Abstract

Purpose.

Quantitative fundus autofluorescence (qAF), spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) segmentation, and multimodal imaging were performed to elucidate the pathogenesis of Best vitelliform macular dystrophy (BVMD) and to identify abnormalities in lesion versus nonlesion fundus areas.

Methods.

Sixteen patients with a clinical diagnosis of BVMD were studied. Autofluorescence images (30°, 488-nm excitation) were acquired with a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope equipped with an internal fluorescent reference to account for variable laser power and detector sensitivity. The grey levels (GLs) of each image were calibrated to the reference, zero GL, magnification, and normative optical media density, to yield qAF. Horizontal SD-OCT scans were obtained and retinal layers manually segmented. Additionally, color and near-infrared reflectance (NIR-R) images were registered to AF images. All patients were screened for mutations in BEST1. In three additional BVMD patients, in vivo spectrofluorometric measurements were obtained within the vitelliform lesion.

Results.

Mean nonlesion qAF was within normal limits for age. Maximum qAF within the lesion was markedly increased compared with controls. By SD-OCT segmentation, outer segment equivalent thickness was increased and outer nuclear layer thickness decreased in the lesion. Changes were also present in a transition zone beyond the lesion border. In subclinical patients, no abnormalities in retinal layer thickness were identified. Fluorescence spectra recorded from the vitelliform lesion were consistent with those of retinal pigment epithelial cell lipofuscin.

Conclusions.

Based on qAF, mutations in BEST1 do not cause increased lipofuscin levels in nonlesion fundus areas.

Keywords: Best vitelliform macular dystrophy, bestrophin, lipofuscin, optical coherence tomography, quantitative fundus autofluorescence, retina, retinal pigment epithelium, scanning laser ophthalmoscope

In patients with Best vitelliform macular dystrophy, quantitative fundus autofluorescence levels outside the lesion were within the 95% confidence intervals of age-similar healthy subjects.

Introduction

Best vitelliform macular dystrophy (BVMD; also known as Best's disease) is a rare disorder that is typically inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Best vitelliform macular dystrophy is caused by mutations in BEST1 (formerly known as VMD2), a gene located on chromosome 11q131 that transcribes the bestrophin-1 protein located on the basolateral membrane of RPE cells.2 Ophthalmoscopic features of BVMD are usually restricted to the macula, although the reason for this is not clear and eccentric vitelliform lesions can occur.3,4 Fundus abnormalities are typically visible within the first 2 decades of life but cases of late onset (e.g., age 75) have been reported.5 The early stage of BVMD is characterized by a dome-shaped, fluid-filled lesion (vitelliform lesion) in the central macula that is well delineated and appears markedly intense by fundus autofluorescence (AF) imaging.6

The full-field electroretinogram (ERG) in BVMD is usually normal although there can be exceptions.7 Conversely, there is typically an abnormal electrooculogram (EOG),8 an electrophysiological test that measures changes in the transepithelial potential across the RPE.9 In BVMD, the voltage amplitude in response to light (light peak) is diminished as is the corresponding ratio between the light peak and dark trough (Arden ratio; >1.8 in healthy subjects). However, technical difficulties and the need for patient cooperation can make it difficult to detect the voltage change, particularly in children.

For a retinal disease such as BVMD, wherein histopathologic material is limited, optical coherence tomography (OCT) has been an invaluable tool to document disease pathology and progression. Studies using OCT have localized the vitelliform lesion to the subretinal space.6,10,11 Moreover, recent studies have reported thickening of the highly reflective band attributable to ensheathed cone outer segments (eOS12; previously referred to as cone outer segment tips, or COST13) in eyes with subclinical stage BVMD.10,14 However, this thickening has not been quantified and compared with a larger group of healthy controls.

It has been reported,15–19 and it is generally assumed,6,20,21 that levels of lipofuscin in the RPE are increased in BVMD. Nevertheless, the mechanism linking impaired bestrophin-1 functioning and a possible build-up of lipofuscin remains unexplained. Some reports of increased lipofuscin in BVMD have been based on nonquantitative assessment.15,16,18 In another case, measurements acquired from electron microscopic images led to the conclusion that the fraction of RPE cell volume occupied by lipofuscin granules was greater in BVMD versus non-BVMD eyes.17 Increases in the RPE lipofuscin fluorophore A2E were also noted in tissue taken from the eye of a donor homozygous for the W93C mutation in BEST1 and from a donor heterozygous for the T6R mutation.19 However, based on qualitative assessment, lipofuscin accumulation was normal for age in a donor heterozygous for the Y227N mutation.22 There is also disagreement as to whether AF, a marker for RPE lipofuscin,23 is increased in fundus areas outside the macular lesion in BVMD, as compared with control subjects.24–26

We recently developed a robust method for quantitative measurements of AF (qAF) with a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope (cSLO).27 This novel imaging technique permits noninvasive indirect measurement of lipofuscin levels across the posterior pole. Fluorescence from an internal reference is used to compensate for changes in laser power and detector sensitivity of the cSLO.

The pathogenesis of BVMD is not fully understood and whether nonlesion retina in BVMD can be considered normal has been a matter of speculation. In this study, we used qAF to assess whether levels of RPE lipofuscin differ from normal in fundus areas outside of the macular lesion. In addition, we measured qAF levels within the lesion and determined retinal layer thicknesses by spectral domain-OCT (SD-OCT) segmentation. These quantitative analyses in conjunction with multimodal imaging allowed us to identify and characterize structurally abnormal fundus areas.

Methods

Patients

Included in this study were 16 patients with BVMD from 11 unrelated families. Demographic, clinical, and genetic data are presented in the Table. The clinical diagnosis of BVMD was based on fundus appearance, family history, and a decreased Arden ratio on EOG. The latter test was performed according to International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV) standards.28 Best vitelliform macular dystrophy patients were staged based on fundus photographs and the system introduced by Gass29 and expanded on more recently by OCT findings.10 From the 31 eyes that were included in the study, 10 were in the subclinical stage, 4 were in the vitelliform stage (2 of which were multifocal), 2 were in the pseudohypopyon stage, 12 were in the vitelliruptive stage, and 3 were atrophic. The left eye of Patient 12 (P12) could not be staged because of a corneal scar. Mutations in the BEST1 gene were identified in 14 of 16 patients. Patient 9 was not genotyped but a mutation was confirmed in the father (P8). No mutation was identified in P10, a case of multifocal BVMD. While subclinical cases are often referred to as the previtelliform stage it cannot be assumed that subclinical BVMD will progress to a vitelliform lesion.

Table.

