Abstract

Laboratory mice are well capable of performing innate routine behaviour programmes necessary for courtship, nest-building and exploratory activities although housed for decades in animal facilities. We found that in mice inactivation of the clock gene Period1 profoundly changes innate routine behaviour programmes like those necessary for courtship, nest building, exploration and learning. These results in wild-type and Period1 mutant mice, together with earlier findings on courtship behaviour in wild-type and period-mutant Drosophila melanogaster, suggest a conserved role of Period-genes on innate routine behaviour. Additionally, both per-mutant flies and Period1-mutant mice display spatial learning and memory deficits. The profound influence of Period1 on routine behaviour programmes in mice, including female partner choice, may be independent of its function as a circadian clock gene, since Period1-deficient mice display normal circadian behaviour.

Keywords: ultrasonic vocalization, courtship, nest building, rearing, novelty

1. Background

Laboratory mice retain a repertoire of innate routine behaviour necessary to survive in natural environments, although housed for decades under artificial conditions [1,2]. However, many of these innate routines are not (or cannot be) performed under standard housing conditions with food and water ad libitum, and are therefore rarely observed or described.

One fundamental influence on innate routine behaviour of most animals is the temporal variation of environmental conditions like the light/dark cycle [3–6]. Current concepts on the usefulness of the circadian clock in terms of evolutionary fitness presume that it serves the anticipation of a rhythmically changing environment, important for proper feeding regulation and other physiological functions [6,7]. In a cold environment, temporal information may serve mice for anticipation of the next night in which temperature lowers, and building of a nest helps to save energy and protect adults as well as offspring. Differences in daytime-dependent behaviour between laboratory and natural conditions have been described in mice, hamsters and fruitflies, suggesting a profound influence of light/dark cycle on the behavioural repertoire of model species [6,8,9]. One gene involved in the circadian clock system in flies and mice is Period1 (Per1) [10–12]. Notably, the insect version of Per1, Per, is involved in circadian, learning and courtship behaviour [10,13,14].

In this work, C3H mice (wild-type: WT) and animals of the same strain lacking a functional Period1 gene (Per1−/−) [12,15,16] were compared regarding body weight, ultrasonic vocalization (USV) and various tests for the comparison of innate routine behaviour [1,17–23].

Data presented here show profound differences between Per1−/− mice and their WT controls in body weight, USV, habituation, explorative and social behaviour, indicating an important influence of the Period1 gene on traits regarding the circadian clock and other physiological systems pointing out the pleiotropic properties of the so-called clock gene Period1.

2. Material and methods

(a). Animals

Per1-deficient (129S-Per1tm1Drw/J) mice [12] and the corresponding WT were both bred back onto a melatonin-proficient C3H/HeN genetic background [15,16]. Health status of the animals was monitored regularly as described previously [24,25].

(b). Housing conditions

Mice were housed under a 12 L/12 D cycle at an ambient temperature of 22 ± 2°C and access to food and water ad libitum. Red light intensity at darkness/night was below 10 lux. Adult male mice were 6–10 months of age during the experiments. Pups tested were 3 days old. Male mice exposed to a female came from standard group housing conditions and had never been in contact with a female post-weaning prior to the start of the experiments. All experiments were conducted with male mice under dim red light using infrared camera detection if not otherwise indicated.

(c). Ultrasonic vocalization

Male mice were housed in sibling groups. For female-induced USV measurements, a male mouse was isolated from the group and placed into an individual cage for at least 24 h prior to the start of the experiment. Females were housed separately and introduced into the experimental context immediately prior to USV recordings. Male and female animals were placed on alternate sides of a clean cage. A translucent plastic plate with holes prevented direct contact and mating but allowed visual, olfactory and some mechanical sensing. All experiments were performed during the dark period, the animal's active phase, between Zeitgeber time (ZT) 13 and ZT18. Zeitgeber time zero (ZT0) marks the beginning of the light phase, ZT12 the beginning of darkness.

USVs were detected using an ultrasound microphone (condenser ultrasound microphone Avisoft CM16/CMPA), an amplifier (UltraSoundGate 116 Hb), recording software (Avisoft recorder) and sound analysis software (Avisoft SASLab Pro; all from Avisoft Bioacoustics, Berlin, Germany). The ultrasound microphone was placed at a distance of 20 cm above the male compartment. In this set-up, USVs were recorded continuously for 480 s with a sampling rate of 250 kHz in the male compartment of the test apparatus. The measurements were conducted with the same male–female pairs on 10 consecutive days. To investigate memory retention or extinction an interval of 30 days was introduced before the last USV measurement after the initial 10 days of the experiment. At the end of the recordings, number of calls (‘call-rate’), call length, time intervals between calls, as well as minimal and maximal frequencies within each USV element and maximal amplitude of the calls were measured using Avisoft SASLab Pro with spectrogram parameters as described previously [26]. A high-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 40 kHz was used because of broadband noise in the lower frequencies. Calls were automatically measured by the function ‘whistle tracking’ with parameters ‘max change’ of frequency modulation set on 32 pixels = 7812 Hz, min duration = 10 ms and hold time 20 ms. Afterwards an experienced experimenter for correct element detection manually screened the spectrograms.

(d). Pup isolation calls

Pups of both genotypes at post-natal day 3 were separated from the mother and placed into a glass beaker padded with nesting material, which was placed on a warming plate. Each pup was then put for 5 min into a sound-attenuated recording chamber equipped with microphone, amplifier and recording software as described above. After the measurements recordings were analysed using Avisoft SASLab Pro.

