Abstract

Progesterone and other progestagens are used in combination with estrogens for clinical purposes, including contraception and postmenopausal hormone therapy. Progesterone and estrogens have interactive effects in brain, however interactions between synthetic progestagens and 17β-estradiol (E2) in neurons are not well understood. In this study, we investigated the effects of seven clinically relevant progestagens on estrogen receptor (ER) mRNA expression, E2-induced neuroprotection, and E2-induced BDNF mRNA expression. We found that medroxyprogesterone acetate decreased both ERα and ERβ expression and blocked E2-mediated neuroprotection and BDNF expression. Conversely, levonorgestrel and nesterone increased ERα and or ERβ expression, were neuroprotective, and failed to attenuate E2-mediated increases in neuron survival and BDNF expression. Other progestagens tested, including norethindrone, norethindrone acetate, norethynodrel, and norgestimate, had variable effects on the measured endpoints. Our results demonstrate a range of qualitatively different actions of progestagens in cultured neurons, suggesting significant variability in the neural effects of clinically utilized progestagens.

Keywords: Progestagen, oestrogen receptor, neuroprotection, BDNF

1. Introduction

Because the use of unopposed estrogens in hormone therapy (HT) can exert undesired effects in endometrial tissue such as hyperplasia, HT typically includes progesterone (P4) or synthetic progestagens along with estrogens to minimize deleterious estrogen actions (Sitruk-Ware, 2002a, 2002b). Many of these synthetic progestagens have been used extensively as oral contraceptives and their functions in the reproductive system are well established (Brinton et al., 2008, Gonzalez Deniselle et al., 2007, Schumacher, 2007a, 2007b). However, comparatively little is known about the neuronal effects of synthetic progestagens, an important consideration given the numerous beneficial effects of estrogens and P4 in brain especially in the context of cognition and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

In the nervous system, P4 induces a range of neuroprotective and neurotrophic actions (reviewed in (Brinton et al., 2008, De Nicola et al., 2009, Sayeed and Stein, 2009, Schumacher, 2007b, Stein and Wright, 2010). For example, P4 is protective against glutamate excitotoxicity in neurons (Nilsen and Brinton, 2002), against cortical and hippocampal injuries in certain animal models (Alkayed et al., 2000, Brinton et al., 2008, Roof et al., 1994), and can reduce neuronal injury and increase neuron viability following traumatic brain injury (Roof et al., 1994, Stein, 2008). Neuroprotective effects of P4 are also observed in models of seizure and spinal cord injury (Labombarda et al., 2003, Rhodes and Frye, 2004). In the peripheral nervous system, P4 plays an important therapeutic role in myelin repair (for review see (Schumacher, 2007b, Schumacher et al., 2008).

In addition to direct beneficial actions, P4 is known to interact positively with neural actions of the primary estrogen 17β-estradiol (E2). For example, ovariectomized rats treated with E2 and P4 show improved water maze performance and increased neuroprotection in comparison to controls (Frye and Vongher, 1999a, 1999b). In rat hippocampal neuron cultures, pretreatment with P4 alone or in combination with E2 is neuroprotective against glutamate toxicity (Nilsen and Brinton, 2002, Rosario, 2006). Previous studies from our lab have suggested a cyclic regimen of P4 along with E2 to be beneficial in reducing levels of the AD-associated protein β-amyloid (Carroll et al., 2007) perhaps via regulating expression of insulin-degrading enzyme (Jayaraman et al., 2012).

An accumulating body of research demonstrates that, as in the endometrium, P4 can block some E2 actions in brain. For example, P4 treatment can largely prevent E2-induced increases of anti-apoptotic factors and neurotrophins (Aguirre et al., 2010, Bimonte-Nelson, 2004, Garcia-Segura, 1998) as well as E2-mediated neuroprotection against excitotoxicity (Rosario, 2006) and Aβ accumulation (Carroll et al., 2007). P4 can also block E2-mediated increases in CREB phosphorylation and spine density when co-administered with E2 (Murphy and Segal, 1996, 2000). Previously, we have shown that P4 antagonizes E2 actions in cultured neurons by decreasing the expression and function of estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ. We also showed that this decrease in ER expression and function affects E2-mediated neuroprotection (Jayaraman and Pike, 2009).

While recent research continues to define neural interactions between E2 and P4, relatively little is known about how synthetic progestagens affect neurons both alone and in the presence of E2. In this study, we evaluate neuronal effects of the following seven clinically relevant synthetic progestagens: medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), norethindrone (NET), norethindrone acetate (NETA), norethynodrel, levonorgestrel (LNG), norgestimate (NGM), and nesterone (NEST). We investigate the effects of these progestagens on ER expression and E2-mediated neuroprotection against apoptosis in primary neuron cultures. We also determine the effects of these progestagens on E2-induced mRNA expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Reagents

Progesterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethindrone, norethindrone acetate, norethynodrel, levonorgestrel, norgestimate, and 17β-estradiol were purchased from Steraloids (Newport, RI, USA). Nesterone was a kind gift from Dr. Sitruk-Ware (Rockefeller University and Population Council, NY, USA). RU486 (mifepristone) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (St. Louis, MO, USA). All hormones were dissolved in ethanol and diluted in culture medium to a final ethanol concentration of <0.01%. Apoptosis Activator II (AAII), a cell-permeable cytochrome-c-dependent caspase activator, was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA).

2.2 Primary neuron culture

All experimental animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institute of Health guidelines under a protocol approved by the University of Southern California. Primary rat cerebrocortical cultures (approximately 95% neuronal) were prepared from embryonic day 17 Sprague-Dawley rat pups (N>6 pups per preparation) using a previously described protocol (Cordey et al., 2003). In brief, cortices were enzymatically dissociated using 0.25% trypsin at 37°C for 5 min. The reaction was then quenched using 2 volumes of phenol-red free Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) containing 10% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum. The tissue suspensions were centrifuged, resuspended and mechanically dissociated using flame-polished glass Pasteur pipettes, then filtered through 40μm cell strainers (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The resultant cell suspensions were diluted into phenol-red free DMEM containing N2 supplement (without P4) to a final plating density of 2.5 × 104 cells/cm2 (for cell viability assays) and 8 × 105 cells/cm2 (for RNA isolations). Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator supplemented with 5% CO2. All experiments were started 1–2 days after plating and were repeated with three to five independent culture preparations.