Summary of Demographic, Clinical, and Genetic Data

|

Patient |

Family |

Sex |

Age |

Race/Ethnicity |

EOG (Arden Ratio) |

Mutation |

Disease Stage |

BCVA, logMAR |

Refraction, D |

Axial Length, mm |

|||||

|

OD |

OS |

OD |

OS |

OD |

OS |

OD |

OS |

OD |

OS |

||||||

| 1 | I | F | 30.6 | White | 1.41 | 1.90 | p.Cys221Trp | Vitelliruptive | Vitelliruptive | 0.18 | 0.48 | 1.50 | 2.00 | 21.78 | 21.58 |

| 2 | II | M | 54.7 | White | 1.36 | 1.28 | p.Asn296Ser | Vitelliruptive | Vitelliruptive | 0.60 | 0.48 | 4.25 | 4.00 | 22.03 | 22.05 |

| 3 | II | M | 16.4 | White | 1.13 | 1.68 | p.Asn296Ser | Vitelliruptive | Vitelliruptive | −0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | 22.64 | 22.60 |

| 4 | III | F | 57.7 | White | - | - | p.Asp302Ala | Subclinical | Vitelliruptive | 0.18 | 0.88 | 2.50 | 2.75 | 23.60 | 23.31 |

| 5 | IV | F | 27.9 | White | 1.18 | 1.27 | p.Ala243Thr | Subclinical | Subclinical | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | - | - |

| 6 | V | M | 52.4 | Hispanic | 1.80 | 1.76 | p.Arg218His | Vitelliruptive | Vitelliruptive | 0.70 | 0.40 | 3.00 | 3.50 | 22.04 | 21.27 |

| 7 | VI | F | 5.7 | Black | * | * | p.Ala10Thr | Pseudohypopyon | Pseudohypopyon | 0.60 | 0.80 | 7.50 | 7.00 | - | - |

| 8 | VII | M | 41.0 | Hispanic | - | - | p.Ala243Thr | (Subclinical) | Subclinical | (0.10) | 0.00 | (2.25) | 1.50 | (22.98) | 23.60 |

| 9 | VII | M | 10.6 | White | - | - | Not tested | (Atrophic) | Subclinical | (0.40) | 0.30 | (5.00) | 5.00 | (20.87) | 20.90 |

| 10 | VIII | F | 33.1 | Hispanic | 1.50 | 1.65 | Not found | Multifocal vitelliform | Multifocal vitelliform | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 23.09 | 23.15 |

| 11 | IX | M | 34.1 | White | (1.22) | 1.17 | p.Ala243Thr | (Atrophic) | Atrophic | (1.30) | 0.30 | (5.00) | 2.50 | - | - |

| 12 | IX | M | 61.9 | White | * | * | p.Ala243Thr | Vitelliruptive | - | 0.70 | - | 6.00 | - | - | - |

| 13 | X | F | 18.5 | Hispanic | 1.29 | 1.41 | p.Arg218His | Subclinical | Subclinical | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 23.33 | 23.29 |

| 14 | X | M | 14.9 | Hispanic | (1.88) | 1.71 | p.Arg218His | (Vitelliform) | Vitelliform | (0.10) | 0.00 | (4.00) | 3.00 | (22.84) | 23.27 |

| 15 | X | F | 47.2 | Hispanic | 1.28 | 1.26 | p.Arg218His | Subclinical | Subclinical | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 23.88 | 23.66 |

| 16 | XI | M | 7.4 | White | - | - | p.Leu234Pro | Vitelliruptive | Vitelliruptive | 0.10 | 0.10 | 4.25 | 4.50 | - | - |

| Mean | 32.1 | 1.41 | 1.51 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 3.16 | 2.77 | 22.64 | 22.61 | ||||||

Values in parenthesis indicate eyes without qAF images. BCVA, best corrected visual acuity.

Technical difficulties.

All patients had clear media except for some floaters. Ages of the patients ranged from 6 to 62 years (average 32.1 ± 18.8 years) and were similar to the 277 healthy subjects (mean 32.6 ± 13.6 years, range, 5–60 years) reported previously30 (two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P = 0.28); qAF values obtained from the latter subjects served as control data of the study. Other information about the study cohort can be found in the Table. The BVMD eyes were significantly more hyperopic than those of healthy controls (mixed-effects regression, P < 0.001). Similarly, the axial lengths of BVMD eyes were shorter than for control eyes (mixed-effects regression, P = 0.001). Among the BVMD patients there was no difference in axial length (P = 0.59) and refraction (P = 0.93) between left and right eyes (two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test).

All procedures adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients after a full explanation of the procedures was provided. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Columbia University (New York, NY).

Image Acquisition

Autofluorescent images (30°; 488-nm excitation) were acquired using a cSLO (Spectralis HRA+OCT; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) modified by the insertion of an internal fluorescent reference to account for variable laser power and detector gain.27 The barrier filter in the device transmitted light from 500 to 680 nm. Before image acquisition, pupils were dilated to at least 7 mm with topical 1% tropicamide and 2.5% phenylephrine. With room lights turned off, a near-infrared reflectance (NIR-R) image was recorded first. After switching to AF mode (488-nm excitation; beam power < 260 μW) the camera was slowly moved toward the patient to allow the patient to adapt to the blue light. Patients were asked to focus on the central fixation light of the device. The fundus was exposed for 20 to 30 seconds to bleach rhodopsin,27 while the focus and alignment were refined to produce maximum and uniform signal over the whole field. The detector sensitivity was adjusted so that the GL did not exceed the linear range of the detector (GL < 175).27 Two or more images were then recorded (each of nine frames, in video format) in the high-speed mode (8.9 frames/s) within a 30×30° field (768 × 768 pixels). To assess repeatability, a second session of AF images was recorded in a subset of eyes (10 eyes of six patients) after repositioning patient and camera. After imaging, all videos were inspected for image quality and consistency in GLs by two of the authors (TD, JPG). For an imaging session, two videos were selected to generate the AF images for analysis. Only frames without localized or generalized decreased AF signal (due to eyelid interference or iris obstruction) and no large misalignment of frames (causing double images after alignment) were considered. The frames then were aligned and averaged with the system software and saved in nonnormalized mode (no histogram stretching).

In addition, a horizontal 9-mm SD-OCT scan through the fovea was acquired in high-resolution mode as an average of 100 individual scans. Optical depth resolution in the Spectralis is approximately 7 μm. Color images were obtained with the FF450+IR fundus camera (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany). Images of the same field were registered to each other using custom software31 running in Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

AF Image Analysis

Autofluorescence images were analyzed under the control of an experienced operator with dedicated image analysis software written in IGOR (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR).27 The software recorded the mean GLs of the internal reference and of three rings (outer, middle, and inner), each consisting of eight circularly arranged segments (Fig. 1), and a software algorithm accounted for the presence of vessels in the sampling area.27 Spectral-domain OCT scans (registered to AF or NIR-R images) were used to estimate the position of the fovea in patients with a macular lesion. The GLs of each segment were calibrated to the reference, zero GL, magnification, and optical media density from normative data on lens transmission spectra32 to give qAF.27 Magnification is determined by the cSLO optics and the refraction status of the eye; the significant difference in refraction of the BVMD eyes compared with that of healthy eyes was thus accounted for.

Figure 1.

