Abstract

Learned bird song is influenced by inherited predispositions. The canary is a model system for the interaction of genes and learning on behaviour, especially because some strains have undergone artificial selection for song. In this study, roller canaries (bred for low-pitched songs) and border canaries (whose song is higher pitched, similar to the wild-type) were interbred and backcrossed to produce 58 males that sorted into seven genetically distinct groups. All males were tutored with the same set of songs, which included both low- and high-pitched syllables. Individuals were consistent within genetic groups but differed between groups in the proportion of low- versus high-pitched syllables they learned and sang. Both sex-linked and autosomal factors affected song learning and song production, in an additive manner. Dominant Z-chromosome factors facilitated high-pitched syllable learning and production, whereas the sex-linked alleles associated with the switch to low-pitched syllables under artificial selection were largely recessive. With respect to autosomal effects, the most surprising result is that males in the same genetic group had almost identical repertoires. This result challenges two common preconceptions: that genetic changes at different loci lead to distinct phenotypic changes, and that genetic predispositions affect learning in simple and general ways. Rather, different combinations of genetic changes can be associated with the same phenotypic effect; and predispositions can be remarkably specific, such as a tendency to learn and sing one song element rather than another.

Keywords: canary, Serinus canaria, breeding experiment, behavioural genetics, bird song, vocal learning

1. Introduction

The interacting contribution of genes and environment in the development of behaviour is widely appreciated [1,2], but is still often a mystery in its particulars, especially with respect to learned behaviour. Bird song has long been one of the most productive model systems for understanding the role of learning in behavioural development [3,4], and the genetic basis for song learning is now a consistent focus for research [5,6]. Working from the genotype towards the make-up of the songbird brain, several genes or genetic regions have been implicated in song learning and production (reviewed in [7]). Few such studies have penetrated all the way to specific aspects of the song phenotype, however. Rearing birds in controlled acoustic environments can reveal inherited and learned factors that influence particular vocal features [8–10]. Variation in learned bird song not only between species but also within a species can be underlain by genetic differences [11–13]. Inherited learning biases can be evident, for instance, in the choice of model songs to be imitated versus ignored [14], in the accuracy with which preferred versus non-preferred songs are learned [15], in the ordering or combination of song elements [11,16–18] and in the rate of vocal delivery [15]. Recently, the integration of inheritance and learning in vocal development has been demonstrated strikingly by demonstrations that species-typical song can arise gradually in lineages whose learning has been reset by rearing in isolation [19,20].

The domestic canary Serinus canaria can provide particular insights owing to the fact that strains of this species differ in song, and in some cases have been artificially selected for song features. Controlling young canaries’ social environment and observing strain-specific vocal development are revealing the ways in which genetic variation can underlie diversity in a learned trait [21–23]. Training canaries on the songs of other strains has revealed inherited variation in song learning between strains [24]. Breeding experiments have allowed characterization of strain-specific learning programmes, demonstrated hybrid vigour in song learning and confirmed the quantitative nature of the genetic basis [12,24]. Backcrossing hybrids then showed that some of the genes are sex-linked, whereas others are on autosomes [23,25].

The aim of this study was to determine how the inherited and learned aspects of canary song are integrated by focusing on a feature known to be variable across strains: pitch. Roller canaries have long been selectively bred for simple and low-pitched songs. Border canaries, on the other hand, have been bred for other traits such as plumage; their songs are more complex and range more widely in pitch and are similar to the songs of wild canaries [26,27]. Building on existing evidence for strain-specific tendencies in the learning of high- versus low-pitched songs [12,23], young rollers, borders, their hybrids and backcrosses were presented with several syllable types, some of which were low-pitched and others high-pitched. Observing the ways in which different genetic groups respond to these learning models can specify how variation in inherited factors influences the song learning process. We asked three particular questions in this context. First, how is song variation underlain by autosomal versus sex-linked genes? This is achieved with a backcross breeding design, permitting an assessment of the effect of variation in strain-specific autosomes while holding sex chromosomes constant, and vice versa. Second, how can learned song genetically evolve? Since rollers have been artificially selected for low-pitched songs and against high-pitched songs (which are ancestral and common in borders), the song learning programme in rollers has likely been shaped by recent evolution. A close analysis of the pattern of roller learning from a large number of canary syllable types, including those typical of rollers and ones that are now atypical, might shed light on the particulars of how the roller repertoire has come to differ from that of a canary with typical song. For instance, rollers should be more constrained than borders in their range of acceptable song models; and, assuming learning biases are polygenic traits, hybridization and backcrossing should produce intermediate phenotypes to the purebred strains with respect to song learning. Third, do genetic influences on variation in song act through song learning, song production or both? Biases might be evident in the numbers of different high- versus low-pitched songs in the learned repertoire, or in the proportional contribution of these categories to total song output. Comparing any such biases tests for separate genetic influences on song learning and production.

2. Material and methods

This experiment used a reciprocal backcross design (table 1). Female birds have WZ sex chromosomes and males ZZ, so females inherit their single Z from their father; consequently, one can predict from which strain males have inherited their Z chromosomes. For instance, a hybrid female with a border mother and roller father is WZR, meaning that her mother gave her a W and so her single Z must derive from the roller strain. When this individual is paired with a pure roller male (with sex chromosomes ZRZR), all of her sons are likewise ZRZR. Similarly, a hybrid female with a border father is WZB, with a border Z chromosome. When paired to a roller male, she gives a ZB to all of her sons but her mate gives a ZR, so they are ZBZR. Proportions of autosomal genes deriving from each strain were estimated from the pedigree of each male.

Table 1.