2.3 RNA isolation and RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from cultures using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Corporation; Carlsbad, CA) and processed for total RNA extraction as per manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA (1–2 μg) was used for reverse transcription using the Superscript™ First strand synthesis system (Invitrogen) as previously described (Jayaraman and Pike, 2009) and the resulting cDNA was used for both standard PCR and real-time quantitative PCR amplifications. Quantitative PCR was carried out using a DNA Engine Opticon 2 continuous fluorescence detector (MJ Research Inc; Waltham, MA). The amplification efficiency was estimated from the standard curve for each gene. Relative quantification of mRNA levels from various treated samples was determined by the comparative Ct method (also known as ΔΔCt method) (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The statistical analyses were performed on the final fold change calculations (2−ΔΔCT) (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008). The following primer pairs were used – ERα, forward: 5′CATCGATAAGAACCGGAG3′, Reverse: 5′AAGGTTGGCAGCTCTCAT3′; ERβ, Forward: 5′AAAGTAGCCGGAAGCTGA3′, Reverse:5′CTCCAGCAGCAGGTCATA3′; BDNF, Forward:5′GAGCCTCCTCTGCTCTTTCTGCTGGAG3′, Reverse:5′CTTTTGTCTATGCCCCTGCAGCCTTCC3′; β-actin, Forward: 5′AGCCATGTACGTAGCCATCC3′; Reverse: 5′CTCTCAGCTGTGGTGGTGAA3′.

2.4 Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed by counts of viable cells as determined by staining with the vital dye calcein acetoxymethyl ester (Invitrogen), as previously described (Nguyen et al., 2010). In brief, cultures were incubated for 5 min with 2 μM calcein acetoxymethyl ester then examined using an inverted fluorescent IX70 Olympus microscope. The number of positively stained cells with regular, spherical shape was counted in four 300X fields (in a predetermined, regular pattern) per well, three wells per condition in each experiment (N ≥ 3 independent culture preparations). Numbers of viable neurons in vehicle-treated controls ranged from 200–250 per well.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Raw data from quantitative PCR and cell viability experiments were statistically assessed using ANOVA followed by between group comparisons using Fisher’s LSD test. Statistical significance was indicated by P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of progestagens on ERα mRNA expression

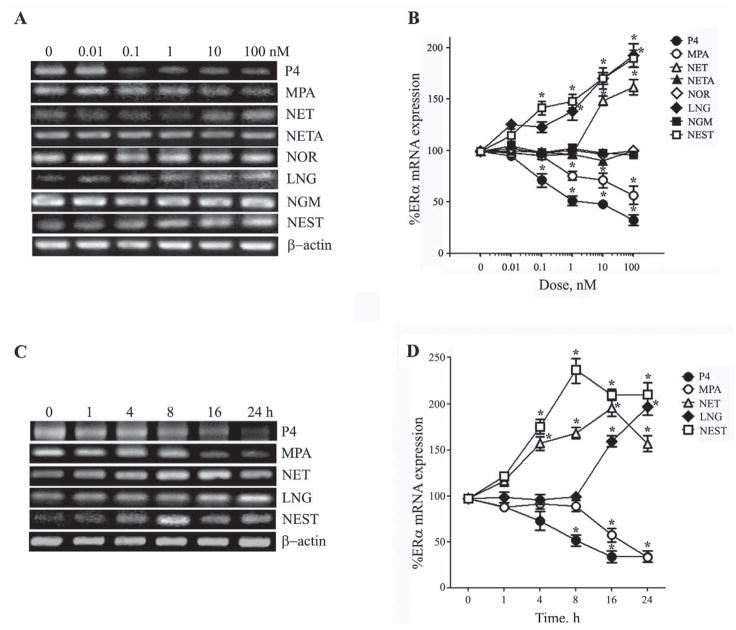

To investigate the effects of synthetic progestagens on ERα mRNA expression, neuronal cultures were treated for 24 h with increasing concentrations (0 – 100 nM) of individual synthetic progestagens. The cells were then harvested for RNA isolation and analyzed by RT-PCR and QPCR using ERα-specific primers. Consistent with our prior observations (Jayaraman and Pike, 2009), we observed that P4 at concentrations ≥ 0.1 nM significantly reduced ERα mRNA levels with nearly 70% reduction at the highest examined concentration of 100 nM (Fig. 1 A,B). In comparison, MPA was the only synthetic progestagen observed to also significantly reduce ERα mRNA. The progestagens NETA, NOR, and NGM did not significantly affect ERα transcript levels. In contrast, NET, LNG, and NEST increased ERα mRNA expression to maximum levels between 1.5 – 2 fold above those observed in vehicle-treated control cultures (Fig. 1A, B).

Figure 1. Progestagens regulate ERα mRNA expression in concentration and time-dependent manners.

(A) Representative agarose gel of RT-PCR products qualitatively show relative changes in mRNA levels of the ERα induced by 24 h exposure to 0 – 100 nM of progestagens. β-actin was used as an internal control. (B) The relative levels of ERα after treatment with increasing progestagen concentrations were also determined quantitatively using real-time PCR. Data show the mean (±SEM) expression levels, relative to vehicle-treated controls after normalizing with corresponding values of β-actin. Representative agarose gel of RT-PCR (C) and quantitative graph from real-time PCR (D) shows changes in levels of ERα mRNA induced by 0 – 24 h exposure to 10 nM progestagens. Statistical significance is based on analysis of pooled raw data using ANOVA followed by the Fisher LSD. * P≤0.05 relative to corresponding vehicle-treated control group.

To evaluate the time course of the observed effects of progestagens on ERα mRNA levels, neuron cultures were treated with 10 nM of P4, MPA, NET, LNG, or NEST for 1, 4, 8, 16, and 24 h, then processed as described above. Our results show that decreases in ERα mRNA induced by P4 and MPA became significant within 8 h and 16 h of treatment, respectively (Fig. 1C, D). Conversely, ERα mRNA was increased to significant levels within 4 h of treatment with NET and NEST and by 16 h following LNG exposure (Fig. 1C, D).