Fundus AF image analysis. (A) P16, vitelliruptive stage. Mean GLs were recorded from the internal reference (black rectangle, top of image) and from three rings: outer (black dotted lines), middle and inner (red solid lines), each consisting of eight circularly arranged segments. As shown for P16, for the current study, nonlesion qAF was calculated for segments in middle and inner rings. The segments were scaled to the distance between the temporal edge of the optic disc (white vertical line) and the center of the fovea (black cross). (B) P2, vitelliruptive stage. In this patient, the inferior and inferonasal segments of the middle ring were excluded because these segments overlapped with the high AF area of the lesion (segments outlined in white). Nonlesion qAF was not calculated for the inner ring (segments outlined in white) because more than three of the segments overlapped with the lesion.

We used the outer contour of the area exhibiting a high AF signal to define the limits of the macular lesion in AF images. For each eye nonlesion mean qAF values were obtained for the middle ring and for the inner ring (Fig. 1). To determine the mean qAF outside the lesion, only segments of the middle and inner ring that did not overlap with the lesion were included in the analysis. To this end, for the middle ring, in eight eyes (six patients) it was necessary to exclude one to three segments that overlapped with high AF lesion areas. For the inner ring, in three eyes (three patients) one to three segments had to be excluded. Inner ring measurements were not included for 11 eyes (eight patients) in which more than three segments overlapped with the high AF lesion (Fig. 1B). From all remaining segments of a ring the mean qAF (nonlesion retina) was generated. By taking topographic AF variations (the superotemporal fundus generally has the highest AF signal)30,33 and known instrument nonuniformities30 into consideration, we estimated that exclusion of segments would affect mean qAF by less than ±2%. Mean qAF values were based on two images; when a second session of AF imaging had been performed the averages were based on four images. Subsequently, comparison was made to values from previously published healthy controls (277 subjects).30 We used the Bland-Altman method34 to test the between-session repeatability of nonlesion qAF measurements obtained from the middle ring in 10 eyes of six patients, and to assess the agreement of qAF measurements obtained from the middle ring between left and right eyes in 11 patients.

The maximum qAF in a 26 × 26 pixel area was automatically measured in IGOR (WaveMetrics) for patients in the vitelliform and pseudohypopyon stages. Measurements from all available images were averaged for each eye.

Spectrofluorometry

In addition to the patients described in the Table, in three patients (ages, 9–46 years), having a clinical diagnosis of BVMD, in vivo spectrofluorometric measurements were obtained within the vitelliform lesion. As previously described23 emissions were recorded between 520 and 740 nm with 470-nm excitation (20-nm bandwidth). The data were corrected for absorption by the ocular media. The protocol for these measurements was approved by the institutional review board of the Schepens Eye Research Institute (Harvard Medical School, MA).

SD-OCT Segmentation

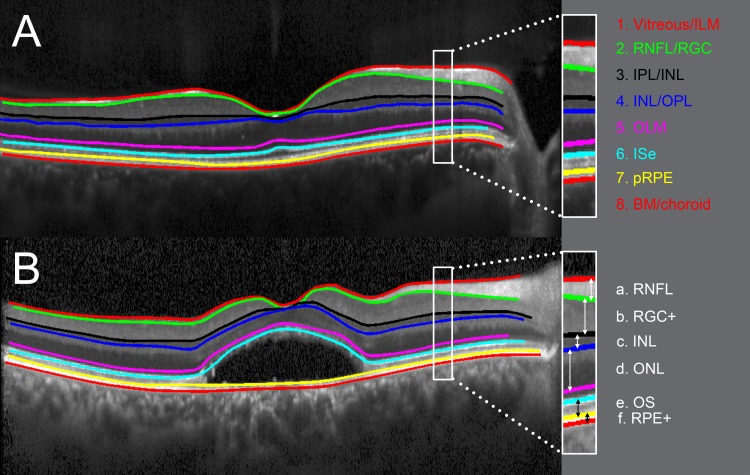

Horizontal SD-OCT line scans through the fovea from one eye per patient were manually segmented, aided by a custom computer program operating in Matlab (MathWorks). The segmentation technique has been described previously35 and was shown to have good reliability.36 For each patient, the eye with the smaller lesion size was analyzed. If no lesion was present, the right eye was chosen for analysis. Eight borders, labeled 1 through 8 in Figure 2, were segmented: (1) the border between vitreous and inner limiting membrane (ILM), (2) the border between retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and retinal ganglion cell layer (RGC), (3) the border between inner plexiform layer (IPL) and inner nuclear layer (INL), (4) the border between INL and outer plexiform layer (OPL), (5) the center of the outer limiting membrane (OLM), (6) the center of the hyperreflective inner segment ellipsoid (ISe) band, (7) the proximal border of the retinal pigment epithelium (pRPE), and (8) the border between Bruch's membrane (BM) and choroid. As shown in Figure 2, six retinal layers were derived from these eight boundaries: a. RNFL: distance between ILM (1) and RNFL/RGC (2); b. RGC+: distance between RNFL/RGC (2) and IPL/INL (3); c. INL: distance between IPL/INL (3) and INL/OPL (4); d. ONL: distance between INL/OPL (4) and OLM (5); e. OS (outer segment): distance between ISe (6) and pRPE (7); and f. RPE+: distance between pRPE (7) and BM/choroid (8). Mean thicknesses for each of the six layers were compared with those of 35 healthy subjects (mean age 45.1 ± 15.0 years, range, 15–65 years).

Figure 2.

Segmentation of retinal layers. Horizontal SD-OCT from a healthy subject (A) and from a BVMD patient in the vitelliruptive stage ([B]; P6). Segmented boundaries are indicated as colored lines. Six retinal layers, labelled in white, are derived from these boundaries: a. RNFL: distance between ILM (1) and RNFL/RGC (2). b. RGC+: distance between RNFL/RGC (2) and IPL/INL (3). c. INL: distance between IPL/INL (3) and INL/OPL (4). d. ONL: distance between INL/OPL (4) and OLM (5). e. OS: distance between ISe (6) and pRPE (7). f. RPE+: distance between pRPE (7) and BM/choroid (8).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and Stata 12.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). Where appropriate, we used mixed-effects linear regression that accounts for within-subject correlations between eyes and between close family members (e.g., sibling, parent–child).

Results

Multimodal Imaging

Vitelliform lesions of BVMD have typically been defined by their appearance on color fundus photographs.29 These lesions are also intense in AF images.6 We used the outer contour of the area exhibiting high AF signal (dashed vertical lines in Figs. 3A–6A) to define the limits of the macular lesion in AF images. With image registration, this boundary exhibited good correspondence to the lesion observed in color fundus photographs (Figs. 3C–5C) and to the altered reflectance observed in NIR-R (Figs. 3B–6B). In one eye in the vitelliruptive stage the lesion exhibited reduced AF signal throughout. To define the limits of the macular lesion in this case, we relied on the outer border of the area of reduced AF.

