Abstract

Objectives

The mechanisms promoting the focal formation of rupture-prone coronary plaques in vivo remain incompletely understood. This study tested the hypothesis that coronary regions exposed to low endothelial shear stress (ESS) favor subsequent development of collagen-poor, thin-capped plaques.

Methods and Results

Coronary angiography and three-vessel intravascular ultrasound were serially performed at five consecutive time-points in vivo in five diabetic, hypercholesterolemic pigs. ESS was calculated along the course of each artery with computational fluid dynamics at all five time-points. At follow-up, 184 arterial segments with previously identified in vivo ESS underwent histopathologic analysis. Compared to other plaque types, eccentric thin-capped atheromata developed more in segments that experienced lower ESS during their evolution. Compared to lesions with higher preceding ESS, segments persistently exposed to low ESS (<1.2Pa) exhibited reduced intimal smooth-muscle cell (SMC) content; marked intimal SMC phenotypic modulation; attenuated procollagen-I gene expression; increased gene and protein expression of the interstitial collagenases matrix-metalloproteinase (MMP)-1, -8, -13, and -14; increased collagenolytic activity; reduced collagen content; and marked thinning of the fibrous cap.

Conclusions

Eccentric thin-capped atheromata — lesions particularly prone to rupture — form more frequently in coronary regions exposed to low ESS throughout their evolution. By promoting an imbalance of attenuated synthesis and augmented collagen breakdown, low ESS favors the focal evolution of early lesions towards plaques with reduced collagen content and thin fibrous caps — two critical determinants of coronary plaque vulnerability.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, collagen, metalloproteinases, endothelial shear stress, natural history

While advanced plaques that rupture and trigger most acute coronary events have well-defined morphology1 and histologic characteristics,2,3 the preceding local environment and the mechanisms that promote the evolution of early lesions towards rupture-prone thin-capped atheromata (TCA) remain largely unknown. Low regional endothelial shear stress (ESS) promotes focal plaque development and progression4-8 and critically influences plaque vulnerability.9,10 Previous studies have established the mechanistic link between low ESS and atherogenesis in vitro,11-13 but the mechanisms whereby low ESS favors the localization of rupture-prone coronary lesions in vivo remain poorly understood. This study explored in particular two issues with important clinical implications not addressed in prior studies: the in vivo effect of ESS environment on (i) local collagen metabolism; and (ii) smooth muscle cell (SMC) phenotype.

Interstitial collagen strengthens the fibrous cap and likely enhances its resistance to rupture.3,14 Members of the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family with collagenase activity, including MMP-1, -8, -13, and the activator of MMP collagenases, MMP-14, weaken the plaque by degrading collagen fibers.14-17 Low ESS associates with increased expression of extracellular matrix-degrading enzymes ex vivo,18 and with the formation of collagen-poor carotid lesions in mice.19 Previous studies, however, used isolated cells or examined only two time points to assess natural history — approaches which may not reflect the complexity and dynamic nature of atherosclerotic disease.9,20 While low ESS induces elastolytic enzymes in coronary atheroma,21 the in vivo effect of ESS on the regional expression of collagen-degrading enzymes — and thereby on the local control of collagen content — throughout the progression of individual coronary lesions remains unknown.

The content and synthetic capacity of collagen-producing SMCs contribute centrally to regulating plaque collagen turnover.14,22 Abundance of intimal SMCs favors plaque quiescence, whereas the relative absence of SMCs2,3 and extensive phenotypic modulation23 both characterize fatally disrupted human coronary plaques. Low ESS associates with SMC phenotypic modulation24 and apoptosis in vitro.25 The in vivo role of ESS in regulating SMC content and functions, and their implications concerning the heterogeneity of coronary plaque manifestations, have undergone only minimal exploration.

This study hypothesized that coronary arterial regions exposed to low ESS more commonly progress towards eccentric TCA morphology — a lesion type implicated in plaque rupture and thrombosis in humans.1,2 Testing this hypothesis involved in vivo serial profiling of ESS at five consecutive time points over the course of plaque development, followed by histological analysis of the same lesions with previously identified in vivo ESS. Considering the critical impact of collagen on the structural integrity of coronary atheromata3,14-17, a secondary goal evaluated the association of ESS with the local control of plaque collagen content. We therefore assessed the amount and phenotype of SMCs, and the expression and activity of MMP-collagenases in lesions that originated from, and evolved through, substantially different ESS environments. We analyzed diabetic, hyperlipidemic pigs capable of developing plaques very similar to those observed in humans.10,21,26

Methods

Materials and Methods are presented in detail in the Online-only Data Supplement.

Results

Dynamic Course of Local ESS in Individual Arterial Segments

Local ESS exhibited substantial changes over time (weeks 4 to 36) throughout the progression of plaque in individual 3mm-long arterial segments (n=184). A substantial proportion of segments with low ESS, ranging between 12.4% and 47.3% over time, changed to higher ESS at the next time point. Similarly, a proportion ranging between 14% and 44.3% of segments with higher ESS at each time point changed to low ESS at the following time point (Supplemental Figure III). These dynamic changes of ESS related to variable responses of the vessel wall and lumen dimensions throughout the course of plaque evolution in each segment (Supplemental Figures IV and V).

Because low ESS associates in a time- and level-dependent manner with the rate of subsequent plaque progression4-8 and with the magnitude of high-risk plaque characteristics,10,21 we identified the minority of segments (n=75; 41%) that remained in persistently low ESS throughout their evolution, defined by time-averaged ESS<1.2 Pa through all five time points (weeks 4 to 36). All our analyses compared these segments by histology at follow-up (week 36) to all other segments that developed in a higher ESS environment over time, defined by time-averaged ESS ≥1.2 Pa (n=109; 59%).

