In 1958 Dr Paul Beeson made a compelling case against the routine use of indwelling urinary catheters in hospitalised patients.1 Despite his recognising their harm over 50 years ago, urethral catheterisation remains one of the most common bedside procedures undertaken in hospitals today and catheter-associated urinary tract infections are among the most common nosocomial infections.

Although their use has undeniable benefits in recognised and justifiable situations, their excessive use is associated with greater healthcare costs, increased discomfort and morbidity, and in some cases, even death. I will never forget the elderly patient who was admitted under the care of urology after his eleventh (failed) attempt at urethral catheterisation and developed gram-negative sepsis.

He died on the intensive care unit. Can we really justify this?

This article is a reminder for all doctors of when to insert urethral catheters and provides strategies for managing difficult insertions and removals.

I would also like to remind everyone that we welcome suggestions for future topics in this series, which I hope you are all finding useful.

JYOTI SHAH

Associate Editor

Reference

1. Beeson PB. The case against the catheter. Am J Med 1958; 24: 1–3.

Question

A 67-year-old man undergoes an elective knee replacement. After removal of his urethral catheter, he goes into acute, painful urinary retention. The FY1 on call, the orthopaedic SpR and the general surgery SpR are unable to reinsert a urethral catheter. How should this patient be managed?

Urethral catheterisation is one of the most frequently performed procedures in clinical practice. A study investigating 40 hospitals estimated that the overall rate of catheterisation in acute care was 26.3% (12–40%).1 Despite clear indications for catheterisation (Table 1), reports estimate that the inappropriate use of catheters ranges from 21% to over 50 %.2

Table 1.

Indications for urethral catheterisation

| Drainage | Acute and chronic urinary retention Incomplete bladder emptying After urological surgery-such as TURP/TURBT |

| Monitor | Monitor fluid balance – usually in critically ill patients |

| Instillation | Bladder instillations of drugs Obtain urine sample |

| Investigation | Radiological evaluation of lower urinary tract -cystogram/ urethrogram Urodynamics |

| Palliative | ‘Last resort’ for managing intractable urinary incontinence Palliate terminally ill patients Protect against pressure sores |

Diameter

Catheters are sized using the French (Fr) scale, such that 1Fr is 0.33mm in diameter. Catheters vary from 12Fr (small) to 28 Fr (large).

Length

| Paediatric: | 30–3 1cm |

| Female: | 20–26cm |

| Standard male: | 40–45 cm |

It is important to use the correct catheter length for each patient. Inflating a short female catheter in the male urethra can cause severe pain and lead to serious complications such as haematuria, penile swelling, urinary retention and renal failure. The National Patient Safety Agency has recently issued a rapid-response report on the importance of selecting the correct length of catheter.3

Materials

Catheters can be made of the following:

-

>

PVC/plastic – tend to be stiff and uncomfortable; short-term use only

-

>

Latex – only for short-term use; can cause anaphylaxis in latex allergy patients; hence most trusts are no longer using these

-

>

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or Teflon® – these are coated on a latex core and can be used for up to 28 days; they are unsuitable for latex allergy patients

-

>

100% silicone – last for 12 weeks and are hypoallergenic

-

>

Latex catheters coated with hydrogel – last 12 weeks but unsuitable in latex allergy patients

-

>

Silicone elastomer – coated on a latex core; tend to be flexible and comfortable and can last 12 weeks; unsuitable in latex allergy patients

Balloon

After a catheter has been successfully inserted, usually up to the hilt, the balloon should not be inflated until urine has drained, to ensure correct position. The balloon must be inflated with sterile water as per manufacturer’s recommendations (10–30ml).There are different sizes of balloons:

-

>

5ml – paediatric balloon

-

>

10ml – for standard use

-

>

30ml – for post-operative use

Do not use the following to inflate balloons:

-

>

Air – can result in the balloon floating in the bladder and thus poor drainage

-

>

Non-sterile water – may contain impurities and bacteria that can enter the bladder through diffusion

-

>

Saline – saline can crystallise in the inflating channel or the balloon itself, which can cause problems when deflating the balloon

Catheterization technique

It is standard practice to use an anaesthetic lubricating gel for catheterisation. Instillagel® is the most commonly used and contains lignocaine hydrochloride 2% and chlorhexidine 0.25%. Increasingly hypersensitivity reactions are being reported with the use of Instillagel® for catheterisation and it is therefore essential to ask the patient about any allergies before starting.

