12 | 299 ±14 |

| Total, kcal | 2382 ±43 | 2308 ±38 | 2315 ±33 | 2355 ±34 |

| Milk | ||||

| Solid food, kcal | 2048 ±27 | 2051 ±21 | 1948 ±24* | 1980 ±23** |

| Beverage, kcal | 308 ±10 | 275 ±8 | 296 ±8 | 302 ±9* |

| Total, kcal | 2339 ±29 | 2315 ±22 | 2241 ±25* | 2270 ±23 |

Note. Healthy weight = body mass index (BMI) 18.5–24.99 kg/m2; overweight = BMI 25–29.99 kg/m2; obese = BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. Multivariate regression was used to adjust for gender, race/ethnicity, education, body-weight category, marital status, income, employment status, weekend or weekday, and other beverages consumed.

*Difference from healthy-weight group significant at P < .05; **difference between overweight and obese groups significant at P < .05.

Among diet-beverage drinkers, consumption of solid-food calories increased significantly with each body-weight category (healthy weight: 1841 kcal/day; overweight: 1965 kcal/day; obese: 2058 kcal/day; P < .05). Also among diet-beverage drinkers, consumption of beverage calories did not differ significantly, regardless of body-weight status. Among SSB drinkers, obese adults consumed significantly more beverage calories than overweight and healthy-weight adults (healthy weight: 394 kcal/day; overweight: 392 kcal/day; obese: 408 kcal/day; P < .05).

When we compared SSB drinkers to diet drinkers (significance not indicated in the table), we also observed differences by body-weight category. On a typical day, adults drinking SSBs consumed significantly more total calories than adults drinking diet beverages (2351 kcal/day vs 2203 kcal/day; P = .005). However, the difference in total caloric intake between SSB and diet drinkers was only significant for healthy-weight adults (2302 kcal/day vs 2095 kcal/day; P < .001); the patterns were similar among overweight (2266 kcal/day vs 2196 kcal/day; P = .15) and obese adults (2305 kcal/day vs 2280 kcal/day; P = .57). Overweight and obese adults who drank diet beverages consumed significantly more calories from solid food than overweight and obese adults who drank SSBs (overweight diet drinkers vs SSB drinkers: 1965 kcal/day vs 1874 kcal/day; P = .04; obese diet drinkers vs SSB drinkers: 2058 kcal/day vs 1897 kcal/day; P < .001). Consumption of beverage calories was significantly lower among diet-beverage drinkers compared with SSB drinkers overall (258 kcal/day vs 414 kcal/day; P < .001) and for each body-weight category (healthy weight: 262 kcal/day vs 394 kcal/day; P < .001; overweight: 231 kcal/day vs 392 kcal/day; P < .001; obese: 225 kcal/day vs 408 kcal/day; P < .001).

Change in Solid-Food Intake

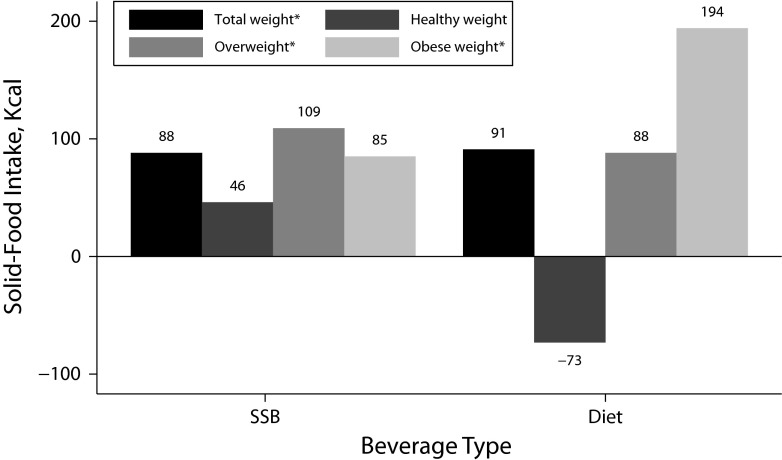

Figure 1 presents the change in solid-food intake among adults associated with consuming each beverage type after adjustment for all other beverages, overall and by body-weight categories. To estimate these numbers, we stratified by body-weight category and modeled the relationship between all beverage types and solid-food calories to determine if different levels of food intake were associated with adults consuming SSBs or diet beverages. The figure reports the predicted net change (difference from zero) in solid calories associated with drinking SSBs and diet beverages.

