Abstract

This study investigated the effects of purple sweet potato leaf extract (PSPLE) and its components, cyanidin and quercetin, on human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) during the inflammatory process. HAECs were pretreated with 100 μg/mL PSPLE or 10 μM quercetin, cyanidin or aspirin for 18 h followed by TNF-α (2 ng/mL) for 6 h, and U937 cell adhesion was determined. Adhesion molecule expression and CD40 were evaluated; NFκB p65 protein localization and DNA binding were assessed. PSPLE, aspirin, cyanidin and quercetin significantly inhibited TNF-α-induced monocyte-endothelial cell adhesion (p < 0.05). Cyanidin, quercetin and PSPLE also significantly attenuated VCAM-1, IL-8 and CD40 expression, and quercetin significantly attenuated ICAM-1 and E-selectin expression (p < 0.05). Significant reductions in NFκB expression and DNA binding by aspirin, cyanidin and quercetin were also observed in addition to decreased expression of ERK1, ERK2 and p38 MAPK (p < 0.05). Thus, PSPLE and its components, cyanidin and quercetin, have anti-inflammatory effects through modulation of NFκB and MAPK signaling. Further in vivo studies are necessary to explore the possible therapeutic effects of PSPLE on atherosclerosis.

Keywords: NFκB, adhesion molecules, human aortic endothelial cells, phytochemicals, pro-inflammation

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory process characterized by increased oxidative stress.1 The resulting adhesion of monocytes to the vascular endothelium and subsequent migration into the vessel wall are the pivotal early events in atherogenesis.2,3 The interaction between monocytes and vascular endothelial cells may be mediated by adhesion molecules, including vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1),4 intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1)5 and E-selectin6 on the surface of the vascular endothelium.

The inflammatory cytokine, TNF-α, activates NFκB7,8 and AP-1,9-11 which are the two major redox-sensitive eukaryotic transcription factors that regulate expression of adhesion molecules.12,13 Because the activation of NFκB and AP-1 could be inhibited to various degrees by different antioxidants, endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) may play an important role in these redox-sensitive transcription pathways in atherogenesis.1,12,13 For example, quercetin, the most abundant flavonoid in the human diet and an excellent free radical scavenging antioxidant,14 attenuated expression of ICAM-1 and E-selectin in human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs).15 García-Mediavilla et al.16 also reported inhibitory effects by quercetin and kaempferol on NFκB activation. Furthermore, the protective effects of diets high in leafy vegetables toward cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease are thought to be derived from their rich antioxidant content.17-19

A previous study found most indigenous purple vegetables from Taiwan reduced low density lipoprotein (LDL) and linoleic acid peroxidation.19 For example, purple sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam] leaves (PSPL), which have the highest polyphenolic content (33.4 ± 0.5 mg gallic acid/g dry weight) of all the commonly grown vegetables in Taiwan, exhibit free radical scavenging ability.20 However, limited information is available regarding the physiologic and biochemical effects of dietary PSPL. In the present study, the effects of PSPL extract (PSPLE) and two of its main components, quercetin and cyanidin, on adhesion molecule expression, endothelial cell-monocyte adhesion and the inflammatory response were assessed in human aortic endothelial cells. Their effect on intracellular redox-sensitive transcriptional pathways, such as NFκB, which may contribute to leukocyte recruitment and vascular inflammation in atherogenesis, was also examined by western blot analysis and electrophoretic mobility shift assays. These studies will help determine the anti-inflammatory effects of PSPLE and its components and form the basis of further in vivo studies.

