Abstract

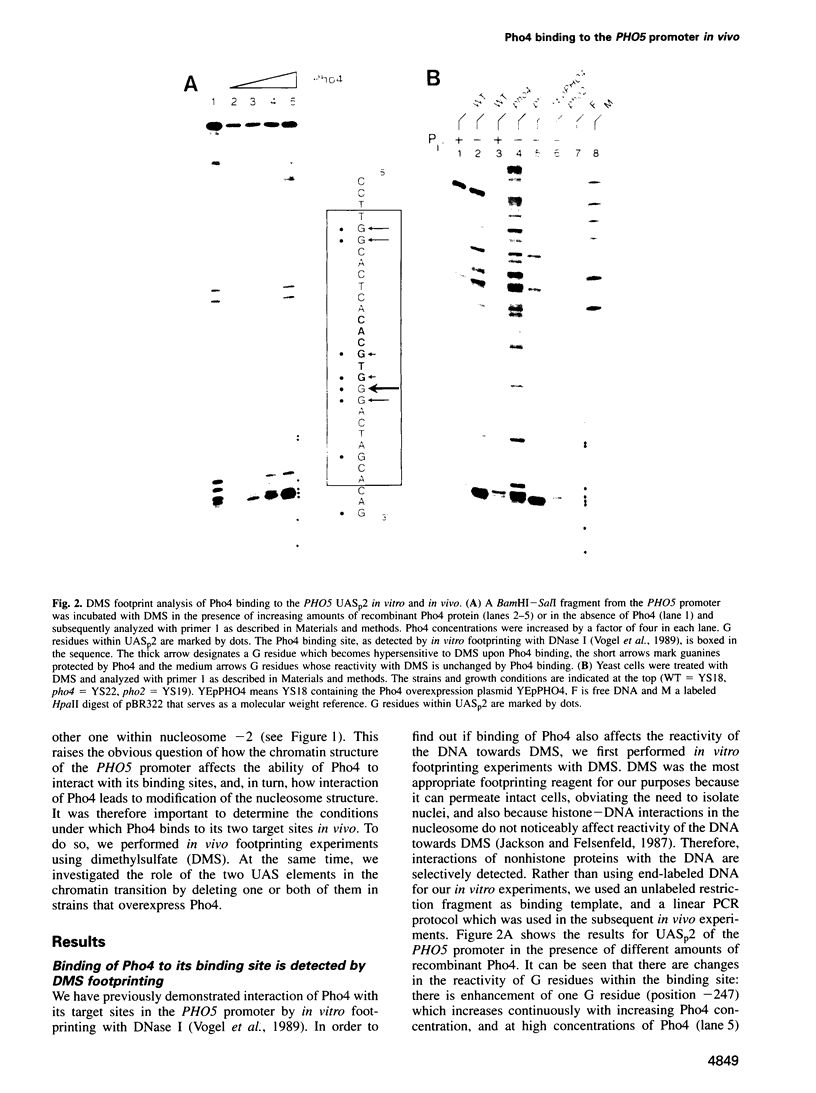

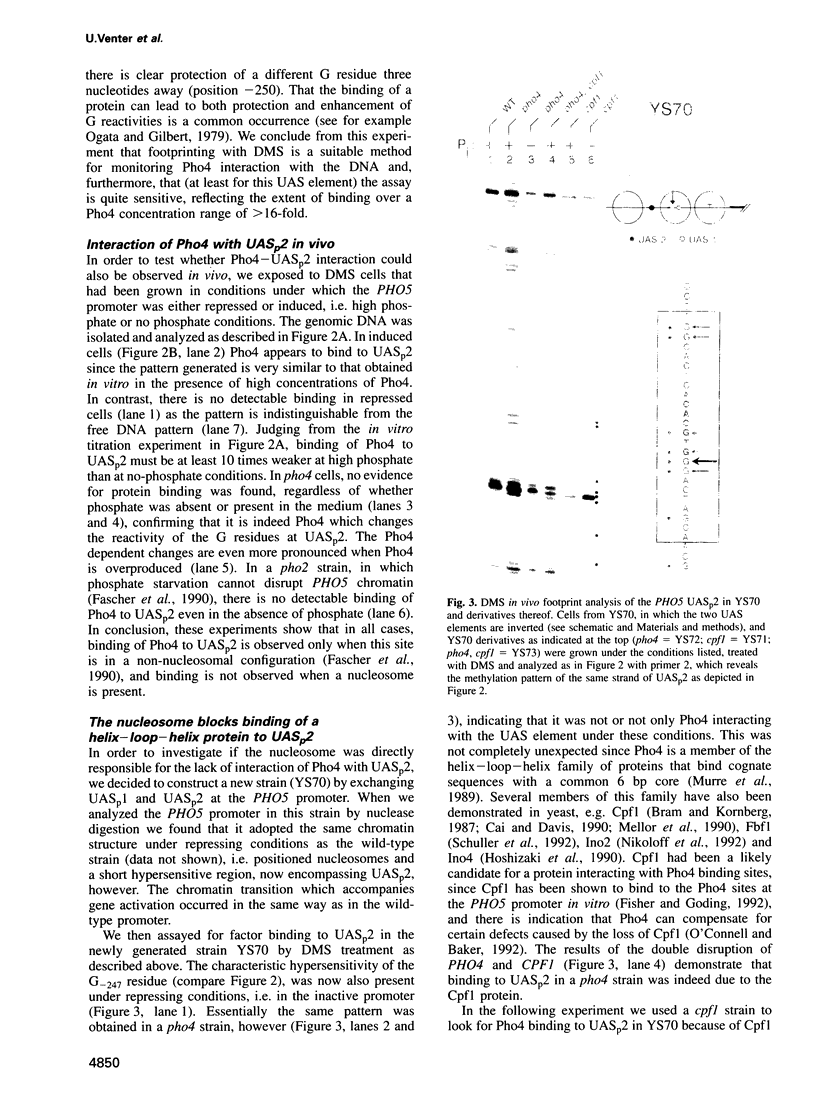

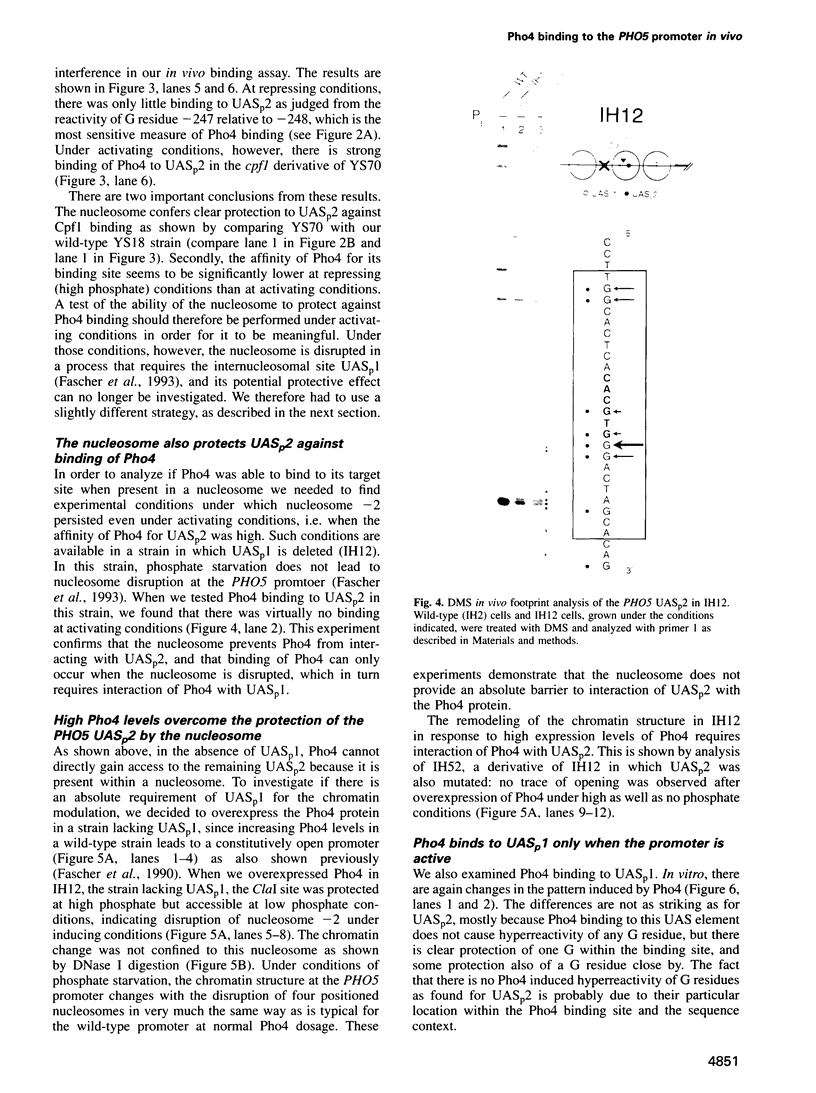

Activation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae PHO5 gene by phosphate starvation is accompanied by the disappearance of two pairs of positioned nucleosomes that flank a short hypersensitive region in the promoter. The transcription factor Pho4 is the key regulator of this transition. By in vitro footprinting it was previously shown that there is a low affinity site (UASp1) which is contained in the short hypersensitive region in the inactive promoter, and a high affinity site (UASp2) which is located in the adjacent nucleosome. To investigate the interplay between nucleosomes and Pho4, we have performed in vivo footprinting experiments with dimethylsulfate. Pho4 was found to bind to both sites in the active promoter. In contrast, it binds to neither site in the repressed promoter. Lack of binding under repressing conditions is largely due to the low affinity of Pho4 for its binding sites under these conditions. Despite the increased affinity of Pho4 for its target sites under activating conditions, binding to UASp2 is prevented by the presence of the nucleosome and can only occur after prior disruption of this nucleosome in a process that requires UASp1. Protection of the PHO5 UASp2 by the nucleosome is not absolute, however, since overexpression of Pho4 can disrupt this nucleosome even when UASp1 is deleted. Also under these conditions, with only UASp2 present, all four nucleosomes at the PHO5 promoter are disrupted, whereas no chromatin change at all is observed when both UAS elements are destroyed.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Almer A., Hörz W. Nuclease hypersensitive regions with adjacent positioned nucleosomes mark the gene boundaries of the PHO5/PHO3 locus in yeast. EMBO J. 1986 Oct;5(10):2681–2687. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almer A., Rudolph H., Hinnen A., Hörz W. Removal of positioned nucleosomes from the yeast PHO5 promoter upon PHO5 induction releases additional upstream activating DNA elements. EMBO J. 1986 Oct;5(10):2689–2696. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod J. D., Reagan M. S., Majors J. GAL4 disrupts a repressing nucleosome during activation of GAL1 transcription in vivo. Genes Dev. 1993 May;7(5):857–869. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bram R. J., Kornberg R. D. Isolation of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae centromere DNA-binding protein, its human homolog, and its possible role as a transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Jan;7(1):403–409. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.1.