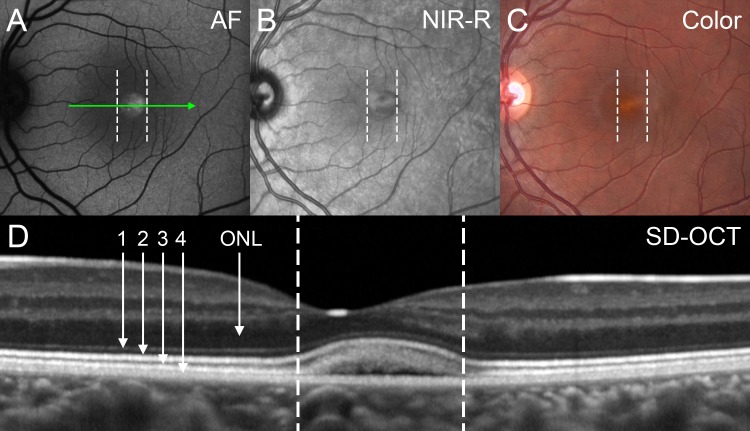

Figure 3.

Vitelliform stage (P14). With image registration, corresponding positions in the images (A–D) are shown as dashed vertical lines. (A) By fundus AF the foveal lesion exhibits an increased AF signal. (B) The contour of the lesion is well defined by NIR-R. (C) The color image demonstrates a vitelliform lesion. (D) The position and horizontal extent of the SD-OCT scan is indicated by the green arrow in (A). A dome-shaped foveal lesion that includes a hyporeflective component is revealed. Retina appears qualitatively normal outside the lesion. The ONL is visible as a hyporeflective band. Four previously described hyperreflective bands are visible in outer retina: (1) OLM, (2) ellipsoid region of photoreceptor inner segment ellipsoid (ISe; previously referred to as inner segment/outer segment (IS/OS) junction), (3) eOS, and (4) RPE/BM complex. Assignment of reflectivity bands is based on Spaide and Curcio.12

Figure 4.

Pseudohypopyon stage (P7). With image registration, corresponding positions in the images (A–D) are shown as dashed vertical lines. (A) Fundus AF imaging reveals bright AF signal within the macular lesion that is much brighter than the surrounding retina. The AF material appears to settle inferiorly and puncta of enhanced intensity are also apparent. (B) Near-infrared reflectance gives the impression of a lesion with three-dimensionality. (C) In the color image the yellow material of the lesion gravitates somewhat inferiorly. (D) Spectral-domain OCT. Horizontal axis and extent of the scan are indicated by green arrow in (A). A dome-shaped lesion is revealed; the hyporeflective component is consistent with fluid accumulation. At the edge of the lesion, hyperreflective bands assignable to the OLM, ISe, and eOS exhibit an abrupt departure from their alignment with the RPE/BM and follow the upper contours of the lesion. Within the lesion, the eOS band is disorganized and has reduced reflectivity and the ONL is thinned. Immediately outside the AF border, the eOS band is thickened.

Figure 5.

Vitelliruptive stage (P1). With image registration, corresponding positions in the images (A–D) are shown as dashed vertical lines. (A) Fundus AF image. The center of the lesion appears mottled and of low AF and is surrounded by a thin ring of higher AF with intermittent small bright puncta (outer border indicated by dashed line). (B) Near-infrared reflectance emphasizes the contours of the lesion. (C) Color image. Multiple aggregates of yellowish material are visible in the central part of the lesion. These aggregates do not necessarily emit a high AF signal (compare with panel A). (D) Spectral-domain OCT. Horizontal axis and extent of the scan are indicated by green arrow in (A). The dome-shaped predominantly hyporeflective lesion is situated between reflective bands attributable to OLM and RPE/BM. The lesion interrupts the bands attributable to the ISe and eOS. Within the lesion, stalactite-like reflective material extends from above and mounds of reflective material settle below. The ONL thickness is severely reduced over the lesion. In the area that correlates with the higher AF ring, the eOS band is dissolving, and attenuated in intensity and appears thickened adjacent to the lesion. White arrows indicate area of increased choroidal reflectivity; this phenomenon is generally interpreted as a sign of RPE atrophy.

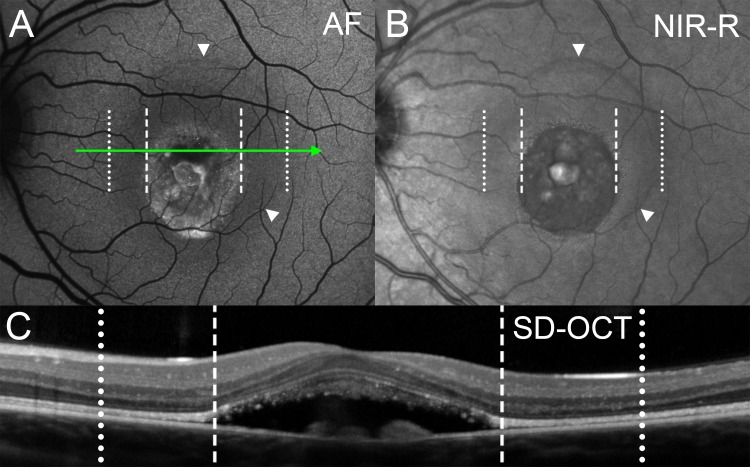

Figure 6.

Vitelliruptive stage (P3). With image registration, corresponding positions in the images (A–C) are shown as dotted and dashed vertical lines. (A) Fundus AF reveals a round central area with irregularly increased AF and intermittent small bright puncta. This area of increased AF is surrounded by a sharply delineated homogenous low AF halo (outer border indicated by white arrowheads). (B) On NIR-R a three-dimensional appearing circular blister with sharply defined borders is visible. The blister surrounds the vitelliruptive lesion and corresponds to the low AF halo in (A) (white arrowheads). (C) Spectral-domain OCT. Axis and horizontal extent of the scan are indicated by green arrow in (A). Spectral-domain OCT reveals a dome-shaped predominantly hyporeflective lesion located between the reflective bands attributable to OLM and RPE/BM. The ISe and eOS bands are interrupted. The ONL is thinned within the area of the blister-like lesion (between dotted and dashed lines).

On SD-OCT the vitelliform lesions were typically dome-shaped. Comparison of the AF and SD-OCT images indicated that the high AF signal originated from an area of separation between the hyperreflective bands attributable to the photoreceptor inner segment ellipsoid (ISe; band 2 in Fig. 3) and the RPE/BM complex (band 4 in Fig. 3). The latter is consistent with the lesion residing in subretinal space, as previously suggested.6,10,11 In the vitelliform stage (Fig. 3), the ISe band was intact but displaced toward the inner retina. In the pseudohypopyon stage (Fig. 4), the ISe and eOS bands were interrupted within the lesion and the eOS band was thickened at the margin of the lesion. By the vitelliruptive stage (Figs. 5–7), the lesion was predominantly hyporeflective centrally and here the AF signal was also diminished. Stalactite-like reflective material37 extended into the lesion from above, and mounds of reflective material were present at the RPE/BM surface. However, in some patients localized spots of high AF were present at the lesion border; these spots corresponded to hyperreflective material in SD-OCT images (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Structural correlates of a bright AF speck in vitelliruptive stage lesion of P6. (A) Fundus AF image. Autofluorescence in the lesion center is diminished except for a faint high AF band at the lesion border. Autofluorescence levels are the highest in a localized area at the inferior aspect of the lesion. (B) Spectral-domain OCT. Horizontal axis and extent of the scan are indicated by a green arrow in (A). Spectral-domain OCT reveals hyperreflective material between OLM and RPE/BM.