(e). Female preference

To analyse the preference of a WT female mouse for a male of either WT or Per1−/− genotype, a so-called ‘sociability cage’ (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, The Netherlands) was used [27–29]. The sociability cage is a rectangular box consisting of one centre and two side chambers, divided by walls providing just a small passage to the next chamber. In each of the two side chambers, a small cylindrical wire cage was placed containing either a male of the WT or a male of the Per1−/− genotype. At the beginning of the test, the female was placed into the centre chamber, thereby given the choice between the different genotypes in the right or in the left chamber. The whole test session of 10 min was recorded on video and later the time spent at each cage was analysed by behaviour evaluation software (Ethovision XT, Noldus Information Technology). After each recording session the apparatus was cleaned and in the next session the location of the WT and Per1−/− males was alternated to avoid effects of right or left preference of the WT female.

(f). Nest building

To analyse the nest-building behaviour of WT and Per1−/− mice, a standardized five-point scale protocol was used [22]. Since mice build their nest during the dark period [1], a single condensed piece of hemp fibre (Happi-Mat, Scanbur-Nova SCB, Sollentuna, Sweden) was placed in the cage 1 h before onset of darkness. Twenty-four hours later the status of the nest material was evaluated using a standardized scale [22].

(g). Explorative behaviour/marble burying

Initially, we tested the performance of WT and Per1−/− mice in the ‘marble burying’ set-up, an experimental situation to test mice for their interest in ‘novelty’ [23,28]. It took advantage of the fact that in a fresh conventional mouse cage (Polycarbonate, type II Eurostandard 267 × 207 × 140 mm) filled with a 50 mm layer of litter (Lignocel, Hygienic Animal Embedding, Rettenmaier & Söhne GmbH & Co KG, Rosenberg, Germany) animals explore the cages in all three dimensions by running, rearing and digging. Objects placed in the cage (like marbles) induce explorative behaviour. This includes prolonged digging eventually leading to burying of the marbles [23]. A video recorded during the 30 min of this experiment together with behaviour evaluation software (Ethovision XT, Noldus Information technology) was used to analyse differences in mouse behaviour and quantify behavioural parameters such as time spent for running, rearing and digging as well as the latency before starting these activities.

(h). Data analysis

Statistical differences between groups were determined using GraphPad Prism v. 5.0d.

An ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test was used for comparing the number of USV and the mean and total call duration over the testing interval. The Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn's multiple post-test was used to analyse the differences in peak frequencies and relative power of the USV. Nest building was analysed by Mann–Whitney U-test. To analyse the burying of marbles, the female preference and the body weight the Student's unpaired t-test was used. The appropriate tests were chosen according to data structure and quality. A p-value of less than or equal to 0.05 was considered as significant.

3. Results

(a). Ultrasonic vocalization frequency and amplitude

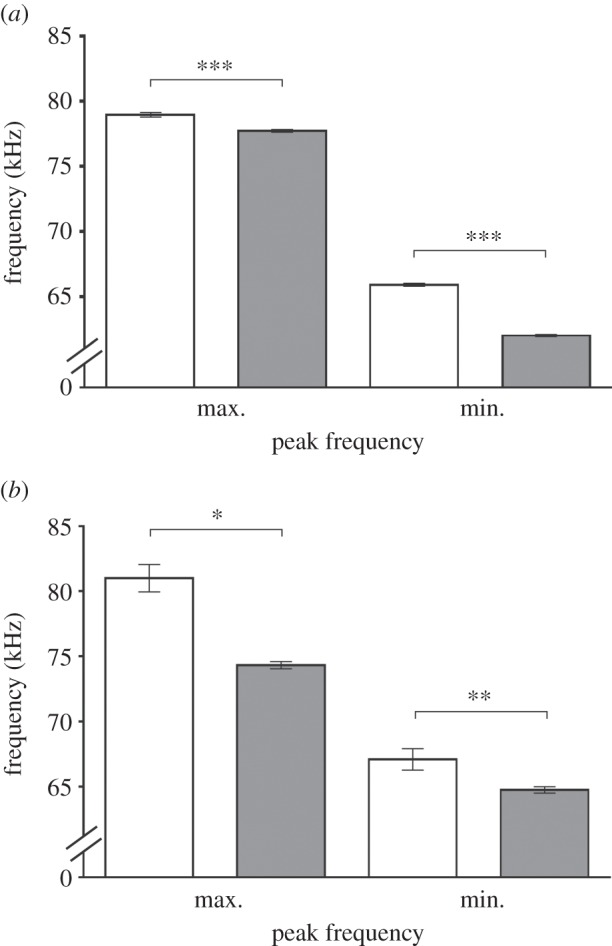

WT (n = 6) and Per1−/−(n = 16) mice showed significant differences in the maximal and minimal peak frequencies (figure 1) and the peak amplitude of USV (figure 2) when confronted with a WT female. At day 2 (figure 1a), the mean maximal peak frequencies of each detected element (USV call) of the WT (78.9 ± 0.2 kHz) differed significantly (p ≤ 0.001) from the Per1−/− (77.7 ± 0.1 kHz) animals. The minimal peak frequencies were also significantly different and, similar to the maximal frequencies, lower in Per1−/− compared with WT (WT: 65.9 ± 0.1 kHz; Per1−/−: 62 ± 0.1 kHz).

Figure 1.