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazas R. M., Stillman D. J. Identification and purification of a protein that binds DNA cooperatively with the yeast SWI5 protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1993 Sep;13(9):5524–5537. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresnick E. H., Bustin M., Marsaud V., Richard-Foy H., Hager G. L. The transcriptionally-active MMTV promoter is depleted of histone H1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992 Jan 25;20(2):273–278. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.2.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai M., Davis R. W. Yeast centromere binding protein CBF1, of the helix-loop-helix protein family, is required for chromosome stability and methionine prototrophy. Cell. 1990 May 4;61(3):437–446. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90525-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croston G. E., Laybourn P. J., Paranjape S. M., Kadonaga J. T. Mechanism of transcriptional antirepression by GAL4-VP16. Genes Dev. 1992 Dec;6(12A):2270–2281. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans T., Felsenfeld G., Reitman M. Control of globin gene transcription. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1990;6:95–124. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fascher K. D., Schmitz J., Hörz W. Role of trans-activating proteins in the generation of active chromatin at the PHO5 promoter in S. cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1990 Aug;9(8):2523–2528. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fascher K. D., Schmitz J., Hörz W. Structural and functional requirements for the chromatin transition at the PHO5 promoter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae upon PHO5 activation. J Mol Biol. 1993 Jun 5;231(3):658–667. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg A. P., Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1983 Jul 1;132(1):6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenfeld G. Chromatin as an essential part of the transcriptional mechanism. Nature. 1992 Jan 16;355(6357):219–224. doi: 10.1038/355219a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher F., Goding C. R. Single amino acid substitutions alter helix-loop-helix protein specificity for bases flanking the core CANNTG motif. EMBO J. 1992 Nov;11(11):4103–4109. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert D. M., Losson R., Chambon P. Ligand dependence of estrogen receptor induced changes in chromatin structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992 Sep 11;20(17):4525–4531. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.17.4525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giniger E., Varnum S. M., Ptashne M. Specific DNA binding of GAL4, a positive regulatory protein of yeast. Cell. 1985 Apr;40(4):767–774. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D. S., Adams C. C., Lee S., Stentz B. A critical role for heat shock transcription factor in establishing a nucleosome-free region over the TATA-initiation site of the yeast HSP82 heat shock gene. EMBO J. 1993 Oct;12(10):3931–3945. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhorn J. N., Brown S. A., Clark C. D., Winston F. Evidence that SNF2/SWI2 and SNF5 activate transcription in yeast by altering chromatin structure. Genes Dev. 1992 Dec;6(12A):2288–2298. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshizaki D. K., Hill J. E., Henry S. A. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae INO4 gene encodes a small, highly basic protein required for derepression of phospholipid biosynthetic enzymes. J Biol Chem. 1990 Mar 15;265(8):4736–4745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Fukuda Y., Murata K., Kimura A. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J Bacteriol. 1983 Jan;153(1):163–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.163-168.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson P. D., Felsenfeld G. In vivo footprinting of specific protein-DNA interactions. Methods Enzymol. 1987;152:735–755. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaffman A., Herskowitz I., Tjian R., O'Shea E. K. Phosphorylation of the transcription factor PHO4 by a cyclin-CDK complex, PHO80-PHO85. Science. 1994 Feb 25;263(5150):1153–1156. doi: 10.1126/science.8108735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg R. D., Lorch Y. Chromatin structure and transcription. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:563–587. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg R. D., Lorch Y. Irresistible force meets immovable object: transcription and the nucleosome. Cell. 1991 Nov 29;67(5):833–836. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. S., Garrard W. T. Uncoupling gene activity from chromatin structure: promoter mutations can inactivate transcription of the yeast HSP82 gene without eliminating nucleosome-free regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Oct 1;89(19):9166–9170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson C. E., Shim E. Y., Friedman D. S., Zaret K. S. An active tissue-specific enhancer and bound transcription factors existing in a precisely positioned nucleosomal array. Cell. 1993 Oct 22;75(2):387–398. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80079-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor J., Jiang W., Funk M., Rathjen J., Barnes C. A., Hinz T., Hegemann J. H., Philippsen P. CPF1, a yeast protein which functions in centromeres and promoters. EMBO J. 1990 Dec;9(12):4017–4026. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. E., Whitlock J. P., Jr Transcription-dependent and transcription-independent nucleosome disruption induced by dioxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Dec 1;89(23):11622–11626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murre C., McCaw P. S., Baltimore D. A new DNA binding and dimerization motif in immunoglobulin enhancer binding, daughterless, MyoD, and myc proteins. Cell. 1989 Mar 10;56(5):777–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoloff D. M., McGraw P., Henry S. A. The INO2 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes a helix-loop-helix protein that is required for activation of phospholipid synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992 Jun 25;20(12):3253–3253. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.12.3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell K. F., Baker R. E. Possible cross-regulation of phosphate and sulfate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1992 Sep;132(1):63–73. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata R. T., Gilbert W. DNA-binding site of lac repressor probed by dimethylsulfate methylation of lac operator. J Mol Biol. 1979 Aug 25;132(4):709–728. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90384-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada H., Toh-e A. A novel mutation occurring in the PHO80 gene suppresses the PHO4c mutations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 1992 Feb;21(2):95–99. doi: 10.1007/BF00318466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham T. A., Hwung Y. P., McDonnell D. P., O'Malley B. W. Transactivation functions facilitate the disruption of chromatin structure by estrogen receptor derivatives in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1991 Sep 25;266(27):18179–18187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reik A., Schütz G., Stewart A. F. Glucocorticoids are required for establishment and maintenance of an alteration in chromatin structure: induction leads to a reversible disruption of nucleosomes over an enhancer. EMBO J. 1991 Sep;10(9):2569–2576. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph H., Hinnen A. The yeast PHO5 promoter: phosphate-control elements and sequences mediating mRNA start-site selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Mar;84(5):1340–1344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild C., Claret F. X., Wahli W., Wolffe A. P. A nucleosome-dependent static loop potentiates estrogen-regulated transcription from the Xenopus vitellogenin B1 promoter in vitro. EMBO J. 1993 Feb;12(2):423–433. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid A., Fascher K. D., Hörz W. Nucleosome disruption at the yeast PHO5 promoter upon PHO5 induction occurs in the absence of DNA replication. Cell. 1992 Nov 27;71(5):853–864. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90560-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüller H. J., Hahn A., Tröster F., Schütz A., Schweizer E. Coordinate genetic control of yeast fatty acid synthase genes FAS1 and FAS2 by an upstream activation site common to genes involved in membrane lipid biosynthesis. EMBO J. 1992 Jan;11(1):107–114. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengstag C., Hinnen A. A 28-bp segment of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae PHO5 upstream activator sequence confers phosphate control to the CYC1-lacZ gene fusion. Gene. 1988 Jul 30;67(2):223–228. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90399-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengstag C., Hinnen A. The sequence of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene PHO2 codes for a regulatory protein with unusual aminoacid composition. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987 Jan 12;15(1):233–246. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.1.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straka C., Hörz W. A functional role for nucleosomes in the repression of a yeast promoter. EMBO J. 1991 Feb;10(2):361–368. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svaren J., Hörz W. Histones, nucleosomes and transcription. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993 Apr;3(2):219–225. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90026-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svaren J., Schmitz J., Hörz W. The transactivation domain of Pho4 is required for nucleosome disruption at the PHO5 promoter. EMBO J. 1994 Oct 17;13(20):4856–4862. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06812.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D., Jacquemin I., Surdin-Kerjan Y. MET4, a leucine zipper protein, and centromere-binding factor 1 are both required for transcriptional activation of sulfur metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1992 Apr;12(4):1719–1727. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel K., Hörz W., Hinnen A. The two positively acting regulatory proteins PHO2 and PHO4 physically interact with PHO5 upstream activation regions. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 May;9(5):2050–2057. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.5.2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman J. L., Kingston R. E. Nucleosome core displacement in vitro via a metastable transcription factor-nucleosome complex. Science. 1992 Dec 11;258(5089):1780–1784. doi: 10.1126/science.1465613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]