Eccentric Thin-Capped Atheromata Develop in Regions with Persistently Low ESS

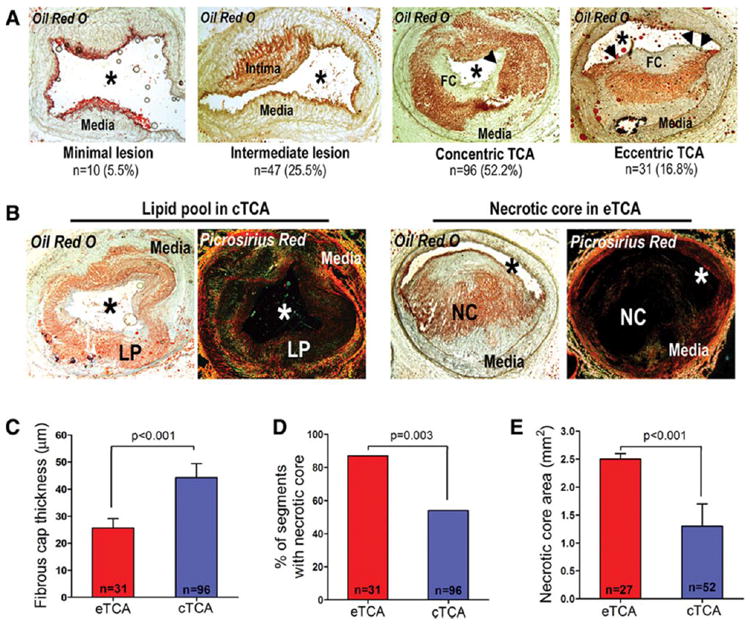

Segments were classified at follow-up as segments with minimal lesion (n=10; 6%), with intermediate lesion (n=47; 25%), concentric TCA (cTCA) (n=96; 52%), and eccentric TCA (eTCA) plaque morphology (n=31; 17%) (Figure 1A). We focused on the natural history of eTCA as the highest-risk plaque type among all heterogeneous segments, because thin-capped plaques with eccentric morphology appear particularly prone to rupture and cause acute coronary events in humans.27,28 In line with these human data,27,28 we found that eTCA had thinner fibrous caps, more frequently contained true necrotic cores, and had larger necrotic core areas compared with cTCA (Figures 1B-1E).

Figure 1.

(A) Classification of segments at follow-up as segments with minimal lesion, intermediate lesion, concentric thin-capped atheroma (cTCA), and eccentric thin-capped atheroma (eTCA) plaque morphology. (B) Representative cTCA containing a collagen-positive lipid pool (LP; left) versus an eTCA containing a necrotic core (NC), i.e., lipid-rich region with absence of collagen (right). (C-E) eTCA had thinner fibrous caps, more frequently contained true NC, and had greater NC area compared to cTCA.

We assessed the study’s primary endpoint — the relation between the preceding local ESS over time and subsequent development of eTCA at follow-up — using a dual approach: (i.) a plaque type-based approach, comparing the preceding ESS in eTCA with all other plaque types; and (ii.) an ESS-based approach, prospectively comparing the proportion of segments with persistently low ESS with segments with higher ESS that subsequently progressed to eTCA.

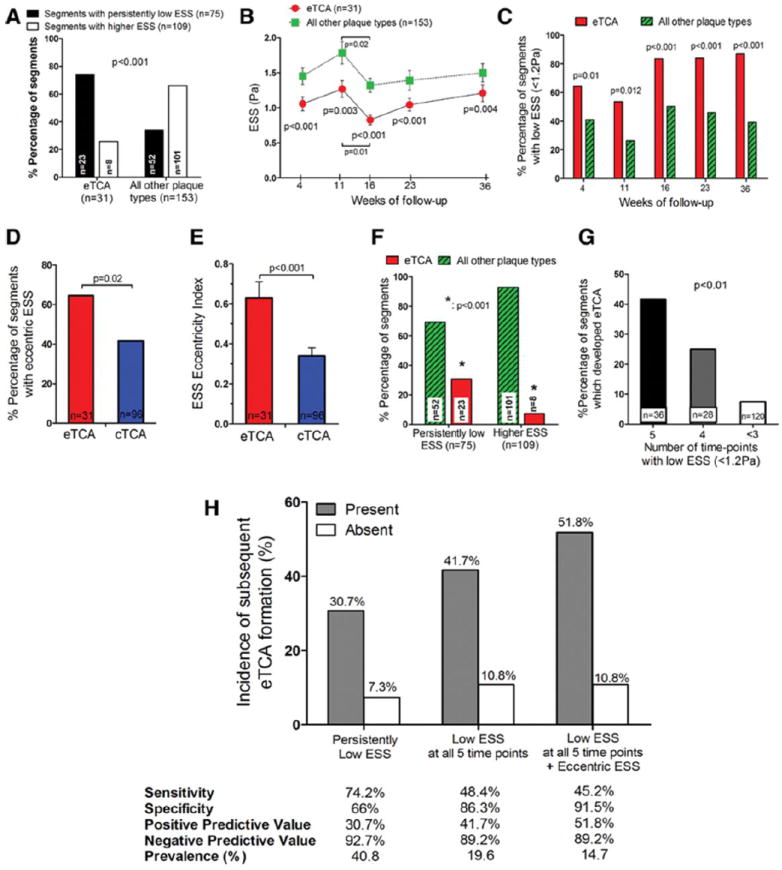

eTCA arose more frequently from persistently low-ESS segments than from higher-ESS segments (74% vs. 26% of all eTCA, respectively). eTCA originated from persistently low-ESS segments more frequently (74% of eTCA), compared to all other plaque types that originated from persistently low-ESS segments (34% of non-eTCA lesions; p<0.0001) (Figure 2A). The preceding ESS in eTCA was lower at all five time points compared to all other, non-eTCA plaque types (Figures 2B and 2C). The significant decrease of ESS at week 16 in both eTCA and non-eTCA segments associated with substantial increase of vessel and lumen dimensions at this time-point (Supplemental Figure VI). Segments with eTCA plaque morphology at follow-up had a higher time-averaged ESS eccentricity index, and more commonly had an eccentric ESS pattern compared to segments with non-eTCA morphology (Figures 2D-E).

Persistently low-ESS segments subsequently resulted in eTCA more frequently than did higher-ESS segments (31% vs. 7%, respectively; p<0.0001) (Figure 2F). The incidence of eTCA morphology at follow-up was highest in segments with low ESS at all 5 individual time points (Figure 2G). The positive predictive value of persistently low ESS to identify subsequent eTCA morphology rose from 31% (Supplemental Table 2S) to 52% when low ESS at all 5 time points and eccentric ESS were both present (Figure 2H). The negative predictive value of persistently low ESS to predict subsequent eTCA morphology was even higher (92.7%) and it remained very high (89.2%) when the combination of low ESS at all 5 time points plus eccentric ESS was present (Figure 2H).

Figure 2.

(A) eTCA formed more frequently in segments with persistently low ESS over time (23 of 31 eTCA; 74%) than in higher-ESS segments (8 of 31 eTCA; 26%; p<0.0001). In contrast, all other plaque types rarely derived from persistently low-ESS segments (52 of 153 non-eTCA lesions; 34%). Compared to all other plaque types, eTCA had lower levels of ESS (B), and were more frequently exposed to low ESS (<1.2 Pa) (C) at all five time points throughout their progression (weeks 4 to 36). Segments that developed eTCA more frequently had eccentric ESS (D) and had a higher ESS Eccentricity Index (E) compared to segments that developed cTCA.(F) Segments with persistently low ESS resulted in eTCA more frequently (23 of 75 low-ESS segments; 30.7%) compared to higher-ESS segments that resulted in eTCA (8 of 109 higher-ESS segments; 7.3%; p<0.0001). (G) Incidence of eTCA morphology at follow-up in relation to the number of individual time points with low ESS <1.2Pa. (H) Incidence of eTCA plaque morphology for segments with vs. those without presence of persistently low ESS; low ESS at all 5 time points; and low ESS at all 5 time-points plus eccentric ESS.

