Abstract

In order to metastasize away from the primary tumor site and migrate into adjacent tissues, cancer cells will stimulate cellular motility through the regulation of their cytoskeletal structures. Through the coordinated polymerization of actin filaments, these cells will control the geometry of distinct structures, namely lamella, lamellipodia and filopodia, as well as the more recently characterized invadopodia. Because actin binding proteins play fundamental functions in regulating the dynamics of actin polymerization, they have been at the forefront of cancer research. This review focuses on a subset of actin binding proteins involved in the regulation of these cellular structures and protrusions, and presents some general principles summarizing how these proteins may remodel the structure of actin. The main body of this review aims to provide new insights into how the expression of these actin binding proteins is regulated during carcinogenesis and highlights new mechanisms that may be initiated by the metastatic cells to induce aberrant expression of such proteins.

Keywords: actin, Arp2/3, WASP, fascin, tropomyosin, miRNAs, ZBP1, cancer

Introduction

Cellular migration is an essential feature of life that is responsible for numerous physiological processes including accurate embryogenesis and wound healing. In some cases, however, the pathways regulating cell motility can also be used for aberrant purposes such as the dissemination of tumor cells away from their primary site of growth. While formation of neoplasms is by itself an important concern for human health, the steps that lead to invasion of other tissues by the primary tumor cells, a term referred to as metastasis, is much more life threatening. Indeed this dissemination of cells, resulting in the formation of secondary tumors in other organs, accounts for more than 90% of the fatalities associated with cancer progression. Although we have made remarkable steps toward understanding some aspects of the metastasis process, much still remains to be learned. Some of the key questions which will need to be addressed in the future should focus on understanding the cellular mechanisms that favor (1) the actual migration of cancer cells out of the primary tumor and (2) how they can successfully enter, survive and then leave the blood and/or lymphatic circulations (intravasation and extravasation, respectively) in order to generate secondary tumors in other specific tissues and organs of the body.

In the majority of carcinoma cases, the initial cellular events required to encourage metastasis are triggered by a switch from an epithelial cellular type to a less differentiated mesenchymal one, a process known as the epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT).1-3 During this transition, cells will sever links with neighboring cells. The loss of expression of the E-cadherin is seen as a hallmark toward such commitment.4,5 This downregulation of E-cadherin is regulated by specific transcriptional repressors such as those of the Snail family.6,7 Another important step seen during carcinogenesis will result in changes in cellular migratory properties. Increased motility will encourage cells to move away from their initial niche and invade surrounding tissues. This migration can take place as a single cell (sometimes referred to as mesenchymal or amoeboid migration) or as a collective effort in cell sheets or clusters.8 In both cases, the remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton is seen as a central step and significant alterations will take place at the cellular level. At the molecular levels, changes in the dynamics of actin polymerization just under the plasma membrane will be the core process leading to these biological consequences. Pushing forces will be generated either directly or indirectly by the assembly of F-actin filaments and these forces will promote the formation of different protrusions at the leading edge, namely lamellipodia, filopodia, invadopodia and blebbing, all playing key roles in cellular migration, albeit under different circumstances.9

Over the years, attention has been focused on identifying new cytoskeletal markers that demonstrate a good correlation between their expression and the degree of malignancy attained by tumor cells. Such candidate markers would have the potential to become invaluable tools to help comprehend better the stages involved in cancer biology, as well as providing powerful tools to improve both cancer prognosis and treatment. Different actin binding proteins have come to the fore and have been the focus of recent comprehensive reviews.10-12 The work presented here focuses only on a subset of known actin binding proteins, namely the Arp2/3 (Actin related protein 2 and 3 complex) and WASP/WAVE (Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein/WASP and Verprolin homologous protein) complexes, fascin and the tropomyosins all involved at different levels in the regulation of lamellipodium, filopodium, lamellum and possibly blebbing, and whose expression is aberrantly regulated during carcinogenesis. This review analyzes the recent developments in the field aiming to propose mechanisms that may be utilized by the metastatic cells in order to control abnormal expression of these actin binding proteins. These new regulatory mechanisms, if proven to be determinant in carcinogenesis, may translate into potential new avenues of research and treatment in the future.

The Actin Cytoskeleton in Tumor Cell Migration

The process of cellular migration is engineered as a cyclic procedure composed of (1) extension of cellular leading edge in the forms of membrane sheet-like, finger-like or bleb-like protrusion resulting from actin polymerization in close proximity to the plasma membrane, (2) development of cell-extracellular contact points which may or may not be regulated by integrins and (3) generation of forces by the actomyosin network to drive the morphological and architectural reorganization that promotes cell movement. This review will focus mainly on specific actin binding proteins that promote extension of the leading edge and their involvement during cancer progression and metastasis, since other reviews summarizing the global mechanisms of cell motility have recently been published.9,13,14

Studies analyzing the migratory behavior of tumor cells have demonstrated the architectural organization of different actin-rich structures and molecules within, depending on the environment in which they grow. For instance, an environment that promotes sufficient mechanical contacts and loosely organized extracellular matrix (ECM) will encourage an amoeboid-type migration where cells adopt a characteristic rounded shape. This style of migration, which relies on the continuous formation of dynamic cellular membrane protrusions, results in rapid locomotion and is typically seen in leukocyte cell lineages15 but has also been observed in tumor cells.16 Amoeboid motility does not require integrin nor other molecular interaction with the ECM17 but relies on a continuous physical interaction and friction with the environment.18 Furthermore, although cortical actin polymerization plays a fundamental role in this type of three-dimensional (3D) migration, providing a support to stabilize the newly formed bleb bulging forward,19 the filaments do not directly generate the protruding forces necessary to push the plasma membrane, as seen during mesenchymal motility. Equally important is the role of the Rho-ROCK signaling pathway that regulates the contractile cortical actomyosin network.20 Indeed the generation of contraction forces by myosin II causes the membrane to delaminate from/or fracture the actin cortex resulting in the inflow of cytoplasm and increased pressure at the plasma membrane in the direction of movement, leading to the formation of membrane blebbing at the leading edge.16,21 Movements of actin and related binding proteins into the bleb, during the later stages of inflation or in the process of retraction result in the formation of a cage like structure.22 As the expansion of the bleb slows down, ezrin appears to be one of the first proteins, studied so far, to be recruited, followed rapidly by actin.22 The four actin binding proteins α-actinin, coronin, tropomyosin-4 and fimbrin are also observed to move rapidly into the newly form protrusion. In the final stage of the bleb retraction, recruitment of components of the contractility apparatus such as myosin regulatory light chain and tropomodulin occur, resulting in the assembly of discrete foci at the bleb rim.22 Importantly, none of the factors known to promote actin nucleation, such as Arp2/3 or mDia have been observed in the newly formed bleb, highlighting some uncertainties as to how actin polymerization is controlled and regulated.