FIGURE 1—

Net change in solid-food intake associated with drinking sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) and diet beverages among US adults (aged ≥ 20 years) by weight status: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2010.

Note. Diet = diet beverage; SSB = sugar-sweetened beverage.

*P = .05.

Overall, being an SSB drinker was associated with a net increase of 88 more solid kilocalories per day and being a diet drinker was associated with net increase of 91 more solid kilocalories per day (P < .05). Among SSB drinkers, the net increase in calories from solid food was significantly higher among overweight and obese adults compared with healthy-weight adults (healthy weight: 46 kcal/day; overweight: 109 kcal/day; obese: 85 kcal/day; P < .05). Among diet-beverage drinkers, the net increase in solid-food consumption was significantly lower for healthy-weight adults and significantly higher for overweight and obese adults (healthy weight: –73 kcal/day; overweight: 88 kcal/day; obese: 194 kcal/day; P < .05). We observed no differences in the net increase in solid-food intake between SSB and diet-beverage drinkers overall or by body-weight categories.

Timing and Composition of Solid-Food Intake

To understand potential differences in the timing and composition of solid-food intake among diet and SSB drinkers, we also examined per capita solid-food calories consumed at meal occasions (meal or snack) as well as per capita calories from solid-food calories derived from sweet and salty snacks (not shown in the tables). With respect to meal occasions, SSB and diet-beverage drinkers consumed a comparable amount of calories per capita at meals and snacks (SSB drinkers: meals—1483 kcal/day; snacks—350 kcal/day; diet drinkers: meals—1485 kcal/day; snacks—371 kcal/day). Among adults who drank diet beverages, per capita consumption among obese individuals, compared with healthy-weight adults, was higher for meals and lower for snacks (diet drinkers, meals: healthy weight—1358 kcal/day; obese—1593 kcal/day; P < .05; diet drinkers, snacks: healthy weight—384 kcal/day; obese 366 kcal/day; P < .05). When we compared diet drinkers to SSB drinkers, per capita consumption at mealtime was higher among heavier adults and lower among healthy-weight adults (healthy weight: 1358 kcal/day vs 1448 kcal/day; P = .03; overweight: 1531 kcal/day vs 1441 kcal/day; P = .01; obese: 1593 kcal/day vs 1490 kcal/day; P = .02). Also, per capita snack consumption among obese adults was higher among diet drinkers than among SSB drinkers (366 kcal/day vs 300 kcal/day; P = .01)

Table 4 presents energy intake from sweet and salty snacks. Overall, patterns of snack consumption were mostly similar between SSB and diet-beverage drinkers with each group consuming roughly 20% of their total caloric intake from a combination of salty and sweet snacks (SSB drinkers: 12% sweet snacks or 238 kcal/day, 6% salty snacks or 118 kcal/day; diet drinkers: 11% sweet snacks or 238 kcal/day, 7% salty snacks or 128 kcal/day), regardless of body weight. We observed 2 notable differences. Obese adults who consumed SSBs ate significantly fewer calories from sweet snacks than healthy-weight SSB drinkers (214 kcal/day vs 243 kcal/day; P < .05). Second, obese adults who consumed diet beverages ate significantly more salty snacks than healthy-weight and overweight diet-beverage drinkers (obese: 131 kcal/day; overweight: 114 kcal/day; healthy weight: 123 kcal/day; P < .05). When we compared SSB drinkers to diet-beverage drinkers, obese adults who consumed diet drinks consumed significantly more calories from salty snacks than obese adults who consumed SSBs (131 kcal/day vs 107 kcal/day; P = .01).

