Abstract

PURPOSE

Efficacy and acute toxicity of proton craniospinal irradiation (p-CSI) were compared with conventional photon CSI (x-CSI) for adults with medulloblastoma.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Forty adult medulloblastoma patients treated with x-CSI (n=21) or p-CSI (n=19) at XXXXX from 2003–2011 were retrospectively reviewed. Median CSI and total doses were 30.6 and 54 Gy, respectively. The median follow-up was 57 months (range 4–103) for x-CSI patients and 26 months (range 11–63) for p-CSI.

RESULTS

p-CSI patients lost less weight than x-CSI patients (1.2%, versus 5.8%; p=0.004), and less p-CSI patients had greater than 5% weight loss compared to x-CSI (16% versus 64%; p=0.004). p-CSI patients experienced less grade 2 nausea and vomiting compared to x-CSI (26% versus 71%; p=0.004). Patients treated with x-CSI were more likely to have medical management of esophagitis than p-CSI patients (57% vs 5%, p=<0.001).

p-CSI patients had a smaller reduction in peripheral white blood cells (WBC), hemoglobin and platelets compared to x-CSI (WBC 46% versus 55%, p=0.04; hemoglobin 88% versus 97%, p=0.009; platelets 48% versus 65%, p=0.05). Mean vertebral doses were significantly associated with reductions in blood counts.

CONCLUSIONS

This report is the first analysis of clinical outcomes for adult medulloblastoma patients treated with p-CSI. Patients treated with p-CSI experienced less treatment-related morbidity including less acute gastrointestinal and hematologic toxicities.

INTRODUCTION

Medulloblastoma is a primitive neuroectodermal tumor accounting for approximately 20–30% of childhood brain tumors. However, adult medulloblastoma is rare, with an incidence rate of 0.5 per million, and differs from pediatric medulloblastoma in clinical outcomes as well as its molecular profile(1–4). Craniospinal irradiation (CSI), typically x-ray based (XRT), plays a critical role in management of pediatric and adult medulloblastoma, but is associated with significant acute and late side effects(5–7). These adverse effects can dramatically influence patient outcomes and quality of life(8). Proton beam radiation therapy (PBRT) has been proposed to reduce treatment-related morbidity in patients requiring CSI. However, much of the current literature supporting proton beam CSI (p-CSI) is focused on late effects in pediatric patients and is based on risk estimates and modeling rather than actual patient data(8–10). In an effort to minimize toxicity, adults requiring CSI were treated with PBRT at XXXXX since 2006 when PBRT became available.

The purpose of this study was to compare efficacy and acute toxicity of p-CSI versus conventional photon CSI (x-CSI) in adults with medulloblastoma. In the absence of randomized trials for this rare condition, these data can inform clinicians and patients about acute toxicities related to both p-CSI and x-CSI.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patients

Forty adults with histologically-confirmed medulloblastoma, treated consecutively with CSI at XXXXX from 2003 to 2011, were analyzed in this institutional review board-approved, retrospective study. Patients 16 years or older at radiation therapy (RT) were included, because such patients have reached skeletal maturity, permitting the vertebral body-sparing p-CSI technique described in this study. Patient, tumor, treatment and follow-up information was abstracted from the medical record. Patients were staged with the modified Chang system using surgical, imaging, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) data. Patients were classified as high risk for at least 1.5 cm2 postoperative residual tumor, assessed by postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT), or evidence of CNS dissemination or extraneural metastatic disease on imaging or CSF cytology.

Treatment

Patients underwent surgical resection of the primary tumor, with the intent of complete resection whenever possible. Chemotherapy regimens and timing of administration relative to RT varied as determined by treating physicians. All patients receiving concurrent chemotherapy received vincristine, with one patient in the p-CSI arm also receiving carboplatin. x-CSI patients who received chemotherapy prior to CSI were treated with a platinum, etoposide regimen with six of seven also receiving a classical alkylating agent (cyclophosphamide or ifosfamide). Two of four p-CSI patients who received chemotherapy prior to CSI also received this regimen, with the other two patients receiving a platinum, etoposide, vincristine regimen. All patients received CSI with a tumor-bed boost encompassing any residual disease. Twenty-one patients received x-CSI, starting in 2003, with 19 patients receiving p-CSI, starting in 2007. All patients completed prescribed RT, except one patient in the x-CSI arm, whose treatment was discontinued after 25.5 Gy because of thrombocytopenia.