Model syllables in the repertoires of canaries in different genetic groups. As group number increases, so does the genetic contribution of border relative to roller strains, either through autosomes or sex chromosomes.

| groupa | N | Z chromosomes | autosomesb |

group-characteristic imitationsc |

rarer imitationsc |

absent imitationsc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %R | %B | low tours | high tours | low tours | high tours | ||||

| 1. RR | 5 | ZRZR | 100 | 0 | a b2c1c2deh no | b1fgijkm | l (+25 high tours) | ||

| 2. BR-R | 9 | ZRZR | 75 | 25 | b1b2c1c2d m | a e hijklmno | BCDEF ILMN | fg (+16 high tours) | |

| 3. RB-R | 9 | ZBZR | 75 | 25 | a b2c1 | ABCDEFGIJKLMNO WXY | b2 c2dehijklmno | H PQRSTUV | fg |

| 4. BR, RB | 9 | ZBZR | 50 | 50 | a b2 | ABCDEFGIJKLMNO VWXY | b1 c1c2de hikmno | H PQRSTU | fgjl |

| 5. BR-B | 14 | ZRZB | 25 | 75 | ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQR VWXY | ab1b2c1 d mn | STU | c2 efghijklo | |

| 6. RB-B | 7 | ZBZB | 25 | 75 | ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRST WXY | ab1b2c1c2dk no | UV | efghijlm | |

| 7. BB | 5 | ZBZB | 0 | 100 | ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOQ XY | b2 c2 | PRSTUVW | ab1c1defghijklmno | |

aLetters indicate strain (R, roller; B, border) of mother, then father. Hyphenated groups are comprised of backcrosses: each individual is the offspring of a hybrid female and a purebred roller or border.

bZ chromosomes are known from the backcross design; autosomes are average values derived from pedigrees.

cLow tours are roller syllables, shown as lower case letters; high tours are Norwich syllables, shown as upper case letters. In two cases, pairs of syllables were distinct but similar in structure to each other; these are treated separately but marked with subscripts. A total of 16 high tours and 25 low tours were presented as models to all individuals. Group-characteristic imitations were learned by at least 75% of individuals in the group. Underlined group-characteristic syllables were not learned by one individual in the group. Syllables are spaced to align them for visual comparison across genetic groups.

Fifty-eight domesticated canaries were distributed into seven genetic groups, each consisting of males with the same sex-linked and autosomal background (table 1). All canaries (pure strains, hybrids and backcrosses) were bred and reared in acoustic isolation chambers by mothers until independent (about one month), under approximately natural New York (GMT-5) day lengths. Subjects heard no song from before hatching until tutoring. After sexing by subsong production (age one to two months), males remained individually in sound-isolation chambers and were tutored for a month (beginning mid-October), twice daily for two 54 min sessions per day (one in the morning and one in the afternoon), with equal proportions of two kinds of model (tutor) songs on a repeating tape loop (the same tutor songs used in Mundinger [12]). Songs were broadcast at 75–80 dB measured 50 cm from the speaker. Structurally distinctive canary song elements are often called ‘syllables’, and when repeated serially are called ‘tours’. The first kind of tutor song was composed entirely of low tours, simply modulated syllables with the highest fundamental frequency of 4 kHz or lower. The tape loop contained three such low tour songs, recorded from roller canaries, which have been artificially selected to sing only low tours. These three songs together contained 17 different syllable types, each type being represented in at least two of the three songs (electronic supplementary material, figure S1 and Mundinger [12]). The second kind of song was composed entirely of high tours, syllables modulated in a more complex fashion and with higher fundamental frequencies (up to 6 kHz). The tape loop contained three such high tour songs, recorded from Norwich canaries, which have not been artificially selected for song and sing primarily or exclusively high tours. These three songs together contained 25 different syllable types (electronic supplementary material, figure S1 and Mundinger [12]). The tutor tape consisted of nine 6-min tutoring units, where each tutoring unit contained the three high tour songs and the three low tour songs with 2 min of silence between them. The nine tutoring units had different and randomized song orders within tour types. Each session began on high or low tours songs alternately.

When the young birds began to produce full songs in late October, each male was recorded weekly for 12–14 weeks, until late January. No new syllables were discovered in songs, and no changes in relative singing of high versus low tours occurred, after November. At least 10, and usually 20 or more, songs were recorded from each male per week. Each male's entire recorded output was sonographed using a Uniscan II spectral analyser with hard copies produced on 35 mm rolls of Kodak linagraph paper. Spectrograms were compared to the model songs to identify imitations and document developmental changes (see the electronic supplementary material, text). Three parameters were measured for each male: (i) song production, measured as proportion of singing time spent singing high tours; (ii) number and identity of high tour syllables learned and (iii) number and identity of low tour syllables learned. These were measured in the last month of recording in case values changed during development. Variances differed between groups, so two-tailed Mann–Whitney (M–W) U-tests compared song learning and production between pairs of genetic groups. Parametric statistics (linear regression followed by an ANOVA of residuals) was suitable for assessing the relationship between song learning (number of high tours learned) and production (proportion of time spent singing high tours). Statistics were performed by hand or with SYSTAT v. 10 (SPSS, 2000).

