Abstract

Objectives. We examined underestimation of nontraumatic work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) stemming from underreporting to workers’ compensation (WC).

Methods. In data from the 2007 to 2008 Québec Survey on Working and Employment Conditions and Occupational Health and Safety we estimated, among nonmanagement salaried employees (NMSEs) (1) the prevalence of WMSDs and resulting work absence, (2) the proportion with WMSD-associated work absence who filed a WC claim, and (3) among those who did not file a claim, the proportion who received no replacement income. We modeled factors associated with not filing with multivariate logistic regression.

Results. Eighteen percent of NMSEs reported a WMSD, among whom 22.3% were absent from work. More than 80% of those absent did not file a WC claim, and 31.4% had no replacement income. Factors associated with not filing were higher personal income, higher seniority, shorter work absence, and not being unionized.

Conclusions. The high level of WMSD underreporting highlights the limits of WC data for surveillance and prevention. Without WC benefits, injured workers may have reduced job protection and access to rehabilitation.

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are the main cause of disability in most industrialized countries and represent a considerable human and economic burden.1–4 Workers perceive a high proportion of their MSDs to be work related: nearly three quarters of workers in the province of Québec who had experienced musculoskeletal pain in 2007 to 2008 attributed it to work.5 The term work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) refers to nontraumatic inflammatory or degenerative disorders of the musculoskeletal structures of the neck, back, or upper or lower extremities that usually develop over time as a result of cumulative microtrauma, arising from biomechanical and other work exposures, that surpasses the adaptive and repair capacities of affected structures.6,7 Nontraumatic WMSDs are distinguished in etiology and prevention from MSDs caused by acute accidental traumatic injuries. Although one of the most common sources of data used to measure the incidence of work-related disorders is workers’ compensation (WC) data, several studies have suggested that such data underestimate the prevalence of occupational disorders, including MSDs.8–12 Few of these studies have specifically looked at nontraumatic WMSDs.

We estimated, among nonmanagement salaried employees (NMSEs), (1) the 1-year prevalence of nontraumatic WMSDs and resulting work absence, (2) the proportion with WMSD-associated work absence who filed a WC claim, and (3) among those who did not file a claim, the proportion who lacked replacement income during their work absence.

METHODS

We used data collected from November 2007 to February 2008 for the Québec Survey on Working and Employment Conditions and Occupational Health and Safety. It was a household-based landline telephone survey of a weighted random sample of the Québec working population aged 15 years and older and holding a paid position for at least 8 weeks prior to the survey for at least 15 hours per week.13 The Québec Institute of Statistics completed telephone interviews with 5071 workers (response rate = 62%). To allow inferences regarding the targeted population, the institute weighted data to account for the sampling design by administrative region and for nonresponse.13,14

We limited our analysis to NMSEs (n = 3855 respondents). We excluded self-employed and managerial salaried workers, who were not covered by WC or were less likely to make a claim.

Variables

We assessed the musculoskeletal outcome measure through questions adapted for the telephone interview from the 1998 Québec Social and Health Survey,4 which were derived from the standardized Nordic questionnaire.15–17 Interviewers asked whether, in the previous 12 months, respondents had experienced significant muscle, tendon, bone, or joint pain that interfered with their usual activities, in the neck, back, and upper and lower extremities. For each body region, respondents rated the frequency of pain and perception of whether it was related to their current job. We excluded respondents who reported pain of acute traumatic origin. Our case definition of WMSD was significant nontraumatic musculoskeletal pain that interfered with activities; experienced occasionally, frequently, or all the time; in at least 1 body region in the previous 12 months; and perceived as entirely related to work.5

Interviewers asked respondents who reported a WMSD whether in the previous 12 months they had been absent from work because of this pain, and if so, how many work days they missed and their source of income during the work absence. Respondents with a WMSD-associated work absence of at least 1 day were further asked whether they had filed a WC claim, and if not, the reason(s) for not filing. We grouped these reasons into 5 categories. A small proportion of respondents cited more than 1 reason, resulting in the sum of proportions exceeding 100%. Québec workers are eligible for WC benefits from the start of their work absence; hence we considered WMSD-associated work absences of at least 1 day for our analyses. Income replacement benefits for the first 10 working days (i.e., first 2 weeks) of work absence are advanced to the worker by the employer, who is subsequently reimbursed by the WC board.18 Workers’ awareness of this policy may influence their decisions about filing WC claims; therefore, we estimated the proportion who filed a WC claim for nontraumatic WMSD–associated work absences of at least 1 day, as well as the proportions who filed WC claims for work absences of 2 weeks or less and more than 2 weeks.

We assessed the following personal factors: gender, age, education, personal income, and perceived general health status. We also measured the following working conditions: occupational category (4-digit 2006 Canadian National Occupational Classification codes,19 grouped into 3 categories: manual, nonmanual, mixed occupations),20,21 company size, union membership, holding more than 1 job, seniority at the current main job, total number of hours worked per week, permanent versus temporary job status, perceived job security, episode of unemployment in the previous 2 years, workplace support from superiors, support from coworkers, and hostility at work from superiors or coworkers.14

Analysis

We estimated the 12-month period prevalence of WMSDs and of work absence for at least 1 day among employees with a WMSD, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For NMSEs with a WMSD-associated work absence, we estimated the proportion who filed a WC claim and compared the sociodemographic and occupational characteristics of those who filed a WC claim with those who did not, with the Rao–Scott χ2 test, which accounts for sampling weights to compare proportions,22 or the appropriate t test for weighted samples to compare means. We also estimated the proportion of NMSEs who reported a WMSD-associated work absence but did not file a WC claim and who received no replacement income.