x-CSI was delivered after conventional prone-position CT simulation using a thermoplastic mask for head immobilization. Patients received cranial irradiation using opposed lateral beams, slightly angled to avoid divergence into the contralateral lens, geometrically matched to postero-anterior spine fields. Two to three spinal fields encompassed the spine and thecal sac inferiorly. Six or 18-MV photons were used throughout, with the 100% isodose line covering the CSF space, allowing for setup-up uncertainty. Conventional weekly or intra-fractional junction shifts, as described by Yom et al., were used to minimize potential hot spots in the spinal cord(11). A boost was delivered to either the entire posterior fossa, or the postoperative-bed and residual tumor with a 1–1.5 cm expansion to create the clinical target volume (CTV), using 3D conformal RT or intensity modulated RT (IMRT).

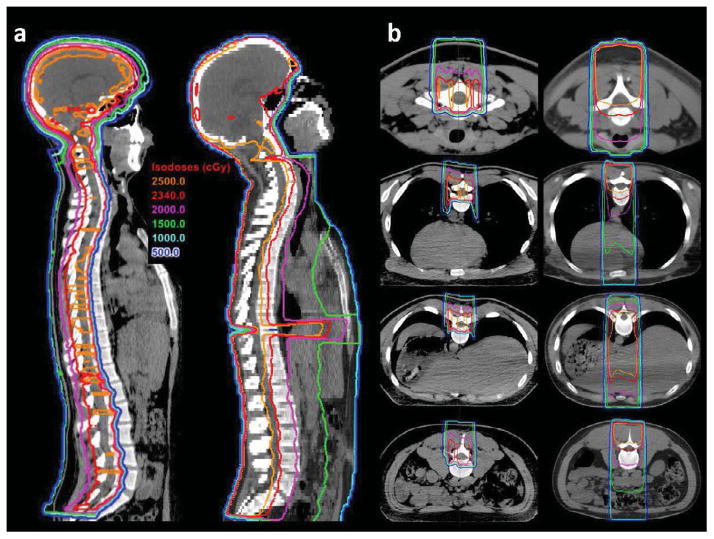

The simulation and beam arrangement for p-CSI was similar, though the patient was placed supine with a plastic head-holder and thermoplastic mask. A vertebral body-sparing technique was used with the distal range of spinal fields extending partially into the vertebral bodies anteriorly, providing 100% coverage of the spinal canal CTV, while minimizing dose to the entire vertebral body (figure 1). A relative biological effectiveness (RBE) factor of 1.1 was used for PBRT planning in accordance with International Commission on Radiation units and Measurements (ICRU) Report 78 dose prescription and reporting recommendations, and consistent with the clinical practice at XXXXX. PBRT boosts were given to the entire posterior fossa or the postoperative-bed and any residual tumor with a 1–1.5 cm expansion, with a conformal beam arrangement minimizing radiation to surrounding normal tissue.

Figure 1.

Treatment planning computed tomography (CT) images in sagittal (panel a) and axial planes (panel b) comparing treatment plans for a proton craniospinal irradiation (CSI; left) and conventional photon CSI (right). The CSI prescription dose for each patient was 23.4 Gy. Isodose lines indicate significant reductions in doses delivered to the thyroid gland, esophagus, heart, lungs, liver, stomach, and bowel with proton CSI with sparing of the anterior vertebral bodies.

Treatment plans were approved by board-certified radiation oncologists, experienced in x-CSI and p-CSI. To examine the association between vertebral dose and hematologic toxicity, the first cervical to the fifth lumbar vertebrae were contoured using an automatic contouring tool based on a Hounsfield unit threshold for bone, then edited. Contours excluded the vertebral canal.