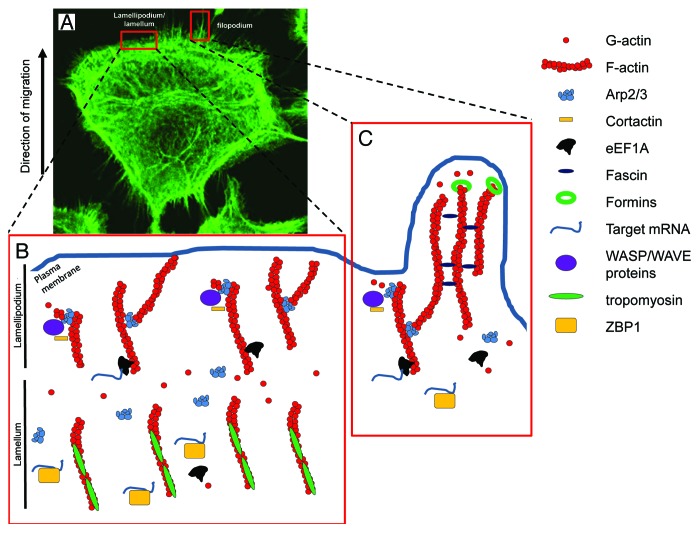

Mesenchymal motility, which is typically seen during fibroblast migration, result in cells presenting a more elongated spindle-like shape, and orchestrating the modeling of different cellular organelles. Growth on two-dimensional (2D) structures encourages cells to promote planar filamentous actin (F-actin) arrays known as filopodia/microvilli or sheet-like organization identified as lamellipodia (Fig. 1). Both of these structures rely on the controlled growth of the F-actin at their barbed end, leading to elongation of the filaments in the direction of the cell membrane. The overall morphology and molecular composition of these organelles determine their cellular importance. Lamellipodia are seen as the main driving force for locomotion and result from the large agglomeration of short branched filaments at the leading edge. The still increasing number of actin binding partners involved coordinate the nucleation of actin filaments (formins, Arp2/3/WASP complexes), their severing and depolymerization from the pointed end [gelsolin, ADF (actin depolymerization factor)-cofilin] and the control of capping of the F-actin filaments [VASP (vasodilator stimulated phosphoprotein), capping proteins, Arp2/3 complex].9,10 Contractile forces generated by myosin II activity are also required for stable lamellipodia extension and organization, acting at the back of the lamellipodium and facilitating both actin filament disassembly at this location23 as well as generating sufficient tensions to encourage focal adhesion maturation and stabilization through the interactions of contact points with the substratum. Filopodia, on the other hand, are believed to act as sensory and guidance organelles, probing the external environment for cues. Reflecting the idea of a “probing stick or antenna,” they are rod-like extensions made of 10–30 tight bundles of long actin filaments.24 Both formins and fascin have been shown to be major contributors in actin polymerisation in filopodia while both cdc42 and other Rho GTPase proteins are important to initiate the formation of filopodia.12,24

Figure 1. Actin organization in migrating cancer cell. (A) Staining for F-actin using Phalloidin-Alexa488 in a migrating Rama 37 malignant cell expressing high levels of S100A4. In this image, the structures of lamellipodium/lamellum and filopodium are clearly visible at the leading edge of the cell. (B and C) present models for the lamellipodium/lamellum and filopodium and the respective molecular organization within, focusing on the proteins presented in this review. (B) A simplified model for lamellipodium/lamellum formation. In the lamellipodium, free barbed ends of actin filaments recruit the Arp2/3 complex via activation by WASP/WAVE complex and cortactin. The Arp2/3 complex nucleates a new actin filament from the side of existing filaments and remains at the branching point. In the lamellum, actin filaments are bound to tropomyosins, preventing interactions with other actin binding proteins. (C) A simplified model for filopodia formation. Individual filaments of the filopodium emerge from the branching point on other filaments, through actin polymerization promoted by the Arp2/3 complex. Further addition of actin monomers at the barbed end of actin filaments is nucleated by the formin family, whereas fascin regulates filopodia stability through its bundling activities.

However in a thick 3D ECM, and therefore a more in vivo environment, mesenchymal migration is dependent upon some significant proteolytic digestion of the ECM,25 a characteristic seen when cells develop a ventral membrane protruding a highly dynamic actin-rich structure with ECM degradation activity. These structures are known as invadopodia. These protrusions can be observed on the lateral side of invading cells, as well as at the front and also at the base and branching sites of invading structures.25,26 In a high proportion of cases, it seems that formation of invadopodia is a prerequisite for cellular invasion and has been observed for numerous cancer cell lines that are capable of invading in vitro assay systems or in animal xenograft models.27 Although a clear case for the importance of invadopodia in invasion in vivo is still ill defined, circumstantial evidence has highlighted the importance of invadopodia associated proteins in metastasis promotion.28 For instance, using a xenograft model and through knockdown of N-WASP (Neural-Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein), Gligorijevic et al.29 were able to demonstrate that inhibiting formation of invadopodium in vitro correlated with a loss of invasion, intravasation and lung metastasis. Others have suggested that lamellipodia and invadopodia, two independent structures when studied in 2D conditions, may indeed merge into one invasive structure, located at the cellular leading edge and be capable of multiple rounds of protrusion and retraction, when cells are cultured in a 3D matrix and in conditions in vivo.30

The molecular mechanisms underlying the formation of the structures involved in mesenchymal migration are still being characterized, but common factors have now been demonstrated to be involved in both sets of protrusions. Actin polymerization is driven by the Arp2/3 complex and its nucleation-promoting factor N-WASP or WASP have been shown to be essential components of both invadopodia and lamellipodia/filopodia.31-33 Recently, the well characterized actin bundling factor fascin, which is known to play a key role in promoting the protrusion of filopodia, has also been characterized as an essential component of invadopodia formation.34 Finally, the tropomyosin family of proteins is thought to play important parts in both the amoeboid and mesenchymal-type migrations having been observed in both blebbing protrusions22 and regulating lamellipodia and filopodia,35 respectively. Each of these components will now be discussed, in terms of their biological functions toward actin polymerization, reviewing also their aberrant expression during carcinogenesis and highlighting possible molecular mechanisms that the cancer cells will deploy to achieve such changes.

Arp2/3 and WASP/WAVE family

The Arp2/3 complex consisting of seven subunits (proteins ARPC1–5 and Arp2 and Arp3) polymerizes new actin filaments from the sides of existing filaments, forming 70° side-branched networks. Because of their similarity in structure to the monomeric actin molecules, it is thought that the Arp2 and Arp3 proteins cooperate to form an active dimer for nucleation of the newly branching filament.36 At the molecular level, it is thought that all seven subunits of the Arp2/3 complex play key roles in the binding of the complex to the actin mother filaments, but only the Arp2 and Arp3 subunits contribute to the initiation of the new daughter filament.37 Regulation of the activity of the Arp2/3 complex to bind actin filaments is controlled by cortactin, through its interaction with the Arp3 subunit38 or the WASP superfamily of proteins. This large family which is still in the process of being characterized, is currently composed of the WASPs (WASP and N-WASP) and SCAR/WAVEs partners (Suppressor of Cyclic AMP Receptor mutation and WASP and Verprolin homologous protein), is defined by a conserved C-terminal VCA domain. This domain is crucial for binding to the Arp2/3 complex and to the globular form of actin (G-actin), thereby recruiting all components to encourage new nucleation.37,39 The VCA domain is seen as the main regulatory element of WASP binding to the Arp2/3 complex and is tightly controlled by intra-molecular interactions that mask it away and prevent its interaction with other binding partners. This direct auto-inhibition is the main regulator of the Arp2/3 promoting activity and is therefore recognized by a plethora of pathways including Rho family GTPases, phosphoinositide lipids, Src Homology SH3 domain containing proteins, kinases and phosphatases.40 The N-terminal element of WASP family proteins is also seen as an important regulator of the biochemical activities of the VCA domains and is thought to be responsible for cellular localization, as well to control the association with ligands. Expressions of WASP and WAVE proteins and that of the Arp2/3 complex have been shown to be altered during oncogenesis41 and such aberrant regulation result in important changes in the overall architecture of the actin cytoskeleton, principally the lamellipodium.

Another cellular protrusion in the form of finger-like sensory and exploratory extensions which push the plasma membrane outward is the filopodia. This structure is primarily composed of parallel bundles of actin filaments (Fig. 1). Their formation is regulated by a growing number of proteins including the Arp2/3 complexes.42 While it was originally perceived that the Arp2/3 complex was not required for filopodia formation, because of the absence of such branched structures in the thin finger-like structure, new experiments suggest that the complex may have important roles in the initiation of such protrusions since individual filaments of the filopodium emanate from the branching point on other filaments found in the lamellipodium.43,44 The actin bundling protein fascin has unequivocally been demonstrated to be a key regulator of filopodia stability.