3.2. Effects of progestagens on ERβ mRNA expression

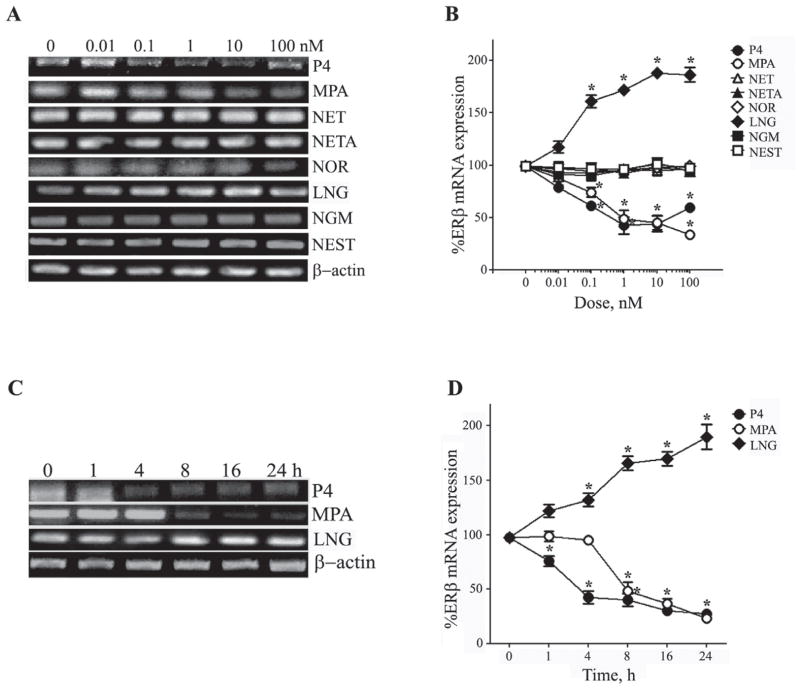

The effects of synthetic progestagens on ERβ expression were assessed in parallel to the analysis of ERα. We observed that P4 at concentrations ≥ 0.1 nM significantly reduced ERβ mRNA levels (Fig. 2 A, B). Similar to the results seen with ERα mRNA, MPA was the only synthetic progestagen observed to also significantly reduce ERβ mRNA. The progestagens NET, NETA, NOR, NGM, and NEST did not significantly affect ERβ transcript levels. In contrast, LNG increased ERβ mRNA expression to maximum levels almost 2 fold above those observed in vehicle-treated control cultures (Fig. 2A, B).

Figure 2. Progestagens regulate ERβ mRNA expression in concentration and time-dependent manners.

(A) Representative agarose gel of RT-PCR products qualitatively show relative changes in mRNA levels of the ERβ induced by 24 h exposure to 0 – 100 nM of progestagens. β-actin was used as an internal control. (B) The relative levels of ERβ after treatment with increasing progestagen concentrations were also determined quantitatively using real-time PCR. Data show the mean (±SEM) expression levels, relative to vehicle-treated controls after normalizing with corresponding values of β-actin. Representative agarose gel of RT-PCR (C) and quantitative graph from real-time PCR (D) shows changes in levels of ERβ mRNA induced by 0 – 24 h exposure to 10 nM progestagens. Statistical significance is based on analysis of pooled raw data using ANOVA followed by the Fisher LSD. * P≤0.05 relative to corresponding vehicle-treated control group.

To evaluate the time course of the observed effects on progestagens on ERβ mRNA levels, neuron cultures were treated with 10 nM of P4, MPA, or LNG, for 1, 4, 8, 16, and 24 h, then processed as described above. Our results show that decreases in ERβ mRNA induced by P4 and MPA became significant within 1 h and 8 h of treatment, respectively (Fig. 2C, D). Conversely, ERβ mRNA was increased to significant levels within 4 h of treatment with LNG (Fig. 2C, D).

3.3. Effects of progestagens against apoptosis and estradiol-induced protection

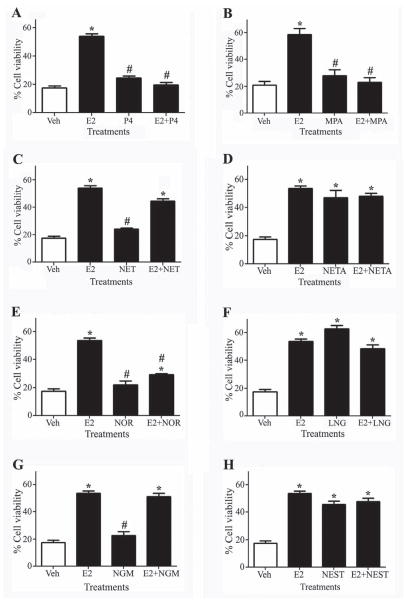

The effects of the progestagens on apoptosis and their interactions with E2-mediated neuroprotection against apoptosis were studied in cultured neurons treated with the caspase activator AAII. To study direct progestagen effects on neuron survival, cultures were pretreated for 1 h with 10 nM P4 or individual progestagens (10 nM) followed by 24 h exposure to a toxic concentration (3 μM) of AAII. To examine whether progestagens interact with E2 protection, cultures were pretreated for 15 h with 10 nM progestagen, followed by 1 h pretreatment with 10 nM E2, then 24 h exposure to AAII. We found that AAII treatment decreased by >80% the number of viable neurons. E2 treatment significantly increased neuron survival to >50% levels observed in vehicle-treated control cells. In contrast to E2, P4 did not significantly improve neuron survival and, consistent with our prior observations (Jayaraman and Pike, 2009), completely blocked E2-mediated protection (Fig. 3A). Among the synthetic progestagens, MPA, NET, NOR, and NGM did not significantly reduce AAII-induced neuron death when treated alone (Fig. 3 B, C, E, G). On the other hand, NETA, LNG, and NEST all significantly increased survival in cultures treated with AAII (Fig. 3 D, F, H). When combined with E2, MPA paralleled the P4 effect of blocking E2-mediated protection against AAII (Fig. 3B). None of the other six synthetic progestagens significantly altered the protective action of E2 except for NOR (Fig. 3C–H). Addition of NOR significantly blocked E2-mediated neuroprotection as compared to E2-alone, however, the cell viability was still significantly higher than vehicle-treated control (Fig. 3 E).

Figure 3. Progestagens regulate neuroprotection alone and in combination with E2.

Neuronal cultures were treated with vehicle or 10 nM P4 (A), MPA (B), NET (C), NETA (D), NOR (E), LNG (F), NGM (G), and NEST (H) alone or in combination with 10 nM E2 for 2 h, followed by treatment with 3 μM Apoptosis Activator II (AAII) for 24 h, and processed for cell viability. Data show mean cell viability (± SEM) of a representative experiment (N = 3). * P≤0.05 relative to the vehicle-treated control condition exposed to AAII. # P≤0.05 relative to E2-treated condition exposed to AAII and is based on ANOVA followed by Fisher LSD.