Follow-up

Patients were monitored during RT with weekly clinical examinations, weight measurements and laboratory testing. Patients returned for follow-up examinations with repeat laboratory testing and imaging to monitor for disease control at one month then every 2–3 months. Toxicities were reported according to the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) Radiation Morbidity Scoring Criteria. 2). In addition to scoring criteria for hematologic toxicity, percentages of baseline blood counts were measured to correct for any differences in absolute blood counts, minimizing effects of confounding factors that might affect blood counts prior to CSI.

Statistics

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were evaluated using Kaplan-Meier estimates and compared using the log-rank test. Clinical and patient factors were compared using the Pearson’s chi-squared or the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon tests, as appropriate. Multivariate linear regression was used to analyze hematologic toxicity endpoints as a function of the mean vertebral dose and treatment modality (x-CSI versus p-CSI). Statistics were performed using the Stata software package (StataCorp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Patient and tumor characteristics by treatment group are described in table 1. p-CSI and x-CSI groups were statistically well-matched, with equivalent CSI and total radiation doses. x-CSI patients had more advanced Chang stage (Chang M1-4, n=6, 29%) than p-CSI patients (n=1, 5%; p=0.05), although the number of high risk patients was similar between groups. Five patients (26%) received concurrent chemotherapy with p-CSI as well as with x-CSI (24%; p=NS) and four p-CSI patients (21%) received chemotherapy prior to CSI compared with seven x-CSI patients (33%; p=NS). There were no statistically significantly differences in blood counts at the beginning of CSI between groups (table 2).

Table 1.

Patient, tumor and treatment characteristics

| Proton CSI (n=19) | Photon CSI (n=21) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median (range) | Median (range) | |

| Age at RT (years) | 29.9 (16.9–49.9) | 32.7 (16.6–60.4) |

| Follow-up (months) | 26.3 (11–63)† | 57.1 (4–103)† |

| Height (cm) | 175 (154–191) | 179 (147–194) |

| Gender | n (%) | n (%) |

| Male | 14 (74%) | 12 (57%) |

| Female | 5 (26%) | 9 (43%) |

| Chang Stage | ||

| M0 | 18 (95%)* | 15 (71%)* |

| M1 | 0 | 1 (5%) |

| M2 | 1 (5%) | 0 |

| M3 | 0 | 4 (19%) |

| M4 | 0 | 1 (5%) |

| Gross residual tumor at RT | ||

| < 1.5 cm2 | 14 (74%) | 17 (81%) |

| ≥ 1.5 cm2 | 5 (26%) | 4 (19%) |

| Risk Group | ||

| Average | 14 (74%) | 14 (67%) |

| High | 5 (26%) | 7 (33%) |

| Histology | ||

| Classical | 13 (68%) | 16 (76%) |

| Desmoplastic | 6 (32%) | 4 (19%) |

| Anaplastic | 0 | 1 (5%) |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Any | 16 (84%) | 17 (81%) |

| Before RT | 4 (21%) | 7 (33%) |

| During RT | 5 (26%) | 5 (24%) |

| After RT | 15 (79%) | 13 (62%) |

| Prescribed CSI dose | ||

| 23.4–26 Gy | 6 (32%) | 4 (19%) |

| 30 Gy | 4 (21%) | 8 (38%) |

| 36–40 Gy | 9 (47%) | 9 (43%) |

| Prescription dose (Gy-RBE; Gy) | Median (range) | Mean (SD) | Median (range) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSI | 30.6 (23.4–36) | 30.9 (5.6) | 30.6 (23.4–40) | 31.9 (4.7) |

| Boost | 23.4 (18–30.6) | 23.7 (5.2) | 21.6 (14–30.6) | 21.5 (4.3) |

| Total | 54 (54–57.8) | 54.6 (1.1) | 54 (25.5–56) | 52.9 (6.3) |

| Mean normal structure dose (%) | ||||

| Thyroid (% CSI dose) | 0.009% (0.006–0.69%)‡ | 0.05% (0.16)‡ | 79% (54–86%)‡ | 78% (7.2)‡ |

| Right Cochlea (% total dose) | 60% (44–91%) | 65% (12.9) | 67% (50–97%) | 67% (10.8) |

| Left Cochlea (% total dose) | 69% (44–84%) | 65% (10.7) | 71% (54–100%) | 74% (13.4) |

| Pituitary (% total dose) | 63% (44–75%) | 61% (9.2) | 67% (50–75%) | 66% (6.7) |

| Vertebrae (% CSI dose) | 69% (58–120%)‡ | 73% (13.6)‡ | 100% (87–111%)‡ | 100% (5.4)‡ |