Fascin

The 55-kD monomeric globular protein fascin has been shown to cross-links actin filaments in vitro into unipolar and tightly packed bundles45 through two actin binding sites, located at the N- and C-terminal ends of the protein in what is thought to be two different β-trefoil domains.46,47 Humans express three forms of fascins, fascin-1 and fascin-2 showing the highest degree of homology, whereas fascin-3 has only a very low homology with the other two isoforms.48 Fascin-1 (termed from now on as fascin) is found ubiquitously expressed by mesenchymal tissues and in the nervous system, whereas fascin-2 and fascin-3 are much more precisely expressed in retinal photoreceptors and in testis, respectively.49 The role of fascin in the formation of filopodia has been a rapidly expanding field and has generated wide-ranging interests due to its involvement in cancer progression (see below). Recent investigations have shed new light onto the mechanism for its regulation. The Rac and Rho proteins have been shown to act upstream of fascin through the PAK1 pathway or the p-Lin-11/Isl-1/Mec-3 kinases, respectively,50,51 but the main body of work highlighting post-translational modification of fascin activities has been demonstrated through the regulation of protein kinase C (PKC). Specific phosphorylation of serine 39 within the N-terminal actin-binding domain by this kinase results in the loss of actin bundling by fascin,52,53 offering a possible mechanism to control fascin involvement in both physiological and disease states. The spatial localization of fascin at the leading edge of crawling cells is important for the assembly of filopodia and the actin bundles generated through its bundling action allow the binding of the myosin motors II and V.54 Recent work suggests that F-actin filaments bundled by fascin may be important for the regulation of Myosin X motor processivity in filopodia formation.55

While both the Arp2/3 complex, its regulator and fascin play essential functions in the control of actin polymerization and organization, resulting in leading edge extension at the front of a migratory cell, other similarly important mechanisms are also required to promote cellular motility. Thus F-actin filaments need to be anchored to the extracellular environment via the formation of focal complexes and adhesions13 and this change along with the remodeling of the actomyosin network generates tensile forces. It is the generation of such tensile forces by the myosin family of proteins that drives some of the morphological and architectural reorganizations that promote cell movement. The actomyosin contractile network represents a structural complex which is spatially posterior to the lamellipodium56 and is referred to as the lamellum. The biological mechanisms responsible for the segregation of these two cellular subdomains are not clearly understood. The tropomyosin family of proteins may be one of the factors responsible for such spatial discrimination since they regulate the recruitment of myosin motors to the actin filaments.57

Tropomyosin

The tropomyosins (tpms) are thought to be mainly absent from the dynamic Arp2/3 containing compartment,58 although such concepts have been recently challenged following the observations of tropomyosin isoforms in both the lamellipodia and filopodia of spreading normal and transformed cells.35 Originating from four distinct genes, there are today more than 40 tpms isoforms that have been discovered so far. More than 10 of these tpms isoforms are expressed from TPM1 (a-TM) and TPM2 (b-TM) genes alone in vertebrate and are classified further into high molecular (HMW) and low molecular weights (LMW) tpms. Tpms are rod-shaped coiled-coil dimers actin-binding proteins that bind along the length of the actin filaments and have been implicated in the assembly and stabilization of actin filaments.59 Some recent advances in the field indicate that the isoforms Tm1, Tm2/3 and Tm5NM1/2 are required for assembly of stress fibers in cultured osteosarcoma cells, stabilizing the actin filaments at distinct regions.60 Tpms have also been shown to prevent ADF-cofilin or gelsolin interaction with F-actin in vitro, regulating also their localization in the process, although such properties seem to be isoform-specific.61,62 For instance, the tropomyosin isoform Tm5NM1 promotes inactivation of ADF-cofilin and leads to its displacement from the cell periphery while another isoform, TmBr3 stimulates the association of ADF-cofilin with actin filaments, therefore promoting its localization at the leading edge.63 Interestingly, such properties also reflect the ability of these tropomyosin isoforms to recruit myosin II motors to the actin filaments with Tm5NM1 having a positive control over the binding of myosin II to F-actin filament whereas TmBr3 regulates its inactivity.63 These diverse regulatory functions correlate with differential changes in cell size and shape, along with alterations in lamellipodial formation, increased cellular migration, and reduced stress fibers.63

All in all, the cellular pathways promoting cellular motility are diverse and complex and, not surprisingly, we find that the paths to carcinogenesis are similarly varied and multiple, involving the aberrant expression of many different targets. In an effort to correlate protein expression to possible mechanisms involved in their regulation, and the biological consequences of their interactions in cellular migration, this reviews brings together some of the recent findings that have shed new light on such processes, tackling in the first instance how the levels of these specific actin binding proteins are changes in the cancer cell (Table 1).

Table 1. Regulation of specific actin binding proteins in cancer tissue samples and cell lines.

| Actin binding protein affected | Level of regulation and tumor origins | References |

|---|---|---|

| Arp2/3 | ||

| Arp2 | Down in gastric carcinoma | 64 |

| Up in gastric carcinoma | 70 | |

| Up in colorectal carcinoma | 65 and 73 | |

| Up in breast carcinoma | 71 and 72 | |

| Arp3 | Up in colorectal neoplasms | 65 |

| Up in gastric carcinoma | 70 | |

| ARPC1 | Up in pancreatic carcinoma | 119 |

| ARPC2 | Down in gastric carcinoma | 64 |

| Up in breast carcinoma | 66 | |

| ARPC3 | Down in gastric carcinoma | 64 |

| Up in breast cancer cell lines | 68 | |

| Up in PyMT tumor cells | 69 | |

| ARPC5 | Up in breast cancer cell lines | 68 |

| Up in PyMT tumor cells | 69 | |

| Up in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | 67 | |

| WASP/WAVE | ||

| N-WASP | Down in breast carcinoma | 83 |

| Up in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | 78 | |

| No changes in breast carcinoma | 82 | |

| WAVE1 | Up in breast carcinoma | 82 |

| WAVE 2 | No changes in breast carcinoma | 82 |

| Up in breast carcinoma | 79 | |

| WAVE3 | Up in prostate carcinoma | 81 |

| Fascin | Up in thymomas and thymic carcinomas | 85 |

| Up in endometrioid carcinoma | 86 | |

| Up in pancreatic adenocarcinoma | 87 | |

| Up in hepatocellular carcinoma | 88 | |

| Tropomyosin | ||

| Tpm1 | Down in breast cancer cell line | 96 |

| Down in colon cancer cell line | 96 | |

| Tpm3 | Up in breast cancer | 99 |

| Up in hepatocellular carcinoma | 103 | |

| ALK-TPM3 | Up in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors | 100 |

| Up in anaplastic large cell lymphoma | 101 | |

| TRK-TPM3 | Up in thyroid papillary carcinoma | 102 |

Regulation of Specific Actin Binding Proteins in Cancer Progression

Arp2/3 and WASP/WAVE family

The proteins of the Arp2/3 complex play essential orchestrating functions in actin organization. Their binding to already formed actin filaments, forming 70° side-branched networks, is crucial for the modeling of the lamellipodia. Reports have shown that the metastasis process correlates with changes in the expression pattern of components of the Arp2/3 complex, although some uncertainty remains as to the degree of correlation as discussed below.

Cancer progression of gastric cells appears to result in the robust and synchronous reduction in the expression of Arp2/3 proteins, with the reduction of at least four mRNAs of the seven subunits in more than 78% of the cases.64 Among all components analyzed, the Arp2, ARPC2 and ARPC3 mRNAs, as determined by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, were found to be the most prominently reduced in cancer samples compared with their control counterparts. However, some of the gastric cancer cells and tissues had been obtained from primary tumors and no information was provided regarding their metastatic abilities. Furthermore, the experiments measured only the mRNA contents for the different components of the complex without assessing how the correlating protein levels were affected. More recent work investigating the aberrant levels of Arp2/3 proteins in pancreatic, colorectal and breasts carcinomas highlighted the elevation of the complex’s proteins with the rise in invasiveness and metastatic abilities. Increased levels of both Arp2 and Arp3 proteins, measured by immunohistochemical staining correlated with the rise in atypical properties of the colorectal neoplasms.65 This aberrant change in expression is not exclusive to the Arp2 and Arp3 proteins as other components of the complex have also been shown to be affected during carcinogenesis. Expression pattern of the ARPC2 subunit has been reported to be increased in breast cancer cell lines.66 The latter study provides further support for the role of ARPC2 as a sole promoter of cellular invasion, since knockdown of its expression using siRNA was sufficient to attenuate SK-BR3 breast cancer cells incursion into Matrigel. Independently other components of the Arp2/3 complex have been shown to be equally important in the pathogenesis of the head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, when the expression of the ARPC5 subunit at both the mRNA level and protein level were significantly upregulated in malignant invasive cells and tissues compared with the control counterparts.67 These observations were further substantiated using human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma lines, that showed that high levels of ARPC5 expression resulted in both higher rates of cellular migration, cellular invasion and to a certain extent cellular proliferation. When ARPC5 levels were specifically downregulated in these cells, using siRNA, all these properties were significantly diminished when compared with the mock transfected control cells. Both results demonstrated the direct influence of ARPC5 on these pathways.