TABLE 4—

Associations of Caloric Intake From Sweet and Salty Snacks Among US Adults (Aged 20 Years and Older) With Consuming Various Beverages: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2010

| Beverage Consumed | Total, Mean ±SE (%a) | Healthy Weight, Mean ±SE (%a) | Overweight, Mean ±SE (%a) | Obese, Mean ±SE (%a) |

| Sugar-sweetened | ||||

| Sweet, kcal | 238 ±10 (12) | 244 ±9 (12) | 222 ±7 (11) | 213* ±7 (11) |

| Salty, kcal | 118 ±6 (6) | 110 ±5 (6) | 103 ±5 (5) | 107 ±5 (6) |

| Diet | ||||

| Sweet, kcal | 238 ±19 (11) | 231 ±18 (12) | 238 ±16 (11) | 243 ±14 (11) |

| Salty, kcal | 129 ±11 (7) | 122 ±11 (7) | 115 ±8 (5) | 131*,** ±8 (6) |

| Alcohol | ||||

| Sweet, kcal | 182 ±14 (9) | 164 ±10 (9) | 189 ±10 (9) | 171 ±11 (9) |

| Salty, kcal | 105 ±7 (5) | 101 ±6 (5) | 91 ±6 (5) | 91 ±7 (5) |

| 100% juice | ||||

| Sweet, kcal | 235 ±14 (10) | 218 ±11 (9) | 228 ±12 (10) | 213 ±10 (9) |

| Salty, kcal | 105 ±7 (5) | 87 ±6 (4) | 100 ±6 (5) | 103* ±6 (5) |

| Milk | ||||

| Sweet, kcal | 238 ±11 (10) | 252 ±9 (11) | 216* ±7 (10) | 214* ±8 (9) |

| Salty, kcal | 98 ±6 (5) | 85 ±5 (4) | 87 ±4 (4) | 88 ±4 (4) |

Note. Healthy weight = body mass index (BMI) 18.5–24.99; overweight = BMI 25–29.99; obese = BMI ≥ 30. All values are mean per capita consumption (in kcal) from sweet or salty snacks for those people who consumed each beverage. Multivariate regression was used to adjust for gender, race/ethnicity, education, body-weight category, marital status, income, employment status, weekend or weekday, and other beverages consumed.

Percentage of contribution to daily solid caloric intake.

*Difference from healthy-weight group significant at P < .05; **difference between overweight and obese groups significant at P < .05.

DISCUSSION

The replacement of sugary beverages with noncaloric, diet alternatives is often recommended for individuals looking to lose or maintain weight.13 Our results indicate that heavier US adults are heeding this advice and using diet beverages as means of weight control. We found that about 1 in 5 overweight and obese adults consumes diet beverages, which is about twice the average among healthy-weight adults. Although overweight and obese adults who drink diet beverages eat a comparable amount of total calories as heavier adults who drink sugary beverages, they consume significantly more calories from solid food at both meals and snacks.

It was interesting that diet-beverage consumption appeared to be protective for adults at a healthy weight; they eat 73 fewer kilocalories from solid food on a typical day whereas overweight and obese adults who drink diet beverages consume 88 more kilocalories and 194 more kilocalories per day, respectively. Another notable finding is the similarity in snack consumption between SSB and diet-beverage drinkers, regardless of body weight. For both SSB and diet-beverage drinkers, roughly 20% of their total caloric intake is from a combination of salty and sweet snacks, which is consistent with previous research.15 This suggests that adults looking to lose or maintain their weight, who have already made the switch from sugary to diet beverages, may need to look carefully at other components of their solid-food diet, particularly sweet snacks, to potentially identify areas for modification. It also suggests that when adults replace SSBs with noncalorie beverage alternatives, they make few other changes to their diet.

On the one hand, it is encouraging that about 20% of overweight or obese adults drink diet beverages when one considers the strong evidence base linking sugary beverage consumption to increased risk of obesity in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies.16,17 It is also promising that diet drinkers do consume fewer calories from beverages compared with SSB drinkers. However, on the other hand, similar to earlier studies, we also found that individuals who drink diet beverages typically have higher BMI,5,6,18 consume more snack food,8 and—among heavier adults—do not eat fewer calories than those who consume SSBs.10

One reason why heavier persons who drink diet beverages may consume more calories from solid food is that consumption of artificial sweeteners, which are present in high doses in diet beverages, are associated with a greater activation of reward centers in the brain, thus altering the reward a person experiences from sweet tastes.19 In other words, among people who drink diet beverages, the brain’s sweet sensors may no longer provide a reliable gauge of energy consumption. Consumption of diet drinks may, therefore, result in increased food intake overall, perhaps attributable to the artificial sweetener causing disruptions with appetite control.5 Another possibility for higher solid-food consumption among heavier persons who drink diet beverages could be the excess caloric intake required to maintain the extra weight.20