3. Results

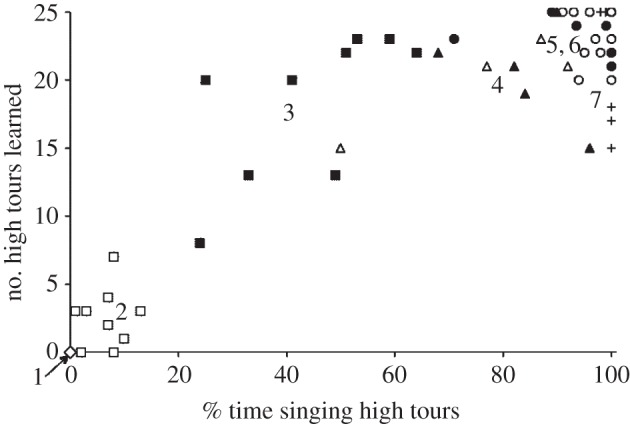

Subject canaries learned an average of 21.6 model syllables (s.d. 7.0, range 5–32), with each of the 42 different possibilities learned by several birds. The variation in model syllable selection was great between breeds. All 25 high tours were represented in the repertoires of the border canaries (group 7 in table 1), but only two of the low tours were sung by any borders. All 17 low tours except one were represented in the repertoires of roller canaries (group 1 in table 1; and the exception was sung by backcrosses), but no roller sang any high tours. The numbers of high and low tours learned were inversely related, such that all tests for differences between strains yielded the same result (in opposite directions) for both, with a minor quantitative exception mentioned later. Song learning and song production were also closely associated: the tendency to learn high tour syllables was highly correlated with the proportion of time birds spent singing them, as expected (Pearson r = 0.88, N = 58, p < 0.00001; figure 1). Thus, all tests for differences between strains in numbers of tours learned and their proportional representation in singing behaviour yielded the same result as well (see the electronic supplementary material, figures S2 and S3). For simplicity, the following results focus on numbers of high tours learned.

Figure 1.

Selective learning and singing behaviour of 58 male canaries including hybrids and backcrosses of roller and border strains, after being trained on the same song models. The number of different high tours learned (Norwich canary syllables, of a total of 25) is on the y-axis, and the proportion of singing time spent on these high tours is on the x-axis. These two variables are highly correlated (Pearson r = 0.88). The males sort into seven genetic groups (1–7) in increasing order of contribution of genes from borders relative to rollers. The separation between groups 2 and 3 supports the sex linkage hypothesis (p = 0.0004 for both axes). The genetic background of subjects is indicated by symbols. Open diamonds are roller canaries (group 1, only one point visible because all values are the same); open squares are hybrids with a roller mother backcrossed with rollers (ZRZR, group 2); filled squares are hybrids with a border mother backcrossed with a roller (ZBZR, group 3); open triangles are RB hybrids, and filled triangles are BR hybrids (together group 4); open circles are border-backcrosses (ZRZB, group 5); closed circles are border-backcrosses (ZBZB, group 6); pluses are border canaries (group 7). Not all data are visible owing to crowding of points in groups 5–7.

(a). Sex-linked effects on high versus low tour learning

Of the seven genetically distinctive groups in this study, two pairs of groups test for the effect of sex-linked genes on song. The first pair for comparison is the two kinds of hybrids backcrossed with rollers. These two groups (2 and 3 in table 1 and figure 1) have 75% roller autosomes on average but differ in sex chromosomes (ZRZR versus ZRZB). These two groups are significantly different, to the point of non-overlap, in both the proportion of high tours sung and in the number of high tours learned (M–W U = 81, n1 = n2 = 9, p = 0.0004 for both variables; figure 1). Border alleles on the Z chromosome are associated with a larger number of high tours learned and—not surprisingly—a larger proportion sung. A tendency towards dominance of border sex-linked alleles with respect to learning high tours is suggested by the fact that in contrast to the large effect of a single copy of a border Z chromosome, the presence of two copies is ambiguous in its effect on the number of high tours learned, even together with an increase in border autosomal alleles (groups 3 versus 6 or 7 in table 1 and figure 1; M–W U (groups 3 versus 6) = 40, n1 = 9, n2 = 7, p = 0.02; U (groups 3 versus 7) = 27, n2 = 5; p = 0.6). The second comparison that tests for an effect of sex chromosome genes is between the two kinds of hybrids backcrossed with borders. These two groups (5 and 6 in table 1 and figure 1) have 75% border autosomes on average but differ in sex chromosomes (ZRZB versus ZBZB). They do not differ in the number of high tours learned (M–W U = 51.5, n1 = 14, n2 = 7, p = 0.9); in fact, both the number of high tours learned and the proportion sung approach their maximum values in these two groups.