It is unclear why such contradictory patterns of expression have been observed between the different studies. Studies using immunohistochemical analysis as the only way to assess the levels of proteins may themselves have shortcomings, as they do not offer satisfying quantitative measurements of the real concentration and can further be influenced by the localization of the proteins. Furthermore, besides the potential explanation that the different results are related to the different origins of the samples and tissues, there is also the more pertinent possibility that levels of the Arp2/3 proteins may be upregulated at a specific time and/or indeed be critically required for the enhancement of invasive properties. Direct demonstrations using knockdown experiments above highlighted the importance of the expression of both ARPC5 and ARPC2 in enhancement of both cellular migration and invasion. It is therefore reasonable to suggest that invasive cells could gain an important selective advantage by aberrantly and timely upregulating the expression of such proteins, while other tumor cells that fail to modulate such control will remain in their original environment.

This suggestion is further supported by studies that aim to link directly the Arp2/3 complex and cell invasiveness. The subunits ARPC3 and ARPC5 have been shown to be expressed at high levels in the expression profiling of invasive subpopulations of MTLn3-derived or Polyoma Middle T oncogene (PyMT)-derived mammary tumor cells selected in vivo.68,69 In both instances, cells that demonstrated an ability to invade into adjacent tissues had upregulated the expression of the Arp2/3 complex components as well as molecules such as cofillin, to coordinate the activation of motility pathways.

Moreover some degree of correlation has now been reported between the increased expression of Arp2 proteins, Arp3 proteins, cortactin and fascin and the tumor depth of invasion in gastric carcinoma,70 or between components of the Arp2/3 complex and their activators, when significant upregulation of WAVE2 and Arp2 are reported in breast cancer samples71,72 and in colorectal carcinomas.73 Altogether, it is therefore tempting to speculate that although the expression of single components of the Arp2/3 complex may play an important role to promote cell migration away from the primary tumor, they may not in their own right be sufficient, and that concomitantly other actin binding proteins may also need to be specifically targeted.

The importance of WASP and WAVE in the regulation of cancer invasion has been the topic of excellent recent reviews12,41,74 and will only be briefly discussed here. WASP/WAVE family of proteins play key functions in the regulation of the activity of the Arp2/3 complex, acting via the VCA region, to act as a scaffold to promote interactions between the complex and actin.37 As a result, they are necessary for the cell protrusive activity that is associated with cell migration and invasion. While WASP proteins have been shown to be directly responsible for the formation of invadopodium in carcinoma cells,29 WAVE components appear to regulate formation of lamellipodia and membrane ruffles as well as that of filopodia.75-77 Reports have highlighted their possible implication with metastasis, as their expression encourages cells to migrate away from primary tumors. Thus recent work has shown that N-WASP activity is required for invadopodia in vivo and promotes some of the initial invasive steps of metastasis.29 Not surprisingly protein levels of N-WASP have been shown to be increased in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. This increase has been correlated with lymph node metastasis and pathological staging.78 Similarly, WAVE proteins have also been found to be elevated in different cancer tissues. Thus a correlation between elevated levels of WAVE3 and advances in breast cancer progression has been highlighted.79 Furthermore when WAVE3 is downregulated using siRNA in MDAMB231 cells, the resultant cells show an inhibition in cell motility and invasion, suggesting that WAVE3 may be a significant element in tumor cell migration.80 Similar observations were made following immunohistochemical staining for WAVE3 in prostate tumor sections or prostatic cancer PC-3 and DU-145 cell lines.81 Once again, reducing WAVE3 to the more basal levels of non-tumorigenic cells led to a much reduced invasiveness, as quantified through cell penetration of the basement membrane, without affecting growth or matrix adhesion. In parallel WAVE2 transcription (mRNA and proteins) was reported to be at high levels in node-positive cases as well as in moderately and poorly differentiated breast tumors and it correlated with a poor prognosis.82

The story is, however, not as clear cut as first thought, since more recent reports have now also indicated that low expressions of N-WASP or WAVE can also reflect a poor outcome. For instance N-WASP has been reported to act as a tumor suppressor gene both in vitro and in vivo using human breast cancer cell lines and tissues.83 Both protein and mRNA levels, determined by immunohistochemical staining/western blots analysis and quantitative PCR, respectively, on freshly collected breast tissues, revealed that cancer tissues presented much lower levels of expression of N-WASP than their control counterparts and that ectopic overexpression of N-WASP could significantly reduce motility and invasiveness of MDAMB231 cells in vitro, as well as reduced tumor growth in animals. However the ability of N-WASP overexpressing MDAMB231 cells to form secondary tumors and metastasis was never tested in this work, providing no further details as to the potential invasive properties of this protein. The same group reported that WAVE1 and WAVE3 transcripts were not increased in node-positive cases, as well as in moderately and poorly differentiated breast tumors.82

Fascin

Numerous reports link fascin to cancer progression. Importantly, fascin expression has now been reported to be associated with invasion of epithelial tumor cells and clinically aggressive tumors (see references herein and recent reviews48,84). Fascin expression, revealed by immunohistochemical staining, suggests that this protein is increased in dendritic cells and tumor epithelia in thymomas and thymic carcinomas,85 as well as in endometrioid carcinoma,86 pancreatic adenocarcinoma87 and hepatocellular carcinoma.88 In the latter work, cortactin expression was also upregulated along with that of fascin. The increased expression of fascin during cancer pathogenesis is not merely coincidental since when expression of fascin is induced using plasmid transfection in pancreatic tumor cells89 or oral squamous cell carcinoma90 motility and invasion of the transfected cells are increased. This upregulation of fascin was mirrored by important increases in F-actin-based structures like filopodia and lamellipodia. The inverse experiment, where levels of fascin are downregulated, also provides evidences of it playing a key role in invasion. Thus when fascin levels are depleted in melanoma CHL1 cells or MDAMB231 breast adenocarcinoma cells by siRNA the resultant cells showed a reduction in invadopodia.34 The mechanisms responsible for the promotion of invasion by fascin are still not fully understood but essential elements have recently been provided. It appears that the actin bundling properties of fascin are key for formation of invadopodia since expressing a form of the protein that has lost its actin bundling activities, following knockdown of the endogenous protein, failed to restore such migratory characteristics in CHL-1 or A375MM cells.34