Although it is the case that a switch from SSBs to diet drinks has been associated with weight loss attributable to differences in caloric content within the drinks themselves,5 our results, like those of other studies,5,9,10 suggest that the act of consuming diet drinks rather than SSBs does not significantly change food intake over the course of a typical day. This is consistent with a recent study by Stookey et al.21 that examined the net impact on daily energy intake from replacing sweetened caloric beverages with drinking water, diet, or other beverages. They found that the caloric deficit from replacing SSBs with water was not negated by compensatory increases in other food or beverages. In other words, replacing SSBs with diet drinks maintains two thirds of the caloric reduction compared with replacing SSBs with water. As a result, overweight and obese adults who drink diet beverages and who are looking to lose weight will likely need to reduce their caloric intake from solid foods to maintain or control their body weight.

Our finding that snacking patterns are generally comparable between diet and SSB drinkers is consistent with evidence suggesting that the sweet taste from beverages, whether delivered by sugar or artificial sweeteners, enhances human appetite.22 In a similar way, our finding of higher consumption of calories from sweet snacks (rather than salty snacks) is consistent with past research suggesting that sweetened beverages (made with natural or artificial sweeteners) encourage sugar craving and sugar dependence precisely because they are sweet.23 Our results, combined with those of previous studies, suggest that snacks—particularly sweet ones—are complements (rather than substitutes) to diet-beverage consumption.

The reduction or elimination of sugary beverages has been rightfully targeted in both clinical- and population-level obesity prevention efforts as a key “low-hanging fruit” for weight-loss or weight-maintenance efforts. Although reducing “empty-liquid calories” should remain an important goal for SSB drinkers, recommendations for adults to switch from SSBs to artificially sweetened diet alternatives may not help with long-term weight-loss efforts unless coupled with reductions in caloric intake from solid food as well, particularly sweet snacks. Among adults who drink diet beverages, awareness about caloric intake from solid foods may help prevent weight gain and promote weight loss, particularly among those who are overweight or obese.

More research is needed to better understand the impact of diet-beverage consumption on total caloric intake and, subsequently, on obesity risk. Epidemiological studies should carefully examine whether the composition of solid-food calories (e.g., fat, protein, sugar) differs between adults who drink sugary beverages and adults who drink noncaloric, artificially sweetened alternatives, particularly by body-weight categories. This area of inquiry may help identify components of the solid-food diet that can serve as easy targets for lifestyle modifications to promote weight loss as well as provide useful information for the development of targeted policies or nutrition programs aimed at reducing total energy intake among diet-beverage drinkers. A better understanding in this area may help inform current beverage recommendations, which suggest that consumption of beverages with no or few calories should take precedence over consumption of beverages with calories.13 In addition, physiological studies should further examine the body’s reaction to artificial sweeteners, the mechanisms by which this increases solid-food consumption, and how this physiological response may differ by body-weight category.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, our reliance on single 24-hour dietary recalls may introduce inaccuracy and bias to our analyses because of underreporting, unreliability, and conversion error. Previous research indicates that adults underreport their dietary consumption by approximately 25%.24,25 A single 24-hour dietary recall may not accurately represent usual dietary intake for an individual. Lack of reliability of the dietary recall, with respect to overall eating habits, will reduce the precision of our estimates but it will not bias our regression estimates where total energy intake is the dependent variable.26 There exists inaccuracy in converting reported beverage consumption to energy intake because the assumptions on serving size and food composition are defined by the food and nutrient database. Using this standard database assumes a “representative” nutritional content for a particular food or beverage. The inevitable variation in actual intake and reporting bias may introduce measurement errors, particularly for the estimation of total energy intake. However, this error is likely less significant for packaged, standard-sized beverages.

Second, the NHANES data are cross-sectional, which only allows us to address associations rather than causality. Third, our inclusion of low-calorie beverages in the SSB category may bias our results related to energy intake toward zero. However, only a small fraction of all the beverages in the SSBs category are low-calorie, so we do not expect this to have a significant impact on the results. Fourth, it is possible that our measures of energy intake differ among adults who consumed drinks across multiple beverage categories such as SSB and diet. However, because the percentage of our sample who consumed both SSBs and diet beverages was small (< 5%), we did not conduct additional analyses among this group.