(b). Autosomal effects on high versus low tour learning

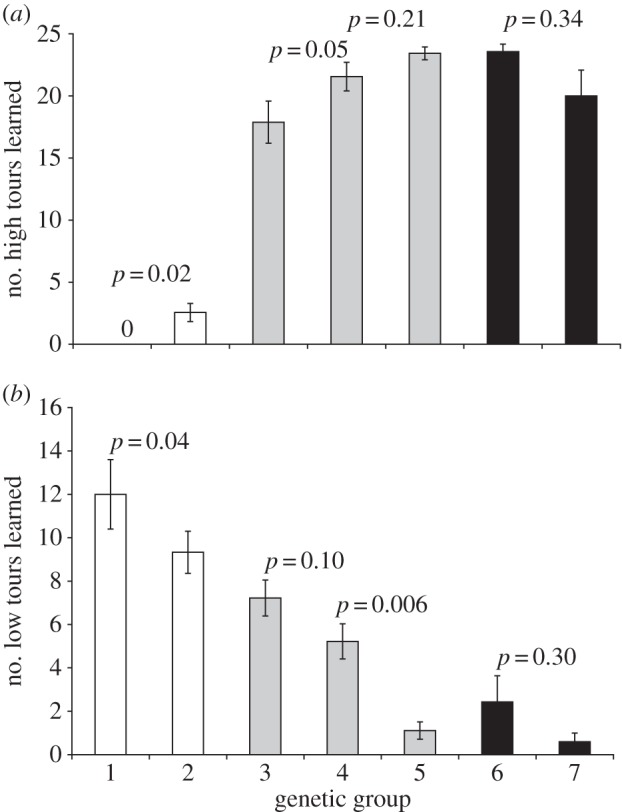

Autosomal effects can be tested by comparing groups with differing autosomes according to pedigree, but with strain-similar sex chromosomes. The crosses generate three such tests. First, rollers and hybrids backcrossed to rollers (groups 1 and 2 in table 1) have all roller sex chromosomes but have 100% versus on average 75% roller autosomes, respectively. These two groups differ in the number of high tours learned (M–W U = 40, n1 = 5, n2 = 9, p = 0.02; figure 2a) and low tours learned (M–W U = 33.5, p = 0.04; figure 2b); thus, 25% border genes can yield high tours in an otherwise roller genome. Second, both kinds of hybrids and hybrids backcrossed to the mother's strain all have the same balanced combination of sex chromosomes, but range from 25 to 50 to 75% border autosomes on average (groups 3, 4 and 5 in table 1). These groups represent a similarly stepwise increase in the number of high tours learned, which was significantly different between 25 and 50% (M–W U = 63, n1 = n2 = 9, p = 0.05; figure 2a), and a decrease in low tours learned, which was significant between 50 and 75% (M–W U = 105.5, n1 = 9, n2 = 14, p = 0.006; figure 2b). Third, borders and hybrids backcrossed to borders (groups 6 and 7 in table 1) have 100 versus 75% border autosomal genes, respectively. The difference in high tours learned between these groups was not significant (M–W U = 23, n1 = 7, n2 = 5, p = 0.4), and both groups were at or near the maximum learnable high tours; but the differences are in the direction of backcrosses singing more of both sorts of tours than did the purebred rollers (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Means (±s.e.) of two song parameters across genetic groups: (a) mean number of high (Norwich) tours learned; (b) mean number of low (roller) tours learned. Differences (M–W U-tests) between groups with similar sex chromosome background (same colour bars) demonstrate autosomal effects. White bars are ZRZR males, black bars are ZBZB males and grey bars are ZBZR or ZRZB males.

(c). Genetic effects on the learning of particular syllable types

A more specific phenotypic description involves tallying actual syllables acquired by genetic group members and determining which ones are extensively shared within a group. Table 1 lists all the model syllables, placing them into three categories for each group: group characteristic, rarer and absent. Each group-characteristic syllable was acquired by 75–100% of the members of that genetic group. Syllables that were not acquired by all group members are underlined in table 1: in these cases one male failed to learn that syllable. Rarer syllables were shared by only 12–54% of the group if a low tour and by 28–68% of the group if a high tour. Otherwise, no males in the group learned the syllable. Following are trends across genetic groups in the way the syllables fell into these three categories.

Males within a genetic group learned almost the same complement of model syllables, and their group-characteristic repertoire differed from those of other groups. The pattern of learning compared across groups exhibits a quantitative pattern. Placing all groups in order of genetic similarity (as in table 1), the same tours learned (or not learned) by members of a genetic group were generally also learned (or not learned) in an adjacent group, along with new additions. Considering, for example, the low tour (roller) syllables the birds failed to learn (see the ‘absent’ column in table 1), all 18 males with 75% roller autosomes (groups 2 and 3) failed to learn the same two syllables fg. All nine males with 50% roller autosomes (group 4) failed to learn syllables jl in addition to fg. All 21 males with only 25% roller autosomes (groups 5 and 6) failed to learn those same four syllables, plus the roller tours ehi. (However, they did differ somewhat in regard to three other roller tours k, m, o.) Finally, all five males with no roller autosomes (group 7) failed to learn 15 of 17 possible low tours, including all seven of those previously mentioned. A similar pattern emerged in high tour learning: moving from groups with fewer to more border autosomes on a background heterozygous for sex chromosomes (groups 3–5 in table 1), most males with 25% border autosomes learned the same 17 high tours, those with 50% learned the same 17 plus one more, and those with 75% learned those 18 plus three more.

Pure rollers (group 1 in table 1) failed to learn any high tours. Some backcrosses with roller sex chromosomes but an average of 25% border autosomes (group 2) learned nine high tours. With the addition of a single border sex chromosome (group 3), all 25 high tours were learned by at least some individuals, and 17 of these (including all nine rarely learned by the previous group) became group characteristic. Increasing border alleles beyond 25% and adding another border sex chromosome had a comparatively minor effect on high tour learning. Interestingly, as with low tour learning, the presence of a minority of alleles of the other strain (here rollers) actually enhanced high tour learning relative to purebred borders, despite the fact that rollers do not sing high tours.