Tropomyosin

Because of their important role in actin organization and anchorage-independent growth, tropomyosins (tpms) have been classified as tumor suppressors.91 Reduced levels of both tpm1 and tpm2 have been reported in tumorigenic cells thus highlighting their roles as core components of cell transformation.92,93 More recent work also indicates that reduction or loss of tropomyosin correlate with tumors that invade and/or metastasise in breast, prostate, bladder and colon cancer, possibly through its regulatory function on the assembly of stress fibers.94-96 Thus for example a marked reduction in tpm1 was found in metastatic breast MDAMB231 and colon SW620 cancer cell lines.96 Moreover when tpm1 was overexpressed in MDAMB231 cells, the level of stress fibers formation was increased and this correlated with a reduction in actin ruffles at the leading edges and a loss of cell motility.96 Similarly, Tm5NM1, a low molecular weight isoform from the TPM3 gene, inhibits both the mesenchymal to amoeboid and amoeboid to mesenchymal cell transitions, as a result of stabilization of actin filaments and inhibition of cell migration in a 2D culture system.97 Logically when Tm5NM1 was reduced the resultant cells were seen to increase significantly directional persistence, presumably through a greater formation of focal complexes.98 From this information, it is probable that progression to metastasis by certain primary tumors may require the downregulation of specific tpms but reports providing such information are, to the best of my knowledge, not currently available. In fact most of the information linking tropomyosins proteins to carcinogenesis presents them as potential promoters of cellular invasions. Thus tpm3 has been shown to be highly expressed in malignant breast tumor cells found in lymph nodes.99 Furthermore, chromosomal translocation of the tpm3 gene to other DNA regions has also been reported to lead to carcinogenesis. Thus examples of the fusion of the tpm3 gene to the anaplastic lymphoma kinase ALK gene, resulting in the chimera TPM3-ALK has been linked to inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors100 and anaplastic large cell lymphoma,101 whereas fusion of the tpm3 gene to the TRK kinase gene leads to human thyroid papillary carcinoma.102 In all these cases, a direct role for tpm3 as an oncogene has always been in question since it could potentially act indirectly by promoting dimerization/multimerization which would be sufficient to lead to activation of the associated kinase protein. A recent report however, demonstrates the presence of elevated levels of both tpm3 mRNA and protein in human hepatocellular carcinoma when compared with the adjacent non-tumor liver tissue.103 A significant correlation was also seen between elevated tpm3 levels and poor recurrence-free survival.103 Much remains to be learned about the role of tpm3 during tumorigenesis, since it is currently unclear if tpm3 is solely responsible for all of the observations reported or happens to be a coincidental partner expressed during cancer progression.

All in all, the roles of the different actin binding proteins listed here in carcinogenesis have been studied for many years, but uncertainties remain as to how they are involved and their biological consequences. The challenge now is to comprehend, at the cellular level, how different mechanisms may be diverted toward a single goal. Thus studies that concentrated on the expression of a solitary protein may therefore have been blinded from others changes that had taken place. A more globalistic approach that has been embraced over the last few years to monitor changes in cancer cell progression will in turn provide a much greater understanding of the different regulatory events responsible for the occurrence of metastasis. The ramifications of such comprehension may lead us to identify overlapping regulatory pathways that may be affected by cancer cells to alter the expression of specific proteins.

Possible Mechanisms Hijacked by Cancer Cells to Regulate the Expression of Actin Binding Proteins

A plethora of work has now highlighted the differential expression of actin binding proteins during carcinogenesis and acquirement of the metastatic state. It is, however, unclear as to how these protein levels are controlled both in terms of their global cytoplasmic expression and specific subcellular localization. Indeed, comparative genomic vs. proteomic studies have indicated that mRNA expression is not always a good predictor of the changes in protein levels in eukaryotes.104 Therefore different mechanisms acting post-transcriptionally may have been established to control gene expression and to regulate the levels of cellular proteins and these will be discussed in regards to the specific actin binding proteins that have been linked to cancer progression.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs or miR) are a class of naturally occurring small (20–25 nucleotides) non-coding RNA molecules that have been shown to have critical roles in the regulation of gene expression, resulting in important control of biological and metabolic processes such as cell growth, differentiation, cell maintenance and cancer.105,106 The precursor miRNAs are initially transcribed by RNA polymerase II and further processed by RNase III Dorsha and DGCR8. They are then exported by exportin 5 to the cytoplasm, where they will be converted into an active form by Dicer. Their post-transcriptional functions are exerted through the complementary binding of 3′-UTR (untranslated region) of target mRNAs, resulting in either their degradations or their blocks in translation.107 Numerous lines of evidence indicate that miRNAs also play vital functions in tumorigenesis and their expressions is aberrantly regulated in several types of human cancers.106 Certain miRNAs such as miR-373 and miR-520c have been classified as metastasis-promoting factors108,109 while others play a role in inhibiting tumor invasion and metastasis. Indeed numerous studies have reported that miR-145, miR-143 and miR-133a/b play a tumor-suppressive role in various cancers and are consequently downregulated in the miRNA expression signatures of various human malignancies.110-114 Their regulation has highlighted their importance in controlling specifically the levels of different actin binding proteins and hence they are discussed here (Table 2).

Table 2. miRNAs dependent mechanisms regulating the levels of specific actin binding proteins in different cancer samples and cell lines.

| Actin binding protein affected | Possible miRNA mechanisms | Tumour origin | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arp2/3 | |||

| ARPC5 | miR-133a | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | 67 |

| WASP/WAVE | |||

| WAVE3 | miR31 | Breast cancer cell lines | 121 |

| Prostate cancer cell line | 121 | ||

| miR-200 | Breast cancer cell line | 120 | |

| Prostate cancer cell lines | 120 | ||

| Tropomyosin | |||

| Tpm1 | miR-21 | Breast cancer cell lines | 129 and 130 |

| Tpm2 | miR-133a | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | 67 |

| Tpm3 | miR-133a | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | 67 |

| miR-145 | Prostate cancer cell lines | 111 | |

| Esophageal squamous cancer carcinoma | 112 | ||

| Fascin | miR-133a | Bladder cancer cell lines | 113 |

| miR-143 | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | 126 | |

| miR-145 | Breast cancer cell lines. | 128 | |

| Prostate cancer cell lines | 111 | ||

| Bladder cancer cells lines | 113 | ||

| Esophageal squamous cancer cell lines | 126 |

Arp2/3 and WASP/WAVE family

Studies of the Arp2/3 complex and its binding partners have significantly improved our understanding of the mechanisms that are in place in cells to modulate their actin polymerization activities. Work presented so far in this review also reveals that protein levels of the Arp2/3 complex are seen to be elevated during tumorigenesis in the great majority of cancers studied, but much remains to be discovered to explain how such increases are attained. A few new perspectives have now been put forward. Using head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells and a genome wide gene expression analysis, Kinoshita et al. have now demonstrated that mRNA for the subunit ARPC5 is a target for miR-133a.67 While ARPC5 is seen as a marker of invasion and is significantly overexpressed in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, silencing its expression by siRNA led to reduced migration and invasiveness. Interestingly, enhanced expression of miR-133a specifically downregulated levels of ARPC5 and also reverted the invasion and motility of the cells to a more wild-type phenotype. Recent data has revealed that miR-133a functions as a tumor suppressor and its downregulation plays a critical part during the progression of different tumors of the bladder or esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.115 It is therefore tempting to speculate that such increase in tumorigenesis may in fact be linked to the enhanced expression of ARPC5 thereby causing an increase in invasiveness.

Other miRNAs have also been reported to downregulate specifically the expression of other subunits of the Arp2/3 complex, albeit not in tumor cells. ARPC3 has been identified as a target for miR-29a and miR-29b in primary hippocampal neurons and mouse N2A cells,116 whereas miR-129-3p specifically reduces the level of Arp2 in human retinal pigment epithelial cells.117 Although there is currently no information linking miR-29a and miR-29b in the progression of cancer, levels of miR-129-3p are affected by DNA hypermethylation in primary gastric cancers, resulting in reduced expression and correlating to poor clinic-pathological features.118 Direct connections have yet to be made between expression of miR-129-3p and Arp2 levels in cancer cells and tissues, but these connections highlight another possible regulatory mechanism that cells could initiate en route to full carcinogenesis. More work in this field is therefore required to establish new links between these observations and the importance of Arp2/3 in metastasis.