Reduced Intimal Collagen Content in Arterial Segments with Persistently Low ESS

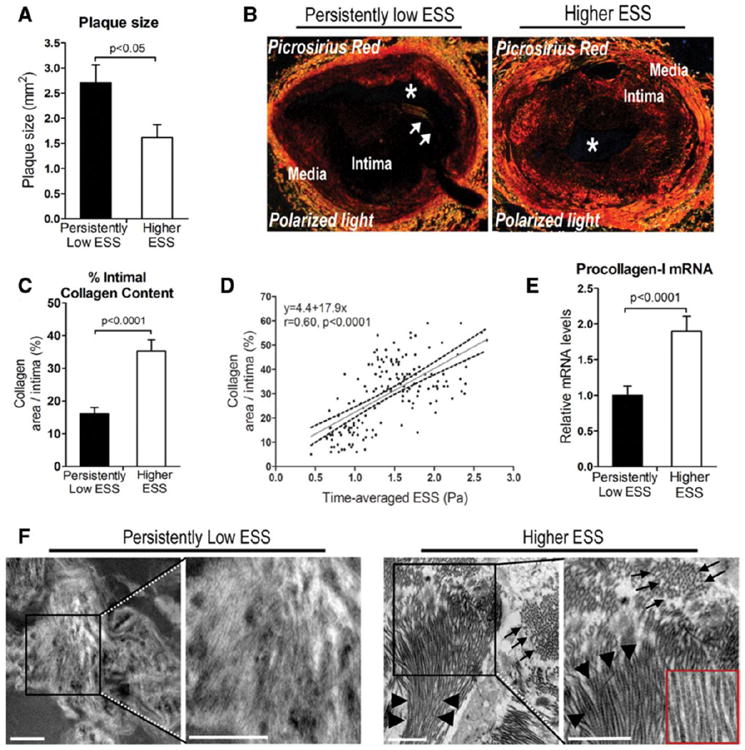

Persistently low-ESS segments were not only larger at follow-up (Figure 3A), but they also differed substantially in plaque composition. Persistently low-ESS segments versus higher-ESS segments showed decreased intimal content of fibrillar collagen (Figures 3B and 3C). Time-averaged ESS as a continuous variable associated significantly with intimal collagen content (r=0.60, p<0.0001); for each decrease of time-averaged ESS by 1.0 Pa, intimal collagen content decreased by 17.9% (Figure 3D). Persistently low-ESS segments also showed reduced expression of procollagen type-I mRNA that encodes the main precursor molecule of fibrillar collagen type-I (Figure 3E), indicating that the reduced collagen content in low-ESS segments derives at least in part from decreased procollagen–I production. TEM analysis documented few collagen fibers at the fibrous cap region of persistently low-ESS segments, relative to the abundant, well-organized collagen fibers in higher-ESS segments (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

(A) Quantification of plaque size at follow-up in segments with persistently low ESS vs. higher ESS over time. (B) Picrosirius-red staining viewed under linearly polarized light shows reduced fibrillar collagen and thin fibrous cap (arrows) in a representative segment with persistently low ESS versus higher preceding ESS. Asterisks denote the lumen. (C) Quantification of intimal collagen content. (D) Association of intimal collagen content with the time-averaged ESS; dashed lines represent 95% CI for the regression line. (E) mRNA expression of procollagen type-I. (F) Transmission electron microscopic analysis at the fibrous cap region shows scarce collagen fibers without molecular organization typical of mature interstitial collagen in a representative low-ESS segment (left), versus abundant, well-organized collagen fibers in a higher-ESS segment (right). Areas selected by black box are shown at higher magnification. Arrows indicate traverse view, and arrowheads indicate longitudinal view of collagen fibers. Note the periodicity of collagen fibers in the inset in the higher-ESS section. Similar observations pertained to different low-ESS versus higher-ESS segments (n=8 for each group). Bar=500 nm.

Reduced Content and Marked Phenotypic Modulation of Intimal SMCs in Arterial Segments with Persistently Low ESS

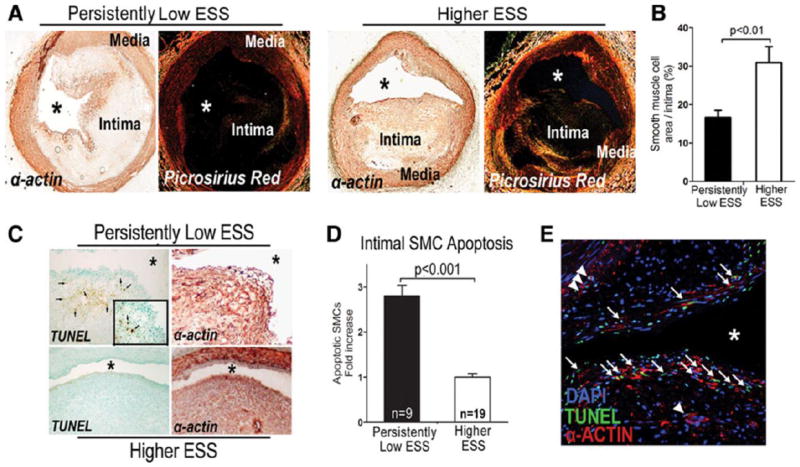

Persistently low–ESS segments showed decreased intimal SMC content compared with higher-ESS segments (Figures 4A and 4B). The α-actin-positive intimal area positively correlated to the collagen-stained area (r=0.80; p=0.001), a finding consistent with the function of SMCs as the main source of collagen in the atherosclerotic intima.

Figure 4.

(A) Immunostaining with α-actin shows reduced intimal SMC content in a representative segment with persistently low-ESS (left) versus higher preceding ESS (right). Picrosirius red-stained serial sections of the same segments show co-localization of α-actin with fibrillar collagen. (B) Quantitative analysis of intimal SMC content. (C) TUNEL staining and α-actin immunostaining in serial sections indicate more red-brown apoptotic nuclei (arrows) in α-actin-positive intimal areas in persistently low-ESS (upper panel) versus higher-ESS segments (lower panel). (D) Quantification of apoptotic SMCs. (E) Double α-actin immunofluorescent staining and TUNEL staining viewed with confocal microscopy in a low-ESS segment. Arrows indicate localization of apoptotic intimal SMCs at the fibrous cap region; arrowheads, deeper in the intima. Asterisk denotes the lumen.

Quantitative analysis of apoptotic nuclei that co-localized with α-actin-positive intimal areas in serial sections of selected segments demonstrated a threefold higher number of apoptotic cells in persistently low-ESS segments versus higher-ESS segments (Figures 4C-4D). Apoptosis of intimal SMCs in low-ESS segments was assessed directly by α-acting immunofluorescent staining combined with TUNEL staining (Figure 4E).