(d). Genetic effects on song learning versus production

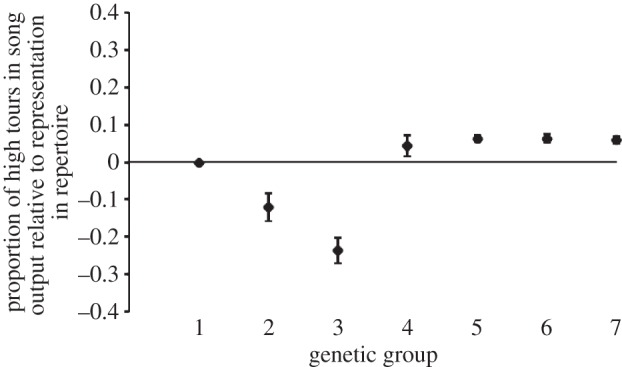

As reported above, song learning and song production were closely associated across individuals. The observed differences in singing across the sample as a whole (without reference to genetic groups) were attributable to biased song learning rather than production: the proportional representation of high versus low tours in an individual's repertoire was not significantly different from their relative representation in the individual's song output (Kolmogorov–Smirnov D58 = 0.137, p > 0.1). To test whether a production bias was present for some genetic groups and not others, the proportions of high tours in individual repertoires were regressed against their representation in song output (R2 = 0.97, p < 0.00001), and the residuals were compared in an ANOVA across genetic groups (F6, 51 = 23.9, p < 0.00001; figure 3). Pairwise comparisons showed that all groups were similar except for the roller backcrosses (the offspring of border–roller hybrids and rollers, groups 2 and 3 in table 1). These two groups spent less time singing high tours than expected based on the proportion of high tours in their repertoires, indicating a production bias in addition to their learning bias (Tukey test, p < 0.0001 for all pairwise comparisons between each of these two groups and all others; figure 3). In genetic terms, birds with no border sex chromosomes but an average of 25% border autosomal alleles (group 2 in table 1) sang high tours 12% less often than expected based on their representation in their repertoire. Individuals with 25% border alleles and a border sex chromosome (group 3 in table 1) sang high tours with 24% less frequency than expected based on their representation in the repertoire. Birds with 50% or more border alleles, however (groups 4–7 in table 1), sang high and low tours with the expected frequency based on their representation in the individuals’ repertoires.

Figure 3.

Proportional representation of high tour syllables in the song output of canaries relative to the proportional representation of high tour syllables in those canaries’ repertoires (ANOVA: F6,51 = 23.9, p < 0.00001). The y-axis is mean residuals (±s.e.) from a regression of proportions of high tours in individual repertoires against their representation in song output (R2 = 0.97, p < 0.00001). Thus, the horizontal line at 0 is the proportion of time birds would be expected to sing high tours based on the number of high tours versus low tours the birds learned. The x-axis is genetic group (table 1), ranging from purebred rollers (group 1) through hybrids and backcrosses to purebred borders (group 7). All groups are similar except for groups 2 and 3, which are the roller backcrosses (the offspring of border–roller hybrids mated with rollers). These two groups spent less time singing high tours than expected based on the proportion of high tours in their repertoires, indicating a production bias in addition to their learning bias (Tukey test, p < 0.0001 for all comparisons between each of these two groups and all others).

4. Discussion

Canary song is learned, but differences in song learning and production between genetic groups demonstrate inherited predispositions that bias or constrain learning in a consistent manner. When social factors are ruled out during development with social isolation and tape tutoring, border canaries learn almost exclusively high tours and roller canaries (which have been artificially selected to sing low-pitched songs) learn only low tours. Hybrids and backcrosses sing a combination of high and low tours, generally consistent with the proportion of genes they possess from the respective strains, suggesting additive effects of several genes. Both sex chromosomes and autosomes are involved in learning predispositions, as was found in earlier studies [23,25]; this study distinguished particular effects that differ between strains. Most of the inherited biases act on song learning, with song production merely following suit, but some genetic groups also have a distinct production bias. Finally and most remarkably, individuals within a genetic group are very similar to each other not only in the proportion of high versus low tours they learned, but also in the individual syllables they learned among the 42 possibilities.

(a). Genetic influences on a learned behaviour

Sex chromosomes and autosomes have distinct effects on song learning in canaries. For instance, on a background of 75% roller autosomes and one roller Z chromosome, whether the other Z chromosome was from the roller or border strain had the largest effect on song learning observed in this study. A single border Z chromosome, regardless of the proportion of border autosomes (from 0.25 to 1), allows an individual to learn any high tour, and tends to recover nearly the full complement of group characteristic high tours. Fewer low tours are group characteristic in birds with a border Z than without one. If this were due to the border Z being inimical to low tour learning, then the border Z would be associated with an increase in the number of low tours lost from a group entirely, but this is not the case; the low tours were rare but not absent. Therefore, the decreased number of group-characteristic low tours in birds with a border Z chromosome is likely an indirect effect of enhancement of high tour learning in the context of a limited repertoire size. Also, the existence of a second border Z chromosome does not substantially increase high tour learning relative to a single one. This supports the hypothesis that border sex-linked alleles for song tend to be dominant, as proposed by Mundinger [12,23]. Whether an individual with only one border Z chromosome inherits it from his mother or father does not seem to have a strong influence on singing behaviour; for instance, hybrids of the two types in genetic group 4 are phenotypically indistinguishable (figure 1 and electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

Border autosomes have a large effect on high tour learning only when compared with the pure roller strain, i.e. compared to having no border autosomes at all. Compared to a purebred roller, 25% border alleles can double a bird's repertoire and introduce nine high tours, even though none of them become group characteristic without a border Z chromosome. Intermediate proportions of border autosomes can slightly increase the number of high tours that become group characteristic, but 25% roller alleles are actually associated with some high tours becoming group characteristic relative to the pure border strain. This is one of two indications in this study of hybrid vigour in song learning; the other is that hybrids consistently have larger repertoire sizes than the purebred strains (table 1). To call this effect hybrid vigour might be misleading, however, since it is not mainly because of poor learning by purebred strains per se, but rather constraints or biases against learning low tours (in borders) or high tours (in rollers). If purebred rollers and borders were poor learners in general, even of their own strain-typical syllables, then we would see hybrids learning more of them than the purebred strains did. This is not the case in rollers, and it is only slightly the case in borders.