3.4. Effects of progestagens on BDNF expression in the presence and absence of estradiol

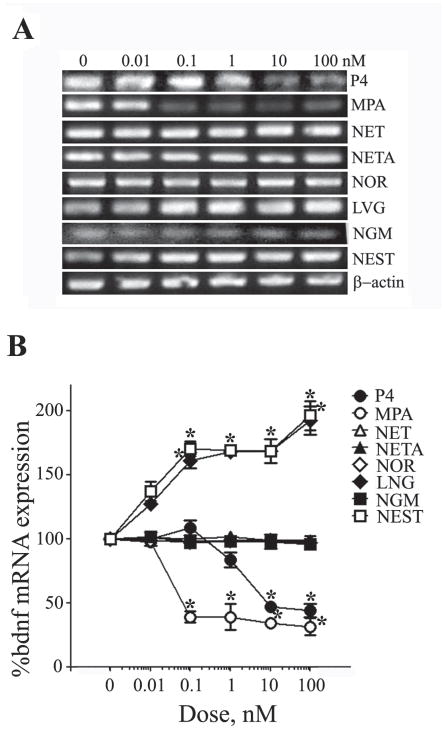

Several studies have established the role of BDNF in E2-mediated neuroprotection (Baudry et al., 2013). Prior work has demonstrated that P4 attenuates E2 neuroprotection by decreasing ER expression and ER-mediated increase in BDNF expression (Aguirre et al., 2010, Aguirre and Baudry, 2009). To evaluate the contribution of this pathway to the observed effects of the progestagens on apoptosis and on E2 neuroprotection, we examined their effects on BDNF mRNA levels. Consistent with previous finding, we observed that P4 at ≥ 10 nM significantly reduced BDNF mRNA levels (Fig. 4). In comparison, MPA significantly also reduced BDNF mRNA but was effective at concentrations as low as 0.1 nM. The progestagens NET, NETA, NOR, and NGM did not significantly affect BDNF levels whereas LNG and NEST increased BDNF expression to maximum levels between 1.5 – 2 fold above those observed in vehicle-treated control cultures (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Progestagens regulate BDNF mRNA expression in a concentration-dependent manner.

(A) Representative agarose gel of RT-PCR products qualitatively show relative changes in mRNA levels of the BDNF induced by 24 h exposure to 0 – 100 nM of progestagens. β-actin was used as an internal control. (B) The relative levels of BDNF after treatment with increasing progestagen concentrations were also determined quantitatively using real-time PCR. Data show the mean (±SEM) expression levels, relative to vehicle-treated controls after normalizing with corresponding values of β-actin. * P≤0.05 relative to corresponding vehicle-treated condition.

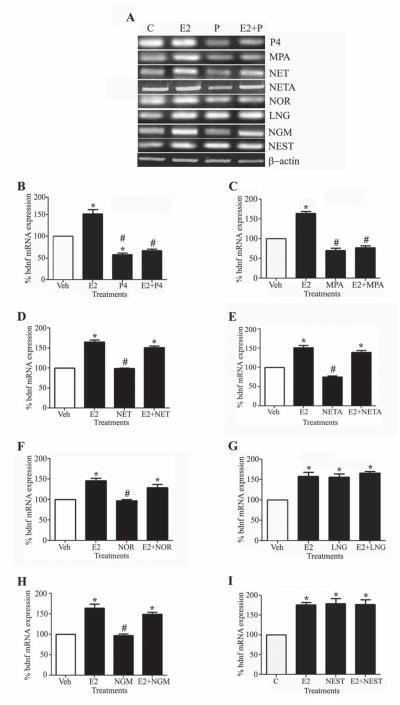

In order to investigate the effects of P4 and all seven synthetic progestagens on E2-mediated increases in BDNF mRNA expression, we pretreated the neurons with 10 nM of P4 or synthetic progestagen for 15 h followed by 8 h of E2 treatment. Our results showed that both P4 and MPA completely prevented the 1.5 fold increase in BDNF observed with E2 treatment alone (Fig. 5A–C). The combination of E2 with any of the other progestagens (NET, NETA, NOR, NGM, LVG and NEST) did not significantly alter BDNF mRNA levels in comparison to E2 alone (Fig. 5A, D–I).

Figure 5. Progestagens regulate E2-induced BDNF mRNA expression.

(A) Representative agarose gel of RT-PCR products qualitatively shows changes in the levels of BDNF mRNA following treatment with vehicle, 10 nM E2, 10 nM progestagen, and 10 nM E2+progestagen. (B–I) Quantitative real-time PCR data show the mean (±SEM) expression levels compared to the vehicle-treated control group (white bar) for BDNF mRNA respectively. All data are normalized with corresponding β-actin values. Statistical significance is based on analysis of pooled raw data using ANOVA followed by the Fisher HSD. * P≤0.05 relative to the vehicle-treated control group. # P≤0.05 relative to the E2-treatment group.

Collectively, these and prior in vitro data suggest progestagens can modulate E2-mediated neuroprotective actions by regulating ER expression. As an initial step in investigating whether these actions occur in vivo, we examined the ability of P4 to regulate E2-induced ER expression in adult female rats. In ovariectomized rats, E2 increased cortical expression of ERα and ERβ mRNAs. Acute P4 administration following E2 treatment, significantly attenuated the E2-induced increases in both ERα and ERβ (Supplemental Fig. 1).

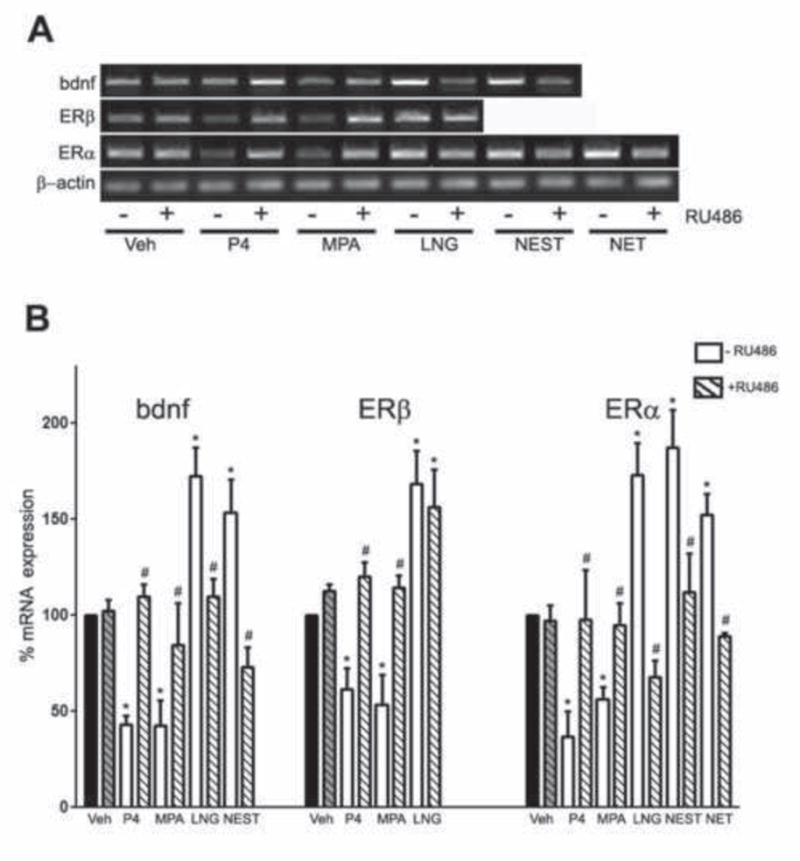

3.5 Transcriptional regulation of progestagens is reversed by RU486

In order to investigate the suspected role of PR in the observed progestagen actions, we pretreated neuron cultures with 50 nM RU486, a known PR antagonist (Schreiber et al., 1983), followed by treatment with 10 nM of P4, MPA, LNG, NEST, or NET for 24 h. At the end of the treatment period, cells were harvested for RNA isolation and expression analyses of ERα, ERβ, and BDNF mRNA. Our data show that RU486 treatment alone did not significantly alter gene expression but significantly attenuated all mRNA regulatory effects of P4, MPA, LNG, NEST, and NET on ERα, ERβ, and BDNF mRNA, with the exception of not affecting LNG-induced upregulation of ERβ mRNA (Fig. 6 A, B).