The bar graph shows minimal and maximal peak frequencies of WT (white) and Per1−/− (grey) mice. (a) Mean peak frequency of male ultrasonic vocalizations (USV) at day 2 in WT (n = 6 animals; total calls = 4031) and Period1-deficient (Per1−/−; n = 16 animals; total calls = 11 675) mice. Both maximal and minimal frequency was significantly lower in Per1−/− compared with WT mice. (b) Mean peak frequency of male USV at day 10 in WT (n = 6 animals; total calls = 206) and Period1-deficient (Per1−/−; n = 16 animals; total calls = 1398) mice. Both maximal and minimal frequency was significantly lower in Per1−/− mice compared with WT mice. Data were analysed by Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparison post-test (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001). All values are given as mean ± s.e.m.

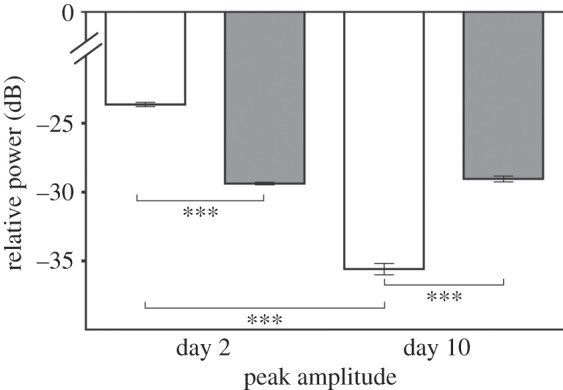

Figure 2.

Shown is the relative power (dB) of the mean peak amplitude of male USV at day 2 and day 10 in WT (n = 6 animals; total calls = 4031) and Period1-deficient (Per1−/−; n = 16 animals; total calls = 11 675) mice. The peak amplitude was significantly lower in Per1−/−(grey) mice compared with WT (white) mice at day 2. By contrast, the mean peak amplitude was significantly higher at day 10 in Per1−/− mice compared with WT mice. WT mice showed a significant difference in the peak amplitude between day 2 and day 10. Data were analysed by Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparison post-test (***p ≤ 0.001). All values are given as mean ± s.e.m.

At day 10, there was still a significant difference in mean maximal (WT: 80.9 ± 0.1 kHz; Per1−/−: 74.3 ± 0.3 kHz) and minimal (WT: 67 ± 0.8 kHz; Per1−/−: 64.7 ± 0.2 kHz) peak frequencies between WT and Per1−/− animals (p ≤ 0.001) (figure 1b).

This lower frequency in USV calling in male Per1−/− mice occurred despite their lower body weight, compared with WT controls (electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

Already 3 days after birth, pup isolation calls (USV emitted by the offspring when separated from their mother) displayed a lower maximal peak frequency in the Per1−/− animals compared with WT (electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

In adult males, both the mean maximal and minimal peak amplitudes (figure 2) exerted a significant difference between WT and Per1−/− animals at day 2 (WT: −23.6 ± 0.2 dB; Per1−/−: −29.8 ± 0.1 dB; p ≤ 0.001) as well as at day 10 (WT: −35.5 ± 0.4 dB; Per1−/−: −29 ± 0.2 dB; p ≤ 0.001). Comparing day 2 with day 10, the peak amplitude of the WT significantly decreased (p ≤ 0.001), while the peak amplitude of Per1−/− mice remained almost identical.

(b). Ultrasonic vocalization habituation behaviour

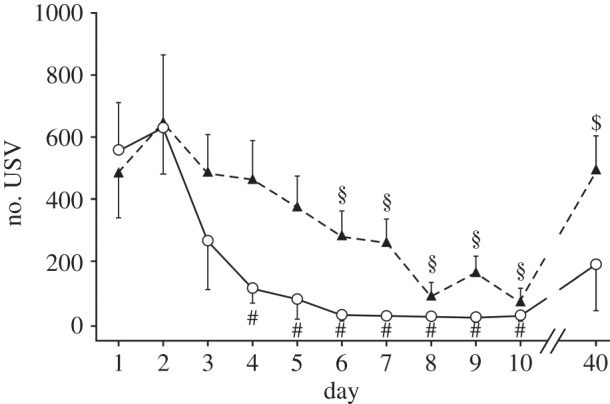

When male mice of either genotype were confronted with a female for 10 consecutive days, a striking difference in the USV was evident. WT mice displayed the highest number of USV calls at day 2 (558 calls ± 157) of the experiment. Then the call rate declined with every experimental day, reaching a significantly lower number of USV emissions on day 4 (113 calls ± 48) compared with day 2 (p ≤ 0.05), leading to a plateau after 6 days (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean number of male USV when confronted with a female per day on 10 consecutive days and after an interval of 30 days (between day 10 and day 40) in WT (n = 6) and Period1-deficient (Per1−/−; n = 16) mice. Compared with the maximal call number at day 2, a significant reduction was observed at day 4 in WT (#) and at day 6 in Per1−/− (§) male mice. After the 30-day interval of no contact to female mice, the call number in the Per1−/− male mice was significantly elevated ($), whereas this was not the case in the WT mice. Data were analysed by ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test (#/§ denotes p ≤ 0.05; $ denotes p ≤ 0.01). All values are given as mean ± s.e.m.