We noticed a low AF halo in two patients, P16 (right eye) and P3 (left eye; illustrated in Fig. 6); this halo exhibited a well-defined border on NIR-R and resembled a blister. This low AF halo surrounded the high AF lesion area and correlated with thinning of the outer nuclear layer (ONL) on SD-OCT. Without corroborating NIR-R imaging, the low AF halo in AF images may be difficult to distinguish from the normal distribution of macular pigment and/or the area of higher RPE melanin.

Quantitative Fundus Autofluorescence (qAF)

Quantitative AF images were obtained from 27 eyes of the 16 BVMD patients. Quantitative AF was measured in two rings (middle and inner), each consisting of eight circularly arranged segments (Fig. 1). Segments that did not overlap with the high AF lesion were used for nonlesion measurements. In all BVMD eyes, nonlesion qAF was within normal limits (95% confidence interval [CI]) for age and race/ethnicity (Fig. 8). Among the BVMD patients, qAF increased with age (mixed-effects regression, P < 0.001); this age-related increase was the same for BVMD and healthy eyes30 (P = 0.7), and also when corrected for race/ethnicity (P = 0.6). There was no difference in the nonlesion qAF between eyes in the subclinical stage and later disease stages when corrected for age (P = 0.4).

Figure 8.

Quantitative fundus autofluorescence. Mean nonlesion qAF of the middle ring (panel A and C) and the inner ring (panel B and D) are plotted as a function of age for white (A, B) and Hispanic/black (C, D) BVMD patients. Rings are defined in Figure 1. Pairs of eyes are presented as triangles, right eyes (OD), and circles, left eyes (OS). Eyes in the subclinical stage are marked with a white cross. The arrow in (C) indicates OD and OS values for a single black patient. Nonlesion qAF levels for BMVD eyes are plotted together with mean (solid line) and 95% CI (dashed lines) of healthy subjects.

Maximum lesion qAF levels (mean ± SD) measured in a 26 × 26 pixel area, were 557 ± 5 and 760 ± 3 qAF units, respectively, for the right and left eye of P7 (age: 5 years, pseudohypopyon stage); 274 ± 9 and 329 ± 10 qAF units, respectively, for the right and left eye of P10 (age: 33 years, central lesion of multifocal vitelliform); and 113 ± 4 qAF units for the left eye of P14 (age: 14 years, vitelliform stage). These levels were more than 23 (P7, P < 0.001), 2.2 (P10, P = 0.04), and 1.4 (P14, P = 0.2) times higher than the mean qAF inside the inner ring for healthy subjects of the same age and race/ethnicity (data not shown).

For nonlesion qAF measured in the middle ring of right and left eyes, the Bland-Altman coefficient of agreement was 19.2%. We measured the between-session Bland-Altman coefficient of repeatability in 10 eyes of 6 patients. The intersession coefficient of repeatability was ±7.0% (95% CI).

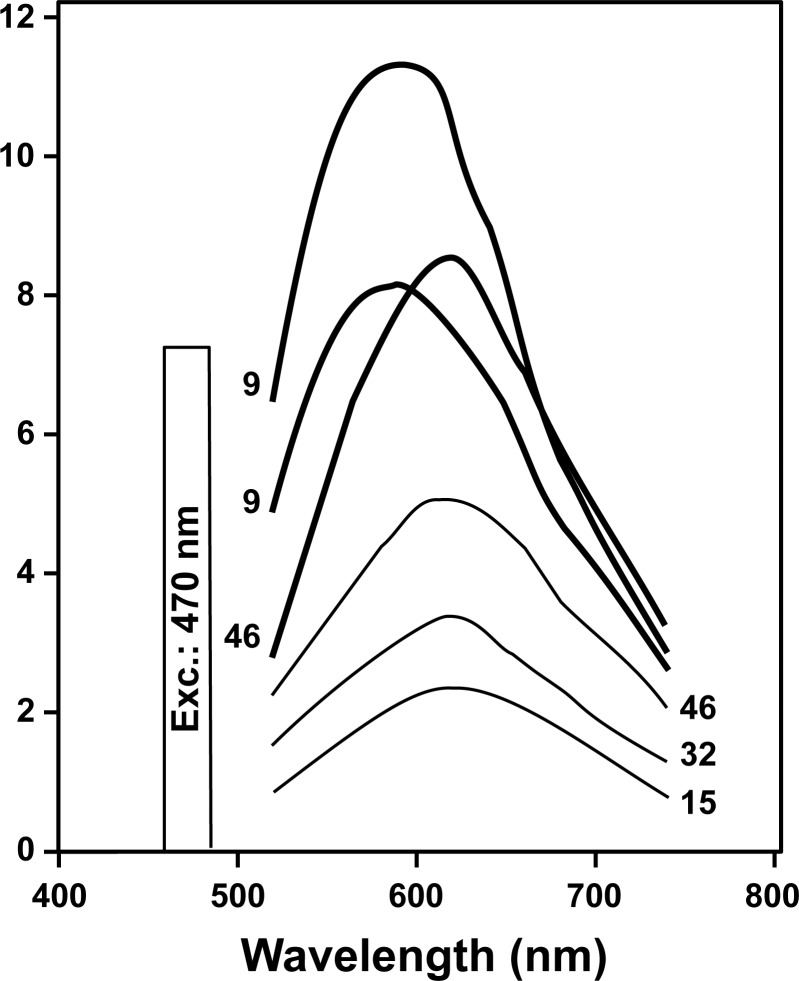

Spectrofluorometry

The shapes of the emission spectra recorded within the vitelliform lesions of BVMD patients were consistent with emission spectra of lipofuscin recorded spectrofluorometrically in healthy eyes (Fig. 9). In all cases emission maxima were at 580 to 620 nm.

Figure 9.

Fluorescence emission spectra measured within the BVMD vitelliform lesion in three patients (thick lines) as compared with the fundus autofluorescence of three healthy eyes (thin lines). Ages of the subjects are indicated for each spectrum. These data were obtained by noninvasive spectrofluorometry with an excitation of 470 nm and were corrected for ocular media absorption. Arbitrary units, A.U.