Figure 6. Transcriptional regulation of progestagens is reversed by RU486.

(A) Representative agarose gel of RT-PCR products qualitatively shows changes in the levels of BDNF, ERα, and ERβ mRNAs following treatment with 10 nM progestagen with or without 50 nM RU486. (B) Quantitative real-time PCR data show the mean (±SEM) expression levels compared to the vehicle-treated control group (black bar) for BDNF, ERα and ERβ mRNA respectively. All data are normalized with corresponding β-actin values. Statistical significance is based on analysis of pooled raw data using ANOVA followed by the Fisher HSD. * P≤0.05 relative to the vehicle-treated control group. # P≤0.05 relative to the corresponding –RU486 treatment group for a specific progestagen.

4. Discussion

In previous studies, we demonstrated inhibitory effects of P4 on ER expression and function as well as attenuation of E2-induced neuroprotection and BDNF expression (Aguirre et al., 2010, Aguirre and Baudry, 2009, Jayaraman and Pike, 2009). In the current study, we investigated the effect of seven clinically relevant, synthetic progestagens on the expression levels of ERα, ERβ, and BDNF, E2-mediated neuroprotection against apoptosis and E2-induced BDNF expression. As summarized in Table 1, the progestagens show considerable variability on these measures.

Table 1.

Effects of progestagens on gene expression and neuroprotection.

| Progestagen | ERα expression | ERβ expression | Neuroprotection | BDNF expression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −E2 | +E2∂ | −E2 | +E2∂ | |||

| Progesterone (P4) | Decreased | Decreased | No | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased |

| Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA) | Decreased | Decreased | No | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased |

| Norethindrone (NET) | Increased | No effect | No | No effect | No effect | No effect |

| Norethindrone Acetate (NETA) | No effect | No effect | Yes | No effect | No effect | No effect |

| Norethynodrel (NOR) | No effect | No effect | No | Decreased | No effect | No effect |

| Levonorgestrel (LNG) | Increased | Increased | Yes | No effect | Increased | No effect |

| Norgestimate (NGM) | No effect | No effect | No | No effect | No effect | No effect |

| Nesterone (NEST) | Increased | No effect | Yes | No effect | Increased | No effect |

Compared to treatment with E2 alone. All other data compared to vehicle-treated controls.

Of the seven synthetic progestagens, only MPA showed effects very similar to P4. Like P4, MPA reduced ERα and ERβ mRNA levels in a concentration and time-dependent manner. It was not neuroprotective against apoptosis and did not increase BDNF mRNA expression in primary neurons. This is in agreement with several studies that demonstrate MPA generally fails to induce neuroprotective actions in cell culture (Mannella et al., 2009, Nilsen and Brinton, 2002) and animal models (Ciriza et al., 2006, Jodhka et al., 2009, Rosario, 2006). Among the other progestagens, LNG, and NEST increased the expression of ERα and BDNF mRNA, while only LNG increased the expression of ERβ mRNA. LNG and NEST were also neuroprotective against apoptotic insult. These data suggest that protection against apoptosis by both LNG and NEST might involve promoting ER signaling and or increasing BDNF expression. Nonetheless, there are multiple signaling pathways and survival factors besides BDNF that are associated with neuroprotective actions of E2 and progestagens (Brinton et al., 2008, Liu et al., 2010b). Our data is strengthened by recent studies that have shown NEST to promote axon remyelination (Hussain et al., 2011) as well as increase neural cell proliferation and MAPK signaling (Liu et al., 2010a). LNG has been shown to increase the expression levels of anti-apoptotic genes as well as increase MAPK signaling, both of which are implicated strongly in neuroprotection (Liu et al., 2010a). On the other hand, NET only increased ERα mRNA levels and had no effect on ERβ and BDNF expression or neuroprotection. The increase in ERα expression by NET may not be sufficient to induce neuroprotection or BDNF expression. NETA had no effect on any gene expression although it was neuroprotective against apoptosis, suggesting that it might be signaling via rapid signaling pathways and or through other target genes. NOR and NGM neither affected ER and BDNF gene expression nor induced neuroprotective responses.

Progestagens are routinely administered along with E2 for hormone therapies and oral contraceptives. Hence, understanding the neural effects of progestagens in combination with E2 is a significant issue. Our data show that MPA blocks E2-mediated neuroprotection as well as E2-induced increase in BDNF mRNA expression, an effect that is similar to P4 in neurons (Aguirre et al., 2010, Aguirre and Baudry, 2009, Jayaraman and Pike, 2009) and also seen in different cell types (Irwin et al., 2011, Nilsen and Brinton, 2002, Nilsen and Diaz Brinton, 2003, Nilsen et al., 2006, Vereide et al., 2006). Therefore, as is the case with P4, the reduction in ER expression and perhaps ER function may contribute to the mechanism by which MPA blocks E2 action. On the other hand, PR expression is dependent on E2 in some brain regions, including hypothalamus (MacLusky and McEwen, 1978, Shughrue et al., 1997). However, PR expression in the cortex appears to be largely independent of E2 regulation both in postnatal (Shughrue et al., 1991) and adult brains (Zuloaga et al., 2012).

Unlike P4 and MPA, the progestagens NET, LNG, and NEST did not block E2-mediated neuroprotection or E2-induced BDNF expression. In animal studies both LNG and NEST have beneficial effects on neurogenesis and on the expression of anti-apoptotic factors in combination with E2 (Liu et al., 2010a). The effect of LNG on ER expression observed in our study is in contrast to the previously published antagonistic effect of LNG on ERα and ERβ expression in endometrial cells (Vereide et al., 2006). Thus, LNG may have cell-type specific effects on ERs possibly by retaining the beneficial neuronal E2 functions while decreasing its detrimental effects in endometrial cells. The neuroprotective effect of NEST in combination with E2 was previously observed in primary hippocampal cultures against glutamate toxicity (Nilsen and Brinton, 2002). NETA, NGM, and NOR did not have any effect on the assessed E2 functions, except for NOR which blocked E2-mediated neuroprotection but not E2-induced BDNF expression. These results suggest that NOR could be activating alternate signaling pathways that diminish E2-mediated neuroprotection but not E2-induced gene expression. One study shows that NETA signals via ER to change blood coagulation factors (Shirk et al., 2005). However, our results show that, in neurons, NETA does not alter ER expression or function. Together, our data suggest that relationships between the effects on ER expression and E2-mediated function for five of the seven synthetic progestagens. Unclear is the extent to which these observations apply in vivo. The presence of ERα and ERβ in adult rodent cortex and their regulation by P4 (Supplemental Fig. 1) and our previous observation of P4 and MPA inhibition of E2 neuroprotection in an animal model (Rosario et al., 2006) argue in favor of the possibility that these culture observations at least partially extrapolate to the in vivo condition.