Results

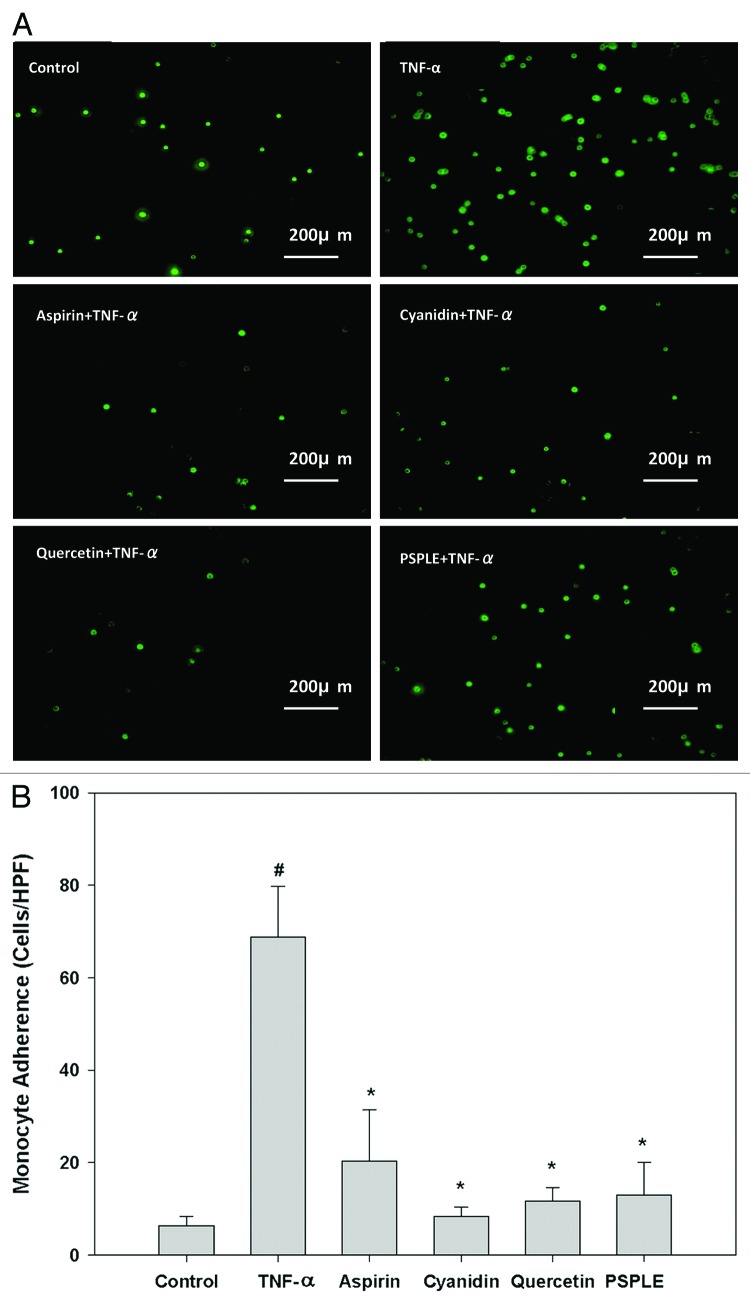

Effects of PSPLE and its components on monocyte-endothelial cell adhesion

As shown in Figure 1, pretreatment of HAECs with 10 μM cyanidin or quercetin as well as 100 μg/mL PSPLE for 18 h significantly suppressed adhesion of U937 monocytes to TNF-α-stimulated HAECs to a similar extent as that observed for 10 μM aspirin, the positive control. Specifically, an 81%, 88% and 84% reduction in adhesion was observed for cyanidin, quercetin and PSPLE, respectively (Fig. 1B; p < 0.05).

Figure 1. Effects of PSPLE and its components on monocyte-endothelial cell adhesion. (A) Representative fluorescent photomicrographs showing the inhibitive effect of pretreatment with 10 µM aspirin, cyanidin or quercetin or 100 µg/mL PSPLE on TNF-α-induced adhesion of fluorescein-labeled U937 cells to human aortic endothelial cells. (B) Summary and statistical analysis of the adhesion assay data in (A). # indicates a significant difference between the TNF-α and control groups, p < 0.05. * indicates a significant difference between the TNF-α and experimental treatment groups, p < 0.05.