We estimated proportions for the combined study population and separately for each gender because gender has been associated with differences in WC claim behavior23 and with factors affecting time to return to work.24 In addition, men and women have different occupational exposures even within the same occupational category25–27 that may influence prevalence of WMSDs and associated work absence. We tested significant gender differences with the Rao–Scott χ2 test or t test for weighted samples, as appropriate.

We used multivariate logistic regression to identify sociodemographic and occupational characteristics independently associated with not filing a WC claim among employees with WMSD-associated work absence of at least 1 day among the combined sample of men and women, because the sample was too small to allow gender-stratified analyses. We first analyzed the relationship between each sociodemographic or occupational variable and not filing a WC claim in a series of reduced logistic regression models adjusted for the a priori selected potential effect modifiers or confounders age, gender, and weekly hours worked. Next, we incorporated all variables with at least a marginally significant effect in the corresponding reduced model (P ≤ .25) in the initial multivariate logistic model, in addition to age, gender, and weekly hours worked. Finally, we used a backward stepwise elimination procedure, with P > .1 for the 2-tailed Wald test as the criterion for variable elimination, to build the final parsimonious multivariate logistic regression models. Accordingly, the final model incorporated only variables that had statistically significant independent associations with the odds of not filing a WC claim; however, we included age, gender, and weekly hours worked in the model regardless of their statistical significance.

We summarized the results of the final model by adjusted odds ratios of not filing a WC claim, with model-based 95% CIs. We conducted all analyses with SAS software for complex survey data, version 9.2.28

RESULTS

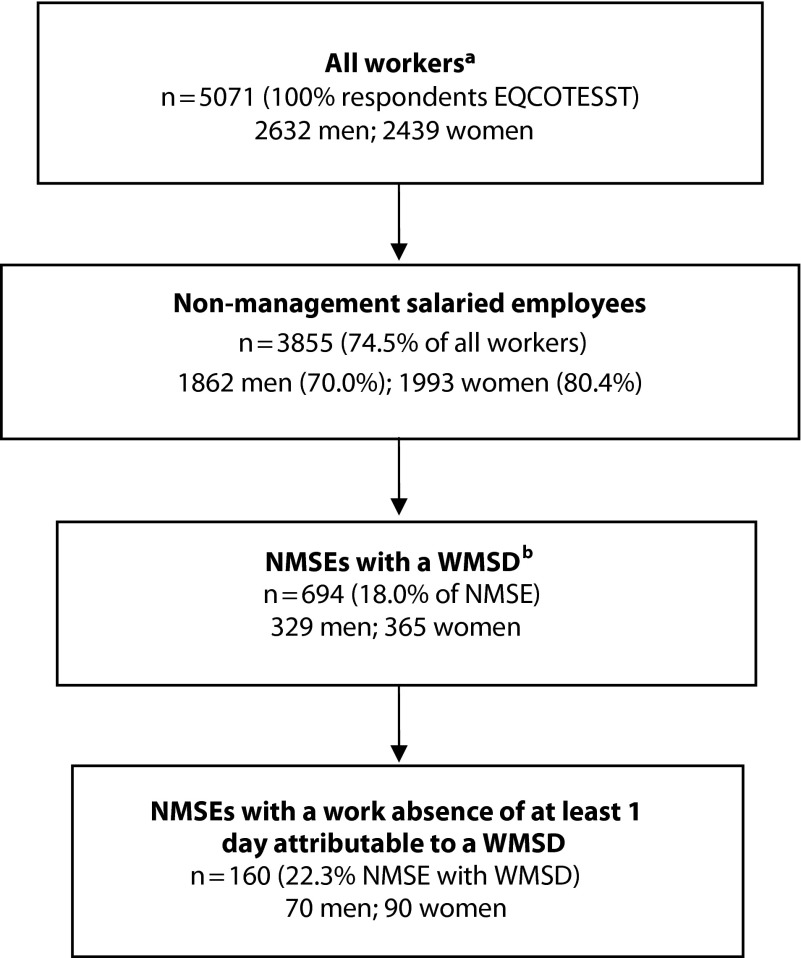

Figure 1 describes the study population and its subgroups. Among nonmanagement salaried employees, 18.0% experienced a WMSD, among whom 22.3% were absent from work for at least 1 day (Figure 1), with a mean absence of 25.1 (95% CI = 15.0, 35.1) working days and a median of 6.0 working days (Table A, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org). Although the prevalence and mean duration of work absence did not differ by gender, women had a much shorter median duration of absence (5.0 working days vs 10.0 working days for men), but a somewhat higher proportion of women (12.2% vs 8.1%) had long-duration absences (> 60 working days; Table A).

FIGURE 1—

Study population by gender: Survey on Working and Employment Conditions and Occupational Health and Safety, Québec, 2007–2008.