The differences in gene expression and neuroprotection by different progestagens may be attributed to several factors. First, the seven synthetic progestagens have different chemical structures. MPA is derived from the pregnane-structure; NET, NETA, and NOR are derived from the estrane structure; LNG and NGM are derived from the gonane-structure; and NEST is derived from 19-norprogesterone structure. The structural differences may, in part, be responsible for different outcomes when these progestagens are administered alone and with E2. MPA, which is exclusively antagonistic to ER expression and function, is also the only progestagen with the pregnane-structure. On the other hand, NEST with a 19-norprogesterone structure has beneficial effects on both neuroprotection and expression levels of ERα and BDNF. The progestagens in the estrane and gonane groups do not have similar outcomes based on their structural similarities suggesting that other factors apart from structure may be important in determining their actions. Further, since progestagens vary in their affinities for PR (Sitruk-Ware, 2004), it is possible that some of the observed relationships could change with different progestagen concentrations. One limitation of some of our experiments is that they utilized a single, effective concentration that was conserved across progestagens.

Another key factor that may contribute to the observed differences is the prodrug property of some synthetic progestagens. Specifically, NETA and NOR require conversion to NET for maximal biological activity (Palmer et al., 1969, Sitruk-Ware, 2000b, Stanczyk et al., 2013). Similarly, NGM needs to be converted to LNG to exert a progestational effect (Kuhnz et al., 1995). In our in vitro experimental paradigm, it is possible that NGM had no apparent effects on BDNF mRNA expression and neuroprotection because of insufficient or lack of conversion to LNG. NETA and NOR showed partial effects on neuroprotection, which is absent in NET, suggesting that these progestagens are able to have some biological activity even as prodrugs. Although relatively little is known about the metabolism of synthetic progestagens, each progestagen forms specific metabolites, which likely vary in their specific biological activities. Further, the pharmacokinetics of the progestagens will determine their bioavailability and half-life. One limitation of our primary culture system is that it may not fully recapitulate the in vivo metabolism and pharmacokinetics of the progestagens.

Synthetic progestagens also differ in their binding affinities to the various steroid receptors. Our finding that most of the observed regulatory actions of the progestagens on mRNA levels of ERα, ERβ, and BDNF were significantly attenuated by the PR antagonist RU486 argues in favor of an essential role of PR. NEST belongs to the category of pure progestational molecules as it has an exclusive affinity to PRs and does not bind to any other steroid receptors (Kumar et al., 2000, Liu et al., 2010a, Sitruk-Ware, 2000a). On the other hand, LNG is known to have a high affinity for PR but also can bind to glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and AR (Kumar et al., 2000, Liu et al., 2010a). Although LNG does not bind ERs, it is reported to have significant estrogenic activity as evidenced by an increase in uterine weights in treated animals (Kumar et al., 2000). This is in accordance with our data where LNG shows estrogen-like activity by increasing ER expression and E2-mediated functions. Interestingly, the effect of LNG on ERβ mRNA was not affected by RU486, suggesting that this action might be PR-independent and possibly via interaction of LNG with AR or other steroid receptors. MPA and the estrane-derived progestagens (NET, NETA, NOR) have high affinity to AR as compared to PR (Bullock and Bardin, 1977, Liu et al., 2010a, Wiegratz and Kuhl, 2004). MPA is also capable of binding to GR with relatively high affinity (Liu et al., 2010a). The promiscuous binding affinities may significantly impact the signaling pathways and molecular targets that are involved. The activation of alternate progesterone receptors such as Pgrmc1 and membrane PR may also result in different neuroprotective outcomes. For example, MPA has been shown to activate Pgrmc1 (Allen et al., 2013, Ruan et al., 2012) and membrane PR (Bottino et al., 2011) in certain cell types. Additionally, treatment duration and model systems will also contribute to variations in observed signaling pathways.

5. Conclusions

Clinically relevant synthetic progestagens have long been used in oral contraceptives, fertility treatments, and hormone replacement therapies. In many cases, these progestagens are administered for extended periods. Despite their prevalent use, relatively little is known about the neural effects of these synthetic progestagens, both in terms of their independent actions and their interactions with estrogens. Although our study involves acute treatment paradigms, the results suggest that synthetic progestagens have varying effects on neuroprotection against apoptotic insults and E2-mediated neuronal actions, and thus should be expected to have significantly different effects in long-term clinical treatments. These findings highlight the need for continued analyses of the effects of commonly used progestagens on neural health.

Supplementary Material

The relative levels of ERα mRNA (A) and ERβ mRNA (B) were determined quantitatively using real-time PCR in animals that are sham-Ovx (Sham), Ovx, Ovx with E2 treatment (Ovx+E), and Ovx with E2 and P4 treatments (Ovx+E+P). Data show the mean (±SEM) expression levels, relative to vehicle-treated controls after normalizing with corresponding values of β-actin. Statistical significance is based on analysis of pooled raw data using ANOVA followed by the Fisher LSD. *P≤0.05 relative to corresponding vehicle-treated control group; #P≤0.05 relative to Ovx+E group. Experimentally, female Sprague-Dawley rats (age 3 mo) were ovariectomized under isoflurane anesthesia, and 4 d later a silastic capsule was implanted subcutaneously into each rat containing nothing (control) or crystalline E2 (N=3/group). Two days following silastic implantation, rats were injected (ip) with vehicle (canola oil) or 500 μg P4 in oil; 10 h post-injection animals were euthanized and tissues were collected for RNA analyses. Total RNA was isolated from cortical samples, followed by cDNA synthesis and PCR using ERα and ERβ specific primers.

Highlights.