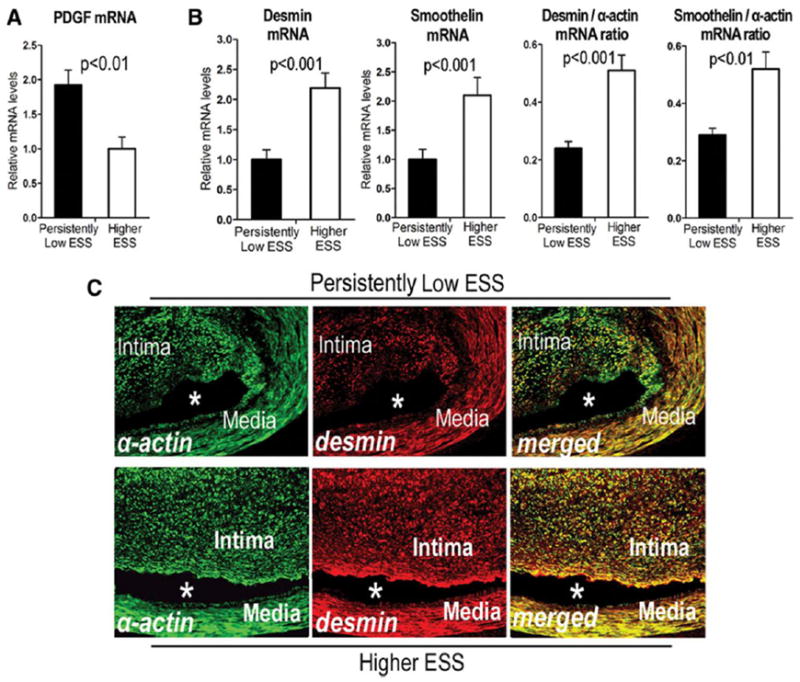

Persistently low-ESS segments versus higher-ESS segments showed increased mRNA levels of PDGF (Figure 5A), and decreased mRNA levels of desmin and smoothelin, charcteristic markers of unmodulated SMCs29,30 (Figure 5B). The desmin-to-α-actin ratio and the smoothelin-to-α-actin ratio — indices previously used to quantify the extent of SMC phenotypic modulation23,29,31 — were <1 in all segments, but these ratios fell particularly in persistently low-ESS segments (Figure 5B), suggesting that the reduced mRNA expression of desmin and smoothelin relative to α-actin observed in all segments was even more prominent in those with low ESS. Double immunofluorescent staining for α-actin and desmin affirmed reduced desmin expression relative to α-actin in the intima of persistently low-ESS segments (Figure 5C, upper panel), suggesting the presence of modulated SMCs, whereas these two proteins showed greater co-localization in the intima of higher-ESS segments (Figure 5C, lower panel). Desmin and α-actin co-localized in the tunica media, an arterial wall layer known to accommodate unmodulated, contractile SMCs.

Figure 5.

Relative mRNA levels of PDGF (A), desmin, smoothelin, and the desmin-to-α-actin and smoothelin-to-α-actin mRNA ratios (B) in persistently low-ESS versus higher-ESS segments. (C) Immunofluorescence for α-actin (green; left), desmin (red; middle), and double staining for both antigens (merged; right) in segments with persistently low ESS (top panel) and higher ESS (bottom panel). Note the preponderance of green in the intima of the low-ESS segment (upper right), indicating the presence of desmin-negative, modulated SMCs, and the orange color from the merged green and red in the intima of the higher-ESS segment (lower right), indicating desmin-positive, unmodulated SMCs. Asterisks denote the lumen.

Increased Expression and Activity of MMP Collagenases in Arterial Segments with Persistently Low ESS

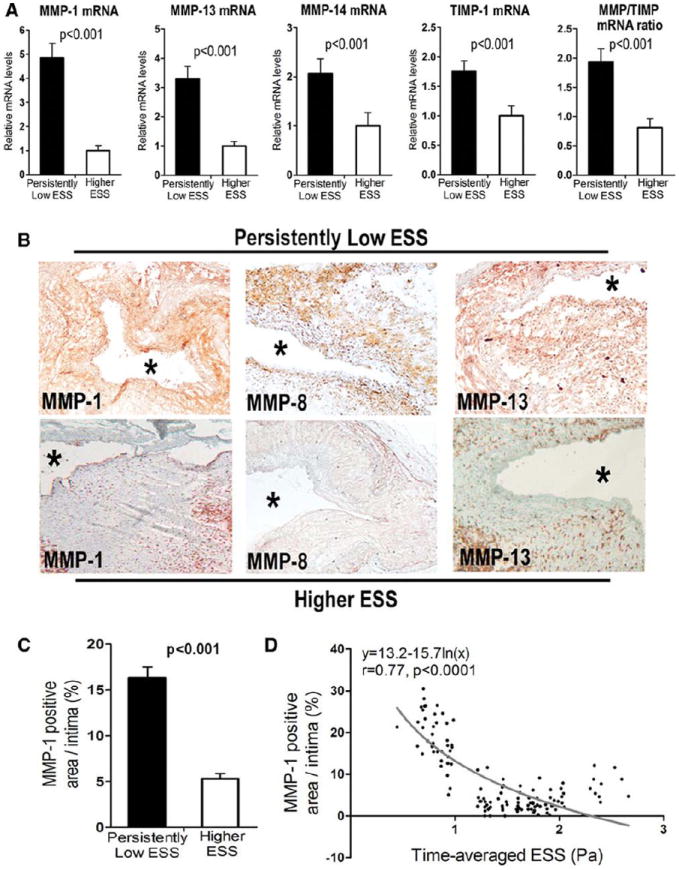

Segments with persistently low ESS versus higher ESS had increased levels of mRNAs that encode MMP-1, MMP-13, MMP-14 and TIMP-1 (Figure 6A), while TIMP-2 mRNA levels did not differ (not shown). Despite the parallel increase of the MMPs and one of their endogenous inhibitors (i.e., TIMP-1), persistently low-ESS segments had increased MMP/TIMP mRNA ratios (Figure 6A). Consistent with our mRNA results, persistently low-ESS segments exhibited greater MMP-1, MMP-8, and MMP-13 protein expression than higher-ESS segments (representative examples shown in Figure 6B). MMP-1, a major interstitial collagenase in humans,14 increased more than threefold in segments with persistently low ESS versus higher ESS, and its expression was inversely related to the time-averaged ESS (Figures 6C–6D).

Figure 6.

(A) Relative mRNA levels of MMP-1, MMP-13, MMP-14, TIMP-1, and the MMP/TIMP mRNA ratio in segments with persistently low ESS versus higher ESS. (B) Immunostaining shows greater protein expression of MMP-1, MMP-8, and MMP-13 in representative segments with persistently low ESS (upper panel) versus higher ESS (lower panel). Asterisks denote the lumen. (C) Quantification of MMP-1 immunostaining. (D) Association of MMP-1 protein expression with the time-averaged ESS, best described by a negative logarithmic relationship.