In Per1−/− males, likewise to WT, the number of USV calls per experimental run was the highest at day 2 (649 calls ± 145). However, the decline in daily call rate in the Per1−/− mice reached a significant difference only at day 6 (284 calls ± 78) when compared with day 2 (p ≤ 0.05) (figure 3). At day 8, the call rate of Per1−/− mice reached the level (89 calls ± 42) that WT males had attained already at day 5 (78 calls ± 65). Nonetheless, the call-rate in Per1−/− mice was never as low as the lowest call-rate observed in the WT (day 10: WT = 19 calls ± 17; Per1−/− = 71 calls ± 42). Figure 3 shows properties of habituation behaviour with a delay of habituation observed in Per1−/− compared with WT animals. After 30 days of no contact of the males to a female, the WT males were still ‘habituated’, as they show no significant difference between the 10th and 40th day (p > 0.05). By contrast, the Per1−/− males emitted as many USV calls as at the first day of the experiment (day 11: WT = 189 calls ± 150; Per1−/− = 496 calls ± 107), however, with a significant difference to the 10th day (all differences determined using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, p ≤ 0.01). There were also habituation effects on mean and total call duration (electronic supplementary material, figure S3). Interestingly, the peak amplitude (figure 2) also decreased significantly between day 2 and day 10 in WT but not in Per1−/− mice (Kruskal–Wallis test, p ≤ 0.001). To visualize the structure of USV from WT and Per1−/− mice exemplary spectrograms of day 2 and day 10 are shown (figure 4).

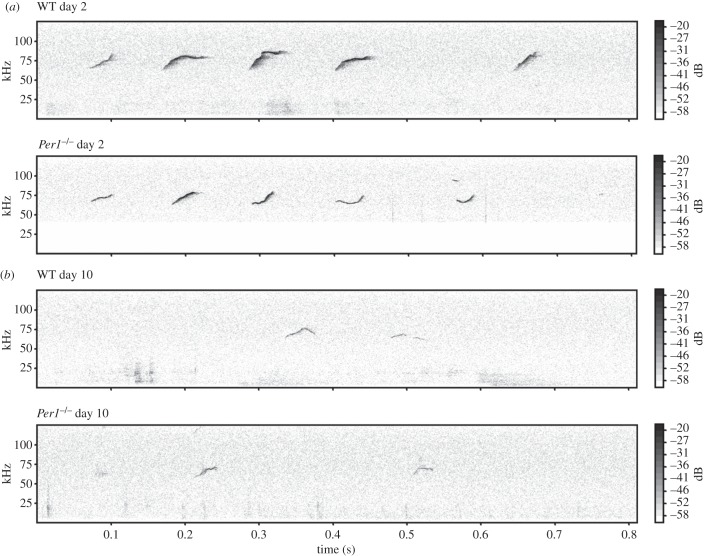

Figure 4.

Shown are exemplary spectrograms of USV at day 2 and day 10 in male (a) WT and (b) Per1−/− mice. Frequency (kHz) and the relative level of signal intensity (dB) are plotted against time (s). Note the lower intensity (grey scale on the right-hand side) of the calls at day 10 compared with day 2.

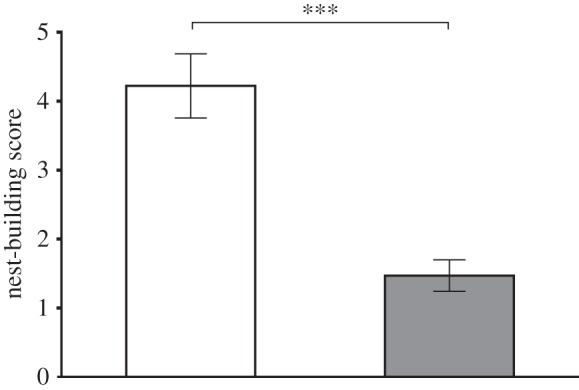

(c). Nest building

For evaluation of nest-building behaviour, we used male WT (n = 9) and Per1−/− mice (n = 17). Only one of the 17 Per1−/− mice built a reasonable nest (score = 4), two reached a score of 3 and one a score of 2, while 11 animals left the nest-building materials unchanged (score = 1; figure 5) over 24 h. Per1−/− mice with score 1, who did not process the nest-building material during the regular 24 h experiment, left nest-building materials unprocessed for up to two weeks. By contrast, the nine WT animals built nests of a high quality with a mean score of 4 of 5 maximal score points. The difference in nest-building score between WT and Per1−/− mice was significant (p ≤ 0.0002).

Figure 5.

Shown is the mean nest-building score in WT (white, n = 9) and Per1−/− (grey, n = 17) male animals (Mann–Whitney U-test; ***p ≤ 0.001). All values are given as mean ± s.e.m.