Note. EQCOTESST = enquête québécoise sur des conditions de travail, d’emploi, de santé et de sécurité du travail [Québec Survey on Working and Employment Conditions and Occupational Health and Safety]; NMSE = nonmanagement salaried employee; WMSD = work-related musculoskeletal disorders. All prevalences are weighted sample estimates.

aAged ≥ 15 years, holding a paid position as an employee or self-employed worker for at least 8 weeks at ≥ 15 hours/week.

bWMSD defined as significant non-traumatic musculoskeletal pain interfering with activities, experienced occasionally, frequently or all the time, in ≥ 1 body region, in the previous 12 months and perceived as entirely related to work.

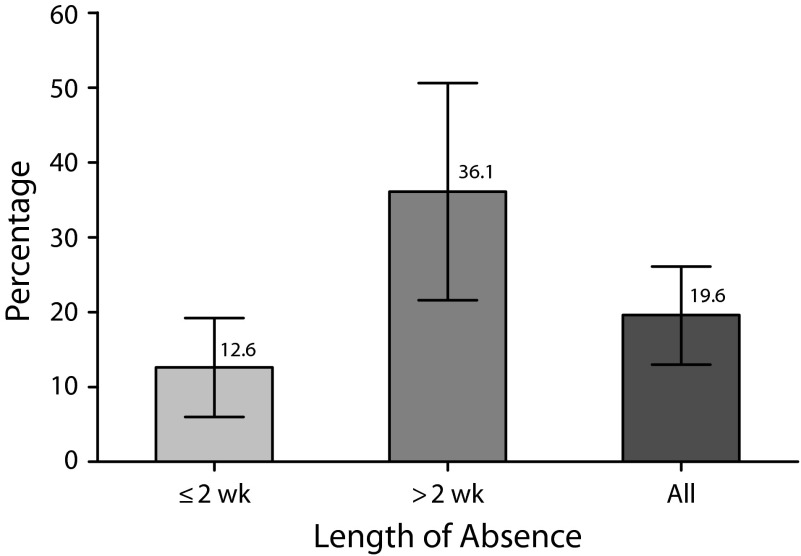

Figure 2 shows that fewer than 20% of NMSEs with a work absence of at least 1 day caused by a WMSD perceived as entirely related to work filed a WC claim. When work absence extended beyond 2 weeks, a little more than a third (36.1%) of those absent for a WMSD filed a claim.

FIGURE 2—

Proportion of nonmanagement salaried employees who filed a workers’ compensation claim among those with a work absence from a WMSD: Survey on Working and Employment Conditions and Occupational Health and Safety, Québec, 2007–2008.

Note. WMSD = work-related musculoskeletal disorders (defined as significant nontraumatic musculoskeletal pain interfering with activities, experienced occasionally, frequently, or all the time, in ≥ 1 body region, in the previous 12 months and perceived as entirely related to work). Two weeks corresponds to 10 working days. Whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

By far the most common reason for not filing a claim for a WMSD-associated work absence was employees’ perception that they or their specific musculoskeletal problem was not covered by WC, offered by more than half of workers (53.5%; 95% CI = 43.6, 63.4). The belief that the problem was not serious enough to merit compensation was the second most frequent reason, cited by 19.7% (95% CI = 11.7, 27.7). Some workers cited lack of information or problems with the claims process (15.4%; 95% CI = 8.2%, 22.6%), and 13.1% (95% CI = 6.7%, 19.5%) reported that their salary during the work absence was paid by the employer or by another organization. A small proportion of workers (5.5%; 95% CI = 2.0%, 9.1%) believed that filing a claim was prohibited or would be perceived negatively by the employer or coworkers (data not shown).

Table 1 presents employee sociodemographic and job characteristics for all NMSEs and compares NMSEs with a work absence for a WMSD who did and did not file a WC claim. We detected no statistically significant differences between those who filed and those who did not file a WC claim, probably because of the small numbers who filed a claim.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Nonmanagement Salaried Employees With a Work Absence for a Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorder by Filing Versus Not Filing a Workers' Compensation Claim: Survey on Working and Employment Conditions and Occupational Health and Safety, Québec, 2007–2008

| NMSEs |

|||

| Variable | Total (n = 3855), Weighted % (95% CI) or Mean ±SD (Median) | Had WMSD Absence and Filed WC Claim (n = 33), Weighted % (95% CI) or Mean ±SD (Median) | Had WMSD Absence and Did Not File WC Claim (n = 127), Weighted % (95% CI) or Mean ±SD (Median) |

| Sociodemographic and health characteristics | |||

| Gender | |||

| Women | 50.4 (48.5, 52.2) | 49.1 (30.7, 67.5) | 58.3 (48.3, 68.2) |

| Men | 49.6 (47.8, 51.5) | 50.9 (32.5, 69.3) | 41.7 (31.8, 51.7) |

| Age | 39.4 ±15.3 (40.0) | 43.7 ±9.7 (45.0) | 40.8 ±11.9 (42.0) |

| Personal income, Can$ | |||

| < 20 000 | 19.8 (18.1, 21.5) | 20.6 (5.3, 35.9) | 11.7 (4.2, 19.2) |

| 20 000–59 999 | 63.9 (62.1, 65.8) | 75.7 (59.4, 92.0) | 76.6 (67.6, 85.6) |

| ≥ 60 000 | 16.3 (15.0, 17.6) | 3.7 (0.0, 11.0) | 11.7 (5.9, 17.6) |

| Education | |||

| ≤ elementary school | 13.2 (12.0, 14.5) | 26.9 (10.0, 43.7) | 12.4 (5.9, 18.9) |