One needs to be mindful that posttranscriptional regulation of the expression of certain subunits of the Arp2/3 complex is not necessarily the only method to achieve such elevated levels. Other mechanisms are also being put forward to explain this phenomenon. Possible mechanisms for the overexpression of subunits of the Arp2/3 complex may also be linked to amplification of specific DNA target genes. Indeed, fluorescent in situ hybridization of pancreatic cancer cell lines and primary tumors has revealed an increase in copy number of an amplicon core region containing the ARPC1A gene, this demonstrates a significant correlation between amplification and elevated levels of expression of ARPC1A.119

Although much remains to be discovered regarding the regulatory mechanisms that govern the expression of the family of WASP proteins in tumorigenesis, some recent findings are starting to shed light on this process. As we have seen, correlation between expression levels of WAVE3 and breast cancer progression have been highlighted, indicating that this protein may act as a key inducer of metastasis. A link between its expression and that of specific miRNAs, miR-31 and miR-200 have now also been recently documented.120,121 Thus an inverse correlation between expression of WAVE3 and that of either miR-31a or miR-200 has been reported with WAVE3 levels increasing as cells underwent EMT while both miR-31 and miR-200 levels were found to be reduced. These observations were seen to be more than mere coincidence since miR-31 and miR-200 were shown to target specifically a portion of the 3′-UTR of WAVE3 mRNA, and this resulted in a significant reduction of both its mRNA and protein, whereas its targeting had no effect on either WAVE1 or WAVE2 mRNAs. This initial descriptive observation will need to be characterized further to identify whether such regulation helps to trigger the progression of a tumor in to a more malignant state.

Fascin

As previously discussed, clear evidence has now demonstrated that elevated level of fascin is associated with poor prognosis and corresponds to changes in various tumors to more aggressive phenotypes (Table 1). Interestingly, increases in expression may be tightly linked to the process of metastasis, at least in human colon carcinomas, since levels of fascin appear to return to more basal levels once cells reach their destination where migration ceases and proliferation is enhanced.122 Recent work has therefore been aimed at understanding how the elevated expression of fascin is regulated in such a precise and clockwork-like manner when it is required most, since experiments have shown that enhanced expression of fascin is solely capable of inducing cellular migration in vitro using colonic non-invasive carcinoma lines.123 The regulatory mechanisms that could explain such observation are still currently lacking, although activation of pathways involving insulin growth factor -1 (IGF-1) or tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) have been shown to upregulate specifically the expression of fascin in breast and bile duct carcinomas;124,125 however the direct mechanisms need to be identified in greater depths. Alternatively, recent reports over the last few years have established a link between fascin expression and that of specific miRNAs, mainly miR-133a/b, miR-143 and miR-145 in prostate, bladder, esophageal squamous and in breast cancer cells.111-113,126,127 Interestingly, most of these miRNAs have also now been shown to be specifically regulated in carcinogenesis110-114 (see earlier comments). Indeed the miR-145 cluster is located in 5q33, a region of the genome that has been shown to be frequently altered in cancers cells through chromosomal deletions, epigenetic changes and aberrant transcription. Experiments using the MDAMB231 breast cancer cell line have further directly implicated the role of miR-145, since overexpression of miR-145 was shown to reduce dramatically the levels of fascin protein and coincidentally led to much reduced cellular invasion capabilities.128 The inverse experiment also demonstrated that when miR-145 levels were lowered, using specific anti miR-145 oligonucleotides, invasive abilities were enhanced in less invasive breast tumor T47D cell lines.128 These properties of miR-145 do not appear to be breast specific since similar work link it to fascin expression and invasion in the DU145/PC3 prostate cancer cell models111 or bladder cancer cell lines.113 The list of newly characterized miRNAs that can specifically target fascin is likely to rise in the future as recent reports demonstrate that miR-143 and miR-133a can similarly reduce its levels.113,126 It remains to be elucidated however how exactly this process occurs and the biological relevance of such observations. For example is this suppressive effect directly due to the reduction in stability of fascin mRNA111-113 or linked to the translation regulatory mechanisms that prevent the recruitments of its mRNA to the ribosomes?

Tropomyosins

Recently, independent experiments aiming to identify new target genes for miR-145, using comprehensive gene expression analysis, have implicated miR-145 as a regulator of tpm3 levels, downregulating its expression in esophageal squamous cancer cells and prostate cancer cells.111,112 Similarly, tpm3 (as well as tpm2) were identified as target mRNAs controlled by miR-133a in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.67 In all these cases however, such observations were not the direct focus of the investigations. Because these miRNAs are known tumor suppressors, downregulation of the tpm3 isoforms could possibly be a mechanism of such suppression. Establishing the true oncogenic nature of tpm3 and whether a direct connection occurs between its expression and that of specific miR-133a and miR-145 should certainly provide a focus of future work.

The link between miRNAs and tropomyosins also appears to involve other members of their respective families. Indeed gene repressing regulatory functions for miR-21 have also been shown toward tmp1 in MCF-7 and MDAMB231 cells.129,130 These breast cancer cell lines express high levels of miR-21 and coincidentally low levels of tpm1, one of the potential factors that could explain some of their malignant properties. When levels of miR-21 were reduced in both of these cell lines they expressed high levels of tpm1, and sole expression of myc-tagged tpm1, by transfection of an expression vector, in the MDAMB231 cells was sufficient to reduce invasive capacity.129 Interestingly, such regulations of tpm1 levels was shown to be exerted at the translational level, presumably through inhibition of the recruitments of tpm1mRNA to the ribosomes since its mRNA levels were unchanged.130 Links have therefore now been initiated between tropomyosin isoforms and their regulation post-transcriptionally through specific miRNAs. This avenue of research is in its infancy, since such observations are currently mainly coincidental but they may prove to be biologically relevant and possibly key in the route to metastasis.

Regulation of expression of specific actin binding proteins through localization of their mRNAs at the leading edges of migratory cells

Work in different organisms has now clearly demonstrated the importance of mRNA localization of target proteins to the protein’s sites of function and their translation in situ. Thus localization of β-actin mRNA near the cellular leading edge promotes cell motility131 since its delocalization leads to a random distribution of the protein, as well as casual spatial arrangement of the barbed end filaments and their nucleation sites.132 Recent work has also indicated that localizing actin mRNA at the leading edge is not a sole requirement since mRNAs encoding core components of both the lamellipodium and focal adhesions may also be selectively targeted to this region. Indeed, through the use of both fluorescent in situ hybridization and tyramide-signal amplification, mRNAs for the seven members of the Arp2/3 complex were found to be localized to protrusions in fibroblast cells.133 As for the displacement of the β-actin mRNAs to non-physiological subcellular regions, recent work has shown that preventing the proper localization of the Arp2 mRNA to the leading edge leads to narrow cellular protrusions and loss of directionality.134

Similarly, localization of α-actinin mRNAs to the leading edge has been shown to be critical for the proper regulation of the assembly of focal adhesion sites and migration.135 Experiments looking at mRNA localization in highly invasive MDAMB231 cells have shown that α-actinin mRNA levels are remarkably low at the leading edge, presumably correlating with low amount of proteins, this low level results in small and largely un-matured focal adhesions.135 Moreover when the localization of α-actinin mRNAs at actin-rich cellular protrusion was elevated, through the increased expression of the zipcode binding protein 1 (ZBP1, discussed further below), increased size and greater levels of mature focal adhesions were produced, suggesting a link between mRNA spatial organization of α-actinin and assembly of focal adhesions.