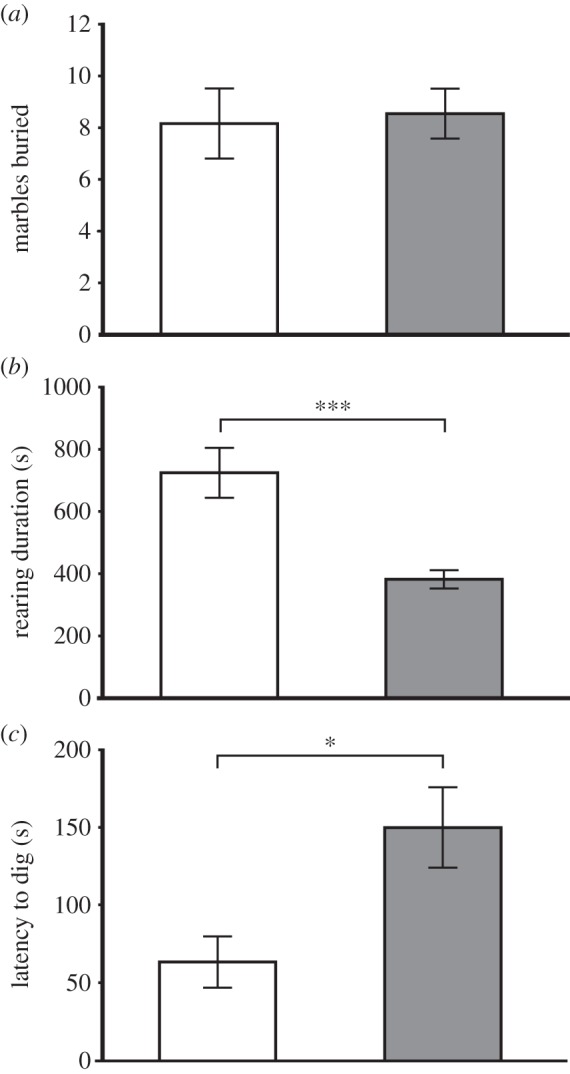

(d). Explorative behaviour/marble burying

In the set-up for the determination of explorative behaviour, Per1−/− (n = 11) mice buried as many marbles as the WT (n = 6) animals over the time of the experiment (figure 6a). However, both the latency time before the animals started to dig or bury (p ≤ 0.0002) (figure 6c) and the time spent with rearing (figure 6b) were significantly different between WT and Per1−/− mice (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 6.

Shown is the test for burying of marbles placed on the surface of the embedding material. (a) Whereas both genotypes were equally efficient in the burying, (b) significant differences were observed in rearing time during the test interval and (c) the latency time before the first burying attempt. Genotype differences were evaluated by unpaired t-test; WT (white): n = 6; Per1−/− (grey): n = 11; ***p ≤ 0.001; *p ≤ 0.05. All values are given as mean ± s.e.m.

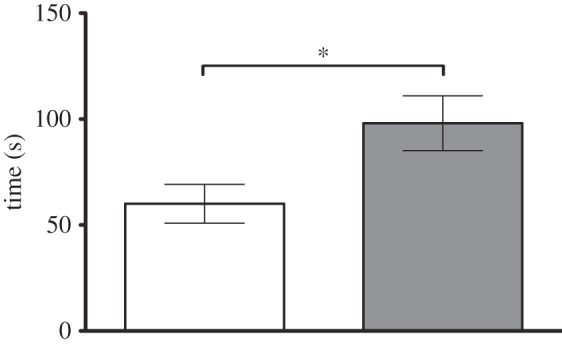

(e). Female preference test

To investigate a preference of WT females (n = 3) for one of the two genotypes, a female mouse was given the choice between WT and Per1−/− males placed in the right or in the left chamber of a two-chamber sociability cage (figure 7). The time WT females spent at the WT male cage (60.6 ± 9.1 s; n = 12) was significantly shorter compared with the Per1−/− males (98.1 ± 12.9 s; n = 12; p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 7.

Shown are the female preference test results. Female WT (white) mice spent significantly more time at the cage of male Per1−/− (grey) when compared with WT (n = 36). Data were analysed by the unpaired t-test (*p ≤ 0.05). All values are given as mean ± s.e.m.

4. Discussion

(a). Physical differences between wild-type and Per1−/− mice

Our data show that male Per1−/− mice confronted with a WT female vocalize at significantly lower frequencies compared with WT male animals. This is surprising as both female [17] and male (this study; electronic supplementary material, figure S1) Per1−/− mice are lighter than their WT controls. Lighter individuals in a given species normally have a higher voice pitch [30,31]. Interestingly, the lighter Per1−/− male mice displayed a lower USV frequency compared with the heavier WT animals.

The amplitude of the USVs was higher in WT compared with Per1−/− mice on day 2. One possible reason for this observation could be differences in hearing capacity between WT and Per1−/− mice. However, we found no difference in the auditory brain stem response, a measure for hearing capacity, between Per1−/− mice and WT control animals (data not shown), and it has been shown that auditory input is not essential for the development of USV [32].

To evaluate whether the altered properties of the USV of male Per1−/− mice cause a different attraction of the female WT we used the female preference test. Indeed, WT females spent more time exploring the Per1−/− male cage area than that of the WT males. One possible explanation for this preference of the WT female for the Per1−/− males may be their lowered USV frequency. It remains to be determined if other qualitative USV differences, like call structure, or a differing scent [33,34], may also be a reason for the higher attraction of the Per1−/− males to WT females [35]. Interestingly, it has been shown that female mice are able to discriminate USV from siblings and genetically unrelated males [36]. Thus, female choice appears to favour the mutant over the WT male, which consequently would lead, in the case of successful mating, to higher genetic diversity of the offspring, a known principle for the elevation of fitness in a population [29,37].

(b). Innate routine behaviour in laboratory mice

Laboratory mice still exhibit innate routine behaviour when provided with appropriate conditions or environments although kept under rather uniform housing conditions for decades [1,2,38]. This is important in the context that hippocampal learning and memory processes differ between mice held in poor or enriched environments [39]. It is also known that mice show elevated activity during night-time when food and water is available ad libitum [6,40]. Therefore, innate routine behaviour must be tested during the dark period to avoid the influence of stress or arousal owing to waking the animals during their sleep phase [2,38,41].

(c). Clock genes and behaviour

Deletion of clock genes causes pronounced cognitive and behavioural effects throughout the animal kingdom [41]. Period1-deficient mice display alterations in glucocorticoid rhythmicity [42], addiction [43], muscle strength [44], colonic motility [45], fertility [17,46] and memory [16].

One of the propositions of this work was that the clock gene Per1 is important for courtship behaviour and influences reproductive success. Evidence for that conjecture comes from altered courtship behaviour in Per-mutant male fruitflies (Drosophila melanogaster) [14,47] and the observation of a smaller litter number under homozygous breeding of Per1−/− mice [17].