Abbreviations: CSI= Craniospinal irradiation; RT=Radiation therapy; SD=standard deviation

p= 0.05 comparing M0 with M1-4

p= 0.004

p<0.0001

Table 2.

Acute toxicity

| RTOG Radiation Morbidity Score | Proton CSI | Photon CSI |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Nausea/Vomiting* (n=40) | ||

| 0 | 4 (21%) | 2 (10%) |

| 1 | 10 (53%)‡ | 4 (19%)‡ |

| 2 | 5 (26%) | 15 (71%) |

| Dermatitis† (n=40) | ||

| 0 | 0 | 1 (5%) |

| 1 | 19 (100%) | 19 90%) |

| 2 | 0 | 1 (5%) |

| Hemoglobin (n=39) | ||

| 0 (>11 g/dL) | 15 (83%) | 11 (52%) |

| 1 (9.5–11) | 1 (6%)§ | 10 (48%)§ |

| 2 (5–<7.5) | 2 (11%) | 0 |

| White Blood Cells (n=39) | ||

| 0 (≥4 × 109/L) | 3 (17%) | 5 (24%) |

| 1 (3–<4) | 5 (28%) | 4 (19%) |

| 2 (2–<3) | 10 (56%) | 10 (48%) |

| 3 (1–<2) | 0 | 2 (10%) |

| Platelets (n=39) | ||

| 0 (≥100 × 109/L) | 16 (89%) | 15 (71%) |

| 1 (75–<100) | 1 (6%) | 5 (24%) |

| 2 (50–<75) | 1 (6%) | 0 |

| 3 (25–<50) | 0 | 0 |

| 4 (<25) | 0 | 1 (5%) |

| Weight loss (n=33) | ||

| ≤2% | 12 (63%) | 3 (21%) |

| >2–5% | 4 (21%)|| | 2 (14%)|| |

| >5%–10% | 3 (16%)¶ | 8 (57%)¶ |

| >10% | 0 | 1 (7%) |

| Blood counts at start of CSI | Median (Range) | Median (Range) |

| White blood cells | 5.9 (2.3–20.9) | 7.2 (2.6–15.8) |

| Hemoglobin | 13.5 (9.4–16) | 13.6 (10.7–16.2) |

| Platelets | 219 (136–396) | 258 (123–517) |

Abbreviations: CSI= Craniospinal irradiation

Grade 1: not requiring antiemetics; 2: requires antiemetics

Grade 1: faint erythema, dry desquamation; 2: bright erythema, patchy moist desquamation