It is therefore conceivable that proteins whose function is to target specific mRNAs to precise regions in cells could therefore “indirectly” regulate the direct functions of such proteins. One such factor is ZBP1, a primarily cytoplasmic 68 kDa protein, which contains several recognizable regions, including two RNA-recognition motifs, four hnRNP K homology domains, as well as potential nuclear localization and export signals.136 ZBP1 binds to specific mRNAs through the recognition of cis-acting elements usually found in the 3′-UTR136 (and reviewed in ref. 137). mRNAs for components of the Arp2/3 complex and α−actinin have been shown to bind to ZBP1 proteins in MTLn3 breast cancer cells in microarray experiments.138 High expression of ZBP1 results in the localization of their mRNAs at the cell leading edge and as a result is directly implicated in decreased turnover of focal adhesions.135 This in turn leads to loss of the metastatic potential of a cell line derived from breast tumors.68 Conversely, when ZBP1 expression is repressed, this change not only increases cell migration, but also promotes the proliferation of metastatic cells.138 Coincidentally, or possibly strikingly, it appears that the same cells that boost the levels of the Arp2/3 complex proteins are also the ones that reduce the amount of ZBP1 on their route to metastasis.68,69 All together these reports indicate that the steps when ZBP1 is downregulated and the expression of specific actin binding proteins is simultaneously increased may be critical in metastatic progression. This step could control both structural regulation of the leading edge and cell polarity along with assembly of focal adhesions and their stability by spatially regulating the translation of both the mRNAs discussed as well as others potentially relevant to motility. To support this theory, a significant decrease in transcription activity of the ZBP1 gene has been observed in cells from metastatic tissues through methylation of its promoter region. Such changes have resulted in a dramatically silenced expression of ZBP1 in highly invasive cells (MTLn3 and MDAMB231) compared with non-invasive cells.138 The route to metastasis is a twisted, not necessarily unique path, that will be achieved through a series of regulatory events. It is therefore conceivable to speculate here that different mechanisms, working synergistically, will be at play to accomplish a common goal. Regulating the expression of specific actin binding proteins such as those of the Arp2/3 complex, along with that of ZBP1 may be key for such progression and future work may focus on analyzing their levels in cancerous tissues and samples.

While there is little doubt that transport of specific mRNAs to the leading edge will play essential roles in regulating the expression of factors involved in lamellipodia, filopodia and invadopodia, it is still uncertain as to how these targeted mRNAs will be retained at the correct subcellular site. Although the role of ZBP1 or other carrier is critical for the transport of the actin binding proteins, they do not by themselves interact directly with structures that would allow their accumulation and anchoring at specific sites. Although no factors have so far been reported for the mRNAs of either components of the Arp2/3 complex or α-actinin, β-actin mRNA has been shown to be anchored onto actin filament by the eukaryotic elongation factor 1 α (eEF1A).139

eEF1A, whose primary function is the delivery of amino-acyl tRNAs to the elongating chain of the newly synthesized protein of the ribosome has also been reported to have numerous other non-canonical functions; one of these functions is the remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton which occurs throughout eukaryotes.139-141 Both mammalian isoforms, eEF1A1 and eEF1A2 have been reported to be important in carcinogenesis although not necessarily for the same reason.142,143 eEF1A2 has been shown to promote the formation of filopodia through the generation of phosphatidylinositol-4,5 biphosphate in both the cytosolic and membrane bound cellular compartments,144 a regulatory mechanism that appears to play an important role in acinar development and mammary neoplasia.145 A direct connection between tumorigenesis and eEF1A1 remains elusive, but could be linked to its ability to interact with the actin cytoskeleton,142 through regulation of the Sphingosine kinase 1146 or intracellular alkalinization-induced tumor cell growth.147 It appears, however, that increased expression of eEF1A can lead to transformed phenotypes.148 More recently, the levels of expression of eEF1A1 and its role during cancer progression has led to further uncertainty. Some observations demonstrate increased eEF1A1 levels as single cells acquire metastatic properties in primary mammary tumors149 but eEF1A1 levels were subsequently found to be significantly decreased in an invasive subpopulation of Polyoma Middle T oncogene (PyMT)-derived mammary tumors, to a level similar to that of ZBP1.69 Further work on the eEF1A protein is therefore required to shed more lights onto the potential oncogenic properties of this factor and whether its ability to spatially organize mRNAs for actin and for potential other target proteins that have hitherto not yet been identified plays some role in the metastatic process.

Concluding Remarks

The route to carcinogenesis is a lengthy and time-consuming process, as is the road that scientists have been following in order to make sense of it all. In a mass of tumor cells, some cells will regulate concurrently the expression of many different proteins, this is a key step required to acquire more invasive properties, thereby allowing cells to infiltrate adjacent tissues. Indeed, the penetration of the basal membrane, and the surrounding structures of this physical barrier is seen as one of the most significant characteristics of malignancy. Yet it is also one of the most challenging aspects of the cancer pathology to recapitulate in vitro since cell invasion requires dynamic interaction between the tumor cells, especially when considering collective migration, host cells from neighboring and distant tissues to be invaded and the basal membrane matrix itself. Recent advances, using elegant ex vivo or in vivo techniques, such as the rat peritoneal basal membrane33 or chick chorioallantoic membrane150 invasion assays, respectively, have generated new avenues of research that will provide further insights in to the different steps of invasion and will allow identification of more of the important players in this process. A subset of actin binding proteins, some of which have been presented in this work, have now advanced as hallmarks for carcinogenesis and some possible mechanisms for their regulations have also been reviewed. More in depth studies on the importance of miRNAs and on localized regulation of protein expression will be needed to provide a more complete picture of the mechanisms that facilitate cellular invasion. In turn, the potentially newly-characterized factors involved in this process may prove to be targets that will allow us to understand their full potential in tumor progression.

Acknowledgments

I would like to apologize for the numerous studies, which have significantly improved our understanding of metastasis and cancer invasion, but could not be included in this work owing to journal limits on the number of references. Special thanks are given to Prof. Philip S. Rudland, the University of Liverpool, for his critical comments on the manuscript. This work was partly supported by a Biomedical Science grant from Aston University.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ADF