| High school diploma | 33.5 (31.7, 35.2) | 43.7 (25.8, 61.5) | 42.3 (32.2, 52.3) |

| College diploma (CEGEP or equivalent) | 26.0 (24.4, 27.7) | 21.6 (7.4, 35.9) | 29.1 (19.6, 38.6) |

| University diploma | 27.2 (25.7, 28.8) | 7.8 (0.0, 16.8) | 16.2 (9.3, 23.2) |

| Perceived general health status | |||

| Poor/fair | 7.1 (6.2, 8.0) | 18.4 (3.6, 33.2) | 15.0 (8.6, 21.4) |

| Good/very good/excellent | 92.9 (92.0, 93.8) | 81.6 (66.8, 96.4) | 85.0 (78.6, 91.4) |

| Occupational characteristics | |||

| Seniority in current job, y | |||

| ≤ 2 | 33.8 (32.0, 35.6) | 17.1 (3.0, 31.2) | 29.0 (19.0, 39.0) |

| 2.1–5 | 19.5 (18.0, 21.0) | 31.2 (14.4, 48.0) | 13.1 (5.6, 20.6) |

| 5.1–10 | 18.2 (16.9, 19.6) | 29.4 (13.3, 45.5) | 26.3 (17.6, 35.1) |

| > 10 | 28.4 (26.9, 30.0) | 22.3 (5.6, 38.8) | 31.6 (22.4, 40.7) |

| Average | 8.5 ±9.7 (5.0) | 8.1 ±7.8 (6.0) | 9.8 ±9.3 (7.0) |

| Work time, h/wk | |||

| < 30 | 14.7 (13.3, 16.1) | 10.3 (0.0, 22.2) | 16.5 (8.2, 24.8) |

| ≥ 30 | 85.3 (83.9, 86.7) | 89.7 (77.8, 100.0) | 83.5 (75.2, 91.8) |

| Average | 37.1 ±10.9 (39.0) | 36.1 ±7.3 (40.0) | 36.8 ±10.0 (38.0) |

| Occupational category | |||

| Manual | 30.9 (29.2, 32.6) | 62.1 (44.2, 80.0) | 42.3 (32.5, 52.0) |

| Mixed | 25.2 (23.6, 26.9) | 19.3 (3.3, 35.3) | 28.3 (18.7, 37.9) |

| Nonmanual | 43.8 (42.0, 45.6) | 18.6 (5.5, 31.7) | 29.5 (20.3, 38.6) |

| Temporary job (vs permanent) | 12.9 (11.5, 14.2) | 7.3 (0.0, 15.9) | 10.8 (4.2, 17.5) |

| Perceived low job security | 35.4 (33.6, 37.1) | 44.6 (26.5, 62.6) | 50.2 (39.8, 60.7) |

| Episode of unemployment in previous 2 y | 18.2 (16.8, 19.7) | 17.7 (3.4, 32.0) | 22.7 (14.1, 31.3) |

| Company size, no. employees | |||

| ≤ 50 | 38.1 (36.2, 39.9) | 35.8 (17.4, 54.2) | 26.8 (17.2, 36.5) |

| 51–199 | 17.0 (15.6, 18.4) | 18.0 (3.89, 32.2) | 21.7 (13.0, 30.4) |

| 200–499 | 11.8 (10.6, 13.0) | 10.5 (0.0, 20.9) | 9.7 (4.2, 15.2) |

| ≥ 500 | 33.1 (31.4, 34.9) | 35.7 (17.3, 54.1) | 41.8 (31.2, 52.5) |

| Union membership | 44.4 (42.6, 46.3) | 71.4 (54.7, 88.1) | 52.4 (41.9, 62.9) |

| Holding ≥ 1 job | 7.6 (6.5, 8.6) | 15.4 (0.0, 31.1) | 7.1 (1.7, 12.5) |

| Support of coworkers | |||

| Low | 16.7 (15.3, 18.0) | 38.5 (21.8, 55.3) | 31.3 (22.1, 40.4) |

| High | 83.3 (82.0, 84.7) | 61.5 (44.7, 78.2) | 68.7 (59.6, 77.9) |

| Support of superior | |||

| Low | 26.4 (24.8, 28.0) | 49.8 (31.5, 68.1) | 45.5 (35.3, 55.6) |

| High | 73.6 (72.0, 75.2) | 50.2 (31.9, 68.5) | 54.5 (44.4, 64.7) |

| Hostility at work from coworkers or superiors | |||

| High | 15.6 (14.3, 17.0) | 26.1 (10.9, 41.3) | 26.2 (17.1, 35.3) |

| Low | 84.4 (83.0, 85.7) | 73.9 (58.7, 89.1) | 73.8 (64.7, 82.9) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; CEGEP = Collège d'enseignement général et professionnel [general and vocational college]; NMSE = nonmanagement salaried employee; WC = workers’ compensation; WMSD = work-related musculoskeletal disorder (defined as significant nontraumatic musculoskeletal pain interfering with activities; experienced occasionally, frequently, or all the time; in ≥ 1 body region; in the previous 12 months; and perceived as entirely related to work).