p= 0.004 comparing grade 2 or greater nausea/vomiting

p= 0.04 comparing grade 1 or greater anemia

p= 0.02 comparing weight loss greater than 2%

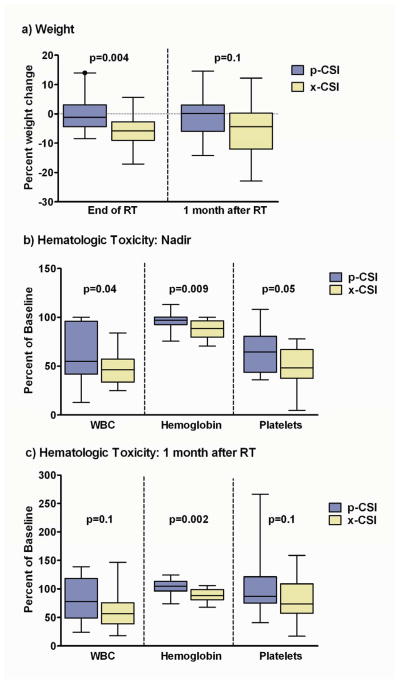

p-CSI patients lost less weight than x-CSI patients (median percent weight change −1.2% versus −5.8%, respectively; p=0.004; figure 2a). One month after RT, more p-CSI patients returned to their baseline weight compared to x-CSI patients, though the absolute difference was not statistically significant (+0.1% versus −4.4%; p=0.1; figure 2a). Significantly less p-CSI patients had greater than 5% weight loss than x-CSI patients (16% versus 64%; p=0.004). p-CSI patients also experienced less grade 2 or greater nausea/vomiting than x-CSI patients (26% versus 71%; p=0.004; table 2). Patients treated with x-CSI were more likely to have medical management of esophagitis than p-CSI patients (57% versus 5%, p<0.001). Three (14%) x-CSI patients received intravenous fluid support compared to zero p-CSI patients (p=0.09).

Figure 2.

The median percent change in weight at completion of radiation therapy (RT) for patients receiving proton craniospinal irradiation (p-CSI) was −1.2% (range +14 to −8.4%) compared to −5.8% for conventional photons (x-CSI; range +5.8 to −17.1%; p=0.004; panel a); One month after RT, the median percent change in weight +0.1% for p-CSI (range +14.6 to −14.2%) compared to −4.4% for x-CSI (range +12.2 to −23%; p=0.1; panel a). The median percentage of baseline white blood cells (WBC), hemoglobin and platelets at their nadir for patients receiving p-CSI (panel b: 55%, 97%, 65%, range 13–100%, 76–113%, 36–108%, respectively) compared to x-CSI (46%, 88%, 48%, range 25–84%, 71–100%, 5–78%; p=0.04, 0.009, 0.05, respectively); The median percentage of baseline WBCs, hemoglobin and platelets one month after RT (panel c; 78%, 105%, 87%, range 24–139%, 74–124%, 41–266%) compared to x-CSI (56%, 88%, 73%, range 18–146%, 68–106%, 17–158%; p=0.1, 0.002, and 0.1, respectively).

x-CSI patients had greater bone marrow suppression, reflected by reductions in peripheral white blood cells (WBC), hemoglobin and platelets compared to p-CSI patients (median percent baseline WBC 46% versus 55%, p=0.04; hemoglobin 88% versus 97%, p=0.009; platelets 48% versus 65%, p=0.05). Hemoglobin levels one month after x-CSI remained less than p-CSI (88% versus 105%, p=0.002), however, WBC and platelet differences were no longer statistically significant (WBC= 56% versus 78%, p=0.1; platelets= 73% versus 87%, p=0.1; figure 2b, 2c). The number of patients with grade 1 or greater anemia was less for p-CSI patients than x-CSI (17% versus 48%; p=0.04), with no difference in grade 1 or greater leukopenia or thrombocytopenia (table 2). Four p-CSI patients received concurrent chemotherapy (21%) compared to 5 receiving x-CSI (24%, p=NS).

Three x-CSI patients (14%) required bone marrow support including platelet transfusion for a patient who also received chemotherapy prior to RT, erythropoietin and colony stimulating factor administration for a patient also receiving concurrent chemotherapy, and packed red blood cell (PRBC) and platelet transfusions within one month of completion of CSI for a patient who also received chemotherapy after CSI. One p-CSI patient (5%) receiving concurrent chemotherapy required a unit of PRBCs. One patient in the x-CSI cohort, who received chemotherapy prior to CSI, discontinued treatment after 25.5 Gy because of severe thrombocytopenia. Two patients in the x-CSI arm (10%) experienced treatment breaks; one, who was also receiving concurrent chemotherapy, was hospitalized for persistent nausea/vomiting, and emesis and missed two treatment days and the other missed three days for dysphagia, nausea/vomiting and fatigue. No p-CSI patients had treatment breaks or hospitalizations related to CSI toxicity.