If the catheter is being inserted for retention, it is useful to record the residual volume of urine. In uncircumcised men, the foreskin should always be replaced over the glans to avoid paraphimosis.

Table 2.

Catheter types

| Adults – use a straight-tip Foley catheter for most indications (12–14Fr) |

| Adults males with obstruction at the level of the prostate – try a curved-tip Tiemann catheter (16–18Fr) |

| Adults with visible haematuria – try a large two-way Foley catheter (20–24Fr) or a three-way irrigation catheter (20–30Fr) |

Increasingly urologists are being consulted for difficult urethral catheterisations and their complications, which delay patient discharge (Table 3). Some causes for this are listed below:

-

>

urethral stricture

-

>

bladder neck contractures

-

>

benign prostatic hyperplasia

-

>

phimosis

-

>

meatal stenosis

-

>

tight external sphincter in anxious patients

-

>

poor techniques

Table 3.

Complications of difficult urethral catheterisations

| Urethral trauma leading to possible urethral rupture |

| Sepsis |

| Bleeding requiring transfusion/surgery |

| Prolonged hospitalisation |

| Fournier’s gangrene |

| Rectal perforation |

| Urethral stricture |

How do you recognise a failed male urethral catheterisation? It is suspected if the patient reports pain on inflating the balloon, no urine drains (you can press on the bladder to encourage drainage), when blood is seen at the tip of the catheter or when there is haematuria.

There are many approaches to the difficult urethral catheterisation and a step-wise plan to maximise success is discussed below.4

Inject 20ml of a water-soluble lubricant into the urethra to allow gentle dilatation. The average volume of the male urethra is 20ml.

A small 10–12Fr catheter can buckle or kink in the male urethra. Try a larger 14–16Fr silicone catheter.

Try a 16Fr Coudé or Tiemann curved-tip catheter that may negotiate the lateral lobes of the prostate or flip itself over a bladder neck contracture.

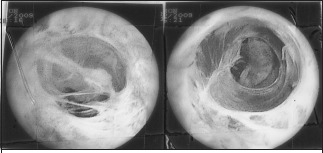

Use a catheter introducer that stiffens the catheter, allowing it to slip past the prostate rather than curl up against it. This should only be attempted by experienced staff to avoid creating false passages (Fig 1).

In an anxious patient where the difficulty is at the level of the sphincter, use 20ml lubricant and ask the patient to cough as you navigate the sphincter. Alternatively ask the patient either to strain gently as if passing urine or to relax their legs by pointing their toes outward and taking slow, deep breaths.

If a urethral stricture is suspected try a small 12Fr silicone (which is stiffer) catheter.

Patients who are in acute retention are often in a lot of pain and failed attempts at catheterisation can make this discomfort worse. Additionally, waiting for senior help to arrive adds to this pain. If there are no contraindications (same as those for suprapubic catheter insertion), then it is safe to use a small needle (21G) in patients whose bladder is palpable to aspirate 200–300ml urine using a 20ml or 50ml syringe. This process is time-consuming but can take pressure off the bladder and provide time for a definitive treatment. This procedure has also been listed as a safe interim measure in the National Patient Safety Agency rapid-response report.5

In cases of urethral stricture, try a small feeding tube.