actin depolymerizing factor

- Arp2/3 complex

actin related protein 2 and 3 complex

- ARPC

actin related protein complex subunit

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- eEF1A

eukaryotic elongation factor 1 α

- EMT

epithelial mesenchymal transition

- F-actin

filamentous actin

- G-actin

globular actin

- HMW

high molecular weight

- LMW

low molecular weights

- miRNA or miR

microRNAs

- PKC

protein kinase C

- siRNA

small interference RNA

- Tpms

tropomyosins

- UTR

untranslated region

- VASP

vasodilator stimulated phosphoprotein

- WASP

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein

- WAVE

WASP and Verprolin homologous protein

- ZBP1

zipcode binding protein 1

- 2D

two dimensional

- 3D

three dimensional

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/celladhesion/article/23176

References

- 1.Thiery JP. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grünert S, Jechlinger M, Beug H. Diverse cellular and molecular mechanisms contribute to epithelial plasticity and metastasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:657–65. doi: 10.1038/nrm1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polyak K, Weinberg RA. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:265–73. doi: 10.1038/nrc2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajra KM, Fearon ER. Cadherin and catenin alterations in human cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;34:255–68. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navarro P, Gómez M, Pizarro A, Gamallo C, Quintanilla M, Cano A. A role for the E-cadherin cell-cell adhesion molecule during tumor progression of mouse epidermal carcinogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:517–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.2.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batlle E, Sancho E, Francí C, Domínguez D, Monfar M, Baulida J, et al. The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:84–9. doi: 10.1038/35000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cano A, Pérez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, et al. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yilmaz M, Christofori G. Mechanisms of motility in metastasizing cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:629–42. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ridley AJ. Life at the leading edge. Cell. 2011;145:1012–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vignjevic D, Montagnac G. Reorganisation of the dendritic actin network during cancer cell migration and invasion. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson MF, Sahai E. The actin cytoskeleton in cancer cell motility. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2009;26:273–87. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Machesky LM. Lamellipodia and filopodia in metastasis and invasion. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2102–11. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wehrle-Haller B. Structure and function of focal adhesions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:116–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark K, Langeslag M, Figdor CG, van Leeuwen FN. Myosin II and mechanotransduction: a balancing act. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:178–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedl P, Weigelin B. Interstitial leukocyte migration and immune function. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:960–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panková K, Rösel D, Novotný M, Brábek J. The molecular mechanisms of transition between mesenchymal and amoeboid invasiveness in tumor cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:63–71. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0132-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedl P, Wolf K. Plasticity of cell migration: a multiscale tuning model. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:11–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guck J, Lautenschläger F, Paschke S, Beil M. Critical review: cellular mechanobiology and amoeboid migration. Integr Biol (Camb) 2010;2:575–83. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00050g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charras GT. A short history of blebbing. J Microsc. 2008;231:466–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2008.02059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wyckoff JB, Pinner SE, Gschmeissner S, Condeelis JS, Sahai E. ROCK- and myosin-dependent matrix deformation enables protease-independent tumor-cell invasion in vivo. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1515–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lämmermann T, Sixt M. Mechanical modes of ‘amoeboid’ cell migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:636–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charras GT, Hu CK, Coughlin M, Mitchison TJ. Reassembly of contractile actin cortex in cell blebs. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:477–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson CA, Tsuchida MA, Allen GM, Barnhart EL, Applegate KT, Yam PT, et al. Myosin II contributes to cell-scale actin network treadmilling through network disassembly. Nature. 2010;465:373–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mellor H. The role of formins in filopodia formation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu X, Machesky LM. Cells assemble invadopodia-like structures and invade into matrigel in a matrix metalloprotease dependent manner in the circular invasion assay. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf K, Friedl P. Mapping proteolytic cancer cell-extracellular matrix interfaces. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2009;26:289–98. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamaguchi H. Pathological roles of invadopodia in cancer invasion and metastasis. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91:902–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy DA, Courtneidge SA. The ‘ins’ and ‘outs’ of podosomes and invadopodia: characteristics, formation and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:413–26. doi: 10.1038/nrm3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gligorijevic B, Wyckoff J, Yamaguchi H, Wang Y, Roussos ET, Condeelis J. N-WASP-mediated invadopodium formation is involved in intravasation and lung metastasis of mammary tumors. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:724–34. doi: 10.1242/jcs.092726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magalhaes MA, Larson DR, Mader CC, Bravo-Cordero JJ, Gil-Henn H, Oser M, et al. Cortactin phosphorylation regulates cell invasion through a pH-dependent pathway. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:903–20. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamaguchi H, Lorenz M, Kempiak S, Sarmiento C, Coniglio S, Symons M, et al. Molecular mechanisms of invadopodium formation: the role of the N-WASP-Arp2/3 complex pathway and cofilin. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:441–52. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calle Y, Chou HC, Thrasher AJ, Jones GE. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein and the cytoskeletal dynamics of dendritic cells. J Pathol. 2004;204:460–9. doi: 10.1002/path.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schoumacher M, Goldman RD, Louvard D, Vignjevic DM. Actin, microtubules, and vimentin intermediate filaments cooperate for elongation of invadopodia. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:541–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li A, Dawson JC, Forero-Vargas M, Spence HJ, Yu X, König I, et al. The actin-bundling protein fascin stabilizes actin in invadopodia and potentiates protrusive invasion. Curr Biol. 2010;20:339–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hillberg L, Zhao Rathje LS, Nyåkern-Meazza M, Helfand B, Goldman RD, Schutt CE, et al. Tropomyosins are present in lamellipodia of motile cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boczkowska M, Rebowski G, Petoukhov MV, Hayes DB, Svergun DI, Dominguez R. X-ray scattering study of activated Arp2/3 complex with bound actin-WCA. Structure. 2008;16:695–704. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Insall RH, Machesky LM. Actin dynamics at the leading edge: from simple machinery to complex networks. Dev Cell. 2009;17:310–22. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirkbride KC, Sung BH, Sinha S, Weaver AM. Cortactin: a multifunctional regulator of cellular invasiveness. Cell Adh Migr. 2011;5:187–98. doi: 10.4161/cam.5.2.14773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Derivery E, Gautreau A. Generation of branched actin networks: assembly and regulation of the N-WASP and WAVE molecular machines. Bioessays. 2010;32:119–31. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takenawa T, Suetsugu S. The WASP-WAVE protein network: connecting the membrane to the cytoskeleton. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:37–48. doi: 10.1038/nrm2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurisu S, Takenawa T. WASP and WAVE family proteins: friends or foes in cancer invasion? Cancer Sci. 2010;101:2093–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang C, Svitkina T. Filopodia initiation: focus on the Arp2/3 complex and formins. Cell Adh Migr. 2011;5:402–8. doi: 10.4161/cam.5.5.16971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Svitkina TM, Bulanova EA, Chaga OY, Vignjevic DM, Kojima S, Vasiliev JM, et al. Mechanism of filopodia initiation by reorganization of a dendritic network. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:409–21. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnston SA, Bramble JP, Yeung CL, Mendes PM, Machesky LM. Arp2/3 complex activity in filopodia of spreading cells. BMC Cell Biol. 2008;9:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamashiro-Matsumura S, Matsumura F. Purification and characterization of an F-actin-bundling 55-kilodalton protein from HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:5087–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sedeh RS, Fedorov AA, Fedorov EV, Ono S, Matsumura F, Almo SC, et al. Structure, evolutionary conservation, and conformational dynamics of Homo sapiens fascin-1, an F-actin crosslinking protein. J Mol Biol. 2010;400:589–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anilkumar N, Parsons M, Monk R, Ng T, Adams JC. Interaction of fascin and protein kinase Calpha: a novel intersection in cell adhesion and motility. EMBO J. 2003;22:5390–402. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hashimoto Y, Kim DJ, Adams JC. The roles of fascins in health and disease. J Pathol. 2011;224:289–300. doi: 10.1002/path.2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adams JC. Roles of fascin in cell adhesion and motility. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:590–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parsons M, Adams JC. Rac regulates the interaction of fascin with protein kinase C in cell migration. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2805–13. doi: 10.1242/jcs.022509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jayo A, Parsons M, Adams JC. A novel Rho-dependent pathway that drives interaction of fascin-1 with p-Lin-11/Isl-1/Mec-3 kinase (LIMK) 1/2 to promote fascin-1/actin binding and filopodia stability. BMC Biol. 2012;10:72. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-10-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamakita Y, Ono S, Matsumura F, Yamashiro S. Phosphorylation of human fascin inhibits its actin binding and bundling activities. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12632–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hashimoto Y, Parsons M, Adams JC. Dual actin-bundling and protein kinase C-binding activities of fascin regulate carcinoma cell migration downstream of Rac and contribute to metastasis. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4591–602. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishikawa R, Sakamoto T, Ando T, Higashi-Fujime S, Kohama K. Polarized actin bundles formed by human fascin-1: their sliding and disassembly on myosin II and myosin V in vitro. J Neurochem. 2003;87:676–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ricca BL, Rock RS. The stepping pattern of myosin X is adapted for processive motility on bundled actin. Biophys J. 2010;99:1818–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ponti A, Machacek M, Gupton SL, Waterman-Storer CM, Danuser G. Two distinct actin networks drive the protrusion of migrating cells. Science. 2004;305:1782–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1100533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gunning PW, Schevzov G, Kee AJ, Hardeman EC. Tropomyosin isoforms: divining rods for actin cytoskeleton function. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:333–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DesMarais V, Ichetovkin I, Condeelis J, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. Spatial regulation of actin dynamics: a tropomyosin-free, actin-rich compartment at the leading edge. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4649–60. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Phillips GN, Jr., Lattman EE, Cummins P, Lee KY, Cohen C. Crystal structure and molecular interactions of tropomyosin. Nature. 1979;278:413–7. doi: 10.1038/278413a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tojkander S, Gateva G, Schevzov G, Hotulainen P, Naumanen P, Martin C, et al. A molecular pathway for myosin II recruitment to stress fibers. Curr Biol. 2011;21:539–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ono S, Ono K. Tropomyosin inhibits ADF/cofilin-dependent actin filament dynamics. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:1065–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ishikawa R, Yamashiro S, Matsumura F. Differential modulation of actin-severing activity of gelsolin by multiple isoforms of cultured rat cell tropomyosin. Potentiation of protective ability of tropomyosins by 83-kDa nonmuscle caldesmon. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:7490–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bryce NS, Schevzov G, Ferguson V, Percival JM, Lin JJ, Matsumura F, et al. Specification of actin filament function and molecular composition by tropomyosin isoforms. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:1002–16. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-04-0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaneda A, Kaminishi M, Sugimura T, Ushijima T. Decreased expression of the seven ARP2/3 complex genes in human gastric cancers. Cancer Lett. 2004;212:203–10. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]