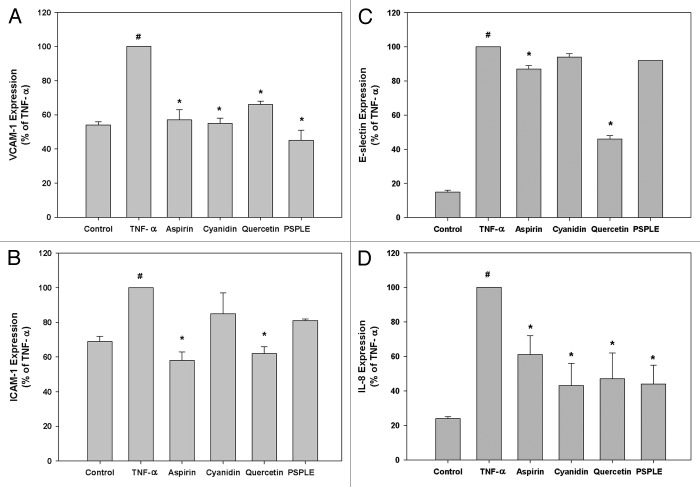

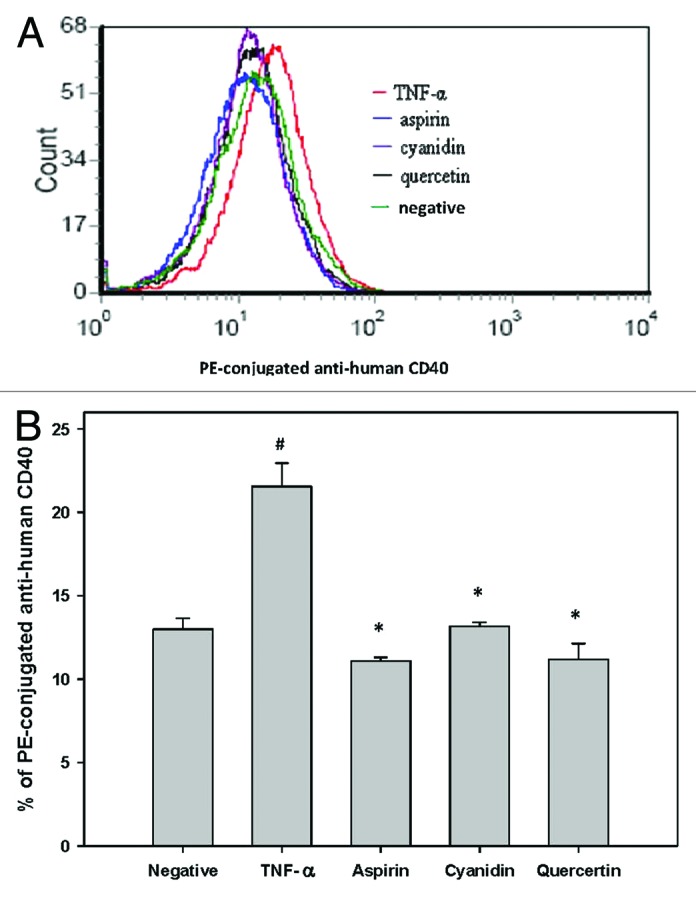

To determine if the reduced cell adherence observed in Figure 1 was due to inhibition of cellular adhesion molecule surface and proinflammatory cytokine expression, ELISAs were performed to determine VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-Selectin and IL-8 expression (Fig. 2) and data are expressed as % of TNF-α. Whereas TNF-α treatment alone significantly increased expression of all adhesion-associated molecules analyzed, pre-treatment of HAECs with aspirin significantly reduced by 43%, 42%, 13% and 39% (Fig. 2A–D, respectively, p < 0.05). Pretreatment of HAECs with cyanidin, quercetin and PSPLE significantly attenuated TNF-α-induced VCAM-1 expression by 45%, 34% and 55%, respectively (Fig. 2A, p < 0.05). Pretreatment of HAECs with cyanidin, quercetin and PSPLE also significantly attenuated TNF-α-induced IL-8 expression by 57%, 53% and 56% respectively (Fig. 2D, p < 0.05). Furthermore, quercetin significantly attenuated ICAM-1 and E-Selectin (Fig. 2B and C, p < 0.05) expression by 38% and 54%, respectively. Furthermore, as compared with the TNF-α group, CD40 surface expression on HAECs was also significantly reduced by aspirin, cyanidin and quercetin by 48%, 39% and 48%, respectively (p < 0.05; Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Effects of PSPLE and its components on expression of adhesion molecules. VCAM-1 (A), ICAM-1 (B), E-selectin (C) and IL-8 (D) expression was determined by ELISA. HAECs were pre-incubated with the indicated samples followed by TNF-α for 6 h. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of three experiments. # indicates a significant difference between the TNF-α treatment and control group, p < 0.05. * indicates a significant difference between the TNF-α and experimental treatment groups, p < 0.05.

Figure 3. Reduced CD40 expression in response to PSPLE components. (A) CD40 expression in untreated cells (green), TNF-α treated cells (red), aspirin treated cells (blue), quercetin treated cells (black) and cyanidin treated cells (purple) was quantified by flow cytometry. (B) Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of three experiments. # indicates a significant difference between the TNF-α treatment and control group, p < 0.05. * indicates a significant difference between the TNF-α and experimental treatment groups, p < 0.05.

Effects of PSPLE and its components on NFκB activity

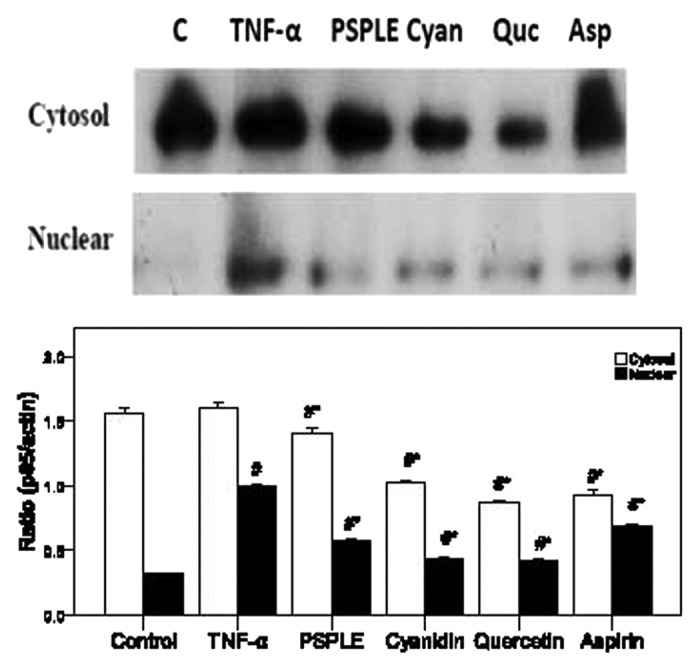

In untreated HAECs, NFκB p65 is solely localized within the cytosol; however, its nuclear translocation was observed upon treatment with TNF-α (Fig. 4; p < 0.05). As compared with the TNF-α group, pretreatment with aspirin, cyanidin, quercetin and PSPLE significantly decreased the expression of NFκB p65 in the cytosol as well as the nuclear compartment (p < 0.05).

Figure 4. Effects of PSPLE and its components on NFκB activity. After HAECs were pretreated with the indicated samples then incubated with TNF-α, cytosolic and nuclear extracts were prepared, and the expression of NFκB p65 was assessed by western blot analysis. A representative image of three similar results is shown (upper panel). Actin served as the loading control for the cytosolic compartment while hnPNPc1/c2 was used for the nuclear extract. Semi-quantitative analysis of three independent experiments are also shown (lower panel). # indicates a significant difference between the TNF-α treatment and control groups, p < 0.05. * indicates a significant difference between the TNF-α and experimental treatment groups, p < 0.05.