Thus Per-genes appear to be involved in reproductive behaviour of both flies [14,47] and mice, as shown here. Interestingly, in sand flies (Lutzomyia spp.), altered ‘courtship song’ owing to a mutated Period gene has recently been proposed to cause speciation [48].

(d). The hippocampus and innate routine behaviour

The hippocampal formation is involved in both learning and the execution of innate routine behaviour [21–23,49]. Examples of such repeated routines tested here include courtship behaviour, social recognition, nest-building and locomotive/explorative aspects of behaviour like latency to start movements, digging or rearing [1,23].

(e). Ultrasonic vocalization-courtship and social behavioural aspects

Under repeated confrontation of a male and a female, the male WT control animals rapidly and significantly reduced the number of calls per day (day 4), whereas Per1−/− males showed no significant reduction of USV call number before day 6. In parallel, the amplitude of the single USVs in WT mice decreased from day 2 to day 10, whereas the amplitude in Per1−/− mice did not change. Such habituation deficiency suggests a learning and/or memory deficit in Per1−/− mice compared with WT. This is interesting since Per1−/− mice were reported to display a phenotype in the radial arm maze test for hippocampus-related memory [16,50]. It is not clear if this habituation reflects ‘social recognition’ or reduced salience of the female as a ‘mating-stimulus’ in the context of the testing set-up [51,52]. In mice, which live in large social groups, such behaviour is important for both energy conservation (to avoid unnecessary fighting) and reproduction [1,2,39].

After an inter-trial interval of 30 days (day 40), the WT males remained habituated, not reacting significantly more than after day 10, whereas the Per1−/− mice emitted as many calls as in day 2. One interpretation of this finding is that the Per1−/− mice do not recall the experimental situation of not being able to socialize or mate, whereas the WT males show long-term retention of the memory task. The alternative interpretation would be recognition of the test female as a known individual by the WT males in comparison with a failure of the Per1−/− mice to memorize or recall a specific individual.

Since social recognition is hippocampus-dependent [21], this might explain the deficits of Per1−/− mice regarding the habituation or social recognition in this task. Taken together, these findings point to a fundamental deficit in both a simple (this study) and a more complex, hippocampus-related behaviour [16] in male Per1−/− mice.

Our data from the USV studies raised our interest in natural routine behaviour apart from courtship. Owing to the habituation phenotype discussed above and the known learning deficit of Per1−/− mice [16], we also examined non-reproductive hippocampus-dependent innate routine behaviour.

(f). Nest building

Nest building in rodents serves heat conservation and reproduction, as well as shelter from predators for both the animal itself and its offspring [22,53]. It requires orofacial and forelimb movement [22,53,54], and is impaired by hippocampal lesions [55]. Both male and female mice build nests, thereby suggesting that the aspects of heat conservation and shelter are at least equally important as reproduction [22]. The overt deficiency of building a proper nest in the Per1−/− mice was somewhat surprising and unexpected, since this behaviour appears fundamental to the animals’ survival [2]. This nest-building deficiency supports our conclusion of hippocampal dysfunction in Per1−/− mice.

(g). Explorative behaviour/marble burying

Longer latency of the Per1−/− mice in the initiation of behaviour was a frequently observed phenomenon. Latency to start a behaviour is a hippocampus-dependent feature and is prolonged by lesion [55]. In the test set-ups for marble burying, the Per1−/− mice spent less time rearing and needed longer for the initiation of the digging behaviour (latency time). These findings may be interpreted in different ways: (i) Per1−/− mice are less interested in the marbles and/or in the new environment, and therefore start exploring later; (ii) Per1−/− mice are less well capable of interpreting the set-up as novel than WT mice; or (iii) Per1−/− mice display anxious behaviour against the novel object in their environment. The latter interpretation is compatible with the observation that Per1−/− mice spend less time rearing, a phenomenon related to hippocampal defects associated with impaired explorative behaviour [55].

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, WT mice are well capable of exercising innate routine behaviour although having been in captivity and rather uniform housing conditions for decades. Per1−/− mice of the same genetic background display significant differences to their WT controls, suggesting strong genetic influence of this clock gene on innate routine behaviour. The observations described here and the recently reported learning deficits in Per1−/− mice suggest fundamental differences in hippocampal function as a potential explanation for the behavioural discrepancies between WT and Per1−/− mice. Such differences displayed in the wild may constitute a basis for speciation in the long run.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Arun Palghat Udayashankar, Dr Oliver Rawashdeh and Prof. Dr Jörg H. Stehle for useful hints, helpful discussions and careful reading of the manuscript, and Jonas Lind for technical assistance. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

All experiments reported here were conducted in accordance to the guidelines of the European Communities Council Directive (89/609/EEC) for humane animal care.

Data accessibility

Raw data are deposited at Dryad (doi:10.5061/dryad.1c0d3).

Funding statement

This work was funded by a grant from the Dr Senckenberg Stiftung to E.M.