The observed combination of genetic effects and strain-specific learning suggests the following scenario for the recent genetic evolution of song in canaries. The border canary, having song that is similar to that of the wild-type, has ancestral autosomal alleles that make high tour singing possible, and slightly increase its likelihood in a quantitative manner; but genes on the Z chromosome fully enable learning of a wide variety of high tours and are responsible for making particular syllables widespread (here, group characteristic). The roller strain, under artificial selection for lower pitched songs for the last few hundred years, underwent most notably a change in genes on the Z chromosome, resulting in a loss of high tour learning. The alleles associated with low tour learning tended to be recessive in relation to the ancestral wild-type alleles. Roller alleles were also associated with a greater diversity in repertoire, with proportionally fewer syllable types being group characteristic and more of them rarer. (Any effect of low to intermediate proportions of roller alleles is difficult to pinpoint because at any fewer than 75% roller autosomes, the dominant border Z chromosome results in a precipitous decline in group-characteristic low tours.) Thus far, this scenario is silent on mechanism, including where in development the inherited biases or constraints act and by what means. This scenario is also silent on the various influences on song learning that are not inherited but differ between environments (see the electronic supplementary material).

(b). How do inherited predispositions act within the learning programme?

In general, song learning involves perception, memorization and sensorimotor practice [28]. Inherited biases or guides to learning can operate at any point in this process. Generally, the biases evident in the first or memorization phase of learned vocal development are considered to manifest themselves as cognitive templates that have been termed ‘innate’ [29], ‘latent’ [4] or ‘preactive’ [28], and which come to bear on the learning process through ‘learning preferences’ [30,31] or ‘selective learning mechanisms’ [32]. The first discovered and still predominant example of an inherited learning preference is the bias towards conspecific song relative to heterospecific song [33]. Learning preferences operating within a species are less commonly documented, and those presented here and previously in canaries [12,23,24] are by far the strongest seen in any bird species to date. This is not surprising, as selective breeding and strain-specific selection for song features have fostered divergence in this trait in canaries. Two other examples of learning preferences have also been discovered that operate at what is usually (though not always) considered to be conspecific. Nelson [34] showed in a model choice trial and in responses after tutoring that young mountain white-crowned sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys oriantha) can be biased in their response to and learning of songs of their own subspecies relative to those of Nuttall's white-crowned sparrow (Z. l. nuttalli). Takahasi & Okanoya [13] conducted a cross-fostering experiment between the white-rumped munia (Lonchura striata) and the Bengalese finch (Lonchura striata domestica) that was domesticated from the munia beginning about 250 years ago. Despite being selected for parenting rather than song, the Bengalese finch has evolved somewhat in its learning programme. Specifically, the constraints on or biases to model choice are more permissive in the Bengalese finch than in the munia, perhaps because of relaxed selection under domestication ([13], see also [35]).

A generality is emerging that the second (sensorimotor or production) phase of song learning is primarily guided by morphological constraints, along with social experience [36–38]. However, this study shows that roller backcrosses do not simply produce high versus low tours at the proportion expected based on their representation in bird repertoires. Rather, these birds exhibit a distinct production bias against high tours. Relative to pure border canaries, those with 25% roller genes learn a larger number of different high tours than purebred borders do, but sing them less often than expected; and those with a roller Z chromosome as well sing high tours even less often. These biases manifested entirely among learned tours, so they must be production-related rather than perceptual or memory-based. Moreover, they are not a result of typical production-phase morphological constraints, as the difference is merely in the proportion of total song output—the bird can obviously produce the syllables in question. Apparently inherited cognitive biases, previously associated with the memorization phase of song learning, can also feature in the production phase of vocal development.

Assigning inherited learning biases to a phase of vocal development is only a rudimentary step towards understanding how they work. A great deal of research, especially in the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) but also in some other species, begins from the genotype and looks for correlated changes in parts of the brain that differ between males and females, or are known to be related to song learning or production [6,7,39,40]. Some important candidate genes for such effects reside on the Z chromosome [40,41], which is consistent with the major sex-linked effects found in this study. Songbird behavioural neurogenetics is moving very quickly, but it has not yet reached the point where particulars of model choice and learning biases as found in this study can be analysed in the light of particular gene effects. However, other features of the canary situation might help us to fill portions of this gap. For instance, this study corroborates past breeding experiments in suggesting aspects of the genetic basis, such as polygenism, dominance and sex linkage [12,23]. Another line of research might be leading to a more mechanistic understanding of the basis for high versus low tour singing. Dooling et al. [42] proposed a hypothesis that songbird auditory sensitivity should be matched to its own singing range, and that canaries such as the roller that were bred for lower pitched songs might have evolved a decreased auditory sensitivity. This is indeed the case for the waterslager, another breed of canary bred for low-pitched songs [43,44], so it might be true of the roller as well. Moreover, the morphological basis for the waterslager's hearing loss is a congenital damage to the inner ear [45,46], and its genetic basis includes a factor (explaining 87–91% of the variation) on the Z chromosome, which is largely recessive [25]. These discoveries highlight the possibility that not only cognitive but also perceptual factors might form at least part of the basis for the evolution of low tour singing (but see [23]). ‘Song canaries’ such as rollers and waterslagers might not be able to learn high tours at least partly because they hear them poorly. If so, this would indicate that artificial selection on song acted by damaging the ears of these birds, resulting in a quantitative and strain-specific hearing loss as at least part of the physiological basis for the low-pitched singing that canary fanciers admire. To whatever extent this is the mechanism of the evolution of song pitch in certain canary breeds, it highlights an important general point: the use of the term ‘learning biases’ or ‘inherited predispositions’ does not imply that the physiological mechanism of the bias must be cognitive: perceptual and gross morphological traits can bias learning as well.