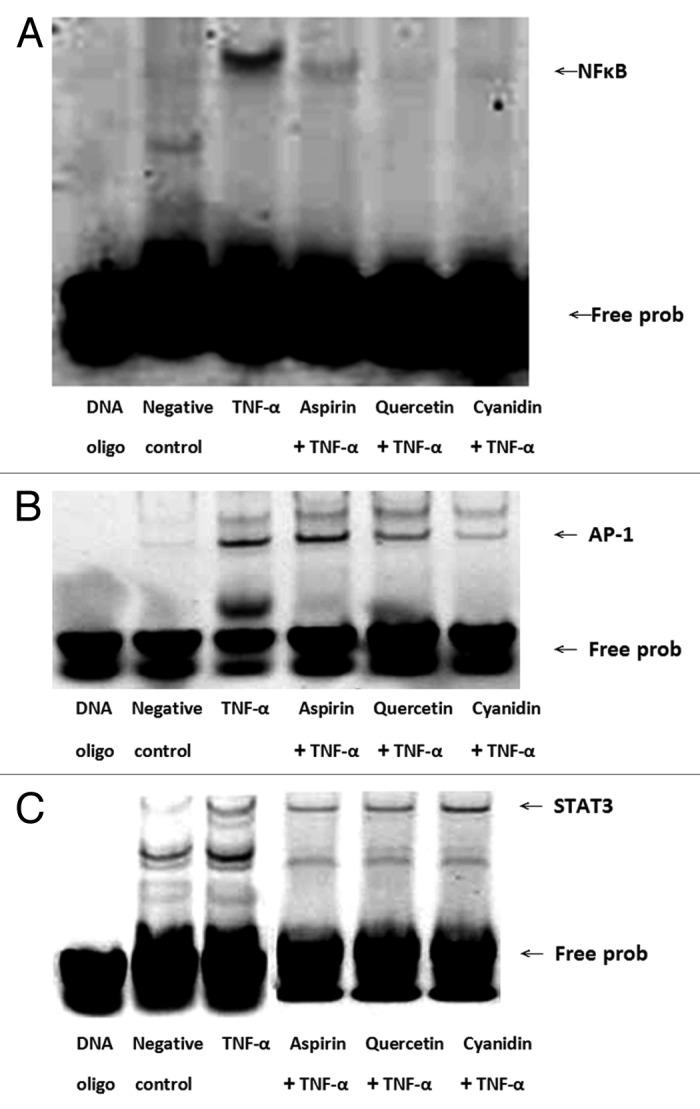

To determine if the reduced expression of NFκB expression in response to treatment with PSPLE or its components resulted in reduced binding of NFκB to DNA, EMSA were performed. As shown in Figure 5A, treatment of TNF-α with HAECs resulted in increased binding of NFκB. However, pretreatment of HAECs with aspirin, cyanidin and quercetin significantly decreased DNA-bound NFκB. In addition, both cyanidin and quercetin pretreatment reduced the level of DNA-bound AP-1 as compared with cells treated with TNF-α alone (Fig. 5B). However, no differences in binding of STAT3 to its target sequence were observed for any treatment group (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. Quercetin and cyanidin inhibit binding of NFκB to target DNA sequence. NFκB, (A) AP-1 (B) and STAT3 (C) transcription factor-DNA interactions were assessed by EMSA using IRDye 700 end-labeled oligonucleotide duplexes.

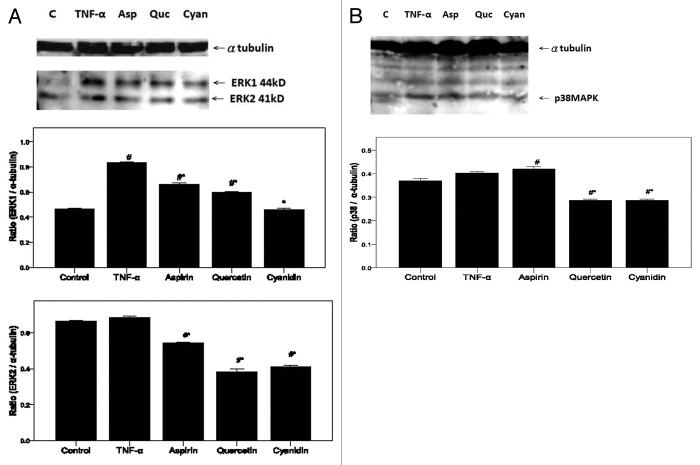

PSPL components reduce ERK and p38 MAPK signaling

Increased ERK and p38 MAPK expression was observed in HAECs treated with TNF-α alone (Fig. 6; p < 0.05). However, pretreatment with PSPL components, cyanidin and quercetin, as well as aspirin significantly inhibited expression of ERK1 and ERK2 as compared with TNF-α alone (Fig. 6A; p < 0.05). Similarly, pretreatment with cyanidin and quercetin significantly inhibited p38 MAPK expression (p < 0.05); however, aspirin had no effect as compared with TNF-α alone (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. PSPL components reduce ERK and p38 MAPK signaling. Expression of (A) ERK-1 and ERK-2 as well as (B) p38MAPK in treated HAECs was determined using western blot analysis. α-tubulin expression was used as the loading control. A representative image of three similar results is shown. Semi-quantitative analysis of three independent experiments are also shown (bottom panel). # indicates a significant difference between the TNF-α treatment and control groups, p < 0.05. * indicates a significant difference between the TNF-α and experimental treatment groups, p < 0.05.

Discussion

Because PSPL exhibit free radical scavenging,20 the anti-inflammatory effects of PSPLE and its components, cyanidin and quercetin, on TNF-α-induced cell adhesion and adhesion molecule expression were determined in the present study. PSPLE, aspirin, cyanidin and quercetin significantly inhibited TNF-α-induced monocyte-endothelial cell adhesion, and reduced cell adhesion molecule expression was also detected. Significant reductions in NFκB expression and DNA binding by aspirin, cyanidin and quercetin were also observed in addition to decreased expression of ERK1 and ERK2 as well as p38 MAPK(except of aspirin pretreatment).

Adhesion of monocytes to the vascular endothelium and subsequent migration into the vessel wall are early events in atherogenesis.2,3 Proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-1(IL-1), interleukin-8 (IL-8), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and CD40,21-24 enhance the surface expression adhesion molecules, such as ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin expression.23,24 Dietary polyphenols, such as catechin and quercetin, significantly reduce binding of monocytes to HAECs,25-27 which is similar to the results of the present study. The reduced cellular adhesion may be due to inhibition of cellular adhesion molecule expression as PSPLE reduced VCAM-1 expression and quercetin reduced VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and E-selectin expression. These results are similar to those recently reported by Martin28 and Loizou et al.29 that demonstrated reduced VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and E-selectin-1 expression in HAECs in response to white button mushrooms and β-Sitosterol.

ROS may play an important role in atherogenesis.1,12,13 In RAW 264.7 macrophages induced by gliadin and IFN-γ, quercetin decreased inducible NOS (iNOS) activity.30 Moreover, consumption of PSPL for 7 d reduced exercise-induced oxidative damage and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion.31 Further studies will be undertaken to evaluate the effects of PSPLE and its components on the levels of ROS generated in an in vivo model of atherogenesis.