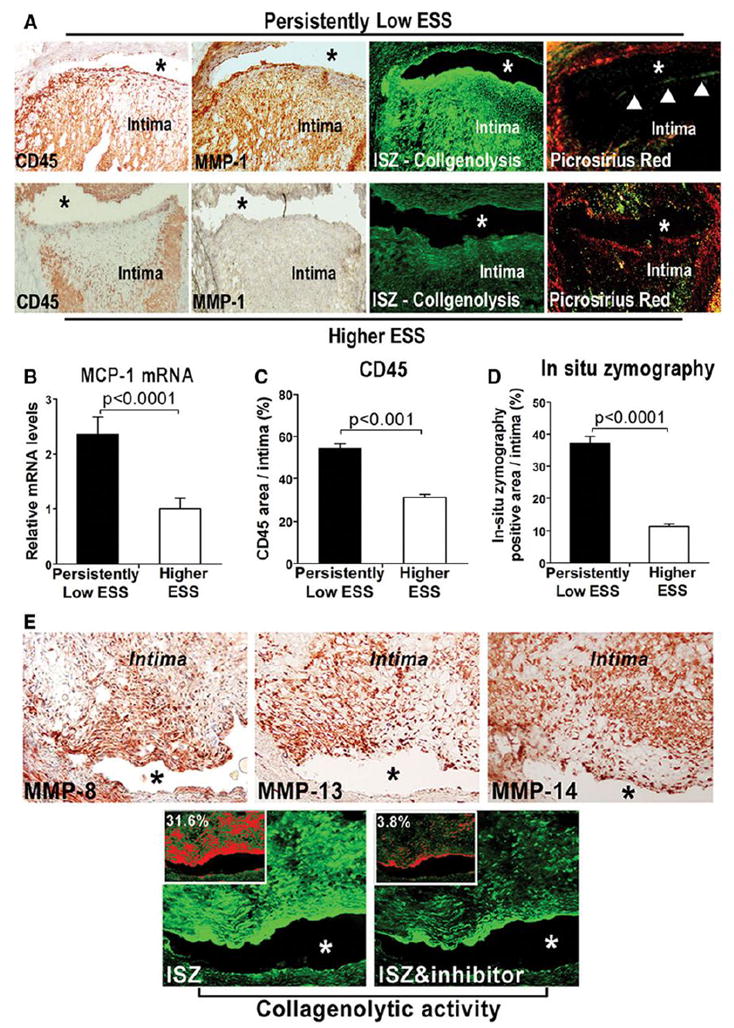

Persistently low-ESS segments showed more pronounced bright green fluorescence by ISZ than did higher-ESS segments, indicating cleavage of the collagen substrate (Figure 7A). The enhanced collagenolytic activity co-localized with pronounced leukocyte infiltration and MMP-1 protein expression, as well as with reduced intimal collagen content and pronounced fibrous cap thinning (Figure 7A), consistent with the contribution of MMP-1 to collagen degradation in a low-ESS milieu. Quantitative analyses showed higher mRNA expression of MCP-1, increased CD45-positive leukocyte content, and threefold greater collagenolytic activity in persistently low-ESS versus higher-ESS segments (Figures 7B–7D). In addition to MMP-1, enhanced protein expression of MMP-8, MMP-13, and of the collagenase activator MMP-14 in low-ESS segments co-localized with regions of marked collagenolysis (Figure 7E). Addition of the metallo-enzyme inhibitor EDTA (20 mM) abolished zymographic activity (Figure 7E), an indication that these MMPs contribute to collagenolytic activity.

Figure 7.

(A) Upper row: CD45 and MMP-1 immunostaining in serial sections of a representative low-ESS segment indicates marked MMP-1 expression, co-localization with inflammatory leukocytes, and intense green fluorescence by ISZ optimized for MMPs, indicating high collagenolytic activity. Picrosirius-red staining (right) shows reduced fibrillar collagen, and marked fibrous-cap thinning (arrowheads), in the same segment. Lower row: Reduced leukocyte infiltration (left), absence of MMP-1 staining, attenuated MMP-mediated collagenolytic activity, and high collagen content (right) in serial sections of a representative higher-ESS segment. Quantitative analyses of MCP-1 mRNA levels (B), intimal leukocyte content (C), and percentage area of intimal fluorescence by ISZ optimized for MMP (D). (E) Increased expression of MMP-8 (left), MMP-13 (middle), and MMP-14 (right) in serial sections of a representative low-ESS segment, and co-localization with marked collagenolytic activity as indicated by ISZ (lower panel; left). Addition of MMP-specific inhibitor EDTA abolishes zymographic activity (lower panel; right). Quantification of the percentage of intimal area with fluorescence intensity, shown in red in the insets, affirms the eightfold decrease of collagenolytic activity with the addition of EDTA in this lesion.

Discussion

Although advanced plaques that rupture and provoke acute coronary thrombosis in humans have a well-characterized morphology,1-3 the mechanisms that promote the focal progression of early lesion to rupture-prone plaques in vivo remain poorly understood. As all regions of the arterial tree experience similar exposure to traditional risk factors such as dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia, we hypothesized that the preceding local hemodynamic environment influences decisively the clinically crucial segmental nature of lesions prone to rupture. To test our hypothesis we performed a natural history study, uniquely designed with multiple sessions of in vivo vascular profiling over the course of plaque development and with subsequent histopathology in atherosclerotic pigs, which develop lesions similar to human coronary atherosclerosis.26 While local ESS displayed a dynamic course over time, regions with persistently low, eccentric ESS throughout their evolution tended to give rise to eTCA — a plaque type associated in humans with acute disruption2,3,27 and, prospectively, with adverse clinical events.1,28 Persistently low, eccentric ESS had a remarkably high negative predictive value (>90%) for prediction of eTCA development, suggesting that high-risk coronary plaque development is extremely uncommon in the absence of these local hemodynamic conditions. These novel observations link to evidence presented here concerning the local control of atheroma collagen, an extracellular matrix macromolecule that critically influences plaque stability.14 Regions of low ESS associated with the formation of lesions with reduced SMC content and augmented expression and activity of collagenases, favoring attenuated synthesis and increased catabolism of collagen — an imbalance that likely contributes to the evolution of early lesions to collagen-poor, thin-capped atheromata. Our findings thereby extend prior mechanistic studies which directly link low ESS to atherogenesis and plaque inflammation,11-13,18,19 and they support a critical role of low, eccentric ESS in the development of high-risk coronary plaque in vivo.