References

- 1.van Oortmerssen GA. 1971. Biological significance, genetics and evolutionary origin of variability in behaviour within and between inbred strains of mice (Mus musculus). Behaviour 38, 1–91 (doi:10.1163/156853971X00014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Latham N, Mason G. 2004. From house mouse to mouse house: the behavioural biology of free-living Mus musculus and its implications in the laboratory. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 86, 261–289 (doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2004.02.006) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hastings M, O'Neill JS, Maywood ES. 2007. Circadian clocks: regulators of endocrine and metabolic rhythms. J. Endocrinol. 195, 187–198 (doi:10.1677/JOE-07-0378) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hastings MH, Reddy AB, Maywood ES, Hastings MH, Reddy AB, Maywood ES. 2003. A clockwork web: circadian timing in brain and periphery, in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 649–661 (doi:10.1038/nrn1177) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hastings MH, Goedert M. 2013. Circadian clocks and neurodegenerative diseases: time to aggregate? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 23, 1–8 (doi:10.1016/j.conb.2013.05.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hut RA, Pilorz V, Boerema AS, Strijkstra AM, Daan S. 2011. Working for food shifts nocturnal mouse activity into the day. PLoS ONE 6, e17527 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017527.g004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pittendrigh CS. 1993. Temporal organization: reflections of a Darwinian clock-watcher. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 55, 17–54 (doi:10.1146/annurev.ph.55.030193.000313) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gattermann R, et al. 2008. Golden hamsters are nocturnal in captivity but diurnal in nature. Biol. Lett. 4, 253–255 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0066) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanin S, Bhutani S, Montelli S, Menegazzi P, Green EW, Pegoraro M, Sandrelli F, Costa R, Kyriacou CP. 2012. Unexpected features of Drosophila circadian behavioural rhythms under natural conditions. Nature 484, 371–375 (doi:10.1038/nature10991) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konopka RJ, Benzer S. 1971. Clock mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 68, 2112–2116 (doi:10.1073/pnas.68.9.21123) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun ZS, Albrecht U, Zhuchenko O, Bailey J, Eichele G, Lee CC. 1997. RIGUI, a putative mammalian ortholog of the Drosophila period gene. Cell 90, 1003–1011 (doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80366-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bae K, Jin X, Maywood ES, Hastings MH, Reppert SM, Weaver DR. 2001. Differential Functions of mPer1, mPer2 and mPer3 in the SCN Circadian Clock. Neuron 30, 525–536 (doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00302-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakai T, Tamura T, Kitamoto T, Kidokoro Y. 2004. A clock gene, period, plays a key role in long-term memory formation in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 16 058–16 063 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0401472101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyriacou CP, Hall JC. 1980. Circadian rhythm mutations in Drosophila melanogaster affect short-term fluctuations in the male's courtship song. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 77, 6729–6733 (doi:10.1073/pnas.77.11.6729) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unfried C, Ansari N, Yasuo S, Korf H-W, Gall von C. 2009. Impact of melatonin and molecular clockwork components on the expression of thyrotropin-chain (Tshb) and the Tsh receptor in the mouse pars tuberalis. Endocrinology 150, 4653–4662 (doi:10.1210/en.2009-0609) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jilg A, Lesny S, Peruzki N, Schwegler H, Selbach O, Dehghani F, Stehle JH. 2010. Temporal dynamics of mouse hippocampal clock gene expression support memory processing. Hippocampus 20, 377–388 (doi:10.1002/hipo.20637) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pilorz V, Steinlechner S. 2008. Low reproductive success in Per1 and Per2 mutant mouse females due to accelerated ageing? Reproduction 135, 559–568 (doi:10.1530/REP-07-0434) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zippelius H-M, Schleidt WM. 1956. Ultraschall-Laute bei jungen Mäusen. Naturwissenschaften 43, 502–502 (doi:10.1007/BF00632534) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sales GD. 2010. Ultrasonic calls of wild and wild-type rodents. In Handbook of behavioral neuroscience, vol. 19 (ed. Brudzynski SM.), pp. 77–88 Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wöhr M, Schwarting RKW. 2010. Rodent ultrasonic communication and its relevance for models of neuropsychiatric disorders. e-Neuroforum 1, 71–80 (doi:10.1007/s13295-010-0012-z) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kogan JH, Frankland PW, Silva AJ. 2000. Long-term memory underlying hippocampus-dependent social recognition in mice. Hippocampus 10, 47–56 (doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(2000)10:1<47::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deacon RM. 2006. Assessing nest building in mice. Nat. Protoc. 1, 1117–1119 (doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.170) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deacon RMJ. 2006. Digging and marble burying in mice: simple methods for in vivo identification of biological impacts. Nat. Protoc. 1, 118–121 (doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.19) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ullman-Culleré MHM, Foltz CJC. 1999. Body condition scoring: a rapid and accurate method for assessing health status in mice. Lab. Anim. Sci. 49, 319–323 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foltz CJ, Ullman-Cullere M. 1999. Guidelines for assessing the health and condition of mice. Lab. Anim. 28, 28–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chabout J, Serreau P, Ey E, Bellier L, Aubin T, Bourgeron T, Granon S. 2011. Adult male mice emit context-specific ultrasonic vocalizations that are modulated by prior isolation or group rearing environment. PLoS ONE 7, e29401 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029401) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Perez A, Barbaro RP, Johns JM, Magnuson TR, Piven J, Crawley JN. 2004. Sociability and preference for social novelty in five inbred strains: an approach to assess autistic-like behavior in mice. Genes, Brain Behav. 3, 287–302 (doi:10.1111/j.1601-1848.2004.00076.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverman JL, Yang M, Lord C, Crawley JN. 2010. Behavioural phenotyping assays for mouse models of autism. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 490–502 (doi:10.1038/nrn2851) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts SC, Gosling LM. 2003. Genetic similarity and quality interact in mate choice decisions by female mice. Nat. Genet. 