Exposure of cells to ROS modifies the activity of various signaling molecules, including those in the ERK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 MAPK pathways.32 Most prominent among these oxidation-sensitive pathways is the NFκB system, which regulates the expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules, such as ICAM-1, VCAM-1,33 platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1), P-selectin and E-selectin.21 Kim et al.34 reported that Armillariella mellea extract induced ICAM-1 expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells through ROS/JNK-dependent signaling pathways leading to the activation of NFκB. In the present study, PSPLE, cyanidin and quercetin reduced both cytoplasmic and nuclear NFκB expression as well as DNA binding in response to TNF-α. It is possible that quercetin and cyanidin influence inhibitory protein of nuclear factor-κBα (IκBα) and of IκB kinase α (IKKα) activity as in García-Mediavilla et al.16 and Min et al.35 In addition, Lee et al.36 reported that quercetin attenuated PMA-induced NFκB, AP-1, p-ERK and p-MEK activities through inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase (MEK) 1 activity. Recently, Liu et al.37 demonstrated that quercetin had protective effects against Pb-induced inflammation through inhibiting COX-2, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α protein expression, by suppressing the MAPKs and NFκB activation. In the present study, reduced expression of ERK1 and ERK2 as well as p38 MAPK was observed in response to cyanidin and quercetin. Further studies are necessary to determine if reduced ERK1/2 and/or p38 MAPK signaling in response to PSPLE components may be responsible for altered NFκB activity.

In the present study, the effects of quercetin were often more pronounced than those observed for PSPLE. Analysis of the concentration of quercetin and cyanidin in PSPLE were revealed concentrations of 0.26 μM and 0.34 μM, respectively (data not shown), which is > 29-fold lower than that used in the quercetin and cyanidin alone treatment groups. Although quercetin is the most abundant flavonoid in the human diet and is an excellent free radical scavenging antioxidant,14 it remains to be determined if the amount of quercetin obtained in the diet is sufficient to ascertain any protective effects. However, reduced exercise-induced oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion was observed after consumption of PSPL for 7 d, indicating a possible benefit from consumption.31

The present study has limitations. For example, although reduced NFκB expression and DNA binding was observed upon treatment with quercetin and cyanidin, the mechanism was not assessed and will be the topic of further studies. In addition, the present results were obtained using in vitro studies and must be corroborated in an in vivo model of atherogenesis similar to that reported by Miyazaki et al.38 in which anthocyanins from purple sweet potato suppress the development of atherosclerotic lesions. In our early studies, black bean significantly prolonged LDL lag time and decreased the atheroma region of aortic arch and thoracic aorta in hypercholesterolemic NZW rabbits (unpublished data). We also demonstrated that black soybean extract and its components, such as genistein, daidzein and cyanidin, significantly decreased adhesion of U937 monocytic cells to TNF-α-stimulated HAECs and reduced adhesion molecules expression (VCAM-1 and ICAM-1) as well as NFκB-p65 expression (unpublished data). This is particularly important given the opposing effects of polyphenols from PSPL obtained using in vitro and ex vivo studies.39

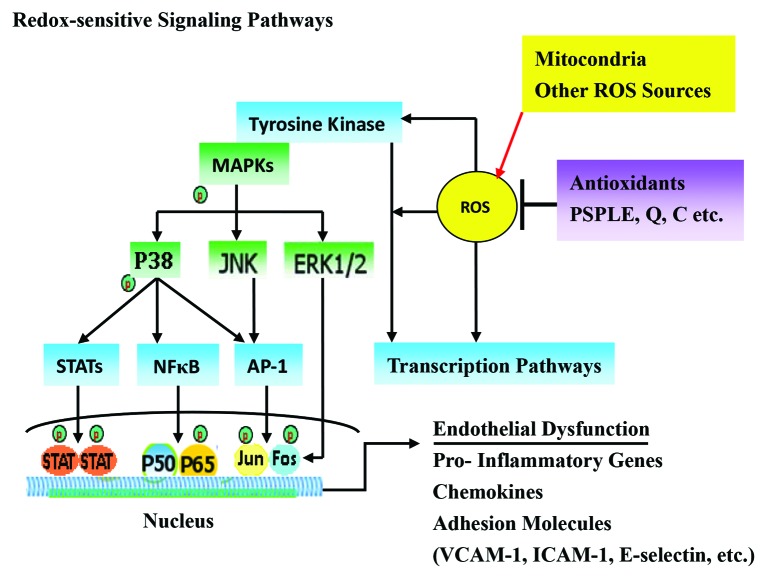

In conclusion, the antioxidative components of PSPLE, quercetin and cyanidin, may downregulate intracellular redox-dependent signaling pathways in HAECs upon TNF-α stimulation, which may prevent ROS-mediated endothelial cell dysfunction (Fig. 7). These results form a theoretical basis of further in vivo studies to assess the therapeutic potential of pytochemicals as an anti-inflammatory for use in cytokine-induced vascular disorders, including atherosclerosis.

Figure 7. The mechanism by which PSPLE and its components influence redox-sensitive signaling pathways in endothelial cells. The antioxidative components of PSPLE, quercetin and cyanidin, may downregulate intracellular redox-dependent signaling pathways in HAECs upon TNF-α stimulation, which may prevent ROS-mediated endothelial cell dysfunction.

Materials and Methods

Purple sweet potato leaf extract preparation

Purple sweet potato was generously provided by Dr. Zhi-Wei Yang, who also identified them from the NTU Experimental Farm, College of Bioresources and Agriculture, National Taiwan University. After the PSPLs were harvested in June of 2005, they were divided into eight individual batches, lyophilized using a Freeze Dryer (FD-5060, Panchum Scientific Corp.), ground, and stored at −80°C until future use. An extract was produced from 5 mg of the stored PSPL powder with a 5-fold volume of methanol at room temperature and filtered through Whatman #1 filter paper. The remaining residue was re-extracted thrice until it was colorless. The three extracts were combined, concentrated to a powder by Freeze Dryer (FD-5060, Panchum Scientific Corp.), and stored at −20°C until future use.