A subset analysis was performed, excluding patients who received chemotherapy prior to CSI (x-CSI, n=14; p-CSI n=15). Results were similar, with p-CSI patients having less weight loss than x-CSI patients (−1.2% versus −5.8%, respectively; p=0.03); as well as a smaller reduction in hemoglobin at nadir (median percent baseline 85% versus 94%, p=0.01) and at one month after RT (88% versus 102%, p=0.007). There was a trend towards a smaller reduction in WBCs with p-CSI at nadir (40% versus 55%, p=0.06) and at one month after RT (45% versus 87%, p=0.06). Smaller reductions in platelets at nadir (platelets 49% versus 54%) and at one month after RT (78% versus 83%) were not statistically significant.

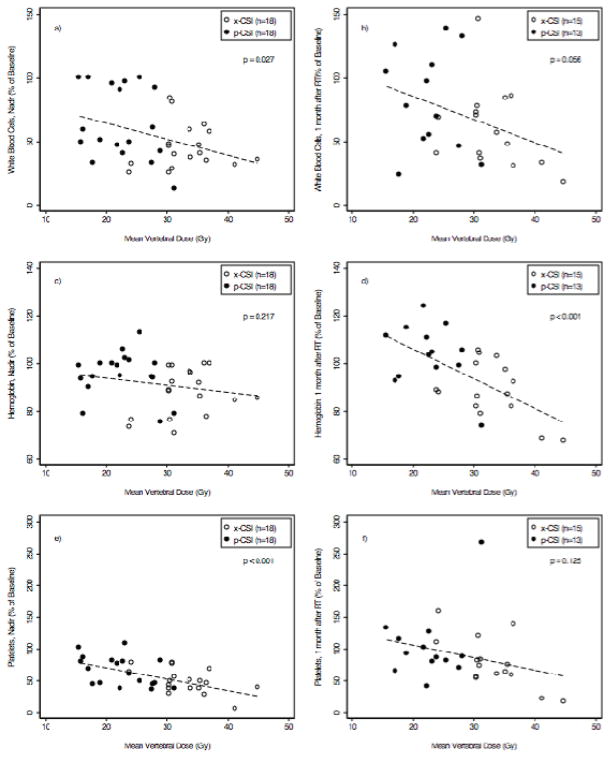

Vertebral dosimetry was performed to evaluate hematologic toxicity as a function of radiation dose delivered to the vertebrae (figure 4). There was a trend toward a reduction in WBCs, hemoglobin and platelets with increasing mean vertebral dose at the blood count nadir during RT, and one month after RT. This trend was statistically significant for WBCs (p=0.03, figure 4a) and platelets (p<0.001, figure 4e) at their nadir, but not one month after RT (figures 4b, 4f). The association between the percentage of hemoglobin and mean vertebral dose was not statistically significant at nadir (figure 4c), but became significant one month after RT (p<0.001, figure 4d).

The 2-year OS and PFS for patients treated with p-CSI were both 94%, compared to 90% and 85% respectively, for patients treated with x-CSI (; p=NS). One p-CSI patient (5%) had locoregional failure with the brain and spinal cord leptomeningeal disease, compared to three (14%) x-CSI patients with locoregional failures including one with leptomeningeal disease, and two with tumor-bed recurrences within the boost volume, one also with spinal cord leptomeningeal disease. The median follow-up for p-CSI patients was 26.3 months (range 11–63) compared to 57.1 months for x-CSI (range 4–103, p=0.004).

The mean and median CSI and total doses were similar for p-CSI and x-CSI patients with no statistically significant differences between groups. p-CSI patients had significantly lower mean thyroid (median 0.009% CSI dose vs. 79%, p<0.0001) and mean vertebral doses (median 69% vs. 100%, p<0.0001; table 1).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study examining p-CSI to reduce radiotherapy-related toxicity in adults with medulloblastoma. In this study, patients receiving p-CSI experienced lower rates of clinically significant gastrointestinal (GI) and hematologic toxicity. Limiting our study to adults with medulloblastoma allowed us to compare p-CSI with x-CSI in a group of patients with the same histology, who received similar treatment with chemotherapy and RT. However, the use of p-CSI to reduce toxicity would likely benefit all adult and pediatric patients requiring CSI. While more x-CSI patients had advanced Chang stage at presentation, there was no statistical difference in the number of high versus average-risk patients between groups. This resulted in no statistically significant differences in the dose delivered between x-CSI and p-CSI patients, allowing for comparison of acute toxicities by treatment modality.