The Dynamic Nature and Predictive Value of Local ESS

Previous investigations consistently associated low ESS with plaque progression and destabilization.4-10,21 In addition to ESS magnitude, circumferential ESS heterogeneity has also been to linked to plaque instability.32,33 These previous studies were nonetheless limited because they defined high-risk plaque by IVUS9 — a modality insufficient to assess plaque composition — or because they examined only two time points,4 interpreting local vascular behavior as a function of a single value of preceding ESS. Local ESS patterns, however, depend both on vascular geometric configurations6 and on atherosclerotic plaque-induced alterations of arterial geometry and wall remodeling, which may all change over time.9,20 This study overcame those fundamental limitations by uniquely combining serial in vivo profiling of local ESS in the entire coronary tree, from early plaque initiation to the development of advanced atheroma, with assessment of subsequent plaque morphology by histologic examination — the ultimate standard for tissue characterization. Our findings advance the current appreciation of low ESS as a critical pro-atherogenic factor in two important ways. First, we demonstrate that local ESS in regions where plaque forms and progresses can vary substantially over time; these dynamic changes of local ESS result from variable contributions of the arterial wall’s remodeling response, and thereby from dynamic changes of vessel and lumen dimensions over the course of local plaque progression (Supplemental Figures IV-VI). Second, we show that a local environment of persistently low, eccentric ESS characterizes only a small proportion of developing lesions and correlates tightly with the focal formation of eTCA — a morphology associated in humans with rupture and fatal thrombotic events. Previous studies using a single snapshot of baseline ESS documented an exposure-response relation between the magnitude of low ESS and the level of high-risk plaque characteristics.10,21 Our present study now extends those findings over time by showing an exposure-response relation between the duration of exposure to low ESS and the propensity to high-risk plaque development; the longer an arterial regions experiences low ESS throughout its evolution, the more likely it will progress towards a rupture-prone eTCA. Novel evidence presented here, associating low ESS with the pathobiology of extracellular matrix metabolism implicated in high-risk plaque formation, substantiates these observations.

Current imaging modalities have focused on the in vivo detection of advanced TCA before they rupture and thus become symptomatic.1 But identification of high-risk coronary plaques a step earlier in their natural history — i.e., prospective identification of early lesions before they progress towards rupture-prone TCA — remains a major clinical challenge. Low ESS, a lesion-related factor now measured in large-scale clinical studies,4 predicts subsequent plaque enlargement in humans.4,5 Our present experimental results advance these clinical observations and suggest that in vivo profiling of ESS magnitude and eccentricity might enhance the prediction not only of plaque enlargement, but also of high-risk plaque formation early in its natural history. We show that persistently low ESS is a lesion-related characteristic conducive to eTCA development (with a positive predictive value of 30%), and that the combination of persistently low and eccentric ESS increased the positive predictive value to over 50%. An even more important finding of this study is that high-risk plaque is highly unlikely to develop in the absence of these local hemodynamic characteristics (with a negative predictive value over 90%). Not all arterial segments with these characteristics developed eTCA, a finding that indicates that systemic and local factors not explored here also affect high-risk plaque development, likely including the magnitude of hypercholesterolemia,34 wall stress, disturbed flow6 and strain.32

Association of Low ESS with SMC Content and Phenotype

This in vivo study also investigated the association of low ESS with the local control of plaque collagen. We found reduced content and more phenotypic modulation of intimal SMCs— the main collagen-producing cells in the atheroma — in coronary plaques previously exposed to low ESS. Vascular SMC phenotype can range from an unmodulated state with high content of contractile proteins, to a modulated (so-called “synthetic”) state characterized by low content of contractile proteins and evidence of augmented protein synthesis.30 Late markers of unmodulated SMCs — such as smoothelin, desmin, or myosin — fall to a varying extent during the progression of human35 and pig atherosclerosis,31 typifying the transition of intimal SMCs to a more modulated state, while maintaining expression of α-actin.35 SMC modulation may promote plaque vulnerability,31 likely through the production of matrix-degrading enzymes.36 Our present findings add to the current appreciation of intimal SMC scarcity,2,3 SMC apoptosis,37,38 and profound SMC modulation23,29,36 as features of unstable plaques by demonstrating a novel link between the preceding ESS milieu and the subsequent status of SMC content and character. Our in vivo findings in a large-animal, human-like model of disease add to the results of previous in vitro experiments that mechanistically link low ESS to SMC apoptosis,25 and furnish one potential mechanism whereby low ESS may favor the formation of SMC-poor, high-risk lesions. Our finding of increased PDGF expression in regions with low ESS may be one of possible mechanisms underlying the marked phenotypic modulation of intimal SMCs. PDGF is a growth factor that is up-regulated by low shear stress in cell-culture studies24,39 and amplifies SMC modulation in the atheroma.39

Local Regulation of Collagen Content Associates with the Preceding ESS

A dynamic balance between synthesis and enzymatic degradation actively regulates plaque collagen turnover,14 but the mechanisms responsible for the marked heterogeneity of collagen content along the atherosclerotic coronary vasculature have remained elusive. This study provides novel insight into the in vivo role of low ESS in the local regulation of collagen content and the focal formation of collagen-poor TCA. Modulated (“synthetic”) SMCs in low-ESS regions likely produced more collagen than the less modulated SMCs in higher-ESS regions.30 We found, however, substantially reduced levels of mRNA that encodes type-I procollagen and decreased intimal collagen content in regions with persistently low ESS. This seemingly paradoxical finding might result from the profoundly reduced SMC content in low-ESS regions, which likely outweighed the enhanced collagen-producing capacity of the modulated, yet scarce, SMCs. In addition, despite favoring modulated SMC morphology, low ESS may functionally suppress collagen synthesis by enhancing IFN-γ6 and by decreasing TGF-β,6 a potent promoter of collagen formation.40 Moreover, while collagenases in atheromata derive mainly from leukocytes,14 modulated SMCs also produce collagen-degrading MMP-841 (Supplemental Figure X) that might, along with other collagenases, contribute to collagen breakdown and reduced collagen accumulation in low-ESS regions.

MMP-collagenases participate decisively in the regulation of plaque collagen content.14-17 This study extends current knowledge by uniquely highlighting non-uniform expression of MMP-collagenases in different coronary lesions that evolved through different local ESS environments. Regions with persistently low ESS showed increased expression of MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-13, and MMP-14, preponderance over their endogenous inhibitors, and concomitant excess of metalloenzyme-mediated collagenolytic activity. The enhanced expression of MCP-1 in low-ESS regions may promote leukocyte infiltration, likely in concert with other chemo-attractants. Increased expression of MMP-collagenases, mainly by leukocytes, can initiate the proteolytic cleavage of interstitial collagens and set the stage for later steps of collagen’s catabolic cascade.14 Consequently, intense collagen digestion in inflamed lesions persistently exposed to low ESS likely drives the evolution of early lesions to advanced atheromata with reduced collagen content and marked fibrous-cap thinning — both critical steps in rendering a plaque conducive to rupture.

Attenuation of proteolytic activity in rabbits36,42 yielded collagen-rich atheromata despite the unmodulated phenotype of lesional SMCs36 — suggesting that the contribution of collagen degradation probably outweighs that of SMC-mediated synthesis to the regulation of plaque collagen content.42 In line with these previous experiments, in this study the net effect of decreased SMC content and augmented collagenolysis likely outweighed the ostensibly increased collagen-producing capacity of the modulated SMCs in low-ESS sites, resulting in collagen-poor plaques in regions exposed to pro-inflammatory ESS throughout their progression (Supplemental Figure XI).