Progestagens are used clinically but their neural effects are poorly understood

Progesterone and clinically relevant progestagens were examined in cultured neurons

Progesterone inhibits estradiol-induced neuroprotection and regulation of BDNF

Medroxyprogesterone acetate closely mimics the effects of progesterone

Other progestagens vary significantly in terms of progesterone-like actions

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant AG026572. We thank Dr. Roberta Diaz Brinton and Dr. Liqin Zhao from University of Southern California, and Dr. Sitruk-Ware from the Rockefeller University for providing us with progestagens.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aguirre C, Jayaraman A, Pike C, Baudry M. Progesterone inhibits estrogen-mediated neuroprotection against excitotoxicity by down-regulating estrogen receptor-beta. J Neurochem. 2010;115(5):1277–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre CC, Baudry M. Progesterone reverses 17beta-estradiol-mediated neuroprotection and BDNF induction in cultured hippocampal slices. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29(3):447–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkayed NJ, Murphy SJ, Traystman RJ, Hurn PD, Miller VM. Neuroprotective effects of female gonadal steroids in reproductively senescent female rats. Stroke. 2000;31(1):161–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen TK, Feng L, Grotegut CA, Murtha AP. Progesterone Receptor Membrane Component 1 as the Mediator of the Inhibitory Effect of Progestins on Cytokine-Induced Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 Activity In Vitro. Reprod Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1933719113493514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry M, Bi X, Aguirre C. Progesterone-estrogen interactions in synaptic plasticity and neuroprotection. Neuroscience. 2013;239:280–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bimonte-Nelson H, Nelson ME, Granholm AC. Progesterone counteracts estrogen-induced increases in neurotrophins in the aged female rat brain. Neuroreport. 2004;15(17):2659–63. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200412030-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottino MC, Cerliani JP, Rojas P, Giulianelli S, Soldati R, Mondillo C, Gorostiaga MA, Pignataro OP, Calvo JC, Gutkind JS, Panomwat A, Molinolo AA, Luthy IA, Lanari C. Classical membrane progesterone receptors in murine mammary carcinomas: agonistic effects of progestins and RU-486 mediating rapid non-genomic effects. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126(3):621–36. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0971-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton RD, Thompson RF, Foy MR, Baudry M, Wang J, Finch CE, Morgan TE, Pike CJ, Mack WJ, Stanczyk FZ, Nilsen J. Progesterone receptors: form and function in brain. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29(2):313–39. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock LP, Bardin CW. Androgenic, synandrogenic, and antiandrogenic actions of progestins. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1977;286:321–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1977.tb29427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JC, Rosario ER, Chang L, Stanczyk FZ, Oddo S, LaFerla FM, Pike CJ. Progesterone and estrogen regulate Alzheimer-like neuropathology in female 3xTg-AD mice. J Neurosci. 2007;27(48):13357–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2718-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciriza I, Carrero P, Frye CA, Garcia-Segura LM. Reduced metabolites mediate neuroprotective effects of progesterone in the adult rat hippocampus. The synthetic progestin medroxyprogesterone acetate (Provera) is not neuroprotective. J Neurobiol. 2006;66(9):916–28. doi: 10.1002/neu.20293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordey M, Gundimeda U, Gopalakrishna R, Pike CJ. Estrogen activates protein kinase C in neurons: role in neuroprotection. J Neurochem. 2003;84(6):1340–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Nicola AF, Labombarda F, Deniselle MC, Gonzalez SL, Garay L, Meyer M, Gargiulo G, Guennoun R, Schumacher M. Progesterone neuroprotection in traumatic CNS injury and motoneuron degeneration. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30(2):173–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Vongher JM. GABA(A), D1, and D5, but not progestin receptor, antagonist and anti-sense oligonucleotide infusions to the ventral tegmental area of cycling rats and hamsters attenuate lordosis. Behav Brain Res. 1999a;103(1):23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye CA, Vongher JM. Progestins’ rapid facilitation of lordosis when applied to the ventral tegmentum corresponds to efficacy at enhancing GABA(A)receptor activity. J Neuroendocrinol. 1999b;11(11):829–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Segura LM, Cardona-Gomez P, Naftolin F, Chowen JA. Estradiol upregulates Bcl-2 expression in adult brain neurons. Neuroreport. 1998;9(4):593–7. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199803090-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Deniselle MC, Garay L, Gonzalez S, Saravia F, Labombarda F, Guennoun R, Schumacher M, De Nicola AF. Progesterone modulates brain-derived neurotrophic factor and choline acetyltransferase in degenerating Wobbler motoneurons. Exp Neurol. 2007;203(2):406–14. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain R, El-Etr M, Gaci O, Rakotomamonjy J, Macklin WB, Kumar N, Sitruk-Ware R, Schumacher M, Ghoumari AM. Progesterone and Nestorone facilitate axon remyelination: a role for progesterone receptors. Endocrinology. 2011;152(10):3820–31. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin RW, Yao J, Ahmed SS, Hamilton RT, Cadenas E, Brinton RD. Medroxyprogesterone acetate antagonizes estrogen up-regulation of brain mitochondrial function. Endocrinology. 2011;152(2):556–67. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman A, Carroll JC, Morgan TE, Lin S, Zhao L, Arimoto JM, Murphy MP, Beckett TL, Finch CE, Brinton RD, Pike CJ. 17beta-estradiol and progesterone regulate expression of beta-amyloid clearance factors in primary neuron cultures and female rat brain. Endocrinology. 2012;153(11):5467–79. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman A, Pike CJ. Progesterone attenuates oestrogen neuroprotection via downregulation of oestrogen receptor expression in cultured neurones. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21(1):77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01801.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jodhka PK, Kaur P, Underwood W, Lydon JP, Singh M. The differences in neuroprotective efficacy of progesterone and medroxyprogesterone acetate correlate with their effects on brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression. Endocrinology. 2009;150(7):3162–8. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnz W, Fritzemeier KH, Hegele-Hartung C, Krattenmacher R. Comparative progestational activity of norgestimate, levonorgestrel-oxime and levonorgestrel in the rat and binding of these compounds to the progesterone receptor. Contraception. 1995;51(2):131–9. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(94)00019-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N, Koide SS, Tsong Y, Sundaram K. Nestorone: a progestin with a unique pharmacological profile. Steroids. 2000;65(10–11):629–36. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(00)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labombarda F, Gonzalez SL, Deniselle MC, Vinson GP, Schumacher M, De Nicola AF, Guennoun R. Effects of injury and progesterone treatment on progesterone receptor and progesterone binding protein 25-Dx expression in the rat spinal cord. J Neurochem. 2003;87(4):902–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Zhao L, She H, Chen S, Wang JM, Wong C, McClure K, Sitruk-Ware R, Brinton RD. Clinically relevant progestins regulate neurogenic and neuroprotective responses in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology. 2010a;151(12):5782–94. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Kelley MH, Herson PS, Hurn PD. Neuroprotection of sex steroids. Minerva Endocrinol. 2010b;35(2):127–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLusky NJ, McEwen BS. Oestrogen modulates progestin receptor concentrations in some rat brain regions but not in others. Nature. 1978;274(5668):276–8. doi: 10.1038/274276a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannella P, Sanchez AM, Giretti MS, Genazzani AR, Simoncini T. Oestrogen and progestins differently prevent glutamate toxicity in cortical neurons depending on prior hormonal exposure via the induction of neural nitric oxide synthase. Steroids. 