An unexpected feature of the present results that sheds light on how inherited biases influence the learning programme is the peculiar genetic specification of learning not only of high versus low tours but also of particular syllable types. Individuals with a particular complement of strain-specific sex chromosomes and autosomes were consistent in the syllables they learned or did not learn. Furthermore, moving towards more or less representation of the alleles of a strain resulted in an addition or subtraction not only of broadly relevant syllable types (high tours or low tours), but also of particular syllables within those categories. Nearly every individual with 50% or more roller autosomes learned syllables a and b2, for instance, and not a single individual with any border alleles learned f or g. Several syllables, including H, Q, R, d, e, n, o and others, show a consistent syllable-specific pattern of being learned by nearly every member of a group at high proportions of alleles of one strain, shifting stepwise through rarity in the backcrosses and hybrids, to absence at high proportions of the alleles of the other strain (see Results for other examples). Not every syllable showed such consistent patterns, and there are exceptions; but that such patterns are evident at all, even being a general feature of the results, begs explanation. The main reason why this result is surprising is that the autosomal inheritance of all subjects was based on average values. For example, males in group 2 had 75% roller autosomes on average, but because of Mendel's law of independent assortment the individuals in a genetic group varied in the exact percentage and complement of their roller autosomes, and in the heritable factors for song they carried. Another reason the result is surprising is that the inherited learning bias in this study was expected to relate only to general aspects such as fundamental frequency, such that the proportion of high versus low tours might be consistent for a genetic group, but the particular syllables learned would be distributed more stochastically because of the high number of model syllables (42), the multitude of ways syllables can differ, and presumed variation among individuals in subtle aspects of model choice. Perhaps something else about these syllables—whether peculiar to the tutor songs in this study or inherited in a strain-specific fashion—affects salience of syllable types and is governed by many genes on different chromosomes (see the electronic supplementary material). Regardless of the mechanism, the consistency within genetic groups with regard to the learning of particular syllables suggests two features of the way genes and learning interact in vocal development: (i) multiple genotypes can guarantee the same phenotype, and (ii) a learning predisposition can specify not only general features of song but also more distinctive features of individual song elements. Both of these indications are challenging, because testing them and explaining their mechanistic basis require a more sophisticated model of the interaction between genes and learning than we currently have.

Acknowledgements

P.C.M. performed this study, but passed away before he could see a manuscript to publication. He wished to thank Thomas Mundinger for discussions.

The experimentation, housing and care of birds followed the Guidelines for Use of Animals in Research, and operated under IACUC-approved research protocols at Queens College, City University of New York.

Data accessibility

Data are available at 149.4.203.220/array1/Public/MundingerLahti14 together with physical data held at the Department of Biology, Queens College, City University of New York.

Funding statement

Financial support was provided by internal grants at the City University of New York (PSC-CUNY 12259, 13582 and 14061).

References

- 1.Pigliucci M. 2001. Phenotypic plasticity: beyond nature and nurture. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mery F, Burns JG. 2010. Behavioural plasticity: an interaction between evolution and experience. Evol. Ecol. 24, 571–583 (doi:10.1007/s10682-009-9336-y) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorpe WH. 1956. Learning and instinct in animals. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marler P. 1984. Song learning: innate species differences in the learning process. In The biology of learning (eds Marler P, Terrace HS.), pp. 289–309 Berlin, Germany: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomaszycki ML, Adkins-Regan E. 2005. Experimental alteration of male song quality and output affects female mate choice and pair bond formation in zebra finches. Anim. Behav. 70, 785–794 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.01.010) [Google Scholar]