While lesions in atherosclerotic pigs very closely resemble clinical coronary atherosclerosis,26 extrapolation of our findings to humans still requires caution, given the severely hyperlipidemic and diabetic experimental conditions. The present findings resemble remarkably, however, the observations from a large-scale clinical study (PREDICTION)4 that demonstrated greater plaque enlargement in coronary regions with low ESS.4 Our current observations advance prior mechanistic studies directly linking low ESS to atherogenesis in vitro,11-13,18 and they complement previous clinical observations4,5,7 in several important ways: by profiling individual lesions serially in vivo throughout their evolution we assessed for the first time the long-term effect of the temporally changing local ESS; we demonstrate how persistently low, eccentric ESS associates with the subsequent development of high-risk eTCA; and, most importantly, we explored in detail histopathologic features linking low ESS to the biology of high-risk plaque formation — an elusive goal in humans.

Our study might have benefited from a greater number of pigs. Its power increased, however, by profiling the entire length of 15 arteries at five consecutive time points, and analyzing a total of 184 arterial segments. While we may have introduced some selection bias in the samples we analyzed histologically, we were careful to include segments with various ESS trajectories over time, and selected about two-thirds of all 304 computationally defined segments. Arteries were not perfusion-fixed under pressure to preserve the ability to perform immunohistochemical and in situ zymographic analyses, which may have distorted the dimensions of the histological cross sections.

In conclusion, this study provides important new insights into the in vivo role of low ESS in the evolution of early lesions to high-risk coronary plaques. While local ESS may change substantially over time as plaques form and progress, eccentric TCA — lesions particularly prone to rupture and trigger thrombotic events in humans — are highly unlikely to develop in coronary regions that are not exposed to persistently low, eccentric ESS throughout their long-term evolution. In these regions with persistently low ESS, the combination of attenuated collagen synthesis and enhanced MMP-mediated collagen breakdown favors reduced collagen content and substantial thinning of the fibrous cap — characteristics that compromise plaque stability.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Local hemodynamic conditions critically affect atherosclerotic plaque development. This natural history study advances the current appreciation of low endothelial shear stress (ESS) as an important pro-atherogenic stimulus in several important ways. First, we demonstrate in a human-like, porcine model of coronary atherosclerosis that local ESS may change substantially over time as plaques form and progress. Second, we show that persistently low, eccentric ESS is a lesion-related factor conducive to subsequent development of eccentric thin-capped atehromata; high-risk plaques are highly unlikely to develop in the absence of these local characteristics. Third, we demonstrate that arterial regions exposed to persistently low ESS develop plaques with reduced SMC content, marked SMC phenotypic modulation, attenuated collagen synthesis and enhanced MMP-mediated collagen breakdown, thereby promoting the formation of collagen-poor, rupture-prone plaques. Early in vivo identification of high-risk lesions may guide the application of focused systemic treatments or selective local prophylactic interventions to avert the thrombotic complications of coronary plaque rupture.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Michelle Lucier, Gail McCallum, and Eugenia Shwartz for technical assistance, and Sara Karwacki for invaluable editorial assistance.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by grants from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Inc and Boston Scientific Inc; the George D. Behrakis Research Fellowship; the Hellenic Heart Foundation; the Hellenic Atherosclerosis Society; and by grants NIH R01 GM49039 (to P.L.) and RO1 GM49039 (to E.R.E.)