SD-OCT Segmentation

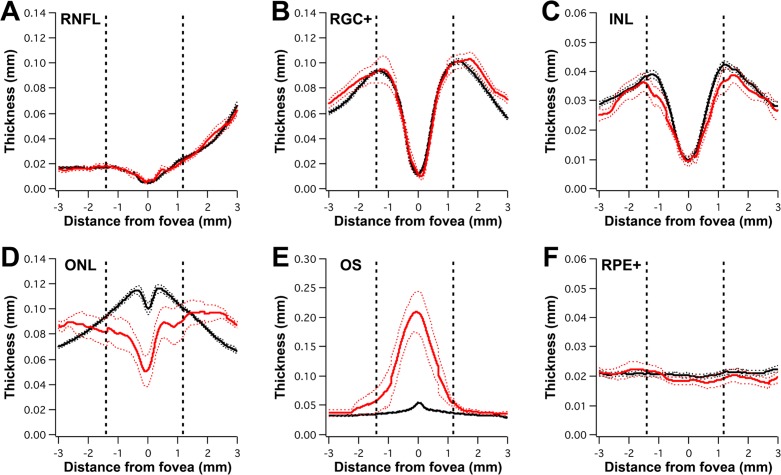

Figure 10 shows the thickness profiles (mean and 95% CI) of BVMD patients with a lesion (red profiles) compared with healthy controls (black profiles). The dashed vertical lines indicate the average position of the lesion across all BVMD patients; the latter position was defined by AF (as described in the Multimodal Imaging section). Abnormalities in retinal thickness were limited to the outer retina; inner retinal layers (RNFL, RGC+, and INL) were within normal limits throughout the retina. The ONL thickness was decreased in the lesion area and appeared to be increased outside the lesion border. The OS layer was thickened within the lesion. This thickening was due, at least in part, to the subretinal fluid and extended outside the lesion border. Based on the cohort average, the RPE+ thickness was within normal limits throughout the retina.

Figure 10.

Averaged thickness profiles of inner and outer retinal layers in BVMD patients exhibiting a lesion. Mean thickness ±95% CIs for BVMD patients and controls are shown as red and black profile lines, respectively. Profiles are displayed as if all eyes are right eyes. Positive values on x-axis indicate nasal direction. Dashed vertical lines represent average position of the lesion, which has been defined by AF. Inner retinal layer thicknesses are within normal limits (A–C). (D) Outer nuclear layer thickness is reduced within the lesion and appears thickened outside the lesion. (E) Outer segment thickness is increased within the lesion and in a transition zone outside the lesion. (F) The RPE+ thickness is within normal limits across the cohort.

Figure 11 shows the individual thickness profiles of six subclinical BVMD patients, which were within the 95% CI (thin black lines) of the controls.

Figure 11.

Thickness profiles of subclinical BVMD patients. Profile lines of the six patients are shown (colored lines) relative to mean ±95% CIs of controls (black lines). P4 is shown in pink, P5 in purple, P8 in blue, P9 in green, P13 in orange, and P15 in red. Positive values on x-axis indicate nasal direction. Thicknesses of ONL (A), OS (B), and RPE+ (C) appear to be within normal limits.

Discussion

Quantitative fundus AF in BVMD revealed that fundus areas outside the central lesion do not exhibit increased lipofuscin levels. Within the fluid-filled lesion, qAF levels were elevated compared with corresponding fundus areas in age-similar controls. In our cohort, the patient in the pseudohypopyon stage exhibited higher lesion qAF levels than the two patients in the vitelliform stage. Emission spectra recorded at the fundus in BVMD patients exhibited maxima at 580 to 620 nm, these maxima are similar to that recorded in healthy eyes (Fig. 9), in recessive Stargardt disease38 and in AMD.39 Spectral-domain OCT segmentation demonstrated that abnormalities in outer retinal thickness correspond to the lesion visualized by AF imaging. However, there was a transition zone outside the lesion wherein the eOS band was thickened and in rare cases a low AF halo was present outside the lesion which correlated with ONL thinning. Thickness measurements for subclinical BVMD patients were within normal limits.

The question as to whether BVMD is a panretinal disorder or whether the gene mutation causes only a focal effect has long been debated. The EOG change observed with BVMD can only be detected if a wide area of retina is affected. Additionally, monitoring by OCT has demonstrated that the increase in photoreceptor outer segment equivalent length observed upon light adaptation in BVMD patients is observed across the fundus.40 Nevertheless, in most cases the ophthalmoscopically visible lesion is limited to the macula and abnormal multifocal electroretinograms (mfERGs) correspond precisely to the area of the lesion.41 Recent findings from adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy have also indicated that photoreceptor cells are normal in areas immediately adjacent to clinically visible lesion.42 Thus, an abnormality of the nonlesion retina is not obvious. Optical coherence tomography studies of BVMD patients have yielded differing viewpoints on the intactness of the RPE/Bruch's membrane.11,43 Our segmentation data indicated that in the case of our cohort RPE/Bruch's membrane when averaged was within normal limits, even within the lesion. However, as shown in Figure 5, we cannot exclude RPE thinning in advanced cases. Our segmentation data also indicated that there was an apparent thickening of the ONL outside the lesioned area. If real, this would be another example of a thickening of the ONL in a retinal degenerative disease.44

Regarding the predilection of BVMD for the macula, it has been reported that immunohistochemical staining together with quantitative PCR and immunoblotting indicated that bestrophin-1 expression was more robust in the peripheral retina than in the macula.22 Unique environmental stresses imposed upon macular RPE have been proposed as an alternative explanation.21 Interestingly, in canines, several coding changes in the canine BEST1 are associated with a recessive disease featuring multifocal areas of fluid-filled retinal elevations similar to human BVMD.45,46

The light peak (LP) of the EOG is generated by a Ca2+-dependent outward Cl− conductance across the basal membrane of RPE.9 Bestrophin-1 is a membrane protein expressed basolaterally in the RPE, but a large proportion of the protein is found in association with cytosolic membrane where it may serve as an anion channel.2,47–49 Most investigations have shown that mutations in bestrophin-1 result in a loss of anion channel conductance.50–52 Nevertheless, the role of BEST1 in mediating the LP has been difficult to elucidate and mouse models have not faithfully replicated BEST1-related disease in humans.53,54 Several channel functions have been assigned to bestrophin-1 (Ca2+-activated Cl−, Ca2+ channel regulator, volume regulated Cl−, and HCO3−).50,55–58 Because of osmotic forces, the efflux of both Cl− and HCO3− across the basolateral membrane of RPE is followed by fluid transport from the subretinal space to the choroid.59 Thus, failure of fluid transport in the presence of a BEST1 mutation is likely the cause of the fluid-filled neural retinal detachment. Accordingly, disrupted fluid flux has been observed in a human-induced pluripotent stem cell model of BVMD.21 The ionic milieu of photoreceptor cell outer segments is also presumably altered in BVMD, resulting in not only an accumulation of fluid but also outer segment debris. The retinal detachment created by the accumulation of fluid likely interferes with the phagocytosis of shed outer segment membranes, which therefore accumulate subretinally. Thus, much or all of the vitelliform material probably originates from unphagocytosed outer segment membrane in the subretinal fluid responsible for the detachment. Since the bisretinoid fluorophores of RPE lipofuscin originate from outer segments, these bisretinoids and bisretinoid precursors in the outer segment could be the source of the AF. The spectrofluorometric data presented here are consistent with these views. Even then however, the fluorescence is particularly bright, much brighter than the lipofuscin in surrounding RPE. Thus, in addition to impeded removal of outer segment debris, the possibility remains that the rate of bisretinoid formation in the photoreceptor outer segments is accelerated.60 Eventual loss of the fluorescence associated with the lesion could involve clearance of the subretinal photoreceptor cell debris perhaps by macrophages, in addition to photodegradation of the fluorophores. It is perhaps the yellow color and autofluorescence of the vitelliform material in combination with uncertainty as to the structural correlates of the lesion that lead to the assumption that RPE lipofuscin accumulation is increased throughout the fundus in BVMD. Based on our findings, we suggest that increased RPE lipofuscin is not a feature of the primary disease process; however, the increased AF levels originating from degenerating outer segments in the lesion could be an additional source of damage.