GI toxicities from CSI include nausea/vomiting, dysphagia, anorexia and weight loss, all of which can potentially prolong recovery or cause treatment interruption. GI toxicities are relatively common and when refractory to medication, can affect outcomes and quality of life(5, 12, 13). In this study, patients receiving p-CSI had significantly less weight loss, nausea/vomiting, and medical management of dysphagia when compared to x-CSI. Two patients in the x-CSI cohort had short treatment interruptions due to GI toxicity, compared to none in the p-CSI arm. The reduction in GI toxicity can be attributed to significantly lower radiation doses to the esophagus, stomach, and bowel (figure 1). Reductions in acute GI toxicity using p-CSI may improve quality of life during treatment and throughout recovery. Further follow-up may help determine whether reductions in radiation dose to the GI tract and acute GI toxicity can decrease late effects such as bowel obstructions, gastric ulcers, and GI bleeding.

Hematologic toxicity from radiation damage to bone marrow in the spinal column is another important side effect of CSI. Because many patients receive chemotherapy before, during or after CSI, limiting unnecessary radiation to bone marrow may decrease severe hematologic toxicity, which in turn, may improve clinical outcomes(5, 13–17). Prior reports show more hematologic toxicity in younger patients, however, this toxicity occurs frequently in adults(5, 15, 17). Hematologic toxicity from CSI may limit a patient’s ability to tolerate a full course of chemotherapy after CSI, administered either for consolidation or as salvage for recurrence. Vertebral body-sparing p-CSI has been proposed to reduce hematologic toxicity in patients whose vertebrae are fully developed, since vertebral body deformation associated with radiation dose gradients across growing bones in pediatric patients is no longer a concern. The mean vertebral radiation dose in this study was significantly associated with acute hematologic toxicity. A dose-dependent reduction in blood counts during RT was observed for WBCs and platelets, however the reduction in hemoglobin was not evident until one month after RT, because of red blood cells’ relatively long half-life. The association between radiation dose and blood counts supports the use of vertebral body-sparing p-CSI to reduce acute bone marrow toxicity.

In the current study, adults receiving p-CSI experienced significantly smaller reductions in blood counts than patients receiving x-CSI. All three grade 3 or greater hematologic toxicities that occurred in this study were in x-CSI patients. Specifically, two developed grade 3 leukopenia, and one had grade 4 thrombocytopenia resulting in discontinuation of RT at 25.5 Gy. No other patients experience a treatment break related to hematologic toxicity. In addition to radiation dose, chemotherapy administration is an important cause of hematologic toxicity during RT. In this study, the percentage of patients receiving concurrent chemotherapy was equivalent between groups. More patients in the x-CSI arm received chemotherapy prior to CSI (33% vs 21%) although the difference was not statistically significant and initial blood counts prior to CSI were equivalent between groups. Furthermore, a subset analysis excluding patients who received chemotherapy prior to CSI was performed and even in this smaller subset of patients, results were similar. This suggests that differences in blood counts between p-CSI and x-CSI groups cannot be attributed to the imbalance in patients receiving chemotherapy prior to CSI. It is possible that p-CSI can impact long-term disease outcomes not only by allowing more patients to complete their prescribed initial chemotherapy and CSI, but also by improving a patient’s tolerance for additional chemotherapy if necessary after RT. Further study is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

This study is limited by small patient numbers and is subject to bias inherent in retrospective studies; however a prospective equivalency study of these two modalities would be difficult to perform given the large number of patients required. This study does not compare PBRT to other technical advances proposed to reduce CSI toxicity including IMRT, electrons, tomotherapy, and volumetric modulated arc therapy, however these techniques still have exit dose and other dosimetric challenges that would likely make them inferior to PBRT. While, early OS and PFS results are consistent with other studies and show no differences between p-CSI and x-CSI(1, 3, 4, 6, 12, 13), longer follow-up will be necessary to assess local control, and survival after p-CSI, especially given the risk of late local recurrence in medulloblastoma(1, 6). Longer follow-up may also help determine whether p-CSI can mitigate late toxicities in long-term survivors including subsequent primary malignancies, radiation-related heart disease, and thyroid dysfunction(8, 10).