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:226–235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Virmani R, Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Farb A, Schwartz SM. Lessons from sudden coronary death: a comprehensive morphological classification scheme for atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1262–1275. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.5.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Libby P. Molecular bases of the acute coronary syndromes. From Bench to Bedside. Circulation. 1995;91:2844–2850. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.11.2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone PH, Saito S, Takahashi S, et al. Prediction of progression of coronary artery disease and clinical outcomes using vascular profiling of endothelial shear stress and arterial plaque characteristics: the PREDICTION Study. Circulation. 2012;126:172–181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.096438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone PH, Coskun AU, Kinlay S, Clark ME, Sonka M, Wahle A, Ilegbusi OJ, Yeghiazarians Y, Popma JJ, Orav J, Kuntz RE, Feldman CL. Effect of endothelial shear stress on the progression of coronary artery disease, vascular remodeling, and in-stent restenosis in humans: in vivo 6-month follow-up study. Circulation. 2003;108:438–444. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080882.35274.AD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatzizisis YS, Coskun AU, Jonas M, Edelman ER, Feldman CL, Stone PH. Role of endothelial shear stress in the natural history of coronary atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling: molecular, cellular and vascular behavior. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2379–2393. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samady H, Eshtehardi P, McDaniel MC, Suo J, Dhawan SS, Maynard C, Timmins LH, Quyyimi AA, Giddens DP. Coronary artery wall shear stress is associated with progression and transformation of atherosclerotic plaque and arterial remodeling in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2011;124:779–788. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.021824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koskinas KC, Chatzizisis YS, Antoniadis AP, Giannoglou GD. Role of endothelial shear stress in stent restenosis and thrombosis. Pathophysiologic mechanisms and implications for clinical translation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1337–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koskinas KC, Feldman CL, Chatzizisis YS, Coskun AU, Jonas M, Maynard C, Baker AB, Papafaklis MI, Edelman ER, Stone PH. Natural history of experimental coronary atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling in relation to endothelial shear stress: a serial, in-vivo intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2010;121:2092–2101. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.901678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chatzizisis YS, Jonas M, Coskun AU, Beigel R, Stone BV, Maynard C, Gerrity RG, Rogers C, Edelman ER, Feldman CL, Stone PH. Prediction of the localization of high risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques on the basis of low endothelial shear stress: an intravascular ultrasound and histopathology natural history study. Circulation. 2008;117:993–1002. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.695254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gimbrone MA, Nagel T, Topper JN. Biomechanical activation: an emerging paradigm in endothelial adhesion biology. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:S61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Y-Q, Zhu SN, Foster FS, Cybulsky MI, Henkelman RM. Aortic regurgitation dramatically alters the distribution of atherosclerotic lesions and enhances atherogenesis in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1181–89. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.204198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parmar KM, Larmn HB, Dai G, et al. Integration of flow-dependent endothelial phenotypes by Kruppel-like factor 2. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:49–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI24787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Libby P. The molecular mechanisms of the thrombotic complications of atherosclerosis. J Intern Med. 2008;263:517–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01965.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukumoto Y, Deguchi JO, Libby P, Rabkin-Aikawa E, Yasuhiko Sakata Y, Chin MT, Hill CC, Lawler PR, Varo N, Schoen FJ, MD, Krane SM, Aikawa M. Genetically determined resistance to collagenase action augments interstitial collagen accumulation in atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation. 2004;110:1953–1959. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143174.41810.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deguchi JO, Aikawa E, Libby P, Vachon JR, Inada M, Krane SM, Whittaker P, Aikawa M. Matrix metalloproteinase-13/collagenase-3 deletion promotes collagen accumulation and organization in mouse atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation. 2005;112:2708–2715. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.562041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider F, Sukhova GK, Aikawa M, Canner J, Gerdes N, Tang S-MT, Shi G-P, Apte SS, Libby P. Matrix metalloproteinase-14 deficiency in bone marrow-derived cells promotes collagen accumulation in mouse atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation. 2008;117:931–939. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.707448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gambillara V, Montorzi G, Haziza-Pigeon C, Stergiopulos N, Silacci P. Arterial wall response to ex-vivo exposure to oscillatory shear stress. J Vasc Res. 2005;42:535–544. doi: 10.1159/000088343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng C, Tempel D, van Haperen R, van der Baan A, Grosveld F, Daemen MJ, Krams R, de Crom R. Atherosclerotic lesion size and vulnerability are determined by patterns of fluid shear stress. Circulation. 2006;113:2744–2753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubo T, Maehara A, Mintz GS, et al. The dynamic nature of coronary artery lesion morphology assessed by serial virtual histology intravascular ultrasound tissue characterization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1590–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chatzizisis YS, Baker AB, Sukhova GK, Koskinas KC, Papafaklis MI, Jonas M, Coskun AU, Stone BV, Maynard C, Shi GP, Libby P, Feldman CL, Edelman ER, Stone PH. Augmented expression and activity of extracellular matrix-degrading enzymes in regions of low endothelial shear stress colocalize with coronary atheromata with thin fibrous caps in pigs. Circulation. 2011;123:621–630. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doran A, Meller N, McNamara CA. Role of smooth muscle cells in the initiation and early progression of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:812–819. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hao H, Gabbiani G, Camenzind E, Bacchetta M, Virmani R, Bochaton-Piallat ML. Phenotypic modulation of intima and media smooth muscle cells in fatal cases of coronary artery lesion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:326–332. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000199393.74656.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hastings N, Simmers MB, McDonald OG, Wamhoff BR, Blackman BR. Atherosclerosis-prone hemodynamics differentially regulates endothelial and smooth muscle cell phenotypes and promotes pro-inflammatory priming. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1824–C1833. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00385.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qi YX, Qu MJ, Long DK, Bo Liu, Yao QP, Chien S, Jiang ZL. Rho-GDP dissociation inhibitor alpha downregulated by low shear stress promotes vascular smooth muscle cell migration and apoptosis: a proteomic analysis. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;80:114–122. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerrity RG, Natarajan R, Nadler JL, Kimsey T. Diabetes-induced accelerated atherosclerosis in swine. Diabetes. 2001;50:1654–1665. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.7.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng GC, Loree HM, Kamm RD, Fishbein MC, Lee RT. Distribution of circumferential stress in ruptured and stable atherosclerotic lesions. A structural analysis with histopathological correlation. Circulation. 1993;87:1179–1187. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.4.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Birgelen C, Klinkhart W, Mintz GS, Papatheodorou A, Herrmann J, Baumgart D, Haude M, Wieneke H, Ge J, Erbel R. Plaque distribution and vascular remodeling of ruptured and nonruptured coronary plaques in the same vessel: an intravascular ultrasound study in vivo. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1864–1870. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01234-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christen T, Verin V, Bochaton-Piallat M, Popowsky Y, Ramaekers F, Debruyne P, Camenzid E, van Eys G, Gabbiani G. Mechanisms of neointima formation and remodeling in the porcine coronary artery. Circulation. 2001;103:882–888. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.6.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:767–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verhamme P, Quarck R, Hao H, Knaapen M, Dymarkowski S, Bernar H, Cleemput J, Janssens S, Vermylenf J, Gabbiani G, Kockxc M, Holvoet P. Dietary cholesterol withdrawal reduces vascular inflammation and induces coronary plaque stabilization in miniature pigs. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;56:135–144. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00515-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gijsen FJ, Mastik F, Schaar JA, Schuurbiers JC, van der Giessen WJ, de Feyter PJ, et al. High shear stress induces a strain increase in human coronary plaques over a 6-month period. EuroIntervention. 2011;7:121–127. doi: 10.4244/EIJV7I1A20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papafaklis MI, Takahashi S, Antoniadis A, Coskun AU, Tsuda M, Orita Y, et al. Endothelial shear stress magnitude and circumferential heterogeneity predict the localization of eccentric coronary atherosclerotic plaques in humans (abstr) Circulation. 2012;126:A17559. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koskinas KC, Chatzizisis YS, Papafaklis MI, et al. Incremental effect of hypercholesterolemia on coronary plaque progression and high-risk composition despite similarly low local endothelial shear stress (abstr) Eur Heart J. 2012;33(Suppl):273. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aikawa M, Sivam PN, Kuro-o M, Kimura K, Nakahara K, Takewaki S, Ueda M, Yamaguchi H, Yazaki Y, Nagai R. Human smooth muscle myosin heavy chain isoforms as molecular markers for vascular development and atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 1993;73:1000–1012. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.6.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aikawa M, Rabkin E, Voglic SJ, Shing H, Nagai R, Schoen FJ, Libby P. Lipid-lowering promotes accumulation of mature smooth muscle cells expressing smooth muscle myosin heavy chain isoforms in rabbit atheroma. Circ Res. 1998;83:1015–1026. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.10.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geng Y, Libby P. Evidence for apoptosis in advanced human atheroma: colocalization with interleukin-1b converting enzyme. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:251–266. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarke MCH, Figg N, Maguire JJ, Davenport AP, Goddard M, Littlewood TD, Bennett MR. Apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells induces features of plaque vulnerability in atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2006;12:1075–1080. doi: 10.1038/nm1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas JA, Deaton RA, Hastings NE, Shang Y, Moehle CW, Eriksson U, Topouzis S, Wamhoff BR, Blackman BR, Owens GK. PDGF-DD, a novel mediator of smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation, is upregulated in endothelial cells exposed to atherosclerosis-prone flow patterns. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H442–H452. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00165.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amento EP, Ehsani N, Palmer H, Libby P. Cytokines and growth factors positively and negatively regulate interstitial collagen gene expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1991;11:1223–1230. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.5.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herman MP, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Gerdes N, Tang N, Horton DB, Kilbride M, Breitbart RE, Chun M, Schönbeck U. Expression of neutrophil collagenase (matrix metalloproteinase-8) in human atheroma: a novel collagenolytic pathway suggested by transcriptional profiling. Circulation. 2001;104:1899–1904. doi: 10.1161/hc4101.097419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aikawa M, Rabkin E, Okada Y, Voglic S, Clinton SK, Brinckerhoff CE, Sukhova GK, Libby P. Lipid-lowering by diet reduces matrix metalloproteinase activity and increases collagen content of rabbit atheroma: a potential mechanism of lesion stabilization. Circulation. 1998;97:2433–2444. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.24.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.