Hyperopia and short axial length are characteristic findings in autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy (ARB), a condition in which patients by definition carry a BEST1 mutation on both chromosomes,61 and it has been suggested that functional bestrophin-1 may be required for the development of the eye.3,61,62 The cohort in this study was also hyperopic and had a short axial length (Table). These phenotypical features may therefore be characteristic not only of ARB but also of autosomal dominant BVMD. Previous studies have reported short axial length and a subsequently increased risk for angle-closure glaucoma in three BVMD families.63,64

Patient 10 had a clinical diagnosis of multifocal BVMD, but no mutation in BEST1 was found and there was no clear evidence of a positive family history of BVMD. We can therefore not exclude the possibility that this patient may have been misdiagnosed or represent a phenocopy of BVMD.65

In summary, qAF revealed that mutations in BEST1 do not cause increased lipofuscin levels in nonlesion fundus areas. Spectral-domain OCT segmentation demonstrated characteristic structural abnormalities within the lesion and at a transition zone outside the lesion. Subclinical cases displayed no obvious changes. These findings inform our understanding of the pathogenesis and clinical findings of BVMD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Graeme C.M. Black (Department of Medical Genetics, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK) and members of Rando Allikmets' laboratory at Columbia University who carried out the molecular genetic analysis of patients.

Supported in part by grants from the National Eye Institute/National Institutes of Health (EY015520, EY019007, EY009076, EY024091, EY021163, EY08511), Foundation Fighting Blindness, New York City Community Trust, Roger H. Johnson Fund (University of Washington, Seattle), and a grant from Research to Prevent Blindness to the Department of Ophthalmology, Columbia University.

Disclosure: T. Duncker, None; J.P. Greenberg, None; R. Ramachandran, None; D.C. Hood, None; R.T. Smith, None; T. Hirose, None; R.L. Woods, None; S.H. Tsang, None; F.C. Delori, None; J.R. Sparrow, None