Try passing a standard guide wire blindly into the bladder. Pass an open-ended ureteral catheter (a 6Fr ureteral catheter will pass over a 0.038-inch guide wire) and aspirate urine using a syringe (drainage may be slow). If the guide wire is placed into a false passage or hits a urethral stricture, then it tends to come back out of the urethra. Alternatively if most of the guide wire advances easily, then there is a high chance that it is within the bladder. Some hospitals have access to open-ended urethral catheters, which can be used instead of a ureteral catheter. Any catheter can be used as an open-ended one by cutting off the catheter tip without damaging the balloon mechanism or using an intravenous cannula to pierce the catheter tip, thereby allowing passage of the guide wire through it.

If there are no contraindications then a suprapubic catheter should be safely inserted (Table 4). The National Patient Safety Agency has issued a safety report on minimising risks associated with suprapubic catheter insertion.5

Most hospitals will have access to out-of-hours flexible cystoscopes. Perform a flexible cystoscopy to navigate under vision into the bladder and advance a guide wire into the bladder. A catheter can then be railroaded over the guide wire.

Figure 1. False passage secondary to multiple (8) catheter attempts in a 28-year-old-man.

Table 4.

Contraindications to suprapubic catheterisation

| Lower abdominal surgery (possible risk of bowel adhesions) |

| Bladder cancer |

| Anticoagulation/antiplatelet treatment (risk of uncontrolled haemorrhage) |

| Abdominal wall sepsis |

| Vascular graft in the suprapubic region |

Difficulties catheterising women are uncommon and often arise from failure to identify the urethra. The following can help with this problem:

-

>

Nurses are often more experienced at female catheterisation.

-

>

Place the patient head down on the bed.

-

>

Insert a speculum or finger into the vagina.

-

>

Dilate the urethra with lubricant.

Techniques to manage the non deflating urethral catheter

The most common cause of a non-deflating catheter is obstruction of the inflation channel due to crystallisation of the inflation fluid (more commonly with saline) or a faulty or failed valve. However, it is important to check for extrinsic compression from constipation, faecal impaction or a kinked catheter.

Advance the catheter to ensure that it is actually within the bladder.

Inject a small volume (up to 1ml) of sterile water into the balloon.

Aspirate the balloon slowly. If this is done rapidly, the valve mechanism may collapse.

Cut the balloon port flush to the point where it separates from the main catheter. This should allow water to drain spontaneously. Do not cut the port proximal to this point, which can result in retraction of the entire catheter into the bladder.

Place a ureteric guide wire into the inflation channel. This should pierce and deflate the balloon.

The balloon can be punctured suprapubically using ultrasound guidance.

If none of the above techniques are met with success, then a urologist can pierce the balloon endoscopically and simultaneously ensure there are no fragments retained within the bladder at cystoscopy.

Always check the catheter is intact to ensure there are no retained fragments in the bladder.

Key messages

One Fr is 0.33 mm in diameter (an 18Fr catheter is approximately 6mm in diameter).

-

>

Do not use a short female catheter in men.

-

>

Use sterile water to inflate the balloon.

-

>

Document residual volume in retention.

-

>

Replace foreskin in men after catheterisation.

-

>

Call for help after 1–2 gentle failed attempts at catheter insertion.

References

- 1.Glynn A, Ward V, Wilson J, et al. Hospital-acquired Infection: Surveillance, Policies and Practice. London: Public Health Laboratory Service; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hazelett SE, Tsai M, Gareri M, Allen K. The association between indwelling urinary catheter use in the elderly and urinary tract infection in acute care. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-6-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Patient Safety Agency. Female urinary catheters causing trauma to adult males. London: NPSA; 2009. NPSA/2009/RRR02. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villanueva C, Hemstreet GP. Diffcult male urethral catheterization: a review of different approaches. Int Braz J Urol. (3rd) 2008;34:401–412. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382008000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Patient Safety Agency. Minimising risks of suprapubic catheter insertion (adults only) London: NPSA; 2010. NPSA/2009/RRR005. [Google Scholar]