Table 2 presents the final logistic regression model of factors independently and significantly associated with a greater likelihood of not filing a WC claim. These were higher personal income, not being a union member, shorter duration of work absence, working less than 30 hours per week, and high seniority (> 10 years). Low seniority (≤ 2 years) and female gender showed a strong but not statistically significant association with not filing a WC claim.

TABLE 2—

Multivariate Logistic Regression Model of Factors Associated With Not Filing a Workers’ Compensation Claim Among Nonmanagement Salaried Employees Absent From Work for a Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorder: Survey on Working and Employment Conditions and Occupational Health and Safety, Québec, Canada, 2007–2008

| Variable | AOR (95% CI) | P |

| Personal income, Can$ | ||

| ≥ 60 000 | 24.29 (2.72, 216.80) | .004 |

| 20 000–59 999 | 6.52 (1.41, 30.19) | .017 |

| < 20 000 (Ref) | 1.00 | |

| Duration of work absence, wka | ||

| ≤ 2 | 4.07 (1.48, 11.16) | .007 |

| > 2 (Ref) | 1.00 | |

| Union membership | ||

| No | 4.13 (1.45, 11.76) | .008 |

| Yes (Ref) | 1.00 | |

| Seniority in current job, y | ||

| > 10 | 4.20 (1.00, 17.70) | .051 |

| 5.1–10 | 1.88 (0.51, 6.98) | .347 |

| 2.1–5 (Ref) | 1.00 | |

| ≤ 2 | 3.61 (0.65, 20.06) | .142 |

| Work time, h/wk | ||

| < 30 | 5.24 (1.37, 20.05) | .016 |

| ≥ 30 (Ref) | 1.00 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 2.04 (0.66, 6.30) | .218 |

| Male (Ref) | 1.00 | |

| Age (continuous variable), each additional y | 0.97 (0.92, 1.02) | .262 |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Work-related musculoskeletal disorder was defined as significant nontraumatic musculoskeletal pain interfering with activities; experienced occasionally, frequently, or all the time; in ≥ 1 body region; in the previous 12 months; and perceived as entirely related to work. Other variables tested in this model but eventually excluded were education level, personal income, occupational category, temporary (vs permanent) job, perceived low job security, having experienced an episode of unemployment in the previous 2 years, holding > 1 job, company size, support of coworkers, support of superiors, hostility from coworkers or superiors, and perceived general health status. The sample size was n = 150.

Two weeks represents 10 working days.

Among NMSEs who did not file a WC claim for a WMSD work absence, almost one third (31.4%; 95% CI = 22.1%, 40.8%) lacked replacement income during their work absence. Gender differences were not significant (men, 27.2%; 95% CI = 14.1%, 40.3%; women, 34.5%; 95% CI = 21.5%, 47.4%). Among those who received replacement income, the primary source was the employer, followed by sick days or vacation benefits, and a very small proportion from WC or government employment insurance illness benefits (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our results highlight the important contribution of the workplace to the burden of MSDs in Québec. Our key finding is that fewer than 20% of Québec NMSEs with a work absence for nontraumatic musculoskeletal symptoms perceived as entirely work related filed a WC claim, and only a third filed claims even when absences extended beyond 2 weeks. Almost one third of those who did not file a claim had no replacement income during their work absence.

The underreporting of nontraumatic WMSDs to WC among Québec workers is in line with other North American findings, showing that the proportion of workers who filed a WC claim among those with physician-diagnosed or perceived WMSDs was between 16% and 32%.8,29–31 A lesser degree of underreporting has been demonstrated for occupational traumatic injuries. The proportion of workers who filed a WC claim for traumatic work injuries was 67% in the Québec Survey on Working and Employment Conditions and Occupational Health and Safety32 and approximately 60% in other studies,10,33 but was higher for severe injuries requiring hospitalization34 and lower among US Hispanic construction workers than among White colleagues.33 Similarly, the proportion filing a WC claim for any work-related injury or illness was approximately 50%.9,35

Some of the reasons given for not filing a WC claim by Québec respondents were similar to those reported in studies of workers in other jurisdictions29,31,36,37 and in line with barriers to reporting described by Azaroff et al.12 These findings suggest that workers need better education on their right to compensation and on the conditions covered by WC. Employers should also be responsible for informing workers that they need not fear reprisals for making claims. Employers’ appeals of WC claims are not a rare occurrence, and workers who are aware of this phenomenon may be more reluctant to file a claim.38,39 Some employers may attempt to suppress claims when their firm’s premiums are tied to WC claims rates.40

In Québec, as in some other parts of Canada, physician reports to WC are often the first step in initiating a WC claim, and physicians are uniquely positioned to help injured workers file claims and manage work-related disorders. Yet doctors are often uncomfortable with WC systems and may not discuss with the worker the possibility of submitting a claim.12,41 Hence, doctors may need to become better acquainted with WC procedures and realize the importance of compensation for patients who wish to file a claim.