2009;74(8):650–6. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DD, Segal M. Regulation of dendritic spine density in cultured rat hippocampal neurons by steroid hormones. J Neurosci. 1996;16(13):4059–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04059.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DD, Segal M. Progesterone prevents estradiol-induced dendritic spine formation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroendocrinology. 2000;72(3):133–43. doi: 10.1159/000054580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TV, Jayaraman A, Quaglino A, Pike CJ. Androgens selectively protect against apoptosis in hippocampal neurones. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22(9):1013–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen J, Brinton RD. Impact of progestins on estradiol potentiation of the glutamate calcium response. Neuroreport. 2002;13(6):825–30. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200205070-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen J, Diaz Brinton R. Mechanism of estrogen-mediated neuroprotection: regulation of mitochondrial calcium and Bcl-2 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(5):2842–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438041100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen J, Morales A, Brinton RD. Medroxyprogesterone acetate exacerbates glutamate excitotoxicity. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22(7):355–61. doi: 10.1080/09513590600863337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer R, Guillon G, Pasquier F, Proust-Perrault J. Clinical and biochemical study of 37 cases of endocrine sterility, with corpus luteum estrogenic deficiency in Jayle’s dynamic test, treated by HMG-O in the preovulation phase. Gynecol Obstet (Paris) 1969;68(1):51–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes ME, Frye CA. Progestins in the hippocampus of female rats have antiseizure effects in a pentylenetetrazole seizure model. Epilepsia. 2004;45(12):1531–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.16504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roof RL, Duvdevani R, Braswell L, Stein DG. Progesterone facilitates cognitive recovery and reduces secondary neuronal loss caused by cortical contusion injury in male rats. Exp Neurol. 1994;129(1):64–9. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario ER, Ramsden M, Pike CJ. Progestins inhibit the neuroprotective effects of estrogen in rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2006;1099(1):206–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan X, Neubauer H, Yang Y, Schneck H, Schultz S, Fehm T, Cahill MA, Seeger H, Mueck AO. Progestogens and membrane-initiated effects on the proliferation of human breast cancer cells. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):467–72. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2011.648232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayeed I, Stein DG. Progesterone as a neuroprotective factor in traumatic and ischemic brain injury. Prog Brain Res. 2009;175:219–37. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber JR, Hsueh AJ, Baulieu EE. Binding of the anti-progestin RU-486 to rat ovary steroid receptors. Contraception. 1983;28(1):77–85. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(83)80008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M, Guennoun R, Ghoumari A, Massaad C, Robert F, El-Etr M, Akwa Y, Rajkowski K, Baulieu EE. Novel Perspectives for progesterone in Hormone Replacement Therapy, with special reference to the nervous system. Endocrine Reviews. 2007a;28(4):387–439. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M, Guennoun R, Stein DG, De Nicola AF. Progesterone: Therapeutic opportunities for neuroprotection and myelin repair. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2007b;116(1):77–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M, Sitruk-Ware R, De Nicola AF. Progesterone and progestins: neuroprotection and myelin repair. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8(6):740–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk RA, Zhang Z, Winneker RC. Differential effects of estrogens and progestins on the anticoagulant tissue factor pathway inhibitor in the rat. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;94(4):361–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue PJ, Lane MV, Merchenthaler I. Regulation of progesterone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in the rat medial preoptic nucleus by estrogenic and antiestrogenic compounds: an in situ hybridization study. Endocrinology. 1997;138(12):5476–84. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.12.5595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue PJ, Stumpf WE, Elger W, Schulze PE, Sar M. Progestin receptor cells in mouse cerebral cortex during early postnatal development: a comparison with preoptic area and central hypothalamus using autoradiography with [125I]progestin. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1991;59(2):143–55. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90094-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitruk-Ware R. Approval of mifepristone (RU 486) in Europe. Zentralbl Gynakol. 2000a;122(5):241–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitruk-Ware R. Progestins and cardiovascular risk markers. Steroids. 2000b;65(10–11):651–8. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(00)00174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitruk-Ware R. Hormonal replacement therapy. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2002a;3(3):243–56. doi: 10.1023/a:1020028510797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitruk-Ware R. Progestogens in hormonal replacement therapy: new molecules, risks, and benefits. Menopause. 2002b;9(1):6–15. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitruk-Ware R. Pharmacological profile of progestins. Maturitas. 2004;47(4):277–83. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanczyk FZ, Hapgood JP, Winer S, Mishell DR., Jr Progestogens used in postmenopausal hormone therapy: differences in their pharmacological properties, intracellular actions, and clinical effects. Endocr Rev. 2013;34(2):171–208. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DG. Progesterone exerts neuroprotective effects after brain injury. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57(2):386–97. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DG, Wright DW. Progesterone in the clinical treatment of acute traumatic brain injury. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19(7):847–57. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2010.489549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vereide AB, Kaino T, Sager G, Arnes M, Orbo A. Effect of levonorgestrel IUD and oral medroxyprogesterone acetate on glandular and stromal progesterone receptors (PRA and PRB), and estrogen receptors (ER-alpha and ER-beta) in human endometrial hyperplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101(2):214–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegratz I, Kuhl H. Progestogen therapies: differences in clinical effects? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15(6):277–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuloaga DG, Yahn SL, Pang Y, Quihuis AM, Oyola MG, Reyna A, Thomas P, Handa RJ, Mani SK. Distribution and estrogen regulation of membrane progesterone receptor-beta in the female rat brain. Endocrinology. 2012;153(9):4432–43. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The relative levels of ERα mRNA (A) and ERβ mRNA (B) were determined quantitatively using real-time PCR in animals that are sham-Ovx (Sham), Ovx, Ovx with E2 treatment (Ovx+E), and Ovx with E2 and P4 treatments (Ovx+E+P). Data show the mean (±SEM) expression levels, relative to vehicle-treated controls after normalizing with corresponding values of β-actin. Statistical significance is based on analysis of pooled raw data using ANOVA followed by the Fisher LSD. *P≤0.05 relative to corresponding vehicle-treated control group; #P≤0.05 relative to Ovx+E group. Experimentally, female Sprague-Dawley rats (age 3 mo) were ovariectomized under isoflurane anesthesia, and 4 d later a silastic capsule was implanted subcutaneously into each rat containing nothing (control) or crystalline E2 (N=3/group). Two days following silastic implantation, rats were injected (ip) with vehicle (canola oil) or 500 μg P4 in oil; 10 h post-injection animals were euthanized and tissues were collected for RNA analyses. Total RNA was isolated from cortical samples, followed by cDNA synthesis and PCR using ERα and ERβ specific primers.