Conclusions

Overweight and obese adults in the United States drink more diet beverages than healthy-weight adults, consume significantly more calories from solid food—at both meals and snacks—than overweight and obese adults who drink SSBs, and consume a comparable amount of total calories as overweight and obese adults who drink SSBs. With heavier adults increasingly switching to diet beverages, the focus on reducing SSBs may be insufficient for long-term weight-loss efforts. Heavier adults who drink diet beverages will need to reduce their consumption of solid-food calories to lose weight. More research is needed to identify and promote concrete behavioral targets aimed at reducing the consumption of solid food among heavier adults who drink diet beverages.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant 1K01HL096409).

Human Participant Protection

The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health institutional review board.

References

- 1.Bleich SN, Wang YC, Wang Y, Gortmaker SL. Increasing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among US adults: 1988–1994 to 1999–2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(1):372–381. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Changes in beverage intake between 1977 and 2001. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3):205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duffey KJ, Popkin BM. Shifts in patterns and consumption of beverages between 1965 and 2002. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(11):2739–2747. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fakhouri TH, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Consumption of diet drinks in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;(109):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dennis EA, Flack KD, Davy BM. Beverage consumption and adult weight management: a review. Eat Behav. 2009;10(4):237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appleton KM, Conner MT. Body weight, body-weight concerns and eating styles in habitual heavy users and non-users of artificially sweetened beverages. Appetite. 2001;37(3):225–230. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Castro JM. The effects of the spontaneous ingestion of particular foods or beverages on the meal pattern and overall nutrient intake of humans. Physiol Behav. 1993;53(6):1133–1144. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90370-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Binkley J, Golub A. Comparison of grocery purchase patterns of diet soda buyers to those of regular soda buyers. Appetite. 2007;49(3):561–571. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.03.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellisle F, Drewnowski A. Intense sweeteners, energy intake and the control of body weight. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61(6):691–700. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holt SH, Sandona N, Brand-Miller JC. The effects of sugar-free vs sugar-rich beverages on feelings of fullness and subsequent food intake. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2000;51(1):59–71. doi: 10.1080/096374800100912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhingra R, Sullivan L, Jacques PF et al. Soft drink consumption and risk of developing cardiometabolic risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged adults in the community. Circulation. 2007;116(5):480–488. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.689935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler SP, Williams K, Resendez RG, Hunt KJ, Hazuda HP, Stern MP. Fueling the obesity epidemic? Artificially sweetened beverage use and long-term weight gain. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(8):1894–1900. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Popkin BM, Armstrong LE, Bray GM, Caballero B, Frei B, Willett WC. A new proposed guidance system for beverage consumption in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(3):529–542. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.83.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic—Report of a WHO Consultation on Obesity. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piernas C, Popkin BM. Snacking increased among U.S. adults between 1977 and 2006. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):325–332. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(2):274–288. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulze MB, Manson JE, Ludwig DS et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type-2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA. 2004;292(8):927–934. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strachan SM, Brawley LR. Healthy-eater identity and self-efficacy predict healthy eating behavior: a prospective view. J Health Psychol. 2009;14(5):684–695. doi: 10.1177/1359105309104915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green E, Murphy C. Altered processing of sweet taste in the brain of diet soda drinkers. Physiol Behav. 2012;107(4):560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Food and Nutrition Technical Report Series. Rome, Italy: Food and Agricultural Organization; 2001. Food and Agricultural Organization, World Health Organization, United Nations University. Human energy requirements. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stookey JD, Constant F, Gardner CD, Popkin BM. Replacing sweetened caloric beverages with drinking water is associated with lower energy intake. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(12):3013–3022. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Q. Gain weight by “going diet?” Artificial sweeteners and the neurobiology of sugar cravings: Neuroscience 2010. Yale J Biol Med. 2010;83(2):101–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liem DG, de Graaf C. Sweet and sour preferences in young children and adults: role of repeated exposure. Physiol Behav. 2004;83(3):421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bingham SA, Gill C, Welch A et al. Comparison of dietary assessment methods in nutritional epidemiology: weighed records v. 24 h recalls, food-frequency questionnaires and estimated-diet records. Br J Nutr. 1994;72(4):619–643. doi: 10.1079/bjn19940064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Briefel RR, Sempos CT, McDowell MA, Chien S, Alaimo K. Dietary methods research in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: underreporting of energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(4 suppl):1203S–1209S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.4.1203S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox J. Applied Regression Analysis, Linear Models and Related Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]