Factors associated with not making a WC claim included higher personal income, part-time work, not being a union member, and a shorter work absence. Higher income and a shorter absence have been cited as explanatory factors of WC underreporting elsewhere.31 In our sample, workers absent less than 2 weeks may not have been motivated to file a WC claim if they believed that the employer was the sole provider of their replacement benefits, rather than the WC regime. Indeed, workers cited salary replacement by the employer among the reasons for not filing a WC claim. Other factors cited in the literature associated with lower WC reporting rates include satisfaction with coworkers, medical treatment through a family practitioner or company physician rather than a musculoskeletal specialist,31 evening and night shift work, Hispanic ethnicity in the United States, multiple previous injuries on the job, working in a place lacking proper protective equipment,36 small establishment size,11,33,42 and low perceived health status31 (we did not find the latter 2 to be significant factors for our sample). In agreement with our findings, Morse et al. found that workers at unionized facilities were 5.7 times as likely to file a WC claim for an upper-extremity WMSD as workers at nonunionized facilities and suggested that this could be related to union members having better information and awareness about WC claims procedures or protection from reprisal for filing a WC claim.43 Finally, we observed that both high (> 10 years) and very low (≤ 2 years) seniority were associated with not filing a claim (although the strong latter association was not statistically significant, probably because of a lack of power). High seniority has similarly been associated with not filing among US nurses,36 but it was also associated with filing a claim among unionized autoworkers.31

These results suggest that WC data do not represent the full burden of illness and cannot be relied on to provide the true prevalence of occupational MSDs and, thus, to help estimate the full range of needs for occupational health and safety measures44 or the true costs of disability associated with work injury. Underreporting decreases employers’ incentive to implement appropriate preventive or return-to-work strategies that facilitate gradual reintegration of injured workers to the workplace.41 Access to modified duties and addressing the work context during rehabilitation of workers with MSDs has been shown to prevent long-term work disability and reduce the duration of work absence45–47 and to be cost-effective for the WC system. Because few Canadian provincial public health insurance plans cover nonphysician rehabilitation services, and the large majority of workers are not covered by private plans, the only access to these services is often through WC.

The high level of underreporting of WMSD-associated work absences suggests that relatively few workers may have access to needed rehabilitation services. It therefore may be cost-effective for public health insurance plans to better fund such services.48 This is an area of health services that should be better studied. Finally, the discrepancies we documented between prevalence of WMSD-related work absence and claims filed warrant further investigation to ascertain, among other things, the transfer of costs to the public health system, other government social assistance and unemployment programs, private insurers, and individual workers.

Limitations and Strengths

The attribution of MSD symptoms to work depended on workers’ perception, although several studies show the validity of this perception.49 However, if workers with a WMSD fail to perceive that their problem is work related, as some evidence suggests,12 we may have underestimated the extent of underreporting among Québec workers. Conversely, not all nontraumatic WMSD–associated work absences reported by our respondents were necessarily compensable.

The telephone survey may have led to noncoverage bias against households with no telephone service (∼1% of Québec households in 2007) or no landline telephone service (∼6% in 2007).13 However, the proportion of cell phone–only households was much lower in Québec than in the United States, where it was about 15% in 2007.50

Another limitation was the small number of workers among the almost 4000 NMSEs who had a WMSD-associated work absence perceived as entirely related to work. This limited the sample size available for regression analysis (n = 160) and did not allow for gender-stratified analyses of the factors associated with not filing a WC claim.

The survey response rate of 62% was less than ideal, although relatively high for telephone surveys. To address this, the Québec Institute of Statistics, which carried out the survey, made a significant effort to identify selection biases resulting in over- or underrepresentation by age, gender, education, or employment characteristics and, if needed, to apply data adjustment to ensure that the study population would be representative of the Québec target population. We compared certain estimates of the survey, in particular education and income level of Québec workers aged 15 years and older, with those of the 2006 Canadian Labor Force Survey and the Canadian Community Health Survey for Québec workers and found them to be nearly identical.13 In one of several data adjustment steps, we compared sample estimates with those of the Canadian Labor Force Survey Québec subsample and adjusted our estimates for age, gender, unionization, and industrial sector.

The cross-sectional nature of the survey precluded us from asserting causality in the relationships examined. However, some of the factors that were significantly associated with not filing a WC claim, such as personal income and unionization, existed before the injury and the decision about filing a claim.

We analyzed new province-level data. Few studies in the North American scientific literature focus on nontraumatic WMSDs rather than on acute traumatic accidents or all occupational injuries and illnesses together. Ours was also the only study, to our knowledge, to focus on the subgroup of workers most likely to file a WC claim, NMSEs, excluding the self-employed and managerial employees.

Conclusions

Our findings illustrate the great extent of underreporting to WC of nontraumatic WMSDs among Québec workers, adding to the body of literature on underreporting of work-related injuries and illnesses in America. Underreporting has negative consequences and costs for workers, employers, and society. Education of workers on their rights and of employers and physicians on WC procedures and practices may serve the interests of all stakeholders. Nontraumatic WMSDs disable a substantial proportion of the working population and lead to work absence and significant productivity losses. Identification and prevention of these disorders and improved access to rehabilitation services should be viewed as policy priorities.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

We thank Michal Abrahamowicz for his statistical advice and comments on the article and Amélie Funes for her contribution to preliminary analyses of this work.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the University of Montreal Hospital Centre.