- 6.White SA. 2010. Genes and vocal learning. Brain Lang. 115, 21–28 (doi:10.1016/j.bandl.2009.10.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scharff C, Adam I. 2012. Neurogenetics of birdsong. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 23, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorpe WH. 1958. The learning of song patterns by birds, with especial reference to the song of the chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. Ibis 100, 535–570 (doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1958.tb07960.x) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marler P, Peters S. 1977. Selective vocal learning in a sparrow. Science 198, 519–521 (doi:10.1126/science.198.4316.519) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Podos J, Nowicki S, Peters S. 1999. Permissiveness in the learning and development of song syntax in swamp sparrows. Anim. Behav. 58, 93–103 (doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1140) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guttinger HR, Clauss G. 1982. Song organization in hybrids between goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) and canary (Serinus canaris) in comparison to their parent species. J. Ornithol. 123, 269–286 (doi:10.1007/bf01644361) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mundinger PC. 1999. Genetics of canary song learning: innate mechanisms and other neurobiological considerations. In The design of animal communication (eds Hauser MD, Konishi M.), pp. 369–389 Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahasi M, Okanoya K. 2010. Song learning in wild and domesticated strains of white-rumped munia, Lonchura striata, compared by cross-fostering procedures: domestication increases song variability by decreasing strain-specific bias. Ethology 116, 396–405 (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2010.01761.x) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leitner S, Catchpole CK. 2007. Song and brain development in canaries raised under different conditions of acoustic and social isolation over two years. Dev. Neurobiol. 67, 1478–1487 (doi:10.1002/dneu.20521) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lahti DC, Moseley DL, Podos J. 2011. A tradeoff between performance and accuracy in bird song learning. Ethology 117, 802–811 (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2011.01930.x) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soha JA, Marler P. 2001. Vocal syntax development in the white-crowned sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys). J. Comp. Psychol. 115, 172–180 (doi:10.1037/0735-7036.115.2.172) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner TJ, Naef F, Nottebohm F. 2005. Freedom and rules: the acquisition and reprogramming of a bird's learned song. Science 308, 1046–1049 (doi:10.1126/science.1108214) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plamondon SL, Goller F, Rose GJ. 2008. Tutor model syntax influences the syntactical and phonological structure of crystallized songs of white-crowned sparrows. Anim. Behav. 76, 1815–1827 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.07.029) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belzner S, Voigt C, Catchpole CK, Leitner S. 2009. Song learning in domesticated canaries in a restricted acoustic environment. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 2881–2886 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0669) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feher O, Wang HB, Saar S, Mitra PP, Tchernichovski O. 2009. De novo establishment of wild-type song culture in the zebra finch. Nature 459, U564–U594 (doi:10.1038/nature07994) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metfessel M. 1935. Roller canary song produced without learning from external sources. Science 81, 470–470 (doi:10.1126/science.81.2106.470) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreutzer ML, Vallet EM. 1991. Differences in the responses of captive female canaries to variation in conspecific and heterospecific songs. Behaviour 117, 106–116 (doi:10.1163/156853991×00148) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mundinger PC. 2010. Behaviour genetic analysis of selective song learning in three inbred canary strains. Behaviour 147, 705–723 (doi:10.1163/000579510×489903) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mundinger PC. 1995. Behaviour–genetic analysis of canary song: inter-strain differences in sensory learning, and epigenetic rules. Anim. Behav. 50, 1491–1511 (doi:10.1016/0003-3472(95)80006-9) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright TF, Brittan-Powell EF, Dooling RJ, Mundinger PC. 2004. Sex-linked inheritance of hearing and song in the Belgian waterslager canary. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, S409–S412 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0204) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marler P. 1959. Developments in the study of animal communication. In Darwin‘s biological work (ed. Bell PR.), pp. 150–206 New York, NY: Wiley [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guttinger HR. 1985. Consequences of domestication on the song structures in the canary. Behaviour 94, 254–278 (doi:10.1163/156853985×00226) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marler P. 1997. Three models of song learning: evidence from behavior. J. Neurobiol. 33, 501–516 (doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(19971105)33:5<501::AID-NEU2>3.0.CO;2-8) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Konishi M. 1965. The role of auditory feedback in the control of vocalization in the white-crowned sparrow. Z. Tierpsychol. 22, 770–783 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marler P, Peters S. 1988. The role of song phonology and syntax in vocal learning preferences in the song sparrow, Melospiza melodia. Ethology 77, 125–149 (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1988.tb00198.x) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lachlan RF, Feldman MW. 2003. Evolution of cultural communication systems: the coevolution of cultural signals and genes encoding learning preferences. J. Evol. Biol. 16, 1084–1095 (doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00624.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marler P, Peters S. 1982. Developmental overproduction and selective attrition: new processes in the epigenesis of birdsong. Dev. Psychobiol. 15, 369–378 (doi:10.1002/dev.420150409) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marler P. 1990. Innate learning preferences: signals for communication. Dev. Psychobiol. 23, 557–568 (doi:10.1002/dev.420230703) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson DA. 2000. A preference for own-subspecies’ song guides vocal learning in a song bird. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 13 348–13 353 (doi:10.1073/pnas.240457797) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lahti DC, Johnson NA, Ajie BC, Otto SP, Hendry AP, Blumstein DT, Coss RG, Donohue K, Foster SA. 2009. Relaxed selection in the wild. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 487–496 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marler P, Peters S. 1982. Structural changes in song ontogeny in the swamp sparrow Melospiza georgiana. Auk 99, 446–458 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson DA, Marler P. 1994. Selection-based learning in bird song development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 10 498–10 501 (doi:10.1073/pnas.91.22.10498) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Podos J, Nowicki S. 2004. Performance limits on birdsong production. In Nature‘s music: the science of bird song (eds Marler P, Slabbekoorn H.), pp. 318–342 New York, NY: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomaszycki ML, Peabody C, Replogle K, Clayton DF, Tempelman RJ, Wade J. 2009. Sexual differentiation of the zebra finch song system: potential roles for sex chromosome genes. BMC Neurosci. 10, 24 (doi:10.1186/1471-2202-10-24) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gunaratne PH, et al. 2011. Song exposure regulates known and novel microRNAs in the zebra finch auditory forebrain. BMC Genomics 12, 277 (doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-277) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang YP, Wade J. 2009. Effects of estradiol on incorporation of new cells in the developing zebra finch song system: potential relationship to expression of ribosomal proteins L17 and L37. Dev. Neurobiol. 69, 462–475 (doi:10.1002/dneu.20721) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dooling RJ, Mulligan JA, Miller JD. 1971. Auditory sensitivity and song spectrum of the common canary (Serinus canarius). J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 50, 700–709 (doi:10.1121/1.1912686) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okanoya K, Dooling RJ. 1987. Strain differences in auditory thresholds in the canary (Serinus canarius). J. Comp. Psychol. 101, 213–215 (doi:10.1037/0735-7036.101.2.213) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okanoya K, Dooling RJ, Downing JD. 1990. Hearing and vocalizations in hybrid waterslager–roller canaries (Serinus canarius). Hearing Res. 46, 271–276 (doi:10.1016/0378-5955(90)90008-D) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lauer AM, Dooling RJ, Leek MR, Poling K. 2007. Detection and discrimination of simple and complex sounds by hearing-impaired Belgian waterslager canaries. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 122, 3615–3627 (doi:10.1121/1.2799482) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lauer AM, Dooling RJ, Leek MR. 2009. Psychophysical evidence of damaged active processing mechanisms in Belgian waterslager canaries. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sensory Neural Behav. Physiol. 195, 193–202 (doi:10.1007/s00359-008-0398-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available at 149.4.203.220/array1/Public/MundingerLahti14 together with physical data held at the Department of Biology, Queens College, City University of New York.