Intensive treatment can improve outcomes for adults and children with medulloblastoma, but is associated with significant adverse effects. For this reason, it is critical to find ways to reduce risks of acute and late toxicities and improve quality of life. p-CSI reduces acute GI and hematological toxicity in adults with medulloblastoma and warrants further consideration in the treatment of patients requiring CSI.

Figure 3.

The mean vertebral dose for proton craniospinal irradiation (p-CSI) and photon CSI (x-CSI) plotted against the percentage of baseline white blood cell, hemoglobin and platelet counts measured at completion of radiation therapy (RT; panels a, c, and e, respectively) and one month after RT (panels, b, d, and f, respectively). Dotted lines represent the association between blood counts and mean vertebral dose with p values representing the statistical significance of the association.

SUMMARY.

Craniospinal irradiation (CSI) plays an important role in management of adults with medulloblastoma, but is associated with significant toxicity. Acute toxicities for adult medulloblastoma patients treated with traditional photon CSI were compared with patients treated with proton CSI. Patients treated with proton CSI experienced less weight loss, nausea/vomiting, and hematologic toxicity. Proton CSI reduces treatment-related morbidity in adults requiring CSI.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Notification

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Smoll NR. Relative survival of childhood and adult medulloblastomas and primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) Cancer. 2012;118:1313–22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Remke M, Hielscher T, Northcott PA, et al. Adult medulloblastoma comprises three major molecular variants. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2717–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.9373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunschner LJ, Kuttesch J, Hess K, et al. Survival and recurrence factors in adult medulloblastoma: the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience from 1978 to 1998. Neuro-oncology. 2001;3:167–73. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/3.3.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai R. Survival of patients with adult medulloblastoma: a population-based study. Cancer. 2008;112:1568–74. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang EL, Allen P, Wu C, et al. Acute toxicity and treatment interruption related to electron and photon craniospinal irradiation in pediatric patients treated at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:1008–16. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merchant TE, Wang MH, Haida T, et al. Medulloblastoma: Long-Term Results for Patients Treated with Definitive Radiation Therapy During the Computed Tomography Era. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;36:29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Packer RJ, Gajjar A, Vezina G, et al. Phase III study of craniospinal radiation therapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed average-risk medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4202–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brodin NP, Vogelius IR, Maraldo MV, et al. Life years lost-comparing potentially fatal late complications after radiotherapy for pediatric medulloblastoma on a common scale. Cancer. 2012;118:5432–40. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon M, Shin DH, Kim J, et al. Craniospinal irradiation techniques: a dosimetric comparison of proton beams with standard and advanced photon radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:637–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fossati P, Ricardi U, Orecchia R. Pediatric medulloblastoma: Toxicity of current treatment and potential role of protontherapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:79–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yom SS, Frija EK, Mahajan A, et al. Field-in-field technique with intrafractionally modulated junction shifts for craniospinal irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1193–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ang C, Hauerstock D, Guiot M, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Medulloblastoma in Adults. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:603–607. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rieken S, Mohr A, Habermehl D, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors of radiation therapy for medulloblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:e7–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abd El-Aal HH, Mokhtar MM, Habib EE, et al. Medulloblastoma: conventional radiation therapy in comparison to chemo radiation therapy in the post-operative treatment of high-risk patients. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2005;17:301–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jefferies S, Rajan B, Ashley S, et al. Haematological toxicity of cranio-spinal irradiation. Radiother Oncol. 1998;48:23–7. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(98)00024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silvani A, Gaviani P, Lamperti E, et al. Adult medulloblastoma: multiagent chemotherapy with cisplatinum and etoposide: a single institutional experience. J Neurooncol. 2012;106:595–600. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marks LB, Cuthbertson D, Friedman HS. Hematologic toxicity during craniospinal irradiation: the impact of prior chemotherapy. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1995;25:45–51. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950250110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]