References

- 1.Côté P, van der Velde G, Cassidy JD et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in workers: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008;33(4 suppl):S60–S74. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181643ee4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scientific Group on the Burden of Musculoskeletal Conditions at the Start of the New Millennium. The Burden of Musculoskeletal Conditions at the Start of the New Millennium. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. World technical report series 919. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(9):646–656. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arcand R, Labrèche F, Stock S, Messing K, Tissot F. Travail et santé [Work and health] In: Daveluy C, Pica L, Audet N, Courtemanche R, Lapointe F, editors. Enquête sociale et de santé 1998 [1998 Québec Health and Social Survey]. 2nd ed. Québec, Montreal: Institut de la Statistique du Québec; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stock S, Funes A, Delisle A, St-Vincent M, Turcot A, Messing K. Troubles musculo-squelettiques [Musculoskeletal discorders] In: Vézina M, Cloutier E, Stock S, editors. Enquête québécoise sur des conditions de travail, d’emploi, de santé et de sécurité du travail (EQCOTESST) [Québec Survey on Working and Employment Conditions and Occupational Health and Safety]. Québec, Montreal: Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et sécurité du travail, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Institut de la statistique du Québec; 2011:445–530. Document R-691. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Workplace: Low Back and Upper Extremities. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dennerlein JT. Ergonomics/musculoskeletal issues. In: Heggenhougen HK, Quah SR, editors. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. 1st ed. 6 vols. New York, NY: Elsevier Inc; 2008. pp. 443–452. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luckhaupt SE, Calvert GM. Work-relatedness of selected chronic medical conditions and workers’ compensation utilization: National Health Interview Survey occupational health supplement data. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53(12):1252–1263. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan ZJ, Bonauto DK, Foley MP, Silverstein BA. Underreporting of work-related injury or illness to workers’ compensation: individual and industry factors. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48(9):914–922. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000226253.54138.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shannon HS, Lowe GS. How many injured workers do not file claims for workers’ compensation benefits? Am J Ind Med. 2002;42(6):467–473. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biddle J, Roberts K, Rosenman KD, Welch EM. What percentage of workers with work-related illnesses receive workers’ compensation benefits? J Occup Environ Med. 1998;40(4):325–331. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199804000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azaroff LS, Levenstein C, Wegman DH. Occupational injury and illness surveillance: conceptual filters explain underreporting. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(9):1421–1429. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fortin E, Lapointe F, Traoré I, Des Groseilliers L, Audet N, St-Amand M-E. Méthodes et profil de la population [Methods and description of study population] In: Vézina M, Cloutier E, Stock S, editors. Enquête québécoise sur des conditions de travail, d’emploi, de santé et de sécurité du travail (EQCOTESST) [Québec Survey on Working and Employment Conditions and Occupational Health and Safety]. Québec, Montreal: Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et sécurité du travail, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Institut de la statistique du Québec; 2011:5–58. Document R-691. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vézina M, Cloutier E, Stock S et al. Enquête québécoise sur des conditions de travail, d’emploi, de santé et de sécurité du travail (EQCOTESST) [Québec Survey on Working and Employment Conditions and Occupational Health and Safety]. Québec, Montreal: Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et sécurité du travail, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Institut de la statistique du Québec; 2011. Document R-691. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A et al. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl Ergon. 1987;18(3):233–237. doi: 10.1016/0003-6870(87)90010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersson K, Karlehagen S, Jonsson B. The importance of variations in questionnaire administration. Appl Ergon. 1987;18(3):229–232. doi: 10.1016/0003-6870(87)90009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohlsson K, Attewell RG, Johnsson B, Ahlm A, Skerfving S. An assessment of neck and upper extremity disorders by questionnaire and clinical examination. Ergonomics. 1994;37(5):891–897. doi: 10.1080/00140139408963698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Québec P. Compilation of Québec Laws and Regulations. Act respecting industrial accidents and occupational diseases (chapter A-3.001). Government of Québec. Available at: http://www2.publicationsduquebec.gouv.qc.ca. Accessed February 25, 2013.

- 19.Statistics Canada. National occupational classification statistics. 2006. Available at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/subjects-sujets/standard-norme/soc-cnp/2006/noc2006-cnp2006-menu-eng.htm. Accessed March 12, 2012.

- 20.Hébert F, Duguay P, Massicotte P. Les indicateurs de lésions indemnisées en santé et en sécurité du travail au Québec: analyse par secteur d’activité économique en 1995–1997 [Indicators of occupational health and safety compensated injuries and disorders: analysis by industrial sector in 1995–1997]. Montréal, Québec: Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et sécurité du travail; 2003. Document R-333.

- 21.Duguay P, Massicotte P, Prud’homme P. Lésions professionnelles indemnisées au Québec en 2000-2002: I—Profil statistique par activité économique [Occupational disorders compensated in Quebec in 2000–2002: I—statistical profile by industrial sector]. Montréal, Québec: Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et sécurité du travail; 2008. Document R-547.