Cell cultures and treatment

HAECs (Clonetics) were grown in Medium 200 (GIBCO Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% low serum growth supplement (LSGS; GIBCO Invitrogen) and 10% FBS (GIBCO Invitrogen) in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C in plastic flasks in an incubator (Astec Co. Ltd.) as described by Vielma et al.40 The human monocytic cell line, U937 cells (American Type Culture Collection), was grown in suspension culture in RPMI-1640 (GIBCO Invitrogen) containing 10% FBS (Sigma) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic mixture (Sigma) in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C. After incubation with pytochemicals and aspirin, or TNF-α, cell viability was assessed using trypan blue exclusion method or MTT assay using a TE-2000U microscope (Nikon Corporation) and was always greater than 90%. As determined by the MTT assay, the greatest cell viability was observed in cells treated with 100 μg PSPLE, 10 μM quercetin or 10 μM cyanidin with decreased cell viability with concentrations > 20 μM for quercetin and cyanidin (data not shown). Therefore, subsequent analyses to determine the effects of the phytochemicals used the following concentrations: 100 μg PSPLE, 10 μM quercetin and 10 μM cyanidin.

Cell adhesion assay

To explore the effect of phytochemicals on endothelial cell-monocyte interactions, the adherence of U937 cells to TNF-α-activated HAECs was examined under static conditions. HAECs were grown to confluence in 24-well plates and pretreated with 100 μg/mL PSPLE, 10 μM quercetin or cyanidin, as in Wang et al.,41 or aspirin, which served as a positive control as in Chen et al.,42 for 18 h, the point at which maximal inhibition of adhesion molecule expression was observed by Chen et al.43 After the preincubation with the phytochemicals, HAECs were incubated with TNF-α (2 ng/mL, Sigma) for 6 h, which was the concentration and time point where maximal surface expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 was observed by Chen et al.43 These treatment conditions are similar to those of Lotito et al.,44 who demonstrated inhibition of E-selectin and ICAM-1 expression in HAECs by 30 μM quercetin treatment for 18 h and combined treatment with 100 U/mL TNF-α for an additional 7 h.

The adhesion assays were then performed as previously described, with minor modification.45 Injured endothelium expresses adhesion molecules, such as VCAM and ICAM, which permit interaction with monocytes and T-lymphocytes. U937 cells represent a human monocyte cell line and used to evaluate the effects of PSPLE and its components on endothelial cell-leukocyte interactions. Antioxidants found within PSPLE may inhibit endothelial expression of adhesion molecules and/or the endothelial adhesiveness to circulating monocytes. Briefly, U937 cells were labeled with 10 μmol/L of the fluorescent dye, 2,7-bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF-AM, Molecular Probes), at 37°C for 1 h in RPMI-1640 medium, and subsequently washed by centrifugation. Confluent HAECs in 24-well plates were incubated with labeled U937 cells (1 × 106 cells/mL) at 37°C for 1 h. Nonadherent monocytes were removed, and plates were gently washed twice with PBS. The numbers of adherent monocytes were determined by counting four fields per x100 high-power-field well and photographed using a Zeiss Axio Mager Z1 Upright Fluorescence Microscope. Four randomly chosen high-power fields were counted per well. Experiments were performed in duplicate or triplicate and were repeated at least 3 times.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The effects of pytochemicals and aspirin on the HAECs surface expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-selectin and IL-8 were analyzed by ELISA using RayBio ELISA Kits (RayBiotech). The sensitivity of the ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin and IL-8 kits was less than 74.07 pg/mL. As indicated by the manufacturer (RayBiotech), the minimum detectable dose of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin and IL-8 are typically 20 pg/mL, 1.5 pg/mL, 30 pg/mL and 1.8 pg/mL, respectively.

Following manufacturer’s instructions, HAECs cultured at 95% confluence in 24-well microplates were incubated with pytochemicals 18 h before activation or during the 6 h TNF-α activation period. The monolayers were washed three times with cool PBS, and cells were lysed with 1 mL CelLytic Cell Lysis Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), vortexed, incubated on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 30 min at 4°C (Beckman Coulter Inc.). Aliquots (100 μL) of the supernatant were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until later use.

The sICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-Selectin and IL-8 present in an aliquot was captured by the immobilized antibody after an overnight incubation at 4°C. The wells are washed four times with 0.1% Tween-20 in PBS, and 100 μL of 1 × biotinylated primary antibody specific for sICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-Selectin or IL-8 was added for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, 100 μL of HRP-conjugated streptavidin was added to the wells for 45 min at room temperature. After another wash, 100 μL 3,3′,5,5′- tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate solution was added to the wells for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. After addition of 50 μL 2 M sulfuric acid, the intensity of the color is measured at 450 nm using a Varioskan Flash ELISA plate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Nuclear protein isolation

Protein extracts were prepared as described by Min et al.46 Briefly, after cell activation for the indicated times, cells were washed in 1 mL ice-cold PBS, centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min, resuspeded in 400 μL ice-cold hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, pH 7.9), incubated on ice for 10 min, vortexed, and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 30 sec. The supernatant was collected and stored in −70°C for cytosolic protein analysis. Pelleted nuclei were gently resuspended in 44.5 μL ice-cold extraction buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9 with 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.42 M NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA and 25% glycerol) with 5 μL 10 mM DTT and 0.5 μL Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, (Sigma), incubated on ice for 20 min, vortexed, and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Aliquots of the supernatant that contained nuclear proteins were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C.