References

- 1. Petrukhin K, Koisti MJ, Bakall B, et al. Identification of the gene responsible for Best macular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1998; 19: 241–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marmorstein AD, Marmorstein LY, Rayborn M, Wang X, Hollyfield JG, Petrukhin K. Bestrophin, the product of the Best vitelliform macular dystrophy gene (VMD2), localizes to the basolateral plasma membrane of the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000; 97: 12758–12763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boon CJ, Klevering BJ, Leroy BP, Hoyng CB, Keunen JE, den Hollander AI. The spectrum of ocular phenotypes caused by mutations in the BEST1 gene. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009; 28: 187–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boon CJ, Klevering BJ, den Hollander AI, et al. Clinical and genetic heterogeneity in multifocal vitelliform dystrophy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007; 125: 1100–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mullins RF, Oh KT, Heffron E, Hageman GS, Stone EM. Late development of vitelliform lesions and flecks in a patient with best disease: clinicopathologic correlation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005; 123: 1588–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spaide RF, Noble K, Morgan A, Freund KB. Vitelliform macular dystrophy. Ophthalmol. 2006; 113: 1392–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Renner AB, Tillack H, Kraus H, et al. Late onset is common in best macular dystrophy associated with VMD2 gene mutations. Ophthalmology. 2005; 112: 586–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deutman AF. Electro-oculography in families with vitelliform dystrophy of the fovea. Detection of the carrier state. Arch Ophthalmol. 1969; 81: 305–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gallemore RP, Hughes BA, Miller SS. Light-Induced Responses of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium. New York City: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ferrara D, Costa R, Tsang S, Calucci D, Jorge R, Freund K. Multimodal fundus imaging in Best vitelliform macular dystrophy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010; 248: 1377–1386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Querques G, Regenbogen M, Quijano C, Delphin N, Soubrane G, Souied EH. High-definition optical coherence tomography features in vitelliform macular dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008; 146: 501–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spaide RF, Curcio CA. Anatomical correlates to the bands seen in the outer retina by optical coherence tomography. Literature review and model. Retina. 2011; 31: 1609–1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Srinivasan VJ, Monson BK, Wojtkowski M, et al. Characterization of outer retinal morphology with high-speed, ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 1571–1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Querques G, Zerbib J, Santacroce R, et al. The spectrum of subclinical Best vitelliform macular dystrophy in subjects with mutations in BEST1 gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 4678–4684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frangieh GT, Green R, Fine SL. A histopatholgic study of Best's macular dystrophy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982; 100: 1115–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weingeist TA, Kobrin JL, Watzke RC. Histopathology of Best's macular dystrophy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982; 100: 1108–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. O'Gorman S, Flaherty WA, Fishman GA, Berson EL. Histopathological findings in Best's vitelliform macular dystrophy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988; 106: 1261–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang Q, Small KW, Grossniklaus HE. Clinicopathologic findings in Best vitelliform macular dystrophy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011; 249: 745–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bakall B, Radu RA, Stanton JB, et al. Enhanced accumulation of A2E in individuals homozygous or heterozygous for mutations in BEST1 (VMD2). Exp Eye Res. 2007; 85: 34–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vedantham V, Ramasamy K. Optical coherence tomography in Best's disease: an observational case report. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005; 139: 351–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Singh R, Shen W, Kuai D, et al. iPS cell modeling of Best disease: insights into the pathophysiology of an inherited macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2013; 22: 593–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mullins RF, Kuehn MH, Faidley EA, Syed NS, Stone EM. Differential macular and peripheral expression of bestrophin in human eyes and its implication for Best disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48: 3372–3380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Delori FC, Dorey CK, Staurenghi G, Arend O, Goger DG, Weiter JJ. In vivo fluorescence of the ocular fundus exhibits retinal pigment epithelium lipofuscin characteristics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995; 36: 718–729 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. von Ruckmann A, Fitzke FW, Bird AC. In vivo fundus autofluorescence in macular dystrophies. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997; 115: 609–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lois N, Halfyard AS, Bird AC, Fitzke FW. Quantitative evaluation of fundus autofluorescence imaged “in vivo” in eyes with retinal disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000; 84: 741–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Preising M. Fundus autofluorescence in Best disease. In: Lois N, Forrester JV. eds Fundus Autofluorescence. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009: 197–205 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Delori F, Greenberg JP, Woods RL, et al. Quantitative measurements of autofluorescence with the scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 9379–9390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marmor MF, Brigell MG, McCulloch DL, Westall CA, Bach M. ISCEV standard for clinical electro-oculography (2010 update). Doc Ophthalmol. 2011; 122: 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gass JDM. Stereoscopic Atlas of Macular Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Greenberg JP, Duncker T, Woods RL, Smith RT, Sparrow JR, Delori FC. Quantitative fundus autofluorescence in healthy eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 5684–5693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen J, Tian J, Lee N, Zheng J, Smith RT, Laine AF. A partial intensity invariant feature descriptor for multimodal retinal image registration. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2010; 57: 1707–1718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van de Kraats J, van Norren D. Optical density of the aging human ocular media in the visible and the UV. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2007; 24: 1842–1857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Delori FC, Goger DG, Dorey CK. Age-related accumulation and spatial distribution of lipofuscin in RPE of normal subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001; 42: 1855–1866 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986; 1: 307–310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hood DC, Lin CE, Lazow MA, Locke KG, Zhang X, Birch DG. Thickness of receptor and post-receptor retinal layers in patients with retinitis pigmentosa measured with frequency-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 2328–2336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hood DC, Cho J, Raza AS, Dale EA, Wang M. Reliability of a computer-aided manual procedure for segmenting optical coherence tomography scans. Optom Vis Sci. 2011; 88: 113–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Borman AD, Davidson AE, O'Sullivan J, et al. Childhood-onset autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011; 129: 1088–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Delori FC, Staurenghi G, Arend O, Dorey CK, Goger DG, Weiter JJ. In vivo measurement of lipofuscin in Stargardt's disease–Fundus flavimaculatus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995; 36: 2327–2331 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Arend O, Weiter JJ, Goger DG, Delori FC. In vivo fundus fluorescence measurements in patients with age related macular degeneration [in German]. Ophthalmologe. 1995; 92: 647–653 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abramoff MD, Mullins RF, Lee K, et al. Human photoreceptor outer segments shorten during light adaptation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 3721–3728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Glybina IV, Frank RN. Localization of multifocal electroretinogram abnormalities to the lesion site: findings in a family with Best disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006; 124: 1593–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kay DB, Land ME, Cooper RF, et al. Outer retinal structure in best vitelliform macular dystrophy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013; 131: 1207–1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kay CN, Abramoff MD, Mullins RF, et al. Three-dimensional distribution of the vitelliform lesion, photoreceptors, and retinal pigment epithelium in the macula of patients with best vitelliform macular dystrophy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012; 130: 357–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sadigh S, Cideciyan AV, Sumaroka A, et al. Abnormal thickening as well as thinning of the photoreceptor layer in intermediate age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 1603–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Guziewicz KE, Zangerl B, Lindauer SJ, et al. Bestrophin gene mutations cause canine multifocal retinopathy: a novel animal model for best disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48: 1959–1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zangerl B, Wickström K, Slavik J, et al. Assessment of canine BEST1 variations identifies new mutations and establishes an independent bestrophinopathy model (cmr3). Mol Vis. 2010; 16: 2791–2804 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barro-Soria R, Aldehni F, Almaca J, Witzgall R, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K. ER-localized bestrophin 1 activates Ca2+-dependent ion channels TMEM16A and SK4 possibly by acting as a counterion channel. Pflugers Arch. 2010; 459: 485–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gomez NM, Tamm ER, Straubeta O. Role of bestrophin-1 in store-operated calcium entry in retinal pigment epithelium. Pflugers Arch. 2013; 465: 481–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Neussert R, Muller C, Milenkovic VM, Strauss O. The presence of bestrophin-1 modulates the Ca2+ recruitment from Ca2+ stores in the ER. Pflugers Arch. 2010; 460: 163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sun H, Tsunenari T, Yau KW, Nathans J. The vitelliform macular dystrophy protein defines a new family of chloride channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002; 99: 4008–4013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yu K, Qu Z, Cui Y, Hartzell HC. Chloride channel activity of bestrophin mutants associated with mild or late-onset macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48: 4694–4705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hartzell HC, Qu Z, Yu K, Xiao Q, Chien LT. Molecular physiology of bestrophins: multifunctional membrane proteins linked to best disease and other retinopathies. Physiol Rev. 2008; 88: 639–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang Y, Stanton JB, Wu J, et al. Suppression of Ca2+ signaling in a mouse model of Best disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2010; 19: 1108–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Marmorstein LY, Wu J, McLaughlin P, et al. The light peak of the electroretinogram is dependent on voltage-gated calcium channels and antagonized by bestrophin (best-1). J Gen Physiol. 2006; 127: 577–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Qu Z, Hartzell HC. Bestrophin Cl- channels are highly permeable to HCO3-. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008; 294: C1371–C1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xiao Q, Hartzell HC, Yu K. Bestrophins and retinopathies. Pflugers Arch. 2010; 460: 559–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rosenthal R, Bakall B, Kinnick T, et al. Expression of bestrophin-1, the product of the VMD2 gene, modulates voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in retinal pigment epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2006; 20: 178–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fischmeister R, Hartzell HC. Volume sensitivity of the bestrophin family of chloride channels. J Physiol. 2005; 562: 477–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Adijanto J, Banzon T, Jalickee S, Wang NS, Miller SS. CO2-induced ion and fluid transport in human retinal pigment epithelium. J Gen Physiol. 2009; 133: 603–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sparrow JR, Yoon K, Wu Y, Yamamoto K. Interpretations of fundus autofluorescence from studies of the bisretinoids of retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51: 4351–4357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Boon CJ, van den Born LI, Visser L, et al. Autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy: differential diagnosis and treatment options. Ophthalmology. 2013; 120: 809–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yardley J, Leroy BP, Hart-Holden N, et al. Mutations of VMD2 splicing regulators cause nanophthalmos and autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004; 45: 3683–3689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Low S, Davidson AE, Holder GE, et al. Autosomal dominant Best disease with an unusual electrooculographic light rise and risk of angle-closure glaucoma: a clinical and molecular genetic study. Mol Vis. 2011; 17: 2272–2282 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wittström E, Ponjavic V, Bondeson ML, Andréasson S. Anterior segment abnormalities and angle-closure glaucoma in a family with a mutation in the BEST1 gene and Best vitelliform macular dystrophy. Ophthalmic Genet. 2011; 32: 217–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kramer F, White K, Pauleikhoff D, et al. Mutations in the VMD2 gene are associated with juvenile-onset vitelliform macular dystrophy (Best disease) and adult vitelliform macular dystrophy but not age-related macular degeneration. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000; 8: 286–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]