- 22.Rao JNK, Scott AJ. The analysis of categorical data from complex sample surveys: chi-squared tests for goodness of fit and independence in two-way tables. J Am Stat Assoc. 1981;76(374):221–230. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du J, Leigh JP. Incidence of workers compensation indemnity claims across socio-demographic and job characteristics. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54(10):758–770. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lederer V, Rivard M, Mechakra-Tahiri SD. Gender differences in personal and work-related determinants of return-to-work following long-term disability: a 5-year cohort study. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22(4):522–531. doi: 10.1007/s10926-012-9366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Messing K, Stock SR, Tissot F. Should studies of risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders be stratified by gender? Lessons from the 1998 Québec Health and Social Survey. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009;35(2):96–112. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strazdins L, Bammer G. Women, work and musculoskeletal health. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(6):997–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karlqvist L, Tornqvist EW, Hagberg M, Hagman M, Toomingas A. Self-reported working conditions of VDU operators and associations with musculoskeletal symptoms: a cross-sectional study focussing on gender differences. Int J Ind Ergon. 2002;30(4–5):277–294. [Google Scholar]

- 28. SAS, Version 9.2 [computer program]. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

- 29.Scherzer T, Rugulies R, Krause N. Work-related pain and injury and barriers to workers’ compensation among Las Vegas hotel room cleaners. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(3):483–488. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.033266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morse T, Dillon C, Warren N, Hall C, Hovey D. Capture-recapture estimation of unreported work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Connecticut. Am J Ind Med. 2001;39(6):636–642. doi: 10.1002/ajim.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenman KD, Gardiner JC, Wang J et al. Why most workers with occupational repetitive trauma do not file for workers’ compensation. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42(1):25–34. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200001000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cloutier E, Duguay P, Vézina S, Prud’homme P. Accidents du travail [Workplace accidents] In: Vézina M, Cloutier E, Stock S, editors. Enquête québécoise sur des conditions de travail, d’emploi, de santé et de sécurité du travail (EQCOTESST) [Québec Survey on Working and Employment Conditions and Occupational Health and Safety]. Québec, Montreal: Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et sécurité du travail, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, Institut de la statistique du Québec; 2011:531–590. Document R-691. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong XS, Fujimoto A, Ringen K et al. Injury underreporting among small establishments in the construction industry. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54(5):339–349. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alamgir H, Koehoorn M, Ostry A, Tompa E, Demers PA. How many work-related injuries requiring hospitalization in British Columbia are claimed for workers’ compensation? Am J Ind Med. 2006;49(6):443–451. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith PM, Kosny AA, Mustard CA. Differences in access to wage replacement benefits for absences due to work-related injury or illness in Canada. Am J Ind Med. 2009;52(4):341–349. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siddharthan K, Hodgson M, Rosenberg D, Haiduven D, Nelson A. Under-reporting of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in the Veterans Administration. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv. 2006;19(6–7):463–476. doi: 10.1108/09526860610686971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipscomb HJ, Dement JM, Silverstein B, Kucera KL, Cameron W. Health care utilization for musculoskeletal back disorders, Washington State union carpenters, 1989–2003. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(5):604–611. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31819c561c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lippel K. Preserving workers’ dignity in workers’ compensation systems: an international perspective. Am J Ind Med. 2012;55(6):519–536. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lippel K. Le droit québécois et les troubles musculo-squelettiques: règles relatives à l’indemnisation et à la prévention [Quebec law and musculoskeletal disorders: rules related to compensation and prevention] Perspectives interdisciplinaires sur le travail et la santé. 2009;11(2):37. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tompa E, Trevithick S, McLeod C. Systematic review of the prevention incentives of insurance and regulatory mechanisms for occupational health and safety. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2007;33(2):85–95. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson A. The consequences of underreporting workers’ compensation claims. Can Med Assoc J. 2007;176(3):343–344. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morse T, Dillon C, Weber J, Warren N, Bruneau H, Fu R. Prevalence and reporting of occupational illness by company size: population trends and regulatory implications. Am J Ind Med. 2004;45(4):361–370. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morse T, Punnett L, Warren N, Dillon C, Warren A. The relationship of unions to prevalence and claim filing for work-related upper-extremity musculoskeletal disorders. Am J Ind Med. 2003;44(1):83–93. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cox R, Lippel K. Falling through the legal cracks: the pitfalls of using workers’ compensation data as indicators of work-related injuries and illnesses. Policy Pract Health Saf. 2008;6(2):9–30. [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacEachen E, Clarke J, Franche RL, Irvin E Workplace-Based Return to Work Literature Review Group. Systematic review of the qualitative literature on return to work after injury. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(4):257–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steenstra I, Irvin E, Heymans M, Mahood Q, Hogg-Johnson S. Systematic Review of Prognostic Factors for Workers' Time Away From Work Due to Acute Low-Back Pain: An Update of a Systematic Review. Toronto, Ontario: Institute for Work and Health; 2011. Document 3115. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franche RL, Cullen K, Clarke J, Irvin E, Sinclair S, Frank J Institute for Work & Health (IWH) Workplace-Based RTW Intervention Literature Review Research Team. Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: a systematic review of the quantitative literature. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):607–631. doi: 10.1007/s10926-005-8038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loisel P, Lemaire J, Poitras S et al. Cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analysis of a disability prevention model for back pain management: a six year follow up study. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59(12):807–815. doi: 10.1136/oem.59.12.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mehlum IS, Veiersted KB, Waersted M, Wergeland E, Kjuus H. Self-reported versus expert-assessed work-relatedness of pain in the neck, shoulder, and arm. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009;35(3):222–232. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blumberg SJ, Luke JV, Davidson G, Davern ME, Yu T-C, Soderberg K. Wireless substitution: state-level estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January–December 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009;11(14):1–13. 16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]