Western blot analysis

Total cytosolic and nuclear lysates were subjected to 12% SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad Laboratories) after which proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad). Membranes were probed with a mouse monoclonal NFκB p65 antibody (BD Biosciences) or rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed to p38MAPK and ERK1/2 (Millipore Corporation). After incubation in secondary antibodies consisting of IRDye 800CW-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or IRDye 800CW-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (LI-COR Biosciences) for 60 min at room temperature with gentle shaking, the membrane was washed four times for 5 min each at room temperature in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 and gentle shaking. After a final rinse, the membrane was scanned using an AlphaEaseFC (Alpha Innotech Corporation) to analyze the spot density. In determining the relative density of the protein expression, the internal control was set at 100%.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay for NFκB, AP-1 and STAT3

The binding reaction consisted of 1 μL 10 × binding buffer (100 mM TRIS, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT, pH 7.5), 5 μL H2O, 2 μL 25 mM DTT/2.5%Tween-20, 1 μL IRDye 700-labeled EMSA oligonucleotides specific for NFκB (5′-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3′ and 3′-CGC TTG ATG ACT CAG CCG GAA-5′), AP-1 (5′-CGC TTG ATG ACT CAG CCG GAA-3′ and 3′-GCG AAC TAC TGA GTC GGC CTT-5′), or STAT3 (5-GAT CCT TCT GGG AAT TCC TAG ATC-3′ and 3′-CTA GGA AGA CCC TTA AGG ATC TAG-5′) (Sigma), 1 μL poly(dI•dC) and 1 μL nuclear extract (as prepared above), which was incubated at room temperature for 20 min in the dark. After 1 × Orange Loading Dye (LI-COR Biosciences) was added, the binding reaction was loaded onto a native 4% polyacrylamide gel and separated by electrophoresis at 90V for 40 min. The gels were scanned using an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences).

Flow cytometry

Surface expression of CD40 was analyzed on HAECs using a Becton Dickinson FACSCanto (BD Biosciences) as described by Ferran et al.47 Briefly, HAECs were grown to confluence in 24-well plates (1 × 106/mL), pretreated with phytochemicals and aspirin for 18 h, and stimulated with TNF-α for 6 h. HAECs were trypsinized and incubated with PE mouse anti-human CD40 (0.25 μg/20 μL; PharMingen) in 1 mL Medium 200 without FBS for 30 min at 4°C. Subsequently, the cells were washed twice with PBS, centrifuged at 1,000 rpm × 3 min. Finally, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in Dulbecco’s PBS (Sigma) for 30 min at 4°C and centrifuged at 1,000 rpm × 10 min at 4°C. After the cells were washed and resuspended in Dulbecco’s PBS, they were analyzed in a BD FACSCanto flow cytometer using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). At least 5,000 viable cells per condition were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

All the data are expressed as a mean ± standard deviation, and statistical significance was analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s Range Test at a 0.05 significance level.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC 95-2320-B-034-001 and NSC 96-2320-B-034-001).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/celladhesion/article/23649