35, 103–106 (doi:10.1038/ng1231) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ey E, Pfefferie D, Fischer J. 2007. Do age- and sex-related variations reliably reflect body size in non-human primate vocalizations? A review. Primates 48, 253–267 (doi:10.1007/s10329-006-0033-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inagaki HH, Takeuchi YY, Mori YY. 2012. Close relationship between the frequency of 22-kHz calls and vocal tract length in male rats. Physiol. Behav. 106, 224–228 (doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.01.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammerschmidt K, Reisinger E, Westekemper K, Ehrenreich L, Strenzke N, Fischer J. 2012. Mice do not require auditory input for the normal development of their ultrasonic vocalizations. BMC Neurosci. 13, 40 (doi:10.1186/1471-2202-13-40) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts SA, Simpson DM, Armstrong SD, Davidson AJ, Robertson DH, McLean L, Beynon RJ, Hurst JL. 2010. Darcin: a male pheromone that stimulates female memory and sexual attraction to an individual male's odour. BMC Biol. 8, 75 (doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-75) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sturm T, et al. 2013. Mouse urinary peptides provide a molecular basis for genotype discrimination by nasal sensory neurons. Nat. Commun. 4, 1616 (doi:10.1038/ncomms2610) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammerschmidt K, Radyushkin K, Ehrenreich H, Fischer J. 2009. Female mice respond to male ultrasonic ‘songs’ with approach behaviour. Biol. Lett. 5, 589–592 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0317) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffmann F, Musolf K, Penn DJ. 2012. Spectrographic analyses reveal signals of individuality and kinship in the ultrasonic courtship vocalizations of wild house mice. Physiol. Behav. 105, 766–771 (doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.10.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindholm AK, Musolf K, Weidt A, König B. 2013. Mate choice for genetic compatibility in the house mouse. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1231–1247 (doi:10.1002/ece3.534) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hedrich HJ. 2012. The laboratory mouse. New York, NY: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. 2000. Neural consequences of environmental enrichment. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1, 191–198 (doi:10.1038/35044558) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daan S, et al. 2011. Lab mice in the field: unorthodox daily activity and effects of a dysfunctional circadian clock allele. J. Biol. Rhythms 26, 118 (doi:10.1177/0748730410397645) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kyriacou CP, Hastings MH. 2010. Circadian clocks: genes, sleep, and cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 14, 259–267 (doi:10.1016/j.tics.2010.03.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dallmann R, Touma C, Palme R, Albrecht U, Steinlechner S. 2006. Impaired daily glucocorticoid rhythm in Per1 Brd mice. J. Comp. Physiol. A 192, 769–775 (doi:10.1007/s00359-006-0114-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong L, et al. 2011. Effects of the circadian rhythm gene period 1 (per1) on psychosocial stress-induced alcohol drinking. Am. J. Psychiatry 168, 1090–1098 (doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111579) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bae K, Lee K, Seo Y, Lee H, Kim D, Choi I. 2006. Differential effects of two period genes on the physiology and proteomic profiles of mouse anterior tibialis muscles. Mol. Cells 22, 275–284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoogerwerf WA, Shahinian VB, Cornelissen G, Halberg F, Bostwick J, Timm J, Bartell PA, Cassone VM. 2010. Rhythmic changes in colonic motility are regulated by period genes. Am. J. Physiol. 298, G143–G150 (doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00402.2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pilorz V, Steinlechner S, Oster H. 2009. Age and oestrus cycle-related changes in glucocorticoid excretion and wheel-running activity in female mice carrying mutations in the circadian clock genes Per1 and Per2. Physiol. Behav. 96, 57–63 (doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.08.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kyriacou CP, Hall JC. 1990. Song rhythms in Drosophila. Trends Ecol. Evol. 5, 125–126 (doi:10.1016/0169-5347(90)90171-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vigoder FM, Araki AS, Bauzer LGSR, Souza NA, Brazil RP, Peixoto AA. 2010. Lovesongs and period gene polymorphisms indicate Lutzomyia cruzi (Mangabeira, 1938) as a sibling species of the Lutzomyia longipalpis (Lutz and Neiva, 1912) complex. Infect. Genet. Evol. 10, 734–739 (doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2010.05.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Squire LRL. 2004. Memory systems of the brain: a brief history and current perspective. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 82, 7 (doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2004.06.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zueger M, Urani A, Chourbaji S, Zacher C, Lipp HP, Albrecht U, Spanagel R, Wolfer DP, Gass P. 2006. mPer1 and mPer2 mutant mice show regular spatial and contextual learning in standardized tests for hippocampus-dependent learning. J. Neural Transm. 113, 347–356 (doi:10.1007/s00702-005-0322-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hammerschmidt K, Radyushkin K, Ehrenreich H, Fischer J. 2012. The structure and usage of female and male mouse ultrasonic vocalizations reveal only minor differences. PLoS ONE 7, e41133 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041133) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Panksepp JB, Jochman KA, Kim JU, Koy JJ, Wilson ED, Chen Q, Wilson CR, Lahvis GP. 2007. Affiliative behavior, ultrasonic communication and social reward are influenced by genetic variation in adolescent mice. PLoS ONE 2, e351 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000351.t002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sager TN, Kirchhoff J, Mork A, Van Beek J, Thirstrup K, Didriksen M, Lauridsen JB. 2010. Nest building performance following MPTP toxicity in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 208, 444–449 (doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lisk RD, Predlow R, Friedman SM. 1969. Hormonal stimulation necessary for elicitation of maternal nest building in the mouse (Mus musculus). Anim. Behav. 17, 730–737 (doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(69)80020-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deacon RMJ, Croucher A, Rawlins JNP. 2002. Hippocampal cytotoxic lesion effects on species-typical behaviours in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 132, 203–213 (doi:10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00401-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data are deposited at Dryad (doi:10.5061/dryad.1c0d3).