References

- 1.Palinski W. United they go: conjunct regulation of aortic antioxidant enzymes during atherogenesis. Circ Res. 2003;93:183–5. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000087332.75244.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libby P. Molecular bases of the acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 1995;91:2844–50. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.91.11.2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362:801–9. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cybulsky MI, Gimbrone MA., Jr. Endothelial expression of a mononuclear leukocyte adhesion molecule during atherogenesis. Science. 1991;251:788–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1990440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poston RN, Haskard DO, Coucher JR, Gall NP, Johnson-Tidey RR. Expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in atherosclerotic plaques. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:665–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson M, Hadcock SJ, DeReske M, Cybulsky MI. Increased expression in vivo of VCAM-1 and E-selectin by the aortic endothelium of normolipemic and hyperlipemic diabetic rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:760–9. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.14.5.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiDonato JA, Hayakawa M, Rothwarf DM, Zandi E, Karin M. A cytokine-responsive IkappaB kinase that activates the transcription factor NF-kappaB. Nature. 1997;388:548–54. doi: 10.1038/41493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyriakis JM. Activation of the AP-1 transcription factor by inflammatory cytokines of the TNF family. Gene Expr. 1999;7:217–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu Y, Lin JH, Liao HL, Friedli O, Jr., Verna L, Marten NW, et al. LDL induces transcription factor activator protein-1 in human endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:473–80. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.18.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin T, Cardarelli PM, Parry GC, Felts KA, Cobb RR. Cytokine induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene expression in human endothelial cells depends on the cooperative action of NF-kappa B and AP-1. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1091–7. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Müller JM, Rupec RA, Baeuerle PA. Study of gene regulation by NF-kappa B and AP-1 in response to reactive oxygen intermediates. Methods. 1997;11:301–12. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manna SK, Zhang HJ, Yan T, Oberley LW, Aggarwal BB. Overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase suppresses tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis and activation of nuclear transcription factor-kappaB and activated protein-1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13245–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross JA, Kasum CM. Dietary flavonoids: bioavailability, metabolic effects, and safety. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:19–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.111401.144957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lotito SB, Frei B. Dietary flavonoids attenuate tumor necrosis factor α-induced adhesion molecule expression in human aortic endothelial cells. Structure-function relationships and activity after first pass metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37102–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.García-Mediavilla V, Crespo I, Collado PS, Esteller A, Sánchez-Campos S, Tuñón MJ, et al. The anti-inflammatory flavones quercetin and kaempferol cause inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase-2 and reactive C-protein, and down-regulation of the nuclear factor kappaB pathway in Chang Liver cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;557:221–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayase F, Kato H. Antioxidative components of sweet potatoes. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1984;30:37–46. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.30.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang DJ, Lin CD, Chen HJ, Lin YH. Antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of sweet potato. Bot Bull Acad Sin. 2004;45:179–86. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang SC, Lo HF, Lin KH, Cheng TJ, Yang CM, Chao PY. The antioxidant capacity of extracts from Taiwan indigenous purple vegetables. J Taiwan Soc Hort Sci. 2013 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin KH, Chao PY, Yang CM, Cheng WC, Lo HF, Chang TR. The effects of flooding and drought stresses on the antioxidant constituents in sweet potato leaves. Bot Stud (Taipei, Taiwan) 2006;47:417–26. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerard C, Rollins BJ. Chemokines and disease. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:108–15. doi: 10.1038/84209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dinarello CA. Proinflammatory cytokines. Chest. 2000;118:503–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollenbaugh D, Mischel-Petty N, Edwards CP, Simon JC, Denfeld RW, Kiener PA, et al. Expression of functional CD40 by vascular endothelial cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182:33–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karmann K, Hughes CC, Schechner J, Fanslow WC, Pober JS. CD40 on human endothelial cells: inducibility by cytokines and functional regulation of adhesion molecule expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4342–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aruoma OI, Spencer JP, Mahmood N. Protection against oxidative damage and cell death by the natural antioxidant ergothioneine. Food Chem Toxicol. 1999;37:1043–53. doi: 10.1016/S0278-6915(99)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koga T, Meydani M. Effect of plasma metabolites of (+)-catechin and quercetin on monocyte adhesion to human aortic endothelial cells. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:941–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.5.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meng CQ, Somers PK, Hoong LK, Zheng XS, Ye Z, Worsencroft KJ, et al. Discovery of novel phenolic antioxidants as inhibitors of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression for use in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Med Chem. 2004;47:6420–32. doi: 10.1021/jm049685u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin KR. Both common and specialty mushrooms inhibit adhesion molecule expression and in vitro binding of monocytes to human aortic endothelial cells in a pro-inflammatory environment. Nutr J. 2010;9:29. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loizou S, Lekakis I, Chrousos GP, Moutsatsou P. Beta-sitosterol exhibits anti-inflammatory activity in human aortic endothelial cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54:551–8. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Stefano D, Maiuri MC, Simeon V, Grassia G, Soscia A, Cinelli MP, et al. Lycopene, quercetin and tyrosol prevent macrophage activation induced by gliadin and IFN-gamma. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;566:192–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang WH, Hu SP, Huang YF, Yeh TS, Liu JF. Effect of purple sweet potato leaves consumption on exercise-induced oxidative stress and IL-6 and HSP72 levels. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:1710–5. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00205.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saito Y, Hojo Y, Tanimoto T, Abe J, Berk BC. Protein kinase C-alpha and protein kinase C-epsilon are required for Grb2-associated binder-1 tyrosine phosphorylation in response to platelet-derived growth factor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23216–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ju J, Naura AS, Errami Y, Zerfaoui M, Kim H, Kim JG, et al. Phosphorylation of p50 NF-kappaB at a single serine residue by DNA-dependent protein kinase is critical for VCAM-1 expression upon TNF treatment. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41152–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.158352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim YS, Im J, Choi JN, Kang S-S, Lee YJ, Lee CH, et al. Induction of ICAM-1 by Armillariella mellea is mediated through generation of reactive oxygen species and JNK activation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Min SW, Ryu SN, Kim DH. Anti-inflammatory effects of black rice, cyanidin-3-O-beta-D-glycoside, and its metabolites, cyanidin and protocatechuic acid. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010;10:959–66. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee KW, Kang NJ, Heo YS, Rogozin EA, Pugliese A, Hwang MK, et al. Raf and MEK protein kinases are direct molecular targets for the chemopreventive effect of quercetin, a major flavonol in red wine. Cancer Res. 2008;68:946–55. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu CM, Sun YZ, Sun JM, Ma JQ, Cheng C. Protective role of quercetin against lead-induced inflammatory response in rat kidney through the ROS-mediated MAPKs and NF-κB pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:1693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyazaki K, Makino K, Iwadate E, Deguchi Y, Ishikawa F. Anthocyanins from purple sweet potato Ipomoea batatas cultivar Ayamurasaki suppress the development of atherosclerotic lesions and both enhancements of oxidative stress and soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:11485–92. doi: 10.1021/jf801876n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen CM, Li SC, Chen CY, Au HK, Shih CK, Hsu CY, et al. Constituents in purple sweet potato leaves inhibit in vitro angiogenesis with opposite effects ex vivo. Nutrition. 2011;27:1177–82. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vielma S, Virella G, Gorod AJ, Lopes-Virella MF. Chlamydophila pneumoniae infection of human aortic endothelial cells induces the expression of FC gamma receptor II (FcgammaRII) Clin Immunol. 2002;104:265–73. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang L, Tu YC, Lian TW, Hung JT, Yen JH, Wu MJ. Distinctive antioxidant and antiinflammatory effects of flavonols. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:9798–804. doi: 10.1021/jf0620719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen YH, Lin SJ, Chen YL, Liu PL, Chen JW. Anti-inflammatory effects of different drugs/agents with antioxidant property on endothelial expression of adhesion molecules. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2006;6:279–304. doi: 10.2174/187152906779010737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen YH, Lin SJ, Chen JW, Ku HH, Chen YL. Magnolol attenuates VCAM-1 expression in vitro in TNF-alpha-treated human aortic endothelial cells and in vivo in the aorta of cholesterol-fed rabbits. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:37–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lotito SB, Zhang WJ, Yang CS, Crozier A, Frei B. Metabolic conversion of dietary flavonoids alters their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:454–63. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCrohon JA, Jessup W, Handelsman DJ, Celermajer DS. Androgen exposure increases human monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelium and endothelial cell expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Circulation. 1999;99:2317–22. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.17.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Min YD, Choi CH, Bark H, Son HY, Park HH, Lee S, et al. Quercetin inhibits expression of inflammatory cytokines through attenuation of NF-kappaB and p38 MAPK in HMC-1 human mast cell line. Inflamm Res. 2007;56:210–5. doi: 10.1007/s00011-007-6172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferran C, Stroka DM, Badrichani AZ, Cooper JT, Wrighton CJ, Soares M, et al. A20 inhibits NF-kappaB activation in endothelial cells without sensitizing to tumor necrosis factor-mediated apoptosis. Blood. 1998;91:2249–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]